Nonfiction November Book Pairings: Autistic Husbands & The Ocean

Liz is the host for this week’s Nonfiction November prompt. The idea is to choose a nonfiction book and pair it with a fiction title with which it has something in common.

I came up with these two based on my recent reading:

An Autistic Husband

The Rosie Effect by Graeme Simsion (also The Rosie Project and The Rosie Result)

&

Disconnected: Portrait of a Neurodiverse Marriage by Eleanor Vincent

Graeme Simsion’s Don Tillman trilogy tells the odd-couple story of an autistic professor and how he falls in love with and marries a wholly unsuitable neurotypical woman. He turns this situation into romantic comedy. For Eleanor Vincent, it wasn’t so funny. She met her third husband, computer scientist Lars (a pseudonym), through Zydeco dancing when she was in her sixties. Though aware that he could be unemotional and act strangely, she found him chivalrous and sweet. They dated for a time but he hurt and confused her by asking for his apartment keys back. After a five-year period she calls their “Interregnum,” the two got back together and married. Despite their years of friendship, she was completely unprepared for what living with him would be like. “At the age of seventy-one, I had married a stranger,” she writes.

Graeme Simsion’s Don Tillman trilogy tells the odd-couple story of an autistic professor and how he falls in love with and marries a wholly unsuitable neurotypical woman. He turns this situation into romantic comedy. For Eleanor Vincent, it wasn’t so funny. She met her third husband, computer scientist Lars (a pseudonym), through Zydeco dancing when she was in her sixties. Though aware that he could be unemotional and act strangely, she found him chivalrous and sweet. They dated for a time but he hurt and confused her by asking for his apartment keys back. After a five-year period she calls their “Interregnum,” the two got back together and married. Despite their years of friendship, she was completely unprepared for what living with him would be like. “At the age of seventy-one, I had married a stranger,” she writes.

It didn’t help that Covid hit partway through their four-year marriage, nor that they each received a cancer diagnosis (cervical vs. prostate). But the problems were more with their everyday differences in responses and processing. During their courtship, she ignored some bizarre things he did around her family: he bit her nine-year-old granddaughter as a warning of what would happen if she kept antagonizing their cat, and he put a gift bag over his head while they were at the dinner table with her siblings. These are a couple of the most egregious instances, but there are examples throughout of how Lars did things she didn’t understand. Through support groups and marriage counselling, she realized how well Lars had masked his autism when they were dating – and that he wasn’t willing to do the work required to make their marriage succeed. The book ends with them estranged but a divorce imminent.

If this were purely carping about a husband’s weirdness, it might have been tedious or depressing. But Vincent doesn’t blame Lars, and she incorporates so much else in this short memoir, including a number of topics that are of particular interest to me. There’s her PTSD from a traumatic upbringing, her parents’ identity as closeted gay people, the complications around her father’s death, the tragedy of her older daughter’s death, as well as the more everyday matters of being a working single parent, finding an affordable property in California’s Bay Area, and blending households.

If this were purely carping about a husband’s weirdness, it might have been tedious or depressing. But Vincent doesn’t blame Lars, and she incorporates so much else in this short memoir, including a number of topics that are of particular interest to me. There’s her PTSD from a traumatic upbringing, her parents’ identity as closeted gay people, the complications around her father’s death, the tragedy of her older daughter’s death, as well as the more everyday matters of being a working single parent, finding an affordable property in California’s Bay Area, and blending households.

Vincent crafts engaging scenes with solid recreated dialogue, and I especially liked the few meta chapters revealing “What I Left Out” – a memoir is always a shaped narrative, while life is messy; this shows both. She is also honest about her own failings and occasional bad behavior. I probably could have done with a little less detail on their sex life, however.

This had more relevance to me than expected. While my sister and I were clearing our mother’s belongings from the home she shared with her second husband for the 16 months between their wedding and her death, our stepsisters mentioned to us that they suspected their father was autistic. It was, as my sister said, a “lightbulb” moment, explaining so much about our respective parents’ relationship, and our interactions with him as well. My stepfather (who died just 10 months after my mother) was a dear man, but also maddening at times. A retired math professor, he was logical and flat of affect. Sometimes his humor was off-kilter and he made snap, unsentimental decisions that we couldn’t fathom. Had they gotten longer together, no doubt many of the issues Vincent experienced would have arisen. (Read via BookSirens)

[173 pages]

The Ocean

Playground by Richard Powers

&

Rachel Carson and the Power of Queer Love by Lida Maxwell

The Blue Machine by Helen Czerski

Under the Sea Wind by Rachel Carson

While I was less than enraptured with its artificial intelligence theme and narrative trickery, I loved the content about the splendour of the ocean in Richard Powers’s Booker Prize-longlisted Playground. Most of this comes via Evelyne Beaulieu, a charismatic French Canadian marine biologist (based in part on Sylvia Earle) who is on the first all-female submarine mission and is still diving in the South Pacific in her nineties. Powers explicitly references Rachel Carson’s The Sea Around Us. Between that and the revelation of Evelyne as a late-bloomer lesbian, I was reminded of Rachel Carson and the Power of Queer Love, a forthcoming novella-length academic study by Lida Maxwell that I have assessed for Foreword Reviews. Maxwell’s central argument is that Carson’s romantic love for a married woman, Dorothy Freeman, served as an awakening to wonder and connection and spurred her to write her greatest works.

While I was less than enraptured with its artificial intelligence theme and narrative trickery, I loved the content about the splendour of the ocean in Richard Powers’s Booker Prize-longlisted Playground. Most of this comes via Evelyne Beaulieu, a charismatic French Canadian marine biologist (based in part on Sylvia Earle) who is on the first all-female submarine mission and is still diving in the South Pacific in her nineties. Powers explicitly references Rachel Carson’s The Sea Around Us. Between that and the revelation of Evelyne as a late-bloomer lesbian, I was reminded of Rachel Carson and the Power of Queer Love, a forthcoming novella-length academic study by Lida Maxwell that I have assessed for Foreword Reviews. Maxwell’s central argument is that Carson’s romantic love for a married woman, Dorothy Freeman, served as an awakening to wonder and connection and spurred her to write her greatest works.

After reading Playground, I decided to place a library hold on Blue Machine by Helen Czerski (winner of the Wainwright Writing on Conservation Prize this year), which Powers acknowledges as an inspiration that helped him to think bigger. I have also pulled my copy of Under the Sea Wind by Rachel Carson off the shelf as it’s high time I read more by her.

Previous book pairings posts: 2018 (Alzheimer’s, female friendship, drug addiction, Greenland and fine wine!) and 2023 (Hardy’s Wives, rituals and romcoms).

Three on a Theme: English Gardeners (Bradbury, Laing and Mabey)

These three 2024 releases share a passion for gardening – but not the old-fashioned model of bending nature to one’s will to create aesthetically pleasing landscapes. Instead, the authors are also concerned with sustainability and want to do the right thing in a time of climate crisis (all three mention the 2022 drought, which saw the first 40 °C day being recorded in the UK). They seek to strike a balance between human interference and letting a site go wild, and they are cognizant of the wider political implications of having a plot of land of one’s own. All three were borrowed from the public library. #LoveYourLibrary

One Garden against the World: In Search of Hope in a Changing Climate by Kate Bradbury

Bradbury is Wildlife Editor of BBC Gardeners’ World Magazine and makes television appearances in the UK. She’s owned her suburban Brighton home for four years and has tried to turn its front and back gardens into havens, however small, for wildlife. The book covers April 2022 to June 2023, spotlighting the drought summer. “It’s about a little garden in south Portslade and one terrified, angry gardener.” Month by month, present-tense chapters form not quite a diary, but a record of what she’s planting, pruning, relocating, and so on. There is also a species profile at the end of each chapter, usually of an insect (as in the latest Dave Goulson book) – she’s especially concerned that she’s seeing fewer, yet she’s worried for local birds, trees and hedgehogs, too.

Often, she takes matters into her own hands. She plucks caterpillars from vegetation in the path of strimmers in the park and raises them at home; protects her garden’s robins from predators and provides enough food so they can nest and raise five fledglings; undertakes to figure out where her pond’s amphibians have come from; rescues hedgehogs; and bravely writes to neighbours who have scaffolding up (for roof repairs, etc.) beseeching them to put up swift boxes while they’re at it. Sometimes it works: a pub being refurbished by new owners happily puts up sparrow boxes when she tells them the birds have always nested in crevices in the building. Sometimes it doesn’t; people ignore her letters and she can’t seem to help but take it personally.

