20 Books of Summer, 14–16: Polly Atkin, Nan Shepherd and Susan Allen Toth

I’m still plugging away at the challenge. It’ll be down to the wire, but I should finish and review all 20 books by the 31st! Today I have a chronic illness memoir, a collection of poetry and prose pieces, and a reread of a cosy travel guide.

Some of Us Just Fall: On Nature and Not Getting Better by Polly Atkin (2023)

I was heartened to see this longlisted for the Wainwright Prize. It was a perfect opportunity to recognize the disabled/chronically ill experience of nature and the book achieves just what the award has recognised in recent years: the braiding together of life writing and place-based observation. (Wainwright has also done a great job on diversity this year: there are three books by BIPOC and five by women on the nature writing shortlist alone.)

Polly Atkin knew something was different about her body from a young age. She broke bones all the time, her first at 18 months when her older brother ran into her on his bicycle. But it wasn’t until her thirties that she knew what was wrong – Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and haemochromatosis – and developed strategies to mitigate the daily pain and the drains on her energy and mobility. “Correct diagnosis makes lives bearable,” she writes. “It gives you access to the right treatment. It gives you agency.”

Polly Atkin knew something was different about her body from a young age. She broke bones all the time, her first at 18 months when her older brother ran into her on his bicycle. But it wasn’t until her thirties that she knew what was wrong – Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and haemochromatosis – and developed strategies to mitigate the daily pain and the drains on her energy and mobility. “Correct diagnosis makes lives bearable,” she writes. “It gives you access to the right treatment. It gives you agency.”

The book assembles long-ish fragments, snippets from different points of her past alternating with what she sees on rambles near her home in Grasmere. She writes in some depth about Lake District literature: Thomas De Quincey as well as the Wordsworths – Atkin’s previous book is a biography of Dorothy Wordsworth that spotlights her experience with illness. In describing the desperately polluted state of Windermere, Atkin draws parallels with her condition (“Now I recognise my body as a precarious ecosystem”). Although she spurns the notion of the “Nature Cure,” swimming is a valuable therapy for her.

Theme justifies form here: “This is the chronic life, lived as repetition and variance, as sedimentation of broken moments, not as a linear progression.” For me, there was a bit too much particularity; if you don’t connect to the points of reference, there’s no way in and the danger arises of it all feeling indulgent. Besides, by the time I opened this I’d already read two Ehlers-Danlos memoirs (All My Wild Mothers by Victoria Bennett and Floppy by Alyssa Graybeal) and another reference soon came my way in The Invisible Kingdom by Meghan O’Rourke. So overfamiliarity was a problem. And by the time I forced myself to pick this off of my set-aside shelf and finish it, I’d read Nina Lohman’s stellar The Body Alone. For those newer to reading about chronic illness, though, especially if you also have an interest in the Lakes, it could be an eye-opener.

With thanks to Sceptre (Hodder) for the free copy for review.

Selected Prose & Poetry by Nan Shepherd (2023)

I’d read and enjoyed Shepherd’s The Living Mountain, which has surged in popularity as an early modern nature writing classic thanks to Robert Macfarlane et al. I’m not sure I’d go as far as the executor of the Nan Shepherd Estate, though, who describes her in the Preface as “Taylor Swift in hiking boots.” The pieces reprinted here are from her one published book of poems, In the Cairngorms, and the mixed-genre collection Wild Geese. There is also a 28-page “novella,” Descent from the Cross. After World War I, Elizabeth, a workers’ rights organiser for a paper mill, marries a shell-shocked veteran who wants to write a book but isn’t sure he has either the genius or the dedication. It’s interesting that Shepherd would write about a situation where the wife has the economic upper hand, but the tragedy of the sickly failed author put me in mind of George Gissing or D.H. Lawrence, so didn’t feel fresh. Going by length alone, I would have called this a short story, but I understand why it would be designated a novella, for the scope.

I’d read and enjoyed Shepherd’s The Living Mountain, which has surged in popularity as an early modern nature writing classic thanks to Robert Macfarlane et al. I’m not sure I’d go as far as the executor of the Nan Shepherd Estate, though, who describes her in the Preface as “Taylor Swift in hiking boots.” The pieces reprinted here are from her one published book of poems, In the Cairngorms, and the mixed-genre collection Wild Geese. There is also a 28-page “novella,” Descent from the Cross. After World War I, Elizabeth, a workers’ rights organiser for a paper mill, marries a shell-shocked veteran who wants to write a book but isn’t sure he has either the genius or the dedication. It’s interesting that Shepherd would write about a situation where the wife has the economic upper hand, but the tragedy of the sickly failed author put me in mind of George Gissing or D.H. Lawrence, so didn’t feel fresh. Going by length alone, I would have called this a short story, but I understand why it would be designated a novella, for the scope.

