Book Serendipity, Late 2020 into 2021

I call it Book Serendipity when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something pretty bizarre in common. Because I have so many books on the go at once (20+), I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents than some. I also list some of my occasional reading coincidences on Twitter. The following are in chronological order.

- The Orkney Islands were the setting for Close to Where the Heart Gives Out by Malcolm Alexander, which I read last year. They showed up, in one chapter or occasional mentions, in The Frayed Atlantic Edge by David Gange and The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields, plus I read a book of Christmas-themed short stories (some set on Orkney) by George Mackay Brown, the best-known Orkney author. Gavin Francis (author of Intensive Care) also does occasional work as a GP on Orkney.

- The movie Jaws is mentioned in Mr. Wilder and Me by Jonathan Coe and Landfill by Tim Dee.

- The Sámi people of the far north of Norway feature in Fifty Words for Snow by Nancy Campbell and The Mercies by Kiran Millwood Hargrave.

- Twins appear in Mr. Wilder and Me by Jonathan Coe and Tennis Lessons by Susannah Dickey. In Vesper Flights Helen Macdonald mentions that she had a twin who died at birth, as does a character in Miss Benson’s Beetle by Rachel Joyce. A character in The Light Years by Elizabeth Jane Howard is delivered of twins, but one is stillborn. From Wrestling the Angel by Michael King I learned that Janet Frame also had a twin who died in utero.

- Fennel seeds are baked into bread in The Mercies by Kiran Millwood Hargrave and The Strays of Paris by Jane Smiley. Later, “fennel rolls” (but I don’t know if that’s the seed or the vegetable) are served in Monogamy by Sue Miller.

- A mistress can’t attend her lover’s funeral in Here Is the Beehive by Sarah Crossan and Tennis Lessons by Susannah Dickey.

- A sudden storm drowns fishermen in a tale from Christmas Stories by George Mackay Brown and The Mercies by Kiran Millwood Hargrave.

Silver Spring, Maryland (where I lived until age 9) is mentioned in one story from To Be a Man by Nicole Krauss and is also where Peggy Seeger grew up, as recounted in her memoir First Time Ever. Then it got briefly mentioned, as the site of the Institute of Behavioral Research, in Livewired by David Eagleman.

Silver Spring, Maryland (where I lived until age 9) is mentioned in one story from To Be a Man by Nicole Krauss and is also where Peggy Seeger grew up, as recounted in her memoir First Time Ever. Then it got briefly mentioned, as the site of the Institute of Behavioral Research, in Livewired by David Eagleman.

- Lamb is served with beans at a dinner party in Monogamy by Sue Miller and Larry’s Party by Carol Shields.

- Trips to Madagascar in Landfill by Tim Dee and Lightning Flowers by Katherine E. Standefer.

Hospital volunteering in My Year with Eleanor by Noelle Hancock and Leonard and Hungry Paul by Ronan Hession.

Hospital volunteering in My Year with Eleanor by Noelle Hancock and Leonard and Hungry Paul by Ronan Hession.

- A Ronan is the subject of Emily Rapp’s memoir The Still Point of the Turning World and the author of Leonard and Hungry Paul (Hession).

- The Magic Mountain (by Thomas Mann) is discussed in Scattered Limbs by Iain Bamforth, The Still Point of the Turning World by Emily Rapp, and Snow by Marcus Sedgwick.

- Frankenstein is mentioned in The Biographer’s Tale by A.S. Byatt, The Still Point of the Turning World by Emily Rapp, and Snow by Marcus Sedgwick.

- Rheumatic fever and missing school to avoid heart strain in Foreign Correspondence by Geraldine Brooks and Unsettled Ground by Claire Fuller. Janet Frame also had rheumatic fever as a child, as I discovered in her biography.

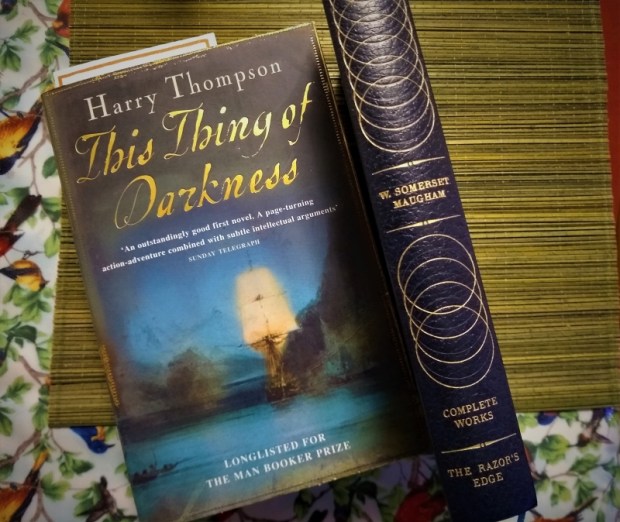

- Reading two novels whose titles come from The Tempest quotes at the same time: Owls Do Cry by Janet Frame and This Thing of Darkness by Harry Thompson.

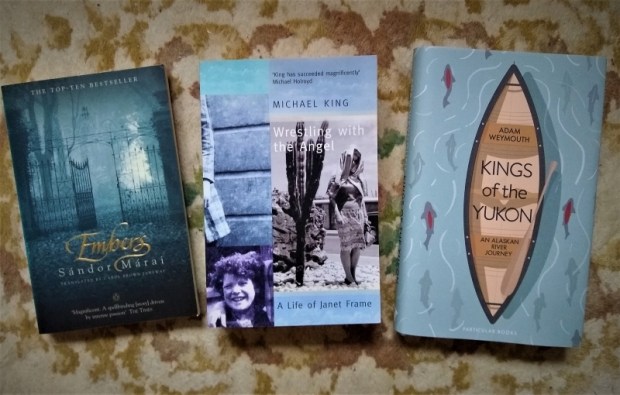

- A character in Embers by Sándor Márai is nicknamed Nini, which was also Janet Frame’s nickname in childhood (per Wrestling the Angel by Michael King).

- A character loses their teeth and has them replaced by dentures in America Is Not the Heart by Elaine Castillo and The Light Years by Elizabeth Jane Howard.

Also, the latest cover trend I’ve noticed: layers of monochrome upturned faces. Several examples from this year and last. Abstract faces in general seem to be a thing.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

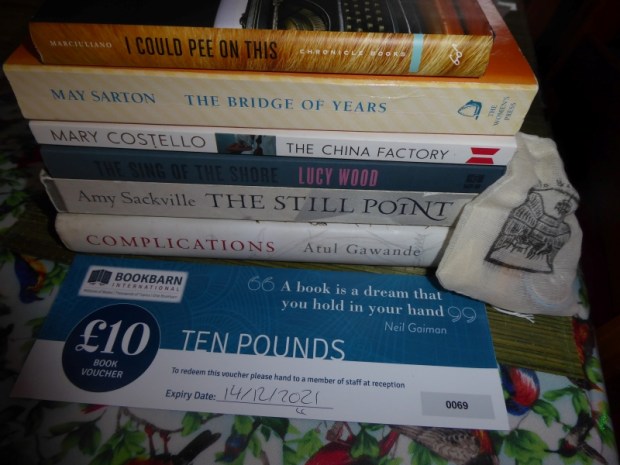

Book Spine Poetry Strikes Again

Great minds think alike in the blogging world: last week, on the very day that Annabel posted a book spine poem, it was on my to-do list to assemble my current reading stack into a poem or two. I’d spotted some evocative and provocative titles, as well as some useful prepositions. The poems below, then, serve as a snapshot of what I’m reading at the moment, with some others from my set aside and occasional reading shelves filling in. You get a glimpse of the variety I read. (For one title in the second pile, a poetry book I’m reading on my e-reader, I had to improvise!)

