Book Serendipity, Mid-October to Mid-December 2022

The last entry in this series for the year. Those of you who join me for Love Your Library, note that I’ll host it on the 19th this month to avoid the holidays. Other than that, I don’t know how many more posts I’ll fit in before my year-end coverage (about six posts of best-of lists and statistics). Maybe I’ll manage a few more backlog reviews and a thematic roundup.

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every few months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Tom Swifties (a punning joke involving the way a quotation is attributed) in Savage Tales by Tara Bergin (“We get a lot of writers in here, said the rollercoaster operator lowering the bar”) and one of the stories in Birds of America by Lorrie Moore (“Would you like a soda? he asked spritely”).

- Prince’s androgynous symbol was on the cover of Dickens and Prince by Nick Hornby and is mentioned in the opening pages of Shameless by Nadia Bolz-Weber.

- Clarence Thomas is mentioned in one story of Birds of America by Lorrie Moore and Encore by May Sarton. (A function of them both dating to the early 1990s!)

- A kerfuffle over a ring belonging to the dead in one story of Shoot the Horses First by Leah Angstman and Motherthing by Ainslie Hogarth.

- Excellent historical fiction with a 2023 release date in which the amputation of a woman’s leg is a threat or a reality: one story of Shoot the Horses First by Leah Angstman and The House Is on Fire by Rachel Beanland.

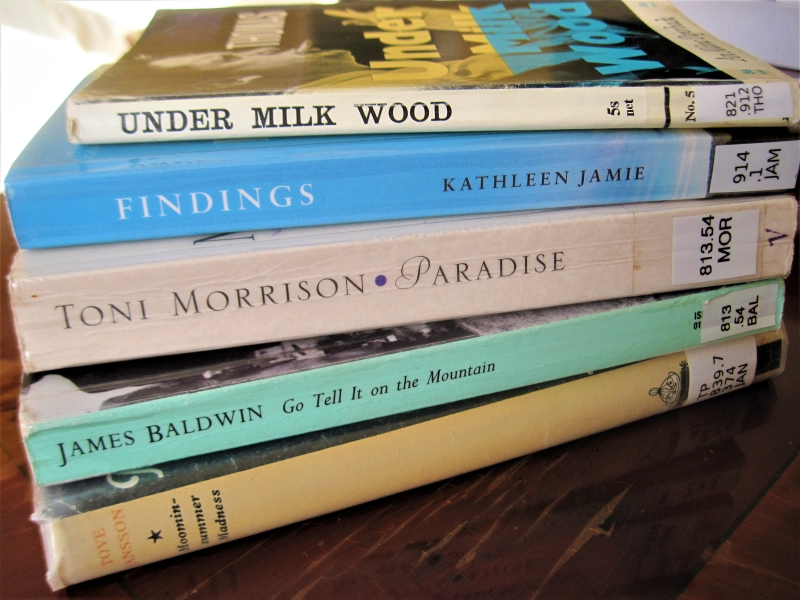

- More of a real-life coincidence, this one: I was looking into Paradise, Piece by Piece by Molly Peacock, a memoir I already had on my TBR, because of an Instagram post I’d read about books that were influential on a childfree woman. Then, later the same day, my inbox showed that Molly Peacock herself had contacted me through my blog’s contact form, offering a review copy of her latest book!

- Reading nonfiction books titled The Heart of Things (by Richard Holloway) and The Small Heart of Things (by Julian Hoffman) at the same time.

- A woman investigates her husband’s past breakdown for clues to his current mental health in The Fear Index by Robert Harris and Motherthing by Ainslie Hogarth.

- “Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow” is a repeated phrase in Another Brooklyn by Jacqueline Woodson, as it was in Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin.

- Massive, much-anticipated novel by respected author who doesn’t publish very often, and that changed names along the way: John Irving’s The Last Chairlift (2022) was originally “Darkness as a Bride” (a better title!); Abraham Verghese’s The Covenant of Water (2023) started off as “The Maramon Convention.” I plan to read the Verghese but have decided against the Irving.

- Looting and white flight in New York City in Feral City by Jeremiah Moss and Another Brooklyn by Jacqueline Woodson.

- Two bereavement memoirs about a loved one’s death from pancreatic cancer: Ti Amo by Hanne Ørstavik and Crying in H Mart by Michelle Zauner.

- The Owl and the Pussycat of Edward Lear’s poem turn up in an update poem by Margaret Atwood in her collection The Door and in Anna James’s fifth Pages & Co. book, The Treehouse Library.

- Two books in which the author draws security attention for close observation of living things on the ground: Where the Wildflowers Grow by Leif Bersweden and The Lichen Museum by A. Laurie Palmer.

- Seal and human motherhood are compared in Zig-Zag Boy by Tanya Frank and All of Us Together in the End by Matthew Vollmer, two 2023 memoirs I’m enjoying a lot.

- Mystical lights appear in Animal Life by Auður Ava Ólafsdóttir (the Northern Lights, there) and All of Us Together in the End by Matthew Vollmer.

- St Vitus Dance is mentioned in Zig-Zag Boy by Tanya Frank and Robin by Helen F. Wilson.

- The history of white supremacy as a deliberate project in Oregon was a major element in Heaven Is a Place on Earth by Adrian Shirk, which I read earlier in the year, and has now recurred in The Distance from Slaughter County by Steven Moore.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Margaret Atwood Reading Month: The Door (#MARM)

It’s my fifth year participating in the annual Margaret Atwood Reading Month (#MARM), hosted by indomitable Canadian blogger Marcie of Buried in Print. In previous years for this challenge, I’ve read Surfacing and The Edible Woman, The Robber Bride and Moral Disorder, and Wilderness Tips; and reread The Blind Assassin. Today is Atwood’s 83rd birthday, so what better time to show her some love?

Like the Beatles, she’s worked in so many different genres and styles that I don’t see how anyone could say they don’t like her – you just haven’t explored her oeuvre deeply enough. Although she’s best known for her fiction, she started off as a poet, with a whole five collections published in the 1960s before her first novel appeared. I’d previously read her Eating Fire: Selected Poetry 1965–1995 and Dearly, my top poetry read of 2020.

