Review Catch-Up: Medical Nonfiction & Nature Poetry

Catching up on four review copies I was sent earlier in the year and have finally got around to finishing and writing about. I have two works of health-themed nonfiction, one a narrative about organ transplantation and the other a psychiatrist’s memoir; and two books of nature poetry, a centuries-spanning anthology and a recent single-author collection.

The Story of a Heart by Rachel Clarke

Rachel Clarke is a palliative care doctor and voice of wisdom on end-of-life issues. I was a huge fan of her Dear Life and admire her public critique of government policies that harm the NHS. (I’ve also reviewed Breathtaking, her account of hospital working during Covid-19.) While her three previous books all incorporate a degree of memoir, this is something different: narrative nonfiction based on a true story from 2017 and filled in with background research and interviews with the figures involved. Clarke has no personal connection to the case but, like many, discovered it via national newspaper coverage. Nine-year-old Max Johnson spent nearly a year in hospital with heart failure after a mysterious infection. Keira Ball, also nine, was left brain-dead when her family was in a car accident on a dangerous North Devon road. Keira’s heart gave Max a second chance at life.

Rachel Clarke is a palliative care doctor and voice of wisdom on end-of-life issues. I was a huge fan of her Dear Life and admire her public critique of government policies that harm the NHS. (I’ve also reviewed Breathtaking, her account of hospital working during Covid-19.) While her three previous books all incorporate a degree of memoir, this is something different: narrative nonfiction based on a true story from 2017 and filled in with background research and interviews with the figures involved. Clarke has no personal connection to the case but, like many, discovered it via national newspaper coverage. Nine-year-old Max Johnson spent nearly a year in hospital with heart failure after a mysterious infection. Keira Ball, also nine, was left brain-dead when her family was in a car accident on a dangerous North Devon road. Keira’s heart gave Max a second chance at life.

Clarke zooms in on pivotal moments: the accident, the logistics of getting an organ from one end of the country to another, and the separate recovery and transplant surgeries. She does a reasonable job of recreating gripping scenes despite a foregone conclusion. Because I’ve read a lot around transplantation and heart surgery (such as When Death Becomes Life by Joshua D. Mezrich and Heart by Sandeep Jauhar), I grew impatient with the contextual asides. I also found that the family members and medical professionals interviewed didn’t speak well enough to warrant long quotation. All in all, this felt like the stuff of a long-read magazine article rather than a full book. The focus on children also results in mawkishness. However, the Baillie Gifford Prize judges who shortlisted this clearly disagreed. I laud Clarke for drawing attention to organ donation, a cause dear to my family. This case was instrumental in changing UK law: one must now opt out of donating organs instead of registering to do so.

With thanks to Abacus Books (Little, Brown) for the proof copy for review.

You Don’t Have to Be Mad to Work Here: A Psychiatrist’s Life by Dr Benji Waterhouse

Waterhouse is also a stand-up comedian and is definitely channelling Adam Kay in his funny and touching debut memoir. Most chapters are pen portraits of patients and colleagues he has worked with. He also puts his own family under the microscope as he undergoes therapy to work through the sources of his anxiety and depression and tackles his reluctance to date seriously. In the first few years, he worked in a hospital and in community psychiatry, which involved house visits. Even though identifying details have been changed to make the case studies anonymous, Waterhouse manages to create memorable characters, such as Tariq, an unhoused man who travels with a dog (a pity Waterhouse is mortally afraid of dogs), and Sebastian, an outwardly successful City worker who had been minutes away from hanging himself before Waterhouse and his colleague rang on the door.

Waterhouse is also a stand-up comedian and is definitely channelling Adam Kay in his funny and touching debut memoir. Most chapters are pen portraits of patients and colleagues he has worked with. He also puts his own family under the microscope as he undergoes therapy to work through the sources of his anxiety and depression and tackles his reluctance to date seriously. In the first few years, he worked in a hospital and in community psychiatry, which involved house visits. Even though identifying details have been changed to make the case studies anonymous, Waterhouse manages to create memorable characters, such as Tariq, an unhoused man who travels with a dog (a pity Waterhouse is mortally afraid of dogs), and Sebastian, an outwardly successful City worker who had been minutes away from hanging himself before Waterhouse and his colleague rang on the door.

Along with such close shaves, there are tragic mistakes and tentative successes. But progress is difficult to measure. “Predicting human behaviour isn’t an exact science. We’re just relying on clinical assessment, a gut feeling and sometimes a prayer,” Waterhouse tells his medical student. The book gives a keen sense of the challenges of working for the NHS in an underfunded field, especially under Covid strictures. He is honest and open about his own failings but ends on the positive note of making advances in his relationship with his parents. This was a great read that I’d recommend beyond medical-memoir junkies like myself. Waterhouse has storytelling chops and the frequent one-liners lighten even difficult topics:

The sum total of my wisdom from time spent in the community: lots of people have complicated, shit lives.

Ambiguous statements … need clarification. Like when a depressed patient telephones to say they’re ‘in a bad place’. I need to check if they’re suicidal or just visiting Peterborough.

What is it about losing your mind that means you so often mislay your footwear too?

With thanks to Jonathan Cape (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Green Verse: An Anthology of Poems for Our Planet, ed. Rosie Storey Hilton

Part of the “In the Moment” series, this anthology of nature poetry has been arranged seasonally – spring through to winter – and, within season, roughly thematically. No context or biographical information is given on the poets apart from birth and death years for those not living. Selections from Emily Dickinson, William Shakespeare and W.B. Yeats thus share space with the work of contemporary and lesser-known poets. This is a similar strategy to the Wildlife Trusts’ Seasons anthologies, the ranging across time meant to suggest continuity in human engagement with the natural world. However, with a few exceptions (the above plus Thomas Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush” and Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “Inversnaid” are absolute classics, of course), the historical verse tends to be obscure, rhyming and sentimental; unfair to deem it all purple or doggerel, but sometimes bodies of work are forgotten for a reason. By contrast, I found many more standouts among the contemporary poets. Some favourites: “Cyanotype, by St Paul’s Cathedral” by Tamiko Dooley, “Eight Blue Notes” by Gillian Dawson (about eight species of butterfly), the gorgeously erotic “the bluebells are coming out & so am I” by Maya Blackwell, and “The Trees Don’t Know I’m Trans” by Eddy Quekett. It was also worthwhile to discover poems from other ancient traditions, such as haiku by Issa (“O Snail”) and wise aphoristic verse by Lao Tzu (“All things pass”). So, a bit of a mixed bag, but a nice introductory text for those newer to poetry.

Part of the “In the Moment” series, this anthology of nature poetry has been arranged seasonally – spring through to winter – and, within season, roughly thematically. No context or biographical information is given on the poets apart from birth and death years for those not living. Selections from Emily Dickinson, William Shakespeare and W.B. Yeats thus share space with the work of contemporary and lesser-known poets. This is a similar strategy to the Wildlife Trusts’ Seasons anthologies, the ranging across time meant to suggest continuity in human engagement with the natural world. However, with a few exceptions (the above plus Thomas Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush” and Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “Inversnaid” are absolute classics, of course), the historical verse tends to be obscure, rhyming and sentimental; unfair to deem it all purple or doggerel, but sometimes bodies of work are forgotten for a reason. By contrast, I found many more standouts among the contemporary poets. Some favourites: “Cyanotype, by St Paul’s Cathedral” by Tamiko Dooley, “Eight Blue Notes” by Gillian Dawson (about eight species of butterfly), the gorgeously erotic “the bluebells are coming out & so am I” by Maya Blackwell, and “The Trees Don’t Know I’m Trans” by Eddy Quekett. It was also worthwhile to discover poems from other ancient traditions, such as haiku by Issa (“O Snail”) and wise aphoristic verse by Lao Tzu (“All things pass”). So, a bit of a mixed bag, but a nice introductory text for those newer to poetry.

With thanks to Saraband for the free copy for review.

