Wainwright & Women’s Prize Predictions

A quick second post from me today since tonight is the announcement of the winners of the Wainwright Prize and tomorrow, September 9th, will be the announcement of the winner of the Women’s Prize for Fiction.

Wainwright Prize

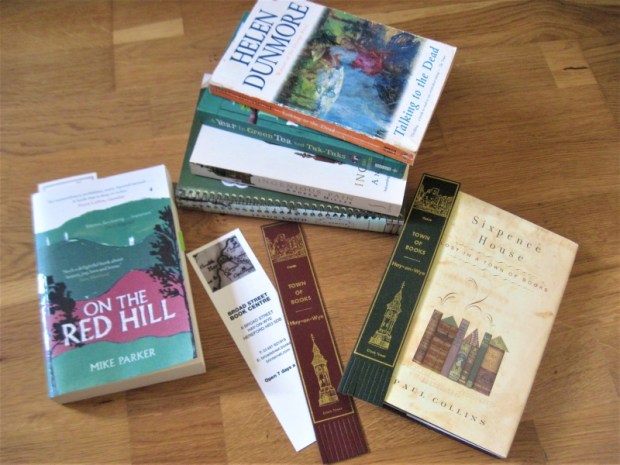

I’d read 10 of the nominees before the shortlists were announced (see my mini-reviews and predictions). Since then I’ve managed to read one-third each of the two other books on the UK nature writing shortlist (I correctly predicted four of the seven on it), The Frayed Atlantic Edge by David Gange and On the Red Hill by Mike Parker. This is the first year that I’ve read nearly an entire Wainwright shortlist before the announcement. Even though I’m only partway through it … for its interdisciplinary approach – folklore, geology, history, nature writing and more, all wrapped up in a rollicking, well-written travelogue as he kayaks down the western coasts of the British Isles – I feel Gange should win, but the judges pretty much never pick what I think is the best book.

I’ve only read one of the books from the new global conservation shortlist, so I can’t make any kind of informed prediction. However, as it was my top nonfiction book of last year, I’d be delighted to see Irreplaceable by Julian Hoffman win.

Women’s Prize

It feels like an age since this shortlist was announced. I think the reason for delaying the winner announcement from early June to September was for there to be a chance of the ceremony going ahead as normal (though of course it will be online after all); it also gave people a chance to read the Mantel. If I’m being cynical, it was to drum up more interest and publicity in this 25th anniversary year, but I think that may have backfired – I was quite excited early on (see my thoughts on the longlist; my wish list correctly predicted four of the six on the shortlist), but long ago wearied of hearing about the Prize. It seems forever ago that I read some of the nominees.

I don’t think Cruz or Haynes has a chance of winning, but I could see a case for any of the other four taking the Prize. I’d love for it to go to Jenny Offill’s sharp, timely Weather; I’d be perfectly happy for it to go to Bernardine Evaristo’s stylish, multivocal Girl, Woman, Other; I’d not be surprised at all if it went to Hilary Mantel’s accomplished epic, The Mirror & The Light, though I think her work more suited to the Booker Prize; and I personally did not rate Hamnet (which has something of a pandemic theme) but would still be glad to see some recognition for Maggie O’Farrell. Evaristo or O’Farrell thus seems like the safest bet to me.

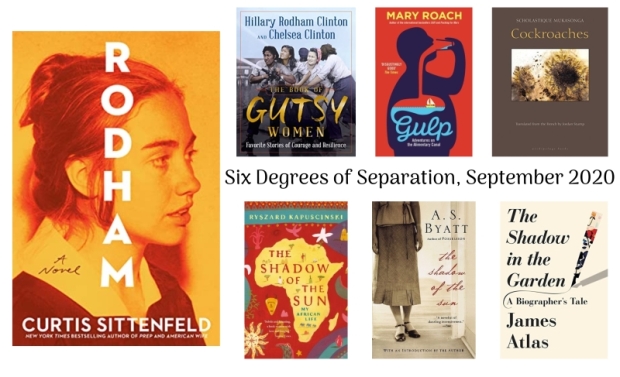

Six Degrees of Separation: From Rodham to The Shadow in the Garden

This month we’re all starting with Rodham. I reviewed this Marmite novel as part of the UK blog tour and was fully engaged in its blend of historical and fictional material. Ultimately, it doesn’t work as well as American Wife because we all know too much about Hillary Clinton, but it was a lot of fun for summer binge reading and is a must for any diehard Curtis Sittenfeld fan.