For individuals, it’s all too easy to be overtaken by anxiety, helplessness and despair, and Bradbury acknowledges that collective action and solidarity are vital. “I am reminded, once again, that it’s the community that will save these trees, not me. I’m reminded that community is everything.” She bands together with other environmentally minded people to resist a local development, educate the public about hedgehogs through talks, and oppose “Drone Bastard,” who flies drones at seagulls nesting on rooftops (not strictly illegal; disappointingly, their complaint doesn’t get anywhere with the police, RSPB or RSPCA).

Along the way, there are a few insights into the author’s personal life. She lives with her partner Emma and dog Tosca and accesses wild walks even right on the edge of a city in the Downs. Separate visits to her divorced parents are chances for more nature spotting – in Suffolk to see her father, she hears her first curlew and lapwings – but also involve some sadness, as her mother has aphasia and fatigue after a stroke.

Nearly every day of the chronology seems to bring more bad news for nature. “It’s hard, sometimes,” she admits, “trying to enjoy natural, wonderful events, trying to keep the clawing sense of unease at bay”. She is staunch in her fond stance: “I will love it, with all my heart, whatever has managed to remain, whatever is left.” And she models through her own amazingly biodiverse garden the ways we can extend refuge to other creatures if we throw out that pointless notion of ‘tidiness.’ “The UK’s 30 million gardens represent 30 million opportunities to create green spaces that hold on to water and carbon, create shade, grow food and provide habitats for wildlife that might otherwise not survive.” Reading this made me feel less guilty about the feral tangle of buddleia, ragwort, hemp agrimony and bindweed overtaking the parts of our back garden that aren’t given over to meadow, pond and hedge. Every time I venture back there I see tons of insects and spiders, and that’s all that matters.

My main critique is that one year would have been adequate, cutting the book to 250 pages rather than 300 and ensuring less repetition while still being a representative time period. But Bradbury is impressive for her vigilance and resolve. Some might say that she takes herself and life too seriously, but it’s really more that she’s aware of the scale of destruction already experienced and realistic about what we stand to lose. ![]()

The Garden Against Time: In Search of a Common Paradise by Olivia Laing

I consider Laing one of our most important public thinkers. I saw her introduce the book via the online Edinburgh Book Festival event “In Search of Eden,” in which she appeared on screen and was interviewed by JC Niala. Laing explained that this is not a totally new topic for her as she has been involved in environmental activism and in herbalism. But in 2020, when she and her much older husband bought a house in Suffolk – the first home she has owned after a life of renting – she started restoring its walled garden, which had been created in the 1960s by Mark Rumary. For a year, she watched and waited to see what would happen in the garden, only removing obvious weeds. This coincided with lockdown, so visits to gardens and archives were limited; she focused more on the creation of her own garden and travelling through literature. A two-year diary resulted, in seven notebooks.

Niala observed that the structure of the book, with interludes set in the Suffolk garden, means that the reader has a place to come back to between the deep dives into history. Why make a garden? she asked Laing. Beauty, pleasure, activity: these would be pat answers, Laing insisted. Instead, as with all her books, the reason is the impulse to make complicated structures. Repetitive tasks can be soothing; “the drudgery can be compelling as well.”

Laing spoke of a garden as both refuge and resistance, a mix of wild and cultivated. In this context, Derek Jarman’s Dungeness garden was a “wellspring of inspiration” for her, “a riposte to a toxic atmosphere” of nuclear power and the AIDS crisis (Rumary, like Jarman, was gay). It’s hard to tell where the beach ends and his garden begins, she noted, and she tried to make her garden similarly porous by kicking a hole in the door so frogs could get in. She hopes it will be both vulnerable and robust, a biodiversity hotspot. With Niala, she discussed the idea of a garden as a return to innocence. We have a “tarnished Eden” due to climate change, and we have to do what we can to reverse that.

The event was brilliant – just the level of detail I wanted, with Laing flitting between subjects and issuing amazingly intelligent soundbites. The book, though, seemed like page after page about Milton (Paradise Lost) and Iris Origo or the Italian Renaissance. I liked it best when it stayed personal to her family and garden project. There are incredible lyric passages, but just stringing together floral species’ names – though they’re lovely and almost incantatory – isn’t art; it also shuts out those of us who don’t know plants, who aren’t natural gardeners. I wasn’t about to Google every plant I didn’t know (though I did for a few). Also, I have read a lot about Derek Jarman in particular. So my reaction was admiration rather than full engagement, and I only gave the book a light skim in the end. It is striking, though, how she makes this subject political by drawing in equality of access and the climate crisis. (Shortlisted for the Kirkus Prize and the Wainwright Prize.) ![]()

Some memorable lines:

“A garden is a time capsule, as well as a portal out of time.”

“A garden is a balancing act, which can take the form of collaboration or outright war. This tension between the world as it is and the world as humans desire it to be is at the heart of the climate crisis, and as such the garden can be a place of rehearsal too, of experimenting with this relationship in new and perhaps less harmful ways.”

“the garden had become a counter to chaos on a personal as well as a political level”

“the more sinister legacy of Eden: the fantasy of perpetual abundance”

The Accidental Garden: Gardens, Wilderness and the Space in Between by Richard Mabey

Mabey gives a day-to-day description of a recent year on his two-acre Norfolk property, but also an overview of the past 20 years of change – which of course pretty much always equates to decline. He muses on wildflowers, growing a meadow and hedgerow, bird behaviour, butterfly numbers, and the weather becoming more erratic and extreme. What he sees at home is a reflection of what is going on in the world at large. “It would be glib to suggest that the immeasurably complex problems of a whole world are mirrored in the small confrontations and challenges of the garden. But maybe the mindset needed for both is the same: the generosity to reset the power balance between ourselves and the natural world.” He seeks to create “a fusion garden” of native and immigrant species, trying to intervene as little as possible. The goal is to tend the land responsibly and leave it better off than he found it. As with the Laing, I found many good passages, but overall I felt this was thin – perhaps reflecting his age and loss of mobility – or maybe a swan song. Again, I just skimmed, even though it’s only 160 pages.

Mabey gives a day-to-day description of a recent year on his two-acre Norfolk property, but also an overview of the past 20 years of change – which of course pretty much always equates to decline. He muses on wildflowers, growing a meadow and hedgerow, bird behaviour, butterfly numbers, and the weather becoming more erratic and extreme. What he sees at home is a reflection of what is going on in the world at large. “It would be glib to suggest that the immeasurably complex problems of a whole world are mirrored in the small confrontations and challenges of the garden. But maybe the mindset needed for both is the same: the generosity to reset the power balance between ourselves and the natural world.” He seeks to create “a fusion garden” of native and immigrant species, trying to intervene as little as possible. The goal is to tend the land responsibly and leave it better off than he found it. As with the Laing, I found many good passages, but overall I felt this was thin – perhaps reflecting his age and loss of mobility – or maybe a swan song. Again, I just skimmed, even though it’s only 160 pages. ![]()

Some memorable lines:

“being Earth’s creatures ourselves, we too have a right to a niche. So in our garden we’ve had more modest ambitions, for ‘parallel development’ you might say, and a sense of neighbourliness with our fellow organisms.”

“We feel embattled at times, and that we should try to make some sort of small refuge, a natural oasis.”

“A garden, with its complex interactions between humans and nature, is often seen as a metaphor for the wider world. But if so, is our plot a microcosm of this troubled arena or a refuge from it?”

You might think I would have been more satisfied by Mabey’s contemplative bent, or Laing’s wealth of literary and historical allusions. It turns out that when it comes to gardening, Bradbury’s practical approach was what I was after. But you may gravitate to any of these, depending on whether you want something for the hands, intellect or memory.

Love Your Library, September 2024

Thanks to Eleanor, Laura (here, here and here & Happy birthday!), Marcie and Naomi (here and here) for posting about their recent library reading!

On our holiday I popped into the Dunbar library (East Lothian, Scotland) while my husband was touring a nearby brewery. It seemed like a sweet and useful community centre, and I enjoyed the kid-friendly book returns box.

Last week my library removed its Perspex screens from around the three enquiry desks, nearly four years on from when they were put up during Covid.

I’m dipping into the Booker and Wainwright Prize shortlists through my library borrowing, and stocking up for R.I.P.

I appreciated this passage about libraries from Home Is Where We Start by Susanna Crossman:

Every week, from the age of seven, I walk the twenty minutes to the local library, and I borrow four books. My path takes me past the greengrocer’s, the newsagent’s, the butcher’s, the baker’s, the bank, the post office, and across the town square … Inside the library, high walls are lined with books, and when I’ve read all the Children’s section, the librarian lets me take the Adult books, but only the Classics. Back in my room at the community, I read for hours. Reading is one of my forms of resistance. … Books are my home, and when you turn the cover, you close one door and open another, moving to imagined worlds.

