Some 2025 Reading Superlatives

Longest book read this year: The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese (724 pages)

Shortest book read this year: Sky Tongued Back with Light by Sébastien Luc Butler (a 38-page poetry chapbook coming out in 2026)

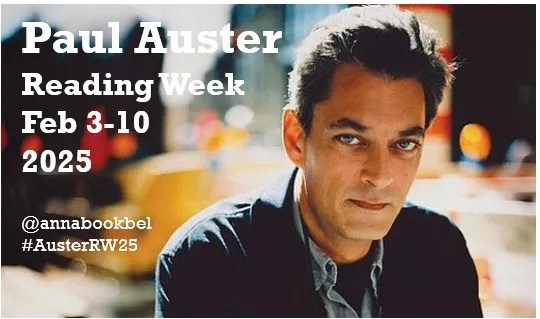

Authors I read the most by this year: Paul Auster and Emma Donoghue (3) [followed by Margaret Atwood, Chloe Caldwell, Michael Cunningham, Mairi Hedderwick, Christopher Isherwood, Rebecca Kauffman, Stephen King, Elaine Kraf, Maggie O’Farrell, Sylvia Plath and Jess Walter (2 each)]

Publishers I read the most from: (Besides the ubiquitous Penguin Random House and its myriad imprints) Faber (14), Canongate (12), Bloomsbury (11), Fourth Estate (7); Carcanet, Picador/Pan Macmillan and Virago (6)

My top author ‘discoveries’ of the year (I’m very late to the party on some of these!): poet Amy Gerstler, Christopher Isherwood, Stephen King, Elaine Kraf, Sylvia Plath, Chloe Savage’s children’s picture books (women + NB characters, science, adventure, dogs), Robin Stevens’s middle-grade mysteries, Jess Walter

Proudest book-related achievement: Clearing 90–100 books from my shelves as part of our hallway redecoration. Some I resold, some I gave to friends, some I put in the Little Free Library, and some I donated to charity shops.

Most pinching-myself bookish moment: Miriam Toews’ U.S. publicist e-mailing me about my Shelf Awareness review of A Truce That Is Not Peace to say, “saw your amazing review! Thank you so much for it – Miriam loved it!”

Books that made me laugh: LOTS, including Spent by Alison Bechdel (which I read twice), The Wedding People by Alison Espach, Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito, Is This My Final Form? by Amy Gerstler, The Diary of a Nobody by George Grossmith, The Sacred Diary of Adrian Plass Aged 37 ¾, and Slags by Emma Jane Unsworth

A book that made me cry: Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry

Best book club selections: Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam; The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro, I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O’Farrell and Stoner by John Williams (these three were all rereads)

Best first line encountered this year:

- From Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones: “Hard, ugly, summer-vacation-spoiling rain fell for three straight months in 1979.”

Best last lines encountered this year:

- Is a River Alive? by Robert Macfarlane: “Death and love and life, all mingled in the flow.”

(Two quite similar rhetorical questions:)

Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam: “If they didn’t know how it would end—with night, with more terrible noise from the top of Olympus, with bombs, with disease, with blood, with happiness, with deer or something else watching them from the darkened woods—well, wasn’t that true of every day?”

Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam: “If they didn’t know how it would end—with night, with more terrible noise from the top of Olympus, with bombs, with disease, with blood, with happiness, with deer or something else watching them from the darkened woods—well, wasn’t that true of every day?”

&

- Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter: “And even if they don’t find what they’re looking for, isn’t it enough to be out walking together in the sunlight?”

- Wreck by Catherine Newman: “You are still breathing.”

The Irish Goodbye by Beth Ann Fennelly: “Dear viewer of my naked body, Enjoy the bunions.”

The Irish Goodbye by Beth Ann Fennelly: “Dear viewer of my naked body, Enjoy the bunions.”

- A Certain Smile by Françoise Sagan: “It was a simple story; there was nothing to make a fuss about.”

- Book of Lives by Margaret Atwood: “We scribes and scribblers are time travellers: via the magic page we throw our voices, not only from here to elsewhere, but also from now to a possible future. I’ll see you there.”