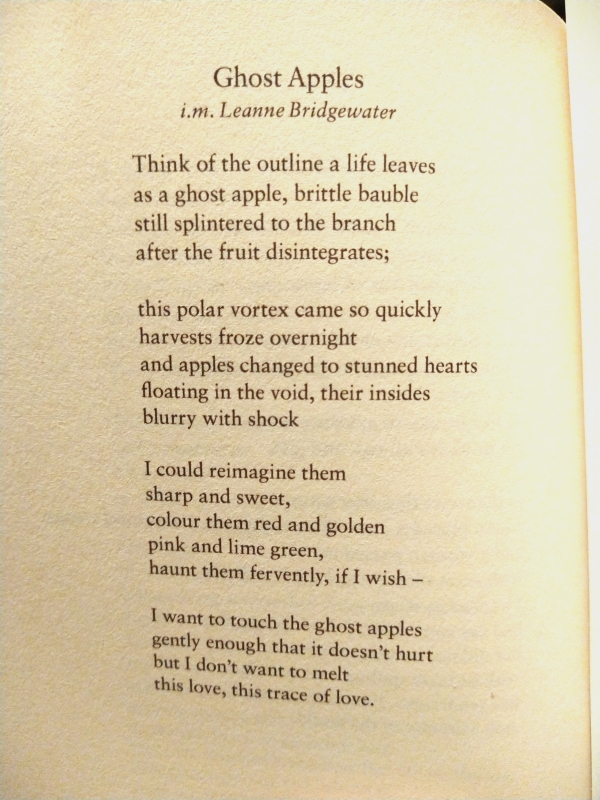

Dangerous Enough by Becky Varley-Winter (2023)

I requested this debut collection after hearing that it had been longlisted for the Laurel Prize for environmental poetry (funded by Simon Armitage, Poet Laureate). Varley-Winter crafts lovely natural metaphors for formative life experiences. Crows and wrens, foxes and fireflies, memories of a calf being born on a farm in Wales; gardens, greenhouses and long-lived orchids. These are the sorts of images that thread through poems about loss, parenting and the turmoil of lockdown. The last line or two of a poem is often especially memorable. It’s been months since I read this and I foolishly didn’t take any notes, so I haven’t retained more detail than that. But here is one shining example:

I requested this debut collection after hearing that it had been longlisted for the Laurel Prize for environmental poetry (funded by Simon Armitage, Poet Laureate). Varley-Winter crafts lovely natural metaphors for formative life experiences. Crows and wrens, foxes and fireflies, memories of a calf being born on a farm in Wales; gardens, greenhouses and long-lived orchids. These are the sorts of images that thread through poems about loss, parenting and the turmoil of lockdown. The last line or two of a poem is often especially memorable. It’s been months since I read this and I foolishly didn’t take any notes, so I haven’t retained more detail than that. But here is one shining example:

With thanks to Salt Publishing for the free copy for review.

Hard-Hitting Nonfiction I Read for #NovNov24: Hammad, Horvilleur, Houston & Solnit

I often play it safe with my nonfiction reading, choosing books about known and loved topics or ones that I expect to comfort me or reinforce my own opinions rather than challenge me. I wasn’t sure if I could bear to read about Israel/Palestine, or sexual violence towards women, but these four works were all worthwhile – even if they provoked many an involuntary gasp of horror (and mild expletives).

Recognising the Stranger: On Palestine and Narrative by Isabella Hammad (2024)

This is the text of the Edward W. Said Memorial Lecture that Hammad delivered at Columbia University on September 28, 2023. She posits that, in a time of crisis, storytelling can be a way of finding things out. Characters’ epiphanies, from Oedipus onward, see them encountering an Other but learning something about themselves in the process. In turning her great-grandfather’s life into her first novel, The Parisian, Hammad knew she had to avoid the pitfalls of nostalgia and unreliable memory. Fiction is always subjective, a matter of perspectives, and history is too. Sometimes the turning points will only be understood retrospectively.

This is the text of the Edward W. Said Memorial Lecture that Hammad delivered at Columbia University on September 28, 2023. She posits that, in a time of crisis, storytelling can be a way of finding things out. Characters’ epiphanies, from Oedipus onward, see them encountering an Other but learning something about themselves in the process. In turning her great-grandfather’s life into her first novel, The Parisian, Hammad knew she had to avoid the pitfalls of nostalgia and unreliable memory. Fiction is always subjective, a matter of perspectives, and history is too. Sometimes the turning points will only be understood retrospectively.

Edward Said (1935–2003) was a Palestinian American academic and theorist who helped found the field of postcolonial studies. Hammad writes that, for him, being Palestinian was “a condition of chronic exile.” She takes his humanist ideology as a model of how to “dismantle the consoling fictions of fixed identity, which make it easier to herd into groups.” About half of the lecture is devoted to the Israel/Palestine situation. She recalls meeting an Israeli army deserter a decade ago who told her how a naked Palestinian man holding the photograph of a child had approached his Gaza checkpoint; instead of shooting the man in the leg as ordered, he fled. It shouldn’t take such epiphanies to get Israelis to recognize Palestinians as human, but Hammad acknowledges the challenge in a “militarized society” of “state propaganda.”

This was, for me, more appealing than Hammad’s Enter Ghost. Though the essay might be better aloud as originally intended, I found it fluent and convincing. It was, however, destined to date quickly. Less than two weeks later, on October 7, there was a horrific Hamas attack on Israel (see Horvilleur, below). The print version of the lecture includes an afterword written in the wake of the destruction of Gaza. Hammad does not address October 7 directly, which seems fair (Hamas ≠ Palestine). Her language is emotive and forceful. She refers to “settler colonialism and ethnic cleansing” and rejects the argument that it is a question of self-defence for Israel – that would require “a fight between two equal sides,” which this absolutely is not. Rather, it is an example of genocide, supported by other powerful nations.

The present onslaught leaves no space for mourning

To remain human at this juncture is to remain in agony

It will be easy to say, in hindsight, what a terrible thing

The Israeli government would like to destroy Palestine, but they are mistaken if they think this is really possible … they can never complete the process, because they cannot kill us all.

(Read via Edelweiss) [84 pages] ![]()

How Isn’t It Going? Conversations after October 7 by Delphine Horvilleur (2025)

[Translated from the French by Lisa Appignanesi]

Horvilleur is one of just five female rabbis in France and is the leader of the country’s Liberal Jewish Movement. Earlier this year, I reviewed her essay collection Living with Our Dead, about attitudes toward death as illustrated by her family history, Jewish traditions and teachings, and funerals she has conducted. It is important to note that she expresses sorrow for Palestinians’ situation and mentions that she has always favoured a two-state solution. Moreover, she echoes Hammad with her final line, which hopes for “a future for those who think of the other, for those who engage in dialogue one with another, and with the humanity within them.” However, this is a lament for the Jewish condition, and a warning of the continuing and insidious nature of antisemitism. Who am I to judge her lived experience and say, “she’s being paranoid” or “it’s not really like that”? My job as reader is simply to listen.

Horvilleur is one of just five female rabbis in France and is the leader of the country’s Liberal Jewish Movement. Earlier this year, I reviewed her essay collection Living with Our Dead, about attitudes toward death as illustrated by her family history, Jewish traditions and teachings, and funerals she has conducted. It is important to note that she expresses sorrow for Palestinians’ situation and mentions that she has always favoured a two-state solution. Moreover, she echoes Hammad with her final line, which hopes for “a future for those who think of the other, for those who engage in dialogue one with another, and with the humanity within them.” However, this is a lament for the Jewish condition, and a warning of the continuing and insidious nature of antisemitism. Who am I to judge her lived experience and say, “she’s being paranoid” or “it’s not really like that”? My job as reader is simply to listen.

There is by turns a stream of consciousness or folktale quality to the narrative as Horvilleur enacts 11 dialogues – some real and others imagined – with her late grandparents, her children, or even abstractions (“Conversation with My Pain,” “Conversation with the Messiah”). She draws on history, scripture and her own life, wrestling with the kinds of thoughts that come to her during insomniac early mornings. It’s not all mourning; there is sometimes a wry sense of humour that feels very Jewish. While it was harder for me to relate to the point of view here, I admired the author for writing from her own ache and tracing the repeated themes of exile and persecution. It felt important to respect and engage. [125 pages] ![]()

With thanks to Europa Editions for the advanced e-copy for review.

Without Exception: Reclaiming Abortion, Personhood, and Freedom by Pam Houston (2024)

If you’re going to read a polemic, make sure it’s as elegantly written and expertly argued as this one. Houston responds to the overturning of Roe v. Wade with 60 micro-essays – one for each full year of her life – about what it means to be in a female body in a country that seeks to control and systematically devalue women. Roe was in force for 49 years, corresponding almost exactly to her reproductive years. She had three abortions and believes “childlessness might turn out to be the single greatest gift of my life.” Facts could serve as explanations: her grandmother died giving birth to her mother; her mother always said having her ruined her life; she was raped by her father from early childhood until she left home as a young adult; she is gender-fluid; she loves her life of adventure travel, spontaneity and chosen solitude; she adores the natural world and sees how overpopulation threatens it. But none are presented as causes or excuses. Houston is committed to nuance, recognizing individuality of circumstance and the primacy of choice.