My library use over the last month:

(links to reviews not already featured on the blog)

READ

- One Garden against the World: In Search of Hope in a Changing Climate by Kate Bradbury

- Clear by Carys Davies

- Moominpappa at Sea by Tove Jansson

- The Song of the Whole Wide World: On Motherhood, Grief, and Poetry by Tamarin Norwood

- Strange Sally Diamond by Liz Nugent

- Heartstopper: Volume 1 by Alice Oseman (reread)

- Heartstopper: Volume 2 by Alice Oseman (reread)

- Heartstopper: Volume 3 by Alice Oseman (reread)

- Lumberjanes: Campfire Songs by Shannon Watters

- The Echoes by Evie Wyld

SKIMMED

- The Garden against Time: In Search of a Common Paradise by Olivia Laing

- The Accidental Garden: The Plot Thickens by Richard Mabey

CURRENTLY READING

- The Lone-Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven by Sherman Alexie

CURRENTLY READING-ish (more accurately, set aside temporarily)

- Death Valley by Melissa Broder

- The Tale of Despereaux by Kate DiCamillo

- Learning to Think: A Memoir about Faith, Demons, and the Courage to Ask Questions by Tracy King

- Groundbreakers: The Return of Britain’s Wild Boar by Chantal Lyons

- Unearthing: A Story of Tangled Love and Family Secrets by Kyo Maclear

- Late Light: Finding Home in the West Country by Michael Malay

- Mrs Gulliver by Valerie Martin

- After Dark by Haruki Murakami

- Stowaway: The Disreputable Exploits of the Rat by Joe Shute

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

- A Haunting on the Hill by Elizabeth Hand

- Dispersals: On Plants, Borders and Belonging by Jessica J. Lee

- Now She Is Witch by Kirsty Logan

- Held by Anne Michaels

- Heartstopper: Volume 4 by Alice Oseman (reread)

- It’s Not Just You: How to Navigate Eco-Anxiety and the Climate Crisis by Tori Tsui

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

- Orbital by Samantha Harvey

- Bothy: In Search of Simple Shelter by Kat Hill

- The Painter’s Daughters by Emily Howes

- Playground by Richard Powers

- The Place of Tides by James Rebanks

ON HOLD, TO BE PICKED UP

- The Glassmaker by Tracy Chevalier

- James by Percival Everett

- Small Rain by Garth Greenwell

- Intermezzo by Sally Rooney

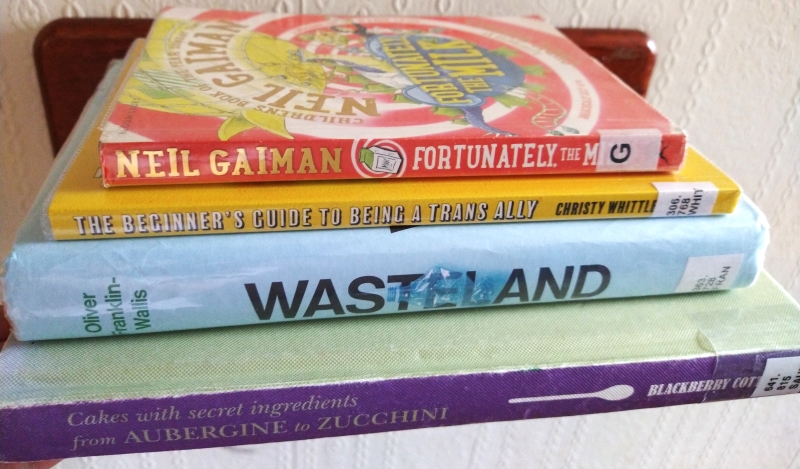

RETURNED UNREAD

- Wasteland: The Dirty Truth about What We Throw Away, Where It Goes, and Why It Matters by Oliver Franklin-Wallis – Twice I’ve had this out and failed to actually open it. I think I’m worried it will depress me.

- This Is My Sea by Miriam Mulcahy – A bereavement memoir with a swimming theme was sure to attract me, but the writing was blah. In fact, I think I may have borrowed this when it first came out in hardback and DNFed it then, too. Whoops!

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- The Forester’s Daughter by Claire Keegan (a standalone Faber short) – This didn’t seem very interesting, and I figure there is no point reading just one story from a whole unread collection.

- The Burial Plot by Elizabeth Macneal – I actually read 109 pages, then left it alone for weeks before it was requested off me. It was perfectly readable stuff but I kept feeling like I’d encountered this story before. It reminded me most of The Shadow Hour by Kate Riordan but was also trying for the edginess of early Sarah Waters. Now that I’ve DNFed Macneal’s two latest novels, I think it’s time to stop trying her.

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

20 Books of Summer, 14–16: Polly Atkin, Nan Shepherd and Susan Allen Toth

I’m still plugging away at the challenge. It’ll be down to the wire, but I should finish and review all 20 books by the 31st! Today I have a chronic illness memoir, a collection of poetry and prose pieces, and a reread of a cosy travel guide.

Some of Us Just Fall: On Nature and Not Getting Better by Polly Atkin (2023)

I was heartened to see this longlisted for the Wainwright Prize. It was a perfect opportunity to recognize the disabled/chronically ill experience of nature and the book achieves just what the award has recognised in recent years: the braiding together of life writing and place-based observation. (Wainwright has also done a great job on diversity this year: there are three books by BIPOC and five by women on the nature writing shortlist alone.)

Polly Atkin knew something was different about her body from a young age. She broke bones all the time, her first at 18 months when her older brother ran into her on his bicycle. But it wasn’t until her thirties that she knew what was wrong – Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and haemochromatosis – and developed strategies to mitigate the daily pain and the drains on her energy and mobility. “Correct diagnosis makes lives bearable,” she writes. “It gives you access to the right treatment. It gives you agency.”

Polly Atkin knew something was different about her body from a young age. She broke bones all the time, her first at 18 months when her older brother ran into her on his bicycle. But it wasn’t until her thirties that she knew what was wrong – Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and haemochromatosis – and developed strategies to mitigate the daily pain and the drains on her energy and mobility. “Correct diagnosis makes lives bearable,” she writes. “It gives you access to the right treatment. It gives you agency.”

The book assembles long-ish fragments, snippets from different points of her past alternating with what she sees on rambles near her home in Grasmere. She writes in some depth about Lake District literature: Thomas De Quincey as well as the Wordsworths – Atkin’s previous book is a biography of Dorothy Wordsworth that spotlights her experience with illness. In describing the desperately polluted state of Windermere, Atkin draws parallels with her condition (“Now I recognise my body as a precarious ecosystem”). Although she spurns the notion of the “Nature Cure,” swimming is a valuable therapy for her.

Theme justifies form here: “This is the chronic life, lived as repetition and variance, as sedimentation of broken moments, not as a linear progression.” For me, there was a bit too much particularity; if you don’t connect to the points of reference, there’s no way in and the danger arises of it all feeling indulgent. Besides, by the time I opened this I’d already read two Ehlers-Danlos memoirs (All My Wild Mothers by Victoria Bennett and Floppy by Alyssa Graybeal) and another reference soon came my way in The Invisible Kingdom by Meghan O’Rourke. So overfamiliarity was a problem. And by the time I forced myself to pick this off of my set-aside shelf and finish it, I’d read Nina Lohman’s stellar The Body Alone. For those newer to reading about chronic illness, though, especially if you also have an interest in the Lakes, it could be an eye-opener.

With thanks to Sceptre (Hodder) for the free copy for review.

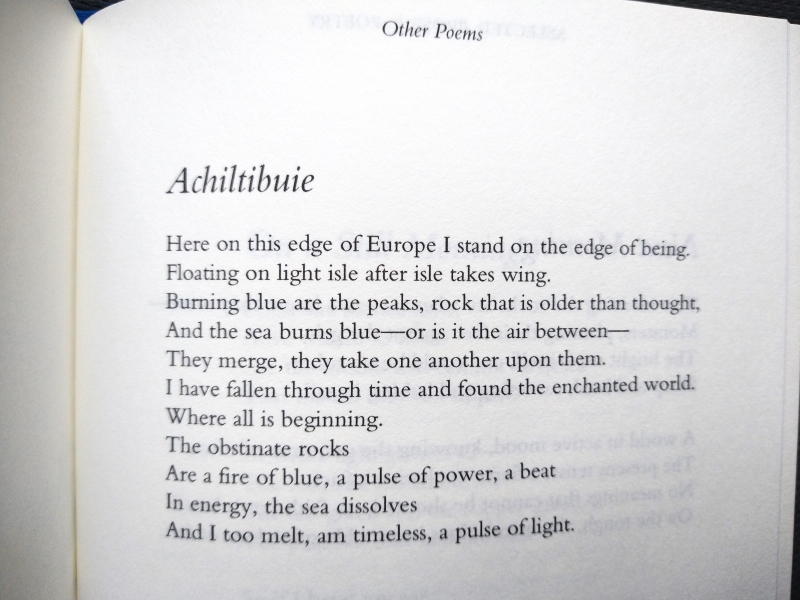

Selected Prose & Poetry by Nan Shepherd (2023)

I’d read and enjoyed Shepherd’s The Living Mountain, which has surged in popularity as an early modern nature writing classic thanks to Robert Macfarlane et al. I’m not sure I’d go as far as the executor of the Nan Shepherd Estate, though, who describes her in the Preface as “Taylor Swift in hiking boots.” The pieces reprinted here are from her one published book of poems, In the Cairngorms, and the mixed-genre collection Wild Geese. There is also a 28-page “novella,” Descent from the Cross. After World War I, Elizabeth, a workers’ rights organiser for a paper mill, marries a shell-shocked veteran who wants to write a book but isn’t sure he has either the genius or the dedication. It’s interesting that Shepherd would write about a situation where the wife has the economic upper hand, but the tragedy of the sickly failed author put me in mind of George Gissing or D.H. Lawrence, so didn’t feel fresh. Going by length alone, I would have called this a short story, but I understand why it would be designated a novella, for the scope.

