Three on a Theme for Father’s Day: Holt Poetry, Filgate & Virago Anthologies

A rare second post in a day for me; I got behind with my planned cat book reviews. I happen to have had a couple of fatherhood-themed books come my way earlier this year, an essay anthology and a debut poetry collection. To make it a trio, I finished an anthology of autobiographical essays about father–daughter relationships that I’d started last year.

What My Father and I Don’t Talk About: Sixteen Writers Break the Silence, ed. Michele Filgate (2025)

This follow-up to Michele Filgate’s What My Mother and I Don’t Talk About is an anthology of 16 compassionate, nuanced essays probing the intricacies of family relationships.

Understanding a father’s background can be the key to interpreting his later behavior. Isle McElroy had to fight for scraps of attention from their electrician father, who grew up in foster care; Susan Muaddi Darraj’s Palestinian father was sent to America to make money to send home. Such experiences might explain why the men were unreliable or demanding as adults. Patterns threaten to repeat across the generations: Andrew Altschul realizes his father’s hands-off parenting (he joked he’d changed a diaper “once”) was an outmoded convention he rejects in raising his own son; Jaquira Díaz learns that the depression she and her father battle stemmed from his tragic loss of his first family.

Understanding a father’s background can be the key to interpreting his later behavior. Isle McElroy had to fight for scraps of attention from their electrician father, who grew up in foster care; Susan Muaddi Darraj’s Palestinian father was sent to America to make money to send home. Such experiences might explain why the men were unreliable or demanding as adults. Patterns threaten to repeat across the generations: Andrew Altschul realizes his father’s hands-off parenting (he joked he’d changed a diaper “once”) was an outmoded convention he rejects in raising his own son; Jaquira Díaz learns that the depression she and her father battle stemmed from his tragic loss of his first family.

Some take the title brief literally: Heather Sellers dares to ask her father about his cross-dressing when she visits him in a nursing home; Nayomi Munaweera is pleased her 82-year-old father can escape his arranged marriage, but the domestic violence that went on in it remains unspoken. Tomás Q. Morín’s “Operation” has the most original structure, with the board game’s body parts serving as headings. All the essays display psychological insight, but Alex Marzano-Lesnevich’s—contrasting their father’s once-controlling nature with his elderly vulnerability—is the pinnacle.

Despite the heavy topics—estrangement, illness, emotional detachment—these candid pieces thrill with their variety and their resonant themes. (Read via Edelweiss)

Reprinted with permission from Shelf Awareness. (The above is my unedited version.)

Father’s Father’s Father by Dane Holt (2025)

Holt’s debut collection interrogates masculinity through poems about bodybuilders and professional wrestlers, teenage risk-taking and family misdemeanours.

Your father’s father’s father

poisoned a beautiful horse,

that’s the story. Now you know this

you’ve opened the door marked

‘Family History’.

(from “‘The Granaries are Bursting with Meal’”)

The only records found in my grandmother’s attic

were by scorned women for scorned women

written by men.

(from “Tammy Wynette”)

He writes in the wake of the deaths of his parents, which, as W.S. Merwin observed, makes one feel, “I could do anything,” – though here the poet concludes, “The answer can be nothing.” Stylistically, the collection is more various than cohesive, with some of the late poetry as absurdist as you find in Caroline Bird’s. My favourite poem is “Humphrey Bogart,” with its vision of male toughness reinforced by previous generations’ emotional repression:

My grandfather

never told his son that he loved him.

I said this to a group of strangers

and then said, Consider this:

his son never asked to be told.

They both loved

the men Humphrey Bogart played.

…

There was

one thing my grandfather could

not forgive his son for.

Eventually it was his son’s dying, yes.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free e-copy for review.

Fathers: Reflections by Daughters, ed. Ursula Owen (1983; 1994)

“I doubt if my father will ever lose his power to wound me, and yet…”

~Eileen Fairweather

I read the introduction and first seven pieces (one of them a retelling of a fairy tale) last year and reviewed that first batch here. Some common elements I noted in those were service in a world war, Freudian interpretation, and the alignment of the father with God. The writers often depicted their fathers as unknown, aloof, or as disciplinarians. In the remainder of the book, I particularly noted differences in generations and class. Father and daughter are often separated by 40–55 years. The men work in industry; their daughters turn to academia. Her embrace of radicalism or feminism can alienate a man of conservative mores.

Sometimes a father is defined by his emotional or literal absence. Dinah Brooke addresses her late father directly: “Obsessed with you for years, but blind – seeing only the huge holes you had left in my life, and not you at all. … I did so want someone to be a father to me. You did the best you could. It wasn’t a lot. The desire was there, but the execution was feeble.” Had Mary Gordon been tempted to romanticize her father, who died when she was seven, that aim was shattered when she learned how much he’d lied about and read his reactionary and ironically antisemitic writings (given that he was a Jew who converted to Catholicism).

Sometimes a father is defined by his emotional or literal absence. Dinah Brooke addresses her late father directly: “Obsessed with you for years, but blind – seeing only the huge holes you had left in my life, and not you at all. … I did so want someone to be a father to me. You did the best you could. It wasn’t a lot. The desire was there, but the execution was feeble.” Had Mary Gordon been tempted to romanticize her father, who died when she was seven, that aim was shattered when she learned how much he’d lied about and read his reactionary and ironically antisemitic writings (given that he was a Jew who converted to Catholicism).

I mostly skipped over the quotes from novels and academic works printed between the essays. There are solid pieces by Adrienne Rich, Michèle Roberts, Sheila Rowbotham, and Alice Walker, but Alice Munro knocks all the other contributors into a cocked hat with “Working for a Living,” which is as detailed and psychologically incisive as one of her stories (cf. The Beggar Maid with its urban/rural class divide). Her parents owned a fox farm but, as it failed, her father took a job as night watchman at a factory. She didn’t realize, until one day when she went in person to deliver a message, that he was a janitor there as well.

This was a rewarding collection to read and I will keep it around for models of autobiographical writing, but it now feels like a period piece: the fact that so many of the fathers had lived through the world wars, I think, might account for their cold and withdrawn nature – they were damaged, times were tough, and they believed they had to be an authority figure. Things have changed, somewhat, as the Filgate anthology reflects, though father issues will no doubt always be with us. (Secondhand – National Trust bookshop)

June Releases by Caroline Bird, Kathleen Jamie, Glynnis MacNicol and Naomi Westerman

These four books by women all incorporate life writing to an extent. Although the forms differ, a common theme – as in the other June releases I’ve reviewed, Sandwich and Others Like Me – is grappling with what a woman’s life should be, especially for those who have taken an unconventional path (i.e. are queer or childless) or are in midlife or later. I’ve got a poet up to her usual surreal shenanigans but with a new focus on lesbian parenting; a hybrid collection of poetry and prose giving snapshots of nature in crisis; an account of a writer’s hedonistic month in pandemic-era Paris; and mordant essays about death culture.

Ambush at Still Lake by Caroline Bird

Caroline Bird has become one of my favourite contemporary poets over the past few years. Her verse is joyously cheeky and absurdist. A great way to sample it is via her selected poems, Rookie. This seventh collection is muted by age and circumstance – multiple weddings and a baby – but still hilarious in places. Instead of rehab or hospital as in In These Days of Prohibition, the setting is mostly the domestic sphere. Even here, bizarre things happen. The police burst in at 4 a.m. for no particular reason; search algorithms and the baby monitor go haywire. Her brother calls to deliver a paranoid rant (in “Up and at ’Em”), while Nannie Edna’s dying wish is to dangle her great-grandson from her apartment window (in “Last Rites”). The clinic calls to announce that their sperm donor was a serial killer – then ‘oops, wrong vial, never mind!’ A toddler son’s strange and megalomaniac demands direct their days. My two favourites were “Ants,” in which a kitchen infestation signals general chaos, and “The Frozen Aisle,” in which a couple scrambles to finish the grocery shop and get home to bed before a rare horny moment passes. A lesbian pulp fiction cover, mischievous wit and topics of addiction and queer parenting: this is not your average poetry.