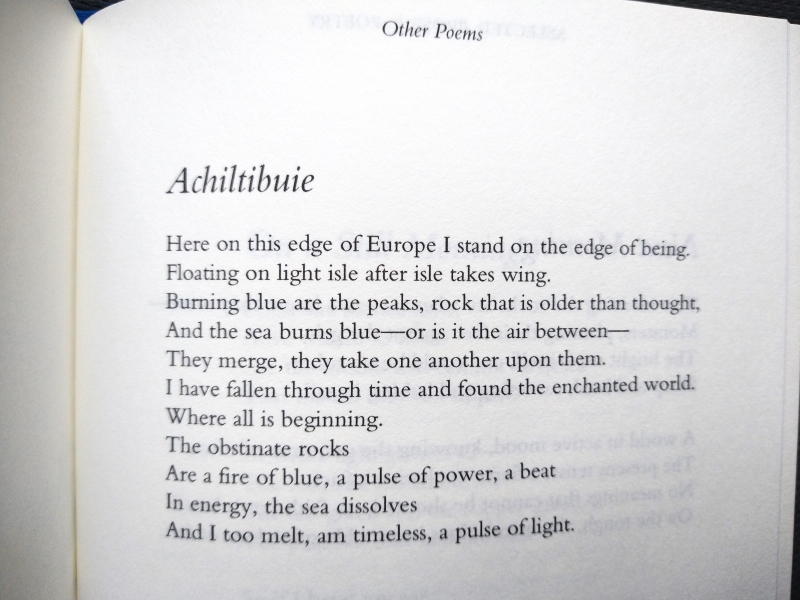

None of the miniature essays – field observations and character studies – stood out to me. About half of the book is given over to poetry. As with the nature writing, there is a feeling of mountain desolation. There are a lot of religious references and hints of the mystical, as in “The Bush,” which opens “In that pure ecstasy of light / The bush is burning bright. / Its substance is consumed away / And only form doth stay”. It’s a mixed bag: some feels very old-fashioned and sentimental, with every other line or, worse, every line rhyming, and some archaic wording and rather impenetrable Scots dialect. It could have been written 100 years before, by Robert Burns if not William Blake. But every so often there is a flash of brilliance. “Blackbird in Snow” is quite a nice one, and reminiscent of Thomas Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush.” I even found the cryptic lines from “Real Presence” that inspired a song on David Gray’s Skellig. My favourite poem by far was:

Overall, this didn’t engage me; it’s only for Shepherd fanatics and completists. (Won from Galileo Publishers in a Twitter giveaway)

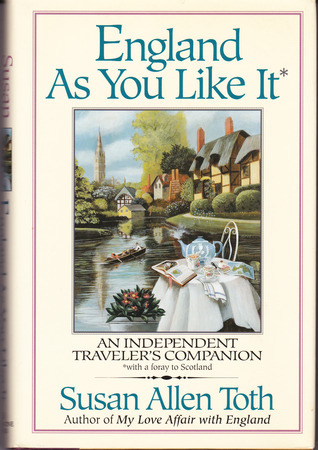

England As You Like It: An Independent Traveler’s Companion by Susan Allen Toth (1995)

A reread. As I was getting ready to go overseas for the first time in the summer of 2003, Toth’s trilogy of memoirs whetted my appetite for travel in Britain. (They’re on my Landmark Books in My Life, Part II list.) This is the middle book and probably the least interesting in that it mostly recounts stays in particular favourite locations, such as Dorset, the Highlands, and various sites in Cornwall. However, I’ve never forgotten her “thumbprint theory,” which means staying a week or more in an area no larger than her thumb covers on a large-scale map, driving an hour or less for day trips. Not for her those cram-it-all-in trips where you race through multiple countries in a week (I have American friends who did Paris, London and Rome within six days, or five countries in eight days; blame it on stingy vacation policies, I guess). Instead, she wants to really bed into one place and have the time to make serendipitous discoveries such as an obscure museum or a rare opening of a private garden.

A reread. As I was getting ready to go overseas for the first time in the summer of 2003, Toth’s trilogy of memoirs whetted my appetite for travel in Britain. (They’re on my Landmark Books in My Life, Part II list.) This is the middle book and probably the least interesting in that it mostly recounts stays in particular favourite locations, such as Dorset, the Highlands, and various sites in Cornwall. However, I’ve never forgotten her “thumbprint theory,” which means staying a week or more in an area no larger than her thumb covers on a large-scale map, driving an hour or less for day trips. Not for her those cram-it-all-in trips where you race through multiple countries in a week (I have American friends who did Paris, London and Rome within six days, or five countries in eight days; blame it on stingy vacation policies, I guess). Instead, she wants to really bed into one place and have the time to make serendipitous discoveries such as an obscure museum or a rare opening of a private garden.

