Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde (#NovNov25 Buddy Read, #NonfictionNovember)

This year we set two buddy reads for Novellas in November: one contemporary work of fiction (Seascraper) and one classic work of short nonfiction. Do let us know if you’ve been reading them and what you think!

Sister Outsider is a 1984 collection of Audre Lorde’s essays and speeches. Many of these short pieces appeared in Black or radical feminist magazines or scholarly journals, while a few give the text of her conference presentations. Lorde must have been one of the first writers to spotlight intersectionality: she ponders the combined effect of her Black lesbian identity on how she is perceived and what power she has in society.

The title’s paradox draws attention to the push and pull of solidarity and ostracism. She calls white feminists out for not considering what women of colour endure (or for making her a token Black speaker); she decries misogyny in the Black community; and she and her white lover, Frances, seem to attract homophobia from all quarters. Especially while trying to raise her Black teenage son to avoid toxic masculinity, the author comes to realise the importance of “learning to address each other’s difference with respect.”

This is a point she returns to again and again, and it’s as important now as it was when she was writing in the 1970s. So many forms of hatred and discrimination come down to difference being seen as a threat – “I disagree with you, so I must destroy you” is how she caricatures that perspective.

Even if you’ve never read a word that Lorde wrote, you probably know the phrase “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” – this talk title refers to having to circumvent the racist patriarchy to truly fight oppression. “Revolution is not a one-time event,” she writes in another essay. “It is becoming always vigilant for the smallest opportunity to make a genuine change in established, outgrown responses”.

Even if you’ve never read a word that Lorde wrote, you probably know the phrase “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” – this talk title refers to having to circumvent the racist patriarchy to truly fight oppression. “Revolution is not a one-time event,” she writes in another essay. “It is becoming always vigilant for the smallest opportunity to make a genuine change in established, outgrown responses”.

My two favourite pieces here also feel like they have entered into the zeitgeist. “Poetry Is Not a Luxury” deems poetry a “necessity for our existence … the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought.” And “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power” is a thrilling redefinition of a holistic sensuality that means living at full tilt and tapping into creativity. “The sharing of joy, whether physical, emotional, psychic, or intellectual, forms a bridge between the sharers which can be the basis for understanding much of what is not shared”.

In some ways this is not an ideal way to be introduced to Lorde’s work, because many of the essays repeat the same themes and reasoning. I made my way through the book very slowly, one piece every day or few days. The speeches would almost certainly be more effective if heard aloud, as intended – and more provocative, too, as they must have undermined other speakers’ assumptions. I was also a bit taken aback by the opening and closing pieces being travelogues: “Notes from a Trip to Russia” is based on journal entries from 1976, while “Grenada Revisited: An Interim Report” about a 1983 trip to her mother’s birthplace. I saw more point to the latter, while the former felt somewhat out of place.

Nonetheless, Lorde’s thinking is essential and ahead of its time. I’d only previously read her short work The Cancer Journals. For years my book club has been toying with reading Zami, her memoir starting with growing up in 1930s Harlem, so I’ll hope to move that up the agenda for next year. Have you read any of her other books that you can recommend?(University library) [190 pages]

Other reviews of Sister Outsider:

Cathy (746 Books)

Marcie (Buried in Print) is making her way through the book one essay at a time. Here’s her latest post.

Three on a Theme of Sylvia Plath (The Slicks by Maggie Nelson for #NonfictionNovember & #NovNov25; The Bell Jar and Ariel)

A review copy of Maggie Nelson’s brand-new biographical essay on Sylvia Plath (and Taylor Swift) was the excuse I needed to finally finish a long-neglected paperback of The Bell Jar and also get a taste of Plath’s poetry through the posthumous collection Ariel, which is celebrating its 60th anniversary. These are the sorts of works it’s hard to believe ever didn’t exist; they feel so fully formed and part of the zeitgeist. It also boggles the mind how much Plath accomplished before her death by suicide at age 30. What I previously knew of her life mostly came from hearsay and was reinforced by Euphoria by Elin Cullhed. For the mixture of nonfiction, fiction and poetry represented below, I’m counting this towards Nonfiction November’s Book Pairings week.

The Slicks: On Sylvia Plath and Taylor Swift by Maggie Nelson (2025)

Can young women embrace fame amidst the other cultural expectations of them? Nelson attempts to answer this question by comparing two figures who turn(ed) life into art. The link between them was strengthened by Swift titling her 2024 album The Tortured Poets Department. “Plath … serves as a metonym – as does Swift – for a woman who makes art about a broken heart,” Nelson writes. “When women make the personal public, the charge of whorishness always lurks nearby.” What women are allowed to say and do has always, it seems, attracted public commentary, and “anyone who puts their work into the world, at any level, must learn to navigate between self-protectiveness and risk, becoming harder and staying soft.”

Can young women embrace fame amidst the other cultural expectations of them? Nelson attempts to answer this question by comparing two figures who turn(ed) life into art. The link between them was strengthened by Swift titling her 2024 album The Tortured Poets Department. “Plath … serves as a metonym – as does Swift – for a woman who makes art about a broken heart,” Nelson writes. “When women make the personal public, the charge of whorishness always lurks nearby.” What women are allowed to say and do has always, it seems, attracted public commentary, and “anyone who puts their work into the world, at any level, must learn to navigate between self-protectiveness and risk, becoming harder and staying soft.”

Nelson acknowledges a major tonal difference between Plath and Swift, however. Plath longed for fame but didn’t get the chance to enjoy it; she’s the patron saint of sad-girl poetry and makes frequent reference to death, whereas Swift spotlights joy and female empowerment. It’s a shame this was out of date before it went to print; my advanced copy, at least, isn’t able to comment on Swift’s engagement and the baby rumour mill sure to follow. It would be illuminating to have an afterword in which Nelson discusses the effect of spouses’ competing fame and speculates on how motherhood might change Swift’s art.

Full confession: I’ve only ever knowingly heard one Taylor Swift song, “Anti-Hero,” on the radio in the States. (My assessment was: wordy, angsty, reasonably catchy.) Undoubtedly, I would have gotten more out of this essay were I equally familiar with the two subjects. Nonetheless, it’s fluid and well argued, and I was engaged throughout. If you’re a Swiftie as well as a literary type, you need to read this.

[66 pages]

With thanks to Vintage (Penguin) for the advanced e-copy for review.

The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath (1963)

Given my love of mental hospital accounts and women’s autofiction, it’s a wonder I’d not read this before my forties. It was first published under the pseudonym “Victoria Lucas” because Plath thought it immature, “an autobiographical apprentice work which I had to write in order to free myself from the past.” Esther Greenwood is the stand-in for Plath: a talented college student who, after working in New York City during the remarkable summer of 1953, plunges into mental ill health. Chapter 13 is amazing and awful at the same time as Esther attempts suicide thrice in one day, toying with a silk bathrobe cord and ocean waves before taking 50 pills and walling herself into a corner of the cellar. She bounces between various institutional settings, undergoing electroshock therapy – the first time it’s horrible, but later, under a kind female doctor, it’s more like it’s ‘supposed’ to be: a calming reset.

Given my love of mental hospital accounts and women’s autofiction, it’s a wonder I’d not read this before my forties. It was first published under the pseudonym “Victoria Lucas” because Plath thought it immature, “an autobiographical apprentice work which I had to write in order to free myself from the past.” Esther Greenwood is the stand-in for Plath: a talented college student who, after working in New York City during the remarkable summer of 1953, plunges into mental ill health. Chapter 13 is amazing and awful at the same time as Esther attempts suicide thrice in one day, toying with a silk bathrobe cord and ocean waves before taking 50 pills and walling herself into a corner of the cellar. She bounces between various institutional settings, undergoing electroshock therapy – the first time it’s horrible, but later, under a kind female doctor, it’s more like it’s ‘supposed’ to be: a calming reset.

The 19-year-old is obsessed with the notion of purity. She has a couple of boyfriends but decides to look for someone else to take her virginity. Beforehand, the asylum doctor prescribes her a fitting for a diaphragm. A defiant claim to the right to contraception despite being unmarried is a way of resisting the bell jar – the rarefied prison – of motherhood. Still, Esther feels guilty about prioritizing her work over what seems like feminine duty: “Why was I so maternal and apart? Why couldn’t I dream of devoting myself to baby after fat puling baby? … I was my own woman.” Plath never reconciled parenthood with poetry. Whether that’s the fault of Ted Hughes, or the times they lived in, who can say. For her and for Esther, the hospital is a prison as well – but not so hermetic as the turmoil of her own mind. How ironic to read “I took a deep breath and listened to the old brag of my heart. I am, I am, I am” knowing that this was published just a few weeks before this literary genius ceased to be.