The Door (2007) was at that point her first poetry release in 12 years and features a number of the same themes that permeate her novels and nonfiction: memory, writing, ageing, travel and politics. I particularly like the early poems where she reinhabits memories of childhood and early adulthood, often through objects. Such artifacts are “pocketed as pure mementoes / of some once indelible day,” she writes in “Year of the Hen.”

The Door (2007) was at that point her first poetry release in 12 years and features a number of the same themes that permeate her novels and nonfiction: memory, writing, ageing, travel and politics. I particularly like the early poems where she reinhabits memories of childhood and early adulthood, often through objects. Such artifacts are “pocketed as pure mementoes / of some once indelible day,” she writes in “Year of the Hen.”

These are followed by a trilogy about the death of the family’s pet cat, Blackie. “We get too sentimental / over dead animals. / We turn maudlin,” she acknowledges in “Mourning for Cats,” yet “Blackie in Antarctica” injects some humour as she remembers how her sister kept the cat’s corpse in the freezer until she could come home to bury it. Also on the lighter side is a long “where are they now?” update for the Owl and the Pussycat.

There are also meta reflections on poetry, slightly menacing observations on the weather (an implacable, fate-like force) and the seasons (autumn = hunting), virtual visits to the Arctic, mild complaints about the elderly not being taken seriously, and thoughts on duty.

Four in a row muse about war – the Vietnam War in particular, I think? “The Last Rational Man” is a sinister standout, depicting a figure who is doomed under Caligula’s reign. Whoever she may have had in mind when she wrote this, it’s just as relevant 15 years later.

In the final, title poem, which appears to be modelled on the Seven Ages of Man, a door is a metaphor for life’s transitions and, ultimately, for death.

The door swings open:

O god of hinges,

god of long voyages,

you have kept faith.

It’s dark in there.

You confide yourself to the darkness.

You step in.

The door swings closed.

Apart from a few end rhymes, Atwood relies more on theme than on sonic technique or form. That, I think, makes her poetry accessible to those who are new to or suspicious of verse. Happy birthday, M.A., and thank you for your literary wisdom and innovation! (Little Free Library) ![]()

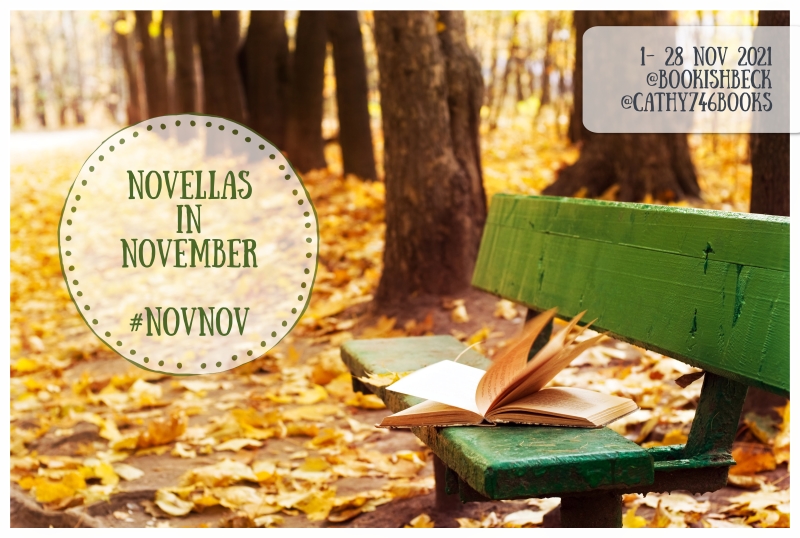

Novellas in November Wrap-Up

Last year, our first of hosting Novellas in November as an official blogger challenge, we had 89 posts by 30 bloggers. This year, Cathy and I have been simply blown away by the level of participation: as of this afternoon, our count is that 49 bloggers have taken part, publishing just over 200 posts and covering over 270 books. We’ve done our best to keep up with the posts, which we’ve each been collecting as links on the opening master post. (Here’s mine.)

Thank you all for being so engaged with #NovNov, including with the buddy reads we tried out for the first time this year. We’re already thinking about changes we might implement for next year.

A special mention goes to Simon of Stuck in a Book for being such a star supporter and managing to review a novella on most days of the month.

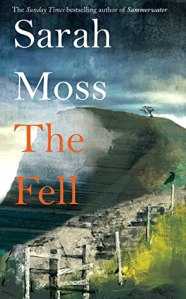

Our most reviewed books of the month included new releases (The Fell by Sarah Moss, Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan, Assembly by Natasha Brown, and The Writer’s Cats by Muriel Barbery), our four buddy reads, and The Cost of Living by Deborah Levy.

Our most reviewed books of the month included new releases (The Fell by Sarah Moss, Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan, Assembly by Natasha Brown, and The Writer’s Cats by Muriel Barbery), our four buddy reads, and The Cost of Living by Deborah Levy.

Some authors who were reviewed more than once (highlighting different works) were Margaret Atwood, Henry James, Elizabeth Jolley, Amos Oz, George Simenon, and Muriel Spark.

Of course, novellas are great to read the whole year round and not just in November, but we hope this has been a good excuse to pick up some short books and appreciate how much can be achieved with such a limited number of pages. If we missed any of your coverage, let us know and we will gladly add it in to the master list.

See you next year!

The Blind Assassin Reread for #MARM, and Other Doorstoppers

It’s the fourth annual Margaret Atwood Reading Month (#MARM), hosted by Canadian blogger extraordinaire Marcie of Buried in Print. In previous years, I’ve read Surfacing and The Edible Woman, The Robber Bride and Moral Disorder, and Wilderness Tips. This year Laila at Big Reading Life and I did a buddy reread of The Blind Assassin, which was historically my favourite Atwood novel. I’d picked up a free paperback the last time I was at The Book Thing of Baltimore. Below are some quick thoughts based on what I shared with Laila as I was reading.

