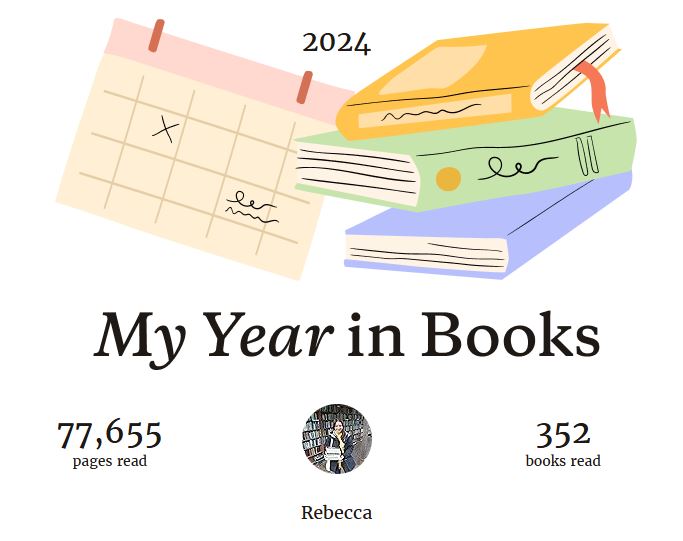

Author Archive: Rebecca Foster

Paul Auster Reading Week, II: Baumgartner & Travels in the Scriptorium (#AusterRW25 #ReadIndies)

It’s the final day of Annabel’s Paul Auster Reading Week and, after last week’s reviews of Invisible and Siri Hustvedt’s The Blindfold, I’m squeaking in with a short review of his final novel, Baumgartner, which Annabel chose as the buddy read and Cathy also wrote about. I paired it at random with another of his novellas and found that the two have a similar basic setup: an elderly man being let down by his body and struggling to memorialize what is important from his earlier life. They also happen to feature a character named Anna Blume, and other character names recur from his previous work. I wonder how fair it would be to say that most of Auster’s novels have the same autofiction-inspired protagonist, and are part of the same interlocking universe (à la David Mitchell and Elizabeth Strout)?

Baumgartner (2023)

Sy Baumgartner is a Princeton philosophy professor nearing retirement. The accidental death of his wife, Anna Blume, a decade ago, is still a raw loss he compares to a phantom limb. Only now can he bring himself to consider 1) proposing marriage to his younger colleague and longtime casual girlfriend, Judith Feuer, and 2) allowing a PhD student to sort through reams of Anna’s unpublished work, including poetry, translations and unfinished novels. The book includes a few of her autobiographical fragments, as well as excerpts from his writings, such as an account of a trip to Ukraine to explore his heritage (elsewhere we learn his mother’s name was Ruth Auster) and a précis of his book about car culture.

Baumgartner’s past is similar to Auster’s (and Adam Walker’s from Invisible – the two characters have a mutual friend in writer James Freeman), but not identical. His childhood memories and the passion and companionship he found with Anna are quite sweet. But I was somewhat thrown by the tone in sections that have this grumpy older man experiencing pseudo-comic incidents such as tumbling down the stairs while showing the meter reader the way. To my relief, the book doesn’t take the tragic turn the last pages seem to augur, instead leaving readers with a nicely open ending.

Baumgartner’s past is similar to Auster’s (and Adam Walker’s from Invisible – the two characters have a mutual friend in writer James Freeman), but not identical. His childhood memories and the passion and companionship he found with Anna are quite sweet. But I was somewhat thrown by the tone in sections that have this grumpy older man experiencing pseudo-comic incidents such as tumbling down the stairs while showing the meter reader the way. To my relief, the book doesn’t take the tragic turn the last pages seem to augur, instead leaving readers with a nicely open ending.

It’s not this that makes Baumgartner feel incomplete so much as the fact that any of its threads might have been expanded into a full-length novel. Maybe Auster had various projects on the go at the time of his final illness and combined them. That could explain the mishmash. I also had the odd sense that there were unconscious pastiches of other authors. Baumgartner reminds me a lot of James Darke, the curmudgeonly widower in Rick Gekoski’s pair of novels. When Baumgartner speaks to his dead wife on the telephone, I went hunting through my notes because I knew I’d encountered that specific plot before (the short story “The Telephone” by Mary Treadgold, collected in Fear, edited by Roald Dahl). The Ukraine passage might have come from Everything Is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer. So, for me, this was less distinctive as Auster works go. However, it’s gently readable and not formally challenging so it’s a pleasant valedictory volume if not the best representative of his oeuvre. (Public library) ![]()

Travels in the Scriptorium (2006)

This is very much in the vein of The Locked Room and Oracle Night and indeed makes reference to characters from those earlier books (Sophie Fanshawe and Peter Stillman from the former; John Trause from the latter). Mr. Blank lives in a sparse room containing manuscript pages and a stack of photographs. He is tended by a nurse named Anna Blume and given a rainbow of pharmaceuticals. Whether the pills help or keep him pacified is unclear. The haziness of his memory could be due to age or the drugs. He receives various visitors he feels he should recognize but can’t, and from the comments they make he fears he is being punished for dangerous missions he spearheaded. Even Anna, object of his pitiable sexual desires, is somehow his moral superior. Everyday self-care is struggle enough for him, but he does end up reading and adding to the partial stories on the table, including a dark Western set in an alternative 19th-century USA. Whatever he’s done in the past, he’s now an imprisoned writer and this is a day in his newly constrained life. The novella is a deliberate assemblage of typical Auster tropes and characters; there’s a puppet-master here, but no point. An indulgent minor work. But that’s okay as I still have plenty of appealing books from his back catalogue to read. [Interestingly, the American cover has a white horse in the centre of the room, an embodiment of Mr. Blank’s childhood memory of a white rocking-horse he called Whitey.] (Public library)

This is very much in the vein of The Locked Room and Oracle Night and indeed makes reference to characters from those earlier books (Sophie Fanshawe and Peter Stillman from the former; John Trause from the latter). Mr. Blank lives in a sparse room containing manuscript pages and a stack of photographs. He is tended by a nurse named Anna Blume and given a rainbow of pharmaceuticals. Whether the pills help or keep him pacified is unclear. The haziness of his memory could be due to age or the drugs. He receives various visitors he feels he should recognize but can’t, and from the comments they make he fears he is being punished for dangerous missions he spearheaded. Even Anna, object of his pitiable sexual desires, is somehow his moral superior. Everyday self-care is struggle enough for him, but he does end up reading and adding to the partial stories on the table, including a dark Western set in an alternative 19th-century USA. Whatever he’s done in the past, he’s now an imprisoned writer and this is a day in his newly constrained life. The novella is a deliberate assemblage of typical Auster tropes and characters; there’s a puppet-master here, but no point. An indulgent minor work. But that’s okay as I still have plenty of appealing books from his back catalogue to read. [Interestingly, the American cover has a white horse in the centre of the room, an embodiment of Mr. Blank’s childhood memory of a white rocking-horse he called Whitey.] (Public library)![]()

Faber, Auster’s longtime publisher, counts towards Reading Independent Publishers Month.

Paul Auster Reading Week: Invisible (#ReadIndies) & Siri Hustvedt’s The Blindfold (#AusterRW25)

The first time Annabel ran a Paul Auster Reading Week, in 2020, it was a great excuse for me to read six of his books (Winter Journal and The New York Trilogy were amazing; I also really enjoyed Oracle Night). I won’t manage so many this time, but maybe three, as well as one by his widow, Siri Hustvedt. Auster would have been 78 today but died of lung cancer in 2024. As a buddy read, Annabel is inviting people to read his final novel, Baumgartner. I’m partway through that and have another of his novellas waiting in the wings in case I find time.

For now, I’m focusing on a novel that exemplifies some recurring elements of his fiction: a book within a book, fragmented narratives, differing perspectives, cryptic events and the inscrutability of memory and language. I’m pairing it with Hustvedt’s debut novel, which is – not coincidentally, I should think – similarly intricate, weird and unsettling.

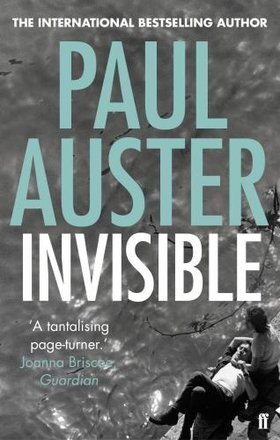

Invisible (2009)

To start with, I thought we were in autofiction territory, but Auster swiftly adopts a more typical metafictional approach. Adam Walker is a 20-year-old would-be poet studying at Columbia University in 1967. At a party he meets Rudolf Born, a visiting international affairs professor from Paris, and it seems a good omen: Born invests generously in Adam’s literary magazine and also seems open to sharing his beautiful girlfriend, Margot. But when the men are caught up in an attempted mugging, Adam turns against his idol.

That’s at the heart of Part I (“Spring”). Across four sections, the perspective changes and the narrative is revealed to be 1967, a manuscript Adam began while dying of cancer. “Summer,” in the second person, shines a light on his relationship with his sister, Gwyn. “Fall,” adapted from Adam’s third-person notes by his college friend and fellow author, Jim Freeman, tells of Adam’s study abroad term in Paris. Here he reconnected with Born and Margot with unexpected results. Jim intends to complete the anonymized story with the help of a minor character’s diary, but the challenge is that Adam’s memories don’t match Gwyn’s or Born’s.

That’s at the heart of Part I (“Spring”). Across four sections, the perspective changes and the narrative is revealed to be 1967, a manuscript Adam began while dying of cancer. “Summer,” in the second person, shines a light on his relationship with his sister, Gwyn. “Fall,” adapted from Adam’s third-person notes by his college friend and fellow author, Jim Freeman, tells of Adam’s study abroad term in Paris. Here he reconnected with Born and Margot with unexpected results. Jim intends to complete the anonymized story with the help of a minor character’s diary, but the challenge is that Adam’s memories don’t match Gwyn’s or Born’s.

