Reading from the Wainwright Prize Longlists

The Wainwright Prize is one that I’ve ended up following closely almost by accident, simply because I tend to read most of the nature books released in the UK in any given year. A few months back I cheekily wrote to the prize director, proffering myself as a judge and appending a list of eligible titles I hoped were in consideration. Although they already had a full judging roster for 2021, I got a very kind reply thanking me for my recommendations and promising to bear me in mind for the future. Fifteen of my 25 suggestions made it onto the lists below.

This is the second year that there have been two awards, one for writing on UK nature and the other on global conservation themes. Tomorrow (August 4th) at 4 p.m., the longlists will be narrowed down to shortlists. I happened to have read and reviewed 12 of the nominees already, and I have a few others in progress.

UK nature writing longlist:

The Circling Sky by Neil Ansell: Hoping to reclaim an ancestral connection, Ansell visited the New Forest some 30 times between January 2019 and January 2020, observing the unfolding seasons and the many uncommon and endemic species its miles house. He weaves together his personal story, the shocking history of forced Gypsy relocation into forest compounds starting in the 1920s, and the unfairness of land ownership in Britain. The New Forest is a model of both wildlife-friendly land management and freedom of human access. (On my Best of 2021 so far list.)

The Circling Sky by Neil Ansell: Hoping to reclaim an ancestral connection, Ansell visited the New Forest some 30 times between January 2019 and January 2020, observing the unfolding seasons and the many uncommon and endemic species its miles house. He weaves together his personal story, the shocking history of forced Gypsy relocation into forest compounds starting in the 1920s, and the unfairness of land ownership in Britain. The New Forest is a model of both wildlife-friendly land management and freedom of human access. (On my Best of 2021 so far list.)

T he Screaming Sky by Charles Foster: A Renaissance man as well versed in law and theology as he is in natural history, Foster is obsessed with swifts and ashamed of his own species: for looking down at their feet when they could be watching the skies; for the “pathological tidiness” that leaves birds and other creatures no place to live. He delivers heaps of information on the birds but refuses to stick to a just-the-facts approach. The book quotes frequently from poetry and the prose is full of sharp turns of phrase and whimsy. (Also on my Best of 2021 so far list.)

he Screaming Sky by Charles Foster: A Renaissance man as well versed in law and theology as he is in natural history, Foster is obsessed with swifts and ashamed of his own species: for looking down at their feet when they could be watching the skies; for the “pathological tidiness” that leaves birds and other creatures no place to live. He delivers heaps of information on the birds but refuses to stick to a just-the-facts approach. The book quotes frequently from poetry and the prose is full of sharp turns of phrase and whimsy. (Also on my Best of 2021 so far list.)

Featherhood by Charlie Gilmour: As an aimless twentysomething, Gilmour tried to rekindle a relationship with his unreliable poet father at the same time that he and his wife were pondering starting a family of their own. Meanwhile, he was raising Benzene, a magpie that fell out of the nest and ended up in his care. The experience taught him responsibility and compassionate care for another creature. Gilmour makes elegant use of connections and metaphors. He’s so good at scenes, dialogue and emotion – a natural writer.

Featherhood by Charlie Gilmour: As an aimless twentysomething, Gilmour tried to rekindle a relationship with his unreliable poet father at the same time that he and his wife were pondering starting a family of their own. Meanwhile, he was raising Benzene, a magpie that fell out of the nest and ended up in his care. The experience taught him responsibility and compassionate care for another creature. Gilmour makes elegant use of connections and metaphors. He’s so good at scenes, dialogue and emotion – a natural writer.

Seed to Dust by Marc Hamer: Hamer paints a loving picture of his final year at the 12-acre British garden he tended for decades. In few-page essays, the book journeys through a gardener’s year. This is creative nonfiction rather than straightforward memoir. The prose is adorned with lovely metaphors. In places, the language edges towards purple and the content becomes repetitive – a danger of the diary format. However, the focus on emotions and self-perception – rare for a male nature writer – is refreshing. (Reviewed for Foreword.)

Seed to Dust by Marc Hamer: Hamer paints a loving picture of his final year at the 12-acre British garden he tended for decades. In few-page essays, the book journeys through a gardener’s year. This is creative nonfiction rather than straightforward memoir. The prose is adorned with lovely metaphors. In places, the language edges towards purple and the content becomes repetitive – a danger of the diary format. However, the focus on emotions and self-perception – rare for a male nature writer – is refreshing. (Reviewed for Foreword.)

The Stubborn Light of Things by Melissa Harrison: A collection of five and a half years’ worth of Harrison’s monthly Nature Notebook columns for The Times. Initially based in South London, Harrison moved to the Suffolk countryside in late 2017. In the grand tradition of Gilbert White, she records when she sees her firsts of a year. I appreciate how hands-on and practical Harrison is. She never misses an opportunity to tell readers about ways they can create habitat for wildlife and get involved in citizen science projects. (Reviewed for Shiny New Books.)

The Stubborn Light of Things by Melissa Harrison: A collection of five and a half years’ worth of Harrison’s monthly Nature Notebook columns for The Times. Initially based in South London, Harrison moved to the Suffolk countryside in late 2017. In the grand tradition of Gilbert White, she records when she sees her firsts of a year. I appreciate how hands-on and practical Harrison is. She never misses an opportunity to tell readers about ways they can create habitat for wildlife and get involved in citizen science projects. (Reviewed for Shiny New Books.)

Birdsong in a Time of Silence by Steven Lovatt: During the UK’s first lockdown, with planes grounded and cars stationary, many remarked on the quiet. All the better to hear birds going about their usual spring activities. For Lovatt, it was the excuse he needed to return to his childhood birdwatching hobby. In between accounts of his spring walks, he tells lively stories of common birds’ anatomy, diet, lifecycle, migration routes, and vocalizations. Lovatt’s writing is introspective and poetic, delighting in metaphors for sounds.

Birdsong in a Time of Silence by Steven Lovatt: During the UK’s first lockdown, with planes grounded and cars stationary, many remarked on the quiet. All the better to hear birds going about their usual spring activities. For Lovatt, it was the excuse he needed to return to his childhood birdwatching hobby. In between accounts of his spring walks, he tells lively stories of common birds’ anatomy, diet, lifecycle, migration routes, and vocalizations. Lovatt’s writing is introspective and poetic, delighting in metaphors for sounds.

Vesper Flights by Helen Macdonald: Though written for various periodicals and ranging in topic from mushroom-hunting to deer–vehicle collisions and in scope from deeply researched travel pieces to one-page reminiscences, these essays form a coherent whole. Equally reliant on argument and epiphany, the book has more to say about human–animal interactions in one of its essays than some whole volumes manage. Her final lines are always breath-taking. I’d rather read her writing on any subject than almost any other author’s. (My top nonfiction release of 2020.)

Vesper Flights by Helen Macdonald: Though written for various periodicals and ranging in topic from mushroom-hunting to deer–vehicle collisions and in scope from deeply researched travel pieces to one-page reminiscences, these essays form a coherent whole. Equally reliant on argument and epiphany, the book has more to say about human–animal interactions in one of its essays than some whole volumes manage. Her final lines are always breath-taking. I’d rather read her writing on any subject than almost any other author’s. (My top nonfiction release of 2020.)

Skylarks with Rosie by Stephen Moss: Devoting a chapter each to the first 13 weeks of the initial UK lockdown, Moss traces the season’s development in Somerset alongside his family’s experiences and what was emerging on the national news. He welcomed migrating birds and marked his first sightings of butterflies and other insects. Nature came to him, too. For once, he felt that he had truly appreciated the spring, noting its every milestone and “rediscovering the joys of wildlife-watching close to home.”

Skylarks with Rosie by Stephen Moss: Devoting a chapter each to the first 13 weeks of the initial UK lockdown, Moss traces the season’s development in Somerset alongside his family’s experiences and what was emerging on the national news. He welcomed migrating birds and marked his first sightings of butterflies and other insects. Nature came to him, too. For once, he felt that he had truly appreciated the spring, noting its every milestone and “rediscovering the joys of wildlife-watching close to home.”

Thin Places by Kerri ní Dochartaigh: I received a proof copy from Canongate and twice tried the first few pages, but couldn’t wade through the excessive lyricism (and downright incorrect information – weaving a mystical description of a Winter Moth’s flight, she keeps referring to the creature as “she,” whereas when I showed the passage to my entomologist husband he told me that the females of that species are flightless). I’m told it develops into an eloquent memoir of growing up during the Troubles. Perhaps reminiscent of The Outrun?