The Blind Assassin (2000)

Winner of the Booker Prize and Hammett Prize; shortlisted for the Orange Prize

I must have first read this about 13 years ago. The only thing I remembered before I started my reread was that there is a science fiction book-within-the-book. I couldn’t recall anything else about the setup before I read in the blurb about the suspicious circumstances of Laura’s death in 1945. Indeed, the opening line, which deserves to be famous, is “Ten days after the war ended, my sister Laura drove a car off a bridge.”

I always love novels about sisters, and Iris is a terrific narrator. Now a cantankerous elderly woman, she takes us back through her family history: her father’s button factory and his clashes with organizing workers, her mother’s early death, and her enduring relationship with their housekeeper, Reenie. Iris and Laura met a young man named Alex Thomas, a war orphan with radical views, at the factory’s Labour Day picnic, and it was clear early on that Laura was smitten, while Iris went on to marry Richard Griffen, a nouveau riche industrialist.

Interspersed with Iris’s recollections are newspaper articles that give a sense that the Chase family might be cursed, and excerpts from The Blind Assassin, Laura’s posthumously published novel. Daring for its time in terms of both explicit content and literary form (e.g., no speech marks), it has a storyline rather similar to 1984, with an upper-crust woman having trysts with a working-class man in his squalid lodgings. During their time snatched together, he also tells her a story inspired by the pulp sci-fi of the time. I was less engaged by the story-within-the-story(-within-the-story) this time around compared to Iris’s current life and flashbacks.

In the back of my mind, I had a vague notion that there was a twist coming, and in my impatience to see if I was right I ended up skimming much of the second half of the novel. My hunch was proven correct, but I was disappointed with myself that I wasn’t able to enjoy the journey more a second time around. Overall, this didn’t wow me on a reread, but then again, I am less dazzled by literary “tricks” these days. At the sentence level, however, the writing was fantastic, including descriptions of places, seasons and characters’ psychology. It’s intriguing to think about whether we can ever truly know Laura given Iris’s guardianship of her literary legacy.

If you haven’t read this before, find a time when you can give it your full attention and sink right in. It’s so wise on family secrets and the workings of memory and celebrity, and the weaving in of storylines in preparation for the big reveal is masterful.

Some favourite passages:

“What fabrications they are, mothers. Scarecrows, wax dolls for us to stick pins into, crude diagrams. We deny them an existence of their own, we make them up to suit ourselves – our own hungers, our own wishes, our own deficiencies.”

“Beginnings are sudden, but also insidious. They creep up on you sideways, they keep to the shadows, they lurk unrecognized. Then, later, they spring.”

“The only way you can write the truth is to assume that what you set down will never be read. Not by any other person, and not even by yourself at some later date. Otherwise you begin excusing yourself. You must see the writing as emerging like a long scroll of ink from the index finger of your right hand; you must see your left hand erasing it. Impossible, of course.”

My original rating (c. 2008): ![]()

My rating now: ![]()

What to read for #MARM next year, I wonder??

In general, I have been struggling mightily with doorstoppers this year. I just don’t seem to have the necessary concentration, so Novellas in November has been a boon. I’ve been battling with Ruth Ozeki’s latest novel for months, and another attempted buddy read of 460 pages has also gone by the wayside. I’ll write a bit more on this for #LoveYourLibrary on Monday, including a couple of recent DNFs. The Blind Assassin was only my third successful doorstopper of the year so far. After The Absolute Book, the other one was:

The Lincoln Highway by Amor Towles

In Towles’ third novel – a big, old-fashioned dose of Americana – brothers and pals set out from Nebraska on road and rail adventures to find a fortune in 1950s New York. The book features some fantastic characters. Precocious Billy steals every scene he appears in. Duchess is a delightfully flamboyant bounder, peppering his speech with malapropisms and Shakespeare quotes. However, Emmett is a dull protagonist, and it’s disappointing that Sally, one of just two main female characters, plays such a minor role. A danger with an episodic narrative is that random events and encounters pile up but don’t do much to further the plot. At nearly 200 pages in, I realized little of consequence had happened yet. A long road, then, with some ups and downs along the way, but Towles’ fans will certainly want to sign up for the ride.

In Towles’ third novel – a big, old-fashioned dose of Americana – brothers and pals set out from Nebraska on road and rail adventures to find a fortune in 1950s New York. The book features some fantastic characters. Precocious Billy steals every scene he appears in. Duchess is a delightfully flamboyant bounder, peppering his speech with malapropisms and Shakespeare quotes. However, Emmett is a dull protagonist, and it’s disappointing that Sally, one of just two main female characters, plays such a minor role. A danger with an episodic narrative is that random events and encounters pile up but don’t do much to further the plot. At nearly 200 pages in, I realized little of consequence had happened yet. A long road, then, with some ups and downs along the way, but Towles’ fans will certainly want to sign up for the ride. ![]()

See my full review for BookBrowse; see also my related article on Studebaker cars.

With thanks to Hutchinson for the free copy for review.

Anything by Atwood, or any doorstoppers, on your pile recently?