I can’t say more about the themes without giving too much away, but this is a provocative novel that makes you question how truth is created or preserved. Who has the right to tell the story, and will justice be done? I wouldn’t say I enjoyed it, but I certainly admired how it was constructed. Auster conjures such a sense of unease, and I always felt like I had no idea what might happen next. With no speech marks, it all flows together in a compulsively readable way. (Secondhand purchase – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

Faber, Auster’s longtime publisher, counts towards Reading Independent Publishers Month.

The Blindfold by Siri Hustvedt (1992)

“Strange, I thought. Everything is strange.”

I read Hustvedt (The Blazing World) well before I ever tried Auster, and wouldn’t have realized then how similar their books are; they almost seem part of the same body of work. Was Hustvedt a fan or a student of his before they married? I don’t actually know and am loath to dispel the mystery for myself by looking into it. Anyway, there are striking connections between this and Invisible: the narrator is fairly autobiographical and a Columbia University student, the novel is in four loosely connected parts, and the sordid content culminates in a sudden, odd ending. (There’s also the little Easter egg here of “I heard someone shout the name Paul.”) But overall, this is more reminiscent of The New York Trilogy in its surreal randomness and subtly symbolic naming (e.g., the landlord is Mr. Then).

Iris Vegan (Hustvedt’s mother’s surname), like many an Auster character, is bewildered by what happens to her. An impoverished graduate student in literature, she takes on peculiar jobs. First Mr. Morning hires her to make audio recordings meticulously describing artefacts of a woman he’s obsessed with. Iris comes to believe this woman was murdered and rejects the work as invasive. Next she’s a photographer’s model but hates the resulting portrait and tries to take it off display. Then she’s hospitalized for terrible migraines and has upsetting encounters with a fellow patient, old Mrs. O. Finally, she translates a bizarre German novella and impersonates its protagonist, walking the streets in a shabby suit and even telling people her name is Klaus.

Iris Vegan (Hustvedt’s mother’s surname), like many an Auster character, is bewildered by what happens to her. An impoverished graduate student in literature, she takes on peculiar jobs. First Mr. Morning hires her to make audio recordings meticulously describing artefacts of a woman he’s obsessed with. Iris comes to believe this woman was murdered and rejects the work as invasive. Next she’s a photographer’s model but hates the resulting portrait and tries to take it off display. Then she’s hospitalized for terrible migraines and has upsetting encounters with a fellow patient, old Mrs. O. Finally, she translates a bizarre German novella and impersonates its protagonist, walking the streets in a shabby suit and even telling people her name is Klaus.

I worked out that the chronological order of the parts is 2 – 4 – 3 – 1, with 1 including a recap of the others. The sections feel like separate vignettes, perhaps reflecting Hustvedt’s previous experience with the short story form, and make a less than satisfying whole. I was most engaged with the segment on working for Mr. Morning and thought that might recur, but it doesn’t. Many of the secondary characters are grotesque, whereas Iris is the intellectual waif trying to make her way in the cruel city, almost like a Dickens or Gissing (anti)hero.

It’s refreshing to get a female take on the Bildungsroman and a little bit of gender-bending with the cross-dressing. (Iris reminds me of Lauren Elkin’s Flaneuse.) The title felt like an enigma to me until close to the end, when it’s revealed to be a tool of sexual sadism. Indeed, each of the sections, in its own way, addresses male exploitation of and violence against women. Disappointingly, Iris remains defined by her relationships with men. She deserves better. Heck, she deserves a sequel! It’s interesting to see where Hustvedt got her start, but I didn’t warm to this as I did to later novels including What I Loved. (Secondhand purchase – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

January Releases: Greathead, Kauffman, Mills & Watts (#ReadIndies)

I feel out of practice writing reviews after the endless period of sluggish and slightly lackluster reading that was January. Here we are at the start of Kaggsy and Lizzy Siddal’s Reading Independent Publishers Month challenge and I’m happy to make this my first tie-in post as these four books all happen to be from independent publishers. The first two are American novels (that could arguably be called linked short story collections) very much in my wheelhouse for their focus on dysfunctional families and disappointing characters. I also have a group biography aiming to illuminate bisexuality, and a poetry collection about girlhood/womanhood and nature.

The Book of George by Kate Greathead

The marketing for this novel courts relatability: you probably know a George – you might have dated one (women read the most litfic). Each chapter dates to a different period in George’s life, adolescence to late thirties. From the fact that 9/11 happened when he was a college freshman, I know he’s my exact contemporary, and I could indeed see bits of myself in this Everyman schmuck: indecisive, lazy, underachieving, privileged but never living up to his own or others’ expectations. Life keeps happening around him, but you wonder if he’ll ever make something happen for himself. Two gags are revealing: In college he is known for his impression of a clinically depressed penis going through airport security, and later he has 15 minutes of fame for appearing in a hidden-camera Super Bowl commercial. He’s been writing fiction for years – first a Stoner rip-off, then a Kerouac homage – but by the time he gets a short story collection together, it’s the height of #MeToo and he’s missed his moment to publish. Meanwhile, his cohort is doing great things, winning awards for documentaries (his pal Jeremiah) or becoming pro bono lawyers (his longsuffering girlfriend Jenny).

If you need to like a protagonist, expect frustration. Some of George’s behaviour is downright maddening, as when he obsessively plays his old Gameboy while his mother and Jenny pack up his childhood room. Tracing his relationships with his mother, his sister Cressida, and Jenny is rewarding. Sometimes they confront him over his shortcomings; other times they enable him. The novel is very funny, but it’s a biting, ironic humour, and there’s plenty of pathos as well. There are a few particular gut-punches, one relating to George’s father and others surrounding nice things he tries to do that backfire horribly. I thought of George as a rejoinder to all those ‘So-and-So Is Not Okay at All’ type of books featuring a face-planting woman on the cover. Greathead’s portrait is incisive but also loving. And yes, there is that hint of George, c’est moi recognition. His failings are all too common: the mildest of first-world tragedies but still enough to knock your confidence and make you question your purpose. For me this had something of the old-school charm of Jennifer Egan and Jonathan Safran Foer novels I read in the Naughties. I’ll seek out the author’s debut, Laura & Emma.

If you need to like a protagonist, expect frustration. Some of George’s behaviour is downright maddening, as when he obsessively plays his old Gameboy while his mother and Jenny pack up his childhood room. Tracing his relationships with his mother, his sister Cressida, and Jenny is rewarding. Sometimes they confront him over his shortcomings; other times they enable him. The novel is very funny, but it’s a biting, ironic humour, and there’s plenty of pathos as well. There are a few particular gut-punches, one relating to George’s father and others surrounding nice things he tries to do that backfire horribly. I thought of George as a rejoinder to all those ‘So-and-So Is Not Okay at All’ type of books featuring a face-planting woman on the cover. Greathead’s portrait is incisive but also loving. And yes, there is that hint of George, c’est moi recognition. His failings are all too common: the mildest of first-world tragedies but still enough to knock your confidence and make you question your purpose. For me this had something of the old-school charm of Jennifer Egan and Jonathan Safran Foer novels I read in the Naughties. I’ll seek out the author’s debut, Laura & Emma.

With thanks to Atlantic Books for the free copy for review. (Published in the USA by Henry Holt and Co. in 2024.)

I’ll Come to You by Rebecca Kauffman

Is 30 years long enough ago to count as historical fiction? In any case, this takes us through the whole of 1995, proceeding month by month and rotating through the close third-person perspectives of the members of one extended family as they navigate illnesses, break-ups and fraught parenting journeys. Corinne and Paul are trying to get pregnant; Paul’s mother, Ellen (again!), is still smarting from her husband leaving with no explanation; Corinne’s father, Bruce, has dementia but his wife, Janet, is doing her best to keep his cognitive deficiencies from the rest of the family. Son Rob is bitter about his ex-wife moving on so quickly, but both he and Ellen will have new romantic prospects before the end.

The family’s lies and secrets – also involving a Christmas run-in with Bruce’s shell-shocked brother decades ago – lead to everything coming to a head in a snowstorm. (As best I can tell, the 1995 setting was important mostly so there wouldn’t be cell phones during this crisis.) As with The Book of George, the episodic nature of the narrative means that particular moments are memorable but the whole maybe less so, and the interactions between characters stand out more than the people themselves. I’ll Come to You, named after a throwaway line in the text, is poorly served by both its cover and title, which give no sense of the contents. However, it’s a sweet, offbeat portrait of genuine, if generic, Americans; I was most reminded of J. Ryan Stradal’s work. Although I DNFed Kauffman’s The Gunners some years back, I’d be interested in trying her again with Chorus, which sounds like another linked story collection.

The family’s lies and secrets – also involving a Christmas run-in with Bruce’s shell-shocked brother decades ago – lead to everything coming to a head in a snowstorm. (As best I can tell, the 1995 setting was important mostly so there wouldn’t be cell phones during this crisis.) As with The Book of George, the episodic nature of the narrative means that particular moments are memorable but the whole maybe less so, and the interactions between characters stand out more than the people themselves. I’ll Come to You, named after a throwaway line in the text, is poorly served by both its cover and title, which give no sense of the contents. However, it’s a sweet, offbeat portrait of genuine, if generic, Americans; I was most reminded of J. Ryan Stradal’s work. Although I DNFed Kauffman’s The Gunners some years back, I’d be interested in trying her again with Chorus, which sounds like another linked story collection.

With thanks to Counterpoint (USA) for the advanced e-copy for review.

