Victorian-Themed Novels by Annie Elliot and Livi Michael (#ReadIndies)

I’m going back to my roots as a Victorianist (I completed an MA in Victorian Literature at the University of Leeds in 2006) with these two new novels, the one about Charles Dickens’s turbulent marriage and the other about the real-life inspiration for Elizabeth Gaskell’s Ruth. Both redress the balance of Victorian literature by placing women at the centre of the action, and both were comfortably in the 200–300-page range: turns out that’s how I like my Victoriana these days; none of your triple-decker nonsense.

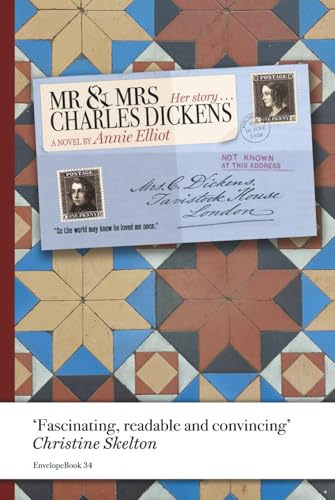

Mr & Mrs Charles Dickens: Her Story by Annie Elliot

I used to proclaim Dickens my favourite author yet haven’t managed to read one of his novels in 15+ years; I seem to be allergic to all that verbiage. He managed to write all those millions of words thanks to his increasing status and wealth, but also thanks to his long-suffering wife, Catherine. Kate sacrificed her health and ambitions to bear and raise his nine children (along with one who died) and – along with sisters and servants – keep a house calm and quiet enough to enable his work.

On her deathbed, Kate begged her daughter to give her love letters from Charles to the British Museum “so the world may know he loved me once.” Annie Elliot has used that phrase as the tagline for her absorbing and vigilantly researched debut novel. The structure perfectly mimics romantic illusions ceding to disenchantment. The framing story is set on 10 June 1870 – the day Kate, the estranged wife, learns of Charles’s death. Sections alternate between the bereaved Kate’s fragile state of mind (depicted in the third person) and first-person flashbacks to their relationship, from first meeting in 1834 to infamous separation in 1858.

On her deathbed, Kate begged her daughter to give her love letters from Charles to the British Museum “so the world may know he loved me once.” Annie Elliot has used that phrase as the tagline for her absorbing and vigilantly researched debut novel. The structure perfectly mimics romantic illusions ceding to disenchantment. The framing story is set on 10 June 1870 – the day Kate, the estranged wife, learns of Charles’s death. Sections alternate between the bereaved Kate’s fragile state of mind (depicted in the third person) and first-person flashbacks to their relationship, from first meeting in 1834 to infamous separation in 1858.

It’s all narrated in the present tense, which creates an eternal now: nothing can be dated when it’s all happening at once for Kate. To start with, the Dickens marriage seems to be based on real love and physical passion. But before long it’s clear that he’s using Kate as ego boost and sexual outlet. She walks on eggshells lest anything shake his confidence. While the death of their baby daughter Dora nearly breaks her, he keeps up a frenzy of writing, travel, property acquisition, and new ventures such as public speaking and the theatre. And, of course, it’s through dramatics that he meets young Nelly Ternan and finds his excuse to push Kate aside.

Though much of this material was familiar to me from Claire Tomalin’s biographies as well as Gaynor Arnold’s novel about Kate, Girl in a Blue Dress, I appreciated the recreation of Kate’s perspective, the glimpses of their children’s lives, and the flashes of humour such as the proliferation of Pickwick memorabilia and a visit from Hans Christian Andersen. This is – yes, still – a necessary corrective to Dickens’s image as the dutiful husband and paterfamilias. And such a beautifully presented book, too. I wish Elliot well for next year’s McKitterick Prize race.

To be published on 1 March. With thanks to the author and EnvelopeBooks for the free copy for review.

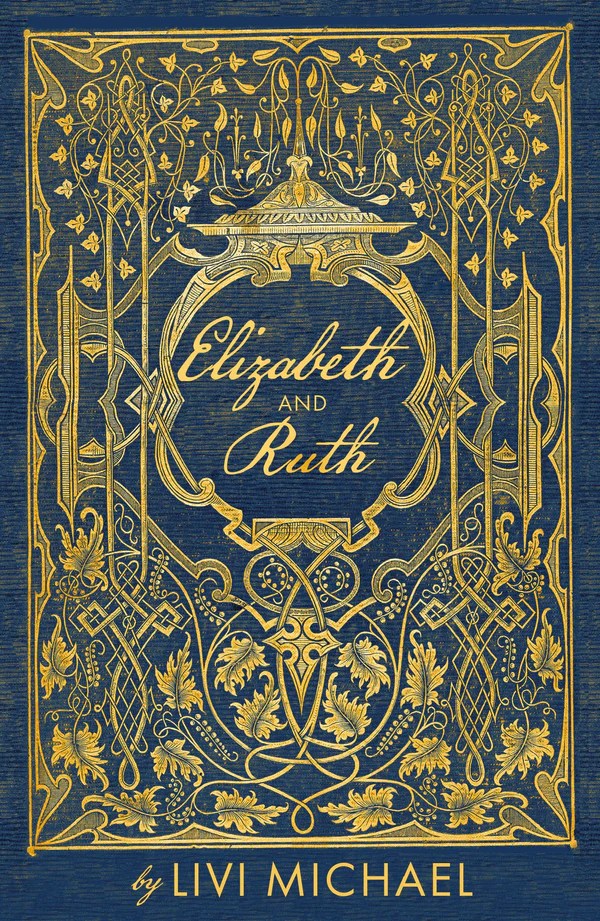

Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael

The Manchester of 1849 is a sordid complex of sweatshops, brothels and workhouses – if you’re Pasley, an Irish teenager abandoned by her mother and shunted from one bad situation to another. Or the Manchester of 1849 is a rarefied colloquium of forward-thinking authors, ministers and politicians – if you’re Elizabeth Gaskell, who’s been revealed as the mind behind the anonymously published sensation Mary Barton.

The two worlds collide when Elizabeth visits Pasley at the New Bailey Prison. She feels for this young woman who’s been a victim of deception, trafficking, and rape and narrowly escaped death by suicide only to end up imprisoned for theft when she made a desperate bid for freedom. There’s only so much that Pasley can bear to tell Mrs Gaskell on these short visits, though; her past would shock a preacher’s wife. Through euphemisms and evasions, Pasley is able to convey that she was taken advantage of by a doctor. Elizabeth suspects that there was a baby, but only readers know the whole truth.

Chapters alternate between Elizabeth’s experience – in an omniscient third person cleverly reminiscent of Victorian prose – and Pasley’s first-person recollections. Elizabeth wants to follow through on her do-gooder reputation and truly help Pasley, who reminds her of her own infant and pregnancy losses. Achieving justice for the girl would be a bonus. All she knows to do is use her pen to change hearts and minds, as she has before (including for Dickens’s magazine) to draw attention to the plight of the poor. Thus, Ruth was born.

