Weatherglass Novella Prize 2026

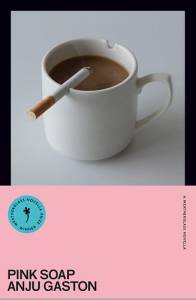

Following up on the shortlist news I shared in November: Ali Smith has chosen two winners for the second annual Weatherglass Novella Prize. Both of these have changed title since they were submitted as manuscripts (From the Smallest Things to The Hyena’s Daughter; Shougani to Pink Soap). I’m particularly interested in Jones’s novel about Mary Shelley and her sister and stepsister. And the Gaston has a brilliant cover!

Here’s what Ali Smith had to say about the winning books, courtesy of the Weatherglass Substack:

The Hyena’s Daughter by Jupiter Jones

(to be published in April 2026)

“This novella tells the far-too-untold story of a c19th sisterhood, that of the daughters of Mary Wollstonecraft: Fanny Imlay and Mary Shelley, the famed writer of Frankenstein, plus their step[-]sister Claire Clairmont. Are they the three graces? The fates? They’re women, as alive and breathing and rebellious and analytical as you and me, and well aware and critical of the hemmed-in nature they’re expected to accept as women of their time, a time of ‘a new way of thinking, a new-world independence, a revolutionary world.’

“This novella tells the far-too-untold story of a c19th sisterhood, that of the daughters of Mary Wollstonecraft: Fanny Imlay and Mary Shelley, the famed writer of Frankenstein, plus their step[-]sister Claire Clairmont. Are they the three graces? The fates? They’re women, as alive and breathing and rebellious and analytical as you and me, and well aware and critical of the hemmed-in nature they’re expected to accept as women of their time, a time of ‘a new way of thinking, a new-world independence, a revolutionary world.’

“It features their connection to Percy Bysshe Shelley – ‘how could we not love him, with his lofty ethics and words that flew like birds?’ – and many of the other contemporary poets and thinkers of the time. Pacy and assured, it turns its history to life from fragment to sensuous fragment. If the dead brought to life is to be Mary Shelley’s theme, this novella asks what the real source of life spirit is, the vital spark. This novella, full of detail and richesse, is a piece of vitality in itself.”

Pink Soap by Anju Gaston

(to be published in June 2026)

“‘I ask the internet the difference between something being too close to the bone and something being too close to home.’ This funny and terrifying book is a study of what and how things mean, and don’t, in our latest machine age. In it something unforgivable has happened. The main character in this novella, seemingly numbed but bristling with blade-sharp understanding, is only just holding things together and trying to work out how to heal. So she travels to Japan in a search for the other half of a fragmented family. Or is it the world itself that has fragmented?

“‘I ask the internet the difference between something being too close to the bone and something being too close to home.’ This funny and terrifying book is a study of what and how things mean, and don’t, in our latest machine age. In it something unforgivable has happened. The main character in this novella, seemingly numbed but bristling with blade-sharp understanding, is only just holding things together and trying to work out how to heal. So she travels to Japan in a search for the other half of a fragmented family. Or is it the world itself that has fragmented?

“Pink Soap examines the massive everyday pressures we’re all under with real wit and style. It is pristine, brilliant, smart beyond belief. I sense it becoming as much a classic for now as Plath’s The Bell Jar has been for the decades behind us.”

Submissions have already opened for the 2027 Prize. More information is here.

Weatherglass Books’ Second Annual Novella Prize Shortlist (#NovNov25)

Last year I attended an event at Foyles in London introducing the two joint winners of the inaugural Weatherglass Novella Prize, as chosen by Ali Smith. I later reviewed both Astraea by Kate Kruimink and Aerth by Deborah Tomkins, and interviewed Weatherglass Books co-founder and novelist Neil Griffiths. With his permission, I’m reproducing below the partial text of the Substack post in which he announced the shortlist for this second year of the award. Out of 170+ submissions, he and co-publisher Damian Lanigan chose a shortlist of four novellas, which have again been sent to Ali Smith for her to choose a winner in the new year. The winner will be published by Weatherglass Books. It’s clear that all four are publishable, though!

The shortlist is … in no particular order:

A BRIEF HISTORY OF WAR by Selma Carvalho is a piece of sensuous magnetic power and aliveness. It deals with questions of class, ethnicity and nationalism so close to the contemporary that this book almost shakes in your hands.

Two people sit by chance near each other on a bus in a world where the rise of political divisions is physical, palpable. They’re unalike in every way. Their attraction fizzes like a lit fuse. “What does it mean to be foreign, to think of another human being as foreign? Foreign from what?” It examines the closeness and distance between people, families, tribes, and the hair-trigger, hair-on-the-back-of-the-neck negotiations between people’s bodies.

Wise and contemporary, uncompromising and true, its edginess, and the fallout from desires, personal and social, is brilliantly conjured and conveyed.

FROM THE SMALLEST THINGS by Jupiter Jones tells the far-too-untold story of a c19th sisterhood, that of the daughters of Mary Wollstonecraft: Fanny Imlay and Mary Shelley, the famed writer of Frankenstein, plus their step-sister Claire Clairmont. Are they the three graces? The fates? They’re women, as alive and breathing and rebellious and analytical as you and me, and well aware and critical of the hemmed-in nature they’re expected to accept as women of their time, a time of “a new way of thinking, a new-world independence, a revolutionary world.”

