Book Serendipity, September to October 2021

I call it Book Serendipity when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something pretty bizarre in common. Because I have so many books on the go at once (usually 20–30), I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. I’ve realized that, of course, synchronicity is really the more apt word, but this branding has stuck. This used to be a quarterly feature, but to keep the lists from getting too unwieldy I’ve shifted to bimonthly.

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Young people studying An Inspector Calls in Somebody Loves You by Mona Arshi and Heartstoppers, Volume 4 by Alice Oseman.

- China Room (Sunjeev Sahota) was immediately followed by The China Factory (Mary Costello).

- A mention of acorn production being connected to the weather earlier in the year in Light Rains Sometimes Fall by Lev Parikian and Noah’s Compass by Anne Tyler.

- The experience of being lost and disoriented in Amsterdam features in Flesh & Blood by N. West Moss and Yearbook by Seth Rogen.

- Reading a book about ravens (A Shadow Above by Joe Shute) and one by a Raven (Fox & I by Catherine Raven) at the same time.

- Speaking of ravens, they’re also mentioned in The Elements by Kat Lister, and the Edgar Allan Poe poem “The Raven” was referred to and/or quoted in both of those books plus 100 Poets by John Carey.

- A trip to Mexico as a way to come to terms with the death of a loved one in This Party’s Dead by Erica Buist (read back in February–March) and The Elements by Kat Lister.

- Reading from two Carcanet Press releases that are Covid-19 diaries and have plague masks on the cover at the same time: Year of Plagues by Fred D’Aguiar and 100 Days by Gabriel Josipovici. (Reviews of both coming up soon.)

- Descriptions of whaling and whale processing and a summary of the Jonah and the Whale story in Fathoms by Rebecca Giggs and The Woodcock by Richard Smyth.

An Irish short story featuring an elderly mother with dementia AND a particular mention of her slippers in The China Factory by Mary Costello and Blank Pages and Other Stories by Bernard MacLaverty.

An Irish short story featuring an elderly mother with dementia AND a particular mention of her slippers in The China Factory by Mary Costello and Blank Pages and Other Stories by Bernard MacLaverty.

- After having read two whole nature memoirs set in England’s New Forest (Goshawk Summer by James Aldred and The Circling Sky by Neil Ansell), I encountered it again in one chapter of A Shadow Above by Joe Shute.

- Cranford is mentioned in Corduroy by Adrian Bell and Cut Out by Michèle Roberts.

- Kenneth Grahame’s life story and The Wind in the Willows are discussed in On Gallows Down by Nicola Chester and The Elements by Kat Lister.

- Reading two books by a Jenn at the same time: Ghosted by Jenn Ashworth and The Other Mothers by Jenn Berney.

- A metaphor of nature giving a V sign (that’s equivalent to the middle finger for you American readers) in On Gallows Down by Nicola Chester and Light Rains Sometimes Fall by Lev Parikian.

- Quince preserves are mentioned in The Book of Difficult Fruit by Kate Lebo and Light Rains Sometimes Fall by Lev Parikian.

- There’s a gooseberry pie in Talking to the Dead by Helen Dunmore and The Book of Difficult Fruit by Kate Lebo.

- The ominous taste of herbicide in the throat post-spraying shows up in On Gallows Down by Nicola Chester and Damnation Spring by Ash Davidson.

- People’s rude questioning about gay dads and surrogacy turns up in The Echo Chamber by John Boyne and the DAD anthology from Music.Football.Fatherhood.

- A young woman dresses in unattractive secondhand clothes in The Echo Chamber by John Boyne and Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney.

- A mention of the bounty placed on crop-eating birds in medieval England in Orchard by Benedict Macdonald and Nicholas Gates and A Shadow Above by Joe Shute.

- Hedgerows being decimated, and an account of how mistletoe is spread, in On Gallows Down by Nicola Chester and Orchard by Benedict Macdonald and Nicholas Gates.

Ukrainian secondary characters in Ghosted by Jenn Ashworth and The Echo Chamber by John Boyne; minor characters named Aidan in the Boyne and Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney.

Ukrainian secondary characters in Ghosted by Jenn Ashworth and The Echo Chamber by John Boyne; minor characters named Aidan in the Boyne and Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney.

