The 2024 McKitterick Prize Shortlist and Winner

For the third year in a row, I was a first-round judge for the McKitterick Prize (for a first novel, published or unpublished, by a writer over 40), helping to assess the unpublished manuscripts. The McKitterick Prize is in memory of Tom McKitterick and sponsored by the Hawthornden Foundation. Thus far an unpublished manuscript has not advanced to the shortlist, but maybe one year it will!

On the 2024 McKitterick Prize shortlist (synopses adapted from Goodreads):

Jacqueline Crooks for Fire Rush (Jonathan Cape, Vintage, Penguin Random House) – “Set amid the Jamaican diaspora in London at the dawn of 1980s, a mesmerizing story of love, loss, and self-discovery that vibrates with the liberating power of music. When Yamaye meets Moose, a soulful carpenter who shares her Jamaican heritage, a path toward a different kind of future seems to open. But then, Babylon rushes in.”

Jacqueline Crooks for Fire Rush (Jonathan Cape, Vintage, Penguin Random House) – “Set amid the Jamaican diaspora in London at the dawn of 1980s, a mesmerizing story of love, loss, and self-discovery that vibrates with the liberating power of music. When Yamaye meets Moose, a soulful carpenter who shares her Jamaican heritage, a path toward a different kind of future seems to open. But then, Babylon rushes in.”

Chidi Ebere for Now I Am Here (Pan Macmillan, Picador) – “We begin at the end. The armies of the National Defence Movement have been crushed and our unnamed narrator and his unit are surrounded. As he recounts the events leading to his disastrous finale, we learn how this gentle man is gradually transformed into a war criminal, committing acts he wouldn’t have thought himself capable.”

Chidi Ebere for Now I Am Here (Pan Macmillan, Picador) – “We begin at the end. The armies of the National Defence Movement have been crushed and our unnamed narrator and his unit are surrounded. As he recounts the events leading to his disastrous finale, we learn how this gentle man is gradually transformed into a war criminal, committing acts he wouldn’t have thought himself capable.”

Aoife Fitzpatrick for The Red Bird Sings (Virago) – “West Virginia, 1897. When young Zona Heaster Shue dies only a few months after her wedding, her mother, Mary Jane, becomes convinced Zona was murdered by her husband, Trout, the town blacksmith. As the trial rises to fever pitch, with the men of Greenbrier County aligned against them, Mary Jane and Zona’s best friend Lucy must decide whether to reveal Zona’s greatest secret in the service of justice.”

Aoife Fitzpatrick for The Red Bird Sings (Virago) – “West Virginia, 1897. When young Zona Heaster Shue dies only a few months after her wedding, her mother, Mary Jane, becomes convinced Zona was murdered by her husband, Trout, the town blacksmith. As the trial rises to fever pitch, with the men of Greenbrier County aligned against them, Mary Jane and Zona’s best friend Lucy must decide whether to reveal Zona’s greatest secret in the service of justice.”

Greg Jackson for The Dimensions of a Cave (Granta) – “When investigative reporter Quentin Jones’s story about covert military interrogation practices in the Desert War is buried, he is spurred to dig deeper, and he unravels a trail that leads to VIRTUE: cutting-edge technology that simulates reality during interrogation. As the shadowy labyrinths of governmental corruption unfurl and tighten around him, unnerving links to his protégé – who, like Joseph Conrad’s Kurtz, disappeared in the war several years earlier – keep emerging.”

Greg Jackson for The Dimensions of a Cave (Granta) – “When investigative reporter Quentin Jones’s story about covert military interrogation practices in the Desert War is buried, he is spurred to dig deeper, and he unravels a trail that leads to VIRTUE: cutting-edge technology that simulates reality during interrogation. As the shadowy labyrinths of governmental corruption unfurl and tighten around him, unnerving links to his protégé – who, like Joseph Conrad’s Kurtz, disappeared in the war several years earlier – keep emerging.”

Wenyan Lu for The Funeral Cryer (Atlantic Books, Allen & Unwin) – “The Funeral Cryer long ago accepted the mundane realities of her life: avoided by fellow villagers because of the stigma attached to her job and under-appreciated by her husband, whose fecklessness has pushed the couple close to the brink of break-up. But just when things couldn’t be bleaker, she takes a leap of faith – and in so doing things start to take a surprising turn for the better.”