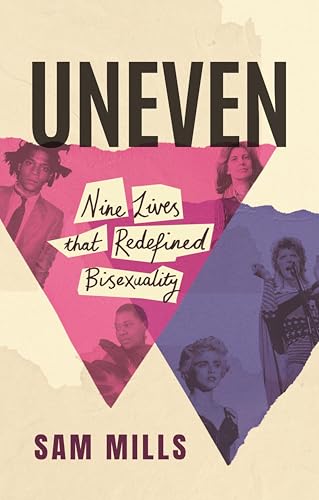

Uneven: Nine Lives that Redefined Bisexuality by Sam Mills

Back in 2022 I reviewed Julia Shaw’s Bi: The hidden culture, history and science of bisexuality, which took a social sciences approach. By contrast, this is a group biography of nine bisexuals – make that 10, as there are plenty of short memoir-ish passages from Mills, too. Oscar Wilde, Colette, Marlene Dietrich, Anaïs Nin, Susan Sontag: more or less familiar names, though not all of them are necessarily known for their sexuality. The chapters deliver standard potted biographies of the individuals’ work and relationships, probably containing little that couldn’t be found elsewhere in recent scholarship and not really living up to the revolutionary promise of the subtitle. However, it was worthwhile for Mills to recover Wilde as a bisexual rather than a closeted homosexual. A final trilogy of chapters comes more up to date with David Bowie, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Madonna. The closer to the present day, the more satisfying connections there are between figures. For instance, Madonna looked to both Dietrich and Bowie as role models and fashion icons, and she and Basquiat were lovers.

Mills and Shaw consider the same fundamental issues: bi erasure, with bisexuality the least understood and most easily overlooked element of LGBT and many passing as straight if in heterosexual marriages; and the stereotype of bis as hypersexual or promiscuous. Mills is keen to stress that bisexuals have very different trajectories and phases. Like Wilde, they might have a heterosexual era of happy marriage and parenthood followed by a homosexual spree. Or they might have simultaneous lovers of multiple genders. Some might never even act on strong same-sex desires. (Late last year I encountered a similar unity-in-diversity approach in Daniel Tamet’s Nine Minds, a group biography about autistic people.)

Mills and Shaw consider the same fundamental issues: bi erasure, with bisexuality the least understood and most easily overlooked element of LGBT and many passing as straight if in heterosexual marriages; and the stereotype of bis as hypersexual or promiscuous. Mills is keen to stress that bisexuals have very different trajectories and phases. Like Wilde, they might have a heterosexual era of happy marriage and parenthood followed by a homosexual spree. Or they might have simultaneous lovers of multiple genders. Some might never even act on strong same-sex desires. (Late last year I encountered a similar unity-in-diversity approach in Daniel Tamet’s Nine Minds, a group biography about autistic people.)

The 1890s to 1980s window allows for a record of changing mores yet means that the book seems rather dated. Were it written by an author of a later generation (Mills, who I knew for The Fragments of My Father, is around 50), the point of view and terminology would likely be quite different. Also, including a section on Bessie Smith within a chapter mostly on Colette felt tokenistic. (Though later considering Basquiat separately does add a BIPOC view.) Ultimately, though, my problem with Uneven was that I don’t want to know about behaviour – which is all that a biography can usually document – so much as the internal, soul stuff. Even from Mills, whose accounts of her long-term relationships and flings (including, yes, a threesome) can be titillating but not very enlightening, I didn’t get a sense of what it feels like. So neither the Shaw nor the Mills gave me precisely what I was looking for, which means that the perfect book on bisexuality either doesn’t exist or is out there but I haven’t found it yet. Any suggestions?

With thanks to Atlantic Books for the free copy for review.

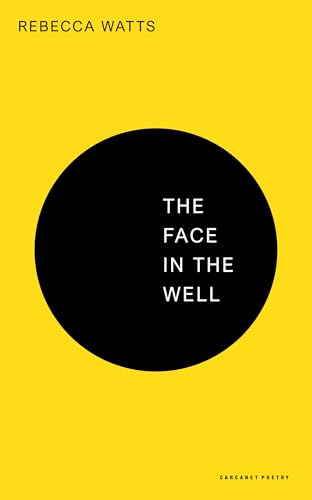

The Face in the Well by Rebecca Watts

I’ve also read Watts’ The Met Office Advises Caution and Red Gloves; this is her third collection. The Suffolk and Cambridgeshire scenery of her early and adult lives weaves all through, sometimes as an idyll that blurs the lines between humans and nature (“Private No Access”) but other times provoking anxiety about common or gendered dangers, as in the title poem or “The Old Mill” (“What happened there, / down by the old mill, / they never tell. // Something about / a man and a girl / is the most you’ll hear.”). “Woman Seeks” is a tongue-in-cheek advert for the perfect man. Animals – a dolphin, a shark, rodents, a wandering albatross, a robin – recur, as do women poets, especially Emily Brontë, and Victorian death culture (“Victoriana” and “Baroque”). Adulthood brings routine whereas childhood stands out for minor miracles, such as a free soda from a vending machine.

I’ve also read Watts’ The Met Office Advises Caution and Red Gloves; this is her third collection. The Suffolk and Cambridgeshire scenery of her early and adult lives weaves all through, sometimes as an idyll that blurs the lines between humans and nature (“Private No Access”) but other times provoking anxiety about common or gendered dangers, as in the title poem or “The Old Mill” (“What happened there, / down by the old mill, / they never tell. // Something about / a man and a girl / is the most you’ll hear.”). “Woman Seeks” is a tongue-in-cheek advert for the perfect man. Animals – a dolphin, a shark, rodents, a wandering albatross, a robin – recur, as do women poets, especially Emily Brontë, and Victorian death culture (“Victoriana” and “Baroque”). Adulthood brings routine whereas childhood stands out for minor miracles, such as a free soda from a vending machine.

The format and tone vary a lot, so the book is more of a grab bag than a cohesive statement. I noted slant rhymes and alliteration, always a favourite technique of mine. I especially liked “Entropy,” about finding a slice of cake in the freezer labeled by someone who is now dead (“Nothing ever // really dies: all the pieces of you / persist, riven and reconfigured / in infinite unknowable ways”) and “Personal Effects,” about the artefacts from her childhood that her mother guards under the bed (“twists of my hair, my teeth, / my bracelet from the hospital.”).

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the advanced e-copy for review.

Which of these appeal to you? What indie publishers have you been reading from recently?

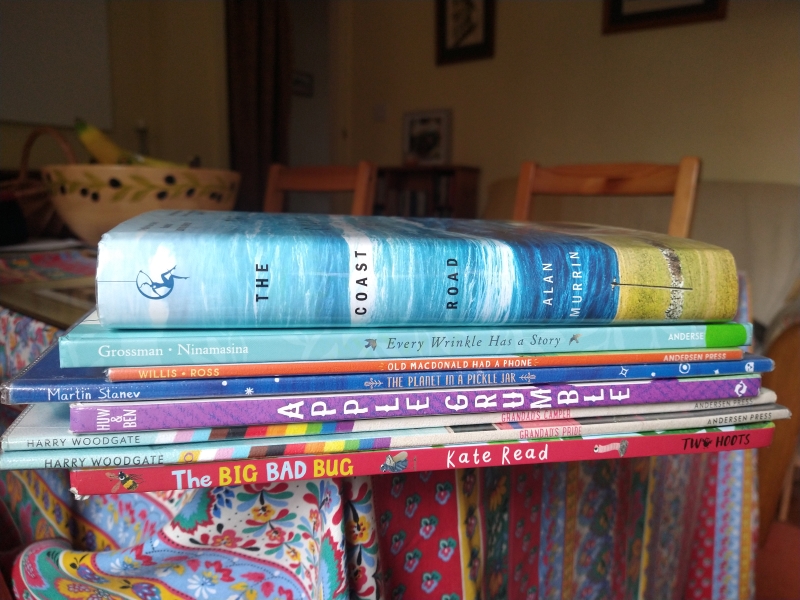

Love Your Library, January 2025

Thanks so much to Elle, Laura, and Skai for joining in this month!

READ

All children’s books this time!

- Every Wrinkle Has a Story by David Grossman – A sweet story about how experiences make us who we are, so ageing is a good thing.

Dexter Procter: The 10-Year-Old Doctor by Adam Kay – A fun if overlong book that will appeal to readers of Roald Dahl and David Walliams. It has bullying, a mystery and gross-out humour as well as some age-appropriate medical content.

Dexter Procter: The 10-Year-Old Doctor by Adam Kay – A fun if overlong book that will appeal to readers of Roald Dahl and David Walliams. It has bullying, a mystery and gross-out humour as well as some age-appropriate medical content.

- Apple Grumble by Huw Lewis-Jones – There’s a grumpy apple. And that’s it.

Constance in Peril by Ben Manley – So cute! Edward finds his favourite doll, Constance Hardpenny, in a bin. She’s dressed like a Victorian spinster and each day for a week she suffers a new near-calamity (her blank doll eyes somehow still conveying her alarm), only to be saved by Edward’s big sister.

Constance in Peril by Ben Manley – So cute! Edward finds his favourite doll, Constance Hardpenny, in a bin. She’s dressed like a Victorian spinster and each day for a week she suffers a new near-calamity (her blank doll eyes somehow still conveying her alarm), only to be saved by Edward’s big sister.

- The Big Bad Bug by Kate Read – Nice to see invertebrates featured. The message is about selfishness.

- Books Aren’t for Eating by Carlie Sorosiak – Starring a goat bookseller who learned to read books, not eat them, and passes on his enthusiasm to others. Other than the sudden ending, this was great.

- The Planet in a Pickle Jar by Martin Stanev – Intricate drawings and a touch of folklore (the author is Bulgarian) in this story of a grandmother who preserves the natural world and wants her grandchildren to continue her good work.

- Old Macdonald Had a Phone by Jeanne Willis – Updates the song for the tech age with a lesson that smartphones are useful tools but we mustn’t get addicted.

- Grandad’s Camper & Grandad’s Pride by Harry Woodgate – A little girl learns about her grandfather’s activist past with his partner and initiates a Pride parade in their little town.

