#MARM2024: Life before Man and Interlunar by Margaret Atwood

Hard to believe, but it’s my seventh year participating in the annual Margaret Atwood Reading Month (#MARM) hosted by indomitable Canadian blogger Marcie of Buried in Print. In previous years, I’ve read Surfacing and The Edible Woman, The Robber Bride and Moral Disorder, Wilderness Tips, The Door, and Bodily Harm and Stone Mattress; and reread The Blind Assassin. I’m wishing a happy belated birthday to Atwood, who turned 85 earlier this month. Novembers are my excuse to catch up on her extensive back catalogue. In recent years, I’ve scoured the university library holdings to find works by her that I often had never heard of, as was the case with this early novel and mid-career poetry collection.

Life before Man (1979)

Atwood’s fourth novel is from three rotating third-person POVs: Toronto museum curator Elizabeth, her toy-making husband Nate, and Lesje (pronounced “Lashia,” according to a note at the front), Elizabeth’s paleontologist colleague. The dated chapters span nearly two years, October 1976 to August 1978; often we visit with two or three protagonists on the same day. Elizabeth and Nate, parents to two daughters, have each had a string of lovers. Elizabeth’s most recent, Chris, has died by suicide. Nate disposes of his latest mistress, Martha, and replaces her with Lesje, who is initially confused by his interest in her. She’s more attracted to rocks and dinosaurs than to people, in a way that could be interpreted as consistent with neurodivergence.

Atwood’s fourth novel is from three rotating third-person POVs: Toronto museum curator Elizabeth, her toy-making husband Nate, and Lesje (pronounced “Lashia,” according to a note at the front), Elizabeth’s paleontologist colleague. The dated chapters span nearly two years, October 1976 to August 1978; often we visit with two or three protagonists on the same day. Elizabeth and Nate, parents to two daughters, have each had a string of lovers. Elizabeth’s most recent, Chris, has died by suicide. Nate disposes of his latest mistress, Martha, and replaces her with Lesje, who is initially confused by his interest in her. She’s more attracted to rocks and dinosaurs than to people, in a way that could be interpreted as consistent with neurodivergence.

It was neat to follow along seasonally with Halloween and Remembrance Day and so on, and see the Quebec independence movement simmering away in the background. To start with, I was engrossed in the characters’ perspectives and taken with Atwood’s witty descriptions and dialogue: “[Nate]’s heard Unitarianism called a featherbed for falling Christians” and (Lesje:) “Elizabeth needs support like a nun needs tits.” My favourite passage encapsulates a previous relationship of Lesje’s perfectly, in just the sort of no-nonsense language she would use:

The geologist had been fine; they could compromise on rock strata. They went on hikes with their little picks and kits, and chipped samples off cliffs; then they ate jelly sandwiches and copulated in a friendly way behind clumps of goldenrod and thistles. She found this pleasurable but not extremely so. She still has a collection of rock chips left over from this relationship; looking at it does not fill her with bitterness. He was a nice boy but she wasn’t in love with him.

Elizabeth’s formidable Auntie Muriel is a terrific secondary presence. But this really is just a novel about (repeated) adultery and its aftermath. The first line has Elizabeth thinking “I don’t know how I should live,” and after some complications, all three characters are trapped in a similar stasis by the end. By the halfway point I’d mostly lost interest and started skimming. The grief motif and museum setting weren’t the draws I’d expected them to be. Lesje is a promising character but, disappointingly, gets snared in clichéd circumstances. No doubt that is part of the point; “life before man” would have been better for her. (University library) ![]()

This prophetic passage from Life before Man leads nicely into the themes of Interlunar:

The real question is: Does [Lesje] care whether the human race survives or not? She doesn’t know. The dinosaurs didn’t survive and it wasn’t the end of the world. In her bleaker moments, … she feels the human race has it coming. Nature will think up something else. Or not, as the case may be.