Caroline Bird has become one of my favourite contemporary poets over the past few years. Her verse is joyously cheeky and absurdist. A great way to sample it is via her selected poems, Rookie. This seventh collection is muted by age and circumstance – multiple weddings and a baby – but still hilarious in places. Instead of rehab or hospital as in In These Days of Prohibition, the setting is mostly the domestic sphere. Even here, bizarre things happen. The police burst in at 4 a.m. for no particular reason; search algorithms and the baby monitor go haywire. Her brother calls to deliver a paranoid rant (in “Up and at ’Em”), while Nannie Edna’s dying wish is to dangle her great-grandson from her apartment window (in “Last Rites”). The clinic calls to announce that their sperm donor was a serial killer – then ‘oops, wrong vial, never mind!’ A toddler son’s strange and megalomaniac demands direct their days. My two favourites were “Ants,” in which a kitchen infestation signals general chaos, and “The Frozen Aisle,” in which a couple scrambles to finish the grocery shop and get home to bed before a rare horny moment passes. A lesbian pulp fiction cover, mischievous wit and topics of addiction and queer parenting: this is not your average poetry.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

A sample poem:

Siblings

A woman gave birth

to the reincarnation

of Gilbert and Sullivan

or rather, two reincarnations:

one Gilbert, one Sullivan.

What are the odds

of both being resummoned

by the same womb

when they could’ve been

a blue dart frog

and a supply teacher

on separate continents?

Yet here they were, squidged

into a tandem pushchair

with their best work

behind them, still smarting

from the critical reception

of their final opera

described as ‘but an echo’

of earlier collaborations.

Cairn by Kathleen Jamie

As she approached age 60, Kathleen Jamie found her style changing. Whereas her other essay collections alternate extended nature or travel pieces with few-page vignettes, Cairn eschews longer material and instead alternates poems with micro-essays on climate crisis and outdoor experiences. In the prologue she calls these “distillations and observations. Testimonies” that she has assembled into “A cairn of sorts.”

As she approached age 60, Kathleen Jamie found her style changing. Whereas her other essay collections alternate extended nature or travel pieces with few-page vignettes, Cairn eschews longer material and instead alternates poems with micro-essays on climate crisis and outdoor experiences. In the prologue she calls these “distillations and observations. Testimonies” that she has assembled into “A cairn of sorts.”

As in Surfacing, she writes many of the autobiographical fragments in the second person. The book is melancholy at times, haunted by all that has been lost and will be lost in the future:

What do we sense on the moor but ghost folk,

ghost deer, even ghost wolf. The path itself is a

phantom, almost erased in ling and yellow tormentil (from “Moor”)

In “The Bass Rock,” Jamie laments the effect that bird flu has had on this famous gannet colony and wishes desperately for better news:

The light glances on the water. The haze clears, and now the rock is visible; it looks depleted. But hallelujah, a pennant of twenty-odd gannets is passing, flying strongly, now rising now falling They’ll be Bass Rock birds. What use the summer sunlight, if it can’t gleam on a gannet’s back? You can only hope next year will be different. Stay alive! You call after the flying birds. Stay alive!

Natural wonders remind her of her own mortality and the insignificance of human life against deep time. “I can imagine the world going on without me, which one doesn’t at 30.” She questions the value of poetry in a time of emergency: “If we are entering a great dismantling, we can hardly expect lyric to survive. How to write a lyric poem?” (from “Summer”). The same could be said of any human endeavour in the face of extinction: We question the point but still we continue.

My two favourite pieces were “The Handover,” about going on an environmental march with her son and his friends in Glasgow and comparing it with the protests of her time (Greenham Common and nuclear disarmament) – doom and gloom was ever thus – and the title poem, which piles natural image on image like a cone of stones. Although I prefer the depth of Jamie’s other books to the breadth of this one, she is an invaluable nature writer for her wisdom and eloquence, and I am grateful we have heard from her again after five years.

With thanks to Sort Of Books for the free copy for review.

I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself: One Woman’s Pursuit of Pleasure in Paris by Glynnis MacNicol

I loved New York City freelance writer Glynnis MacNicol’s No One Tells You This (2018), which approached her 40th year as an adventure into the unknown. This second memoir is similarly frank and intrepid as MacNicol examines the unconscious rules that people set for women in their mid-forties and gleefully flouts them, remaining single and childfree and delighting in the freedom that allows her to book a month in Paris on a whim. She knows that she is an anomaly for being “untethered”; “I am ready for anything. To be anyone.”

I loved New York City freelance writer Glynnis MacNicol’s No One Tells You This (2018), which approached her 40th year as an adventure into the unknown. This second memoir is similarly frank and intrepid as MacNicol examines the unconscious rules that people set for women in their mid-forties and gleefully flouts them, remaining single and childfree and delighting in the freedom that allows her to book a month in Paris on a whim. She knows that she is an anomaly for being “untethered”; “I am ready for anything. To be anyone.”

This takes place in August 2021, when some pandemic restrictions were still in force, and she found the city – a frequent destination for her over the years – drained of locals, who were all en vacances, and largely empty of tourists, too. Although there was still a queue for the Mona Lisa, she otherwise found the Louvre very quiet, and could ride her borrowed bike through the streets without having to look out for cars. She and her single girlfriends met for rosé-soaked brunches and picnics, joined outdoor dance parties and took an island break.

And then there was the sex. MacNicol joined a hook-up app called Fruitz and met all sorts of men. She refused to believe that, just because she was 46 going on 47, she should be invisible or demure. “All the attention feels like pure oxygen. Anything is possible.” Seeing herself through the eyes of an enraptured 27-year-old Italian reminded her that her body was beautiful even if it wasn’t what she remembered from her twenties (“there is, on average, a five-year gap between current me being able to enjoy the me in the photos”). The book’s title is something she wrote while messaging with one of her potential partners.

As I wrote yesterday about Others Like Me, there are plenty of childless role models but you may have to look a bit harder for them. MacNicol does so by tracking down the Paris haunts of women writers such as Edith Wharton and Colette. She also interrogates this idea of women living a life of pleasure by researching the “odalisque” in 18th- and 19th-century art, as in the François Boucher painting on the cover. This was fun, provocative and thoughtful all at once; well worth seeking out for summer reading and armchair travelling.

(Read via Edelweiss) Published in the USA by Penguin Life/Random House.

Happy Death Club: Essays on Death, Grief & Bereavement across Cultures by Naomi Westerman

Like Erica Buist (This Party’s Dead) and Caitlin Doughty (Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, From Here to Eternity and Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs?), playwright Naomi Westerman finds the comical side of death. Part of 404 Ink’s Inklings series (“Big ideas, pocket-sized books” – perfect for anyone looking for short nonfiction for Novellas in November!), this is a collection of short essays about her own experiences of bereavement as well as her anthropological research into rituals and beliefs around death. “The Rat King of South London” is about her father’s sudden death from an abdominal aneurysm. An instantaneous death is a good one, she contends. More than 160,000 people die every day, and what to do with all those bodies is a serious question. A subversive sense of humour is there right from the start, as she gives a rundown of interment options. “Mummification: Beloved by Ancient Egyptians and small children going through their Ancient Egypt phase, it’s a classic for a reason!” Meanwhile, she legally owns her father’s plot so also buries dead pet rats there.

Like Erica Buist (This Party’s Dead) and Caitlin Doughty (Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, From Here to Eternity and Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs?), playwright Naomi Westerman finds the comical side of death. Part of 404 Ink’s Inklings series (“Big ideas, pocket-sized books” – perfect for anyone looking for short nonfiction for Novellas in November!), this is a collection of short essays about her own experiences of bereavement as well as her anthropological research into rituals and beliefs around death. “The Rat King of South London” is about her father’s sudden death from an abdominal aneurysm. An instantaneous death is a good one, she contends. More than 160,000 people die every day, and what to do with all those bodies is a serious question. A subversive sense of humour is there right from the start, as she gives a rundown of interment options. “Mummification: Beloved by Ancient Egyptians and small children going through their Ancient Egypt phase, it’s a classic for a reason!” Meanwhile, she legally owns her father’s plot so also buries dead pet rats there.