The 19-year-old is obsessed with the notion of purity. She has a couple of boyfriends but decides to look for someone else to take her virginity. Beforehand, the asylum doctor prescribes her a fitting for a diaphragm. A defiant claim to the right to contraception despite being unmarried is a way of resisting the bell jar – the rarefied prison – of motherhood. Still, Esther feels guilty about prioritizing her work over what seems like feminine duty: “Why was I so maternal and apart? Why couldn’t I dream of devoting myself to baby after fat puling baby? … I was my own woman.” Plath never reconciled parenthood with poetry. Whether that’s the fault of Ted Hughes, or the times they lived in, who can say. For her and for Esther, the hospital is a prison as well – but not so hermetic as the turmoil of her own mind. How ironic to read “I took a deep breath and listened to the old brag of my heart. I am, I am, I am” knowing that this was published just a few weeks before this literary genius ceased to be.

Apart from an unfortunate portrayal of a “negro” worker at the hospital, this was an enduringly relevant and absorbing read, a classic to sit alongside Emily Holmes Coleman’s The Shutter of Snow and Janet Frame’s Faces in the Water.

(Secondhand – it’s been in my collection so long I can’t remember where it’s from, but I’d guess a Bowie Library book sale or Wonder Book & Video / Public library – I was struggling with the small type so switched to a recent paperback and found it more readable)

Ariel by Sylvia Plath (1965)

Impossible not to read this looking for clues of her death to come:

Dying

Is an art, like everything else.

I do it exceptionally well.

(from “Lady Lazarus”)

Eternity bores me,

I never wanted it.

(from “Years”)

The woman is perfected.

Her dead

Body wears the smile of accomplishment

(from “Edge”)

I feel incapable of saying anything fresh about this collection, which takes no prisoners. The images and vocabulary are razor-sharp. First and last lines or stanzas are particularly memorable. (“Morning Song” starts “Love set you going like a fat gold watch”; “Lady Lazarus” ends “Out of the ash / I rise with my red hair / And I eat men like air.”) Words and phrases repeat and gather power as they go. “The Applicant” mocks the obligations of a wife: “A living doll … / It can sew, it can cook. It can talk, talk, talk. … // … My boy, it’s your last resort. / Will you marry it, marry it, marry it.” I don’t know a lot about Plath’s family life, only that her father was a Polish immigrant and died after a long illness when she was eight, but there must have been some daddy issues there – after all, “Daddy” includes the barbs “Daddy, I have had to kill you” and “If I’ve killed one man, I’ve killed two— / The vampire who said he was you / And drank my blood for a year, / Seven years, if you want to know.” It ends, “Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through.” Several later poems in a row, including “Stings,” incorporate bee-related imagery, and Plath’s father was an international bee expert. I can see myself reading this again and again in future, and finding her other collections, too – all but one of them posthumous. (Secondhand – RSPCA charity shop, Newbury)

I feel incapable of saying anything fresh about this collection, which takes no prisoners. The images and vocabulary are razor-sharp. First and last lines or stanzas are particularly memorable. (“Morning Song” starts “Love set you going like a fat gold watch”; “Lady Lazarus” ends “Out of the ash / I rise with my red hair / And I eat men like air.”) Words and phrases repeat and gather power as they go. “The Applicant” mocks the obligations of a wife: “A living doll … / It can sew, it can cook. It can talk, talk, talk. … // … My boy, it’s your last resort. / Will you marry it, marry it, marry it.” I don’t know a lot about Plath’s family life, only that her father was a Polish immigrant and died after a long illness when she was eight, but there must have been some daddy issues there – after all, “Daddy” includes the barbs “Daddy, I have had to kill you” and “If I’ve killed one man, I’ve killed two— / The vampire who said he was you / And drank my blood for a year, / Seven years, if you want to know.” It ends, “Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through.” Several later poems in a row, including “Stings,” incorporate bee-related imagery, and Plath’s father was an international bee expert. I can see myself reading this again and again in future, and finding her other collections, too – all but one of them posthumous. (Secondhand – RSPCA charity shop, Newbury)

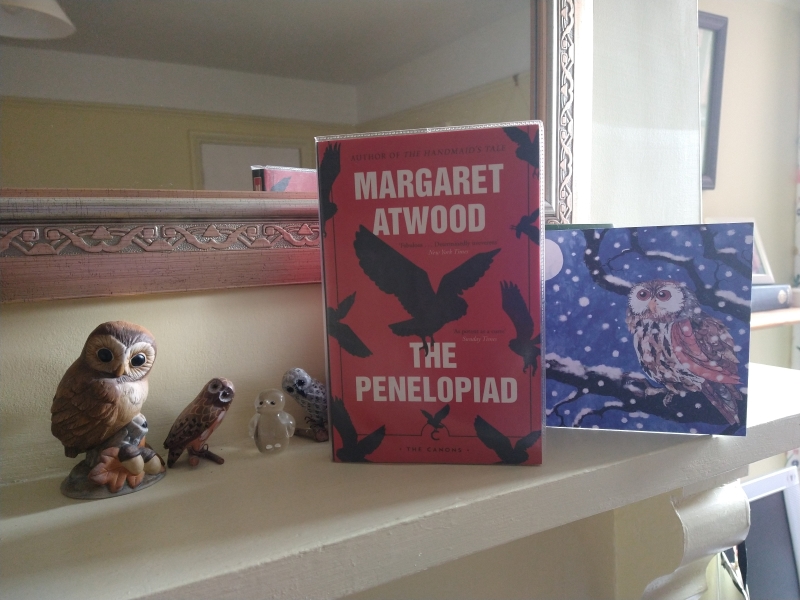

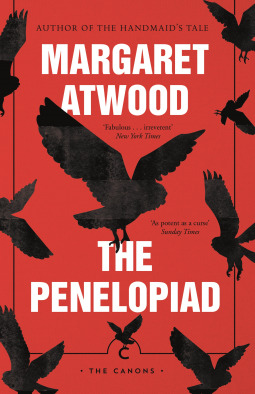

#MARM2025 and #NovNov25: The Penelopiad by Margaret Atwood (2005)

It’s my eighth time participating in the annual Margaret Atwood Reading Month (#MARM) hosted by indomitable Canadian blogger Marcie of Buried in Print. In previous years, I’ve read Surfacing and The Edible Woman, The Robber Bride and Moral Disorder, Wilderness Tips, The Door, Bodily Harm and Stone Mattress, and Life Before Man and Interlunar; and reread The Blind Assassin. Novembers are my excuse to catch up on the soon-to-be-86-year-old’s extensive back catalogue. While awaiting a library hold of her memoir, Book of Lives, I’ve also been rereading the 1983 short story collection Bluebeard’s Egg.

Celebrating its 20th anniversary this year is The Penelopiad, Atwood’s contribution to Canongate’s The Myths series, from which I’ve also read the books by Karen Armstrong, A.S. Byatt, Ali Smith and Jeanette Winterson. I remember Armstrong’s basic point being that a myth is not a falsehood, as in common parlance, but a story that is always true even if not literally factual. Think of it as ‘these things happen’ rather than this happened. Greek mythology is every bit as brutal as the Hebrew Bible, and I find it instructive to interpret biblical stories the same way: Focus on timelessness and universality rather than on historicity.

I do the scheduling for my book club, so I cheekily set The Penelopiad as our November book so that it would count towards two blog challenges. Although it’s a feminist retelling of Homer’s The Odyssey, we concluded that it’s not essential to have prior knowledge of the Greek myths. Much of the narrative is from Penelope’s perspective, including from the afterlife. Cliché has it that she waited patiently for 20 years for her husband Odysseus to return from war, chastely warding off all her would-be suitors. But she admits to readers that both she and Odysseus are inveterate liars.

When Odysseus returned, he murdered the suitors and then Penelope’s maids – some of whom had consensual relations with the men; others of whom were raped. The focus is not on the slaughtered suitors, or on Odysseus’s triumphant return and revenge, but on the dozen maids – viz. the chapter title “Odysseus and Telemachus Snuff the Maids.” The murdered maids form a first-person plural voice (a literal Greek chorus) and speak in poetry and song, also commenting on their own plight through an anthropology lecture and a videotaped trial. They appeal to The Furies for posthumous justice, knowing they won’t get it from men (see the Virago anthology Furies). This sarcastic passage spotlights women’s suffering:

Never mind. Point being that you don’t have to get too worked up about us, dear educated minds. You don’t have to think of us as real girls, real flesh and blood, real pain, real injustice. That might be too upsetting. Just discard the sordid part. Consider us pure symbol. We’re no more real than money.

The cover of The Canons edition hints at the maids’ final transformation into legend.

As well as The Odyssey, Atwood drew on external sources. She considers the theory that Penelope was the leader of a goddess cult. Women are certainly the most interesting characters here. Penelope’s jealousy of her cousin Helen (of Troy) and her rocky relationship with her teenage son Telemachus are additional threads. Eurycleia, Odysseus’s nurse, is a minor character, and there is mention of Penelope’s mother, a Naiad. Odysseus himself comes across not as the brave hero but as brash, selfish and somewhat absurd.