The posthuman prospect is echoed in Interlunar in the lines: “Which is the sound / the earth will make for itself / without us. A stone echoing a stone.”

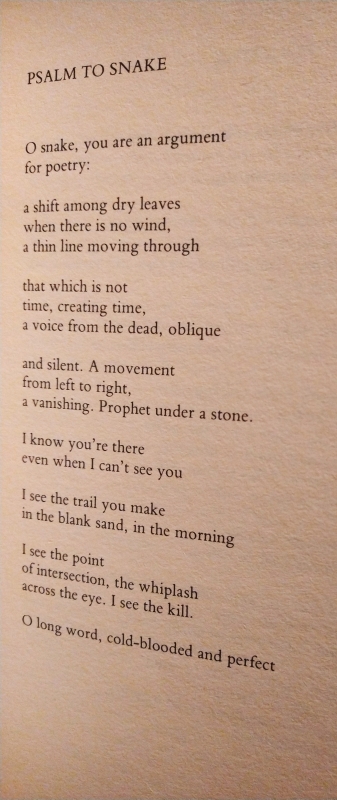

Interlunar (1984)

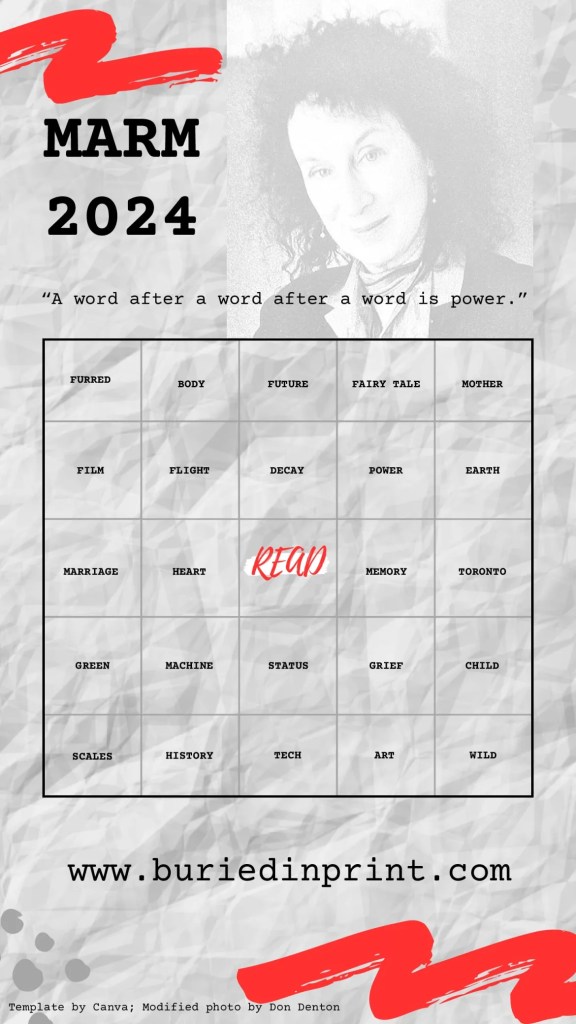

Some familiar Atwood elements in this volume, including death, mythology, nature, and stays at a lake house; you’ll even recognize a couple of her other works in poem titles “The Robber Bridegroom” and “The Burned House.” The opening set of “Snake Poems” got me the “green” and “scales” squares on Marcie’s Bingo card (in addition to various other scattered ones, I’m gonna say I’ve filled the whole right-hand column thanks to these two books).