- Listening to a dual-language presentation and observing that the people who know the original language laugh before the rest of the audience in The Book of Difficult Fruit by Kate Lebo and Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney.

- A character imagines his heart being taken out of his chest in Tender Is the Flesh by Agustina Bazterrica and The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki.

- A younger sister named Nina in Talking to the Dead by Helen Dunmore and Sex Cult Nun by Faith Jones.

- Adulatory words about George H.W. Bush in The Echo Chamber by John Boyne and Thinking Again by Jan Morris.

- Reading three novels by Australian women at the same time (and it’s rare for me to read even one – availability in the UK can be an issue): Sorrow and Bliss by Meg Mason, The Performance by Claire Thomas, and The Weekend by Charlotte Wood.

- There’s a couple who met as family friends as teenagers and are still (on again, off again) together in Sorrow and Bliss by Meg Mason and Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney.

- The Performance by Claire Thomas is set during a performance of the Samuel Beckett play Happy Days, which is mentioned in 100 Days by Gabriel Josipovici.

Human ashes are dumped and a funerary urn refilled with dirt in Tender Is the Flesh by Agustina Bazterrica and Public Library and Other Stories by Ali Smith.

Human ashes are dumped and a funerary urn refilled with dirt in Tender Is the Flesh by Agustina Bazterrica and Public Library and Other Stories by Ali Smith.

- Nicholas Royle (whose White Spines I was also reading at the time) turns up on a Zoom session in 100 Days by Gabriel Josipovici.

- Richard Brautigan is mentioned in both The Mystery of Henri Pick by David Foenkinos and White Spines by Nicholas Royle.

- The Wizard of Oz and The Railway Children are part of the plot in The Book Smugglers (Pages & Co., #4) by Anna James and mentioned in Public Library and Other Stories by Ali Smith.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Reading Ireland Month 2020: Nuala O’Faolain and More

It feels like the whole world has changed in the past week, doesn’t it? I hope you all are keeping well and turning to books for comfort and escape. Reading Ireland Month is run each March by Cathy of 746 Books. I’m wishing you a happy (if subdued) St. Patrick’s Day with this post on the Irish books I’ve been perusing recently. Even before this coronavirus situation heated up, I’d been struggling with my focus, so only one of these was a proper read, while the rest ended up being skims. In the meantime, I’m trying out a new blog design and have been working to create more intuitive menu headings and helpful intro pages.

Are You Somebody? The Accidental Memoir of a Dublin Woman by Nuala O’Faolain (1996)

Before writing this landmark memoir, O’Faolain was a TV documentary producer and Irish Times columnist. Her upbringing in poverty is reminiscent of Frank McCourt’s: one of nine children, she had a violent father and an alcoholic mother who cheated on each other and never seemed to achieve happiness. Educated at a convent school and at university in Dublin (until she dropped out), she was a literary-minded romantic who bounced between relationships and couldn’t decide whether marriage or a career should be her highest aim. Though desperate not to become her mother – a bitter, harried woman who’d wanted to be a book reviewer – she didn’t want to miss out on a chance for love either.

Before writing this landmark memoir, O’Faolain was a TV documentary producer and Irish Times columnist. Her upbringing in poverty is reminiscent of Frank McCourt’s: one of nine children, she had a violent father and an alcoholic mother who cheated on each other and never seemed to achieve happiness. Educated at a convent school and at university in Dublin (until she dropped out), she was a literary-minded romantic who bounced between relationships and couldn’t decide whether marriage or a career should be her highest aim. Though desperate not to become her mother – a bitter, harried woman who’d wanted to be a book reviewer – she didn’t want to miss out on a chance for love either.

O’Faolain feels she was born slightly too early to benefit from the women’s movement. “I could see sexism in operation everywhere in society; once your consciousness goes ping you can never again stop seeing that. But I was quite unaware of how consistently I put the responsibility for my personal happiness off onto men.” Chapter 16 is a standout, though with no explanation (all her other lovers were men) it launches into an account of her 15 years living with Nell McCafferty, “by far the most life-giving relationship of my life.”