As well as The Odyssey, Atwood drew on external sources. She considers the theory that Penelope was the leader of a goddess cult. Women are certainly the most interesting characters here. Penelope’s jealousy of her cousin Helen (of Troy) and her rocky relationship with her teenage son Telemachus are additional threads. Eurycleia, Odysseus’s nurse, is a minor character, and there is mention of Penelope’s mother, a Naiad. Odysseus himself comes across not as the brave hero but as brash, selfish and somewhat absurd.

Like Atwood’s other work, then, The Penelopiad is subversive and playful. We wondered whether it set the trend for Greek myth retellings – given that those by Pat Barker, Natalie Haynes, Madeline Miller, Jennifer Saint and more emerged 5–15 years later. It wouldn’t be a surprise: she has always been wise and ahead of her time, a puckish prophetess. This fierce, funny novella isn’t among my favourites of the 30 Atwood titles I’ve now read, but it was an offbeat selection that made for a good book club discussion – and it wouldn’t be the worst introduction to her feminist viewpoint.

(Public library)

[198 pages]

![]()

Reading Wales Month: Tishani Doshi & Ruth Janette Ruck (#ReadingWales25)

It’s my first time participating in Reading Wales Month, hosted this year by Karen of BookerTalk. I happened to be reading a collection by a Welsh-Gujarati poet, and added a Welsh hill farming memoir to my stack so I could review two books towards this challenge.

A God at the Door by Tishani Doshi (2021)

I discovered Doshi through the phenomenal Girls Are Coming out of the Woods, which I reviewed for Wasafiri literary magazine. This fourth collection is just as rich in long, forthright feminist and political poems. Violence against women is a theme that crops up again and again in her work, as in “Every Unbearable Thing”: “this is not / a poem against longing / but against the kind of one-way / desire that herds you into a / dead-end alley”. The arresting title of the sestina “We Will Not Kill You. We’ll Just Shoot You in the Vagina” is something the former Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte said in 2018 in reference to female communist rebels. Doshi links femicide and ecocide with “A Possible Explanation as to Why We Mutilate Women & Trees, which Tries to End on a Note of Hope”. Her poem titles are often striking and tell stories in and of themselves. Several made me laugh, such as “Advice for Pliny the Elder, Big Daddy of Mansplainers,” which is shaped like a menstrual cup.

I discovered Doshi through the phenomenal Girls Are Coming out of the Woods, which I reviewed for Wasafiri literary magazine. This fourth collection is just as rich in long, forthright feminist and political poems. Violence against women is a theme that crops up again and again in her work, as in “Every Unbearable Thing”: “this is not / a poem against longing / but against the kind of one-way / desire that herds you into a / dead-end alley”. The arresting title of the sestina “We Will Not Kill You. We’ll Just Shoot You in the Vagina” is something the former Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte said in 2018 in reference to female communist rebels. Doshi links femicide and ecocide with “A Possible Explanation as to Why We Mutilate Women & Trees, which Tries to End on a Note of Hope”. Her poem titles are often striking and tell stories in and of themselves. Several made me laugh, such as “Advice for Pliny the Elder, Big Daddy of Mansplainers,” which is shaped like a menstrual cup.

In defiance of those who would destroy it, Doshi affirms the primacy of the body. The joyfully absurd “In a Dream I Give Birth to a Sumo Wrestler” ends with the lines “How easy to forget / that all we have are these bodies. That all of this, all of this is holy.” Poems are inspired by Emily Dickinson and Frida Kahlo as well as by real events that provoke outrage. The clever folktale-like pair “Microeconomics” and “Macroeconomics” contrasts a woman dutifully growing peas and trying to get ahead with exploitative situations: “One man sits on another if he can. … One man goes / into the mines for another man to sparkle.” I also found many wise words on grief. Doshi is a treasure. (Secondhand – Green Ink Booksellers, Hay-on-Wye) ![]()

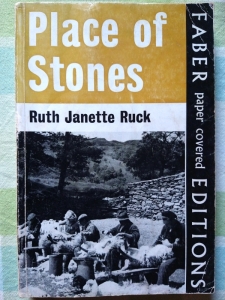

Place of Stones by Ruth Janette Ruck (1961)

“Farming is rather like the theatre—whatever happens the show must go on.”

I reviewed Ruck’s Along Came a Llama several years ago when it was re-released by Faber. This was the first of her three memoirs about life at Carneddi (which means “place of stones”), the hill farm in North Wales that she and her family took over in the 1950s. After college, Ruck trained at a farm on the Isle of Wight and later completed an apprenticeship at Oathill Farm, Oxfordshire under George Henderson, who seems to have been something of a celebrity farmer back then (he contributes a brief but complimentary foreword). By age 20 she was in full charge of Carneddi, where they kept sheep, cattle and fowl. Many of their neighbours had Welsh as a first or only language. At that time, farmers were eligible for government grants. Ruck put in an intensive hen-rearing barn and started growing strawberries and rearing turkeys for Christmas.

I reviewed Ruck’s Along Came a Llama several years ago when it was re-released by Faber. This was the first of her three memoirs about life at Carneddi (which means “place of stones”), the hill farm in North Wales that she and her family took over in the 1950s. After college, Ruck trained at a farm on the Isle of Wight and later completed an apprenticeship at Oathill Farm, Oxfordshire under George Henderson, who seems to have been something of a celebrity farmer back then (he contributes a brief but complimentary foreword). By age 20 she was in full charge of Carneddi, where they kept sheep, cattle and fowl. Many of their neighbours had Welsh as a first or only language. At that time, farmers were eligible for government grants. Ruck put in an intensive hen-rearing barn and started growing strawberries and rearing turkeys for Christmas.

Even when things were going well, it was a hand-to-mouth existence and storms or illness could set everything back. The Rucks renovated a nearby cottage to serve as a holiday let. Another windfall came in the bizarre form of a nearby film shoot by Twentieth Century Fox (The Inn of the Sixth Happiness, starring Ingrid Bergman). Mountainous North Wales stood in for China, and the film crew hired Ruck as a driver and, like many locals, as an occasional extra. This book was light and mildly entertaining, though probably more detailed about everyday farm work and projects than I needed. I was reminded again of Doreen Tovey, especially in the passage about Topsy the pet black sheep, but also this time of Betty Macdonald (The Egg and I) and Janet White (The Sheep Stell). (Secondhand – Lions bookshop, Alnwick) ![]()

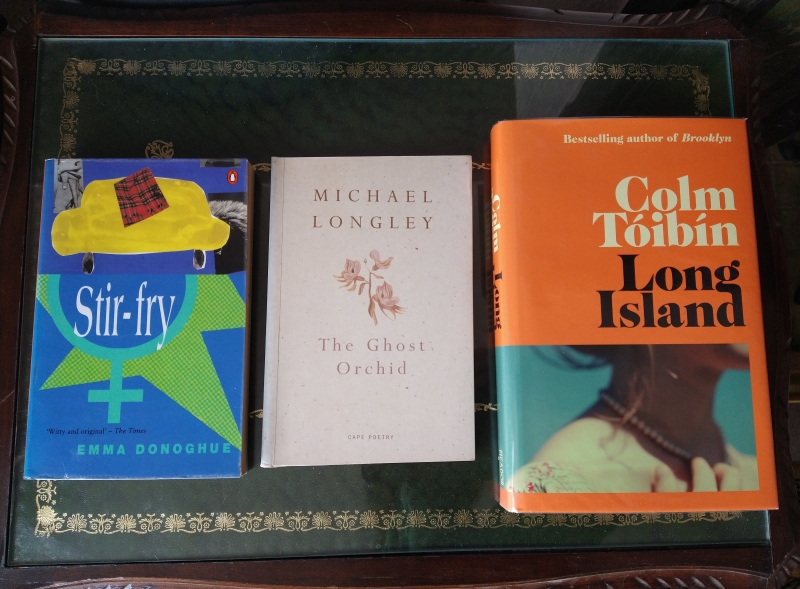

Reading Ireland Month, I: Donoghue, Longley, Tóibín

St. Patrick’s Day is a good occasion to compile my first set of contributions to Cathy’s Reading Ireland Month. Today I have an early novel by a favourite author, a poetry collection inspired by nature and mythology, and a sequel that I read for book club.

