#ReadIndies Nonfiction Catch-Up: Ansell, Farrier, Febos, Hoffman, Orlean and Stacey

These are all 2025 releases; for some, it’s approaching a year since I was sent a review copy or read the book. Silly me. At last, I’ve caught up. Reading Indies month, hosted by Kaggsy in memory of her late co-host Lizzy Siddal, is the perfect time to feature books from five independent publishers. I have four works that might broadly be classed as nature writing – though their topics range from birdsong and technology to living in Greece and rewilding a plot in northern Spain – and explorations of celibacy and the writer’s profession.

The Edge of Silence: In Search of the Disappearing Sounds of Nature by Neil Ansell

Ansell draws parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis. He puts together a wish list of species – mostly seabirds (divers, grebes), but also inland birds (nightjars) and a couple of non-avian representatives (otters) – that he wants to hear and sets off on public transport adventures to find them. “I must find beauty where I can, and while I still can,” he vows. From his home on the western coast of Scotland near the Highlands, this involves trains or buses that never align with the ferry timetables. Furthest afield for him are two nature reserves in northern England where his mission is to hear bitterns “booming” and natterjack toads croaking at night. There are also mountain excursions to locate ptarmigan, greenshank, and black grouse. His island quarry includes Manx shearwaters (Rum), corncrakes (Coll), puffins (Sanday), and storm petrels (Shetland).

Ansell draws parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis. He puts together a wish list of species – mostly seabirds (divers, grebes), but also inland birds (nightjars) and a couple of non-avian representatives (otters) – that he wants to hear and sets off on public transport adventures to find them. “I must find beauty where I can, and while I still can,” he vows. From his home on the western coast of Scotland near the Highlands, this involves trains or buses that never align with the ferry timetables. Furthest afield for him are two nature reserves in northern England where his mission is to hear bitterns “booming” and natterjack toads croaking at night. There are also mountain excursions to locate ptarmigan, greenshank, and black grouse. His island quarry includes Manx shearwaters (Rum), corncrakes (Coll), puffins (Sanday), and storm petrels (Shetland).

Camping in a tent means cold nights, interrupted sleep, and clouds of midges, but it’s all worth it to have unrepeatable wildlife experiences. He has a very high hit rate for (seeing and) hearing what he intends to, even when they’re just on the verge of what he can decipher with his hearing aids. On the rare occasions when he misses out, he consoles himself with earlier encounters. “I shall settle for the memory, for it feels unimprovable, like a spell that I do not want to break.” I’ve read all of Ansell’s nature memoirs and consider him one of the UK’s top writers on the natural world. His accounts of his low-carbon travels are entertaining, and the tug-of-war between resisting and coming to terms with his disability is heartening. “I have spent this year in defiance of a relentless, unstoppable countdown,” he reflects. What makes this book more universal than niche is the deadline: we and all of these creatures face extinction. Whether it’s sooner or later depends on how we act to address the environmental polycrisis.

With thanks to Birlinn for the free copy for review.

Nature’s Genius: Evolution’s Lessons for a Changing Planet by David Farrier

Farrier’s Footprints, which tells the story of the human impact on the Earth, was one of my favourite books of 2020. This contains a similar blend of history, science, and literary points of reference (Farrier is a professor of literature and the environment at the University of Edinburgh), with past changes offering a template for how the future might look different. “We are forcing nature to reimagine itself, and to avert calamity we need to do the same,” he writes. Cliff swallows have evolved blunter wings to better evade cars; captive breeding led foxes to develop the domesticated traits of pet dogs.

Farrier’s Footprints, which tells the story of the human impact on the Earth, was one of my favourite books of 2020. This contains a similar blend of history, science, and literary points of reference (Farrier is a professor of literature and the environment at the University of Edinburgh), with past changes offering a template for how the future might look different. “We are forcing nature to reimagine itself, and to avert calamity we need to do the same,” he writes. Cliff swallows have evolved blunter wings to better evade cars; captive breeding led foxes to develop the domesticated traits of pet dogs.

It’s not just other species that experience current evolution. Thanks to food abundance and a sedentary lifestyle, humans show a “consumer phenotype,” which superseded the Palaeolithic (95% of human history) and tends toward earlier puberty, autoimmune diseases, and obesity. Farrier also looks at notions of intelligence, language, and time in nature. Sustainable cities will have to cleverly reuse materials. For instance, The Waste House in Brighton is 90% rubbish. (This I have to see!)

There are many interesting nuggets here, and statements that are difficult to argue with, but I struggled to find an overall thread. Cool to see my husband’s old housemate mentioned, though. (Duncan Geere, for collaborating on a hybrid science–art project turning climate data into techno music.)

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

The Dry Season: Finding Pleasure in a Year without Sex by Melissa Febos

Febos considers but rejects the term “sex addiction” for the years in which she had compulsive casual sex (with “the Last Man,” yes, but mostly with women). Since her early teen years, she’d never not been tied to someone. Brief liaisons alternated with long-term relationships: three years with “the Best Ex”; two years that were so emotionally tumultuous that she refers to the woman as “the Maelstrom.” It was the implosion of the latter affair that led to Febos deciding to experiment with celibacy, first for three months, then for a whole year. “I felt feral and sad and couldn’t explain it, but I knew that something had to change.”

The quest involved some research into celibate movements in history, but was largely an internal investigation of her past and psyche. Febos found that she was less attuned to the male gaze. Having worn high heels almost daily for 20 years, she discovered she’s more of a trainers person. Although she was still tempted to flirt with attractive women, e.g. on an airplane, she consciously resisted the impulse to spin random meetings into one-night stands. (A therapist had stopped her short with the blunt observation, “you use people.”) With a new focus on the life of the mind, she insists, “My life was empty of lovers and more full than it had ever been.” (This reminded me of Audre Lorde’s writing on the erotic.) As Silvana Panciera, an Italian scholar on the beguines (a secular nun-like sisterhood), told her: “When you don’t belong to anyone, you belong to everyone. You feel able to love without limits.”

The quest involved some research into celibate movements in history, but was largely an internal investigation of her past and psyche. Febos found that she was less attuned to the male gaze. Having worn high heels almost daily for 20 years, she discovered she’s more of a trainers person. Although she was still tempted to flirt with attractive women, e.g. on an airplane, she consciously resisted the impulse to spin random meetings into one-night stands. (A therapist had stopped her short with the blunt observation, “you use people.”) With a new focus on the life of the mind, she insists, “My life was empty of lovers and more full than it had ever been.” (This reminded me of Audre Lorde’s writing on the erotic.) As Silvana Panciera, an Italian scholar on the beguines (a secular nun-like sisterhood), told her: “When you don’t belong to anyone, you belong to everyone. You feel able to love without limits.”

Intriguing that this is all a retrospective, reflecting on her thirties; Febos is now in her mid-forties and married to a woman (poet Donika Kelly). Clearly she felt that it was an important enough year – with landmark epiphanies that changed her and have the potential to help others – to form the basis for a book. For me, she didn’t have much new to offer about celibacy, though it was interesting to read about the topic from an areligious perspective. But I admire the depth of her self-knowledge, and particularly her ability to recreate her mindset at different times. This is another one, like her Girlhood, to keep on the shelf as a model.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

Lifelines: Searching for Home in the Mountains of Greece by Julian Hoffman

Hoffman’s Irreplaceable was my nonfiction book of 2019. Whereas that was a work with a global environmentalist perspective, Lifelines is more personal in scope. It tracks the author’s unexpected route from Canada via the UK to Prespa, a remote area of northern Greece that’s at the crossroads with Albania and North Macedonia. He and his wife, Julia, encountered Prespa in a book and, longing for respite from the breakneck pace of life in London, moved there in 2000. “Like the rivers that spill into these shared lakes, lifelines rarely flow straight. Instead, they contain bends, meanders and loops; they hold, at times, turns of extraordinary surprise.” Birdwatching, which Hoffman suggests is as “a way of cultivating attention,” had been their gateway into a love for nature developed over the next quarter-century and more, and in Greece they delighted in seeing great white and Dalmatian pelicans (which feature on the splendid U.S. cover. It would be lovely to have an illustrated edition of this.)