/

/

CURRENTLY READING

- Myself & Other Animals by Gerald Durrell

- The Black Bird Oracle by Deborah Harkness

- The God of the Woods by Liz Moore

- Poetry Unbound: 50 Poems to Open Your World by Pádraig Ó Tuama

(+ the set-aside ones I mentioned last time)

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

(Everything from last time +)

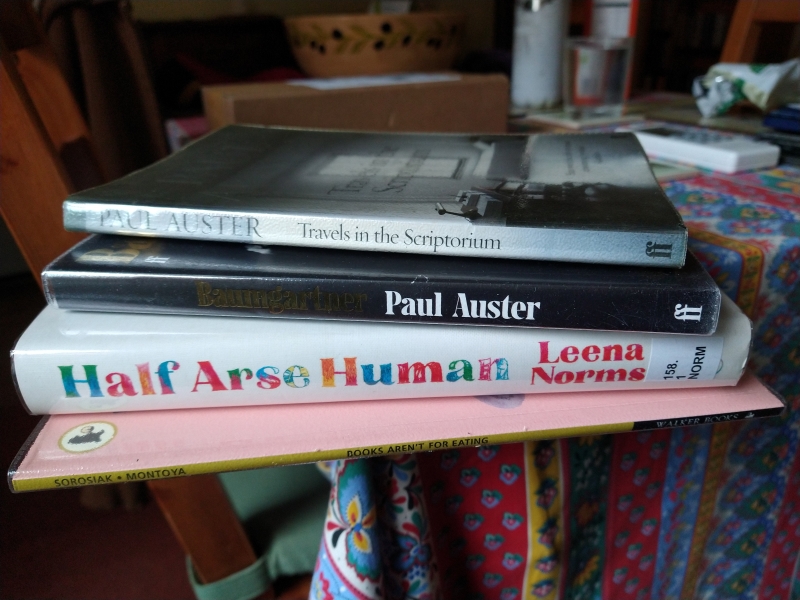

- Travels in the Scriptorium & Baumgartner by Paul Auster

- The Coast Road by Alan Murrin

- Half Arse Human by Leena Norms

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

(Everything from last time +)

- Confessions by Catherine Airey

- Deep Cuts by Holly Brickley

- Bellies by Nicola Dinan

- I Am Not a Tourist by Daisy J. Hung

- Bookish: How Reading Shapes Our Lives by Lucy Mangan

- When the Stammer Came to Stay by Maggie O’Farrell

ON HOLD, TO BE PICKED UP

- Maurice and Maralyn: An Extraordinary True Story of Shipwreck, Survival and Love by Sophie Elmhirst

- Black Woods, Blue Sky by Eowyn Ivey

- The Forgotten Sense: The Nose and the Perception of Smell by Jonas Olofsson

- Long Island by Colm Tóibín (for March book club)

RETURNED UNREAD

- The Mischief Makers by Elisabeth Gifford – I’ve enjoyed one of her books before, and a different biographical novel about Daphne du Maurier, but this seemed very bland at first glance.

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

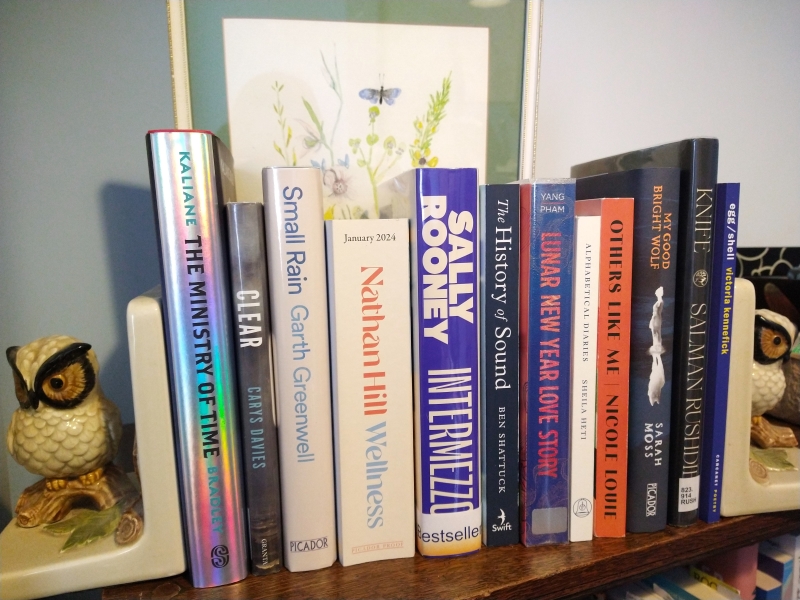

Reading Snapshot for Mid-January

As I said in my last post, I’m in the middle of a bunch of books but hardly finishing anything, so consider this another placeholder until my Love Your Library and January releases posts next week. People often ask how I read so much. One of the answers is that I generally read 20–30 books at once, bouncing between them as the mood takes me and making steady progress in most. A frequent follow-up question is how I keep so many books straight in my head. I maintain a variety of genres and topics in the stack and alternate between fiction, nonfiction and poetry in any reading session. If I’m going to be reviewing something, particularly for pay, I tend to make notes. Here’s a peek at my current stacks, with a line or two on each book and why I’m reading it.

- Myself & Other Animals by Gerald Durrell [public library] – This is a posthumous collection of excerpts from his published work, including newspaper articles, plus mini essays that he wrote towards an autobiography. We own/have read most of his animal-collecting and zoo-keeping memoirs and this is just as delightful, even in unconnected pieces. His conservationist zeal was ahead of his time.

- The God of the Woods by Liz Moore [public library] – It’s rare for me to borrow something from the Crime section, but this came highly lauded by Laila. Set in upstate New York in 1975, it’s a page-turning missing-girl mystery with a literary focus on character backstory, and it’s reminding me of Bright Young Women by Jessica Knoll and When the Stars Go Dark by Paula McLain.

- Gold by Elaine Feinstein [secondhand purchase] – I’ve enjoyed Feinstein’s poetry before so snapped this up on our second trip to Bridport. The first long poem was a monologue from the perspective of a collaborator of Mozart; I think I’ll engage more with the discrete poems to follow.

- Understorey by Anna Chapman Parker [review copy] – Catching up on one I was sent last year. It’s a one-year diary through ‘weeds’ (wild plants!) she observes and sketches near her home of Berwick upon Tweed, where we vacationed in September. I am enjoying reading a few peaceful entries per sitting.

- A God at the Door by Tishani Doshi [secondhand purchase] – Her Girls Are Coming out of the Woods was a favourite of mine a few years ago when I reviewed it for Wasafiri literary magazine. I found this on my last trip to Hay-on-Wye, and it is just as rich in long, forthright, feminist and political poems.

- The Secret Life of Snow by Giles Whittell [secondhand purchase] – I picked up a few snowy titles when we got a dusting the other week, in case it was the only snow of the year. This is so much like The Snow Tourist by Charlie English it’s uncanny; to my memory it’s more meteorological, though still accessible. The science is interspersed with travels and fun trivia about Norway’s Olympic skiers and so on.

- Moon of the Crusted Snow by Waubgeshig Rice [gift] – Probably my first book by an Indigenous Canadian, which was reason enough to read it. I’m about 50 pages in and so far it’s a plodding story of mysterious power outages which could just be part of the onset of winter but I suspect will turn out to be sinister and dystopian instead.

- Knead to Know by Neil Buttery [review copy] – Another 2024 book to catch up on. It’s a history of baking via mini-essays on loads of different breads, cakes, pies and pastries, many of them traditional English ones that you will never have heard of but will now want to cram. Lots of intriguing titbits.

- Invisible by Paul Auster [secondhand purchase] – Getting ready for Annabel’s second Paul Auster Reading Week in early February. A young (and Auster-like) would-be poet gets entangled with a thirtysomething professor who wants to fund a start-up literary magazine – and his French girlfriend. Highly readable and sure to get weirder.

- While the Earth Holds Its Breath by Helen Moat [review copy] – Yet another 2024 book to catch up on. Authors are still jumping on the Wintering bandwagon. This is composed of short autobiographical pieces about winter walks near home or further afield, many of them samey; the trip to Lapland has been a highlight so far.

- The Blindfold by Siri Hustvedt [review copy] – Also part of my preparation for Paul Auster Reading Week, and boy can you see his influence on her first novel! Iris Vegan is employed by Mr. Morning to record audio descriptions of relics left behind by a possibly murdered woman. Odd and enticing.

- Uneven by Sam Mills [review copy] – A group biography of nine bisexuals – make that 10, as there’s plenty of memoir fragments from Mills, too. I’ve read the chapters on Oscar Wilde, Colette & Bessie Smith, and Marlene Dietrich so far. It is particularly enlightening to think of Wilde as bi rather than a closeted homosexual.

- Unexpected Lessons in Love by Bernardine Bishop [secondhand purchase] – Every year I pick up at least a few “love” or “heart” titles in advance of Valentine’s Day. Bishop was one of my top discoveries last year (via The Street) and this Costa Award-nominated posthumous novel is equally engaging, even after just 50 pages.

- My Judy Garland Life by Susie Boyt [secondhand purchase] – After Loved and Missed, I was keen to try more from Boyt and this Ackerley Prize-shortlisted memoir sounded fascinating. I love The Wizard of Oz as much as the next person. Boyt, however, is a Garland mega-fan and blends biography and memoir as she writes about addiction, mental health, celebrity and the search for love.

