Recent Poetry Releases by Allison Blevins, Kit Fan, Lisa Kelly and Laura Scott

I’m catching up on four 2023 poetry collections from independent publishers, three of them from Carcanet Press, which so graciously keeps me stocked up with work by contemporary poets. Despite the wide range of subject matter, style and technique, nature imagery and erotic musings are links. From each I’ve chosen one short poem as a representative.

Cataloguing Pain by Allison Blevins

Last year I reviewed Allison Blevins’ Handbook for the Newly Disabled. This shares its autobiographical consideration of chronic illness and queer parenting. Specifically, she looks back to her MS diagnosis and three IVF pregnancies, and her spouse’s transition. Both partners were undergoing bodily transformations and coming into new identities, the one as disabled and the other as a man. In later poems she calls herself “The shell”, while “Elegy for My Wife,” which closes Part I, makes way for references to “my husband” in Part II.

Last year I reviewed Allison Blevins’ Handbook for the Newly Disabled. This shares its autobiographical consideration of chronic illness and queer parenting. Specifically, she looks back to her MS diagnosis and three IVF pregnancies, and her spouse’s transition. Both partners were undergoing bodily transformations and coming into new identities, the one as disabled and the other as a man. In later poems she calls herself “The shell”, while “Elegy for My Wife,” which closes Part I, makes way for references to “my husband” in Part II.

“I won’t wail for your dead name. I don’t mean that violence. I wish for a word other than elegy to explain how some of this feels like goodbye.”

In unrhymed couplets or stanzas and bittersweet paragraphs, Blevins marshals metaphors from domestic life – colours, food, furniture, gardening – to chart the changes that pain and disability force onto their family’s everyday routines. “Fall Risk” and “Fly Season” are particular highlights. This is a potent and frankly sexual text for readers drawn to themes of health and queer family-making (see also my Three on a Theme post on that topic).

Published by YesYes Books on 19 April. With thanks to the author for the advanced e-copy for review.

The Ink Cloud Reader by Kit Fan

Kit Fan was raised in Hong Kong and moved to the UK as an adult. This is his third collection of poetry. “Suddenly” tells a version of his life story in paragraphs or single lines that all incorporate the title word (with an ironic nod, through the epigraph, to Elmore Leonard’s writing ‘rule’ that “suddenly” should never be used). The “IF” statements of “Delphi” then ponder possible future events; a trip to hospital sees him contemplating his mortality (“Glück,” written as a miniature three-act play) and appreciating tokens of beauty (“Geraniums in May”). “Yew,” unusually, is a modified sonnet where every line rhymes.

Kit Fan was raised in Hong Kong and moved to the UK as an adult. This is his third collection of poetry. “Suddenly” tells a version of his life story in paragraphs or single lines that all incorporate the title word (with an ironic nod, through the epigraph, to Elmore Leonard’s writing ‘rule’ that “suddenly” should never be used). The “IF” statements of “Delphi” then ponder possible future events; a trip to hospital sees him contemplating his mortality (“Glück,” written as a miniature three-act play) and appreciating tokens of beauty (“Geraniums in May”). “Yew,” unusually, is a modified sonnet where every line rhymes.

As the collection’s title suggests, it is equally interested in the natural and the human. There are poems describing the cycles of the moon (the lines of “Moon Salutation” curve into a half-moon parabola) and the wind. Ink pulls together calligraphy, the Chinese zodiac and literature. “The Art of Reading,” which commemorates important moments, real and imaginary, of the poet’s reading life, was a favourite of mine, as was “Derek Jarman’s Garden.” Fan also writes of memory and travels – including to the underworld. His relationship with his husband is a subtle background subject. (“Even though we’ve lived together for nearly twenty years and are always reading sometimes I can’t read you at all which I guess is a good thing”). It’s an opulent and allusive work that has made me eager to try more by Fan. Luckily, I have his debut novel (passed on to me by Laura T.) on the shelf.

Readalike: Moving House by Theophilus Kwek

Published on 27 April. With thanks to Carcanet Press for the advanced e-copy for review.