Wenyan Lu for The Funeral Cryer (Atlantic Books, Allen & Unwin) – “The Funeral Cryer long ago accepted the mundane realities of her life: avoided by fellow villagers because of the stigma attached to her job and under-appreciated by her husband, whose fecklessness has pushed the couple close to the brink of break-up. But just when things couldn’t be bleaker, she takes a leap of faith – and in so doing things start to take a surprising turn for the better.”

Allan Radcliffe for The Old Haunts (Fairlight Books) – “Recently bereaved Jamie is staying at a rural steading in the heart of Scotland with his actor boyfriend Alex. The sudden loss of both of Jamie’s parents hangs like a shadow over the trip. In his grief, Jamie finds himself sifting through bittersweet memories, from his working-class upbringing in Edinburgh to his bohemian twenties in London, with a growing awareness of his sexuality threaded through.”

Allan Radcliffe for The Old Haunts (Fairlight Books) – “Recently bereaved Jamie is staying at a rural steading in the heart of Scotland with his actor boyfriend Alex. The sudden loss of both of Jamie’s parents hangs like a shadow over the trip. In his grief, Jamie finds himself sifting through bittersweet memories, from his working-class upbringing in Edinburgh to his bohemian twenties in London, with a growing awareness of his sexuality threaded through.”

The Society of Authors kindly sent me free copies of the six shortlisted novels. I already had The Red Bird Sings and The Funeral Cryer on my TBR, so I’m particularly looking forward to reading them as part of my 20 Books of Summer – which I’ve decided might as well contain, as well as all hardbacks, only books by women.

I was familiar with Fire Rush from its shortlisting for last year’s Women’s Prize for Fiction. The other three titles are new to me but sound interesting, especially The Old Haunts – at 150 pages, it will be perfect for Novellas in November.

My fellow judge Rónán Hession, whom I got to meet very briefly on a Zoom call, wrote: “It is exciting to judge a prize and encounter such a depth of talent. Though [the books] hugely varied in subject matter and style, the writers on the shortlist all impressed me with the clarity of their creative vision and their narrative authority on the page.”

The winner and runner-up were announced in advance of the SoA Awards ceremony in London yesterday evening. As in other years, I watched the livestream, which this year included captivating speeches by the Very Revd Dr Mark Oakley, Dean of Southwark Cathedral (where the ceremony took place) and Kate Mosse. And what a thrill it was to see and hear my name on the livestream!

Winner: Wenyan Lu for The Funeral Cryer

Runner-up: Chidi Ebere for Now I Am Here

In the press release announcing the winners, Hession said, “Wenyan Lu has created an unforgettable debut, brimming with personality and written with a sense of consummate ease. The Funeral Cryer is such a funny, warm and original book. An absolute gem of a novel.” I can’t wait to get started!

Other notable winners announced yesterday included:

- Tom Crewe for The New Life (Betty Trask Prize for a first novel by a writer under 35)

- Jacqueline Crooks for Fire Rush (Paul Torday Memorial Prize for a first novel by a writer over 60 – how perfect for her to win this in place of the McKitterick!)

- Soula Emmanuel for Wild Geese (Gordon Bowker Volcano Prize for a novel focusing on travel)

- Cecile Pin for Wandering Souls (Runner-up for the Gordon Bowker Volcano Prize; and a Somerset Maugham Award travel bursary)

Doorstopper of the Month: The Absolute Book by Elizabeth Knox (2019)

Epic fantasy is far from my usual fare, but this was a book worth getting lost in. The reading experience reminded me of what I had with A Discovery of Witches by Deborah Harkness, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle by Haruki Murakami, or perhaps Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell by Susanna Clarke – though it’s possible this last association was only in my mind because of Dan Kois. You see, we have Kois, an editor at Slate, to thank for this novel being published outside of Knox’s native New Zealand. He wrote an enthusiastic Slate review of an amazing novel he’d found that was only available through a small university press, and Clarke’s novel was his main point of reference. How’s that for the power of a book review?