My previous book spine poetry efforts are here and here (2016); and here (March 2020).

A dark one, imagining an older woman in serious condition and passing a night in a hospital bed:

Intensive Care

Complications,

Pain.

As I Lay Dying,

Owls Do Cry.

I Miss You When I Blink.

This Thing of Darkness,

Spinster Keeper,

Wrestling with the Angel.

And a more general reflection on recent times and what might keep us going:

Embers

How Should a Person Be

In These Days of Prohibition?

The Light Years

Outlawed,

The Noonday Demon.

Some Body to Love

The Still Point,

The Still Point of the Turning World.

Color and Line

A Match to the Heart.

The Bare Abundance

Love’s Work.

Unsettled Ground

The Magician’s Assistant.

Braiding Sweetgrass

Revelations of Divine Love.

Have a go at some book spine poems if you haven’t already! They’re such fun.

Review: Intensive Care by Gavin Francis

I finally finished a book in 2021! And it’s one with undeniable ongoing relevance. The subtitle is “A GP, a Community & COVID-19.” Francis, a physician who is based at an Edinburgh practice and frequently travels to the Orkney Islands for healthcare work, reflects on what he calls “the most intense months I have known in my twenty-year career.” He draws all of his chapter epigraphs from Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year and journeys back through most of 2020, from the day in January when he and his colleagues received a bulletin about a “novel Wuhan coronavirus” to November, when he was finalizing the book and learned of promising vaccine trials but also a rumored third wave and winter lockdown.

In February, no one knew whether precautions would end up being an overreaction, so Francis continued normal life: attending a conference, traveling to New York City, and going to a concert, pub, and restaurant. By March he was seeing more and more suspected cases, but symptoms were variable and the criteria for getting tested and quarantining changed all the time. The UK at least seemed better off than Italy, where his in-laws were isolating. Initially it was like flu outbreaks he’d dealt with before, with the main differences being a shift to telephone consultations and the “Great Faff” of donning full PPE for home visits and trips to care homes. The new “digital first” model left him feeling detached from his patients. He had his own Covid scare in May, but a test was negative and the 48-hour bug passed.

Through his involvement in the community, Francis saw the many ways in which coronavirus was affecting different groups of people. He laments the return of mental health crises that had been under control until lockdown. Edinburgh’s homeless, many in a perilous immigration situation thanks to Brexit, were housed in vacant luxury hotels. He visited several makeshift hostels, where some residents were going through drug withdrawal, and also met longtime patients whose self-harm and suicidal ideation were worsening.

Through his involvement in the community, Francis saw the many ways in which coronavirus was affecting different groups of people. He laments the return of mental health crises that had been under control until lockdown. Edinburgh’s homeless, many in a perilous immigration situation thanks to Brexit, were housed in vacant luxury hotels. He visited several makeshift hostels, where some residents were going through drug withdrawal, and also met longtime patients whose self-harm and suicidal ideation were worsening.

Children and the elderly were also suffering. In June, he co-authored a letter begging the Scottish education secretary to allow children to return to school. Perhaps the image that will stick with me most, though, is of the confused dementia patients he met at care homes: “there was a crushing atmosphere of sadness among the residents … [they were] not able to understand why their families no longer came to visit. How do you explain social distancing to someone who doesn’t remember where they are, sometimes even who they are?”

Francis incorporates brief histories of vaccination and the discovery of herd immunity, and visits a hospital where a vaccine trial is underway. I learned some things about COVID-19 specifically: it can be called a “viral pneumonia”; it has two phases, virological (the virus makes you unwell) and immunological (the immune system misdirects messages and the lungs get worse); and it affects the blood vessels as well as the lungs, with one in five presenting with a rash and some developing chilblains in the summer. Amazingly, as the year waned, Francis only knew three patients who had died of Covid, with many more recovered. But in August, a city that should have been bustling with festival tourists was nearly empty.

Necessarily, the book ends in the middle of things; Francis has clear eyes but a hopeful heart. While this is not the first COVID-19 book I’ve encountered (that was Duty of Care by Dominic Pimenta) and will be far from the last – next up for me will be Rachel Clarke’s Breathtaking, out at the end of this month – it is an absorbing first-hand account of a medical crisis as well as a valuable memorial of a time like no other in recent history. A favorite line was “One of the few consolations of this pandemic is its grim camaraderie, a new fellowship among the fear.” Another consolation for me is reading books by medical professionals who can compassionately bridge the gap between expert opinion and everyday experience.

Intensive Care was published by the Wellcome Collection/Profile Books on January 7th. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

Gavin Francis’s other work includes:

Previously reviewed: Shapeshifters

Also owned: Adventures in Human Being

I’m keen to read: Empire Antarctica, about being the medical officer at the British research centre in Antarctica – ironically, this was during the first SARS pandemic. (In July 2020, conducting medical examinations on the next batch of scientists to ship out there, he envied them the chance to escape: “By the time they came home it would be 2022. Surely we’d have the virus under control by then?”)

Six Degrees of Separation: From Hamnet to Paula

I was slow off the mark this month, but here we go with everyone’s favorite book blogging meme! This time we start with Hamnet, Maggie O’Farrell’s Women’s Prize-winning novel about the death of William Shakespeare’s son. (See Kate’s opening post.) Although I didn’t love this as much as others have (my review is here), I was delighted for O’Farrell to get the well-deserved attention – Hamnet was also named the Waterstones Book of the Year 2020.

I was slow off the mark this month, but here we go with everyone’s favorite book blogging meme! This time we start with Hamnet, Maggie O’Farrell’s Women’s Prize-winning novel about the death of William Shakespeare’s son. (See Kate’s opening post.) Although I didn’t love this as much as others have (my review is here), I was delighted for O’Farrell to get the well-deserved attention – Hamnet was also named the Waterstones Book of the Year 2020.

#1 I’ve read many nonfiction accounts of bereavement. One that stands out is Notes from the Everlost by Kate Inglis, which is also about the death of a child. The author’s twin sons were born premature; one survived while the other died. Her book is about what happened next, and how bereaved parents help each other to cope. An excerpt from my TLS review is here.

#1 I’ve read many nonfiction accounts of bereavement. One that stands out is Notes from the Everlost by Kate Inglis, which is also about the death of a child. The author’s twin sons were born premature; one survived while the other died. Her book is about what happened next, and how bereaved parents help each other to cope. An excerpt from my TLS review is here.

#2 Also featuring a magpie on the cover, at least in its original hardback form, is Wakenhyrst by Michelle Paver (reviewed for R.I.P. this past October). I loved that Maud has a pet magpie named Chatterpie, and the fen setting was appealing, but I’ve been pretty underwhelmed by all three of Paver’s historical suspense novels for adults.

#2 Also featuring a magpie on the cover, at least in its original hardback form, is Wakenhyrst by Michelle Paver (reviewed for R.I.P. this past October). I loved that Maud has a pet magpie named Chatterpie, and the fen setting was appealing, but I’ve been pretty underwhelmed by all three of Paver’s historical suspense novels for adults.

#3 One of the strands in Wakenhyrst is Maud’s father’s research into a painting of the Judgment Day discovered at the local church. In A Month in the Country by J. L. Carr (reviewed last summer), a WWI veteran is commissioned to uncover a wall painting of the Judgment Day, assumed to be the work of a medieval monk and long ago whitewashed over.