If you’re going to read a polemic, make sure it’s as elegantly written and expertly argued as this one. Houston responds to the overturning of Roe v. Wade with 60 micro-essays – one for each full year of her life – about what it means to be in a female body in a country that seeks to control and systematically devalue women. Roe was in force for 49 years, corresponding almost exactly to her reproductive years. She had three abortions and believes “childlessness might turn out to be the single greatest gift of my life.” Facts could serve as explanations: her grandmother died giving birth to her mother; her mother always said having her ruined her life; she was raped by her father from early childhood until she left home as a young adult; she is gender-fluid; she loves her life of adventure travel, spontaneity and chosen solitude; she adores the natural world and sees how overpopulation threatens it. But none are presented as causes or excuses. Houston is committed to nuance, recognizing individuality of circumstance and the primacy of choice.

Many of the book’s vignettes are autobiographical, but others recount statistics, track American cultural and political shifts, and reprint excerpts from the 2022 joint dissent issued by the Supreme Court. The cycling of topics makes for an exquisite structure. Houston has done extensive research on abortion law and health care for women. A majority of Americans actually support abortion’s legality, and some states have fought back by protecting abortion rights through referenda. (I voted for Maryland’s. I’ve come a long way since my Evangelical, vociferously pro-life high school and college days.) I just love Houston’s work. There are far too many good lines here to quote. She is among my top recommendations of treasured authors you might not know. I’ve read her memoir Deep Creek and her short story collections Cowboys Are My Weakness and Waltzing the Cat, and I’m already sad that I only have four more books to discover. (Read via Edelweiss) [170 pages] ![]()

Men Explain Things to Me by Rebecca Solnit (2014)

Solnit did not coin the term “mansplaining,” but it was created not long after the title essay’s publication in 2008 and was definitely inspired by her depiction of a male know-it-all. She was at a party in Aspen in 2003 when a man decided to tell her all about an important new book he’d heard of about Eadweard Muybridge. A friend had to interrupt him and say, “That’s her book.” A funny story, yes, but illustrative of a certain male arrogance that encourages a woman’s “belief in her superfluity, an invitation to silence” and imagines her “in some sort of obscene impregnation metaphor, an empty vessel to be filled with their wisdom and knowledge.”

Solnit did not coin the term “mansplaining,” but it was created not long after the title essay’s publication in 2008 and was definitely inspired by her depiction of a male know-it-all. She was at a party in Aspen in 2003 when a man decided to tell her all about an important new book he’d heard of about Eadweard Muybridge. A friend had to interrupt him and say, “That’s her book.” A funny story, yes, but illustrative of a certain male arrogance that encourages a woman’s “belief in her superfluity, an invitation to silence” and imagines her “in some sort of obscene impregnation metaphor, an empty vessel to be filled with their wisdom and knowledge.”

This segues perfectly into “The Longest War,” about sexual violence against women, including rape and domestic violence. As in the Houston, there are some absolutely appalling statistics here. Yes, she acknowledges, it’s not all men, and men can be feminist allies, but there is a problem with masculinity when nearly all domestic violence and mass shootings are committed by men. There is a short essay on gay marriage and one (slightly out of place?) about Virginia Woolf’s mental health. The other five repeat some of the same messages about rape culture and believing women, so it is not a wholly classic collection for me, but the first two essays are stunners. (University library) [154 pages] ![]()

Have you read any of these authors? Or something else on these topics?

Nonfiction November: Two Memoirs of Biblical Living by Evans and Jacobs

I love a good year-challenge narrative and couldn’t resist considering these together because of the shared theme. Sure, there’s something gimmicky about a rigorously documented attempt to obey the Bible’s literal commandments as closely as possible in the modern day. But these memoirs arise from sincere motives, take cultural and theological matters seriously, and are a lot of fun to read.

The Year of Living Biblically: One Man’s Humble Quest to Follow the Bible as Literally as Possible by A.J. Jacobs (2007)

Jacobs came up with the idea, so I’ll start with him. His first book, The Know-It-All, was about absorbing as much knowledge as possible by reading the encyclopaedia. This starts in similarly intellectual fashion with a giant stack of Bible translations and commentaries. From one September to the next, Jacobs vows, he’ll do his best to understand and implement commandments from both the Old and New Testaments. It’s not a completely random choice of project in that he’s a secular Jew (“I’m Jewish in the same way the Olive Garden is an Italian restaurant. Which is to say: not very.”). Firstly, and most obviously, he stops shaving and getting haircuts. “As I write this, I have a beard that makes me resemble Moses. Or Abe Lincoln. Or [Unabomber] Ted Kaczynski. I’ve been called all three.” When he also takes to wearing all white, he really stands out on the New York subway system. Loving one’s neighbour isn’t easy in such an antisocial city, but he decides to try his best.

Jacobs is confused by the Bible’s combination of sensible moral guidelines and bizarre, arcane stuff. His conviction is that you can’t pick and choose – even if you don’t know why a law is important, you have to go with it. One of his “Top Five Most Perplexing Rules in the Bible” is a ban on clothing made of mixed fibers (shatnez). So he hires a shatnez tester, Mr. Berkowitz, who comes to investigate his entire wardrobe. To fulfil another obscure commandment, Berkowitz helps him ceremonially take an egg from a pigeon’s nest. Jacobs takes up prayer, hospitality, tithing, dietary restrictions, and avoiding women at the wrong time of the month. He gamely puts up a mezuzah, which displays a Bible passage above his doorframe. He even, I’m sorry to report, has a chicken sacrificed. Despite the proverb about not ‘sparing the rod’, he can’t truly bring himself to punish his son, so taps him gently with a Nerf bat; alas, Jasper thinks it’s a game. Stoning adulterers? Jacobs tosses pebbles at ankles.

Jacobs is confused by the Bible’s combination of sensible moral guidelines and bizarre, arcane stuff. His conviction is that you can’t pick and choose – even if you don’t know why a law is important, you have to go with it. One of his “Top Five Most Perplexing Rules in the Bible” is a ban on clothing made of mixed fibers (shatnez). So he hires a shatnez tester, Mr. Berkowitz, who comes to investigate his entire wardrobe. To fulfil another obscure commandment, Berkowitz helps him ceremonially take an egg from a pigeon’s nest. Jacobs takes up prayer, hospitality, tithing, dietary restrictions, and avoiding women at the wrong time of the month. He gamely puts up a mezuzah, which displays a Bible passage above his doorframe. He even, I’m sorry to report, has a chicken sacrificed. Despite the proverb about not ‘sparing the rod’, he can’t truly bring himself to punish his son, so taps him gently with a Nerf bat; alas, Jasper thinks it’s a game. Stoning adulterers? Jacobs tosses pebbles at ankles.

The book is a near-daily journal, with a new rule or three grappled with each day. There are hundreds of strange and culturally specific guidelines, but the heart issues – covetousness, lust – pose more of a challenge. Alongside his work as a journalist for Esquire and this project, Jacobs has family stuff going on: IVF results in his wife’s pregnancy with twin boys. Before they become a family of five, he manages to meet some Amish people, visit the Creation Museum, take a trip to the Holy Land to see a long-lost uncle, and engage in conversation with Evangelicals across the political spectrum, from Jerry Falwell’s megachurch to Tony Campolo (who died just last week). Jacobs ends up a “reverent agnostic.” We needn’t go to such extremes to develop the gratitude he feels by the end, but it sure is a hoot to watch him. This has just the sort of amusing, breezy yet substantial writing that should engage readers of Bill Bryson, Dave Gorman and Jon Ronson. (Free mall bookshop) ![]()

A Year of Biblical Womanhood: How a Liberated Woman Found Herself Sitting on Her Roof, Covering Her Head, and Calling Her Husband “Master” by Rachel Held Evans (2012)

Evans’s book proposal must have referenced Jacobs’s project, but she comes at things from a different perspective as a progressive Christian, and likely had a separate audience in mind. Namely, the sort of people who worry about the concept of biblical womanhood and wrestle with Bible verses about women remaining silent in church and not holding positions of religious leadership over men. There are indeed factions of Christianity that take these passages literally. Given that she was a public speaker and popular theologian, Evans obviously didn’t. But in her native Alabama and her new home of Tennessee, many would. She decides to look more closely at some of the prescriptions for women in the scriptures, focusing on Proverbs 31, which describes the “woman of valor.” She looks at this idealized woman’s characteristics in turn and tries to adhere to them by dressing modestly, taking etiquette lessons, learning to cook and hosting dinners, and practicing for parenthood with a “Baby-Think-It-Over” doll. Like Jacobs, she stops cutting her hair and meets some Amish people. But she also sleeps outside in a tent while menstruating and undertakes silent meditation at an abbey and a mission trip to Bolivia. Each monthly chapter ends with a profile of a female character from the Bible and what might be learned from her story.