Although this is in many respects an ordinary story, the geniality and honesty of the writing account for its success. It was an instant bestseller in Ireland, spending 20 weeks at number one, and made the author a household name. I especially loved her encounters with literary figures. For instance, on a year’s scholarship at Hull she didn’t quite meet Philip Larkin, who’d been tasked with looking after her, but years later had a bizarre dinner with him and his mother, both rather deaf; and David Lodge was a friend. The boarding school section reminded me of The Country Girls. Two bookish memoirs I’d recommend as readalikes are Ordinary Dogs by Eileen Battersby and Leave Me Alone, I’m Reading by Maureen Corrigan.

Skims (all:  )

)

Actress by Anne Enright (2020)

The Green Road is among my most memorable reads of the past five years, so I was eagerly awaiting Enright’s new novel, which is on the Women’s Prize longlist. I read the first 30 pages and found I wasn’t warming to the voice or main characters. Norah is a novelist who, prompted by an interviewer, realizes the story she most needs to tell is her mother’s. Katherine O’Dell was “a great fake,” an actress who came to epitomize Irishness even though she was actually English. Her slow-burning backstory is punctuated by trauma and mental illness. “She was a great piece of anguish, madness and sorrow,” Norah concludes. I could easily see this making the Women’s Prize shortlist and earning a Booker nomination as well. It’s the sort of book I’ll need to come back to some years down the line to fully appreciate.

The Green Road is among my most memorable reads of the past five years, so I was eagerly awaiting Enright’s new novel, which is on the Women’s Prize longlist. I read the first 30 pages and found I wasn’t warming to the voice or main characters. Norah is a novelist who, prompted by an interviewer, realizes the story she most needs to tell is her mother’s. Katherine O’Dell was “a great fake,” an actress who came to epitomize Irishness even though she was actually English. Her slow-burning backstory is punctuated by trauma and mental illness. “She was a great piece of anguish, madness and sorrow,” Norah concludes. I could easily see this making the Women’s Prize shortlist and earning a Booker nomination as well. It’s the sort of book I’ll need to come back to some years down the line to fully appreciate.

Cal by Bernard MacLaverty (1983)

As Catholics, Cal McCluskey and his father are a rarity in their community and fear attacks on their home. Resistant to join his father in working at the local abattoir, Cal spends his days doing odd jobs and lurking around the public library – he has a crush on a married librarian named Marcella. Aimless and impressionable, he’s easily talked into acting as a driver for Crilly and Skeffington, the kind of associates who have gotten him branded as “Fenian scum.” The novella reflects on the futility of cycles of violence (“If you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem,” Crilly says, to which Cal replies, “But it all seems so pointless”), but is definitely a period piece. Cal is not the most sympathetic of protagonists. I didn’t enjoy this as much as the two other books I’ve read by MacLaverty.

As Catholics, Cal McCluskey and his father are a rarity in their community and fear attacks on their home. Resistant to join his father in working at the local abattoir, Cal spends his days doing odd jobs and lurking around the public library – he has a crush on a married librarian named Marcella. Aimless and impressionable, he’s easily talked into acting as a driver for Crilly and Skeffington, the kind of associates who have gotten him branded as “Fenian scum.” The novella reflects on the futility of cycles of violence (“If you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem,” Crilly says, to which Cal replies, “But it all seems so pointless”), but is definitely a period piece. Cal is not the most sympathetic of protagonists. I didn’t enjoy this as much as the two other books I’ve read by MacLaverty.

Full Tilt: Ireland to India with a Bicycle by Dervla Murphy (1965)

Murphy and her bike “Roz” set out on an epic Fermor-like journey in the first six months of 1963. She covered 60 to 100 miles a day, facing sunburn, punctured tires and broken ribs. She was relieved she brought a gun: it came in handy for fending off wolves, deterring a would-be rapist, and preventing bike thieves. For some reason travel books are slow, painstaking reads for me. I never got into the flow of this one, and was troubled by snap judgments about groups of people – “I know instinctively the temper of a place, after being five minutes with the inhabitants. … the Afghans are, on balance, much dirtier in clothes, personal habits and dwellings than either the Turks or Persians.” Murphy does have a witty turn of phrase, though, e.g. “I suppose I’ll get used to it but at the moment I wouldn’t actually say that camel’s milk is my favourite beverage.”

