The Fell by Sarah Moss for #NovNov

Sarah Moss’s latest three releases have all been of novella length. I reviewed Ghost Wall for Novellas in November in 2018, and Summerwater in August 2020. In this trio, she’s demonstrated a fascination with what happens when people of diverging backgrounds and opinions are thrown together in extreme circumstances. Moss almost stops time as her effortless third-person omniscient narration moves from one character’s head to another. We feel that we know each one’s experiences and motivations from the inside. Whereas Ghost Wall was set in two weeks of a late-1980s summer, Summerwater and now the taut The Fell have pushed that time compression even further, spanning a day and about half a day, respectively.

A circadian narrative holds a lot of appeal – we’re all tantalized, I think, by the potential difference that one day can make. The particular day chosen as the backdrop for The Fell offers an ideal combination of the mundane and the climactic because it was during the UK’s November 2020 lockdown. On top of that blanket restriction, single mum Kate has been exposed to Covid-19 via a café colleague, so she and her teenage son Matt are meant to be in strict two-week quarantine. Except Kate can’t bear to be cooped up one minute longer and, as dusk falls, she sneaks out of their home in the Peak District National Park to climb a nearby hill. She knows this fell like the back of her hand, so doesn’t bother taking her phone.

Over the next 12 hours or so, we dart between four stream-of-consciousness internal monologues: besides Kate and Matt, the two main characters are their neighbour, Alice, an older widow who has undergone cancer treatment; and Rob, part of the volunteer hill rescue crew sent out to find Kate when she fails to return quickly. For the most part – as befits the lockdown – each is stuck in their solitary musings (Kate regrets her marriage, Alice reflects on a bristly relationship with her daughter, Rob remembers a friend who died up a mountain), but there are also a few brief interactions between them. I particularly enjoyed time spent with Kate as she sings religious songs and imagines a raven conducting her inquisition.

What Moss wants to do here, is done well. My misgiving is to do with the recycling of an identical approach from Summerwater – not just the circadian limit, present tense, no speech marks and POV-hopping, but also naming each short chapter after a random phrase from it. Another problem is one of timing. Had this come out last November, or even this January, it might have been close enough to events to be essential. Instead, it seems stuck in a time warp. Early on in the first lockdown, when our local arts venue’s open mic nights had gone online, one participant made a semi-professional music video for a song with the refrain “everyone’s got the same jokes.”

That’s how I reacted to The Fell: baking bread and biscuits, a family catch-up on Zoom, repainting and clearouts, even obsessive hand-washing … the references were worn out well before a draft was finished. Ironic though it may seem, I feel like I’ve found more cogent commentary about our present moment from Moss’s historical work. Yet I’ve read all of her fiction and would still list her among my favourite contemporary writers. Aspiring creative writers could approach the Summerwater/The Fell duology as a masterclass in perspective, voice and concise plotting. But I hope for something new from her next book.

[180 pages]

With thanks to Picador for the free copy for review.

Other reviews:

Imitation Is the Sincerest Form of Flattery: Costello, O’Shaughnessy & Smyth

These three books – two novels and a memoir – pay loving tribute to a particular nineteenth- or twentieth-century writer. In each case, the author incorporates passages of pastiche, moving beyond thematic similarity to make their language an additional homage.

Although I enjoyed the three books very much, they differ in terms of how familiar you should be with the source material before embarkation. So while they were all  reads for me, I have added a note below each review to indicate the level of prior knowledge needed.

reads for me, I have added a note below each review to indicate the level of prior knowledge needed.

The River Capture by Mary Costello

Luke O’Brien has taken a long sabbatical from his teaching job in Dublin and is back living at the family farm beside the river in Waterford. Though only in his mid-thirties, he seems like a man of sorrows, often dwelling on the loss of parents, aunts and romantic relationships with both men and women. He takes quiet pleasure in food, the company of pets, and books, including his extensive collection on James Joyce, about whom he’d like to write a tome of his own. The novel’s very gentle crisis comes when Luke falls for Ruth and it emerges that her late father ruined his beloved Aunt Ellen’s reputation.

Luke O’Brien has taken a long sabbatical from his teaching job in Dublin and is back living at the family farm beside the river in Waterford. Though only in his mid-thirties, he seems like a man of sorrows, often dwelling on the loss of parents, aunts and romantic relationships with both men and women. He takes quiet pleasure in food, the company of pets, and books, including his extensive collection on James Joyce, about whom he’d like to write a tome of his own. The novel’s very gentle crisis comes when Luke falls for Ruth and it emerges that her late father ruined his beloved Aunt Ellen’s reputation.

