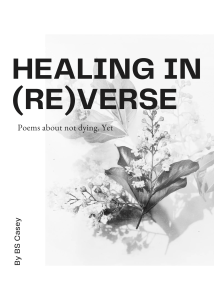

Healing in (Re)Verse: Poems about not dying. Yet by BS Casey (Blog Tour)

Bee Casey’s self-published debut collection contains a hard-hitting set of accessible poems arising from the conjunction of mental health crisis and disability. It opens with the sense of a golden era never to be regained: “the girl before / commanded the room // Oh how I wish I could even walk into it now.” Now the body brings only “pain and cruelty”: “an unwelcome guest / lingers on my chest / in bones and my home”.

Bee Casey’s self-published debut collection contains a hard-hitting set of accessible poems arising from the conjunction of mental health crisis and disability. It opens with the sense of a golden era never to be regained: “the girl before / commanded the room // Oh how I wish I could even walk into it now.” Now the body brings only “pain and cruelty”: “an unwelcome guest / lingers on my chest / in bones and my home”.

End rhymes, slant rhymes, and alliteration form part of the sonic palette. Through imagined conversations with the self and with others who have hurt the speaker or put them down, they wrestle with concepts of forgiveness and self-love. “Just a girl” chronicles instances of sexualized verbal and emotional abuse. The use of repeated words and phrases, with minor adaptations, along with the themes of trauma and recovery, reminded me of Rupi Kaur’s performance poetry-inspired style. “Monster” is more like a short story with its prose paragraphs and imagined dialogue. “How are you” is an erasure poem that crosses out all the possible genuine answers to that question in between, leaving only the socially acceptable “I’m fine thanks. … how are you?”

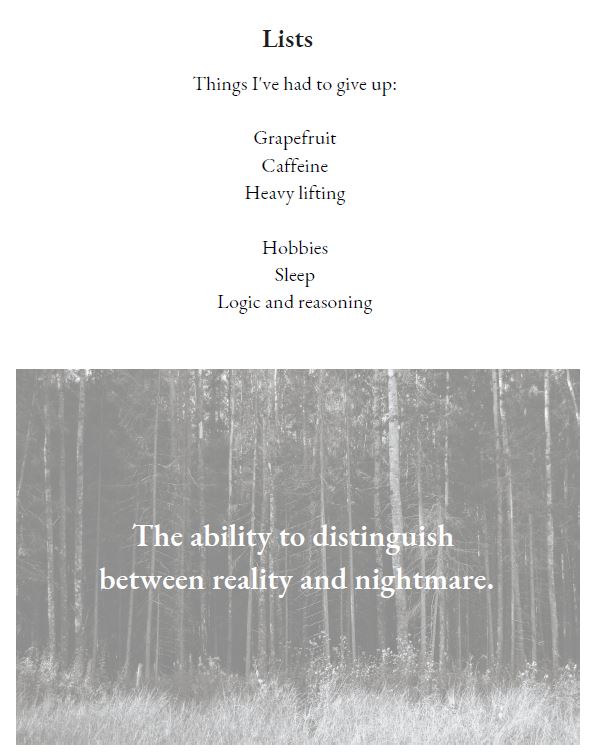

The pages’ stark black-and-white design is softened by background images of flowers, feathers, forests, candle flames, and shadows falling through windows. Although the tone is overwhelmingly sad, there is also some wry humour, as in the below.

Casey has only just turned 30, and it’s sobering to think how much they’ve gone through in that short time and how often suicide has been a temptation. It’s a relief to see that their view of life has shifted from it being a trial to a gift. “What an honour, a privilege / What beauty to grow old.” Sometimes for them, not dying has to be an active decision, as in the poem “Tomorrow I will kill myself,” but the habit can stick – for 15 years “I’ve been too busy / Accidentally being alive.”

Casey has only just turned 30, and it’s sobering to think how much they’ve gone through in that short time and how often suicide has been a temptation. It’s a relief to see that their view of life has shifted from it being a trial to a gift. “What an honour, a privilege / What beauty to grow old.” Sometimes for them, not dying has to be an active decision, as in the poem “Tomorrow I will kill myself,” but the habit can stick – for 15 years “I’ve been too busy / Accidentally being alive.”

Poetry – writing it or reading it – can be a great way for people to work through the pain of mental ill health and chronic illness and not feel so alone. That’s one reason I’m looking forward to the return of the Barbellion Prize later this year. “The Barbellion Prize celebrates and promotes writing that represents the experience of chronic illness and disability. The prize is named after the diarist W.N.P. Barbellion, who wrote eloquently on his life with multiple sclerosis (MS). It is a cross-genre award for literature published in the English language.” I’ve donated to get it up and running again; maybe you can, too?

My thanks to Random Things Tours and the author for the advanced e-copy for review.

See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will be appearing soon.

Three on a Theme of Sylvia Plath (The Slicks by Maggie Nelson for #NonfictionNovember & #NovNov25; The Bell Jar and Ariel)

A review copy of Maggie Nelson’s brand-new biographical essay on Sylvia Plath (and Taylor Swift) was the excuse I needed to finally finish a long-neglected paperback of The Bell Jar and also get a taste of Plath’s poetry through the posthumous collection Ariel, which is celebrating its 60th anniversary. These are the sorts of works it’s hard to believe ever didn’t exist; they feel so fully formed and part of the zeitgeist. It also boggles the mind how much Plath accomplished before her death by suicide at age 30. What I previously knew of her life mostly came from hearsay and was reinforced by Euphoria by Elin Cullhed. For the mixture of nonfiction, fiction and poetry represented below, I’m counting this towards Nonfiction November’s Book Pairings week.

The Slicks: On Sylvia Plath and Taylor Swift by Maggie Nelson (2025)

Can young women embrace fame amidst the other cultural expectations of them? Nelson attempts to answer this question by comparing two figures who turn(ed) life into art. The link between them was strengthened by Swift titling her 2024 album The Tortured Poets Department. “Plath … serves as a metonym – as does Swift – for a woman who makes art about a broken heart,” Nelson writes. “When women make the personal public, the charge of whorishness always lurks nearby.” What women are allowed to say and do has always, it seems, attracted public commentary, and “anyone who puts their work into the world, at any level, must learn to navigate between self-protectiveness and risk, becoming harder and staying soft.”

Can young women embrace fame amidst the other cultural expectations of them? Nelson attempts to answer this question by comparing two figures who turn(ed) life into art. The link between them was strengthened by Swift titling her 2024 album The Tortured Poets Department. “Plath … serves as a metonym – as does Swift – for a woman who makes art about a broken heart,” Nelson writes. “When women make the personal public, the charge of whorishness always lurks nearby.” What women are allowed to say and do has always, it seems, attracted public commentary, and “anyone who puts their work into the world, at any level, must learn to navigate between self-protectiveness and risk, becoming harder and staying soft.”