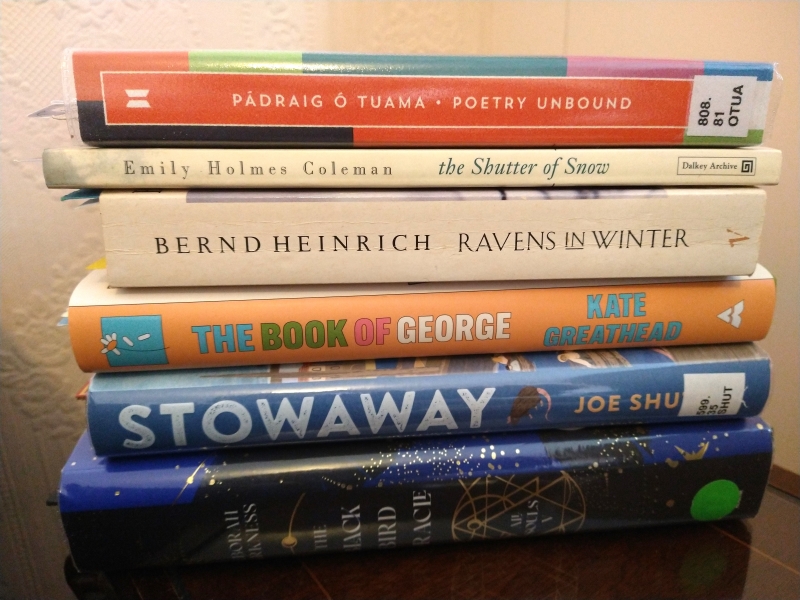

- Poetry Unbound by Pádraig Ó Tuama [public library] – I’m gradually making my way through this set of 50 poems and his critical/personal responses to them. Most of the poets have been unfamiliar to me. Marie Howe has been my top discovery.

- The Shutter of Snow by Emily Holmes Coleman [secondhand purchase] – Another incidental ‘snow’ title; this is autofiction about postpartum psychosis, written in a stream-of-consciousness style with no speech marks or apostrophes. It’s hard to believe it was written in the 1930s because it feels like it could have been yesterday.

- Ravens in Winter by Bernd Heinrich [secondhand purchase] – I’ve long meant to read more by Heinrich, who’s better known in the USA, after Winter World. This was a lucky find at Regent Books in Wantage. It’s a granular scientific study of bird behaviour, so I will likely read it very slowly, maybe even over two winters.

- The Book of George by Kate Greathead [review copy] – Linked short stories about an Everyman schmuck (and my exact contemporary) from adolescence up to today. He’s indecisive, lazy, an underachiever. Life keeps happening around him; will he make something happen? (George, c’est moi?) The deadpan tone is great.

- Stowaway by Joe Shute [public library] – I’ve been reading this off and on since, er, June, which is not to say that it’s not interesting but that it’s never been a priority. Like his book on ravens, it’s intended to rehabilitate the reputation of a species often considered to be a pest. He gets pet rats, too!

- The Black Bird Oracle by Deborah Harkness [public library] – It’s even rarer for me to borrow from the Science Fiction & Fantasy section of the library, but I’ve been following the series since A Discovery of Witches came out in 2011. I’m halfway through and enjoying Diana’s embrace of her witch heritage in the Salem area.

That’s not all, folks! There’s also the e-books.

- Dirty Kitchen by Jill Damatac [Edelweiss] – I’ll be reviewing this May release early for Shelf Awareness. The author’s Filipino family were undocumented immigrants in the USA and as a child she was occasionally abandoned and frequently physically abused. Recipes and legends offer a break from the tough subject matter (reminiscent of Educated or What My Bones Know).

- My Marriage Sabbatical by Leah Fisher [from publicist] – She Writes Press is a reliable source of women’s life writing. I’ve only just started this but will try to review it this month. Fisher, a psychotherapist, was sick of her psychiatrist husband’s workaholism and wanted to try living differently, starting with a house share.

- I’ll Come to You by Rebecca Kauffman [from publicist] – Another American linked short story collection, moving month by month through 1995 (does that count as historical fiction?!), cycling through the members of an extended family as they navigate illnesses and fraught parenting journeys. I’m getting J. Ryan Stradal vibes.

- Constructing a Witch by Helen Ivory [Edelweiss] – This feminist take on the historical persecution and stereotypes of witches is a good match for the Harkness! I just keep forgetting to open it up on my Kindle.

According to Goodreads, I’m reading 28 books at the moment, so I haven’t even covered all of them. (The rest include library books that would more honestly be classified as “set aside.”)

Whew. It somehow seems like even more when I write them all up like this…

Back to the reading!

My Life in Book Titles from 2024

As usual for January, I’m in the middle of lots of books but hardly finishing anything, so consider this a placeholder until my Love Your Library and January releases posts later in the month. It’s a fun meme that goes around every year; I first spotted it on Annabel’s blog and Susan also took part. I’ve never had a go before but when I looked at the prompts I realized some books I read in 2024 have titles that work awfully well. Links are to my reviews.

In high school I was [one of the] Remarkably Bright Creatures (Shelby Van Pelt)

In high school I was [one of the] Remarkably Bright Creatures (Shelby Van Pelt)

- People might be surprised by All the Beauty in the World (Patrick Bringley)

- I will never be A Spy in the House of Love (Anaïs Nin)

My fantasy job is To Be a Cat (Matt Haig)

My fantasy job is To Be a Cat (Matt Haig)

- At the end of a long day, I need [a] Cocktail (Lisa Alward)

- I hate being [an] Exhibit (R.O. Kwon)

- Wish I had Various Miracles (Carol Shields)

- My family reunions are The Grief Cure (Cory Delistraty)

At a party you’d find me with Orphans of the Carnival (Carol Birch)

At a party you’d find me with Orphans of the Carnival (Carol Birch)

- I’ve never been to Jungle House (Julianne Pachico)

A happy day includes The Old Haunts (Allan Radcliffe)

A happy day includes The Old Haunts (Allan Radcliffe)

- Motto I live by: I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself (Glynnis MacNicol)

On my bucket list is A Bookshop of One’s Own (Jane Cholmeley)

On my bucket list is A Bookshop of One’s Own (Jane Cholmeley)

- In my next life, I want to have A House Full of Daughters (Juliet Nicolson)

Most Anticipated Books of the First Half of 2025

As I said the other week, I sometimes wonder if designating a book as “Most Anticipated” is a curse – if the chosen books are doomed to fail to meet my expectations. Nonetheless, I can’t resist compiling such a list at least once each year.

Also on my radar: fiction by Claire Adam, Amy Bloom, Emma Donoghue, Sarah Hall, Michelle Huneven, Eowyn Ivey, Rachel Joyce, Heather Parry and Torrey Peters; nonfiction by Melissa Febos, Robert Macfarlane, Lucy Mangan, Suzanne O’Sullivan and Sophie Pavelle. (Further ahead, I’ll seek out I Want to Burn This Place Down: Essays by Maris Kreizman and The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley in July, The Savage Landscape by Cal Flyn in Oct. and Tigers between Empires by Jonathan C. Slaght in Nov.)

However, below I’ve narrowed it down to the 25 books I’m most looking forward to for the first half of 2025, 15 fiction and 10 nonfiction. I’m impressed that 4 are in translation! And 22/25 are by women (all the fiction is). In release date order, with UK publication info given first if available. The blurbs are adapted from Goodreads. I’ve taken the liberty of using whichever cover is my favourite (almost always the U.S. one).

Fiction

Live Fast by Brigitte Giraud (trans. from the French by Cory Stockwell) [Feb. 11, Ecco]: I found out about this autofiction novella via an early Shelf Awareness review. It “follows one woman’s quest to comprehend the motorcycle accident that took the life of her partner Claude at age 41. The narrator … recounts the chain of events that led up to the fateful accident, tracing the tiny, maddening twists of fate that might have prevented its tragic outcome. Each chapter asks the rhetorical question, ‘what if’ … A sensitive elegy to her husband”.

Live Fast by Brigitte Giraud (trans. from the French by Cory Stockwell) [Feb. 11, Ecco]: I found out about this autofiction novella via an early Shelf Awareness review. It “follows one woman’s quest to comprehend the motorcycle accident that took the life of her partner Claude at age 41. The narrator … recounts the chain of events that led up to the fateful accident, tracing the tiny, maddening twists of fate that might have prevented its tragic outcome. Each chapter asks the rhetorical question, ‘what if’ … A sensitive elegy to her husband”.

The Unworthy by Agustina Bazterrica (trans. from the Spanish by Sarah Moses) [13 Feb., Pushkin; March 4, Scribner]: I wasn’t enamoured of the Argentinian author’s short stories, but Tender Is the Flesh was awesome. This is a short dystopian horror set in a convent. “In the House of the Sacred Sisterhood, the unworthy live in fear of the Superior Sister’s whip. … Risking her life, one of the unworthy keeps a diary in secret. Slowly, memories surface from a time before the world collapsed, before the Sacred Sisterhood became the only refuge. Then Lucía arrives.” (PDF copy for Shelf Awareness review)

The Unworthy by Agustina Bazterrica (trans. from the Spanish by Sarah Moses) [13 Feb., Pushkin; March 4, Scribner]: I wasn’t enamoured of the Argentinian author’s short stories, but Tender Is the Flesh was awesome. This is a short dystopian horror set in a convent. “In the House of the Sacred Sisterhood, the unworthy live in fear of the Superior Sister’s whip. … Risking her life, one of the unworthy keeps a diary in secret. Slowly, memories surface from a time before the world collapsed, before the Sacred Sisterhood became the only refuge. Then Lucía arrives.” (PDF copy for Shelf Awareness review)

Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito [13 Feb., Fourth Estate; Feb. 4, Liveright]: Feito’s debut, Mrs March, was deliciously odd, and I love the (U.S.) cover for this one. It sounds like a bonkers horror take on Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw, “a gruesome and gleeful new novel that probes the psyche of a bloodthirsty governess. Winifred Notty arrives at Ensor House prepared to play the perfect Victorian governess—she’ll dutifully tutor her charges, Drusilla and Andrew, tell them bedtime stories, and only joke about eating children.”

Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito [13 Feb., Fourth Estate; Feb. 4, Liveright]: Feito’s debut, Mrs March, was deliciously odd, and I love the (U.S.) cover for this one. It sounds like a bonkers horror take on Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw, “a gruesome and gleeful new novel that probes the psyche of a bloodthirsty governess. Winifred Notty arrives at Ensor House prepared to play the perfect Victorian governess—she’ll dutifully tutor her charges, Drusilla and Andrew, tell them bedtime stories, and only joke about eating children.”

Three Days in June by Anne Tyler [13 Feb., Chatto & Windus (Penguin) / Feb. 11, Knopf]: I’m not a Tyler completist, but she’s reliable and this is a novella! “It’s the day before her daughter’s wedding and things are not going well for Gail Baines. First …, she loses her job … Then her ex-husband Max turns up at her door expecting to stay for the festivities. He doesn’t even have a suit. Instead, he’s brought memories, a shared sense of humour – and a cat looking for a new home. … [And] daughter Debbie discovers her groom has been keeping a secret.” Susan vouches for this. (Edelweiss download / on order from library)

The Swell by Kat Gordon [27 Feb., Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: I got vague The Mercies (Kiran Millwood Hargrave) vibes from the blurb. “Iceland, 1910. In the middle of a severe storm two sisters, Freyja and Gudrun, rescue a mysterious, charismatic man from a shipwreck near their remote farm. Sixty-five years later, a young woman, Sigga, is spending time with her grandmother when they learn a body has been discovered on a mountainside near Reykjavik, perfectly preserved in ice.” (NetGalley download)

The Swell by Kat Gordon [27 Feb., Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: I got vague The Mercies (Kiran Millwood Hargrave) vibes from the blurb. “Iceland, 1910. In the middle of a severe storm two sisters, Freyja and Gudrun, rescue a mysterious, charismatic man from a shipwreck near their remote farm. Sixty-five years later, a young woman, Sigga, is spending time with her grandmother when they learn a body has been discovered on a mountainside near Reykjavik, perfectly preserved in ice.” (NetGalley download)

Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie [4 March, Fourth Estate/Knopf]: This is THE book I’m most looking forward to; I’ve read everything Adichie has published and Americanah was a 5-star read for me. So I did something I’ve never done before and pre-ordered the signed independent bookshop edition from my local indie, Hungerford Bookshop. “Chiamaka is a Nigerian travel writer living in America. Alone in the midst of the pandemic, she recalls her past lovers and grapples with her choices and regrets.” The focus is on four Nigerian American women “and their loves, longings, and desires.” (New purchase)

Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie [4 March, Fourth Estate/Knopf]: This is THE book I’m most looking forward to; I’ve read everything Adichie has published and Americanah was a 5-star read for me. So I did something I’ve never done before and pre-ordered the signed independent bookshop edition from my local indie, Hungerford Bookshop. “Chiamaka is a Nigerian travel writer living in America. Alone in the midst of the pandemic, she recalls her past lovers and grapples with her choices and regrets.” The focus is on four Nigerian American women “and their loves, longings, and desires.” (New purchase)

Kate & Frida by Kim Fay [March 11, G.P. Putnam’s Sons]: “Frida Rodriguez arrives in Paris in 1991 … But then she writes to a bookshop in Seattle … A friendship begins that will redefine the person she wants to become. Seattle bookseller Kate Fair is transformed by Frida’s free spirit … [A] love letter to bookshops and booksellers, to the passion we bring to life in our twenties”. Sounds like a cross between The Paris Novel and 84 Charing Cross Road – could be fab; could be twee. We shall see! (Edelweiss download)

Kate & Frida by Kim Fay [March 11, G.P. Putnam’s Sons]: “Frida Rodriguez arrives in Paris in 1991 … But then she writes to a bookshop in Seattle … A friendship begins that will redefine the person she wants to become. Seattle bookseller Kate Fair is transformed by Frida’s free spirit … [A] love letter to bookshops and booksellers, to the passion we bring to life in our twenties”. Sounds like a cross between The Paris Novel and 84 Charing Cross Road – could be fab; could be twee. We shall see! (Edelweiss download)

The Antidote by Karen Russell [13 March, Chatto & Windus (Penguin) / March 11, Knopf]: I love Russell’s Swamplandia! but haven’t gotten on with her other work I’ve tried, so I’m only tentatively enthusiastic about the odd Wizard of Oz-inspired blurb: “a historic dust storm ravages the fictional town of Uz, Nebraska. But Uz is already collapsing—not just under the weight of the Great Depression … but beneath its own violent histories. The Antidote follows a ‘Prairie Witch,’ … a Polish wheat farmer …; his orphan niece, a … witch’s apprentice …; a voluble scarecrow; and a New Deal photographer”. (Requested from publisher)

The Antidote by Karen Russell [13 March, Chatto & Windus (Penguin) / March 11, Knopf]: I love Russell’s Swamplandia! but haven’t gotten on with her other work I’ve tried, so I’m only tentatively enthusiastic about the odd Wizard of Oz-inspired blurb: “a historic dust storm ravages the fictional town of Uz, Nebraska. But Uz is already collapsing—not just under the weight of the Great Depression … but beneath its own violent histories. The Antidote follows a ‘Prairie Witch,’ … a Polish wheat farmer …; his orphan niece, a … witch’s apprentice …; a voluble scarecrow; and a New Deal photographer”. (Requested from publisher)

Elegy, Southwest by Madeleine Watts [13 March, ONE (Pushkin) / Feb. 18, Simon & Schuster]: Watts’s debut, The Inland Sea, was a hidden gem. Given the news from L.A., this seems all the more potent: “In November 2018, Eloise and Lewis rent a car in Las Vegas and take off on a two-week road trip across the American southwest … [w]hile wildfires rage. … Lewis, an artist working for a prominent land art foundation, is grieving the recent death of his mother, while Eloise is an academic researching the past and future of the Colorado River … [and] beginning to suspect she might be pregnant”. (Edelweiss download)

Elegy, Southwest by Madeleine Watts [13 March, ONE (Pushkin) / Feb. 18, Simon & Schuster]: Watts’s debut, The Inland Sea, was a hidden gem. Given the news from L.A., this seems all the more potent: “In November 2018, Eloise and Lewis rent a car in Las Vegas and take off on a two-week road trip across the American southwest … [w]hile wildfires rage. … Lewis, an artist working for a prominent land art foundation, is grieving the recent death of his mother, while Eloise is an academic researching the past and future of the Colorado River … [and] beginning to suspect she might be pregnant”. (Edelweiss download)

O Sinners! by Nicole Cuffy [March 18, One World (Random House)]: Cuffy’s Dances, which was longlisted for the Carol Shields Prize, was very good. The length of this sophomore novel (464 pages) gives me pause, but I do generally gravitate towards stories of cults. “Faruq Zaidi, a young journalist reeling from the recent death of his father, a devout Muslim, takes the opportunity to embed in a cult called The Nameless [b]ased in the California redwoods and shepherded by an enigmatic [Black] Vietnam War veteran.”

O Sinners! by Nicole Cuffy [March 18, One World (Random House)]: Cuffy’s Dances, which was longlisted for the Carol Shields Prize, was very good. The length of this sophomore novel (464 pages) gives me pause, but I do generally gravitate towards stories of cults. “Faruq Zaidi, a young journalist reeling from the recent death of his father, a devout Muslim, takes the opportunity to embed in a cult called The Nameless [b]ased in the California redwoods and shepherded by an enigmatic [Black] Vietnam War veteran.”

The Accidentals: Stories by Guadalupe Nettel (trans. from the Spanish by Rosalind Harvey) [10 April, Fitzcarraldo Editions / April 29, Bloomsbury]: I really enjoyed Nettel’s International Booker-shortlisted novel Still Born. “When an albatross strays too far from its home, or loses its bearings, it becomes an ‘accidental’, an unmoored wanderer. The protagonists of these eight stories each find the ordinary courses of their lives disrupted by an unexpected event. … Deft and disquieting, oscillating between the real and the fantastical”. (PDF copy for Shelf Awareness review)

The Accidentals: Stories by Guadalupe Nettel (trans. from the Spanish by Rosalind Harvey) [10 April, Fitzcarraldo Editions / April 29, Bloomsbury]: I really enjoyed Nettel’s International Booker-shortlisted novel Still Born. “When an albatross strays too far from its home, or loses its bearings, it becomes an ‘accidental’, an unmoored wanderer. The protagonists of these eight stories each find the ordinary courses of their lives disrupted by an unexpected event. … Deft and disquieting, oscillating between the real and the fantastical”. (PDF copy for Shelf Awareness review)

Ordinary Saints by Niamh Ni Mhaoileoin [24 April, Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: “Brought up in a devout household in Ireland, Jay is now living in London with her girlfriend, determined to live day to day and not think too much about either the future or the past. But when she learns that her beloved older brother, who died in a terrible accident, may be made into a Catholic saint, she realises she must at last confront her family, her childhood and herself.” Winner of the inaugural PFD Queer Fiction Prize and shortlisted for the Women’s Prize Discoveries Award.

Ordinary Saints by Niamh Ni Mhaoileoin [24 April, Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: “Brought up in a devout household in Ireland, Jay is now living in London with her girlfriend, determined to live day to day and not think too much about either the future or the past. But when she learns that her beloved older brother, who died in a terrible accident, may be made into a Catholic saint, she realises she must at last confront her family, her childhood and herself.” Winner of the inaugural PFD Queer Fiction Prize and shortlisted for the Women’s Prize Discoveries Award.