I most liked the early general chapters about how to make air travel bearable, her obsession with maps, her preference for self-catering, and her tendency to take home edible souvenirs. Of course, all the “Floating Facts” are hopelessly out-of-date. This being the early to mid-1990s, she had to order paper catalogues to browse cottage options (I still did this for honeymoon prep in 2006–7) and make international phone calls to book accommodation. She recommends renting somewhere from the National Trust or Landmark Trust. Ordnance Survey maps could be special ordered from the British Travel Bookshop in New York City. Entry fees averaged a few pounds. It’s all so quaint! An Anglo-American time capsule of sorts. I’ve always sensed a kindred spirit in Toth, and those whose taste runs toward the old-fashioned will probably also find her a charming tour guide. I’ve also reviewed the third book, England for All Seasons. (Free from The Book Thing of Baltimore)

Three “Love” or “Heart” Books for Valentine’s Day: Ephron, Lischer and Nin

Every year I say I’m really not a Valentine’s Day person and yet put together a themed post featuring books that have “Love” or a similar word in the title. This is the eighth year in a row, in fact (after 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2023)! Today I’m looking at two classic novellas, one of them a reread and the other my first taste of a writer I’d expected more from; and a wrenching, theologically oriented bereavement memoir.

Heartburn by Nora Ephron (1983)

I’d already pulled this out for my planned reread of books published in my birth year, so it’s pleasing that it can do double duty here. I can’t say it better than my original 2013 review:

The funniest book you’ll ever read about heartbreak and betrayal, this is full of wry observations about the compromises we make to marry – and then stay married to – people who are very different from us. Ephron readily admitted that her novel is more than a little autobiographical: it’s based on the breakdown of her second marriage to investigative journalist Carl Bernstein (All the President’s Men), who had an affair with a ludicrously tall woman – one element she transferred directly into Heartburn.

Ephron’s fictional counterpart is Rachel Samstad, a New Yorker who writes cookbooks or, rather, memoirs with recipes – before that genre really took off. Seven months pregnant with her second child, she has just learned that her second husband is having an affair. What follows is her uproarious memories of life, love and failed marriages. Indeed, as Ephron reflected in a 2004 introduction, “One of the things I’m proudest of is that I managed to convert an event that seemed to me hideously tragic at the time to a comedy – and if that’s not fiction, I don’t know what is.”

As one might expect from a screenwriter, there is a cinematic – that is, vivid but not-quite-believable – quality to some of the moments: the armed robbery of Rachel’s therapy group, her accidentally flinging an onion into the audience during a cooking demonstration, her triumphant throw of a key lime pie into her husband’s face in the final scene. And yet Ephron was again drawing on experience: a friend’s therapy group was robbed at gunpoint, and she’d always filed the experience away in a mental drawer marked “Use This Someday” – “My mother taught me many things when I was growing up, but the main thing I learned from her is that everything is copy.” This is one of celebrity chef Nigella Lawson’s favorite books ever, for its mixture of recipes and rue, comfort food and folly. It’s a quick read, but a substantial feast for the emotions.

Sometimes I wonder why I bother when I can’t improve on reviews I wrote over a decade ago (see also another upcoming reread). What I would add now, without disputing any of the above, is that there’s more bitterness to the tone than I’d recalled, even though Ephron does, yes, play it for laughs. But also, some of the humour hasn’t aged well, especially where based on race/culture or sexuality. I’d forgotten that Rachel’s husband isn’t the only cheater here; pretty much every couple mentioned is currently working through the aftermath of an affair or has survived one in the past. In one of these, the wife who left for a woman is described not as a lesbian but by another word, each time, which felt unkind rather than funny.

Sometimes I wonder why I bother when I can’t improve on reviews I wrote over a decade ago (see also another upcoming reread). What I would add now, without disputing any of the above, is that there’s more bitterness to the tone than I’d recalled, even though Ephron does, yes, play it for laughs. But also, some of the humour hasn’t aged well, especially where based on race/culture or sexuality. I’d forgotten that Rachel’s husband isn’t the only cheater here; pretty much every couple mentioned is currently working through the aftermath of an affair or has survived one in the past. In one of these, the wife who left for a woman is described not as a lesbian but by another word, each time, which felt unkind rather than funny.

Still, the dialogue, the scenes, the snarky self-portrayal: it all pops. This was autofiction before that was a thing, but anyone working in any genre could learn how to write readable content by studying Ephron. “‘I don’t have to make everything into a joke,’ I said. ‘I have to make everything into a story.’ … I think you often have that sense when you write – that if you can spot something in yourself and set it down on paper, you’re free of it. And you’re not, of course; you’ve just managed to set it down on paper, that’s all.” (Little Free Library)

My original rating (2013):

My rating now:

Stations of the Heart: Parting with a Son by Richard Lischer (2013)

“What we had taken to be a temporary unpleasantness had now burrowed deep into the family pulp and was gnawing us from the inside out.” Like all life writing, the bereavement memoir has two tasks: to bear witness and to make meaning. From a distance that just happens to be Mary Karr’s prescribed seven years, Lischer opens by looking back on the day when his 33-year-old son Adam called to tell him that his melanoma, successfully treated the year before, was back. Tests revealed that the cancer’s metastases were everywhere, including in his brain, and were “innumerable,” a word that haunted Lischer and his wife, their daughter, and Adam’s wife, who was pregnant with their first child.

