Three on a Theme: Queer Family-Making

Several 2021 memoirs have given me a deeper understanding of the special challenges involved when queer couples decide they want to have children.

“It’s a fundamentally queer principle to build a family out of the pieces you have”

~Jennifer Berney

“That’s the thing[:] there are no accidental children born to homosexuals – these babies are always planned for, and always wanted.”

~Michael Johnson-Ellis

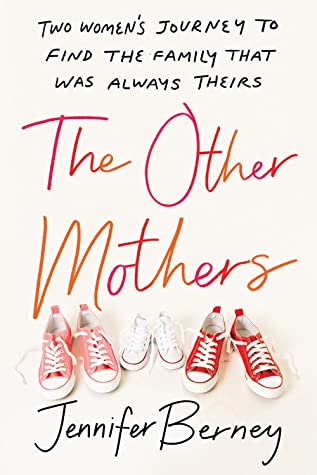

The Other Mothers by Jennifer Berney

Berney remembers hearing the term “test-tube baby” for the first time in a fifth-grade sex ed class taught by a lesbian teacher at her Quaker school. By that time she already had an inkling of her sexuality, so suspected that she might one day require fertility help herself.

By the time she met her partner, Kellie, she knew she wanted to be a mother; Kellie was unsure. Once they were finally on the same page, it wasn’t an easy road to motherhood. They purchased donated sperm through a fertility clinic and tried IUI, but multiple expensive attempts failed. Signs of endometriosis had doctors ready to perform invasive surgery, but in the meantime the couple had met a friend of a friend (Daniel, whose partner was Rebecca) who was prepared to be their donor. Their at-home inseminations resulted in a pregnancy – after two years of trying to conceive – and, ultimately, in their son. Three years later, they did the whole thing all over again. Rebecca had sons at roughly the same time, too, giving their boys the equivalent of same-age cousins – a lovely, unconventional extended family.

By the time she met her partner, Kellie, she knew she wanted to be a mother; Kellie was unsure. Once they were finally on the same page, it wasn’t an easy road to motherhood. They purchased donated sperm through a fertility clinic and tried IUI, but multiple expensive attempts failed. Signs of endometriosis had doctors ready to perform invasive surgery, but in the meantime the couple had met a friend of a friend (Daniel, whose partner was Rebecca) who was prepared to be their donor. Their at-home inseminations resulted in a pregnancy – after two years of trying to conceive – and, ultimately, in their son. Three years later, they did the whole thing all over again. Rebecca had sons at roughly the same time, too, giving their boys the equivalent of same-age cousins – a lovely, unconventional extended family.

It surprised me that the infertility business seemed entirely set up for heterosexual couples – so much so that a doctor diagnosed the problem, completely seriously, in Berney’s chart as “Male Factor Infertility.” This was in Washington state in c. 2008, before the countrywide legalization of gay marriage, so it’s possible the situation would be different now, or that the couple would have had a different experience had they been based somewhere like San Francisco where there is a wide support network and many gay-friendly resources.

Berney finds the joy and absurdity in their journey as well as the many setbacks. I warmed to the book as it went along: early on, it dragged a bit as she surveyed her younger years and traced the history of IVF and alternatives like international adoption. As the storyline drew closer to the present day, there was more detail and tenderness and I was more engaged. I’d read more from this author. (Published by Sourcebooks. Read via NetGalley)

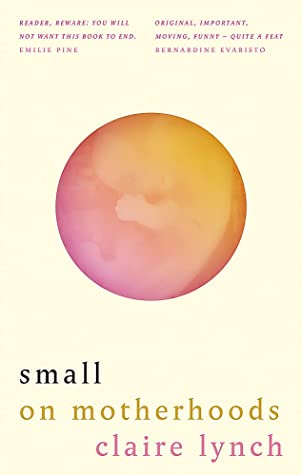

small: on motherhoods by Claire Lynch

A line from Berney’s memoir makes a good transition into this one: “I felt a sense of dread: if I turned out to be gay I believed my life would become unbearably small.” The word “small” is a sort of totem here, a reminder of the microscopic processes and everyday miracles that go into making babies, as well as of the vulnerability of newborns – and of hope.

Lynch and her partner Beth’s experience in England was reminiscent of Berney’s in many ways, but with a key difference: through IVF, Lynch’s eggs were added to donor sperm to make the embryos implanted in Beth’s uterus. Mummy would have the genetic link, Mama the physical tie of carrying and birthing. It took more than three years of infertility treatment before they conceived their twin girls, born premature; they were followed by another daughter, creating a crazy but delightful female quintet. The account of the time when their daughters were in incubators reminded me of Francesca Segal’s Mother Ship.