I’d read and enjoyed Shepherd’s The Living Mountain, which has surged in popularity as an early modern nature writing classic thanks to Robert Macfarlane et al. I’m not sure I’d go as far as the executor of the Nan Shepherd Estate, though, who describes her in the Preface as “Taylor Swift in hiking boots.” The pieces reprinted here are from her one published book of poems, In the Cairngorms, and the mixed-genre collection Wild Geese. There is also a 28-page “novella,” Descent from the Cross. After World War I, Elizabeth, a workers’ rights organiser for a paper mill, marries a shell-shocked veteran who wants to write a book but isn’t sure he has either the genius or the dedication. It’s interesting that Shepherd would write about a situation where the wife has the economic upper hand, but the tragedy of the sickly failed author put me in mind of George Gissing or D.H. Lawrence, so didn’t feel fresh. Going by length alone, I would have called this a short story, but I understand why it would be designated a novella, for the scope.

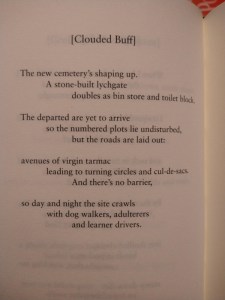

None of the miniature essays – field observations and character studies – stood out to me. About half of the book is given over to poetry. As with the nature writing, there is a feeling of mountain desolation. There are a lot of religious references and hints of the mystical, as in “The Bush,” which opens “In that pure ecstasy of light / The bush is burning bright. / Its substance is consumed away / And only form doth stay”. It’s a mixed bag: some feels very old-fashioned and sentimental, with every other line or, worse, every line rhyming, and some archaic wording and rather impenetrable Scots dialect. It could have been written 100 years before, by Robert Burns if not William Blake. But every so often there is a flash of brilliance. “Blackbird in Snow” is quite a nice one, and reminiscent of Thomas Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush.” I even found the cryptic lines from “Real Presence” that inspired a song on David Gray’s Skellig. My favourite poem by far was:

Overall, this didn’t engage me; it’s only for Shepherd fanatics and completists. (Won from Galileo Publishers in a Twitter giveaway)

England As You Like It: An Independent Traveler’s Companion by Susan Allen Toth (1995)

A reread. As I was getting ready to go overseas for the first time in the summer of 2003, Toth’s trilogy of memoirs whetted my appetite for travel in Britain. (They’re on my Landmark Books in My Life, Part II list.) This is the middle book and probably the least interesting in that it mostly recounts stays in particular favourite locations, such as Dorset, the Highlands, and various sites in Cornwall. However, I’ve never forgotten her “thumbprint theory,” which means staying a week or more in an area no larger than her thumb covers on a large-scale map, driving an hour or less for day trips. Not for her those cram-it-all-in trips where you race through multiple countries in a week (I have American friends who did Paris, London and Rome within six days, or five countries in eight days; blame it on stingy vacation policies, I guess). Instead, she wants to really bed into one place and have the time to make serendipitous discoveries such as an obscure museum or a rare opening of a private garden.

A reread. As I was getting ready to go overseas for the first time in the summer of 2003, Toth’s trilogy of memoirs whetted my appetite for travel in Britain. (They’re on my Landmark Books in My Life, Part II list.) This is the middle book and probably the least interesting in that it mostly recounts stays in particular favourite locations, such as Dorset, the Highlands, and various sites in Cornwall. However, I’ve never forgotten her “thumbprint theory,” which means staying a week or more in an area no larger than her thumb covers on a large-scale map, driving an hour or less for day trips. Not for her those cram-it-all-in trips where you race through multiple countries in a week (I have American friends who did Paris, London and Rome within six days, or five countries in eight days; blame it on stingy vacation policies, I guess). Instead, she wants to really bed into one place and have the time to make serendipitous discoveries such as an obscure museum or a rare opening of a private garden.

I most liked the early general chapters about how to make air travel bearable, her obsession with maps, her preference for self-catering, and her tendency to take home edible souvenirs. Of course, all the “Floating Facts” are hopelessly out-of-date. This being the early to mid-1990s, she had to order paper catalogues to browse cottage options (I still did this for honeymoon prep in 2006–7) and make international phone calls to book accommodation. She recommends renting somewhere from the National Trust or Landmark Trust. Ordnance Survey maps could be special ordered from the British Travel Bookshop in New York City. Entry fees averaged a few pounds. It’s all so quaint! An Anglo-American time capsule of sorts. I’ve always sensed a kindred spirit in Toth, and those whose taste runs toward the old-fashioned will probably also find her a charming tour guide. I’ve also reviewed the third book, England for All Seasons. (Free from The Book Thing of Baltimore)

Love Your Library, July 2024

Thanks so much to Eleanor, Laura and Marcie for posting about their recent library reads! It’s been a light library reading month for me, but I’m awaiting many holds of recent releases, including a coincidental gardening-themed trio that I fancy reviewing together if the timing works out.

Marcie also gifted me a New York Times article so that I could go through their list of the 100 Best Books of the 21st Century so far and see how many I have read. The answer is 53 (+ 6 DNFs), with another 23 on my TBR. I pulled some awardees off my shelves and might try reading them later this year (below right) – let me know if you’d like to buddy read any of them with me. I was pleased to see that the article first encouraged readers to reserve books from their local library before giving links to places where they can be bought.

It was fun to find libraries mentioned in a couple of library books I’ve been reading recently:

- Thanked in the Acknowledgements to Soldier Sailor by Claire Kilroy: “The librarians of Howth and Baldoyle who are part of the village that raises the child”.

- From Late Light by Michael Malay:

[When I was] a boy in Australia, my mother often took me to a library near our house, a small concrete building that stood across the road from a chicken shop and a video rental store. … the front door was slightly warped, making it difficult to pull open, while the carpet had been worn bare by years of footfall – and yet, to my fourteen- or fifteen-year-old self, it was a kind of palace. I would go there once or twice a week, roam the shelves on my own, gather all the books that appealed to me, and then take home as many titles as our library account would allow. I don’t think the books I chose were ever to my mother’s taste – at that time, I was obsessed with comics and fantasy novels – but she encouraged my enthusiasm anyway. … looking back now, I see that these books did other things for me – that they fed my curiosity, made time move in different ways, and opened up portals to other worlds. In all those years, I can’t remember my mother ever encouraging me to read more ‘serious’ or ‘literary’ books, and I continue to love her for that.

[When I was] a boy in Australia, my mother often took me to a library near our house, a small concrete building that stood across the road from a chicken shop and a video rental store. … the front door was slightly warped, making it difficult to pull open, while the carpet had been worn bare by years of footfall – and yet, to my fourteen- or fifteen-year-old self, it was a kind of palace. I would go there once or twice a week, roam the shelves on my own, gather all the books that appealed to me, and then take home as many titles as our library account would allow. I don’t think the books I chose were ever to my mother’s taste – at that time, I was obsessed with comics and fantasy novels – but she encouraged my enthusiasm anyway. … looking back now, I see that these books did other things for me – that they fed my curiosity, made time move in different ways, and opened up portals to other worlds. In all those years, I can’t remember my mother ever encouraging me to read more ‘serious’ or ‘literary’ books, and I continue to love her for that.

I’ve seen this Peanuts comic before and I love it. Isn’t library borrowing a brilliant concept?! All the more astounding when you step back to think about it anew. This was shared on Facebook by the library in the village where we go to church. Threatened with closure, it went independent. It has a building on peppercorn rent from the council and is run by volunteers. I don’t borrow books there because I can rarely visit during their limited opening hours (and I have plenty of other library books on my plate), but I do try to get to their book sales at least once or twice a year – particularly useful for stocking up on 3/£1 books for the book swapping game I run at our book club holiday social each year.

