From the Dylan Thomas Prize Shortlist: Seven Steeples & I’m a Fan

The Swansea University International Dylan Thomas Prize recognizes the best published work in the English language written by an author aged 39 or under. All literary genres are eligible, so the shortlist contains a poetry collection as well as novels and short stories.

I’ve read half of the shortlist (also including Warsan Shire’s poems) and would be interested in trying the rest if I can source the two short story collections; Limberlost is at my library. The winner will be announced at 8 p.m. BST on Thursday 11 May.

Seven Steeples by Sara Baume

Isabel and Simon arrive one January at a shabby rental house in coastal Ireland overlooked by a mountain, in the middle of nowhere. They’d been menial workers in Dublin and met climbing a mountain, but somehow never seem to get around to climbing their new local peak. In moving here, these “two solitary misanthropes” are essentially rejecting society and kin; Baume describes them as “post-family.” It appears that they’re post-employment as well – there is never a single reference to how they pay the rent and buy the hipster foods they favour. Could young people’s savings really fund eight years’ rural living?

It’s an appealingly anti-consumerist vision, anyway: They arrive with one van-load of stuff and their adopted dogs, Pip and Voss, and otherwise make do with a haphazard collection of secondhand belongings left by previous tenants or donated by their estranged families. The house starts to fall apart around them, but for the most part they adjust to the decay rather than do anything to reverse it. “They had become poor and shabby without noticing … accustomed to disrepair”; theirs is a “personalized squalor.”

Bell and Sigh become increasingly hermit-like, with entrenched ways of doing things. Baume several times describes their compost bin, which struck me as a perfect image for how the stuff of daily life builds up and beds down into the foundation of personalities and a relationship. The fact that they only have each other (and the dogs) for company explains how they adopt each other’s mannerisms, develop a private language, and even conflate their separate memories. The starkest symbol of their refusal of societal norms comes when they miss a clock change and effectively live in their own time zone.

Bell and Sigh become increasingly hermit-like, with entrenched ways of doing things. Baume several times describes their compost bin, which struck me as a perfect image for how the stuff of daily life builds up and beds down into the foundation of personalities and a relationship. The fact that they only have each other (and the dogs) for company explains how they adopt each other’s mannerisms, develop a private language, and even conflate their separate memories. The starkest symbol of their refusal of societal norms comes when they miss a clock change and effectively live in their own time zone.

I recognized from Spill Simmer Falter Wither and handiwork several elements that reflect Baume’s interests: nature imagery, dogs, and daily routines. She gives a clear sense of time’s passage and the seasons’ turning, of repetition and attrition and ageing. I wearied of the descriptive passages and hoped that at some point there would be some action and dialogue to counterbalance them, but that is not what this novel is about. Occasional flashes from the point-of-view of a mouse in the house, or a spider in the van, tell you that Baume’s scope is wider. This is in fact an allegory about impermanence, from a mountain’s-eye view.

Although I was frustrated with the central characters’ jolly incompetence (“Just buy leashes and a tick twister, you idiots!” I felt like shouting at them after yet another mention of the dogs killing cats and rabbits; and of the difficulty of removing ticks from their coats), I recognized how easy it is to get stuck in lazy habits; how easy it is to live provisionally, as if all is temporary and not your real existence.

Baume spaces lines and paragraphs almost like hybrid poetry and indulges in overwriting in places. Because of the dearth of action, this was a slog of a months-long read for me, but I admired it in the end and enjoyed it more than the other two books of hers that I’ve read.

If you admire lyrical prose and are okay with little to no plot in a novel, you should get on fine with this one. Or it might be that it requires the right time or reading mood, when you’re after something quiet.

Having read more by Dylan Thomas now, I think this is exactly the sort of place-specific and playful, stylized prose that the prize named after him is looking for. So, I’ll predict Baume as the winner.

With thanks to Tramp Press for the free e-copy for review.

I’m a Fan by Sheena Patel

This was one of my correct predictions for the Women’s Prize longlist; I’d heard a lot about it from Best of 2022 roundups and it seemed like the kind of edgy title they might recognise. It’s also perfect for the Dylan Thomas Prize list because of how voice-driven it is. The unnamed narrator, a woman of colour in her early thirties, muses on art, entitlement, obsession, social media and sex in short titled sections ranging from one paragraph to a few pages long. The twin objects of her fanaticism are “the man I want to be with,” who is married and generally keeps her at arm’s length, and “the woman I am obsessed with,” a lifestyle influencer who, like herself, is one of this man’s girlfriends on the side. She stalks the woman via her impeccably curated Instagram images.

