Blurb Your Enthusiasm by Louise Willder

At last, I’m caught up reviewing September releases! It’s one of the busier months in the publishing calendar, so I shouldn’t be surprised that I had such a bounteous crop. Now I can pay more attention to R.I.P. selections, catching up on others’ blog posts, and getting ahead before the start of Novellas in November.

Blurb Your Enthusiasm is a delightful bibliophile’s miscellany with a great title – not just for the play on words, but also for how it encapsulates what this is about: ways of pithily spreading excitement about books. The first part of the subtitle, “An A–Z of Literary Persuasion,” is puzzling in that the structure is scattershot rather than strictly alphabetical, but the second is perfect: from the title and cover to the contents, Louise Willder is interested in what convinces people to acquire and read a book.

Over the last 25 years, she has written the jacket copy for thousands of Penguin releases, so she has it down to a science as well as an art. Book reviewing seems to me to be an adjacent skill. I know from nine years of freelance writing about books, in which I’ve had to produce reviews ranging from 100 to 2,000 words, that the shortest and most formulaic reviews can be the most difficult to compose, but are also excellent writing discipline. As Willder puts it, “Writing short, for whatever reason you do it, forces rigour, and it reminds you that words are a precious and powerful resource. Form both limits and liberates.”

How to do justice to the complexity of several hundred pages of an author’s hard work in just 150 words or so? How to suggest the tone and contents without a) resorting to clichés (“luminous” and “unflinching” are a couple of my bugbears), b) giving too much away, c) overstating the case, or misleading anyone about the merits of a Marmite book, or d) committing the cardinal sin of boring readers before they’ve even opened to the first page?

it can be easy to forget that a potential reader hasn’t read it: they don’t know anything about it. You can’t sell them the experience of the book – you have to sell them the expectation of reading it; the idea of it. And that’s when a copywriter can be an author’s best friend.

[An aside: Literary critics and blog reviewers generally see themselves as having different roles: making objective (pah!) pronouncements about literary value versus cheerleading for the books they love and want others to discover (a sort of unpaid partnership with publicists). I’m in the odd position of being both, and feel I engage in the two activities pretty much equally, perhaps leaning more towards the former. There’s some crossover, of course, with bloggers such as myself happy to publish the occasional more critical review. But we aren’t generally, as Willder is, in the business of selling books, so unless we’re pals with the author on Twitter we don’t tend to have a vested interest in seeing the book do well.]

Each reader will home in on certain topics here: the art of the first line, Dickens’s serialization and self-promotion, Orwell’s guidelines for good writing, the differences between British and American jacket copy, the use of punctuation, and so much more. I particularly loved the mock and bad blurbs she cites (we’ve both commented on the ludicrous one for The Country Girls!), including one an AI created for this book, and her rundown of the conventions of blurb-writing for various genres, everything from children’s books to science fiction. She frequently breaks her own rules (e.g., she’s anti-adjective and -ellipses, yet I found five of the one and two of the other in the Crace blurb; see below) and is very funny to boot.

Here’s some of the bookish and word-nerd trivia that captivated me:

- J. D. Salinger didn’t allow blurbs on his books.

- The American usage of the word “blurb” is for advance review quotes that fellow authors contribute for inclusion on the cover. I didn’t realize I used the word interchangeably for either meaning; in the UK, one might call such a quote a “puff.”

- Marshall McLuhan invented the “page 69 test” – to decide whether you want to buy/read a book, turn to that page instead of (or maybe in addition to) looking at the first paragraph.

- A New York publishing CEO once joked that Lincoln’s Doctor’s Dog would be an optimal title to appeal to readers (respected president + health + animal), but there are actually now six books bearing some variation on that title and all were presumably flops!

- “Wackaging” is the word for quirky marketing that has products talk to us (Innocent Smoothies, established in 1999, is thought to have started the trend).

- I pulled out my copy of Jim Crace’s Quarantine to see how Willder managed to write a blurb about a novel about Jesus without mentioning Jesus (“a Galilean who they say has the power to work miracles”)!

Some more favourite lines:

“There’s always something to love and learn from in a book, especially if it lasts as long as these books [children’s classics] have, and part of the job of people like me is to pick out what makes it special and pass it on.”