Talking to the Dead x 2: Helen Dunmore and Elaine Feinstein

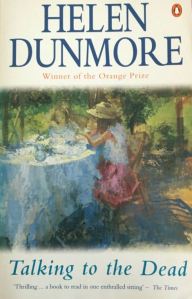

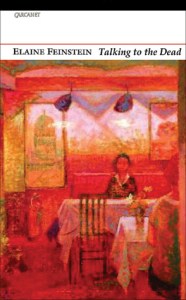

My fourth title-based dual review post this year (after Ex Libris, The Still Point and How Not to Be Afraid), with Betty vs. Bettyville to come in December if I can manage them both. Today I have an early Helen Dunmore novel about the secrets binding a pair of sisters and an Elaine Feinstein poetry collection written after the loss of her husband. Their shared title seemed appropriate as Halloween approaches. Both: ![]()

Talking to the Dead by Helen Dunmore (1996)

Nina, a photographer, has travelled to stay with her sister in Sussex after the birth of Isabel’s first child, Antony. A house full of visitors, surrounded by an unruly garden, is perfect for concealment. A current secret trades off with one from deep in the sisters’ childhood: their baby brother Colin’s death, which they remember differently. Antony and Colin function like doubles, with the sisters in subtle competition for ownership of the past and present. This was a delicious read: as close as literary fiction gets to a psychological thriller, dripping with sultry summer atmosphere and the symbols of aphrodisiac foods and blowsy flowers. From the novel’s title and opening pages, you have an inkling of what’s to come, but it still hits hard when it does. Impossible to say more about the plot without spoiling it, so just know that it’s a suspenseful story of sisters with Tessa Hadley, Maggie O’Farrell and Polly Samson vibes. I hadn’t much enjoyed my first taste of Dunmore’s fiction (Exposure), but I’m very glad that Susan’s enthusiasm spurred me to pick this up. (Secondhand purchase, Honesty bookshop outside the Castle, Hay-on-Wye)

Nina, a photographer, has travelled to stay with her sister in Sussex after the birth of Isabel’s first child, Antony. A house full of visitors, surrounded by an unruly garden, is perfect for concealment. A current secret trades off with one from deep in the sisters’ childhood: their baby brother Colin’s death, which they remember differently. Antony and Colin function like doubles, with the sisters in subtle competition for ownership of the past and present. This was a delicious read: as close as literary fiction gets to a psychological thriller, dripping with sultry summer atmosphere and the symbols of aphrodisiac foods and blowsy flowers. From the novel’s title and opening pages, you have an inkling of what’s to come, but it still hits hard when it does. Impossible to say more about the plot without spoiling it, so just know that it’s a suspenseful story of sisters with Tessa Hadley, Maggie O’Farrell and Polly Samson vibes. I hadn’t much enjoyed my first taste of Dunmore’s fiction (Exposure), but I’m very glad that Susan’s enthusiasm spurred me to pick this up. (Secondhand purchase, Honesty bookshop outside the Castle, Hay-on-Wye)

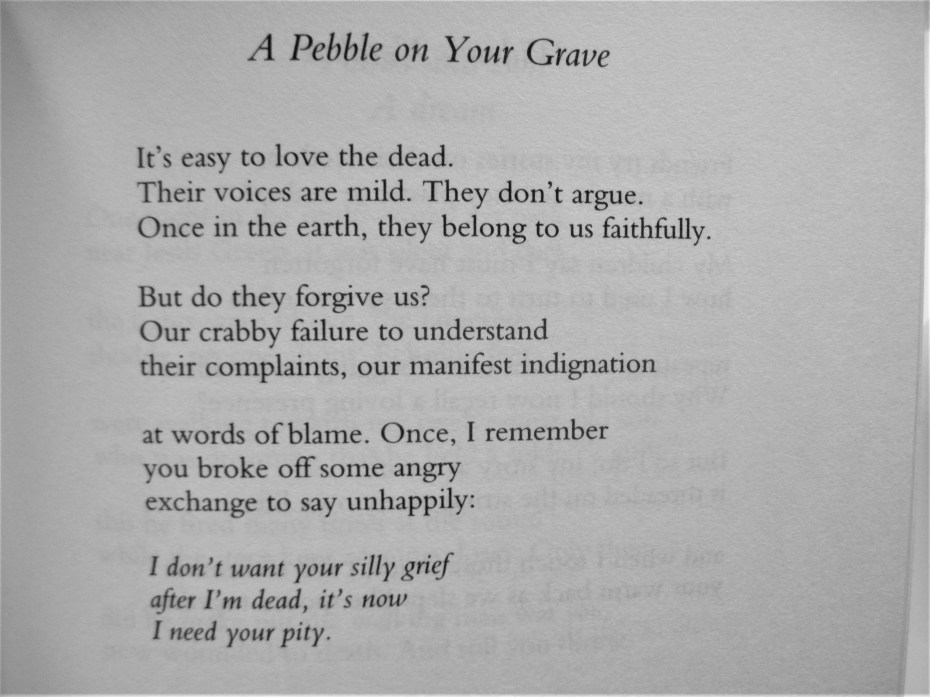

Talking to the Dead by Elaine Feinstein (2007)

Much like Margaret Atwood’s Dearly, my top poetry release of last year, this is a tender and playful response to a beloved spouse’s death. The short verses are in stanzas and incorporate the occasional end rhyme and spot of alliteration as Feinstein marshals images and memories to recreate her husband’s funeral and moments from their marriage and travels beforehand and her widowhood afterwards – including moving out of their shared home. The poems flow so easily and beautifully from one to another; I’d happily read much more from Feinstein. This was her 13th poetry collection; before her death in 2019, she also wrote many novels, stories, biographies and translations. I’ll leave you with a poem suitable for the run-up to the Day of the Dead. (Secondhand purchase, Minster Gate Bookshop, York)

Much like Margaret Atwood’s Dearly, my top poetry release of last year, this is a tender and playful response to a beloved spouse’s death. The short verses are in stanzas and incorporate the occasional end rhyme and spot of alliteration as Feinstein marshals images and memories to recreate her husband’s funeral and moments from their marriage and travels beforehand and her widowhood afterwards – including moving out of their shared home. The poems flow so easily and beautifully from one to another; I’d happily read much more from Feinstein. This was her 13th poetry collection; before her death in 2019, she also wrote many novels, stories, biographies and translations. I’ll leave you with a poem suitable for the run-up to the Day of the Dead. (Secondhand purchase, Minster Gate Bookshop, York)

As I was reading What We Talk about when We Talk about Love by Raymond Carver, I encountered a snippet from his poetry as a chapter epigraph in Bittersweet by Susan Cain.

As I was reading What We Talk about when We Talk about Love by Raymond Carver, I encountered a snippet from his poetry as a chapter epigraph in Bittersweet by Susan Cain.