This is a riveting and touching novel about the rigidity of convention and the limits of compassion. Livi Michael is a prolific author of whom I’d not heard before Salt sent me this surprise, perfectly suited parcel. Her vivid scenes bring the two-tiered Manchester society to life and reminded me of my visit to the Gaskell House in 2015. My only small complaint would be that the blurb makes it sound as if Gaskell’s correspondence with Dickens will be a central element, when in fact it only appears once, two-thirds of the way through, with one cameo appearance by Dickens right at the end. He’s the better-known author, but after reading this you’ll agree that Gaskell was the subtler, more elegant chronicler.

Published on 9 February. With thanks to Salt Publishing for the proof copy for review.

20 Books of Summer, 11–12 (Victoriana): Edward Carey & George Grossmith

Neither of these appeared on my initial list, but I thought a middle-grade novel and a classic would be good for variety. Though I have an MA in Victorian Literature, I don’t often read from the period anymore because I’m allergic to wordy triple-deckers, so it was a delight to encounter something short and lighthearted. I’ve always been partial to a contemporary Victorian pastiche, though.

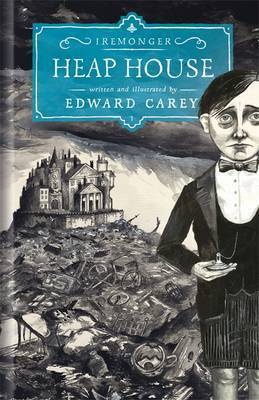

Heap House (Iremonger, #1) by Edward Carey (2013)

The Iremonger family wealth came from salvaging treasure from the rubbish heaps surrounding their London mansion. Every Iremonger has a birth object (like a daemon?) associated with them. Clodius Iremonger, adolescent descendant of the great family, has a special skill: he hears each birth object speaking its name. His own bath plug, for instance, cries out, “James Henry Hayward.” These objects house enchanted souls; people can change back into objects and vice versa. The narration alternates between Clod and plucky Lucy Pennant, who arrives from a local orphanage to work as a house servant. All staff and heap-workers are called “Iremonger,” but Lucy refuses to cede her identity and wants justice for the oppressed workers. She and Clod form a bond against the odds and there’s an upstairs–downstairs tinge to their ensuing adventures in the house and on the heaps.

The Iremonger family wealth came from salvaging treasure from the rubbish heaps surrounding their London mansion. Every Iremonger has a birth object (like a daemon?) associated with them. Clodius Iremonger, adolescent descendant of the great family, has a special skill: he hears each birth object speaking its name. His own bath plug, for instance, cries out, “James Henry Hayward.” These objects house enchanted souls; people can change back into objects and vice versa. The narration alternates between Clod and plucky Lucy Pennant, who arrives from a local orphanage to work as a house servant. All staff and heap-workers are called “Iremonger,” but Lucy refuses to cede her identity and wants justice for the oppressed workers. She and Clod form a bond against the odds and there’s an upstairs–downstairs tinge to their ensuing adventures in the house and on the heaps.

Carey’s trademark twisted combination of Dickensian charm and Gothic gloom is certainly on display here. All the other names are slightly off-kilter: Rosamud, Moorcus, Aliver, Pinalippy and so on. I laughed out loud at a passage about the dubious purpose of doilies. Little truly won me over, but all my experiences with Carey’s work since then (also including The Swallowed Man, B: A Year in Plagues and Pencils, and Edith Holler) have been a slight letdown. This was highly readable and I galloped through the midsection, but I found the whole thing overlong; I’m undecided about reading the other books, though they do have higher average ratings on Goodreads. I got the second, Foulsham, from the Little Free Library and it’s significantly shorter. Shall I continue? (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

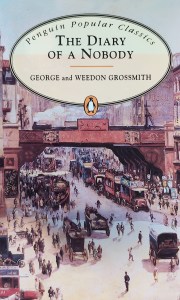

The Diary of a Nobody by George Grossmith; illus. Weedon Grossmith (1892)

It must be rare for a fictional character to be memorialized in the dictionary. I was vaguely aware of the word “Pooterism” but thought it referred to small-minded, pompous, fussy individuals, so my preconception of City clerk Charles Pooter was probably more negative than is warranted. (In fact, “Pooterish” means taking oneself too seriously.) He’s actually a lovable, hapless Everyman who tries desperately to keep up with middle-class society but often gets it wrong. He can’t handle his champagne; and he wants so much to be funny – his are definite dad jokes avant la lettre – but only sometimes pulls it off. He regularly offends tradesmen, servants and neighbours alike, and tries but fails to ingratiate himself with his betters. Luckily, his mistakes are mild and just leave him out of favour – or pocket.

It must be rare for a fictional character to be memorialized in the dictionary. I was vaguely aware of the word “Pooterism” but thought it referred to small-minded, pompous, fussy individuals, so my preconception of City clerk Charles Pooter was probably more negative than is warranted. (In fact, “Pooterish” means taking oneself too seriously.) He’s actually a lovable, hapless Everyman who tries desperately to keep up with middle-class society but often gets it wrong. He can’t handle his champagne; and he wants so much to be funny – his are definite dad jokes avant la lettre – but only sometimes pulls it off. He regularly offends tradesmen, servants and neighbours alike, and tries but fails to ingratiate himself with his betters. Luckily, his mistakes are mild and just leave him out of favour – or pocket.

Originally serialized in Punch, the book is in short entries of one paragraph to a few pages, recounting the Pooters’ first 15 months in their new home. Events range from the mundane – home repairs and decoration – to the great excitement of being invited to the mayor’s ball. Charles and Carrie’s young adult son, Lupin (surely a partial inspiration for Roger Mortimer’s Dear Lupin and its sequels?), who comes back to live with them partway through, is a feckless bounder always being taken in by new money-making schemes and unsuitable ladies. Charles hopes to find Lupin steady employment and steer him away from his infatuation with Daisy Mutlar.

It’s well worth reading for its own sake, but also for the window onto daily Victorian life, including things that aren’t always recorded, such as fashion and slang. And it’s clever how Pooter’s pretensions get punctured by the others around him: longsuffering Carrie (“He tells me his stupid dreams every morning nearly”), insolent Lupin (“Look here, Guv.; excuse me saying so, but you’re a bit out of date”), and testy Gowing – that’s right, the neighbours are named Cummings and Gowing (“I would add, you’re a bigger fool than you look, only that’s absolutely impossible”). All very amusing. (Free from mall bookshop c. 2020) ![]()

Never fear, I’m still on track to finish the challenge by the 31st!

The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley

This was one of my Most Anticipated releases of the year and I’m happy to report that it pretty much lived up to my high hopes. I rightly had in mind that it would be a zany time-travel romance involving a modern-day civil servant falling in love with her charge, who was a real-life Victorian polar explorer. The blurb had me expecting something rather light and one-dimensional, so it was a pleasant surprise to find that this nuanced debut novel alternately goes along with and flouts the tropes of spy fiction and science fiction, and makes clever observations about how we frame stories of empire and progress.