“always ask yourself, what’s really going on here? Why should anyone care? And how do we make them care?”

For all of us who value books, whether we write about them or not, those seem like important points to remember. We read to learn, but also to feel, and when we share our love of books with other people we can do so on the basis of how they have engaged our brains and hearts. This was thoroughly entertaining and has prompted me to pay that bit more attention to the few paragraphs on the inside of a book jacket. (See also Susan’s review.)

With thanks to Oneworld for the free copy for review.

20 Books of Summer, 17–20: Bennett, Davidson, Diffenbaugh, Kimmerer

As per usual, I’m squeezing in my final 20 Books of Summer reviews late on the very last day of the challenge. I’ll call it a throwback to the all-star procrastination of my high school and college years. This was a strong quartet to finish on: two novels, the one about (felling) trees and the other about communicating via flowers; and two nonfiction books about identifying trees and finding harmony with nature.

Tree-Spotting: A Simple Guide to Britain’s Trees by Ros Bennett; illus. Nell Bennett (2022)

Botanist Ros Bennett has designed this as a user-friendly guide that can be taken into the field to identify 52 of Britain’s most common trees. Most of these are native species, plus a few naturalized ones. “Walks in the countryside … take on a new dimension when you find yourself on familiar, first-name terms with the trees around you,” she encourages. She introduces tree families, basics of plant anatomy and chemistry, and the history of the country’s forests before moving into identification. Summer leaves make ID relatively easy with a three-step set of keys, explained in words as well as with impressively detailed black-and-white illustrations of representative species’ leaves (by her daughter, Nell Bennett).

Seasonality makes things trickier: “Identifying plants is not rocket science, though occasionally it does require lots of patience and a good hand lens. Identifying trees in winter is one of those occasions.” This involves a close look at details of the twigs and buds – a challenge I’ll be excited to take up on canalside walks later this year. The third section of the book gives individual profiles of each featured species, with additional drawings. I learned things I never realized I didn’t know (like how to pronounce family names, e.g., Rosaceae is “Rose-A-C”), and formalized other knowledge. For instance, I can recognize an ash tree by sight, but now I know you identify an ash by its 9–13 compound, opposite, serrated leaflets.

Some of the information was more academic than I needed (as with one of my earlier summer reads, The Ash Tree by Oliver Rackham), but it’s easy to skip any sections that don’t feel vital and come back to them another time. I most valued the approachable keys and their accompanying text, and will enjoy taking this compact naked hardback on autumn excursions. Bennett never dumbs anything down, and invites readers to delight in discovery. “So – go out, introduce yourself to your neighbouring trees and wonder at their beauty, ingenuity and variety.”

With thanks to publicist Claire Morrison and Welbeck for the free copy for review.

Damnation Spring by Ash Davidson (2021)

When this would-be Great American Novel* arrived unsolicited through my letterbox last summer, I was surprised I’d not encountered the pre-publication buzz. The cover blurb is from Nickolas Butler, which gives you a pretty good sense of what you’re getting into: a gritty, working-class story set in what threatens to be an overwhelmingly male milieu. For generations, Rich Gundersen’s family has been involved in logging California’s redwoods. Davidson is from Arcata, California, and clearly did a lot of research to recreate an insider perspective and a late 1970s setting. There is some specialist vocabulary and slang (the loggers call the largest trees “big pumpkins”), but it’s easy enough to understand in context.

What saves the novel from going too niche is the double billing of Rich and his wife, Colleen, who is an informal community midwife and has been trying to get pregnant again almost ever since their son Chub’s birth. She’s had multiple miscarriages, and their family and acquaintances have experienced alarming rates of infant loss and severe birth defects. Conservationists, including an old high school friend of Colleen’s, are attempting to stop the felling of redwoods and the spraying of toxic herbicides.

What saves the novel from going too niche is the double billing of Rich and his wife, Colleen, who is an informal community midwife and has been trying to get pregnant again almost ever since their son Chub’s birth. She’s had multiple miscarriages, and their family and acquaintances have experienced alarming rates of infant loss and severe birth defects. Conservationists, including an old high school friend of Colleen’s, are attempting to stop the felling of redwoods and the spraying of toxic herbicides.