Stir-Fry by Emma Donoghue (1994)

After enjoying Slammerkin so much last year, I decided to catch up on more of Donoghue’s way-back catalogue. She tends to alternate between contemporary and historical settings. I have a slight preference for the former, but she can excel at both; it really depends on the book. I reckon this was edgy for its time. Maria (whose name rhymes with “pariah”) arrives in Dublin for university at age 17, green in every way after a religious upbringing in the countryside. In response to a flat-share advert stipulating “NO BIGOTS,” she ends up living with Ruth and Jael (pronounced “Yale”), two mature students. Ruth is the mother hen, doing all the cooking and fretting over the others’ wellbeing; Jael is a wild, henna-haired 30-year-old prone to drinking whisky by the mug-full. Maria attends lectures, takes a job cleaning office buildings, and finds a friend circle through her backstage student theatre volunteering. She’s mildly interested in American exchange student Galway and then leather-clad Damien (until she realizes he has a boyfriend), but nothing ever goes further than a kiss.

It’s obvious to readers that Ruth and Jael are a couple, but Maria doesn’t work it out until a third of the way into the book. At first she’s mortified, but soon the realization is just one more aspect of her coming of age. Maria’s friend Yvonne can’t understand why she doesn’t leave – “how can you put up with being a gooseberry?” – but Maria insists, “They really don’t make me feel left out … I think they need me to absorb some of the static. They say they’d be fighting like cats if I wasn’t around to distract them.” Scenes alternate between the flat and the campus, which Donoghue depicts as a place where radicalism and repression jostle for position. Ruth drags Maria to a Tuesday evening Women’s Group meeting that ends abruptly: “A porter put his greying head in the door to comment that they’d have to be out in five minutes, girls, this room was booked for the archaeologists’ cheese ’n’ wine.” Later, Ruth’s is the Against voice in a debate on “That homosexuality is a blot on Irish society.”

It’s obvious to readers that Ruth and Jael are a couple, but Maria doesn’t work it out until a third of the way into the book. At first she’s mortified, but soon the realization is just one more aspect of her coming of age. Maria’s friend Yvonne can’t understand why she doesn’t leave – “how can you put up with being a gooseberry?” – but Maria insists, “They really don’t make me feel left out … I think they need me to absorb some of the static. They say they’d be fighting like cats if I wasn’t around to distract them.” Scenes alternate between the flat and the campus, which Donoghue depicts as a place where radicalism and repression jostle for position. Ruth drags Maria to a Tuesday evening Women’s Group meeting that ends abruptly: “A porter put his greying head in the door to comment that they’d have to be out in five minutes, girls, this room was booked for the archaeologists’ cheese ’n’ wine.” Later, Ruth’s is the Against voice in a debate on “That homosexuality is a blot on Irish society.”

Mostly, this short novel is a dance between the three central characters. The Irish-accented banter between them is a joy. Jael’s devil-may-care attitude contrasts with Ruth and Maria’s anxiety about how they are perceived by others. Ruth and Jael are figures in the Hebrew Bible and their devotion/boldness dichotomy is applicable to the characters here, too. The stereotypical markers of lesbian identity haven’t really changed, but had Donoghue written this now I think she would at least have made Maria a year older and avoided negativity about Damien and Jael’s bisexuality. At heart this is a sweet romance and an engaging picture of early 1990s feminism, but it doesn’t completely steer clear of predictability and I would have happily taken another 50–70 pages if it meant she could have fleshed out the characters and their interactions a little more. [Guess what was for my lunch this afternoon? Stir fry!] (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

The Ghost Orchid by Michael Longley (1995)

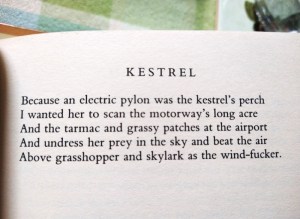

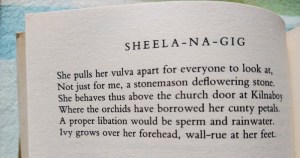

Longley’s sixth collection draws much of its imagery from nature and Greek and Roman classics. Seven poems incorporate quotations and free translations of the Iliad and Odyssey; elsewhere, he retells the story of Baucis and Philemon and other characters from Ovid. The Orient and the erotic are also major influences; references to Hokusai bookend poems about Chinese artefacts. Poppies link vignettes of the First and Second World Wars. Longley’s poetry is earthy in its emphasis on material objects and sex. Alliteration and slant rhymes are common techniques and the vocabulary is always precise. This was the third collection I’ve read by the late Belfast poet, and with its disparate topics it didn’t all cohere for me. My two favourite poems are naughty indeed:

Longley’s sixth collection draws much of its imagery from nature and Greek and Roman classics. Seven poems incorporate quotations and free translations of the Iliad and Odyssey; elsewhere, he retells the story of Baucis and Philemon and other characters from Ovid. The Orient and the erotic are also major influences; references to Hokusai bookend poems about Chinese artefacts. Poppies link vignettes of the First and Second World Wars. Longley’s poetry is earthy in its emphasis on material objects and sex. Alliteration and slant rhymes are common techniques and the vocabulary is always precise. This was the third collection I’ve read by the late Belfast poet, and with its disparate topics it didn’t all cohere for me. My two favourite poems are naughty indeed:

(Secondhand – Green Ink Booksellers, Hay-on-Wye) ![]()

Long Island by Colm Tóibín (2024)

{SPOILERS in this one}

I read Brooklyn when it first came out and didn’t revisit it (via book or film) before reading this. While recent knowledge of the first book isn’t necessary, it probably would make you better able to relate to Eilis, who is something of an emotional blank here. She’s been married for 20 years to Tony, a plumber, and is a mother to two teenagers. His tight-knit Italian American family might be considered nurturing, but for her it is more imprisoning: their four houses form an enclave and she’s secretly relieved when her mother-in-law tells her she needn’t feel obliged to join in the Sunday lunch tradition anymore.

I read Brooklyn when it first came out and didn’t revisit it (via book or film) before reading this. While recent knowledge of the first book isn’t necessary, it probably would make you better able to relate to Eilis, who is something of an emotional blank here. She’s been married for 20 years to Tony, a plumber, and is a mother to two teenagers. His tight-knit Italian American family might be considered nurturing, but for her it is more imprisoning: their four houses form an enclave and she’s secretly relieved when her mother-in-law tells her she needn’t feel obliged to join in the Sunday lunch tradition anymore.

When news comes that Tony has impregnated a married woman and the cuckolded husband plans to leave the baby on the Fiorellos’ doorstep when the time arrives, Eilis checks out of the marriage. She uses her mother’s upcoming 80th birthday as an excuse to go back to Ireland for the summer. Here Eilis gets caught up in a love triangle with publican Jim Farrell, who was infatuated with her 20 years ago and still hasn’t forgotten her, and Nancy Sheridan, a widow who runs a fish and chip shop and has been Jim’s secret lover for a couple of years. Nancy has a vision of her future and won’t let Eilis stand in her way.

I felt for all three in their predicaments but most admired Nancy’s pluck. Ironically given the title, the novel spends more of its time in Ireland and only really comes alive there. There’s also a reference to Nora Webster – cute that Tóibín is trying out the Elizabeth Strout trick of bringing multiple characters together in the same fictional community. But, all told, this was just a so-so book. I’ve read 10 or so works by Tóibín now, in all sorts of genres, and with its plain writing this didn’t stand out at all. It got an average score from my book club, with one person loving it, a couple hating it, and most fairly indifferent. (Public library) ![]()

Another batch will be coming up before the end of the month!

Hard-Hitting Nonfiction I Read for #NovNov24: Hammad, Horvilleur, Houston & Solnit

I often play it safe with my nonfiction reading, choosing books about known and loved topics or ones that I expect to comfort me or reinforce my own opinions rather than challenge me. I wasn’t sure if I could bear to read about Israel/Palestine, or sexual violence towards women, but these four works were all worthwhile – even if they provoked many an involuntary gasp of horror (and mild expletives).

Recognising the Stranger: On Palestine and Narrative by Isabella Hammad (2024)

This is the text of the Edward W. Said Memorial Lecture that Hammad delivered at Columbia University on September 28, 2023. She posits that, in a time of crisis, storytelling can be a way of finding things out. Characters’ epiphanies, from Oedipus onward, see them encountering an Other but learning something about themselves in the process. In turning her great-grandfather’s life into her first novel, The Parisian, Hammad knew she had to avoid the pitfalls of nostalgia and unreliable memory. Fiction is always subjective, a matter of perspectives, and history is too. Sometimes the turning points will only be understood retrospectively.

This is the text of the Edward W. Said Memorial Lecture that Hammad delivered at Columbia University on September 28, 2023. She posits that, in a time of crisis, storytelling can be a way of finding things out. Characters’ epiphanies, from Oedipus onward, see them encountering an Other but learning something about themselves in the process. In turning her great-grandfather’s life into her first novel, The Parisian, Hammad knew she had to avoid the pitfalls of nostalgia and unreliable memory. Fiction is always subjective, a matter of perspectives, and history is too. Sometimes the turning points will only be understood retrospectively.