The unnamed first-person narrator is, like Bradley, a young British-Cambodian woman. She is blasé about her government work in languages and relishes the chance to do something a bit different. After a rigorous set of interviews for the Ministry’s mysterious new project, she is hired as a “bridge” helping to resettle one of five “expatriates” from history in near-future London. Her expat is “1847,” 38-year-old Commander Graham Gore, rescued before his death on Sir John Franklin’s ill-fated Arctic expedition.

Two of the other expats, Arthur aka “1916” and seventeenth-century nonconformist Margaret Kemble (both queer), become Gore’s close friends. It’s a delight to watch these characters take up new vocabulary and technology and handpick the things they appreciate about popular culture. There are some hilarious scenes of the gang all together, particularly those involving music: Arthur and Graham put on a ‘disco’, the narrator teaches them all to do the electric slide before a clubbing outing, and they have a go on a theremin.

Gore lives in the narrator’s flat while she oversees his adjustment. At times he is like her “overgrown son,” testing the boundaries and expressing knee-jerk disapproval of things he doesn’t understand. Gradually their bizarre housemate situation turns into an odd-couple romance. “He was an anachronism, a puzzle, a piss-take, a problem, but he was, above all things, a charming man. … I was concussed with love for him. I bent my head to the cudgel.”

Although this feels like wish-fulfilment (imagine choosing a historical figure you find vaguely hot, bringing them back to life, and then giving your fictional stand-in a chance with them), Bradley doesn’t completely gloss over the difficulties their backgrounds and mores would cause. Most noteworthy is his exoticization of her as a mixed-race woman. Occasional passages in archaic font introducing vignettes from Gore’s time in the Arctic suggest that his reaction to the narrator may be informed by a pivotal encounter he had with a bereaved Inuit woman. The expats undergo intense sensitivity training, but the imperial mindset is hard to root out, and even the narrator, whose mother was a refugee from the Khmer Rouge, isn’t sure she’s always getting it right when it comes to racism and assimilation.

Bradley’s descriptive prose is a highlight (“he looked oddly formal, as if he was the sole person in serif font”; “A great graphite pencil inscribed the diagonal journey of water on the air”), memorable but never too quirky just for the sake of it. At a certain point, plot starts to take over and pushes aside the quiet playfulness of the culture shock scenes. I did miss the innocent joy, but that’s Bradley’s point: mess around with the past and grave consequences are bound to follow. We learn that the Ministry has a double agent, that there are visitors from later centuries as well as previous ones, and that the narrator’s own future is at stake.

Maybe because I don’t read hard SF, it didn’t bother me that the explanations and world-building are a little bit thin here. You just have to suspend disbelief at the start and then go with it. The result is a witty, sexy, off-kilter gem. I haven’t had so much sheer fun with a book since Curtis Sittenfeld’s Romantic Comedy, and I will be looking out for whatever Bradley writes next. ![]()

With thanks to Sceptre for the free copy for review.

Buy a copy from Bookshop.org UK! [affiliate link]

May was a big month for new releases and I have lots more review books on the go or waiting in the wings to be reviewed in catch-up posts!

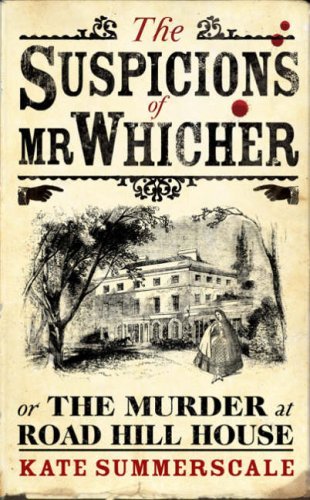

The Suspicions of Mr Whicher Stage Production

Just a few months after Notes from a Small Island, it was back to one of my local theatres, The Watermill, for the stage adaptation of another book club selection, this time the Victorian true crime narrative The Suspicions of Mr Whicher by Kate Summerscale, which won the Samuel Johnson Prize (now called the Baillie Gifford Prize) for non-fiction in 2008.

{SPOILERS ENSUE}

I must have read the book in 2009, the year after it first came out, and while I had the best intentions of rereading it in time for our book club meeting earlier this month, I didn’t even manage to skim it. I remembered one fact alone, the method of murder, which is not surprising as it was particularly gruesome: A young boy had his throat slit and was stuffed down the privy. But that was all that had remained with me. My husband filled me in on the basics and the discussion, held at our house, reminded me of the rest. We then made it a book club outing to the theatre.

The crime took place in late June 1860 at the Wiltshire home of the Kent family: the patriarch, a factory inspector; his four children from his first marriage; his second wife, formerly the older set’s governess; and their three young children. Jonathan “Jack” Whicher, sent by Scotland Yard to investigate, was one of London’s first modern detectives and inspired Wilkie Collins and Charles Dickens. Constance Kent, 16, later confessed to the murder of her three-year-old half-brother, Saville, motivated by anger at her stepmother for replacing her mentally ill mother, but uncertainty remained as to whether she had acted alone.

The play was very well done, maintaining tension even though there was a decision to introduce Constance as the killer immediately: the action opens on her and Mr Whicher in her cell at Fulham Prison in the 1880s. This is an invented scene in which he has come to visit, begging her to tell him the whole truth in exchange for him writing a letter to try to secure her early release. (She appealed four times but ended up serving a full 20-year sentence.)

Cold, stark lighting and a minimal set of two benches against a backdrop of steel doors and a mullioned window evoke the prison setting, with only the subtle change to warmer lighting indicating flashbacks as Constance and Whicher remember or act out events from 20 or more years before. These two remain on stage for the entirety of the first act. Four other actors cycle in and out, playing Kent family members and various other small roles. For instance, the bearded middle-aged actor who plays Mr Kent also appears as a coroner giving a precis of Saville’s autopsy – he mentions Collins and Dickens, but the evolution of the Victorian detective is, by necessity, a much smaller element of the play than it was in the book.

It’s a tiny theatre, but projections on a screen (such as a sinuous family tree) and a balcony, used for wordless presence or loud pronouncements, made it seem bigger than it was. Saville himself is only depicted as a mute figure on that upper level, in the truly spooky scene that closes the first act. I remember when the Watermill put out a discreet call for child actors, warning parents about the sort of content to expect. Three children play the role (plus one other bit part) in rotation. Pulsing violin music enhanced the feeling of dread, and each act was no more than 45 minutes, so the atmosphere remained taut.

Production photographs by Pamela Raith.

A missing nightdress – presumably blood-stained – as well as her own father’s hunch, were among the main evidence against Constance, so Whicher did not secure a conviction at the time and was publicly ridiculed for his failure to crack the case. That and his own loss of a child are suggested to be behind his obsession with tying up loose ends. While Constance expresses regret for her actions and calmly takes him through the accepted timeline of the murder, she refuses to give him anything extra.