The next few months were a Calvary of sorts, and Lischer, an emeritus professor at Duke Divinity School, draws deliberate parallels with the biblical and liturgical preparations for Good Friday that feel appropriate for this Ash Wednesday. Lischer had no problem with Adam’s late-life conversion from Protestantism to Catholicism, whose rites he followed with great piety in his final summer. He traces Adam and Jenny’s daily routines as well as his own helpless attendance at hospital appointments. Doped up on painkillers, Adam attended one last Father’s Day baseball game with him; one last Fourth of July picnic. Everyone so desperately wanted him to keep going long enough to meet his baby girl. To think that she is now a young woman and has opened all the presents Adam bought to leave behind for her first 18 birthdays.

The next few months were a Calvary of sorts, and Lischer, an emeritus professor at Duke Divinity School, draws deliberate parallels with the biblical and liturgical preparations for Good Friday that feel appropriate for this Ash Wednesday. Lischer had no problem with Adam’s late-life conversion from Protestantism to Catholicism, whose rites he followed with great piety in his final summer. He traces Adam and Jenny’s daily routines as well as his own helpless attendance at hospital appointments. Doped up on painkillers, Adam attended one last Father’s Day baseball game with him; one last Fourth of July picnic. Everyone so desperately wanted him to keep going long enough to meet his baby girl. To think that she is now a young woman and has opened all the presents Adam bought to leave behind for her first 18 birthdays.

The facts of the story are heartbreaking enough, but Lischer’s prose is a perfect match: stately, resolute and weighted with spiritual allusion, yet never morose. He approaches the documenting of his son’s too-short life with a sense of sacred duty: “I have acquired a new responsibility: I have become the interpreter of his death. God, I must do a better job. … I kissed his head and thanked him for being my son. I promised him then that his death would not ruin my life.” This memoir brought back so much about my brother-in-law’s death from brain cancer in 2015, from the “TEAM [ADAM/GARNET]” T-shirts to Adam’s sister’s remark, “I never dreamed this would be our family’s story.” We’re not alone. (Remainder book from the Bowie, Maryland Dollar Tree)

A Spy in the House of Love by Anaïs Nin (1954)

I’d heard Nin spoken of in the same breath as D.H. Lawrence, so thought I might similarly appreciate her because of, or despite, comically overblown symbolism around sex. I think I was also expecting something more titillating? (I guess I had this confused for Delta of Venus, her only work that would be shelved in an Erotica section.) Many have tried to make a feminist case for this novella about Sabina, an early liberated woman in New York City who has extramarital sex with four other men who appeal to her for various not particularly good reasons (the traumatized soldier whom she comforts like a mother; the exotic African drummer – “Sabina did not feel guilty for drinking of the tropics through Mambo’s body”). She herself states, “I want to trespass boundaries, erase all identifications, anything which fixes one permanently into one mould, one place without hope of change.” The most interesting aspect of the book was Sabina’s questioning of whether she inherited her promiscuity from her father (it’s tempting to read this autobiographically as Nin’s own father left the family for another woman, a foundational wound in her life).

I’d heard Nin spoken of in the same breath as D.H. Lawrence, so thought I might similarly appreciate her because of, or despite, comically overblown symbolism around sex. I think I was also expecting something more titillating? (I guess I had this confused for Delta of Venus, her only work that would be shelved in an Erotica section.) Many have tried to make a feminist case for this novella about Sabina, an early liberated woman in New York City who has extramarital sex with four other men who appeal to her for various not particularly good reasons (the traumatized soldier whom she comforts like a mother; the exotic African drummer – “Sabina did not feel guilty for drinking of the tropics through Mambo’s body”). She herself states, “I want to trespass boundaries, erase all identifications, anything which fixes one permanently into one mould, one place without hope of change.” The most interesting aspect of the book was Sabina’s questioning of whether she inherited her promiscuity from her father (it’s tempting to read this autobiographically as Nin’s own father left the family for another woman, a foundational wound in her life).

Come on, though, “fecundated,” “fecundation” … who could take such vocabulary seriously? Or this sex writing (snort!): “only one ritual, a joyous, joyous, joyous impaling of woman on a man’s sensual mast.” I charge you to use the term “sensual mast” wherever possible in the future. (Secondhand – Oxfam, Newbury)

But hey, check out my score for the Faber Valentine’s quiz!