Hoffman’s Irreplaceable was my nonfiction book of 2019. Whereas that was a work with a global environmentalist perspective, Lifelines is more personal in scope. It tracks the author’s unexpected route from Canada via the UK to Prespa, a remote area of northern Greece that’s at the crossroads with Albania and North Macedonia. He and his wife, Julia, encountered Prespa in a book and, longing for respite from the breakneck pace of life in London, moved there in 2000. “Like the rivers that spill into these shared lakes, lifelines rarely flow straight. Instead, they contain bends, meanders and loops; they hold, at times, turns of extraordinary surprise.” Birdwatching, which Hoffman suggests is as “a way of cultivating attention,” had been their gateway into a love for nature developed over the next quarter-century and more, and in Greece they delighted in seeing great white and Dalmatian pelicans (which feature on the splendid U.S. cover. It would be lovely to have an illustrated edition of this.)

One strand of this warm and fluent memoir is about making a home in Greece: buying and renovating a semi-derelict property, experiencing xenophobia and hospitality from different quarters, and finding a sense of belonging. They’re happy to share their home with nesting wrens, who recur across the book and connect to the tagline of “a story of shelter shared.” In probing the history of his adopted country, Hoffman comes to realise the false, arbitrary nature of borders – wildlife such as brown bears and wolves pay these no heed. Everything is connected and questions of justice are always intersectional. The Covid pandemic and avian influenza (which devastated the region’s pelicans) are setbacks that Hoffman addresses honestly. But the lingering message is a valuable one of bridging divisions and learning how to live in harmony with other people – and with other species.

One strand of this warm and fluent memoir is about making a home in Greece: buying and renovating a semi-derelict property, experiencing xenophobia and hospitality from different quarters, and finding a sense of belonging. They’re happy to share their home with nesting wrens, who recur across the book and connect to the tagline of “a story of shelter shared.” In probing the history of his adopted country, Hoffman comes to realise the false, arbitrary nature of borders – wildlife such as brown bears and wolves pay these no heed. Everything is connected and questions of justice are always intersectional. The Covid pandemic and avian influenza (which devastated the region’s pelicans) are setbacks that Hoffman addresses honestly. But the lingering message is a valuable one of bridging divisions and learning how to live in harmony with other people – and with other species.

With thanks to Elliott & Thompson for the free copy for review.

Joyride by Susan Orlean

As a long-time staff writer for The New Yorker, Orlean has had the good fortune to be able to follow her curiosity wherever it leads, chasing the subjects that interest her and drawing readers in with her infectious enthusiasm. She grew up in suburban Ohio, attended college in Michigan, and lived in Portland, Oregon and Boston before moving to New York City. Her trajectory was from local and alternative papers to the most enviable of national magazines: Esquire, Rolling Stone and Vogue. Orlean gives behind-the-scenes information on lots of her early stories, some of which are reprinted in an appendix. “If you’re truly open, it’s easy to fall in love with your subject,” she writes; maintaining objectivity could be difficult, as when she profiled an Indian spiritual leader with a cult following; and fended off an interviewee’s attachment when she went on the road with a Black gospel choir.

Her personal life takes a backseat to her career, though she is frank about the breakdown of her first marriage, her second chance at love and late motherhood, and a surprise bout with lung cancer. The chronological approach proceeds book by book, delving into her inspirations, research process and publication journeys. Her first book was about Saturday night as experienced across America. It was a more innocent time, when subjects were more trusting. Orlean and her second husband had farms in the Hudson Valley of New York and in greater Los Angeles, and she ended up writing a lot about animals, with books on Rin Tin Tin and one collecting her animal pieces. There was also, of course, The Library Book, about the wild history of the main Los Angeles public library. But it’s her The Orchid Thief – and the movie (not) based on it, Adaptation – that’s among my favourites, so the long section on that was the biggest thrill for me. There are also black-and-white images scattered through.

Her personal life takes a backseat to her career, though she is frank about the breakdown of her first marriage, her second chance at love and late motherhood, and a surprise bout with lung cancer. The chronological approach proceeds book by book, delving into her inspirations, research process and publication journeys. Her first book was about Saturday night as experienced across America. It was a more innocent time, when subjects were more trusting. Orlean and her second husband had farms in the Hudson Valley of New York and in greater Los Angeles, and she ended up writing a lot about animals, with books on Rin Tin Tin and one collecting her animal pieces. There was also, of course, The Library Book, about the wild history of the main Los Angeles public library. But it’s her The Orchid Thief – and the movie (not) based on it, Adaptation – that’s among my favourites, so the long section on that was the biggest thrill for me. There are also black-and-white images scattered through.

It was slightly unfortunate that I read this at the same time as Book of Lives – who could compete with Margaret Atwood? – but it is, yes, a joy to read about Orlean’s writing life. She’s full of enthusiasm and good sense, depicting the vocation as part toil and part magic:

“I find superhuman self-confidence when I’m working on a story. The bashfulness and vulnerability that I might otherwise experience in a new setting melt away, and my desire to connect, to observe, to understand, powers me through.”

“I like to do a gut check any time I dismiss or deplore something I don’t know anything about. That feels like reason enough to learn about it.”

“anything at all is worth writing about if you care about it and it makes you curious and makes you want to holler about it to other people”

With thanks to Atlantic Books for the free copy for review.

No Paradise with Wolves: A Journey of Rewilding and Resilience by Katie Stacey

I had the good fortune to visit Wild Finca, Luke Massey and Katie Stacey’s rewilding site in Asturias, while on holiday in northern Spain in May 2022, and was intrigued to learn more about their strategy and experiences. This detailed account of the first four years begins with their search for a property in 2018 and traces the steps of their “agriwilding” of a derelict farm: creating a vegetable garden and tending to fruit trees, but also digging ponds, training up hedgerows, and setting up rotational grazing. Their every decision went against the grain. Others focussed on one crop or type of livestock while they encouraged unruly variety, keeping chickens, ducks, goats, horses and sheep. Their neighbours removed brush in the name of tidiness; they left the bramble and gorse to welcome in migrant birds. New species turned up all the time, from butterflies and newts to owls and a golden fox.

Luke is a wildlife guide and photographer. He and Katie are conservation storytellers, trying to get people to think differently about land management. The title is a Spanish farmers’ and hunters’ slogan about the Iberian wolf. Fear of wolves runs deep in the region. Initially, filming wolves was one of the couple’s major goals, but they had to step back because staking out the animals’ haunts felt risky; better to let them alone and not attract the wrong attention. (Wolf hunting was banned across Spain in 2021.) There’s a parallel to be found here between seeing wolves as a threat and the mild xenophobia the couple experienced. Other challenges included incompetent house-sitters, off-lead dogs killing livestock, the pandemic, wildfires, and hunters passing through weekly (as in France – as we discovered at Le Moulin de Pensol in 2024 – hunters have the right to traverse private land in Spain).

Luke and Katie hope to model new ways of living harmoniously with nature – even bears and wolves, which haven’t made it to their land yet, but might in the future – for the region’s traditional farmers. They’re approaching self-sufficiency – for fruit and vegetables, anyway – and raising their sons, Roan and Albus, to love the wild. We had a great day at Wild Finca: a long tour and badger-watching vigil (no luck that time) led by Luke; nettle lemonade and sponge cake with strawberries served by Katie and the boys. I was clear how much hard work has gone into the land and the low-impact buildings on it. With the exception of some Workaway volunteers, they’ve done it all themselves.

Katie Stacey’s storytelling is effortless and conversational, making this impassioned memoir a pleasure to read. It chimed perfectly with Hoffman’s writing (above) about the fear of bears and wolves, and reparation policies for farmers, in Europe. I’d love to see the book get a bigger-budget release complete with illustrations, a less misleading title, the thorough line editing it deserves, and more developmental work to enhance the literary technique – as in the beautiful final chapter, a present-tense recreation of a typical walk along The Loop. All this would help to get the message the wider reach that authors like Isabella Tree have found. “I want to be remembered for the wild spaces I leave behind,” Katie writes in the book’s final pages. “I want to be remembered as someone who inspired people to seek a deeper connection to nature.” You can’t help but be impressed by how much of a difference two people seeking to live differently have achieved in just a handful of years. We can all rewild the spaces available to us (see also Kate Bradbury’s One Garden against the World), too.

With thanks to Earth Books (Collective Ink) for the free copy for review.

Which of these do you fancy reading?

Book Serendipity, Mid-April to Mid-June

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away!

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Raising a wild animal but (mostly) calling it by its species rather than by a pet name (so “Pigeon” and “the leveret/hare”) in We Should All Be Birds by Brian Buckbee and Raising Hare by Chloe Dalton.