Book that put a song in my head every time I picked it up: The Harvest Gypsies by John Steinbeck (see Kris Drever’s song of the same name). Also, one story of Book of Exemplary Women by Diana Xin mentioned lyrics from “Wild World” by Cat Stevens (“Oh, baby, baby, it’s a wild world. And I’ll always remember you like a child, girl”).

Shortest book titles encountered: Pan (Michael Clune), followed by Gold (Elaine Feinstein) & Girl (Ruth Padel); followed by an 8-way tie! Spent (Alison Bechdel), Billy (Albert French), Carol (Patricia Highsmith), Pluck (Adam Hughes), Sleep (Honor Jones), Wreck (Catherine Newman), Ariel (Sylvia Plath) & Flesh (David Szalay)

Best 2025 book titles: Chopping Onions on My Heart by Samantha Ellis [retitled, probably sensibly, Always Carry Salt for its U.S. release], A Truce That Is Not Peace by Miriam Toews [named after a line from a Christian Wiman poem – top taste there] & Calls May Be Recorded for Training and Monitoring Purposes by Katharina Volckmer.

Best book titles from other years: Dreams of Dead Women’s Handbags by Shena Mackay

Biggest disappointments: Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie – so not worth waiting 12 years for – and Heart the Lover by Lily King, which kind of retrospectively ruined her brilliant Writers & Lovers for me.

The 2025 books that it seemed like everyone was reading but I decided not to: Helm by Sarah Hall, The Persians by Sanam Mahloudji, What We Can Know by Ian McEwan (I’m 0 for 2 on his 2020s releases)

The downright strangest books I read this year: Both by Elaine Kraf: I Am Clarence and Find Him! (links to my Shelf Awareness reviews) are confusing, disturbing, experimental in language and form, but also ahead of their time in terms of their feminist content and insight into compromised mental states. The former is more accessible and less claustrophobic.

20 Books of Summer, 17–18: Suzanne Berne and Melissa Febos

Nearly there! I’ll have two more books to review for this challenge as part of roundups tomorrow and Saturday. Today I have a lesser-known novel by a Women’s Prize winner and a set of personal essays about body image and growing up female.

A Perfect Arrangement by Suzanne Berne (2001)

Berne won the Orange (Women’s) Prize for A Crime in the Neighbourhood in 1999. This is another slice of mild suburban suspense. The Boston-area Cook-Goldman household faces increasingly disruptive problems. Architect dad Howard is vilified for a new housing estate he’s planning, plus an affair that he had with a colleague a few years ago comes back to haunt him. Hotshot lawyer Mirella can’t get the work–life balance right, especially when she finds out she’s unexpectedly pregnant with twins at age 41. They hire a new nanny to wrangle their two under-fives, headstrong Pearl and developmentally delayed Jacob. If Randi Gill seems too good to be true, that’s because she’s a pathological liar. But hey, she’s great with kids.

Berne won the Orange (Women’s) Prize for A Crime in the Neighbourhood in 1999. This is another slice of mild suburban suspense. The Boston-area Cook-Goldman household faces increasingly disruptive problems. Architect dad Howard is vilified for a new housing estate he’s planning, plus an affair that he had with a colleague a few years ago comes back to haunt him. Hotshot lawyer Mirella can’t get the work–life balance right, especially when she finds out she’s unexpectedly pregnant with twins at age 41. They hire a new nanny to wrangle their two under-fives, headstrong Pearl and developmentally delayed Jacob. If Randi Gill seems too good to be true, that’s because she’s a pathological liar. But hey, she’s great with kids.

It’s clear some Bad Stuff is going to happen to this family; the only questions are how bad and precisely what. Now, this is pretty much exactly what I want from my “summer reading”: super-readable plot- and character-driven fiction whose stakes are low (e.g., midlife malaise instead of war or genocide or whatever) and that veers more popular than literary and so can be devoured in large chunks. I really should have built more of that into my 20 Books plan! I read this much faster than I normally get through a book, but that meant the foreshadowing felt too prominent and I noticed some repetition, e.g., four or five references to purple loosestrife, which is a bit much even for those of us who like our wildflowers. It seemed a bit odd that the action was set back in the Clinton presidency; the references to the Lewinsky affair and Hillary’s “baking cookies” remark seemed to come out of nowhere. And seriously, why does the dog always have to suffer the consequences of humans’ stupid mistakes?!