The End of Drum-Time by Hanna Pylväinen [Jan. 24, Henry Holt and Co.] I loved Pylväinen’s 2012 debut, We Sinners. This sounds like a winning combination of The Bell in the Lake and The Mercies. “A richly atmospheric saga that charts the repercussions of a scandalous nineteenth century love affair between a young Sámi reindeer herder in the Arctic Circle and the daughter of the renegade Lutheran minister whose teachings are upending the Sámi way of life.” (Edelweiss download)

The End of Drum-Time by Hanna Pylväinen [Jan. 24, Henry Holt and Co.] I loved Pylväinen’s 2012 debut, We Sinners. This sounds like a winning combination of The Bell in the Lake and The Mercies. “A richly atmospheric saga that charts the repercussions of a scandalous nineteenth century love affair between a young Sámi reindeer herder in the Arctic Circle and the daughter of the renegade Lutheran minister whose teachings are upending the Sámi way of life.” (Edelweiss download) I Have Some Questions for You by Rebecca Makkai [Feb. 21, Viking / Feb. 23, Fleet] Makkai has written a couple of stellar novels; this sounds quite different from her usual lit fic but promises Secret History vibes. “A fortysomething podcaster and mother of two, Bodie Kane is content to forget her past [, including] the murder of one of her high school classmates, Thalia Keith. … [But] when she’s invited back to Granby, the elite New England boarding school where she spent four largely miserable years, to teach a course, Bodie finds herself inexorably drawn to the case and its increasingly apparent flaws.” (Proof copy)

I Have Some Questions for You by Rebecca Makkai [Feb. 21, Viking / Feb. 23, Fleet] Makkai has written a couple of stellar novels; this sounds quite different from her usual lit fic but promises Secret History vibes. “A fortysomething podcaster and mother of two, Bodie Kane is content to forget her past [, including] the murder of one of her high school classmates, Thalia Keith. … [But] when she’s invited back to Granby, the elite New England boarding school where she spent four largely miserable years, to teach a course, Bodie finds herself inexorably drawn to the case and its increasingly apparent flaws.” (Proof copy) Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton [March 7, Granta / Farrar, Straus and Giroux] I was lukewarm on The Luminaries (my most popular

Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton [March 7, Granta / Farrar, Straus and Giroux] I was lukewarm on The Luminaries (my most popular  Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld [April 4, Random House / April 6, Doubleday] Sittenfeld is one of my favourite contemporary novelists. “Sally Milz is a sketch writer for The Night Owls, the late-night live comedy show that airs each Saturday. … Enter Noah Brewster, a pop music sensation with a reputation for dating models, who signed on as both host and musical guest for this week’s show. … Sittenfeld explores the neurosis-inducing and heart-fluttering wonder of love, while slyly dissecting the social rituals of romance and gender relations in the modern age.”

Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld [April 4, Random House / April 6, Doubleday] Sittenfeld is one of my favourite contemporary novelists. “Sally Milz is a sketch writer for The Night Owls, the late-night live comedy show that airs each Saturday. … Enter Noah Brewster, a pop music sensation with a reputation for dating models, who signed on as both host and musical guest for this week’s show. … Sittenfeld explores the neurosis-inducing and heart-fluttering wonder of love, while slyly dissecting the social rituals of romance and gender relations in the modern age.” The Last Animal by Ramona Ausubel [April 18, Riverhead] “Jane is … on the cutting-edge team of a bold project looking to ‘de-extinct’ the woolly mammoth. … As Jane and her daughters ping-pong from the slopes of Siberia to a university in California, from the shores of Iceland to an exotic animal farm in Italy, The Last Animal takes readers on an expansive, bighearted journey that explores the possibility and peril of the human imagination on a changing planet, what it’s like to be a woman and a mother in a field dominated by men, and how a wondrous discovery can best be enjoyed with family. Even teenagers.”

The Last Animal by Ramona Ausubel [April 18, Riverhead] “Jane is … on the cutting-edge team of a bold project looking to ‘de-extinct’ the woolly mammoth. … As Jane and her daughters ping-pong from the slopes of Siberia to a university in California, from the shores of Iceland to an exotic animal farm in Italy, The Last Animal takes readers on an expansive, bighearted journey that explores the possibility and peril of the human imagination on a changing planet, what it’s like to be a woman and a mother in a field dominated by men, and how a wondrous discovery can best be enjoyed with family. Even teenagers.” Saturday Night at the Lakeside Supper Club by J. Ryan Stradal [April 18, Pamela Dorman Books] Kitchens of the Great Midwest is one of my all-time favourite debuts. A repeat from my

Saturday Night at the Lakeside Supper Club by J. Ryan Stradal [April 18, Pamela Dorman Books] Kitchens of the Great Midwest is one of my all-time favourite debuts. A repeat from my  The Memory of Animals by Claire Fuller [April 20, Fig Tree (Penguin) / June 6, Tin House] Fuller is another of my favourite contemporary novelists and never disappoints. “Neffy is a young woman running away from grief and guilt … When she answers the call to volunteer in a controlled vaccine trial, it offers her a way to pay off her many debts … [and] she is introduced to a pioneering and controversial technology which allows her to revisit memories from her life before.” And apparently there’s also an octopus? (NetGalley download)

The Memory of Animals by Claire Fuller [April 20, Fig Tree (Penguin) / June 6, Tin House] Fuller is another of my favourite contemporary novelists and never disappoints. “Neffy is a young woman running away from grief and guilt … When she answers the call to volunteer in a controlled vaccine trial, it offers her a way to pay off her many debts … [and] she is introduced to a pioneering and controversial technology which allows her to revisit memories from her life before.” And apparently there’s also an octopus? (NetGalley download) The Late Americans by Brandon Taylor [May 23, Riverhead / June 22, Jonathan Cape (Penguin)] “In the shared and private spaces of Iowa City, a loose circle of lovers and friends encounter, confront, and provoke one another in a volatile year of self-discovery. … These three [main characters] are buffeted by a cast of poets, artists, landlords, meat-packing workers, and mathematicians who populate the cafes, classrooms, and food-service kitchens … [T]he group heads to a cabin to bid goodbye to their former lives—a moment of reckoning that leaves each of them irrevocably altered.” (Proof copy)