#3 One of the strands in Wakenhyrst is Maud’s father’s research into a painting of the Judgment Day discovered at the local church. In A Month in the Country by J. L. Carr (reviewed last summer), a WWI veteran is commissioned to uncover a wall painting of the Judgment Day, assumed to be the work of a medieval monk and long ago whitewashed over.

#4 A Month in the Country spans one summer month. Invincible Summer by Alice Adams, about four Bristol University friends who navigate the highs and lows of life in the 20 years following their graduation, checks in on the characters nearly every summer. I found it clichéd; not one of the better group-of-friends novels. (My review for The Bookbag is here.)

#4 A Month in the Country spans one summer month. Invincible Summer by Alice Adams, about four Bristol University friends who navigate the highs and lows of life in the 20 years following their graduation, checks in on the characters nearly every summer. I found it clichéd; not one of the better group-of-friends novels. (My review for The Bookbag is here.)

#5 The title of Invincible Summer comes from an Albert Camus quote: “In the midst of winter, I found there was, within me, an invincible summer. And that makes me happy.” Inspired by the same quotation, then, is In the Midst of Winter by Isabel Allende, a recent novel of hers that I was drawn to for the seasonal link but couldn’t get through.

#5 The title of Invincible Summer comes from an Albert Camus quote: “In the midst of winter, I found there was, within me, an invincible summer. And that makes me happy.” Inspired by the same quotation, then, is In the Midst of Winter by Isabel Allende, a recent novel of hers that I was drawn to for the seasonal link but couldn’t get through.

#6 However, I’ve enjoyed a number of Allende books over the last 12 years or so, both fiction and non-. One of these was Paula, a memoir sparked by her twentysomething daughter’s untimely death in the early 1990s from complications due to the genetic condition porphyria. Allende told her life story in the form of a letter composed at Paula’s bedside while she was in a coma.

#6 However, I’ve enjoyed a number of Allende books over the last 12 years or so, both fiction and non-. One of these was Paula, a memoir sparked by her twentysomething daughter’s untimely death in the early 1990s from complications due to the genetic condition porphyria. Allende told her life story in the form of a letter composed at Paula’s bedside while she was in a coma.

So, I’ve come full circle with another story of the death of a child, but there’s a welcome glimpse of the summer somewhere there in the middle. May you find your own inner summer to get you through this lockdown winter.

Join us for #6Degrees of Separation! (Hosted on the first Saturday of each month by Kate W. of Books Are My Favourite and Best.) Next month’s starting point is Redhead at the Side of the Road by Anne Tyler.

Happy Feast of the Inauguration!

Happy Feast of the Inauguration! Exceptions: Tim Dee’s books are good examples since he weaves in copious quotations and allusions while still being eloquent in his own right. Emily Rapp’s The Still Point of the Turning World includes a lot of quotes, especially from poems, but I was okay with that because it was true to her experience of traditional thinking failing her in the face of her son’s impending death. Her two bereavement memoirs are thus almost like commonplace books on grief.

Exceptions: Tim Dee’s books are good examples since he weaves in copious quotations and allusions while still being eloquent in his own right. Emily Rapp’s The Still Point of the Turning World includes a lot of quotes, especially from poems, but I was okay with that because it was true to her experience of traditional thinking failing her in the face of her son’s impending death. Her two bereavement memoirs are thus almost like commonplace books on grief. I’ve been reading up a storm in 2021, of course, but I’m having an unusual problem: I can’t seem to finish anything. Okay, I’ve finished three books so far –

I’ve been reading up a storm in 2021, of course, but I’m having an unusual problem: I can’t seem to finish anything. Okay, I’ve finished three books so far –  Spinster by Kate Bolick: Written as she was approaching 40, this is a cross between a memoir, a social history of unmarried women (mostly in the USA), and a group biography of five real-life heroines who convinced her it was alright to not want marriage and motherhood. First was Maeve Brennan; now I’m reading about Neith Boyce. The writing is top-notch.

Spinster by Kate Bolick: Written as she was approaching 40, this is a cross between a memoir, a social history of unmarried women (mostly in the USA), and a group biography of five real-life heroines who convinced her it was alright to not want marriage and motherhood. First was Maeve Brennan; now I’m reading about Neith Boyce. The writing is top-notch. America Is Not the Heart by Elaine Castillo: Set in the 1990s in the Philippines and in the Filipino immigrant neighborhoods of California, this novel throws you into an unfamiliar culture and history right at the deep end. The characters shine and the story is complex and confident – I’m reminded especially of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s work.

America Is Not the Heart by Elaine Castillo: Set in the 1990s in the Philippines and in the Filipino immigrant neighborhoods of California, this novel throws you into an unfamiliar culture and history right at the deep end. The characters shine and the story is complex and confident – I’m reminded especially of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s work. Some Body to Love by Alexandra Heminsley: Finally pregnant after a grueling IVF process, Heminsley thought her family was perfect. But then her husband began transitioning. This is not just a memoir of queer family-making, but, as the title hints, a story of getting back in touch with her body after an assault and Instagram’s obsession with exercise perfection.

Some Body to Love by Alexandra Heminsley: Finally pregnant after a grueling IVF process, Heminsley thought her family was perfect. But then her husband began transitioning. This is not just a memoir of queer family-making, but, as the title hints, a story of getting back in touch with her body after an assault and Instagram’s obsession with exercise perfection. The Light Years by Elizabeth Jane Howard: We’re reading the first volume of The Cazalet Chronicles for a supplementary book club meeting. I can hardly believe it was published in 1990; it’s such a detailed, convincing picture of 1937‒8 for a large, wealthy family in London and Sussex as war approaches. It’s so Downton Abbey; I love it and will continue the series.

The Light Years by Elizabeth Jane Howard: We’re reading the first volume of The Cazalet Chronicles for a supplementary book club meeting. I can hardly believe it was published in 1990; it’s such a detailed, convincing picture of 1937‒8 for a large, wealthy family in London and Sussex as war approaches. It’s so Downton Abbey; I love it and will continue the series. Outlawed by Anna North: After Reese Witherspoon chose it for her book club, there’s no chance you haven’t heard about this one. I requested it because I’m a huge fan of North’s previous novel, The Life and Death of Sophie Stark, but I’m also enjoying this alternative history/speculative take on the Western. It’s very Handmaid’s, with a fun medical slant.

Outlawed by Anna North: After Reese Witherspoon chose it for her book club, there’s no chance you haven’t heard about this one. I requested it because I’m a huge fan of North’s previous novel, The Life and Death of Sophie Stark, but I’m also enjoying this alternative history/speculative take on the Western. It’s very Handmaid’s, with a fun medical slant. Love After Love by Ingrid Persaud: It was already on my TBR after the

Love After Love by Ingrid Persaud: It was already on my TBR after the

Banana Skin Shoes, Badly Drawn Boy – His best since his annus mirabilis of 2002. Funky pop gems we’ve been caught dancing to by people walking past the living room window … oops! A track to try: “

Banana Skin Shoes, Badly Drawn Boy – His best since his annus mirabilis of 2002. Funky pop gems we’ve been caught dancing to by people walking past the living room window … oops! A track to try: “ Where the World Is Thin, Kris Drever – You may know him from Lau. Top musicianship and the most distinctive voice in folk. Nine folk-pop winners, including a lockdown anthem. A track to try: “

Where the World Is Thin, Kris Drever – You may know him from Lau. Top musicianship and the most distinctive voice in folk. Nine folk-pop winners, including a lockdown anthem. A track to try: “ Henry Martin, Edgelarks – Mention traditional folk and I’ll usually run a mile. But the musical skill and new arrangements, along with Hannah Martin’s rich alto, hit the spot. A track to try: “