Edward Said (1935–2003) was a Palestinian American academic and theorist who helped found the field of postcolonial studies. Hammad writes that, for him, being Palestinian was “a condition of chronic exile.” She takes his humanist ideology as a model of how to “dismantle the consoling fictions of fixed identity, which make it easier to herd into groups.” About half of the lecture is devoted to the Israel/Palestine situation. She recalls meeting an Israeli army deserter a decade ago who told her how a naked Palestinian man holding the photograph of a child had approached his Gaza checkpoint; instead of shooting the man in the leg as ordered, he fled. It shouldn’t take such epiphanies to get Israelis to recognize Palestinians as human, but Hammad acknowledges the challenge in a “militarized society” of “state propaganda.”

This was, for me, more appealing than Hammad’s Enter Ghost. Though the essay might be better aloud as originally intended, I found it fluent and convincing. It was, however, destined to date quickly. Less than two weeks later, on October 7, there was a horrific Hamas attack on Israel (see Horvilleur, below). The print version of the lecture includes an afterword written in the wake of the destruction of Gaza. Hammad does not address October 7 directly, which seems fair (Hamas ≠ Palestine). Her language is emotive and forceful. She refers to “settler colonialism and ethnic cleansing” and rejects the argument that it is a question of self-defence for Israel – that would require “a fight between two equal sides,” which this absolutely is not. Rather, it is an example of genocide, supported by other powerful nations.

The present onslaught leaves no space for mourning

To remain human at this juncture is to remain in agony

It will be easy to say, in hindsight, what a terrible thing

The Israeli government would like to destroy Palestine, but they are mistaken if they think this is really possible … they can never complete the process, because they cannot kill us all.

(Read via Edelweiss) [84 pages] ![]()

How Isn’t It Going? Conversations after October 7 by Delphine Horvilleur (2025)

[Translated from the French by Lisa Appignanesi]

Horvilleur is one of just five female rabbis in France and is the leader of the country’s Liberal Jewish Movement. Earlier this year, I reviewed her essay collection Living with Our Dead, about attitudes toward death as illustrated by her family history, Jewish traditions and teachings, and funerals she has conducted. It is important to note that she expresses sorrow for Palestinians’ situation and mentions that she has always favoured a two-state solution. Moreover, she echoes Hammad with her final line, which hopes for “a future for those who think of the other, for those who engage in dialogue one with another, and with the humanity within them.” However, this is a lament for the Jewish condition, and a warning of the continuing and insidious nature of antisemitism. Who am I to judge her lived experience and say, “she’s being paranoid” or “it’s not really like that”? My job as reader is simply to listen.

Horvilleur is one of just five female rabbis in France and is the leader of the country’s Liberal Jewish Movement. Earlier this year, I reviewed her essay collection Living with Our Dead, about attitudes toward death as illustrated by her family history, Jewish traditions and teachings, and funerals she has conducted. It is important to note that she expresses sorrow for Palestinians’ situation and mentions that she has always favoured a two-state solution. Moreover, she echoes Hammad with her final line, which hopes for “a future for those who think of the other, for those who engage in dialogue one with another, and with the humanity within them.” However, this is a lament for the Jewish condition, and a warning of the continuing and insidious nature of antisemitism. Who am I to judge her lived experience and say, “she’s being paranoid” or “it’s not really like that”? My job as reader is simply to listen.

There is by turns a stream of consciousness or folktale quality to the narrative as Horvilleur enacts 11 dialogues – some real and others imagined – with her late grandparents, her children, or even abstractions (“Conversation with My Pain,” “Conversation with the Messiah”). She draws on history, scripture and her own life, wrestling with the kinds of thoughts that come to her during insomniac early mornings. It’s not all mourning; there is sometimes a wry sense of humour that feels very Jewish. While it was harder for me to relate to the point of view here, I admired the author for writing from her own ache and tracing the repeated themes of exile and persecution. It felt important to respect and engage. [125 pages] ![]()

With thanks to Europa Editions for the advanced e-copy for review.

Without Exception: Reclaiming Abortion, Personhood, and Freedom by Pam Houston (2024)

If you’re going to read a polemic, make sure it’s as elegantly written and expertly argued as this one. Houston responds to the overturning of Roe v. Wade with 60 micro-essays – one for each full year of her life – about what it means to be in a female body in a country that seeks to control and systematically devalue women. Roe was in force for 49 years, corresponding almost exactly to her reproductive years. She had three abortions and believes “childlessness might turn out to be the single greatest gift of my life.” Facts could serve as explanations: her grandmother died giving birth to her mother; her mother always said having her ruined her life; she was raped by her father from early childhood until she left home as a young adult; she is gender-fluid; she loves her life of adventure travel, spontaneity and chosen solitude; she adores the natural world and sees how overpopulation threatens it. But none are presented as causes or excuses. Houston is committed to nuance, recognizing individuality of circumstance and the primacy of choice.

If you’re going to read a polemic, make sure it’s as elegantly written and expertly argued as this one. Houston responds to the overturning of Roe v. Wade with 60 micro-essays – one for each full year of her life – about what it means to be in a female body in a country that seeks to control and systematically devalue women. Roe was in force for 49 years, corresponding almost exactly to her reproductive years. She had three abortions and believes “childlessness might turn out to be the single greatest gift of my life.” Facts could serve as explanations: her grandmother died giving birth to her mother; her mother always said having her ruined her life; she was raped by her father from early childhood until she left home as a young adult; she is gender-fluid; she loves her life of adventure travel, spontaneity and chosen solitude; she adores the natural world and sees how overpopulation threatens it. But none are presented as causes or excuses. Houston is committed to nuance, recognizing individuality of circumstance and the primacy of choice.

Many of the book’s vignettes are autobiographical, but others recount statistics, track American cultural and political shifts, and reprint excerpts from the 2022 joint dissent issued by the Supreme Court. The cycling of topics makes for an exquisite structure. Houston has done extensive research on abortion law and health care for women. A majority of Americans actually support abortion’s legality, and some states have fought back by protecting abortion rights through referenda. (I voted for Maryland’s. I’ve come a long way since my Evangelical, vociferously pro-life high school and college days.) I just love Houston’s work. There are far too many good lines here to quote. She is among my top recommendations of treasured authors you might not know. I’ve read her memoir Deep Creek and her short story collections Cowboys Are My Weakness and Waltzing the Cat, and I’m already sad that I only have four more books to discover. (Read via Edelweiss) [170 pages] ![]()

Men Explain Things to Me by Rebecca Solnit (2014)

Solnit did not coin the term “mansplaining,” but it was created not long after the title essay’s publication in 2008 and was definitely inspired by her depiction of a male know-it-all. She was at a party in Aspen in 2003 when a man decided to tell her all about an important new book he’d heard of about Eadweard Muybridge. A friend had to interrupt him and say, “That’s her book.” A funny story, yes, but illustrative of a certain male arrogance that encourages a woman’s “belief in her superfluity, an invitation to silence” and imagines her “in some sort of obscene impregnation metaphor, an empty vessel to be filled with their wisdom and knowledge.”

Solnit did not coin the term “mansplaining,” but it was created not long after the title essay’s publication in 2008 and was definitely inspired by her depiction of a male know-it-all. She was at a party in Aspen in 2003 when a man decided to tell her all about an important new book he’d heard of about Eadweard Muybridge. A friend had to interrupt him and say, “That’s her book.” A funny story, yes, but illustrative of a certain male arrogance that encourages a woman’s “belief in her superfluity, an invitation to silence” and imagines her “in some sort of obscene impregnation metaphor, an empty vessel to be filled with their wisdom and knowledge.”

This segues perfectly into “The Longest War,” about sexual violence against women, including rape and domestic violence. As in the Houston, there are some absolutely appalling statistics here. Yes, she acknowledges, it’s not all men, and men can be feminist allies, but there is a problem with masculinity when nearly all domestic violence and mass shootings are committed by men. There is a short essay on gay marriage and one (slightly out of place?) about Virginia Woolf’s mental health. The other five repeat some of the same messages about rape culture and believing women, so it is not a wholly classic collection for me, but the first two essays are stunners. (University library) [154 pages] ![]()

Have you read any of these authors? Or something else on these topics?

Three on a Theme: Books on Communes by Crossman, Heneghan & Twigg

Communal living always seems like a great idea but rarely works out well. Why? The short answer: Because people. A longer answer: Political ideals are hard to live out in the everyday when egos clash, practical arrangements become annoying, and lines of privacy or autonomy get crossed. All three books I review today are set in the aftermath of utopian failure. Susanna Crossman, who grew up in an English commune, looks back at 15 years of an abnormal childhood. The community in Birdeye is set to collapse after two founding members announce their departure, leaving one ageing woman and her disabled daughter. And in Spoilt Creatures, from a decade’s distance, Iris narrates the disastrous downfall of Breach House.