#1 Late last year I was sent an e-copy of The Book of Gutsy Women by Hillary and Chelsea Clinton for a potential review. I didn’t end up reading it at the time, but I still have it on my Kindle so might get to it someday. Like many, many books that have come out over the last few years, it’s full of mini-biographies of praiseworthy women from history. It seems a bit superfluous and overlong, but if the writing is up to snuff it might still be one to skim.

#2 Speaking of guts, earlier in the year I took perverse glee in reading Gulp by Mary Roach, a tour through the body’s digestive and excretory systems. Here’s a quick question to help you gauge whether the book is for you: does the prospect of three chapters on flatulence make you go “Yesssss!” or “Ew, no. Why?!” I’m in the former camp so, for the most part, found it fascinating. Footnotes on bizarre scientific studies are particularly hilarious.

#3 I’ve read two novels with “Roach” in the title; I didn’t want to use Ian McEwan as a link two months in a row, so I went with the other one: Cockroaches by Scholastique Mukasonga, which is also a good follow-on from #WITMonth as it was originally written in French. I reviewed this harrowing memoir of her Tutsi family’s slaughter during the Rwandan genocide of the 1990s for Wasafiri literary magazine in early 2018.

#4 One of the sunny/summer reads I featured last week was The Shadow of the Sun by Ryszard Kapuściński. One essay from the middle of the book is called “A Lecture on Rwanda,” which locates the seeds of the 1990s conflict in the independence struggle and peasant revolt of the late 1950s and early 1960s: the Hutu majority caste (85%) was composed of tenant farmers who rebelled against the cattle-owning Tutsi minority (14%).

#5 I’ve read another book by the title The Shadow of the Sun, this one a weak early novel by A.S. Byatt. It’s about a young woman struggling to get out from under the expectations and example of her father, a literary lion.

#6 Staying in the shadows … my top nonfiction read of 2017 was James Atlas’s memoir of the biographer’s profession, The Shadow in the Garden. The book deals with the nitty-gritty of archival research and how technology has changed it; story-telling strategies and the challenge of impartiality; and how we look for patterns in a life that might explain what, besides genius, accounts for a writer’s skill. Even though I knew little about his two main subjects, poet Delmore Schwartz and Saul Bellow, I found the book thoroughly enthralling.

Join us for #6Degrees of Separation if you haven’t already! (Hosted the first Saturday of each month by Kate W. of Books Are My Favourite and Best; see her intro post.)

Have you read any of my selections?

Are you tempted by any you didn’t know before?

Making Plans for a Return to Hay-on-Wye & A Book “Overhaul”

Somehow it’s been nearly 3.5 years since our last trip to Hay-on-Wye, the Book Town of Wales (I wrote about that April 2017 visit here). This coming weekend will be our seventh trip to Hay, one of our favorite places. We’ve booked an Airbnb in nearby English hamlet Cusop Dingle for two nights, so it’s a pretty short break, but longer than the weekend away we managed last month – reduced to only 36 hours by the cat’s poorly timed but ultimately minor one-day illness.

I’ve acquired many, many books from the free mall bookshop over the past year. (It’s now closed permanently, alas.) And I had no shortage of additional incomers during lockdown, via the unofficial Little Free Library I started and orders I placed with independent bookstores and publishers. So you could say I don’t need a book-buying trip to Hay. But 1) it’s never a question of need, is it? and 2) We want to continue to support the town, which will have been hit hard by temporary closures and by its annual literary festival being purely online this year.

I have no particular plans for what to buy this time, so will just see what takes my fancy. There are noticeably fewer bookshops than when we first started visiting Hay in 2004, but among the dozen or so remaining are some truly excellent shops like Addyman Books, the Hay Cinema Bookshop, and Booth’s Bookshop. Our best bargains last time were from the Oxfam charity shop and the honesty shelves around the castle, so those will likely be our first ports of call, and from there we’ll let whimsy be our guide. Saturday and Monday will be for wandering the town and book shopping, while Sunday will include countryside walks around Hay Bluff. We also hope to explore some eatery options we’ve not tried before.