Murphy and her bike “Roz” set out on an epic Fermor-like journey in the first six months of 1963. She covered 60 to 100 miles a day, facing sunburn, punctured tires and broken ribs. She was relieved she brought a gun: it came in handy for fending off wolves, deterring a would-be rapist, and preventing bike thieves. For some reason travel books are slow, painstaking reads for me. I never got into the flow of this one, and was troubled by snap judgments about groups of people – “I know instinctively the temper of a place, after being five minutes with the inhabitants. … the Afghans are, on balance, much dirtier in clothes, personal habits and dwellings than either the Turks or Persians.” Murphy does have a witty turn of phrase, though, e.g. “I suppose I’ll get used to it but at the moment I wouldn’t actually say that camel’s milk is my favourite beverage.”

My Father’s Wake: How the Irish Teach Us to Live, Love and Die by Kevin Toolis (2017)

Toolis is a journalist and filmmaker from Dookinella, on an island off the coast of County Mayo. His father Sonny’s pancreatic cancer prompted him to return to the ancestral village and reflect on his own encounters with death. As a young man he had tuberculosis and stayed on a male chest ward with longtime smokers; despite a bone marrow donation, his older brother Bernard died from leukemia.

Toolis is a journalist and filmmaker from Dookinella, on an island off the coast of County Mayo. His father Sonny’s pancreatic cancer prompted him to return to the ancestral village and reflect on his own encounters with death. As a young man he had tuberculosis and stayed on a male chest ward with longtime smokers; despite a bone marrow donation, his older brother Bernard died from leukemia.

As a reporter during the Troubles and in Malawi and Gaza, Toolis often witnessed death, but at home in rural Ireland he saw a model for how it should be: accepted, and faced with the support of a whole community. People made a point of coming to see Sonny as he was dying. Keeping the body in the home and holding a wake are precious opportunities to be with the dead. Death is what’s coming for us all, so why not make its acquaintance? Toolis argues.

I’ve read so much around the topic that books like this don’t stand out anymore, and while I preferred the general talk of death to the family memoir bits, it also made very familiar points. At any rate, his description of his mother’s death is just how I want to go: “She quietly died of a heart attack with a cup of tea and a biscuit on a sunny May morning.”

What have you been picking up for Reading Ireland Month?

Thoughts on the Wellcome Book Prize Longlist

The 2018 Wellcome Book Prize longlist is here! From the prize’s website, you can click on any of these 12 books’ covers, titles or authors to get more information about them.

Some initial thoughts:

I correctly predicted three of the entries (or 25%) in yesterday’s post: In Pursuit of Memory by Joseph Jebelli, With the End in Mind by Kathryn Mannix, and I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O’Farrell. I’m pretty shocked to not see Fragile Lives or Admissions on the list.

Of the remainder, I’ve already read one (Midwinter Break) and DNFed another (Stay with Me). Midwinter Break didn’t immediately suggest itself to me for this prize because its themes of ageing and alcoholism are the background to a story about the disintegration of a long marriage. Nonetheless, it’s a lovely book that hasn’t gotten as much attention as it deserves – it was on my runners-up list from last year – so I’m delighted to see it nominated. Stay with Me was also on the Women’s Prize shortlist; it appears here for its infertility theme, but I wouldn’t attempt it again unless it made the Wellcome shortlist.

As to the rest:

- I’m annoyed with myself for not remembering The Butchering Art, which I have on my Kindle. Sometimes I assume that books I’ve gotten from NetGalley are USA-only and don’t check for a UK publisher. I plan to read this and With the End in Mind (also on my Kindle) soon.

- I already knew about and was interested in Mayhem and The White Book.

- Of the ones I didn’t know about, Plot 29 appeals to me the most. I’m off to get it from the library this very afternoon, in fact. Its health theme seems quite subtle: it’s about a devoted gardener ‘digging’ into his past in an abusive family and foster care. The Guardian review describes it thus: “Like Helen Macdonald’s H Is for Hawk, this is a profoundly moving account of mental trauma told through the author’s encounters with nature. Jenkins sees his garden as a place where a person can try to escape from, and atone for, the darkness of human existence.” This is the great thing about prize lists: they can introduce you to fascinating books you might never have heard of otherwise. Even if it’s just one book that takes your fancy, who knows? It might end up being a favorite.