Home Is Where We Start: Growing up in the Fallout of the Utopian Dream by Susanna Crossman

For Crossman’s mother, “the community” was a refuge, a place to rebuild their family’s life after divorce and the death of her oldest daughter in a freak accident. For her three children, it initially was a place of freedom and apparent equality between “the Adults” and “the Kids” – who were swiftly indoctrinated into hippie opinions on the political matters of the day. “There is no difference between private and public conversations, between the inside and the outside. No euphemisms. Vaginas are discussed over breakfast alongside domestic violence and nuclear bombs.” Crossman’s present-tense recreation of her precocious eight-year-old perspective is canny, as when she describes watching Charles and Diana’s wedding on television:

It was beautiful, but I know marriage is a patriarchal institution, a capitalist trap, a snare. You can read about it in Spare Rib, or if you ask community members, someone will tell you marriage is legalized rape. It is a construction, and that means it’s not natural, and is part of the social reproduction of gender roles and women’s unpaid domestic labour.

Their mum, now known only as “Alison,” often seemed unaware of what the Kids got up as they flitted in and out of each other’s units. Crossman once electrocuted herself at a plug. Another time she asked if she could go to an adult man’s unit for an offered massage. Both times her mother was unfazed.

Their mum, now known only as “Alison,” often seemed unaware of what the Kids got up as they flitted in and out of each other’s units. Crossman once electrocuted herself at a plug. Another time she asked if she could go to an adult man’s unit for an offered massage. Both times her mother was unfazed.

The author is now a clinical arts therapist, so her recreation is informed by her knowledge of healthy child development and the long-term effects of trauma. She knows the Kids suffered from a lack of routine and individually expressed love. Community rituals, such as opening Christmas presents in the middle of a circle of 40 onlookers, could be intimidating rather than welcoming. Her molestation and her sister’s rape (when she was nine years old, on a trip to India ‘supervised’ by two other adults from the community) were cloaked in silence.

Crossman weaves together memoir and psychological theory as she examines where the utopian impulse comes from and compares her own upbringing with how she tries to parent her three daughters differently at home in France. Through vignettes based on therapy sessions with patients, she shows how play and the arts can help. (I’d forgotten that I’ve encountered Crossman’s writing before, through her essay on clowning for the Trauma anthology.) I somewhat lost interest as the Kids grew into teenagers. It’s a vivid and at times rather horrifying book, but the author doesn’t resort to painting pantomime villains. Behind things were good intentions, she knows, and there is nuance and complexity to her account. It’s a great mix of being back in the moment and having the hindsight to see it all clearly.

With thanks to Fig Tree (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Birdeye by Judith Heneghan

Like Crossman’s community, the Birdeye Colony is based in a big crumbling house in the countryside – but this time in the USA; the Catskills of upstate New York, to be precise. Liv Ferrars has been the de facto leader for nearly 50 years, since she was a young mother to twins. Now she’s a sixty-seven-year-old breast cancer survivor. To her amazement, her book, The Attentive Heart, still attracts visitors, “bringing their problems, their pain and loneliness, hoping to be mended, made whole.”

One of the ur-plots is “a stranger comes to town,” and that’s how Birdeye opens, with the arrival of a young man named Conor who’s read and admired Liv’s book, and seems to know quite a lot about the place. When Indian American siblings Sonny and Mishti, the only others who have been there almost from the beginning, announce that they’re leaving, it seems Birdeye is doomed. But Liv wonders if Conor can be part of a new generation to take it on.

One of the ur-plots is “a stranger comes to town,” and that’s how Birdeye opens, with the arrival of a young man named Conor who’s read and admired Liv’s book, and seems to know quite a lot about the place. When Indian American siblings Sonny and Mishti, the only others who have been there almost from the beginning, announce that they’re leaving, it seems Birdeye is doomed. But Liv wonders if Conor can be part of a new generation to take it on.

It’s a bit of a sleepy book, with a touch of suspense as secrets emerge from Birdeye’s past. I was slightly reminded of May Sarton’s Kinds of Love. I most appreciated the character study of Liv and her very different relationships with her daughters, who are approaching fifty: Mary is a capable lawyer in London, while Rose suffered oxygen deprivation at birth and is severely intellectually disabled. Since Liv’s illness, Mary has pressured her to make plans for Rose’s future and, ultimately, her own. The duty of care we bear towards others – blood family; the chosen family of friends and comrades, even pets – arises as a major theme. I’d recommend this to those who love small-town novels.

With thanks to Salt Publishing for the free copy for review.

& 20 Books of Summer, #20:

Spoilt Creatures by Amy Twigg

Alas, this proved to be another disappointment from the Observer’s 10 best new novelists feature (following How We Named the Stars by Andrés N. Ordorica). The setup was promising: in 2008, Iris reeling from her break-up from Nathan and still grieving her father’s death in a car accident, goes to live at Breach House after a chance meeting with Hazel, one of the women’s commune’s residents. “Breach House was its own ecosystem, removed from the malfunctioning world of indecision and patriarchy.” Any attempts to mix with the outside world go awry, and the women gain a reputation as strange and difficult. I never got a handle on the secondary characters, who fill stock roles (the megalomaniac leader, the reckless one, the disgruntled one), and it all goes predictably homoerotic and then Lord of the Flies. The dual-timeline structure with Iris’s reflections from 10 years later adds little. An example of the commune plot done poorly, with shallow conclusions rather than deeper truths at play.

Alas, this proved to be another disappointment from the Observer’s 10 best new novelists feature (following How We Named the Stars by Andrés N. Ordorica). The setup was promising: in 2008, Iris reeling from her break-up from Nathan and still grieving her father’s death in a car accident, goes to live at Breach House after a chance meeting with Hazel, one of the women’s commune’s residents. “Breach House was its own ecosystem, removed from the malfunctioning world of indecision and patriarchy.” Any attempts to mix with the outside world go awry, and the women gain a reputation as strange and difficult. I never got a handle on the secondary characters, who fill stock roles (the megalomaniac leader, the reckless one, the disgruntled one), and it all goes predictably homoerotic and then Lord of the Flies. The dual-timeline structure with Iris’s reflections from 10 years later adds little. An example of the commune plot done poorly, with shallow conclusions rather than deeper truths at play.

With thanks to Tinder Press for the free copy for review.

On this topic, I have also read:

Novels:

Arcadia by Lauren Groff

The Blithedale Romance by Nathaniel Hawthorne

On my TBR:

O Sinners by Nicole Cuffy

We Burn Daylight by Bret Anthony Johnston

Nonfiction:

Heaven Is a Place on Earth by Adrian Shirk

Recent Poetry Releases by Anderson, Godden, Gomez, Goodan, Lewis & O’Malley

Nature, social engagement, and/or women’s stories are linking themes across these poetry collections, much as they vary in their particulars. After my brief thoughts, I offer one sample poem from each book.

And I Will Make of You a Vowel Sound by Morag Anderson

Morag Anderson was the 2023 Makar of the Federation of Writers in Scotland. She won the Aryamati Pamphlet Prize for this second chapbook of 25 poems. Her subjects are ordinary people: abandoned children, a young woman on a council estate, construction workers, and a shoplifter who can’t afford period products. The verse is rich with alliteration, internal rhymes and neologisms. Although sub/urban settings predominate, there are also poems dedicated to birds and to tracking the seasons’ march along a river. There is much sibilance to “Little Wren,” while “Cormorant Speaks” enchants with its fresh compound words: “Barefoot in mudslick streambeds I pathpick over rotsoft limbs, wade neckdeep in suncold loch”. “No Ordinary Tuesday, 2001” is about 9/11 and “None of the Nine Were There” expresses feminist indignation at the repeal of Roe v. Wade: “all nine were busy / stitching rules into the seams / of bleeding wombs.” A trio of poems depicts the transformation of matrescence: “Long after my shelterbody shucks / her reluctant skull / from my shell, // her foetal cells— / rosefoamed in my core— / migrate to mend my flensed heart.” Impassioned and superbly articulated. A confident poet whose work I was glad to discover.

Morag Anderson was the 2023 Makar of the Federation of Writers in Scotland. She won the Aryamati Pamphlet Prize for this second chapbook of 25 poems. Her subjects are ordinary people: abandoned children, a young woman on a council estate, construction workers, and a shoplifter who can’t afford period products. The verse is rich with alliteration, internal rhymes and neologisms. Although sub/urban settings predominate, there are also poems dedicated to birds and to tracking the seasons’ march along a river. There is much sibilance to “Little Wren,” while “Cormorant Speaks” enchants with its fresh compound words: “Barefoot in mudslick streambeds I pathpick over rotsoft limbs, wade neckdeep in suncold loch”. “No Ordinary Tuesday, 2001” is about 9/11 and “None of the Nine Were There” expresses feminist indignation at the repeal of Roe v. Wade: “all nine were busy / stitching rules into the seams / of bleeding wombs.” A trio of poems depicts the transformation of matrescence: “Long after my shelterbody shucks / her reluctant skull / from my shell, // her foetal cells— / rosefoamed in my core— / migrate to mend my flensed heart.” Impassioned and superbly articulated. A confident poet whose work I was glad to discover.