Nelson acknowledges a major tonal difference between Plath and Swift, however. Plath longed for fame but didn’t get the chance to enjoy it; she’s the patron saint of sad-girl poetry and makes frequent reference to death, whereas Swift spotlights joy and female empowerment. It’s a shame this was out of date before it went to print; my advanced copy, at least, isn’t able to comment on Swift’s engagement and the baby rumour mill sure to follow. It would be illuminating to have an afterword in which Nelson discusses the effect of spouses’ competing fame and speculates on how motherhood might change Swift’s art.

Full confession: I’ve only ever knowingly heard one Taylor Swift song, “Anti-Hero,” on the radio in the States. (My assessment was: wordy, angsty, reasonably catchy.) Undoubtedly, I would have gotten more out of this essay were I equally familiar with the two subjects. Nonetheless, it’s fluid and well argued, and I was engaged throughout. If you’re a Swiftie as well as a literary type, you need to read this.

[66 pages]

With thanks to Vintage (Penguin) for the advanced e-copy for review.

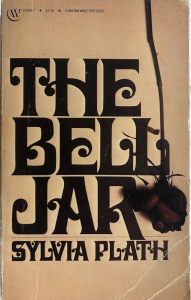

The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath (1963)

Given my love of mental hospital accounts and women’s autofiction, it’s a wonder I’d not read this before my forties. It was first published under the pseudonym “Victoria Lucas” because Plath thought it immature, “an autobiographical apprentice work which I had to write in order to free myself from the past.” Esther Greenwood is the stand-in for Plath: a talented college student who, after working in New York City during the remarkable summer of 1953, plunges into mental ill health. Chapter 13 is amazing and awful at the same time as Esther attempts suicide thrice in one day, toying with a silk bathrobe cord and ocean waves before taking 50 pills and walling herself into a corner of the cellar. She bounces between various institutional settings, undergoing electroshock therapy – the first time it’s horrible, but later, under a kind female doctor, it’s more like it’s ‘supposed’ to be: a calming reset.

Given my love of mental hospital accounts and women’s autofiction, it’s a wonder I’d not read this before my forties. It was first published under the pseudonym “Victoria Lucas” because Plath thought it immature, “an autobiographical apprentice work which I had to write in order to free myself from the past.” Esther Greenwood is the stand-in for Plath: a talented college student who, after working in New York City during the remarkable summer of 1953, plunges into mental ill health. Chapter 13 is amazing and awful at the same time as Esther attempts suicide thrice in one day, toying with a silk bathrobe cord and ocean waves before taking 50 pills and walling herself into a corner of the cellar. She bounces between various institutional settings, undergoing electroshock therapy – the first time it’s horrible, but later, under a kind female doctor, it’s more like it’s ‘supposed’ to be: a calming reset.

The 19-year-old is obsessed with the notion of purity. She has a couple of boyfriends but decides to look for someone else to take her virginity. Beforehand, the asylum doctor prescribes her a fitting for a diaphragm. A defiant claim to the right to contraception despite being unmarried is a way of resisting the bell jar – the rarefied prison – of motherhood. Still, Esther feels guilty about prioritizing her work over what seems like feminine duty: “Why was I so maternal and apart? Why couldn’t I dream of devoting myself to baby after fat puling baby? … I was my own woman.” Plath never reconciled parenthood with poetry. Whether that’s the fault of Ted Hughes, or the times they lived in, who can say. For her and for Esther, the hospital is a prison as well – but not so hermetic as the turmoil of her own mind. How ironic to read “I took a deep breath and listened to the old brag of my heart. I am, I am, I am” knowing that this was published just a few weeks before this literary genius ceased to be.

The 19-year-old is obsessed with the notion of purity. She has a couple of boyfriends but decides to look for someone else to take her virginity. Beforehand, the asylum doctor prescribes her a fitting for a diaphragm. A defiant claim to the right to contraception despite being unmarried is a way of resisting the bell jar – the rarefied prison – of motherhood. Still, Esther feels guilty about prioritizing her work over what seems like feminine duty: “Why was I so maternal and apart? Why couldn’t I dream of devoting myself to baby after fat puling baby? … I was my own woman.” Plath never reconciled parenthood with poetry. Whether that’s the fault of Ted Hughes, or the times they lived in, who can say. For her and for Esther, the hospital is a prison as well – but not so hermetic as the turmoil of her own mind. How ironic to read “I took a deep breath and listened to the old brag of my heart. I am, I am, I am” knowing that this was published just a few weeks before this literary genius ceased to be.

Apart from an unfortunate portrayal of a “negro” worker at the hospital, this was an enduringly relevant and absorbing read, a classic to sit alongside Emily Holmes Coleman’s The Shutter of Snow and Janet Frame’s Faces in the Water.

(Secondhand – it’s been in my collection so long I can’t remember where it’s from, but I’d guess a Bowie Library book sale or Wonder Book & Video / Public library – I was struggling with the small type so switched to a recent paperback and found it more readable)

Ariel by Sylvia Plath (1965)

Impossible not to read this looking for clues of her death to come:

Dying

Is an art, like everything else.

I do it exceptionally well.

(from “Lady Lazarus”)

Eternity bores me,

I never wanted it.

(from “Years”)

The woman is perfected.

Her dead

Body wears the smile of accomplishment

(from “Edge”)

I feel incapable of saying anything fresh about this collection, which takes no prisoners. The images and vocabulary are razor-sharp. First and last lines or stanzas are particularly memorable. (“Morning Song” starts “Love set you going like a fat gold watch”; “Lady Lazarus” ends “Out of the ash / I rise with my red hair / And I eat men like air.”) Words and phrases repeat and gather power as they go. “The Applicant” mocks the obligations of a wife: “A living doll … / It can sew, it can cook. It can talk, talk, talk. … // … My boy, it’s your last resort. / Will you marry it, marry it, marry it.” I don’t know a lot about Plath’s family life, only that her father was a Polish immigrant and died after a long illness when she was eight, but there must have been some daddy issues there – after all, “Daddy” includes the barbs “Daddy, I have had to kill you” and “If I’ve killed one man, I’ve killed two— / The vampire who said he was you / And drank my blood for a year, / Seven years, if you want to know.” It ends, “Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through.” Several later poems in a row, including “Stings,” incorporate bee-related imagery, and Plath’s father was an international bee expert. I can see myself reading this again and again in future, and finding her other collections, too – all but one of them posthumous. (Secondhand – RSPCA charity shop, Newbury)