The second act delves into what happened next for Constance: living among nuns in France and then in Brighton, where she decided to confess, and then relocating to Australia, where she worked in a halfway house for lepers and troubled youth, as if to make up for the harm she caused earlier in her life (and she lived to age 100!). This involved the most significant change of set and actors, with the former Mr. and Mrs. Kent now filling in as the older Constance and William, the brother closest to her in age.

The play fixates on the siblings’ relationship, returning several times to their whim to run away to Bristol and be “cabin boys” together. I wondered if there was even meant to be a sexual undercurrent to their connection. William Savill-Kent went on to be a successful marine biologist specialising in corals and Australian fisheries. One theory is that they were accomplices in the murder but Constance took the fall so that her brother could live a full life.

Intriguingly, the team behind the production decided to espouse this hypothesis explicitly. In the chilling final scene, then, a crib is wheeled out to the centre of the stage and Constance floats on in a white nightdress to lower the side closest to the audience. Just before the lights go down, William, too, appears in a white nightdress and stands over the far side of the crib.

Although I referred to the book as “compulsive” in the one mention I find of it in my computer files, from 2011, I only gave it 3 stars – my most common rating in those years, an indication that a book was alright but I moved right along to the next in the stack and it didn’t stick with me. My book club had mixed feelings, too, generally feeling that there was too much extraneous detail, which perhaps kept a narrative that could have read as fluidly as a novel from being truly gripping. The play, though, was thrilling.

Book (c. 2009):

Play:

Buy The Suspicions of Mr. Whicher from Bookshop.org [affiliate link]

Birthday Outing and Book Haul

I’m not quite sure why, but I’ve made it a habit of posting something about each birthday I’ve celebrated since I started blogging. Maybe because, otherwise, the years pass so quickly that I can’t remember from one to another what I did, ate, or received as presents! So, to follow on from my 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2021 posts, here’s this year’s rundown. (Oh dear, I realize I’ve read just one of the books I received last year!)

On Thursday, I treated myself to a charity shop crawl around Newbury (it’s a great place for thrift shopping, as is nearby Thatcham) and got two jumpers plus this small stack of secondhand books.

Then yesterday, my actual birthday, we took time off and went to Kelmscott Manor in West Oxfordshire/the Cotswolds (right on the border with Gloucestershire), where Victorian designer William Morris lived. We’re a fan of Morris’s floral-based wallpaper and textile designs and he was a progressive thinker, too, embracing socialism and environmentalism – I’ll get his utopian novel, News from Nowhere, out from the university library to read soon. Despite a drizzly start to the day, the place was packed with visitors. The tea shop’s cakes incorporate fruit from the manor’s own trees. Naturally, I had to sample two of their offerings, and still had room for a chocolate beetroot cupcake (with the requisite candle) once we got home.

On the way back, we stopped in Wantage for some secondhand book shopping. I’d found out about Regent market from Simon’s blog and he’s right – it’s huge, with an excellent stock and good prices (£2 or £2.50 for nearly everything I looked at, vs. when we were in Inverness I didn’t buy a thing at Leakey’s because even poor-condition paperbacks started at £4). I would happily have spent much longer there and acquired twice as much, but one must be restrained when there are further book hauls to come. I was pleased to find several books I’ve been interested in reading for a while, as well as a couple by authors I’ve enjoyed before.

I requested a vegan Chinese feast, inspired by a recent cookbook I’ve reviewed for Shelf Awareness’s upcoming gift books feature, The Vegan Chinese Kitchen by Hannah Che. My husband made a special trip to an Asian grocery superstore in Reading and the recipes were fairly involved, but the results – cabbage rolls, wontons and bao buns, most featuring tofu and mushrooms – were worth waiting for. We have leftovers for the weekend, along with a banoffee cheesecake from Nigella Lawson’s Kitchen still to come. (When are complicated dishes for if not for birthdays?)

I requested a vegan Chinese feast, inspired by a recent cookbook I’ve reviewed for Shelf Awareness’s upcoming gift books feature, The Vegan Chinese Kitchen by Hannah Che. My husband made a special trip to an Asian grocery superstore in Reading and the recipes were fairly involved, but the results – cabbage rolls, wontons and bao buns, most featuring tofu and mushrooms – were worth waiting for. We have leftovers for the weekend, along with a banoffee cheesecake from Nigella Lawson’s Kitchen still to come. (When are complicated dishes for if not for birthdays?)

Here are the books I received as birthday gifts, with more to come, I expect, plus a significant amount of birthday money that I may well spend on books. Some good options for #NovNov22 in here!

Winter Reads, Part II: Au, Glück, Hall, Rautiainen, Slaght

In the week before Christmas I reviewed a first batch of wintry reads. We’ve had hardly any snowfall here in southern England this season, so I gave up on it in real life and sought winter weather on the page. After we’ve seen the back of Storm Franklin (it’s already moved on from Eunice!), I hope it will feel appropriate to start right in on some spring reading. But for today I have a Tokyo-set novella, sombre poems, an OTT contemporary Gothic novel, historical fiction in translation from the Finnish, and – the cream of the crop – a real-life environmentalist adventure in Russia.

Cold Enough for Snow by Jessica Au (2022)

This slim work will be released in the UK by Fitzcarraldo Editions on the 23rd and came out elsewhere this month from New Directions and Giramondo. I actually read it in December during my travel back from the States. It’s a delicate work of autofiction – it reads most like a Chloe Aridjis or Rachel Cusk novel – about a woman and her Hong Kong-raised mother on a trip to Tokyo. You get a bit of a flavour of Japan through their tourism (a museum, a temple, handicrafts, trains, meals), but the real focus is internal as Au subtly probes the workings of memory and generational bonds.

This slim work will be released in the UK by Fitzcarraldo Editions on the 23rd and came out elsewhere this month from New Directions and Giramondo. I actually read it in December during my travel back from the States. It’s a delicate work of autofiction – it reads most like a Chloe Aridjis or Rachel Cusk novel – about a woman and her Hong Kong-raised mother on a trip to Tokyo. You get a bit of a flavour of Japan through their tourism (a museum, a temple, handicrafts, trains, meals), but the real focus is internal as Au subtly probes the workings of memory and generational bonds.

The woman and her mother engage in surprisingly deep conversations about the soul and the meaning of life, but these are conveyed indirectly rather than through dialogue: “she said that she believed that we were all essentially nothing, just series of sensations and desires, none of it lasting. … The best we could do in this life was to pass through it, like smoke through the branches”. Though I highlighted a fair few passages, I find that no details have stuck with me. This is just the sort of spare book I can admire but not warm to. (NetGalley)

Winter Recipes from the Collective by Louise Glück (2021)

The only other poetry collection of Glück’s that I’d read was Vita Nova. This, her first release since her Nobel Prize win, was my final read of 2021 and my shortest, at 40-some pages; it’s composed of just 15 poems, a few of which stretch to five pages or more. “The Denial of Death,” a prose piece with more of the feel of an autobiographical travel essay, was a standout; the title poem, again in prose paragraphs, and the following one, “Winter Journey,” about farewells, bear a melancholy chill. Memories and dreams take pride of place, with the poet’s sister appearing frequently. “How heavy my mind is, filled with the past.” There are also multiple references to Chinese concepts and characters (as on the cover). The overall style is more aphoristic and reflective than expected. Few individual lines or images stood out to me.