It features their connection to Percy Bysshe Shelley – “how could we not love him, with his lofty ethics and words that flew like birds?” – and many of the other contemporary poets and thinkers of the time. Pacy and assured, it turns its history to life from fragment to sensuous fragment. If the dead brought to life is to be Mary Shelley’s theme, this novella asks what the real source of life spirit is, the vital spark. This book, full of detail and richesse, is a piece of vitality in itself.

Ali Smith at the Weatherglass event in September 2024.

SHOUGANI by Anju Gaston – what does it mean? “I ask the internet the difference between something being too close to the bone and something being too close to home.” This funny and terrifying book is a study of what and how things mean, and don’t, in our latest machine age. In it something unforgiveable has happened. The main character in this novella, seemingly numbed but bristling with blade-sharp understanding, is only just holding things together and trying to work out how to heal. So she travels to Japan in a search for the other half of a fragmented family. Or is it the world itself that has fragmented?

Shougani examines the massive everyday pressures we’re all under with real wit and style. It is pristine, brilliant, smart beyond belief. I sense it becoming as much a classic for now as Plath’s The Bell Jar has been for the decades behind us.

THE MARVELLOUS DINNER by Polly Tuckett

“A massacre of things just to produce a single dish”: this novella charts the terrible coming-apart of a marriage. A wife prepares a dinner for her husband on an important anniversary, a meal so laboured and elaborate that something’s wrong, something’s definitely up – more, something’s got to give.

This novella is a story of the fictions we call true in our lives, even though we know they’re hollow ceremonials. There’s a Mike Leigh touch to this unsettling book. Every mouthful is dangerous, precarious. It anatomises fuss and ceremony, examines the ritual and the real bullying in a relationship. It deals with madness and the mundane truth of fantasy. Is it love itself that’s a delusion in this tale of the ties that bind?

“So there we have it. Our four shortlisted titles,” Neil writes. “They are all extraordinary, all deserve to win, to be well published. It’s now down to Ali. Thank you to everyone who submitted. We’ve enjoyed reading all the entries. But especial thanks to Ali Smith for agreeing to be our judge in year one and now on-goingly; it’s a real privilege to have one the world’s most original writers helping us select what we commission.”

Which of the synopses entice you? I especially like the sound of From the Smallest Things and The Marvellous Dinner.

Interview with Neil Griffiths of Weatherglass Books (#NovNov24)

Back in September, I attended a great “The Future of the Novella” event in London, hosted by Weatherglass. I wrote about it here, and earlier this month I reviewed the first of the two winners of the inaugural Weatherglass Novella Prize, Astraea by Kate Kruimink*. Weatherglass Books co-founder and novelist Neil Griffiths kindly sent review copies of both winning books, and agreed to answer some questions over e-mail.

Back in September, I attended a great “The Future of the Novella” event in London, hosted by Weatherglass. I wrote about it here, and earlier this month I reviewed the first of the two winners of the inaugural Weatherglass Novella Prize, Astraea by Kate Kruimink*. Weatherglass Books co-founder and novelist Neil Griffiths kindly sent review copies of both winning books, and agreed to answer some questions over e-mail.

Samantha Harvey’s 136-page Orbital won the Booker Prize, the film adaptation of Claire Keegan’s Small Things Like These is in cinemas: Is the novella having a moment? If so, how do you account for its fresh prominence? Or has it always been a powerful form and we’re realizing it anew?

I do wonder whether Orbital is a novella, by which I mean, number of pages can be deceptive – there are a lot of words per page! I think it probably sneaks in under our Novella Prize max word count: under 40K. Also, I wonder whether Small Things like These would make it over our minimum 20K. I don’t think so. But what I think we can say is that there is something happening around length.

I do wonder whether Orbital is a novella, by which I mean, number of pages can be deceptive – there are a lot of words per page! I think it probably sneaks in under our Novella Prize max word count: under 40K. Also, I wonder whether Small Things like These would make it over our minimum 20K. I don’t think so. But what I think we can say is that there is something happening around length.

My co-founder of Weatherglass, Damian Lanigan, says this: “the novella is the form for our times: befitting our short attention spans, but also with its tight focus, with its singular atmosphere – it’s the ideal form for glimpsing something essential about the world and ourselves in an increasingly chaotic world.”

But then if we look over the history of the prose fiction over the last 200 hundred years, there are so many novellas that have defined an era: Turgenev’s Love, Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, Carr’s A Month in the Country, Orwell’s Animal Farm, Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.

Why did Weatherglass choose to focus on short books? Do economic and environmental factors come into it (short books = less paper = lower printing costs as well as fewer trees cut down)?

Economic and environmental factors play a role, but there is also craft. Writers need to ask themselves the question: does this story need to be this length, and the answer is, more often than not: no. I think constraints bring the best out of writers. If a novel comes in at 70K words, our first thought is to cut 10K. (I should say, my last novel, very kindly reviewed by yourself, was a whooping 190K words. It should have been 150K! Since then I’ve written two pieces of fiction, both under 35K.)

Economic and environmental factors play a role, but there is also craft. Writers need to ask themselves the question: does this story need to be this length, and the answer is, more often than not: no. I think constraints bring the best out of writers. If a novel comes in at 70K words, our first thought is to cut 10K. (I should say, my last novel, very kindly reviewed by yourself, was a whooping 190K words. It should have been 150K! Since then I’ve written two pieces of fiction, both under 35K.)

Neil Griffiths

We’ve heard about the bloating of films, that they’re something like 20% longer on average than they were 40 years ago; will books take the opposite trajectory? Can a one-sitting read compete with a film?