Tomorrow at 2 p.m. (if you’re in the UK, that is), the Booker Prize longlist will be announced. No doubt I’ll be baffled at all the books I’ve never heard of, or read. It happens every year. Perhaps I’ll be tempted enough by two or three nominees to place library holds on them right away.

My library use over the last month:

READ

- Fortunately, The Milk… by Neil Gaiman

SKIMMED

SKIMMED

- Rites of Passage: Death and Mourning in Victorian Britain by Judith Flanders

CURRENTLY READING

The Cove: A Cornish Haunting by Beth Lynch (I enjoyed her previous memoir)

The Cove: A Cornish Haunting by Beth Lynch (I enjoyed her previous memoir)- Groundbreakers: The Return of Britain’s Wild Boar by Chantal Lyons (Wainwright Prize longlist)

- Late Light: Finding Home in the West Country by Michael Malay (Wainwright Prize longlist)

- The Song of the Whole Wide World: On Motherhood, Grief, and Poetry by Tamarin Norwood (resuming this after it went out to fulfil an interlibrary loan)

CURRENTLY READING-ish (more accurately, set aside temporarily)

- Death Valley by Melissa Broder

- The Tale of Despereaux by Kate DiCamillo

- King: A Life by Jonathan Eig

- Mother’s Boy by Patrick Gale

- Learning to Think: A Memoir about Faith, Demons, and the Courage to Ask Questions by Tracy King

- Unearthing: A Story of Tangled Love and Family Secrets by Kyo Maclear

- Late Light: Finding Home in the West Country by Michael Malay

- Mrs Gulliver by Valerie Martin

- After Dark by Haruki Murakami

- Excellent Women by Barbara Pym

- Stowaway: The Disreputable Exploits of the Rat by Joe Shute

- Mrs Hemingway by Naomi Wood

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

- Wasteland: The Dirty Truth about What We Throw Away, Where It Goes, and Why It Matters by Oliver Franklin-Wallis

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

- Private Rites by Julia Armfield (I read 43% on Kindle and stalled so I’ll try again in print)

- One Garden against the World: In Search of Hope in a Changing Climate by Kate Bradbury

- The Painter’s Daughters by Emily Howes

- The Garden against Time: In Search of a Common Paradise by Olivia Laing

- The Accidental Garden: The Plot Thickens by Richard Mabey

- The Burial Plot by Elizabeth Macneal

- This Is My Sea by Miriam Mulcahy

- The Echoes by Evie Wyld

ON HOLD, TO BE PICKED UP

- Parade by Rachel Cusk

- Nature’s Ghosts: A History – and Future – of the Natural World by Sophie Yeo

RETURNED UNREAD

- Hungry Ghosts by Kevin Jared Hosein – A glance at the first few pages was enough to put me off.

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

This meme runs every month, on the final Monday. Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

August Releases: Bright Fear, Uprooting, The Farmer’s Wife, Windswept

This month I have three memoirs by women, all based on a connection to land – whether gardening, farming or crofting – and a sophomore poetry collection that engages with themes of pandemic anxiety as well as crossing cultural and gender boundaries.

My August highlight:

Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan

Chan’s Flèche was my favourite poetry collection of 2019. Their follow-up returns to many of the same foundational subjects: race, family, language and sexuality. But this time, the pandemic is a lens through which all is filtered. This is particularly evident in Part I, “Grief Lessons.” “London, 2020” and “Hong Kong, 2003,” on facing pages, contrast Covid-19 with SARS, the major threat when they were a teenager. People have always made assumptions about them based on their appearance or speech. At a time when Asian heritage merited extra suspicion, English was both a means of frank expression and a source of ambivalence:

“At times, English feels like the best kind of evening light. On other days, English becomes something harder, like a white shield.” (from “In the Beginning Was the Word”)

“my Chinese / face struck like the glow of a torch on a white question: / why is your English so good, the compliment uncertain / of itself.” (from “Sestina”)

At the centre of the book, “Ars Poetica,” a multi-part collage incorporating lines from other poets, forms a kind of autobiography in verse. Chan also questions the lines between genres, wondering whether to label their work poetry, nonfiction or fiction (“The novel feels like a springer spaniel running off-/leash the poem a warm basket it returns to always”).

At the centre of the book, “Ars Poetica,” a multi-part collage incorporating lines from other poets, forms a kind of autobiography in verse. Chan also questions the lines between genres, wondering whether to label their work poetry, nonfiction or fiction (“The novel feels like a springer spaniel running off-/leash the poem a warm basket it returns to always”).

The poems’ structure varies, with paragraphs and stanzas of different lengths and placement on the page (including, in one instance, a goblet shape). The enjambment, as you can see in lines I’ve quoted above and below, is noteworthy. Part III, “Field Notes on a Family,” reflects on the pressures of being an only child whose mother would prefer to pretend lives alone rather than with a female partner. The book ends with hope that Chan might be able to be open about their identity. The title references the paradoxical nature of the sublime, beautifully captured via the alliteration that closes “Circles”: “a commotion of coots convincing / me to withstand the quotidian tug-/of-war between terror and love.”

Although Flèche still has the edge for me, this is another excellent work I would recommend even to those wary of poetry.

Some more favourite lines, from “Ars Poetica”:

“What my mother taught me was how

to revere the light language emitted.”

“Home, my therapist suggests, is where

you don’t have to explain yourself.”

With thanks to Faber for the free copy for review.

Three land-based memoirs:

(All:  )

)

Uprooting: From the Caribbean to the Countryside – Finding Home in an English Country Garden by Marchelle Farrell

This Nan Shepherd Prize-winning memoir shares Chan’s attention to pandemic-era restrictions and how they prompt ruminations about identity and belonging. Farrell is from Trinidad but came to the UK as a student and has stayed, working as a psychiatrist and then becoming a wife and mother. Just before Covid hit, she moved to the outskirts of Bath and started rejuvenating her home’s large and neglected garden. Under thematic headings that also correspond to the four seasons, chapters are named after different plants she discovered or deliberately cultivated. The peace she finds in her garden helps her to preserve her mental health even though, with the deaths of George Floyd and so many other Black people, she is always painfully aware of her fragile status as a woman of colour, and sometimes feels trapped in the confining routines of homeschooling. I enjoyed the exploration of postcolonial family history and the descriptions of landscapes large and small but often found Farrell’s metaphors and psychological connections obvious or strained.

This Nan Shepherd Prize-winning memoir shares Chan’s attention to pandemic-era restrictions and how they prompt ruminations about identity and belonging. Farrell is from Trinidad but came to the UK as a student and has stayed, working as a psychiatrist and then becoming a wife and mother. Just before Covid hit, she moved to the outskirts of Bath and started rejuvenating her home’s large and neglected garden. Under thematic headings that also correspond to the four seasons, chapters are named after different plants she discovered or deliberately cultivated. The peace she finds in her garden helps her to preserve her mental health even though, with the deaths of George Floyd and so many other Black people, she is always painfully aware of her fragile status as a woman of colour, and sometimes feels trapped in the confining routines of homeschooling. I enjoyed the exploration of postcolonial family history and the descriptions of landscapes large and small but often found Farrell’s metaphors and psychological connections obvious or strained.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

The Farmer’s Wife: My Life in Days by Helen Rebanks

I fancied a sideways look at James Rebanks (The Shepherd’s Life and Wainwright Prize winner English Pastoral) and his regenerative farming project in the Lake District. (My husband spotted their dale from a mountaintop on holiday earlier in the month.) Helen Rebanks is a third-generation farmer’s wife and food and family are the most important things to her. One gets the sense that she has felt looked down on for only ever wanting to be a wife and mother. Her memoir, its recollections structured to metaphorically fall into a typical day, is primarily a defence of the life she has chosen, and secondarily a recipe-stuffed manifesto for eating simple, quality home cooking. (She paints processed food as the enemy.)

I fancied a sideways look at James Rebanks (The Shepherd’s Life and Wainwright Prize winner English Pastoral) and his regenerative farming project in the Lake District. (My husband spotted their dale from a mountaintop on holiday earlier in the month.) Helen Rebanks is a third-generation farmer’s wife and food and family are the most important things to her. One gets the sense that she has felt looked down on for only ever wanting to be a wife and mother. Her memoir, its recollections structured to metaphorically fall into a typical day, is primarily a defence of the life she has chosen, and secondarily a recipe-stuffed manifesto for eating simple, quality home cooking. (She paints processed food as the enemy.)