Taryn Cornick, 33, has adapted her PhD thesis into a popular history of libraries – the search for absolute knowledge; the perennial threats that libraries face, from budget cuts to burnings – that she’s been discussing at literary festivals around the world. One particular burning looms large in her family’s history: the library at her grandfather’s country estate near the border of England and Wales, Princes Gate. As girls, Taryn and her older sister, Beatrice, helped to raise the alarm and saved the bulk of their grandfather’s collection. But one key artifact has been missing ever since: the Firestarter, an ancient scroll box that is said to have been through five fires and will survive another arson attempt before the book is through.

Nearly 15 years ago now, Beatrice was the victim of a random act of violence. Soon after her killer was released from prison, he turned up dead in unusual circumstances. Ever since, Detective Inspector Jacob Berger has suspected that Taryn arranged a revenge killing, but he has no proof. His cold case heats back up when Taryn lands in the hospital and complains of a series of prank calls.

What ensues is complicated, but in essence, the ongoing fallout of Beatrice’s murder and a cosmic battle over the Firestarter are twin forces that plunge Taryn and Jacob into the faerie realm (Sidh). Their guide to the Sidh is Shift, a shapeshifter who can create impromptu gates between the two worlds (while others, like Princes Gate, are permanent passageways).

Fairies (sidhe), demons, talking ravens … there’s some convoluted world-building here, and when I reached the end I realized I still had many ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions, though often this was because I hadn’t paid close enough attention and if I glanced back I’d see that Knox did indeed tell us how characters got from A to B, and who was after the Firestarter and why.

The book travels everywhere from Provence to Purgatory, but I particularly liked the descriptions of the primitive lifestyle in the faerie realm. Knox gives enough detail about things like food and clothing that you can really imagine yourself into each setting, and there’s the occasional funny turn of phrase that inserts the magical into everyday life in a tongue-in-cheek way, like “The Nespresso [machine] made hatching-dragon sounds.”

My two favorite scenes were an intense escape from a marsh and one that delightfully blends the human world and faerie: Taryn’s father, Basil Cornick, is a Kiwi actor best known for his role in a Game of Thrones-style television show. He’s roped into what he thinks is a screen test, playing Odin opposite a very convincing animatronic monster and pair of talking birds. We and Taryn know what he doesn’t: that he was used to negotiate with a real demon. The terrific epilogue also offers an appealing vision of how the sidhe might save the world.

If, like me, all you know of Knox’s previous work is the bizarre and kind of awful The Vintner’s Luck (which I read for a book club a decade or so ago), you’ll be intrigued to learn that angels play a role here, too. But beneath all the magical stuff, which is sometimes hard to follow or believe in, the novel is a hymn to language and libraries. A number of books are mentioned, starting with the one that was in Beatrice’s backpack at the time of her death: “the blockbuster of that year, 2003, a novel about tantalising, epoch-spanning conspiracies. Beatrice enjoyed those books, perhaps because they were often set in libraries.” (That’s The Da Vinci Code, of course.) Also mentioned: Labyrinth by Kate Mosse, the Moomin books, and the film Spirited Away – no doubt these were beloved influences for Knox.

I appreciated the words about libraries’ enduring value, even on a poisoned planet. “I want there to be libraries in the future. I want today to give up being so smugly sure about what tomorrow won’t need,” Taryn says. She knows that, for this to happen, people must “care about the transmission of knowledge from generation to generation, and about keeping what isn’t immediately necessary because it might be vital one day. Or simply intriguing, or beautiful.” That’s an analogy for species, too, I think, and a reminder of our responsibility: to preserve human accomplishments, yes, but also the more-than-human world (even if that ‘more’ might not include fairies).

Page count: 626 (my only 500+-page doorstopper so far this year!)

My rating:

Wigtown Book Festival 2020: The Bookshop Band, Bythell, O’Connell & Stuart

During the coronavirus pandemic, we have had to take small pleasures where we can. One of the highlights of lockdown for me has been the chance to participate in literary events like book-themed concerts, prize shortlist announcements, book club discussions, live literary award ceremonies and book festivals that time, distance and cost might otherwise have precluded.

In May I attended several digital Hay Festival events, and this September to early October I’ve been delighted to journey back to Wigtown, Scotland – even if only virtually.

The Bookshop Band

The Bookshop Band have been a constant for me this year. After watching their 21 Friday evening lockdown shows on Facebook, as well as a couple of one-off performances for other festivals, I have spent so much time with them in their living room that they feel more like family than a favorite band. Add to that four of the daily breakfast chat shows from the Wigtown Book Festival and I’ve seen them play over 25 times this year already!