The narrator has a boyfriend, in fact, a peculiarly perfect-sounding one even, but takes him for granted in her compulsive search for indiscriminate sexual experience (also including a female co-worker she calls “the Peach”). They end up parting ways and she moves back in with her parents, an ignominious retreat from attempted adulting.

The narrator has a boyfriend, in fact, a peculiarly perfect-sounding one even, but takes him for granted in her compulsive search for indiscriminate sexual experience (also including a female co-worker she calls “the Peach”). They end up parting ways and she moves back in with her parents, an ignominious retreat from attempted adulting.

She reminded me a bit of Bell and Sigh for her haplessness, but whereas the matter of having children literally never arises for them, the question of motherhood is a background niggle for her (“I thought I had the rest of my life to make this decision but I realise I am on a clock and it runs differently for me. I am female. There was never much time and I’ve wasted so much already”; “I want to gain immortality because of my brain and not because of the potential of my womb”). As the novella goes on, she even considers weaponising her fertility as a way of entrapping her crush.

I was reasonably engaged with the narrator’s deliberations about taste and autobiographical influences, but overall found this rather indulgent, slight and repetitive. Books about social media – this reminded me most of Adults by Emma Jane Unsworth – are in danger of becoming irrelevant all too quickly. The sexual frankness fell on the wrong side of unpleasant for me, and the format for referring to other characters leads to inelegant phrasing like “The man I want to be with’s work centres around conflict”. Something like Luster has that little bit more individuality and energy. (Secondhand – charity shop purchase)

Review: Service by Sarah Gilmartin

The comparison with Sweetbitter, one of my favourite debuts of the past decade, drew me to Service, and it’s an apt one. Irish writer Sarah Gilmartin’s second novel is a before-and-after set partly in the stressful atmosphere of a fine dining restaurant in Dublin. Head chef Daniel Costello worked his way up from an inner-city childhood and teenage carvery-pub job to a two-Michelin-starred establishment known as T. But then came a fall: accusations of sexual assault from several female former employees led to the restaurant’s temporary closure and a high-profile court trial. Daniel maintains his innocence. His lawyer plans to cast shade on the lead waitress’ reputation, and question her failure to come forward until one year after the alleged rape.

Three alternating first-person narrators fill in the background of the macho restaurant world and the Costellos’ marriage. First is Hannah Blake, a former waitress who is not involved in the current lawsuit but has her own stories to tell about Daniel, who treated her as a protégée during the brief time she worked at T while she was a university student. “I’ve never felt as alive as I did that summer,” she writes; it was thrilling for a girl from Tipperary to be at the heart of Dublin’s culinary life and to have a world-leading chef believe her palate was worth training. We also hear from Daniel himself, and then his wife Julie, who begrudgingly supports Daniel but is furious with him for the negative attention the trial has brought her and their two sons. Some family members and neighbours have started avoiding them.

Gilmartin invites the reader to have sympathy for all the protagonists, even when it gets complicated. There was a point about three-quarters of the way through when I had to rethink who I felt sorry for and why. I would have liked a few more restaurant scenes to balance out the aftermath, but that is a minor quibble. This is a solid #MeToo novel with pacey, engaging writing and well-rounded characters. It’s made me eager to go back and catch up on the author’s debut, Dinner Party: A Tragedy.

My rating:

Service was published on 4 May. With thanks to Pushkin Press for the proof copy for review.

Update: Sarah Gilmartin kindly answered a question another blogger and I put to her, about how she decided on, and brought to life, these three narrators.

As a writer I’m drawn to ambivalence, ambiguity, grey areas. I’m curious about how people work, how they behave under pressure, when they think no one is watching, our public and private selves, all of that is the bones of literature. I wanted to tell a story about the abuse of power from different perspectives as I felt it was a subject that could potentially have multiple interpretations. I was interested in nuance and in leaving enough space for the reader to make up their own mind.

With Julie, I was struck that when you hear or read about MeToo stories in the media, one person you never or rarely hear from is the partner of the abuser. Certainly they’re not the most important voice in the scenario – the victim is – but you do think, or at least I do, what must it feel like for the partner of the predator? A woman whose life is being ripped apart in a different way by the same man. I wanted to know more about women in this position. In their own words. With Hannah, we have a different, younger, in some ways closer-to-the-action female perspective. Although she’s in her 30s now, in many ways Hannah is stuck in the past, her summer at the restaurant, as survivors of trauma often are, trying to get on with things but being continually brought back to the point where their lives were derailed. She’s also our guide to the restaurant world, which can often be very colourful and entertaining. Finally, with Daniel, for me the story didn’t feel cohesive without his perspective. He was a compelling character to write, a talented man, celebrated in his field, who has clearly defined private and public personas, and an aura of false humility; he’s a self-fashioned art monster. Then on another level, he’s a predator, with a huge amount of ego and vanity.