Other essays are about taking her mother’s ashes along on world travels, the funeral industry and “red market” sales of body parts, grief as a theme in horror films, the fetishization of dead female bodies, Mexico’s Day of the Dead festivities, and true crime obsession. In “Batman,” an excerpt from one of her plays, she goes to have a terrible cup of tea with the man she believes to be responsible for her mother’s death – a violent one, after leaving an abusive relationship. She also used the play to host an on-stage memorial for her mother since she wasn’t able to sit shiva. In the final title essay, Westerman tours lots of death cafés and finds comfort in shared experiences. These pieces are all breezy, amusing and easy to read, so it’s a shame that this small press didn’t achieve proper proofreading, making for a rather sloppy text, and that the content was overall too familiar for me.

With thanks to 404 Ink and publicist Claire Maxwell for the free copy for review.

Does one or more of these catch your eye?

What June releases can you recommend?

Recent Poetry Releases by Clarke, Galleymore, Hurst, and Minick

All caught up on March releases now. There’s a lot of nature and environmental awareness in these four poetry collections, but also pandemic lockdown experiences, folklore, travel, and an impasse over whether to have children. Three are from Carcanet Press, my UK poetry mainstay; one was my introduction to Madville Publishing (based in Lake Dallas, Texas). After my thoughts, I’ll give one sample poem from each book.

The Silence by Gillian Clarke

Clarke was the National Poet of Wales from 2008 to 2016. I ‘discovered’ her just last year through Making the Beds for the Dead, which shares with this eleventh collection a plague theme: there, the UK’s foot and mouth disease outbreak of 2001; here, Covid-19. Forced into stillness and attention to the wonders near home, the poet tracks nature through the seasons and hymns trees, sunsets and birds. Many poems are titled after months or calendar points such as Midsummer and Christmas Eve. She also commemorates Welsh landmarks and remembers her mother, a nurse.

The verse is full of colours and names of flora:

May-gold’s gone to seed, yellows fallen –

primrose, laburnum, Welsh poppy.

June is rose, magenta, purple,

pink clematis, mopheads of chives,

cranesbill flowering where it will,

a migration of foxgloves crossing the field.

(from “Late June”)

Even as she revels in beauty, though, she bears in mind suffering elsewhere:

There is time and silence

to tell the names of the dying, the dead,

under empty skies unscarred

by transatlantic planes.

(from “Spring Equinox, 2020”)

I noted alliteration (“At the tip of every twig, / a water-bead with the world in it”) and end rhymes (“After long isolation, in times like these, / in the world’s darkness, let us love like trees.”). All told, I found this collection lovely but samey and lacking bite. But Clarke is in her late eighties and has a large back catalogue for me to explore.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

Baby Schema by Isabel Galleymore

I knew Galleymore’s name from her appearance at the New Networks for Nature conference in 2018. The University of Birmingham lecturer’s second collection is a slant-wise look at environmental crisis and an impending decision about motherhood. The title comes from Konrad Lorenz’s identification of features that invite nurture. Galleymore edges towards the satirical fantasies of Caroline Bird or Patricia Lockwood as she imagines alternative scenarios of caregiving and contrasts sentimentality with indifference.

I knew Galleymore’s name from her appearance at the New Networks for Nature conference in 2018. The University of Birmingham lecturer’s second collection is a slant-wise look at environmental crisis and an impending decision about motherhood. The title comes from Konrad Lorenz’s identification of features that invite nurture. Galleymore edges towards the satirical fantasies of Caroline Bird or Patricia Lockwood as she imagines alternative scenarios of caregiving and contrasts sentimentality with indifference.

What is worthy of maternal concern? There are poems about a houseplant, a childhood doll, a soft toy glimpsed through a car window. A research visit to Disneyland Paris in the centenary year of the Walt Disney Company leads to marvelling at the surreality of consumerism. Does cuteness merit survival?

Because rhinos haven’t adopted the small

muscle responsible for puppy dog eyes,

the species goes bankrupt.

Its regional stores close down.

(from “The Pitch”)

The speaker acknowledges how gooey she goes over dogs (“Morning”) and kittens (“So Adorable”). But “Mothers” and “Chosen” voice ambivalence or even suspicion about offspring, and “Fable” spins a mild nightmare of infants taking over (“babies nesting in other babies / of cliff and reef and briar”). By the time, in “More and More,” she pictures a son, “a sticky-fingered, pint-sized / version of myself toddling through the aisles,” she concludes that we live in a depleted “world better off without him.”

Extinction and eco-grief on the one hand, yes, but the implacability of biological cycles on the other:

That night, when I got home, I learnt

a tree frog species had been lost

and my body was releasing its usual sum of blood.

I only had a few years left, my mother

often warned

(from “Release”)

Sardonic yet humane, and reassuringly indecisive, this is a poetry highlight of the year so far for me. I’ll go back and find her debut, Significant Other, too.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free e-copy for review.

The Iron Bridge by Rebecca Hurst

Manchester-based Hurst’s debut full-length collection struck me first for its gorgeous nature poetry arising from a series of walks. Most of these are set in Southern England in the current century, but date and location stamps widen the view as far as 1976 in the one case and Massachusetts in the other. The second section entices with its titles drawn from folklore and mythology: “How the Fox Lost His Brush,” “The Animal Bridegroom,” “The Needle Prince,” “And then we saw the daughter of the minotaur.”

An unexpected favourite, for its alliteration, assonance and book metaphors in the first stanza, was “Cabbage”:

Slung from a trug it rumbles across

the kitchen table, this flabby magenta fist

of stalk and leaf, this bundle of pages

flopping loose from their binding

this globe cleaved with a grunt leaning hard

on the blade

Part III, “Night Journeys,” has more nature verse and introduces a fascination with Russia that continues through the rest of the book. I loved the mischievous quartet of “Field Notes” prose poems about “The careless lover,” “The theatrical lover,” “The corresponding lover,” and “The satisfying lover” – three of them male and one female. The final section, “An Explorer’s Handbook,” includes found poems adapted from the published work of travel writers contemporary (Christina Dodwell) and Victorian (nurse Kate Marsden). Another series, “The Emotional Lives of Soviet Objects,” gives surprising power to a doily, a slipper and a potato peeler.

There’s a huge range of form and subject matter here, but the language is unfailingly stunning. Another standout from 2024 and a poet to watch. From my other Carcanet reading, I’d liken this most to work by Laura Scott and Helen Tookey.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free e-copy for review.

The Intimacy of Spoons by Jim Minick

A new publisher and author for me. Minick has also published fiction and nonfiction; this is his third poetry collection. Between the opener, “To Spoon,” and the title piece that closes the book, there are five more spoon-themed poems that create a pleasing thematic throughline. Why spoons? Unlike potentially violent knives and forks, which cut and spear, spoons are gentle. They’re also reflective surfaces, and because of their concavity, they can hold things and nestle together. In “The Oldest Spoon,” they even bring to mind a guiding constellation.

A new publisher and author for me. Minick has also published fiction and nonfiction; this is his third poetry collection. Between the opener, “To Spoon,” and the title piece that closes the book, there are five more spoon-themed poems that create a pleasing thematic throughline. Why spoons? Unlike potentially violent knives and forks, which cut and spear, spoons are gentle. They’re also reflective surfaces, and because of their concavity, they can hold things and nestle together. In “The Oldest Spoon,” they even bring to mind a guiding constellation.

The rest of the book is full of North American woodland and coastal scenes and wildlife. Minick displays genuine affection for and familiarity with birds. He is also realistic in noting all that is lost with habitat destruction and dwindling populations. “Lasts” describes the bittersweet sensation of loving what is disappearing: “Goodbye, we always say too late, / or we never get a chance to say at all.” He wrestles with human mortality, too, through elegies and minor concerns about his own ageing body. I loved the seasonal imagery and alliteration in “Spangled” and the Rolling Stones refrain to “Gas,” about boat-tailed grackles encountered in the parking lot at a Georgia truck stop.

Why not embrace all that is ugly

& holy & here—the grackle’s song

that isn’t a song, a breadcrumb dropped,

the shiny ribbon of gasoline

that will get me closer to home.

For something a bit different, I appreciated the true-crime monologue of “Tim Slack, the Fix-It Man.” With playfulness and variety, Minick gives us new views on the everyday – which is exactly why it is worth reading poetry.

With thanks to Madville Publishing for the free e-copy for review.

Miscellaneous #ReadIndies Reviews: Mostly Poetry + Brown, Sands

Catching up on a few final #ReadIndies contributions in early March! Short responses to some indie reading I did from my shelves over the course of last month.