- Eating hash cookies in New York City in Women by Chloe Caldwell and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- A woman worries she’s left underclothes strewn about a room she’s about to show someone in one story of Single, Carefree, Mellow by Katherine Heiny and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

The dialogue is italicized in Women by Chloe Caldwell and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

The dialogue is italicized in Women by Chloe Caldwell and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

- The ‘you know it when you see it’ definition (originally for pornography) is cited in Moderation by Elaine Castillo and Bookish by Lucy Mangan.

- Women (including the protagonist) weightlifting in a gym in Moderation by Elaine Castillo and All Fours by Miranda July.

- Miranda July, whose All Fours I was also reading at the time, was mentioned in Chinese Parents Don’t Say I Love You by Candice Chung.

- A sibling story and a mystical light: late last year into early 2025 I read The Snow Queen by Michael Cunningham, and then I recognized this type of moment in Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

- A lesbian couple with a furniture store in Carol [The Price of Salt] by Patricia Highsmith and one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund.

- Not being able to see the stars in Las Vegas because of light pollution was mentioned in The Wild Dark by Craig Childs, then in Moderation by Elaine Castillo.

- A gynaecology appointment scene in All Fours by Miranda July and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- An awkwardly tall woman in Heartwood by Amity Gaige, How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney, and Stoner by John Williams.

- The 9/11 memorial lights’ disastrous effect on birds is mentioned in The Wild Dark by Craig Childs and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- A car accident precipitated by an encounter with wildlife is key to the denouement in the novellas Women by Chloe Caldwell and Wild Boar by Hannah Lutz.

- The plot is set in motion by the death of an older brother by drowning, and pork chops are served to an unexpected dinner guest, in Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven and Days of Light by Megan Hunter, both of which I was reading for Shelf Awareness review.

- Kids running around basically feral in a 1970s summer, and driving a box of human ashes around in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven.

- A character becomes a nun in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

- Wrens nesting just outside one’s front door in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman and Little Mercy by Robin Walter.

- ‘The female Woody Allen’ is the name given to a character in Women by Chloe Caldwell and then a description (in a blurb) of French author Nolwenn Le Blevennec.

- A children’s birthday party scene in Single, Carefree, Mellow by Katherine Heiny and Friends and Lovers by Nolwenn Le Blevennec. A children’s party is also mentioned in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and A Family Matter by Claire Lynch.

- A man who changes his child’s nappies, unlike his father – evidence of different notions of masculinity in different generations, in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson, What My Father and I Don’t Talk About, edited by Michele Filgate, and one piece in Beyond Touch Sites, edited by Wendy McGrath.

- What’s in a name? Repeated names I came across included Pansy (Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and Days of Light by Megan Hunter), Olivia (Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and A Family Matter by Claire Lynch), Jackson (Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and So Far Gone by Jess Walter), and Elias (Good Girl by Aria Aber and Dream State by Eric Puchner).

- The old wives’ tale that you should run in zigzags to avoid an alligator appeared in Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez and then in The Girls Who Grow Big by Leila Mottley, both initially set in Florida.

- A teenage girl is groped in a nightclub in Good Girl by Aria Aber and Girl, 1983 by Linn Ullmann.

- Discussion of the extinction of human and animal cultures and languages in both Nature’s Genius by David Farrier and Lifelines by Julian Hoffman, two May 2025 releases I was reading at the same time.

- In Body: My Life in Parts by Nina B. Lichtenstein, she mentions Linn Ullmann – who lived on her street in Oslo and went to the same school (not favourably – the latter ‘stole’ her best friend!); at the same time, I was reading Linn Ullmann’s Girl, 1983! And then, in both books, the narrator recalls getting a severe sunburn.

On the same day, I read about otter sightings in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman and Spring by Michael Morpurgo. The next day, I read about nesting swallows in both books.

On the same day, I read about otter sightings in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman and Spring by Michael Morpurgo. The next day, I read about nesting swallows in both books.

- The Salish people (Indigenous to North America) are mentioned in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman, Dream State by Eric Puchner (where Salish, the town in Montana, is also a setting), and So Far Gone by Jess Walter.

- Driving into a compound of extremists, and then the car being driven away by someone who’s not the owner, in Dream State by Eric Puchner and So Far Gone by Jess Walter.

- A woman worries about her (neurodivergent) husband saying weird things at a party in The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier and Normally Weird and Weirdly Normal by Robin Ince.

- Shooting raccoons in Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson and So Far Gone by Jess Walter. (Raccoons also feature in Dream State by Eric Puchner.)

- A graphic novelist has Hollywood types adding (or at least threatening to add) wholly unsuitable supernatural elements to their plots in Spent by Alison Bechdel and Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson.

- A novel in which a character named Dawn has to give up her daughter in the early 1980s, one right after the other: A Family Matter by Claire Lynch, followed by Love Forms by Claire Adam.

- A girl barricades her bedroom door for fear of her older brother in Love Forms by Claire Adam and Sleep by Honor Jones.

- A scene of an only child learning that her mother had a hysterectomy and so couldn’t have any more children in Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Other People’s Mothers by Julie Marie Wade.

- An African hotel cleaner features in Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and The Hotel by Daisy Johnson.

- Annie Dillard’s essay “Living Like Weasels” is mentioned in Nature’s Genius by David Farrier and The Dry Season by Melissa Febos.

- A woman assembles an inventory of her former lovers in Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and The Dry Season by Melissa Febos.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Book Serendipity, Mid-October to Mid-December 2022

The last entry in this series for the year. Those of you who join me for Love Your Library, note that I’ll host it on the 19th this month to avoid the holidays. Other than that, I don’t know how many more posts I’ll fit in before my year-end coverage (about six posts of best-of lists and statistics). Maybe I’ll manage a few more backlog reviews and a thematic roundup.

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every few months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Tom Swifties (a punning joke involving the way a quotation is attributed) in Savage Tales by Tara Bergin (“We get a lot of writers in here, said the rollercoaster operator lowering the bar”) and one of the stories in Birds of America by Lorrie Moore (“Would you like a soda? he asked spritely”).

- Prince’s androgynous symbol was on the cover of Dickens and Prince by Nick Hornby and is mentioned in the opening pages of Shameless by Nadia Bolz-Weber.

- Clarence Thomas is mentioned in one story of Birds of America by Lorrie Moore and Encore by May Sarton. (A function of them both dating to the early 1990s!)

- A kerfuffle over a ring belonging to the dead in one story of Shoot the Horses First by Leah Angstman and Motherthing by Ainslie Hogarth.

- Excellent historical fiction with a 2023 release date in which the amputation of a woman’s leg is a threat or a reality: one story of Shoot the Horses First by Leah Angstman and The House Is on Fire by Rachel Beanland.

- More of a real-life coincidence, this one: I was looking into Paradise, Piece by Piece by Molly Peacock, a memoir I already had on my TBR, because of an Instagram post I’d read about books that were influential on a childfree woman. Then, later the same day, my inbox showed that Molly Peacock herself had contacted me through my blog’s contact form, offering a review copy of her latest book!

- Reading nonfiction books titled The Heart of Things (by Richard Holloway) and The Small Heart of Things (by Julian Hoffman) at the same time.

- A woman investigates her husband’s past breakdown for clues to his current mental health in The Fear Index by Robert Harris and Motherthing by Ainslie Hogarth.

- “Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow” is a repeated phrase in Another Brooklyn by Jacqueline Woodson, as it was in Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin.

- Massive, much-anticipated novel by respected author who doesn’t publish very often, and that changed names along the way: John Irving’s The Last Chairlift (2022) was originally “Darkness as a Bride” (a better title!); Abraham Verghese’s The Covenant of Water (2023) started off as “The Maramon Convention.” I plan to read the Verghese but have decided against the Irving.

- Looting and white flight in New York City in Feral City by Jeremiah Moss and Another Brooklyn by Jacqueline Woodson.

- Two bereavement memoirs about a loved one’s death from pancreatic cancer: Ti Amo by Hanne Ørstavik and Crying in H Mart by Michelle Zauner.

- The Owl and the Pussycat of Edward Lear’s poem turn up in an update poem by Margaret Atwood in her collection The Door and in Anna James’s fifth Pages & Co. book, The Treehouse Library.

- Two books in which the author draws security attention for close observation of living things on the ground: Where the Wildflowers Grow by Leif Bersweden and The Lichen Museum by A. Laurie Palmer.

- Seal and human motherhood are compared in Zig-Zag Boy by Tanya Frank and All of Us Together in the End by Matthew Vollmer, two 2023 memoirs I’m enjoying a lot.