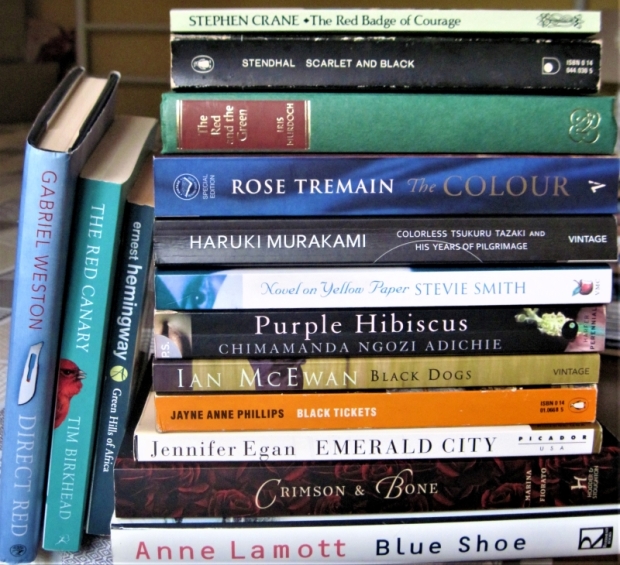

An Overhaul of Last Trip’s Book Purchases

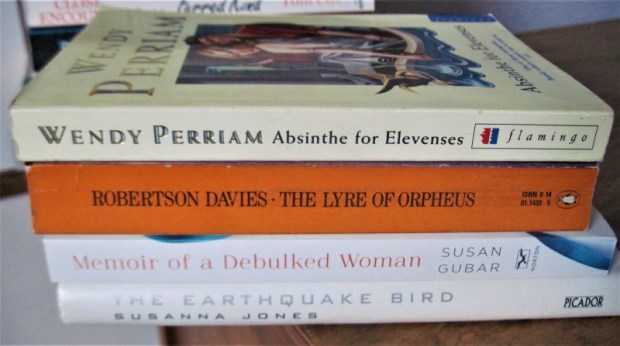

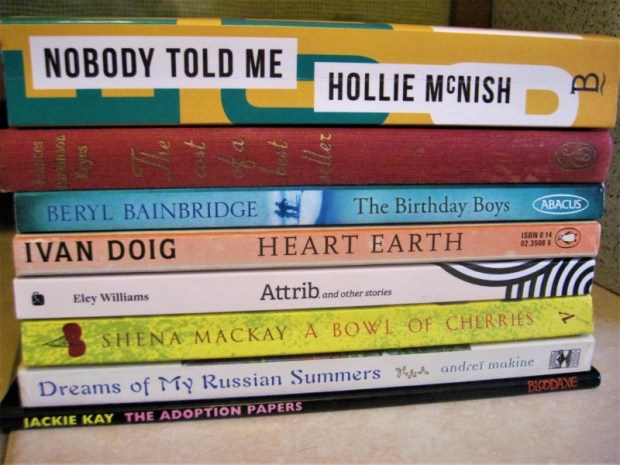

Simon of Stuck in a Book runs a regular blog feature he calls “The Overhaul,” where he revisits a book haul from some time ago and takes stock of what he’s read, what he still owns, etc. (here’s the most recent one). With his permission, I’m borrowing the title and format to look back at what I bought in Hay last time.

Date of haul: April 2017

Location: Hay-on-Wye

Number of books bought: 18

Had already read: (3/18)

- How to Age by Anne Karpf

- From Heaven Lake by Vikram Seth

- Tamara Drewe by Posy Simmonds – It’s on my shelf for rereading.

Have read since then: (5/18)

- Every Man for Himself by Beryl Bainbridge [resold]

- Fillets of Plaice by Gerald Durrell

- A Student of Weather by Elizabeth Hay (!)

- The Dead Beat by Marilyn Johnson

- Cats in May by Doreen Tovey

BUT also read from my hubby’s pile (not pictured):

- Sold for a Farthing by Clare Kipps

- All the Presidents’ Pastries by Roland Mesnier

- Second Nature by Michael Pollan

- A Shepherd’s Life by James Rebanks

DNFed: (3/18)

- Life & Times of Michael K by J.M. Coetzee [resold]

- We Were the Mulvaneys by Joyce Carol Oates – Might try this one again another time.

- Ghostwalk by Rebecca Stott [given away]

Resold unread: (1/18)

- Family and Friends by Anita Brookner – I’d added it to the Oxfam pile to make up a 5 for £1 stack, but then didn’t enjoy Booker winner Hotel du Lac enough to try another by Brookner.

Total still unread: 6

Total no longer owned: 4

This is not too bad a showing overall, though it does reveal my habit of buying books and letting them sit around for years unread. (Surely I’m not alone in this?!)

The six purchases still to read are two cat-themed anthologies for reading piecemeal, plus these four – two fiction and two non-:

- Talking to the Dead by Helen Dunmore

- Ingenious Pain by Andrew Miller

- Jesus Land by Julia Scheeres

- A Year in Green Tea and Tuk-Tuks by Rory Spowers

To force myself to get to them, these are the four I’ve packed for reading in the car and while in Hay. I’m also bringing, to read on location: 1) On the Red Hill by Mike Parker, a Wainwright Prize-shortlisted memoir about life in the Welsh countryside (I’m about 40 pages into it already); and 2) Sixpence House, which I’ve read several times before and consider among my absolute favorite books; it’s Paul Collins’s memoir about finding a temporary home and work among the bookshops of Hay.

