Letters and Papers from Prison by Dietrich Bonhoeffer (#NovNov22 and #GermanLitMonth)

I’m rounding out our nonfiction week of Novellas in November with a review that also counts towards German Literature Month, hosted by Lizzy Siddal.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a German pastor and theologian, was hanged at a Nazi concentration camp in 1945 for his role in the Resistance and in planning a failed 1944 assassination attempt on Adolf Hitler.

The version I read (a 1959 Fontana reprint of the 1953 SCM Press edition) is certainly only a selection, as Bonhoeffer’s papers from prison in his Collected Works now run to 800 pages. After some letters to his parents, the largest section here is made up of “Letters to a Friend,” who I take it was the book’s editor, Eberhard Bethge, a seminary student of Bonhoeffer’s and his literary executor as well as his nephew by marriage.

The version I read (a 1959 Fontana reprint of the 1953 SCM Press edition) is certainly only a selection, as Bonhoeffer’s papers from prison in his Collected Works now run to 800 pages. After some letters to his parents, the largest section here is made up of “Letters to a Friend,” who I take it was the book’s editor, Eberhard Bethge, a seminary student of Bonhoeffer’s and his literary executor as well as his nephew by marriage.

Bonhoeffer comes across as steadfast and cheerful. He is grateful for his parents’ care packages, which included his latest philosophy and theology book requests as well as edible treats, and for news of family and acquaintances. To Bethge he expresses concern over the latter’s military service in Italy and delight at his marriage and the birth of a son named Dietrich in his honour. (Among the miscellaneous papers included at the end of this volume are a wedding sermon and thoughts on baptism to tie into those occasions.)

Maintaining a vigorous life of the mind sustained Bonhoeffer through his two years in prison. He downplays the physical challenges of his imprisonment, such as poor food and stifling heat during the summer, acknowledging that the mental toll is more difficult. The rhythm of the Church year is a constant support for him. In his first November there he writes that prison life is like Advent: all one can do is wait and hope. I noted many lines about endurance through suffering and striking a balance between defiance and acceptance:

Resistance and submission are both equally necessary at different times.

It is not some religious act which makes a Christian what he is, but participation in the suffering of God in the life of the world.

not only action, but also suffering is a way to freedom.

Bonhoeffer won over wardens who were happy to smuggle out his letters and papers, most of which have survived apart from a small, late selection that were burned so as not to be incriminating. Any references to the Resistance and the plot to kill Hitler were in code; there are footnotes here to identify them.

The additional non-epistolary material – aphorisms, poems and the abovementioned sermons – is a bit harder going. Although there is plenty of theological content in the letters to Bethge, much of it is comprehensible in context and one could always skip the couple of passages where he goes into more depth.

Reading the foreword and some additional information online gave me an even greater appreciation for Bonhoeffer’s bravery. After a lecture tour of the States in 1939, American friends urged him to stay in the country and not return to Germany. He didn’t take that easier path, nor did he allow a prison guard to help him escape. For as often as he states in his letters the hope that he will be reunited with his parents and friends, he must have known what was coming for him as a vocal opponent of the regime, and he faced it courageously. It blows my mind to think that he died at 39 (my age), and left so much written material behind. His posthumous legacy has been immense.

[Translated from the German by Reginald H. Fuller]

(Free from a fellow church member)

[187 pages]

Nonfiction November “Stranger than Fiction”: The Boys in the Boat

I’m taking a quick break from novellas coverage but keeping up the nonfiction focus with this week’s Nonfiction November prompt, “Stranger than Fiction,” hosted by Christopher at Plucked from the Stacks: “This week we’re focusing on all the great nonfiction books that almost don’t seem real. A sports biography involving overcoming massive obstacles, a profile on a bizarre scam, a look into the natural wonders in our world—basically, if it makes your jaw drop, you can highlight it for this week’s topic.” I would also interpret this brief to refer to nonfiction that reads as fluently as a novel, and on both counts this book stands out.

The Boys in the Boat: Nine Americans and Their Epic Quest for Gold at the 1936 Berlin Olympics by Daniel James Brown (2013)

We read this for my book club a couple of months ago, on the recommendation of one of our members’ spouses. I was dubious because I don’t read history books, and don’t enjoy playing or watching sports, so a sport + history book sounded like a real snoozefest, but that couldn’t have been further from the truth.

Brown focuses on one of the University of Washington rowers, Joe Rantz, in effect making him the protagonist of a classic underdog story. The college team in general, and Rantz in particular, were unlikely champions. Rantz lost his mother young and, abandoned by his father multiple times, had to make a living by his wits in the Seattle area, sometimes resorting to illegal schemes like poaching and selling liquor during Prohibition, but also logging and working in dam construction. Even among the teammates who became his de facto family, he was bullied for coming from poverty and for his enthusiasm for folksy music. That we come to know and care deeply for Rantz testifies to how well Brown recreates his life story – largely via Rantz’s daughter’s reminiscences, though Brown did meet Rantz before his death.