Growing up, Rebanks started cooking for her family early on, and got a job in a café as a teenager; her mother ran their farm home as a B&B but was forgetful to the point of being neglectful. She met James at 17 and accompanied him to Oxford, where they must have been the only student couple cooking and eating proper food. This period, when she was working an office job, baking cakes for a café, and mourning the devastating foot-and-mouth disease epidemic from a distance, is most memorable. Stories from travels, her wedding, and the births of her four children are pleasant enough, yet there’s nothing to make these experiences, or the telling of them, stand out. I wouldn’t make any of the dishes; most you could find a recipe for anywhere. Eleanor Crow’s black-and-white illustrations are lovely, though.

With thanks to Faber for the free copy for review.

Windswept: Life, Nature and Deep Time in the Scottish Highlands by Annie Worsley

I’d come across Worsley in the Wildlife Trusts’ Seasons anthologies. For a decade she has lived on Red River Croft, in a little-known pocket of northwest Scotland. In word pictures as much as in the colour photographs that illustrate this volume, she depicts it as a wild land shaped mostly by natural forces – also, sometimes, manmade. From one September to the next, she documents wildlife spectacles and the influence of weather patterns. Chronic illness sometimes limited her daily walks to the fence at the cliff-top. (But what a view from there!) There is more here about local history and ecology than any but the keenest Scotland-phile may be interested to read. Worsley also touches on her upbringing in polluted Lancashire, and her former academic career and fieldwork in Papua New Guinea. Her descriptions are full of colours and alliteration, though perhaps a little wordy: “Pale-gold autumnal days are spliced by fickle and feisty bouts of turbulent weather. … Sunrises and sunsets may pour with cinnabar and henna; dawn and dusk can ripple with crimson and purple.” The kind of writing I could appreciate for the length of an essay but not a whole book.

I’d come across Worsley in the Wildlife Trusts’ Seasons anthologies. For a decade she has lived on Red River Croft, in a little-known pocket of northwest Scotland. In word pictures as much as in the colour photographs that illustrate this volume, she depicts it as a wild land shaped mostly by natural forces – also, sometimes, manmade. From one September to the next, she documents wildlife spectacles and the influence of weather patterns. Chronic illness sometimes limited her daily walks to the fence at the cliff-top. (But what a view from there!) There is more here about local history and ecology than any but the keenest Scotland-phile may be interested to read. Worsley also touches on her upbringing in polluted Lancashire, and her former academic career and fieldwork in Papua New Guinea. Her descriptions are full of colours and alliteration, though perhaps a little wordy: “Pale-gold autumnal days are spliced by fickle and feisty bouts of turbulent weather. … Sunrises and sunsets may pour with cinnabar and henna; dawn and dusk can ripple with crimson and purple.” The kind of writing I could appreciate for the length of an essay but not a whole book.

With thanks to William Collins for the free copy for review.

Would you read one or more of these?

#WITMonth, Part II: Wioletta Greg, Dorthe Nors, Almudena Sánchez and More

My next four reads for Women in Translation month (after Part I here) were, again, a varied selection: a mixed volume of family history in verse and fragmentary diary entries, a set of nature/travel essays set mostly in Denmark, a memoir of mental illness, and a preview of a forthcoming novel about Mary Shelley’s inspirations for Frankenstein. One final selection will be coming up as part of my Love Your Library roundup on Monday.

(20 Books of Summer, #13)

Finite Formulae & Theories of Chance by Wioletta Greg (2014)

[Translated from the Polish by Marek Kazmierski]

I loved Greg’s Swallowing Mercury so much that I jumped at the chance to read something else of hers in English translation – plus this was less than half price AND a signed copy. I had no sense of the contents and might have reconsidered had I known a few things: the first two-thirds is family wartime history in verse, the rest is a fragmentary diary from eight years in which Greg lived on the Isle of Wight, and the book is a bilingual edition, with Polish and English on facing pages (for the poems) or one after the other (for the diary entries). I’m not sure what this format adds for English-language readers; I can’t know whether Kazmierski has rendered anything successfully. I’ve always thought it must be next to impossible to translate poetry, and it’s certainly hard to assess these as poems. They are fairly interesting snapshots from her family’s history, e.g., her grandfather’s escape from a stalag, and have quite precise vocabulary for the natural world. There’s also been an attempt to create or reproduce alliteration. I liked the poem the title phrase comes from, “A Fairytale about Death,” and “Readers.” The short diary entries, though, felt entirely superfluous. (New purchase – Waterstones bargain, 2023)

I loved Greg’s Swallowing Mercury so much that I jumped at the chance to read something else of hers in English translation – plus this was less than half price AND a signed copy. I had no sense of the contents and might have reconsidered had I known a few things: the first two-thirds is family wartime history in verse, the rest is a fragmentary diary from eight years in which Greg lived on the Isle of Wight, and the book is a bilingual edition, with Polish and English on facing pages (for the poems) or one after the other (for the diary entries). I’m not sure what this format adds for English-language readers; I can’t know whether Kazmierski has rendered anything successfully. I’ve always thought it must be next to impossible to translate poetry, and it’s certainly hard to assess these as poems. They are fairly interesting snapshots from her family’s history, e.g., her grandfather’s escape from a stalag, and have quite precise vocabulary for the natural world. There’s also been an attempt to create or reproduce alliteration. I liked the poem the title phrase comes from, “A Fairytale about Death,” and “Readers.” The short diary entries, though, felt entirely superfluous. (New purchase – Waterstones bargain, 2023)

(20 Books of Summer, #14)

A Line in the World: A Year on the North Sea Coast by Dorthe Nors (2021; 2022)

[Translated from the Danish by Caroline Waight]

Nors’s first nonfiction work is a surprise entry on this year’s Wainwright Prize nature writing shortlist. I’d be delighted to see this work in translation win, first because it would send a signal that it is not a provincial award, and secondly because her writing is stunning. Like Patrick Leigh Fermor, Aldo Leopold or Peter Matthiessen, she doesn’t just report what she sees but thinks deeply about what it means and how it connects to memory or identity. I have a soft spot for such philosophizing in nature and travel writing.

Nors’s first nonfiction work is a surprise entry on this year’s Wainwright Prize nature writing shortlist. I’d be delighted to see this work in translation win, first because it would send a signal that it is not a provincial award, and secondly because her writing is stunning. Like Patrick Leigh Fermor, Aldo Leopold or Peter Matthiessen, she doesn’t just report what she sees but thinks deeply about what it means and how it connects to memory or identity. I have a soft spot for such philosophizing in nature and travel writing.

You carry the place you come from inside you, but you can never go back to it.

I longed … to live my brief and arbitrary life while I still have it.

This eternal, fertile and dread-laden stream inside us. This fundamental question: do you want to remember or forget?

Nors lives in rural Jutland – where she grew up, before her family home was razed – along the west coast of Denmark, the same coast that reaches down to Germany and the Netherlands. In comparison to Copenhagen and Amsterdam, two other places she’s lived, it’s little visited and largely unknown to foreigners. This can be both good and bad. Tourists feel they’re discovering somewhere new, but the residents are insular – Nors is persona non grata for at least a year and a half simply for joking about locals’ exaggerated fear of wolves.

Local legends and traditions, bird migration, reliance on the sea, wanderlust, maritime history, a visit to church frescoes with Signe Parkins (the book’s illustrator), the year’s longest and shortest days … I started reading this months ago and set it aside for a time, so now find it difficult to remember what some of the essays are actually about. They’re more about the atmosphere, really: the remote seaside, sometimes so bleak as to seem like the ends of the earth. (It’s why I like reading about Scottish islands.) A bit more familiarity with the places Nors writes about would have pushed my rating higher, but her prose is excellent throughout. I also marked the metaphors “A local woman is standing there with a hairstyle like a wolverine” and “The sky looks like dirty mop-water.”

With thanks to Pushkin Press for the proof copy for review.

Pharmakon by Almudena Sánchez (2021; 2023)

[Translated from the Spanish by Katie Whittemore]

This is a memoir in micro-essays about the author’s experience of mental illness, as she tries to write herself away from suicidal thoughts. She grew up on Mallorca, always feeling like an outsider on an island where she wasn’t a native. Did her depression stem from her childhood, she wonders? She is also a survivor of ovarian cancer, diagnosed when she was 16. As her mind bounces from subject to subject, “trying to analyze a sick brain,” she documents her doctor visits, her medications, her dreams, her retweets, and much more. She takes inspiration from famous fellow depressives such as William Styron and Virginia Woolf. Her household is obsessed with books, she says, and it’s mostly through literature that she understands her life. The writing can be poetic, but few pieces stand out on the whole. My favourite opens: “Living in between anxiety and apathy has driven me to flowerpot decorating.”