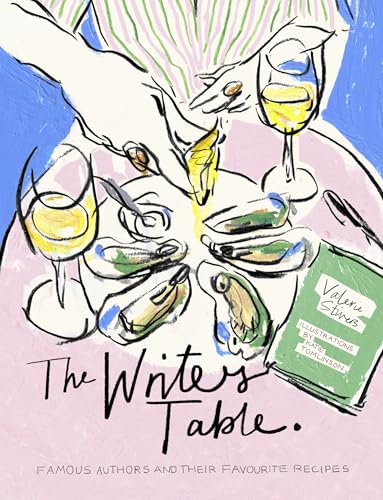

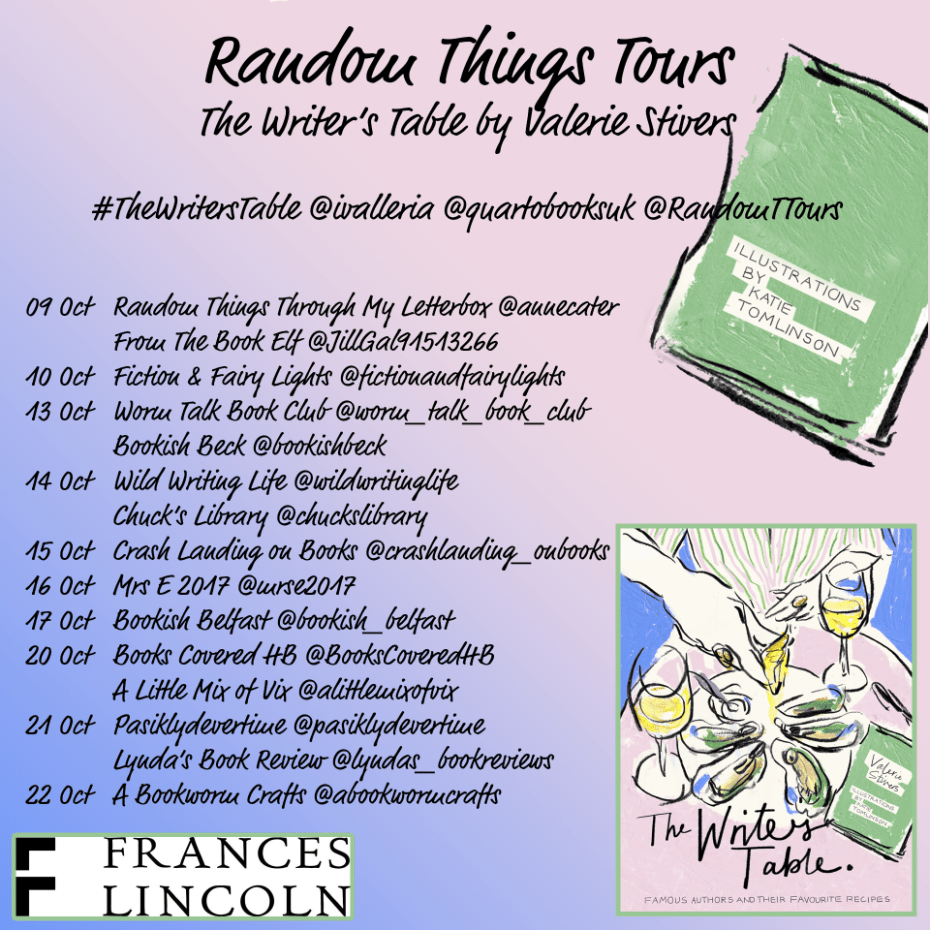

Though I’ve read a lot by and about D.H. Lawrence, I didn’t realise he did all the cooking in his household with Frieda, and was renowned for his bread. And who knew that Emily Dickinson was better known in her lifetime as a baker? Her coconut cake is beautifully simple, containing just six ingredients. Flannery O’Connor’s peppermint chiffon pie also sounds delicious. Some essays do not feature a recipe but a discussion of food in an author’s work, such as the unusual combinations of mostly tinned foods that Iris Murdoch’s characters eat. It turns out that that’s how she and her husband John Bayley ate, so she saw nothing odd about it. And Murakami’s 2005 New Yorker story “The Year of Spaghetti” is about a character whose fixation on one foodstuff reflects, Stivers notes, his “emotional … turmoil.”

Though I’ve read a lot by and about D.H. Lawrence, I didn’t realise he did all the cooking in his household with Frieda, and was renowned for his bread. And who knew that Emily Dickinson was better known in her lifetime as a baker? Her coconut cake is beautifully simple, containing just six ingredients. Flannery O’Connor’s peppermint chiffon pie also sounds delicious. Some essays do not feature a recipe but a discussion of food in an author’s work, such as the unusual combinations of mostly tinned foods that Iris Murdoch’s characters eat. It turns out that that’s how she and her husband John Bayley ate, so she saw nothing odd about it. And Murakami’s 2005 New Yorker story “The Year of Spaghetti” is about a character whose fixation on one foodstuff reflects, Stivers notes, his “emotional … turmoil.”

