American Book Acquisitions and 2019 Reading Goals

We arrived in the UK on January 1, after an overnight flight from Baltimore. There was no midnight announcement, no complimentary champagne; nothing. Clearly I had my hopes too high. So we’re feeling a bit cheated out of our New Year’s Eve experience and will be doing a recreated countdown and toast when we have houseguests over for this Epiphany weekend.

It was a low-key, relaxing couple of weeks back in the States, the majority of it spent seeing family and friends. We also made it into D.C. to see the new Obama portraits. Mostly I enjoyed doing not a lick of work. And I acquired books, of course: a secondhand and remainder stack that, after my trade-in of some cast-off books, cost just $4; and a few ARCs I’m excited about.

2019 Goals

I’m feeling restless in my career, like if someone gave me permission to quit all my gigs I would do it tomorrow. But, of course, only a fool would do so with no plan to replace them with other remunerative work. The year is likely to involve a lot of rethinking for me as I evaluate which of my proofreading and writing jobs feel worthwhile, and what’s taking me in the direction I want to go (not that I currently know what that is).

Life is awfully hard to plan out. Reading is much easier! So here are my fairly modest reading goals for the year, some of them overlapping:

- I plan to reinstate the Classic and Doorstopper of the month features I ran in 2017, since otherwise I hardly ever read them. I’m starting with Annabel’s readalong of The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco, which is just over 500 pages but also conveniently falls into one of the below categories.

The doorstoppers I have around to choose from.

- I’ll make a second attempt at getting through some of the travel books and biographies I own, though I won’t hold myself to any particular target. At least five of each would be nice.

- I’m determined to up my literature in translation ratio. These are all the books I own that were originally published in other languages – pitiful! – but I will get hold of more through the library and publishers.

- Re-reading is something I undertake very reluctantly. I have friends who swear by it, but to me it can feel like a waste of time. Last year I re-read just four books: Little Women, Give Me Everything You Have, Crossing the Moon, and Diary of a Bookseller. In each case, on the second reading I rated the book a star lower. That suggests that, far from appreciating books more on a second reading, I have less patience with them and find more flaws! All the same, I’ve chosen four books to re-read in 2019. The Collins is a longtime favorite about moving to Hay-on-Wye; the Thomas is one of the books that first got me into reading memoirs. I’ve been let down by Lamott’s latest three books so wanted to go back to one of her spiritual classics; I’ve gotten into L’Engle’s writing for adults and want to revisit her most famous children’s book (which I don’t think I comprehended at age nine or whatever I was).

- I have a bad habit of racing through self-help and theology books rather than taking my time mulling over them and fully exploring how I might apply them in my life. This was especially true of The Artist’s Way, one of my bibliotherapy prescriptions. I started out with the aim of completing the daily “morning pages” of free writing (though for me they were ‘evening pages’; I’m not a morning person) and each chapter’s self-knowledge exercises. But soon I’d given up on the writing and contemplation and begun just reading the book straight through, which is not the point of it at all. So this year I mean to go back through the Cameron and Rubin books more mindfully, and use the McLaren devotional as it is intended, reading the recommended Bible passages alongside the weekly reflections.

What are some of your goals (reading-related or otherwise) for 2019?

Five Books about Cats

I always used to be more of a dog person than a cat person, even though we had both while I was growing up, but now I’m a dedicated cat owner and have tried out some related reading. You’ll notice I don’t rate any of these five books about cats particularly highly, whereas there have been a number of dog books I’ve given 4 stars (Dog Years by Mark Doty, Ordinary Dogs by Eileen Battersby, A Dog’s Life by Peter Mayle; even books that aren’t necessarily about dogs but reference life with them, like A Three Dog Life by Abigail Thomas and Travels with Charley by John Steinbeck). What’s with that? Maybe dog lovers don’t have to worry so much about striking a balance between a pet’s standoffishness and affection. Maybe dogs play a larger role in everyday human life and leave a more gaping hole when they shuffle off the canine coil. Still, I enjoyed aspects of or specific passages from each of the following.

