The Lost Supper by Taras Grescoe (Blog Tour)

“Searching for the Future of Food in the Flavors of the Past” is the instructive subtitle of this globe-trotting book of foodie exploration in the vein of A Cook’s Tour and The Omnivore’s Dilemma. With its firm grounding in history, it also reminded me of Twain’s Feast. Journalist Tara Grescoe is based in Montreal. Dodging Covid lockdowns, he managed to make visits to the homes of various traditional foods, such as the more nutritious emmer wheat that sustained the Çatalhöyük settlement in Turkey 8,500 years ago; the feral pigs that live on Ossabaw Island off of Georgia, USA: the Wensleydale cheese that has been made in Yorkshire for more than 700 years; the olive groves of Puglia; and the potato-like tuber called camas that is a staple for the Indigenous peoples of Vancouver Island.

One of the most fascinating chapters is about the quest to recreate “garum,” a fermented essence of salted fish (similar to modern-day Asian fish sauces) used ubiquitously by the Romans. Grescoe journeys to Cádiz, Spain, where the sauce is being made again in accordance with the archaeological findings at Pompeii. He experiences a posh restaurant tasting menu where garum features in every dish – even if just a few drops – and then has a go at making his own. “Garum seemed to subject each dish to the culinary equivalent of italicization,” he found, intensifying the existing flavours and giving an inimitable umami hit. I’m also intrigued by the possibilities of entomophagy (eating insects) so was interested in his hunt for water boatman eggs, “the caviar of Mexico”; and his outing to the world’s largest edible insect farm near Peterborough, Ontario.

Grescoe seems to be, like me, a flexitarian, focusing on plants but indulging in occasional high-quality meat and fish. He advocates for eating as locally as you can, and buying from small producers whose goods reflect the care taken over the raising. “Everybody who eats cheap, factory-made meat is eating suffering,” he insists, having compared an industrial-scale slaughterhouse in North Carolina with small farms of heritage pigs. He acknowledges other ecological problems, too, however, such as the Ossabaw hogs eating endangered loggerhead turtles’ eggs and the overabundance of sheep in the Yorkshire Dales leading to a loss of plant diversity. This ties into the ecological conscience that is starting to creep into foodie lit (as opposed to a passé Bourdain eat-everything mindset), as witnessed by Dan Saladino’s Eating to Extinction winning the Wainwright Prize (Conservation) last year.

Another major theme of the book is getting involved in the food production process yourself, however small the scale (growing herbs or tomatoes on a balcony, for instance). “With every home food-making skill I acquired, I felt like I was tapping into some deep wellspring of self-sufficiency that connected me to my historic—and even prehistoric—ancestors,” Grescoe writes. He also cites American farmer-philosopher Wendell Berry’s seven principles for responsible eating, as relevant now as they were in the 1980s. The book went a little deeper into history and anthropology than I needed, but there was still plenty here to hold my interest. Readers may not follow Grescoe into grinding their own wheat or making their own cheese, but we can all be more mindful about where our food comes from, showing gratitude rather than entitlement. This was a good Nonfiction November and pre-Thanksgiving read!

With thanks to Random Things Tours and Greystone Books for the proof copy for review.

Buy The Lost Supper from Bookshop UK [affiliate link]

I was delighted to be part of the blog tour for The Lost Supper. See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will be appearing soon.

The Rituals by Rebecca Roberts (Blog Tour)

Rebecca Roberts adapted her 2022 Welsh-language novel Y Defodau, her ninth, into The Rituals, which draws on her time working as a non-religious celebrant. Her protagonist, Gwawr Efa Taylor, is a freelance celebrant, too. The novel is presented as her notebook, containing diary entries as well as the text of some of the secular ceremonies she performs to mark rites of passage. We open on a funeral for a 39-year-old woman, then swiftly move on to a Bridezilla celebrity’s wedding that sours in a way that threatens to derail Gwawr’s entire career. A victim of sabotage, she’s doubly punished by gossip.

As she tries to piece her life back together, Gwawr finds support from many quarters, such as her beloved grandfather (Taid), a friend who invites her along on a writing retreat, her Welsh-language book club, a high school acquaintance, other customers and a sweet dog. She and the widower from the first funeral make a pact to start counselling at the same time to work through their grief – we know early on that she has experienced the devastating loss of Huw, but the details aren’t revealed until later. A couple of romantic prospects emerge for the 37-year-old, but also some uncomfortable reminders of past scandal.