(The still below shows them with, clockwise from bottom left, guests Emma Hooper, Stephen Rutt and Jason Webster.)

Ben and Beth’s conversations with featured authors and local movers and shakers, punctuated by one song per guest, were pleasant to have on in the background while working. The songs they performed were, ideally, written for those authors’ books, but other times just what seemed most relevant; at times this was a stretch! I especially liked seeing Donal Ryan, about whose The Spinning Heart they’ve recently written a terrific song; Kate Mosse, who has been unable to write during lockdown so (re)read 200 books instead, including all of Agatha Christie, Ngaio Marsh et al.; and Ned Beauman, who is nearing the deadline for his next novel, a near-future story of two scientists looking for traces of the venomous lumpsucker (a made-up fish) in the Baltic Sea. Closer to science fiction than his previous work, it’s a funny take on extinctions, he said. I’ve read all of his published work, so I’m looking forward to this one.

Shaun Bythell

The opening event of the Festival was an in-person chat between Lee Randall and Shaun Bythell in Wigtown, rather than the split-screen virtual meet-ups that made up the rest of my viewing. Bythell, owner of The Book Shop, has become Wigtown’s literary celebrity through The Diary of a Bookseller and its sequel. In early November he has a new book coming out, Seven Kinds of People You Find in Bookshops. I’m halfway through it and it has more substance than its stocking-stuffer dimensions would imply. Within his seven categories are multiple subcategories, all given tongue-in-cheek Latin names, as if he’s naming species.

The opening event of the Festival was an in-person chat between Lee Randall and Shaun Bythell in Wigtown, rather than the split-screen virtual meet-ups that made up the rest of my viewing. Bythell, owner of The Book Shop, has become Wigtown’s literary celebrity through The Diary of a Bookseller and its sequel. In early November he has a new book coming out, Seven Kinds of People You Find in Bookshops. I’m halfway through it and it has more substance than its stocking-stuffer dimensions would imply. Within his seven categories are multiple subcategories, all given tongue-in-cheek Latin names, as if he’s naming species.

The Book Shop closed for 116 days during COVID-19: the only time in more than 40 years that it has been closed for longer than just over the Christmas holidays. He said that it has been so nice to see customers again; they’ve been a ray of sunshine for him, something the curmudgeon would never usually say! Business has been booming since his reopening, with Agatha Christie his best seller – it’s not just Mosse who’s turning to cozy mysteries. He’s also been touched by the kindness of strangers, such as one from Monaco who sent him £300, having read an article by Margaret Atwood about how hard it is for small businesses just now and hoping it would help the shop survive until they could get there in person.

(Below: Bythell on his 50th birthday, with Captain the cat.)

Randall and Bythell discussed a few of the types of customers he regularly encounters. One is the autodidact, who knows more than you and intends for you to know it. This is not the same, though, as the expert who actually helps you by sharing their knowledge (of a rare cover version on an ordinary-looking crime paperback, for instance). There’s also the occultists, the erotica browsers, the local historians and the young families – now that he has one of his own, he’s become a bit more tolerant.

Mark O’Connell

Appearing from Dublin, Mark O’Connell was interviewed by Scottish writer and critic Stuart Kelly about his latest book, Notes from an Apocalypse (my review). He noted that, while all authors hope their books are timely, perhaps he overshot with this one! The book opens with climate change as the most immediate threat, yet now he feels that “has receded as the locus of anxiety.” O’Connell described the “flattened” experience of being alive at the moment and contrasted it with the existential awfulness of his research travels. For instance, he read a passage from the book about being at an airport Yo Sushi! chain and having a vision of horror at the rampant consumerism its conveyor belt seemed to represent.

Appearing from Dublin, Mark O’Connell was interviewed by Scottish writer and critic Stuart Kelly about his latest book, Notes from an Apocalypse (my review). He noted that, while all authors hope their books are timely, perhaps he overshot with this one! The book opens with climate change as the most immediate threat, yet now he feels that “has receded as the locus of anxiety.” O’Connell described the “flattened” experience of being alive at the moment and contrasted it with the existential awfulness of his research travels. For instance, he read a passage from the book about being at an airport Yo Sushi! chain and having a vision of horror at the rampant consumerism its conveyor belt seemed to represent.