Evans’s book proposal must have referenced Jacobs’s project, but she comes at things from a different perspective as a progressive Christian, and likely had a separate audience in mind. Namely, the sort of people who worry about the concept of biblical womanhood and wrestle with Bible verses about women remaining silent in church and not holding positions of religious leadership over men. There are indeed factions of Christianity that take these passages literally. Given that she was a public speaker and popular theologian, Evans obviously didn’t. But in her native Alabama and her new home of Tennessee, many would. She decides to look more closely at some of the prescriptions for women in the scriptures, focusing on Proverbs 31, which describes the “woman of valor.” She looks at this idealized woman’s characteristics in turn and tries to adhere to them by dressing modestly, taking etiquette lessons, learning to cook and hosting dinners, and practicing for parenthood with a “Baby-Think-It-Over” doll. Like Jacobs, she stops cutting her hair and meets some Amish people. But she also sleeps outside in a tent while menstruating and undertakes silent meditation at an abbey and a mission trip to Bolivia. Each monthly chapter ends with a profile of a female character from the Bible and what might be learned from her story.

It’s a sweet, self-deprecating book. You can definitely tell that she was only 29 at the time she started her project. It’s okay with me that Evans turned all her literal intentions into more metaphorical applications by the end of the year. She concludes that the Church has misused Proverbs 31: “We abandoned the meaning of the poem by focusing on the specifics, and it became just another impossible standard by which to measure our failures. We turned an anthem into an assignment, a poem into a job description.” Her determination is not to obsess over rules but to continue with the habits that benefited her spiritual life, and to champion women whenever she can. I suspect this is a lesser entry from Evans’s oeuvre. She died too soon – suddenly in 2019, of brain swelling after a severe allergic reaction to an antibiotic – but remains a valued voice, and I’ll catch up on the rest of her books. Searching for Sunday, for instance, was great, and I’m keen to read Evolving in Monkey Town (about living in Dayton, Tennessee, where the famous Scopes Monkey Trial took place). (Birthday gift from my wish list, 2023) ![]()

Nonfiction November Book Pairings: Autistic Husbands & The Ocean

Liz is the host for this week’s Nonfiction November prompt. The idea is to choose a nonfiction book and pair it with a fiction title with which it has something in common.

I came up with these two based on my recent reading:

An Autistic Husband

The Rosie Effect by Graeme Simsion (also The Rosie Project and The Rosie Result)

&

Disconnected: Portrait of a Neurodiverse Marriage by Eleanor Vincent

Graeme Simsion’s Don Tillman trilogy tells the odd-couple story of an autistic professor and how he falls in love with and marries a wholly unsuitable neurotypical woman. He turns this situation into romantic comedy. For Eleanor Vincent, it wasn’t so funny. She met her third husband, computer scientist Lars (a pseudonym), through Zydeco dancing when she was in her sixties. Though aware that he could be unemotional and act strangely, she found him chivalrous and sweet. They dated for a time but he hurt and confused her by asking for his apartment keys back. After a five-year period she calls their “Interregnum,” the two got back together and married. Despite their years of friendship, she was completely unprepared for what living with him would be like. “At the age of seventy-one, I had married a stranger,” she writes.

Graeme Simsion’s Don Tillman trilogy tells the odd-couple story of an autistic professor and how he falls in love with and marries a wholly unsuitable neurotypical woman. He turns this situation into romantic comedy. For Eleanor Vincent, it wasn’t so funny. She met her third husband, computer scientist Lars (a pseudonym), through Zydeco dancing when she was in her sixties. Though aware that he could be unemotional and act strangely, she found him chivalrous and sweet. They dated for a time but he hurt and confused her by asking for his apartment keys back. After a five-year period she calls their “Interregnum,” the two got back together and married. Despite their years of friendship, she was completely unprepared for what living with him would be like. “At the age of seventy-one, I had married a stranger,” she writes.

It didn’t help that Covid hit partway through their four-year marriage, nor that they each received a cancer diagnosis (cervical vs. prostate). But the problems were more with their everyday differences in responses and processing. During their courtship, she ignored some bizarre things he did around her family: he bit her nine-year-old granddaughter as a warning of what would happen if she kept antagonizing their cat, and he put a gift bag over his head while they were at the dinner table with her siblings. These are a couple of the most egregious instances, but there are examples throughout of how Lars did things she didn’t understand. Through support groups and marriage counselling, she realized how well Lars had masked his autism when they were dating – and that he wasn’t willing to do the work required to make their marriage succeed. The book ends with them estranged but a divorce imminent.

If this were purely carping about a husband’s weirdness, it might have been tedious or depressing. But Vincent doesn’t blame Lars, and she incorporates so much else in this short memoir, including a number of topics that are of particular interest to me. There’s her PTSD from a traumatic upbringing, her parents’ identity as closeted gay people, the complications around her father’s death, the tragedy of her older daughter’s death, as well as the more everyday matters of being a working single parent, finding an affordable property in California’s Bay Area, and blending households.

If this were purely carping about a husband’s weirdness, it might have been tedious or depressing. But Vincent doesn’t blame Lars, and she incorporates so much else in this short memoir, including a number of topics that are of particular interest to me. There’s her PTSD from a traumatic upbringing, her parents’ identity as closeted gay people, the complications around her father’s death, the tragedy of her older daughter’s death, as well as the more everyday matters of being a working single parent, finding an affordable property in California’s Bay Area, and blending households.

Vincent crafts engaging scenes with solid recreated dialogue, and I especially liked the few meta chapters revealing “What I Left Out” – a memoir is always a shaped narrative, while life is messy; this shows both. She is also honest about her own failings and occasional bad behavior. I probably could have done with a little less detail on their sex life, however.

This had more relevance to me than expected. While my sister and I were clearing our mother’s belongings from the home she shared with her second husband for the 16 months between their wedding and her death, our stepsisters mentioned to us that they suspected their father was autistic. It was, as my sister said, a “lightbulb” moment, explaining so much about our respective parents’ relationship, and our interactions with him as well. My stepfather (who died just 10 months after my mother) was a dear man, but also maddening at times. A retired math professor, he was logical and flat of affect. Sometimes his humor was off-kilter and he made snap, unsentimental decisions that we couldn’t fathom. Had they gotten longer together, no doubt many of the issues Vincent experienced would have arisen. (Read via BookSirens)

[173 pages]

The Ocean

Playground by Richard Powers

&

Rachel Carson and the Power of Queer Love by Lida Maxwell

The Blue Machine by Helen Czerski

Under the Sea Wind by Rachel Carson

While I was less than enraptured with its artificial intelligence theme and narrative trickery, I loved the content about the splendour of the ocean in Richard Powers’s Booker Prize-longlisted Playground. Most of this comes via Evelyne Beaulieu, a charismatic French Canadian marine biologist (based in part on Sylvia Earle) who is on the first all-female submarine mission and is still diving in the South Pacific in her nineties. Powers explicitly references Rachel Carson’s The Sea Around Us. Between that and the revelation of Evelyne as a late-bloomer lesbian, I was reminded of Rachel Carson and the Power of Queer Love, a forthcoming novella-length academic study by Lida Maxwell that I have assessed for Foreword Reviews. Maxwell’s central argument is that Carson’s romantic love for a married woman, Dorothy Freeman, served as an awakening to wonder and connection and spurred her to write her greatest works.