All three characters were interesting to me in their own right, which is key, and then they also had important things to contribute with regards to the subject matter of the book. I didn’t do a huge amount of research – read a lot about MeToo in the media, watched some Masterchef – but I worked as a waitress myself in my 20s so had a good idea of the world, the highs and lows, stresses and perks. Characters, once I have an idea of who they are, how they operate and what they want, tend to grow organically on the page. That’s the beauty of fiction!

A Contemporary Classic: Foster by Claire Keegan (#NovNov22)

This year for Novellas in November, Cathy and I chose to host one overall buddy read, Foster by Claire Keegan. I ended up reviewing it for BookBrowse. My full review is here and I also wrote a short related article on Keegan’s career and the unusual publishing history of this particular novella. Here are short excerpts from both:

Claire Keegan’s delicate, heart-rending novella tells the story of a deprived young Irish girl sent to live with rural relatives for one pivotal summer. Although Foster feels like a timeless fable, a brief mention of IRA hunger strikers dates it to 1981. It bears all the hallmarks of a book several times its length: a convincing and original voice, rich character development, an evocative setting, just enough backstory, psychological depth, conflict and sensitive treatment of difficult themes like poverty and neglect. I finished the one-sitting read in a flood of tears, hoping the Kinsellas’ care might be enough to protect the girl from the harshness she may face in the rest of her growing-up years. Keegan unfolds a cautionary tale of endangered childhood, also hinting at the enduring difference a little compassion can make. [128 pages] ![]()

Foster is now in print for the first time in the USA (from Grove Atlantic), having had an unusual path to publication. It first appeared in the New Yorker in 2010, but in abridged form. Keegan told the Guardian she felt the condensed version “was very well done but wasn’t the whole story. It had some of the layers taken out, but I think the heart was the same.” She herself has described Foster as a long short story; “It is definitely not a novella. It doesn’t have the pace of a novella.” Faber & Faber first published it as a standalone volume in the UK in 2010. A 2022 Irish-language film version of Foster, called The Quiet Girl (which names the main character Cait) became a favorite on the international film festival circuit.

Foster is now in print for the first time in the USA (from Grove Atlantic), having had an unusual path to publication. It first appeared in the New Yorker in 2010, but in abridged form. Keegan told the Guardian she felt the condensed version “was very well done but wasn’t the whole story. It had some of the layers taken out, but I think the heart was the same.” She herself has described Foster as a long short story; “It is definitely not a novella. It doesn’t have the pace of a novella.” Faber & Faber first published it as a standalone volume in the UK in 2010. A 2022 Irish-language film version of Foster, called The Quiet Girl (which names the main character Cait) became a favorite on the international film festival circuit.

[Edited on December 1st]

A number of you joined us in reading Foster this month:

Lynne at Fictionophile

Karen at The Simply Blog

Davida at The Chocolate Lady’s Book Reviews

Tony at Tony’s Book World

Brona at This Reading Life

Janet at Love Books Read Books

Jane at Just Reading a Book

Kate at Books Are My Favourite and Best

Carol at Reading Ladies

(Cathy also reviewed it last year.)

Our bloggers have been impressed with the spare, precise writing style and the emotional heft of this little tale. Their only complaint? The slight ambiguity of the ending. Read it yourself to find out what you think! If you’d still like to take part in the buddy read and have an hour or two free, remember you can access the original version of the story here.

Acts of Desperation by Megan Nolan

I read this after its shortlisting for the Charlotte Aitken Trust/Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award, as well as its longlisting for the Dylan Thomas Prize. It is a truth universally acknowledged that any novel by a young Irish woman will only and ever be compared to Sally Rooney … but that works in Nolan’s favour. I would certainly call this a readalike to Rooney’s first two books, but there’s an added psychological intensity here.

A young woman reflects on an obsessive affair that she began in Dublin in April 2012. Was it love at first sight for her with Ciaran? No, actually, it was more like pity: “The first time I saw him, I pitied him terribly,” the novel opens. “I stood in that gallery and felt not only sexual attraction (which I was aware of, dimly, as background noise) but what I can only describe as grave and troubling pity.” That doesn’t bode well now, does it?