The Guest Cat by Takashi Hiraide

The Guest Cat by Takashi Hiraide

As a cat-loving freelance writer who aspires to read more literature in translation, I thought from the blurb that this book could not be more perfect for me. I bought it in a charity shop one afternoon and started reading right away. It’s only 140 pages, so I finished within 24 hours, but felt at a distance from the story the whole time. Part of it might be the translation – the translator’s notes at the end explain some useful context about the late 1980s setting, but also conflate the narrator and the author in such a way that the book seems like an artless memoir rather than a novella. But the more basic problem for me is that there’s simply not enough about the cat. There’s plenty of architectural detail about the guesthouse the narrator and his wife rent on the grounds of a mansion, plenty of economic detail about the housing market…but the cat just doesn’t make enough of an impression. I’m at a bit of a loss to explain why this has been such a bestseller. Quite the disappointment.

My rating:

The Fur Person by May Sarton

The Fur Person by May Sarton

I’m a huge fan of May Sarton’s journals – in which various cats play supporting roles – so for a while I’d been hoping to come across a copy of this little novelty book from 1957, a childish fable about a tomcat who transforms from a malnourished Cat-About-Town to a spoiled Gentleman Cat. Luckily I managed to find a copy of this one plus the Lessing (see below) in the Nature section at Book Thing of Baltimore. In a preface to the 1978 edition Sarton reveals that Tom Jones was, indeed, a real cat, a stray she and her partner Judy Matlack adopted when they lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Wonderful coincidence: when they were on sabbatical in the early 1950s, they sublet the place to the Nabokovs, who looked after Tom while they were away!

I found this a bit lightweight overall, and the whole idea of a ‘fur person’ is a little strange – don’t we love cats precisely because they’re not people? Still, I enjoyed the proud cat’s Ten Commandments (e.g. “II. A Gentleman Cat allows no constraint of his person … III. A Gentleman Cat does not mew except in extremity”) and spotted my own domestic situation in this description: “while she [‘Gentle Voice’ = Judy] was away the other housekeeper [= Sarton] was sometimes quite absent-minded and even forgot his lunch once or twice because she sat for hours and hours in front of a typewriter, tapping out messages with her fingers.” The black-and-white illustrations by David Canright are a highlight.

I found this a bit lightweight overall, and the whole idea of a ‘fur person’ is a little strange – don’t we love cats precisely because they’re not people? Still, I enjoyed the proud cat’s Ten Commandments (e.g. “II. A Gentleman Cat allows no constraint of his person … III. A Gentleman Cat does not mew except in extremity”) and spotted my own domestic situation in this description: “while she [‘Gentle Voice’ = Judy] was away the other housekeeper [= Sarton] was sometimes quite absent-minded and even forgot his lunch once or twice because she sat for hours and hours in front of a typewriter, tapping out messages with her fingers.” The black-and-white illustrations by David Canright are a highlight.

My rating:

