Book Serendipity, September through Mid-November

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away.

Thanks to Emma and Kay for posting their own Book Serendipity moments! (Liz is always good about mentioning them as she goes along, in the text of her reviews.)

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- An obsession with Judy Garland in My Judy Garland Life by Susie Boyt (no surprise there), which I read back in January, and then again in Beard: A Memoir of a Marriage by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

- Leaving a suicide note hinting at drowning oneself before disappearing in World War II Berlin; and pretending to be Jewish to gain better treatment in Aimée and Jaguar by Erica Fischer and The Lilac People by Milo Todd.

- Leaving one’s clothes on a bank to suggest drowning in The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese, read over the summer, and then Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet.

- A man expecting his wife to ‘save’ him in Amanda by H.S. Cross and Beard: A Memoir of a Marriage by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

A man tells his story of being bullied as a child in Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood and Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

A man tells his story of being bullied as a child in Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood and Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

- References to Vincent Minnelli and Walt Whitman in a story from Touchy Subjects by Emma Donoghue and Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

- The prospect of having one’s grandparents’ dining table in a tiny city apartment in Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist and Wreck by Catherine Newman.

- Ezra Pound’s dodgy ideology was an element in The Dime Museum by Joyce Hinnefeld, which I reviewed over the summer, and recurs in Swann by Carol Shields.

- A character has heart palpitations in Andrew Miller’s story from The BBC National Short Story Award 2025 anthology and Endling by Maria Reva.

- A (semi-)nude man sees a worker outside the window and closes the curtains in one story of Cathedral by Raymond Carver and one from Good and Evil and Other Stories by Samanta Schweblin.

- The call of the cuckoo is mentioned in The Edge of Silence by Neil Ansell and Of All that Ends by Günter Grass.

A couple in Italy who have a Fiat in Of All that Ends by Günter Grass and Caoilinn Hughes’s story from The BBC National Short Story Award 2025 anthology.

A couple in Italy who have a Fiat in Of All that Ends by Günter Grass and Caoilinn Hughes’s story from The BBC National Short Story Award 2025 anthology.

- Balzac’s excessive coffee consumption was mentioned in Au Revoir, Tristesse by Viv Groskop, one of my 20 Books of Summer, and then again in The Writer’s Table by Valerie Stivers.

- The main character is rescued from her suicide plan by a madcap idea in The Wedding People by Alison Espach and Endling by Maria Reva.

- The protagonist is taking methotrexate in Sea, Poison by Caren Beilin and Wreck by Catherine Newman.

- A man wears a top hat in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and one story of Cathedral by Raymond Carver.

- A man named Angus is the murderer in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and Swann by Carol Shields.

The thing most noticed about a woman is a hair on her chin in the story “Pluck” in Touchy Subjects by Emma Donoghue and Swann by Carol Shields.

The thing most noticed about a woman is a hair on her chin in the story “Pluck” in Touchy Subjects by Emma Donoghue and Swann by Carol Shields.

- The female main character makes a point of saying she doesn’t wear a bra in Sea, Poison by Caren Beilin and Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

- A home hairdressing business in one story of Cathedral by Raymond Carver and Emil & the Detectives by Erich Kästner.

- Painting a bathroom fixture red: a bathtub in The Diary of a Nobody by George Grossmith, one of my 20 Books of Summer; and a toilet in Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

- A teenager who loses a leg in a road accident in individual stories from A Wild Swan by Michael Cunningham and the Racket anthology (ed. Lisa Moore).

- Digging up the casket of a loved one in the wee hours features in Pet Sematary by Stephen King, one of my 20 Books of Summer; and one story of Pretty Monsters by Kelly Link.

- A character named Dani in the story “The St. Alwynn Girls at Sea” by Sheila Heti and The Silver Book by Olivia Laing; later, author Dani Netherclift (Vessel).

Obsessive cultivation of potatoes in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and The Martian by Andy Weir.

Obsessive cultivation of potatoes in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and The Martian by Andy Weir.

- The story of Dante Gabriel Rossetti digging up the poems he buried with his love is recounted in Sharon Bala’s story in the Racket anthology (ed. Lisa Moore) and one of the stories in Pretty Monsters by Kelly Link.

- Putting French word labels on objects in Alone in the Classroom by Elizabeth Hay and Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

A man with part of his finger missing in Find Him! by Elaine Kraf and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

A man with part of his finger missing in Find Him! by Elaine Kraf and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

- In Minor Black Figures by Brandon Taylor, I came across a mention of the Italian film director Pier Paolo Pasolini, who is a character in The Silver Book by Olivia Laing.

- A character who works in an Ohio hardware store in Flashlight by Susan Choi and Buckeye by Patrick Ryan (two one-word-titled doorstoppers I skimmed from the library). There’s also a family-owned hardware store in Alone in the Classroom by Elizabeth Hay.

- A drowned father – I feel like drownings in general happen much more often in fiction than they do in real life – in The Homecoming by Zoë Apostolides, Flashlight by Susan Choi, and Vessel by Dani Netherclift (as well as multiple drownings in The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese, one of my 20 Books of Summer).

- A memoir by a British man who’s hard of hearing but has resisted wearing hearing aids in the past: first The Quiet Ear by Raymond Antrobus over the summer, then The Edge of Silence by Neil Ansell.

A loved one is given a six-month cancer prognosis but lives another (nearly) two years in All the Way to the River by Elizabeth Gilbert and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

A loved one is given a six-month cancer prognosis but lives another (nearly) two years in All the Way to the River by Elizabeth Gilbert and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

- A man’s brain tumour is diagnosed by accident while he’s in hospital after an unrelated accident in Flashlight by Susan Choi and Saltwash by Andrew Michael Hurley.

- Famous lost poems in What We Can Know by Ian McEwan and Swann by Carol Shields.

- A description of the anatomy of the ear and how sound vibrates against tiny bones in The Edge of Silence by Neil Ansell and What Stalks the Deep by T. Kingfisher.

- Notes on how to make decadent mashed potatoes in Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist, Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry, and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

- Transplant surgery on a dog in Russia and trepanning appear in The Heart of a Dog by Mikhail Bulgakov and the poetry collection Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung.

- Audre Lorde, whose Sister Outsider I was reading at the time, is mentioned in Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl. Lorde’s line about the master’s tools never dismantling the master’s house is also paraphrased in Spent by Alison Bechdel.

- An adult appears as if fully formed in a man’s apartment but needs to be taught everything, including language and toilet training, in The Heart of a Dog by Mikhail Bulgakov and Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

Two sisters who each wrote a memoir about their upbringing in Spent by Alison Bechdel and Vessel by Dani Netherclift.

Two sisters who each wrote a memoir about their upbringing in Spent by Alison Bechdel and Vessel by Dani Netherclift.

- The fact that ragwort is bad for horses if it gets mixed up into their feed was mentioned in Ghosts of the Farm by Nicola Chester and Understorey by Anna Chapman Parker.

- The Sylvia Plath line “the O-gape of complete despair” was mentioned in Vessel by Dani Netherclift, then I read it in its original place in Ariel later the same day.

- A mention of the Baba Yaga folk tale (an old woman who lives in the forest in a hut on chicken legs) in Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung and Woman, Eating by Claire Kohda. [There was a copy of Sophie Anderson’s children’s book The House with Chicken Legs in the Little Free Library around that time, too.]

- Coming across a bird that seems to have simply dropped dead in Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito, Vessel by Dani Netherclift, and Rainforest by Michelle Paver.

- Contemplating a mound of hair in Vessel by Dani Netherclift (at Auschwitz) and Year of the Water Horse by Janice Page (at a hairdresser’s).

- Family members are warned that they should not see the body of their loved one in Vessel by Dani Netherclift and Rainforest by Michelle Paver.

- A father(-in-law)’s swift death from oesophageal cancer in Year of the Water Horse by Janice Page and Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry.

- I saw John Keats’s concept of negative capability discussed first in My Little Donkey by Martha Cooley and then in Understorey by Anna Chapman Parker.

- I started two books with an Anne Sexton epigraph on the same day: A Portable Shelter by Kirsty Logan and Slags by Emma Jane Unsworth.