Henry Martin, Edgelarks – Mention traditional folk and I’ll usually run a mile. But the musical skill and new arrangements, along with Hannah Martin’s rich alto, hit the spot. A track to try: “ Blindsided, Mark Erelli – We saw him perform the whole of his new folk-Americana album live in lockdown. Love the Motown and Elvis influences; his voice is at a peak. A track to try: “

Blindsided, Mark Erelli – We saw him perform the whole of his new folk-Americana album live in lockdown. Love the Motown and Elvis influences; his voice is at a peak. A track to try: “ American Foursquare, Denison Witmer – A gorgeous ode to family life in small-town Pennsylvania from a singer-songwriter whose career we’ve been following for upwards of 15 years. A track to try: “

American Foursquare, Denison Witmer – A gorgeous ode to family life in small-town Pennsylvania from a singer-songwriter whose career we’ve been following for upwards of 15 years. A track to try: “

The Living Sea of Waking Dreams by Richard Flanagan [Jan. 14, Chatto & Windus / May 25, Knopf] “In a world of perennial fire and growing extinctions, Anna’s aged mother … increasingly escapes through her hospital window … When Anna’s finger vanishes and a few months later her knee disappears, Anna too feels the pull of the window. … A strangely beautiful novel about hope and love and orange-bellied parrots.” I’ve had mixed success with Flanagan, but the blurb draws me and I’ve read good early reviews so far. [Library hold]

The Living Sea of Waking Dreams by Richard Flanagan [Jan. 14, Chatto & Windus / May 25, Knopf] “In a world of perennial fire and growing extinctions, Anna’s aged mother … increasingly escapes through her hospital window … When Anna’s finger vanishes and a few months later her knee disappears, Anna too feels the pull of the window. … A strangely beautiful novel about hope and love and orange-bellied parrots.” I’ve had mixed success with Flanagan, but the blurb draws me and I’ve read good early reviews so far. [Library hold] The Charmed Wife by Olga Grushin [Jan. 21, Hodder & Stoughton / Jan. 12, Putnam] “Cinderella married the man of her dreams – the perfect ending she deserved after diligently following all the fairy-tale rules. Yet now, two children and thirteen-and-a-half years later, things have gone badly wrong. One night, she sneaks out of the palace to get help from the Witch who, for a price, offers love potions to disgruntled housewives.” A feminist retelling. I loved Grushin’s previous novel, Forty Rooms. [Edelweiss download]

The Charmed Wife by Olga Grushin [Jan. 21, Hodder & Stoughton / Jan. 12, Putnam] “Cinderella married the man of her dreams – the perfect ending she deserved after diligently following all the fairy-tale rules. Yet now, two children and thirteen-and-a-half years later, things have gone badly wrong. One night, she sneaks out of the palace to get help from the Witch who, for a price, offers love potions to disgruntled housewives.” A feminist retelling. I loved Grushin’s previous novel, Forty Rooms. [Edelweiss download] The Prophets by Robert Jones Jr. [Jan. 21, Quercus / Jan. 5, G.P. Putnam’s Sons] “A singular and stunning debut novel about the forbidden union between two enslaved young men on a Deep South plantation, the refuge they find in each other, and a betrayal that threatens their existence.” Lots of hype about this one. I’m getting Days Without End vibes, and the mention of copious biblical references is a draw for me rather than a turn-off. The cover looks so much like the UK cover of

The Prophets by Robert Jones Jr. [Jan. 21, Quercus / Jan. 5, G.P. Putnam’s Sons] “A singular and stunning debut novel about the forbidden union between two enslaved young men on a Deep South plantation, the refuge they find in each other, and a betrayal that threatens their existence.” Lots of hype about this one. I’m getting Days Without End vibes, and the mention of copious biblical references is a draw for me rather than a turn-off. The cover looks so much like the UK cover of  Mrs Death Misses Death by Salena Godden [Jan. 28, Canongate] “Mrs Death has had enough. She is exhausted from spending eternity doing her job and now she seeks someone to unburden her conscience to. Wolf Willeford, a troubled young writer, is well acquainted with death, but until now hadn’t met Death in person – a black, working-class woman who shape-shifts and does her work unseen. Enthralled by her stories, Wolf becomes Mrs Death’s scribe, and begins to write her memoirs.” [NetGalley download / Library hold]

Mrs Death Misses Death by Salena Godden [Jan. 28, Canongate] “Mrs Death has had enough. She is exhausted from spending eternity doing her job and now she seeks someone to unburden her conscience to. Wolf Willeford, a troubled young writer, is well acquainted with death, but until now hadn’t met Death in person – a black, working-class woman who shape-shifts and does her work unseen. Enthralled by her stories, Wolf becomes Mrs Death’s scribe, and begins to write her memoirs.” [NetGalley download / Library hold] No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood [Feb. 16, Bloomsbury / Riverhead] “A woman known for her viral social media posts travels the world speaking to her adoring fans … Suddenly, two texts from her mother pierce the fray … [and] the woman confronts a world that seems to contain both an abundance of proof that there is goodness, empathy and justice in the universe, and a deluge of evidence to the contrary.” Lockwood’s memoir, Priestdaddy, is an all-time favorite of mine. [NetGalley download / Publisher request pending]

No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood [Feb. 16, Bloomsbury / Riverhead] “A woman known for her viral social media posts travels the world speaking to her adoring fans … Suddenly, two texts from her mother pierce the fray … [and] the woman confronts a world that seems to contain both an abundance of proof that there is goodness, empathy and justice in the universe, and a deluge of evidence to the contrary.” Lockwood’s memoir, Priestdaddy, is an all-time favorite of mine. [NetGalley download / Publisher request pending] A Town Called Solace by Mary Lawson [Feb. 18, Chatto & Windus / Feb. 16, Knopf Canada] “It’s North Ontario in 1972, and seven-year-old Clara’s teenage sister Rose has just run away from home. At the same time, a strange man – Liam – drives up to the house next door, which he has just inherited from Mrs Orchard, a kindly old woman who was friendly to Clara … A beautiful portrait of a small town, a little girl and an exploration of childhood.” I’ve loved the two Lawson novels I’ve read. [Publisher request pending]

A Town Called Solace by Mary Lawson [Feb. 18, Chatto & Windus / Feb. 16, Knopf Canada] “It’s North Ontario in 1972, and seven-year-old Clara’s teenage sister Rose has just run away from home. At the same time, a strange man – Liam – drives up to the house next door, which he has just inherited from Mrs Orchard, a kindly old woman who was friendly to Clara … A beautiful portrait of a small town, a little girl and an exploration of childhood.” I’ve loved the two Lawson novels I’ve read. [Publisher request pending] Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro [March 2, Faber & Faber / Knopf] Synopsis from Faber e-mail: “Klara and the Sun is the story of an ‘Artificial Friend’ who … is warned not to invest too much in the promises of humans. A luminous narrative about humanity, hope and the human heart.” I’m not an Ishiguro fan per se, but this looks set to be one of the biggest books of the year. I’m tempted to pre-order a signed copy as part of an early bird ticket to a Faber Members live-streamed event with him in early March.

Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro [March 2, Faber & Faber / Knopf] Synopsis from Faber e-mail: “Klara and the Sun is the story of an ‘Artificial Friend’ who … is warned not to invest too much in the promises of humans. A luminous narrative about humanity, hope and the human heart.” I’m not an Ishiguro fan per se, but this looks set to be one of the biggest books of the year. I’m tempted to pre-order a signed copy as part of an early bird ticket to a Faber Members live-streamed event with him in early March. Hot Stew by Fiona Mozley [March 18, Hodder & Stoughton / April 20, Algonquin Books] “The Soho that Precious and Tabitha live and work in is barely recognizable anymore. … Billionaire-owner Agatha wants to kick the women out to build expensive restaurants and luxury flats. Men like Robert, who visit the brothel, will have to go elsewhere. … An insightful and ambitious novel about property, ownership, wealth and inheritance.” This sounds very different to

Hot Stew by Fiona Mozley [March 18, Hodder & Stoughton / April 20, Algonquin Books] “The Soho that Precious and Tabitha live and work in is barely recognizable anymore. … Billionaire-owner Agatha wants to kick the women out to build expensive restaurants and luxury flats. Men like Robert, who visit the brothel, will have to go elsewhere. … An insightful and ambitious novel about property, ownership, wealth and inheritance.” This sounds very different to  Libertie by Kaitlyn Greenidge [March 30, Algonquin Books; April 29, Serpent’s Tail] “Coming of age as a free-born Black girl in Reconstruction-era Brooklyn, Libertie Sampson” is expected to follow in her mother’s footsteps as a doctor. “When a young man from Haiti proposes, she accepts, only to discover that she is still subordinate to him and all men. … Inspired by the life of one of the first Black female doctors in the United States.” I loved Greenidge’s underappreciated debut, We Love You, Charlie Freeman. [Edelweiss download]

Libertie by Kaitlyn Greenidge [March 30, Algonquin Books; April 29, Serpent’s Tail] “Coming of age as a free-born Black girl in Reconstruction-era Brooklyn, Libertie Sampson” is expected to follow in her mother’s footsteps as a doctor. “When a young man from Haiti proposes, she accepts, only to discover that she is still subordinate to him and all men. … Inspired by the life of one of the first Black female doctors in the United States.” I loved Greenidge’s underappreciated debut, We Love You, Charlie Freeman. [Edelweiss download] An Ordinary Wonder by Buki Papillon [April 9, Dialogue Books] “Richly imagined with art, proverbs and folk tales, this moving and modern novel follows Oto through life at home and at boarding school in Nigeria, through the heartbreak of living as a boy despite their profound belief they are a girl, and through a hunger for freedom that only a new life in the United States can offer. … a powerful coming-of-age story that explores complex desires as well as challenges of family, identity, gender and culture, and what it means to feel whole.”

An Ordinary Wonder by Buki Papillon [April 9, Dialogue Books] “Richly imagined with art, proverbs and folk tales, this moving and modern novel follows Oto through life at home and at boarding school in Nigeria, through the heartbreak of living as a boy despite their profound belief they are a girl, and through a hunger for freedom that only a new life in the United States can offer. … a powerful coming-of-age story that explores complex desires as well as challenges of family, identity, gender and culture, and what it means to feel whole.” Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead [May 4, Doubleday / Knopf] “In 1940s London, after a series of reckless romances and a spell flying to aid the war effort, Marian embarks on a treacherous, epic flight in search of the freedom she has always craved. She is never seen again. More than half a century later, Hadley Baxter, a troubled Hollywood starlet beset by scandal, is irresistibly drawn to play Marian Graves in her biopic.” I loved Seating Arrangements and have been waiting for a new Shipstead novel for seven years!

Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead [May 4, Doubleday / Knopf] “In 1940s London, after a series of reckless romances and a spell flying to aid the war effort, Marian embarks on a treacherous, epic flight in search of the freedom she has always craved. She is never seen again. More than half a century later, Hadley Baxter, a troubled Hollywood starlet beset by scandal, is irresistibly drawn to play Marian Graves in her biopic.” I loved Seating Arrangements and have been waiting for a new Shipstead novel for seven years! The Anthill by Julianne Pachico [May 6, Faber & Faber; this has been out since May 2020 in the USA, but was pushed back a year in the UK] “Linda returns to Colombia after 20 years away. Sent to England after her mother’s death when she was eight, she’s searching for the person who can tell her what’s happened in the time that has passed. Matty – Lina’s childhood confidant, her best friend – now runs a refuge called The Anthill for the street kids of Medellín.” Pachico was our Young Writer of the Year shadow panel winner.

The Anthill by Julianne Pachico [May 6, Faber & Faber; this has been out since May 2020 in the USA, but was pushed back a year in the UK] “Linda returns to Colombia after 20 years away. Sent to England after her mother’s death when she was eight, she’s searching for the person who can tell her what’s happened in the time that has passed. Matty – Lina’s childhood confidant, her best friend – now runs a refuge called The Anthill for the street kids of Medellín.” Pachico was our Young Writer of the Year shadow panel winner. Filthy Animals: Stories by Brandon Taylor [June 24, Daunt Books / June 21, Riverhead] “In the series of linked stories at the heart of Filthy Animals, set among young creatives in the American Midwest, a young man treads delicate emotional waters as he navigates a series of sexually fraught encounters with two dancers in an open relationship, forcing him to weigh his vulnerabilities against his loneliness.” Sounds like the perfect follow-up for those of us who loved his Booker-shortlisted debut novel,

Filthy Animals: Stories by Brandon Taylor [June 24, Daunt Books / June 21, Riverhead] “In the series of linked stories at the heart of Filthy Animals, set among young creatives in the American Midwest, a young man treads delicate emotional waters as he navigates a series of sexually fraught encounters with two dancers in an open relationship, forcing him to weigh his vulnerabilities against his loneliness.” Sounds like the perfect follow-up for those of us who loved his Booker-shortlisted debut novel,  Islands of Abandonment: Nature Rebounding in the Post-Human Landscape by Cal Flyn [Jan. 21, William Collins; June 1, Viking] “A variety of wildlife not seen in many lifetimes has rebounded on the irradiated grounds of Chernobyl. A lush forest supports thousands of species that are extinct or endangered everywhere else on earth in the Korean peninsula’s narrow DMZ. … Islands of Abandonment is a tour through these new ecosystems … ultimately a story of redemption”. Good news about nature is always nice to find. [Publisher request pending]

Islands of Abandonment: Nature Rebounding in the Post-Human Landscape by Cal Flyn [Jan. 21, William Collins; June 1, Viking] “A variety of wildlife not seen in many lifetimes has rebounded on the irradiated grounds of Chernobyl. A lush forest supports thousands of species that are extinct or endangered everywhere else on earth in the Korean peninsula’s narrow DMZ. … Islands of Abandonment is a tour through these new ecosystems … ultimately a story of redemption”. Good news about nature is always nice to find. [Publisher request pending] The Believer by Sarah Krasnostein [March 2, Text Publishing – might be Australia only; I’ll have an eagle eye out for news of a UK release] “This book is about ghosts and gods and flying saucers; certainty in the absence of knowledge; how the stories we tell ourselves to deal with the distance between the world as it is and as we’d like it to be can stunt us or save us.” Krasnostein was our Wellcome Book Prize shadow panel winner in 2019. She told us a bit about this work in progress at the prize ceremony and I was intrigued!

The Believer by Sarah Krasnostein [March 2, Text Publishing – might be Australia only; I’ll have an eagle eye out for news of a UK release] “This book is about ghosts and gods and flying saucers; certainty in the absence of knowledge; how the stories we tell ourselves to deal with the distance between the world as it is and as we’d like it to be can stunt us or save us.” Krasnostein was our Wellcome Book Prize shadow panel winner in 2019. She told us a bit about this work in progress at the prize ceremony and I was intrigued! A History of Scars: A Memoir by Laura Lee [March 2, Atria Books; no sign of a UK release] “In this stunning debut, Laura Lee weaves unforgettable and eye-opening essays on a variety of taboo topics. … Through the vivid imagery of mountain climbing, cooking, studying writing, and growing up Korean American, Lee explores the legacy of trauma on a young queer child of immigrants as she reconciles the disparate pieces of existence that make her whole.” I was drawn to this one by Roxane Gay’s high praise.