The Late Americans by Brandon Taylor [May 23, Riverhead / June 22, Jonathan Cape (Penguin)] “In the shared and private spaces of Iowa City, a loose circle of lovers and friends encounter, confront, and provoke one another in a volatile year of self-discovery. … These three [main characters] are buffeted by a cast of poets, artists, landlords, meat-packing workers, and mathematicians who populate the cafes, classrooms, and food-service kitchens … [T]he group heads to a cabin to bid goodbye to their former lives—a moment of reckoning that leaves each of them irrevocably altered.” (Proof copy) I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home by Lorrie Moore [June 20, Faber / Knopf] What a title! I’m keen to read more from Moore after her Birds of America got a 5-star rating from me late last year. “Finn is in the grip of middle-age and on an enforced break from work: it might be that he’s too emotional to teach history now. He is living in an America hurtling headlong into hysteria, after all. High up in a New York City hospice, he sits with his beloved brother Max, who is slipping from one world into the next. But when a phone call summons Finn back to a troubled old flame, a strange journey begins, opening a trapdoor in reality.”

I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home by Lorrie Moore [June 20, Faber / Knopf] What a title! I’m keen to read more from Moore after her Birds of America got a 5-star rating from me late last year. “Finn is in the grip of middle-age and on an enforced break from work: it might be that he’s too emotional to teach history now. He is living in an America hurtling headlong into hysteria, after all. High up in a New York City hospice, he sits with his beloved brother Max, who is slipping from one world into the next. But when a phone call summons Finn back to a troubled old flame, a strange journey begins, opening a trapdoor in reality.” A Manual for How to Love Us by Erin Slaughter [July 5, Harper Collins] “A debut, interlinked collection of stories exploring the primal nature of women’s grief. … Slaughter shatters the stereotype of the soft-spoken, sorrowful woman in distress, queering the domestic and honoring the feral in all of us. … Seamlessly shifting between the speculative and the blindingly real. … Set across oft-overlooked towns in the American South.” Linked short stories are irresistible for me, and I like the idea of a focus on grief.

A Manual for How to Love Us by Erin Slaughter [July 5, Harper Collins] “A debut, interlinked collection of stories exploring the primal nature of women’s grief. … Slaughter shatters the stereotype of the soft-spoken, sorrowful woman in distress, queering the domestic and honoring the feral in all of us. … Seamlessly shifting between the speculative and the blindingly real. … Set across oft-overlooked towns in the American South.” Linked short stories are irresistible for me, and I like the idea of a focus on grief. Learned by Heart by Emma Donoghue [Aug. 24, Pan Macmillan / Aug. 29, Little, Brown] Donoghue’s contemporary settings have been a little more successful for me, but she’s still a reliable author whose career I am happy to follow. “Drawing on years of investigation and Anne Lister’s five-million-word secret journal, … the long-buried love story of Eliza Raine, an orphan heiress banished from India to England at age six, and Anne Lister, a brilliant, troublesome tomboy, who meet at the Manor School for young ladies in York in 1805 … Emotionally intense, psychologically compelling, and deeply researched”.

Learned by Heart by Emma Donoghue [Aug. 24, Pan Macmillan / Aug. 29, Little, Brown] Donoghue’s contemporary settings have been a little more successful for me, but she’s still a reliable author whose career I am happy to follow. “Drawing on years of investigation and Anne Lister’s five-million-word secret journal, … the long-buried love story of Eliza Raine, an orphan heiress banished from India to England at age six, and Anne Lister, a brilliant, troublesome tomboy, who meet at the Manor School for young ladies in York in 1805 … Emotionally intense, psychologically compelling, and deeply researched”. The Year of the Cat: A Love Story by Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett [Jan. 19, Tinder Press] “When Rhiannon fell in love with, and eventually married her flatmate, she imagined they might one day move on. … The desire for a baby is never far from the surface, but … after a childhood spent caring for her autistic brother, does she really want to devote herself to motherhood? Moving through the seasons over the course of lockdown, [this] nimbly charts the way a kitten called Mackerel walked into Rhiannon’s home and heart, and taught her to face down her fears and appreciate quite how much love she had to offer.”

The Year of the Cat: A Love Story by Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett [Jan. 19, Tinder Press] “When Rhiannon fell in love with, and eventually married her flatmate, she imagined they might one day move on. … The desire for a baby is never far from the surface, but … after a childhood spent caring for her autistic brother, does she really want to devote herself to motherhood? Moving through the seasons over the course of lockdown, [this] nimbly charts the way a kitten called Mackerel walked into Rhiannon’s home and heart, and taught her to face down her fears and appreciate quite how much love she had to offer.” Fieldwork: A Forager’s Memoir by Iliana Regan [Jan. 24, Blackstone] “As Regan explores the ancient landscape of Michigan’s boreal forest, her stories of the land, its creatures, and its dazzling profusion of plant and vegetable life are interspersed with her and Anna’s efforts to make a home and a business of an inn that’s suddenly, as of their first full season there in 2020, empty of guests due to the COVID-19 pandemic. … Along the way she struggles … with her personal and familial legacies of addiction, violence, fear, and obsession—all while she tries to conceive a child that she and her immune-compromised wife hope to raise in their new home.” (Edelweiss download)