Thin Places by Kerri ní Dochartaigh: I received a proof copy from Canongate and twice tried the first few pages, but couldn’t wade through the excessive lyricism (and downright incorrect information – weaving a mystical description of a Winter Moth’s flight, she keeps referring to the creature as “she,” whereas when I showed the passage to my entomologist husband he told me that the females of that species are flightless). I’m told it develops into an eloquent memoir of growing up during the Troubles. Perhaps reminiscent of The Outrun?

Into the Tangled Bank by Lev Parikian: A delightfully Bryson-esque tour that moves ever outwards, starting with the author’s own home and garden and proceeding to take in his South London patch and his journeys around the British Isles before closing with the wonders of the night sky. By slowing down to appreciate what is all around us, he proposes, we might enthuse others to engage with nature. With the zeal of a recent convert, he guides readers through momentous sightings and everyday moments of connection. (When I reviewed this in July 2020, I correctly predicted it would make the longlist!)

Into the Tangled Bank by Lev Parikian: A delightfully Bryson-esque tour that moves ever outwards, starting with the author’s own home and garden and proceeding to take in his South London patch and his journeys around the British Isles before closing with the wonders of the night sky. By slowing down to appreciate what is all around us, he proposes, we might enthuse others to engage with nature. With the zeal of a recent convert, he guides readers through momentous sightings and everyday moments of connection. (When I reviewed this in July 2020, I correctly predicted it would make the longlist!)

English Pastoral by James Rebanks: This struck me for its bravery, good sense and humility. The topics of the degradation of land and the dangers of intensive farming are of the utmost importance. Daring to undermine his earlier work and his online persona, the author questions the mythos of modern farming, contrasting its practices with the more sustainable and wildlife-friendly ones his grandfather espoused. Old-fashioned can still be best if it means preserving soil health, river quality and the curlew population.

English Pastoral by James Rebanks: This struck me for its bravery, good sense and humility. The topics of the degradation of land and the dangers of intensive farming are of the utmost importance. Daring to undermine his earlier work and his online persona, the author questions the mythos of modern farming, contrasting its practices with the more sustainable and wildlife-friendly ones his grandfather espoused. Old-fashioned can still be best if it means preserving soil health, river quality and the curlew population.

I Belong Here by Anita Sethi: I recently skimmed this from the library. Two things are certain: 1) BIPOC writers should appear more frequently on prize lists, so it’s wonderful that Sethi is here; 2) this book was poorly put together. It’s part memoir of an incident of racial abuse, part political manifesto, and part quite nice travelogue. The parts don’t make a whole. The contents are repetitive and generic (definitions, overstretched metaphors). Sethi had a couple of strong articles here, not a whole book. I blame her editors for not eliciting better.

I Belong Here by Anita Sethi: I recently skimmed this from the library. Two things are certain: 1) BIPOC writers should appear more frequently on prize lists, so it’s wonderful that Sethi is here; 2) this book was poorly put together. It’s part memoir of an incident of racial abuse, part political manifesto, and part quite nice travelogue. The parts don’t make a whole. The contents are repetitive and generic (definitions, overstretched metaphors). Sethi had a couple of strong articles here, not a whole book. I blame her editors for not eliciting better.

The Wild Silence by Raynor Winn: I only skimmed this, too. I got the feeling her publisher was desperate to capitalize on the popularity of her first book and said “give us whatever you have,” cramming drafts of several different projects (a memoir that went deeper into the past, a ‘what happened next’ sequel to The Salt Path, and an Iceland travelogue) into one book and rushing it through to publication. Winn’s writing is still strong, though; she captures dialogue and scenes naturally, and you believe in how much the connection to the land matters to her.

The Wild Silence by Raynor Winn: I only skimmed this, too. I got the feeling her publisher was desperate to capitalize on the popularity of her first book and said “give us whatever you have,” cramming drafts of several different projects (a memoir that went deeper into the past, a ‘what happened next’ sequel to The Salt Path, and an Iceland travelogue) into one book and rushing it through to publication. Winn’s writing is still strong, though; she captures dialogue and scenes naturally, and you believe in how much the connection to the land matters to her.

Global conservation longlist:

Like last year, I’ve read much less from this longlist since I gravitate more towards nature writing and memoirs than to hard or popular science. So I have read, am reading or plan to read about half of this list, as opposed to pretty much all of the other one.

Islands of Abandonment by Cal Flyn: This was on my Most Anticipated list for 2021 and I treated myself to a copy while we were up in Northumberland. I’m nearly a third of the way through this fascinating, well-written tour of places where nature has spontaneously regenerated due to human neglect: depleted mining areas in Scotland, former conflict zones, Soviet collective farms turned feral, sites of nuclear disaster, and so on. I’m about to start the chapter on Chernobyl, which I expect to echo Mark O’Connell’s Notes from an Apocalypse.

Islands of Abandonment by Cal Flyn: This was on my Most Anticipated list for 2021 and I treated myself to a copy while we were up in Northumberland. I’m nearly a third of the way through this fascinating, well-written tour of places where nature has spontaneously regenerated due to human neglect: depleted mining areas in Scotland, former conflict zones, Soviet collective farms turned feral, sites of nuclear disaster, and so on. I’m about to start the chapter on Chernobyl, which I expect to echo Mark O’Connell’s Notes from an Apocalypse.

What If We Stopped Pretending? by Jonathan Franzen: The message of this controversial 2019 New Yorker essay is simple: climate breakdown is here, so stop denying it and talking of “saving the planet”; it’s too late. Global warming is locked in; the will is not there to curb growth, overhaul economies, and ask people to relinquish developed world lifestyles. Instead, start preparing for the fallout (refugees) and saving what can be saved (particular habitats and species). Franzen is realistic about human nature and practical about what to do next.

What If We Stopped Pretending? by Jonathan Franzen: The message of this controversial 2019 New Yorker essay is simple: climate breakdown is here, so stop denying it and talking of “saving the planet”; it’s too late. Global warming is locked in; the will is not there to curb growth, overhaul economies, and ask people to relinquish developed world lifestyles. Instead, start preparing for the fallout (refugees) and saving what can be saved (particular habitats and species). Franzen is realistic about human nature and practical about what to do next.

Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake: Sheldrake’s enthusiasm is infectious as he researches fungal life in the tropical forests of Panama, accompanies truffle hunters in Italy, and takes part in a clinical study on the effects of LSD (derived from a fungus). More than a travel memoir, though, this is a work of proper science – over 100 pages are taken up by notes, bibliography and index. This is a perspective-altering text that reveals our unconscious species bias. I’ve recommended it widely, even to those who tend not to read nonfiction.

Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake: Sheldrake’s enthusiasm is infectious as he researches fungal life in the tropical forests of Panama, accompanies truffle hunters in Italy, and takes part in a clinical study on the effects of LSD (derived from a fungus). More than a travel memoir, though, this is a work of proper science – over 100 pages are taken up by notes, bibliography and index. This is a perspective-altering text that reveals our unconscious species bias. I’ve recommended it widely, even to those who tend not to read nonfiction.

Ice Rivers by Jemma Wadham: I have this out from the library and am two-thirds through. Wadham, a leading glaciologist, introduces readers to the science of glaciers: where they are, what lives on and under them, how they move and change, and the grave threats they face (and, therefore, so do we). The science, even dumbed down, is a little hard to follow, but I love experiencing extreme landscapes like Greenland and Antarctica with her. She neatly inserts tiny mentions of her personal life, such as her mother’s death, a miscarriage and a benign brain cyst.

Ice Rivers by Jemma Wadham: I have this out from the library and am two-thirds through. Wadham, a leading glaciologist, introduces readers to the science of glaciers: where they are, what lives on and under them, how they move and change, and the grave threats they face (and, therefore, so do we). The science, even dumbed down, is a little hard to follow, but I love experiencing extreme landscapes like Greenland and Antarctica with her. She neatly inserts tiny mentions of her personal life, such as her mother’s death, a miscarriage and a benign brain cyst.

The rest of the longlist is:

- A Life on Our Planet by David Attenborough – I’ve never read a book by Attenborough (and tend to worry this sort of book would be ghostwritten), but wouldn’t be averse to doing so.

Fathoms by Rebecca Giggs – All about whales. Kate raved about it. I have this on hold at the library.

Fathoms by Rebecca Giggs – All about whales. Kate raved about it. I have this on hold at the library.- Net Zero: How We Stop Causing Climate Change by Dieter Helm

- Under a White Sky by Elizabeth Kolbert – I have read her before and would again.

- Riders on the Storm by Alistair McIntosh – My husband has read several of his books and rates them highly.

- The New Climate War by Michael E. Mann

- The Reindeer Chronicles by Judith D. Schwartz – I’ve been keen to read this one.

- A World on the Wing by Scott Weidensaul – My husband is reading this from the library.