- While I’m not immediately drawn to the books on the history of vaccines, the evolution of human behavior, and transhumanism, I will certainly be glad to read them if they make the shortlist.

Some statistics on this year’s longlist, courtesy of the press release I was sent by e-mail:

- Three novels, three memoirs, and six nonfiction titles

- Five debut authors

- Three titles from independent publishers (Canongate and Granta/Portobello Books)

- The authors are from the UK, Ireland, USA, Nigeria, Canada, and – making their first appearance – Sweden (Sigrid Rausing) and South Korea (Han Kang)

Chair of judges Edmund de Waal writes: “The Wellcome Book Prize is unique in its reach across genres, and so the range of books that we have considered has been exhilarating in its extent and ambition. This is a remarkable time for readers, with a great flourishing of writing on ideas around science, medicine and health, lives and deaths, histories and futures. After passionate discussions we have arrived at our longlist for the Wellcome Book Prize 2018 and are proud to be part of this process of bringing to a wider public these 12 tremendous books that have moved, intrigued and inspired us. All of them bring something new to our understanding of what it is to be human.”

The shortlist is announced on Tuesday, March 20th, and the winner will be revealed on Monday, April 30th.

The 11 stories in Erskine’s second collection do just what short fiction needs to: dramatize an encounter, or moment, that changes life forever. Her characters are ordinary, moving through the dead-end work and family friction that constitute daily existence, until something happens, or rises up in the memory, that disrupts the tedium.

The 11 stories in Erskine’s second collection do just what short fiction needs to: dramatize an encounter, or moment, that changes life forever. Her characters are ordinary, moving through the dead-end work and family friction that constitute daily existence, until something happens, or rises up in the memory, that disrupts the tedium.

In form this is similar to O’Farrell’s

In form this is similar to O’Farrell’s  These autobiographical essays were compiled by Quinn based on interviews he conducted with nine women writers for an RTE Radio series in 1985. I’d read bits of Dervla Murphy’s and Edna O’Brien’s work before, but the other authors were new to me (Maeve Binchy, Clare Boylan, Polly Devlin, Jennifer Johnston, Molly Keane, Mary Lavin and Joan Lingard). The focus is on childhood: what their family was like, what drove these women to write, and what fragments of real life have made it into their books.

These autobiographical essays were compiled by Quinn based on interviews he conducted with nine women writers for an RTE Radio series in 1985. I’d read bits of Dervla Murphy’s and Edna O’Brien’s work before, but the other authors were new to me (Maeve Binchy, Clare Boylan, Polly Devlin, Jennifer Johnston, Molly Keane, Mary Lavin and Joan Lingard). The focus is on childhood: what their family was like, what drove these women to write, and what fragments of real life have made it into their books.

I didn’t realize when I started it that this was Tóibín’s debut collection; so confident is his verse that I assumed he’s been publishing poetry for decades. He’s one of those polymaths who’s written in many genres – contemporary fiction, literary criticism, travel memoir, historical fiction – and impresses in all. I’ve been finding his recent Folio Prize winner, The Magician, a little too dry and biography-by-rote for someone with no particular interest in Thomas Mann (I’ve only ever read Death in Venice), so I will likely just skim it before returning it to the library, but I can highly recommend his poems as an alternative.

I didn’t realize when I started it that this was Tóibín’s debut collection; so confident is his verse that I assumed he’s been publishing poetry for decades. He’s one of those polymaths who’s written in many genres – contemporary fiction, literary criticism, travel memoir, historical fiction – and impresses in all. I’ve been finding his recent Folio Prize winner, The Magician, a little too dry and biography-by-rote for someone with no particular interest in Thomas Mann (I’ve only ever read Death in Venice), so I will likely just skim it before returning it to the library, but I can highly recommend his poems as an alternative.