Heartwood by Amity Gaige [1 May, Fleet / April 1, Simon & Schuster]: I loved Gaige’s Sea Wife. “In the heart of the Maine woods, an experienced Appalachian Trail hiker goes missing. She is forty-two-year-old Valerie Gillis, who has vanished 200 miles from her final destination. … At the centre of the search is Beverly, the determined Maine State Game Warden tasked with finding Valerie, who is managing the search on the ground. While Beverly is searching, Lena, a seventy-six-year-old birdwatcher in a retirement community, becomes an unexpected armchair detective.”

Heartwood by Amity Gaige [1 May, Fleet / April 1, Simon & Schuster]: I loved Gaige’s Sea Wife. “In the heart of the Maine woods, an experienced Appalachian Trail hiker goes missing. She is forty-two-year-old Valerie Gillis, who has vanished 200 miles from her final destination. … At the centre of the search is Beverly, the determined Maine State Game Warden tasked with finding Valerie, who is managing the search on the ground. While Beverly is searching, Lena, a seventy-six-year-old birdwatcher in a retirement community, becomes an unexpected armchair detective.”

Are You Happy?: Stories by Lori Ostlund [May 6, Astra House]: Ostlund is not so well known, especially outside the USA, but I enjoyed her debut novel, After the Parade, back in 2015. “Nine masterful stories that explore class, desire, identity, and the specter of violence in America–and in American families–against women and the LGBTQ+ community. … [W]e watch Ostlund’s characters as they try—and often fail—to make peace with their pasts while navigating their present relationships and responsibilities.” (Edelweiss download)

Are You Happy?: Stories by Lori Ostlund [May 6, Astra House]: Ostlund is not so well known, especially outside the USA, but I enjoyed her debut novel, After the Parade, back in 2015. “Nine masterful stories that explore class, desire, identity, and the specter of violence in America–and in American families–against women and the LGBTQ+ community. … [W]e watch Ostlund’s characters as they try—and often fail—to make peace with their pasts while navigating their present relationships and responsibilities.” (Edelweiss download)

Ripeness by Sarah Moss [22 May, Picador / Sept. 9, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Though I was disappointed by her last two novels, I’ll read anything Moss publishes and hope for a return to form. “It is the [19]60s and … Edith finds herself travelling to rural Italy … to see her sister, ballet dancer Lydia, through the final weeks of her pregnancy, help at the birth and then make a phone call which will seal this baby’s fate, and his mother’s.” Promises to be “about migration and new beginnings, and about what it is to have somewhere to belong.”

Ripeness by Sarah Moss [22 May, Picador / Sept. 9, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Though I was disappointed by her last two novels, I’ll read anything Moss publishes and hope for a return to form. “It is the [19]60s and … Edith finds herself travelling to rural Italy … to see her sister, ballet dancer Lydia, through the final weeks of her pregnancy, help at the birth and then make a phone call which will seal this baby’s fate, and his mother’s.” Promises to be “about migration and new beginnings, and about what it is to have somewhere to belong.”

Nonfiction

The Forgotten Sense: The New Science of Smell by Jonas Olofsson [Out now! 7 Jan., William Collins / Mariner]: Part of a planned deep dive into the senses. “Smell is … one of our most sensitive and refined senses; few other mammals surpass our ability to perceive scents in the animal kingdom. Yet, as the millions of people who lost their sense of smell during the COVID-19 pandemic can attest, we too often overlook its role in our overall health. … For readers of Bill Bryson and Steven Pinker”. (On order from library)

The Forgotten Sense: The New Science of Smell by Jonas Olofsson [Out now! 7 Jan., William Collins / Mariner]: Part of a planned deep dive into the senses. “Smell is … one of our most sensitive and refined senses; few other mammals surpass our ability to perceive scents in the animal kingdom. Yet, as the millions of people who lost their sense of smell during the COVID-19 pandemic can attest, we too often overlook its role in our overall health. … For readers of Bill Bryson and Steven Pinker”. (On order from library)

Bread and Milk by Karolina Ramqvist (trans. from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel) [13 Feb., Bonnier Books / Feb. 11, Coach House Books]: I think I first found about this via the early Foreword review. “Bread and Milk traces a life through food, from carefully restricted low-fat margarine to a bag of tangerines devoured in one sitting to the luxury of a grandmother’s rice pudding. In this radiant memoir from one of Northern Europe’s most notable literary stylists, we follow several generations of women and their daughters as they struggle with financial and emotional vulnerability, independence, and motherhood.”

Bread and Milk by Karolina Ramqvist (trans. from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel) [13 Feb., Bonnier Books / Feb. 11, Coach House Books]: I think I first found about this via the early Foreword review. “Bread and Milk traces a life through food, from carefully restricted low-fat margarine to a bag of tangerines devoured in one sitting to the luxury of a grandmother’s rice pudding. In this radiant memoir from one of Northern Europe’s most notable literary stylists, we follow several generations of women and their daughters as they struggle with financial and emotional vulnerability, independence, and motherhood.”

My Mother in Havana: A Memoir of Magic & Miracle by Rebe Huntman [Feb. 18, Monkfish]: I found out about this from Rebecca Moon Ruark and by the time the publisher offered it to me I’d already downloaded it. The themes of bereavement and religion are right up my street. “As she explores the memory of her own mother, interlacing it with her search for the sacred feminine, Huntman leads us into a world of séance and sacrifice, pilgrimage and sacred dance, which resurrect her mother and bring Huntman face to face with a larger version of herself.” (Edelweiss download)

My Mother in Havana: A Memoir of Magic & Miracle by Rebe Huntman [Feb. 18, Monkfish]: I found out about this from Rebecca Moon Ruark and by the time the publisher offered it to me I’d already downloaded it. The themes of bereavement and religion are right up my street. “As she explores the memory of her own mother, interlacing it with her search for the sacred feminine, Huntman leads us into a world of séance and sacrifice, pilgrimage and sacred dance, which resurrect her mother and bring Huntman face to face with a larger version of herself.” (Edelweiss download)

Mother Animal by Helen Jukes [27 Feb., Elliott & Thompson]: This may be the 2025 release I’ve known about for the longest. I remember expressing interest the first time the author tweeted about it; it’s bound to be a good follow-up to Lucy Jones’s Matrescence. “When Helen Jukes falls pregnant, … she widens her frame of reference, looking beyond humans to ask what motherhood looks like in other species. … As she enters the sleeplessness, chaos and intimate discoveries of life with a newborn, these animal stories become … companions and guides.” (Requested from publisher)

Mother Animal by Helen Jukes [27 Feb., Elliott & Thompson]: This may be the 2025 release I’ve known about for the longest. I remember expressing interest the first time the author tweeted about it; it’s bound to be a good follow-up to Lucy Jones’s Matrescence. “When Helen Jukes falls pregnant, … she widens her frame of reference, looking beyond humans to ask what motherhood looks like in other species. … As she enters the sleeplessness, chaos and intimate discoveries of life with a newborn, these animal stories become … companions and guides.” (Requested from publisher)

Alive: An Alternative Anatomy by Gabriel Weston [6 March, Vintage (Penguin) / March 4, David R. Godine]: I’ve read Weston’s Direct Red and appreciate her perspective. “As she became a surgeon, a mother, and ultimately a patient herself, Weston found herself grappling with the gap between scientific knowledge and unfathomable complexity of human experience. … Focusing on our individual organs, not just under the intense spotlight of the operating theatre, but in the central role they play in the stories of our lives.”

Alive: An Alternative Anatomy by Gabriel Weston [6 March, Vintage (Penguin) / March 4, David R. Godine]: I’ve read Weston’s Direct Red and appreciate her perspective. “As she became a surgeon, a mother, and ultimately a patient herself, Weston found herself grappling with the gap between scientific knowledge and unfathomable complexity of human experience. … Focusing on our individual organs, not just under the intense spotlight of the operating theatre, but in the central role they play in the stories of our lives.”

The Lost Trees of Willow Avenue: A Story of Climate and Hope on One American Street by Mike Tidwell [March 25, St. Martin’s Press]: A must-read for me because it’s set in Takoma Park, Maryland, where I was born. “A love letter to the magnificent oaks and other trees dying from record heat waves and bizarre rain, [activist] Tidwell’s story depicts the neighborhood’s battle to save the trees and combat climate change. … Tidwell chronicles people on his block sick with Lyme disease, a church struggling with floods, and young people anguishing over whether to have kids, … against the global backdrop of 2023’s record heat domes and raging wildfires and hurricanes.”

The Lost Trees of Willow Avenue: A Story of Climate and Hope on One American Street by Mike Tidwell [March 25, St. Martin’s Press]: A must-read for me because it’s set in Takoma Park, Maryland, where I was born. “A love letter to the magnificent oaks and other trees dying from record heat waves and bizarre rain, [activist] Tidwell’s story depicts the neighborhood’s battle to save the trees and combat climate change. … Tidwell chronicles people on his block sick with Lyme disease, a church struggling with floods, and young people anguishing over whether to have kids, … against the global backdrop of 2023’s record heat domes and raging wildfires and hurricanes.”

Breasts: A Relatively Brief Relationship by Jean Hannah Edelstein [3 April, Phoenix (W&N)]: I loved Edelstein’s 2018 memoir This Really Isn’t About You, and I regularly read her Substack. “As [Edelstein] comes of age, she learns that breasts are a source of both shame and power. In early motherhood, she sees her breasts transform into a source of sustenance and a locus of pain. And then, all too soon, she is faced with a diagnosis and forced to confront what it means to lose and rebuild an essential part of yourself.”

Breasts: A Relatively Brief Relationship by Jean Hannah Edelstein [3 April, Phoenix (W&N)]: I loved Edelstein’s 2018 memoir This Really Isn’t About You, and I regularly read her Substack. “As [Edelstein] comes of age, she learns that breasts are a source of both shame and power. In early motherhood, she sees her breasts transform into a source of sustenance and a locus of pain. And then, all too soon, she is faced with a diagnosis and forced to confront what it means to lose and rebuild an essential part of yourself.”