- Mentions of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination in Q’s Legacy by Helene Hanff and Sister Outsider for Audre Lorde, both of which I was reading for Novellas in November.

- Mentions of specific incidents from Samuel Pepys’s diary in Q’s Legacy by Helene Hanff and Gin by Shonna Milliken Humphrey, both of which I was reading for Nonfiction November/Novellas in November.

- Starseed (aliens living on earth in human form) in Beautyland by Marie-Helene Bertino and The Conspiracists by Noelle Cook.

- Reading nonfiction by two long-time New Yorker writers at the same time: Life on a Little-Known Planet by Elizabeth Kolbert and Joyride by Susan Orlean.

- The breaking of a mirror seems like a bad omen in The Spare Room by Helen Garner and The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath.

The author’s husband (who has a name beginning with P) is having an affair with a lawyer in Catching Sight by Deni Elliott and Joyride by Susan Orlean.

The author’s husband (who has a name beginning with P) is having an affair with a lawyer in Catching Sight by Deni Elliott and Joyride by Susan Orlean.

- Mentions of Lewis Hyde’s book The Gift in Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl and The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer; I promptly ordered the Hyde secondhand!

- The protagonist fears being/is accused of trying to steal someone else’s cat in Minka and Curdy by Antonia White and Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen by P.G. Wodehouse, both of which I was reading for Novellas in November.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Book Serendipity, Mid-February to Mid-April

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. The following are in roughly chronological order.

Last time, my biggest set of coincidences was around books set in or about Korea or by Korean authors; this time it was Ghana and Ghanaian authors:

- Reading two books set in Ghana at the same time: Fledgling by Hannah Bourne-Taylor and His Only Wife by Peace Adzo Medie. I had also read a third book set in Ghana, What Napoleon Could Not Do by DK Nnuro, early in the year and then found its title phrase (i.e., “you have done what Napoleon could not do,” an expression of praise) quoted in the Medie! It must be a popular saying there.

- Reading two books by young Ghanaian British authors at the same time: Quiet by Victoria Adukwei Bulley and Maame by Jessica George.

And the rest:

- An overweight male character with gout in Where the God of Love Hangs Out by Amy Bloom and The Secret Diaries of Charles Ignatius Sancho by Paterson Joseph.

- I’d never heard of “shoegaze music” before I saw it in Michelle Zauner’s bio at the back of Crying in H Mart, but then I also saw it mentioned in Pulling the Chariot of the Sun by Shane McCrae.

- Sheila Heti’s writing on motherhood is quoted in Without Children by Peggy O’Donnell Heffington and In Vitro by Isabel Zapata. Before long I got back into her novel Pure Colour. A quote from another of her books (How Should a Person Be?) is one of the epigraphs to Lorrie Moore’s I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home.

- Reading two Mexican books about motherhood at the same time: Still Born by Guadalupe Nettel and In Vitro by Isabel Zapata.

- Two coming-of-age novels set on the cusp of war in 1939: The Inner Circle by T.C. Boyle and Martha Quest by Doris Lessing.

- A scene of looking at peculiar human behaviour and imagining how David Attenborough would narrate it in a documentary in Notes from a Small Island by Bill Bryson and I Have Some Questions for You by Rebecca Makkai.

- The painter Caravaggio is mentioned in a novel (The Things We Do to Our Friends by Heather Darwent) plus two poetry books (The Fourth Sister by Laura Scott and Manorism by Yomi Sode) I was reading at the same time.

- Characters are plagued by mosquitoes in The Last Animal by Ramona Ausubel and Through the Groves by Anne Hull.

- Edinburgh’s history of grave robbing is mentioned in The Things We Do to Our Friends by Heather Darwent and Womb by Leah Hazard.

- I read a chapter about mayflies in Lev Parikian’s book Taking Flight and then a poem about mayflies later the same day in Ephemeron by Fiona Benson.

- Childhood reminiscences about playing the board game Operation and wetting the bed appear in Homesick by Jennifer Croft and Through the Groves by Anne Hull.

- Fiddler on the Roof songs are mentioned in Through the Groves by Anne Hull and We All Want Impossible Things by Catherine Newman.

- There’s a minor character named Frith in Shadow Girls by Carol Birch and Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier.

- Scenes of a female couple snogging in a bar bathroom in Through the Groves by Anne Hull and The Garnett Girls by Georgina Moore.

- The main character regrets not spending more time with her father before his sudden death in Maame by Jessica George and Pure Colour by Sheila Heti.

- The main character is called Mira in Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton and Pure Colour by Sheila Heti, and a Mira is briefly mentioned in one of the stories in Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self by Danielle Evans.

- Macbeth references in Shadow Girls by Carol Birch and Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton – my second Macbeth-sourced title in recent times, after Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin last year.

- A ‘Goldilocks scenario’ is referred to in Womb by Leah Hazard (the ideal contraction strength) and Taking Flight by Lev Parikian (the ideal body weight for a bird).

- Caribbean patois and mention of an ackee tree in the short story collection If I Survive You by Jonathan Escoffery and the poetry collection Cane, Corn & Gully by Safiya Kamaria Kinshasa.

- The Japanese folktale “The Boy Who Drew Cats” appeared in Our Missing Hearts by Celeste Ng, which I read last year, and then also in Enchantment by Katherine May.

- Chinese characters are mentioned to have taken part in the Tiananmen Square massacre/June 4th incident in Dear Chrysanthemums by Fiona Sze-Lorrain and Oh My Mother! by Connie Wang.

- Endometriosis comes up in What My Bones Know by Stephanie Foo and Womb by Leah Hazard.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

20 Books of Summer, #16–17, GREEN: Jon Dunn and W.H. Hudson

Today’s entries in my colour-themed summer reading are a travelogue tracking the world’s endangered hummingbirds and a bizarre classic novel that blends nature writing and fantasy. Though very different books, they have in common lush South American forest settings.

The Glitter in the Green: In Search of Hummingbirds by Jon Dunn (2021)

As a wildlife writer and photographer, Jon Dunn has come to focus on small and secretive but indelible wonders. His previous book, which I still need to catch up on, was all about orchids, and in this new one he travels the length of the Americas, from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego, to see as many hummingbirds as he can. He provides a thorough survey of the history, science and cultural relevance (from a mini handgun to an indie pop band) of this most jewel-like of bird families. The ruby-throated hummingbirds I grew up seeing in suburban Maryland are gorgeous enough, but from there the names and corresponding colourful markings just get more magnificent: Glittering-throated Emeralds, Tourmaline Sunangels, Violet-capped woodnymphs, and so on. I’ll have to get a look at the photos in a finished copy of the book!

Dunn is equally good at describing birds and their habitats and at constructing a charming travelogue out of his sometimes fraught journeys. He has only a narrow weather of fog-free weather to get from Chile to Isla Robinson Crusoe and the plane has to turn back once before it successfully lands; a planned excursion in Bolivia is a non-starter after political protestors block some main routes. There are moments when the thrill of the chase is rewarded – as when he sees 24 hummingbird species in a day in Costa Rica – and many instances of lavish hospitality from locals who serve as guides or open their gardens to birdwatchers.

Dunn is equally good at describing birds and their habitats and at constructing a charming travelogue out of his sometimes fraught journeys. He has only a narrow weather of fog-free weather to get from Chile to Isla Robinson Crusoe and the plane has to turn back once before it successfully lands; a planned excursion in Bolivia is a non-starter after political protestors block some main routes. There are moments when the thrill of the chase is rewarded – as when he sees 24 hummingbird species in a day in Costa Rica – and many instances of lavish hospitality from locals who serve as guides or open their gardens to birdwatchers.

Like so many creatures, hummingbirds are in dire straits due to human activity: deforestation, invasive species, pesticide use and climate change are reducing the areas where they can live to pockets here and there; some species number in the hundreds and are considered critically endangered. Dunn juxtaposes the exploitative practices of (white, male) 19th- and 20th-century bird artists, collectors and hunters with indigenous birdwatching and environmental initiatives that are rising up to combat ecological damage in Latin America. Although society has moved past the use of hummingbird feathers in crafts and fashion, he learns that the troubling practice of dead hummingbirds being sold as love charms (chuparosas) persists in Mexico.