My first R.I.P. selection and one I can heartily recommend – even if you’re normally wary of dystopias, horror and science fiction. Butler makes these genres accessible by peopling her plots with relatable protagonists and carefully accounting for their bizarre predicaments without wasting time on extraneous world-building. The way in which she explores very human issues alongside the existence of alien beings reminds me of Mary Doria Russell’s

My first R.I.P. selection and one I can heartily recommend – even if you’re normally wary of dystopias, horror and science fiction. Butler makes these genres accessible by peopling her plots with relatable protagonists and carefully accounting for their bizarre predicaments without wasting time on extraneous world-building. The way in which she explores very human issues alongside the existence of alien beings reminds me of Mary Doria Russell’s

I knew from

I knew from  The musical equivalent of Lot might be a mixtape played on a boombox or blasted from an open-top Corvette while touring the streets of Houston, Texas. Most of this Dylan Thomas Prize-winning linked collection follows Nic, a mixed-race Black/Latino boy who works in the family restaurant. As his family situation realigns – his father leaves, his older brother Javi enlists, his sister Jan has a baby – he’s trying to come to terms with his homosexuality and wondering if this gentrifying city suits him anymore. But he knows he’ll take himself wherever he goes, and as the book closes with “Elgin” (the most similar in mood and setup to Washington’s debut novel,

The musical equivalent of Lot might be a mixtape played on a boombox or blasted from an open-top Corvette while touring the streets of Houston, Texas. Most of this Dylan Thomas Prize-winning linked collection follows Nic, a mixed-race Black/Latino boy who works in the family restaurant. As his family situation realigns – his father leaves, his older brother Javi enlists, his sister Jan has a baby – he’s trying to come to terms with his homosexuality and wondering if this gentrifying city suits him anymore. But he knows he’ll take himself wherever he goes, and as the book closes with “Elgin” (the most similar in mood and setup to Washington’s debut novel,

Midwinter Break by Bernard MacLaverty: In MacLaverty’s quietly beautiful fifth novel, a retired couple faces up to past trauma and present incompatibility during a short vacation in Amsterdam. My overall response was one of admiration for what this couple has survived and sympathy for their current situation – with hope that they’ll make it through this, too. (Reviewed for

Midwinter Break by Bernard MacLaverty: In MacLaverty’s quietly beautiful fifth novel, a retired couple faces up to past trauma and present incompatibility during a short vacation in Amsterdam. My overall response was one of admiration for what this couple has survived and sympathy for their current situation – with hope that they’ll make it through this, too. (Reviewed for

Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders: The residents of Georgetown cemetery limbo don’t know they’re dead – or at least won’t accept it. An entertaining and truly original treatment of life’s transience; I know it’s on every other best-of-year list out there, but it really is a must-read.

Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders: The residents of Georgetown cemetery limbo don’t know they’re dead – or at least won’t accept it. An entertaining and truly original treatment of life’s transience; I know it’s on every other best-of-year list out there, but it really is a must-read.

A Life of My Own by Claire Tomalin: Tomalin is best known as a biographer of literary figures including Mary Wollstonecraft, Samuel Pepys and Charles Dickens, but her memoir is especially revealing about the social and cultural history of the earlier decades her life covers. A dignified but slightly aloof book – well worth reading for anyone interested in spending time in London’s world of letters in the second half of the twentieth century.

A Life of My Own by Claire Tomalin: Tomalin is best known as a biographer of literary figures including Mary Wollstonecraft, Samuel Pepys and Charles Dickens, but her memoir is especially revealing about the social and cultural history of the earlier decades her life covers. A dignified but slightly aloof book – well worth reading for anyone interested in spending time in London’s world of letters in the second half of the twentieth century. Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward: The story of a mixed-race family haunted – both literally and figuratively – by the effects of racism, drug abuse and incarceration in Bois Sauvage, a fictional Mississippi town. Beautiful language; perfect for fans of Toni Morrison and Cynthia Bond.

Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward: The story of a mixed-race family haunted – both literally and figuratively – by the effects of racism, drug abuse and incarceration in Bois Sauvage, a fictional Mississippi town. Beautiful language; perfect for fans of Toni Morrison and Cynthia Bond. What It Means when a Man Falls from the Sky by Lesley Nneka Arimah (Reviewed for

What It Means when a Man Falls from the Sky by Lesley Nneka Arimah (Reviewed for  The Education of a Coroner by John Bateson: The coroner’s career is eventful no matter what, but Marin County, California has its fair share of special interest, what with Golden Gate Bridge suicides, misdeeds at San Quentin Prison, and various cases involving celebrities (e.g. Harvey Milk, Jerry Garcia and Tupac) in addition to your everyday sordid homicides. Ken Holmes was a death investigator and coroner in Marin County for 36 years; Bateson successfully recreates Holmes’ cases with plenty of (sometimes gory) details.