A major element, then, is people gradually waking up to the damage chemicals are doing to their waterways and, thereby, their bodies. The problem, for me, was that I realized this much earlier than any of the characters, and it felt like Davidson laid it on too thick with the many examples of human and animal deaths and deformities. This made the book feel longer and less subtle than, e.g., The Overstory. I started it as a buddy read with Marcie (Buried in Print) 11 months ago and quickly bailed, trying several more times to get back into the book before finally resorting to skimming to the end. Still, especially for a debut author, Davidson’s writing chops are impressive; I’ll look out for what she does next.

*I just spotted that it’s been shortlisted for the $25,000 Mark Twain American Voice in Literature Award.

With thanks to Tinder Press for the proof copy for review.

The Language of Flowers by Vanessa Diffenbaugh (2011)

The cycle would continue. Promises and failures, mothers and daughters, indefinitely.

The various covers make this look more like chick lit than it is. Basically, it’s solidly readable issues- and character-driven literary fiction, on the lighter side but of the caliber of any Oprah’s Book Club selection. It reminded me most of White Oleander by Janet Fitch, one of my 20 Books selections in 2018, because of the focus on the foster care system and a rebellious girl’s development in California, and the floral metaphors.

The various covers make this look more like chick lit than it is. Basically, it’s solidly readable issues- and character-driven literary fiction, on the lighter side but of the caliber of any Oprah’s Book Club selection. It reminded me most of White Oleander by Janet Fitch, one of my 20 Books selections in 2018, because of the focus on the foster care system and a rebellious girl’s development in California, and the floral metaphors.

In Diffenbaugh’s debut, Victoria Jones ages out of foster care at 18 and leaves her group home for an uncertain future. She spends time homeless in San Francisco but her love of flowers, and particularly the Victorian meanings assigned to them, lands her work in a florist’s shop and reconnects her with figures from her past. Chapters alternate between her present day and the time she came closest to being adopted – by Elizabeth, who owned a vineyard and loved flowers, when she was nine. We see how estrangements and worries over adequate mothering recur, with Victoria almost a proto-‘Disaster Woman’ who keeps sabotaging herself. Throughout, flowers broker reconciliations.

I won’t say more about a plot that would be easy to spoil, but this was a delight and reminded me of a mini flower dictionary with a lilac cover and elaborate cursive script that I owned when I was a child. I loved the thought that flowers might have secret messages, as they do for the characters here. Whatever happened to that book?! (Charity shop)

Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer (2013)

I’d heard Kimmerer recommended by just about every nature writer around, North American or British, and knew I needed this on my shelf. Before I ever managed to read it, I saw her interviewed over Zoom by Lucy Jones in July 2021 about her other popular science book, Gathering Moss, which was first published 18 years ago but only made it to the UK last year. So I knew what a kind and peaceful person she is: she just emanates warmth and wisdom, even over a computer screen.

And I did love Braiding Sweetgrass nearly as much as I expected to, with the caveat that the tiny-print 400 pages of my paperback edition make the essays feel very dense. I could only read a handful of pages in a sitting. Also, after about halfway, it started to feel a bit much, like maybe she had given enough examples from her life, Native American legend and botany. The same points about gratitude for the gifts of the Earth, kinship with other creatures, responsibility and reciprocity are made over and over.

However, I feel like this is the spirituality the planet needs now, so I’ll excuse any repetition (and the basket-weaving essay I thought would never end). “In a world of scarcity, interconnection and mutual aid become critical for survival. So say the lichens.” (She’s funny, too, so you don’t have to worry about the contents getting worthy.) She effectively wields the myth of the Windigo as a metaphor for human greed, essential to a capitalist economy based on “emptiness” and “unmet desires.”

However, I feel like this is the spirituality the planet needs now, so I’ll excuse any repetition (and the basket-weaving essay I thought would never end). “In a world of scarcity, interconnection and mutual aid become critical for survival. So say the lichens.” (She’s funny, too, so you don’t have to worry about the contents getting worthy.) She effectively wields the myth of the Windigo as a metaphor for human greed, essential to a capitalist economy based on “emptiness” and “unmet desires.”