This one brilliantly likens the creature to the sinuous ways of language:

“A Holiday” imagines a mother–daughter camping vacation presaging a postapocalyptic struggle for survival: “This could be where we / end up, learning the minimal / with maybe no tree, no rain, / no shelter, no roast carcasses / of animals to renew us … So far we do it / for fun.” As in her later collection The Door, portals and thresholds are of key importance. “Doorway” intones, “November is the month of entrance, / month of descent. Which has passed easily, / which has been lenient with me this year. / Nobody’s blood on the floor.” There are menace and melancholy here. But as “Orpheus (2)” suggests at its close, art can be an ongoing act of resistance: “To sing is either praise / or defiance. Praise is defiance.” I do recommend Atwood’s poetry if you haven’t tried it before, even if you’re not typically a poetry reader. Her poems are concrete and forceful, driven by imagery and voice; not as abstract as you might fear. Alas, I wasn’t sent a review copy of her collected poems, Paper Boat, as I’d hoped, but I will continue to enjoy encountering them piecemeal. (University library)

“A Holiday” imagines a mother–daughter camping vacation presaging a postapocalyptic struggle for survival: “This could be where we / end up, learning the minimal / with maybe no tree, no rain, / no shelter, no roast carcasses / of animals to renew us … So far we do it / for fun.” As in her later collection The Door, portals and thresholds are of key importance. “Doorway” intones, “November is the month of entrance, / month of descent. Which has passed easily, / which has been lenient with me this year. / Nobody’s blood on the floor.” There are menace and melancholy here. But as “Orpheus (2)” suggests at its close, art can be an ongoing act of resistance: “To sing is either praise / or defiance. Praise is defiance.” I do recommend Atwood’s poetry if you haven’t tried it before, even if you’re not typically a poetry reader. Her poems are concrete and forceful, driven by imagery and voice; not as abstract as you might fear. Alas, I wasn’t sent a review copy of her collected poems, Paper Boat, as I’d hoped, but I will continue to enjoy encountering them piecemeal. (University library) ![]()

Rathbones Folio Prize 2021 Shortlist Reviews & Prediction

I’ve nearly managed to read the whole Rathbones Folio Prize shortlist before the prize is announced on the evening of Wednesday the 24th. (You can sign up to watch the online ceremony here.) I reviewed the Baume and Ní Ghríofa as part of a Reading Ireland Month post on Saturday, and I’d reviewed the Machado last year in a feature on out-of-the-ordinary memoirs. This left another five books. Because they were short, I’ve been able to read and/or review another four over the past couple of weeks. (The only one unread is As You Were by Elaine Feeney, which I made a false start on last year and didn’t get a chance to try again.)

Nominations come from the Folio Academy, an international group of writers and critics, so the shortlisted authors have been chosen by an audience of their peers. Indeed, I kept spotting judges’ or fellow nominees’ names in the books’ acknowledgements or blurbs. I tried to think about the eight as a whole and generalize about what the judges were impressed by. This was difficult for such a varied set of books, but I picked out two unifying factors: A distinctive voice, often with a musicality of language – even the books that don’t include poetry per se are attentive to word choice; and timeliness of theme yet timelessness of experience.

Poor by Caleb Femi

Femi brings his South London housing estate to life through poetry and photographs. This is a place where young Black men get stopped by the police for any reason or none, where new trainers are a status symbol, where boys’ arrogant or seductive posturing hides fear. Everyone has fallen comrades, and things like looting make sense when they’re the only way to protest (“nothing was said about the maddening of grief. Nothing was said about loss & how people take and take to fill the void of who’s no longer there”). The poems range from couplets to prose paragraphs and are full of slang, Caribbean patois, and biblical patterns. I particularly liked Part V, modelled on scripture with its genealogical “begats” and a handful of portraits:

Femi brings his South London housing estate to life through poetry and photographs. This is a place where young Black men get stopped by the police for any reason or none, where new trainers are a status symbol, where boys’ arrogant or seductive posturing hides fear. Everyone has fallen comrades, and things like looting make sense when they’re the only way to protest (“nothing was said about the maddening of grief. Nothing was said about loss & how people take and take to fill the void of who’s no longer there”). The poems range from couplets to prose paragraphs and are full of slang, Caribbean patois, and biblical patterns. I particularly liked Part V, modelled on scripture with its genealogical “begats” and a handful of portraits:

The Story of Ruthless

Anyone smart enough

to study the food chain

of the estate knew exactly

who this warrior girl was;

once she lined eight boys

up against a wall,

emptied their pockets.