At this point a troubled Luke is driven into 100+ pages of sinuous contemplation, a bravura section of short fragments headed by questions. Rather like a catechism, it’s a playful way of organizing his thoughts and likely more than a little Joycean in approach – I’ve read Portrait of the Artist and Dubliners but not Ulysses or Finnegans Wake, so I feel less than able to comment on the literary ventriloquism, but I found this a pleasingly over-the-top stream-of-consciousness that ranges from the profound (“What fear suddenly assails him? The arrival of the noonday demon”) to the scatological (“At what point does he urinate? At approximately three-quarters of the way up the avenue”).

While this doesn’t quite match Costello’s near-perfect novella, Academy Street, it’s an impressive experiment in voice and style, and the treatment of Luke’s bisexuality struck me as sensitive – an apt metaphorical manifestation of the novel’s focus on fluidity. (See also Susan’s excellent review.)

Why Joyce? “integrity … commitment to the quotidian … refusal to take conventions for granted”

Familiarity required: Moderate

Also recommended: The Sixteenth of June by Maya Lang

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

In Love with George Eliot by Kathy O’Shaughnessy

Many characters, fictional and historical, are in love with George Eliot over the course of this debut novel by a literary editor. The whole thing is a book within a book – fiction being written by Kate, an academic at London’s Queen Elizabeth College who’s preparing for two conferences on Eliot and a new co-taught course on life writing at the same time as she completes her novel, which blends biographical information and imagined scenes.

1857: Eliot is living with George Henry Lewes, her common-law husband, and working on Adam Bede, which becomes a runaway success, not least because of speculation about its anonymous author. 1880: The great author’s death leaves behind a mentally unstable widower 20 years her junior, John Walter Cross, once such a close family friend that she and Lewes called him “Nephew.”

1857: Eliot is living with George Henry Lewes, her common-law husband, and working on Adam Bede, which becomes a runaway success, not least because of speculation about its anonymous author. 1880: The great author’s death leaves behind a mentally unstable widower 20 years her junior, John Walter Cross, once such a close family friend that she and Lewes called him “Nephew.”

Between these points are intriguing vignettes from Eliot’s life with her two great loves, and insight into her scandalous position in Victorian society. Her estrangement from her dear brother (the model for Tom in The Mill on the Floss) is a plangent refrain, while interactions with female friends who have accepted the norms of marriage and motherhood reveal just how transgressive her life is perceived to be.

In the historical sections O’Shaughnessy mimics Victorian prose ably, yet avoids the convoluted syntax that can make Eliot challenging. I might have liked a bit more of the contemporary story line, in which Kate and an alluring colleague make their way to Venice (the site of Eliot’s legendarily disastrous honeymoon trip with Cross), but by making this a minor thread O’Shaughnessy ensures that the spotlight remains on Eliot throughout.

Highlights: A cameo appearance by Henry James; a surprisingly sexy passage in which Cross and Eliot read Dante aloud to each other and share their first kiss.

Why Eliot? “As an artist, this was her task, to move the reader to see people in the round.”

Familiarity required: Low

Also recommended: 142 Strand by Rosemary Ashton, Sophie and the Sibyl by Patricia Duncker, and My Life in Middlemarch by Rebecca Mead

With thanks to Scribe UK for the free copy for review.

All the Lives We Ever Lived: Seeking Solace in Virginia Woolf by Katharine Smyth

Smyth first read To the Lighthouse in Christmas 2001, during her junior year abroad at Oxford. Shortly thereafter her father had surgery in Boston to remove his bladder, one of many operations he’d had during a decade battling cancer. But even this new health scare wasn’t enough to keep him from returning to his habitual three bottles of wine a day. Woolf was there for Smyth during this crisis and all the time leading up to her father’s death, with Lighthouse and Woolf’s own life reflecting Smyth’s experience in unanticipated ways. The Smyths’ Rhode Island beach house, for instance, was reminiscent of the Stephens’ home in Cornwall. Woolf’s mother’s death was an end to the summer visits, and to her childhood; Lighthouse would become her elegy to those bygone days.