I don’t think I’ve ever read even the shortest novella in one sitting. I need time to reflect. I don’t think comparing the two forms is helpful because they require different things of us. Take music: Morton Feldman’s 2nd String Quartet is 5 hours long, without a break. I’d commit to that in the concert hall, but I couldn’t read for 5 hours without a break or sit through a film.

How did you bring Ali Smith on board as the judge for the first two years of the Weatherglass Novella Prize? There was a blind judging process and you ended up with an all-female shortlist in the inaugural year. Do you have a theory as to why?

Ali Smith

Damian kept saying Ali Smith would be the best judge and I kept saying “but how do we get to her?” Then someone told me they had her email address. I didn’t expect to get an answer. A ‘Yes’ came an hour later. She’s been wonderful to work with. And she’s enjoyed it so much she’s agreed to do it ongoingly.

I do think the shortlist question is an important one. Certainly we don’t have to ask ourselves any questions when it’s an all-female short list, but we would if it was all-male. What does that say? I don’t know why the strongest were by women.

Do you have any personal favourite novellas?

A Month in the Country might be the exemplar of the form for me. But there is a little-read novella by Tolstoy, Hadji Murat, which is also close to perfect. More contemporaneously, Gerald Murnane’s Border Districts. And I’m pleased to say: all three novellas we’re publishing from our inaugural prize are up there: Astraea, Aerth and We Hexed the Moon.

A Month in the Country might be the exemplar of the form for me. But there is a little-read novella by Tolstoy, Hadji Murat, which is also close to perfect. More contemporaneously, Gerald Murnane’s Border Districts. And I’m pleased to say: all three novellas we’re publishing from our inaugural prize are up there: Astraea, Aerth and We Hexed the Moon.

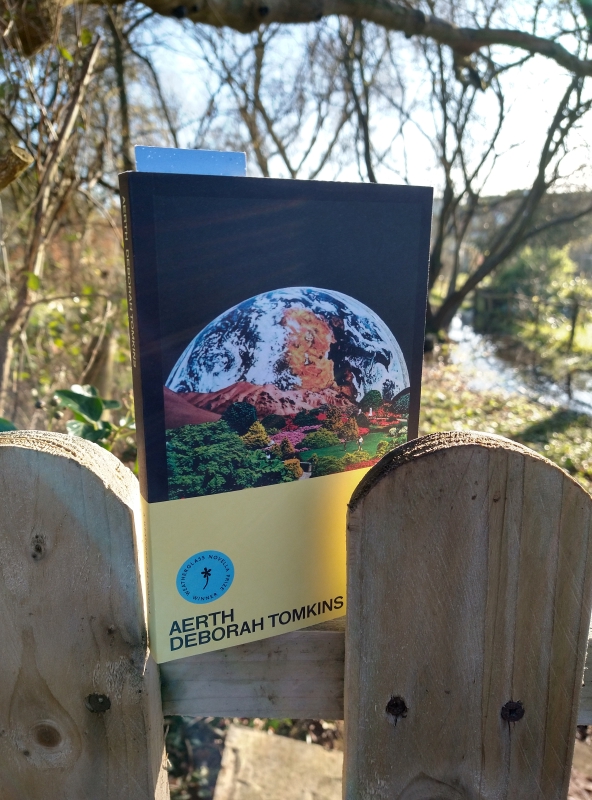

*Though it won’t be published until 25 January, I have a finished copy of the other winner, Aerth by Deborah Tomkins, a novella-in-flash set on alternative earths and incorporating second- and third-person narration and various formats. I’ve been enjoying it so far and hope to review it soon as my first recommendation for 2025.

Astraea by Kate Kruimink (Weatherglass Novella Prize) #NovNov24

Astraea by Kate Kruimink is one of two winners* of the inaugural Weatherglass Novella Prize, as chosen by Ali Smith. Back in September, I was introduced to it through Weatherglass Books’ “The Future of the Novella” event in London (my write-up is here).

Taking place within about a day and a half on a 19th-century convict ship bound for Australia, it is the intense story of a group of women and children chafing against the constraints men have set for them. The protagonist is just 15 years old and postpartum. Within a hostile environment, the women have created an almost cosy community based on sisterhood. They look out for each other; an old midwife can still bestow her skills.

The ship was their shelter, the small chalice carrying them through that which was inhospitable to human life. But there was no shelter for her there, she thought. There was only a series of confines between which she might move but never escape.

The ship’s doctor and chaplain distrust what they call the “conspiracy of women” and are embarrassed by the bodily reality of one going into labour, another tending to an ill baby, and a third haemorrhaging. They have no doubt they know what is best for their charges yet can barely be bothered to learn their names.

Indeed, naming is key here. The main character is effectively erased from the historical record when a clerk incorrectly documents her as Maryanne Maginn. Maryanne’s only “maybe-friend,” red-haired Sarah, has the surname Ward. “Astraea” is the name not just of the ship they travel on but also of a star goddess and a new baby onboard.

The drama in this novella arises from the women’s attempts to assert their autonomy. Female rage and rebellion meet with punishment, including a memorable scene of solitary confinement. A carpenter then constructs a “nice little locking box that will hold you when you sin, until you’re sorry for it and your souls are much recovered,” as he tells the women. They are all convicts, and now their discipline will become a matter of religious theatrics.