My predictions/wishes for the shortlists:

It’s high time that a woman won again. And why not for both, eh? (Amy Liptrot is still the only female winner in the Prize’s seven-year history, for The Outrun in 2016.)

UK nature writing:

- The Circling Sky by Neil Ansell

- The Screaming Sky by Charles Foster

- Featherhood by Charlie Gilmour

- Vesper Flights by Helen Macdonald*

- English Pastoral by James Rebanks

- I Belong Here by Anita Sethi

- The Wild Silence by Raynor Winn

Writing on global conservation:

- Islands of Abandonment by Cal Flyn*

- Fathoms by Rebecca Giggs

- Under a White Sky by Elizabeth Kolbert

- Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake

- Ice Rivers by Jemma Wadham

- A World on the Wing by Scott Weidensaul

*Overall winners, if I had my way.

Have you read anything from the Wainwright Prize longlists?

Do any of these books interest you?

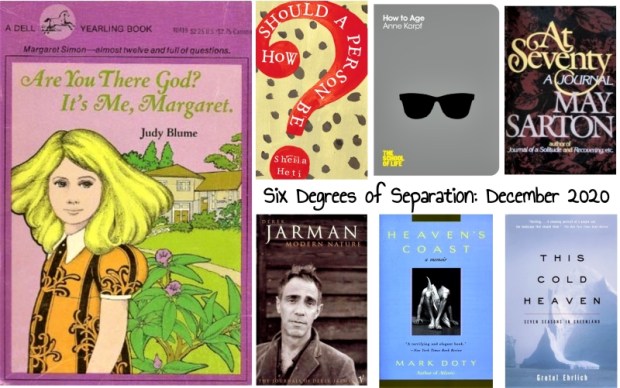

Six Degrees of Separation: From Margaret to This Cold Heaven

This month we’re starting with Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret (which I have punctuated appropriately!). See Kate’s opening post. I know I read this as a child, but other Judy Blume novels were more meaningful for me since I was a tomboy and late bloomer. The only line that stays with me is the chant “We must, we must, we must increase our bust!”

#1 Another book with a question in the title (and dominating the cover) is How Should a Person Be? by Sheila Heti. I found a hardback copy in the unofficial Little Free Library I ran in our neighborhood during the first lockdown before the public library reopened. Heti is a divisive author, but I loved Motherhood for perfectly encapsulating my situation. I think this one, too, is autofiction, and the title question is one I ask myself variations on frequently.

#1 Another book with a question in the title (and dominating the cover) is How Should a Person Be? by Sheila Heti. I found a hardback copy in the unofficial Little Free Library I ran in our neighborhood during the first lockdown before the public library reopened. Heti is a divisive author, but I loved Motherhood for perfectly encapsulating my situation. I think this one, too, is autofiction, and the title question is one I ask myself variations on frequently.

#2 I’ve read quite a few “How to” books, whether straightforward explanatory/self-help texts or not. Lots happened to be from the School of Life series. One I found particularly enjoyable and helpful was How to Age by Anne Karpf. She writes frankly about bodily degeneration, the pursuit of wisdom, and preparation for death. “Growth and psychological development aren’t a property of our earliest years but can continue throughout the life cycle.”

#2 I’ve read quite a few “How to” books, whether straightforward explanatory/self-help texts or not. Lots happened to be from the School of Life series. One I found particularly enjoyable and helpful was How to Age by Anne Karpf. She writes frankly about bodily degeneration, the pursuit of wisdom, and preparation for death. “Growth and psychological development aren’t a property of our earliest years but can continue throughout the life cycle.”

#3 Ageing is a major element in May Sarton’s journals, particularly as she moves from her seventies into her eighties and fights illnesses. I’ve read all but one of her autobiographical works now, and – while my favorite is Journal of a Solitude – the one I’ve chosen as most representative of her usual themes, including inspiration, camaraderie, the pressures of the writing life, and old age, is At Seventy.

#3 Ageing is a major element in May Sarton’s journals, particularly as she moves from her seventies into her eighties and fights illnesses. I’ve read all but one of her autobiographical works now, and – while my favorite is Journal of a Solitude – the one I’ve chosen as most representative of her usual themes, including inspiration, camaraderie, the pressures of the writing life, and old age, is At Seventy.

#4 Sarton was a keen gardener, as was Derek Jarman. I learned about him in the context of nature helping people come to terms with their mortality. Modern Nature reproduces the journal the gay, HIV-positive filmmaker kept in 1989–90. Prospect Cottage in Dungeness, Kent, and the unusual garden he cultivated there, was his refuge between trips to London and further afield, and a mental sanctuary when he was marooned in the hospital.

#4 Sarton was a keen gardener, as was Derek Jarman. I learned about him in the context of nature helping people come to terms with their mortality. Modern Nature reproduces the journal the gay, HIV-positive filmmaker kept in 1989–90. Prospect Cottage in Dungeness, Kent, and the unusual garden he cultivated there, was his refuge between trips to London and further afield, and a mental sanctuary when he was marooned in the hospital.

#5 One of the first memoirs I ever read and loved was Heaven’s Coast by Mark Doty, about his partner Wally’s death from AIDS. This sparked my continuing interest in illness and bereavement narratives, and it was through following up Doty’s memoirs with his collections of poems that I first got into contemporary poetry, so he’s had a major influence on my taste. I’ve had Heaven’s Coast on my rereading shelf for ages, so really must get to it in 2021.

#5 One of the first memoirs I ever read and loved was Heaven’s Coast by Mark Doty, about his partner Wally’s death from AIDS. This sparked my continuing interest in illness and bereavement narratives, and it was through following up Doty’s memoirs with his collections of poems that I first got into contemporary poetry, so he’s had a major influence on my taste. I’ve had Heaven’s Coast on my rereading shelf for ages, so really must get to it in 2021.

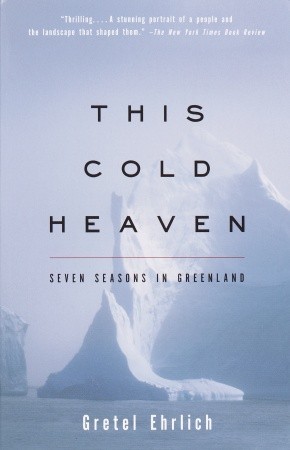

#6 Thinking of heaven, a nice loop back to Blume’s Margaret and her determination to find God … one of the finest travel books I’ve read is This Cold Heaven, about Gretel Ehrlich’s expeditions to Greenland and historical precursors who explored it. Even more than her intrepid wanderings, I was impressed by her prose, which made the icy scenery new every time. “Part jewel, part eye, part lighthouse, part recumbent monolith, the ice is a bright spot on the upper tier of the globe where the world’s purse strings have been pulled tight.”

#6 Thinking of heaven, a nice loop back to Blume’s Margaret and her determination to find God … one of the finest travel books I’ve read is This Cold Heaven, about Gretel Ehrlich’s expeditions to Greenland and historical precursors who explored it. Even more than her intrepid wanderings, I was impressed by her prose, which made the icy scenery new every time. “Part jewel, part eye, part lighthouse, part recumbent monolith, the ice is a bright spot on the upper tier of the globe where the world’s purse strings have been pulled tight.”

A fitting final selection for this week’s properly chilly winter temperatures, too. I’ll be writing up my first snowy and/or holiday-themed reads of the year in a couple of weeks.

Join us for #6Degrees of Separation if you haven’t already! (Hosted on the first Saturday of each month by Kate W. of Books Are My Favourite and Best.)

Have you read any of my selections? Are you tempted by any you didn’t know before?

Snow-y Reads

It’s been a frigid start to March here in Europe. Even though it only amounted to a few inches in total, this is still the most snow we’ve seen in years. We were without heating for 46 hours during the coldest couple of days due to an inaccessible frozen pipe, so I’m grateful that things have now thawed and spring is looking more likely. During winter’s last gasp, though, I’ve been dipping into a few appropriately snow-themed books. I had more success with some than with others. I’ll start with the one that stood out.