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris: This debut collection addresses the symptoms and side effects of breast cancer treatment at age 36, but often in oblique or cheeky ways – it can be no mistake that “assistance” appears two lines before a mention of hemorrhoids, for instance, even though it closes an epithalamium distinguished by its gentle sibilance (Farris’s husband is Ukrainian American poet Ilya Kaminsky.) She crafts sensual love poems, and exhibits Japanese influences. (Discussed in my

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris: This debut collection addresses the symptoms and side effects of breast cancer treatment at age 36, but often in oblique or cheeky ways – it can be no mistake that “assistance” appears two lines before a mention of hemorrhoids, for instance, even though it closes an epithalamium distinguished by its gentle sibilance (Farris’s husband is Ukrainian American poet Ilya Kaminsky.) She crafts sensual love poems, and exhibits Japanese influences. (Discussed in my

Hard Drive by Paul Stephenson: This wry, wrenching debut collection is an extended elegy for his partner, Tod Hartman, an American anthropologist who died of heart failure at 38. There’s every style, tone and structure imaginable here. Stephenson riffs on his partner’s oft-misspelled name (German for death), and writes of discovery, autopsy, sadmin and rituals. In “The Only Book I Took” he opens up Tod’s copy of Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking – which came from Wonder Book, the bookstore chain I worked at in Maryland!

Hard Drive by Paul Stephenson: This wry, wrenching debut collection is an extended elegy for his partner, Tod Hartman, an American anthropologist who died of heart failure at 38. There’s every style, tone and structure imaginable here. Stephenson riffs on his partner’s oft-misspelled name (German for death), and writes of discovery, autopsy, sadmin and rituals. In “The Only Book I Took” he opens up Tod’s copy of Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking – which came from Wonder Book, the bookstore chain I worked at in Maryland!

Anyway, it was nice to see this book out and about in the world, and it reminded me to belatedly pick up my review copy once I got back. As a bereavement memoir, the book is right in my wheelhouse, though I’ve tended to gravitate towards stories of the loss of a family memoir or spouse, whereas Carson is commemorating her best friend, Larissa, who died in 2018 of a heroin overdose, age 32, and was found in the bath in her Paris flat one week later.

Anyway, it was nice to see this book out and about in the world, and it reminded me to belatedly pick up my review copy once I got back. As a bereavement memoir, the book is right in my wheelhouse, though I’ve tended to gravitate towards stories of the loss of a family memoir or spouse, whereas Carson is commemorating her best friend, Larissa, who died in 2018 of a heroin overdose, age 32, and was found in the bath in her Paris flat one week later. Dixon was a new name for me, but the South African poet, now based in Cambridge, has published five collections. I was drawn to this latest one by its acknowledged debt to D.H. Lawrence: the title phrase comes from one of his essays, and the book as a whole is said to resemble his Birds, Beasts and Flowers, which is in its centenary year. I’m more familiar with Lawrence’s novels than his verse, but I do own his Collected Poems and was fascinated to find here echoes of his mystical interest in nature as well as his love for the landscape of New Mexico. England and South Africa are settings as well as the American Southwest.

Dixon was a new name for me, but the South African poet, now based in Cambridge, has published five collections. I was drawn to this latest one by its acknowledged debt to D.H. Lawrence: the title phrase comes from one of his essays, and the book as a whole is said to resemble his Birds, Beasts and Flowers, which is in its centenary year. I’m more familiar with Lawrence’s novels than his verse, but I do own his Collected Poems and was fascinated to find here echoes of his mystical interest in nature as well as his love for the landscape of New Mexico. England and South Africa are settings as well as the American Southwest. But first to address the central question: Part One is No and Part Two is Yes; each is allotted 10 chapters and roughly the same number of pages. McLaren has absolute sympathy with those who decide that they cannot in good conscience call themselves Christians. He’s not coming up with easily refuted objections, straw men, but honestly facing huge and ongoing problems like patriarchal and colonial attitudes, the condoning of violence, intellectual stagnation, ageing congregations, and corruption. From his vantage point as a former pastor, he acknowledges that today’s churches, especially of the American megachurch variety, feature significant conflicts of interest around money. He knows that Christians can be politically and morally repugnant and can oppose the very changes the world needs.

But first to address the central question: Part One is No and Part Two is Yes; each is allotted 10 chapters and roughly the same number of pages. McLaren has absolute sympathy with those who decide that they cannot in good conscience call themselves Christians. He’s not coming up with easily refuted objections, straw men, but honestly facing huge and ongoing problems like patriarchal and colonial attitudes, the condoning of violence, intellectual stagnation, ageing congregations, and corruption. From his vantage point as a former pastor, he acknowledges that today’s churches, especially of the American megachurch variety, feature significant conflicts of interest around money. He knows that Christians can be politically and morally repugnant and can oppose the very changes the world needs. Many of these early notes question the purpose of reliving racial violence. For instance, Sharpe is appalled to watch a Claudia Rankine video essay that stitches together footage of beatings and murders of Black people. “Spectacle is not repair.” She later takes issue with Barack Obama singing “Amazing Grace” at the funeral of slain African American churchgoers because the song was written by a slaver. The general message I take from these instances is that one’s intentions do not matter; commemorating violence against Black people to pull at the heartstrings is not just in poor taste, but perpetuates cycles of damage.