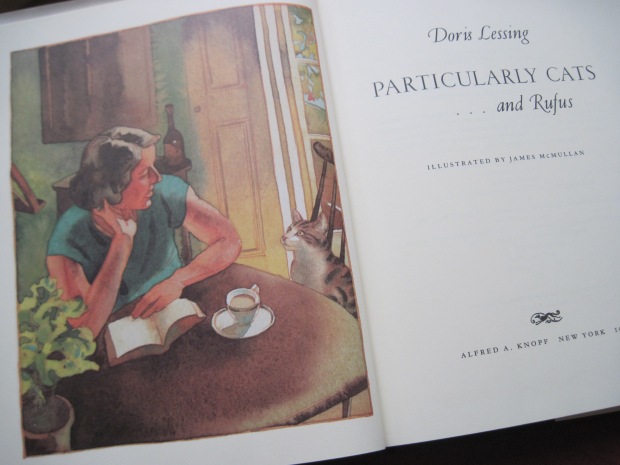

Particularly Cats…And Rufus by Doris Lessing

Particularly Cats…And Rufus by Doris Lessing

A book about cats that I would almost hesitate to recommend to cat lovers: it contains many a scene of kitty carnage, as well as some unenlightened resistance to spaying and neutering. Lessing grew up on a farm in Zimbabwe that was at one point overrun with about 40 cats. Her mother went away, expecting her father to have ‘taken care of them’ by the time she got back. He tried chloroform to start with, but it was too slow and ineffective; in the end he rounded them all up in a room and got out his WWI revolver. And that’s not the end of it; even into her adulthood in England Lessing balked at taking female cats in for surgery so would find occasionally herself saddled with unwanted litters of kittens that they decided had to be drowned. It’s really a remarkably unsentimental record of her dealings with cats.

That’s not to say there weren’t some cats she willingly and lovingly kept as pets, particularly a pair of rival females known simply as “black cat” and “grey cat,” and later a stray named Rufus who adopted her. But even with cherished felines she comes across as tough: “Anyway, she had to be killed and I decided that to keep cats in London was a mistake” or “I smacked grey cat” for bullying the black one. The very fact of not giving the pair names certainly quashes any notion of her as some cuddly cat lady. All the same, she was a dutiful nurse when black cat and Rufus fell ill. The book ends on a repentant note: “Knowing cats, a lifetime of cats, what is left is a sediment of sorrow quite different from that due to humans: compounded of pain for their helplessness, of guilt on behalf of us all.”

My favorite thing about the book is the watercolor illustrations by James McMullan.

My rating:

The Unadulterated Cat: A Campaign for Real Cats by Terry Pratchett

The Unadulterated Cat: A Campaign for Real Cats by Terry Pratchett

Like Douglas Adams or Monty Python, Terry Pratchett is, alas, a representative of the kind of British humor I just don’t get. But I rather enjoyed this small novelty book (bought for my husband for Christmas) all the same. For Pratchett, a “Real” cat is a non-pampered, tough-as-nails outdoor creature that hunts and generally does its own thing but also knows how to wrap its human servants around its paws. I like his idea of “cat chess” as a neighborhood-wide feline game of strategy, moving between carefully selected vantage points to keep an eye on the whole road yet avoid confrontation with other cats. It’s certainly true on our street. And this is quite a good summary of what cats do and why we put up with them:

What other animal gets fed, not because it’s useful, or guards the house, or sings, but because when it does get fed it looks pleased? And purrs. The purr is very important. It’s the purr that makes up for the Things Under the Bed, the occasional pungency, the 4 a.m. yowl.

My rating:

On Cats by Charles Bukowski

On Cats by Charles Bukowski

“In my next life I want to be a cat. To sleep 20 hours a day and wait to be fed. To sit around licking my ass.” I’d never read anything else by Bukowski, so I wasn’t sure quite what to expect from this book, which is mostly composed of previously unpublished poems and short prose pieces about the author’s multiple cats. The tone is an odd mixture of gruff and sentimental. Make no mistake: his cats were all Real cats, in line with the Pratchett model. A white Manx cat, for instance, had been shot, run over, and had his tail cut off. Another was named Butch Van Gogh Artaud Bukowski. You wouldn’t mess with a cat with a macho name like that, would you? My favorite passage is from “War Surplus,” about an exchange he and his wife had with a store clerk:

“what will the cats do if there is an explosion?”

“lady, cats are different than we are, they are of a lower order.”

“I think cats are better than we are,” I said.

the clerk looked at me. “we don’t have gas masks for cats.”

My rating:

Is there a terrific cat book out there that I haven’t read yet? I do hope so! Please add your suggestions in the comments.

My Favorite Nonfiction Reads of 2015

Without further ado, I present to you my 15 favorite non-fiction books read in 2015. I’m a memoir junkie so many of these fit under that broad heading, but I’ve dipped into other areas too. I give two favorites for each category, then count down my top 7 memoirs read this year.