Smyth first read To the Lighthouse in Christmas 2001, during her junior year abroad at Oxford. Shortly thereafter her father had surgery in Boston to remove his bladder, one of many operations he’d had during a decade battling cancer. But even this new health scare wasn’t enough to keep him from returning to his habitual three bottles of wine a day. Woolf was there for Smyth during this crisis and all the time leading up to her father’s death, with Lighthouse and Woolf’s own life reflecting Smyth’s experience in unanticipated ways. The Smyths’ Rhode Island beach house, for instance, was reminiscent of the Stephens’ home in Cornwall. Woolf’s mother’s death was an end to the summer visits, and to her childhood; Lighthouse would become her elegy to those bygone days.

Often a short passage by or about Woolf is enough to launch Smyth back into her memories. As an only child, she envied the busy family life of the Ramsays in Lighthouse. She delves into the mystery of her parents’ marriage and her father’s faltering architecture career. She also undertakes Woolf tourism, including the Cornwall cottage, Knole, Charleston and Monk’s House (where Woolf wrote most of Lighthouse). Her writing is dreamy, mingling past and present as she muses on time and grief. The passages of Woolf pastiche are obvious but short enough not to overstay their welcome; as in the Costello, they tend to feature water imagery. It’s a most unusual book in the conception, but for Woolf fans especially, it works. However, I wished I had read Lighthouse more recently than 16.5 years ago – it’s one to reread.

Why Woolf? “I think it’s Woolf’s mastery of moments like these—moments that hold up a mirror to our private tumult while also revealing how much we as humans share—that most draws me to her.”

Undergraduate wisdom: “Woolf’s technique: taking a very complex (usually female) character and using her mind as an emblem of all minds” [copied from notes I took during a lecture on To the Lighthouse in a “Modern Wasteland” course during my sophomore year of college]

Familiarity required: High

Also recommended: Virginia Woolf in Manhattan by Maggie Gee, Vanessa and Her Sister by Priya Parmar, and Adeline by Norah Vincent

With thanks to Atlantic Books for the free copy for review.

Die, My Love by Ariana Harwicz

This intense Argentinian novella, originally published in 2012 and nominated for this year’s Republic of Consciousness and Man Booker International Prizes, is an inside look at postpartum depression as it shades into what looks like full-blown psychosis. We never learn the name of our narrator, just that she’s a foreigner living in France (like Harwicz herself) and has a husband and young son. The stream-of-consciousness chapters are each composed of a single paragraph that stretches over two or more pages. From the first page onwards, we get the sense that this character is on the edge: as she’s hanging laundry outside, she imagines a sun shaft as a knife in her hand. But for now she’s still in control. “I wasn’t going to kill them. I dropped the knife and went to hang out the washing like nothing had happened.”

Not a lot happens over the course of the book; what’s more important is to be immersed in this character’s bitter and perhaps suicidal or sadistic outlook. But there are a handful of concrete events. Her father-in-law has recently died, so she tells of his funeral and what she perceives as his sad little life. Her husband brings home a stray dog that comes to a bad end. Their son attends a children’s party and they take along a box of pastries that melt in the heat.

Not a lot happens over the course of the book; what’s more important is to be immersed in this character’s bitter and perhaps suicidal or sadistic outlook. But there are a handful of concrete events. Her father-in-law has recently died, so she tells of his funeral and what she perceives as his sad little life. Her husband brings home a stray dog that comes to a bad end. Their son attends a children’s party and they take along a box of pastries that melt in the heat.

The only escape from this woman’s mind is a chapter from the point of view of a neighbor, a married radiologist with a disabled daughter who passes her each day on his motorcycle and desires her. With such an unreliable narrator, though, it’s hard to know whether the relationship they strike up is real. This woman is racked by sexual fantasies, but doesn’t seem to be having much sex; when she does, it’s described in disturbing terms: “He opened my legs. He poked around with his calloused hands. Desire is the last thing there is in my cries.”

The language is jolting and in-your-face, but often very imaginative as well. Harwicz has achieved the remarkable feat of showing a mind in the process of cracking up. It’s all very strange and unnerving, and I found that the reading experience required steady concentration. But if you find the passages below intriguing, you’ll want to seek out this top-class translation from new Edinburgh-based publisher Charco Press. It’s the first book in what Harwicz calls “an involuntary trilogy” and has earned her comparisons to Virginia Woolf.

“My mind is somewhere else, like I’ve been startled awake by a nightmare. I want to drive down the road and not stop when I reach the irrigation ditch.”

“I take off my sleep costume, my poisonous skin. I recover my sense of smell and my eyelashes, go back to pronouncing words and swallowing. I look at myself in the mirror and see a different person to yesterday. I’m not a mother.”