Kelly characterized O’Connell’s personal, self-conscious approach to the end of the world as “brave,” while O’Connell said, “in terms of mental health, I should have chosen any other topic!” Having children creates both vulnerability and possibility, he contended, and “it doesn’t do you any good as a parent to indulge in those predilections [towards extreme pessimism].” They discussed preppers’ white male privilege, New Zealand and Mars as havens, and Greta Thunberg and David Attenborough as saints of the climate crisis.

O’Connell pinpointed Dr. Seuss’s The Lorax as the work he spends more time on in his book than any other; none of your classic nihilist literature here, and he deliberately avoided bringing up biblical references in his secular approach. In terms of the author he’s reached for most over the last few years, and especially during lockdown, it’s got to be Annie Dillard. Speaking of the human species, he opined, “it should not be unimaginable that we should cease to exist at some point.”

This talk didn’t add much to my experience of reading the book (vice versa would probably be true, too – I got the gist of Roman Krznaric’s recent thinking from his Hay Festival talk and so haven’t been engaging with his book as much as I’d like), but it was nice to see O’Connell ‘in person’ since he couldn’t make it to the 2018 Wellcome Book Prize ceremony.

Douglas Stuart

Glasgow-born Douglas Stuart is a fashion designer in New York City. Again the interviewer was Lee Randall, an American journalist based in Edinburgh – she joked that she and Stuart have swapped places. Stuart said he started writing his Booker-shortlisted novel, Shuggie Bain, 12 years ago, and kept it private for much of that time. Although he and Randall seemed keen to downplay how autobiographical the work is, like his title character, Stuart grew up in 1980s Glasgow with an alcoholic single mother. As a gay boy, he felt he didn’t have a voice in Thatcher’s Britain. He knew many strong women who were looked down on for being poor.

It’s impossible to write an apolitical book about poverty (or a Glasgow book without dialect), Stuart acknowledged, yet he insisted that the novel is primarily “a portrait of two souls moving through the world,” a love story about Shuggie and his mother, Agnes. The author read a passage from the start of Chapter 2, when readers first meet Agnes, the heart of the book. Randall asked about sex as currency and postulated that all Agnes – or any of these characters; or any of us, really – wants is someone whose face lights up when they see you.

It’s impossible to write an apolitical book about poverty (or a Glasgow book without dialect), Stuart acknowledged, yet he insisted that the novel is primarily “a portrait of two souls moving through the world,” a love story about Shuggie and his mother, Agnes. The author read a passage from the start of Chapter 2, when readers first meet Agnes, the heart of the book. Randall asked about sex as currency and postulated that all Agnes – or any of these characters; or any of us, really – wants is someone whose face lights up when they see you.

The name “Shuggie” was borrowed from a small-town criminal in his housing scheme; it struck him as ironic that a thug had such a sweet nickname. Stuart said that writing the book was healing for him. He thinks that men who drink and can’t escape poverty are often seen as loveable rogues, while women are condemned for how they fail their children. Through Agnes, he wanted to add some nuance to that double standard.

The draft of Shuggie Bain was 900 pages, single-spaced, but his editor helped him cut it while simultaneously drawing out the important backstories of Agnes and some other characters. He had almost finished his second novel by the time Shuggie was published, so he hopes it will be with readers soon.

[I have reluctantly DNFed Shuggie Bain at p. 100, but I’ll keep my proof copy on the shelf in case one day I feel like trying it again – especially if, as seems likely, it wins the Booker Prize.]

Phosphorescence by Julia Baird – An intriguing if somewhat scattered hybrid: a self-help memoir with nature themes. Many female-authored nature books I’ve read recently (Wintering, A Still Life, Rooted) have emphasized paying attention and courting a sense of wonder. To cope with recurring abdominal cancer, Baird turned to swimming at the Australian coast and to faith. Indeed, I was surprised by how deeply she delves into Christianity here. She was involved in the campaign for the ordination of women and supports LGBTQ rights.