Fieldwork: A Forager’s Memoir by Iliana Regan [Jan. 24, Blackstone] “As Regan explores the ancient landscape of Michigan’s boreal forest, her stories of the land, its creatures, and its dazzling profusion of plant and vegetable life are interspersed with her and Anna’s efforts to make a home and a business of an inn that’s suddenly, as of their first full season there in 2020, empty of guests due to the COVID-19 pandemic. … Along the way she struggles … with her personal and familial legacies of addiction, violence, fear, and obsession—all while she tries to conceive a child that she and her immune-compromised wife hope to raise in their new home.” (Edelweiss download) Enchantment: Reawakening Wonder in an Exhausted Age by Katherine May [Feb. 28, Riverhead / March 9, Faber] I was a fan of her previous book, Wintering. “After years of pandemic life—parenting while working, battling anxiety about things beyond her control, feeling overwhelmed by the news-cycle and increasingly isolated—Katherine May feels bone-tired, on edge and depleted. Could there be another way to live? One that would allow her to feel less fraught and more connected, more rested and at ease, even as seismic changes unfold on the planet? Craving a different path, May begins to explore the restorative properties of the natural world”. (Proof copy)

Enchantment: Reawakening Wonder in an Exhausted Age by Katherine May [Feb. 28, Riverhead / March 9, Faber] I was a fan of her previous book, Wintering. “After years of pandemic life—parenting while working, battling anxiety about things beyond her control, feeling overwhelmed by the news-cycle and increasingly isolated—Katherine May feels bone-tired, on edge and depleted. Could there be another way to live? One that would allow her to feel less fraught and more connected, more rested and at ease, even as seismic changes unfold on the planet? Craving a different path, May begins to explore the restorative properties of the natural world”. (Proof copy) Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma by Claire Dederer [April 25, Knopf / May 25, Sceptre] “What do we do with the art of monstrous men? Can we love the work of Roman Polanski and Michael Jackson, Hemingway and Picasso? Should we love it? Does genius deserve special dispensation? Is history an excuse? What makes women artists monstrous? And what should we do with beauty, and with our unruly feelings about it? Dederer explores these questions and our relationships with the artists whose behaviour disrupts our ability to apprehend the work on its own terms. She interrogates her own responses and her own behaviour, and she pushes the fan, and the reader, to do the same.”

Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma by Claire Dederer [April 25, Knopf / May 25, Sceptre] “What do we do with the art of monstrous men? Can we love the work of Roman Polanski and Michael Jackson, Hemingway and Picasso? Should we love it? Does genius deserve special dispensation? Is history an excuse? What makes women artists monstrous? And what should we do with beauty, and with our unruly feelings about it? Dederer explores these questions and our relationships with the artists whose behaviour disrupts our ability to apprehend the work on its own terms. She interrogates her own responses and her own behaviour, and she pushes the fan, and the reader, to do the same.” Undercurrent: A Cornish Memoir of Poverty, Nature and Resilience by Natasha Carthew [May 25, Hodder Studio] Carthew hangs around the fringes of UK nature writing, mostly considering the plight of the working class. “Carthew grew up in rural poverty in Cornwall, battling limited opportunities, precarious resources, escalating property prices, isolation and a community marked by the ravages of inequality. Her world existed alongside the postcard picture Cornwall … part-memoir, part-investigation, part love-letter to Cornwall. … This is a journey through place, and a story of hope, beauty, and fierce resilience.”

Undercurrent: A Cornish Memoir of Poverty, Nature and Resilience by Natasha Carthew [May 25, Hodder Studio] Carthew hangs around the fringes of UK nature writing, mostly considering the plight of the working class. “Carthew grew up in rural poverty in Cornwall, battling limited opportunities, precarious resources, escalating property prices, isolation and a community marked by the ravages of inequality. Her world existed alongside the postcard picture Cornwall … part-memoir, part-investigation, part love-letter to Cornwall. … This is a journey through place, and a story of hope, beauty, and fierce resilience.”

Our joint highest rating, and one of our best discussions – taking in mental illness and its diagnosis and treatment, marriage, childlessness, alcoholism, sisterhood, creativity, neglect, unreliable narrators and loneliness. For several of us, these issues hit close to home due to personal or family experience. We particularly noted the way that Mason sets up parallels between pairs of characters, accurately reflecting how family dynamics can be replicated in later generations.

Our joint highest rating, and one of our best discussions – taking in mental illness and its diagnosis and treatment, marriage, childlessness, alcoholism, sisterhood, creativity, neglect, unreliable narrators and loneliness. For several of us, these issues hit close to home due to personal or family experience. We particularly noted the way that Mason sets up parallels between pairs of characters, accurately reflecting how family dynamics can be replicated in later generations.

In a fragmentary work of autobiography and cultural commentary, the Mexican author investigates pregnancy as both physical reality and liminal state. The linea nigra is a stripe of dark hair down a pregnant woman’s belly. It’s a potent metaphor for the author’s matriarchal line: her grandmother was a doula; her mother is a painter. In short passages that dart between topics, Barrera muses on motherhood, monitors her health, and recounts her dreams. Her son, Silvestre, is born halfway through the book. She gives impressionistic memories of the delivery and chronicles her attempts to write while someone else watches the baby. This is both diary and philosophical appeal—for pregnancy and motherhood to become subjects for serious literature. (See my full review for

In a fragmentary work of autobiography and cultural commentary, the Mexican author investigates pregnancy as both physical reality and liminal state. The linea nigra is a stripe of dark hair down a pregnant woman’s belly. It’s a potent metaphor for the author’s matriarchal line: her grandmother was a doula; her mother is a painter. In short passages that dart between topics, Barrera muses on motherhood, monitors her health, and recounts her dreams. Her son, Silvestre, is born halfway through the book. She gives impressionistic memories of the delivery and chronicles her attempts to write while someone else watches the baby. This is both diary and philosophical appeal—for pregnancy and motherhood to become subjects for serious literature. (See my full review for  It so happens that May is Maternal Mental Health Awareness Month. Cornwell comes from a deeply literary family; the late John le Carré was her grandfather. Her memoir shimmers with visceral memories of delivering her twin sons in 2018 and the postnatal depression and infections that followed. The details, precise and haunting, twine around a historical collage of words from other writers on motherhood and mental illness, ranging from Margery Kempe to Natalia Ginzburg. Childbirth caused other traumatic experiences from her past to resurface. How to cope? For Cornwell, therapy and writing went hand in hand. This is vivid and resolute, and perfect for readers of Catherine Cho, Sinéad Gleeson and Maggie O’Farrell. (See my full review for