The Education of a Coroner by John Bateson: The coroner’s career is eventful no matter what, but Marin County, California has its fair share of special interest, what with Golden Gate Bridge suicides, misdeeds at San Quentin Prison, and various cases involving celebrities (e.g. Harvey Milk, Jerry Garcia and Tupac) in addition to your everyday sordid homicides. Ken Holmes was a death investigator and coroner in Marin County for 36 years; Bateson successfully recreates Holmes’ cases with plenty of (sometimes gory) details. Cork Dork by Bianca Bosker: Tasting notes: gleeful, ebullient, learned, self-deprecating; suggested pairings: Sweetbitter by Stephanie Danler; Top Chef, The Great British Bake Off. A delightful blend of science, memoir and encounters with people who are deadly serious about wine.

Cork Dork by Bianca Bosker: Tasting notes: gleeful, ebullient, learned, self-deprecating; suggested pairings: Sweetbitter by Stephanie Danler; Top Chef, The Great British Bake Off. A delightful blend of science, memoir and encounters with people who are deadly serious about wine. A Paris All Your Own: Bestselling Women Writers on the City of Light, edited by Eleanor Brown: A highly enjoyable set of 18 autobiographical essays that celebrate what’s wonderful about the place but also acknowledge disillusionment; highlights are from Maggie Shipstead, Paula McLain, Therese Anne Fowler, Jennifer Coburn, Julie Powell and Michelle Gable. If you have a special love for Paris, have always wanted to visit, or just enjoy armchair traveling, this collection won’t disappoint you.

A Paris All Your Own: Bestselling Women Writers on the City of Light, edited by Eleanor Brown: A highly enjoyable set of 18 autobiographical essays that celebrate what’s wonderful about the place but also acknowledge disillusionment; highlights are from Maggie Shipstead, Paula McLain, Therese Anne Fowler, Jennifer Coburn, Julie Powell and Michelle Gable. If you have a special love for Paris, have always wanted to visit, or just enjoy armchair traveling, this collection won’t disappoint you. Ashland & Vine by John Burnside: Essentially, it’s about the American story, individual American stories, and how these are constructed out of the chaos and violence of the past – all filtered through a random friendship that forms between a film student and an older woman in the Midwest. This captivated me from the first page.

Ashland & Vine by John Burnside: Essentially, it’s about the American story, individual American stories, and how these are constructed out of the chaos and violence of the past – all filtered through a random friendship that forms between a film student and an older woman in the Midwest. This captivated me from the first page. Tragic Shores: A Memoir of Dark Travel, Thomas H. Cook: In 28 non-chronological chapters, Cook documents journeys he’s made to places associated with war, massacres, doomed lovers, suicides and other evidence of human suffering. This is by no means your average travel book and it won’t suit those who seek high adventure and/or tropical escapism; instead, it’s a meditative and often melancholy picture of humanity at its best and worst. (Reviewed for

Tragic Shores: A Memoir of Dark Travel, Thomas H. Cook: In 28 non-chronological chapters, Cook documents journeys he’s made to places associated with war, massacres, doomed lovers, suicides and other evidence of human suffering. This is by no means your average travel book and it won’t suit those who seek high adventure and/or tropical escapism; instead, it’s a meditative and often melancholy picture of humanity at its best and worst. (Reviewed for  The Valentine House by Emma Henderson: This is a highly enjoyable family saga set mostly between 1914 and 1976 at an English clan’s summer chalet in the French Alps near Geneva, with events seen from the perspective of a local servant girl. You can really imagine yourself into all the mountain scenes and the book moves quickly –a great one to take on vacation.

The Valentine House by Emma Henderson: This is a highly enjoyable family saga set mostly between 1914 and 1976 at an English clan’s summer chalet in the French Alps near Geneva, with events seen from the perspective of a local servant girl. You can really imagine yourself into all the mountain scenes and the book moves quickly –a great one to take on vacation.