Poets Square: A Memoir in Thirty Cats by Courtney Gustafson [8 May, Fig Tree (Penguin) / April 29, Crown]: Gustafson became an Instagram and TikTok hit with her posts about looking after a feral cat colony in Tucson, Arizona. The money she raised via social media allowed her to buy her home and continue caring for animals. “[Gustafson] had no idea about the grief and hardship of animal rescue, the staggering size of the problem in neighborhoods across the country. And she couldn’t have imagined how that struggle … would help pierce a personal darkness she’d wrestled for with much of her life.” (Proof copy from publisher)

Poets Square: A Memoir in Thirty Cats by Courtney Gustafson [8 May, Fig Tree (Penguin) / April 29, Crown]: Gustafson became an Instagram and TikTok hit with her posts about looking after a feral cat colony in Tucson, Arizona. The money she raised via social media allowed her to buy her home and continue caring for animals. “[Gustafson] had no idea about the grief and hardship of animal rescue, the staggering size of the problem in neighborhoods across the country. And she couldn’t have imagined how that struggle … would help pierce a personal darkness she’d wrestled for with much of her life.” (Proof copy from publisher)

Lifelines: Searching for Home in the Mountains of Greece by Julian Hoffman [15 May, Elliott & Thompson]: Hoffman’s Irreplaceable was my book of 2019. “In the summer of 2000, Julian Hoffman and his wife Julia found themselves disillusioned with city life. Overwhelmed by long commutes, they stumbled upon a book about Prespa, Greece – a remote corner of Europe filled with stone villages, snow-capped mountains and wildlife. What began as curiosity soon transformed into a life-changing decision: to make Prespa their home.” I know next to nothing about Greece and this is a part of it that doesn’t fit the clichés.

Lifelines: Searching for Home in the Mountains of Greece by Julian Hoffman [15 May, Elliott & Thompson]: Hoffman’s Irreplaceable was my book of 2019. “In the summer of 2000, Julian Hoffman and his wife Julia found themselves disillusioned with city life. Overwhelmed by long commutes, they stumbled upon a book about Prespa, Greece – a remote corner of Europe filled with stone villages, snow-capped mountains and wildlife. What began as curiosity soon transformed into a life-changing decision: to make Prespa their home.” I know next to nothing about Greece and this is a part of it that doesn’t fit the clichés.

Spent: A Comic Novel by Alison Bechdel [22 May, Jonathan Cape (Penguin) / May 20, Mariner Books]: Bechdel’s Fun Home is an absolute classic of the graphic memoir. I’ve lost track of her career a bit but like the sound of this one. “A cartoonist named Alison Bechdel, running a pygmy goat sanctuary in Vermont, is existentially irked by a climate-challenged world and a citizenry on the brink of civil war.” After her partner’s wood-chopping video goes viral, she decides to create her own ethical-living reality TV show. Features cameos from some characters from her Dykes to Watch Out For series.

Spent: A Comic Novel by Alison Bechdel [22 May, Jonathan Cape (Penguin) / May 20, Mariner Books]: Bechdel’s Fun Home is an absolute classic of the graphic memoir. I’ve lost track of her career a bit but like the sound of this one. “A cartoonist named Alison Bechdel, running a pygmy goat sanctuary in Vermont, is existentially irked by a climate-challenged world and a citizenry on the brink of civil war.” After her partner’s wood-chopping video goes viral, she decides to create her own ethical-living reality TV show. Features cameos from some characters from her Dykes to Watch Out For series.

Other lists of anticipated books:

Clare – we overlap on a couple of our picks

Kate – one pick in common, plus I’ve already read a couple of her others

Laura – we overlap on a couple of our picks

Paul (mostly science and nature)

What catches your eye here? What other 2025 titles do I need to know about?

2025 Releases Read So Far, Including a Review of Aerth by Deborah Tomkins

I’ve gotten to 22 books with a 2025 publication date so far, most of them for paid reviews for Foreword Reviews or Shelf Awareness. I give review excerpts, links where available, and ratings below to pique your interest. (I’ll follow up on Friday with a list of my 25 Most Anticipated titles for the first half of the year!) First, though, it’s time to introduce you to the joint winner of the inaugural Weatherglass Novella Prize, as chosen by Ali Smith – I reviewed the other winner, Astraea by Kate Kruimink, as part of Novellas in November.

Aerth by Deborah Tomkins

At Weatherglass Books’ “The Future of the Novella” event in September (my write-up is here), I was intrigued to learn about this sci-fi novella in flash set on alternative Earths. The draft title was “First, Do No Harm,” referring to one of the five mantras for life on Aerth, a peaceful matriarchal planet that has been devastated by a pandemic. Magnus, the Everyman protagonist, is his parents’ only surviving offspring after their first nine children died of the virus. We meet Magnus in what seems an idyllic childhood of seasonal celebrations and his mother’s homemade cakes. But the weight of his parents’ expectations is too much, and after his relationship with Tilly disintegrates, he decides to fulfil a long-held ambition of becoming an astronaut and travelling to Urth. Here he starts off famous – a sought-after talking head in the media with the ear of the prime minister – but public opinion eventually turns against him.

Urth could be modelled on contemporary London: polluted, capitalist and celebrity-obsessed. But it would be oversimplifying to call Aerth a pre-industrial foil; although at first its lifestyle seems more wholesome, later revelations force us to question why it developed in this way. The planets are twins with potentially parallel environmental and societal trajectories and some exact counterparts; the hints about this “mirrorverse” are eerie. It all could have added up to an unsubtle allegory in which Aerth represents what we should aspire to and Urth symbolizes what we must resist, but Tomkins makes it more nuanced than that. Magnus’s homesickness when he fears he’s trapped on Urth is a heart-rending element, and the diverse styles and formats (such as lists, documents, and second-person sections) keep things interesting. The themes of parenting and loneliness are particularly potent.

Tomkins first wrote this for the Bath Prize in 2018 and was longlisted. She initially sent the book out to science fiction publishers but was told that it wasn’t ‘sci-fi enough’. I can see how it could fall into the gap between literary fiction and genre fiction: though it’s set on other planets and involves space travel, its speculative nature is understated; it feels more realist. A memorable interrogation of longing and belonging, this novella ponders the value of individuals and their choices in the midst of inexorable planetary trajectories.

Tomkins first wrote this for the Bath Prize in 2018 and was longlisted. She initially sent the book out to science fiction publishers but was told that it wasn’t ‘sci-fi enough’. I can see how it could fall into the gap between literary fiction and genre fiction: though it’s set on other planets and involves space travel, its speculative nature is understated; it feels more realist. A memorable interrogation of longing and belonging, this novella ponders the value of individuals and their choices in the midst of inexorable planetary trajectories.

(Wowee, Aerth made it onto Eric of Lonesome Reader’s Top Ten list for 2024!)

With thanks to Weatherglass Books for the free copy for review. Aerth will be released on 25 January.

My top recommendations so far for 2025:

(in alphabetical order) All: ![]()

Save Me, Stranger by Erika Krouse (Flatiron Books, January 21): These 12 first-person narratives are voiced by people in crisis, for whom encounters with strangers tender the possibility of transformation. In the title story, the narrator is taken hostage in a convenience store hold-up. Krouse frequently focuses on young women presented with dilemmas. In “The Pole of Cold,” Vera meets Theo, the son of the American weather researchers who died in the same Siberian plane crash that killed her reindeer herder father. Travel is a recurring element, with stories set in Thailand and Japan as well as various U.S. states. The book exhibits tremendous range, imagining a myriad places, minds, and situations. Krouse often eschews tidy endings, leaving characters on the brink and allowing readers to draw inferences about what they will decide. Fans of Danielle Evans and Lauren Groff have a treat in store.

Save Me, Stranger by Erika Krouse (Flatiron Books, January 21): These 12 first-person narratives are voiced by people in crisis, for whom encounters with strangers tender the possibility of transformation. In the title story, the narrator is taken hostage in a convenience store hold-up. Krouse frequently focuses on young women presented with dilemmas. In “The Pole of Cold,” Vera meets Theo, the son of the American weather researchers who died in the same Siberian plane crash that killed her reindeer herder father. Travel is a recurring element, with stories set in Thailand and Japan as well as various U.S. states. The book exhibits tremendous range, imagining a myriad places, minds, and situations. Krouse often eschews tidy endings, leaving characters on the brink and allowing readers to draw inferences about what they will decide. Fans of Danielle Evans and Lauren Groff have a treat in store.

Immemorial by Lauren Markham (Transit Books, February 4): This outstanding book-length essay compares language, memorials, and rituals as strategies for coping with climate anxiety and grief. The dichotomies of the physical versus the abstract and the permanent versus the ephemeral are explored; the past, present, and future dance through the text. With language not changing at the pace of the climate, Markham turns to the “Bureau of Linguistical Reality” for help coining a new term for anticipatory ecological grief. The title is one candidate, “premation” another. Forthright, wistful, and determined, the book treats grief as a positive, as “fuel” or a “portal.” Hope is not theoretical in this setup, but solidified in action. In Markham’s case, becoming a parent embodied her trust in the future. Immemorial is an elegant meditation on memory and impermanence in an age of climate crisis.

Immemorial by Lauren Markham (Transit Books, February 4): This outstanding book-length essay compares language, memorials, and rituals as strategies for coping with climate anxiety and grief. The dichotomies of the physical versus the abstract and the permanent versus the ephemeral are explored; the past, present, and future dance through the text. With language not changing at the pace of the climate, Markham turns to the “Bureau of Linguistical Reality” for help coining a new term for anticipatory ecological grief. The title is one candidate, “premation” another. Forthright, wistful, and determined, the book treats grief as a positive, as “fuel” or a “portal.” Hope is not theoretical in this setup, but solidified in action. In Markham’s case, becoming a parent embodied her trust in the future. Immemorial is an elegant meditation on memory and impermanence in an age of climate crisis.