This reminded me most of Friends and Strangers by J. Courtney Sullivan and a bit of Breathing Lessons by Anne Tyler, while one late plot turn took me right back to The Senator’s Wife by Sue Miller. While the Goodreads average rating of 2.93 seems pretty harsh, I can also see why fans of A Crime would have been disappointed. I probably won’t seek out any more of Berne’s fiction. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

Girlhood by Melissa Febos (2021)

I was deeply impressed by Febos’s Body Work (2022), a practical guide to crafting autobiographical narratives as a way of reckoning with the effects of trauma. Ironically, I engaged rather less with her own personal essays. One issue for me was that her highly sexualized experiences are a world away from mine. I don’t have her sense of always having had to perform for the male gaze, though maybe I’m fooling myself. Another was that it’s over 300 pages and only contains seven essays, so there were several pieces that felt endless. This was especially true of “The Mirror Test” (62 pp.) which is about double standards for girls as they played out in her simultaneous lack of confidence and slutty reputation, but randomly references The House of Mirth quite a lot; and “Thank You for Taking Care of Yourself” (74 pp.), which ponders why Febos has such trouble relaxing at a cuddle party and whether she killed off her ability to give physical consent through her years as a dominatrix.

“Wild America,” about her first lesbian experience and the way she came to love a perceived defect (freakishly large hands; they look perfectly normal to me in her author photo), and “Intrusions,” about her and other women’s experience with stalkers, worked a bit better. But my two favourites incorporated travel, a specific relationship, and a past versus present structure. “Thesmophoria” opens with her arriving in Rome for a mother–daughter vacation only to realize she told her mother the wrong month. Feeling guilty over the error, she remembers other instances when she valued her mother’s forgiveness, including when she would leave family celebrations to buy drugs. The allusions to Greek myth were neither here nor there for me, but the words about her mother’s unconditional love made me cry.

“Wild America,” about her first lesbian experience and the way she came to love a perceived defect (freakishly large hands; they look perfectly normal to me in her author photo), and “Intrusions,” about her and other women’s experience with stalkers, worked a bit better. But my two favourites incorporated travel, a specific relationship, and a past versus present structure. “Thesmophoria” opens with her arriving in Rome for a mother–daughter vacation only to realize she told her mother the wrong month. Feeling guilty over the error, she remembers other instances when she valued her mother’s forgiveness, including when she would leave family celebrations to buy drugs. The allusions to Greek myth were neither here nor there for me, but the words about her mother’s unconditional love made me cry.

I also really liked “Les Calanques,” which again draws on her history of heroin addiction, comparing a strung-out college trip to Paris when she scored with a sweet gay boy named Ahmed with the self-disciplined routines and care for her body she’d learned by the time she returns to France for a writing retreat. This felt like a good model for how to write about one’s past self. “I spend so much time with that younger self, her savage despair and fleeting reliefs, that I start to feel as though she is here with me.” The prologue, “Scarification,” is a numbered list of how she got her scars, something Paul Auster also gives in Winter Journal. As if to insist that we can only ever experience life through our bodies.

Although I’d hoped to connect to this more, and ultimately felt it wasn’t really meant for me (and maybe I’m a deficient feminist), I did admire the range of strategies and themes so will keep it on the shelf as a model for approaching the art of the personal essay. I think I would probably prefer a memoir from Febos, but don’t need to read more about her sex work (Whip Smart), so might look into Abandon Me. If bisexuality and questions of consent are of interest, you might also like Another Word for Love by Carvell Wallace, which I reviewed for BookBrowse. (Gift (secondhand) from my Christmas wish list last year) ![]()

Book Serendipity, May to June 2021

I call it Book Serendipity when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something pretty bizarre in common. Because I have so many books on the go at once (usually 20‒30), I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. I’ve realized that, of course, synchronicity is really the more apt word, but this branding has stuck.

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Sufjan Stevens songs are mentioned in What Is a Dog? by Chloe Shaw and After the Storm by Emma Jane Unsworth.