Whether you’re familiar with hummingbirds or not, if you have even a passing interest in nature and travel writing, I recommend The Glitter in the Green for how it invites readers into a personal passion, recreates an adventurous odyssey, and reinforces our collective responsibility for threatened wildlife. (Proof copy passed on by Paul of Halfman, Halfbook)

A lovely folk tale I’ll quote in full:

A hummingbird as a symbol of hope, strength and endurance is a recurrent one in South American folklore. An Ecuadorian folk tale tells of a forest on fire – a hummingbird picks up single droplets of water in its beak and lets them fall on the fire. The other animals in the forest laugh, and ask the hummingbird what difference this can possibly make. They say, ‘Don’t bother, it is too much, you are too little, your wings will burn, your beak is too tiny, it’s only a drop, you can’t put out this fire. What do you think you are doing?’ To which the hummingbird is said to reply, ‘I’m just doing what I can.’

Links between the books: Hudson is quoted in Dunn’s introduction. In Chapter 7 of the below, Hudson describes a hummingbird as “a living prismatic gem that changes its colour with every change of position … it catches the sunshine on its burnished neck and gorget plumes—green and gold and flame-coloured, the beams changing to visible flakes as they fall”

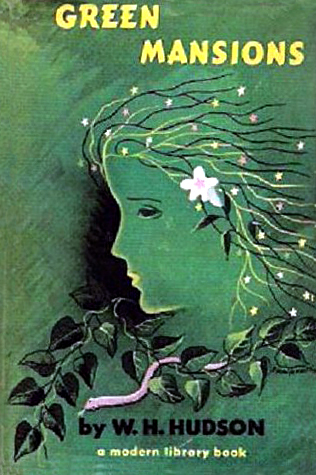

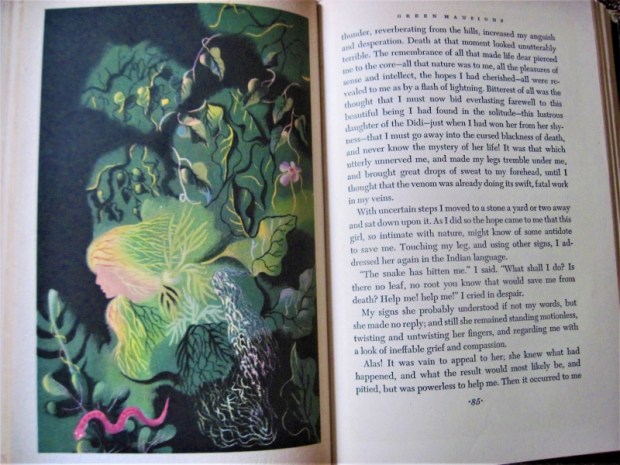

Green Mansions: A Romance of the Tropical Forest by W.H. Hudson (1904)

Like Heart of Darkness, this is a long recounted tale about a journey among ‘savages’. After a prologue, the narrator soon cedes storytelling duties to Mr. Abel, whom he met in Georgetown, Guyana in 1887. Searching for gold and fighting off illness, the 23-year-old Abel took up the habit of wandering the Venezuelan forest. The indigenous people were superstitious and refused to hunt in that forest. Abel began to hear strange noises – magical bird calls or laughter – that, siren-like, drew him deeper in. His native friend warned him it was the daughter of an evil spirit.

Like Heart of Darkness, this is a long recounted tale about a journey among ‘savages’. After a prologue, the narrator soon cedes storytelling duties to Mr. Abel, whom he met in Georgetown, Guyana in 1887. Searching for gold and fighting off illness, the 23-year-old Abel took up the habit of wandering the Venezuelan forest. The indigenous people were superstitious and refused to hunt in that forest. Abel began to hear strange noises – magical bird calls or laughter – that, siren-like, drew him deeper in. His native friend warned him it was the daughter of an evil spirit.

One day, after being bitten by a snake, Abel woke up in the dwelling of an old man and his 17-year-old granddaughter, Rima – the very wood sprite he’d sensed all these times in the forest; she saved his life. Recovering in their home and helping Rima investigate her origins, he romanticizes this tree spirit in a way that struck me as smarmy. It’s possible this could be appreciated as a fable of connection with nature, but I found it vague and old-fashioned. (Not to mention Abel’s condescending attitude to the indigenous people and to women.) I ended up skimming the last three-quarters.

My husband has read nonfiction by Hudson; I think I was under the impression that this was a memoir, in fact. Perhaps I’d enjoy Hudson’s writing in another genre. But I was surprised to read high praise from John Galsworthy in the foreword (“For of all living authors—now that Tolstoi has gone—I could least dispense with W. H. Hudson”) and to note how many of my Goodreads friends have read this; I don’t see it as a classic that stands the test of time.

My 1944 hardback once belonged to one Mary Marcilliat of Louisville, Kentucky, and has strange abstract illustrations by E. McKnight Kauffer. (Free from the Book Thing of Baltimore)

Coming up next: One black and one gold on Wednesday; a Green author and a rainbow bonus (probably on the very last day).

Would you be interested in reading one of these?

Three Out-of-the-Ordinary Memoirs: Kalb, Machado, McGuinness

Recently I have found myself drawn to memoirs that experiment with form. I’ve read so many autobiographical narratives at this point that, if it’s to stand out for me, a book has to offer something different, such as a second-person point-of-view or a structure of linked essays. Here are a few such that I’ve read this year but not written about yet. All have strong themes of memory and the creation of the self or the family.

Nobody Will Tell You This But Me: A True (As Told to Me) Story by Bess Kalb (2020)

You know from the jokes: Jewish (grand)mothers are renowned for their fiercely protective, unconditional love, but also for their tendency to nag. Both sides of a stereotypical matriarch are on display in this funny and heartfelt family memoir, narrated in the second person – as if straight to Kalb from beyond the grave – by her late grandmother, Barbara “Bobby” Bell.

You know from the jokes: Jewish (grand)mothers are renowned for their fiercely protective, unconditional love, but also for their tendency to nag. Both sides of a stereotypical matriarch are on display in this funny and heartfelt family memoir, narrated in the second person – as if straight to Kalb from beyond the grave – by her late grandmother, Barbara “Bobby” Bell.

Bobby gives her beloved Bessie a tour through four generations of strong women, starting with her own mother, Rose, and her lucky escape from a Belarus shtetl. The formidable émigré ended up in a tiny Brooklyn apartment, where she gave birth to five children on the dining room table. Bobby and her husband, a real estate entrepreneur and professor, had one daughter, Robin, who in turn had one daughter, Bess. Bobby and Robin had a fraught relationship, but Bess’s birth seemed to reset the clock. Grandmother and granddaughter had a special bond: Bobby was the one to take her to preschool and wait outside the door until she was sure she’d be okay, and always the one to pick her up from sleepovers gone wrong.

Kalb is a Los Angeles-based writer for Jimmy Kimmel Live! With her vivid scene-setting and comic timing, you can see why she’s earned a Writers Guild Award and an Emmy nomination. But she also had great material to work with: Bobby’s e-mails and verbatim voicemail messages are hilarious. Kalb dots in family photographs and recreates in-person and phone conversations, with her grandmother forthrightly questioning her fashion choices and non-Jewish boyfriend. As the title phrase shows, Bobby felt she was the only one who would come forward with all this (unwanted but) necessary advice. Kalb keeps things snappy, alternating between narrative chapters and the conversations and covering a huge amount of family history in just 200 pages. It gets a little sentimental towards the end, but with her grandmother’s death still fresh you can forgive her that. This was a real delight.

My rating:

My thanks to Zoe Hood and Kimberley Nyamhondera of Little, Brown (Virago) for the free PDF copy for review.

In the Dream House: A Memoir by Carmen Maria Machado (2019)

I’m stingy with 5-star ratings because, for me, giving a book top marks means a) it’s a masterpiece, b) it’s a game/mind/life changer, and/or c) it expands the possibilities of its particular genre. In the Dream House fits all three criteria. (Somewhat to my surprise, given that I couldn’t get through more than half of Machado’s acclaimed story collection, Her Body and Other Parties, and only enjoyed it in parts.)