There are heavy issues here, like alcoholism, infant loss and suicide, but they reflect the range of human experience and allow compassionate connections to form. Gwawr’s empathy is motivated by her bereavement: “That’s what keeps me going – knowing that I’ve turned the worst time of my life into something that helps other people. Taking the good from the bad.” You can see that attitude infusing her naming ceremonies and funerals. I’ll say no more about the plot, just that it prioritizes moments of high emotion and is both absorbing and touching.

I think this is only the second Welsh-language book I have read in translation (the first was The Life of Rebecca Jones by Angharad Price). It’s whetted my appetite for heading back to Wales for the first time since 2020 – we’re off to Hay-on-Wye on Friday. The Rituals is a tear-jerker for sure, but also sweet, romantic and realistic. I enjoyed it in much the same way I did The Collected Regrets of Clover by Mikki Brammer, and was pleased to try something from a small press that champions women’s writing.

With thanks to Random Things Tours and Honno Welsh Women’s Press for the proof copy for review.

Buy The Rituals from Bookshop.org [affiliate link]

I was delighted to be part of the blog tour for The Rituals. See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will be appearing soon.

Summer Fishing in Lapland by Juhani Karila (Blog Tour)

What a madcap adventure, set at the ends of the Earth. Though Elina Ylijaako’s father’s family home is in Lapland, when she travels up there from further south in Finland each summer she feels like an outsider. She has to run the gauntlet of weird locals in her mission to catch an enchanted pike from the mosquito-surrounded pond. The novel is set over five days – the length of time she has to be successful in her quest.

The stakes couldn’t be higher, but several legendary creatures are ranged against Elina: a knacky (some kind of water sprite?), a frakus, a raskel. All of them seem more mischievous than dangerous, but you never can tell. As in fairy tales, there are alliances and tricks and betrayals to come.

In the meantime, a female police detective named Janatuinen is newly arrived in town. Sections devoted to her, and flashbacks to Elina’s relationship with a school friend and first love interest, Jousia, widen the frame.

In the meantime, a female police detective named Janatuinen is newly arrived in town. Sections devoted to her, and flashbacks to Elina’s relationship with a school friend and first love interest, Jousia, widen the frame.

And then a rumour of further fantastical combatants, with the mayor possessed by a wraith that makes him ravenous all the time. Elina has to defeat the knacky and catch the pike, all while serving as bait for the locals’ broader plan to entrap the wraith…

I think Summer Fishing in Lapland may be only the fourth Finnish novel I’ve encountered, after Mr. Darwin’s Gardener by Kristina Carlson, The Year of the Hare by Arto Paasilinna, and Land of Snow and Ashes by Petra Rautiainen; it had the most in common with the Paasilinna, in terms of sheer oddness.

This is journalist Karila’s debut, first published in 2019. It’s been a bestseller in its native Finland. The press materials compared the work to Murakami, which was a draw. In the end I found it rather silly, but those more comfortable with fantasy may feel differently.

I did love the place descriptions, including some lovely incidental nature writing and unexpected metaphors: “Thick, dark clouds like the burnt bottom of a rice pudding were gathering there.” Is a summer trip to Lapland for you?

(Translated from the Finnish by Lola Rogers.)

With thanks to Pushkin Press for the proof copy for review.

I was happy to close out the blog tour for Summer Fishing in Lapland. See below for where other reviews have appeared, including Annabel’s, which is significantly more enthusiastic!

Salt & Skin by Eliza Henry-Jones (Blog Tour)

I was drawn to Eliza Henry-Jones’s fifth novel, Salt & Skin (2022), by the setting: the remote (fictional) island of Seannay in the Orkneys. It tells the dark, intriguing story of an Australian family lured in by magic and motivated by environmentalism. History overshadows the present as they come to realize that witch hunts are not just a thing of the past. This was exactly the right evocative reading for me to take on my trip to some other Scottish islands late last month. The setup reminded me of The Last Animal by Ramona Ausubel, while the novel as a whole is reminiscent of The Night Ship by Jess Kidd and Night Waking by Sarah Moss.

Only a week after the Managans – photographer Luda, son Darcy, 16, and daughter Min, 14 – arrive on the island, they witness a hideous accident. A sudden rockfall crushes a little girl, and Luda happens to have captured it all. The photos fulfill her task of documenting how climate change is affecting the islands, but she earns the locals’ opprobrium for allowing them to be published. It’s not the family’s first brush with disaster. The kids’ father died recently; whether in an accident or by suicide is unclear. Nor is it the first time Luda’s camera has gotten her into trouble. Darcy is still angry at her for selling a photograph she took of him in a dry dam years before, even though it raised a lot of money and awareness about drought.