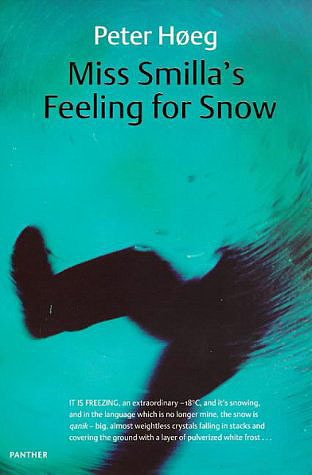

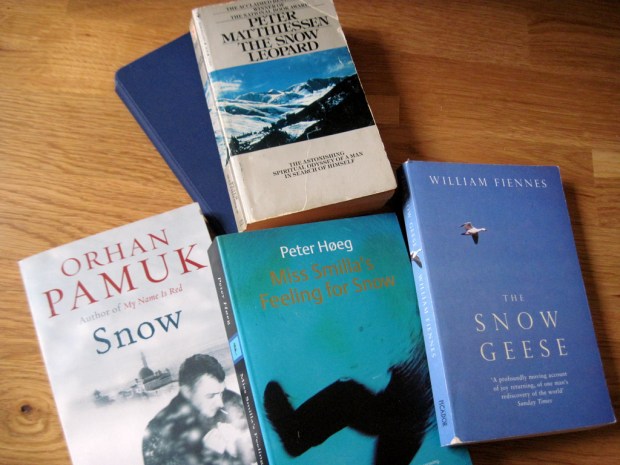

Miss Smilla’s Feeling for Snow by Peter Høeg (1992)

[trans. from the Danish by Felicity David]

Nordic noir avant la lettre? I bought this rather by accident; had I realized it was a murder mystery, I never would have taken a chance on this international bestseller. That would have been too bad, as it’s much more interesting than your average crime thriller. The narrator/detective is Smilla Jaspersen: a 37-year-old mathematician and former Arctic navigator with a Danish father and Greenlander mother, she’s a stylish dresser and a shrewd, bold questioner who makes herself unpopular by nosing about where she doesn’t belong.

Nordic noir avant la lettre? I bought this rather by accident; had I realized it was a murder mystery, I never would have taken a chance on this international bestseller. That would have been too bad, as it’s much more interesting than your average crime thriller. The narrator/detective is Smilla Jaspersen: a 37-year-old mathematician and former Arctic navigator with a Danish father and Greenlander mother, she’s a stylish dresser and a shrewd, bold questioner who makes herself unpopular by nosing about where she doesn’t belong.

Isaiah, a little Greenlander boy, has fallen to his death from the roof of the Copenhagen apartment complex where Smilla also lives, and she’s convinced foul play was involved. In Part I she enlists the help of a mechanic neighbor (and love interest), a translator, an Arctic medicine specialist, and a mining corporation secretary to investigate Isaiah’s father’s death on a 1991 Arctic expedition and how it might be connected to Isaiah’s murder. In Part II she tests her theories by setting sail on the Greenland-bound Kronos as a stewardess. At every turn her snooping puts her in danger – there are some pretty violent scenes.

I read this fairly slowly, over the course of a month (alongside lots of other books); it’s absorbing but in a literary style, so not as pacey or full of cliffhangers as you’d expect from a suspense novel. I got myself confused over all the minor characters and the revelations about the expeditions, so made pencil notes inside the front cover to keep things straight. Setting aside the plot, which gets a bit silly towards the end, I valued this most for Smilla’s self-knowledge and insights into what it’s like to be a Greenlander in Denmark. I read this straight after Gretel Ehrlich’s travel book about Greenland, This Cold Heaven – an excellent pairing I’d recommend to anyone who wants to spend time vicariously traveling in the far north.

Favorite wintry passage:

“I’m not perfect. I think more highly of snow and ice than of love. It’s easier for me to be interested in mathematics than to have affection for my fellow human beings.”

My rating:

One that I left unfinished:

Snow by Orhan Pamuk (2002)

[trans. from the Turkish by Maureen Freely]

This novel seems to be based around an elaborate play on words: it’s set in Kars, a Turkish town where the protagonist, a poet known by the initials Ka, becomes stranded by the snow (Kar in Turkish). After 12 years in political exile in Germany, Ka is back in Turkey for his mother’s funeral. While he’s here, he decides to investigate a recent spate of female suicides, keep tabs on the upcoming election, and see if he can win the love of divorcée Ipek, daughter of the owner of the Snow Palace Hotel, where he’s staying. There’s a hint of magic realism to the novel: the newspaper covers Ka’s reading of a poem called “Snow” before he’s even written it. He and Ipek witness the shooting of the director of the Institute of Education. The attempted assassination is revenge for him banning girls who wear headscarves from schools.

This novel seems to be based around an elaborate play on words: it’s set in Kars, a Turkish town where the protagonist, a poet known by the initials Ka, becomes stranded by the snow (Kar in Turkish). After 12 years in political exile in Germany, Ka is back in Turkey for his mother’s funeral. While he’s here, he decides to investigate a recent spate of female suicides, keep tabs on the upcoming election, and see if he can win the love of divorcée Ipek, daughter of the owner of the Snow Palace Hotel, where he’s staying. There’s a hint of magic realism to the novel: the newspaper covers Ka’s reading of a poem called “Snow” before he’s even written it. He and Ipek witness the shooting of the director of the Institute of Education. The attempted assassination is revenge for him banning girls who wear headscarves from schools.

As in Elif Shafak’s Three Daughters of Eve, the emphasis is on Turkey’s split personality: a choice between fundamentalism (= East, poverty) and secularism (= West, wealth). Pamuk is pretty heavy-handed with these rival ideologies and with the symbolism of the snow. By the time I reached page 165, having skimmed maybe two chapters’ worth along the way, I couldn’t bear to keep going. However, if I get a recommendation of a shorter and subtler Pamuk novel I would give him another try. I did enjoy the various nice quotes about snow (reminiscent of Joyce’s “The Dead”) – it really was atmospheric for this time of year.

Favorite wintry passage:

“That’s why snow drew people together. It was as if snow cast a veil over hatreds, greed and wrath and made everyone feel close to one another.”

My rating:

One that I only skimmed:

The Snow Geese by William Fiennes (2002)

Having recovered from an illness that hit at age 25 while he was studying for a doctorate, Fiennes set off to track the migration route of the snow goose, which starts in the Gulf of Mexico and goes to the Arctic territories of Canada. He was inspired by his father’s love of birdwatching and Paul Gallico’s The Snow Goose (which I haven’t read). I thought this couldn’t fail to be great, what with its themes of travel, birds, illness and identity. However, Fiennes gets bogged down in details. When he stays with friendly Americans in Texas he gives you every detail of their home décor, meals and way of speaking; when he takes a Greyhound bus ride he recounts every conversation he had with his random seatmates. This is too much about the grind of travel and not enough about the natural spectacles he was searching for. And then when he gets up to the far north he eats snow goose. So I ended up just skimming this one for the birdwatching bits. I did like Fiennes’s writing, just not what he chose to focus on, so I’ll read his other memoir, The Music Room.

Having recovered from an illness that hit at age 25 while he was studying for a doctorate, Fiennes set off to track the migration route of the snow goose, which starts in the Gulf of Mexico and goes to the Arctic territories of Canada. He was inspired by his father’s love of birdwatching and Paul Gallico’s The Snow Goose (which I haven’t read). I thought this couldn’t fail to be great, what with its themes of travel, birds, illness and identity. However, Fiennes gets bogged down in details. When he stays with friendly Americans in Texas he gives you every detail of their home décor, meals and way of speaking; when he takes a Greyhound bus ride he recounts every conversation he had with his random seatmates. This is too much about the grind of travel and not enough about the natural spectacles he was searching for. And then when he gets up to the far north he eats snow goose. So I ended up just skimming this one for the birdwatching bits. I did like Fiennes’s writing, just not what he chose to focus on, so I’ll read his other memoir, The Music Room.

My rating:

Considered but quickly abandoned: In the Midst of Winter by Isabel Allende

Considered but quickly abandoned: In the Midst of Winter by Isabel Allende

Would like to read soon: The Snow Leopard by Peter Matthiessen – my husband recently rated this 5 stars and calls it a spiritual quest memoir, with elements of nature and travel writing.

What’s been your snowbound reading this year?

Reviews Roundup, March–April

One of my goals with this blog was to have one convenient place where I could gather together all my writing that appears in disparate online locations. To that end, once a month I provide links to all book reviews I’ve published elsewhere, with a rating (below each description) and a taster so you can decide whether to read more. A few exceptions: I don’t point out my Kirkus Indie, BlueInk or Publishers Weekly reviews since I don’t get a byline.

The Bookbag

The Improbability of Love by Hannah Rothschild: From the Baileys Prize longlist, an enchanting debut novel that blends art and cooking, mystery and romance. Annie McDee, a heartbroken PA and amateur chef, pays £75 for a painting from a junk shop, not realizing it’s a lost Watteau that will spark bidding wars and uncover a sordid chapter of history. In a triumph of playful narration, we mostly learn about the artwork’s history from the painting ‘herself’. She recounts her turbulent 300-year-history and lists her many illustrious owners, including Marie Antoinette, Napoleon and Queen Victoria. These are the novel’s only first-person sections; you can just imagine a voiceover from Helen Mirren or Judi Dench.