I most enjoyed the shorter essays that draw on her fieldwork or her experience of motherhood. “The Gift of Strawberries” – “An Offering” – “Asters and Goldenrod” make a stellar three-in-a-row, and “Collateral Damage” is an excellent later one about rescuing salamanders from the road, i.e. doing the small thing that we can do rather than being overwhelmed by the big picture of nature in crisis. “The Sound of Silverbells” is one of the most well-crafted individual pieces, about taking a group of students camping when she lived in the South. At first their religiosity (creationism and so on) grated, but when she heard them sing “Amazing Grace” she knew that they sensed the holiness of the Great Smoky Mountains.

But the pair I’d recommend most highly, the essays that made me weep, are “A Mother’s Work,” about her time restoring an algae-choked pond at her home in upstate New York, and its follow-up, “The Consolation of Water Lilies,” about finding herself with an empty nest. Her loving attention to the time-consuming task of bringing the pond back to life is in parallel to the challenges of single parenting, with a vision of the passing of time being something good rather than something to resist.

Here are just a few of the many profound lines:

For all of us, becoming indigenous to a place means living as if your children’s future mattered, to take care of the land as if our lives, both material and spiritual, depended on it.

I’m a plant scientist and I want to be clear, but I am also a poet and the world speaks to me in metaphor.

Ponds grow old, and though I will too, I like the ecological idea of aging as progressive enrichment, rather than progressive loss.

This will be a book to return to time and again. (Gift from my wish list several years ago)

I also had one DNF from this summer’s list:

Human Croquet by Kate Atkinson: This reminded me of a cross between The Crow Road by Iain Banks and The Heavens by Sandra Newman, what with the teenage narrator and a vague time travel plot with some Shakespearean references. I put it on the pile for this challenge because I’d read it had a forest setting. I haven’t had much luck with Atkinson in the past and this didn’t keep me reading past page 60. (Little Free Library)

A Look Back at My 20 Books of Summer 2022

Half of my reads are pictured here. The rest were e-books (represented by the Kindle) or have already had to go back to the library.

My fiction standout was The Language of Flowers, reviewed above. Nonfiction highlights included Forget Me Not and Braiding Sweetgrass, with Tree-Spotting the single most useful book overall. I also enjoyed reading a couple of my selections on location in the Outer Hebrides. The hands-down loser (my only 1-star rating of the year so far, I think?) was Bonsai. As always, there are many books I could have included and wished I’d found the time for, like (on my Kindle) A House among the Trees by Julia Glass, This Is Your Mind on Plants by Michael Pollan and Finding the Mother Tree by Suzanne Simard.

At the start, I was really excited about my flora theme and had lots of tempting options lined up, some of them literally about trees/flowers and others more tangentially related. As the summer went on, though, I wasn’t seeing enough progress so scrambled to substitute in other things I was reading from the library or for paid reviews. This isn’t a problem, per se, but my aim with this challenge has generally been to clear TBR reads from my own shelves. Maybe I didn’t come up with enough short and light options (just two novella-length works and a poetry collection; only the Diffenbaugh was what I’d call a page-turner); also, even with the variety I’d built in, having a few plant quest memoirs got a bit samey.

Next year…

I’m going to skip having a theme and set myself just one simple rule: any 20 print books from my shelves (NOT review copies). There will then be plenty of freedom to choose and substitute as I go along.

Irene Redfield and Clare Kendry grew up together in Chicago. Both are light-skinned African American women, their features described as “olive” or “golden.” Irene has remained within the Black community, marrying a doctor named Brian and living a comfortable life in Harlem. However, she is able to pass as white in certain circumstances, such as when she and Clare meet for tea in a high-end establishment. Clare, on the other hand, is hiding her ancestry from her white husband, Jack Bellew, who spews hatred for Black people. “It’s such a frightfully easy thing to do. If one’s the type, all that’s needed is a little nerve,” she insists.