The family live in what has long been known as “the ghost house,” and hints of magic soon seep in. Luda’s archaeologist colleague wants to study the “witch marks” at the house, and Darcy is among the traumatized individuals who can see others’ invisible scars. Their fate becomes tied to that of Theo, a young man who washed up on the shore ten years ago as a web-fingered foundling rumoured to be a selkie. Luda becomes obsessed with studying the history of the island’s witches, who were said to lure in whales. Min collects marine rubbish on her deep dives, learning to hold her breath for improbable periods. And Darcy fixates on Theo, who also attracts the interest of a researcher seeking to write a book about his origins.

It’s striking how Henry-Jones juxtaposes the current and realistic with the timeless and mystical. While the climate crisis is important to the framework, it fades into the background as the novel continues, with the focus shifting to the insularity of communities and outlooks. All of the characters are memorable, including the Managans’ elderly relative, Cassandra (calling to mind a prophetic figure from Greek mythology), though I found Father Lee, the meddlesome priest, aligned too readily with clichés. While the plot starts to become overwrought in later chapters, I appreciated the bold exploration of grief and discrimination, the sensitive attention to issues such as addiction and domestic violence, and the frank depictions of a gay relationship and an ace character. I wouldn’t call this a cheerful read by any means, but its brooding atmosphere will stick with me. I’d be keen to read more from Henry-Jones.

With thanks to Random Things Tours and September Publishing for the free copy for review.

Buy Salt & Skin from the Bookshop UK site. [affiliate link]

or

Pre-order Salt & Skin (U.S. release: September 5) from Bookshop.org. [affiliate link]

I was delighted to help kick off the blog tour for Salt & Skin on its UK publication day. See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will be appearing soon.

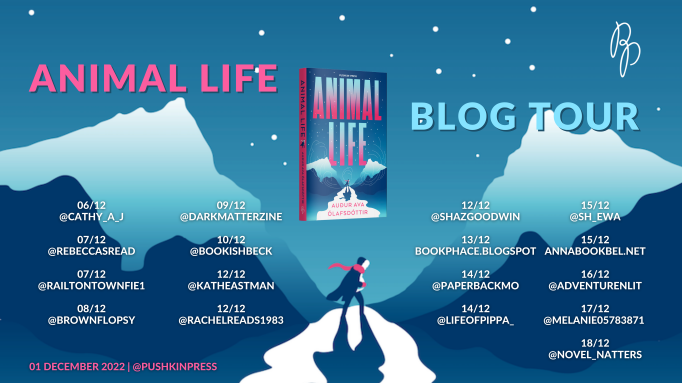

Animal Life by Auður Ava Ólafsdóttir

Icelandic author Auður Ava Ólafsdóttir was familiar to me from Butterflies in November (2013), a whimsical, feminist road trip novel I reviewed for For Books’ Sake. Dómhildur or “Dýja” is, like her grandaunt before her, a midwife – a word that was once voted Iceland’s most beautiful: ljósmóðir combines the words for light and mother, so it connotes “mother of light.” On the other side of the family, Dýja’s relatives are undertakers, a neat setup that sees her clan “handling people at their points of entry and exit.”

Along with her profession, Dýja inherited her great-aunt’s apartment, nine bottles of sherry, pen pal letters to a Welsh midwife and a box containing several discursive manuscripts of philosophical musings, one of them entitled Animal Life. In fragments from this book within the book, we see how her grandaunt recorded philosophical musings about coincidences and humanity in relation to other species, vacillating between the poetic and the scientific.

Along with her profession, Dýja inherited her great-aunt’s apartment, nine bottles of sherry, pen pal letters to a Welsh midwife and a box containing several discursive manuscripts of philosophical musings, one of them entitled Animal Life. In fragments from this book within the book, we see how her grandaunt recorded philosophical musings about coincidences and humanity in relation to other species, vacillating between the poetic and the scientific.

As Christmas – and an unprecedented storm prophesied by her meteorologist sister – approaches, Dýja starts to make the apartment less of a mausoleum and more her own home, trading lots of the fusty furniture for a colleague’s help with painting and decorating, and flirting with an Australian tourist who’s staying in the apartment upstairs. Outside of work she has never had much of a personal life, so she’s finally finding a better balance.