“The look I’m going for is Zelda Fitzgerald en route to Switzerland, and not for the chocolate or watches, either.”

My rating:

Translated from the Spanish by Sarah Moses and Carolina Orloff. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

Berger (1926–2017), an art critic and Booker Prize-winning novelist, spent six weeks shadowing the doctor, to whom he gives the pseudonym John Sassall, with Swiss documentary photographer Jean Mohr, his frequent collaborator. Sassall’s dedication was legendary: he attended every birth in this community, and nearly every death. Sassall’s middle-class origins set him apart from his patients. There’s something condescending about how Berger depicts the locals as simple peasants. Mohr’s photos include soft-focus close-ups on faces exhibiting a sequence of emotions, a technique that feels outdated in the age of video. Along with recording the day-to-day details of medical complaints and interventions, Berger waxes philosophical on topics such as infirmity and vocation. A Fortunate Man is a curious book, part intellectual enquiry and part hagiography.

Berger (1926–2017), an art critic and Booker Prize-winning novelist, spent six weeks shadowing the doctor, to whom he gives the pseudonym John Sassall, with Swiss documentary photographer Jean Mohr, his frequent collaborator. Sassall’s dedication was legendary: he attended every birth in this community, and nearly every death. Sassall’s middle-class origins set him apart from his patients. There’s something condescending about how Berger depicts the locals as simple peasants. Mohr’s photos include soft-focus close-ups on faces exhibiting a sequence of emotions, a technique that feels outdated in the age of video. Along with recording the day-to-day details of medical complaints and interventions, Berger waxes philosophical on topics such as infirmity and vocation. A Fortunate Man is a curious book, part intellectual enquiry and part hagiography.  With its layers of local history and its braided biographical strands, A Fortunate Woman takes up many of the same heavy questions but feels more subtle and timely. It also soon delivers a jolting surprise: the doctor Berger called John Sassall was likely bipolar and, soon after the death of his beloved wife Betty, committed suicide in 1982. His story still haunts this community, where many of the older patients remember going to him for treatment. Like Berger, Morland keenly follows a range of cases. As the book progresses, we see this beautiful valley cycle through the seasons, with certain of Richard Baker’s landscape shots deliberately recreating Mohr’s scene setting. The timing of Morland’s book means that it morphs from a portrait of the quotidian for a doctor and a community to, two-thirds through, an incidental record of the challenges of medical practice during COVID-19.

With its layers of local history and its braided biographical strands, A Fortunate Woman takes up many of the same heavy questions but feels more subtle and timely. It also soon delivers a jolting surprise: the doctor Berger called John Sassall was likely bipolar and, soon after the death of his beloved wife Betty, committed suicide in 1982. His story still haunts this community, where many of the older patients remember going to him for treatment. Like Berger, Morland keenly follows a range of cases. As the book progresses, we see this beautiful valley cycle through the seasons, with certain of Richard Baker’s landscape shots deliberately recreating Mohr’s scene setting. The timing of Morland’s book means that it morphs from a portrait of the quotidian for a doctor and a community to, two-thirds through, an incidental record of the challenges of medical practice during COVID-19.

Galbraith’s is an elegiac tour through imperilled countryside and urban edgelands. Each chapter resembles an in-depth magazine article: a carefully crafted profile of a beloved bird species, with a focus on the specific threats it faces. Galbraith recognises the nuances of land use. However, shooting plays an outsized role. (Curious for his bio not to disclose that he is editor of the Shooting Times.) The title’s reference is to literal birdsong, but the book also celebrates birds’ cultural importance through their place in Britain’s folk music and poetry. He is clearly enamoured of countryside ways, but too often slips into laddishness, with no opportunity missed to mention him or another man having a “piss” outside. Readers could also be forgiven for concluding that “Ilka” (no surname, affiliation or job title), who briefs him on her research into kittiwake populations in Orkney, is the only female working in nature conservation in the entire country; with few exceptions, women only have bit parts: the farm wife making the tea, the receptionist on the phone line, and so on.