I’ll be back on Tuesday with this year’s book haul plus photos and notes on how we found the town this time around. (But first, Six Degrees of Separation will post on Saturday while I’m away.)

Library Checkout, August 2020 & #WITMonth 2020, Part II

I’ve been volunteering at my local library twice a week since the start of the month, shelving and picking books off the shelves to fulfill reservations. Every time I’m there I spot more titles to add to my online wish list. It’s been a convenient excuse to return and pick up books, including book group sets. I was first in the queue for some brand-new releases this month.

Have you been able to borrow more books lately? Feel free to use the image above and leave a link to your blog in the comments if you’ve taken part in Library Checkout (which runs on the last Monday of every month), or tag me on Twitter and/or Instagram (@bookishbeck / #TheLibraryCheckout).

READ

- Queenie by Candice Carty-Williams

- Addition by Toni Jordan [book club choice]

- Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 by Cho Nam-Joo (reviewed below)

SKIMMED

- Dark, Salt, Clear: Life in a Cornish Fishing Town by Lamorna Ash

- The Butterfly Isles: A Summer in Search of Our Emperors and Admirals by Patrick Barkham

- Water Ways: A Thousand Miles along Britain’s Canals by Jasper Winn

CURRENTLY READING

- Close to Where the Heart Gives Out: A Year in the Life of an Orkney Doctor by Malcolm Alexander

- A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom by John Boyne

- Exciting Times by Naoise Dolan

- Maid: Hard Work, Low Pay, and a Mother’s Will to Survive by Stephanie Land

CURRENTLY SKIMMING

- Can You Hear Me? A Paramedic’s Encounters with Life and Death by Jake Jones

- Dear NHS: 100 Stories to Say Thank You, edited by Adam Kay

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

- The Girl with the Louding Voice by Abi Daré

- What Have I Done? An Honest Memoir about Surviving Postnatal Mental Illness by Laura Dockrill

- How to Be Both by Ali Smith

- Adults by Emma Jane Unsworth

- The Interestings by Meg Wolitzer

ON HOLD, TO BE PICKED UP

- Dependency by Tove Ditlevsen

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

- Persuasion by Jane Austen

- Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

- The Hungover Games by Sophie Heawood

- Just Like You by Nick Hornby

- 33 Meditations on Death: Notes from the Wrong End of Medicine by David Jarrett

- Sisters by Daisy Johnson

- Vesper Flights: New and Selected Essays by Helen Macdonald

- English Pastoral: An Inheritance by James Rebanks

- Such a Fun Age by Kiley Reid

- Dear Reader: The Comfort and Joy of Books by Cathy Rentzenbrink

- Jack by Marilynne Robinson

- Love and Other Thought Experiments by Sophie Ward

- The Courage to Care: A Call for Compassion by Christie Watson

- The Wild Silence by Raynor Winn

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- Apeirogon by Colum McCann – I only made it through the first 150 pages. A work that could have been very powerful if condensed instead sprawls into repetition and pretension. I still expect it to make the Booker shortlist, but not to win. I’ll add further thoughts closer to the time.

- That Reminds Me by Derek Owusu – I was expecting a memoir in verse about life in foster care; this is autofiction in dull fragments. I read the first 23 pages out of 113, waiting for it to get better.

RETURNED UNREAD

- Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston – I needed to make room for some new books on my account, so will request this at another time.

- Utopia Avenue by David Mitchell – I realized the subject matter didn’t draw me enough to read 500+ pages. So I passed it to my husband, a big Mitchell fan, and he read it happily, but mentioned that he didn’t find it compelling until about 2/3 through and he thought the combination of real-life and made-up figures (including from Mitchell’s previous oeuvre) was a bit silly.

- 1Q84 by Haruki Murakami – Again, I needed to make space on my card and was, unsurprisingly, daunted by the length of this 1,000+-page omnibus paperback. When I do try the novel, I’ll borrow it in its three separate volumes!

What appeals from my stacks?

My second choice for Women in Translation Month (after The Bitch by Pilar Quintana) was:

Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 by Cho Nam-Joo (2016)

[Translated from the Korean by Jamie Chang]

The title character is a sort of South Korean Everywoman whose experiences reveal the ways in which women’s lives are still constrained by that country’s patriarchal structures and traditions. She and her fellow female students and colleagues are subject to myriad microaggressions, from being served cafeteria lunches after the boys to being excluded from leadership of university clubs to having no recourse when security guards set up cameras in the female toilets at work. Jiyoung is wary of marriage and motherhood, afraid of derailing her budding marketing career, and despite her determination to do things differently she is disappointed at how much she has to give up when she has her daughter. “Her career potential and areas of interest were being limited just because she had a baby.”