While I was less than enraptured with its artificial intelligence theme and narrative trickery, I loved the content about the splendour of the ocean in Richard Powers’s Booker Prize-longlisted Playground. Most of this comes via Evelyne Beaulieu, a charismatic French Canadian marine biologist (based in part on Sylvia Earle) who is on the first all-female submarine mission and is still diving in the South Pacific in her nineties. Powers explicitly references Rachel Carson’s The Sea Around Us. Between that and the revelation of Evelyne as a late-bloomer lesbian, I was reminded of Rachel Carson and the Power of Queer Love, a forthcoming novella-length academic study by Lida Maxwell that I have assessed for Foreword Reviews. Maxwell’s central argument is that Carson’s romantic love for a married woman, Dorothy Freeman, served as an awakening to wonder and connection and spurred her to write her greatest works.

After reading Playground, I decided to place a library hold on Blue Machine by Helen Czerski (winner of the Wainwright Writing on Conservation Prize this year), which Powers acknowledges as an inspiration that helped him to think bigger. I have also pulled my copy of Under the Sea Wind by Rachel Carson off the shelf as it’s high time I read more by her.

Previous book pairings posts: 2018 (Alzheimer’s, female friendship, drug addiction, Greenland and fine wine!) and 2023 (Hardy’s Wives, rituals and romcoms).

October Books: Ballard, Czarnecki, Moss, Oliver, Ostriker, Steed & More

Apparently October is THE biggest month of the year for new releases. A sterling set came my way this year, including two beautiful novella-length memoirs, a luxuriantly illustrated work dedicated to an everyday bird species, two very different but equally elegant poetry collections, and a book of offbeat comics. Time and concentration only allow for a paragraph or so on each, but I hope that gives a flavour of the contents and will pique interest in the ones that suit you best. Plus I excerpt and link to my BookBrowse review of a poignant story of sisters and mental illness, and my Shelf Awareness review of a fantastic graphic novel adaptation.

Bound: A Memoir of Making and Remaking by Maddie Ballard

This collection of micro-essays considers sewing and much more. Each piece is headed by a pattern name and list of materials that Ballard made into an article of clothing for herself or for someone else. Among the minutiae of the craft, she slips in so many threads: about her mixed Chinese heritage and her relationship with her grandmother, about the environmental and financial benefits of making one’s own clothing, and especially about the upheaval of her twenties: the pandemic, a break-up, leaving a job to go back to school, finding roommates. I can barely mend a sock and I’m clueless when it comes to fashion, yet I can appreciate how sewing blends comfort and creativity. Ballard presents it as a meditative act of self-care:

This collection of micro-essays considers sewing and much more. Each piece is headed by a pattern name and list of materials that Ballard made into an article of clothing for herself or for someone else. Among the minutiae of the craft, she slips in so many threads: about her mixed Chinese heritage and her relationship with her grandmother, about the environmental and financial benefits of making one’s own clothing, and especially about the upheaval of her twenties: the pandemic, a break-up, leaving a job to go back to school, finding roommates. I can barely mend a sock and I’m clueless when it comes to fashion, yet I can appreciate how sewing blends comfort and creativity. Ballard presents it as a meditative act of self-care:

I lower the needle and the world recedes. The process of sewing a garment – printing the pattern, tracing and cutting, sewing the first and the second and the fiftieth seam – is a lesson in taking your time.

Like gardening, sewing is an investment in the future – in what sort of person your future self will be, and how she will feel about her body, and what she will want to wear.

Similar to two other very short works of nonfiction I’ve read from The Emma Press, How Kyoto Breaks Your Heart by Florentyna Leow and Tiny Moons by Nina Mingya Powles (Ballard, too, is from New Zealand), this is a graceful, enriching book about a young woman making her way in the world and figuring out what is essential to her sense of home and identity. I commend it whether or not you have any particular interest in handicraft.

With thanks to The Emma Press for the free copy for review.

Encounters with Inscriptions: A Memoir Exploring Books Gifted by Parents by Kristin Czarnecki

When Kristin Czarnecki got in touch to offer a copy of her bibliomemoir about revisiting the books her late parents gifted her, I was instantly intrigued but couldn’t have known in advance how perfect it would be for me. Niche it might seem, but it combines several of my reading interests: bereavement, books about books, relationships with parents (especially a mother) and literary travels.

The book starts, aptly, with childhood. A volume of Shel Silverstein poetry and A Child’s Christmas in Wales serve as perfect vehicles for the memories of how her parents passed on their love of literature and created family holiday rituals. Thereafter, the chapters are not strictly chronological but thematic. A work of women’s history opens up her mother’s involvement in the feminist movement; reading a Thomas Merton book reveals why his thinking was so important to her Catholic father. The interplay of literary criticism, cultural commentary and personal significance is especially effective in pieces on Alice Munro and Flannery O’Connor. A Virginia Woolf biography points to Czarnecki’s academic specialism and a cookbook to how food embodies memories.

The book starts, aptly, with childhood. A volume of Shel Silverstein poetry and A Child’s Christmas in Wales serve as perfect vehicles for the memories of how her parents passed on their love of literature and created family holiday rituals. Thereafter, the chapters are not strictly chronological but thematic. A work of women’s history opens up her mother’s involvement in the feminist movement; reading a Thomas Merton book reveals why his thinking was so important to her Catholic father. The interplay of literary criticism, cultural commentary and personal significance is especially effective in pieces on Alice Munro and Flannery O’Connor. A Virginia Woolf biography points to Czarnecki’s academic specialism and a cookbook to how food embodies memories.

It seems fitting to be reviewing this on the second anniversary of my mother’s death. The afterword, which follows on from the philosophical encouragement of a chapter on the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, exhorts readers to cherish loved ones while we can – and be grateful for the tokens they leave behind. I had told Kristin about books my parents inscribed to me, as well as the journals I inherited from my mother. But I didn’t know there would be other specific connections between us, too, such as being childfree and hopeless in the kitchen. (Also, I have family in South Bend, Indiana, where she’s from, and our mothers were born in the first week of August.) All that to say, I felt that I found a kindred spirit in this lovely book, which is one of the nicest things that happens through reading.

With thanks to the author for the advanced e-copy for review.

The Starling: A Biography by Stephen Moss

Moss has written a whole series of accessible bird species monographs suitable for nature buffs; this is the sixth. (I’ve not read the others, just Moss’s Wild Hares and Hummingbirds and Skylarks with Rosie, but we do have a copy of The Robin on the shelf that I’ve earmarked for Christmas.) The choice of the term ‘biography’ indicates the meeting of a comprehensive aim and intimate detail. The book conveys much anatomical and historical information about the starling’s relatives, habits, and worldwide spread, yet is only 187 pages – and plenty of those feature relevant paintings and photographs, too. It’s well known that starlings were introduced to Anglophone countries as part of misguided “acclimatisation” projects that we would now dub cultural imperialism. In the USA and elsewhere, the bird is still considered common. But with the industrialisation of agriculture, starlings are actually having less breeding success and thus are in decline.

Moss has written a whole series of accessible bird species monographs suitable for nature buffs; this is the sixth. (I’ve not read the others, just Moss’s Wild Hares and Hummingbirds and Skylarks with Rosie, but we do have a copy of The Robin on the shelf that I’ve earmarked for Christmas.) The choice of the term ‘biography’ indicates the meeting of a comprehensive aim and intimate detail. The book conveys much anatomical and historical information about the starling’s relatives, habits, and worldwide spread, yet is only 187 pages – and plenty of those feature relevant paintings and photographs, too. It’s well known that starlings were introduced to Anglophone countries as part of misguided “acclimatisation” projects that we would now dub cultural imperialism. In the USA and elsewhere, the bird is still considered common. But with the industrialisation of agriculture, starlings are actually having less breeding success and thus are in decline.

Overall, the style of the book is dry and slightly workmanlike. However, when he’s recounting murmurations he’s seen in Somerset or read about, Moss’s enthusiasm lifts it into something special. Autumn dusk is a great time to start watching out for starling gatherings. I love observing and listening to the starlings just in the treetops and aerials of my neighbourhood, but we do also have a small local murmuration that I try to catch at least a few times in the season. Here’s how he describes their magic: “At a time when, both as a society and as individuals, we are less and less in touch with the natural world, attending this fleeting but memorable event is a way we can reconnect, regain our primal sense of wonder – and still be home in time for tea.”

With thanks to Square Peg, an imprint of Vintage (Penguin Random House) for the free copy for review.