Galbraith’s is an elegiac tour through imperilled countryside and urban edgelands. Each chapter resembles an in-depth magazine article: a carefully crafted profile of a beloved bird species, with a focus on the specific threats it faces. Galbraith recognises the nuances of land use. However, shooting plays an outsized role. (Curious for his bio not to disclose that he is editor of the Shooting Times.) The title’s reference is to literal birdsong, but the book also celebrates birds’ cultural importance through their place in Britain’s folk music and poetry. He is clearly enamoured of countryside ways, but too often slips into laddishness, with no opportunity missed to mention him or another man having a “piss” outside. Readers could also be forgiven for concluding that “Ilka” (no surname, affiliation or job title), who briefs him on her research into kittiwake populations in Orkney, is the only female working in nature conservation in the entire country; with few exceptions, women only have bit parts: the farm wife making the tea, the receptionist on the phone line, and so on.  Pavelle’s book is a tonic in more ways than one. Employed by Beaver Trust, she is enthusiastic and self-deprecating. Her nature quest has a broader scope, including insects like the marsh fritillary and marine species such as seagrass and the Atlantic salmon. Travelling between lockdowns in 2020–1, Pavelle took low-carbon transport wherever possible and bolsters her trip accounts with context, much of it gleaned from Zoom calls and e-mail correspondence with experts from museums and universities. Refreshingly, around half of these interviewees are women, and the animal subjects are never the obvious choices. Instead, she seeks out “underdog” species. The explanations are at a suitable level for laymen, true to her job as a science communicator. The snappy, casual prose (“the future of the bilberry bumblebee and its Aperol arse can be bright, but only if we get off our own”) could even endear her to teenage readers. As image goes, Pavelle’s cheerful naïveté holds more charm than Galbraith’s hardboiled masculinity.

Pavelle’s book is a tonic in more ways than one. Employed by Beaver Trust, she is enthusiastic and self-deprecating. Her nature quest has a broader scope, including insects like the marsh fritillary and marine species such as seagrass and the Atlantic salmon. Travelling between lockdowns in 2020–1, Pavelle took low-carbon transport wherever possible and bolsters her trip accounts with context, much of it gleaned from Zoom calls and e-mail correspondence with experts from museums and universities. Refreshingly, around half of these interviewees are women, and the animal subjects are never the obvious choices. Instead, she seeks out “underdog” species. The explanations are at a suitable level for laymen, true to her job as a science communicator. The snappy, casual prose (“the future of the bilberry bumblebee and its Aperol arse can be bright, but only if we get off our own”) could even endear her to teenage readers. As image goes, Pavelle’s cheerful naïveté holds more charm than Galbraith’s hardboiled masculinity.  Taking Flight by Lev Parikian: Parikian’s accessible account of the animal kingdom’s development of flight exhibits a layman’s enthusiasm for an everyday wonder. He explicates the range of flying strategies and the structural adaptations that made them possible. The archaeopteryx section, chronicling the transition between dinosaurs and birds, is a highlight. Though the most science-heavy of the author’s six works, this, perhaps ironically, has fewer footnotes. His usual wit is on display: he describes the feral pigeon as “the Volkswagen Golf of birds” and penguins as “piebald blubber tubes”. This makes it a pleasure to tag along on a journey through evolutionary time, one sure to engage even history- and science-phobes.

Taking Flight by Lev Parikian: Parikian’s accessible account of the animal kingdom’s development of flight exhibits a layman’s enthusiasm for an everyday wonder. He explicates the range of flying strategies and the structural adaptations that made them possible. The archaeopteryx section, chronicling the transition between dinosaurs and birds, is a highlight. Though the most science-heavy of the author’s six works, this, perhaps ironically, has fewer footnotes. His usual wit is on display: he describes the feral pigeon as “the Volkswagen Golf of birds” and penguins as “piebald blubber tubes”. This makes it a pleasure to tag along on a journey through evolutionary time, one sure to engage even history- and science-phobes.

Back in the toxic, overcrowded City, Bea was an interior decorator and her partner a professor of anthropology. Bea left to give Agnes a better chance at life; like so many other children, she had become ill from her polluted surroundings. Now she is a bright, precocious leader in the making, fully participating in the community’s daily chores. Settlement tempts them, but the Rangers enforce nomadism. Newcomers soon swell their numbers, and there are rumors of other groups, too. Is it even a wilderness anymore if so many people live in it?

Back in the toxic, overcrowded City, Bea was an interior decorator and her partner a professor of anthropology. Bea left to give Agnes a better chance at life; like so many other children, she had become ill from her polluted surroundings. Now she is a bright, precocious leader in the making, fully participating in the community’s daily chores. Settlement tempts them, but the Rangers enforce nomadism. Newcomers soon swell their numbers, and there are rumors of other groups, too. Is it even a wilderness anymore if so many people live in it?