Much has been written about this memoir of an abusive same-sex relationship since its U.S. release in November. I feel I have little to add to the conversation beyond my deepest admiration for how it prioritizes voice, theme and scenes; gleefully does away with the chronology and (not directly relevant) backstory – in other words, the boring bits – that most writers would so slavishly detail; and engages with history, critical theory and the tropes of folk tales to constantly interrogate her experiences and perceptions.

Most of the book is, like the Kalb, in the second person, but in this case the narration is not addressing a specific other person; instead, it’s looking back at the self that was caught in this situation (“If, one day, a milky portal had opened up in your bedroom and an older version of yourself had stepped out and told you what you know now, would you have listened?”), as well as – what the second person does best – putting the reader right into the narrative.

Most of the book is, like the Kalb, in the second person, but in this case the narration is not addressing a specific other person; instead, it’s looking back at the self that was caught in this situation (“If, one day, a milky portal had opened up in your bedroom and an older version of yourself had stepped out and told you what you know now, would you have listened?”), as well as – what the second person does best – putting the reader right into the narrative.

The “Dream House” is the Victorian house where Machado lived with her ex-girlfriend in Bloomington, Indiana for two years while she started an MFA course. It was a paradise until it wasn’t; it was a perfect relationship until it wasn’t. No one, least of all her, would have believed the perky little blonde writer she fell for would turn sadistic. A lot of it was emotional manipulation and verbal and psychological abuse, but there was definitely a physical element as well. Fear and self-doubt kept her trapped in a fairy tale that had long since turned into a nightmare. Writing it all out seven years later, the trauma was still there. Yet there was no tangible evidence (a police report, a restraining order, photos of bruises) to site her abuse anywhere outside of her memory. How fleeting, yet indelible, it had all been.

The book is in relatively short sections headed “Dream House as _________” (fill in the blank with everything from “Time Travel” to “Confession”), and the way that she pecks at her memories from different angles is perfect for recreating the spiral of confusion and despair. She also examines the history of our understanding of queer domestic violence: lesbian domestic violence, specifically, wasn’t known about until 30-some years ago.

The story has a happy ending in that Machado is now happily married. The bizarre twist, though, is that her wife, YA author Val Howlett, was the girlfriend of the woman in the Dream House when they first met. To start with, it was an “open relationship” (or at least the blonde told her so) that Machado reluctantly got in the middle of, before Val drifted away. That the two of them managed to reconnect, and got past their mutual ex, is truly astonishing. (See some super-cute photos from their wedding here.)

Some favorite lines:

“Clarity is an intoxicating drug, and you spent almost two years without it, believing you were losing your mind”

“That there’s a real ending to anything is, I’m pretty sure, the lie of all autobiographical writing. You have to choose to stop somewhere. You have to let the reader go.”

My rating:

I read an e-copy via NetGalley.

Other People’s Countries: A Journey into Memory by Patrick McGuinness (2014)

This is a wonderfully atmospheric tribute to Bouillon, Belgium, a Wallonian border town with its own patois. However, it’s chiefly a memoir about the maternal side of the author’s family, which had lived there for generations. McGuinness grew up spending summers in Bouillon with his grandparents and aunt. Returning to the place as an adult, he finds it half-derelict but still storing memories around every corner.

It is as much a tour through memory as through a town, reflecting on how our memories are bound up with particular sites and objects – to the extent that I don’t think I would find McGuinness’s Bouillon even if I went back to Belgium. “When I’m asked about events in my childhood, about my childhood at all, I think mostly of rooms. I think of times as places, with walls and windows and doors,” he writes. The book is also about the nature of time: Bouillon seems like a place where time stands still or moves more slowly, allowing its residents (including his grandfather, and Paprika, “Bouillon’s laziest man, who held a party to celebrate sixty years on the dole”) a position of smug idleness.

It is as much a tour through memory as through a town, reflecting on how our memories are bound up with particular sites and objects – to the extent that I don’t think I would find McGuinness’s Bouillon even if I went back to Belgium. “When I’m asked about events in my childhood, about my childhood at all, I think mostly of rooms. I think of times as places, with walls and windows and doors,” he writes. The book is also about the nature of time: Bouillon seems like a place where time stands still or moves more slowly, allowing its residents (including his grandfather, and Paprika, “Bouillon’s laziest man, who held a party to celebrate sixty years on the dole”) a position of smug idleness.

The book is in short vignettes, some as short as a paragraph; each is a separate piece with a title that remembers a particular place, event or local character. Some are poems, and there are also recipes and an inventory. The whole is illustrated with frequent period or contemporary black-and-white photographs. It’s an altogether lovely book that overcomes its narrow local interest to say something about how the past remains alive for us.

Some favorite lines:

“that hybrid long-finished but real-time-unfolding present tense … reflects the inside of our lives far better than those three stooges, the past, present and future”

a fantastic last line: “What I want to say is: I misremember all this so vividly it’s as if it only happened yesterday.”

My rating:

I read a public library copy.

Other unusual memoirs I’ve loved and reviewed here:

Notes Made while Falling by Jenn Ashworth (essays, experimental structures)

Notes Made while Falling by Jenn Ashworth (essays, experimental structures)

Winter Journal by Paul Auster (second person)

This Really Isn’t about You by Jean Hannah Edelstein (nonchronological)

Traveling with Ghosts by Shannon Leone Fowler (short sections and time shifts)

The Lost Properties of Love by Sophie Ratcliffe (nonchronological essays)

Any offbeat memoirs you can recommend?

20 Books of Summer, #1–4: Alexis, Haupt, Rutt, Tovey

I was slow to launch into my 20 Books of Summer reading, but have now finally managed to get through my first four books. These include two substitutes: a review copy I hadn’t realized fit in perfectly with my all-animals challenge, and a book I’d started earlier in the year but set aside and wanted to get back into. Three of the four were extremely rewarding; the last was somewhat insubstantial, though I always enjoy reading about cat antics. All have been illuminating about animal intelligence and behavior, and useful for thinking about our place in and duty towards the more-than-human world. Not all of my 20 Books of Summer will have such an explicit focus on nature – some just happen to have an animal in the title or pictured on the cover – but this first batch had a strong linking theme so was a great start.

Fifteen Dogs by André Alexis (2015)

In this modern folk tale with elements of the Book of Job, the gods Apollo and Hermes, drinking in a Toronto tavern, discuss the nature of human intelligence and ponder whether it’s inevitably bound up with suffering. They decide to try an experiment, and make a wager on it. They’ll bestow human intelligence on a set of animals and find out whether the creatures die unhappy. Apollo is willing to bet two years’ personal servitude that they will be even unhappier than humans. Their experimental subjects are the 15 dogs being boarded overnight at a nearby veterinary clinic.

The setup means we’re in for an And Then There Were None type of picking-off of the 15, and some of the deaths are distressing. But strangely – and this is what the gods couldn’t foresee – knowledge of their approaching mortality gives the dogs added dignity. It gives their lives and deaths the weight of Shakespearean tragedy. Although they still do doggy things like establishing dominance structures and eating poop, they also know the joys of language and love. A mutt called Prince composes poetry and jokes. Benjy the beagle learns English well enough to recite the first paragraph of Vanity Fair. A poodle named Majnoun forms a connection with his owner that lasts beyond the grave. The dogs work out who they can trust; they form and dissolve bonds; they have memories and a hope that lives on.

The setup means we’re in for an And Then There Were None type of picking-off of the 15, and some of the deaths are distressing. But strangely – and this is what the gods couldn’t foresee – knowledge of their approaching mortality gives the dogs added dignity. It gives their lives and deaths the weight of Shakespearean tragedy. Although they still do doggy things like establishing dominance structures and eating poop, they also know the joys of language and love. A mutt called Prince composes poetry and jokes. Benjy the beagle learns English well enough to recite the first paragraph of Vanity Fair. A poodle named Majnoun forms a connection with his owner that lasts beyond the grave. The dogs work out who they can trust; they form and dissolve bonds; they have memories and a hope that lives on.

It’s a fascinating and inventive novella, and a fond treatment of the relationship between dogs and humans. When I read in the Author’s Note that the poems all included dogs’ names, I went right back to the beginning to scout them out. I’m intrigued by the fact that this Giller Prize winner is a middle book in a series, and keen to explore the rest of the Trinidanian-Canadian author’s oeuvre.