The title character is a sort of South Korean Everywoman whose experiences reveal the ways in which women’s lives are still constrained by that country’s patriarchal structures and traditions. She and her fellow female students and colleagues are subject to myriad microaggressions, from being served cafeteria lunches after the boys to being excluded from leadership of university clubs to having no recourse when security guards set up cameras in the female toilets at work. Jiyoung is wary of marriage and motherhood, afraid of derailing her budding marketing career, and despite her determination to do things differently she is disappointed at how much she has to give up when she has her daughter. “Her career potential and areas of interest were being limited just because she had a baby.”

The prose is flat, with statistics about women’s lives in Korea unnaturally inserted in the text. Late on we discover there’s a particular reason for the clinically detached writing, but it’s not enough to fully compensate for a dull style. I also found the translation shaky in places, e.g. “She cautiously mentioned shop sales … to the mother who’d dropped by at home to make dinner” and “Jiyoung made it home safely on her boyfriend’s back, but their relationship didn’t.” I most liked Jiyoung’s entrepreneurial mother, who occasionally shows her feisty spirit: “The porridge shop was my idea, and I bought the apartment. And the children raised themselves. Yes, you’ve made it, but you didn’t do it all by yourself,” she says to her husband. “Run wild!” she exhorts Jiyoung, but the system makes that vanishingly difficult.

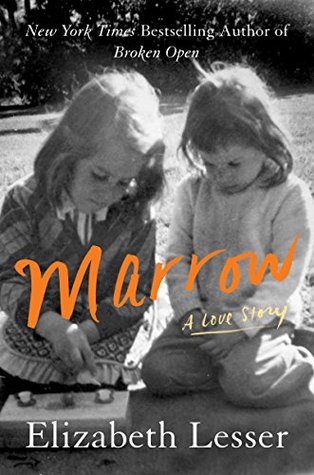

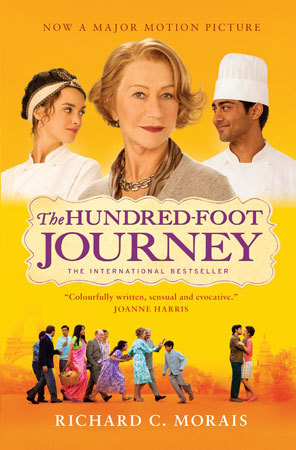

#17–18: Marrow & The Hundred-Foot Journey

Almost there! Today I have a family memoir about the repercussions of cancer and a novel about an Indian chef who becomes a guardian of traditional French cuisine.

Marrow: A Love Story by Elizabeth Lesser (2016)

(20 Books of Summer, #17) I put this on the pile for my foodie-themed summer reading challenge because a marrow is an overgrown courgette (zucchini), but of course bone marrow is also eaten and is what is being referred to here. When they were in middle age and Lesser’s younger sister Maggie had a recurrence of her lymphoma, the author was identified as a perfect match to donate bone marrow. She charts the ups and downs of Maggie’s treatment but also goes deep into their family history: parents who rejected the supernatural in reaction to her mother’s Christian Science upbringing; a quartet of sisters who competed for love and attention; and different approaches to life – Maggie was a back-to-the-land Vermont farmer, nurse and botanical artist, while Elizabeth had bucked the trend by moving to New York City and exploring spirituality (she co-founded the Omega Institute, a holistic retreat center).

(20 Books of Summer, #17) I put this on the pile for my foodie-themed summer reading challenge because a marrow is an overgrown courgette (zucchini), but of course bone marrow is also eaten and is what is being referred to here. When they were in middle age and Lesser’s younger sister Maggie had a recurrence of her lymphoma, the author was identified as a perfect match to donate bone marrow. She charts the ups and downs of Maggie’s treatment but also goes deep into their family history: parents who rejected the supernatural in reaction to her mother’s Christian Science upbringing; a quartet of sisters who competed for love and attention; and different approaches to life – Maggie was a back-to-the-land Vermont farmer, nurse and botanical artist, while Elizabeth had bucked the trend by moving to New York City and exploring spirituality (she co-founded the Omega Institute, a holistic retreat center).

By including unedited “field notes” Maggie wrote periodically, Lesser recreates the drama and heartache of the cancer journey. She also muses a lot about attempts to repair family relationships through honest conversations and therapy. “Marrow” is not just a literal substance but also a metaphor for getting to the heart of what matters in life. I expect this memoir will be too New Age-y for many readers, but I appreciated its insights and the close sister bonds. I also loved the deckle edge and Maggie’s botanical prints on the endpapers. Recommended to fans of Elizabeth Gilbert and Anne Lamott.