A young woman reflects on an obsessive affair that she began in Dublin in April 2012. Was it love at first sight for her with Ciaran? No, actually, it was more like pity: “The first time I saw him, I pitied him terribly,” the novel opens. “I stood in that gallery and felt not only sexual attraction (which I was aware of, dimly, as background noise) but what I can only describe as grave and troubling pity.” That doesn’t bode well now, does it?

Ciaran is an insecure, hot-tempered magazine writer. He’s also still half in love with his ex-girlfriend, Freja, whom he left behind in Copenhagen, and our narrator (an underemployed would-be writer) feels she has to fight for his attention and affections. She has body issues and drinks too much, but she’s addicted to love, and sex specifically, as much as to alcohol.

A central on-again, off-again relationship is hardly a new subject for fiction, but I admired Nolan’s work for its sharp insights into the psyche of an emotionally fragile young woman whose frantic search for someone to value her leads her into masochistic behaviours. Brief looks back at the events of 2012–14 from a present storyline set in Athens in 2019 create helpful hindsight yet reveal how much she still struggles to affirm her self-worth.

The short chapters are like freeze-frames, concentrated bursts of passion that will resonate even if the characters’ specific situations do not. And it’s not all despair and damage; there are beautiful moments here, too, like the sweet habit they had of buying an apple each and then just walking around town for a cheap outing – the source of the cover image. I marked passage after passage, but will share just a couple:

How impoverished my internal life had become, the scrabbling for a token of love from somebody who didn’t want to offer it.

I was taking away his ability to live without me easily. I subbed his rent, I cooked his food, I cleaned his clothes, so that one day soon there would come a time when he could no longer remember how he had ever done without me, and could not imagine doing so ever again.

Even if you’re burnt out on what pace amore libri blogger Rachel dubs “disaster woman” books, make an exception for this potent story of self-sabotage and -recovery. Especially if you’re a fan of Emma Jane Unsworth, The Inland Sea by Madeleine Watts, and, yes, Sally Rooney. (Also reviewed by Annabel.)

My rating: ![]()

With thanks to FMcM Associates and Jonathan Cape for the free copy for review.

The rest of the shortlist:

After about 50 pages I DNFed Here Comes the Miracle by Anna Beecher, which had MA-course writing-by-numbers and seemed to be building towards When God Was a Rabbit mawkishness (how on earth did it get shortlisted?!).

See my mini reviews of the other three nominees here.

I am still rooting for Cal Flyn to win for her excellent and perennially relevant travel book, Islands of Abandonment.

Tonight there’s a shortlist readings event taking place in London. If anyone goes, do share photos! The award will be given tomorrow, the 24th. I’ll look out for the announcement.

Chase of the Wild Goose, a playful, offbeat biographical novel about the Ladies of Llangollen, was first published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press in 1936. I was delighted to be invited to take part in an informal blog tour celebrating the book’s return to print (today, 1 February) as the inaugural publication of

Chase of the Wild Goose, a playful, offbeat biographical novel about the Ladies of Llangollen, was first published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press in 1936. I was delighted to be invited to take part in an informal blog tour celebrating the book’s return to print (today, 1 February) as the inaugural publication of

I knew Bergman from her second of three collections,

I knew Bergman from her second of three collections,  What a clever decision to open with “Lucky Chow Fun,” a story set in Templeton, the location of Groff’s

What a clever decision to open with “Lucky Chow Fun,” a story set in Templeton, the location of Groff’s  I’d read a few of Moore’s works before (A Gate at the Stairs, Bark, Who Will Run the Frog Hospital?) and not grasped what the fuss is about; turns out I’d just chosen the wrong ones to read. This collection is every bit as good as everyone has been saying for the last 25 years. Amy Bloom, Carol Shields and Helen Simpson are a few other authors who struck me as having a similar tone and themes. Rich with psychological understanding of her characters – many of them women passing from youth to midlife, contemplating or being affected by adultery – and their relationships, the stories are sometimes wry and sometimes wrenching (that setup to “Terrific Mother”!). There were even two dysfunctional-family-at-the-holidays ones (“Charades” and “Four Calling Birds, Three French Hens”) for me to read in December.