I feel incapable of saying anything fresh about this collection, which takes no prisoners. The images and vocabulary are razor-sharp. First and last lines or stanzas are particularly memorable. (“Morning Song” starts “Love set you going like a fat gold watch”; “Lady Lazarus” ends “Out of the ash / I rise with my red hair / And I eat men like air.”) Words and phrases repeat and gather power as they go. “The Applicant” mocks the obligations of a wife: “A living doll … / It can sew, it can cook. It can talk, talk, talk. … // … My boy, it’s your last resort. / Will you marry it, marry it, marry it.” I don’t know a lot about Plath’s family life, only that her father was a Polish immigrant and died after a long illness when she was eight, but there must have been some daddy issues there – after all, “Daddy” includes the barbs “Daddy, I have had to kill you” and “If I’ve killed one man, I’ve killed two— / The vampire who said he was you / And drank my blood for a year, / Seven years, if you want to know.” It ends, “Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through.” Several later poems in a row, including “Stings,” incorporate bee-related imagery, and Plath’s father was an international bee expert. I can see myself reading this again and again in future, and finding her other collections, too – all but one of them posthumous. (Secondhand – RSPCA charity shop, Newbury)

Summer Reading 2025: Anthony, Espach, Han & Teir

In the UK, summer doesn’t officially end until the 22nd, so even though I’ve been doing plenty of baking with apples and plums and we’ve had squashes delivered in our vegetable box, I’ve taken advantage of that extra time to finish a couple more summery books. This year I’m featuring four novels ranging in location from Rhode Island to Finland. I’ve got all the trappings of summer: a swimming pool, a wedding, a beach retreat, and a summer house.

The Most by Jessica Anthony (2024)

I can’t resist a circadian narrative. This novella takes place in Delaware on one day in early November 1957, but flashbacks and close third-person narration reveal everything we need to know about Virgil and Kathleen Beckett and their marriage. I’m including it in my summer reading because it’s set on an unseasonably warm Sunday and Kathleen decides to spend the entire day in their apartment complex’s pool. The mother of two drifts back in memory to her college tennis-playing days and her first great love, Billy Blasko, a Czech tennis coach who created a signature move called “The Most,” which means “bridge” in his language – the idea is to trap your opponent and then drop a bomb on them. Virgil, who after taking their two boys to church goes golfing with his insurance sales colleagues as is expected of him, loves jazz music and has just been sent the secret gift of a saxophone. Both spouses are harbouring secrets and, as Laika orbits the Earth overhead, they wonder if they can break free from the capsules they’ve built around their hearts and salvage their relationship. The storytelling is tight even as the book loops around the same events from the two perspectives. This was really well done, and a big step up from Enter the Aardvark. (Public library)

I can’t resist a circadian narrative. This novella takes place in Delaware on one day in early November 1957, but flashbacks and close third-person narration reveal everything we need to know about Virgil and Kathleen Beckett and their marriage. I’m including it in my summer reading because it’s set on an unseasonably warm Sunday and Kathleen decides to spend the entire day in their apartment complex’s pool. The mother of two drifts back in memory to her college tennis-playing days and her first great love, Billy Blasko, a Czech tennis coach who created a signature move called “The Most,” which means “bridge” in his language – the idea is to trap your opponent and then drop a bomb on them. Virgil, who after taking their two boys to church goes golfing with his insurance sales colleagues as is expected of him, loves jazz music and has just been sent the secret gift of a saxophone. Both spouses are harbouring secrets and, as Laika orbits the Earth overhead, they wonder if they can break free from the capsules they’ve built around their hearts and salvage their relationship. The storytelling is tight even as the book loops around the same events from the two perspectives. This was really well done, and a big step up from Enter the Aardvark. (Public library) ![]()

The Wedding People by Alison Espach (2024)

You’ve all heard about this one, right? It’s been a Read with Jenna selection and the holds are stacking up in my library system. No wonder it’s been hailed as a perfect summer read: it’s full of sparkling banter; heartwarming, very funny and quite sexy. And that despite a grim opening situation: Phoebe flies from St. Louis to Newport and checks into a luxury hotel, intending to kill herself. She’s an adjunct professor whose husband left her for their colleague after their IVF attempts failed, and she feels she’ll never finish writing her book, become a mother or find true love again. Little does she know that a Bridezilla type named Lila who’s spent $1 million of her inheritance on a week-long wedding extravaganza (culminating in a ceremony at The Breakers mansion) meant to book out the entire hotel. Phoebe somehow snagged the room with the best view. Lila isn’t about to let anyone ruin her wedding.

You’ve all heard about this one, right? It’s been a Read with Jenna selection and the holds are stacking up in my library system. No wonder it’s been hailed as a perfect summer read: it’s full of sparkling banter; heartwarming, very funny and quite sexy. And that despite a grim opening situation: Phoebe flies from St. Louis to Newport and checks into a luxury hotel, intending to kill herself. She’s an adjunct professor whose husband left her for their colleague after their IVF attempts failed, and she feels she’ll never finish writing her book, become a mother or find true love again. Little does she know that a Bridezilla type named Lila who’s spent $1 million of her inheritance on a week-long wedding extravaganza (culminating in a ceremony at The Breakers mansion) meant to book out the entire hotel. Phoebe somehow snagged the room with the best view. Lila isn’t about to let anyone ruin her wedding.

What follows is Cinderella-like yet takes into account the realities of bereavement, infidelity, infertility and blended families. Because of the one-week format, Phoebe’s depression is defused more quickly than is plausible, but I was relieved that Espach doesn’t plump for a full-blown happy ending. I did also find the novel unnecessarily crass in places, especially the gag about the car. Still, this has all the wit of Katherine Heiny and Curtis Sittenfeld. I’d recommend it if you enjoyed Dream State or Consider Yourself Kissed, and it’s especially reminiscent of Sorrow and Bliss for the mixture of humour and frank consideration of mental health. It’s as easy to relate to Phoebe’s feelings (“How much of her life had she spent in this moment, waiting for someone else to decide something conclusive about her?”; “It is so much easier to sit in things and wait for someone to save us”) as it is to laugh at the one-liners. “Garys are not wonderful. That’s just not what they are meant to be” particularly tickled me because I know a few Garys in real life. (Public library) ![]()

The Summer I Turned Pretty by Jenny Han (2008)

Every summer Belly and her mother and brother have joined her mother’s best friend Susannah and her sons Conrad and Jeremiah at their beach house. She’s had a crush on Conrad for what’s felt like forever, but she’s only ever been his surrogate little sister, fun for palling around with but never taken seriously. This summer is different, though: Belly is turning 16, it’s Conrad’s last summer before college, and his family seems to be falling apart. The novel kept being requested off me and I puzzled over how it could have eight reservations on it until I realized there’s an Amazon Prime Video adaptation now in its third and final season. I reckon the story will work better on screen because Belly’s narration was the main issue for me. She’s ever so shallow, so caught up in boys that she doesn’t realize Susannah is sick again. Her fixation on the brooding Conrad doesn’t make sense when she could have affable Jeremiah or sweet, geeky Cam, who met her through Latin club and liked her before she grew big boobs. He’s who she’s supposed to be with in this kind of story, right? I think this would appeal to younger, boy-crazy teens, but it just made me feel old and grumpy. (Public library)