Irene Redfield and Clare Kendry grew up together in Chicago. Both are light-skinned African American women, their features described as “olive” or “golden.” Irene has remained within the Black community, marrying a doctor named Brian and living a comfortable life in Harlem. However, she is able to pass as white in certain circumstances, such as when she and Clare meet for tea in a high-end establishment. Clare, on the other hand, is hiding her ancestry from her white husband, Jack Bellew, who spews hatred for Black people. “It’s such a frightfully easy thing to do. If one’s the type, all that’s needed is a little nerve,” she insists. I’d long wanted to read this and couldn’t find it through a library, so bought a copy as part of a Foyles order funded by last year’s Christmas money. I’m not clear on whether the Penguin Little Black Classics edition is abridged, but the 1929 preface by Franz Xaver Kappus, Rilke’s correspondent, only mentions 10 letters, which is how many are printed here, so I have at least gotten the gist. Most of the letters were sent in 1903–4, with a final one dated 1908, from various locations on Rilke’s European travels.

I’d long wanted to read this and couldn’t find it through a library, so bought a copy as part of a Foyles order funded by last year’s Christmas money. I’m not clear on whether the Penguin Little Black Classics edition is abridged, but the 1929 preface by Franz Xaver Kappus, Rilke’s correspondent, only mentions 10 letters, which is how many are printed here, so I have at least gotten the gist. Most of the letters were sent in 1903–4, with a final one dated 1908, from various locations on Rilke’s European travels.

Without Saints: Essays by Christopher Locke: Fifteen flash essays present shards of a life story. Growing up in New Hampshire, Locke encountered abusive schoolteachers and Pentecostal church elders who attributed his stuttering to demon possession and performed an exorcism. By age 16, small acts of rebellion had ceded to self-harm, and his addictions persisted into adulthood. Later, teaching poetry to prisoners, he realized that he might have been in their situation had he been caught with drugs. The complexity of the essays advances alongside the chronology. Weakness of body and will is a recurrent element.

Without Saints: Essays by Christopher Locke: Fifteen flash essays present shards of a life story. Growing up in New Hampshire, Locke encountered abusive schoolteachers and Pentecostal church elders who attributed his stuttering to demon possession and performed an exorcism. By age 16, small acts of rebellion had ceded to self-harm, and his addictions persisted into adulthood. Later, teaching poetry to prisoners, he realized that he might have been in their situation had he been caught with drugs. The complexity of the essays advances alongside the chronology. Weakness of body and will is a recurrent element.

It’s just over five years since many of us were introduced to Wigtown and the ups and downs of running a bookshop there through Shaun Bythell’s

It’s just over five years since many of us were introduced to Wigtown and the ups and downs of running a bookshop there through Shaun Bythell’s

An indigenous human rights lawyer, Aguon is passionate about protecting his homeland of Guam, which is threatened by climate change and military expansion. His tender collage of autobiographical vignettes and public addresses inspires activism and celebrates beauty worth preserving. The U.S. Department of Defense’s plan to site more Marines and firing ranges on Guam will destroy more than 1,000 acres of limestone forest—home to endemic and endangered species, including the Mariana eight-spot butterfly. Aguon has been a lead litigator in appeals rising all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Rejecting fatalism, he endorses peaceful resistance. Two commencement speeches, poems, a eulogy and an interview round out the varied and heartfelt collection.

An indigenous human rights lawyer, Aguon is passionate about protecting his homeland of Guam, which is threatened by climate change and military expansion. His tender collage of autobiographical vignettes and public addresses inspires activism and celebrates beauty worth preserving. The U.S. Department of Defense’s plan to site more Marines and firing ranges on Guam will destroy more than 1,000 acres of limestone forest—home to endemic and endangered species, including the Mariana eight-spot butterfly. Aguon has been a lead litigator in appeals rising all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Rejecting fatalism, he endorses peaceful resistance. Two commencement speeches, poems, a eulogy and an interview round out the varied and heartfelt collection.

Marsh is a retired brain surgeon and the author of

Marsh is a retired brain surgeon and the author of  On the face of it, he wasn’t an obvious candidate, not someone you would worry about. Yet there was family history: both of Patterson’s parents lost their fathers to suicide. And there was a bizarre direct connection between their two Kansas-based families: her maternal grandmother’s best friend became her paternal grandfather’s secretary and mistress.