Source: A clearance book from Blackwell’s in Oxford (bought on a trip with Annabel last summer)

My rating:

The Hundred-Foot Journey by Richard C. Morais (2008)

(20 Books of Summer, #18) From the acknowledgments I learned that this was written specifically to be filmed by the author’s friend Ismail Merchant; though Merchant died in 2005, it’s no surprise that it went on to become a well-received 2014 movie. I think the story probably worked better on the big screen, what with the Indian and French settings, the swirls of color and the bustle of restaurant kitchens. Still, I’d forgotten enough about the story line to enjoy the book, too.

(20 Books of Summer, #18) From the acknowledgments I learned that this was written specifically to be filmed by the author’s friend Ismail Merchant; though Merchant died in 2005, it’s no surprise that it went on to become a well-received 2014 movie. I think the story probably worked better on the big screen, what with the Indian and French settings, the swirls of color and the bustle of restaurant kitchens. Still, I’d forgotten enough about the story line to enjoy the book, too.

Hassan Haji, the narrator, is born in Mumbai, one of six children of a restaurateur, and has his interest in other food cultures awakened early by a memorable French meal (a common experience in several other books I’ve reviewed this summer: Kitchen Confidential, How to Love Wine and Tender at the Bone). After his mother’s death, the extended family relocates to London and then to provincial France. Stranded in Lumière by a car breakdown, the family decides to stay, opening a curry house across from a fine dining establishment run by Gertrude Mallory. Madame Mallory engages in a battle of wills with the uncouth new arrivals. It nearly takes a tragedy for her to get over her snobbishness and xenophobia and realize Hassan has a perfect palate. She takes him on as an apprentice and he makes the title’s 100-foot journey across the street to join her staff.

The film was undoubtedly a Helen Mirren vehicle, and the Lumière material from the middle of the book holds the most interest. The remainder goes more melancholy as Hassan loses many family members and colleagues and deplores the rise of French bureaucracy and fads like molecular gastronomy. Although he eventually earns a third Michelin star for his Paris restaurant, the 40-year time span means that the warm ending somewhat loses its luster. (I can’t remember if the film went so far into the future.) A pleasant summer read nonetheless.

Source: Free from a neighbor

My rating:

Mario Batali is the book’s presiding imp. In 2002–3, Buford was an unpaid intern in the kitchen of Batali’s famous New York City restaurant, Babbo, which serves fancy versions of authentic Italian dishes. It took 18 months for him to get so much as a thank-you. Buford’s strategy was “be invisible, be useful, and eventually you’ll be given a chance to do more.”

Mario Batali is the book’s presiding imp. In 2002–3, Buford was an unpaid intern in the kitchen of Batali’s famous New York City restaurant, Babbo, which serves fancy versions of authentic Italian dishes. It took 18 months for him to get so much as a thank-you. Buford’s strategy was “be invisible, be useful, and eventually you’ll be given a chance to do more.” I was delighted to learn that this year Buford released a sequel of sorts, this one about French cuisine: Dirt. It’s on my wish list.

I was delighted to learn that this year Buford released a sequel of sorts, this one about French cuisine: Dirt. It’s on my wish list. Along with an agricultural center, the American Baptist missionaries were closely associated with a hospital, Hôpital le Bon Samaritain, run by amateur archaeologist Dr. Hodges and his family. Although Apricot and her two younger sisters were young enough to adapt easily to life in a developing country, they were disoriented each time the family returned to California in between assignments. Their bonds were shaky due to her father’s temper, her parents’ rocky relationship, and the jealousy provoked over almost adopting a Haitian baby girl.

Along with an agricultural center, the American Baptist missionaries were closely associated with a hospital, Hôpital le Bon Samaritain, run by amateur archaeologist Dr. Hodges and his family. Although Apricot and her two younger sisters were young enough to adapt easily to life in a developing country, they were disoriented each time the family returned to California in between assignments. Their bonds were shaky due to her father’s temper, her parents’ rocky relationship, and the jealousy provoked over almost adopting a Haitian baby girl. We Were the Mulvaneys by Joyce Carol Oates (oats!)

We Were the Mulvaneys by Joyce Carol Oates (oats!)