Phosphorescence by Julia Baird – An intriguing if somewhat scattered hybrid: a self-help memoir with nature themes. Many female-authored nature books I’ve read recently (Wintering, A Still Life, Rooted) have emphasized paying attention and courting a sense of wonder. To cope with recurring abdominal cancer, Baird turned to swimming at the Australian coast and to faith. Indeed, I was surprised by how deeply she delves into Christianity here. She was involved in the campaign for the ordination of women and supports LGBTQ rights.

Open House by Elizabeth Berg – When her husband leaves, Sam goes off the rails in minor and amusing ways: accepting a rotating cast of housemates, taking temp jobs at a laundromat and in telesales, and getting back onto the dating scene. I didn’t find Sam’s voice as fresh and funny as Berg probably thought it is, but this is as readable as any Oprah’s Book Club selection and kept me entertained on the plane ride back from America and the car trip up to York. It’s about finding joy in the everyday and not defining yourself by your relationships.

Open House by Elizabeth Berg – When her husband leaves, Sam goes off the rails in minor and amusing ways: accepting a rotating cast of housemates, taking temp jobs at a laundromat and in telesales, and getting back onto the dating scene. I didn’t find Sam’s voice as fresh and funny as Berg probably thought it is, but this is as readable as any Oprah’s Book Club selection and kept me entertained on the plane ride back from America and the car trip up to York. It’s about finding joy in the everyday and not defining yourself by your relationships.  Site Fidelity by Claire Boyles – I have yet to review this for BookBrowse, but can briefly tell you that it’s a terrific linked short story collection set on the sagebrush steppe of Colorado and featuring several generations of strong women. Boyles explores environmental threats to the area, like fracking, polluted rivers and an endangered bird species, but never with a heavy hand. It’s a different picture than what we usually get of the American West, and the characters shine. The book reminded me most of Love Medicine by Louise Erdrich.

Site Fidelity by Claire Boyles – I have yet to review this for BookBrowse, but can briefly tell you that it’s a terrific linked short story collection set on the sagebrush steppe of Colorado and featuring several generations of strong women. Boyles explores environmental threats to the area, like fracking, polluted rivers and an endangered bird species, but never with a heavy hand. It’s a different picture than what we usually get of the American West, and the characters shine. The book reminded me most of Love Medicine by Louise Erdrich.

Every Minute Is a Day by Robert Meyer, MD and Dan Koeppel – The Bronx’s Montefiore Medical Center serves an ethnically diverse community of the working poor. Between March and September 2020, it had 6,000 Covid-19 patients cross the threshold. Nearly 1,000 of them would die. Unfolding in real time, this is an emergency room doctor’s diary as compiled from interviews and correspondence by his journalist cousin. (Coming out on August 3rd. Reviewed for Shelf Awareness.)

Every Minute Is a Day by Robert Meyer, MD and Dan Koeppel – The Bronx’s Montefiore Medical Center serves an ethnically diverse community of the working poor. Between March and September 2020, it had 6,000 Covid-19 patients cross the threshold. Nearly 1,000 of them would die. Unfolding in real time, this is an emergency room doctor’s diary as compiled from interviews and correspondence by his journalist cousin. (Coming out on August 3rd. Reviewed for Shelf Awareness.)

Virga by Shin Yu Pai – Yoga and Zen Buddhism are major elements in this tenth collection by a Chinese American poet based in Washington. She reflects on her family history and a friend’s death as well as the process of making art, such as a project of crafting 108 clay reliquary boxes. “The uncarved block,” a standout, contrasts the artist’s vision with the impossibility of perfection. The title refers to a weather phenomenon in which rain never reaches the ground because the air is too hot. (Coming out on August 1st.)

Virga by Shin Yu Pai – Yoga and Zen Buddhism are major elements in this tenth collection by a Chinese American poet based in Washington. She reflects on her family history and a friend’s death as well as the process of making art, such as a project of crafting 108 clay reliquary boxes. “The uncarved block,” a standout, contrasts the artist’s vision with the impossibility of perfection. The title refers to a weather phenomenon in which rain never reaches the ground because the air is too hot. (Coming out on August 1st.)  The Other Black Girl by Zakiya Dalila Harris – I feel like I’m the last person on Earth to read this buzzy book, so there’s no point recounting the plot, which initially is reminiscent of

The Other Black Girl by Zakiya Dalila Harris – I feel like I’m the last person on Earth to read this buzzy book, so there’s no point recounting the plot, which initially is reminiscent of  Heartstopper, Volume 1 by Alice Oseman – It’s well known at Truham boys’ school that Charlie is gay. Luckily, the bullying has stopped and the others accept him. Nick, who sits next to Charlie in homeroom, even invites him to join the rugby team. Charlie is smitten right away, but it takes longer for Nick, who’s only ever liked girls before, to sort out his feelings. This black-and-white YA graphic novel is pure sweetness, taking me right back to the days of high school crushes. I raced through and placed holds on the other three volumes.