On the face of it, he wasn’t an obvious candidate, not someone you would worry about. Yet there was family history: both of Patterson’s parents lost their fathers to suicide. And there was a bizarre direct connection between their two Kansas-based families: her maternal grandmother’s best friend became her paternal grandfather’s secretary and mistress. Erin Moore has returned to her family’s rural home for Queen’s Birthday (now a dated reference, alas!), a long weekend in New Zealand’s winter. Not a time for carefree bank holiday feasting, this; Erin’s mother has advanced motor neurone disease and announces that she intends to die on Tuesday. Aunty Wynn has a plan for obtaining the necessary suicide drug; it’s up to Erin to choreograph the rest. “I was the designated party planner for this morbid final frolic, and the promise of new failures loomed. … The whole thing was looking more and more like the plot of a French farce, except it wasn’t funny.”

Erin Moore has returned to her family’s rural home for Queen’s Birthday (now a dated reference, alas!), a long weekend in New Zealand’s winter. Not a time for carefree bank holiday feasting, this; Erin’s mother has advanced motor neurone disease and announces that she intends to die on Tuesday. Aunty Wynn has a plan for obtaining the necessary suicide drug; it’s up to Erin to choreograph the rest. “I was the designated party planner for this morbid final frolic, and the promise of new failures loomed. … The whole thing was looking more and more like the plot of a French farce, except it wasn’t funny.” Drawing on her own family history, Morris has crafted an absorbing story set in Sarajevo in 1992, the first year of the Bosnian War. Zora, a middle-aged painter, has sent her husband, Franjo, and elderly mother off to England to stay with her daughter, Dubravka, confident that she’ll see out the fighting in the safety of their flat and welcome them home in no time. But things rapidly get much worse than she is prepared for. Phone lines are cut off, then the water, then the electricity. “We’re all refugees now, Zora writes to Franjo. We spend our days waiting for water, for bread, for humanitarian handouts: beggars in our own city.”

Drawing on her own family history, Morris has crafted an absorbing story set in Sarajevo in 1992, the first year of the Bosnian War. Zora, a middle-aged painter, has sent her husband, Franjo, and elderly mother off to England to stay with her daughter, Dubravka, confident that she’ll see out the fighting in the safety of their flat and welcome them home in no time. But things rapidly get much worse than she is prepared for. Phone lines are cut off, then the water, then the electricity. “We’re all refugees now, Zora writes to Franjo. We spend our days waiting for water, for bread, for humanitarian handouts: beggars in our own city.” The book aims to situate bisexuality historically and scientifically. The term “bisexual” has been around since the 1890s, with the Kinsey Scale and the Klein Grid early attempts to add nuance to a binary view. Shaw delights in the fact that the mother of the Pride movement in the 1970s, Brenda Howard, was bisexual. She also learns that “being behaviourally bisexual is commonplace in the animal kingdom,” with many species engaging in “sociosexual” behaviour (i.e., for fun rather than out of reproductive instinct). It’s thought that 83% of bisexuals are closeted, mostly due to restrictive laws or norms in certain parts of the world – those seeking asylum may be forced to “prove” bisexuality, which, as we’ve already seen, is a tough ask. And bisexuals can face “double discrimination” from the queer community.

The book aims to situate bisexuality historically and scientifically. The term “bisexual” has been around since the 1890s, with the Kinsey Scale and the Klein Grid early attempts to add nuance to a binary view. Shaw delights in the fact that the mother of the Pride movement in the 1970s, Brenda Howard, was bisexual. She also learns that “being behaviourally bisexual is commonplace in the animal kingdom,” with many species engaging in “sociosexual” behaviour (i.e., for fun rather than out of reproductive instinct). It’s thought that 83% of bisexuals are closeted, mostly due to restrictive laws or norms in certain parts of the world – those seeking asylum may be forced to “prove” bisexuality, which, as we’ve already seen, is a tough ask. And bisexuals can face “double discrimination” from the queer community. less-understood sense. One in 10,000 people have congenital anosmia, but many more than that experience it at some point in life (e.g., due to head trauma, or as an early sign of Parkinson’s disease), and awareness has shot up since it’s been acknowledged as a symptom of Covid. For some, it’s parosmia instead – smell distortions – which can almost be worse, with people reporting a constant odour of smoke or garbage, or that some of their favourite aromas, like coffee, were now smelling like faeces instead. Such was the case for Totaro.