Note: Only four of these were actually published in 2015; for the rest I’ve given the publication year. Many of them I’ve already previewed through the year, so – like I did yesterday for fiction – I’m limiting myself to two sentences per title: the first is a potted summary; the second tells you why you should read this book. (Links given to full reviews.)

Foodie Lit

A Homemade Life: Stories and Recipes from My Kitchen Table by Molly Wizenberg (2009): Wizenberg reflects on the death of her father Burg from cancer, time spent living in Paris, building a new life in Seattle, starting her food blog, and meeting her husband through it. Each brief autobiographical essay is perfectly formed and followed by a relevant recipe, capturing precisely how food is tied up with memories.

A Homemade Life: Stories and Recipes from My Kitchen Table by Molly Wizenberg (2009): Wizenberg reflects on the death of her father Burg from cancer, time spent living in Paris, building a new life in Seattle, starting her food blog, and meeting her husband through it. Each brief autobiographical essay is perfectly formed and followed by a relevant recipe, capturing precisely how food is tied up with memories.

Comfort Me with Apples: More Adventures at the Table by Ruth Reichl (2001): Reichl traces the rise of American foodie culture in the 1970s–80s (Alice Waters and Wolfgang Puck) through her time as a food critic for the Los Angeles Times, also weaving in personal history – from a Berkeley co-op with her first husband to a home in the California hills with her second after affairs and a sticky divorce. Throughout she describes meals in mouth-watering detail, like this Thai dish: “The hot-pink soup was dotted with lacy green leaves of cilantro, like little bursts of breeze behind the heat. … I took another spoonful of soup and tasted citrus, as if lemons had once gone gliding through and left their ghosts behind.”

Comfort Me with Apples: More Adventures at the Table by Ruth Reichl (2001): Reichl traces the rise of American foodie culture in the 1970s–80s (Alice Waters and Wolfgang Puck) through her time as a food critic for the Los Angeles Times, also weaving in personal history – from a Berkeley co-op with her first husband to a home in the California hills with her second after affairs and a sticky divorce. Throughout she describes meals in mouth-watering detail, like this Thai dish: “The hot-pink soup was dotted with lacy green leaves of cilantro, like little bursts of breeze behind the heat. … I took another spoonful of soup and tasted citrus, as if lemons had once gone gliding through and left their ghosts behind.”

Nature Books

Meadowland: The Private Life of an English Field by John Lewis-Stempel (2014): Lewis-Stempel is a proper third-generation Herefordshire farmer, but also a naturalist with a poet’s eye. Magical moments and lovely prose, as in “The dew, trapped in the webs of countless money spiders, has skeined the entire field in tiny silken pocket squares, gnomes’ handkerchiefs dropped in the sward.”

Meadowland: The Private Life of an English Field by John Lewis-Stempel (2014): Lewis-Stempel is a proper third-generation Herefordshire farmer, but also a naturalist with a poet’s eye. Magical moments and lovely prose, as in “The dew, trapped in the webs of countless money spiders, has skeined the entire field in tiny silken pocket squares, gnomes’ handkerchiefs dropped in the sward.”

Landmarks by Robert Macfarlane: This new classic of nature writing zeroes in on the language we use to talk about our environment, both individual words – which Macfarlane celebrates in nine mini-glossaries alternating with the prose chapters – and the narratives we build around places, via discussions of the work of nature writers he admires. Whether poetic (“heavengravel,” Gerard Manley Hopkins’s term for hailstones), local and folksy (“wonty-tump,” a Herefordshire word for a molehill), or onomatopoeic (on Exmoor, “zwer” is the sound of partridges taking off), his vocabulary words are a treasure trove.

Landmarks by Robert Macfarlane: This new classic of nature writing zeroes in on the language we use to talk about our environment, both individual words – which Macfarlane celebrates in nine mini-glossaries alternating with the prose chapters – and the narratives we build around places, via discussions of the work of nature writers he admires. Whether poetic (“heavengravel,” Gerard Manley Hopkins’s term for hailstones), local and folksy (“wonty-tump,” a Herefordshire word for a molehill), or onomatopoeic (on Exmoor, “zwer” is the sound of partridges taking off), his vocabulary words are a treasure trove.