Given the limitations of setting and time and the preponderance of dialogue, I could imagine this making a powerful play. The novella length is as useful a framework as the ship itself. Kruimink doesn’t waste time on backstory; what matters is not what these women have done to end up here, but how their treatment is an affront to their essential dignity. Even in such a low page count, though, there are intriguing traces of the past and future, as well as a fleeting hint of homoeroticism. I would recommend this to readers of The Mercies by Kiran Millwood Hargrave, Devotion by Hannah Kent and Women Talking by Miriam Toews. And if you get a hankering to follow up on the story, you can: this functions as a prequel to Kruimink’s first novel, A Treacherous Country. (See also Cathy’s review.)

[115 pages]

With thanks to Weatherglass Books for the free copy for review.

*The other winner, Aerth by Deborah Tomkins, a novella-in-flash set on alternative earths, will be published in January. I hope to have a proof copy in hand before the end of the month to review for this challenge plus SciFi Month.

Get Ready for Novellas in November!

Novellas: “all killer, no filler,” as Joe Hill said. Hard to believe, but it’s now the FIFTH year that Cathy of 746 Books and I have been co-hosting Novellas in November as a month-long blogger/social media challenge celebrating the art of the short book. A novella is a book of 20,000 to 40,000 words, but because that’s hard for a reader to gauge, we tend to say anything under 200 pages (even nonfiction). I’m going to make it a personal challenge to limit myself to books of ~150 pages or less.

We’re keeping it simple this year with just the one buddy read, Orbital by Samantha Harvey. (Though we chose it weeks ago, its shortlisting for the Booker Prize is all the more reason to read it!) The UK hardback has 144 pages. Here’s part of the blurb to entice you:

“Six astronauts rotate in their spacecraft above the earth. … Together they watch their silent blue planet, circling it sixteen times, spinning past continents and cycling through seasons, taking in glaciers and deserts, the peaks of mountains and the swells of oceans. Endless shows of spectacular beauty witnessed in a single day. Yet although separated from the world they cannot escape its constant pull. News reaches them of the death of a mother, and with it comes thoughts of returning home. … They begin to ask, what is life without earth? What is earth without humanity?”

Please join us in reading it at any time between now and the end of November!

We won’t have any official themes or prompts, but you might want to start off the month with a My Year in Novellas retrospective looking at any novellas you have read since last NovNov, and finish it with a New to My TBR list based on what novellas others have tempted you to try in the future.

It’s always a busy month in the blogging world, what with Nonfiction November, German Literature Month, Margaret Atwood Reading Month and SciFi Month. Why not search your shelves and/or local library for novellas that could count towards multiple challenges?

From 1 November there will be a pinned post on my site from which you can join the link-up. Keep in touch via Twitter (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books), and feel free to use the terrific feature images Cathy has made plus our new hashtag, #NovNov24.

“The Future of the Novella”

On the 11th, at Foyles in London, I attended a perfect event to get me geared up for Novellas in November. Indie publisher Weatherglass Books and judge Ali Smith introduced us to the two winners she chose for the inaugural Weatherglass Novella Prize: Kate Kruimink’s Astraea (set on a 19th-century Australian convict ship), out now, and Deborah Tomkins’ Aerth (a sci-fi novella in flash set on alternative earths), coming out in January.

Ali Smith

We heard readings from both novellas, and Neil Griffiths and Damian Lanigan of Weatherglass told us some more about what they publish and the process of reading the prize submissions (blind!). Lanigan called the novella “a form for our times” and put this down not just to modern attention spans but to focus – the glimpse of something essential. He and Smith mentioned F. Scott Fitzgerald, Claire Keegan, Françoise Sagan and Muriel Spark as some of the masters of the novella form.

The effortlessly cool Smith spoke about the delight of spending weekend mornings – she writes during the week but gives herself the weekends off to read – in bed with a pot of coffee and a Weatherglass novella. She particularly enjoyed going into each book from the shortlist without any context and lamented that blurbs mean the story has to be, to some extent, given away to the reader. She said the ending of a novella has to land “like a cat, on its feet” (Griffiths then appended that it must also be ambiguous).

Kate Kruimink

Kruimink, who edits short stories for a magazine, explained that she thinks of Astraea as a long short story. She wrote it especially for this prize, within two months and for Ali Smith, as it were (she mentioned how formative How to Be Both was for her as a writer). Due to time and word limit constraints, she deliberately crafted a small character arc and didn’t do loads of research, though she had been looking into ships’ surgeons’ journals at the time. She has Irish convict ancestry but noted that this is not uncommon in Tasmania. Astraea is a “sneaky prequel” to her first novel, which has been published in Australia.

Deborah Tomkins

Aerth was originally titled First, Do No Harm, which had the potential to confuse those looking for a medical read. Aerth and Urth are different planets with parallels to our own. The novella tells the story of Magnus, an Everyman on a deeply forested planet heading into an Ice Age. Tomkins first wrote it for the Bath Prize in 2018 and was longlisted, then added to it. She initially sent the book to sci-fi publishers but was told it was not ‘sci-fi enough’.

Griffiths remarked that the shortlist was all-female and that the two winners show how a novella can do many different things: Astraea is at the low end of the word count at 22,000 words and takes place over just 36 hours; Aerth is towards the upper limit at 36,000 words and spans about 40 years.

Neil Griffiths

All the panellists dismissed the idea of a hierarchy with the full-length novel at the top. Griffiths said that the constraints of the novella, to need to discard and discard, make it stand out.