These next two have a lot in common. For both authors, paying close attention to the natural world – birds, in particular – is a way of coping with environmental and mental health crises.

Crow Planet: Essential Wisdom from the Urban Wilderness by Lyanda Lynn Haupt (2009)

Lyanda Lynn Haupt has worked in bird research and rehabilitation for the Audubon Society and other nature organizations. (I read her first book, Rare Encounters with Ordinary Birds, quite a few years ago.) During a bout of depression, she decided to start paying more attention to the natural world right outside her suburban Seattle window. Crows were a natural place to start. From then on she took binoculars everywhere she went, even on walks to Target. She spent time watching crows’ behavior from a distance or examining them up close – devoting hours to studying a prepared crow skin. She even temporarily took in a broken-legged fledgling she named Charlotte and kept a close eye on the injured bird’s progress in the months after she released it.

Lyanda Lynn Haupt has worked in bird research and rehabilitation for the Audubon Society and other nature organizations. (I read her first book, Rare Encounters with Ordinary Birds, quite a few years ago.) During a bout of depression, she decided to start paying more attention to the natural world right outside her suburban Seattle window. Crows were a natural place to start. From then on she took binoculars everywhere she went, even on walks to Target. She spent time watching crows’ behavior from a distance or examining them up close – devoting hours to studying a prepared crow skin. She even temporarily took in a broken-legged fledgling she named Charlotte and kept a close eye on the injured bird’s progress in the months after she released it.

Were this simply a charming and keenly observed record of bird behavior and one woman’s gradual reawakening to the joys of nature, I would still have loved it. Haupt is a forthright and gently witty writer. But what takes it well beyond your average nature memoir is the bold statement of human responsibility to the environment. I’ve sat through whole conference sessions that try to define what nature is, what the purpose of nature writing is, and so on. Haupt can do it in just a sentence, concisely and effortlessly explaining how to be a naturalist in a time of loss and how to hope even when in possession of all the facts.

A few favorite passages:

“an intimate awareness of the continuity between our lives and the rest of life is the only thing that will truly conserve the earth … When we allow ourselves to think of nature as something out there, we become prey to complacency. If nature is somewhere else, then what we do here doesn’t really matter.”

“I believe strongly that the modern naturalist’s calling includes an element of activism. Naturalists are witnesses to the wild, and necessary bridges between ecological and political ways of knowing. … We join the ‘cloud of witnesses’ who refuse to let the more-than-human world pass unnoticed.”

“here we are, intricate human animals capable of feeling despair over the state of the earth and, simultaneously, joy in its unfolding wildness, no matter how hampered. What are we to do with such a confounding vision? The choices appear to be few. We can deny it, ignore it, go insane with its weight, structure it into a stony ethos with which we beat our friends and ourselves to death—or we can live well in its light.”

The Seafarers: A Journey among Birds by Stephen Rutt (2019)

In 2016 Rutt left his anxiety-inducing life in London in a search for space and silence. He found plenty of both on the Orkney Islands, where he volunteered at the North Ronaldsay bird observatory for seven months. In the few years that followed, the young naturalist travelled the length and breadth of the British Isles – from Skomer to Shetland – courting encounters with seabirds. He’s surrounded by storm petrels one magical night at Mousa Broch; he runs from menacing skuas; he watches eider and terns and kittiwakes along the northeast coast; he returns to Orkney to marvel at gannets and fulmars. Whether it’s their beauty, majesty, resilience, or associations with freedom, such species are for him a particularly life-enhancing segment of nature to spend time around.

In 2016 Rutt left his anxiety-inducing life in London in a search for space and silence. He found plenty of both on the Orkney Islands, where he volunteered at the North Ronaldsay bird observatory for seven months. In the few years that followed, the young naturalist travelled the length and breadth of the British Isles – from Skomer to Shetland – courting encounters with seabirds. He’s surrounded by storm petrels one magical night at Mousa Broch; he runs from menacing skuas; he watches eider and terns and kittiwakes along the northeast coast; he returns to Orkney to marvel at gannets and fulmars. Whether it’s their beauty, majesty, resilience, or associations with freedom, such species are for him a particularly life-enhancing segment of nature to spend time around.

Discussion of the environmental threats that hit seabirds hardest, such as plastic pollution, makes for a timely tie-in to wider conservation issues. Rutt also sees himself as part of a long line of bird-loving travellers, including James Fisher and especially R.M. Lockley, whose stories he weaves in. This is one of the best nature/travel books I’ve read in a long time, especially enjoyable because I’ve been to a lot of the island locations and the elegantly evocative writing, making particularly effective use of varied sentence lengths, brought back to me just what it’s like to be in the far north of Scotland in the midst of an endless summer twilight, a humbled observer as a whole whirlwind of bird life carries on above you.

A favorite passage:

“Gannets nest on the honeycombs of the cliff, in their thousands. They sit in pairs, pointing to the sky, swaying heads. They stir. The scent of the boat’s herring fills the air. They take off, tessellating in a sky that is suddenly as much bird as light. The great skuas lurk.”

My husband also reviewed this, from a birder’s perspective.

With thanks to Elliott & Thompson for the proof copy for review.

The Coming of Saska by Doreen Tovey (1977)

I’ve read four of Tovey’s quaint Siamese cat books now; this was the least worthwhile. It’s partially a matter of false advertising: Saska only turns up for the last 15 pages, as a replacement of sorts for Seeley, who disappeared one morning a year earlier and was never seen again. Over half of the book, in fact, is about a trip Tovey and her husband Charles took to Edmonton, Canada. The Canadian government sponsored them to come over for the Klondike Days festivities, and they also rented a camper and went looking for bears and moose. Mildly amusing mishaps, close shaves, etc. ensue. They then come back and settle into everyday life with their pair of Siamese half-siblings; Saska had the same father as Shebalu. Entertaining enough, but slight, and with far too many ellipses.

I’ve read four of Tovey’s quaint Siamese cat books now; this was the least worthwhile. It’s partially a matter of false advertising: Saska only turns up for the last 15 pages, as a replacement of sorts for Seeley, who disappeared one morning a year earlier and was never seen again. Over half of the book, in fact, is about a trip Tovey and her husband Charles took to Edmonton, Canada. The Canadian government sponsored them to come over for the Klondike Days festivities, and they also rented a camper and went looking for bears and moose. Mildly amusing mishaps, close shaves, etc. ensue. They then come back and settle into everyday life with their pair of Siamese half-siblings; Saska had the same father as Shebalu. Entertaining enough, but slight, and with far too many ellipses.

The Bookshop Band & The June–July Outlook

The Bookshop Band played in an Oxfordshire village 35 minutes’ drive from us yesterday evening. I’ve now seen them four times; I don’t think that quite qualifies me as a groupie, though I do count them among my favorite artists and own their complete discography.

The small church provided great acoustics and an intimate setting, and the set list was a fun mixture of old and new. All of their songs are based on literature: When they were the house band at Mr B’s Emporium of Reading Delights in Bath, they would write two songs based on an author’s new book on the very day that s/he would be making an appearance at the shop in the evening. A combination of slow reading and procrastination, I suppose. You’d never believe it, though, because their songs are intricate and thoughtful, often pulling out moments and ideas from books (at least the ones I’ve read) that never would have occurred to me.

Here’s what they played last night, and which books the songs were based on:

- “Once Upon a Time” – For a radio commission they crafted this compilation of first lines from various books.

- “Cackling Farts” – A day-in-the-life song featuring archaic vocabulary words from Mark Forsyth’s The Horologicon.

- “You Make the Best Plans, Thomas” – Hilary Mantel’s Bring Up the Bodies (one of my absolute favorites of their songs).

- “Why I Travel This Way” – Yann Martel’s The High Mountains of Portugal (I have heard this live once before, but it’s never been recorded).

“Petroc and the Lights” – Patrick Gale’s Notes from an Exhibition (which reminds me that I really need to read it soon!).

“Petroc and the Lights” – Patrick Gale’s Notes from an Exhibition (which reminds me that I really need to read it soon!).- “Dirty Word” – A brand-new song based on Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World; it stemmed from their recent commission to write about banned books for the V&A.