The Improbability of Love by Hannah Rothschild: From the Baileys Prize longlist, an enchanting debut novel that blends art and cooking, mystery and romance. Annie McDee, a heartbroken PA and amateur chef, pays £75 for a painting from a junk shop, not realizing it’s a lost Watteau that will spark bidding wars and uncover a sordid chapter of history. In a triumph of playful narration, we mostly learn about the artwork’s history from the painting ‘herself’. She recounts her turbulent 300-year-history and lists her many illustrious owners, including Marie Antoinette, Napoleon and Queen Victoria. These are the novel’s only first-person sections; you can just imagine a voiceover from Helen Mirren or Judi Dench.

Max Gate by Damien Wilkins: This is a novel of Thomas Hardy’s last days, but we get an unusual glimpse into his household at Max Gate, Dorchester through the point-of-view of his housemaid, twenty-six-year-old Nellie Titterington. Ultimately I suspect a third-person omniscient voice would have worked better. In fact, some passages – recounting scenes Nellie is not witness to – are in the third person, which felt a bit like cheating. Fans familiar with the excellent Claire Tomalin biography might not learn much about Hardy and his household dynamics, but it was fun to spend some imaginary time at a place I once visited. [First published in New Zealand in 2013; releases in the US and UK on June 6th.]

Max Gate by Damien Wilkins: This is a novel of Thomas Hardy’s last days, but we get an unusual glimpse into his household at Max Gate, Dorchester through the point-of-view of his housemaid, twenty-six-year-old Nellie Titterington. Ultimately I suspect a third-person omniscient voice would have worked better. In fact, some passages – recounting scenes Nellie is not witness to – are in the third person, which felt a bit like cheating. Fans familiar with the excellent Claire Tomalin biography might not learn much about Hardy and his household dynamics, but it was fun to spend some imaginary time at a place I once visited. [First published in New Zealand in 2013; releases in the US and UK on June 6th.]

Dust by Michael Marder: A philosopher carries out an interdisciplinary study of dust: what it’s made of, what it means, and how it informs our metaphors. In itself, he points out, dust is neither positive nor negative, but we give it various cultural meanings. In the Bible, it is the very substance of mortality. Meanwhile “The war on dust, a hallmark of modern hygiene, reverberates with the political hygiene of the war on terror.” The contemporary profusion of allergies may, in fact, be an unintended consequence of our crusade against dust. The discussion is pleasingly wide-ranging, with some unexpected diversions – such as the metaphorical association between ‘stardust’ and celebrity – but also some impenetrable jargon. I’d be interested to try other titles from Bloomsbury’s “Object Lessons” series.

Dust by Michael Marder: A philosopher carries out an interdisciplinary study of dust: what it’s made of, what it means, and how it informs our metaphors. In itself, he points out, dust is neither positive nor negative, but we give it various cultural meanings. In the Bible, it is the very substance of mortality. Meanwhile “The war on dust, a hallmark of modern hygiene, reverberates with the political hygiene of the war on terror.” The contemporary profusion of allergies may, in fact, be an unintended consequence of our crusade against dust. The discussion is pleasingly wide-ranging, with some unexpected diversions – such as the metaphorical association between ‘stardust’ and celebrity – but also some impenetrable jargon. I’d be interested to try other titles from Bloomsbury’s “Object Lessons” series.

Foreword Reviews

How to Cure Bedwetting by Lane Robson (Oh, the interesting topics my work with self-published books introduces me to!): Explaining the anatomical and behavioral reasons behind bedwetting, the Calgary-based physician gives practical tips for curing the problem within six to twelve months. Throughout, the text generally refers to “pee” and “poop,” which detracts slightly from the professionalism of the work. All the same, this compendium of knowledge, drawing as it does on the author’s forty years of experience, should answer every possible question on the subject. Highly recommended to parents of younger elementary school children, this book will be an invaluable reference in tackling bedwetting.

Nudge

The Prophets of Eternal Fjord by Kim Leine: An epic novel about an unconventional priest, set in late-eighteenth-century Denmark and Greenland. This struck me as a cross between Carsten Jensen’s We, the Drowned, another historical saga from Denmark and one of my favorite novels of all time, and Michel Faber’s The Crimson Petal and the White. Like the former, it features perilous sea voyages and ambivalent father–son relationships; like the latter, it’s edgy and sexualized, full of lechery and bodily fluids. No airbrushing the more unpleasant aspects of history here. The entire story is told in the present tense, with no speech marks. It took me nearly a month and a half to read; by the end I felt I’d been on an odyssey as long and winding as Morten’s.

The Prophets of Eternal Fjord by Kim Leine: An epic novel about an unconventional priest, set in late-eighteenth-century Denmark and Greenland. This struck me as a cross between Carsten Jensen’s We, the Drowned, another historical saga from Denmark and one of my favorite novels of all time, and Michel Faber’s The Crimson Petal and the White. Like the former, it features perilous sea voyages and ambivalent father–son relationships; like the latter, it’s edgy and sexualized, full of lechery and bodily fluids. No airbrushing the more unpleasant aspects of history here. The entire story is told in the present tense, with no speech marks. It took me nearly a month and a half to read; by the end I felt I’d been on an odyssey as long and winding as Morten’s.

PANK

Still the Animals Enter by Jane Hilberry: A rich, strange, and gently erotic collection featuring diverse styles and blurring the lines between child and adult, human and animal, life and death through the language of metamorphosis. Ambivalence about the moments of transition between childhood and adulthood infuses Part One. Early on, “A Hole in the Fence” finishes on a whispered offer: “You could be part of this.” The message in this resonant collection, though, is that we already are a part of it: part of a shared life that moves beyond the individual family or even the human species. We are all connected—to the children we once were, to lovers and family members lost and found, and to the animals we watch in wonder.

Still the Animals Enter by Jane Hilberry: A rich, strange, and gently erotic collection featuring diverse styles and blurring the lines between child and adult, human and animal, life and death through the language of metamorphosis. Ambivalence about the moments of transition between childhood and adulthood infuses Part One. Early on, “A Hole in the Fence” finishes on a whispered offer: “You could be part of this.” The message in this resonant collection, though, is that we already are a part of it: part of a shared life that moves beyond the individual family or even the human species. We are all connected—to the children we once were, to lovers and family members lost and found, and to the animals we watch in wonder.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Relief Map by Rosalie Knecht: Lomath, Pennsylvania consists of a half-mile stretch between old textile mills and is home to just 150 people. During one unpredictable summer, blackouts and the arrival of an Eastern European fugitive draw the residents into a welter of paranoia and misguided choices. Our eyewitness to provincial commotion is 16-year-old Livy Marko, who considers herself plain and awkward – her childhood style was supplied by Anne of Green Gables and Goodwill. Knecht’s writing is marked by carefully chosen images and sounds. The novel maintains a languid yet subtly tense ambience. For Livy, coming of age means realizing actions always have consequences. Offbeat and atmospheric, this debut is probably too quiet to make a major splash, but has its gentle rewards.

Relief Map by Rosalie Knecht: Lomath, Pennsylvania consists of a half-mile stretch between old textile mills and is home to just 150 people. During one unpredictable summer, blackouts and the arrival of an Eastern European fugitive draw the residents into a welter of paranoia and misguided choices. Our eyewitness to provincial commotion is 16-year-old Livy Marko, who considers herself plain and awkward – her childhood style was supplied by Anne of Green Gables and Goodwill. Knecht’s writing is marked by carefully chosen images and sounds. The novel maintains a languid yet subtly tense ambience. For Livy, coming of age means realizing actions always have consequences. Offbeat and atmospheric, this debut is probably too quiet to make a major splash, but has its gentle rewards.

Shiny New Books

The Outrun by Amy Liptrot: Put simply, this is a memoir about Amy Liptrot’s slide into alcoholism and her subsequent recovery. Liptrot grew up on mainland Orkney, a tight-knit Scottish community she was eager to leave as a teenager but found herself returning to a decade later, washed up after the dissolute living and heartbreak she left behind in London. A simple existence, close to nature and connected to other people, was just what she needed during her first two years of sobriety. Her atmospheric writing about the magical Orkney Islands and their wildlife, rather than the slightly clichéd ruminating on alcoholism, is what sets the book apart. (On the Wellcome Prize shortlist.)

The Outrun by Amy Liptrot: Put simply, this is a memoir about Amy Liptrot’s slide into alcoholism and her subsequent recovery. Liptrot grew up on mainland Orkney, a tight-knit Scottish community she was eager to leave as a teenager but found herself returning to a decade later, washed up after the dissolute living and heartbreak she left behind in London. A simple existence, close to nature and connected to other people, was just what she needed during her first two years of sobriety. Her atmospheric writing about the magical Orkney Islands and their wildlife, rather than the slightly clichéd ruminating on alcoholism, is what sets the book apart. (On the Wellcome Prize shortlist.)