Many of these early notes question the purpose of reliving racial violence. For instance, Sharpe is appalled to watch a Claudia Rankine video essay that stitches together footage of beatings and murders of Black people. “Spectacle is not repair.” She later takes issue with Barack Obama singing “Amazing Grace” at the funeral of slain African American churchgoers because the song was written by a slaver. The general message I take from these instances is that one’s intentions do not matter; commemorating violence against Black people to pull at the heartstrings is not just in poor taste, but perpetuates cycles of damage.

D.H. Lawrence: 9+ (Aaron’s Rod, Kangaroo, The Lost Girl, The Plumed Serpent, a Complete Poems volume, Sea and Sardinia, a Selected Short Stories volume, Studies in Classic American Literature, The Woman Who Rode Away)

D.H. Lawrence: 9+ (Aaron’s Rod, Kangaroo, The Lost Girl, The Plumed Serpent, a Complete Poems volume, Sea and Sardinia, a Selected Short Stories volume, Studies in Classic American Literature, The Woman Who Rode Away) T.C. Boyle: 7 (A Friend of the Earth, The Inner Circle, Riven Rock, The Tortilla Curtain, Water Music, The Women, World’s End)

T.C. Boyle: 7 (A Friend of the Earth, The Inner Circle, Riven Rock, The Tortilla Curtain, Water Music, The Women, World’s End) W. Somerset Maugham: 7 (Ashenden, Christmas Holiday, Creatures of Circumstance, Liza of Lambeth, The Magician, The Razor’s Edge, The Summing Up)

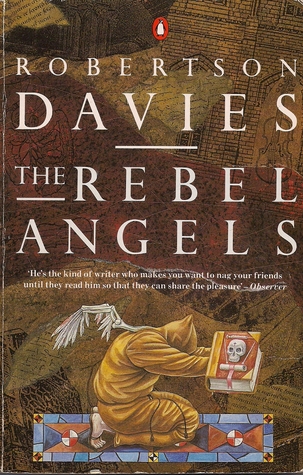

W. Somerset Maugham: 7 (Ashenden, Christmas Holiday, Creatures of Circumstance, Liza of Lambeth, The Magician, The Razor’s Edge, The Summing Up) Robertson Davies: 6.5 (The Salterton Trilogy, The Deptford Trilogy, The Cornish Trilogy)

Robertson Davies: 6.5 (The Salterton Trilogy, The Deptford Trilogy, The Cornish Trilogy) Barbara Comyns: 5 (The Juniper Tree, The House of Dolls, Mr Fox, The Skin Chairs, A Touch of Mistletoe)

Barbara Comyns: 5 (The Juniper Tree, The House of Dolls, Mr Fox, The Skin Chairs, A Touch of Mistletoe)

Wendy Perriam: 5 (Absinthe for Elevenses, Breaking and Entering, Cuckoo, Michael, Michael, Sin City)

Wendy Perriam: 5 (Absinthe for Elevenses, Breaking and Entering, Cuckoo, Michael, Michael, Sin City) Richard Mabey: 4 (The Common Ground, Gilbert White biography, Nature Cure, The Unofficial Countryside)

Richard Mabey: 4 (The Common Ground, Gilbert White biography, Nature Cure, The Unofficial Countryside) Virginia Woolf: 4 (Between the Acts, The Waves, The Years, a volume of her diaries)

Virginia Woolf: 4 (Between the Acts, The Waves, The Years, a volume of her diaries) Kent Haruf: 3 (Plainsong, Eventide, Benediction)

Kent Haruf: 3 (Plainsong, Eventide, Benediction) Elizabeth Jane Howard: 3 (Marking Time, Confusion, Casting Off)

Elizabeth Jane Howard: 3 (Marking Time, Confusion, Casting Off) Mary Karr: 3 (The Liars’ Club, Cherry, Lit)

Mary Karr: 3 (The Liars’ Club, Cherry, Lit) Sue Miller: 3 (The Lake Shore Limited, While I Was Gone, The World Below)

Sue Miller: 3 (The Lake Shore Limited, While I Was Gone, The World Below) Howard Norman: 3 (Devotion, The Northern Lights, What Is Left the Daughter)

Howard Norman: 3 (Devotion, The Northern Lights, What Is Left the Daughter)

#1 One of the books I read ‘in preparation’ for attending that conference was Small World by David Lodge, a comedic novel about professors on the international conference circuit. I’ve included it as one of the

#1 One of the books I read ‘in preparation’ for attending that conference was Small World by David Lodge, a comedic novel about professors on the international conference circuit. I’ve included it as one of the  #2 Flights and “small world” connections also fill the linked short story collection

#2 Flights and “small world” connections also fill the linked short story collection  #3 If you can bear to remember the turbulence of recent history,

#3 If you can bear to remember the turbulence of recent history,  #4 That punning title reminded me of

#4 That punning title reminded me of

Merritt asked about the novel’s magic realist element and how stylistically different his novels have been from each other. He was glad she found the book funny, as “life is tragicomic.” In an effort not to get stuck in a rut, he deliberately ‘breaks the mould’ after each book and starts over. This has not made him popular with his publisher!