The House of the Interpreter by Lisa Kelly

Lisa Kelly’s concern with deafness is sure to bring to mind Raymond Antrobus and Ilya Kaminsky, but I prefer her work. Kelly is half-Danish and has single-sided deafness, and in Part I of this second collection, entitled “Chamber,” her poems engage with questions of split identity:

Lisa Kelly’s concern with deafness is sure to bring to mind Raymond Antrobus and Ilya Kaminsky, but I prefer her work. Kelly is half-Danish and has single-sided deafness, and in Part I of this second collection, entitled “Chamber,” her poems engage with questions of split identity:

Is this what it is like for us all? Always having to relearn home

with a strange tongue and alien hands, prepared to open our mouths

as if to beg, to touch tongue-tip with fingertip to reveal ourselves?

The title poem relishes the absurdities of telephone communication, closing with:

In the House of the Interpreter,

Oralism and Manualism, like Passion and Patience,

are rewarded differently and at different times.

Hello, this is your Interpreter. What is your wishlist?

This section ends with “#WhereIsTheInterpreter,” about the Deaf community’s outrage that the Prime Minister’s Covid briefings were not simultaneously translated into BSL.

Bizarrely but delightfully, Kelly then moves onto “Oval Window,” a sequence of alliteration-rich poems about fungi. “Mycology Abecedarian” is a joyful list of species’ common names, while “Mycelium” notes how mushrooms show that different ways of evolution and reproduction are possible. “Darning Mushroom” even combines images of fungi and holey socks. Part III, “Canal,” is a miscellany of autobiographical poems and homages to Faith Ringgold, full of references to colour, language, nature and travel.

Readalike: In the Quaker Hotel by Helen Tookey

Published on 27 April. With thanks to Carcanet Press for the advanced e-copy for review.

The Fourth Sister by Laura Scott

Back in 2019 I reviewed Laura Scott’s debut collection, So Many Rooms. Her second book reflects some of the same preoccupations: art, birds, colour and Russian literature. Chekhov is a recurring point of reference across the two; here, for instance, we have a found poem composed of excerpts from his letters. Scott also writes about the deaths of her parents, voicing resentment towards her father and remarking on life’s irony. As the title suggests, her family constellation includes sisters. Her godparents loom surprisingly large; her godmother was, apparently, a spy. My favourite of the poems, “Still Life,” imagines the whole of life being prized as a glass in an exhibit, appealingly pristine and praiseworthy in comparison to what we usually perceive: “the raggy sprawl of a life … the wrong turns and longing of it.” Elsewhere, metaphors are drawn from the theatre: performing lines, taking items from a wardrobe. I loved the way the pull of nostalgia is set up in opposition to the now.

Back in 2019 I reviewed Laura Scott’s debut collection, So Many Rooms. Her second book reflects some of the same preoccupations: art, birds, colour and Russian literature. Chekhov is a recurring point of reference across the two; here, for instance, we have a found poem composed of excerpts from his letters. Scott also writes about the deaths of her parents, voicing resentment towards her father and remarking on life’s irony. As the title suggests, her family constellation includes sisters. Her godparents loom surprisingly large; her godmother was, apparently, a spy. My favourite of the poems, “Still Life,” imagines the whole of life being prized as a glass in an exhibit, appealingly pristine and praiseworthy in comparison to what we usually perceive: “the raggy sprawl of a life … the wrong turns and longing of it.” Elsewhere, metaphors are drawn from the theatre: performing lines, taking items from a wardrobe. I loved the way the pull of nostalgia is set up in opposition to the now.

Published on 23 February. With thanks to Carcanet Press for the advanced e-copy for review.

Read any good poetry recently?

Solidarity with Ukraine

I don’t think I realized how serious the Russian invasion of Ukraine was until I heard a neighbour who is in the Royal Navy speak of it in the same breath as 9/11.

It is so hard to predict the end game. Wars can last years, even decades, and a situation like this could draw many more countries in. Like with Covid, there could be much longer term effects than we’re currently expecting.

I attended a candlelit vigil for Ukraine in the town square on Friday.

I donated to the Disasters Emergency Committee’s Ukraine Humanitarian Appeal at church yesterday morning, and will donate more. (Those in other countries might choose to send money through Doctors Without Borders, the Red Cross, or UNICEF.)