- “How Not to Woo a Woman” – Rachel Joyce’s The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry (it must be a band favorite as they’ve played it every time I’ve seen them).

- “Curious and Curiouser” – Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland.

- “Sanctuary” – A new song they wrote for the launch event at the Bodleian Library for Philip Pullman’s La Belle Sauvage (The Book of Dust, #1).

- “Room for Three” – The other song they wrote for the Pullman event

- “We Are the Foxes” – Ned Beauman’s Glow.

- “Edge of the World” – Emma Hooper’s Etta and Otto and Russell and James.

- “Faith in Weather” – The only one not based on a book; this was inspired by a Central European folktale about seven ravens (another of my absolute favorites).

- “Thirteen Chairs” – Dave Shelton’s Thirteen Chairs (another one they’ve played every time I’ve seen them).

I’m always impressed by Ben and Beth’s musicianship (guitars, ukuleles, cello, harmonium and more), and I also admire how they’ve continued touring intensively despite being new parents. They’re currently on the road for two months, and one-year-old Molly simply comes along for the ride!

A gorgeous sunset as we left the gig last night.

It’ll be a busy week on the blog. I have posts planned for every day through Saturday thanks to Library Checkout, the Iris Murdoch readalong, and various features reflecting on the first half of the year and looking ahead to the second half.

It turns out I’ll be in America for three weeks of July helping my parents pack and move, so I may have to slow down on the 20 Books of Summer challenge, and will almost certainly have to substitute in some books I have in storage over there. (I’m pondering fiction by Laurie Colwin, Hester Kaplan, Antonya Nelson and Julie Orringer; and nonfiction by Joan Anderson, Haven Kimmel and Sarah Vowell.) I have a few books lined up to review for their July release dates, but it’ll be a light month overall.

I’ve found Bloom’s short stories more successful than her novels. This is something of a halfway house: linked short stories (one of which was previously published in

I’ve found Bloom’s short stories more successful than her novels. This is something of a halfway house: linked short stories (one of which was previously published in  The title story opens a collection steeped in the landscape and history of Orkney. Each month we check in with three characters: Jean, who lives with her ailing father at the pub they run; and her two very different suitors, pious Peter and drunken Thorfinn. When she gives birth in December, you have to page back to see that she had encounters with both men in March. Some are playful in this vein or resemble folk tales: a boy playing hooky from school, a distant cousin so hapless as to father three bairns in the same household, and a rundown of the grades of whisky available on the islands. Others with medieval time markers are overwhelmingly bleak, especially “Witch,” about a woman’s trial and execution – and one of two stories set out like a play for voices. I quite liked the flash fiction “The Seller of Silk Shirts,” about a young Sikh man who arrives on the islands, and “The Story of Jorfel Hayforks,” in which a Norwegian man sails to find the man who impregnated his sister and keeps losing a crewman at each stop through improbable accidents. This is an atmospheric book I would have liked to read on location, but few of the individual stories stand out. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

The title story opens a collection steeped in the landscape and history of Orkney. Each month we check in with three characters: Jean, who lives with her ailing father at the pub they run; and her two very different suitors, pious Peter and drunken Thorfinn. When she gives birth in December, you have to page back to see that she had encounters with both men in March. Some are playful in this vein or resemble folk tales: a boy playing hooky from school, a distant cousin so hapless as to father three bairns in the same household, and a rundown of the grades of whisky available on the islands. Others with medieval time markers are overwhelmingly bleak, especially “Witch,” about a woman’s trial and execution – and one of two stories set out like a play for voices. I quite liked the flash fiction “The Seller of Silk Shirts,” about a young Sikh man who arrives on the islands, and “The Story of Jorfel Hayforks,” in which a Norwegian man sails to find the man who impregnated his sister and keeps losing a crewman at each stop through improbable accidents. This is an atmospheric book I would have liked to read on location, but few of the individual stories stand out. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)  Mantel is best remembered for the Wolf Hall trilogy, but her early work includes a number of concise, sharp novels about growing up in the north of England. Carmel McBain attends a Catholic school in Manchester in the 1960s before leaving to study law at the University of London in 1970. In lockstep with her are a couple of friends, including Karina, who is of indeterminate Eastern European extraction and whose tragic Holocaust family history, added to her enduring poverty, always made her an object of pity for Carmel’s mother. But Karina as depicted by Carmel is haughty, even manipulative, and over the years their relationship swings between care and competition. As university students they live on the same corridor and have diverging experiences of schoolwork, romance, and food. “Now, I would not want you to think that this is a story about anorexia,” Carmel says early on, and indeed, she presents her condition as more like forgetting to eat. But then you recall tiny moments from her past when teachers and her mother shamed her for eating, and it’s clear a seed was sown. Carmel and her friends also deal with the results of the new-ish free love era. This is dark but funny, too, with Carmel likening roast parsnips to “ogres’ penises.” Further proof, along with

Mantel is best remembered for the Wolf Hall trilogy, but her early work includes a number of concise, sharp novels about growing up in the north of England. Carmel McBain attends a Catholic school in Manchester in the 1960s before leaving to study law at the University of London in 1970. In lockstep with her are a couple of friends, including Karina, who is of indeterminate Eastern European extraction and whose tragic Holocaust family history, added to her enduring poverty, always made her an object of pity for Carmel’s mother. But Karina as depicted by Carmel is haughty, even manipulative, and over the years their relationship swings between care and competition. As university students they live on the same corridor and have diverging experiences of schoolwork, romance, and food. “Now, I would not want you to think that this is a story about anorexia,” Carmel says early on, and indeed, she presents her condition as more like forgetting to eat. But then you recall tiny moments from her past when teachers and her mother shamed her for eating, and it’s clear a seed was sown. Carmel and her friends also deal with the results of the new-ish free love era. This is dark but funny, too, with Carmel likening roast parsnips to “ogres’ penises.” Further proof, along with  Unexpected Lessons in Love by Bernardine Bishop (2013): I loved Bishop’s

Unexpected Lessons in Love by Bernardine Bishop (2013): I loved Bishop’s  A Rough Guide to the Heart by Pam Houston (1999): A mix of personal essays and short travel pieces. The material about her dysfunctional early family life, her chaotic dating, and her thrill-seeking adventures in the wilderness is reminiscent of the highly autobiographical

A Rough Guide to the Heart by Pam Houston (1999): A mix of personal essays and short travel pieces. The material about her dysfunctional early family life, her chaotic dating, and her thrill-seeking adventures in the wilderness is reminiscent of the highly autobiographical  The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier – A pleasant year’s diary of rural living and adjusting to her husband’s new diagnosis of neurodivergence.

The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier – A pleasant year’s diary of rural living and adjusting to her husband’s new diagnosis of neurodivergence.

This debut novel dropped through my door as a total surprise: not only was it unsolicited, but I’d not heard about it. In this modern take on the traditional haunted house story, Ellen is a ghostwriter sent from London to Elver House, Northumberland, to work on the memoirs of its octogenarian owner, Catherine Carey. Ellen will stay in the remote manor house for a week and record 20 hours of audio interviews – enough to flesh out an autobiography. Miss Carey isn’t a forthcoming subject, but Ellen manages to learn that her father drowned in the nearby brook and that all Miss Carey did afterwards was meant to please her grieving mother and the strictures of the time. But as strange happenings in the house interfere with her task, Ellen begins to doubt she’ll come away with usable material. I was reminded of

This debut novel dropped through my door as a total surprise: not only was it unsolicited, but I’d not heard about it. In this modern take on the traditional haunted house story, Ellen is a ghostwriter sent from London to Elver House, Northumberland, to work on the memoirs of its octogenarian owner, Catherine Carey. Ellen will stay in the remote manor house for a week and record 20 hours of audio interviews – enough to flesh out an autobiography. Miss Carey isn’t a forthcoming subject, but Ellen manages to learn that her father drowned in the nearby brook and that all Miss Carey did afterwards was meant to please her grieving mother and the strictures of the time. But as strange happenings in the house interfere with her task, Ellen begins to doubt she’ll come away with usable material. I was reminded of  I’m sure I read all of Dahl’s major works when I was a child, though I had no specific memory of this one. After his parents’ death in a car accident, a boy lives in his family home in England with his Norwegian grandmother. She tells him stories from Norway and schools him in how to recognize and avoid witches. They wear wigs and special shoes to hide their baldness and square feet, and with their wide nostrils they sniff out children to turn them into hated creatures like slugs. When Grandmamma falls ill with pneumonia, she and the boy travel to a Bournemouth hotel for her recovery only to stumble upon a convention of witches under the guise of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. The Grand High Witch (Anjelica Huston, if you know the movie) has a new concoction that will transform children into mice at enough of a delay to occur the following morning at school. It’s up to the boy and his grandmother to save the day. I really enjoyed this caper, which I interpreted as being – like Tove Jansson’s