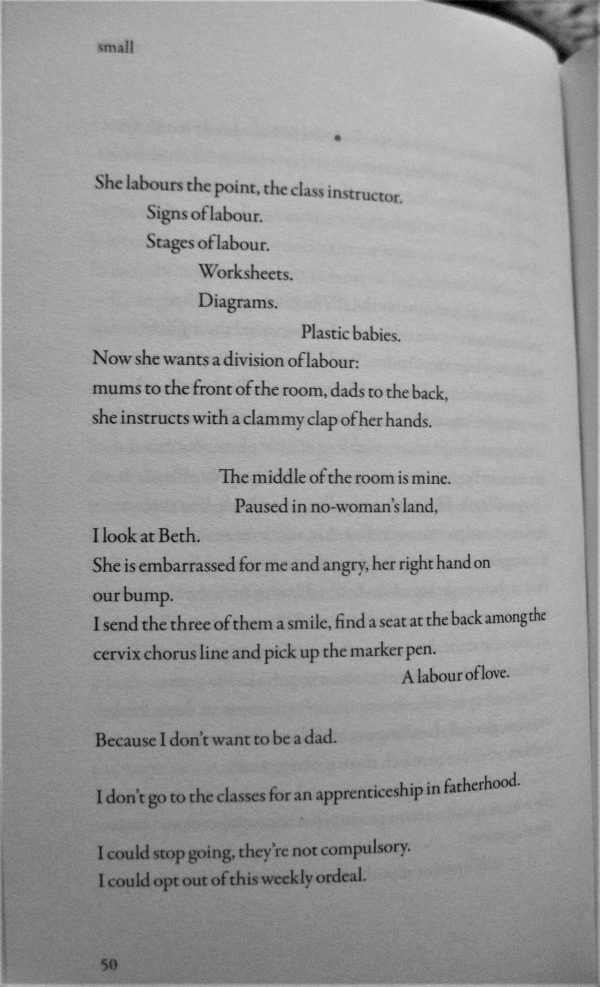

There are two intriguing structural choices that make small stand out. The first you’d notice from opening the book at random, or to page 1. It is written in a hybrid form, the phrases and sentences laid out more like poetry. Although there are some traditional expository paragraphs, more often the words are in stanzas or indented. Here’s an example of what this looks like on the page. It also happens to be from one of the most ironically funny parts of the book, when Lynch is grouped in with the dads at an antenatal class:

It’s a fast-flowing, artful style that may remind readers of Bernardine Evaristo’s work (and indeed, Evaristo gives one of the puffs). The second interesting decision was to make the book turn on a revelation: at the exact halfway mark we learn that, initially, the couple intended to have opposite roles: Lynch tried to get pregnant with Beth’s baby, but miscarried. Making this the pivot point of the memoir emphasizes the struggle and grief of this experience, even though we know that it had a happy ending.

With thanks to Brazen Books for the free copy for review.

How We Do Family by Trystan Reese

We mostly have Trystan Reese to thank for the existence of a pregnant man emoji. A community organizer who works on anti-racist and LGBTQ justice campaigns, Reese is a trans man married to a man named Biff. They expanded their family in two unexpected ways: first by adopting Biff’s niece and nephew when his sister’s situation of poverty and drug abuse meant she couldn’t take care of them, and then by getting pregnant in the natural (is that even the appropriate word?) way.

All along, Reese sought to be transparent about the journey, with a crowdfunding project and podcast ahead of the adoption, and media coverage of the pregnancy. This opened the family up to a lot of online hatred. I found myself most interested in the account of the pregnancy itself, and how it might have healed or exacerbated a sense of bodily trauma. Reese was careful to have only in-the-know and affirming people in the delivery room so there would be no surprises for anyone. His doctor was such an ally that he offered to create a more gender-affirming C-section scar (vertical rather than horizontal) if it came to it. How to maintain a sense of male identity while giving birth? Well, Reese told Biff not to look at his crotch during the delivery, and decided not to breastfeed.

All along, Reese sought to be transparent about the journey, with a crowdfunding project and podcast ahead of the adoption, and media coverage of the pregnancy. This opened the family up to a lot of online hatred. I found myself most interested in the account of the pregnancy itself, and how it might have healed or exacerbated a sense of bodily trauma. Reese was careful to have only in-the-know and affirming people in the delivery room so there would be no surprises for anyone. His doctor was such an ally that he offered to create a more gender-affirming C-section scar (vertical rather than horizontal) if it came to it. How to maintain a sense of male identity while giving birth? Well, Reese told Biff not to look at his crotch during the delivery, and decided not to breastfeed.

I realized when reading this and Detransition, Baby that my view of trans people is mostly post-op because of the only trans person I know personally, but a lot of people choose never to get surgical confirmation of gender (or maybe surgery is more common among trans women?). We’ve got to get past the obsession with genitals. As Reese writes, “we are just loving humans, like every human throughout all of time, who have brought a new life into this world. Nothing more than that, and nothing less. Just humans.”

This is a very fluid, quick read that recreates scenes and conversations with aplomb, and there are self-help sections after most chapters about how to be flexible and have productive dialogue within a family and with strangers. If literary prose and academic-level engagement with the issues are what you’re after, you’d want to head to Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts instead, but I also appreciated Reese’s unpretentious firsthand view.

And here’s further evidence of my own bias: the whole time I was reading, I felt sure that Reese must be the figure on the right with reddish hair, since that looked like a person who could once have been a woman. But when I finished reading I looked up photos; there are many online of Reese during pregnancy. And NOPE, he is the bearded, black-haired one! That’ll teach me to make assumptions. (Published by The Experiment. Read via NetGalley)

Plus a bonus essay from the Music.Football.Fatherhood anthology, DAD:

“A Journey to Gay Fatherhood: Surrogacy – The Unimaginable, Manageable” by Michael Johnson-Ellis

The author and his husband Wes had both previously been married to women before they came out. Wes already had a daughter, so they decided Johnson-Ellis would be the genetic father the first time. They then had different egg donors for their two children, but used the same surrogate for both pregnancies. I was astounded at the costs involved: £32,000 just to bring their daughter into being. And it’s striking both how underground the surrogacy process is (in the UK it’s illegal to advertise for a surrogate) and how exclusionary systems are – the couple had to fight to be in the room when their surrogate gave birth, and had to go to court to be named the legal guardians when their daughter was six weeks old. Since then, they’ve given testimony at the Houses of Parliament and become advocates for UK surrogacy.

The author and his husband Wes had both previously been married to women before they came out. Wes already had a daughter, so they decided Johnson-Ellis would be the genetic father the first time. They then had different egg donors for their two children, but used the same surrogate for both pregnancies. I was astounded at the costs involved: £32,000 just to bring their daughter into being. And it’s striking both how underground the surrogacy process is (in the UK it’s illegal to advertise for a surrogate) and how exclusionary systems are – the couple had to fight to be in the room when their surrogate gave birth, and had to go to court to be named the legal guardians when their daughter was six weeks old. Since then, they’ve given testimony at the Houses of Parliament and become advocates for UK surrogacy.