The 2017 Book Everybody Else Loved but I Didn’t: Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine by Gail Honeyman. (See

The 2017 Book Everybody Else Loved but I Didn’t: Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine by Gail Honeyman. (See  The Downright Strangest Book I Read This Year: An English Guide to Birdwatching by Nicholas Royle.

The Downright Strangest Book I Read This Year: An English Guide to Birdwatching by Nicholas Royle. The Best First Line of the Year: “History has failed us, but no matter.” (Pachinko, Min Jin Lee)

The Best First Line of the Year: “History has failed us, but no matter.” (Pachinko, Min Jin Lee) Now in its third year, the Best Small Fictions anthology collects the year’s best short stories under 1000 words. (I reviewed the two previous volumes for

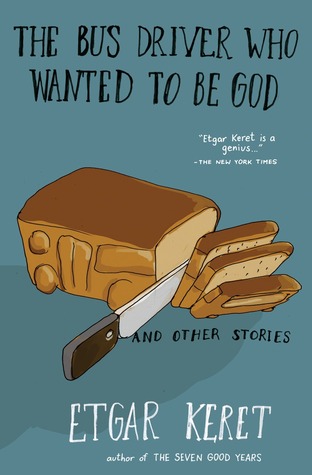

Now in its third year, the Best Small Fictions anthology collects the year’s best short stories under 1000 words. (I reviewed the two previous volumes for  How can you not want to read a book with that title? Unfortunately, “The Story about a Bus Driver Who Wanted to Be God” is the first story and probably the best, so it’s all a slight downhill journey from there. That story stars a bus driver who’s weighing justice versus mercy in his response to one lovelorn passenger, and retribution is a recurring element in the remainder of the book. Most stories are just three to five pages long. Important characters include an angel who can’t fly, visitors from the mouth of Hell in Uzbekistan, and an Israeli ex-military type with the ironic surname of Goodman who’s hired to assassinate a Texas minister for $30,000. You can never predict what decisions people will make, Keret seems to be emphasizing, or how they’ll choose to justify themselves; “Everything in life is just luck.”

How can you not want to read a book with that title? Unfortunately, “The Story about a Bus Driver Who Wanted to Be God” is the first story and probably the best, so it’s all a slight downhill journey from there. That story stars a bus driver who’s weighing justice versus mercy in his response to one lovelorn passenger, and retribution is a recurring element in the remainder of the book. Most stories are just three to five pages long. Important characters include an angel who can’t fly, visitors from the mouth of Hell in Uzbekistan, and an Israeli ex-military type with the ironic surname of Goodman who’s hired to assassinate a Texas minister for $30,000. You can never predict what decisions people will make, Keret seems to be emphasizing, or how they’ll choose to justify themselves; “Everything in life is just luck.” At any rate, I enjoyed Pearlman’s stories well enough. They all apparently take place in suburban Boston and many consider unlikely romances. My favorite was “Castle 4,” set in an old hospital. Zephyr, an anesthetist, falls in love with a cancer patient, while a Filipino widower who works as a security guard forms a tender relationship with the gift shop lady who sells his disabled daughter’s wood carvings. I also liked “Tenderfoot,” in which a pedicurist helps an art historian see that his heart is just as hard as his feet and that may be why he has an estranged wife. “Blessed Harry” amused me because the setup is a bogus e-mail requesting that a Latin teacher come speak at King’s College London (where I used to work). Two stories in a row (four in total, I’m told) center around Rennie’s antique shop – a little too Mitford quaint for me.

At any rate, I enjoyed Pearlman’s stories well enough. They all apparently take place in suburban Boston and many consider unlikely romances. My favorite was “Castle 4,” set in an old hospital. Zephyr, an anesthetist, falls in love with a cancer patient, while a Filipino widower who works as a security guard forms a tender relationship with the gift shop lady who sells his disabled daughter’s wood carvings. I also liked “Tenderfoot,” in which a pedicurist helps an art historian see that his heart is just as hard as his feet and that may be why he has an estranged wife. “Blessed Harry” amused me because the setup is a bogus e-mail requesting that a Latin teacher come speak at King’s College London (where I used to work). Two stories in a row (four in total, I’m told) center around Rennie’s antique shop – a little too Mitford quaint for me.