A further title from the 2024 shortlist, We Hexed the Moon by Mollyhall Seeley, will also be published by Weatherglass next year, and submissions are now open for the Weatherglass Novella Prize 2025.

Many thanks for my free ticket to a great event. Weatherglass has also kindly offered to send Cathy and me copies of the two novellas to review over the course of #NovNov. I’m looking forward to reading both winners!

Rathbones Folio Prize Fiction Shortlist: Sheila Heti and Elizabeth Strout

I’ve enjoyed engaging with this year’s Rathbones Folio Prize shortlists, reading the entire poetry shortlist and two each from the nonfiction and fiction lists. These two I accessed from the library. Both Sheila Heti and Elizabeth Strout featured in the 5×15 event I attended on Tuesday evening, so in the reviews below I’ll weave in some insights from that.

Pure Colour by Sheila Heti

Sheila Heti is a divisive author; I’m sure there are those who detest her indulgent autofiction, though I’ve loved it (How Should a Person Be? and especially Motherhood). But this is another thing entirely: Heti puts two fingers up to the whole notion of rounded characterization or coherent plot. This is the thinnest of fables, fascinating for its ideas and certainly resonant for me what with the themes of losing a parent and searching for purpose in life on an earth that seems doomed to destruction … but is it a novel?

Sheila Heti is a divisive author; I’m sure there are those who detest her indulgent autofiction, though I’ve loved it (How Should a Person Be? and especially Motherhood). But this is another thing entirely: Heti puts two fingers up to the whole notion of rounded characterization or coherent plot. This is the thinnest of fables, fascinating for its ideas and certainly resonant for me what with the themes of losing a parent and searching for purpose in life on an earth that seems doomed to destruction … but is it a novel?

My summary for Bookmarks magazine gives an idea of the ridiculous plot:

Heti imagines that the life we live now—for Mira, studying at the American Academy of American Critics, working in a lamp store, grieving her father, and falling in love with Annie—is just God’s first draft. In this creation myth of sorts, everyone is born a “bear” (lover), “bird” (achiever), or “fish” (follower). Mira has a mystical experience in which she and her dead father meet as souls in a leaf, where they converse about the nature of time and how art helps us face the inevitability of death. If everything that exists will soon be wiped out, what matters?

The three-creature classification is cute enough, but a copout because it means Heti doesn’t have to spend time developing Mira (a bird), Annie (a fish), or Mira’s father (a bear), except through surreal philosophical dialogues that may or may not take place whilst she is disembodied in a leaf. It’s also uncomfortable how Heti uses sexual language for Mira’s communion with her dead dad: “she knew that the universe had ejaculated his spirit into her”.

Heti explained that the book came to her in discrete chunks, from what felt like a more intuitive place than the others, which were more of an intellectual struggle, and that she drew on her own experience of grief over her father’s death, though she had been writing it for a year beforehand.

Indeed, she appears to be tapping into primordial stories, the stuff of Greek myth or Jewish kabbalah. She writes sometimes of “God” and sometimes of “the gods”: the former regretting this first draft of things and planning how to make things better for himself the second time around; the latter out to strip humans of what they care about: “our parents, our ambitions, our friendships, our beauty—different things from different people. They strip some people more and others less. They strip us of whatever they need to in order to see us more clearly.” Appropriately, then, we follow Mira all the way through to her end, when, stripped of everything but love, she rediscovers the two major human connections of her life.

Given Ali Smith’s love of the experimental, it’s no surprise that she as a judge shortlisted this. If you’re of a philosophical bent, don’t mind negligible/non-existent plot in your novels and aren’t turned off by literary pretension, you should be fine. If you are new to Heti or unsure about trying her, though, this is probably not the right place to start. See my Goodreads review for some sample quotes, good and bad.

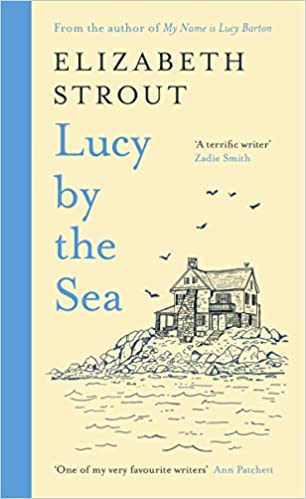

Lucy by the Sea by Elizabeth Strout

This was by far the best of the three Amgash books I’ve read. I think it must be the first time that Strout has set a book not in the past or at some undated near-contemporary moment but in the actual world with its current events, which inevitably means it gets political. I had my doubts about how successful she’d be with such hyper-realism, but this really worked.

As Covid hits, William whisks Lucy away from her New York City apartment to a house at the coast in Crosby, Maine. She’s an Everywoman recounting the fear and confusion of those early pandemic days, hearing of friends and relatives falling ill and knowing there’s nothing she can do about it. Isolation, mostly imposed on her but partially chosen – she finally gets a writing studio, the first ‘room of her own’ she’s ever had – gives her time to ponder the trauma of her childhood and what went wrong in her marriage to William. She worries for her two adult daughters but, for the first time, you get the sense that the strength and wisdom she’s earned through bitter experience will help her support them in making good choices.

As Covid hits, William whisks Lucy away from her New York City apartment to a house at the coast in Crosby, Maine. She’s an Everywoman recounting the fear and confusion of those early pandemic days, hearing of friends and relatives falling ill and knowing there’s nothing she can do about it. Isolation, mostly imposed on her but partially chosen – she finally gets a writing studio, the first ‘room of her own’ she’s ever had – gives her time to ponder the trauma of her childhood and what went wrong in her marriage to William. She worries for her two adult daughters but, for the first time, you get the sense that the strength and wisdom she’s earned through bitter experience will help her support them in making good choices.