(I have a high school acquaintance who has gone down this route with his husband – they’re about to meet their daughter and already have a two-year-old son – so I was curious to know more about it, even though their process in the USA might be subtly different.)

On the subject of queer family-making, I have also read: The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson ( ) and The Fixed Stars by Molly Wizenberg (

) and The Fixed Stars by Molly Wizenberg ( ).

).

If you read just one … Claire Lynch’s small was the one I enjoyed most as a literary product, but if you want to learn more about the options and process you might opt for Jennifer Berney’s The Other Mothers; if you’re particularly keen to explore trans issues and LGTBQ activism, head to Trystan Reese’s How We Do Family.

Have you read anything on this topic?

October Reading Plans and Books to Catch Up On

My plans for this month’s reading include:

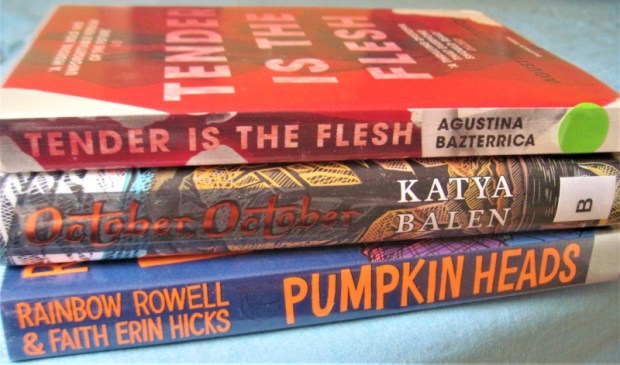

Autumn-appropriate titles & R.I.P. selections, pictured below.

October releases, including some poetry and the debut memoir by local nature writer Nicola Chester – some of us are going on a book club field trip to see her speak about it in Hungerford on Saturday.

October releases, including some poetry and the debut memoir by local nature writer Nicola Chester – some of us are going on a book club field trip to see her speak about it in Hungerford on Saturday.

A review book backlog dating back to July. Something like 18 books, I think? A number of them also fall into the set-aside category, below.

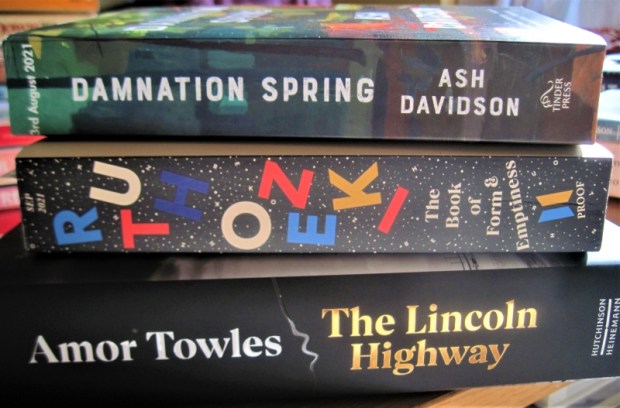

An alarming number of doorstoppers:

- Damnation Spring by Ash Davidson (a buddy read underway with Marcie of Buried in Print; technically it’s 442 pages, but the print is so danged small that I’m calling it a doorstopper even though my usual minimum is 500 pages)

- The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki (in progress for blog review)

- Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead (a library hold on its way to me to try again now that it’s on the Booker Prize shortlist)

- The Lincoln Highway by Amor Towles (in progress for BookBrowse review)

Also, I’m aware that we’re now into the last quarter of the year, and my “set aside temporarily” shelf – which is the literal top shelf of my dining room bookcase, as well as a virtual Goodreads shelf – is groaning with books that I started earlier in the year (or, in some cases, even late last year) and for whatever reason haven’t finished yet.

Setting books aside is a dangerous habit of mine, because new arrivals, such as from the library or from publishers, and more timely-seeming books always edge them out. The only way I have a hope of finishing these before the end of the year is to a) include them in challenges wherever possible (so a few long-languishing books have gone up to join my novella stacks in advance of November) and b) reintroduce a certain number to my current stacks at regular intervals. With just 13 weeks or so remaining, two per week seems like the necessary rate.

Do you have realistic reading goals for the final quarter of the year? (Or no goals at all?)

Library Checkout, September 2021

My library has been closed for a few weeks while a new lighting system is being installed, so I’ve had fewer opportunities to pick out books at random while shelving. Still, I have quite a stockpile at home – a lot of the books are being saved for Novellas in November – so I can’t complain. Meanwhile, I’m awaiting my holds on some of the biggest releases of the year.

This will most likely be our last September in our current rental place as we’ve started house-hunting in the neighbourhood, so I’m trying to appreciate the view from my study window while I can. I’m taking one photo per day to compare. The first hints of autumn leaves are coming through. (Look carefully to the right of the table and you’ll see our cat!)

As always, I give links to reviews of books not already featured, as well as ratings. I would be delighted to have other bloggers – not just book bloggers – join in with this meme. Feel free to use the image below and leave a link to your blog in the comments if you’ve taken part in Library Checkout (on the last Monday of each month), or tag me on Twitter and Instagram: @bookishbeck / #TheLibraryCheckout & #LoveYourLibraries.