- Mystical lights appear in Animal Life by Auður Ava Ólafsdóttir (the Northern Lights, there) and All of Us Together in the End by Matthew Vollmer.

- St Vitus Dance is mentioned in Zig-Zag Boy by Tanya Frank and Robin by Helen F. Wilson.

- The history of white supremacy as a deliberate project in Oregon was a major element in Heaven Is a Place on Earth by Adrian Shirk, which I read earlier in the year, and has now recurred in The Distance from Slaughter County by Steven Moore.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

A Short Trip to Sedbergh, England’s Book Town

We’ve finally completed the ‘Triple Crown’ of British book towns: Hay-on-Wye in Wales is one of our favourite places and we’ve visited seven or more times over the years (the latest); inspired by Shaun Bythell’s memoirs, we then made the pilgrimage to Wigtown in Scotland in 2018. But we hadn’t made it to Sedbergh, England’s book town, until this past week. A short conference my husband was due to attend in the northwest of the country was the excuse we needed – though a medical emergency with our cat (fine now; just had to have an infected tooth out) shortened our trip and kept him from participating in the symposium at Lancaster.

Sedbergh is technically in Cumbria but falls within the Yorkshire Dales National Park. The book town initiative was part of a drive to re-invigorate the local economy after the 2001 foot and mouth disease outbreak. It’s a very sleepy town, more so than Hay or Wigtown, and only has two dedicated bookshops. The flagship store is Westwood Books, which was based in Hay until 2006 and occupies a former cinema / factory building. It is indeed reminiscent of Hay’s Cinema Bookshop, and is similar in size and stock to the largest of the Hay shops.

The only other shop in town that only sells books is Clutterbooks charity bookshop, where we started our book hunting after we left the car at our Airbnb flat on the Wednesday. With everything priced at £1 or £1.50, it tempted me into my first six purchases. Next up was Westwood, which opens until 5, an hour later than some other places. I bought a couple more books (delighted with the pristine secondhand copy of Julian Hoffman’s first nature book) but also resold them a small box of antiquarian and signed books for more than I could ever have hoped for – covering all my book purchases for the trip, as well as our meals and snacks out. On the Thursday we had a quiet drink in a cosy local pub to toast Her Majesty’s memory.

Various main street eateries and shops have a shelf or two of books for sale. We perused these, and the Little Free Library in the old bus shelter, on the Wednesday afternoon and first thing Friday morning. I added one more purchase to my stack – a paperback copy of Fire on the Mountain by Jean McNeil for £1 – just before we left town. In general, there weren’t as many bookshops as expected, and lots of places opened later or closed earlier than advertised, presumably because it was off season and rather rainy. So, it was a little underwhelming as book town experiences go, and I can’t imagine Sedbergh ever drawing us back.

However, we enjoyed exploring the area in general, with stops at Little Moreton Hall, and Sizergh Castle and Chester, respectively, on the way up and back. As part of the conference, we joined in a walk from Grange to Cartmel that took in an interesting limestone pavement landscape. It was my first time in the Dales or Lake District in many a year, and a good chance to get back to that pocket of the world.

Wainwright & Women’s Prize Predictions

A quick second post from me today since tonight is the announcement of the winners of the Wainwright Prize and tomorrow, September 9th, will be the announcement of the winner of the Women’s Prize for Fiction.

Wainwright Prize

I’d read 10 of the nominees before the shortlists were announced (see my mini-reviews and predictions). Since then I’ve managed to read one-third each of the two other books on the UK nature writing shortlist (I correctly predicted four of the seven on it), The Frayed Atlantic Edge by David Gange and On the Red Hill by Mike Parker. This is the first year that I’ve read nearly an entire Wainwright shortlist before the announcement. Even though I’m only partway through it … for its interdisciplinary approach – folklore, geology, history, nature writing and more, all wrapped up in a rollicking, well-written travelogue as he kayaks down the western coasts of the British Isles – I feel Gange should win, but the judges pretty much never pick what I think is the best book.

I’ve only read one of the books from the new global conservation shortlist, so I can’t make any kind of informed prediction. However, as it was my top nonfiction book of last year, I’d be delighted to see Irreplaceable by Julian Hoffman win.

Women’s Prize

It feels like an age since this shortlist was announced. I think the reason for delaying the winner announcement from early June to September was for there to be a chance of the ceremony going ahead as normal (though of course it will be online after all); it also gave people a chance to read the Mantel. If I’m being cynical, it was to drum up more interest and publicity in this 25th anniversary year, but I think that may have backfired – I was quite excited early on (see my thoughts on the longlist; my wish list correctly predicted four of the six on the shortlist), but long ago wearied of hearing about the Prize. It seems forever ago that I read some of the nominees.

I don’t think Cruz or Haynes has a chance of winning, but I could see a case for any of the other four taking the Prize. I’d love for it to go to Jenny Offill’s sharp, timely Weather; I’d be perfectly happy for it to go to Bernardine Evaristo’s stylish, multivocal Girl, Woman, Other; I’d not be surprised at all if it went to Hilary Mantel’s accomplished epic, The Mirror & The Light, though I think her work more suited to the Booker Prize; and I personally did not rate Hamnet (which has something of a pandemic theme) but would still be glad to see some recognition for Maggie O’Farrell. Evaristo or O’Farrell thus seems like the safest bet to me.

Best of 2019: Nonfiction

For me, 2019 has been a more memorable year for nonfiction than for fiction. Like I did last year, I’ve happened to choose 12 favorite nonfiction books – though after some thematic grouping this has ended up as a top 10 list. Bodies, archaeology, and the environmental crisis are recurring topics, reflecting my own interests but also, I think, something of the zeitgeist.

Let the countdown begin!

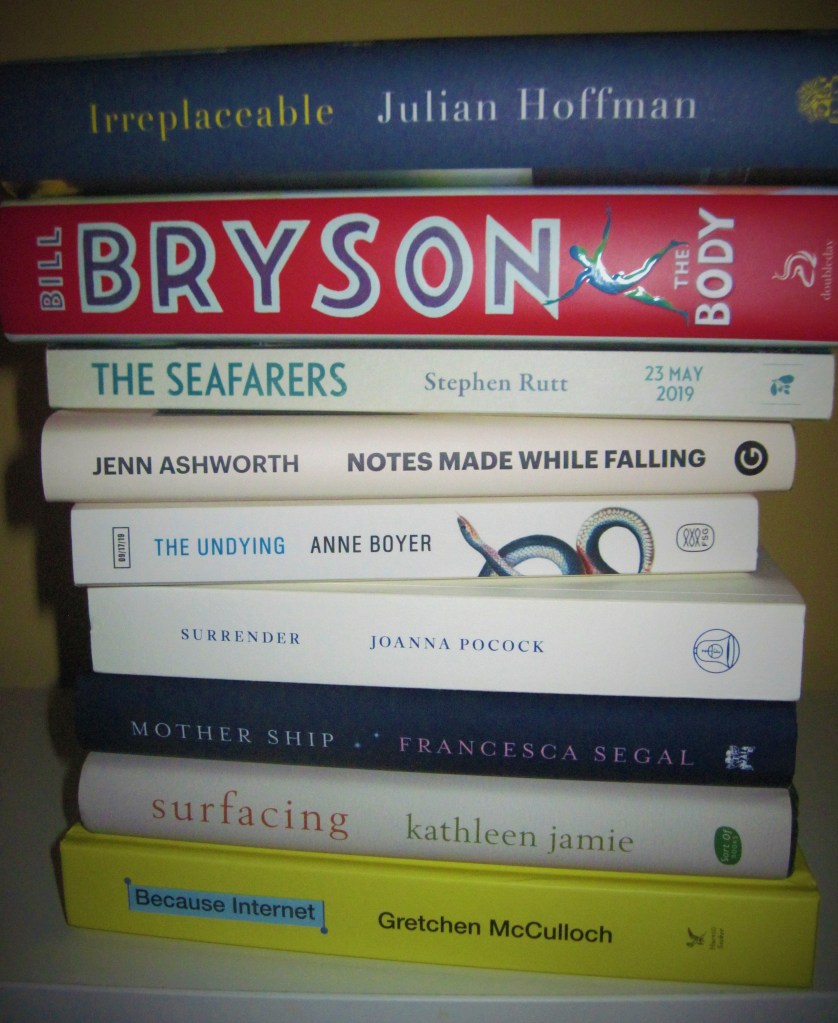

Because Internet: Understanding how language is changing by Gretchen McCulloch: Surprisingly fascinating stuff, even for a late adopter of technology. The Internet popularized informal writing and quickly incorporates changes in slang and cultural references. The book addresses things you may never have considered, like how we convey tone of voice through what we type and how emoji function as the gestures of the written word. Bursting with geeky enthusiasm.