less-understood sense. One in 10,000 people have congenital anosmia, but many more than that experience it at some point in life (e.g., due to head trauma, or as an early sign of Parkinson’s disease), and awareness has shot up since it’s been acknowledged as a symptom of Covid. For some, it’s parosmia instead – smell distortions – which can almost be worse, with people reporting a constant odour of smoke or garbage, or that some of their favourite aromas, like coffee, were now smelling like faeces instead. Such was the case for Totaro. This comes out from Abrams Press in the USA on 8 November and I’ll be reviewing it for Shelf Awareness, so I’ll just give a few brief thoughts for now. Barba is a poet and senior editor for New York Review Books. She has collected pieces from a wide range of American literature, including essays, letters and early travel writings as well as poetry, which dominates.

This comes out from Abrams Press in the USA on 8 November and I’ll be reviewing it for Shelf Awareness, so I’ll just give a few brief thoughts for now. Barba is a poet and senior editor for New York Review Books. She has collected pieces from a wide range of American literature, including essays, letters and early travel writings as well as poetry, which dominates.

A good case of nominative determinism – the author’s name is pronounced “leaf” – and fun connections abound: during the course of his year-long odyssey, he spends time plant-hunting with Jon Dunn and Sophie Pavelle, whose books featured earlier in my flora-themed summer reading:

A good case of nominative determinism – the author’s name is pronounced “leaf” – and fun connections abound: during the course of his year-long odyssey, he spends time plant-hunting with Jon Dunn and Sophie Pavelle, whose books featured earlier in my flora-themed summer reading:  I was fascinated by the concept behind this one. “In the spring of 1936 a writer planted roses” is Solnit’s refrain; from there sprawls a book that’s somehow about everything: botany, geology, history, politics and war – as well as, of course, George Orwell’s life and works (with significant overlap with the

I was fascinated by the concept behind this one. “In the spring of 1936 a writer planted roses” is Solnit’s refrain; from there sprawls a book that’s somehow about everything: botany, geology, history, politics and war – as well as, of course, George Orwell’s life and works (with significant overlap with the  The love and appreciation of natural beauty starts at home, and we are lucky here in West Berkshire to have a very good newspaper that still hosts a nature column (currently by beloved local author Nicola Chester). This collection of Newbury Weekly News articles spans 1979 to 1996, with the majority of the pieces from 1990–5. They were contributed by 17 authors, but most are by Lew Lewis (including under a pseudonym).

The love and appreciation of natural beauty starts at home, and we are lucky here in West Berkshire to have a very good newspaper that still hosts a nature column (currently by beloved local author Nicola Chester). This collection of Newbury Weekly News articles spans 1979 to 1996, with the majority of the pieces from 1990–5. They were contributed by 17 authors, but most are by Lew Lewis (including under a pseudonym). Rookie: Selected Poems by Caroline Bird (2022)

Rookie: Selected Poems by Caroline Bird (2022) Given my love of medical memoirs and my recent obsession with

Given my love of medical memoirs and my recent obsession with  It’s one minute to midnight in London. Two Brown sisters are awake and looking at the moon. A journey of the imagination takes them through the time zones to see the natural spectacles the world has to offer: polar bears hunting at the Arctic Circle, baby turtles scrambling for the sea on an Indian beach, humpback whales breaching in Hawaii, and much more. Each spread has no more than two short paragraphs of text to introduce the landscape and fauna and explain the threats each ecosystem faces due to human influence. As the girls return to London and the clock chimes to welcome in 22 April, Earth Day, the author invites us to feel kinship with the creatures pictured: “They’re part of us, and every breath we take. Our world is fragile and threatened – but still lovely. And now it’s the start of a new day: a day when I’ll speak about these wonders, shout them out”.