Here in rural Maine, Lucy sees similar deprivation to what she grew up with in Illinois and also meets real people – nice, friendly people – who voted for Trump and refuse to be vaccinated. I loved how Strout shows us Lucy observing and then, through a short story, compassionately imagining herself into the situation of conservative cops and drug addicts. “Try to go outside your comfort level, because that’s where interesting things will happen on the page,” is her philosophy. This felt like real insight into a writer’s inspirations.

Another neat thing Strout does here, as she has done before, is to stitch her oeuvre together by including references to most of her other books. So she becomes friends with Bob Burgess, volunteers alongside Olive Kitteridge’s nursing home caregiver (and I expect their rental house is supposed to be the one Olive vacated), and meets the pastor’s daughter from Abide with Me. My only misgiving is that she recounts Bob Burgess’s whole story, replete with spoilers, such that I don’t feel I need to read The Burgess Boys.

Lucy has emotional intelligence (“You’re not stupid about the human heart,” Bob Burgess tells her) and real, hard-won insight into herself (“My childhood had been a lockdown”). Readers as well as writers have really taken this character to heart, admiring her seemingly effortless voice. Strout said she does not think of this as a ‘pandemic novel’ because she’s always most interested in character. She believes the most important thing is the sound of the sentences and that a writer has to determine the shape of the material from the inside. She was very keen to separate herself from Lucy, and in fact came across as rather terse. I had somehow expected her to have a higher voice, to be warmer and softer. (“Ah, you’re not Lucy, you’re Olive!” I thought to myself.)

Predictions

This year’s judges are Guy Gunaratne, Jackie Kay and Ali Smith. Last year’s winner was a white man, so I’m going to say in 2023 the prize should go to a woman of colour, and in fact I wouldn’t be surprised if all three category winners were women of colour. My own taste in the shortlists is, perhaps unsurprisingly, very white-lady-ish and non-experimental. But I think Amy Bloom and Elizabeth Strout’s books are too straightforward and Fiona Benson’s not edgy enough. So I’m expecting:

Fiction: Scary Monsters by Michelle de Kretser

Nonfiction: Constructing a Nervous System by Margo Jefferson

Poetry: Quiet by Victoria Adukwei Bulley (or Cane, Corn & Gully by Safiya Kamaria Kinshasa)

Overall winner: Constructing a Nervous System by Margo Jefferson (or Quiet by Victoria Adukwei Bulley)

This is my 1,200th blog post!

Book Serendipity, September to October 2021

I call it Book Serendipity when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something pretty bizarre in common. Because I have so many books on the go at once (usually 20–30), I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. I’ve realized that, of course, synchronicity is really the more apt word, but this branding has stuck. This used to be a quarterly feature, but to keep the lists from getting too unwieldy I’ve shifted to bimonthly.

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Young people studying An Inspector Calls in Somebody Loves You by Mona Arshi and Heartstoppers, Volume 4 by Alice Oseman.

- China Room (Sunjeev Sahota) was immediately followed by The China Factory (Mary Costello).

- A mention of acorn production being connected to the weather earlier in the year in Light Rains Sometimes Fall by Lev Parikian and Noah’s Compass by Anne Tyler.

- The experience of being lost and disoriented in Amsterdam features in Flesh & Blood by N. West Moss and Yearbook by Seth Rogen.

- Reading a book about ravens (A Shadow Above by Joe Shute) and one by a Raven (Fox & I by Catherine Raven) at the same time.

- Speaking of ravens, they’re also mentioned in The Elements by Kat Lister, and the Edgar Allan Poe poem “The Raven” was referred to and/or quoted in both of those books plus 100 Poets by John Carey.

- A trip to Mexico as a way to come to terms with the death of a loved one in This Party’s Dead by Erica Buist (read back in February–March) and The Elements by Kat Lister.

- Reading from two Carcanet Press releases that are Covid-19 diaries and have plague masks on the cover at the same time: Year of Plagues by Fred D’Aguiar and 100 Days by Gabriel Josipovici. (Reviews of both coming up soon.)

- Descriptions of whaling and whale processing and a summary of the Jonah and the Whale story in Fathoms by Rebecca Giggs and The Woodcock by Richard Smyth.

An Irish short story featuring an elderly mother with dementia AND a particular mention of her slippers in The China Factory by Mary Costello and Blank Pages and Other Stories by Bernard MacLaverty.

An Irish short story featuring an elderly mother with dementia AND a particular mention of her slippers in The China Factory by Mary Costello and Blank Pages and Other Stories by Bernard MacLaverty.

- After having read two whole nature memoirs set in England’s New Forest (Goshawk Summer by James Aldred and The Circling Sky by Neil Ansell), I encountered it again in one chapter of A Shadow Above by Joe Shute.

- Cranford is mentioned in Corduroy by Adrian Bell and Cut Out by Michèle Roberts.

- Kenneth Grahame’s life story and The Wind in the Willows are discussed in On Gallows Down by Nicola Chester and The Elements by Kat Lister.

- Reading two books by a Jenn at the same time: Ghosted by Jenn Ashworth and The Other Mothers by Jenn Berney.

- A metaphor of nature giving a V sign (that’s equivalent to the middle finger for you American readers) in On Gallows Down by Nicola Chester and Light Rains Sometimes Fall by Lev Parikian.