Bloodaxe Books:

Parables & Faxes by Gwyneth Lewis (1995)

I was surprised to discover this was actually my fourth book by Lewis, a bilingual Welsh author: two memoirs, one of depression and one about marriage; and now two poetry collections. The table of contents suggest there are only 16 poems in the book, but most of the titles are actually headings for sections of anywhere between 6 and 16 separate poems. She ranges widely at home and abroad, as in “Welsh Espionage” and the “Illinois Idylls.” “I shall taste the tang / of travel on the atlas of my tongue,” Lewis writes, an example of her alliteration and sibilance. She’s also big on slant and internal rhymes – less so on end rhymes, though there are some. Medieval history and theology loom large, with the Annunciation featuring more than once. I couldn’t tell you now what that many of the poems are about, but Lewis’s telling is always memorable.

I was surprised to discover this was actually my fourth book by Lewis, a bilingual Welsh author: two memoirs, one of depression and one about marriage; and now two poetry collections. The table of contents suggest there are only 16 poems in the book, but most of the titles are actually headings for sections of anywhere between 6 and 16 separate poems. She ranges widely at home and abroad, as in “Welsh Espionage” and the “Illinois Idylls.” “I shall taste the tang / of travel on the atlas of my tongue,” Lewis writes, an example of her alliteration and sibilance. She’s also big on slant and internal rhymes – less so on end rhymes, though there are some. Medieval history and theology loom large, with the Annunciation featuring more than once. I couldn’t tell you now what that many of the poems are about, but Lewis’s telling is always memorable.

Sample lines:

For the one

who said yes,

how many

said no?

…

But those who said no

for ever knew

they were damned

to the daily

as they’d disallowed

reality’s madness,

its astonishment.

(from “The ‘No’ Madonnas,” part of “Parables & Faxes”)

(Secondhand purchase – Westwood Books, Sedbergh)

&

Fields Away by Sarah Wardle (2003)

Wardle’s was a new name for me. I saw two of her collections at once and bought this one as it was signed and the themes sounded more interesting to me. It was her first book, written after inpatient treatment for schizophrenia. Many of the poems turn on the contrast between city (London Underground) and countryside (fields and hedgerows). Religion, philosophy, and Greek mythology are common points of reference. End rhymes can be overdone here, and I found a few of the poems unsubtle (“Hubris” re: colonizers and “How to Be Bad” about daily acts of selfishness vs. charity). However, there are enough lovely ones to compensate: “Flight,” “Word Tasting” (mimicking a wine tasting), “After Blake” (reworking “Jerusalem” with “And will chainsaws in modern times / roar among England’s forests green?”), “Translations” and “Word Hill.”

Wardle’s was a new name for me. I saw two of her collections at once and bought this one as it was signed and the themes sounded more interesting to me. It was her first book, written after inpatient treatment for schizophrenia. Many of the poems turn on the contrast between city (London Underground) and countryside (fields and hedgerows). Religion, philosophy, and Greek mythology are common points of reference. End rhymes can be overdone here, and I found a few of the poems unsubtle (“Hubris” re: colonizers and “How to Be Bad” about daily acts of selfishness vs. charity). However, there are enough lovely ones to compensate: “Flight,” “Word Tasting” (mimicking a wine tasting), “After Blake” (reworking “Jerusalem” with “And will chainsaws in modern times / roar among England’s forests green?”), “Translations” and “Word Hill.”

Favourite lines:

(oh, but the last word is cringe!)

Catkin days and hedgerow hours

fleet like shafts of chapel sun.

Childhood in a cobwebbed bower

guards a treasure chest of fun.

(from “Age of Awareness”)

(Secondhand purchase – Carlisle charity shop)

Carcanet Press:

Tripping Over Clouds by Lucy Burnett (2019)

The title is a setup for the often surrealist approach, but where another Carcanet poet, Caroline Bird, is warm and funny with her absurdism, Burnett is just … weird. Like, I’d get two stanzas into a poem and have no idea what was going on or what she was trying to say because of the incomplete phrases and non-standard punctuation. Still, this is a long enough collection that there are a good number of standouts about nature and relationships, and alliteration and paradoxes are used to good effect. I liked the wordplay in “The flight of the guillemet” and the off-beat love poem “Beer for two in Brockler Park, Berlin.” The noteworthy Part III is composed of 34 ekphrastic poems, each responding to a different work of (usually modern) art.

The title is a setup for the often surrealist approach, but where another Carcanet poet, Caroline Bird, is warm and funny with her absurdism, Burnett is just … weird. Like, I’d get two stanzas into a poem and have no idea what was going on or what she was trying to say because of the incomplete phrases and non-standard punctuation. Still, this is a long enough collection that there are a good number of standouts about nature and relationships, and alliteration and paradoxes are used to good effect. I liked the wordplay in “The flight of the guillemet” and the off-beat love poem “Beer for two in Brockler Park, Berlin.” The noteworthy Part III is composed of 34 ekphrastic poems, each responding to a different work of (usually modern) art.

Favourite lines:

This is a place of uncalled-for space

and by the grace of the big sky,

and the serrated under-silhouette of Skye,

an invitation to the sea unfolds

to come and dine with mountain.

(from “Big Sands”)

(New (bargain) purchase – Waterstones website)

&

The Met Office Advises Caution by Rebecca Watts (2016)

The problem with buying a book mostly for the title is that often the contents don’t live up to it. (Some of my favourite ever titles – An Arsonist’s Guide to Writers’ Homes in New England, The Voluptuous Delights of Peanut Butter and Jam – were of books I couldn’t get through). There are a lot of nature poems here, which typically would be enough to get me on board, but few of them stood out to me. Trees, bats, a dead hare on the road; maps, Oxford scenes, Christmas approaching. All nice enough; maybe it’s just that the poems don’t seem to form a cohesive whole. Easy to say why I love or hate a poet’s style; harder to explain indifference.

The problem with buying a book mostly for the title is that often the contents don’t live up to it. (Some of my favourite ever titles – An Arsonist’s Guide to Writers’ Homes in New England, The Voluptuous Delights of Peanut Butter and Jam – were of books I couldn’t get through). There are a lot of nature poems here, which typically would be enough to get me on board, but few of them stood out to me. Trees, bats, a dead hare on the road; maps, Oxford scenes, Christmas approaching. All nice enough; maybe it’s just that the poems don’t seem to form a cohesive whole. Easy to say why I love or hate a poet’s style; harder to explain indifference.

Sample lines:

Branches lash out; old trees lie down and don’t get up.

A wheelie bin crosses the road without looking,

lands flat on its face on the other side, spilling its knowledge.

(from the title poem)

(New (bargain) purchase – Amazon with Christmas voucher)

Faber:

Places I’ve Taken My Body by Molly McCully Brown (2020)

The title signals right away how these linked autobiographical essays split the ‘I’ from the body – Brown resents the fact that disability limits her experience. Oxygen deprivation at their premature birth led to her twin sister’s death and left her with cerebral palsy severe enough that she generally uses a wheelchair. In Bologna for a travel fellowship, she writes, “There are so many places that I want to be, but I can’t take my body anywhere. But I must take my body everywhere.” A medieval city is particularly unfriendly to those with mobility challenges, but chronic pain and others’ misconceptions (e.g. she overheard a guy on her college campus lamenting that she’d die a virgin) follow her everywhere.

The title signals right away how these linked autobiographical essays split the ‘I’ from the body – Brown resents the fact that disability limits her experience. Oxygen deprivation at their premature birth led to her twin sister’s death and left her with cerebral palsy severe enough that she generally uses a wheelchair. In Bologna for a travel fellowship, she writes, “There are so many places that I want to be, but I can’t take my body anywhere. But I must take my body everywhere.” A medieval city is particularly unfriendly to those with mobility challenges, but chronic pain and others’ misconceptions (e.g. she overheard a guy on her college campus lamenting that she’d die a virgin) follow her everywhere.