Of course, not all of my selections were explicitly food-related; others simply had food words in their titles (or, as above, in the author’s name). Of these, my favorite was a reread,

Of course, not all of my selections were explicitly food-related; others simply had food words in their titles (or, as above, in the author’s name). Of these, my favorite was a reread,

Maria Magdalena Theotoky is a 23-year-old graduate student at the College of St. John and the Holy Ghost (nicknamed “Spook”) in Toronto. She slept with her advisor, Clement Hollier, precisely once in his office last term. Two events spark the plot: the return of Brother John Parlabane, an ex-monk and -drug addict, and the death of Francis Cornish, a local patron of the arts. Parlabane becomes a university parasite, sleeping on couches and hitting up Maria, Hollier and Anglican priest Simon Darcourt for money. Along with Darcourt and Hollier, Urquhart McVarish, Hollier’s lecherous academic rival, is a third co-executor of Cornish’s artworks and manuscripts. Rumor has it the collection includes a lost manuscript by François Rabelais, the subject of Maria’s research, and Hollier and McVarish fight over it.

Maria Magdalena Theotoky is a 23-year-old graduate student at the College of St. John and the Holy Ghost (nicknamed “Spook”) in Toronto. She slept with her advisor, Clement Hollier, precisely once in his office last term. Two events spark the plot: the return of Brother John Parlabane, an ex-monk and -drug addict, and the death of Francis Cornish, a local patron of the arts. Parlabane becomes a university parasite, sleeping on couches and hitting up Maria, Hollier and Anglican priest Simon Darcourt for money. Along with Darcourt and Hollier, Urquhart McVarish, Hollier’s lecherous academic rival, is a third co-executor of Cornish’s artworks and manuscripts. Rumor has it the collection includes a lost manuscript by François Rabelais, the subject of Maria’s research, and Hollier and McVarish fight over it.

Adichie filters an epic account of Nigeria’s civil war through the experience of twin sisters, Olanna and Kainene, and those closest to them. The wealthy chief’s daughters from Lagos drift apart: Olanna goes to live with Odenigbo, a math professor; Kainene is a canny businesswoman with a white lover, Richard Churchill, who is fascinated by Igbo art and plans to write a book about his experiences in Africa. Gradually, though, he realizes that the story of Biafra is not his to tell.

Adichie filters an epic account of Nigeria’s civil war through the experience of twin sisters, Olanna and Kainene, and those closest to them. The wealthy chief’s daughters from Lagos drift apart: Olanna goes to live with Odenigbo, a math professor; Kainene is a canny businesswoman with a white lover, Richard Churchill, who is fascinated by Igbo art and plans to write a book about his experiences in Africa. Gradually, though, he realizes that the story of Biafra is not his to tell. Kapuściński was a foreign correspondent in Africa for 40 years and lent his name to an international prize for literary reportage. This book of essays spans several decades and lots of countries, yet feels like a cohesive narrative. The author sees many places right on the cusp of independence or in the midst of coup d’états – including Nigeria, a nice tie-in to the Adichie. Living among the people rather than removed in some white enclave, he develops a voice that is surprisingly undated and non-colonialist. While his presence as the observer is undeniable – especially when he falls ill with malaria and then tuberculosis – he lets the situation on the ground take precedence over the memoir aspect. I’m only halfway through, but I fully expect this to stand out as one of the best travel books I’ve ever read.

Kapuściński was a foreign correspondent in Africa for 40 years and lent his name to an international prize for literary reportage. This book of essays spans several decades and lots of countries, yet feels like a cohesive narrative. The author sees many places right on the cusp of independence or in the midst of coup d’états – including Nigeria, a nice tie-in to the Adichie. Living among the people rather than removed in some white enclave, he develops a voice that is surprisingly undated and non-colonialist. While his presence as the observer is undeniable – especially when he falls ill with malaria and then tuberculosis – he lets the situation on the ground take precedence over the memoir aspect. I’m only halfway through, but I fully expect this to stand out as one of the best travel books I’ve ever read. Berne, something of a one-hit wonder, is not among the more respected Women’s Prize alumni – look at the writers she was up against in the shortlist and you have to marvel that she was considered worthier than Barbara Kingsolver (The Poisonwood Bible) and Toni Morrison (Paradise). However, I enjoyed this punchy tale. Marsha remembers the summer of 1972, when her father left her mother for Aunt Ada and news came of a young boy’s sexual assault and murder in the woods behind a mall. “If you hadn’t known what had happened in our neighborhood, the street would have looked like any other suburban street in America.”