- There’s a character with two different coloured eyes in The Mothers by Brit Bennett and Painting Time by Maylis de Kerangal.

- A description of a bathroom full of moisturizers and other ladylike products in The Mothers by Brit Bennett and The Interior Silence by Sarah Sands.

- A description of having to saw a piece of furniture in half to get it in or out of a room in A Braided Heart by Brenda Miller and After the Storm by Emma Jane Unsworth.

- The main character is named Esther Greenwood in the Charlotte Perkins Gilman short story “The Unnatural Mother” in the anthology Close Company and The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath. Indeed, it seems Plath may have taken her protagonist’s name from the 1916 story. What a find!

- Reading two memoirs of being in a coma for weeks and on a ventilator, with a letter or letters written by the hospital staff: Many Different Kinds of Love by Michael Rosen and Coma by Zara Slattery.

- Reading two memoirs that mention being in hospital in Brighton: Coma by Zara Slattery and After the Storm by Emma Jane Unsworth.

- Reading two books with a character named Tam(b)lyn: My Cousin Rachel by Daphne du Maurier and Coma by Zara Slattery.

- A character says that they don’t miss a person who’s died so much as they miss the chance to have gotten to know them in Featherhood by Charlie Gilmour and In by Will McPhail.

- A man finds used condoms among his late father’s things in The Invention of Solitude by Paul Auster and Featherhood by Charlie Gilmour.

- An absent husband named David in Open House by Elizabeth Berg and Ruby by Ann Hood.

- The murder of Thomas à Becket featured in Murder in the Cathedral by T.S. Eliot (read in April) and Heavy Time by Sonia Overall (read in June).

- Adrienne Rich is quoted in (M)otherhood by Pragya Agarwal and Heavy Time by Sonia Overall.

- A brother named Danny in Immediate Family by Ashley Nelson Levy and Saint Maybe by Anne Tyler.

- The male lead is a carpenter in Early Morning Riser by Katherine Heiny and Saint Maybe by Anne Tyler.

- An overbearing, argumentative mother who is a notably bad driver in Early Morning Riser by Katherine Heiny and Blue Shoe by Anne Lamott.

- That dumb 1989 movie Look Who’s Talking is mentioned in (M)otherhood by Pragya Agarwal and Early Morning Riser by Katherine Heiny.

- In the same evening, I started two novels that open in 1983, the year of my birth: The Other Black Girl by Zakiya Dalila Harris and Malibu Rising by Taylor Jenkins Reid.

- “Autistic” is used as an unfortunate metaphor for uncontrollable or fearful behavior in Open House by Elizabeth Berg and Blue Shoe by Anne Lamott (from 2000 and 2002, so they’re dated references rather than mean-spirited ones).

A secondary character mentions a bad experience in a primary school mathematics class as being formative to their later life in Blue Shoe by Anne Lamott and Saint Maybe by Anne Tyler (at least, I think it was in the Tyler; I couldn’t find the incident when I went back to look for it. I hope Liz will set me straight!).

A secondary character mentions a bad experience in a primary school mathematics class as being formative to their later life in Blue Shoe by Anne Lamott and Saint Maybe by Anne Tyler (at least, I think it was in the Tyler; I couldn’t find the incident when I went back to look for it. I hope Liz will set me straight!).

- The panopticon and Foucault are referred to in Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead and I Live a Life Like Yours by Jan Grue. Specifically, Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon is the one mentioned in the Shipstead, and Bentham appears in The Cape Doctor by E.J. Levy.