The Alcestis Machine by Carolyn Oliver

Carolyn is a blogger friend whose first collection, Inside the Storm I Want to Touch the Tremble, was on my Best Books of 2022 list. Her second is again characterized by precise vocabulary and crystalline imagery, often related to etymology, book history, or pigments (“You and I are marginalia shadowed / by a careless hand, we are gall-soaked vellum / invisible appetites consume.”). Astronomy and technology are a counterpoint, juxtaposing the ancient and the cutting-edge. I loved the language of sea creatures in “Strange Attractor” and the oblique approach to the passage of time (“Three popes ago, you and I”). The repeated three-word opening “In another life” gives a sense of many worlds, e.g., “In another life I’m a florist sometimes accused of inappropriate gravity.” Prose poems relay childhood memories. Love poems are tantalizing and utterly original: “If I promise not to describe the moon, will you / come with me a ways further into the night? / We’ll wash the forest floor / of ash and find a fairy ring / half-eaten, muted crescent bereft of power.” And alliteration never fails to win me over: “Tonight, snow tumbles over sophomores and starlings” and “the pillars in the water make a pillory not a pier”. Some of the collection remained cryptic for me; there was a bit less that grabbed me emotionally. But it’s still stirring work. And how flabbergasted was I to spot my name in the Acknowledgments? (Read via Edelweiss)

Carolyn is a blogger friend whose first collection, Inside the Storm I Want to Touch the Tremble, was on my Best Books of 2022 list. Her second is again characterized by precise vocabulary and crystalline imagery, often related to etymology, book history, or pigments (“You and I are marginalia shadowed / by a careless hand, we are gall-soaked vellum / invisible appetites consume.”). Astronomy and technology are a counterpoint, juxtaposing the ancient and the cutting-edge. I loved the language of sea creatures in “Strange Attractor” and the oblique approach to the passage of time (“Three popes ago, you and I”). The repeated three-word opening “In another life” gives a sense of many worlds, e.g., “In another life I’m a florist sometimes accused of inappropriate gravity.” Prose poems relay childhood memories. Love poems are tantalizing and utterly original: “If I promise not to describe the moon, will you / come with me a ways further into the night? / We’ll wash the forest floor / of ash and find a fairy ring / half-eaten, muted crescent bereft of power.” And alliteration never fails to win me over: “Tonight, snow tumbles over sophomores and starlings” and “the pillars in the water make a pillory not a pier”. Some of the collection remained cryptic for me; there was a bit less that grabbed me emotionally. But it’s still stirring work. And how flabbergasted was I to spot my name in the Acknowledgments? (Read via Edelweiss)

The Holy & Broken Bliss: Poems in Plague Time by Alicia Ostriker

“The words of an old woman shuffling the cards of her own decline the decline

of her husband the decline of her nation her plague-smitten world”

Out of pandemic isolation come new rituals: watching days and seasons pass, fighting for her own health but mostly her husband’s, and lamenting public displays of hate. Lines feel stark with honesty; some poems are just haiku length. Elsewhere, repetition and alliteration create a wistful tone. Jewish scripture and mysticism are the source of much of the language and outlook. Music and nature, too, promise the transcendent. Simple and remarkable. Here’s a stanza about late autumn:

Out of pandemic isolation come new rituals: watching days and seasons pass, fighting for her own health but mostly her husband’s, and lamenting public displays of hate. Lines feel stark with honesty; some poems are just haiku length. Elsewhere, repetition and alliteration create a wistful tone. Jewish scripture and mysticism are the source of much of the language and outlook. Music and nature, too, promise the transcendent. Simple and remarkable. Here’s a stanza about late autumn:

It is almost winter and still

as I walk to the clinic the gingkos

sing their seraphic air

as if there is no tomorrow

With thanks to Alice James Books for the advanced e-copy for review.

Forces of Nature by Edward Steed

Steed is a longtime New Yorker cartoonist who produces single panels. This means there is no story progression (as in a graphic novel), just what you see on one page. Some of the comics are wordless; many scenes are visual gags which, to be entirely honest, I didn’t always grasp. Steed’s recurring characters are unhappy couples, exiles on desert islands, and dumb cops or criminals. His style is deliberately simplistic: the people not much more advanced than stick figures and the animals especially sketchy. There are multiple attempted prison breaks and satirical depictions of God and the Garden of Eden. Many of the setups are contrived, and the tone can be absurd or prickly, even shading into gruesome. These comics weren’t altogether my cup of tea, though I did get a laugh out of a few of them (a seasonal example is below). Endorsed if you fancy a cross between Edward Gorey and The Book of Bunny Suicides.

Steed is a longtime New Yorker cartoonist who produces single panels. This means there is no story progression (as in a graphic novel), just what you see on one page. Some of the comics are wordless; many scenes are visual gags which, to be entirely honest, I didn’t always grasp. Steed’s recurring characters are unhappy couples, exiles on desert islands, and dumb cops or criminals. His style is deliberately simplistic: the people not much more advanced than stick figures and the animals especially sketchy. There are multiple attempted prison breaks and satirical depictions of God and the Garden of Eden. Many of the setups are contrived, and the tone can be absurd or prickly, even shading into gruesome. These comics weren’t altogether my cup of tea, though I did get a laugh out of a few of them (a seasonal example is below). Endorsed if you fancy a cross between Edward Gorey and The Book of Bunny Suicides.

With thanks to Drawn & Quarterly for the e-copy for review.

Reviewed for BookBrowse:

Shred Sisters by Betsy Lerner – “No one will love you more or hurt you more than a sister” is a wry aphorism that appears late in Lerner’s debut novel. Over the course of two decades, there is much heartache for the Shred family, but also moments of joy. Ultimately, a sisterly bond endures despite secrets, betrayals, and intermittent estrangement. Through her psychologically astute portrait of Olivia (“Ollie”) and Amy Shred, Lerner captures the lasting effects that mental illness can have on not just an individual, but an entire family.

Shred Sisters by Betsy Lerner – “No one will love you more or hurt you more than a sister” is a wry aphorism that appears late in Lerner’s debut novel. Over the course of two decades, there is much heartache for the Shred family, but also moments of joy. Ultimately, a sisterly bond endures despite secrets, betrayals, and intermittent estrangement. Through her psychologically astute portrait of Olivia (“Ollie”) and Amy Shred, Lerner captures the lasting effects that mental illness can have on not just an individual, but an entire family.

Reviewed for Shelf Awareness:

The Worst Journey in the World, Volume 1: Making Our Easting Down: The Graphic Novel by Sarah Airriess – The thrilling opening to a cinematically vivid adaptation of Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s 1922 memoir. He was an assistant zoologist on Robert Falcon Scott’s 1910-13 Terra Nova expedition to the South Pole. Even before the ship entered the pack ice, the journey was perilous. The book resembles a full-color storyboard for a Disney-style maritime adventure film. There is jolly camaraderie as the men sing sea shanties to boost morale. The second volume can’t arrive soon enough.

The Worst Journey in the World, Volume 1: Making Our Easting Down: The Graphic Novel by Sarah Airriess – The thrilling opening to a cinematically vivid adaptation of Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s 1922 memoir. He was an assistant zoologist on Robert Falcon Scott’s 1910-13 Terra Nova expedition to the South Pole. Even before the ship entered the pack ice, the journey was perilous. The book resembles a full-color storyboard for a Disney-style maritime adventure film. There is jolly camaraderie as the men sing sea shanties to boost morale. The second volume can’t arrive soon enough.

Three on a Theme: English Gardeners (Bradbury, Laing and Mabey)

These three 2024 releases share a passion for gardening – but not the old-fashioned model of bending nature to one’s will to create aesthetically pleasing landscapes. Instead, the authors are also concerned with sustainability and want to do the right thing in a time of climate crisis (all three mention the 2022 drought, which saw the first 40 °C day being recorded in the UK). They seek to strike a balance between human interference and letting a site go wild, and they are cognizant of the wider political implications of having a plot of land of one’s own. All three were borrowed from the public library. #LoveYourLibrary

One Garden against the World: In Search of Hope in a Changing Climate by Kate Bradbury

Bradbury is Wildlife Editor of BBC Gardeners’ World Magazine and makes television appearances in the UK. She’s owned her suburban Brighton home for four years and has tried to turn its front and back gardens into havens, however small, for wildlife. The book covers April 2022 to June 2023, spotlighting the drought summer. “It’s about a little garden in south Portslade and one terrified, angry gardener.” Month by month, present-tense chapters form not quite a diary, but a record of what she’s planting, pruning, relocating, and so on. There is also a species profile at the end of each chapter, usually of an insect (as in the latest Dave Goulson book) – she’s especially concerned that she’s seeing fewer, yet she’s worried for local birds, trees and hedgehogs, too.