Heartstopper, Volume 1 by Alice Oseman – It’s well known at Truham boys’ school that Charlie is gay. Luckily, the bullying has stopped and the others accept him. Nick, who sits next to Charlie in homeroom, even invites him to join the rugby team. Charlie is smitten right away, but it takes longer for Nick, who’s only ever liked girls before, to sort out his feelings. This black-and-white YA graphic novel is pure sweetness, taking me right back to the days of high school crushes. I raced through and placed holds on the other three volumes.  The Vacationers by Emma Straub – Perfect summer reading; perfect holiday reading. Like Jami Attenberg, Straub writes great dysfunctional family novels featuring characters so flawed and real you can’t help but love and laugh at them. Here, Franny and Jim Post borrow a friend’s home in Mallorca for two weeks, hoping sun and relaxation will temper the memory of Jim’s affair. Franny’s gay best friend and his husband, soon to adopt a baby, come along. Amid tennis lessons, swims and gourmet meals, secrets and resentment simmer.

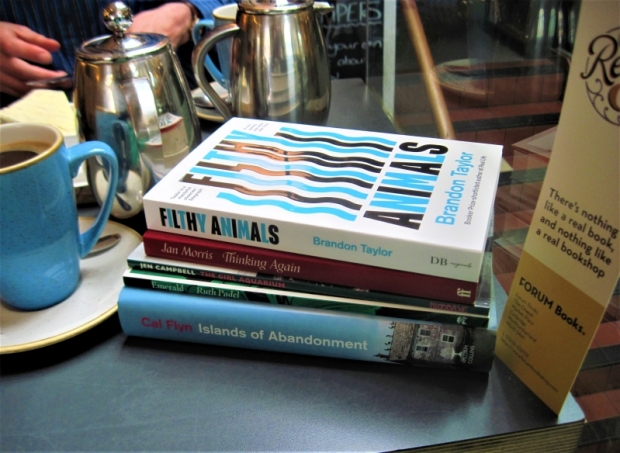

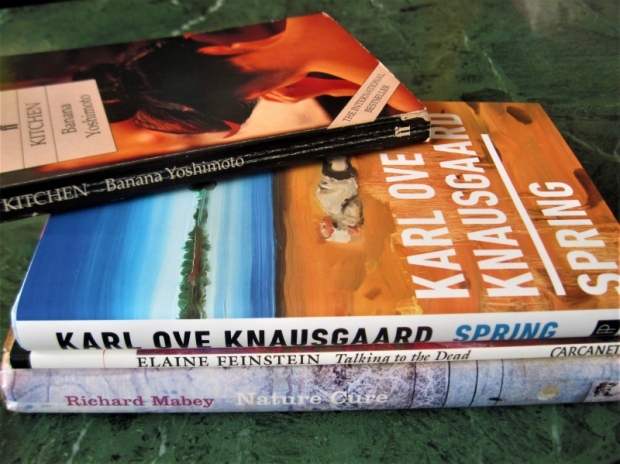

The Vacationers by Emma Straub – Perfect summer reading; perfect holiday reading. Like Jami Attenberg, Straub writes great dysfunctional family novels featuring characters so flawed and real you can’t help but love and laugh at them. Here, Franny and Jim Post borrow a friend’s home in Mallorca for two weeks, hoping sun and relaxation will temper the memory of Jim’s affair. Franny’s gay best friend and his husband, soon to adopt a baby, come along. Amid tennis lessons, swims and gourmet meals, secrets and resentment simmer.  Kitchen by Banana Yoshimoto – A pair of poignant stories of loss and what gets you through. In the title novella, after the death of the grandmother who raised her, Mikage takes refuge with her friend Yuichi and his mother (once father), Eriko, a trans woman who runs a nightclub. Mikage becomes obsessed with cooking: kitchens are her safe place and food her love language. Moonlight Shadow, half the length, repeats the bereavement theme but has a magic realist air as Satsuki meets someone who lets her see her dead boyfriend again.