This is a memoir in micro-essays about the author’s experience of mental illness, as she tries to write herself away from suicidal thoughts. She grew up on Mallorca, always feeling like an outsider on an island where she wasn’t a native. Did her depression stem from her childhood, she wonders? She is also a survivor of ovarian cancer, diagnosed when she was 16. As her mind bounces from subject to subject, “trying to analyze a sick brain,” she documents her doctor visits, her medications, her dreams, her retweets, and much more. She takes inspiration from famous fellow depressives such as William Styron and Virginia Woolf. Her household is obsessed with books, she says, and it’s mostly through literature that she understands her life. The writing can be poetic, but few pieces stand out on the whole. My favourite opens: “Living in between anxiety and apathy has driven me to flowerpot decorating.”

With thanks to Fum d’Estampa Press for the free copy for review.

And a bonus preview:

Mary and the Birth of Frankenstein by Anne Eekhout (2021; 2023)

[Translated from the Dutch by Laura Watkinson]

Anne Eekhout’s fourth novel and English-language debut is an evocative recreation of two momentous periods in Mary Shelley’s life that led – directly or indirectly – to the composition of her 1818 masterpiece. Drawing parallels between the creative process and motherhood and presenting a credibly queer slant on history, the book is full of eerie encounters and mysterious phenomena that replicate the Gothic science fiction tone of Frankenstein itself. The story lines are set in the famous “Year without a Summer” of 1816 (the storytelling challenge with Lord Byron) and during a period in 1812 that she spent living in Scotland with the Baxter family; Mary falls in love with the 17-year-old daughter, Isabella.

Anne Eekhout’s fourth novel and English-language debut is an evocative recreation of two momentous periods in Mary Shelley’s life that led – directly or indirectly – to the composition of her 1818 masterpiece. Drawing parallels between the creative process and motherhood and presenting a credibly queer slant on history, the book is full of eerie encounters and mysterious phenomena that replicate the Gothic science fiction tone of Frankenstein itself. The story lines are set in the famous “Year without a Summer” of 1816 (the storytelling challenge with Lord Byron) and during a period in 1812 that she spent living in Scotland with the Baxter family; Mary falls in love with the 17-year-old daughter, Isabella.

Coming out on 3 October from HarperVia. My full review for Shelf Awareness is pending.

Six Degrees of Separation: Romantic Comedy to Wild Fell

This is a fun meme I take part in every few months.

For August we begin with Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld, one of my top 2023 releases so far. (See Kate’s opening post.)

#1 Sittenfeld’s protagonist, Sally Milz, writes TV comedy, as does Kristin Newman (That ’70s Show, How I Met Your Mother, etc.), author of What I Was Doing While You Were Breeding, a lighthearted record of her travels and romantic conquests. (She even has a passage that reminds me of Sally’s Danny Horst Rule: “I looked like a thirty-year-old writer. Not like a twenty-year-old model or actress or epically legged songstress, which is a category into which an alarmingly high percentage of Angelenas fall. And, because the city is so lousy with these leggy aliens, regular- to below-average-looking guys with reasonable employment levels can actually get one, another maddening aspect of being a woman in this city.”)

#1 Sittenfeld’s protagonist, Sally Milz, writes TV comedy, as does Kristin Newman (That ’70s Show, How I Met Your Mother, etc.), author of What I Was Doing While You Were Breeding, a lighthearted record of her travels and romantic conquests. (She even has a passage that reminds me of Sally’s Danny Horst Rule: “I looked like a thirty-year-old writer. Not like a twenty-year-old model or actress or epically legged songstress, which is a category into which an alarmingly high percentage of Angelenas fall. And, because the city is so lousy with these leggy aliens, regular- to below-average-looking guys with reasonable employment levels can actually get one, another maddening aspect of being a woman in this city.”)

#2 I didn’t realize when I picked it up in a charity shop that my copy smelled strongly of cigarette smoke. I aired it in kitty litter, then by scented candles, and it still reeks. I reckon I can tolerate the smell long enough to finish it and put it in the Little Free Library, which gets good ventilation. A novel I acquired from the free bookshop we used to have in the mall in town was the only book I can remember having to get rid of before reading because it just smelled too bad (also of cigarettes in that case): My Sister’s Keeper by Jodi Picoult.

#2 I didn’t realize when I picked it up in a charity shop that my copy smelled strongly of cigarette smoke. I aired it in kitty litter, then by scented candles, and it still reeks. I reckon I can tolerate the smell long enough to finish it and put it in the Little Free Library, which gets good ventilation. A novel I acquired from the free bookshop we used to have in the mall in town was the only book I can remember having to get rid of before reading because it just smelled too bad (also of cigarettes in that case): My Sister’s Keeper by Jodi Picoult.

#3 So I didn’t read that, but I have read another Picoult novel, Sing You Home. The author is known for picking a central issue to address in each work, and in that one it was sexuality. Zoe, a music therapist, is married to Max but leaves him for Vanessa – and then decides to sue him for the use of the embryos they created together via IVF. It was the first book I’d read with that dynamic (a previously straight woman enters into a lesbian partnership), but by no means the last. Later came Untamed by Glennon Doyle, Hidden Nature by Alys Fowler, The Fixed Stars by Molly Wizenberg … and one you maybe weren’t expecting: the fantastic memoir First Time Ever by Peggy Seeger. The authors vary in how they account for it. They were gay all along but didn’t realize it? Their orientation changed? Or they just happened to fall in love with someone of the same gender? Seeger doesn’t explain at all, simply records how head-over-heels she was for Ewan MacColl … and then for Irene Pyper Scott.

#3 So I didn’t read that, but I have read another Picoult novel, Sing You Home. The author is known for picking a central issue to address in each work, and in that one it was sexuality. Zoe, a music therapist, is married to Max but leaves him for Vanessa – and then decides to sue him for the use of the embryos they created together via IVF. It was the first book I’d read with that dynamic (a previously straight woman enters into a lesbian partnership), but by no means the last. Later came Untamed by Glennon Doyle, Hidden Nature by Alys Fowler, The Fixed Stars by Molly Wizenberg … and one you maybe weren’t expecting: the fantastic memoir First Time Ever by Peggy Seeger. The authors vary in how they account for it. They were gay all along but didn’t realize it? Their orientation changed? Or they just happened to fall in love with someone of the same gender? Seeger doesn’t explain at all, simply records how head-over-heels she was for Ewan MacColl … and then for Irene Pyper Scott.

#4 Peggy Seeger is one of my heroes these days. I first got into her music through the lockdown livestreams put together by Folk on Foot and have since seen her live and acquired several of her albums, including a Smithsonian Folkways collection of her best-loved folk standards. One of these is, of course, “I’m Gonna Be an Engineer,” which was one of the inspirations for Claire Fuller’s Unsettled Ground.

#4 Peggy Seeger is one of my heroes these days. I first got into her music through the lockdown livestreams put together by Folk on Foot and have since seen her live and acquired several of her albums, including a Smithsonian Folkways collection of her best-loved folk standards. One of these is, of course, “I’m Gonna Be an Engineer,” which was one of the inspirations for Claire Fuller’s Unsettled Ground.

#5 Unsettled Ground, an unusual story of rural poverty and illiteracy, is set in a fictional village modelled on Inkpen, where Nicola Chester lives. Her memoir On Gallows Down, which held particular local interest for me, was shortlisted for the Wainwright Prize last year.

#5 Unsettled Ground, an unusual story of rural poverty and illiteracy, is set in a fictional village modelled on Inkpen, where Nicola Chester lives. Her memoir On Gallows Down, which held particular local interest for me, was shortlisted for the Wainwright Prize last year.

#6 Also shortlisted that year was Wild Fell by Lee Schofield, about his work at RSPB Haweswater. Like Chester, he’s been mired in the struggle to balance sustainable farming with conservation at a beloved place. And like a fellow Lakeland farmer (and previous Wainwright Prize winner for English Pastoral), James Rebanks, he’s trying to be respectful of tradition while also restoring valuable habitats. My husband and I each took a library copy of Wild Fell along to Cumbria last week (about which more anon) and packed it in a backpack for an on-location photo during our wild walk at the very atmospheric Haweswater.

#6 Also shortlisted that year was Wild Fell by Lee Schofield, about his work at RSPB Haweswater. Like Chester, he’s been mired in the struggle to balance sustainable farming with conservation at a beloved place. And like a fellow Lakeland farmer (and previous Wainwright Prize winner for English Pastoral), James Rebanks, he’s trying to be respectful of tradition while also restoring valuable habitats. My husband and I each took a library copy of Wild Fell along to Cumbria last week (about which more anon) and packed it in a backpack for an on-location photo during our wild walk at the very atmospheric Haweswater.