Every summer Belly and her mother and brother have joined her mother’s best friend Susannah and her sons Conrad and Jeremiah at their beach house. She’s had a crush on Conrad for what’s felt like forever, but she’s only ever been his surrogate little sister, fun for palling around with but never taken seriously. This summer is different, though: Belly is turning 16, it’s Conrad’s last summer before college, and his family seems to be falling apart. The novel kept being requested off me and I puzzled over how it could have eight reservations on it until I realized there’s an Amazon Prime Video adaptation now in its third and final season. I reckon the story will work better on screen because Belly’s narration was the main issue for me. She’s ever so shallow, so caught up in boys that she doesn’t realize Susannah is sick again. Her fixation on the brooding Conrad doesn’t make sense when she could have affable Jeremiah or sweet, geeky Cam, who met her through Latin club and liked her before she grew big boobs. He’s who she’s supposed to be with in this kind of story, right? I think this would appeal to younger, boy-crazy teens, but it just made me feel old and grumpy. (Public library) ![]()

The Summer House by Philip Teir (2017; 2018)

[Translated from Swedish by Tiina Nunnally]

The characters are Finland-Swedish, like the author. Erik and Julia escape Helsinki with their children, Alice and Anton, to spend time at her father’s summer house. Erik has just lost his job in IT for a large department store, but hasn’t told Julia yet. Julia is working on a novel, but distracted by the fact that her childhood friend Marika, the not so secret inspiration for a character in her previous novel, is at another vacation home nearby with Chris, her Scottish partner. These two and their hangers-on have a sort of commune based around free love and extreme environmental realism: the climate crisis will not be solved (“accepting the grief instead of talking about hope all the time”) and the only thing to do is participate in de-civilisation. But like many a cult leader, Chris courts young female attention and isn’t the best role model. Both couples are strained to breaking point.

The characters are Finland-Swedish, like the author. Erik and Julia escape Helsinki with their children, Alice and Anton, to spend time at her father’s summer house. Erik has just lost his job in IT for a large department store, but hasn’t told Julia yet. Julia is working on a novel, but distracted by the fact that her childhood friend Marika, the not so secret inspiration for a character in her previous novel, is at another vacation home nearby with Chris, her Scottish partner. These two and their hangers-on have a sort of commune based around free love and extreme environmental realism: the climate crisis will not be solved (“accepting the grief instead of talking about hope all the time”) and the only thing to do is participate in de-civilisation. But like many a cult leader, Chris courts young female attention and isn’t the best role model. Both couples are strained to breaking point.

Meanwhile, Chris and Marika’s son, Leo, has been sneaking off with Alice; and Erik’s brother Anders shows up and starts seeing the widowed therapist neighbour. This was a reasonably likeable book about how we respond to crises personal and global, and how we react to our friends’ successes and problems – Erik is jealous of his college buddy’s superior performance in a tech company. But I thought it was a little aimless, especially in its subplots, and it suffered in comparison with Leave the World Behind, which has quite a similar setup but a more intriguing cosmic/dystopian direction. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

Any final summer books for you this year?

Literary Wives Club: Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins (2008)

Although Emily Perkins was a new name to me, the New Zealand author has published five novels and a short story collection. Unfortunately, I never engaged with her London-set Novel About My Wife. On the one hand, it must have been an intriguing challenge for Perkins to inhabit a man’s perspective and examine how a widower might recreate his marriage and his late wife’s mental state. “I can’t speak for Ann[,] obviously, only about her,” screenwriter Tom Stone admits. On the other hand, Tom is so egotistical and self-absorbed that his portrait of Ann is more obfuscating than illuminating.

Although Emily Perkins was a new name to me, the New Zealand author has published five novels and a short story collection. Unfortunately, I never engaged with her London-set Novel About My Wife. On the one hand, it must have been an intriguing challenge for Perkins to inhabit a man’s perspective and examine how a widower might recreate his marriage and his late wife’s mental state. “I can’t speak for Ann[,] obviously, only about her,” screenwriter Tom Stone admits. On the other hand, Tom is so egotistical and self-absorbed that his portrait of Ann is more obfuscating than illuminating.

“If I could build her again using words, I would,” he opens, but that promising start just leads into paragraphs of physical description. Bare facts, such as that Ann was from Sydney and created radiation masks for cancer patients in a hospital, are hardly revealing. We mostly know Ann through her delusions. In her late thirties, when she was three months pregnant with their son Arlo, she was caught in an underground train derailment. Thereafter, she increasingly fell victim to paranoia, believing that she was being stalked and that their house was infested. We’re invited to speculate that pregnancy exacerbated her mental health issues and that postpartum psychosis may have had something to do with her death.

I mostly skimmed the novel, so I may have missed some plot points, but what stood out to me were Tom’s unpleasant depictions of women and complaints about his faltering career. (He’s envious of a new acquaintance, Simon, who’s back and forth to Hollywood all the time for successful screenwriting projects.) Interspersed are seemingly pointless excerpts from Tom’s screenplay about a trip he and Ann took to Fiji. I longed for the balance of another perspective. This had a bit of the flavour of early Maggie O’Farrell, but none of the warmth. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

Being generous to Perkins, perhaps the very point she was trying to make is that it’s impossible to get outside of one’s own perspective and understand what’s going on with a spouse, especially one who has mental health struggles. Had Tom been more attentive and supportive, might things have ended differently?

See Becky’s, Kate’s and Kay’s reviews, too! (Naomi is on a break this month.)

Coming up next, in December: The Soul of Kindness by Elizabeth Taylor.

April Releases by Chung, Ellis, Gaige, Lutz, McAlpine and Rubin

April felt like a crowded publishing month, though May looks to be twice as busy again. Adding this batch to my existing responses to books by Jean Hannah Edelstein & Emily Jungmin Yoon plus Richard Scott, I reviewed nine April releases. Today I’m featuring a real mix of books by women, starting with two foodie family memoirs, moving through a suspenseful novel about a lost hiker, a sparse Scandinavian novella, and a lovely poetry collection with themes of nature and family, and finishing up with a collection of aphorisms. I challenged myself to write just a paragraph on each for simplicity and readability.

Chinese Parents Don’t Say I Love You: A memoir of saying the unsayable with food by Candice Chung

“to love is to gamble, sometimes gastrointestinally … The stomach is a simple animal. But how do we settle the heart—a flailing, skittish thing?”

I got Caroline Eden (Cold Kitchen) and Nina Mingya Powles (Tiny Moons) vibes from this vibrant essay collection spotlighting food and family. The focus is on 2019–2021, a time of huge changes for Chung. She’s from Hong Kong via Australia, and reconnects with her semi-estranged parents by taking them along on restaurant review gigs for a Sydney newspaper. Fresh from a 13-year relationship with “the psychic reader,” she starts dating again and quickly falls in deep with “the geographer.” Sharing meals in restaurants and at home kindles closeness and keeps their spirits up after Covid restrictions descend. But when he gets a job offer in Scotland, they have to make decisions about their relationship sooner than intended. Although there is a chronological through line, the essays range in time and style, including second-person advice column (“Faux Pas”) and choose-your-own adventure (“Self-Help Meal”) segments alongside lists, message threads and quotes from the likes of Deborah Levy. My favourite piece was “The Soup at the End of the Universe.” Chung delicately contrasts past and present, singleness and being partnered, and different mental health states. The essays meld to capture a life in transition and the tastes and bonds that don’t alter.