A History of Scars: A Memoir by Laura Lee [March 2, Atria Books; no sign of a UK release] “In this stunning debut, Laura Lee weaves unforgettable and eye-opening essays on a variety of taboo topics. … Through the vivid imagery of mountain climbing, cooking, studying writing, and growing up Korean American, Lee explores the legacy of trauma on a young queer child of immigrants as she reconciles the disparate pieces of existence that make her whole.” I was drawn to this one by Roxane Gay’s high praise. Everybody: A Book about Freedom by Olivia Laing [April 29, Picador / May 4, W. W. Norton & Co.] “The body is a source of pleasure and of pain, at once hopelessly vulnerable and radiant with power. … Laing charts an electrifying course through the long struggle for bodily freedom, using the life of the renegade psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich to explore gay rights and sexual liberation, feminism, and the civil rights movement.” Wellcome Prize fodder from the author of

Everybody: A Book about Freedom by Olivia Laing [April 29, Picador / May 4, W. W. Norton & Co.] “The body is a source of pleasure and of pain, at once hopelessly vulnerable and radiant with power. … Laing charts an electrifying course through the long struggle for bodily freedom, using the life of the renegade psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich to explore gay rights and sexual liberation, feminism, and the civil rights movement.” Wellcome Prize fodder from the author of  Rooted: Life at the Crossroads of Science, Nature, and Spirit by Lyanda Lynn Haupt [May 4, Little, Brown Spark; no sign of a UK release] “Cutting-edge science supports a truth that poets, artists, mystics, and earth-based cultures across the world have proclaimed over millennia: life on this planet is radically interconnected. … In the tradition of Rachel Carson, Elizabeth Kolbert, and Mary Oliver, Haupt writes with urgency and grace, reminding us that at the crossroads of science, nature, and spirit we find true hope.” I’m a Haupt fan.

Rooted: Life at the Crossroads of Science, Nature, and Spirit by Lyanda Lynn Haupt [May 4, Little, Brown Spark; no sign of a UK release] “Cutting-edge science supports a truth that poets, artists, mystics, and earth-based cultures across the world have proclaimed over millennia: life on this planet is radically interconnected. … In the tradition of Rachel Carson, Elizabeth Kolbert, and Mary Oliver, Haupt writes with urgency and grace, reminding us that at the crossroads of science, nature, and spirit we find true hope.” I’m a Haupt fan.

Youngest author read this year: You might assume it was 16-year-old Dara McAnulty with Diary of a Young Naturalist, which won the Wainwright Prize (as well as the An Post Irish Book Award for Newcomer of the Year, the Books Are My Bag Reader Award for Non-Fiction, and the Hay Festival Book of the Year!) … or Thunberg, above, who was 16 when her book came out. They were indeed tied for youngest until, earlier in December, I started reading The House without Windows (1927) by Barbara Newhall Follett, a bizarre fantasy novel published when the child prodigy was 12.

Youngest author read this year: You might assume it was 16-year-old Dara McAnulty with Diary of a Young Naturalist, which won the Wainwright Prize (as well as the An Post Irish Book Award for Newcomer of the Year, the Books Are My Bag Reader Award for Non-Fiction, and the Hay Festival Book of the Year!) … or Thunberg, above, who was 16 when her book came out. They were indeed tied for youngest until, earlier in December, I started reading The House without Windows (1927) by Barbara Newhall Follett, a bizarre fantasy novel published when the child prodigy was 12.

The book that made me laugh the most: Kay’s Anatomy by Adam Kay

The book that made me laugh the most: Kay’s Anatomy by Adam Kay The book that put a song in my head every single time I looked at it, much less read it: I Am an Island by Tamsin Calidas (i.e., “I Am a Rock” by Simon and Garfunkel, which, as my husband pointed out, has very appropriate lyrics for 2020: “In a deep and dark December / I am alone / Gazing from my window to the streets below … Hiding in my room / Safe within my womb / I touch no one and no one touches me.”)

The book that put a song in my head every single time I looked at it, much less read it: I Am an Island by Tamsin Calidas (i.e., “I Am a Rock” by Simon and Garfunkel, which, as my husband pointed out, has very appropriate lyrics for 2020: “In a deep and dark December / I am alone / Gazing from my window to the streets below … Hiding in my room / Safe within my womb / I touch no one and no one touches me.”)

Most unexpectedly apt lines encountered in a book: “People came to church wearing masks, if they came at all. They’d sit as far from each other as they could.” (Gilead by Marilynne Robinson. Describing not COVID-19 times but the Spanish flu.)

Most unexpectedly apt lines encountered in a book: “People came to church wearing masks, if they came at all. They’d sit as far from each other as they could.” (Gilead by Marilynne Robinson. Describing not COVID-19 times but the Spanish flu.) Most ironic lines encountered in a book: “September 12—In the ongoing hearings, Senator Joseph Biden pledges to consider the Bork nomination ‘with total objectivity,’ adding, ‘You have that on my honor not only as a senator, but also as the Prince of Wales.’ … October 1—Senator Joseph Biden is forced to withdraw from the Democratic presidential race when it is learned that he is in fact an elderly Norwegian woman.” (from the 1987 roundup in Dave Barry’s Greatest Hits – Biden has been on the U.S. political scene, and mocked, for 3.5+ decades!)

Most ironic lines encountered in a book: “September 12—In the ongoing hearings, Senator Joseph Biden pledges to consider the Bork nomination ‘with total objectivity,’ adding, ‘You have that on my honor not only as a senator, but also as the Prince of Wales.’ … October 1—Senator Joseph Biden is forced to withdraw from the Democratic presidential race when it is learned that he is in fact an elderly Norwegian woman.” (from the 1987 roundup in Dave Barry’s Greatest Hits – Biden has been on the U.S. political scene, and mocked, for 3.5+ decades!) Best first line encountered this year: “And then there was the day when Addie Moore made a call on Louis Waters.” (Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf)

Best first line encountered this year: “And then there was the day when Addie Moore made a call on Louis Waters.” (Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf)

The downright strangest books I read this year: Enter the Aardvark by Jessica Anthony, A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom by John Boyne, The House Without Windows by Barbara Newhall Follett, and The Child in Time by Ian McEwan

The downright strangest books I read this year: Enter the Aardvark by Jessica Anthony, A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom by John Boyne, The House Without Windows by Barbara Newhall Follett, and The Child in Time by Ian McEwan

Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: Through Ifemelu’s years of studying, working, and blogging her way around the Eastern seaboard of the United States, Adichie explores the ways in which the experience of an African abroad differs from that of African Americans. On a sentence level as well as at a macro plot level, this was utterly rewarding.

Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: Through Ifemelu’s years of studying, working, and blogging her way around the Eastern seaboard of the United States, Adichie explores the ways in which the experience of an African abroad differs from that of African Americans. On a sentence level as well as at a macro plot level, this was utterly rewarding. Year of Wonders by Geraldine Brooks: In 1665, with the Derbyshire village of Eyam in the grip of the Plague, the drastic decision is made to quarantine it. Frustration with the pastor’s ineffectuality attracts people to religious extremism. Anna’s intimate first-person narration and the historical recreation are faultless, and there are so many passages that feel apt.