A poet, Brown earned minor fame for her first collection, which was about historical policies of enforced sterilization for the disabled and mentally ill in her home state of Virginia. She is also a Catholic convert. I appreciated her exploration of poetry and faith as ways of knowing: “both … a matter of attending to the world: of slowing my pace, and focusing my gaze, and quieting my impatient, indignant, protesting heart long enough for the hard shell of the ordinary to break open and reveal the stranger, subtler singing underneath.” This is part of a terrific run of three pieces, the others about sex as a disabled person and the odious conservatism of the founders of Liberty University. Also notable: “Fragments, Never Sent,” letters to her twin; and “Frankenstein Abroad,” about rereading this novel of ostracism at its 200th anniversary. (Secondhand purchase – Amazon)

New River Books:

The Hedgehog Diaries: A Story of Faith, Hope and Bristle by Sarah Sands (2023)

Reasons for reading: 1) I’d enjoyed Sands’s The Interior Silence and 2) Who can resist a book about hedgehogs? She covers a brief slice of 2021–22 when her aged father was dying in a care home. Having found an ill hedgehog in her garden and taken it to a local sanctuary, she developed an interest in the plight of hedgehogs. In surveys they’re the UK’s favourite mammal, but it’s been years since I saw one alive. Sands brings an amateur’s enthusiasm to her research into hedgehogs’ place in literature, philosophy and science. She visits rescue centres, meets activists in Oxfordshire and Shropshire who have made hedgehog welfare a local passion, and travels to Uist to see where hedgehogs were culled in 2004 to protect ground-nesting birds’ eggs. The idea is to link personal brushes with death with wider threats of extinction. Unfortunately, Sands’s lack of expertise is evident. This was well-meaning, but inconsequential and verging on twee. (Christmas gift from my wishlist)

Reasons for reading: 1) I’d enjoyed Sands’s The Interior Silence and 2) Who can resist a book about hedgehogs? She covers a brief slice of 2021–22 when her aged father was dying in a care home. Having found an ill hedgehog in her garden and taken it to a local sanctuary, she developed an interest in the plight of hedgehogs. In surveys they’re the UK’s favourite mammal, but it’s been years since I saw one alive. Sands brings an amateur’s enthusiasm to her research into hedgehogs’ place in literature, philosophy and science. She visits rescue centres, meets activists in Oxfordshire and Shropshire who have made hedgehog welfare a local passion, and travels to Uist to see where hedgehogs were culled in 2004 to protect ground-nesting birds’ eggs. The idea is to link personal brushes with death with wider threats of extinction. Unfortunately, Sands’s lack of expertise is evident. This was well-meaning, but inconsequential and verging on twee. (Christmas gift from my wishlist)

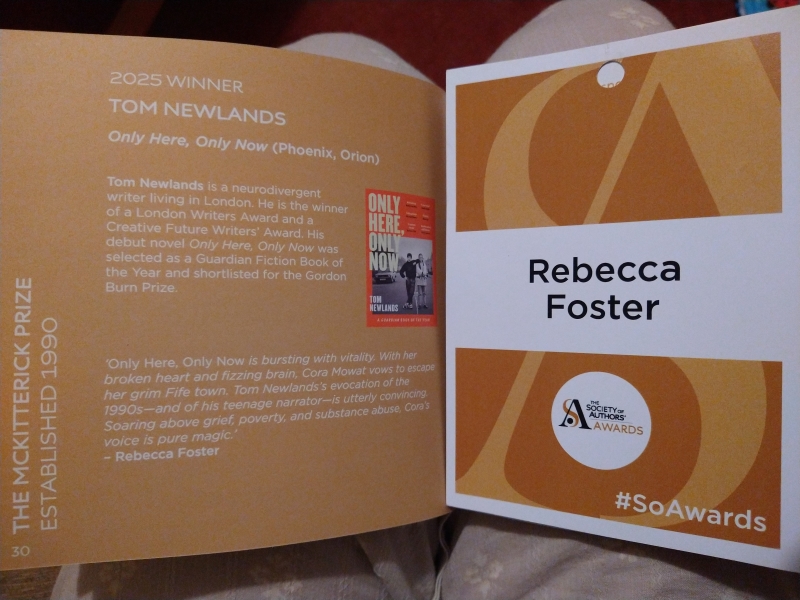

Prize Updates: McKitterick Prize Winner and Wainwright Prize Longlists

It was my second year as a first-round manuscript judge for the McKitterick Prize; have a look at my rundown of the shortlist here.

The winner, Louise Kennedy, and runner-up, Liz Hyder, were announced on 29 June. (Nominee Aamina Ahmad won a different SoA Award that night, the Gordon Bowker Volcano Prize for a novel focusing on the experience of travel away from home.) Other recipients included Travis Alabanza, Caroline Bird, Bonnie Garmus and Nicola Griffith. For more on all of this year’s SoA Award winners, see their website.

The winner, Louise Kennedy, and runner-up, Liz Hyder, were announced on 29 June. (Nominee Aamina Ahmad won a different SoA Award that night, the Gordon Bowker Volcano Prize for a novel focusing on the experience of travel away from home.) Other recipients included Travis Alabanza, Caroline Bird, Bonnie Garmus and Nicola Griffith. For more on all of this year’s SoA Award winners, see their website.

I’m a big fan of the Wainwright Prize for nature and conservation writing, and have been following it particularly closely since 2020, when I happened to read most of the nominees. In 2021 I also managed to read quite a lot from the longlists; 2022, the first year of an additional prize for children’s literature, saw me reading about a third of the total nominees.

This is the third year that I’ve been part of an “academy” of bloggers, booksellers, former judges and previously shortlisted authors asked to comment on a very long list of publisher submissions. I’m delighted that a few of my preferences made it through to the longlists.

My taste generally runs more to the narrative nature writing than the popular science or travel-based books. I find I’ve read just two from the Nature list (Bersweden and Huband) and one each from Conservation (Pavelle) and Children’s (Hargrave) so far.

The 2023 James Cropper Wainwright Prize for Nature Writing longlist:

- The Swimmer: The Wild Life of Roger Deakin, Patrick Barkham (Hamish Hamilton)

- The Flow: Rivers, Water and Wildness, Amy-Jane Beer (Bloomsbury)

- Where the Wildflowers Grow, Leif Bersweden (Hodder)

- Twelve Words for Moss, Elizabeth-Jane Burnett (Allen Lane)

- Cacophony of Bone, Kerri ní Dochartaigh (Canongate)

- Sea Bean, Sally Huband (Hutchinson)

- Ten Birds that Changed the World, Stephen Moss (Faber)

- A Line in the World: A Year on the North Sea Coast, Dorthe Nors, translated by Caroline Waight (Pushkin)

- The Golden Mole: And Other Living Treasure, Katherine Rundell, illustrated by Talya Baldwin (Faber)

- Belonging: Natural Histories of Place, Identity and Home, Amanda Thomson (Canongate)

- Why Women Grow: Stories of Soil, Sisterhood and Survival, Alice Vincent (Canongate)

- Landlines, Raynor Winn (Penguin)

The 2023 James Cropper Wainwright Prize for Writing on Conservation longlist:

- Sarn Helen: A Journey Through Wales, Past, Present and Future, Tom Bullough, illustrated by Jackie Morris (Granta)

- Beastly: A New History of Animals and Us, Keggie Carew (Canongate)

- Rewilding the Sea: How to Save Our Oceans, Charles Clover (Ebury)

- Birdgirl, Mya-Rose Craig (Jonathan Cape)

- The Orchid Outlaw, Ben Jacob (John Murray)

- Elixir: In the Valley at the End of Time, Kapka Kassabova (Jonathan Cape)

- Rooted: How Regenerative Farming Can Change the World, Sarah Langford (Viking)

- Black Ops and Beaver Bombing: Adventures with Britain’s Wild Mammals, Fiona Mathews and Tim Kendall (Oneworld)

- Forget Me Not, Sophie Pavelle (Bloomsbury)

- Fen, Bog, and Swamp: A Short History of Peatland Destruction and its Role in the Climate Crisis, Annie Proulx (Fourth Estate)

- The Lost Rainforests of Britain, Guy Shrubsole (HarperCollins)

- Nomad Century: How to Survive the Climate Upheaval, Gaia Vince (Allen Lane)

The 2023 James Cropper Wainwright Prize for Children’s Writing on Nature and Conservation longlist:

- The Earth Book, Hannah Alice (Nosy Crow)

- The Light in Everything, Katya Balen, illustrated by Sydney Smith (Bloomsbury)