I got Caroline Eden (Cold Kitchen) and Nina Mingya Powles (Tiny Moons) vibes from this vibrant essay collection spotlighting food and family. The focus is on 2019–2021, a time of huge changes for Chung. She’s from Hong Kong via Australia, and reconnects with her semi-estranged parents by taking them along on restaurant review gigs for a Sydney newspaper. Fresh from a 13-year relationship with “the psychic reader,” she starts dating again and quickly falls in deep with “the geographer.” Sharing meals in restaurants and at home kindles closeness and keeps their spirits up after Covid restrictions descend. But when he gets a job offer in Scotland, they have to make decisions about their relationship sooner than intended. Although there is a chronological through line, the essays range in time and style, including second-person advice column (“Faux Pas”) and choose-your-own adventure (“Self-Help Meal”) segments alongside lists, message threads and quotes from the likes of Deborah Levy. My favourite piece was “The Soup at the End of the Universe.” Chung delicately contrasts past and present, singleness and being partnered, and different mental health states. The essays meld to capture a life in transition and the tastes and bonds that don’t alter.

With thanks to Elliott & Thompson for the free copy for review.

Chopping Onions on My Heart: On Losing and Preserving Culture by Samantha Ellis

Ellis was distressed to learn that her refugee parents’ first language, Judeo-Iraqi Arabic, is in danger of extinction. Her own knowledge of it is piecemeal, mostly confined to its colourful food-inspired sayings – for example, living “eeyam al babenjan (in the days of the aubergines)” means that everything feels febrile and topsy-turvy. She recounts her family’s history with conflict and displacement, takes a Zoom language class, and ponders what words, dishes, and objects she would save on an imaginary “ark” that she hopes to bequeath to her son. Along the way, she reveals surprising facts about Ashkenazi domination of the Jewish narrative. “Did you know the poet [Siegfried Sassoon] was an Iraqi Jew?” His great-grandfather even invented a special variety of mango pickle. All of the foods described sound delicious, and some recipes are given. Ellis’s writing is enthusiastic and she braids the book’s various strands effectively. I wasn’t as interested in the niche history as I wanted to be, but I did appreciate learning about an endangered culture and language.

Ellis was distressed to learn that her refugee parents’ first language, Judeo-Iraqi Arabic, is in danger of extinction. Her own knowledge of it is piecemeal, mostly confined to its colourful food-inspired sayings – for example, living “eeyam al babenjan (in the days of the aubergines)” means that everything feels febrile and topsy-turvy. She recounts her family’s history with conflict and displacement, takes a Zoom language class, and ponders what words, dishes, and objects she would save on an imaginary “ark” that she hopes to bequeath to her son. Along the way, she reveals surprising facts about Ashkenazi domination of the Jewish narrative. “Did you know the poet [Siegfried Sassoon] was an Iraqi Jew?” His great-grandfather even invented a special variety of mango pickle. All of the foods described sound delicious, and some recipes are given. Ellis’s writing is enthusiastic and she braids the book’s various strands effectively. I wasn’t as interested in the niche history as I wanted to be, but I did appreciate learning about an endangered culture and language.

With thanks to Chatto & Windus (Vintage/Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Heartwood by Amity Gaige

This was on my Most Anticipated list after how much I’d enjoyed Sea Wife when we read it for Literary Wives club. In July 2022, 42-year-old nurse Valerie Gillis, nicknamed “Sparrow,” goes missing in the Maine woods while hiking the Appalachian Trail. An increasingly desperate search ensues as the chances of finding her alive diminish with each day. The shifting formats – letters, transcripts, news reports, tip line messages – hold the interest. However, the chapters voiced by Lt. Bev, the warden who heads the mission, are much the most engaging, and it’s a shame that her delightful interactions with her sisters and nieces are so few and come so late. The third-person passages about Lena Kucharski in her Connecticut retirement home are intriguing but somehow feel like they belong in a different book. Gaige attempts to bring the threads together through three mother–daughter pairs, which struck me as heavy-handed. Mostly, this hits the sweet spot between mystery and literary fiction (apart from some red herrings), but because I wasn’t particularly invested in the characters, even Valerie, this fell a little short of my expectations. (Read via Edelweiss)

This was on my Most Anticipated list after how much I’d enjoyed Sea Wife when we read it for Literary Wives club. In July 2022, 42-year-old nurse Valerie Gillis, nicknamed “Sparrow,” goes missing in the Maine woods while hiking the Appalachian Trail. An increasingly desperate search ensues as the chances of finding her alive diminish with each day. The shifting formats – letters, transcripts, news reports, tip line messages – hold the interest. However, the chapters voiced by Lt. Bev, the warden who heads the mission, are much the most engaging, and it’s a shame that her delightful interactions with her sisters and nieces are so few and come so late. The third-person passages about Lena Kucharski in her Connecticut retirement home are intriguing but somehow feel like they belong in a different book. Gaige attempts to bring the threads together through three mother–daughter pairs, which struck me as heavy-handed. Mostly, this hits the sweet spot between mystery and literary fiction (apart from some red herrings), but because I wasn’t particularly invested in the characters, even Valerie, this fell a little short of my expectations. (Read via Edelweiss)

Wild Boar by Hannah Lutz (2016; 2025)

[Translated from Swedish by Andy Turner]

“I have seen them, the wild boar, they have found their way into my dreams!” Ritve travels from Finland to the forests of southern Sweden to track the creatures. Glenn, who appraises project applications for the council, has boar wander onto his property in the middle of the night. Mia, recipient of a council grant for her Recollections of a Sigga Child proposal, brings her ailing grandfather to record his memories for the local sound archive. As midsummer approaches, these three characters plus a couple of their partners will have encounters with the boar and with each other. Short sections alternate between their first-person perspectives. There is a strong sense of place and how migration poses challenges for both the human and more-than-human worlds. But it’s over before it begins. I found myself frustrated by how little happens, how stingily the characters reveal themselves, and how the boar, ultimately, are no more than a metaphor or plot device – a frequent complaint of mine when animals are central to a narrative. This might appeal to fans of Melissa Harrison’s fiction. In any case, I congratulate The Emma Press on their first novel, which won an English PEN Award.

“I have seen them, the wild boar, they have found their way into my dreams!” Ritve travels from Finland to the forests of southern Sweden to track the creatures. Glenn, who appraises project applications for the council, has boar wander onto his property in the middle of the night. Mia, recipient of a council grant for her Recollections of a Sigga Child proposal, brings her ailing grandfather to record his memories for the local sound archive. As midsummer approaches, these three characters plus a couple of their partners will have encounters with the boar and with each other. Short sections alternate between their first-person perspectives. There is a strong sense of place and how migration poses challenges for both the human and more-than-human worlds. But it’s over before it begins. I found myself frustrated by how little happens, how stingily the characters reveal themselves, and how the boar, ultimately, are no more than a metaphor or plot device – a frequent complaint of mine when animals are central to a narrative. This might appeal to fans of Melissa Harrison’s fiction. In any case, I congratulate The Emma Press on their first novel, which won an English PEN Award.