Theology Books

Amazing Grace: A Vocabulary of Faith by Kathleen Norris (1998): In few-page essays, Norris gives theological words and phrases a rich, jargon-free backstory through anecdote, scripture and lived philosophy. This makes the shortlist of books I would hand to skeptics to show them there might be something to this Christianity nonsense after all.

Amazing Grace: A Vocabulary of Faith by Kathleen Norris (1998): In few-page essays, Norris gives theological words and phrases a rich, jargon-free backstory through anecdote, scripture and lived philosophy. This makes the shortlist of books I would hand to skeptics to show them there might be something to this Christianity nonsense after all.

My Bright Abyss: Meditation of a Modern Believer by Christian Wiman (2013): Seven years into a cancer journey, Wiman, a poet, gives an intimate picture of faith and doubt as he has lived with them in the shadow of death. Nearly every page has a passage that cuts right to the quick of what it means to be human and in interaction with other people and the divine.

My Bright Abyss: Meditation of a Modern Believer by Christian Wiman (2013): Seven years into a cancer journey, Wiman, a poet, gives an intimate picture of faith and doubt as he has lived with them in the shadow of death. Nearly every page has a passage that cuts right to the quick of what it means to be human and in interaction with other people and the divine.

General Nonfiction

Penelope Fitzgerald: A Life by Hermione Lee (2013): Although Penelope Fitzgerald always guarded literary ambitions, she was not able to pursue her writing wholeheartedly until she had reared three children and nursed her hapless husband through his last illness. This is a thorough and sympathetic appreciation of an underrated author, and another marvellously detailed biography from Lee.

Penelope Fitzgerald: A Life by Hermione Lee (2013): Although Penelope Fitzgerald always guarded literary ambitions, she was not able to pursue her writing wholeheartedly until she had reared three children and nursed her hapless husband through his last illness. This is a thorough and sympathetic appreciation of an underrated author, and another marvellously detailed biography from Lee.

Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End by Atul Gawande (2014): A surgeon’s essential guide to decision-making about end-of-life care, but also a more philosophical treatment of the question of what makes life worth living: When should we extend life, and when should we concentrate more on the quality of our remaining days than their quantity? The title condition applies to all, so this is a book everyone should read.

Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End by Atul Gawande (2014): A surgeon’s essential guide to decision-making about end-of-life care, but also a more philosophical treatment of the question of what makes life worth living: When should we extend life, and when should we concentrate more on the quality of our remaining days than their quantity? The title condition applies to all, so this is a book everyone should read.

Memoirs

The Year My Mother Came Back by Alice Eve Cohen: Wry and heartfelt, this is a wonderful memoir about motherhood in all its variations and complexities; the magic realism (Cohen’s dead mother keeps showing up) is an added delight. I recommend this no matter what sort of relationship, past or present, you have with your mother, especially if you’re also a fan of Anne Lamott and Abigail Thomas.

The Year My Mother Came Back by Alice Eve Cohen: Wry and heartfelt, this is a wonderful memoir about motherhood in all its variations and complexities; the magic realism (Cohen’s dead mother keeps showing up) is an added delight. I recommend this no matter what sort of relationship, past or present, you have with your mother, especially if you’re also a fan of Anne Lamott and Abigail Thomas.

- The Art of Memoir

by Mary Karr: There is a wealth of practical advice here, on topics such as choosing the right carnal details (not sexual – or not only sexual – but physicality generally), correcting facts and misconceptions, figuring out a structure, and settling on your voice. Karr has been teaching (and writing) memoirs at Syracuse University for years now, so she’s thought deeply about what makes them work, and sets her theories out clearly for readers at any level of familiarity.

by Mary Karr: There is a wealth of practical advice here, on topics such as choosing the right carnal details (not sexual – or not only sexual – but physicality generally), correcting facts and misconceptions, figuring out a structure, and settling on your voice. Karr has been teaching (and writing) memoirs at Syracuse University for years now, so she’s thought deeply about what makes them work, and sets her theories out clearly for readers at any level of familiarity.