The only other poetry collection of Glück’s that I’d read was Vita Nova. This, her first release since her Nobel Prize win, was my final read of 2021 and my shortest, at 40-some pages; it’s composed of just 15 poems, a few of which stretch to five pages or more. “The Denial of Death,” a prose piece with more of the feel of an autobiographical travel essay, was a standout; the title poem, again in prose paragraphs, and the following one, “Winter Journey,” about farewells, bear a melancholy chill. Memories and dreams take pride of place, with the poet’s sister appearing frequently. “How heavy my mind is, filled with the past.” There are also multiple references to Chinese concepts and characters (as on the cover). The overall style is more aphoristic and reflective than expected. Few individual lines or images stood out to me.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the e-copy for review.

The Snow Collectors by Tina May Hall (2020)

Henna is alone in the world since her parents and twin sister disappeared in a boating accident. She lives a solitary existence with her sister’s basset hound Rembrandt in a New England village, writing encyclopaedia entries on the Arctic, until she stumbles on a corpse and embarks on an amateur investigation involving scraps of 19th-century correspondence. The dead woman asked inconvenient questions about a historical cover-up; if she takes up the thread, Henna could be a target, too. Her collaboration with the police chief, Fletcher, turns into a flirtation. After her house burns down, she ends up living with him – and his mother and housekeeper – in a Gothic mansion stuffed with birds of prey and historical snow samples. She’s at the mercy of this quirky family and the weather, wearing ancient clothing from Fletcher’s great-aunts and tramping through blizzards looking for answers.

Henna is alone in the world since her parents and twin sister disappeared in a boating accident. She lives a solitary existence with her sister’s basset hound Rembrandt in a New England village, writing encyclopaedia entries on the Arctic, until she stumbles on a corpse and embarks on an amateur investigation involving scraps of 19th-century correspondence. The dead woman asked inconvenient questions about a historical cover-up; if she takes up the thread, Henna could be a target, too. Her collaboration with the police chief, Fletcher, turns into a flirtation. After her house burns down, she ends up living with him – and his mother and housekeeper – in a Gothic mansion stuffed with birds of prey and historical snow samples. She’s at the mercy of this quirky family and the weather, wearing ancient clothing from Fletcher’s great-aunts and tramping through blizzards looking for answers.

This is a kitchen-sink novel with loads going on, as if Hall couldn’t decide which of her interests to include so threw them all in. Yet at only 221 pages, it might actually have been expanded a little to flesh out the backstory and mystery plot. It gets more than a bit ridiculous in places, but its Victorian fan fiction vibe is charming escapism nonetheless. What with the historical fiction interludes about the Franklin expedition, this reminded me most of The Still Point, but also of The World Before Us and The Birth House. I’d happily read Hall’s 2010 short story collection, too. (Christmas gift)

Land of Snow and Ashes by Petra Rautiainen (2022)

[Translated from the Finnish by David Hackston]

In the middle years of World War II, Finland was allied with Nazi Germany against Russia, a mutual enemy. After the Moscow Armistice, the Germans retreated in disgrace, burning as many buildings and planting as many landmines as they could (“the Lapland War”). I gleaned this helpful background information from Hackston’s preface. The story that follows is in two strands: one is set in 1944 and told via diary entries from Väinö Remes, a Finnish soldier called up to interpret at a Nazi prison camp in Inari. The other, in third person, takes place between 1947 and 1950, the early years of postwar reconstruction. Inkeri, a journalist, has come to Enontekiö to find out what happened to her husband. An amateur photographer, she teaches art to the local Sámi children and takes on one girl, Bigga-Marja, as her protégée.

In the middle years of World War II, Finland was allied with Nazi Germany against Russia, a mutual enemy. After the Moscow Armistice, the Germans retreated in disgrace, burning as many buildings and planting as many landmines as they could (“the Lapland War”). I gleaned this helpful background information from Hackston’s preface. The story that follows is in two strands: one is set in 1944 and told via diary entries from Väinö Remes, a Finnish soldier called up to interpret at a Nazi prison camp in Inari. The other, in third person, takes place between 1947 and 1950, the early years of postwar reconstruction. Inkeri, a journalist, has come to Enontekiö to find out what happened to her husband. An amateur photographer, she teaches art to the local Sámi children and takes on one girl, Bigga-Marja, as her protégée.

Collusion and secrets; escaped prisoners and physical measurements being taken of the Sámi: there are a number of sinister hints that become clearer as the novel goes on. I felt a distance from the main characters that I could never quite overcome, such that the reveals didn’t land with as much power as I think was intended. Still, this has the kind of forthright storytelling and precise writing that fans of Hubert Mingarelli should appreciate. For another story of the complexities of being on the wrong side of history, see The Women in the Castle by Jessica Shattuck.

With thanks to Pushkin Press for the proof copy for review.

Winter words:

“Fresh snow has fallen, forming drifts across the terrain. White. Grey. Undulating. The ice has cracked here and there, raising its head in the thawed sections of the river. There is only a thin layer of ice left.”

Owls of the Eastern Ice: The Quest to Find and Save the World’s Largest Owl by Jonathan C. Slaght (2020)

Slaght has become an expert on the Blakiston’s fish owl during nearly two decades of fieldwork in the far east of Russia – much closer to Korea and Japan than to Moscow, the region is also home to Amur tigers. For his Master’s and PhD research at the University of Minnesota, he plotted the territories of breeding pairs of owls and fit them with identifying bands and data loggers to track their movements over the years. He describes these winter field seasons as recurring frontier adventures. Now, I’ve accompanied my husband on fieldwork from time to time, and I can tell you it would be hard to make it sound exciting. Then again, gathering beetles from English fields is pretty staid compared to piloting snowmobiles over melting ice, running from fire, speeding to avoid blockaded logging roads, and being served cleaning-grade ethanol when the vodka runs out.

The sorts of towns Slaght works near are primitive places where adequate food and fuel is a matter of life and death. He and his assistants rely on the hospitality of Anatoliy the crazy hermit and also stay in huts and caravans. Tracking the owls is a rollercoaster experience, with expensive equipment failures and trial and error to narrow down the most effective trapping methods. His team develops a new low-tech technique involving a tray of live fish planted in the river shallows under a net. They come to know individuals and mourn their loss: the Sha-Mi female he’s holding in his author photo was hit by a car four years later.