With thanks to The Emma Press for the free copy for review.

Small Pointed Things by Erica McAlpine

McAlpine is an associate professor of English at Oxford. Her second poetry collection is full of flora and fauna imagery. The title phrase comes from the opening poem, “Bats and Swallows” – in the “gloaming,” it’s hard to tell the difference between the flying creatures. The verse is bursting with alliteration and end rhymes, as just this first one shows (emphasis mine): “we couldn’t see / from where we stood in soft shadows / any signs that they were swallows // or bats”; “One seemed almost iridescent / as I tried to track / its crescent / flight across the hill.” Other poems consider moths, manatees, bees, swans and ladybirds; snowdrops and a cedar tree. Part II expands the view through conversations, theories and travel. What-ifs, consequences and regrets seep in. Parts III and IV incorporate mythical allusions, elegies and the concerns of motherhood. Sometimes the rhyme scheme adheres to a particular form. For instance, I loved “Triolet on My Mother’s 74th Birthday” – “You cannot imagine one season in another. … You cannot imagine life without your mother.” This is just my sort of poetry, sweet on the ear and rooted in nature and the everyday. A sample poem:

McAlpine is an associate professor of English at Oxford. Her second poetry collection is full of flora and fauna imagery. The title phrase comes from the opening poem, “Bats and Swallows” – in the “gloaming,” it’s hard to tell the difference between the flying creatures. The verse is bursting with alliteration and end rhymes, as just this first one shows (emphasis mine): “we couldn’t see / from where we stood in soft shadows / any signs that they were swallows // or bats”; “One seemed almost iridescent / as I tried to track / its crescent / flight across the hill.” Other poems consider moths, manatees, bees, swans and ladybirds; snowdrops and a cedar tree. Part II expands the view through conversations, theories and travel. What-ifs, consequences and regrets seep in. Parts III and IV incorporate mythical allusions, elegies and the concerns of motherhood. Sometimes the rhyme scheme adheres to a particular form. For instance, I loved “Triolet on My Mother’s 74th Birthday” – “You cannot imagine one season in another. … You cannot imagine life without your mother.” This is just my sort of poetry, sweet on the ear and rooted in nature and the everyday. A sample poem:

“Clementines”

New Year’s Day – another turning

of the sphere, with all we planned

in yesteryear as close to hand

as last night’s coals left unmanned

in the fire, still orange and burning.

It is the season for clementines

and citrus from Seville

and whatever brightness carries us until

leaves and petals once more fill

the treetops and the vines.

If ever you were to confess

some cold truth about love’s

dwindling, now would be the time – less

in order for things to improve

than for the half-bitter happiness

of peeling rinds

during mid-winter

recalling days that are behind

us and doors we cannot re-enter

and other doors we couldn’t find.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the advanced e-copy for review.

Secrets of Adulthood: Simple Truths for Our Complex Lives by Gretchen Rubin

Rubin is one of the best self-help authors out there: Her books are practical, well-researched and genuinely helpful. She understands human nature and targets her strategies to suit different personality types. If you know her work, you’re likely aware of her fondness for aphorisms. “Sometimes, a single sentence can provide all the insight we need,” she believes. Here she collects her own pithy sayings relating to happiness, self-knowledge, relationships, work, creativity and decision-making. Some of the aphorisms were familiar to me through her previous books or her social media. They’re straightforward and sensible, distilling down to a few words truths we might be aware of but hadn’t truly absorbed. Like the great aphorists throughout history, Rubin relishes alliteration, repetition and contrasts. Some examples:

Rubin is one of the best self-help authors out there: Her books are practical, well-researched and genuinely helpful. She understands human nature and targets her strategies to suit different personality types. If you know her work, you’re likely aware of her fondness for aphorisms. “Sometimes, a single sentence can provide all the insight we need,” she believes. Here she collects her own pithy sayings relating to happiness, self-knowledge, relationships, work, creativity and decision-making. Some of the aphorisms were familiar to me through her previous books or her social media. They’re straightforward and sensible, distilling down to a few words truths we might be aware of but hadn’t truly absorbed. Like the great aphorists throughout history, Rubin relishes alliteration, repetition and contrasts. Some examples:

Accept yourself, and expect more from yourself.

I admire nature, and I am also nature. I resent traffic, and I am also traffic.

Work is the play of adulthood. If we’re not failing, we’re not trying hard enough.

Don’t wait until you have more free time. You may never have more free time.

This is not as meaty as her other work, and some parts feel redundant, but that’s the nature of the project. It would make a good bedside book for nibbles of inspiration. (Read via Edelweiss)

Which of these appeal to you?

June Releases by Caroline Bird, Kathleen Jamie, Glynnis MacNicol and Naomi Westerman

These four books by women all incorporate life writing to an extent. Although the forms differ, a common theme – as in the other June releases I’ve reviewed, Sandwich and Others Like Me – is grappling with what a woman’s life should be, especially for those who have taken an unconventional path (i.e. are queer or childless) or are in midlife or later. I’ve got a poet up to her usual surreal shenanigans but with a new focus on lesbian parenting; a hybrid collection of poetry and prose giving snapshots of nature in crisis; an account of a writer’s hedonistic month in pandemic-era Paris; and mordant essays about death culture.

Ambush at Still Lake by Caroline Bird

Caroline Bird has become one of my favourite contemporary poets over the past few years. Her verse is joyously cheeky and absurdist. A great way to sample it is via her selected poems, Rookie. This seventh collection is muted by age and circumstance – multiple weddings and a baby – but still hilarious in places. Instead of rehab or hospital as in In These Days of Prohibition, the setting is mostly the domestic sphere. Even here, bizarre things happen. The police burst in at 4 a.m. for no particular reason; search algorithms and the baby monitor go haywire. Her brother calls to deliver a paranoid rant (in “Up and at ’Em”), while Nannie Edna’s dying wish is to dangle her great-grandson from her apartment window (in “Last Rites”). The clinic calls to announce that their sperm donor was a serial killer – then ‘oops, wrong vial, never mind!’ A toddler son’s strange and megalomaniac demands direct their days. My two favourites were “Ants,” in which a kitchen infestation signals general chaos, and “The Frozen Aisle,” in which a couple scrambles to finish the grocery shop and get home to bed before a rare horny moment passes. A lesbian pulp fiction cover, mischievous wit and topics of addiction and queer parenting: this is not your average poetry.