With thanks to Fly on the Wall Press for the free copy for review.

With Love, Grief and Fury by Salena Godden

“In a time of apathy, / hope is a revolutionary act”. I knew Godden from her hybrid novel Mrs Death Misses Death, but this was my first taste of the poetry for which she is better known. The title gives a flavour of the variety in tone. Poems arise from environmental anxiety; feminist outrage at discrimination and violence towards women; and personal experiences of bisexuality, being childfree (“Book Mother” and “Egg and Spoon Race”), and entering perimenopause (“Evergreen Tea”). Solidarity and protest are strategies for dispelling ignorance about all of the above. Godden also marks the rhythms of everyday life for a single artist, and advises taking delight in life’s small pleasures. The social justice angle made it a perfect book for me to read portions of on the Restore Nature Now march through London in June …

“In a time of apathy, / hope is a revolutionary act”. I knew Godden from her hybrid novel Mrs Death Misses Death, but this was my first taste of the poetry for which she is better known. The title gives a flavour of the variety in tone. Poems arise from environmental anxiety; feminist outrage at discrimination and violence towards women; and personal experiences of bisexuality, being childfree (“Book Mother” and “Egg and Spoon Race”), and entering perimenopause (“Evergreen Tea”). Solidarity and protest are strategies for dispelling ignorance about all of the above. Godden also marks the rhythms of everyday life for a single artist, and advises taking delight in life’s small pleasures. The social justice angle made it a perfect book for me to read portions of on the Restore Nature Now march through London in June …

… and while volunteering as an election teller at a polling station last week. It contains 81 poems (many of them overlong prose ones), making for a much lengthier collection than I would usually pick up. The repetition, wordplay and run-on sentences are really meant more for performance than for reading on the page, but if you’re a fan of Hollie McNish or Kae Tempest, you’re likely to enjoy this, too.

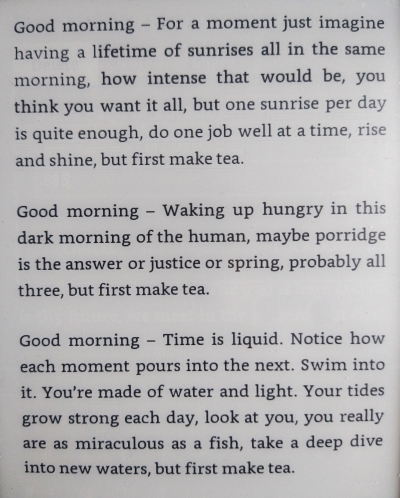

An excerpt from “But First Make Tea”

(Read via NetGalley) Published in the UK by Canongate Press.

Inconsolable Objects by Nancy Miller Gomez

Nancy Miller Gomez’s debut collection recalls a Midwest girlhood of fairground rides and lake swimming; tornadoes and cicadas. But her remembered Kansas is no site of rose-tinted nostalgia. “Missing History” notes how women’s stories, such as her grandmother’s, are lost to time. A pet snake goes missing and she imagines it haunting her mother. In “Tilt-A-Whirl,” her older sister’s harmless flirtation with a ride operator turns sinister. “Mothering,” likewise, eschews the cosy for images of fierce protection. The poet documents the death of her children’s father and abides with a son enduring brain scans and a daughter in recovery from heroin addiction. She also takes ideas from the headlines, with poems about the Ukraine invasion and species extinction. There is a prison setting in two in a row – she has taught Santa Cruz County Jail poetry workshops. The alliteration and slant rhymes are to die for, and I love the cover (Owl Collage by Alexandra Gallagher) and frequent bird metaphors. This also appeared on my Best Books from the First Half of 2024 list. [My full review is on Goodreads.]

Nancy Miller Gomez’s debut collection recalls a Midwest girlhood of fairground rides and lake swimming; tornadoes and cicadas. But her remembered Kansas is no site of rose-tinted nostalgia. “Missing History” notes how women’s stories, such as her grandmother’s, are lost to time. A pet snake goes missing and she imagines it haunting her mother. In “Tilt-A-Whirl,” her older sister’s harmless flirtation with a ride operator turns sinister. “Mothering,” likewise, eschews the cosy for images of fierce protection. The poet documents the death of her children’s father and abides with a son enduring brain scans and a daughter in recovery from heroin addiction. She also takes ideas from the headlines, with poems about the Ukraine invasion and species extinction. There is a prison setting in two in a row – she has taught Santa Cruz County Jail poetry workshops. The alliteration and slant rhymes are to die for, and I love the cover (Owl Collage by Alexandra Gallagher) and frequent bird metaphors. This also appeared on my Best Books from the First Half of 2024 list. [My full review is on Goodreads.]

With thanks to publicist Sarah Cassavant (Nectar Literary) and YesYes Books for the e-copy for review.

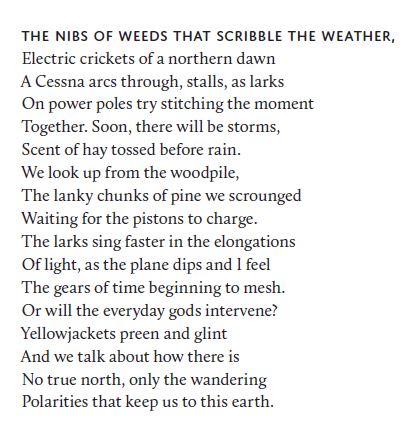

In the Days that Followed by Kevin Goodan

These 41 poems, each limited to one stanza and one page, are named for their first lines, like hymns. With their old-fashioned lyricism and precise nature vocabulary, they are deeply rooted in place and animated by frequent rhetorical questions. Birds and fields, livestock and wildfires: Goodan marks where human interest and the natural world meet, or sometimes clash. He echoes Emily Dickinson (“After great patience, a small bird comes”) and also reminds me of Keith Taylor, whose upcoming collection I’ve reviewed for Shelf Awareness. The pages are rain-soaked and ghost-haunted, creating a slightly melancholy atmosphere. Unusual phrasing and alliteration stand out: “on the field / A fallow calm falls / Leaving the soil / To its feraling.” He’s a new name for me though this is his seventh collection; I’d happily read more. [After I read the book I looked at the blurb on Goodreads. I got … none of that from my reading, so be aware that it’s very subtle.]

These 41 poems, each limited to one stanza and one page, are named for their first lines, like hymns. With their old-fashioned lyricism and precise nature vocabulary, they are deeply rooted in place and animated by frequent rhetorical questions. Birds and fields, livestock and wildfires: Goodan marks where human interest and the natural world meet, or sometimes clash. He echoes Emily Dickinson (“After great patience, a small bird comes”) and also reminds me of Keith Taylor, whose upcoming collection I’ve reviewed for Shelf Awareness. The pages are rain-soaked and ghost-haunted, creating a slightly melancholy atmosphere. Unusual phrasing and alliteration stand out: “on the field / A fallow calm falls / Leaving the soil / To its feraling.” He’s a new name for me though this is his seventh collection; I’d happily read more. [After I read the book I looked at the blurb on Goodreads. I got … none of that from my reading, so be aware that it’s very subtle.]

With thanks to Alice James Books for the e-copy for review.

From Base Materials by Jenny Lewis

This nicely ties together many of the themes covered by the other collections I’ve discussed: science and nature imagery, ageing, and social justice pleas. But Lewis adds in another major topic: language itself, by way of etymology and translation. “Another Way of Saying It” gives the origin of all but incidental words in parentheses. The “Tales from Mesopotamia” are from a commissioned verse play she wrote and connect back to her 2014 collection Taking Mesopotamia, with its sequence inspired by The Epic of Gilgamesh. There are also translations from the Arabic and a long section paraphrases the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, which recalls the books of Ecclesiastes and Job with its self-help aphorisms. Other poems are inspired by a mastectomy, Julian of Norwich, Japanese phrases, and Arthurian legend. The title phrase comes from the Rubaiyat and refers to the creation of humanity from clay. There’s such variety of subject matter here, but always curiosity and loving attention.

This nicely ties together many of the themes covered by the other collections I’ve discussed: science and nature imagery, ageing, and social justice pleas. But Lewis adds in another major topic: language itself, by way of etymology and translation. “Another Way of Saying It” gives the origin of all but incidental words in parentheses. The “Tales from Mesopotamia” are from a commissioned verse play she wrote and connect back to her 2014 collection Taking Mesopotamia, with its sequence inspired by The Epic of Gilgamesh. There are also translations from the Arabic and a long section paraphrases the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, which recalls the books of Ecclesiastes and Job with its self-help aphorisms. Other poems are inspired by a mastectomy, Julian of Norwich, Japanese phrases, and Arthurian legend. The title phrase comes from the Rubaiyat and refers to the creation of humanity from clay. There’s such variety of subject matter here, but always curiosity and loving attention.