- Quince preserves are mentioned in The Book of Difficult Fruit by Kate Lebo and Light Rains Sometimes Fall by Lev Parikian.

- There’s a gooseberry pie in Talking to the Dead by Helen Dunmore and The Book of Difficult Fruit by Kate Lebo.

- The ominous taste of herbicide in the throat post-spraying shows up in On Gallows Down by Nicola Chester and Damnation Spring by Ash Davidson.

- People’s rude questioning about gay dads and surrogacy turns up in The Echo Chamber by John Boyne and the DAD anthology from Music.Football.Fatherhood.

- A young woman dresses in unattractive secondhand clothes in The Echo Chamber by John Boyne and Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney.

- A mention of the bounty placed on crop-eating birds in medieval England in Orchard by Benedict Macdonald and Nicholas Gates and A Shadow Above by Joe Shute.

- Hedgerows being decimated, and an account of how mistletoe is spread, in On Gallows Down by Nicola Chester and Orchard by Benedict Macdonald and Nicholas Gates.

Ukrainian secondary characters in Ghosted by Jenn Ashworth and The Echo Chamber by John Boyne; minor characters named Aidan in the Boyne and Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney.

Ukrainian secondary characters in Ghosted by Jenn Ashworth and The Echo Chamber by John Boyne; minor characters named Aidan in the Boyne and Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney.

- Listening to a dual-language presentation and observing that the people who know the original language laugh before the rest of the audience in The Book of Difficult Fruit by Kate Lebo and Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney.

- A character imagines his heart being taken out of his chest in Tender Is the Flesh by Agustina Bazterrica and The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki.

- A younger sister named Nina in Talking to the Dead by Helen Dunmore and Sex Cult Nun by Faith Jones.

- Adulatory words about George H.W. Bush in The Echo Chamber by John Boyne and Thinking Again by Jan Morris.

- Reading three novels by Australian women at the same time (and it’s rare for me to read even one – availability in the UK can be an issue): Sorrow and Bliss by Meg Mason, The Performance by Claire Thomas, and The Weekend by Charlotte Wood.

- There’s a couple who met as family friends as teenagers and are still (on again, off again) together in Sorrow and Bliss by Meg Mason and Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney.

- The Performance by Claire Thomas is set during a performance of the Samuel Beckett play Happy Days, which is mentioned in 100 Days by Gabriel Josipovici.

Human ashes are dumped and a funerary urn refilled with dirt in Tender Is the Flesh by Agustina Bazterrica and Public Library and Other Stories by Ali Smith.

Human ashes are dumped and a funerary urn refilled with dirt in Tender Is the Flesh by Agustina Bazterrica and Public Library and Other Stories by Ali Smith.

- Nicholas Royle (whose White Spines I was also reading at the time) turns up on a Zoom session in 100 Days by Gabriel Josipovici.

- Richard Brautigan is mentioned in both The Mystery of Henri Pick by David Foenkinos and White Spines by Nicholas Royle.

- The Wizard of Oz and The Railway Children are part of the plot in The Book Smugglers (Pages & Co., #4) by Anna James and mentioned in Public Library and Other Stories by Ali Smith.

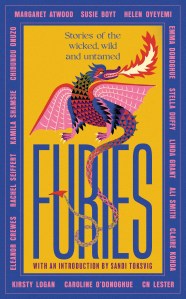

As with any anthology, some pieces stand out more than others. Caroline O’Donoghue, Helen Oyeyemi and Kamila Shamsie’s contributions were unlikely to convert me into a fan. Margaret Atwood is ever sly and accessible, with “Siren” opening with the line “Today’s Liminal Beings Knitting Circle will now be called to order.” I was surprised to get on really well with Kirsty Logan’s “Wench,” about girls ostracized by their religious community because of their desire for each other – I’ll have to read Now She Is Witch, as it’s set in the same fictional world – and Chibundu Onuzo’s “Warrior,” about Deborah, an Israelite leader in the book of Judges. And while I doubt I need to read a whole novel by Rachel Seiffert, I did enjoy “Fury,” about a group of Polish women who fended off Nazi invaders.

As with any anthology, some pieces stand out more than others. Caroline O’Donoghue, Helen Oyeyemi and Kamila Shamsie’s contributions were unlikely to convert me into a fan. Margaret Atwood is ever sly and accessible, with “Siren” opening with the line “Today’s Liminal Beings Knitting Circle will now be called to order.” I was surprised to get on really well with Kirsty Logan’s “Wench,” about girls ostracized by their religious community because of their desire for each other – I’ll have to read Now She Is Witch, as it’s set in the same fictional world – and Chibundu Onuzo’s “Warrior,” about Deborah, an Israelite leader in the book of Judges. And while I doubt I need to read a whole novel by Rachel Seiffert, I did enjoy “Fury,” about a group of Polish women who fended off Nazi invaders. Susanna Jones’s

Susanna Jones’s  The title characters are a brother and sister in their late twenties who share a flat and a tendency to sabotage romantic relationships. Both are matter-of-factly queer and biracial (Māori/Russian). The novel flips back and forth between their present-tense first-person narration with each short chapter. It takes quite a while to pick up on who is who in the extended Vladisavljevic clan and their New Zealand university milieu (their father is a science professor and Greta an English department PhD and tutor), so I was glad of the character list at the start.