Caroline Bird has become one of my favourite contemporary poets over the past few years. Her verse is joyously cheeky and absurdist. A great way to sample it is via her selected poems, Rookie. This seventh collection is muted by age and circumstance – multiple weddings and a baby – but still hilarious in places. Instead of rehab or hospital as in In These Days of Prohibition, the setting is mostly the domestic sphere. Even here, bizarre things happen. The police burst in at 4 a.m. for no particular reason; search algorithms and the baby monitor go haywire. Her brother calls to deliver a paranoid rant (in “Up and at ’Em”), while Nannie Edna’s dying wish is to dangle her great-grandson from her apartment window (in “Last Rites”). The clinic calls to announce that their sperm donor was a serial killer – then ‘oops, wrong vial, never mind!’ A toddler son’s strange and megalomaniac demands direct their days. My two favourites were “Ants,” in which a kitchen infestation signals general chaos, and “The Frozen Aisle,” in which a couple scrambles to finish the grocery shop and get home to bed before a rare horny moment passes. A lesbian pulp fiction cover, mischievous wit and topics of addiction and queer parenting: this is not your average poetry.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

A sample poem:

Siblings

A woman gave birth

to the reincarnation

of Gilbert and Sullivan

or rather, two reincarnations:

one Gilbert, one Sullivan.

What are the odds

of both being resummoned

by the same womb

when they could’ve been

a blue dart frog

and a supply teacher

on separate continents?

Yet here they were, squidged

into a tandem pushchair

with their best work

behind them, still smarting

from the critical reception

of their final opera

described as ‘but an echo’

of earlier collaborations.

Cairn by Kathleen Jamie

As she approached age 60, Kathleen Jamie found her style changing. Whereas her other essay collections alternate extended nature or travel pieces with few-page vignettes, Cairn eschews longer material and instead alternates poems with micro-essays on climate crisis and outdoor experiences. In the prologue she calls these “distillations and observations. Testimonies” that she has assembled into “A cairn of sorts.”

As she approached age 60, Kathleen Jamie found her style changing. Whereas her other essay collections alternate extended nature or travel pieces with few-page vignettes, Cairn eschews longer material and instead alternates poems with micro-essays on climate crisis and outdoor experiences. In the prologue she calls these “distillations and observations. Testimonies” that she has assembled into “A cairn of sorts.”

As in Surfacing, she writes many of the autobiographical fragments in the second person. The book is melancholy at times, haunted by all that has been lost and will be lost in the future:

What do we sense on the moor but ghost folk,

ghost deer, even ghost wolf. The path itself is a

phantom, almost erased in ling and yellow tormentil (from “Moor”)

In “The Bass Rock,” Jamie laments the effect that bird flu has had on this famous gannet colony and wishes desperately for better news:

The light glances on the water. The haze clears, and now the rock is visible; it looks depleted. But hallelujah, a pennant of twenty-odd gannets is passing, flying strongly, now rising now falling They’ll be Bass Rock birds. What use the summer sunlight, if it can’t gleam on a gannet’s back? You can only hope next year will be different. Stay alive! You call after the flying birds. Stay alive!

Natural wonders remind her of her own mortality and the insignificance of human life against deep time. “I can imagine the world going on without me, which one doesn’t at 30.” She questions the value of poetry in a time of emergency: “If we are entering a great dismantling, we can hardly expect lyric to survive. How to write a lyric poem?” (from “Summer”). The same could be said of any human endeavour in the face of extinction: We question the point but still we continue.

My two favourite pieces were “The Handover,” about going on an environmental march with her son and his friends in Glasgow and comparing it with the protests of her time (Greenham Common and nuclear disarmament) – doom and gloom was ever thus – and the title poem, which piles natural image on image like a cone of stones. Although I prefer the depth of Jamie’s other books to the breadth of this one, she is an invaluable nature writer for her wisdom and eloquence, and I am grateful we have heard from her again after five years.

With thanks to Sort Of Books for the free copy for review.

I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself: One Woman’s Pursuit of Pleasure in Paris by Glynnis MacNicol

I loved New York City freelance writer Glynnis MacNicol’s No One Tells You This (2018), which approached her 40th year as an adventure into the unknown. This second memoir is similarly frank and intrepid as MacNicol examines the unconscious rules that people set for women in their mid-forties and gleefully flouts them, remaining single and childfree and delighting in the freedom that allows her to book a month in Paris on a whim. She knows that she is an anomaly for being “untethered”; “I am ready for anything. To be anyone.”

I loved New York City freelance writer Glynnis MacNicol’s No One Tells You This (2018), which approached her 40th year as an adventure into the unknown. This second memoir is similarly frank and intrepid as MacNicol examines the unconscious rules that people set for women in their mid-forties and gleefully flouts them, remaining single and childfree and delighting in the freedom that allows her to book a month in Paris on a whim. She knows that she is an anomaly for being “untethered”; “I am ready for anything. To be anyone.”

This takes place in August 2021, when some pandemic restrictions were still in force, and she found the city – a frequent destination for her over the years – drained of locals, who were all en vacances, and largely empty of tourists, too. Although there was still a queue for the Mona Lisa, she otherwise found the Louvre very quiet, and could ride her borrowed bike through the streets without having to look out for cars. She and her single girlfriends met for rosé-soaked brunches and picnics, joined outdoor dance parties and took an island break.

And then there was the sex. MacNicol joined a hook-up app called Fruitz and met all sorts of men. She refused to believe that, just because she was 46 going on 47, she should be invisible or demure. “All the attention feels like pure oxygen. Anything is possible.” Seeing herself through the eyes of an enraptured 27-year-old Italian reminded her that her body was beautiful even if it wasn’t what she remembered from her twenties (“there is, on average, a five-year gap between current me being able to enjoy the me in the photos”). The book’s title is something she wrote while messaging with one of her potential partners.

As I wrote yesterday about Others Like Me, there are plenty of childless role models but you may have to look a bit harder for them. MacNicol does so by tracking down the Paris haunts of women writers such as Edith Wharton and Colette. She also interrogates this idea of women living a life of pleasure by researching the “odalisque” in 18th- and 19th-century art, as in the François Boucher painting on the cover. This was fun, provocative and thoughtful all at once; well worth seeking out for summer reading and armchair travelling.

(Read via Edelweiss) Published in the USA by Penguin Life/Random House.

Happy Death Club: Essays on Death, Grief & Bereavement across Cultures by Naomi Westerman

Like Erica Buist (This Party’s Dead) and Caitlin Doughty (Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, From Here to Eternity and Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs?), playwright Naomi Westerman finds the comical side of death. Part of 404 Ink’s Inklings series (“Big ideas, pocket-sized books” – perfect for anyone looking for short nonfiction for Novellas in November!), this is a collection of short essays about her own experiences of bereavement as well as her anthropological research into rituals and beliefs around death. “The Rat King of South London” is about her father’s sudden death from an abdominal aneurysm. An instantaneous death is a good one, she contends. More than 160,000 people die every day, and what to do with all those bodies is a serious question. A subversive sense of humour is there right from the start, as she gives a rundown of interment options. “Mummification: Beloved by Ancient Egyptians and small children going through their Ancient Egypt phase, it’s a classic for a reason!” Meanwhile, she legally owns her father’s plot so also buries dead pet rats there.