Year of Wonders by Geraldine Brooks: In 1665, with the Derbyshire village of Eyam in the grip of the Plague, the drastic decision is made to quarantine it. Frustration with the pastor’s ineffectuality attracts people to religious extremism. Anna’s intimate first-person narration and the historical recreation are faultless, and there are so many passages that feel apt. Shotgun Lovesongs by Nickolas Butler: Four childhood friends from Little Wing, Wisconsin. Which bonds will last, and which will be strained to the breaking point? This is a book full of nostalgia and small-town atmosphere. All the characters wonder whether they’ve made the right decisions or gotten stuck. A lot of bittersweet moments, but also comic ones.

Shotgun Lovesongs by Nickolas Butler: Four childhood friends from Little Wing, Wisconsin. Which bonds will last, and which will be strained to the breaking point? This is a book full of nostalgia and small-town atmosphere. All the characters wonder whether they’ve made the right decisions or gotten stuck. A lot of bittersweet moments, but also comic ones. Kindred by Octavia E. Butler: A perfect time-travel novel for readers who quail at science fiction. Dana, an African American writer in Los Angeles, is dropped into early-nineteenth-century Maryland. This was such an absorbing read, with first-person narration that makes you feel you’re right there alongside Dana on her perilous travels.

Kindred by Octavia E. Butler: A perfect time-travel novel for readers who quail at science fiction. Dana, an African American writer in Los Angeles, is dropped into early-nineteenth-century Maryland. This was such an absorbing read, with first-person narration that makes you feel you’re right there alongside Dana on her perilous travels. Dominicana by Angie Cruz: Ana Canción is just 15 when she arrives in New York from the Dominican Republic on the first day of 1965 to start her new life as the wife of Juan Ruiz. An arranged marriage and arriving in a country not knowing a word of the language: this is a valuable immigration story that stands out for its plucky and confiding narrator.

Dominicana by Angie Cruz: Ana Canción is just 15 when she arrives in New York from the Dominican Republic on the first day of 1965 to start her new life as the wife of Juan Ruiz. An arranged marriage and arriving in a country not knowing a word of the language: this is a valuable immigration story that stands out for its plucky and confiding narrator. Ella Minnow Pea by Mark Dunn: A book of letters in multiple sense. Laugh-out-loud silliness plus a sly message about science and reason over superstition = a rare combination that made this an enduring favorite. On my reread I was more struck by the political satire: freedom of speech is endangered in a repressive society slavishly devoted to a sacred text.

Ella Minnow Pea by Mark Dunn: A book of letters in multiple sense. Laugh-out-loud silliness plus a sly message about science and reason over superstition = a rare combination that made this an enduring favorite. On my reread I was more struck by the political satire: freedom of speech is endangered in a repressive society slavishly devoted to a sacred text. Love Medicine by Louise Erdrich: Interlocking stories that span half a century in the lives of a couple of Chippewa families that sprawl out from a North Dakota reservation. Looking for love, looking for work. Getting lucky, getting even. Their problems are the stuff of human nature and contemporary life. I adored the descriptions of characters and of nature.

Love Medicine by Louise Erdrich: Interlocking stories that span half a century in the lives of a couple of Chippewa families that sprawl out from a North Dakota reservation. Looking for love, looking for work. Getting lucky, getting even. Their problems are the stuff of human nature and contemporary life. I adored the descriptions of characters and of nature. Notes from an Exhibition by Patrick Gale: Nonlinear chapters give snapshots of the life of a bipolar artist and her interactions with her husband and children. Their Quakerism sets up a calm and compassionate atmosphere, but also allows family secrets to proliferate. The novel questions patterns of inheritance and the possibility of happiness.

Notes from an Exhibition by Patrick Gale: Nonlinear chapters give snapshots of the life of a bipolar artist and her interactions with her husband and children. Their Quakerism sets up a calm and compassionate atmosphere, but also allows family secrets to proliferate. The novel questions patterns of inheritance and the possibility of happiness. Confession with Blue Horses by Sophie Hardach: When Ella’s parents, East German art historians who came under Stasi surveillance, were caught trying to defect, their children were taken away from them. Decades later, Ella is determined to find her missing brother and learn what really happened to her mother. Eye-opening and emotionally involving.

Confession with Blue Horses by Sophie Hardach: When Ella’s parents, East German art historians who came under Stasi surveillance, were caught trying to defect, their children were taken away from them. Decades later, Ella is determined to find her missing brother and learn what really happened to her mother. Eye-opening and emotionally involving. The Go-Between by L.P. Hartley: Twelve-year-old Leo Colston is invited to spend July at his school friend’s home, Brandham Hall. You know from the famous first line on that this juxtaposes past and present. It’s masterfully done: the class divide, the picture of childhood tipping over into the teenage years, the oppressive atmosphere, the comical touches.

The Go-Between by L.P. Hartley: Twelve-year-old Leo Colston is invited to spend July at his school friend’s home, Brandham Hall. You know from the famous first line on that this juxtaposes past and present. It’s masterfully done: the class divide, the picture of childhood tipping over into the teenage years, the oppressive atmosphere, the comical touches. The Emperor’s Children by Claire Messud: A 9/11 novel. The trio of protagonists, all would-be journalists aged 30, have never really had to grow up; now it’s time to get out from under the shadow of a previous generation and reassess what is admirable and who is expendable. This was thoroughly engrossing. Great American Novel territory, for sure.

The Emperor’s Children by Claire Messud: A 9/11 novel. The trio of protagonists, all would-be journalists aged 30, have never really had to grow up; now it’s time to get out from under the shadow of a previous generation and reassess what is admirable and who is expendable. This was thoroughly engrossing. Great American Novel territory, for sure. My Year of Meats by Ruth Ozeki: A Japanese-American filmmaker is tasked with finding all-American families and capturing their daily lives – and best meat recipes. There is a clear message here about cheapness and commodification, but Ozeki filters it through the wrenching stories of two women with fertility problems. Bold if at times discomforting.

My Year of Meats by Ruth Ozeki: A Japanese-American filmmaker is tasked with finding all-American families and capturing their daily lives – and best meat recipes. There is a clear message here about cheapness and commodification, but Ozeki filters it through the wrenching stories of two women with fertility problems. Bold if at times discomforting. Small Ceremonies by Carol Shields: An impeccable novella, it brings its many elements to a satisfying conclusion and previews the author’s enduring themes. Something of a sly academic comedy à la David Lodge, it’s laced with Shields’s quiet wisdom on marriage, parenting, the writer’s vocation, and the difficulty of ever fully understanding another life.

Small Ceremonies by Carol Shields: An impeccable novella, it brings its many elements to a satisfying conclusion and previews the author’s enduring themes. Something of a sly academic comedy à la David Lodge, it’s laced with Shields’s quiet wisdom on marriage, parenting, the writer’s vocation, and the difficulty of ever fully understanding another life. Larry’s Party by Carol Shields: The sweep of Larry’s life, from youth to middle age, is presented chronologically through chapters that are more like linked short stories: they focus on themes (family, friends, career, sex, clothing, health) and loop back to events to add more detail and new insight. I found so much to relate to in Larry’s story; Larry is really all of us.

Larry’s Party by Carol Shields: The sweep of Larry’s life, from youth to middle age, is presented chronologically through chapters that are more like linked short stories: they focus on themes (family, friends, career, sex, clothing, health) and loop back to events to add more detail and new insight. I found so much to relate to in Larry’s story; Larry is really all of us. Abide with Me by Elizabeth Strout: Tyler Caskey is a widowed pastor whose five-year-old daughter has gone mute and started acting up. As usual, Strout’s characters are painfully real, flawed people, often struggling with damaging obsessions. She tenderly probes the dark places of the community and its minister’s doubts, but finds the light shining through.