Nobody laughed at the boys.

Another that stood out for me was the two-part “A Designer Talks of Home / A Resident Talks of Home,” a found poem partially constructed from dialogue from a Netflix documentary on interior design. It ironically contrasts airy aesthetic notions with survival in a concrete wasteland. If you loved Surge by Jay Bernard, this should be next on your list.

My Darling from the Lions by Rachel Long

I first read this when it was on the Costa Awards shortlist. As in Femi’s collection, race, sex, and religion come into play. The focus is on memories of coming of age, with the voice sometimes a girl’s and sometimes a grown woman’s. Her course veers between innocence and hazard. She must make her way beyond the world’s either/or distinctions and figure out how to be multiple people at once (biracial, bisexual). Her Black mother is a forceful presence; “Red Hoover” is a funny account of trying to date a Nigerian man to please her mother. Much of the rest of the book failed to click with me, but the experience of poetry is so subjective that I find it hard to give any specific reasons why that’s the case.

I first read this when it was on the Costa Awards shortlist. As in Femi’s collection, race, sex, and religion come into play. The focus is on memories of coming of age, with the voice sometimes a girl’s and sometimes a grown woman’s. Her course veers between innocence and hazard. She must make her way beyond the world’s either/or distinctions and figure out how to be multiple people at once (biracial, bisexual). Her Black mother is a forceful presence; “Red Hoover” is a funny account of trying to date a Nigerian man to please her mother. Much of the rest of the book failed to click with me, but the experience of poetry is so subjective that I find it hard to give any specific reasons why that’s the case.

The Mermaid of Black Conch by Monique Roffey

After the two poetry entries on the shortlist, it’s on to a book that, like A Ghost in the Throat, incorporates poetry in a playful but often dark narrative. In 1976, two competitive American fishermen, a father-and-son pair down from Florida, catch a mermaid off of the fictional Caribbean island of Black Conch. Like trophy hunters, the men take photos with her; they feel a mixture of repulsion and sexual attraction. Is she a fish, or an object of desire? In the recent past, David Baptiste recalls what happened next through his journal entries. He kept the mermaid, Aycayia, in his bathtub and she gradually shed her tail and turned back into a Taino indigenous woman covered in tattoos and fond of fruit. Her people were murdered and abused, and the curse that was placed on her runs deep, threatening to overtake her even as she falls in love with David. This reminded me of Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea and Lydia Millet’s Mermaids in Paradise. I loved that Aycayia’s testimony was delivered in poetry, but this short, magical story came and went without leaving any impression on me.

After the two poetry entries on the shortlist, it’s on to a book that, like A Ghost in the Throat, incorporates poetry in a playful but often dark narrative. In 1976, two competitive American fishermen, a father-and-son pair down from Florida, catch a mermaid off of the fictional Caribbean island of Black Conch. Like trophy hunters, the men take photos with her; they feel a mixture of repulsion and sexual attraction. Is she a fish, or an object of desire? In the recent past, David Baptiste recalls what happened next through his journal entries. He kept the mermaid, Aycayia, in his bathtub and she gradually shed her tail and turned back into a Taino indigenous woman covered in tattoos and fond of fruit. Her people were murdered and abused, and the curse that was placed on her runs deep, threatening to overtake her even as she falls in love with David. This reminded me of Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea and Lydia Millet’s Mermaids in Paradise. I loved that Aycayia’s testimony was delivered in poetry, but this short, magical story came and went without leaving any impression on me.