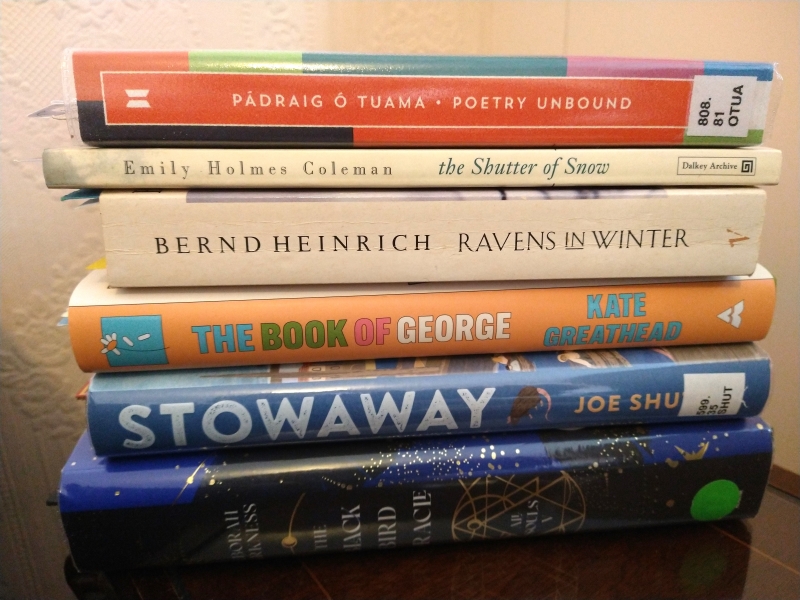

The protagonist is mistaken for a two-year-old boy’s father in The Book of George by Kate Greathead and Going Home by Tom Lamont.

The protagonist is mistaken for a two-year-old boy’s father in The Book of George by Kate Greathead and Going Home by Tom Lamont.

Adults dressing up for Halloween in The Blindfold by Siri Hustvedt and I’ll Come to You by Rebecca Kauffman.

Adults dressing up for Halloween in The Blindfold by Siri Hustvedt and I’ll Come to You by Rebecca Kauffman.

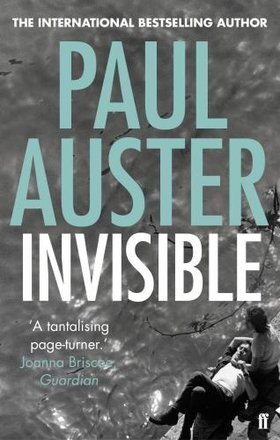

The main character is expelled on false drug possession charges in Invisible by Paul Auster and Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez.

The main character is expelled on false drug possession charges in Invisible by Paul Auster and Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez.

A scene of a teacup breaking in Junction of Earth and Sky by Susan Buttenwieser and The Möbius Book by Catherine Lacey.

A scene of a teacup breaking in Junction of Earth and Sky by Susan Buttenwieser and The Möbius Book by Catherine Lacey.

Baumgartner’s past is similar to Auster’s (and Adam Walker’s from Invisible – the two characters have a mutual friend in writer James Freeman), but not identical. His childhood memories and the passion and companionship he found with Anna are quite sweet. But I was somewhat thrown by the tone in sections that have this grumpy older man experiencing pseudo-comic incidents such as tumbling down the stairs while showing the meter reader the way. To my relief, the book doesn’t take the tragic turn the last pages seem to augur, instead leaving readers with a nicely open ending.

Baumgartner’s past is similar to Auster’s (and Adam Walker’s from Invisible – the two characters have a mutual friend in writer James Freeman), but not identical. His childhood memories and the passion and companionship he found with Anna are quite sweet. But I was somewhat thrown by the tone in sections that have this grumpy older man experiencing pseudo-comic incidents such as tumbling down the stairs while showing the meter reader the way. To my relief, the book doesn’t take the tragic turn the last pages seem to augur, instead leaving readers with a nicely open ending. This is very much in the vein of

This is very much in the vein of

That’s at the heart of Part I (“Spring”). Across four sections, the perspective changes and the narrative is revealed to be 1967, a manuscript Adam began while dying of cancer. “Summer,” in the second person, shines a light on his relationship with his sister, Gwyn. “Fall,” adapted from Adam’s third-person notes by his college friend and fellow author, Jim Freeman, tells of Adam’s study abroad term in Paris. Here he reconnected with Born and Margot with unexpected results. Jim intends to complete the anonymized story with the help of a minor character’s diary, but the challenge is that Adam’s memories don’t match Gwyn’s or Born’s.