- Billy Conker’s Nature-Spotting Adventure, Conor Busuttil (O’Brien)

- Protecting the Planet: The Season of Giraffes, Nicola Davies, illustrated by Emily Sutton (Walker)

- Blobfish, Olaf Falafel (Walker)

- A Friend to Nature, Laura Knowles, illustrated by Rebecca Gibbon (Welbeck)

- Spark, M G Leonard (Walker)

- A Wild Child’s Book of Birds, Dara McAnulty (Macmillan)

- Leila and the Blue Fox, Kiran Millwood Hargrave, illustrated by Tom de Freston (Hachette Children’s Group)

- The Zebra’s Great Escape, Katherine Rundell, illustrated by Sara Ogilvie (Bloomsbury)

- Archie’s Apple, Hannah Shuckburgh, illustrated by Octavia Mackenzie (Little Toller)

- Grandpa and the Kingfisher, Anna Wilson, illustrated by Sarah Massini (Nosy Crow)

It’s impressive that women writers are represented so well this year: 9/12 for Nature, 8/12 for Conservation, and 8/12 for Children’s. Amusingly, Katherine Rundell is on TWO of the lists. There are also, refreshingly, several BIPOC authors, and – I think for the first time ever – a work in translation (A Line in the World by Dorthe Nors, which I have as a set-aside proof copy and will get back into at once).

Here is where I have to admit that quite a number of the nominees, overall, are books I DNFed, authors whose work I’ve tried before and not enjoyed, or books I’ve been turned off of by the reviews. I’ll not mention these by name just now, and will leave any predictions for a future date when I’ve read a few more of the nominees. It seems that I’m most likely to catch up with the majority of the children’s longlist, if anything.

The shortlists will be announced on 10 August, and winners will be announced on 14 September at a 10th Anniversary live event held as part of the Kendal Mountain Festival in Cumbria (tickets available here).

See any nominees you’ve read? Who would you like to see shortlisted?

September Releases by John Clegg & Tom Gauld (Lots More to Come!)

There aren’t enough hours in the day, or days left in this month, to write up all the terrific September releases I’ve read. The nonfiction fell into two broad thematic camps: books about books (Remainders of the Day by Shaun Bythell and Blurb Your Enthusiasm by Louise Willder still to come), or books about death (What Remains? by Rupert Callender, And Finally by Henry Marsh, and Sinkhole by Juliet Patterson still to come). However, I’ll start off with the two I happen to have written about so far, which are (the odd one out) poetry about science and watery travel, and bookish cartoons. Both:

Aliquot by John Clegg

This is the second Carcanet collection by the London bookseller. An aliquot is a sample, a part that represents the whole; a scientific counterpart to synecdoche. It’s a perfect word for what poetry can do: point at larger truths through the pinpricks of meaning found in the everyday. The title poem juxtaposes two moments where the poet muses on the part/whole dichotomy: watching a catering school student and teacher transferring peas from one container to another and spotting two cellists on a tube train. Drawn in by detail, we observe the inevitable movement from separation to togetherness.

This is the second Carcanet collection by the London bookseller. An aliquot is a sample, a part that represents the whole; a scientific counterpart to synecdoche. It’s a perfect word for what poetry can do: point at larger truths through the pinpricks of meaning found in the everyday. The title poem juxtaposes two moments where the poet muses on the part/whole dichotomy: watching a catering school student and teacher transferring peas from one container to another and spotting two cellists on a tube train. Drawn in by detail, we observe the inevitable movement from separation to togetherness.

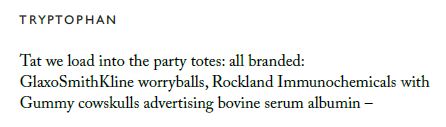

A high point is “A Gene Sequence,” about an administrator working behind the scenes at a genomics conference on a Cambridge campus: each poem is named after a different amino acid and the lines (sometimes with the help of extreme enjambment) always begin with the arrangement of A, C, G, and T that encodes them. Here’s an example:

Much of the imagery is maritime, with the occasional reference to a desert (“Language as Sonora”) or settlement (“Dormer Windows” and “Quebec City”). The locations include a science campus and a storm-threatened hotel (“Hurricane Joaquin,” one of my favourites). A proverb is described as being as potent as a raw onion. Here’s a lynx you’ll never see – but she will see you. Like in a Caroline Bird collection, there’s many an absurd or imagined situation. The vocabulary is unusual, sometimes lofty: “their cursory repertoire of query.” Alliteration teems, as in “The High Lama Explains How Items Are Procured for Shangri-La.” Overall, a noteworthy and unique collection that I’d recommend.

A favourite, apropos of nothing stanza from “Lucan – The Waterline”:

There is a kind of crab known to devour human flesh.

There is a shelf five storeys undersea

Where small yachts pile up like bric-a-brac.

There is a town in Maryland called Alibi.

With thanks to Carcanet for the advanced e-copy for review.

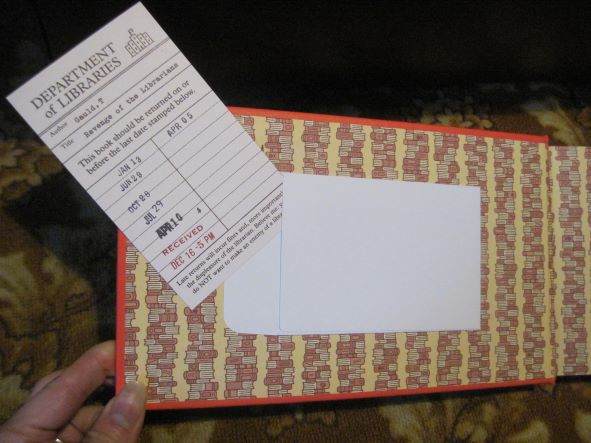

Revenge of the Librarians by Tom Gauld

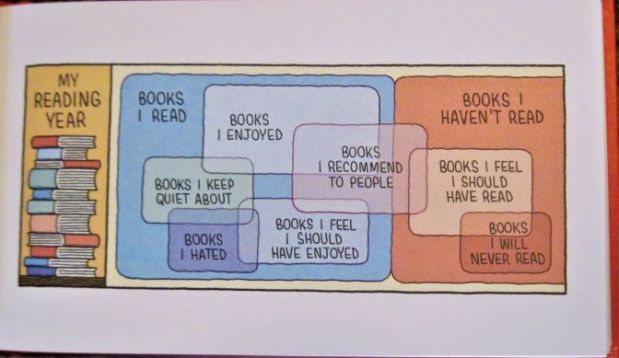

You have probably seen Gauld’s cartoons in the Guardian, New Scientist or New Yorker. I’ve saved clippings of my favourite bookish ones over the years. They’re full of literary in-jokes and bibliophile problems, and divided about equally between a writer’s perspective and a reader’s: the struggle for inspiration and novelty on the one hand, and the battle with the TBR and the impulse to read what one feels one should versus what one enjoys on the other. He pokes holes in the pretensions on either side. Jane Austen features frequently.

Gauld’s figures are usually blocky stick figures without complete facial features (or books or ghosts), and he often makes use of multiple choice and choose your own adventure structures. Elsewhere he plays around with book titles and typical plots, or stages mild-mannered arguments between authors and their editors or publicists, who generally have quite different notions of quality and marketability.

Lest you dismiss cartoons as being out of touch, the effect of the pandemic on bookshops, libraries and literary events is mentioned a few times. Librarians are depicted as old-time gangsters peddling books while their buildings are closed: “Overdue books are dealt with swiftly and mercilessly” it reads under a panel of a fedora-wearing, revolver-toting figure warning, “The boss says if you ain’t finished ‘The Mirror and the Light’ by tomorrow, it’s curtains!”

Some more favourite lines:

- “1903: Henry James writes a sentence so long and circuitous that he becomes lost inside it for three days.”

- (says one pigeon to another) “I’ve become a psychogeographer. It’s mainly walking around disapproving of gentrification.”

- “A horrible feeling crept over Elaine that perhaps the problems with her novel couldn’t be overcome by changing the font.”

Two spreads that are too good not to share in full (I feel seen!):

And would you look at this attention to detail on the inside cover!