The title characters are a brother and sister in their late twenties who share a flat and a tendency to sabotage romantic relationships. Both are matter-of-factly queer and biracial (Māori/Russian). The novel flips back and forth between their present-tense first-person narration with each short chapter. It takes quite a while to pick up on who is who in the extended Vladisavljevic clan and their New Zealand university milieu (their father is a science professor and Greta an English department PhD and tutor), so I was glad of the character list at the start. The Lost Love Songs of Boysie Singh by Ingrid Persaud – I thought Persaud’s debut novel,

The Lost Love Songs of Boysie Singh by Ingrid Persaud – I thought Persaud’s debut novel,

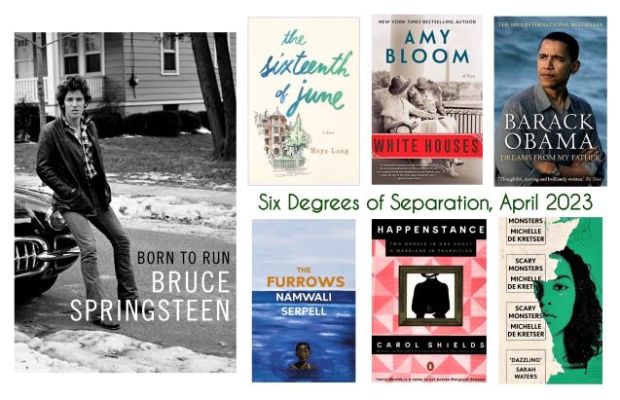

#1 Springsteen is one of my musical blind spots – I maybe know two songs by him? – but my husband has been working up a cover of his “Streets of Philadelphia” to perform at the next open mic night at our local arts venue. A great Philadelphia-set novel I’ve read twice is

#1 Springsteen is one of my musical blind spots – I maybe know two songs by him? – but my husband has been working up a cover of his “Streets of Philadelphia” to perform at the next open mic night at our local arts venue. A great Philadelphia-set novel I’ve read twice is  #2 The 16th of June is, as James Joyce fans out there will know, “Bloomsday,” so I’ll move on to the only novel I’ve read so far by Amy Bloom (and one I felt ambivalent about, though I love her

#2 The 16th of June is, as James Joyce fans out there will know, “Bloomsday,” so I’ll move on to the only novel I’ve read so far by Amy Bloom (and one I felt ambivalent about, though I love her  #3 A recent and much-missed occupant of the White House: Barack Obama, whose Dreams from My Father didn’t quite stand up to

#3 A recent and much-missed occupant of the White House: Barack Obama, whose Dreams from My Father didn’t quite stand up to  #4 Similar to the Oprah effect, Obama publicly mentioning that he’s read and enjoyed a book is enough to make it a bestseller. On his list of favourite books of 2022 was The Furrows by Namwali Serpell, which I currently have on the go as a buddy read with

#4 Similar to the Oprah effect, Obama publicly mentioning that he’s read and enjoyed a book is enough to make it a bestseller. On his list of favourite books of 2022 was The Furrows by Namwali Serpell, which I currently have on the go as a buddy read with  #5 The Furrows is longlisted for the inaugural Carol Shields Prize for Fiction. In 2020 I did buddy reads of six

#5 The Furrows is longlisted for the inaugural Carol Shields Prize for Fiction. In 2020 I did buddy reads of six  #6 My Happenstance volume gives the wife’s story first and then once you’ve read to halfway you flip it over to read the husband’s story. The only other novel I know of that does that (

#6 My Happenstance volume gives the wife’s story first and then once you’ve read to halfway you flip it over to read the husband’s story. The only other novel I know of that does that ( Rather like a linked short story collection, it presents vignettes from the lives of two female artists – Mari, a writer and illustrator; and Jonna, a visual artist and filmmaker – who are long-term, devoted partners. Of course, this cannot be read as other than autobiographical of Jansson and her partner of 45 years, Tuulikki Pietilä. There are other specific details drawn from life, too.

Rather like a linked short story collection, it presents vignettes from the lives of two female artists – Mari, a writer and illustrator; and Jonna, a visual artist and filmmaker – who are long-term, devoted partners. Of course, this cannot be read as other than autobiographical of Jansson and her partner of 45 years, Tuulikki Pietilä. There are other specific details drawn from life, too.

This potted biography of the author best known for the Moomins showcases the development of her artistic style and literary themes. Born at the start of World War I into a family of artists (her father a sculptor, her mother a graphic designer, her brother Lars a collaborator on her comics), Jansson wanted to paint but had limited opportunities as a woman. The book contains a wealth of illustrations – over 100, so nearly one per page – including photographs and high-quality reproductions, many in color and some in black and white, of Jansson’s comics, paintings and book covers. Gravett also probes the autobiographical influences on Jansson’s work, which are particularly clear in her 15 books for adults. A sensitive portrayal of Finland’s most widely translated author, this is itself a work of art.

This potted biography of the author best known for the Moomins showcases the development of her artistic style and literary themes. Born at the start of World War I into a family of artists (her father a sculptor, her mother a graphic designer, her brother Lars a collaborator on her comics), Jansson wanted to paint but had limited opportunities as a woman. The book contains a wealth of illustrations – over 100, so nearly one per page – including photographs and high-quality reproductions, many in color and some in black and white, of Jansson’s comics, paintings and book covers. Gravett also probes the autobiographical influences on Jansson’s work, which are particularly clear in her 15 books for adults. A sensitive portrayal of Finland’s most widely translated author, this is itself a work of art.