It’s one minute to midnight in London. Two Brown sisters are awake and looking at the moon. A journey of the imagination takes them through the time zones to see the natural spectacles the world has to offer: polar bears hunting at the Arctic Circle, baby turtles scrambling for the sea on an Indian beach, humpback whales breaching in Hawaii, and much more. Each spread has no more than two short paragraphs of text to introduce the landscape and fauna and explain the threats each ecosystem faces due to human influence. As the girls return to London and the clock chimes to welcome in 22 April, Earth Day, the author invites us to feel kinship with the creatures pictured: “They’re part of us, and every breath we take. Our world is fragile and threatened – but still lovely. And now it’s the start of a new day: a day when I’ll speak about these wonders, shout them out”.

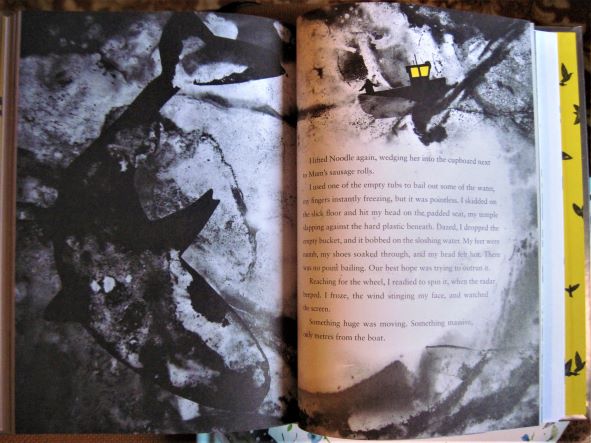

I could never have predicted when I read The Way Past Winter that Hargrave would become one of my favourite contemporary writers. Julia and her parents (and not forgetting the cat, Noodle) are off on an island adventure to Unst, in the north of Shetland, where her father will keep the lighthouse for a summer and her mother, a marine biologist, will search for the Greenland shark, a notably long-lived species she’s researching in hopes of discovering clues to human longevity – a cause close to her heart after her own mother’s death with dementia. Julia makes friends with Kin, a South Asian boy whose family run the island laundromat-cum-library. They watch stars and try to evade local bullies together. But one thing Julia can’t escape is her mother’s mental health struggle (late on named as bipolar: “Mum sometimes bounced around like Tigger, and other times she was mopey like Eeyore”). Julia thinks that if she can find the shark, it might fix her mother.

I could never have predicted when I read The Way Past Winter that Hargrave would become one of my favourite contemporary writers. Julia and her parents (and not forgetting the cat, Noodle) are off on an island adventure to Unst, in the north of Shetland, where her father will keep the lighthouse for a summer and her mother, a marine biologist, will search for the Greenland shark, a notably long-lived species she’s researching in hopes of discovering clues to human longevity – a cause close to her heart after her own mother’s death with dementia. Julia makes friends with Kin, a South Asian boy whose family run the island laundromat-cum-library. They watch stars and try to evade local bullies together. But one thing Julia can’t escape is her mother’s mental health struggle (late on named as bipolar: “Mum sometimes bounced around like Tigger, and other times she was mopey like Eeyore”). Julia thinks that if she can find the shark, it might fix her mother.

These college students’ bond is primarily physical, with an overlay of intellectual pretentiousness: they read to each other from the likes of Proust before they go to bed. Zambra, a Chilean poet and fiction writer, zooms in and out to spotlight each one’s other connections with friends and lovers and presage how the past will lead to separate futures. Already we see Julio thinking about how this time-limited relationship will be remembered in memory and in writing. The plot of a story Zambra references in this allusion-heavy work, “Tantalia” by Macedonio Fernández, provides the title: a couple buy a small plant to signify their love, but realize that maybe wasn’t a great idea given that plants can die.

These college students’ bond is primarily physical, with an overlay of intellectual pretentiousness: they read to each other from the likes of Proust before they go to bed. Zambra, a Chilean poet and fiction writer, zooms in and out to spotlight each one’s other connections with friends and lovers and presage how the past will lead to separate futures. Already we see Julio thinking about how this time-limited relationship will be remembered in memory and in writing. The plot of a story Zambra references in this allusion-heavy work, “Tantalia” by Macedonio Fernández, provides the title: a couple buy a small plant to signify their love, but realize that maybe wasn’t a great idea given that plants can die.