Because Internet: Understanding how language is changing by Gretchen McCulloch: Surprisingly fascinating stuff, even for a late adopter of technology. The Internet popularized informal writing and quickly incorporates changes in slang and cultural references. The book addresses things you may never have considered, like how we convey tone of voice through what we type and how emoji function as the gestures of the written word. Bursting with geeky enthusiasm.

-

Surfacing by Kathleen Jamie: A fusion of autobiography with nature and travel writing – two genres that are too often dominated by men. Jamie has a particular interest in birds, islands, archaeology and the oddities of the human body, all subjects that intrigue me. There is beautiful nature writing to be found in this volume, as you might expect, but also relatable words on the human condition.

Surfacing by Kathleen Jamie: A fusion of autobiography with nature and travel writing – two genres that are too often dominated by men. Jamie has a particular interest in birds, islands, archaeology and the oddities of the human body, all subjects that intrigue me. There is beautiful nature writing to be found in this volume, as you might expect, but also relatable words on the human condition.

-

Mother Ship by Francesca Segal: A visceral diary of the first eight weeks in the lives of the author’s daughters, who were born by Caesarean section at 29 weeks in October 2015 and spent the next two months in the NICU. Segal describes with tender precision the feeling of being torn between writing and motherhood, and crafts twinkly pen portraits of others she encountered in the NICU, including the staff but especially her fellow preemie mums.

Mother Ship by Francesca Segal: A visceral diary of the first eight weeks in the lives of the author’s daughters, who were born by Caesarean section at 29 weeks in October 2015 and spent the next two months in the NICU. Segal describes with tender precision the feeling of being torn between writing and motherhood, and crafts twinkly pen portraits of others she encountered in the NICU, including the staff but especially her fellow preemie mums.

-

Surrender: Mid-Life in the American West by Joanna Pocock: Prompted by two years spent in Missoula, Montana and the disorientation felt upon a return to London, this memoir-in-essays varies in scale from the big skies of the American West to the smallness of one human life and the experience of loss and change. This is an elegantly introspective work that should engage anyone interested in women’s life writing and the environmental crisis.

Surrender: Mid-Life in the American West by Joanna Pocock: Prompted by two years spent in Missoula, Montana and the disorientation felt upon a return to London, this memoir-in-essays varies in scale from the big skies of the American West to the smallness of one human life and the experience of loss and change. This is an elegantly introspective work that should engage anyone interested in women’s life writing and the environmental crisis.

- (A tie) Constellations by Sinéad Gleeson / The Undying by Anne Boyer / Notes Made while Falling by Jenn Ashworth: Trenchant autobiographical essays about female pain. All three feel timely and inventive in how they bring together disparate topics to explore the possibilities and limitations of women’s bodies. A huge theme in life writing in the last couple of years and a great step toward trauma and chronic pain being taken seriously. (See also Notes to Self by Emilie Pine and the forthcoming Pain Studies by Lisa Olstein.)

-

Time Song: Searching for Doggerland by Julia Blackburn: Deep time is another key topic this year. Blackburn follows her curiosity wherever it leads as she does research into millions of years of history, including the much shorter story of human occupation. The writing is splendid, and the dashes of autobiographical information are just right, making her timely/timeless story personal. This would have been my Wainwright Prize winner.

Time Song: Searching for Doggerland by Julia Blackburn: Deep time is another key topic this year. Blackburn follows her curiosity wherever it leads as she does research into millions of years of history, including the much shorter story of human occupation. The writing is splendid, and the dashes of autobiographical information are just right, making her timely/timeless story personal. This would have been my Wainwright Prize winner.

-

The Seafarers: A Journey among Birds by Stephen Rutt: The young naturalist travelled the length and breadth of the British Isles – from Skomer to Shetland – courting encounters with seabirds. Discussion of the environmental threats that hit these species hardest, such as plastic pollution, makes for a timely tie-in to wider issues. The prose is elegantly evocative, and especially enjoyable because I’ve been to a lot of the island locations.

The Seafarers: A Journey among Birds by Stephen Rutt: The young naturalist travelled the length and breadth of the British Isles – from Skomer to Shetland – courting encounters with seabirds. Discussion of the environmental threats that hit these species hardest, such as plastic pollution, makes for a timely tie-in to wider issues. The prose is elegantly evocative, and especially enjoyable because I’ve been to a lot of the island locations.

-

Once More We Saw Stars by Jayson Greene: In 2015 the author’s two-year-old daughter, Greta, was fatally struck in the head by a brick that crumbled off an eighth-story Manhattan windowsill. Music journalist Greene explores all the ramifications of grief. I’ve read many a bereavement memoir and can’t remember a more searing account of the emotions and thoughts experienced moment to moment. The whole book has an aw(e)ful clarity to it.

Once More We Saw Stars by Jayson Greene: In 2015 the author’s two-year-old daughter, Greta, was fatally struck in the head by a brick that crumbled off an eighth-story Manhattan windowsill. Music journalist Greene explores all the ramifications of grief. I’ve read many a bereavement memoir and can’t remember a more searing account of the emotions and thoughts experienced moment to moment. The whole book has an aw(e)ful clarity to it.

-

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson: Bryson is back on form indulging his layman’s curiosity. Without ever being superficial or patronizing, he gives a comprehensive introduction to every organ and body system. He delights in our physical oddities, and his sense of wonder is contagious. Shelve this next to Being Mortal by Atul Gawande in a collection of books everyone should read – even if you don’t normally choose nonfiction.

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson: Bryson is back on form indulging his layman’s curiosity. Without ever being superficial or patronizing, he gives a comprehensive introduction to every organ and body system. He delights in our physical oddities, and his sense of wonder is contagious. Shelve this next to Being Mortal by Atul Gawande in a collection of books everyone should read – even if you don’t normally choose nonfiction.

-

Irreplaceable: The Fight to Save Our Wild Places by Julian Hoffman: Species and habitat loss are hard to comprehend even when we know the facts. This exquisitely written book is about taking stock, taking responsibility, and going beyond the numbers to tell the stories of front-line conservation work. Irreplaceable is an elegy of sorts, but, more importantly, it’s a call to arms. It places environmentalism in the hands of laypeople and offers hope that in working together in the spirit of defiance we can achieve great things. So, if you read one 2019 release, make it this one.

Irreplaceable: The Fight to Save Our Wild Places by Julian Hoffman: Species and habitat loss are hard to comprehend even when we know the facts. This exquisitely written book is about taking stock, taking responsibility, and going beyond the numbers to tell the stories of front-line conservation work. Irreplaceable is an elegy of sorts, but, more importantly, it’s a call to arms. It places environmentalism in the hands of laypeople and offers hope that in working together in the spirit of defiance we can achieve great things. So, if you read one 2019 release, make it this one.

(Books not pictured were read from the library or on Kindle.)

What were some of your top nonfiction reads of the year?

Upcoming posts:

28th: Runners-up

29th: Other superlatives and some statistics

30th: Best backlist reads

31st: The final figures on my 2019 reading

Reviews for Shiny New Books & TLS, Plus Simon’s “My Life in Books”

I recently participated in the one-week “My Life in Books” extravaganza hosted by Simon Thomas (Stuck in a Book), where he asks bloggers to choose five books that have been important to them at different points in their reading lives. The neat twist is that he puts the bloggers in pairs and asks them to comment anonymously on their partner’s reading choices and even come up with an apt book recommendation or two. A few of my selections will be familiar from the two Landmark Books posts I wrote in 2016 (here and here), but a couple are new, and it was fun to think about what’s changed versus what’s endured in my reading taste.

Shiny New Books

Irreplaceable by Julian Hoffman: If you read one 2019 release, make it this one. (It’s too important a book to dilute that statement with qualifiers.) Species and habitat loss are hard to comprehend even when we know the facts. This book is a way of taking stock, taking responsibility, and going beyond the numbers to tell the stories of front-line conservation work. From the Kent marshes to the Coral Triangle off Indonesia, Hoffman discovers the situation on the ground and talks to the people involved in protecting places at risk of destruction. Reassuringly, these aren’t usually genius scientists or well-funded heroes, but ordinary citizens who are concerned about preserving nearby sites that mean something to them. Irreplaceable is an elegy of sorts, but, more importantly, it’s a call to arms. It places environmentalism in the hands of laypeople and offers hope that in working together in the spirit of defiance we can achieve great things. It takes local concerns seriously, yet its scope is international. But what truly lifts Hoffman’s work above most recent nature books is the exquisite prose.