Indelicacy by Amina Cain

Having heard that this was about a cleaner at an art museum, I expected it to be a readalike of Asunder by Chloe Aridjis, a beautifully understated tale of ghostly perils faced by a guard at London’s National Gallery. Indelicacy is more fable-like. Vitória’s life is in two halves: when she worked at the museum and had to forego meals to buy new things, versus after she met her rich husband and became a writer. Increasingly dissatisfied with her marriage, she then comes up with an escape plot involving her hostile maid. Meanwhile, she makes friends with a younger ballet student and keeps in touch with her fellow cleaner, Antoinette, a pregnant newlywed. Vitória tries sex and drugs to make her feel something. Refusing to eat meat and trying to persuade Antoinette not to baptize her baby become her peculiar twin campaigns.

Having heard that this was about a cleaner at an art museum, I expected it to be a readalike of Asunder by Chloe Aridjis, a beautifully understated tale of ghostly perils faced by a guard at London’s National Gallery. Indelicacy is more fable-like. Vitória’s life is in two halves: when she worked at the museum and had to forego meals to buy new things, versus after she met her rich husband and became a writer. Increasingly dissatisfied with her marriage, she then comes up with an escape plot involving her hostile maid. Meanwhile, she makes friends with a younger ballet student and keeps in touch with her fellow cleaner, Antoinette, a pregnant newlywed. Vitória tries sex and drugs to make her feel something. Refusing to eat meat and trying to persuade Antoinette not to baptize her baby become her peculiar twin campaigns.

The novella belongs to no specific time or place; while Cain lives in Los Angeles, this most closely resembles ‘wan husks’ of European autofiction in translation. Vitória issues pretentious statements as flat as the painting style she claims to love. Some are so ridiculous they end up being (perhaps unintentionally) funny: “We weren’t different from the cucumber, the melon, the lettuce, the apple. Not really.” The book’s most extraordinary passage is her husband’s rambling, defensive monologue, which includes the lines “You’re like an old piece of pie I can’t throw away, a very good pie. But I rescued you.”

It seems this has been received as a feminist story, a cheeky parable of what happens when a woman needs a room of her own but is trapped by her social class. When I read in the Acknowledgements that Cain took lines and character names from Octavia E. Butler, Jean Genet, Clarice Lispector, and Jean Rhys, I felt cheated, as if the author had been engaged in a self-indulgent writing exercise. This was the shortlisted book I was most excited to read, yet ended up being the biggest disappointment.

On the whole, the Folio shortlist ended up not being particularly to my taste this year, but I can, at least to an extent, appreciate why these eight books were considered worthy of celebration. The authors are “writers’ writers” for sure, though in some cases that means they may fail to connect with readers. There was, however, some crossover this year with some more populist prizes like the Costa Awards (Roffey won the overall Costa Book of the Year).

The crystal-clear winner for me is In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado, her memoir of an abusive same-sex relationship. Written in the second person and in short sections that examine her memories from different angles, it’s a masterpiece and a real game changer for the genre – which I’m sure is just what the judges are looking for.

The only book on the shortlist that came anywhere close to this one, for me, was A Ghost in the Throat by Doireann Ní Ghríofa, an elegant piece of feminist autofiction that weaves in biography, imagination, and poetry. It would be a fine runner-up choice.

(On the Rathbones Folio Prize Twitter account, you will find lots of additional goodies like links to related articles and interviews, and videos with short readings from each author.)

My thanks to the publishers and FMcM Associates for the free copies for review.

A Keeper of Records: What’s Worth Saving?

It’s safe to say that book bloggers love lists: not only do we keep a thorough list of everything we read in a year, but we also leap to check out every new top 5/10/50/100 or thematic book list that’s posted so we can see how many of them we’ve read. And then, at the end of any year, most of us put together our own best-of lists, often for a number of categories.