I also post reviews of most of my casual reading and skimming on Goodreads:

Look We Have Coming to Dover! by Daljit Nagra: The dialect was a bit too heavy for me in some of these poems about the Sikh experience in Britain. By far my favorite was “In a White Town,” which opens: “She never looked like other boys’ mums. / No one ever looked without looking again / at the pink kameez and balloon’d bottoms, // mustard-oiled trail of hair, brocaded pink / sandals and the smell of curry. That’s why / I’d bin the letters about Parents’ Evenings …”

Look We Have Coming to Dover! by Daljit Nagra: The dialect was a bit too heavy for me in some of these poems about the Sikh experience in Britain. By far my favorite was “In a White Town,” which opens: “She never looked like other boys’ mums. / No one ever looked without looking again / at the pink kameez and balloon’d bottoms, // mustard-oiled trail of hair, brocaded pink / sandals and the smell of curry. That’s why / I’d bin the letters about Parents’ Evenings …”

Work Like Any Other by Virginia Reeves: Between the blurb and the first paragraph, you already know everything that’s going to happen. I admire books that can keep you reading with interest even though you know exactly what’s coming, but this isn’t really one of those. Ultimately I would have preferred for the whole novel, rather than just alternating chapters, to be in Roscoe’s first-person voice, set wholly in prison (where he helps out in the library and with the guard dogs) but with brief flashbacks to his electricity siphoning and the circumstances of his manslaughter conviction. The writing is entirely capable, but the structure made it so I felt the story wasn’t worth my time.

Work Like Any Other by Virginia Reeves: Between the blurb and the first paragraph, you already know everything that’s going to happen. I admire books that can keep you reading with interest even though you know exactly what’s coming, but this isn’t really one of those. Ultimately I would have preferred for the whole novel, rather than just alternating chapters, to be in Roscoe’s first-person voice, set wholly in prison (where he helps out in the library and with the guard dogs) but with brief flashbacks to his electricity siphoning and the circumstances of his manslaughter conviction. The writing is entirely capable, but the structure made it so I felt the story wasn’t worth my time.

We Love You, Charlie Freeman by Kaitlyn Greenidge: The Freemans are raising Charlie, a chimpanzee, as part of their family for a Toneybee Institute experiment and teaching him to communicate via sign language. Flashbacks to the late 1920s bring an uncomfortable racial subtext to the surface, suggesting that the Toneybee has been involved in dodgy anthropological research over the decades. This is a deep and unsettling story of human–human interactions, even more so than human–animal interactions. I much preferred it to We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves.

We Love You, Charlie Freeman by Kaitlyn Greenidge: The Freemans are raising Charlie, a chimpanzee, as part of their family for a Toneybee Institute experiment and teaching him to communicate via sign language. Flashbacks to the late 1920s bring an uncomfortable racial subtext to the surface, suggesting that the Toneybee has been involved in dodgy anthropological research over the decades. This is a deep and unsettling story of human–human interactions, even more so than human–animal interactions. I much preferred it to We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves.

Love Like Salt by Helen Stevenson: Stevenson’s daughter Clara has cystic fibrosis, so I approached and enjoyed this as an illness memoir. However, it’s very scattered, with lots of seemingly irrelevant material included simply because it happened to the author: her mother’s dementia, their life in France, her work as a translator and her hobby of playing the piano, her older husband’s love for Italy and Italian literature, etc. Really the central drama is their seemingly idyllic life in France, Clara being bullied there, and the decision to move back to England (near Bristol), where the girls would attend a Quaker school on scholarships and Clara was enrolled in a widespread clinical trial with modest success. Enjoyable enough if you share some of the author’s interests.

Love Like Salt by Helen Stevenson: Stevenson’s daughter Clara has cystic fibrosis, so I approached and enjoyed this as an illness memoir. However, it’s very scattered, with lots of seemingly irrelevant material included simply because it happened to the author: her mother’s dementia, their life in France, her work as a translator and her hobby of playing the piano, her older husband’s love for Italy and Italian literature, etc. Really the central drama is their seemingly idyllic life in France, Clara being bullied there, and the decision to move back to England (near Bristol), where the girls would attend a Quaker school on scholarships and Clara was enrolled in a widespread clinical trial with modest success. Enjoyable enough if you share some of the author’s interests.

Springtime: A Ghost Story by Michelle de Kretser: Ghost story? Really? There’s very little in the way of suspense, and not too much plot either, in this Australia-set novella. I would expect tension to linger and questions to remain unanswered. Instead, the author exposes Frances’s ‘ghost’ as harmless. What I think de Kretser is trying to do here is show that ghosts can be people we have known and loved or, alternatively, places we have left behind. There is some nice descriptive writing (e.g. “three staked camellias stood as whitely upright as martyrs”), but not enough story to hold the interest.

Springtime: A Ghost Story by Michelle de Kretser: Ghost story? Really? There’s very little in the way of suspense, and not too much plot either, in this Australia-set novella. I would expect tension to linger and questions to remain unanswered. Instead, the author exposes Frances’s ‘ghost’ as harmless. What I think de Kretser is trying to do here is show that ghosts can be people we have known and loved or, alternatively, places we have left behind. There is some nice descriptive writing (e.g. “three staked camellias stood as whitely upright as martyrs”), but not enough story to hold the interest.

Let the Empire Down by Alexandra Oliver: This debut collection is heavily inspired by history and travel, as well as Serbian poetry and personal anecdote. I enjoyed the earlier poems, especially the ones with ABAB or ABBA rhyme schemes. My favorite was “Plans,” about a twenty-something manicurist who abandoned her talent for science to get ready cash: “A girl’s future should be full and bright, a marble, / but (alas for her) there is a catch: / we take on the immediate. Hope flags: / wishing to be wise and come out shining, / we pop a beaker over our own flame. / We do it cheerfully. We do it coldly.” The last quarter is devoted to poems about films, especially Italian cinema.

Let the Empire Down by Alexandra Oliver: This debut collection is heavily inspired by history and travel, as well as Serbian poetry and personal anecdote. I enjoyed the earlier poems, especially the ones with ABAB or ABBA rhyme schemes. My favorite was “Plans,” about a twenty-something manicurist who abandoned her talent for science to get ready cash: “A girl’s future should be full and bright, a marble, / but (alas for her) there is a catch: / we take on the immediate. Hope flags: / wishing to be wise and come out shining, / we pop a beaker over our own flame. / We do it cheerfully. We do it coldly.” The last quarter is devoted to poems about films, especially Italian cinema.

Vinegar Girl by Anne Tyler: This is the most fun I’ve had with the Hogarth Shakespeare series so far, as well as my favorite of the three Anne Tyler novels I’ve read. Yes, it’s set in Baltimore. Kate Battista, the utterly tactless preschool assistant, kept cracking me up. Her father, an autoimmune researcher, schemes for her to marry his lab assistant, Pyotr, so he can stay in the country after his visa expires. The plot twists of the final quarter felt a little predictable, but I was won over by the good-natured storytelling and prickly heroine. (I don’t know The Taming of the Shrew well enough to comment on how this functions as a remake.) Releases in June.

Vinegar Girl by Anne Tyler: This is the most fun I’ve had with the Hogarth Shakespeare series so far, as well as my favorite of the three Anne Tyler novels I’ve read. Yes, it’s set in Baltimore. Kate Battista, the utterly tactless preschool assistant, kept cracking me up. Her father, an autoimmune researcher, schemes for her to marry his lab assistant, Pyotr, so he can stay in the country after his visa expires. The plot twists of the final quarter felt a little predictable, but I was won over by the good-natured storytelling and prickly heroine. (I don’t know The Taming of the Shrew well enough to comment on how this functions as a remake.) Releases in June.

The Assistants by Camille Perri: At age 30, Tina Fontana has been a PA to media mogul Robert Barlow for six years. He’s worth millions; she lives in a tiny Brooklyn apartment. One day a mix-up in refunding expenses lands her with a check for $19,147. If she cashes it she can pay off her debts once and for all and no one at Titan Corporation will be any the wiser, right? This is a fun and undemanding read that will probably primarily appeal to young women. I would particularly recommend it to readers of Friendship by Emily Gould and A Window Opens by Elisabeth Egan. Releases May 3rd.