Irreplaceable by Julian Hoffman: If you read one 2019 release, make it this one. (It’s too important a book to dilute that statement with qualifiers.) Species and habitat loss are hard to comprehend even when we know the facts. This book is a way of taking stock, taking responsibility, and going beyond the numbers to tell the stories of front-line conservation work. From the Kent marshes to the Coral Triangle off Indonesia, Hoffman discovers the situation on the ground and talks to the people involved in protecting places at risk of destruction. Reassuringly, these aren’t usually genius scientists or well-funded heroes, but ordinary citizens who are concerned about preserving nearby sites that mean something to them. Irreplaceable is an elegy of sorts, but, more importantly, it’s a call to arms. It places environmentalism in the hands of laypeople and offers hope that in working together in the spirit of defiance we can achieve great things. It takes local concerns seriously, yet its scope is international. But what truly lifts Hoffman’s work above most recent nature books is the exquisite prose. ![]()

Times Literary Supplement

These three reviews are forthcoming.

The Heat of the Moment: Life and Death Decision-Making from a Firefighter by Sabrina Cohen-Hatton: Cohen-Hatton is one of the UK’s highest-ranking female firefighters. A few perilous situations inspired her to investigate how people make decisions under pressure. For a PhD in Psychology from Cardiff University, she delved into the neurology of decision-making. Although there is jargon in the book, she explains the terms well and uses relatable metaphors. However, the context about her research can be repetitive and basic, as if dumbed down for a general reader. The book shines when giving blow-by-blow accounts of real-life or composite incidents. Potential readers should bear in mind, though, that this is ultimately more of a management psychology book than a memoir.

The Heat of the Moment: Life and Death Decision-Making from a Firefighter by Sabrina Cohen-Hatton: Cohen-Hatton is one of the UK’s highest-ranking female firefighters. A few perilous situations inspired her to investigate how people make decisions under pressure. For a PhD in Psychology from Cardiff University, she delved into the neurology of decision-making. Although there is jargon in the book, she explains the terms well and uses relatable metaphors. However, the context about her research can be repetitive and basic, as if dumbed down for a general reader. The book shines when giving blow-by-blow accounts of real-life or composite incidents. Potential readers should bear in mind, though, that this is ultimately more of a management psychology book than a memoir. ![]()

Henry David Thoreau’s Walden (1854), a record of his two-year experiment living alone in a cabin near a Massachusetts pond, has inspired innumerable back-to-nature adventures, including these two books I discuss together in a longer article.

The Outermost House: A Year of Life on the Great Beach of Cape Cod by Henry Beston: Beston had a two-room wooden shack built at Cape Cod in 1925. Although he only intended to spend a fortnight of the following summer in the sixteen-by-twenty-foot dwelling, he stayed a year. The chronicle of that year, The Outermost House (originally published in 1928 and previously out of print in the UK), is a charming meditation on the turning of the seasons and the sometimes terrifying power of the sea. The writing is often poetic, with sibilance conjuring the sound of the ocean. Beston will be remembered for his statement of the proper relationship between humans and the natural world. “We need another and a wiser and perhaps a more mystical concept of animals,” he declares; “they are not underlings; they are other nations.” One word stands out in The Outermost House: “elemental” appears a dozen times, evoking the grandeur of nature and the necessity of getting back to life’s basics.

The Outermost House: A Year of Life on the Great Beach of Cape Cod by Henry Beston: Beston had a two-room wooden shack built at Cape Cod in 1925. Although he only intended to spend a fortnight of the following summer in the sixteen-by-twenty-foot dwelling, he stayed a year. The chronicle of that year, The Outermost House (originally published in 1928 and previously out of print in the UK), is a charming meditation on the turning of the seasons and the sometimes terrifying power of the sea. The writing is often poetic, with sibilance conjuring the sound of the ocean. Beston will be remembered for his statement of the proper relationship between humans and the natural world. “We need another and a wiser and perhaps a more mystical concept of animals,” he declares; “they are not underlings; they are other nations.” One word stands out in The Outermost House: “elemental” appears a dozen times, evoking the grandeur of nature and the necessity of getting back to life’s basics. ![]()

(See also Susan’s review of this one.)

Homesick: Why I Live in a Shed by Catrina Davies: Davies crosses Thoreauvian language – many chapter titles and epigraphs are borrowed from Walden – with a Woolfian search for a room of her own. Penniless during an ongoing housing crisis and reeling from a series of precarious living situations, she moved into the shed near Land’s End that had served as her father’s architecture office until he went bankrupt. Like Raynor Winn’s The Salt Path, this intimate, engaging memoir is a sobering reminder that homelessness is not so remote, and education is no guarantee of success. There is, understandably, a sense of righteous indignation here against a land-owning class – including the lord who owns much of the area where she lives and works – and government policies that favour the wealthy.

Homesick: Why I Live in a Shed by Catrina Davies: Davies crosses Thoreauvian language – many chapter titles and epigraphs are borrowed from Walden – with a Woolfian search for a room of her own. Penniless during an ongoing housing crisis and reeling from a series of precarious living situations, she moved into the shed near Land’s End that had served as her father’s architecture office until he went bankrupt. Like Raynor Winn’s The Salt Path, this intimate, engaging memoir is a sobering reminder that homelessness is not so remote, and education is no guarantee of success. There is, understandably, a sense of righteous indignation here against a land-owning class – including the lord who owns much of the area where she lives and works – and government policies that favour the wealthy. ![]()

Live Fast by Brigitte Giraud (trans. from the French by Cory Stockwell) [Feb. 11, Ecco]: I found out about this autofiction novella via an early

Live Fast by Brigitte Giraud (trans. from the French by Cory Stockwell) [Feb. 11, Ecco]: I found out about this autofiction novella via an early  The Unworthy by Agustina Bazterrica (trans. from the Spanish by Sarah Moses) [13 Feb., Pushkin; March 4, Scribner]: I wasn’t enamoured of the Argentinian author’s

The Unworthy by Agustina Bazterrica (trans. from the Spanish by Sarah Moses) [13 Feb., Pushkin; March 4, Scribner]: I wasn’t enamoured of the Argentinian author’s  Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito [13 Feb., Fourth Estate; Feb. 4, Liveright]: Feito’s debut,

Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito [13 Feb., Fourth Estate; Feb. 4, Liveright]: Feito’s debut,

The Swell by Kat Gordon [27 Feb., Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: I got vague The Mercies (Kiran Millwood Hargrave) vibes from the blurb. “Iceland, 1910. In the middle of a severe storm two sisters, Freyja and Gudrun, rescue a mysterious, charismatic man from a shipwreck near their remote farm. Sixty-five years later, a young woman, Sigga, is spending time with her grandmother when they learn a body has been discovered on a mountainside near Reykjavik, perfectly preserved in ice.” (NetGalley download)

The Swell by Kat Gordon [27 Feb., Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: I got vague The Mercies (Kiran Millwood Hargrave) vibes from the blurb. “Iceland, 1910. In the middle of a severe storm two sisters, Freyja and Gudrun, rescue a mysterious, charismatic man from a shipwreck near their remote farm. Sixty-five years later, a young woman, Sigga, is spending time with her grandmother when they learn a body has been discovered on a mountainside near Reykjavik, perfectly preserved in ice.” (NetGalley download) Kate & Frida by Kim Fay [March 11, G.P. Putnam’s Sons]: “Frida Rodriguez arrives in Paris in 1991 … But then she writes to a bookshop in Seattle … A friendship begins that will redefine the person she wants to become. Seattle bookseller Kate Fair is transformed by Frida’s free spirit … [A] love letter to bookshops and booksellers, to the passion we bring to life in our twenties”. Sounds like a cross between The Paris Novel and 84 Charing Cross Road – could be fab; could be twee. We shall see! (Edelweiss download)

Kate & Frida by Kim Fay [March 11, G.P. Putnam’s Sons]: “Frida Rodriguez arrives in Paris in 1991 … But then she writes to a bookshop in Seattle … A friendship begins that will redefine the person she wants to become. Seattle bookseller Kate Fair is transformed by Frida’s free spirit … [A] love letter to bookshops and booksellers, to the passion we bring to life in our twenties”. Sounds like a cross between The Paris Novel and 84 Charing Cross Road – could be fab; could be twee. We shall see! (Edelweiss download) The Antidote by Karen Russell [13 March, Chatto & Windus (Penguin) / March 11, Knopf]: I love Russell’s