When I was younger, though, I took the list-making to an extreme. As I was going back through boxes of mementos in America a few weeks ago, I found stacks of hand-written records I’d kept. Here’s a list of what I used to list:

- every book I read

- every movie I saw

- dreams, recounted in detail

- money I found on the ground

- items I bought or sold on eBay

- gifts given or received for birthdays and Christmas

- transactions made through my mail-order music club

- all my weekday outfits, with a special shorthand designating each item of clothing

Age 14 (1997-8) was the peak of my record-keeping, and the only year when I faithfully kept a diary. I cringe to look back at all this now. Most of the dreams are populated by my crushes of the time, names and faces that mean nothing to me now. And to think that I was so self-conscious and deluded to assume people at school might notice if I wore a shirt twice within a couple of weeks! My diary isn’t particularly illuminating from this distance, either; mostly it brings back how earnest and pious I was in my teens. It’s occasionally addressed in the second person, as if to an imaginary bosom friend who would know me as well as I knew myself.

What’s clear is that I was convinced that the minutiae of my life mattered. Between us, my mother and I had kept a huge cache of my schoolwork and craft projects from kindergarten right through graduate school. I was also a devoted collector – of stamps, coins, figurines, tea sets, shells, anything with puffins or llamas – so I obviously felt that physical objects had real importance, too. It’s a wonder I didn’t become an archivist or a museum curator.

Why did I save all this stuff in the first place? Even as a teen, was I imagining an illustrious career for myself and some future biographer who would gleefully mine my records and personal writings for clues to who I really was? I’m not sure whether to admire the confidence or deplore the presumption. We all want to believe we’re living lives of significance, but when I take a long view – if I never have a child … if I never publish a book (though I think I will) … if human society does indeed collapse by 2050 (as some are predicting) – it’s hard to see what, if anything, will be preserved of my time on earth.

This is deeper than I usually get in a blog post, but these are the sorts of thoughts that preoccupy me when I’m not just drifting along in life’s routines. My nieces’ and nephews’ generation may be the last to inhabit this planet if we don’t take drastic and immediate action to deal with the environmental crisis. Many are working for change (my husband, a new Town Councillor, recently voted for the successful motion to declare a climate emergency and commit Newbury to going carbon-neutral by 2030), but some remain ignorant that there is any kind of problem and so consume and dispose like there is (literally) no tomorrow.

My home is a comfortable bubble I hardly ever leave, but more and more I feel that I need to become part of larger movements: first to ensure the continuation of human and non-human existence; then to improve the quality of human life, especially for those who have contributed least to climate change but will suffer the most from it. I have no idea what form my participation should take, but I know that focusing on outside causes will mean less time obsessing about myself and my inconsequential problems.

That’s not to say I won’t listen to the angst that’s telling me I’m not living my life as fully as I should, but I know that working with others, in whatever way, to tackle global issues will combat the lack of purpose that’s been plaguing me for years.

Appreciation for my past can only help with bolstering a healthy self-image, so I’ve kept a small selection of all those records, and a larger batch of school essays and assignments. Even if this archive is only ever for me, I like being able to look back at the well-rounded student I was – I used to get perfect scores on calculus tests and chemistry lab reports! I could write entire papers in French! – and see the seeds of the sincere, meticulous book lover I still am. As Eve Schaub writes in Year of No Clutter, “I’m not about to stop collecting my own life. It has been a source of pleasure for me ever since I can remember; it helps define me.”

A selection of favorite mementos I discovered back in the States:

In high school I started making my way through the American Film Institute’s list of Top 100 movies. I’ve now seen 89 of them.

I kept a list of new vocabulary words encountered in novels, especially Victorian ones. Note trumpery: (noun) attractive articles of little value or use; (adjective) showy but worthless – how apt!

As a high school senior, I waded through Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead to write an essay that won me an honorable mention, a point of interest on my college applications. Though I find it formulaic now, it’s a precursor to a career partially devoted to writing about books.

I planned my every college paper via incredibly detailed outlines. (I’m far too lazy to do this for book reviews now!) Can you work out what these essays were about?