READ

- Medusa’s Ankles: Selected Stories by A.S. Byatt

- Tales from Moominvalley by Tove Jansson

- Everyone Is Still Alive by Cathy Rentzenbrink

- September 11: A Testimony (Reuters)

- Pumpkinheads by Rainbow Rowell [graphic novel]

- Lena Finkle’s Magic Barrel by Anya Ulinich [graphic novel]

SKIMMED

- The Easternmost Sky: Adapting to Change in the 21st Century by Juliet Blaxland

- Gardening for Bumblebees: A Practical Guide to Creating a Paradise for Pollinators by Dave Goulson

- An Eye on the Hebrides: An Illustrated Journey by Mairi Hedderwick

- A Walk from the Wild Edge by Jake Tyler

CURRENTLY READING

- Bloodchild and Other Stories by Octavia E. Butler

- Darwin’s Dragons by Lindsay Galvin

- Fathoms: The World in the Whale by Rebecca Giggs

- Anarchipelago by Jay Griffiths

- The Cure for Good Intentions: A Doctor’s Story by Sophie Harrison

- Picnic at Hanging Rock by Joan Lindsay

- Fox and I: An Uncommon Friendship by Catherine Raven

- Cut Out by Michèle Roberts

- Yearbook by Seth Rogen

- A Shadow Above: The Fall and Rise of the Raven by Joe Shute

- The Interestings by Meg Wolitzer

CURRENTLY SKIMMING

- The Sea Is Not Made of Water: Life between the Tides by Adam Nicolson

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

- October, October by Katya Balen

- Winter Story by Jill Barklem

- Tender Is the Flesh by Agustina Bazterrica

- The Tragic Death of Eleanor Marx by Tara Bergin

- Barn Owl by Jim Crumley

- Kingfisher by Jim Crumley

- Otter by Jim Crumley

- Victory: Two Novellas by James Lasdun

- Jilted City by Patrick McGuinness

- His Only Wife by Peace Adzo Medie

- Conundrum by Jan Morris [to reread]

- The State of the Prisons by Sinéad Morrissey

- Fox and I: An Uncommon Friendship by Catherine Raven

- Before Everything by Victoria Redel

- The Performance by Claire Thomas

- Elizabeth and Her German Garden by Elizabeth von Arnim

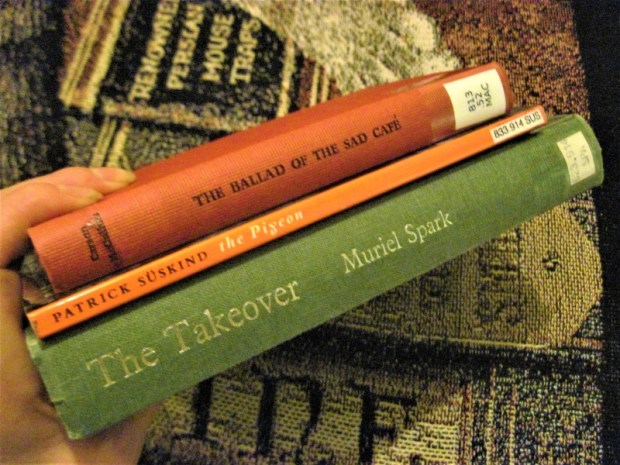

Plus a modest new pile from the university library:

- The Ballad of the Sad Café by Carson McCullers

- The Takeover by Muriel Spark (for 1976 Club)

- The Pigeon by Patrick Süskind

ON HOLD, TO BE PICKED UP

- The Echo Chamber by John Boyne

- The Blind Light by Stuart Evers

- Mayflies by Andrew O’Hagan

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

- Four Thousand Weeks: Time and How to Use It by Oliver Burkeman

- Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doerr

- Manifesto by Bernardine Evaristo

- Spike: The Virus vs. the People – The Inside Story by Jeremy Farrar

- Mrs March by Virginia Feito

- Crossroads by Jonathan Franzen

- Matrix by Lauren Groff

- Julia and the Shark by Kiran Millwood Hargrave

- Standard Deviation by Katherine Heiny

- The Paper Palace by Miranda Cowley Heller

- The Book Smugglers (Pages & Co., #4) by Anna James

- The Morning Star by Karl Ove Knausgaard

- The Premonition: A Pandemic Story by Michael Lewis

- Metamorphosis: Selected Stories by Penelope Lively

- Listen: How to Find the Words for Tender Conversations by Kathryn Mannix

- Sorrow and Bliss by Meg Mason

- Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney

- Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead

- Oh William! By Elizabeth Strout

- Liv’s Alone by Liv Thorne

- Sheets by Brenna Thummler

- The Magician by Colm Tóibín

- Still Life by Sarah Winman (to try again)

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- Something out of Place: Women & Disgust by Eimear McBride – I hadn’t gotten on with her fiction so thought I’d try this short nonfiction work, especially as it was released by the Wellcome Collection and based on research she did at the Wellcome Library. However, it was very dull and just seemed like a string of quotes from other people.

- 12 Bytes: How We Got Here. Where We Might Go Next by Jeanette Winterson – I looked at the first essay to consider reviewing this one, but Winterson’s musings on technology and Mary Shelly feel very familiar – from her previous work as well as others’.

RETURNED UNREAD

- I Give It to You by Valerie Martin – I’ll get this suspenseful Tuscany-set novel out again next summer instead.

- Fall and Rise: The Story of 9/11 by Mitchell Zuckoff – I ran out of time to read this before the twentieth anniversary of 9/11, but I wouldn’t rule out reading it in the future.

What appeals from my stacks?

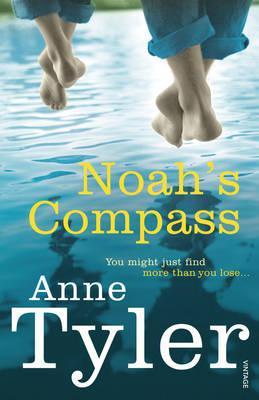

Noah’s Compass by Anne Tyler (2009)

This year I’ve been joining in Liz’s Anne Tyler readalong for most of the novels I own and hadn’t read yet. I’ve discovered a few terrific new-to-me ones: Earthly Possessions, Saint Maybe, The Amateur Marriage … but there have also been some slight duds. Alas, this one falls into the latter category. A Tyler novel is never less than readable, but a habit that I find irksome is on show here, and she’s used this story template more successfully before.