I’d read a few of Moore’s works before (A Gate at the Stairs, Bark, Who Will Run the Frog Hospital?) and not grasped what the fuss is about; turns out I’d just chosen the wrong ones to read. This collection is every bit as good as everyone has been saying for the last 25 years. Amy Bloom, Carol Shields and Helen Simpson are a few other authors who struck me as having a similar tone and themes. Rich with psychological understanding of her characters – many of them women passing from youth to midlife, contemplating or being affected by adultery – and their relationships, the stories are sometimes wry and sometimes wrenching (that setup to “Terrific Mother”!). There were even two dysfunctional-family-at-the-holidays ones (“Charades” and “Four Calling Birds, Three French Hens”) for me to read in December.

#1 Flaubert’s Parrot by Julian Barnes was one of my most-admired novels in my twenties, though I didn’t like it quite as much

#1 Flaubert’s Parrot by Julian Barnes was one of my most-admired novels in my twenties, though I didn’t like it quite as much  #2 My latest reread was Falling Angels by Tracy Chevalier, for book club. I’ve read all of her novels and always thought of this one as my favourite. A reread didn’t change that, so I rated it 5 stars. I love the neat structure that bookends the action between the death of Queen Victoria and the death of Edward VII, and the focus on funerary customs (with Highgate Cemetery a major setting) and women’s rights is right up my street.

#2 My latest reread was Falling Angels by Tracy Chevalier, for book club. I’ve read all of her novels and always thought of this one as my favourite. A reread didn’t change that, so I rated it 5 stars. I love the neat structure that bookends the action between the death of Queen Victoria and the death of Edward VII, and the focus on funerary customs (with Highgate Cemetery a major setting) and women’s rights is right up my street. #3 Another novel featuring an angel that I read for a book club was The Vintner’s Luck by Elizabeth Knox. It’s set in Burgundy, France in 1808, when an angel rescues a drunken winemaker from a fall. All I can remember is that it was bizarre and pretty terrible, so I’m glad I didn’t realize it was the same author and went ahead with a read of

#3 Another novel featuring an angel that I read for a book club was The Vintner’s Luck by Elizabeth Knox. It’s set in Burgundy, France in 1808, when an angel rescues a drunken winemaker from a fall. All I can remember is that it was bizarre and pretty terrible, so I’m glad I didn’t realize it was the same author and went ahead with a read of  #4 The winemaking theme takes me to my next selection, Cork Dork by Bianca Bosker, which I read on a trip to the Netherlands and Belgium in 2017. Bosker, previously a technology journalist, gave herself a year and a half to learn everything she could about wine in hopes of passing the Court of Master Sommeliers exam. The result is such a fun blend of science, memoir and encounters with people who are deadly serious about wine.

#4 The winemaking theme takes me to my next selection, Cork Dork by Bianca Bosker, which I read on a trip to the Netherlands and Belgium in 2017. Bosker, previously a technology journalist, gave herself a year and a half to learn everything she could about wine in hopes of passing the Court of Master Sommeliers exam. The result is such a fun blend of science, memoir and encounters with people who are deadly serious about wine. #5 I have so often heard the title The Dork of Cork by Chet Raymo, though I don’t know why because I can’t think of an acquaintance who’s actually read or reviewed it. The synopsis: “When Frank, an Irish dwarf, writes a personal memoir, he moves from dark isolation into the public eye. This luminous journey is marked by memories of his lonely childhood, secrets of his doomed young mother, and his passion for a woman who is as unreachable as the stars.” Sounds a bit like A Prayer for Owen Meany.

#5 I have so often heard the title The Dork of Cork by Chet Raymo, though I don’t know why because I can’t think of an acquaintance who’s actually read or reviewed it. The synopsis: “When Frank, an Irish dwarf, writes a personal memoir, he moves from dark isolation into the public eye. This luminous journey is marked by memories of his lonely childhood, secrets of his doomed young mother, and his passion for a woman who is as unreachable as the stars.” Sounds a bit like A Prayer for Owen Meany. #6 Another novel with a dwarf: Geek Love by Katherine Dunn, about a carnival of freaks that tours U.S. backwaters. I have meant to read this for many years and was even convinced that I owned a copy, but on my last few trips to the States I’ve not been able to find it in one of the boxes in my sister’s basement. Hmmm.

#6 Another novel with a dwarf: Geek Love by Katherine Dunn, about a carnival of freaks that tours U.S. backwaters. I have meant to read this for many years and was even convinced that I owned a copy, but on my last few trips to the States I’ve not been able to find it in one of the boxes in my sister’s basement. Hmmm. The 11 stories in Erskine’s second collection do just what short fiction needs to: dramatize an encounter, or moment, that changes life forever. Her characters are ordinary, moving through the dead-end work and family friction that constitute daily existence, until something happens, or rises up in the memory, that disrupts the tedium.