As a college sophomore I wrote weekly essays in what looks like pretty flawless French. This one was an imagined interview with Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy about the autobiographical and religious influences on their fiction.

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See: Travels among the Collectors of Iceland by A. Kendra Greene (2020) – This sounded quirky and fun, but it turns out it was too niche for me. I read the first two “Galleries” (78 pp.) about the Icelandic Phallological Museum and one woman’s stone collection. Another writer might have used a penis museum as an excuse for lots of cheap laughs, but Greene doesn’t succumb. Still, “no matter how erudite or innocent you imagine yourself to be, you will discover that everything is funnier when you talk about a penis museum. … It’s not salacious. It’s not even funny, except that the joke is on you.” I think I might have preferred a zany Sarah Vowell approach to the material. (Secondhand – Bas Books and Home, Newbury)

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See: Travels among the Collectors of Iceland by A. Kendra Greene (2020) – This sounded quirky and fun, but it turns out it was too niche for me. I read the first two “Galleries” (78 pp.) about the Icelandic Phallological Museum and one woman’s stone collection. Another writer might have used a penis museum as an excuse for lots of cheap laughs, but Greene doesn’t succumb. Still, “no matter how erudite or innocent you imagine yourself to be, you will discover that everything is funnier when you talk about a penis museum. … It’s not salacious. It’s not even funny, except that the joke is on you.” I think I might have preferred a zany Sarah Vowell approach to the material. (Secondhand – Bas Books and Home, Newbury) Because I Don’t Know What You Mean and What You Don’t by Josie Long (2023) – A free signed copy – and, if I’m honest, a cover reminiscent of Ned Beauman’s Glow – induced me to try an author I’d never heard of. She’s a stand-up comic, apparently, not that you’d know it from these utterly boring, one-note stories about unhappy adolescents and mums on London council estates. I read 108 pages but could barely tell you what a single story was about. Long is decent at voices, but you need compelling stories to house them. (Little Free Library)

Because I Don’t Know What You Mean and What You Don’t by Josie Long (2023) – A free signed copy – and, if I’m honest, a cover reminiscent of Ned Beauman’s Glow – induced me to try an author I’d never heard of. She’s a stand-up comic, apparently, not that you’d know it from these utterly boring, one-note stories about unhappy adolescents and mums on London council estates. I read 108 pages but could barely tell you what a single story was about. Long is decent at voices, but you need compelling stories to house them. (Little Free Library) Cyrus Shams is an Iranian American aspiring poet who grew up in Indiana with a single father, his mother Roya having died in a passenger aircraft mistakenly shot down by a U.S. Navy missile cruiser (this really happened: Iran Air Flight 655, on 3 July 1988). He continues to lurk around the Keady University campus, working as a medical actor at the hospital, but his ambition is to write. During his shaky recovery from drug and alcohol abuse, he undertakes a project that seems divinely inspired: “Tired of interventionist pyrotechnics like burning bushes and locust plagues, maybe God now worked through the tired eyes of drunk Iranians in the American Midwest”. By seeking the meaning in others’ deaths, he hopes his modern “Book of Martyrs” will teach him how to cherish his own life.

Cyrus Shams is an Iranian American aspiring poet who grew up in Indiana with a single father, his mother Roya having died in a passenger aircraft mistakenly shot down by a U.S. Navy missile cruiser (this really happened: Iran Air Flight 655, on 3 July 1988). He continues to lurk around the Keady University campus, working as a medical actor at the hospital, but his ambition is to write. During his shaky recovery from drug and alcohol abuse, he undertakes a project that seems divinely inspired: “Tired of interventionist pyrotechnics like burning bushes and locust plagues, maybe God now worked through the tired eyes of drunk Iranians in the American Midwest”. By seeking the meaning in others’ deaths, he hopes his modern “Book of Martyrs” will teach him how to cherish his own life.

This is the third C-PTSD memoir I’ve read (after

This is the third C-PTSD memoir I’ve read (after