This is destined for many a book-lover’s Christmas stocking.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

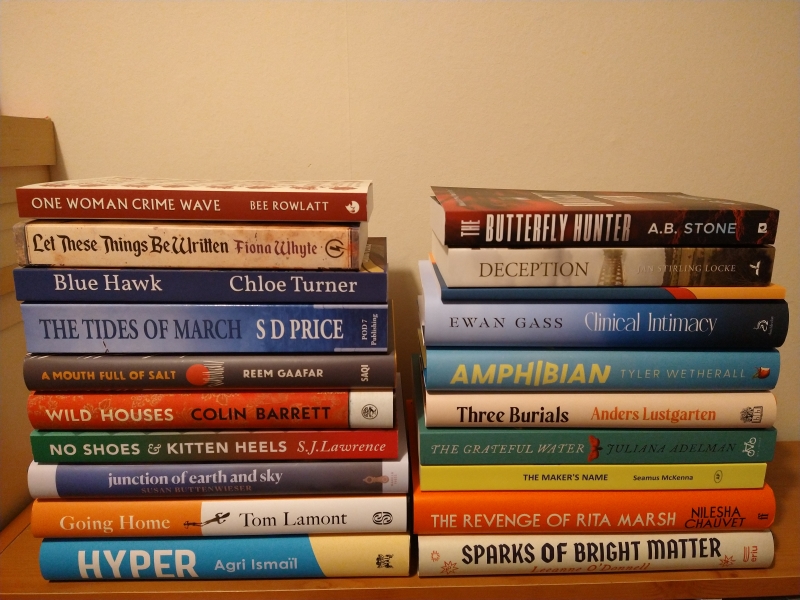

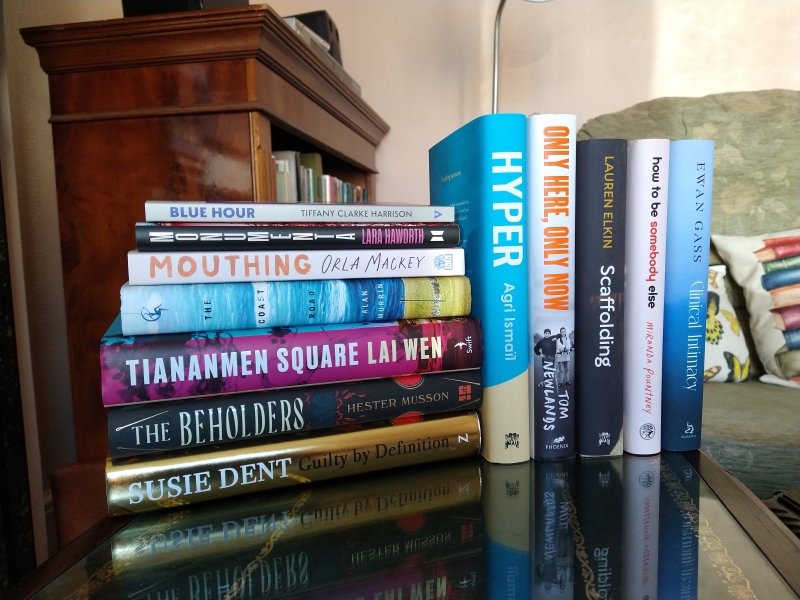

Etymology and Shakespeare studies are the keys to solving a cold case in Susie Dent’s clever, engrossing mystery, Guilty by Definition.

Etymology and Shakespeare studies are the keys to solving a cold case in Susie Dent’s clever, engrossing mystery, Guilty by Definition. Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in Lauren Elkin’s Scaffolding. As history repeats itself one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down.

Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in Lauren Elkin’s Scaffolding. As history repeats itself one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down. Clinical Intimacy’s mysterious antihero comes to life through interviews with his family, friends and clients. The brilliant oral history format builds a picture of isolation among vulnerable populations, only alleviated by care and touch—especially during Covid-19. Ewan Gass’s intricate story reminds us of the ultimate unknowability of other people.

Clinical Intimacy’s mysterious antihero comes to life through interviews with his family, friends and clients. The brilliant oral history format builds a picture of isolation among vulnerable populations, only alleviated by care and touch—especially during Covid-19. Ewan Gass’s intricate story reminds us of the ultimate unknowability of other people.

Only Here, Only Now is bursting with vitality. With her broken heart and fizzing brain, Cora Mowat vows to escape her grim Fife town. Tom Newlands’s evocation of the 1990s—and of his teenage narrator—is utterly convincing. Soaring above grief, poverty, and substance abuse, Cora’s voice is pure magic.

Only Here, Only Now is bursting with vitality. With her broken heart and fizzing brain, Cora Mowat vows to escape her grim Fife town. Tom Newlands’s evocation of the 1990s—and of his teenage narrator—is utterly convincing. Soaring above grief, poverty, and substance abuse, Cora’s voice is pure magic.

Hyper by Agri Ismaïl [I longlisted it – and then shortlisted it – but was outvoted]

Hyper by Agri Ismaïl [I longlisted it – and then shortlisted it – but was outvoted] How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney [It had two votes to make the shortlist, but because it was so similar to Scaffolding in its basics (a thirtysomething woman in a big city, the question of motherhood, and pregnancy loss) we decided to cut it.]

How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney [It had two votes to make the shortlist, but because it was so similar to Scaffolding in its basics (a thirtysomething woman in a big city, the question of motherhood, and pregnancy loss) we decided to cut it.]

In keeping with the title, there are environmentalist considerations and musings on materials, but also the connotation of reusing language or rehashing ideas. I appreciated this strategy when he’s pondering etymology (“Strange noun full of verb, noun / bending to verb, strange / idea of repeating repetition” in the title poem) or reworking proverbs in the hilarious “Poem in Which Is Is Sufficient” (“Sufficient unto the glaze / is the primer thereunder. Sufficient / unto the applecart is the upset / thereof” and so on) but perhaps less so during 22 indulgent pages of epigraphs. The distance-designated poems of the inventive “Solvitur Ambulando” section range from history to science fiction: “Abstracted, ankle deep in the proto-gutters of Elizabethan London: / how were you ejected from your life to wash up here?”

In keeping with the title, there are environmentalist considerations and musings on materials, but also the connotation of reusing language or rehashing ideas. I appreciated this strategy when he’s pondering etymology (“Strange noun full of verb, noun / bending to verb, strange / idea of repeating repetition” in the title poem) or reworking proverbs in the hilarious “Poem in Which Is Is Sufficient” (“Sufficient unto the glaze / is the primer thereunder. Sufficient / unto the applecart is the upset / thereof” and so on) but perhaps less so during 22 indulgent pages of epigraphs. The distance-designated poems of the inventive “Solvitur Ambulando” section range from history to science fiction: “Abstracted, ankle deep in the proto-gutters of Elizabethan London: / how were you ejected from your life to wash up here?” Curtis’s four poems are, together, the strongest entry. I particularly loved the final lines of “September Birth”: “We listen close but cannot fathom / Your new language. We will spend / The rest of our days learning it.” Naomi Booth, too, zeroes in on language in “What is tsunami?” A daughter’s acquisition of language provides entertainment (“She names her favourite doll, Hearty Campfire”) but also induces apprehension:

Curtis’s four poems are, together, the strongest entry. I particularly loved the final lines of “September Birth”: “We listen close but cannot fathom / Your new language. We will spend / The rest of our days learning it.” Naomi Booth, too, zeroes in on language in “What is tsunami?” A daughter’s acquisition of language provides entertainment (“She names her favourite doll, Hearty Campfire”) but also induces apprehension: Rebecca Goss’s fourth poetry collection arises from a rural upbringing in Suffolk. Her parents’ farm was a “[s]emi-derelict, ramshackle whimsy of a place”. There’s nostalgia for the countryside left behind and for a less complicated family life before divorce, yet this is no carefree pastoral. From the omnipresent threats to girls to the challenges of motherhood, Goss is awake to the ways in which women are compelled to adapt to life in male spheres. The title/cover image has multiple connotations: the first bond between mother and child; the gates and doors that showcase craftsmanship (as in “Blacksmith, Making”) or seek to shut menacing forces out (see “The Hounds”), but cannot ensure safety.