Berne, something of a one-hit wonder, is not among the more respected Women’s Prize alumni – look at the writers she was up against in the shortlist and you have to marvel that she was considered worthier than Barbara Kingsolver (The Poisonwood Bible) and Toni Morrison (Paradise). However, I enjoyed this punchy tale. Marsha remembers the summer of 1972, when her father left her mother for Aunt Ada and news came of a young boy’s sexual assault and murder in the woods behind a mall. “If you hadn’t known what had happened in our neighborhood, the street would have looked like any other suburban street in America.” Just as the Berne is a coming-of-age story masquerading as a mystery, from the title and cover this looked like it would be chick lit, but – though it has an overall breezy tone – it’s actually pretty chewy New York City literary fiction that should please fans of

Just as the Berne is a coming-of-age story masquerading as a mystery, from the title and cover this looked like it would be chick lit, but – though it has an overall breezy tone – it’s actually pretty chewy New York City literary fiction that should please fans of  Karl Ove Knausgaard turned his pretty ordinary life into thousands of pages of autofiction that many readers have found addictive. Adrian valiantly grapples with his six-volume exploration of identity, examining the treatment of time and the dichotomies of intellect versus emotions, self versus other, and life versus fiction. She marvels at the ego that could sustain such a project, and at the seemingly rude decision to use all real names (whereas in her own family memoir she assigned aliases to most major figures). At many points she finds the character of “Karl Ove” insufferable, especially when he’s a teenager in Book 4, and the books’ prose dull. Knausgaard’s focus on male novelists and his stereotypical treatment of feminine qualities, here and in his other work, frequently madden her.

Karl Ove Knausgaard turned his pretty ordinary life into thousands of pages of autofiction that many readers have found addictive. Adrian valiantly grapples with his six-volume exploration of identity, examining the treatment of time and the dichotomies of intellect versus emotions, self versus other, and life versus fiction. She marvels at the ego that could sustain such a project, and at the seemingly rude decision to use all real names (whereas in her own family memoir she assigned aliases to most major figures). At many points she finds the character of “Karl Ove” insufferable, especially when he’s a teenager in Book 4, and the books’ prose dull. Knausgaard’s focus on male novelists and his stereotypical treatment of feminine qualities, here and in his other work, frequently madden her. Jones also considers the precedents of wilderness literature and the 1990s memoir boom that paved the way for Wild. I most enjoyed this middle section, which, like Mary Karr’s The Art of Memoir, surveys some of the key publications from a burgeoning genre. Another key point of reference is Vivian Gornick, who draws a distinction between “the situation” (the particulars or context) and “the story” (the message) – sometimes the map or message comes first, and sometimes you only discover it as you go along.

Jones also considers the precedents of wilderness literature and the 1990s memoir boom that paved the way for Wild. I most enjoyed this middle section, which, like Mary Karr’s The Art of Memoir, surveys some of the key publications from a burgeoning genre. Another key point of reference is Vivian Gornick, who draws a distinction between “the situation” (the particulars or context) and “the story” (the message) – sometimes the map or message comes first, and sometimes you only discover it as you go along. As in

As in  Kingsolver may not be well known for her poetry, but this is actually her second collection of verse after the bilingual Another America/Otra America (1992). The opening segment, “How to Fly,” is full of folk wisdom from nature and the body’s intuitive knowledge. “Pellegrinaggio” is a set of travel poems about accompanying her Italian mother-in-law back to her homeland. “This Is How They Come Back to Us” is composed of elegies for the family’s dead; four shorter remaining sections are inspired by knitting, literature, daily life, and concern for the environment. As with

Kingsolver may not be well known for her poetry, but this is actually her second collection of verse after the bilingual Another America/Otra America (1992). The opening segment, “How to Fly,” is full of folk wisdom from nature and the body’s intuitive knowledge. “Pellegrinaggio” is a set of travel poems about accompanying her Italian mother-in-law back to her homeland. “This Is How They Come Back to Us” is composed of elegies for the family’s dead; four shorter remaining sections are inspired by knitting, literature, daily life, and concern for the environment. As with  The day starts at 5 a.m. with Justine going for a run, despite a recent heart health scare, and spends time with retirees, an engaged couple spending most of their time in bed, a 16-year-old kayaker, a woman with dementia, and more. We see different aspects of family dynamics as we revisit a previous character’s child, spouse or sibling. I had to laugh at Milly picturing Don Draper during sex with Josh, and at Claire getting an hour to herself without the kids and having no idea what to do with it beyond clean up and make a cup of tea. Moss gets each stream-of-consciousness internal monologue just right, from a frantic mum to a sarcastic teen.

The day starts at 5 a.m. with Justine going for a run, despite a recent heart health scare, and spends time with retirees, an engaged couple spending most of their time in bed, a 16-year-old kayaker, a woman with dementia, and more. We see different aspects of family dynamics as we revisit a previous character’s child, spouse or sibling. I had to laugh at Milly picturing Don Draper during sex with Josh, and at Claire getting an hour to herself without the kids and having no idea what to do with it beyond clean up and make a cup of tea. Moss gets each stream-of-consciousness internal monologue just right, from a frantic mum to a sarcastic teen.