That’s at the heart of Part I (“Spring”). Across four sections, the perspective changes and the narrative is revealed to be 1967, a manuscript Adam began while dying of cancer. “Summer,” in the second person, shines a light on his relationship with his sister, Gwyn. “Fall,” adapted from Adam’s third-person notes by his college friend and fellow author, Jim Freeman, tells of Adam’s study abroad term in Paris. Here he reconnected with Born and Margot with unexpected results. Jim intends to complete the anonymized story with the help of a minor character’s diary, but the challenge is that Adam’s memories don’t match Gwyn’s or Born’s. Iris Vegan (Hustvedt’s mother’s surname), like many an Auster character, is bewildered by what happens to her. An impoverished graduate student in literature, she takes on peculiar jobs. First Mr. Morning hires her to make audio recordings meticulously describing artefacts of a woman he’s obsessed with. Iris comes to believe this woman was murdered and rejects the work as invasive. Next she’s a photographer’s model but hates the resulting portrait and tries to take it off display. Then she’s hospitalized for terrible migraines and has upsetting encounters with a fellow patient, old Mrs. O. Finally, she translates a bizarre German novella and impersonates its protagonist, walking the streets in a shabby suit and even telling people her name is Klaus.

Iris Vegan (Hustvedt’s mother’s surname), like many an Auster character, is bewildered by what happens to her. An impoverished graduate student in literature, she takes on peculiar jobs. First Mr. Morning hires her to make audio recordings meticulously describing artefacts of a woman he’s obsessed with. Iris comes to believe this woman was murdered and rejects the work as invasive. Next she’s a photographer’s model but hates the resulting portrait and tries to take it off display. Then she’s hospitalized for terrible migraines and has upsetting encounters with a fellow patient, old Mrs. O. Finally, she translates a bizarre German novella and impersonates its protagonist, walking the streets in a shabby suit and even telling people her name is Klaus.

This was a cute read about two little girls helping their father in the garden and discovering the natural wonders of the season, like tadpoles in a pond, birds building nests, and insects and worms in the compost heap. A section at the end gives more information about the science of spring – unfortunately, it mislabels one bird and includes North American species without labelling them as such, whereas the rest of the book was clearly set in the UK. The strategy reminded me of that in Wild Child by Dara McAnulty. This year is the first time a children’s book Wainwright Prize will be awarded, so we’ll see this kind of book being recognized more.

This was a cute read about two little girls helping their father in the garden and discovering the natural wonders of the season, like tadpoles in a pond, birds building nests, and insects and worms in the compost heap. A section at the end gives more information about the science of spring – unfortunately, it mislabels one bird and includes North American species without labelling them as such, whereas the rest of the book was clearly set in the UK. The strategy reminded me of that in Wild Child by Dara McAnulty. This year is the first time a children’s book Wainwright Prize will be awarded, so we’ll see this kind of book being recognized more. Encore is my last unread journal of May Sarton’s. It begins in May 1991, when she’s 79 and in recovery from major illness. She’s still plagued by pain and fatigue, but her garden and visits from friends are a solace. Although she has to lie down to garden, “to put my hands in the earth to dig is life giving … it is almost as if the earth were nourishing me at the moment.” As usual, there are lovely reflections on the freedoms as well as the losses of ageing. This book, like the previous, was dictated, so there is a bit of repetition. I’ve been amused to see how pretentious she found A.S. Byatt’s Possession! An entry or two at a sitting helped calm my mind during the stress of moving week.

Encore is my last unread journal of May Sarton’s. It begins in May 1991, when she’s 79 and in recovery from major illness. She’s still plagued by pain and fatigue, but her garden and visits from friends are a solace. Although she has to lie down to garden, “to put my hands in the earth to dig is life giving … it is almost as if the earth were nourishing me at the moment.” As usual, there are lovely reflections on the freedoms as well as the losses of ageing. This book, like the previous, was dictated, so there is a bit of repetition. I’ve been amused to see how pretentious she found A.S. Byatt’s Possession! An entry or two at a sitting helped calm my mind during the stress of moving week.

I saw it on shelf at the library and knew now was the perfect time to read My Life in Houses by Margaret Forster, a memoir via the places she’s lived, starting with the house where she was born in 1938, on a council estate in Carlisle. There’s something appealing to me about tracing a life story through homes – Paul Auster did the same in part of Winter Journal. I’d be tempted to undertake a similar exercise myself someday.