Where will your chain take you? Join us for #6Degrees of Separation! (Hosted on the first Saturday of each month by Kate W. of Books Are My Favourite and Best.) Next month’s starting book is Wifedom by Anna Funder.

Have you read any of my selections? Tempted by any you didn’t know before?

Prize Updates: McKitterick Prize Winner and Wainwright Prize Longlists

It was my second year as a first-round manuscript judge for the McKitterick Prize; have a look at my rundown of the shortlist here.

The winner, Louise Kennedy, and runner-up, Liz Hyder, were announced on 29 June. (Nominee Aamina Ahmad won a different SoA Award that night, the Gordon Bowker Volcano Prize for a novel focusing on the experience of travel away from home.) Other recipients included Travis Alabanza, Caroline Bird, Bonnie Garmus and Nicola Griffith. For more on all of this year’s SoA Award winners, see their website.

The winner, Louise Kennedy, and runner-up, Liz Hyder, were announced on 29 June. (Nominee Aamina Ahmad won a different SoA Award that night, the Gordon Bowker Volcano Prize for a novel focusing on the experience of travel away from home.) Other recipients included Travis Alabanza, Caroline Bird, Bonnie Garmus and Nicola Griffith. For more on all of this year’s SoA Award winners, see their website.

I’m a big fan of the Wainwright Prize for nature and conservation writing, and have been following it particularly closely since 2020, when I happened to read most of the nominees. In 2021 I also managed to read quite a lot from the longlists; 2022, the first year of an additional prize for children’s literature, saw me reading about a third of the total nominees.

This is the third year that I’ve been part of an “academy” of bloggers, booksellers, former judges and previously shortlisted authors asked to comment on a very long list of publisher submissions. I’m delighted that a few of my preferences made it through to the longlists.

My taste generally runs more to the narrative nature writing than the popular science or travel-based books. I find I’ve read just two from the Nature list (Bersweden and Huband) and one each from Conservation (Pavelle) and Children’s (Hargrave) so far.

The 2023 James Cropper Wainwright Prize for Nature Writing longlist:

- The Swimmer: The Wild Life of Roger Deakin, Patrick Barkham (Hamish Hamilton)

- The Flow: Rivers, Water and Wildness, Amy-Jane Beer (Bloomsbury)

- Where the Wildflowers Grow, Leif Bersweden (Hodder)

- Twelve Words for Moss, Elizabeth-Jane Burnett (Allen Lane)

- Cacophony of Bone, Kerri ní Dochartaigh (Canongate)

- Sea Bean, Sally Huband (Hutchinson)

- Ten Birds that Changed the World, Stephen Moss (Faber)

- A Line in the World: A Year on the North Sea Coast, Dorthe Nors, translated by Caroline Waight (Pushkin)

- The Golden Mole: And Other Living Treasure, Katherine Rundell, illustrated by Talya Baldwin (Faber)

- Belonging: Natural Histories of Place, Identity and Home, Amanda Thomson (Canongate)

- Why Women Grow: Stories of Soil, Sisterhood and Survival, Alice Vincent (Canongate)

- Landlines, Raynor Winn (Penguin)

The 2023 James Cropper Wainwright Prize for Writing on Conservation longlist:

- Sarn Helen: A Journey Through Wales, Past, Present and Future, Tom Bullough, illustrated by Jackie Morris (Granta)

- Beastly: A New History of Animals and Us, Keggie Carew (Canongate)

- Rewilding the Sea: How to Save Our Oceans, Charles Clover (Ebury)

- Birdgirl, Mya-Rose Craig (Jonathan Cape)

- The Orchid Outlaw, Ben Jacob (John Murray)

- Elixir: In the Valley at the End of Time, Kapka Kassabova (Jonathan Cape)

- Rooted: How Regenerative Farming Can Change the World, Sarah Langford (Viking)

- Black Ops and Beaver Bombing: Adventures with Britain’s Wild Mammals, Fiona Mathews and Tim Kendall (Oneworld)

- Forget Me Not, Sophie Pavelle (Bloomsbury)

- Fen, Bog, and Swamp: A Short History of Peatland Destruction and its Role in the Climate Crisis, Annie Proulx (Fourth Estate)

- The Lost Rainforests of Britain, Guy Shrubsole (HarperCollins)

- Nomad Century: How to Survive the Climate Upheaval, Gaia Vince (Allen Lane)

The 2023 James Cropper Wainwright Prize for Children’s Writing on Nature and Conservation longlist:

- The Earth Book, Hannah Alice (Nosy Crow)

- The Light in Everything, Katya Balen, illustrated by Sydney Smith (Bloomsbury)

- Billy Conker’s Nature-Spotting Adventure, Conor Busuttil (O’Brien)

- Protecting the Planet: The Season of Giraffes, Nicola Davies, illustrated by Emily Sutton (Walker)

- Blobfish, Olaf Falafel (Walker)

- A Friend to Nature, Laura Knowles, illustrated by Rebecca Gibbon (Welbeck)

- Spark, M G Leonard (Walker)

- A Wild Child’s Book of Birds, Dara McAnulty (Macmillan)

- Leila and the Blue Fox, Kiran Millwood Hargrave, illustrated by Tom de Freston (Hachette Children’s Group)

- The Zebra’s Great Escape, Katherine Rundell, illustrated by Sara Ogilvie (Bloomsbury)

- Archie’s Apple, Hannah Shuckburgh, illustrated by Octavia Mackenzie (Little Toller)

- Grandpa and the Kingfisher, Anna Wilson, illustrated by Sarah Massini (Nosy Crow)

It’s impressive that women writers are represented so well this year: 9/12 for Nature, 8/12 for Conservation, and 8/12 for Children’s. Amusingly, Katherine Rundell is on TWO of the lists. There are also, refreshingly, several BIPOC authors, and – I think for the first time ever – a work in translation (A Line in the World by Dorthe Nors, which I have as a set-aside proof copy and will get back into at once).

Here is where I have to admit that quite a number of the nominees, overall, are books I DNFed, authors whose work I’ve tried before and not enjoyed, or books I’ve been turned off of by the reviews. I’ll not mention these by name just now, and will leave any predictions for a future date when I’ve read a few more of the nominees. It seems that I’m most likely to catch up with the majority of the children’s longlist, if anything.

The shortlists will be announced on 10 August, and winners will be announced on 14 September at a 10th Anniversary live event held as part of the Kendal Mountain Festival in Cumbria (tickets available here).

See any nominees you’ve read? Who would you like to see shortlisted?

I died and went

I died and went I’ve read the first two chapters of a long-neglected review copy of All the Living and the Dead by Hayley Campbell (2022), in which she shadows various individuals who work in the death industry, starting with a funeral director and the head of anatomy services for the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. In Victorian times, corpses were stolen for medical students to practice on. These days, more people want to donate their bodies to science than can usually be accommodated. The Mayo Clinic receives upwards of 200 cadavers a year and these are the basis for many practical lessons as trainees prepare to perform surgery on the living. Campbell’s prose is journalistic, detailed and matter-of-fact, but I’m struggling with the very small type in my paperback. Upcoming chapters will consider a death mask sculptor, a trauma cleaner, a gravedigger, and more. If you’ve enjoyed Caitlin Doughty’s books, try this.

I’ve read the first two chapters of a long-neglected review copy of All the Living and the Dead by Hayley Campbell (2022), in which she shadows various individuals who work in the death industry, starting with a funeral director and the head of anatomy services for the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. In Victorian times, corpses were stolen for medical students to practice on. These days, more people want to donate their bodies to science than can usually be accommodated. The Mayo Clinic receives upwards of 200 cadavers a year and these are the basis for many practical lessons as trainees prepare to perform surgery on the living. Campbell’s prose is journalistic, detailed and matter-of-fact, but I’m struggling with the very small type in my paperback. Upcoming chapters will consider a death mask sculptor, a trauma cleaner, a gravedigger, and more. If you’ve enjoyed Caitlin Doughty’s books, try this. I’m halfway through Red Pockets: An Offering by Alice Mah (2025) from the library. I borrowed it because it was on the Wainwright Prize for Conservation Writing shortlist. During the Qingming Festival, the Chinese return to their hometowns to honour their ancestors. By sweeping their tombs and making offerings, they prevent the dead from coming back as hungry ghosts. When Mah, who grew up in Canada and now lives in Scotland, returns to South China with a cousin in 2017, she finds little trace of her ancestors but plenty of pollution and ecological degradation. Their grandfather wrote a memoir about his early life and immigration to Canada. In the present day, the cousins struggle to understand cultural norms such as gifting red envelopes of money to all locals. This is easy reading but slightly dull; it feels like Mah included every detail from her trips simply because she had the material, whereas memoirs need to be more selective. But I’m reminded of the works of Jessica J. Lee, which is no bad thing.