I’m sure I read all of Dahl’s major works when I was a child, though I had no specific memory of this one. After his parents’ death in a car accident, a boy lives in his family home in England with his Norwegian grandmother. She tells him stories from Norway and schools him in how to recognize and avoid witches. They wear wigs and special shoes to hide their baldness and square feet, and with their wide nostrils they sniff out children to turn them into hated creatures like slugs. When Grandmamma falls ill with pneumonia, she and the boy travel to a Bournemouth hotel for her recovery only to stumble upon a convention of witches under the guise of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. The Grand High Witch (Anjelica Huston, if you know the movie) has a new concoction that will transform children into mice at enough of a delay to occur the following morning at school. It’s up to the boy and his grandmother to save the day. I really enjoyed this caper, which I interpreted as being – like Tove Jansson’s  Somehow I’ve read this entire series even though none of the subsequent books lived up to

Somehow I’ve read this entire series even though none of the subsequent books lived up to  The third in the “Sworn Soldier” series, after

The third in the “Sworn Soldier” series, after  A very different sort of vampire novel. Twenty-three-year-old Lydia is half Japanese and half Malaysian; half human and half vampire. She’s trying to follow in her late father’s footsteps as an artist through an internship at a Battersea gallery, which comes with studio space where she’ll sleep to save money. But she can only drink blood like her mother, who turned her when she was a baby. Mostly she subsists on pig blood – which she can order dried if she can’t buy it fresh from a butcher – though, in one disturbing sequence, she brings home a duck carcass. When she falls for Ben, one of her studio-mates, she imagines what it would be like to be fully human: to make art together, to explore Asian cuisine, to bond over losing their mothers (his is dying of cancer; hers is in a care home with violence-tinged dementia). But Ben is already seeing someone, the internship is predictably dull, and a first attempt at consuming regular food goes badly wrong. There are a lot of promising threads in this debut. It’s fascinating how Lydia can intuit a creature’s whole life story by drinking their blood. She becomes obsessed with the Baba Yaga folk tale (and also mentions Malay vampire legends) and there’s a neat little bit of #MeToo revenge. But overall, it’s half-baked. Really, it’s just a disaster-woman book in disguise. The way Lydia’s identity determines her attitudes towards food and sex feels like a symbol of body dysmorphia. I’ll look out to see if Kohda does something more distinctive in future. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com)

A very different sort of vampire novel. Twenty-three-year-old Lydia is half Japanese and half Malaysian; half human and half vampire. She’s trying to follow in her late father’s footsteps as an artist through an internship at a Battersea gallery, which comes with studio space where she’ll sleep to save money. But she can only drink blood like her mother, who turned her when she was a baby. Mostly she subsists on pig blood – which she can order dried if she can’t buy it fresh from a butcher – though, in one disturbing sequence, she brings home a duck carcass. When she falls for Ben, one of her studio-mates, she imagines what it would be like to be fully human: to make art together, to explore Asian cuisine, to bond over losing their mothers (his is dying of cancer; hers is in a care home with violence-tinged dementia). But Ben is already seeing someone, the internship is predictably dull, and a first attempt at consuming regular food goes badly wrong. There are a lot of promising threads in this debut. It’s fascinating how Lydia can intuit a creature’s whole life story by drinking their blood. She becomes obsessed with the Baba Yaga folk tale (and also mentions Malay vampire legends) and there’s a neat little bit of #MeToo revenge. But overall, it’s half-baked. Really, it’s just a disaster-woman book in disguise. The way Lydia’s identity determines her attitudes towards food and sex feels like a symbol of body dysmorphia. I’ll look out to see if Kohda does something more distinctive in future. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com)

Rightly likened to Of Mice and Men, this is an engrossing short novel about two brothers, Neil and Calum, tasked with climbing trees and gathering the pinecones of a wealthy Scottish estate. They will be used to replant the many woodlands being cut down to fuel the war effort. Calum, the younger brother, is physically and intellectually disabled but has a deep well of compassion for living creatures. He has unwittingly made an enemy of the estate’s gamekeeper, Duror, by releasing wounded rabbits from his traps. Much of the story is taken up with Duror’s seemingly baseless feud against the brothers – though we’re meant to understand that his bedbound wife’s obesity and his subsequent sexual frustration may have something to do with it – as well as with Lady Runcie-Campbell’s class prejudice. Her son, Roderick, is an unexpected would-be hero and voice of pure empathy. I read this quickly, with grim fascination, knowing tragedy was coming but not quite how things would play out. The introduction to Canongate’s Canons Collection edition is by actor Paul Giamatti, of all people. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

Rightly likened to Of Mice and Men, this is an engrossing short novel about two brothers, Neil and Calum, tasked with climbing trees and gathering the pinecones of a wealthy Scottish estate. They will be used to replant the many woodlands being cut down to fuel the war effort. Calum, the younger brother, is physically and intellectually disabled but has a deep well of compassion for living creatures. He has unwittingly made an enemy of the estate’s gamekeeper, Duror, by releasing wounded rabbits from his traps. Much of the story is taken up with Duror’s seemingly baseless feud against the brothers – though we’re meant to understand that his bedbound wife’s obesity and his subsequent sexual frustration may have something to do with it – as well as with Lady Runcie-Campbell’s class prejudice. Her son, Roderick, is an unexpected would-be hero and voice of pure empathy. I read this quickly, with grim fascination, knowing tragedy was coming but not quite how things would play out. The introduction to Canongate’s Canons Collection edition is by actor Paul Giamatti, of all people. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

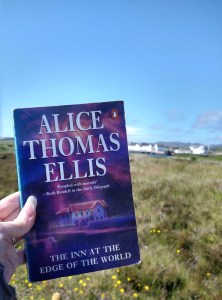

Eric and Mabel moved from the Midlands to run a hotel on a remote Scottish island. He places an advertisement in select London periodicals to lure in some Christmas-haters for the holidays and attracts a motley group: a bereaved former soldier writing a biography of General Gordon, a pair of actors known only for commercials, a psychoanalyst, and a department store buyer looking for a novel sweater pattern. Mabel decides she’s had enough and flees the island just as the guests start arriving. One guest is stalking another; one has history on the island. And all along, there are hints that this is a site of major selkie activity. I found it jarring how the novella moved from Shena Mackay-like social comedy into magic realism and doubt I’ll read more by Ellis (I’d already read one volume of

Eric and Mabel moved from the Midlands to run a hotel on a remote Scottish island. He places an advertisement in select London periodicals to lure in some Christmas-haters for the holidays and attracts a motley group: a bereaved former soldier writing a biography of General Gordon, a pair of actors known only for commercials, a psychoanalyst, and a department store buyer looking for a novel sweater pattern. Mabel decides she’s had enough and flees the island just as the guests start arriving. One guest is stalking another; one has history on the island. And all along, there are hints that this is a site of major selkie activity. I found it jarring how the novella moved from Shena Mackay-like social comedy into magic realism and doubt I’ll read more by Ellis (I’d already read one volume of