I saw it on shelf at the library and knew now was the perfect time to read My Life in Houses by Margaret Forster, a memoir via the places she’s lived, starting with the house where she was born in 1938, on a council estate in Carlisle. There’s something appealing to me about tracing a life story through homes – Paul Auster did the same in part of Winter Journal. I’d be tempted to undertake a similar exercise myself someday. The swifts come screeching down our new street and we saw one investigating a crevice in our back roof for a nest! In Fledgling by Hannah Bourne-Taylor, she is lonely in rural Ghana, where she and her husband had moved for his work, and takes in a young swift displaced from its nest. I’m only in the early pages, but can tell that her care for the bird will be a way of exploring her own feeling of displacement and the desire to belong. “Although I was unaware of it at the time, the English countryside and the birds had turned into my anchor of home.”

The swifts come screeching down our new street and we saw one investigating a crevice in our back roof for a nest! In Fledgling by Hannah Bourne-Taylor, she is lonely in rural Ghana, where she and her husband had moved for his work, and takes in a young swift displaced from its nest. I’m only in the early pages, but can tell that her care for the bird will be a way of exploring her own feeling of displacement and the desire to belong. “Although I was unaware of it at the time, the English countryside and the birds had turned into my anchor of home.”

This was the nonfiction work of Auster’s I was most keen to read, and I thoroughly enjoyed its first part, “Portrait of an Invisible Man,” which includes a depiction of his late father, a discussion of his relationship with his son, and a brief investigation into his grandmother’s murder of his grandfather, which I’d first learned about from

This was the nonfiction work of Auster’s I was most keen to read, and I thoroughly enjoyed its first part, “Portrait of an Invisible Man,” which includes a depiction of his late father, a discussion of his relationship with his son, and a brief investigation into his grandmother’s murder of his grandfather, which I’d first learned about from

I assumed this was a stand-alone from Knausgaard; when it popped up during an author search on Awesomebooks.com and I saw how short it was, I thought why not? As it happens, this Vintage Minis paperback is actually a set of excerpts from A Man in Love, the second volume of his huge autofiction project, My Struggle (I’ve only read the first book,

I assumed this was a stand-alone from Knausgaard; when it popped up during an author search on Awesomebooks.com and I saw how short it was, I thought why not? As it happens, this Vintage Minis paperback is actually a set of excerpts from A Man in Love, the second volume of his huge autofiction project, My Struggle (I’ve only read the first book,

This was expanded from an occasional series of essays Lewis published in Slate in the 2000s, responding to the births of his three children, Quinn, Dixie and Walker, and exploring the modern father’s role, especially “the persistent and disturbing gap between what I was meant to feel and what I actually felt.” It took time for him to feel more than simply mild affection for each child; often the attachment didn’t arrive until after a period of intense care (as when his son Walker was hospitalized with RSV and he stayed with him around the clock). I can’t seem to find the exact line now, but Jennifer Senior (author of

This was expanded from an occasional series of essays Lewis published in Slate in the 2000s, responding to the births of his three children, Quinn, Dixie and Walker, and exploring the modern father’s role, especially “the persistent and disturbing gap between what I was meant to feel and what I actually felt.” It took time for him to feel more than simply mild affection for each child; often the attachment didn’t arrive until after a period of intense care (as when his son Walker was hospitalized with RSV and he stayed with him around the clock). I can’t seem to find the exact line now, but Jennifer Senior (author of

Oldest author read this year: Peggy Seeger was 82 when her memoir First Time Ever was published. I haven’t double-checked the age of every single author, but I think second place at 77 is a tie between debut novelist Arlene Heyman for Artifact and Sue Miller for Monogamy. (I don’t know how old Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren, the joint authors of The Consolation of Nature, are; Mynott may actually be the oldest overall, and their combined age is likely over 200.)