Like Erica Buist (This Party’s Dead) and Caitlin Doughty (Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, From Here to Eternity and Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs?), playwright Naomi Westerman finds the comical side of death. Part of 404 Ink’s Inklings series (“Big ideas, pocket-sized books” – perfect for anyone looking for short nonfiction for Novellas in November!), this is a collection of short essays about her own experiences of bereavement as well as her anthropological research into rituals and beliefs around death. “The Rat King of South London” is about her father’s sudden death from an abdominal aneurysm. An instantaneous death is a good one, she contends. More than 160,000 people die every day, and what to do with all those bodies is a serious question. A subversive sense of humour is there right from the start, as she gives a rundown of interment options. “Mummification: Beloved by Ancient Egyptians and small children going through their Ancient Egypt phase, it’s a classic for a reason!” Meanwhile, she legally owns her father’s plot so also buries dead pet rats there.

Other essays are about taking her mother’s ashes along on world travels, the funeral industry and “red market” sales of body parts, grief as a theme in horror films, the fetishization of dead female bodies, Mexico’s Day of the Dead festivities, and true crime obsession. In “Batman,” an excerpt from one of her plays, she goes to have a terrible cup of tea with the man she believes to be responsible for her mother’s death – a violent one, after leaving an abusive relationship. She also used the play to host an on-stage memorial for her mother since she wasn’t able to sit shiva. In the final title essay, Westerman tours lots of death cafés and finds comfort in shared experiences. These pieces are all breezy, amusing and easy to read, so it’s a shame that this small press didn’t achieve proper proofreading, making for a rather sloppy text, and that the content was overall too familiar for me.

With thanks to 404 Ink and publicist Claire Maxwell for the free copy for review.

Does one or more of these catch your eye?

What June releases can you recommend?

Someone becomes addicted to benzodiazepines in The Pass by Katriona Chapman and All the World Can Hold by Jung Yun (both 2026 releases).

Someone becomes addicted to benzodiazepines in The Pass by Katriona Chapman and All the World Can Hold by Jung Yun (both 2026 releases).

A sexual encounter between two men is presaged by them relieving themselves side by side at urinals in A Room Above a Shop by Anthony Shapland and The End of Mr Y by Scarlett Thomas.

A sexual encounter between two men is presaged by them relieving themselves side by side at urinals in A Room Above a Shop by Anthony Shapland and The End of Mr Y by Scarlett Thomas.

A character who startles very easily (in the last two cases because of PTSD) in Life before Man by Margaret Atwood, A History of Sound by Ben Shattuck, and Disconnected by Eleanor Vincent.

A character who startles very easily (in the last two cases because of PTSD) in Life before Man by Margaret Atwood, A History of Sound by Ben Shattuck, and Disconnected by Eleanor Vincent.

The author’s mother repeatedly asked her daughter a rhetorical question along the lines of “Do you know what I gave up to have you?” in Permission by Elissa Altman and Without Exception by Pam Houston.

The author’s mother repeatedly asked her daughter a rhetorical question along the lines of “Do you know what I gave up to have you?” in Permission by Elissa Altman and Without Exception by Pam Houston.

Hand was commissioned by Shirley Jackson’s estate to write a sequel to The Haunting of Hill House, which I read for R.I.P. in 2019 (

Hand was commissioned by Shirley Jackson’s estate to write a sequel to The Haunting of Hill House, which I read for R.I.P. in 2019 ( I’ve read all of Hurley’s novels (

I’ve read all of Hurley’s novels ( The second book of the “Sworn Soldier” duology, after

The second book of the “Sworn Soldier” duology, after  This teen comic series is not about literal ghosts but about mental health. Young people struggling with anxiety and intrusive thoughts recognize each other – they’ll be the ones wearing sheets with eye holes. In the first book, which

This teen comic series is not about literal ghosts but about mental health. Young people struggling with anxiety and intrusive thoughts recognize each other – they’ll be the ones wearing sheets with eye holes. In the first book, which  Cheri is an Amtrak ticket-taker who’s diagnosed with breast cancer in her mid-forties. After routine reconstructive surgery goes wrong and she’s left disabled, she returns to the Midwest and buys a home in Iowa. Here she’s supported by her best friends Linda and Wayne, and visited by her daughters Sarah and Katy. “Others have lived. She won’t be one of them. She feels it in her bones, quite literally.” When she hears the cancer has metastasized, she refuses treatment and starts making alternative plans. She’s philosophical about it; “Forty-six years is a long time if you look at it a certain way. Ursa is her seventh dog.”

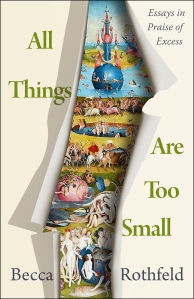

Cheri is an Amtrak ticket-taker who’s diagnosed with breast cancer in her mid-forties. After routine reconstructive surgery goes wrong and she’s left disabled, she returns to the Midwest and buys a home in Iowa. Here she’s supported by her best friends Linda and Wayne, and visited by her daughters Sarah and Katy. “Others have lived. She won’t be one of them. She feels it in her bones, quite literally.” When she hears the cancer has metastasized, she refuses treatment and starts making alternative plans. She’s philosophical about it; “Forty-six years is a long time if you look at it a certain way. Ursa is her seventh dog.” Rothfeld, the Washington Post’s nonfiction book reviewer, is on hiatus from a philosophy PhD at Harvard. Her academic background is clear from her vocabulary. The more accessible essays tend to be ones that were previously published in periodicals. Although the topics range widely – decluttering, true crime, consent, binge eating, online stalking – she’s assembled them under a dichotomy of parsimony versus indulgence. And you know from the title that she errs on the side of the latter. Luxuriate in lust, wallow in words, stick two fingers up to minimalism and mindfulness and be your own messy self. You might boil the message down to: Love what you love, because that’s what makes you an individual. And happy individuals – well, ideally, in an equal society that gives everyone the same access to self-fulfillment and art – make for a thriving culture. That, with some Barthes and Kant quotes.

Rothfeld, the Washington Post’s nonfiction book reviewer, is on hiatus from a philosophy PhD at Harvard. Her academic background is clear from her vocabulary. The more accessible essays tend to be ones that were previously published in periodicals. Although the topics range widely – decluttering, true crime, consent, binge eating, online stalking – she’s assembled them under a dichotomy of parsimony versus indulgence. And you know from the title that she errs on the side of the latter. Luxuriate in lust, wallow in words, stick two fingers up to minimalism and mindfulness and be your own messy self. You might boil the message down to: Love what you love, because that’s what makes you an individual. And happy individuals – well, ideally, in an equal society that gives everyone the same access to self-fulfillment and art – make for a thriving culture. That, with some Barthes and Kant quotes.