Rebecca Goss’s fourth poetry collection arises from a rural upbringing in Suffolk. Her parents’ farm was a “[s]emi-derelict, ramshackle whimsy of a place”. There’s nostalgia for the countryside left behind and for a less complicated family life before divorce, yet this is no carefree pastoral. From the omnipresent threats to girls to the challenges of motherhood, Goss is awake to the ways in which women are compelled to adapt to life in male spheres. The title/cover image has multiple connotations: the first bond between mother and child; the gates and doors that showcase craftsmanship (as in “Blacksmith, Making”) or seek to shut menacing forces out (see “The Hounds”), but cannot ensure safety.

The love and appreciation of natural beauty starts at home, and we are lucky here in West Berkshire to have a very good newspaper that still hosts a nature column (currently by beloved local author Nicola Chester). This collection of Newbury Weekly News articles spans 1979 to 1996, with the majority of the pieces from 1990–5. They were contributed by 17 authors, but most are by Lew Lewis (including under a pseudonym).

The love and appreciation of natural beauty starts at home, and we are lucky here in West Berkshire to have a very good newspaper that still hosts a nature column (currently by beloved local author Nicola Chester). This collection of Newbury Weekly News articles spans 1979 to 1996, with the majority of the pieces from 1990–5. They were contributed by 17 authors, but most are by Lew Lewis (including under a pseudonym). Rookie: Selected Poems by Caroline Bird (2022)

Rookie: Selected Poems by Caroline Bird (2022) Given my love of medical memoirs and my recent obsession with

Given my love of medical memoirs and my recent obsession with  It’s one minute to midnight in London. Two Brown sisters are awake and looking at the moon. A journey of the imagination takes them through the time zones to see the natural spectacles the world has to offer: polar bears hunting at the Arctic Circle, baby turtles scrambling for the sea on an Indian beach, humpback whales breaching in Hawaii, and much more. Each spread has no more than two short paragraphs of text to introduce the landscape and fauna and explain the threats each ecosystem faces due to human influence. As the girls return to London and the clock chimes to welcome in 22 April, Earth Day, the author invites us to feel kinship with the creatures pictured: “They’re part of us, and every breath we take. Our world is fragile and threatened – but still lovely. And now it’s the start of a new day: a day when I’ll speak about these wonders, shout them out”.

It’s one minute to midnight in London. Two Brown sisters are awake and looking at the moon. A journey of the imagination takes them through the time zones to see the natural spectacles the world has to offer: polar bears hunting at the Arctic Circle, baby turtles scrambling for the sea on an Indian beach, humpback whales breaching in Hawaii, and much more. Each spread has no more than two short paragraphs of text to introduce the landscape and fauna and explain the threats each ecosystem faces due to human influence. As the girls return to London and the clock chimes to welcome in 22 April, Earth Day, the author invites us to feel kinship with the creatures pictured: “They’re part of us, and every breath we take. Our world is fragile and threatened – but still lovely. And now it’s the start of a new day: a day when I’ll speak about these wonders, shout them out”.

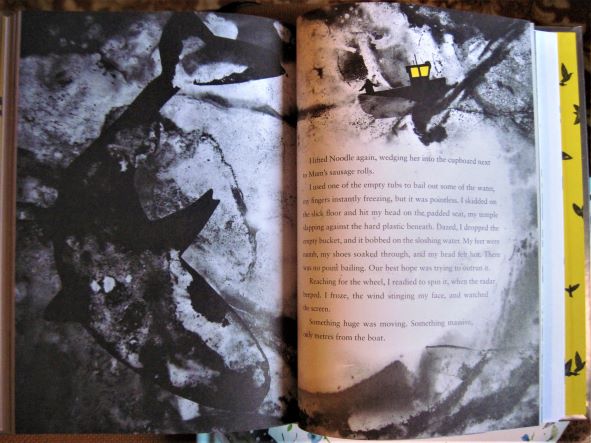

I could never have predicted when I read The Way Past Winter that Hargrave would become one of my favourite contemporary writers. Julia and her parents (and not forgetting the cat, Noodle) are off on an island adventure to Unst, in the north of Shetland, where her father will keep the lighthouse for a summer and her mother, a marine biologist, will search for the Greenland shark, a notably long-lived species she’s researching in hopes of discovering clues to human longevity – a cause close to her heart after her own mother’s death with dementia. Julia makes friends with Kin, a South Asian boy whose family run the island laundromat-cum-library. They watch stars and try to evade local bullies together. But one thing Julia can’t escape is her mother’s mental health struggle (late on named as bipolar: “Mum sometimes bounced around like Tigger, and other times she was mopey like Eeyore”). Julia thinks that if she can find the shark, it might fix her mother.

I could never have predicted when I read The Way Past Winter that Hargrave would become one of my favourite contemporary writers. Julia and her parents (and not forgetting the cat, Noodle) are off on an island adventure to Unst, in the north of Shetland, where her father will keep the lighthouse for a summer and her mother, a marine biologist, will search for the Greenland shark, a notably long-lived species she’s researching in hopes of discovering clues to human longevity – a cause close to her heart after her own mother’s death with dementia. Julia makes friends with Kin, a South Asian boy whose family run the island laundromat-cum-library. They watch stars and try to evade local bullies together. But one thing Julia can’t escape is her mother’s mental health struggle (late on named as bipolar: “Mum sometimes bounced around like Tigger, and other times she was mopey like Eeyore”). Julia thinks that if she can find the shark, it might fix her mother.

“Loving v. Virginia” celebrates interracial love: “Look at us, improper. Look at us, indecent. Look at us, incandescent and loving.” Food is a vehicle for memory, as are home videos. Like Ante, Miller has a poem based on her mother’s voicemail messages. “Glitch honorifics” gives the characters for different family relationships, comparing Chinese and Hokkien. The imagery is full of colour and light, plants and paintings. A terrific central section called “Bloom” contains 10 jellyfish poems (“We bloom like nuclear hydrangea … I’m an unwound chandelier, / a 150-foot-long coil of cilia, // made up of a million gelatinous foxgloves.”).

“Loving v. Virginia” celebrates interracial love: “Look at us, improper. Look at us, indecent. Look at us, incandescent and loving.” Food is a vehicle for memory, as are home videos. Like Ante, Miller has a poem based on her mother’s voicemail messages. “Glitch honorifics” gives the characters for different family relationships, comparing Chinese and Hokkien. The imagery is full of colour and light, plants and paintings. A terrific central section called “Bloom” contains 10 jellyfish poems (“We bloom like nuclear hydrangea … I’m an unwound chandelier, / a 150-foot-long coil of cilia, // made up of a million gelatinous foxgloves.”). Back in 2014, I reviewed Kupersmith’s debut collection, The Frangipani Hotel, for

Back in 2014, I reviewed Kupersmith’s debut collection, The Frangipani Hotel, for

This was on my radar thanks to a starred Kirkus review. It would have been a good choice for the Women’s Prize longlist, with its bold heroine, Latinx and gay characters, and blend of literary and women’s fiction. The Puerto Rican immigrant community and gentrifying neighbourhoods of New York City are appealing locales, and Olga is a clever, gutsy protagonist. As the novel opens in 2017, she’s working out how best to fleece the rich families whose progeny’s weddings she plans. Today it’s embezzling napkins for her cousin Mabel’s wedding. Next: stockpiling cut-price champagne. Olga’s brother Prieto, a slick congressman inevitably nicknamed the “Latino Obama,” is a closeted gay man. Their late father was a drug addict; their mother left to be part of a revolutionary movement back in PR and sends her children occasional chiding letters when they appear to be selling out.

This was on my radar thanks to a starred Kirkus review. It would have been a good choice for the Women’s Prize longlist, with its bold heroine, Latinx and gay characters, and blend of literary and women’s fiction. The Puerto Rican immigrant community and gentrifying neighbourhoods of New York City are appealing locales, and Olga is a clever, gutsy protagonist. As the novel opens in 2017, she’s working out how best to fleece the rich families whose progeny’s weddings she plans. Today it’s embezzling napkins for her cousin Mabel’s wedding. Next: stockpiling cut-price champagne. Olga’s brother Prieto, a slick congressman inevitably nicknamed the “Latino Obama,” is a closeted gay man. Their late father was a drug addict; their mother left to be part of a revolutionary movement back in PR and sends her children occasional chiding letters when they appear to be selling out.