It so happens that May is Maternal Mental Health Awareness Month. Cornwell comes from a deeply literary family; the late John le Carré was her grandfather. Her memoir shimmers with visceral memories of delivering her twin sons in 2018 and the postnatal depression and infections that followed. The details, precise and haunting, twine around a historical collage of words from other writers on motherhood and mental illness, ranging from Margery Kempe to Natalia Ginzburg. Childbirth caused other traumatic experiences from her past to resurface. How to cope? For Cornwell, therapy and writing went hand in hand. This is vivid and resolute, and perfect for readers of Catherine Cho, Sinéad Gleeson and Maggie O’Farrell. (See my full review for  Jones’s fourth work of fiction contains 11 riveting stories of contemporary life in the American South and Midwest. Some have pandemic settings and others are gently magical; all are true to the anxieties of modern careers, marriage and parenthood. In the title story, the narrator, a harried mother and business school student in Kentucky, seeks to balance the opposing forces of her life and wonders what she might have to sacrifice. The ending elicits a gasp, as does the audacious inconclusiveness of “Exhaust,” a tense tale of a quarreling couple driving through a blizzard. Worry over environmental crises fuels “Ark,” about a pyramid scheme for doomsday preppers. Fans of Nickolas Butler and Lorrie Moore will find much to admire. (Read via Edelweiss. See my full review for

Jones’s fourth work of fiction contains 11 riveting stories of contemporary life in the American South and Midwest. Some have pandemic settings and others are gently magical; all are true to the anxieties of modern careers, marriage and parenthood. In the title story, the narrator, a harried mother and business school student in Kentucky, seeks to balance the opposing forces of her life and wonders what she might have to sacrifice. The ending elicits a gasp, as does the audacious inconclusiveness of “Exhaust,” a tense tale of a quarreling couple driving through a blizzard. Worry over environmental crises fuels “Ark,” about a pyramid scheme for doomsday preppers. Fans of Nickolas Butler and Lorrie Moore will find much to admire. (Read via Edelweiss. See my full review for  Having read Ruhl’s memoir

Having read Ruhl’s memoir  The Jasper & Scruff series by Nicola Colton: Having insisted I don’t like

The Jasper & Scruff series by Nicola Colton: Having insisted I don’t like  The Decameron Project: 29 New Stories from the Pandemic (originally published in The New York Times): Creative responses to Covid-19, ranging from the prosaic to the fantastical. I appreciated the mix of authors, some in translation and some closer to genre fiction than lit fic. Standouts were by Victor LaValle (NYC apartment neighbours; magic realism), Colm Tóibín (lockdown prompts a man to consider his compatibility with his boyfriend), Karen Russell (time stops during a bus journey), Rivers Solomon (an abused girl and her imprisoned mother get revenge), Matthew Baker (a feuding grandmother and granddaughter find something to agree on), and John Wray (a relationship starts up during quarantine in Barcelona). The best story of all, though, was by Margaret Atwood.

The Decameron Project: 29 New Stories from the Pandemic (originally published in The New York Times): Creative responses to Covid-19, ranging from the prosaic to the fantastical. I appreciated the mix of authors, some in translation and some closer to genre fiction than lit fic. Standouts were by Victor LaValle (NYC apartment neighbours; magic realism), Colm Tóibín (lockdown prompts a man to consider his compatibility with his boyfriend), Karen Russell (time stops during a bus journey), Rivers Solomon (an abused girl and her imprisoned mother get revenge), Matthew Baker (a feuding grandmother and granddaughter find something to agree on), and John Wray (a relationship starts up during quarantine in Barcelona). The best story of all, though, was by Margaret Atwood.  Allegorizings by Jan Morris: Disparate, somewhat frivolous essays written mostly pre-2009, or in 2013, and kept in trust by her publisher for publication as a posthumous collection, so strangely frozen in time. She was old but not super-old; thinking vaguely about death, but not at death’s door. The organizing principle, that everything can be understood on more than one level and so we must think beyond the literal, is interesting but not particularly applicable to the contents. There are mini travel pieces and pen portraits, but I got more out of the explorations of concepts (maturity, nationalism) and universal experiences (being caught picking one’s nose, sneezing).

Allegorizings by Jan Morris: Disparate, somewhat frivolous essays written mostly pre-2009, or in 2013, and kept in trust by her publisher for publication as a posthumous collection, so strangely frozen in time. She was old but not super-old; thinking vaguely about death, but not at death’s door. The organizing principle, that everything can be understood on more than one level and so we must think beyond the literal, is interesting but not particularly applicable to the contents. There are mini travel pieces and pen portraits, but I got more out of the explorations of concepts (maturity, nationalism) and universal experiences (being caught picking one’s nose, sneezing).  The Priory by Dorothy Whipple (read for book club): A cosy between-the-wars story, pleasant to read even though some awful things happen, or nearly happen. Like in Downton Abbey and the Cazalet Chronicles, there’s an upstairs/downstairs setup that’s appealing. It was interesting to watch how my sympathies shifted. The Persephone afterword provides useful information about the Welsh house (where Whipple stayed for a month in 1934) and family that inspired the novel. Whipple is a new author for me and I’m sure the rest of her books would be just as enjoyable, but I would only attempt another if it was significantly shorter than this one.

The Priory by Dorothy Whipple (read for book club): A cosy between-the-wars story, pleasant to read even though some awful things happen, or nearly happen. Like in Downton Abbey and the Cazalet Chronicles, there’s an upstairs/downstairs setup that’s appealing. It was interesting to watch how my sympathies shifted. The Persephone afterword provides useful information about the Welsh house (where Whipple stayed for a month in 1934) and family that inspired the novel. Whipple is a new author for me and I’m sure the rest of her books would be just as enjoyable, but I would only attempt another if it was significantly shorter than this one.