The sorts of towns Slaght works near are primitive places where adequate food and fuel is a matter of life and death. He and his assistants rely on the hospitality of Anatoliy the crazy hermit and also stay in huts and caravans. Tracking the owls is a rollercoaster experience, with expensive equipment failures and trial and error to narrow down the most effective trapping methods. His team develops a new low-tech technique involving a tray of live fish planted in the river shallows under a net. They come to know individuals and mourn their loss: the Sha-Mi female he’s holding in his author photo was hit by a car four years later.

Slaght thinks of Russia as his second home, and you can sense his passion for the fish owl and for conservation in general. He boils down complicated data and statistics into the simple requirements for this endangered species (fewer than 2000 in the wild): valleys containing old-growth forest with large trees and rivers that don’t fully freeze over. There are only limited areas with these characteristics. These specifications and his ongoing research – Slaght is now the Northeast Asia Coordinator for the Wildlife Conservation Society – inform the policy recommendations given to logging companies and other bodies.

Amid the science, this is just a darn good story, full of bizarre characters like Katkov, a garrulous assistant exiled for his snoring. (“He fueled his monologue with sausage and cheese, then belched zeppelins of aroma into that confined space.”) Slaght himself doesn’t play much of a role in the book, so don’t expect a soul-searching memoir. Instead, you get top-notch nature and travel writing, and a ride along on a consequential environmentalist quest. This is the kind of science book that, like Lab Girl and Entangled Life, I’d recommend even if you don’t normally pick up nonfiction. (Christmas gift)

And a bonus children’s book:

If Winter Comes, Tell It I’m Not Here by Simona Ciraolo (2020)

The little boy loves nothing more than to spend hours at the swimming pool and then have an ice cream cone. His big sister warns him the carefree days of summer will be over soon; it will turn cold and dark and he’ll be cooped up inside. Her words come to pass, yet the boy realizes that every season has its joys and he has to take advantage of them while they last. Cute and colourful, though the drawing style wasn’t my favourite. And a correction is in order: as President Biden would surely tell you, ice cream is a year-round treat! (Public library)

The little boy loves nothing more than to spend hours at the swimming pool and then have an ice cream cone. His big sister warns him the carefree days of summer will be over soon; it will turn cold and dark and he’ll be cooped up inside. Her words come to pass, yet the boy realizes that every season has its joys and he has to take advantage of them while they last. Cute and colourful, though the drawing style wasn’t my favourite. And a correction is in order: as President Biden would surely tell you, ice cream is a year-round treat! (Public library)

Any snowy or icy reading (or weather) for you lately?

#NonFicNov Review Book Catch-Up: Cohen, Gilbert, Hodge, Piesse, Royle

I have a big backlog of review books piled beside my composition station (a corner of the lounge by the front window; an ancient PC inherited from my mother-in-law and not connected to the Internet; a wooden chair with leather seat that had been left behind in a previous rental house’s garage). Nonfiction November is the excuse I need to finally get around to writing about lots of them; at least one more catch-up will be coming later this month. My apologies to the publishers for the brief reviews.

Today I have a therapist’s take on classic literature, an optimist’s research on data use, a journalist’s response to her sister’s and father’s deaths, a professor’s search for the remnants of Charles Darwin at his family home, and a bibliophile’s tales of book-collecting exploits.

How to Live. What to Do.: In Search of Ourselves in Life and Literature by Josh Cohen

“Literature and psychoanalysis are both efforts to make sense of the world through stories, to discover the recurring problems and patterns and themes of life. Read and listen enough, and we soon come to notice how insistently the same struggles, anxieties and hopes repeat themselves down the ages and across the world.”

This is the premise for Cohen’s work life, and for this book. Moving through the human experience from youth to old age, he examines anonymous case studies and works of literature that speak to the sorts of situations encountered in that stage. For instance, he recommends Alice in Wonderland as a tonic for the feeling of being stuck – Lewis Carroll’s “let’s pretend” attitude can help someone return to the playfulness and openness of childhood. William Maxwell’s They Came Like Swallows, set during the Spanish flu, takes on new significance for Cohen in the days of Covid as his appointments all move online; he also takes from it the importance of a mother for providing emotional security. A bibliotherapy theme would normally be catnip for me, but I often found the examples too obvious and the discussion too detailed (and thus involving spoilers). Not a patch on The Novel Cure.

This is the premise for Cohen’s work life, and for this book. Moving through the human experience from youth to old age, he examines anonymous case studies and works of literature that speak to the sorts of situations encountered in that stage. For instance, he recommends Alice in Wonderland as a tonic for the feeling of being stuck – Lewis Carroll’s “let’s pretend” attitude can help someone return to the playfulness and openness of childhood. William Maxwell’s They Came Like Swallows, set during the Spanish flu, takes on new significance for Cohen in the days of Covid as his appointments all move online; he also takes from it the importance of a mother for providing emotional security. A bibliotherapy theme would normally be catnip for me, but I often found the examples too obvious and the discussion too detailed (and thus involving spoilers). Not a patch on The Novel Cure.

(Ebury Press, February 2021.) With thanks to the publicist for the free copy for review.

Good Data: An Optimist’s Guide to Our Digital Future by Sam Gilbert

Gilbert worked for Experian before going back to university to study politics; he is now a researcher at the Bennett Institute for Public Policy at the University of Cambridge. At a time of much anxiety about “surveillance capitalism,” he seeks to provide reassurance. He explains that Facebook and the like, with their ad-based business models, use profile data and behavioural data to make inferences about you. This is not the same as “listening in,” he is careful to assert. Gilbert contrasts broad targeting and micro-targeting, and runs through trends in search data. He highlights instances where social media and data mining have been beneficial, such as in creating jobs, increasing knowledge, or aiding communication during democratic protests. I have to confess that a lot of this went over my head; I’d overestimated my interest in a full book on technology, having reviewed Born Digital earlier in the year.

Gilbert worked for Experian before going back to university to study politics; he is now a researcher at the Bennett Institute for Public Policy at the University of Cambridge. At a time of much anxiety about “surveillance capitalism,” he seeks to provide reassurance. He explains that Facebook and the like, with their ad-based business models, use profile data and behavioural data to make inferences about you. This is not the same as “listening in,” he is careful to assert. Gilbert contrasts broad targeting and micro-targeting, and runs through trends in search data. He highlights instances where social media and data mining have been beneficial, such as in creating jobs, increasing knowledge, or aiding communication during democratic protests. I have to confess that a lot of this went over my head; I’d overestimated my interest in a full book on technology, having reviewed Born Digital earlier in the year.

(Welbeck, April 2021.) With thanks to the publisher for the proof copy for review.

The Consequences of Love by Gavanndra Hodge (2020)

In 1989, Hodge’s younger sister Candy died on a family holiday in Tunisia when a rare virus brought on rapid organ failure. The rest of the family exhibited three very different responses to grief: her father retreated into existing addictions, her mother found religion, and she went numb and forgot her sister as much as possible – despite having a photographic memory in general. After her father’s death, Hodge finally found the courage to look back to her early life and the effect of Candy’s death. Hers was no ordinary upbringing; her father was a drug dealer who constantly disappointed her and from her teens on roped her into his substance abuse evenings. Often she was the closest thing to a sober and rational adult in the drug den their home had become. This is a very fluidly written bereavement memoir and a powerful exploration of memory and trauma. It was unfortunate that it felt that little bit too similar to a couple of other books I’ve read in recent years: When I Had a Little Sister by Catherine Simpson and especially Featherhood by Charlie Gilmour.