Often, she takes matters into her own hands. She plucks caterpillars from vegetation in the path of strimmers in the park and raises them at home; protects her garden’s robins from predators and provides enough food so they can nest and raise five fledglings; undertakes to figure out where her pond’s amphibians have come from; rescues hedgehogs; and bravely writes to neighbours who have scaffolding up (for roof repairs, etc.) beseeching them to put up swift boxes while they’re at it. Sometimes it works: a pub being refurbished by new owners happily puts up sparrow boxes when she tells them the birds have always nested in crevices in the building. Sometimes it doesn’t; people ignore her letters and she can’t seem to help but take it personally.

For individuals, it’s all too easy to be overtaken by anxiety, helplessness and despair, and Bradbury acknowledges that collective action and solidarity are vital. “I am reminded, once again, that it’s the community that will save these trees, not me. I’m reminded that community is everything.” She bands together with other environmentally minded people to resist a local development, educate the public about hedgehogs through talks, and oppose “Drone Bastard,” who flies drones at seagulls nesting on rooftops (not strictly illegal; disappointingly, their complaint doesn’t get anywhere with the police, RSPB or RSPCA).

Along the way, there are a few insights into the author’s personal life. She lives with her partner Emma and dog Tosca and accesses wild walks even right on the edge of a city in the Downs. Separate visits to her divorced parents are chances for more nature spotting – in Suffolk to see her father, she hears her first curlew and lapwings – but also involve some sadness, as her mother has aphasia and fatigue after a stroke.

Nearly every day of the chronology seems to bring more bad news for nature. “It’s hard, sometimes,” she admits, “trying to enjoy natural, wonderful events, trying to keep the clawing sense of unease at bay”. She is staunch in her fond stance: “I will love it, with all my heart, whatever has managed to remain, whatever is left.” And she models through her own amazingly biodiverse garden the ways we can extend refuge to other creatures if we throw out that pointless notion of ‘tidiness.’ “The UK’s 30 million gardens represent 30 million opportunities to create green spaces that hold on to water and carbon, create shade, grow food and provide habitats for wildlife that might otherwise not survive.” Reading this made me feel less guilty about the feral tangle of buddleia, ragwort, hemp agrimony and bindweed overtaking the parts of our back garden that aren’t given over to meadow, pond and hedge. Every time I venture back there I see tons of insects and spiders, and that’s all that matters.

My main critique is that one year would have been adequate, cutting the book to 250 pages rather than 300 and ensuring less repetition while still being a representative time period. But Bradbury is impressive for her vigilance and resolve. Some might say that she takes herself and life too seriously, but it’s really more that she’s aware of the scale of destruction already experienced and realistic about what we stand to lose. ![]()

The Garden Against Time: In Search of a Common Paradise by Olivia Laing

I consider Laing one of our most important public thinkers. I saw her introduce the book via the online Edinburgh Book Festival event “In Search of Eden,” in which she appeared on screen and was interviewed by JC Niala. Laing explained that this is not a totally new topic for her as she has been involved in environmental activism and in herbalism. But in 2020, when she and her much older husband bought a house in Suffolk – the first home she has owned after a life of renting – she started restoring its walled garden, which had been created in the 1960s by Mark Rumary. For a year, she watched and waited to see what would happen in the garden, only removing obvious weeds. This coincided with lockdown, so visits to gardens and archives were limited; she focused more on the creation of her own garden and travelling through literature. A two-year diary resulted, in seven notebooks.

Niala observed that the structure of the book, with interludes set in the Suffolk garden, means that the reader has a place to come back to between the deep dives into history. Why make a garden? she asked Laing. Beauty, pleasure, activity: these would be pat answers, Laing insisted. Instead, as with all her books, the reason is the impulse to make complicated structures. Repetitive tasks can be soothing; “the drudgery can be compelling as well.”

Laing spoke of a garden as both refuge and resistance, a mix of wild and cultivated. In this context, Derek Jarman’s Dungeness garden was a “wellspring of inspiration” for her, “a riposte to a toxic atmosphere” of nuclear power and the AIDS crisis (Rumary, like Jarman, was gay). It’s hard to tell where the beach ends and his garden begins, she noted, and she tried to make her garden similarly porous by kicking a hole in the door so frogs could get in. She hopes it will be both vulnerable and robust, a biodiversity hotspot. With Niala, she discussed the idea of a garden as a return to innocence. We have a “tarnished Eden” due to climate change, and we have to do what we can to reverse that.

The event was brilliant – just the level of detail I wanted, with Laing flitting between subjects and issuing amazingly intelligent soundbites. The book, though, seemed like page after page about Milton (Paradise Lost) and Iris Origo or the Italian Renaissance. I liked it best when it stayed personal to her family and garden project. There are incredible lyric passages, but just stringing together floral species’ names – though they’re lovely and almost incantatory – isn’t art; it also shuts out those of us who don’t know plants, who aren’t natural gardeners. I wasn’t about to Google every plant I didn’t know (though I did for a few). Also, I have read a lot about Derek Jarman in particular. So my reaction was admiration rather than full engagement, and I only gave the book a light skim in the end. It is striking, though, how she makes this subject political by drawing in equality of access and the climate crisis. (Shortlisted for the Kirkus Prize and the Wainwright Prize.) ![]()

Some memorable lines:

“A garden is a time capsule, as well as a portal out of time.”

“A garden is a balancing act, which can take the form of collaboration or outright war. This tension between the world as it is and the world as humans desire it to be is at the heart of the climate crisis, and as such the garden can be a place of rehearsal too, of experimenting with this relationship in new and perhaps less harmful ways.”

“the garden had become a counter to chaos on a personal as well as a political level”

“the more sinister legacy of Eden: the fantasy of perpetual abundance”

The Accidental Garden: Gardens, Wilderness and the Space in Between by Richard Mabey

Mabey gives a day-to-day description of a recent year on his two-acre Norfolk property, but also an overview of the past 20 years of change – which of course pretty much always equates to decline. He muses on wildflowers, growing a meadow and hedgerow, bird behaviour, butterfly numbers, and the weather becoming more erratic and extreme. What he sees at home is a reflection of what is going on in the world at large. “It would be glib to suggest that the immeasurably complex problems of a whole world are mirrored in the small confrontations and challenges of the garden. But maybe the mindset needed for both is the same: the generosity to reset the power balance between ourselves and the natural world.” He seeks to create “a fusion garden” of native and immigrant species, trying to intervene as little as possible. The goal is to tend the land responsibly and leave it better off than he found it. As with the Laing, I found many good passages, but overall I felt this was thin – perhaps reflecting his age and loss of mobility – or maybe a swan song. Again, I just skimmed, even though it’s only 160 pages.

Mabey gives a day-to-day description of a recent year on his two-acre Norfolk property, but also an overview of the past 20 years of change – which of course pretty much always equates to decline. He muses on wildflowers, growing a meadow and hedgerow, bird behaviour, butterfly numbers, and the weather becoming more erratic and extreme. What he sees at home is a reflection of what is going on in the world at large. “It would be glib to suggest that the immeasurably complex problems of a whole world are mirrored in the small confrontations and challenges of the garden. But maybe the mindset needed for both is the same: the generosity to reset the power balance between ourselves and the natural world.” He seeks to create “a fusion garden” of native and immigrant species, trying to intervene as little as possible. The goal is to tend the land responsibly and leave it better off than he found it. As with the Laing, I found many good passages, but overall I felt this was thin – perhaps reflecting his age and loss of mobility – or maybe a swan song. Again, I just skimmed, even though it’s only 160 pages. ![]()

Some memorable lines:

“being Earth’s creatures ourselves, we too have a right to a niche. So in our garden we’ve had more modest ambitions, for ‘parallel development’ you might say, and a sense of neighbourliness with our fellow organisms.”

“We feel embattled at times, and that we should try to make some sort of small refuge, a natural oasis.”

“A garden, with its complex interactions between humans and nature, is often seen as a metaphor for the wider world. But if so, is our plot a microcosm of this troubled arena or a refuge from it?”

You might think I would have been more satisfied by Mabey’s contemplative bent, or Laing’s wealth of literary and historical allusions. It turns out that when it comes to gardening, Bradbury’s practical approach was what I was after. But you may gravitate to any of these, depending on whether you want something for the hands, intellect or memory.