The Assistants by Camille Perri: At age 30, Tina Fontana has been a PA to media mogul Robert Barlow for six years. He’s worth millions; she lives in a tiny Brooklyn apartment. One day a mix-up in refunding expenses lands her with a check for $19,147. If she cashes it she can pay off her debts once and for all and no one at Titan Corporation will be any the wiser, right? This is a fun and undemanding read that will probably primarily appeal to young women. I would particularly recommend it to readers of Friendship by Emily Gould and A Window Opens by Elisabeth Egan. Releases May 3rd.

Carnet de Voyage by Craig Thompson: A sketchbook Thompson kept on his combined European book tour for Blankets and research trip for Habibi in March–May 2004. It doesn’t really work as a stand-alone graphic memoir because there isn’t much of a narrative, just a series of book signings, random encounters with friends and strangers, and tourism. My favorite two-page spread is about a camel ride he took into the Moroccan desert. I could also sympathize with his crippling hand pain (from all that drawing) and his “chaos tolerance” overload from the stress of travel.

Carnet de Voyage by Craig Thompson: A sketchbook Thompson kept on his combined European book tour for Blankets and research trip for Habibi in March–May 2004. It doesn’t really work as a stand-alone graphic memoir because there isn’t much of a narrative, just a series of book signings, random encounters with friends and strangers, and tourism. My favorite two-page spread is about a camel ride he took into the Moroccan desert. I could also sympathize with his crippling hand pain (from all that drawing) and his “chaos tolerance” overload from the stress of travel.

Rising Ground: A Search for the Spirit of Place by Philip Marsden: Some very nice writing indeed, but not much of a storyline. The book is something of a jumble of mythology, geology, prehistory, and more recent biographical information about some famous Cornish residents, overlaid on a gentle travel memoir. I enjoyed learning about the meanings of Cornish place names, in particular, and spotting locations I’ve visited.

Rising Ground: A Search for the Spirit of Place by Philip Marsden: Some very nice writing indeed, but not much of a storyline. The book is something of a jumble of mythology, geology, prehistory, and more recent biographical information about some famous Cornish residents, overlaid on a gentle travel memoir. I enjoyed learning about the meanings of Cornish place names, in particular, and spotting locations I’ve visited.

And my highest recommendation goes to…

Commonwealth by Ann Patchett: It all starts with an early 1960s christening party Los Angeles policeman Fix Keating is throwing for his younger daughter, Franny. DA Bert Cousins turns up, uninvited, with a bottle of gin the grateful guests quickly polish off in their fresh-squeezed orange juice. He also kisses the hostess, sparking a chain of events that will rearrange the Keating and Cousins families in the decades to come. The novel spends time with all six step-siblings, but Franny is definitely the main character – and likely an autobiographical stand-in for Patchett. As a waitress in Chicago, she meets a famous novelist who’s in a slump; the story of her childhood gives him his next bestseller but forces the siblings to revisit a tragic accident they never fully faced up to. Sophisticated and atmospheric; perfect for literary fiction fans in general and Patchett fans in particular. Releases September 13th.

by Ann Patchett: It all starts with an early 1960s christening party Los Angeles policeman Fix Keating is throwing for his younger daughter, Franny. DA Bert Cousins turns up, uninvited, with a bottle of gin the grateful guests quickly polish off in their fresh-squeezed orange juice. He also kisses the hostess, sparking a chain of events that will rearrange the Keating and Cousins families in the decades to come. The novel spends time with all six step-siblings, but Franny is definitely the main character – and likely an autobiographical stand-in for Patchett. As a waitress in Chicago, she meets a famous novelist who’s in a slump; the story of her childhood gives him his next bestseller but forces the siblings to revisit a tragic accident they never fully faced up to. Sophisticated and atmospheric; perfect for literary fiction fans in general and Patchett fans in particular. Releases September 13th.

Philip Rhayader is a lonely bird artist on the Essex marshes by an abandoned lighthouse. “His body was warped, but his heart was filled with love for wild and hunted things. He was ugly to look upon, but he created great beauty.” One day a little girl, Fritha, brings him an injured snow goose and he puts a splint on its wing. The recovered bird becomes a friend to them both, coming back each year to spend time at Philip’s makeshift bird sanctuary. As Fritha grows into a young woman, she and Philip fall in love (slightly creepy), only for him to leave to help with the evacuation of Dunkirk. This is a melancholy and in some ways predictable little story. It was originally published in the Saturday Evening Post in 1940 and became a book the following year. I read a lovely version illustrated by Angela Barrett. It’s the second of Gallico’s animal fables I’ve read; I slightly preferred

Philip Rhayader is a lonely bird artist on the Essex marshes by an abandoned lighthouse. “His body was warped, but his heart was filled with love for wild and hunted things. He was ugly to look upon, but he created great beauty.” One day a little girl, Fritha, brings him an injured snow goose and he puts a splint on its wing. The recovered bird becomes a friend to them both, coming back each year to spend time at Philip’s makeshift bird sanctuary. As Fritha grows into a young woman, she and Philip fall in love (slightly creepy), only for him to leave to help with the evacuation of Dunkirk. This is a melancholy and in some ways predictable little story. It was originally published in the Saturday Evening Post in 1940 and became a book the following year. I read a lovely version illustrated by Angela Barrett. It’s the second of Gallico’s animal fables I’ve read; I slightly preferred

“A Search for the World’s Purest, Deepest Snowfall” reads the subtitle on the cover. English set out from his home in London for two years of off-and-on travel in snowy places, everywhere from Greenland to Washington State. In Jericho, Vermont, he learns about Wilson Bentley, an amateur scientist who was the first to document snowflake shapes through microscope photographs. In upstate New York, he’s nearly stranded during the Blizzard of 2006. He goes skiing in France and learns about the deadliest avalanches – Britain’s worst was in Lewes in 1836. In Scotland’s Cairngorms, he learns how those who work in the ski industry are preparing for the 60–80% reduction of snow predicted for this century. An appendix dubbed “A Snow Handbook” gives some technical information on how snow forms, what the different crystal shapes are called, and how to build an igloo, along with whimsical lists of 10 snow stories (I’ve read six), 10 snowy films, etc.

“A Search for the World’s Purest, Deepest Snowfall” reads the subtitle on the cover. English set out from his home in London for two years of off-and-on travel in snowy places, everywhere from Greenland to Washington State. In Jericho, Vermont, he learns about Wilson Bentley, an amateur scientist who was the first to document snowflake shapes through microscope photographs. In upstate New York, he’s nearly stranded during the Blizzard of 2006. He goes skiing in France and learns about the deadliest avalanches – Britain’s worst was in Lewes in 1836. In Scotland’s Cairngorms, he learns how those who work in the ski industry are preparing for the 60–80% reduction of snow predicted for this century. An appendix dubbed “A Snow Handbook” gives some technical information on how snow forms, what the different crystal shapes are called, and how to build an igloo, along with whimsical lists of 10 snow stories (I’ve read six), 10 snowy films, etc.

This has a very similar format and scope to The Snow Tourist, with Campbell ranging from Greenland and continental Europe to the USA in her search for the science and stories of ice. For English’s chapter on skiing, substitute a section on ice skating. I only skimmed this one because – in what I’m going to put down to a case of reader–writer mismatch – I started it three times between November 2018 and now and could never get further than page 60. See these reviews from

This has a very similar format and scope to The Snow Tourist, with Campbell ranging from Greenland and continental Europe to the USA in her search for the science and stories of ice. For English’s chapter on skiing, substitute a section on ice skating. I only skimmed this one because – in what I’m going to put down to a case of reader–writer mismatch – I started it three times between November 2018 and now and could never get further than page 60. See these reviews from  The travails of his long trial runs with the dogs – the sled flipping over, having to walk miles after losing control of the dogs, being sprayed in the face by multiple skunks – sound bad enough, but once the Iditarod begins the misery ramps up. The course is nearly 1200 miles, over 17 days. It’s impossible to stay warm or get enough food, and a lack of sleep leads to hallucinations. At one point he nearly goes through thin ice. At another he’s run down by a moose. He also watches in horror as a fellow contestant kicks a dog to death.

The travails of his long trial runs with the dogs – the sled flipping over, having to walk miles after losing control of the dogs, being sprayed in the face by multiple skunks – sound bad enough, but once the Iditarod begins the misery ramps up. The course is nearly 1200 miles, over 17 days. It’s impossible to stay warm or get enough food, and a lack of sleep leads to hallucinations. At one point he nearly goes through thin ice. At another he’s run down by a moose. He also watches in horror as a fellow contestant kicks a dog to death. Two nonfiction books entitled Wintering:

Two nonfiction books entitled Wintering:

March by Geraldine Brooks (2005): The best Civil War novel I’ve read. The best slavery novel I’ve read. One of the best historical novels I’ve ever read, period. Brooks’s second novel uses Little Women as its jumping-off point but is very much its own story. The whole is a perfect mixture of what’s familiar from history and literature and what Brooks has imagined.