In 1989, Hodge’s younger sister Candy died on a family holiday in Tunisia when a rare virus brought on rapid organ failure. The rest of the family exhibited three very different responses to grief: her father retreated into existing addictions, her mother found religion, and she went numb and forgot her sister as much as possible – despite having a photographic memory in general. After her father’s death, Hodge finally found the courage to look back to her early life and the effect of Candy’s death. Hers was no ordinary upbringing; her father was a drug dealer who constantly disappointed her and from her teens on roped her into his substance abuse evenings. Often she was the closest thing to a sober and rational adult in the drug den their home had become. This is a very fluidly written bereavement memoir and a powerful exploration of memory and trauma. It was unfortunate that it felt that little bit too similar to a couple of other books I’ve read in recent years: When I Had a Little Sister by Catherine Simpson and especially Featherhood by Charlie Gilmour.

(Paperback: Penguin, July 2021.) With thanks to the publicist for the free copy for review.

The Ghost in the Garden: In Search of Darwin’s Lost Garden by Jude Piesse

When Piesse’s academic career took her back to her home county of Shropshire, she became fascinated by the Darwin family home in Shrewsbury, The Mount. A Victorian specialist, she threw herself into research on the family and particularly on the traces of the garden. Her thesis is that here, and on long walks through the surrounding countryside, Darwin developed the field methods and careful attention that would serve him well as the naturalist on board the Beagle. Piesse believes the habit of looking closely was shared by Darwin and his mother, Susannah. The author contrasts Susannah’s experience of childrearing with her own – she has two young daughters when she returns to Shropshire, and has to work out a balance between work and motherhood. I noted that Darwin lost his mother early – early parent loss is considered a predictor of high achievement (it links one-third of U.S. presidents, for instance).

When Piesse’s academic career took her back to her home county of Shropshire, she became fascinated by the Darwin family home in Shrewsbury, The Mount. A Victorian specialist, she threw herself into research on the family and particularly on the traces of the garden. Her thesis is that here, and on long walks through the surrounding countryside, Darwin developed the field methods and careful attention that would serve him well as the naturalist on board the Beagle. Piesse believes the habit of looking closely was shared by Darwin and his mother, Susannah. The author contrasts Susannah’s experience of childrearing with her own – she has two young daughters when she returns to Shropshire, and has to work out a balance between work and motherhood. I noted that Darwin lost his mother early – early parent loss is considered a predictor of high achievement (it links one-third of U.S. presidents, for instance).

I think what Piesse was attempting here was something like Rebecca Mead’s wonderful My Life in Middlemarch, but the links just aren’t strong enough: There aren’t that many remnants of the garden or the Darwins here (all the family artefacts are at Down House in Kent), and Piesse doesn’t even step foot into The Mount itself until page 217. I enjoyed her writing about her domestic life and her desire to create a green space, however small, for her daughters, but this doesn’t connect to the Darwin material. Despite my fondness for Victoriana, I was left asking myself what the point of this project was.

(Scribe, May 2021.) With thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

White Spines: Confessions of a Book Collector by Nicholas Royle

From the 1970s to 1990s, Picador released over 1,000 paperback volumes with the same clean white-spined design. Royle has acquired most of them – no matter the author, genre or topic; no worries if he has duplicate copies. To build this impressive collection, he has spent years haunting charity shops and secondhand bookshops in between his teaching and writing commitments. He knows where you can get a good bargain, but he’s also willing to pay a little more for a rarer find. In this meandering memoir-of-sorts, he ponders the art of cover design, delights in ephemera and inscriptions found in his purchases (he groups these together as “inclusions”), investigates some previous owners and the provenance of his signed copies, interviews Picador staff and authors, and muses on the few most ubiquitous titles to be found in charity shops (Once in a House on Fire by Andrea Ashworth, Bridget Jones’s Diary by Helen Fielding, anything by Kathy Lette, and Last Orders by Graham Swift). And he does actually read some of what he buys, though of course not all, and finds some hidden gems.

From the 1970s to 1990s, Picador released over 1,000 paperback volumes with the same clean white-spined design. Royle has acquired most of them – no matter the author, genre or topic; no worries if he has duplicate copies. To build this impressive collection, he has spent years haunting charity shops and secondhand bookshops in between his teaching and writing commitments. He knows where you can get a good bargain, but he’s also willing to pay a little more for a rarer find. In this meandering memoir-of-sorts, he ponders the art of cover design, delights in ephemera and inscriptions found in his purchases (he groups these together as “inclusions”), investigates some previous owners and the provenance of his signed copies, interviews Picador staff and authors, and muses on the few most ubiquitous titles to be found in charity shops (Once in a House on Fire by Andrea Ashworth, Bridget Jones’s Diary by Helen Fielding, anything by Kathy Lette, and Last Orders by Graham Swift). And he does actually read some of what he buys, though of course not all, and finds some hidden gems.

In 2013 I read Royle’s First Novel, which also features Picador spines on its cover and a protagonist obsessed with them. I’d read enthusiastic reviews by fellow bibliophiles – Paul, Simon, Susan – so couldn’t resist requesting White Spines. While I enjoyed the conversational writing, ultimately I thought it quite an indulgent undertaking (especially the records of his dreams!), not dissimilar to a series of book haul posts. The details of shopping trips aren’t of much interest because he’s solely focused on his own quest, not on giving any insight into the wider offerings of a shop or town, e.g., Hay-on-Wye and Barter Books. But if you’re a fan of Shaun Bythell’s books you may well want to read this too. It’s also a window into the collector’s mindset: You know Royle is an extremist when you read that he once collected bread labels!

(Salt Publishing, July 2021.) With thanks to the publicist for the free copy for review.

Hilary: Briefly, A Delicious Life by Nell Stevens (I’d second that one; here’s

Hilary: Briefly, A Delicious Life by Nell Stevens (I’d second that one; here’s

A sweltering summer versus an encasing of ice; an ordinary day versus decades of futile waiting. Sackville explores these contradictions only to deflate them, collapsing time such that a polar explorer’s wife and her great-great-niece can inhabit the same literal and emotional space despite being separated by more than a century. When Edward Mackley went off on his expedition in the early 1900s, he left behind Emily, his devoted, hopeful new bride. She was to live out the rest of her days in the Mackley family home with her brother-in-law and his growing family; Edward never returned. Now Julia and her husband Simon reside in that same Victorian house, serving as custodians of memories and artifacts from her ancestors’ travels and naturalist observations. From one early morning until the next, we peer into this average marriage with its sadness and silences. On this day, Julia discovers a family secret, and late on reveals another of her own, that subtly change how we see her and Emily.