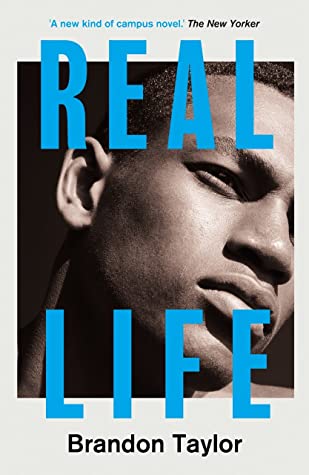

Over the course of one late summer weekend, Wallace questions everything about the life he has built. As a gay African American, he has always been an outsider at the Midwestern university where he’s a graduate student in biochemistry. Though they vary in background and include several homosexuals, some partnered and some unattached, most of his friends are white, and he’s been so busy that he’s largely missed out on evening socializing by the lake – and skipped his father’s funeral (though there are other reasons for that as well).

Over the course of one late summer weekend, Wallace questions everything about the life he has built. As a gay African American, he has always been an outsider at the Midwestern university where he’s a graduate student in biochemistry. Though they vary in background and include several homosexuals, some partnered and some unattached, most of his friends are white, and he’s been so busy that he’s largely missed out on evening socializing by the lake – and skipped his father’s funeral (though there are other reasons for that as well).

Such a fun book! I’d read the first chapter earlier in the year and set it aside, thinking it was too hip for me. I’m glad I decided to try again – it was a great read, so assured and contemporary. Once I got past a slightly contrived first chapter, I found it completely addictive. The laser-precision plotting and characterization reminded me of Jennifer Egan, Jonathan Franzen and Zadie Smith at their peak, but the sassy voice is all Reid’s own. There are no clear villains here; Alix Chamberlain could easily have filled that role, but I felt for her and for Kelley as much as I did for Emira. The fact that I didn’t think anyone was completely wrong shows how much nuance Reid worked in. The question of privilege is as much about money as it is about race, and these are inextricably intertwined.

Such a fun book! I’d read the first chapter earlier in the year and set it aside, thinking it was too hip for me. I’m glad I decided to try again – it was a great read, so assured and contemporary. Once I got past a slightly contrived first chapter, I found it completely addictive. The laser-precision plotting and characterization reminded me of Jennifer Egan, Jonathan Franzen and Zadie Smith at their peak, but the sassy voice is all Reid’s own. There are no clear villains here; Alix Chamberlain could easily have filled that role, but I felt for her and for Kelley as much as I did for Emira. The fact that I didn’t think anyone was completely wrong shows how much nuance Reid worked in. The question of privilege is as much about money as it is about race, and these are inextricably intertwined.  An intriguing set of linked short stories that combine philosophy and science fiction. Rachel and Eliza are preparing to have a baby together when an ant crawls into Rachel’s eye and she falls ill. Eliza wants to believe her partner but, as a scientist, can’t affirm something that doesn’t make sense (“We don’t need to resort to the mystical to describe physical processes,” she says). Other chapters travel to Turkey, Brazil and Texas – and even into space. It takes 60+ pages to figure out, but you can trust all the threads will converge around Rachel and her son, Arthur, who becomes an astronaut. I was particularly taken by a chapter narrated by the ant (yes, really) as it explores Rachel’s brain. Each section is headed by a potted explanation of a thought experiment from philosophy. I wasn’t entirely sure what to make of the alternative future of the two final chapters. Still, I was impressed with the book’s risk-taking and verve. It’s well worth making a rare dip into sci-fi for this one.

An intriguing set of linked short stories that combine philosophy and science fiction. Rachel and Eliza are preparing to have a baby together when an ant crawls into Rachel’s eye and she falls ill. Eliza wants to believe her partner but, as a scientist, can’t affirm something that doesn’t make sense (“We don’t need to resort to the mystical to describe physical processes,” she says). Other chapters travel to Turkey, Brazil and Texas – and even into space. It takes 60+ pages to figure out, but you can trust all the threads will converge around Rachel and her son, Arthur, who becomes an astronaut. I was particularly taken by a chapter narrated by the ant (yes, really) as it explores Rachel’s brain. Each section is headed by a potted explanation of a thought experiment from philosophy. I wasn’t entirely sure what to make of the alternative future of the two final chapters. Still, I was impressed with the book’s risk-taking and verve. It’s well worth making a rare dip into sci-fi for this one.