The 11 stories in Erskine’s second collection do just what short fiction needs to: dramatize an encounter, or moment, that changes life forever. Her characters are ordinary, moving through the dead-end work and family friction that constitute daily existence, until something happens, or rises up in the memory, that disrupts the tedium. In form this is similar to O’Farrell’s

In form this is similar to O’Farrell’s  These autobiographical essays were compiled by Quinn based on interviews he conducted with nine women writers for an RTE Radio series in 1985. I’d read bits of Dervla Murphy’s and Edna O’Brien’s work before, but the other authors were new to me (Maeve Binchy, Clare Boylan, Polly Devlin, Jennifer Johnston, Molly Keane, Mary Lavin and Joan Lingard). The focus is on childhood: what their family was like, what drove these women to write, and what fragments of real life have made it into their books.

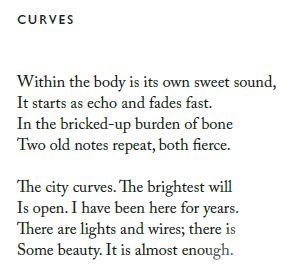

These autobiographical essays were compiled by Quinn based on interviews he conducted with nine women writers for an RTE Radio series in 1985. I’d read bits of Dervla Murphy’s and Edna O’Brien’s work before, but the other authors were new to me (Maeve Binchy, Clare Boylan, Polly Devlin, Jennifer Johnston, Molly Keane, Mary Lavin and Joan Lingard). The focus is on childhood: what their family was like, what drove these women to write, and what fragments of real life have made it into their books. I didn’t realize when I started it that this was Tóibín’s debut collection; so confident is his verse that I assumed he’s been publishing poetry for decades. He’s one of those polymaths who’s written in many genres – contemporary fiction, literary criticism, travel memoir, historical fiction – and impresses in all. I’ve been finding his recent Folio Prize winner, The Magician, a little too dry and biography-by-rote for someone with no particular interest in Thomas Mann (I’ve only ever read Death in Venice), so I will likely just skim it before returning it to the library, but I can highly recommend his poems as an alternative.

I didn’t realize when I started it that this was Tóibín’s debut collection; so confident is his verse that I assumed he’s been publishing poetry for decades. He’s one of those polymaths who’s written in many genres – contemporary fiction, literary criticism, travel memoir, historical fiction – and impresses in all. I’ve been finding his recent Folio Prize winner, The Magician, a little too dry and biography-by-rote for someone with no particular interest in Thomas Mann (I’ve only ever read Death in Venice), so I will likely just skim it before returning it to the library, but I can highly recommend his poems as an alternative.