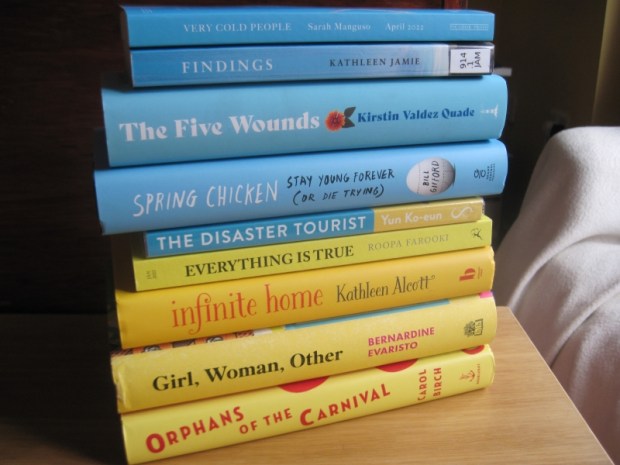

And I was prompted by a friend’s post to assemble this “Solidarity Stack” on Instagram over the weekend:

But I still feel like I have done so little.

I can hardly bear to keep up with the news; we don’t have a television or get a newspaper and I never listen to the radio, but I do see the headlines through my Facebook and Twitter feeds. Some heartening stories, but mostly horrible ones.

I wish I knew more about Ukraine. The only books I can think of that I’ve read by Ukrainians and Ukrainian Americans are Deaf Republic by Ilya Kaminsky, Death and the Penguin by Andrey Kurkov*, and My Dead Parents by Anya Yurchyshyn. There is a Ukraine setting to The Summer Guest by Alison Anderson, and Henry Marsh goes on medical missions to Ukraine in Do No Harm. Everything Is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer is about his Ukrainian Jewish heritage (as is his mother Esther’s I Want You to Know We’re Still Here); The Reason Why by Cecil Woodham-Smith and The Rose of Sebastopol by Katharine McMahon are about the Crimean War.

Over the past couple of weeks a number of Ukrainian reading lists have come out, like this one from Book Riot. Ron Charles (of the Washington Post) also put me onto I Will Die in a Foreign Land by Kalani Pickhart, which is about the 2014 revolution in Ukraine (when Putin tried to annex the Crimea). A portion of her proceeds will be donated to the Ukrainian Red Cross.

*Apparently on a most wanted list for his vocal opposition to Putin; his work has been banned in Russia since 2014.

The Vaster Wilds by Lauren Groff (Riverhead/Hutchinson Heinemann, 12 September): Groff’s fifth novel combines visceral detail and magisterial sweep as it chronicles a runaway Jamestown servant’s struggle to endure the winter of 1610. Flashbacks to traumatic events seep into her mind as she copes with the harsh reality of life in the wilderness. The style is archaic and postmodern all at once. Evocative and affecting – and as brutal as anything Cormac McCarthy wrote. A potent, timely fable as much as a historical novel. (Review forthcoming for Shelf Awareness.)

The Vaster Wilds by Lauren Groff (Riverhead/Hutchinson Heinemann, 12 September): Groff’s fifth novel combines visceral detail and magisterial sweep as it chronicles a runaway Jamestown servant’s struggle to endure the winter of 1610. Flashbacks to traumatic events seep into her mind as she copes with the harsh reality of life in the wilderness. The style is archaic and postmodern all at once. Evocative and affecting – and as brutal as anything Cormac McCarthy wrote. A potent, timely fable as much as a historical novel. (Review forthcoming for Shelf Awareness.)

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris: This debut collection addresses the symptoms and side effects of breast cancer treatment at age 36, but often in oblique or cheeky ways – it can be no mistake that “assistance” appears two lines before a mention of haemorrhoids, for instance, even though it closes an epithalamium distinguished by its gentle sibilance (Farris’s husband is Ukrainian American poet Ilya Kaminsky.) She crafts sensual love poems, and exhibits Japanese influences. (Review forthcoming at The Rumpus.)

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris: This debut collection addresses the symptoms and side effects of breast cancer treatment at age 36, but often in oblique or cheeky ways – it can be no mistake that “assistance” appears two lines before a mention of haemorrhoids, for instance, even though it closes an epithalamium distinguished by its gentle sibilance (Farris’s husband is Ukrainian American poet Ilya Kaminsky.) She crafts sensual love poems, and exhibits Japanese influences. (Review forthcoming at The Rumpus.)