A sweltering summer versus an encasing of ice; an ordinary day versus decades of futile waiting. Sackville explores these contradictions only to deflate them, collapsing time such that a polar explorer’s wife and her great-great-niece can inhabit the same literal and emotional space despite being separated by more than a century. When Edward Mackley went off on his expedition in the early 1900s, he left behind Emily, his devoted, hopeful new bride. She was to live out the rest of her days in the Mackley family home with her brother-in-law and his growing family; Edward never returned. Now Julia and her husband Simon reside in that same Victorian house, serving as custodians of memories and artifacts from her ancestors’ travels and naturalist observations. From one early morning until the next, we peer into this average marriage with its sadness and silences. On this day, Julia discovers a family secret, and late on reveals another of her own, that subtly change how we see her and Emily. “The literature of nineteenth-century arctic exploration is full of coincidence and drama—last-minute rescues, a desperate rifle shot to secure food for starving men, secret letters written to painfully missed loved ones. There are moments of surreal stillness, as in Parry’s journal when he writes of the sound of the human voice in the land. And of tender ministration and quiet forbearance in the face of inevitable death.”

“The literature of nineteenth-century arctic exploration is full of coincidence and drama—last-minute rescues, a desperate rifle shot to secure food for starving men, secret letters written to painfully missed loved ones. There are moments of surreal stillness, as in Parry’s journal when he writes of the sound of the human voice in the land. And of tender ministration and quiet forbearance in the face of inevitable death.” In 2011 Rapp’s baby son Ronan was diagnosed with Tay-Sachs disease, a degenerative nerve condition that causes blindness, deafness, seizures, paralysis and, ultimately, death. Tay-Sachs is usually seen in Ashkenazi Jews, so it came as a surprise: Rapp and her husband Rick both had to be carriers, whereas only he was Jewish; they never thought to get tested.

In 2011 Rapp’s baby son Ronan was diagnosed with Tay-Sachs disease, a degenerative nerve condition that causes blindness, deafness, seizures, paralysis and, ultimately, death. Tay-Sachs is usually seen in Ashkenazi Jews, so it came as a surprise: Rapp and her husband Rick both had to be carriers, whereas only he was Jewish; they never thought to get tested. Things got worse before they got better. As is common for couples who lose a child, Rapp and her first husband separated, soon after she completed her book. In the six months leading up to Ronan’s death in February 2013, his condition deteriorated rapidly and he needed hospice caretakers. Rapp came close to suicide. But in those desperate months, she also threw herself into a new relationship with Kent, a 20-years-older man who was there for her as Ronan was dying and would become her second husband and the father of her daughter, Charlotte (“Charlie”). The acrimonious split from Rick and the astonishment of a new life with Kent – starting in the literal sanctuary of his converted New Mexico chapel, and then moving to California – were two sides of a coin. So were missing Ronan and loving Charlie.

Things got worse before they got better. As is common for couples who lose a child, Rapp and her first husband separated, soon after she completed her book. In the six months leading up to Ronan’s death in February 2013, his condition deteriorated rapidly and he needed hospice caretakers. Rapp came close to suicide. But in those desperate months, she also threw herself into a new relationship with Kent, a 20-years-older man who was there for her as Ronan was dying and would become her second husband and the father of her daughter, Charlotte (“Charlie”). The acrimonious split from Rick and the astonishment of a new life with Kent – starting in the literal sanctuary of his converted New Mexico chapel, and then moving to California – were two sides of a coin. So were missing Ronan and loving Charlie. Like Hannah Kent’s The Good People and Sarah Perry’s

Like Hannah Kent’s The Good People and Sarah Perry’s  These are essays for everyone who has had a mother – not just everyone who has been a mother. I enjoyed every piece separately, but together they form a vibrant collage of women’s experiences. Care has been taken to represent a wide range of situations and attitudes. The reflections are honest about physical as well as emotional changes, with midwife Leah Hazard (author of

These are essays for everyone who has had a mother – not just everyone who has been a mother. I enjoyed every piece separately, but together they form a vibrant collage of women’s experiences. Care has been taken to represent a wide range of situations and attitudes. The reflections are honest about physical as well as emotional changes, with midwife Leah Hazard (author of  Val McDermid and Jeanette Winterson are among the fans of this, Penguin’s lead debut title of 2020. When a young woman is found drowned at a popular suicide site in the Manchester area, the police plan to dismiss the case as an open-and-shut suicide. But the others at the women’s shelter where Katie Straw worked aren’t convinced, and for nearly the whole span of this taut psychological thriller readers are left to wonder if it was suicide or murder.

Val McDermid and Jeanette Winterson are among the fans of this, Penguin’s lead debut title of 2020. When a young woman is found drowned at a popular suicide site in the Manchester area, the police plan to dismiss the case as an open-and-shut suicide. But the others at the women’s shelter where Katie Straw worked aren’t convinced, and for nearly the whole span of this taut psychological thriller readers are left to wonder if it was suicide or murder. Poems to See by: A Comic Artist Interprets Great Poetry by Julian Peters

Poems to See by: A Comic Artist Interprets Great Poetry by Julian Peters

“Emergency police fire, or ambulance?” The young female narrator of this debut novel lives in Sydney and works for Australia’s emergency call service. Over her phone headset she gets appalling glimpses into people’s worst moments: a woman cowers from her abusive partner; a teen watches his body-boarding friend being attacked by a shark. Although she strives for detachment, her job can’t fail to add to her anxiety – already soaring due to the country’s flooding and bush fires.

“Emergency police fire, or ambulance?” The young female narrator of this debut novel lives in Sydney and works for Australia’s emergency call service. Over her phone headset she gets appalling glimpses into people’s worst moments: a woman cowers from her abusive partner; a teen watches his body-boarding friend being attacked by a shark. Although she strives for detachment, her job can’t fail to add to her anxiety – already soaring due to the country’s flooding and bush fires. With the Second World War only recently ended and nothing awaiting him apart from the coal mine where his father works, sixteen-year-old Robert Appleyard sets out on a journey. From his home in County Durham, he walks southeast, doing odd jobs along the way in exchange for food and lodgings. One day he wanders down a lane near Robin Hood’s Bay and gets a surprisingly warm welcome from a cottage owner, middle-aged Dulcie Piper, who invites him in for tea and elicits his story. Almost accidentally, he ends up staying for the rest of the summer, clearing scrub and renovating her garden studio.

With the Second World War only recently ended and nothing awaiting him apart from the coal mine where his father works, sixteen-year-old Robert Appleyard sets out on a journey. From his home in County Durham, he walks southeast, doing odd jobs along the way in exchange for food and lodgings. One day he wanders down a lane near Robin Hood’s Bay and gets a surprisingly warm welcome from a cottage owner, middle-aged Dulcie Piper, who invites him in for tea and elicits his story. Almost accidentally, he ends up staying for the rest of the summer, clearing scrub and renovating her garden studio.