A Circle of Quiet by Madeleine L’Engle (1971): In this account of a summer spent at her family’s Connecticut farmhouse, L’Engle muses on theology, purpose, children’s education, the writing life, the difference between creating stories for children and adults, neighbors and fitting into a community, and much besides. If, like me, you only knew L’Engle through her Wrinkle in Time children’s series, this journal should come as a revelation.

A Circle of Quiet by Madeleine L’Engle (1971): In this account of a summer spent at her family’s Connecticut farmhouse, L’Engle muses on theology, purpose, children’s education, the writing life, the difference between creating stories for children and adults, neighbors and fitting into a community, and much besides. If, like me, you only knew L’Engle through her Wrinkle in Time children’s series, this journal should come as a revelation.

-

Do No Harm: Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery by Henry Marsh (2014): “Terrible job, neurosurgery. Don’t do it.” – luckily for us, Henry Marsh reports back from the frontlines of brain surgery so we don’t have to. In my favorite passages, Marsh reflects on the mind-blowing fact that the few pounds of tissue stored in our heads could be the site of our consciousness, our creativity, our personhood – everything we traditionally count as the soul.

Do No Harm: Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery by Henry Marsh (2014): “Terrible job, neurosurgery. Don’t do it.” – luckily for us, Henry Marsh reports back from the frontlines of brain surgery so we don’t have to. In my favorite passages, Marsh reflects on the mind-blowing fact that the few pounds of tissue stored in our heads could be the site of our consciousness, our creativity, our personhood – everything we traditionally count as the soul.

I Hate to Leave This Beautiful Place by Howard Norman (2013): Norman has quickly become one of my favorite writers. You wouldn’t think these disparate autobiographical essays would fit together as a whole, given that they range in subject from Inuit folktales and birdwatching to a murder–suicide committed in Norman’s Washington, D.C. home and a girlfriend’s death in a plane crash, but somehow they do; after all, “A whole world of impudent detours, unbridled perplexities, degrading sorrow, and exacting joys can befall a person in a single season, not to mention a lifetime.”

I Hate to Leave This Beautiful Place by Howard Norman (2013): Norman has quickly become one of my favorite writers. You wouldn’t think these disparate autobiographical essays would fit together as a whole, given that they range in subject from Inuit folktales and birdwatching to a murder–suicide committed in Norman’s Washington, D.C. home and a girlfriend’s death in a plane crash, but somehow they do; after all, “A whole world of impudent detours, unbridled perplexities, degrading sorrow, and exacting joys can befall a person in a single season, not to mention a lifetime.”

Portrait of an Addict as a Young Man by Bill Clegg (2010): Through this book I followed literary agent Bill Clegg on dozens of taxi rides between generic hotel rooms and bar toilets and New York City offices and apartments; together we smoked innumerable crack pipes and guzzled dozens of bottles of vodka while letting partners and family members down and spiraling further down into paranoia and squalor. He achieves a perfect balance between his feelings at the time – being out of control and utterly enslaved to his next hit – and the hindsight that allows him to see what a pathetic figure he was becoming.

Portrait of an Addict as a Young Man by Bill Clegg (2010): Through this book I followed literary agent Bill Clegg on dozens of taxi rides between generic hotel rooms and bar toilets and New York City offices and apartments; together we smoked innumerable crack pipes and guzzled dozens of bottles of vodka while letting partners and family members down and spiraling further down into paranoia and squalor. He achieves a perfect balance between his feelings at the time – being out of control and utterly enslaved to his next hit – and the hindsight that allows him to see what a pathetic figure he was becoming.