Abide with Me by Elizabeth Strout: Tyler Caskey is a widowed pastor whose five-year-old daughter has gone mute and started acting up. As usual, Strout’s characters are painfully real, flawed people, often struggling with damaging obsessions. She tenderly probes the dark places of the community and its minister’s doubts, but finds the light shining through. The Wife by Meg Wolitzer: On the way to Finland, where her genius writer husband will accept the prestigious Helsinki Prize, Joan finally decides to leave him. Alternating between the trip and earlier in their marriage, this is deceptively thoughtful with a juicy twist. Joan’s narration is witty and the point about the greater value attributed to men’s work is still valid.

The Wife by Meg Wolitzer: On the way to Finland, where her genius writer husband will accept the prestigious Helsinki Prize, Joan finally decides to leave him. Alternating between the trip and earlier in their marriage, this is deceptively thoughtful with a juicy twist. Joan’s narration is witty and the point about the greater value attributed to men’s work is still valid. Winter Journal by Paul Auster: Approaching age 64, the winter of his life, Auster decided to assemble his most visceral memories: scars, accidents and near-misses, what his hands felt and his eyes observed. The use of the second person draws readers in. I particularly enjoyed the tour through the 21 places he’s lived. One of the most remarkable memoirs I’ve ever read.

Winter Journal by Paul Auster: Approaching age 64, the winter of his life, Auster decided to assemble his most visceral memories: scars, accidents and near-misses, what his hands felt and his eyes observed. The use of the second person draws readers in. I particularly enjoyed the tour through the 21 places he’s lived. One of the most remarkable memoirs I’ve ever read. Heat by Bill Buford: Buford was an unpaid intern at Mario Batali’s famous New York City restaurant, Babbo. In between behind-the-scenes looks at frantic sessions of food prep, Buford traces Batali’s culinary pedigree through Italy and London. Exactly what I want from food writing: interesting trivia, quick pace, humor, and mouthwatering descriptions.

Heat by Bill Buford: Buford was an unpaid intern at Mario Batali’s famous New York City restaurant, Babbo. In between behind-the-scenes looks at frantic sessions of food prep, Buford traces Batali’s culinary pedigree through Italy and London. Exactly what I want from food writing: interesting trivia, quick pace, humor, and mouthwatering descriptions. Sixpence House: Lost in a Town of Books by Paul Collins: Collins moved to Hay-on-Wye with his wife and toddler son, hoping to make a life there. As he edited the manuscript of his first book, he started working for Richard Booth, the eccentric bookseller who crowned himself King of Hay. Warm, funny, and nostalgic. An enduring favorite of mine.

Sixpence House: Lost in a Town of Books by Paul Collins: Collins moved to Hay-on-Wye with his wife and toddler son, hoping to make a life there. As he edited the manuscript of his first book, he started working for Richard Booth, the eccentric bookseller who crowned himself King of Hay. Warm, funny, and nostalgic. An enduring favorite of mine. A Year on the Wing by Tim Dee: From a life spent watching birds, Dee weaves a mesh of memories and recent experiences, meditations and allusions. He moves from one June to the next and from Shetland to Zambia. The most powerful chapter is about watching peregrines at Bristol’s famous bridge – where he also, as a teen, saw a man commit suicide.

A Year on the Wing by Tim Dee: From a life spent watching birds, Dee weaves a mesh of memories and recent experiences, meditations and allusions. He moves from one June to the next and from Shetland to Zambia. The most powerful chapter is about watching peregrines at Bristol’s famous bridge – where he also, as a teen, saw a man commit suicide. The Frayed Atlantic Edge by David Gange: While kayaking down the western coast of the British Isles and Ireland, Gange delves into the folklore, geology, history, local language and wildlife of each region and island group – from the extreme north of Scotland at Muckle Flugga to the southwest tip of Cornwall. An intricate interdisciplinary approach.

The Frayed Atlantic Edge by David Gange: While kayaking down the western coast of the British Isles and Ireland, Gange delves into the folklore, geology, history, local language and wildlife of each region and island group – from the extreme north of Scotland at Muckle Flugga to the southwest tip of Cornwall. An intricate interdisciplinary approach. Traveling Mercies: Some Thoughts on Faith by Anne Lamott: There is a lot of bereavement and other dark stuff here, yet an overall lightness of spirit prevails. A college dropout and addict, Lamott didn’t walk into a church and get clean until her early thirties. Each essay is perfectly constructed, countering everyday angst with a fumbling faith.

Traveling Mercies: Some Thoughts on Faith by Anne Lamott: There is a lot of bereavement and other dark stuff here, yet an overall lightness of spirit prevails. A college dropout and addict, Lamott didn’t walk into a church and get clean until her early thirties. Each essay is perfectly constructed, countering everyday angst with a fumbling faith. In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado: This has my deepest admiration for how it prioritizes voice, theme and scene, gleefully does away with chronology and (not directly relevant) backstory, and engages with history, critical theory and the tropes of folk tales to interrogate her experience of same-sex domestic violence. (Second-person narration again!)

In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado: This has my deepest admiration for how it prioritizes voice, theme and scene, gleefully does away with chronology and (not directly relevant) backstory, and engages with history, critical theory and the tropes of folk tales to interrogate her experience of same-sex domestic violence. (Second-person narration again!) Period Piece by Gwen Raverat: Raverat was a granddaughter of Charles Darwin. This is a portrait of what it was like to grow up in a particular time and place (Cambridge from the 1880s to about 1909). Not just an invaluable record of domestic history, it is a funny and impressively thorough memoir that serves as a model for how to capture childhood.

Period Piece by Gwen Raverat: Raverat was a granddaughter of Charles Darwin. This is a portrait of what it was like to grow up in a particular time and place (Cambridge from the 1880s to about 1909). Not just an invaluable record of domestic history, it is a funny and impressively thorough memoir that serves as a model for how to capture childhood. The Universal Christ by Richard Rohr: I’d read two of the Franciscan priest’s previous books but was really blown away by the wisdom in this one. The argument in a nutshell is that Western individualism has perverted the good news of Jesus, which is renewal for everything and everyone. A real gamechanger. My copy is littered with Post-it flags.

The Universal Christ by Richard Rohr: I’d read two of the Franciscan priest’s previous books but was really blown away by the wisdom in this one. The argument in a nutshell is that Western individualism has perverted the good news of Jesus, which is renewal for everything and everyone. A real gamechanger. My copy is littered with Post-it flags. A Three Dog Life by Abigail Thomas: A memoir in essays about her husband’s TBI and what kept her going. Unassuming and heart on sleeve, Thomas wrote one of the most beautiful books out there about loss and memory. It is one of the first memoirs I remember reading; it made a big impression the first time, but I loved it even more on a reread.

A Three Dog Life by Abigail Thomas: A memoir in essays about her husband’s TBI and what kept her going. Unassuming and heart on sleeve, Thomas wrote one of the most beautiful books out there about loss and memory. It is one of the first memoirs I remember reading; it made a big impression the first time, but I loved it even more on a reread. On Silbury Hill by Adam Thorpe: Explores the fragmentary history of the manmade Neolithic mound and various attempts to excavate it, but ultimately concludes we will never understand how and why it was made. A flawless integration of personal and wider history, as well as a profound engagement with questions of human striving and hubris.

On Silbury Hill by Adam Thorpe: Explores the fragmentary history of the manmade Neolithic mound and various attempts to excavate it, but ultimately concludes we will never understand how and why it was made. A flawless integration of personal and wider history, as well as a profound engagement with questions of human striving and hubris.