The Antidote by Karen Russell [13 March, Chatto & Windus (Penguin) / March 11, Knopf]: I love Russell’s  Elegy, Southwest by Madeleine Watts [13 March, ONE (Pushkin) / Feb. 18, Simon & Schuster]: Watts’s debut,

Elegy, Southwest by Madeleine Watts [13 March, ONE (Pushkin) / Feb. 18, Simon & Schuster]: Watts’s debut,  O Sinners! by Nicole Cuffy [March 18, One World (Random House)]: Cuffy’s

O Sinners! by Nicole Cuffy [March 18, One World (Random House)]: Cuffy’s  The Accidentals: Stories by Guadalupe Nettel (trans. from the Spanish by Rosalind Harvey) [10 April, Fitzcarraldo Editions / April 29, Bloomsbury]: I really enjoyed Nettel’s International Booker-shortlisted novel

The Accidentals: Stories by Guadalupe Nettel (trans. from the Spanish by Rosalind Harvey) [10 April, Fitzcarraldo Editions / April 29, Bloomsbury]: I really enjoyed Nettel’s International Booker-shortlisted novel  Ordinary Saints by Niamh Ni Mhaoileoin [24 April, Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: “Brought up in a devout household in Ireland, Jay is now living in London with her girlfriend, determined to live day to day and not think too much about either the future or the past. But when she learns that her beloved older brother, who died in a terrible accident, may be made into a Catholic saint, she realises she must at last confront her family, her childhood and herself.” Winner of the inaugural PFD Queer Fiction Prize and shortlisted for the Women’s Prize Discoveries Award.

Ordinary Saints by Niamh Ni Mhaoileoin [24 April, Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: “Brought up in a devout household in Ireland, Jay is now living in London with her girlfriend, determined to live day to day and not think too much about either the future or the past. But when she learns that her beloved older brother, who died in a terrible accident, may be made into a Catholic saint, she realises she must at last confront her family, her childhood and herself.” Winner of the inaugural PFD Queer Fiction Prize and shortlisted for the Women’s Prize Discoveries Award. Heartwood by Amity Gaige [1 May, Fleet / April 1, Simon & Schuster]: I loved Gaige’s

Heartwood by Amity Gaige [1 May, Fleet / April 1, Simon & Schuster]: I loved Gaige’s  Ripeness by Sarah Moss [22 May, Picador / Sept. 9, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Though I was disappointed by her last two novels, I’ll read anything Moss publishes and hope for a return to form. “It is the [19]60s and … Edith finds herself travelling to rural Italy … to see her sister, ballet dancer Lydia, through the final weeks of her pregnancy, help at the birth and then make a phone call which will seal this baby’s fate, and his mother’s.” Promises to be “about migration and new beginnings, and about what it is to have somewhere to belong.”

Ripeness by Sarah Moss [22 May, Picador / Sept. 9, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Though I was disappointed by her last two novels, I’ll read anything Moss publishes and hope for a return to form. “It is the [19]60s and … Edith finds herself travelling to rural Italy … to see her sister, ballet dancer Lydia, through the final weeks of her pregnancy, help at the birth and then make a phone call which will seal this baby’s fate, and his mother’s.” Promises to be “about migration and new beginnings, and about what it is to have somewhere to belong.” The Forgotten Sense: The New Science of Smell by Jonas Olofsson [Out now! 7 Jan., William Collins / Mariner]: Part of a planned deep dive into the senses. “Smell is … one of our most sensitive and refined senses; few other mammals surpass our ability to perceive scents in the animal kingdom. Yet, as the millions of people who lost their sense of smell during the COVID-19 pandemic can attest, we too often overlook its role in our overall health. … For readers of Bill Bryson and Steven Pinker”. (On order from library)

The Forgotten Sense: The New Science of Smell by Jonas Olofsson [Out now! 7 Jan., William Collins / Mariner]: Part of a planned deep dive into the senses. “Smell is … one of our most sensitive and refined senses; few other mammals surpass our ability to perceive scents in the animal kingdom. Yet, as the millions of people who lost their sense of smell during the COVID-19 pandemic can attest, we too often overlook its role in our overall health. … For readers of Bill Bryson and Steven Pinker”. (On order from library) Bread and Milk by Karolina Ramqvist (trans. from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel) [13 Feb., Bonnier Books / Feb. 11, Coach House Books]: I think I first found about this via the early

Bread and Milk by Karolina Ramqvist (trans. from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel) [13 Feb., Bonnier Books / Feb. 11, Coach House Books]: I think I first found about this via the early  My Mother in Havana: A Memoir of Magic & Miracle by Rebe Huntman [Feb. 18, Monkfish]: I found out about this from

My Mother in Havana: A Memoir of Magic & Miracle by Rebe Huntman [Feb. 18, Monkfish]: I found out about this from  Mother Animal by Helen Jukes [27 Feb., Elliott & Thompson]: This may be the 2025 release I’ve known about for the longest. I remember expressing interest the first time the author tweeted about it; it’s bound to be a good follow-up to Lucy Jones’s

Mother Animal by Helen Jukes [27 Feb., Elliott & Thompson]: This may be the 2025 release I’ve known about for the longest. I remember expressing interest the first time the author tweeted about it; it’s bound to be a good follow-up to Lucy Jones’s  Alive: An Alternative Anatomy by Gabriel Weston [6 March, Vintage (Penguin) / March 4, David R. Godine]: I’ve read Weston’s

Alive: An Alternative Anatomy by Gabriel Weston [6 March, Vintage (Penguin) / March 4, David R. Godine]: I’ve read Weston’s  The Lost Trees of Willow Avenue: A Story of Climate and Hope on One American Street by Mike Tidwell [March 25, St. Martin’s Press]: A must-read for me because it’s set in Takoma Park, Maryland, where I was born. “A love letter to the magnificent oaks and other trees dying from record heat waves and bizarre rain, [activist] Tidwell’s story depicts the neighborhood’s battle to save the trees and combat climate change. … Tidwell chronicles people on his block sick with Lyme disease, a church struggling with floods, and young people anguishing over whether to have kids, … against the global backdrop of 2023’s record heat domes and raging wildfires and hurricanes.”

The Lost Trees of Willow Avenue: A Story of Climate and Hope on One American Street by Mike Tidwell [March 25, St. Martin’s Press]: A must-read for me because it’s set in Takoma Park, Maryland, where I was born. “A love letter to the magnificent oaks and other trees dying from record heat waves and bizarre rain, [activist] Tidwell’s story depicts the neighborhood’s battle to save the trees and combat climate change. … Tidwell chronicles people on his block sick with Lyme disease, a church struggling with floods, and young people anguishing over whether to have kids, … against the global backdrop of 2023’s record heat domes and raging wildfires and hurricanes.” Breasts: A Relatively Brief Relationship by Jean Hannah Edelstein [3 April, Phoenix (W&N)]: I loved Edelstein’s 2018 memoir

Breasts: A Relatively Brief Relationship by Jean Hannah Edelstein [3 April, Phoenix (W&N)]: I loved Edelstein’s 2018 memoir  Poets Square: A Memoir in Thirty Cats by Courtney Gustafson [8 May, Fig Tree (Penguin) / April 29, Crown]: Gustafson became an Instagram and TikTok hit with her posts about looking after a feral cat colony in Tucson, Arizona. The money she raised via social media allowed her to buy her home and continue caring for animals. “[Gustafson] had no idea about the grief and hardship of animal rescue, the staggering size of the problem in neighborhoods across the country. And she couldn’t have imagined how that struggle … would help pierce a personal darkness she’d wrestled for with much of her life.” (Proof copy from publisher)

Poets Square: A Memoir in Thirty Cats by Courtney Gustafson [8 May, Fig Tree (Penguin) / April 29, Crown]: Gustafson became an Instagram and TikTok hit with her posts about looking after a feral cat colony in Tucson, Arizona. The money she raised via social media allowed her to buy her home and continue caring for animals. “[Gustafson] had no idea about the grief and hardship of animal rescue, the staggering size of the problem in neighborhoods across the country. And she couldn’t have imagined how that struggle … would help pierce a personal darkness she’d wrestled for with much of her life.” (Proof copy from publisher) Spent: A Comic Novel by Alison Bechdel [22 May, Jonathan Cape (Penguin) / May 20, Mariner Books]: Bechdel’s