And my overall favorite nonfiction book of the year:

1. The Light of the World by Elizabeth Alexander: In short vignettes, beginning afresh with every chapter, Alexander conjures up the life she lived with – and after the sudden death of – her husband Ficre Ghebreyesus, an Eritrean chef and painter. This book is the most wonderful love letter you could imagine, and no less beautiful for its bittersweet nature.

1. The Light of the World by Elizabeth Alexander: In short vignettes, beginning afresh with every chapter, Alexander conjures up the life she lived with – and after the sudden death of – her husband Ficre Ghebreyesus, an Eritrean chef and painter. This book is the most wonderful love letter you could imagine, and no less beautiful for its bittersweet nature.

What were some of your best nonfiction reads of the year?

We heard that The Bookshop Band would be playing at a free seasonal concert on Saturday night, so on something of a whim we planned a daytrip to Bath. Even though it wasn’t exactly on the way (my husband’s regular, feeble refrain), I take any opportunity of being in the Bath/Bristol area to make a pilgrimage to Bookbarn International. This was a delightful surprise since

We heard that The Bookshop Band would be playing at a free seasonal concert on Saturday night, so on something of a whim we planned a daytrip to Bath. Even though it wasn’t exactly on the way (my husband’s regular, feeble refrain), I take any opportunity of being in the Bath/Bristol area to make a pilgrimage to Bookbarn International. This was a delightful surprise since

I was an English and Religion major and studied abroad in England for my junior year in 2003–4. As I was getting ready to go overseas for that first time in the summer of 2003, Susan Allen Toth’s trilogy of travel memoirs, starting with My Love Affair with England, and Paul Collins’s Sixpence House whetted my appetite for travel in Great Britain and, in the case of the latter, made me determined to get to Hay-on-Wye, Wales as soon as I could. (I first visited in May 2004 and have gone back several times since.)

I was an English and Religion major and studied abroad in England for my junior year in 2003–4. As I was getting ready to go overseas for that first time in the summer of 2003, Susan Allen Toth’s trilogy of travel memoirs, starting with My Love Affair with England, and Paul Collins’s Sixpence House whetted my appetite for travel in Great Britain and, in the case of the latter, made me determined to get to Hay-on-Wye, Wales as soon as I could. (I first visited in May 2004 and have gone back several times since.) One of the most memorable books I read during my year abroad was Robert Elsmere by Mrs. Humphry Ward. It’s almost forgotten nowadays, but was a bestseller at its release in 1888. The story of a minister’s loss of faith and how it affects his marriage, it’s a stand-in for a whole faith-and-doubt subgenre that was wildly popular at the time. The novel is long, brooding and overwritten—in many ways it exemplifies the worst characteristics of the Victorian novel—but it resonated with my own crisis of faith and planted the seed for my Master’s thesis on women’s faith and doubt narratives in Victorian fiction.

One of the most memorable books I read during my year abroad was Robert Elsmere by Mrs. Humphry Ward. It’s almost forgotten nowadays, but was a bestseller at its release in 1888. The story of a minister’s loss of faith and how it affects his marriage, it’s a stand-in for a whole faith-and-doubt subgenre that was wildly popular at the time. The novel is long, brooding and overwritten—in many ways it exemplifies the worst characteristics of the Victorian novel—but it resonated with my own crisis of faith and planted the seed for my Master’s thesis on women’s faith and doubt narratives in Victorian fiction. Part of working through that ongoing crisis of faith was seeing other religions more objectively and being open to the similarities between them. I found Karen Armstrong’s comparative study of the Abrahamic faiths (Christianity, Judaism and Islam), A History of God, absolutely riveting when I read it in my senior year of college. It’s a classic.