Merritt asked about the novel’s magic realist element and how stylistically different his novels have been from each other. He was glad she found the book funny, as “life is tragicomic.” In an effort not to get stuck in a rut, he deliberately ‘breaks the mould’ after each book and starts over. This has not made him popular with his publisher!

Last year’s Dylan Thomas Prize winner interviewed this year’s winner, and it was clear that the mutual admiration was strong. Though I had mixed feelings about Luster (

Last year’s Dylan Thomas Prize winner interviewed this year’s winner, and it was clear that the mutual admiration was strong. Though I had mixed feelings about Luster (

Shipstead (also a Dylan Thomas Prize winner) echoed something Leilani had said: that she starts a novel with questions, not answers. Such humility is refreshing, and a sure way to avoid being preachy in fiction. Her new novel, Great Circle, is among my

Shipstead (also a Dylan Thomas Prize winner) echoed something Leilani had said: that she starts a novel with questions, not answers. Such humility is refreshing, and a sure way to avoid being preachy in fiction. Her new novel, Great Circle, is among my

Lockwood is the only novelist to be included on the Atlantic’s roster of best tweets. She and Nina Stibbe, who interviewed her, agreed that 1) things aren’t funny when they try too hard and 2) the Internet used to be a taboo subject for fiction – producing time-stamped references that editors used to remove. “I had so many observations and I didn’t know where to put them,” Lockwood said, and it seems to her perverse to not write about something that is such a major part of our daily lives. The title of her Women’s Prize-shortlisted novel, No One Is Talking About This (

Lockwood is the only novelist to be included on the Atlantic’s roster of best tweets. She and Nina Stibbe, who interviewed her, agreed that 1) things aren’t funny when they try too hard and 2) the Internet used to be a taboo subject for fiction – producing time-stamped references that editors used to remove. “I had so many observations and I didn’t know where to put them,” Lockwood said, and it seems to her perverse to not write about something that is such a major part of our daily lives. The title of her Women’s Prize-shortlisted novel, No One Is Talking About This (

Like Lockwood, Pachico was part of the “10 @ 10” series featuring debut novelists (though her first book, the linked story collection

Like Lockwood, Pachico was part of the “10 @ 10” series featuring debut novelists (though her first book, the linked story collection

Speaking to Arifa Akbar about

Speaking to Arifa Akbar about

I’ve read more of and gotten on better with Heti’s work than Cusk’s, so this was a rare case of being perhaps more interested in interviewer than interviewee. Heti said that, compared with the Outline trilogy, Cusk’s new novel Second Place feels wilder and more instinctual. Cusk, speaking from the Greek island of Tinos, where she is researching marble quarrying, described her book in often vague yet overall intriguing terms: it’s about exile and the illicit, she said; about femininity and entitlement to speak; about the domestic space and how things are legitimized; about the adoption of male values and the “rightness of the artist.”

I’ve read more of and gotten on better with Heti’s work than Cusk’s, so this was a rare case of being perhaps more interested in interviewer than interviewee. Heti said that, compared with the Outline trilogy, Cusk’s new novel Second Place feels wilder and more instinctual. Cusk, speaking from the Greek island of Tinos, where she is researching marble quarrying, described her book in often vague yet overall intriguing terms: it’s about exile and the illicit, she said; about femininity and entitlement to speak; about the domestic space and how things are legitimized; about the adoption of male values and the “rightness of the artist.”

Maria Magdalena Theotoky is a 23-year-old graduate student at the College of St. John and the Holy Ghost (nicknamed “Spook”) in Toronto. She slept with her advisor, Clement Hollier, precisely once in his office last term. Two events spark the plot: the return of Brother John Parlabane, an ex-monk and -drug addict, and the death of Francis Cornish, a local patron of the arts. Parlabane becomes a university parasite, sleeping on couches and hitting up Maria, Hollier and Anglican priest Simon Darcourt for money. Along with Darcourt and Hollier, Urquhart McVarish, Hollier’s lecherous academic rival, is a third co-executor of Cornish’s artworks and manuscripts. Rumor has it the collection includes a lost manuscript by François Rabelais, the subject of Maria’s research, and Hollier and McVarish fight over it.

Maria Magdalena Theotoky is a 23-year-old graduate student at the College of St. John and the Holy Ghost (nicknamed “Spook”) in Toronto. She slept with her advisor, Clement Hollier, precisely once in his office last term. Two events spark the plot: the return of Brother John Parlabane, an ex-monk and -drug addict, and the death of Francis Cornish, a local patron of the arts. Parlabane becomes a university parasite, sleeping on couches and hitting up Maria, Hollier and Anglican priest Simon Darcourt for money. Along with Darcourt and Hollier, Urquhart McVarish, Hollier’s lecherous academic rival, is a third co-executor of Cornish’s artworks and manuscripts. Rumor has it the collection includes a lost manuscript by François Rabelais, the subject of Maria’s research, and Hollier and McVarish fight over it.