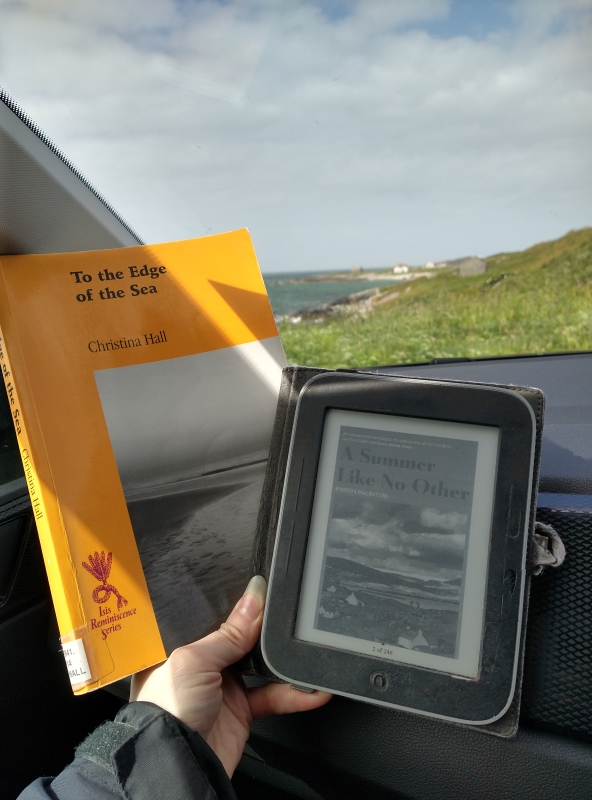

The many Gaelic phrases, defined in footnotes, help to create the atmosphere. The chapter epigraphs from the legend of Oisín (son of Fionn Mac Cumhaill) and Tír Na nÓg, the land of eternal youth, heighten the contrast between Colin’s idealism and the reality of this life-changing season. I think this is the first book I’ve read that was originally published in Gaelic and I hope it will find readers far beyond its island niche. (BookSirens)

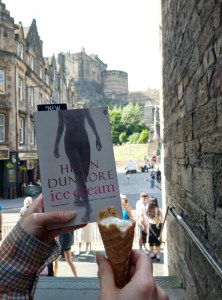

The many Gaelic phrases, defined in footnotes, help to create the atmosphere. The chapter epigraphs from the legend of Oisín (son of Fionn Mac Cumhaill) and Tír Na nÓg, the land of eternal youth, heighten the contrast between Colin’s idealism and the reality of this life-changing season. I think this is the first book I’ve read that was originally published in Gaelic and I hope it will find readers far beyond its island niche. (BookSirens)  1) Our transit through Edinburgh was brief and muggy, but we made sure to leave just enough time to queue for cones at Mary’s Milk Bar, which has the most interesting flavours you’ll find anywhere. Pictured, though half eaten, are my one scoop of Earl Grey and peach sorbet and one scoop of fig and cardamom ice cream. When we returned to Edinburgh to return the car at the end of our trip, I took the train home by myself but C stayed on for a conference, during which he treated himself to another round at Mary’s.

1) Our transit through Edinburgh was brief and muggy, but we made sure to leave just enough time to queue for cones at Mary’s Milk Bar, which has the most interesting flavours you’ll find anywhere. Pictured, though half eaten, are my one scoop of Earl Grey and peach sorbet and one scoop of fig and cardamom ice cream. When we returned to Edinburgh to return the car at the end of our trip, I took the train home by myself but C stayed on for a conference, during which he treated himself to another round at Mary’s.

A quaint short memoir set in the 1950s on the island of Mull (which we sailed past on our way to and from the Outer Hebrides). It’s narrated in tongue-in-cheek fashion by Nicholas the Cat, who pals around with the farm’s dogs, horse and goats and comments on the doings of its human inhabitants, such as “Puddy” (Carothers), a war widow, and her daughter Fionna, who goes away to school. “We understand so much about them, yet they understand so little about us,” he opines. Indeed, the animals are all observant and can communicate with each other. Corrieshellach is a fine horse taken to compete in shows. The goats are lucky to escape with their lives after a local outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease among livestock. Nicholas grows fat on rabbits and fathers several litters. He voices some traditional views (the Clearances: bad but the Empire: good; crows: bad); then again, cats would certainly be C/conservatives. A sweet Blyton-esque read for precocious children or sentimental adults, this passed the time nicely on a long drive. It could do with a better title, though; the ducks only play a tiny role. (Favourite aside: “that beverage which humans find so comforting when things aren’t right. Tea.”) (Secondhand – Benbecula thrift shop)

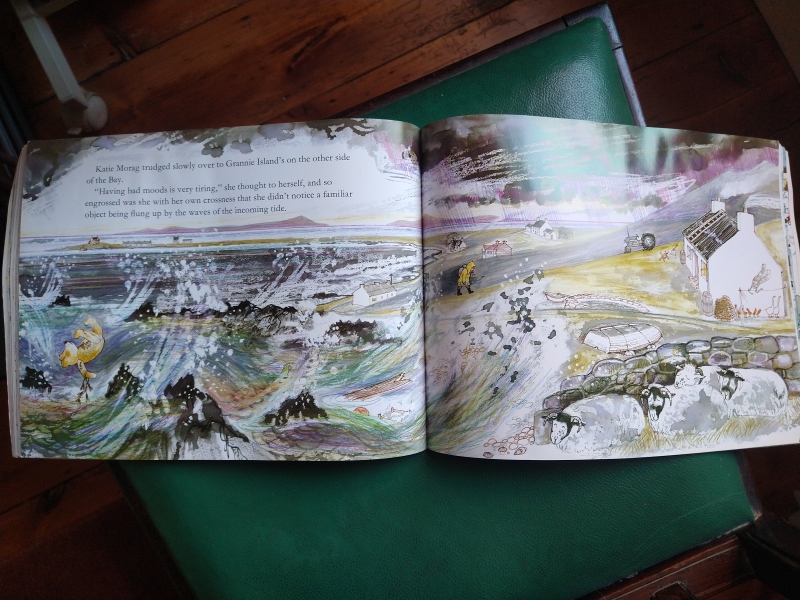

A quaint short memoir set in the 1950s on the island of Mull (which we sailed past on our way to and from the Outer Hebrides). It’s narrated in tongue-in-cheek fashion by Nicholas the Cat, who pals around with the farm’s dogs, horse and goats and comments on the doings of its human inhabitants, such as “Puddy” (Carothers), a war widow, and her daughter Fionna, who goes away to school. “We understand so much about them, yet they understand so little about us,” he opines. Indeed, the animals are all observant and can communicate with each other. Corrieshellach is a fine horse taken to compete in shows. The goats are lucky to escape with their lives after a local outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease among livestock. Nicholas grows fat on rabbits and fathers several litters. He voices some traditional views (the Clearances: bad but the Empire: good; crows: bad); then again, cats would certainly be C/conservatives. A sweet Blyton-esque read for precocious children or sentimental adults, this passed the time nicely on a long drive. It could do with a better title, though; the ducks only play a tiny role. (Favourite aside: “that beverage which humans find so comforting when things aren’t right. Tea.”) (Secondhand – Benbecula thrift shop)  I read half of this large-format paperback before our trip and the rest afterward. It collects four of Hedderwick’s picture books, which are all set on the Isle of Struay, a kind of Hebridean composite that reproduces the islands’ wildlife and scenery beautifully. Katie Morag’s parents run the shop and post office and her mother always seems to be producing another little brother. In Katie Morag Delivers the Mail, the little red-haired girl causes chaos by delivering parcels at random. Sophisticated Granma Mainland and practical Grannie Island are the stars of Katie Morag and the Two Grandmothers. Katie Morag learns to deal with her anger and with being punished, respectively, in …and the Tiresome Ted and …and the Big Boy Cousins. Cute stories with useful lessons, but the illustrations are the main attraction. I’ll get the rest of the books out from the library. (Little Free Library)

I read half of this large-format paperback before our trip and the rest afterward. It collects four of Hedderwick’s picture books, which are all set on the Isle of Struay, a kind of Hebridean composite that reproduces the islands’ wildlife and scenery beautifully. Katie Morag’s parents run the shop and post office and her mother always seems to be producing another little brother. In Katie Morag Delivers the Mail, the little red-haired girl causes chaos by delivering parcels at random. Sophisticated Granma Mainland and practical Grannie Island are the stars of Katie Morag and the Two Grandmothers. Katie Morag learns to deal with her anger and with being punished, respectively, in …and the Tiresome Ted and …and the Big Boy Cousins. Cute stories with useful lessons, but the illustrations are the main attraction. I’ll get the rest of the books out from the library. (Little Free Library)