In 2006, Liam Pennywell is forced to start a new life at age 60. After being laid off from his private school teaching job, he downsizes to a smaller apartment further out from central Baltimore. On his first night in the place, he’s assaulted by a would-be burglar and wakes up in hospital with no memory of the lost hours. As he tries to piece together what happened, his three daughters, grandson and ex-wife flit in and out of his life, tutting at his bachelor ways and later disapproving of his budding relationship with a much younger woman.

In 2006, Liam Pennywell is forced to start a new life at age 60. After being laid off from his private school teaching job, he downsizes to a smaller apartment further out from central Baltimore. On his first night in the place, he’s assaulted by a would-be burglar and wakes up in hospital with no memory of the lost hours. As he tries to piece together what happened, his three daughters, grandson and ex-wife flit in and out of his life, tutting at his bachelor ways and later disapproving of his budding relationship with a much younger woman.

The focus on a hapless male trying to do better is a familiar setup for Tyler (Saint Maybe, The Accidental Tourist, A Patchwork Planet, The Beginner’s Goodbye, and Redhead by the Side of the Road, at least – have I missed any?). Liam especially reminded me of Michael in The Amateur Marriage: they feel they have been sleepwalking through life and wish they had appreciated it more and shaped it more through their decisions. As Liam says at one point, “It’s as if I’ve never been entirely present in my own life.” Dating Eunice is his only bid for freedom and happiness. But, in the book’s most memorable scene, a visit to his elderly father is a revelation to Liam: he never wanted to be like this man, but accidentally almost was.

Much as I enjoy sinking into a Tyler novel (the closest I come to a ‘guilty pleasure’ read?), I get exasperated with the way she includes an ostensibly momentous event that doesn’t actually matter much, or only insomuch as it sets up the plot. (Clock Dance is the worst offender in this respect.) There is a suicide in the background, but the assault and memory loss soon fade into the background, to be replaced by well-worn, breezy dysfunctional family happenings. The title, from a Sunday school-based conversation Liam has with his grandson, is cute and meaningful in context – about a drifting life in search of direction – but won’t help as an aide-mémoire for the story. The same goes for the twee cover image on my Vintage paperback.

So, a rather forgettable one – which, unfortunately, has largely been my experience of Tyler’s later work (with the exception of the punchy Shakespearean fun of Vinegar Girl). But you can do much worse than pick up one of her paperbacks on a sunny afternoon.

See also Liz’s review. She’s as lukewarm as I am on this one. (Secondhand purchase from Thatcham Library sale trolley)

My rating:

The 16 Tyler novels I’ve read, in order of preference (greatest to least), are:

Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant

Saint Maybe

The Amateur Marriage

Ladder of Years

The Accidental Tourist

Earthly Possessions

Breathing Lessons

Digging to America

Vinegar Girl

Back When We Were Grown-ups

Clock Dance

A Blue Spool of Thread

The Beginner’s Goodbye

Noah’s Compass

Redhead by the Side of the Road

The Clock Winder

The only unread Tyler I have remaining on my shelves is A Patchwork Planet, which I started in July but didn’t get far with. I’ll try it again another time. And there’s not long to wait now for her NEW novel, French Braid, coming out in March. (Even though I’m sure she announced in 2015 that she was retiring, we’ll have had four novels since then.) The other one that this readalong project has piqued my interest in is Celestial Navigation. I don’t think I’ll bother with her first four novels, which she’d like to see struck from the record. Morgan’s Passing and Searching for Caleb I’m unsure about. Should I find them very cheap secondhand, I’d probably have a go.

The only unread Tyler I have remaining on my shelves is A Patchwork Planet, which I started in July but didn’t get far with. I’ll try it again another time. And there’s not long to wait now for her NEW novel, French Braid, coming out in March. (Even though I’m sure she announced in 2015 that she was retiring, we’ll have had four novels since then.) The other one that this readalong project has piqued my interest in is Celestial Navigation. I don’t think I’ll bother with her first four novels, which she’d like to see struck from the record. Morgan’s Passing and Searching for Caleb I’m unsure about. Should I find them very cheap secondhand, I’d probably have a go.

Summer 2021 Reading, Part II & Transitioning into Autumn

In the past couple of weeks, we’ve taken advantage of the last gasp of summer with some rare chances at socializing, outdoors and in. Our closest friends came to visit us last weekend and accompanied us to a beer festival held in a local field, and this weekend we’ve celebrated birthdays with a formal-wear party at a local arts venue and a low-key family meal.

After my first installment of summer reads, I’ve also finished Klara and the Sun (a bust with me, alas) and the three below: a wildlife photographer’s memoir of lockdown summer spent filming in the New Forest, a record of searching for the summer’s remnants of snow in the Highlands, and an obscure 1950s novel about the psychological connections between four characters in one Irish summer. I close with a summer-into-autumn children’s book.

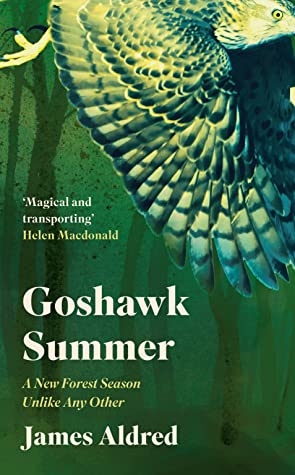

Goshawk Summer: A New Forest Season Unlike Any Other by James Aldred (2021)

My second nature book about the New Forest this year (after The Circling Sky by Neil Ansell) has only sharpened my hankering to get back there and have a good wander after many years away. In March 2020, Aldred had recently returned from filming cheetahs in Kenya when the UK went into its first national lockdown. He had the good fortune to obtain authorization from Forestry England that allowed him to travel regularly from his home in Somerset to the New Forest to gather footage for a documentary for the Smithsonian channel.