March by Geraldine Brooks (2005): The best Civil War novel I’ve read. The best slavery novel I’ve read. One of the best historical novels I’ve ever read, period. Brooks’s second novel uses Little Women as its jumping-off point but is very much its own story. The whole is a perfect mixture of what’s familiar from history and literature and what Brooks has imagined. Marlena by Julie Buntin (2017): The northern Michigan setting pairs perfectly with the novel’s tone of foreboding: you have a sense of these troubled teens being isolated in their clearing in the woods, and from one frigid winter through a steamy summer and into the chill of the impending autumn, they have to figure out what in the world they are going to do with their terrifying freedom. It’s basically a flawless debut, one I can’t recommend too highly.

Marlena by Julie Buntin (2017): The northern Michigan setting pairs perfectly with the novel’s tone of foreboding: you have a sense of these troubled teens being isolated in their clearing in the woods, and from one frigid winter through a steamy summer and into the chill of the impending autumn, they have to figure out what in the world they are going to do with their terrifying freedom. It’s basically a flawless debut, one I can’t recommend too highly. Reading in the Dark by Seamus Deane (1996): Ireland’s internecine violence is the sinister backdrop to this family’s everyday sorrows, including the death of a child and the mother’s shaky mental health. The book captures all the magic, uncertainty and heartache of being a child, in crisp scenes I saw playing out in my mind.

Reading in the Dark by Seamus Deane (1996): Ireland’s internecine violence is the sinister backdrop to this family’s everyday sorrows, including the death of a child and the mother’s shaky mental health. The book captures all the magic, uncertainty and heartache of being a child, in crisp scenes I saw playing out in my mind. The Life and Loves of Lena Gaunt by Tracy Farr (2013): Lena Gaunt: early theremin player, grande dame of electronic music, and opium addict. I loved how Farr evokes the strangeness and energy of theremin music, and how sound waves find a metaphorical echo in the ocean’s waves – swimming is Lena’s other great passion.

The Life and Loves of Lena Gaunt by Tracy Farr (2013): Lena Gaunt: early theremin player, grande dame of electronic music, and opium addict. I loved how Farr evokes the strangeness and energy of theremin music, and how sound waves find a metaphorical echo in the ocean’s waves – swimming is Lena’s other great passion. Late Nights on Air by Elizabeth Hay (2007): A tight-knit cast gathers around the local radio station in Yellowknife, a small city in Canada’s Northwest Territories: Harry and Gwen, refugees from Ontario starting new lives; Dido, an alluring Dutch newsreader; Ralph, the freelance book reviewer; menacing Eddie; and pious Eleanor. This is a marvellous story of quiet striving and dislocation; I saw bits of myself in each of the characters, and I loved the extreme setting, both mosquito-ridden summer and bitter winter.

Late Nights on Air by Elizabeth Hay (2007): A tight-knit cast gathers around the local radio station in Yellowknife, a small city in Canada’s Northwest Territories: Harry and Gwen, refugees from Ontario starting new lives; Dido, an alluring Dutch newsreader; Ralph, the freelance book reviewer; menacing Eddie; and pious Eleanor. This is a marvellous story of quiet striving and dislocation; I saw bits of myself in each of the characters, and I loved the extreme setting, both mosquito-ridden summer and bitter winter. The Leavers by Lisa Ko (2017): An ambitious and satisfying novel set in New York and China, with major themes of illegal immigration, searching for a mother and a sense of belonging, and deciding what to take with you from your past. This was hand-picked by Barbara Kingsolver for the 2016 PEN/Bellwether Prize for Socially Engaged Fiction.

The Leavers by Lisa Ko (2017): An ambitious and satisfying novel set in New York and China, with major themes of illegal immigration, searching for a mother and a sense of belonging, and deciding what to take with you from your past. This was hand-picked by Barbara Kingsolver for the 2016 PEN/Bellwether Prize for Socially Engaged Fiction. The Invisible Bridge by Julie Orringer (2010): Hungarian Jew Andras Lévi travels from Budapest to Paris to study architecture, falls in love with an older woman who runs a ballet school, and – along with his parents, brothers, and friends – has to adjust to the increasingly strict constraints on Jews across Europe in 1937–45. It’s all too easy to burn out on World War II narratives these days, but this is among the very best I’ve read.

The Invisible Bridge by Julie Orringer (2010): Hungarian Jew Andras Lévi travels from Budapest to Paris to study architecture, falls in love with an older woman who runs a ballet school, and – along with his parents, brothers, and friends – has to adjust to the increasingly strict constraints on Jews across Europe in 1937–45. It’s all too easy to burn out on World War II narratives these days, but this is among the very best I’ve read. The Sparrow by Mary Doria Russell (1996): For someone like me who struggles with sci-fi at the best of times, this is just right: the alien beings are just different enough from humans for Russell to make fascinating points about gender roles, commerce and art, but not so peculiar that you have trouble believing in their existence. All of the crew members are wonderful, distinctive characters, and the novel leaves you with so much to think about: unrequited love, destiny, faith, despair, and the meaning to be found in life.

The Sparrow by Mary Doria Russell (1996): For someone like me who struggles with sci-fi at the best of times, this is just right: the alien beings are just different enough from humans for Russell to make fascinating points about gender roles, commerce and art, but not so peculiar that you have trouble believing in their existence. All of the crew members are wonderful, distinctive characters, and the novel leaves you with so much to think about: unrequited love, destiny, faith, despair, and the meaning to be found in life. Salt Creek by Lucy Treloar (2015): Hester Finch is looking back from the 1870s – when she is a widowed teacher settled in England – to the eight ill-fated years her family spent at Salt Creek, a small (fictional) outpost in South Australia, in the 1850s–60s. This is one of the very best works of historical fiction I’ve read; it’s hard to believe it’s Treloar’s debut novel.

Salt Creek by Lucy Treloar (2015): Hester Finch is looking back from the 1870s – when she is a widowed teacher settled in England – to the eight ill-fated years her family spent at Salt Creek, a small (fictional) outpost in South Australia, in the 1850s–60s. This is one of the very best works of historical fiction I’ve read; it’s hard to believe it’s Treloar’s debut novel. Christmas Days: 12 Stories and 12 Feasts for 12 Days by Jeanette Winterson (2016): I treated myself to this new paperback edition with part of my birthday book token and it was a perfect read for the week leading up to Christmas. The stories are often fable-like, some spooky and some funny. Most have fantastical elements and meaningful rhetorical questions. Winterson takes the theology of Christmas seriously. A gorgeous book I’ll return to year after year.

Christmas Days: 12 Stories and 12 Feasts for 12 Days by Jeanette Winterson (2016): I treated myself to this new paperback edition with part of my birthday book token and it was a perfect read for the week leading up to Christmas. The stories are often fable-like, some spooky and some funny. Most have fantastical elements and meaningful rhetorical questions. Winterson takes the theology of Christmas seriously. A gorgeous book I’ll return to year after year. Available Light by Marge Piercy (1988): The subjects are diverse: travels in Europe, menstruation, identifying as a Jew as well as a feminist, scattering her father’s ashes, the stresses of daily life, and being in love. Some of my favorites were about selectively adhering to the lessons her mother taught her, how difficult it is for a workaholic to be idle, and wrestling the deity for words.

Available Light by Marge Piercy (1988): The subjects are diverse: travels in Europe, menstruation, identifying as a Jew as well as a feminist, scattering her father’s ashes, the stresses of daily life, and being in love. Some of my favorites were about selectively adhering to the lessons her mother taught her, how difficult it is for a workaholic to be idle, and wrestling the deity for words. Deep Country: Five Years in the Welsh Hills by Neil Ansell (2011): One of the most memorable nature/travel books I’ve ever read; a modern-day Walden. Ansell’s memoir is packed with beautiful lines as well as philosophical reflections on the nature of the self and the difference between isolation and loneliness.

Deep Country: Five Years in the Welsh Hills by Neil Ansell (2011): One of the most memorable nature/travel books I’ve ever read; a modern-day Walden. Ansell’s memoir is packed with beautiful lines as well as philosophical reflections on the nature of the self and the difference between isolation and loneliness. Boy by Roald Dahl

Boy by Roald Dahl  Ali: A Life by Jonathan Eig (2017): It’s a riveting account of outliving segregation and developing a personal style and world-beating confidence; it’s a sobering tale of facing consequences and having your own body fail you. I’m the furthest thing from a sports fan you could imagine, but I approached this as a book about a cultural icon and read it with a spirit of curiosity about how Eig would shape this life story and separate the facts from the legend. I loved it.