“On Translation”

The trouble with translating, for me, is that

when I’ve finished, my own words won’t come;

like unloved step-children in a second marriage,

they hang back at table, knowing their place.

While their favoured siblings hold forth, take

centre stage, mine remain faint, out of ear-shot

like Miranda on her island shore before the boats

came near enough, signalling a lost language;

and always the boom of another surf – pounding,

subterranean, masculine, urgent – makes my words

dither and flit, become little and scattered

like flickering shoals caught up in the slipstream

of a whale, small as sand crabs at the bottom of a bucket,

harmless; transparent as zooplankton.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the e-copy for review.

The Shark Nursery by Mary O’Malley

This was my first time reading Irish poet Mary O’Malley. Nature looms large in her tenth collection, as in several of the other books I’ve reviewed here, with poems about flora and fauna. “Late Swallow” is a highlight (“your loops and dives leave ripples in the air, / a winged Matisse, painting with scissors”) and the title’s reference is to dogfish – what’s in a name, eh? The meticulous detail in her descriptions made me think of still lifes, as did a mention of an odalisque. Other verse is stimulated by Greek myth, travel to Lisbon, and the Gaelic language. Sections are devoted to pandemic experiences (“Another Plague Season”) and to technology. “The Dig” imagines what future archaeologists will make of our media. I noted end and internal rhymes in “April” and the repeated sounds and pattern of stress of “clean as a quiver of knives.” O’Malley has a light touch but leaves a big impression.

This was my first time reading Irish poet Mary O’Malley. Nature looms large in her tenth collection, as in several of the other books I’ve reviewed here, with poems about flora and fauna. “Late Swallow” is a highlight (“your loops and dives leave ripples in the air, / a winged Matisse, painting with scissors”) and the title’s reference is to dogfish – what’s in a name, eh? The meticulous detail in her descriptions made me think of still lifes, as did a mention of an odalisque. Other verse is stimulated by Greek myth, travel to Lisbon, and the Gaelic language. Sections are devoted to pandemic experiences (“Another Plague Season”) and to technology. “The Dig” imagines what future archaeologists will make of our media. I noted end and internal rhymes in “April” and the repeated sounds and pattern of stress of “clean as a quiver of knives.” O’Malley has a light touch but leaves a big impression.

“Holy”

The days lengthen, the sky quickens.

Something invisible flows in the sticks

and they blossom. We learn to let this

be enough. It isn’t; it’s enough to go on.

Then a lull and a clip on my phone

of a small girl playing with a tennis ball

her three-year-old face a chalice brimming

with life, and I promise when all this is over

I will remember what is holy. I will say

the word without shame, and ask if God

was his own fable to help us bear absence,

the cold space at the heart of the atom.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the e-copy for review.

Why four main characters? Why is it the one non-Nigerian who’s poor, victimized, and less proficient in English? (That Kadiatou is based on a real person doesn’t explain enough. Her plight does at least provide what plot there is.) Why are the other three, to varying extents, rich and pretentious? Why are two narratives in the first person and two in the third person? Why in such long chunks instead of switching the POV more often? Why so many men, all of them more or less useless? (All these heterosexual relationships – so boring!) Why bring Covid into it apart from for verisimilitude? But why is the point in time important? What point is she trying to convey about pornography, the subject of Omelogor’s research?

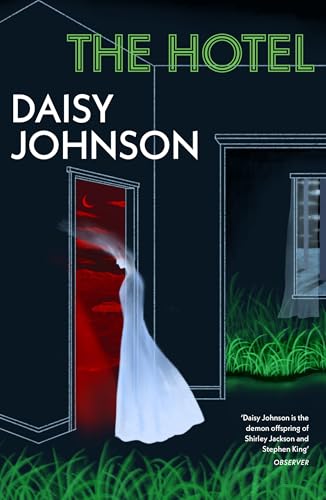

Why four main characters? Why is it the one non-Nigerian who’s poor, victimized, and less proficient in English? (That Kadiatou is based on a real person doesn’t explain enough. Her plight does at least provide what plot there is.) Why are the other three, to varying extents, rich and pretentious? Why are two narratives in the first person and two in the third person? Why in such long chunks instead of switching the POV more often? Why so many men, all of them more or less useless? (All these heterosexual relationships – so boring!) Why bring Covid into it apart from for verisimilitude? But why is the point in time important? What point is she trying to convey about pornography, the subject of Omelogor’s research? The Hotel is a fenland folly, built on the site of a pond where a suspected witch was drowned. Ever after, it is a cursed place. Those who build the hotel and stay in it are subject to violence, fear, and eruptions of the unexplained – especially if they go in Room 63. Anyone who visits once seems doomed to return. Most of the stories are in the first person, which makes sense for dramatic monologues. The speakers are guests, employees, and monsters. Some are BIPOC or queer, as if to tick off demographic boxes. Just before the Hotel burns down in 2019, it becomes the subject of an amateur student film like The Blair Witch Project.

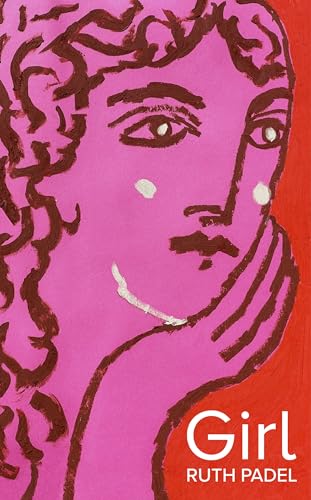

The Hotel is a fenland folly, built on the site of a pond where a suspected witch was drowned. Ever after, it is a cursed place. Those who build the hotel and stay in it are subject to violence, fear, and eruptions of the unexplained – especially if they go in Room 63. Anyone who visits once seems doomed to return. Most of the stories are in the first person, which makes sense for dramatic monologues. The speakers are guests, employees, and monsters. Some are BIPOC or queer, as if to tick off demographic boxes. Just before the Hotel burns down in 2019, it becomes the subject of an amateur student film like The Blair Witch Project. The first section, “When the Angel Comes for You,” is about the Virgin Mary, its 15 poems corresponding to the 15 Mysteries of the Rosary (as Padel explains in a note at the end; had she not, that would have gone over my head). The opening poem about the Annunciation is the most memorable its contemporary imagery emphasizing Mary’s youth and naivete: “a flood of real fear / and your heart / in the cowl-neck T-shirt from Primark / suddenly convulsed. But your old life // now seems dry as a stubbed / cigarette.” The third section, “Lady of the Labyrinth,” is about Ariadne, inspired by the snake goddess figurines in a museum on Crete. The message here is the same: “there is always the question of power / and girl is a trajectory / of learning how to deal with it”.

The first section, “When the Angel Comes for You,” is about the Virgin Mary, its 15 poems corresponding to the 15 Mysteries of the Rosary (as Padel explains in a note at the end; had she not, that would have gone over my head). The opening poem about the Annunciation is the most memorable its contemporary imagery emphasizing Mary’s youth and naivete: “a flood of real fear / and your heart / in the cowl-neck T-shirt from Primark / suddenly convulsed. But your old life // now seems dry as a stubbed / cigarette.” The third section, “Lady of the Labyrinth,” is about Ariadne, inspired by the snake goddess figurines in a museum on Crete. The message here is the same: “there is always the question of power / and girl is a trajectory / of learning how to deal with it”. Also present are Maya, Jamie’s girlfriend; Rocky’s ageing parents; and Chicken the cat (can you imagine taking your cat on holiday?!). With such close quarters, it’s impossible to keep secrets. Over the week of merry eating and drinking, much swimming, and plenty of no-holds-barred conversations, some major drama emerges via both the oldies and the youngsters. And it’s not just present crises; the past is always with Rocky. Cape Cod has developed layers of emotional memories for her. She’s simultaneously nostalgic for her kids’ babyhood and delighted with the confident, intelligent grown-ups they’ve become. She’s grateful for the family she has, but also haunted by inherited trauma and pregnancy loss.

Also present are Maya, Jamie’s girlfriend; Rocky’s ageing parents; and Chicken the cat (can you imagine taking your cat on holiday?!). With such close quarters, it’s impossible to keep secrets. Over the week of merry eating and drinking, much swimming, and plenty of no-holds-barred conversations, some major drama emerges via both the oldies and the youngsters. And it’s not just present crises; the past is always with Rocky. Cape Cod has developed layers of emotional memories for her. She’s simultaneously nostalgic for her kids’ babyhood and delighted with the confident, intelligent grown-ups they’ve become. She’s grateful for the family she has, but also haunted by inherited trauma and pregnancy loss.