Zooming up on empty roads and staying in local cottages so he can start at 4 each morning, he marvels at the peace of a place when humans are taken out of the equation. His diary chronicles a few months of extraordinary wildlife encounters – not only with the goshawks across from whose nest he built a special treetop platform, but also with dragonflies, fox cubs, and rare birds like cuckoo and Dartford warbler. The descriptions of animal behaviour are superb, and the tone is well balanced: alongside the delight of nature watching is anger at human exploitation of the area after the reopening and despair at seemingly intractable declines – of 46 curlew pairs in the Forest, only three chicks survived that summer.

Zooming up on empty roads and staying in local cottages so he can start at 4 each morning, he marvels at the peace of a place when humans are taken out of the equation. His diary chronicles a few months of extraordinary wildlife encounters – not only with the goshawks across from whose nest he built a special treetop platform, but also with dragonflies, fox cubs, and rare birds like cuckoo and Dartford warbler. The descriptions of animal behaviour are superb, and the tone is well balanced: alongside the delight of nature watching is anger at human exploitation of the area after the reopening and despair at seemingly intractable declines – of 46 curlew pairs in the Forest, only three chicks survived that summer.

Despite the woe at nest failures and needless roadkill, Aldred is optimistic – in a similar way to Ansell – that sites like the New Forest can be a model of how light-handed management might allow animals to flourish. “I believe that a little space goes a long way and sometimes all we really need to do is take a step back to let nature do its thing. … It is nature’s ability to help itself, to survive in spite of us in fact, that gives me tentative hope”. (Unsolicited review copy)

With thanks to Elliott & Thompson for the free copy.

Among the Summer Snows by Christopher Nicholson (2017)

After the death from cancer of his wife Kitty, a botanical illustrator, Nicholson set off for Scotland’s Cairngorms and Ben Nevis in search of patches of snow that persist into summer. “Summer snow is a miracle, a piece of out-of-season magic: to see it is one thing, to make physical contact with it is another.” His account of his travels washed over me, leaving little impression. I appreciated the accompanying colour photographs, as the landscape is otherwise somewhat difficult to picture, but even in these it is often hard to get a sense of scale. I think I expected more philosophical reflection in the vein of The Snow Leopard, and, while Nicholson does express anxiety over what happens if one day the summer snows are no more, I found the books on snow by Charlie English and Marcus Sedgwick more varied and profound. (Secondhand, gifted)

After the death from cancer of his wife Kitty, a botanical illustrator, Nicholson set off for Scotland’s Cairngorms and Ben Nevis in search of patches of snow that persist into summer. “Summer snow is a miracle, a piece of out-of-season magic: to see it is one thing, to make physical contact with it is another.” His account of his travels washed over me, leaving little impression. I appreciated the accompanying colour photographs, as the landscape is otherwise somewhat difficult to picture, but even in these it is often hard to get a sense of scale. I think I expected more philosophical reflection in the vein of The Snow Leopard, and, while Nicholson does express anxiety over what happens if one day the summer snows are no more, I found the books on snow by Charlie English and Marcus Sedgwick more varied and profound. (Secondhand, gifted)

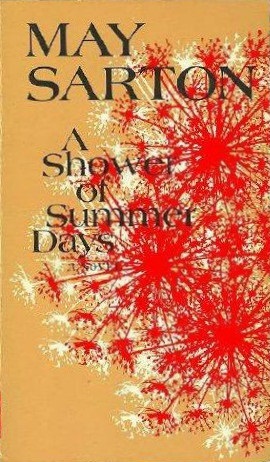

A Shower of Summer Days by May Sarton (1952)

Although I’m more a fan of Sarton’s autobiographical material, especially her journals, I’ve also enjoyed exploring her fiction. This was my seventh of her novels. It’s set in Ireland at Dene’s Court, the grand house Violet inherited. She and her husband Charles have lived in Burma for two decades, but with the Empire on the wane they decide to settle in Violet’s childhood home. Gardening and dressing for dinner fill their languid days until word comes that Violet’s 20-year-old niece, Sally, is coming to stay.

Although I’m more a fan of Sarton’s autobiographical material, especially her journals, I’ve also enjoyed exploring her fiction. This was my seventh of her novels. It’s set in Ireland at Dene’s Court, the grand house Violet inherited. She and her husband Charles have lived in Burma for two decades, but with the Empire on the wane they decide to settle in Violet’s childhood home. Gardening and dressing for dinner fill their languid days until word comes that Violet’s 20-year-old niece, Sally, is coming to stay.

The summer is meant to cure Sally of her infatuation with an actor named Ian. Violet reluctantly goes along with the plan because she feels so badly about the lasting rivalry with her sister, Barbara. Sally is a “bolt of life” shaking up Violet and Charles’s marriage, and when Ian, too, flies out from America, a curious love triangle is refashioned as a quadrilateral. The house remains the one constant as the characters wrestle with their emotional bonds (“the kaleidoscope of feelings was being rather violently shaken up”) and reflect on the transitory splendour of the season (“a kind of timelessness, the warm sun in the enclosed garden in the morning, the hum of bees, and the long slow twilights”). This isn’t one of my favourites from Sarton, but it has low-key charm. I saw it as being on a continuum from Virginia Woolf to Tessa Hadley (e.g. The Past) via Elizabeth Bowen. (Secondhand purchase from Awesomebooks.com)

And finally, one for the seasons’ transition:

Goodbye Summer, Hello Autumn by Kenard Pak (2016)

A child and dog pair set out from home, through the woods, by a river, and into town, greeting other creatures and marking the signs of the season. “Hello!” the beavers reply. “We have no time to play because we’re making cozy nests and dens. It will be cold soon, and we want to get ready.” The quaint Americana setting and papercut-style illustrations reminded me of Vermont college towns and Jon Klassen’s work. I liked the focus on nature. (Free from a neighbour)