These linked speculative stories, set in near-future California, are marked by environmental anxiety. Many of their characters have South Asian backgrounds. A nascent queer romance between co-op grocery colleagues defies an impending tsunami. A painter welcomes a studio visitor who could be her estranged husband traveling from the past. Mysterious “fog catchers” recur in multiple stories. Memory bridges the human and the artificial, as in “The Glitch,” wherein a coder, bereaved by wildfires, lives alongside holograms of her wife and children. But technology, though a potential means of connecting with the dead, is not an unmitigated good. Creative reinterpretations of traditional stories and figures include urban legends, a locked room mystery, a poltergeist, and a golem. In these grief- and regret-tinged stories, heartbroken people can’t alter their pasts, so they’ll mold the future instead. (See my full

These linked speculative stories, set in near-future California, are marked by environmental anxiety. Many of their characters have South Asian backgrounds. A nascent queer romance between co-op grocery colleagues defies an impending tsunami. A painter welcomes a studio visitor who could be her estranged husband traveling from the past. Mysterious “fog catchers” recur in multiple stories. Memory bridges the human and the artificial, as in “The Glitch,” wherein a coder, bereaved by wildfires, lives alongside holograms of her wife and children. But technology, though a potential means of connecting with the dead, is not an unmitigated good. Creative reinterpretations of traditional stories and figures include urban legends, a locked room mystery, a poltergeist, and a golem. In these grief- and regret-tinged stories, heartbroken people can’t alter their pasts, so they’ll mold the future instead. (See my full  In the 25 poems of Goett’s luminous third poetry collection, nature’s beauty and ancient wisdom sustain the fragile and bereaved. The speaker in “Difficult Body” references a cancer experience and imagines escaping the flesh to diffuse into the cosmos. Goett explores liminal moments and ponders what survives a loss. The use of “terminal” in “Free Fall” denotes mortality while also bringing up fond memories of her late father picking her up from an airport. Mythical allusions, religious imagery, and Buddhist philosophy weave through to shine ancient perspective on current struggles. The book luxuriates in abstruse vocabulary and sensual descriptions of snow, trees, and color. (Tupelo Press, 24 December. Review forthcoming at Shelf Awareness)

In the 25 poems of Goett’s luminous third poetry collection, nature’s beauty and ancient wisdom sustain the fragile and bereaved. The speaker in “Difficult Body” references a cancer experience and imagines escaping the flesh to diffuse into the cosmos. Goett explores liminal moments and ponders what survives a loss. The use of “terminal” in “Free Fall” denotes mortality while also bringing up fond memories of her late father picking her up from an airport. Mythical allusions, religious imagery, and Buddhist philosophy weave through to shine ancient perspective on current struggles. The book luxuriates in abstruse vocabulary and sensual descriptions of snow, trees, and color. (Tupelo Press, 24 December. Review forthcoming at Shelf Awareness) Randel’s debut is a poised, tender family memoir capturing her Holocaust survivor grandmother’s recollections of the Holocaust. Golda (“Bubbie”) spoke multiple languages but was functionally illiterate. In her mid-80s, she asked her granddaughter to tell her story. Randel flew to south Florida to conduct interviews. The oral history that emerges is fragmentary and frenetic. The structure of the book makes up for it, though. Interview snippets are interspersed with narrative chapters based on follow-up research. Golda, born in 1930, grew up in Romania. When the Nazis came, her older brothers were conscripted into forced labor; her mother and younger siblings were killed in a concentration camp. At every turn, Golda’s survival (through Auschwitz, Christianstadt, and Bergen-Belsen) was nothing short of miraculous. This concise, touching memoir bears witness to a whole remarkable life as well as the bond between grandmother and granddaughter. (See my full

Randel’s debut is a poised, tender family memoir capturing her Holocaust survivor grandmother’s recollections of the Holocaust. Golda (“Bubbie”) spoke multiple languages but was functionally illiterate. In her mid-80s, she asked her granddaughter to tell her story. Randel flew to south Florida to conduct interviews. The oral history that emerges is fragmentary and frenetic. The structure of the book makes up for it, though. Interview snippets are interspersed with narrative chapters based on follow-up research. Golda, born in 1930, grew up in Romania. When the Nazis came, her older brothers were conscripted into forced labor; her mother and younger siblings were killed in a concentration camp. At every turn, Golda’s survival (through Auschwitz, Christianstadt, and Bergen-Belsen) was nothing short of miraculous. This concise, touching memoir bears witness to a whole remarkable life as well as the bond between grandmother and granddaughter. (See my full  Their interactions with family and strangers alike on two vacations – Cape Cod and the Catskills, five years apart – put interracial couple Keru and Nate’s choices into perspective as they near age 40. Although some might find their situation (childfree, with a “fur baby”) stereotypical, it does reflect that of a growing number of aging millennials. Wang portrays them sympathetically, but there is also a note of gentle satire here. The way that identity politics comes into the novel is not exactly subtle, but it does feel true to life. And it is very clever how the novel examines the matters of race, class, ambition, and parenthood through the lens of vacations. Like a two-act play, the framework is simple and concise, yet revealing about contemporary American society. (See my full

Their interactions with family and strangers alike on two vacations – Cape Cod and the Catskills, five years apart – put interracial couple Keru and Nate’s choices into perspective as they near age 40. Although some might find their situation (childfree, with a “fur baby”) stereotypical, it does reflect that of a growing number of aging millennials. Wang portrays them sympathetically, but there is also a note of gentle satire here. The way that identity politics comes into the novel is not exactly subtle, but it does feel true to life. And it is very clever how the novel examines the matters of race, class, ambition, and parenthood through the lens of vacations. Like a two-act play, the framework is simple and concise, yet revealing about contemporary American society. (See my full  Dorothy Caliban is a California housewife whose unhappy marriage to Fred has been strained by the death of their young son (an allergic reaction during routine surgery) and a later miscarriage. When we read that Dorothy believes the radio has started delivering personalized messages to her, we can’t then be entirely sure if its news report about a dangerous creature escaped from an oceanographic research centre is real or a manifestation of her mental distress. Even when the 6’7” frog-man, Larry, walks into her kitchen and becomes her lover and secret lodger, I had to keep asking myself: is he ever independently seen by another character? Can these actions be definitively attributed to him? So perhaps this is a novella to experience on two levels. Take it at face value and it’s a lighthearted caper of duelling adulterers and revenge, with a pointed message about the exploitation of the Other. Or interpret it as a midlife fantasy of sexual rejuvenation and an attentive partner (“[Larry] said that he enjoyed housework. He was good at it and found it interesting”):

Dorothy Caliban is a California housewife whose unhappy marriage to Fred has been strained by the death of their young son (an allergic reaction during routine surgery) and a later miscarriage. When we read that Dorothy believes the radio has started delivering personalized messages to her, we can’t then be entirely sure if its news report about a dangerous creature escaped from an oceanographic research centre is real or a manifestation of her mental distress. Even when the 6’7” frog-man, Larry, walks into her kitchen and becomes her lover and secret lodger, I had to keep asking myself: is he ever independently seen by another character? Can these actions be definitively attributed to him? So perhaps this is a novella to experience on two levels. Take it at face value and it’s a lighthearted caper of duelling adulterers and revenge, with a pointed message about the exploitation of the Other. Or interpret it as a midlife fantasy of sexual rejuvenation and an attentive partner (“[Larry] said that he enjoyed housework. He was good at it and found it interesting”): I hadn’t heard of the author but picked this up from the Bestseller display in my library. It’s a posthumous collection of writings, starting with a few articles Boas wrote for his local newspaper, the Jersey Evening Post, about his experience of terminal illness. Diagnosed late on with incurable throat cancer, Boas spent his last year smoking and drinking Muscadet. Looking back at the privilege and joys of his life, he knew he couldn’t complain too much about dying at 46. He had worked in charitable relief in wartorn regions, finishing his career as director of Jersey Overseas Aid. The articles are particularly witty. After learning his cancer had metastasized to his lungs, he wrote, “The prognosis is not quite ‘Don’t buy any green bananas’, but it’s pretty close to ‘Don’t start any long books’.” While I admired the perspective and equanimity of the other essays, most of their topics were overly familiar for me (gratitude, meditation, therapy, what (not) to do/say to the dying). His openness to religion and use of psychedelics were a bit more interesting. It’s hard to write anything original about dying, and his determined optimism – to the extent of downplaying the environmental crisis – grated. (Public library) [138 pages]