Kitchen by Banana Yoshimoto – A pair of poignant stories of loss and what gets you through. In the title novella, after the death of the grandmother who raised her, Mikage takes refuge with her friend Yuichi and his mother (once father), Eriko, a trans woman who runs a nightclub. Mikage becomes obsessed with cooking: kitchens are her safe place and food her love language. Moonlight Shadow, half the length, repeats the bereavement theme but has a magic realist air as Satsuki meets someone who lets her see her dead boyfriend again.  This was my 11th book from Padel; I’ve read a mixture of her poetry, fiction, narrative nonfiction and poetry criticism. Emerald consists mostly of poems in memory of her mother, Hilda, who died in 2017 at the age of 97. The book pivots on her mother’s death, remembering the before (family stories, her little ways, moving her into sheltered accommodation when she was 91, sitting vigil at her deathbed) and the letdown of after. It made a good follow-on to one I reviewed last month, Kate Mosse’s

This was my 11th book from Padel; I’ve read a mixture of her poetry, fiction, narrative nonfiction and poetry criticism. Emerald consists mostly of poems in memory of her mother, Hilda, who died in 2017 at the age of 97. The book pivots on her mother’s death, remembering the before (family stories, her little ways, moving her into sheltered accommodation when she was 91, sitting vigil at her deathbed) and the letdown of after. It made a good follow-on to one I reviewed last month, Kate Mosse’s  Allen-Paisant, from Jamaica and now based in Leeds, describes walking in the forest as an act of “reclamation.” For people of colour whose ancestors were perhaps sent on forced marches, hiking may seem strange, purposeless (the subject of “Black Walking”). Back in Jamaica, the forest was a place of utility rather than recreation:

Allen-Paisant, from Jamaica and now based in Leeds, describes walking in the forest as an act of “reclamation.” For people of colour whose ancestors were perhaps sent on forced marches, hiking may seem strange, purposeless (the subject of “Black Walking”). Back in Jamaica, the forest was a place of utility rather than recreation: The emotional scope of the poems is broad: the author fondly remembers his brick-making ancestors and his honeymoon; he sombrely imagines the last moments of an old man dying in a hospital; he expresses guilt over accidentally dismembering an ant, yet divulges that he then destroyed the ants’ nest deliberately. There are even a couple of cheeky, carnal poems, one about a couple of teenagers he caught copulating in the street and one, “The Hottest Day of the Year,” about a longing for touch. “Matter,” in ABAB stanzas, is on the theme of racial justice by way of the Black Lives Matter movement.

The emotional scope of the poems is broad: the author fondly remembers his brick-making ancestors and his honeymoon; he sombrely imagines the last moments of an old man dying in a hospital; he expresses guilt over accidentally dismembering an ant, yet divulges that he then destroyed the ants’ nest deliberately. There are even a couple of cheeky, carnal poems, one about a couple of teenagers he caught copulating in the street and one, “The Hottest Day of the Year,” about a longing for touch. “Matter,” in ABAB stanzas, is on the theme of racial justice by way of the Black Lives Matter movement. What came through particularly clearly for me was the older generation’s determination to not be a burden: living through the Second World War gave them a sense of perspective, such that they mostly did not complain about their physical ailments and did not expect heroic measures to be made to help them. (Her father knew his condition was “becoming too much” to deal with, and Granny Rosie would sometimes say, “I’ve had enough of me.”) In her father’s case, this was because he held out hope of an afterlife. Although Mosse does not share his religious beliefs, she is glad that he had them as a comfort.

What came through particularly clearly for me was the older generation’s determination to not be a burden: living through the Second World War gave them a sense of perspective, such that they mostly did not complain about their physical ailments and did not expect heroic measures to be made to help them. (Her father knew his condition was “becoming too much” to deal with, and Granny Rosie would sometimes say, “I’ve had enough of me.”) In her father’s case, this was because he held out hope of an afterlife. Although Mosse does not share his religious beliefs, she is glad that he had them as a comfort.