Spent: A Comic Novel by Alison Bechdel [22 May, Jonathan Cape (Penguin) / May 20, Mariner Books]: Bechdel’s

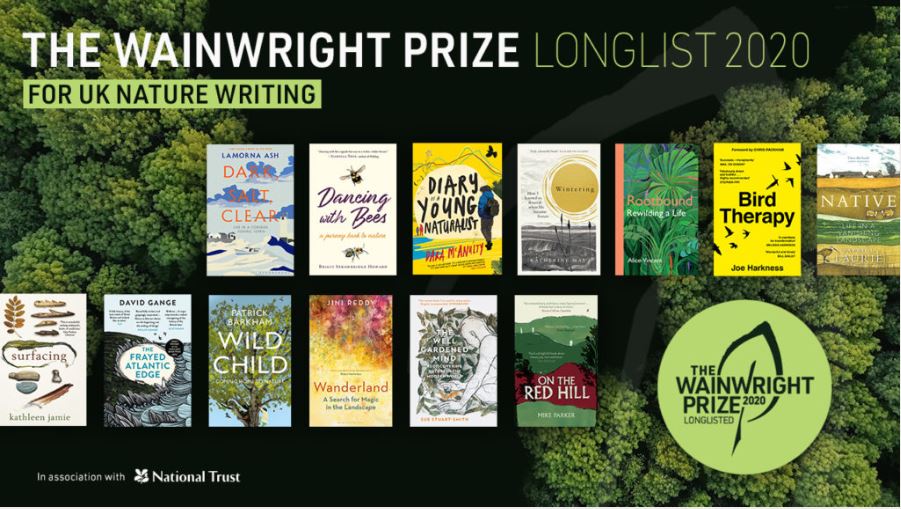

Dark, Salt, Clear: Life in a Cornish Fishing Town by Lamorna Ash: In her early 20s, Ash made multiple trips from London to stay in Newlyn: walking to the cove that bears her name, going out on fishing trawlers, and getting accepted into the small community. Gruelling and lonely, the fishermen’s way of life is fading away. The book goes deeper into Cornish history than non-locals need, but I enjoyed the literary allusions – the title is from Elizabeth Bishop. I liked the writing, but this was requested after me at the library, so I could only skim it.

Dark, Salt, Clear: Life in a Cornish Fishing Town by Lamorna Ash: In her early 20s, Ash made multiple trips from London to stay in Newlyn: walking to the cove that bears her name, going out on fishing trawlers, and getting accepted into the small community. Gruelling and lonely, the fishermen’s way of life is fading away. The book goes deeper into Cornish history than non-locals need, but I enjoyed the literary allusions – the title is from Elizabeth Bishop. I liked the writing, but this was requested after me at the library, so I could only skim it.

Bird Therapy by Joe Harkness: In 2013, Harkness was in such a bad place that he attempted suicide. Although he’s continued to struggle with OCD and depression in the years since then, birdwatching has given him a new lease on life. Avoiding the hobby’s more obsessive, competitive aspects (like listing and twitching), he focuses on the benefits of outdoor exercise and mindfulness. He can be lyrical when describing his Norfolk patch and some of his most magical sightings, but the writing is weak. (My husband helped crowdfund the book via Unbound.)

Bird Therapy by Joe Harkness: In 2013, Harkness was in such a bad place that he attempted suicide. Although he’s continued to struggle with OCD and depression in the years since then, birdwatching has given him a new lease on life. Avoiding the hobby’s more obsessive, competitive aspects (like listing and twitching), he focuses on the benefits of outdoor exercise and mindfulness. He can be lyrical when describing his Norfolk patch and some of his most magical sightings, but the writing is weak. (My husband helped crowdfund the book via Unbound.)  Dancing with Bees: A Journey Back to Nature by Brigit Strawbridge Howard: Bees were the author’s gateway into a general appreciation of nature, something she lost for a time in midlife because of the rat race and family complications. Allotment gardening gives her opportunities to observe bee behaviour and marvel at their various lookalikes (like hoverflies), identify plants, work on herbal remedies, and photograph her finds. She delights in discovery and is devoted to lifelong learning in a book characterized by curiosity and warmth. (On my runners-up of 2019 list)

Dancing with Bees: A Journey Back to Nature by Brigit Strawbridge Howard: Bees were the author’s gateway into a general appreciation of nature, something she lost for a time in midlife because of the rat race and family complications. Allotment gardening gives her opportunities to observe bee behaviour and marvel at their various lookalikes (like hoverflies), identify plants, work on herbal remedies, and photograph her finds. She delights in discovery and is devoted to lifelong learning in a book characterized by curiosity and warmth. (On my runners-up of 2019 list)

I think this year’s is an especially appealing longlist. It’s great to see small presses and debut authors getting recognition. I’ve now read 8 out of 13 (and skimmed one), and am interested in the rest, too, especially The Frayed Atlantic Edge by David Gange. The final three, all combining nature and (auto)biographical writing, are On the Red Hill by Mike Parker, The Well-Gardened Mind by Sue Stuart-Smith, and Rootbound: Rewilding a Life by Alice Vincent.

I think this year’s is an especially appealing longlist. It’s great to see small presses and debut authors getting recognition. I’ve now read 8 out of 13 (and skimmed one), and am interested in the rest, too, especially The Frayed Atlantic Edge by David Gange. The final three, all combining nature and (auto)biographical writing, are On the Red Hill by Mike Parker, The Well-Gardened Mind by Sue Stuart-Smith, and Rootbound: Rewilding a Life by Alice Vincent.

Notes from an Apocalypse: A Personal Journey to the End of the World and Back by Mark O’Connell: The same satirical outlook that made

Notes from an Apocalypse: A Personal Journey to the End of the World and Back by Mark O’Connell: The same satirical outlook that made

References to Edgar Allan Poe in both Timbuktu by Paul Auster and The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards by Kristopher Jansma.

References to Edgar Allan Poe in both Timbuktu by Paul Auster and The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards by Kristopher Jansma.

A character has a nice cup of Ovaltine in Some Tame Gazelle by Barbara Pym and The Stillness The Dancing by Wendy Perriam.

A character has a nice cup of Ovaltine in Some Tame Gazelle by Barbara Pym and The Stillness The Dancing by Wendy Perriam.

Two books I finished about the same time conclude by quoting or referring to the T. S. Eliot lines about coming back to the place where you started and knowing it for the first time (Owl Sense by Miriam Darlington and This Is Not a Drill, the Extinction Rebellion handbook).

Two books I finished about the same time conclude by quoting or referring to the T. S. Eliot lines about coming back to the place where you started and knowing it for the first time (Owl Sense by Miriam Darlington and This Is Not a Drill, the Extinction Rebellion handbook).

At a fertility clinic, the author describes a pair of transferred embryos as “two sequins of light” (in On Chapel Sands by Laura Cumming) and “two points of light” (in Expectation by Anna Hope).

At a fertility clinic, the author describes a pair of transferred embryos as “two sequins of light” (in On Chapel Sands by Laura Cumming) and “two points of light” (in Expectation by Anna Hope). Incorporation of a mother’s brief memoir in the author’s own memoir in On Chapel Sands by Laura Cumming and All Things Consoled by Elizabeth Hay.

Incorporation of a mother’s brief memoir in the author’s own memoir in On Chapel Sands by Laura Cumming and All Things Consoled by Elizabeth Hay.

An Irish-American family in a major East Coast city where the teenage boy does construction work during the summers in Ask Again, Yes by Mary Beth Keane and The Dutch House by Ann Patchett.

An Irish-American family in a major East Coast city where the teenage boy does construction work during the summers in Ask Again, Yes by Mary Beth Keane and The Dutch House by Ann Patchett.

“I was nineteen years old and an idiot” (City of Girls, Elizabeth Gilbert); “I was fifteen and generally an idiot” (The Dutch House, Ann Patchett).

“I was nineteen years old and an idiot” (City of Girls, Elizabeth Gilbert); “I was fifteen and generally an idiot” (The Dutch House, Ann Patchett).

Kripalu (a Massachusetts retreat center) is mentioned in Fleishman Is in Trouble by Taffy Brodesser-Akner and Once More We Saw Stars by Jayson Greene.

Kripalu (a Massachusetts retreat center) is mentioned in Fleishman Is in Trouble by Taffy Brodesser-Akner and Once More We Saw Stars by Jayson Greene.