Part of working through that ongoing crisis of faith was seeing other religions more objectively and being open to the similarities between them. I found Karen Armstrong’s comparative study of the Abrahamic faiths (Christianity, Judaism and Islam), A History of God, absolutely riveting when I read it in my senior year of college. It’s a classic. My academic conference career began and ended with one I attended the summer after college graduation. I adapted a paper I’d written about D.H. Lawrence’s new moral framework for sexuality and was accepted to present it at the D.H. Lawrence Society of North America’s annual conference in 2005, which that year was held in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Thankfully, I’ve mostly blanked out my actual paper presentation as part of a panel of three young people, but the trip as a whole was wonderful—it was my first time in the southwest, and the conference included great field trips to Lawrence’s ranch at Taos and the Georgia O’Keeffe museum. I prepared for the experience by reading David Lodge’s Small World, a paperback I’d plucked from the shelves of the bookstore where I worked part-time during my senior year. “A satire about the academic conference circuit? I’m there!” I thought, and since then David Lodge has become one of my two or three favorite authors.

My academic conference career began and ended with one I attended the summer after college graduation. I adapted a paper I’d written about D.H. Lawrence’s new moral framework for sexuality and was accepted to present it at the D.H. Lawrence Society of North America’s annual conference in 2005, which that year was held in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Thankfully, I’ve mostly blanked out my actual paper presentation as part of a panel of three young people, but the trip as a whole was wonderful—it was my first time in the southwest, and the conference included great field trips to Lawrence’s ranch at Taos and the Georgia O’Keeffe museum. I prepared for the experience by reading David Lodge’s Small World, a paperback I’d plucked from the shelves of the bookstore where I worked part-time during my senior year. “A satire about the academic conference circuit? I’m there!” I thought, and since then David Lodge has become one of my two or three favorite authors. It wasn’t until I returned to England to get my Master’s in 2005–6 that I really reclaimed reading as a leisure activity. The last couple years of college had been so busy I’d barely been able to cope with my assigned reading; I remember never making it very far in any paperback I picked up from the public library (like Charles Frazier’s Cold Mountain, which I’ve never gone back to). But the long, lonely evenings in Leeds had to be filled somehow, and the upstairs stacks of the magnificent

It wasn’t until I returned to England to get my Master’s in 2005–6 that I really reclaimed reading as a leisure activity. The last couple years of college had been so busy I’d barely been able to cope with my assigned reading; I remember never making it very far in any paperback I picked up from the public library (like Charles Frazier’s Cold Mountain, which I’ve never gone back to). But the long, lonely evenings in Leeds had to be filled somehow, and the upstairs stacks of the magnificent  In the partial year between finishing my Master’s and getting married back in England, I lived at home with my parents and worked part-time at a community college library. My evening shifts were often dead quiet, so I got plenty of reading done behind the circulation desk. One book I selected at random from the public library shelves, Abigail Thomas’s A Three Dog Life, had a big impact on me in 2007. The memoir tells of her husband’s traumatic brain injury and the aftermath. Thomas writes in a fragmentary, episodic format that felt fresh and jolted me. I wasn’t entirely sure I liked the style, but it sure was intriguing.

In the partial year between finishing my Master’s and getting married back in England, I lived at home with my parents and worked part-time at a community college library. My evening shifts were often dead quiet, so I got plenty of reading done behind the circulation desk. One book I selected at random from the public library shelves, Abigail Thomas’s A Three Dog Life, had a big impact on me in 2007. The memoir tells of her husband’s traumatic brain injury and the aftermath. Thomas writes in a fragmentary, episodic format that felt fresh and jolted me. I wasn’t entirely sure I liked the style, but it sure was intriguing.

I picked up Meredith Hall’s Without a Map around the same time, which cemented my interest in women’s life stories. Memoirs have been among my favorite genres ever since. Mark Doty’s exquisite Heaven’s Coast, which I read the following year, kickstarted my particular fascination with bereavement memoirs. Also, I think it was through following up his memoirs with his collections of poems that I first got into contemporary poetry.

I picked up Meredith Hall’s Without a Map around the same time, which cemented my interest in women’s life stories. Memoirs have been among my favorite genres ever since. Mark Doty’s exquisite Heaven’s Coast, which I read the following year, kickstarted my particular fascination with bereavement memoirs. Also, I think it was through following up his memoirs with his collections of poems that I first got into contemporary poetry.