A child and dog pair set out from home, through the woods, by a river, and into town, greeting other creatures and marking the signs of the season. “Hello!” the beavers reply. “We have no time to play because we’re making cozy nests and dens. It will be cold soon, and we want to get ready.” The quaint Americana setting and papercut-style illustrations reminded me of Vermont college towns and Jon Klassen’s work. I liked the focus on nature. (Free from a neighbour)

Antrobus, a British-Jamaican poet, won the Rathbones Folio Prize, the Ted Hughes Award, and the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award for his first collection,

Antrobus, a British-Jamaican poet, won the Rathbones Folio Prize, the Ted Hughes Award, and the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award for his first collection,  There’s a prophetic tone behind poems about animal casualties due to pesticides, with “We were warned” used as a refrain in “1 Zephaniah”:

There’s a prophetic tone behind poems about animal casualties due to pesticides, with “We were warned” used as a refrain in “1 Zephaniah”: There is some inconsistency in terms of the amount of context and interpretation given, however. For some poets, there may be just a line or two of text, followed by a reprinted poem (Richard Wilbur, Les Murray); for others, there are paragraphs’ worth of explanations, interspersed with excerpts (Andrew Marvell, Thomas Gray). Some choices are obvious; others are deliberately obscure (e.g., eschewing Robert Frost’s and Philip Larkin’s better-known poems in favour of “Out, Out” and “The Explosion”). The diversity is fairly low, and you can see Carey’s age in some of his introductions: “Edward Lear was gay, and felt a little sad when friends got married”; “Alfred Edward Housman was gay, and he thought it unjust that he should be made to feel guilty about something that was part of his nature.” There’s way too much First and Second World War poetry here. And can a poet really be one of the 100 greatest ever when I’ve never heard of them? (May Wedderburn Cannan, anyone?)

There is some inconsistency in terms of the amount of context and interpretation given, however. For some poets, there may be just a line or two of text, followed by a reprinted poem (Richard Wilbur, Les Murray); for others, there are paragraphs’ worth of explanations, interspersed with excerpts (Andrew Marvell, Thomas Gray). Some choices are obvious; others are deliberately obscure (e.g., eschewing Robert Frost’s and Philip Larkin’s better-known poems in favour of “Out, Out” and “The Explosion”). The diversity is fairly low, and you can see Carey’s age in some of his introductions: “Edward Lear was gay, and felt a little sad when friends got married”; “Alfred Edward Housman was gay, and he thought it unjust that he should be made to feel guilty about something that was part of his nature.” There’s way too much First and Second World War poetry here. And can a poet really be one of the 100 greatest ever when I’ve never heard of them? (May Wedderburn Cannan, anyone?) In her bittersweet second memoir, a religion professor finds the joys and ironies in a life overshadowed by advanced cancer.

In her bittersweet second memoir, a religion professor finds the joys and ironies in a life overshadowed by advanced cancer. This story hit all too close to home to me: like Kat Lister, my sister was widowed in her thirties, her husband having endured gruelling years of treatment for brain cancer that caused seizures and memory loss. Lister’s husband,

This story hit all too close to home to me: like Kat Lister, my sister was widowed in her thirties, her husband having endured gruelling years of treatment for brain cancer that caused seizures and memory loss. Lister’s husband,  My first R.I.P. selection and one I can heartily recommend – even if you’re normally wary of dystopias, horror and science fiction. Butler makes these genres accessible by peopling her plots with relatable protagonists and carefully accounting for their bizarre predicaments without wasting time on extraneous world-building. The way in which she explores very human issues alongside the existence of alien beings reminds me of Mary Doria Russell’s

My first R.I.P. selection and one I can heartily recommend – even if you’re normally wary of dystopias, horror and science fiction. Butler makes these genres accessible by peopling her plots with relatable protagonists and carefully accounting for their bizarre predicaments without wasting time on extraneous world-building. The way in which she explores very human issues alongside the existence of alien beings reminds me of Mary Doria Russell’s

I knew from

I knew from  The musical equivalent of Lot might be a mixtape played on a boombox or blasted from an open-top Corvette while touring the streets of Houston, Texas. Most of this Dylan Thomas Prize-winning linked collection follows Nic, a mixed-race Black/Latino boy who works in the family restaurant. As his family situation realigns – his father leaves, his older brother Javi enlists, his sister Jan has a baby – he’s trying to come to terms with his homosexuality and wondering if this gentrifying city suits him anymore. But he knows he’ll take himself wherever he goes, and as the book closes with “Elgin” (the most similar in mood and setup to Washington’s debut novel,

The musical equivalent of Lot might be a mixtape played on a boombox or blasted from an open-top Corvette while touring the streets of Houston, Texas. Most of this Dylan Thomas Prize-winning linked collection follows Nic, a mixed-race Black/Latino boy who works in the family restaurant. As his family situation realigns – his father leaves, his older brother Javi enlists, his sister Jan has a baby – he’s trying to come to terms with his homosexuality and wondering if this gentrifying city suits him anymore. But he knows he’ll take himself wherever he goes, and as the book closes with “Elgin” (the most similar in mood and setup to Washington’s debut novel,

I only discovered the Moomins in my late twenties, but soon fell in love with the quirky charm of Jansson’s characters and their often melancholy musings. Her stories feel like they can be read on multiple levels, with younger readers delighting in the bizarre creations and older ones sensing the pensiveness behind their quests. There are magical events here: Moomintroll discovers a dragon small enough to be kept in a jar; laughter is enough to bring a fearful child back from literal invisibility. But what struck me more was the lessons learned by neurotic creatures. In “The Fillyjonk who believed in Disasters,” the title character fixates on her belongings—