I really warmed to the grandaunt character and enjoyed the peppering of her aphorisms. As in novels like The Birth House and A Ghost in the Throat, it feels like this is a female wisdom, somewhat forbidden and witchy. The idea of it being passed down through the generations is appealing. We get less of a sense of Dýja overall, only late on finding that she has her own traumatic backstory. For a first-person narrator, she’s lacking the expected interiority. Mostly, we see her interactions with a random selection of minor characters such as an electrician whose wife is experiencing postpartum depression.

I felt there were a few too many disparate elements here, not all joined but just left on the page as a quirky smorgasbord. Still, it’s fun to try fiction in translation sometimes, especially when it’s of novella length. This also reminded me a bit of Weather and Brood.

Translated by Brian FitzGibbon. With thanks to Pushkin Press for my free copy for review.

I was delighted to be part of the blog tour for Animal Life. See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will be appearing soon.

UK Fungus Day: An Extract from Aliya Whiteley’s The Secret Life of Fungi

It’s UK Fungus Day today, and to mark the occasion I’m hosting an extract from The Secret Life of Fungi: Discoveries from a Hidden World by Aliya Whiteley, which came out in paperback last week.

“Nosing”

In 2001 two scientists published a report of a smell test they had conducted on thirty-six volunteers. The volunteers smelled an unspecified mushroom of the Dictyophora genus that was claimed to be incredibly rare, growing only on the lava floes of Hawaii. Six of the women taking part in the study reported experiencing a mild orgasm at the point of inhaling the smell; all the men said the mushroom smelled ‘fetid’.

It’s a tiny sample in an unrepeated experiment, but just the thought of it was enough to intrigue many. News outlets all over the world picked up the story and ran away with it. We don’t imagine that the sight of an object, any object, would be enough to induce such ecstasy, but the sense of smell is different. It cuddles up to our memories, performing the mysterious task of making us experience certain emotions. Nothing is as evocative as a scent thought forgotten. That might explain why we believe it’s possible to take the ultimate pleasure from one.

If some fungi smells are so intense to us, we can only wonder at how incredibly exciting they must be to animals with noses better than our own. A truffle, for instance – truffles have a scent so strong that it can give us headaches, and impregnate every corner of a kitchen so that everything tastes of it. The White Truffle, Tuber magnatum, is the most prized in the world for its rich, unique taste. It has long been foraged throughout Italy and Bosnia–Herzegovina, found buried underground, in the shadows of old trees, often oaks. Pigs were traditionally used to root them out, with an enthusiasm that could lead to the truffle being eaten before it could be retrieved for human consumption, so often dogs are trained to do the task nowadays.

The training of the best truffle hounds starts in puppyhood. There are different methods of reward and encouragement, but an initially expensive tactic outlined in the 1925 book The Romance of the Fungus World, by F.W. and R.T. Rolfe, sounds a great way to get a dog keen to go to work every morning. From early on in the puppy’s life, the Rolfes recommended mixing finely chopped truffle into its usual food, and then, once it has developed a taste for them, burying the truffles nearby and rewarding the puppy once it seeks them out. Then it’s only a matter of encouraging the puppy to give up the truffles in exchange for a piece of meat or a chunk of cheese. That sounds easy, but I have to wonder how straightforward that final step in the training regime might be. It would have to be a magnificent cheese to get my attention once I’d been indoctrinated with truffle love from an early age.

Pigs and dogs aren’t the only animals that love the smell of truffles. Rodents and insects too flock to the scent, and the Rolfes also mention the use of the truffle fly in the hunt for the good stuff. The larvae live in the truffle itself, so the tiny flies are said to hover there above the ground, usually in the evening, in clouds that can be spotted by those with keen eyesight. Is this one of those methods that has been lost? I can’t find any modern mention of it, and there are certainly more reliable methods of finding your truffles, but I love the idea of standing in the forest at sunset, in a glade of oak trees, bent double to look along the ground in the hope of spotting a cloud of flies to give away the position of a rare find.

With thanks to Elliott & Thompson for a free copy.

Chase of the Wild Goose, a playful, offbeat biographical novel about the Ladies of Llangollen, was first published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press in 1936. I was delighted to be invited to take part in an informal blog tour celebrating the book’s return to print (today, 1 February) as the inaugural publication of

Chase of the Wild Goose, a playful, offbeat biographical novel about the Ladies of Llangollen, was first published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press in 1936. I was delighted to be invited to take part in an informal blog tour celebrating the book’s return to print (today, 1 February) as the inaugural publication of