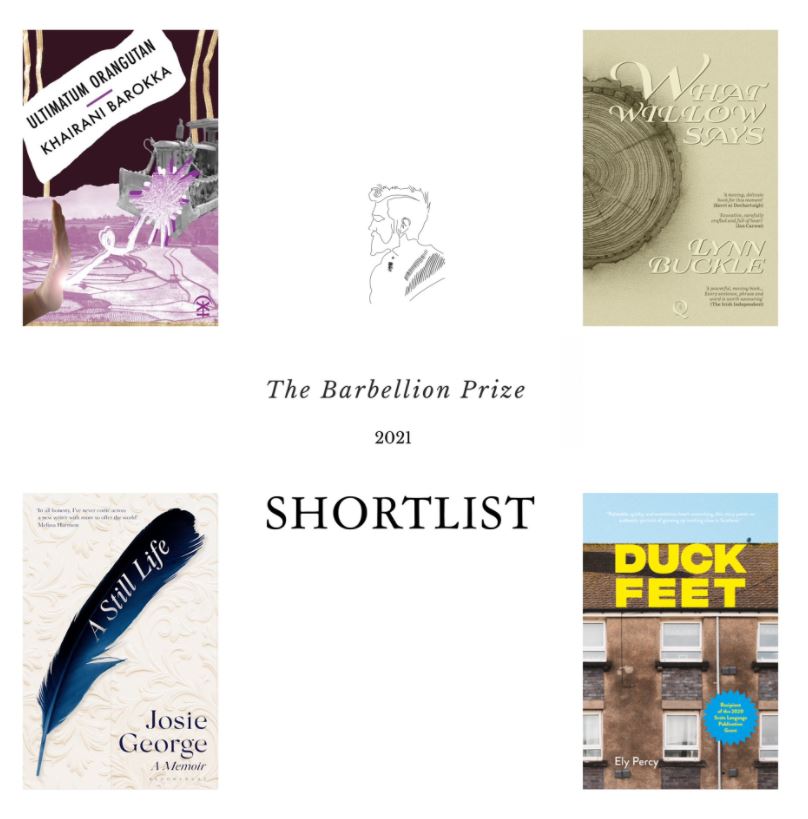

Barokka is an Indonesian poet and performance artist based in London. The topics of her second collection include chronic pain, the oppression of women, and the environmental crisis. While she’s distressed at the exploitation of nature, she sprinkles in humanist reminders of Indigenous peoples whose needs should also be valued. For instance, in the title poem, whose points of reference range from King Kong to palm oil plantations, she acknowledges that orangutans must be saved, but that people are also suffering in her native Indonesia. It’s a subtle plea for balanced consideration.

Barokka is an Indonesian poet and performance artist based in London. The topics of her second collection include chronic pain, the oppression of women, and the environmental crisis. While she’s distressed at the exploitation of nature, she sprinkles in humanist reminders of Indigenous peoples whose needs should also be valued. For instance, in the title poem, whose points of reference range from King Kong to palm oil plantations, she acknowledges that orangutans must be saved, but that people are also suffering in her native Indonesia. It’s a subtle plea for balanced consideration.

This is a delicate novella about the bond between a grandmother and her eight-year-old granddaughter, who is deaf. After the death of the girl’s mother, Grandmother has been her primary guardian. She raises her on Irish legends and a love of nature, especially their local trees. They mourn when they see hedgerows needlessly flailed, and the girl often asks what her grandmother hears the trees saying. Because Grandmother narrates in the form of journal entries, there is dramatic irony between what readers learn and what she is not telling the little girl; we ache to think about what might happen for her in the future.

This is a delicate novella about the bond between a grandmother and her eight-year-old granddaughter, who is deaf. After the death of the girl’s mother, Grandmother has been her primary guardian. She raises her on Irish legends and a love of nature, especially their local trees. They mourn when they see hedgerows needlessly flailed, and the girl often asks what her grandmother hears the trees saying. Because Grandmother narrates in the form of journal entries, there is dramatic irony between what readers learn and what she is not telling the little girl; we ache to think about what might happen for her in the future.

My favourite of the series so far (just Spring still to go) for how nostalgic it is for winter traditions.

My favourite of the series so far (just Spring still to go) for how nostalgic it is for winter traditions. After enjoying

After enjoying  I smugly started this on the first day of Advent, and initially enjoyed Mackay’s macabre habit of taking elements of the Nativity scene or a traditional Christmas and giving them a seedy North London twist. So we open on a butcher’s shop and a young man wearing “bloody swabbing cloths” rather than swaddling clothes, having lost a finger to the meat mincer (and later we see “a misty Christmas postman with his billowy sack come out of the abattoir’s gates”). In this way, John Wood becomes an unwitting cannibal after taking a parcel home from the butcher’s that day, and can’t forget about it as he moves his temporarily homeless family into his old uncle’s house and continues halfheartedly in his job as a cleaner. His wife has an affair; so does a teenage girl at the school where his sister works. No one is happy and everything is sordid. “Scouring powder snowed” and the animal at this perverse manger scene is the uncle’s neglected goat. This novella is soon read, but soon forgotten. (Secondhand purchase)

I smugly started this on the first day of Advent, and initially enjoyed Mackay’s macabre habit of taking elements of the Nativity scene or a traditional Christmas and giving them a seedy North London twist. So we open on a butcher’s shop and a young man wearing “bloody swabbing cloths” rather than swaddling clothes, having lost a finger to the meat mincer (and later we see “a misty Christmas postman with his billowy sack come out of the abattoir’s gates”). In this way, John Wood becomes an unwitting cannibal after taking a parcel home from the butcher’s that day, and can’t forget about it as he moves his temporarily homeless family into his old uncle’s house and continues halfheartedly in his job as a cleaner. His wife has an affair; so does a teenage girl at the school where his sister works. No one is happy and everything is sordid. “Scouring powder snowed” and the animal at this perverse manger scene is the uncle’s neglected goat. This novella is soon read, but soon forgotten. (Secondhand purchase)  An evocative portrait of an English Christmas meal, hosted by a squire in the great hall of his manor, originally published in Irving’s The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. A boar’s head, a mummers’ play, the Lord of Misrule: you couldn’t get much more traditional. “Master Simon covered himself with glory by the stateliness with which, as Ancient Christmas, he walked a minuet with the peerless, though giggling, Dame Mince Pie.” Irving’s narrator knows this little tale isn’t profound or intellectually satisfying, but hopes it will raise a smile. He also has a sense that he is recording something that might soon pass away:

An evocative portrait of an English Christmas meal, hosted by a squire in the great hall of his manor, originally published in Irving’s The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. A boar’s head, a mummers’ play, the Lord of Misrule: you couldn’t get much more traditional. “Master Simon covered himself with glory by the stateliness with which, as Ancient Christmas, he walked a minuet with the peerless, though giggling, Dame Mince Pie.” Irving’s narrator knows this little tale isn’t profound or intellectually satisfying, but hopes it will raise a smile. He also has a sense that he is recording something that might soon pass away: This was our second most popular read during last month’s Novellas in November challenge. I’d read a lot about it in fellow bloggers’ posts and newspaper reviews so knew to expect a meticulously chiselled and heartwarming story about a coal merchant in 1980s Ireland who comes to value his quiet family life all the more when he sees how difficult existence is for the teen mothers sent to work in the local convent’s laundry service. Born out of wedlock himself nearly 40 years ago, he is grateful that his mother received kindness and wishes he could do more to help the desperate girls he meets when he makes deliveries to the convent.

This was our second most popular read during last month’s Novellas in November challenge. I’d read a lot about it in fellow bloggers’ posts and newspaper reviews so knew to expect a meticulously chiselled and heartwarming story about a coal merchant in 1980s Ireland who comes to value his quiet family life all the more when he sees how difficult existence is for the teen mothers sent to work in the local convent’s laundry service. Born out of wedlock himself nearly 40 years ago, he is grateful that his mother received kindness and wishes he could do more to help the desperate girls he meets when he makes deliveries to the convent. Lafaye was a local-ish author to me, an American expat living in Marlborough. When she died of breast cancer in 2018, she left this A Christmas Carol prequel unfinished, and fellow historical novelist Rebecca Mascull completed it for her. Clara and Jacob Marley come from money but end up on the streets, stealing from the rich to get by. Jacob sets himself up as a moneylender to the poor and then, after serving an apprenticeship alongside Ebenezer Scrooge, goes into business with him. They are a bad influence on each other, reinforcing each other’s greed and hard hearts. Jacob is determined never to be poor again. Because he’s forgotten what it’s like, he has no compassion when Clara falls in love with a luckless Scottish tea merchant. Like Scrooge, Jacob is offered one final chance to mend his ways. This was easy and pleasant reading, but I did wonder if there was a point to reading this when one could just reread Dickens’s original. (Secondhand purchase)

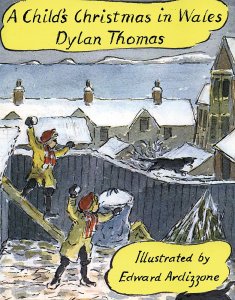

Lafaye was a local-ish author to me, an American expat living in Marlborough. When she died of breast cancer in 2018, she left this A Christmas Carol prequel unfinished, and fellow historical novelist Rebecca Mascull completed it for her. Clara and Jacob Marley come from money but end up on the streets, stealing from the rich to get by. Jacob sets himself up as a moneylender to the poor and then, after serving an apprenticeship alongside Ebenezer Scrooge, goes into business with him. They are a bad influence on each other, reinforcing each other’s greed and hard hearts. Jacob is determined never to be poor again. Because he’s forgotten what it’s like, he has no compassion when Clara falls in love with a luckless Scottish tea merchant. Like Scrooge, Jacob is offered one final chance to mend his ways. This was easy and pleasant reading, but I did wonder if there was a point to reading this when one could just reread Dickens’s original. (Secondhand purchase)  It’s a wonder I’d never managed to read this short story before. I was prepared for something slightly twee; instead, it is sprightly and imaginative, full of unexpected images and wordplay. In the Wales of his childhood, there were wolves and bears and hippos. Young boys could get up to all sorts of mischief, but knew that a warm house packed with relatives and a cosy bed awaited at the end of a momentous day. Reflective and magical in equal measure; a lovely wee volume that I am sure to reread year after year. (Little Free Library)

It’s a wonder I’d never managed to read this short story before. I was prepared for something slightly twee; instead, it is sprightly and imaginative, full of unexpected images and wordplay. In the Wales of his childhood, there were wolves and bears and hippos. Young boys could get up to all sorts of mischief, but knew that a warm house packed with relatives and a cosy bed awaited at the end of a momentous day. Reflective and magical in equal measure; a lovely wee volume that I am sure to reread year after year. (Little Free Library)