I only discovered the Moomins in my late twenties, but soon fell in love with the quirky charm of Jansson’s characters and their often melancholy musings. Her stories feel like they can be read on multiple levels, with younger readers delighting in the bizarre creations and older ones sensing the pensiveness behind their quests. There are magical events here: Moomintroll discovers a dragon small enough to be kept in a jar; laughter is enough to bring a fearful child back from literal invisibility. But what struck me more was the lessons learned by neurotic creatures. In “The Fillyjonk who believed in Disasters,” the title character fixates on her belongings— In the opening story, “Potluck,” he meets Charles, a dancer who’s dating Sophie, and the three of them shuffle into a kind of awkward love triangle where, as in Real Life, sex and violence are uncomfortably intertwined. It’s a recurring question in the stories, even those focused around other characters: how does tenderness relate to desire? In the throes of lust, is there room for a gentler love? The troubled teens of the title story are “always in the thick of violence. It moves through them like the Holy Ghost might.” Milton, soon to be sent to boot camp, thinks he’d like to “pry open the world, bone it, remove the ugly hardness of it all.”

In the opening story, “Potluck,” he meets Charles, a dancer who’s dating Sophie, and the three of them shuffle into a kind of awkward love triangle where, as in Real Life, sex and violence are uncomfortably intertwined. It’s a recurring question in the stories, even those focused around other characters: how does tenderness relate to desire? In the throes of lust, is there room for a gentler love? The troubled teens of the title story are “always in the thick of violence. It moves through them like the Holy Ghost might.” Milton, soon to be sent to boot camp, thinks he’d like to “pry open the world, bone it, remove the ugly hardness of it all.” A bonus story: “Oh, Youth” was published in Kink (2021), an anthology edited by Garth Greenwell and R.O. Kwon. I requested this from NetGalley just so I could read the stories by Carmen Maria Machado and Brandon Taylor. All of Taylor’s work feels of a piece, such that his various characters might be rubbing shoulders at a party – which is appropriate because the centrepiece of Real Life is an excruciating dinner party, Filthy Animals opens at a potluck, and “Oh, Youth” is set at a dinner party.

A bonus story: “Oh, Youth” was published in Kink (2021), an anthology edited by Garth Greenwell and R.O. Kwon. I requested this from NetGalley just so I could read the stories by Carmen Maria Machado and Brandon Taylor. All of Taylor’s work feels of a piece, such that his various characters might be rubbing shoulders at a party – which is appropriate because the centrepiece of Real Life is an excruciating dinner party, Filthy Animals opens at a potluck, and “Oh, Youth” is set at a dinner party. After enjoying her debut novel,

After enjoying her debut novel,  I found a number of the stories too similar and thin, and it’s a shame that the hedgehog featured on the cover of the U.S. edition has to embody human carelessness in “Spines,” which is otherwise one of the standouts. But the enthusiasm and liveliness of the language were enough to win me over. (Secondhand purchase from the British Red Cross shop, Hay-on-Wye – how fun, then, to find the line “Did you know Timbuktu is twinned with Hay-on-Wye?”)

I found a number of the stories too similar and thin, and it’s a shame that the hedgehog featured on the cover of the U.S. edition has to embody human carelessness in “Spines,” which is otherwise one of the standouts. But the enthusiasm and liveliness of the language were enough to win me over. (Secondhand purchase from the British Red Cross shop, Hay-on-Wye – how fun, then, to find the line “Did you know Timbuktu is twinned with Hay-on-Wye?”)

A debut trio of raw stories set in the Yorkshire countryside. In “Offcomers,” the 2001 foot and mouth disease outbreak threatens the happiness of a sheep-farming couple. The effects of rural isolation on a relationship resurface in “Outside Are the Dogs.” In “Cull Yaw,” a vegetarian gets involved with a butcher who’s keen on marketing mutton and ends up helping him with a grisly project. This was the stand-out for me. I appreciated the clear-eyed look at where food comes from. At the same time, narrator Star’s mother is ailing: a reminder that decay is inevitable and we are all naught but flesh and blood. I liked the prose well enough, but found the characterization a bit thin. One for readers of Andrew Michael Hurley and Cynan Jones. (See also

A debut trio of raw stories set in the Yorkshire countryside. In “Offcomers,” the 2001 foot and mouth disease outbreak threatens the happiness of a sheep-farming couple. The effects of rural isolation on a relationship resurface in “Outside Are the Dogs.” In “Cull Yaw,” a vegetarian gets involved with a butcher who’s keen on marketing mutton and ends up helping him with a grisly project. This was the stand-out for me. I appreciated the clear-eyed look at where food comes from. At the same time, narrator Star’s mother is ailing: a reminder that decay is inevitable and we are all naught but flesh and blood. I liked the prose well enough, but found the characterization a bit thin. One for readers of Andrew Michael Hurley and Cynan Jones. (See also  Okorie emigrated from Nigeria to Ireland in 2005. Her time living in a direct provision hostel for asylum seekers informed the title story about women queuing for and squabbling over food rations, written in an African pidgin. In “Under the Awning,” a Black woman fictionalizes her experiences of racism into a second-person short story her classmates deem too bleak. The Author’s Note reveals that Okorie based this one on comments she herself got in a writers’ group. “The Egg Broke” returns to Nigeria and its old superstition about twins.

Okorie emigrated from Nigeria to Ireland in 2005. Her time living in a direct provision hostel for asylum seekers informed the title story about women queuing for and squabbling over food rations, written in an African pidgin. In “Under the Awning,” a Black woman fictionalizes her experiences of racism into a second-person short story her classmates deem too bleak. The Author’s Note reveals that Okorie based this one on comments she herself got in a writers’ group. “The Egg Broke” returns to Nigeria and its old superstition about twins. This is the third time Simpson has made it into one of my September features (after

This is the third time Simpson has made it into one of my September features (after