Oldest author read this year: Peggy Seeger was 82 when her memoir First Time Ever was published. I haven’t double-checked the age of every single author, but I think second place at 77 is a tie between debut novelist Arlene Heyman for Artifact and Sue Miller for Monogamy. (I don’t know how old Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren, the joint authors of The Consolation of Nature, are; Mynott may actually be the oldest overall, and their combined age is likely over 200.) Youngest author read this year: You might assume it was 16-year-old Dara McAnulty with Diary of a Young Naturalist, which won the Wainwright Prize (as well as the An Post Irish Book Award for Newcomer of the Year, the Books Are My Bag Reader Award for Non-Fiction, and the Hay Festival Book of the Year!) … or Thunberg, above, who was 16 when her book came out. They were indeed tied for youngest until, earlier in December, I started reading The House without Windows (1927) by Barbara Newhall Follett, a bizarre fantasy novel published when the child prodigy was 12.

Youngest author read this year: You might assume it was 16-year-old Dara McAnulty with Diary of a Young Naturalist, which won the Wainwright Prize (as well as the An Post Irish Book Award for Newcomer of the Year, the Books Are My Bag Reader Award for Non-Fiction, and the Hay Festival Book of the Year!) … or Thunberg, above, who was 16 when her book came out. They were indeed tied for youngest until, earlier in December, I started reading The House without Windows (1927) by Barbara Newhall Follett, a bizarre fantasy novel published when the child prodigy was 12.

The book that made me laugh the most: Kay’s Anatomy by Adam Kay

The book that made me laugh the most: Kay’s Anatomy by Adam Kay The book that put a song in my head every single time I looked at it, much less read it: I Am an Island by Tamsin Calidas (i.e., “I Am a Rock” by Simon and Garfunkel, which, as my husband pointed out, has very appropriate lyrics for 2020: “In a deep and dark December / I am alone / Gazing from my window to the streets below … Hiding in my room / Safe within my womb / I touch no one and no one touches me.”)

The book that put a song in my head every single time I looked at it, much less read it: I Am an Island by Tamsin Calidas (i.e., “I Am a Rock” by Simon and Garfunkel, which, as my husband pointed out, has very appropriate lyrics for 2020: “In a deep and dark December / I am alone / Gazing from my window to the streets below … Hiding in my room / Safe within my womb / I touch no one and no one touches me.”)

Most unexpectedly apt lines encountered in a book: “People came to church wearing masks, if they came at all. They’d sit as far from each other as they could.” (Gilead by Marilynne Robinson. Describing not COVID-19 times but the Spanish flu.)

Most unexpectedly apt lines encountered in a book: “People came to church wearing masks, if they came at all. They’d sit as far from each other as they could.” (Gilead by Marilynne Robinson. Describing not COVID-19 times but the Spanish flu.) Most ironic lines encountered in a book: “September 12—In the ongoing hearings, Senator Joseph Biden pledges to consider the Bork nomination ‘with total objectivity,’ adding, ‘You have that on my honor not only as a senator, but also as the Prince of Wales.’ … October 1—Senator Joseph Biden is forced to withdraw from the Democratic presidential race when it is learned that he is in fact an elderly Norwegian woman.” (from the 1987 roundup in Dave Barry’s Greatest Hits – Biden has been on the U.S. political scene, and mocked, for 3.5+ decades!)

Most ironic lines encountered in a book: “September 12—In the ongoing hearings, Senator Joseph Biden pledges to consider the Bork nomination ‘with total objectivity,’ adding, ‘You have that on my honor not only as a senator, but also as the Prince of Wales.’ … October 1—Senator Joseph Biden is forced to withdraw from the Democratic presidential race when it is learned that he is in fact an elderly Norwegian woman.” (from the 1987 roundup in Dave Barry’s Greatest Hits – Biden has been on the U.S. political scene, and mocked, for 3.5+ decades!) Best first line encountered this year: “And then there was the day when Addie Moore made a call on Louis Waters.” (Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf)

Best first line encountered this year: “And then there was the day when Addie Moore made a call on Louis Waters.” (Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf)

The downright strangest books I read this year: Enter the Aardvark by Jessica Anthony, A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom by John Boyne, The House Without Windows by Barbara Newhall Follett, and The Child in Time by Ian McEwan

The downright strangest books I read this year: Enter the Aardvark by Jessica Anthony, A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom by John Boyne, The House Without Windows by Barbara Newhall Follett, and The Child in Time by Ian McEwan