Another central character is world-renowned boat designer George Pocock, an Englishman who set up shop on the Washington campus. Boatbuilding and rowing both come across as admirable skills involving hard physical labour, scientific precision and an artist’s mind. I was surprised by how much I enjoyed reading about the technical details of woodworking and rowing. Brown emphasizes the psychological as well as the physical challenges of rowing – “mind in boat” is a catchphrase reminding rowers to give their total attention for there to be harmony between teammates. Individual talent is only useful insomuch as it boosts collective performance, and there has to be a perfect balance between speed, power and technique. Often, it means going past the pain barrier: “Competitive rowing is an undertaking of extraordinary beauty preceded by brutal punishment,” as the author sums it up.

(After reading the book, some of us went on a fieldtrip to see the boating club where the woman who recommended the book rows as an amateur. It wasn’t until I saw the rowers out on the Thames that I realized that only the coxswain – the one who sits at the back of the boat and calls out the orders – faces forward, while all the other rowers are facing backwards. That feels metaphorically significant, like you have to trust where the journey is taking you all together rather than relying on your own sight.)

All along, Brown subtly weaves in the historical background: Depression-era Seattle with its shantytowns, and the rise of Hitler in Germany. Joseph Goebbels and Leni Riefenstahl were key propagandists, whitewashing the city in advance of the Olympics to make a good impression on foreign visitors. Some atrocities had already been committed, and purification policies were in place, yet the Nazis fooled many with a façade of efficiency and cleanliness.

I have deep admiration for books, fiction or non-, that can maintain suspense even though you know the outcome. The pacing really works here. Most of the action is pre-Berlin, which keeps the tension high. (The only times when my attention waned was in the blow-by-blow accounts of preliminary races.) There were so many mishaps associated with the Olympic race that it truly is amazing that the U.S. team pulled through to win – I’ll leave the specifics for future readers to discover. But there are a couple ‘stranger than fiction’ details of the book that I do want to pull out: Joe’s father and brother each married one sister from a set of twins; and actor Hugh Laurie’s father was on the Great Britain rowing team at the 1936 Olympics.

The fires and heatwave of 1936 felt familiar, as did the hairstyles and fashions in the black-and-white photos (but the ‘boys’ themselves look more like 35-year-olds than modern college students). In some ways it seemed that little has changed, but then other facts feel impossibly outdated – e.g., sperm whale oil was used to oil the boats.

This might seem like a ‘dad book’ – indeed, several of us passed the book on to our fathers/-in-law after reading – but in fact it has very broad appeal and is one I’d be likely to recommend to any big readers, even if they’re not keen on nonfiction. It’s one of my most memorable reads of the year so far. And whether you fancy reading the book or not, you may want to look out for the George Clooney-directed film, coming out next year. (Secondhand purchase)

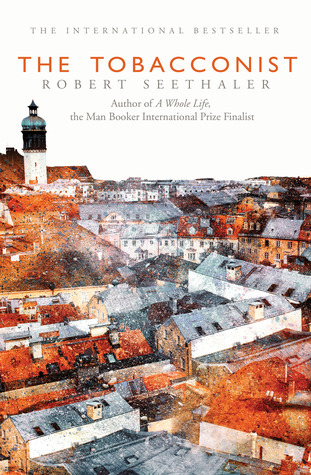

German Lit Month: The Tobacconist by Robert Seethaler

I don’t participate in a lot of blogger challenges (though I’ll be doing “Novellas in November” on Monday); it’s more of a coincidence that I finished Austrian writer Robert Seethaler’s excellent The Tobacconist (translated from the German by Charlotte Collins) towards the end of German literature month.

You may recall that I read Seethaler’s previous novel, A Whole Life, on my European travels this past summer, and didn’t think too much of it. I’d read so much praise for its sparse style, but I couldn’t grasp the appeal. Here’s what I wrote about it at the time: “This novella set in the Austrian Alps is the story of Andreas Egger – at various times a farmer, a prisoner of war, and a tourist guide. Various things happen to him, most of them bad. I have trouble pinpointing why Stoner is a masterpiece whereas this is just kind of boring. There’s a great avalanche scene, though.”

But I’m very glad that I tried again with Seethaler, because The Tobacconist is one of the few best novels I’ve read this year, and very much a book for our times despite being set in 1937–8.

But I’m very glad that I tried again with Seethaler, because The Tobacconist is one of the few best novels I’ve read this year, and very much a book for our times despite being set in 1937–8.

Seventeen-year-old Franz Huchel’s life changes for good when his mother sends him away from his quiet lakeside village to work for her old friend Otto Trsnyek, a Vienna tobacconist. “In [Franz’s] mind’s eye the future appeared like the line of a far distant shore materializing out of the morning fog: still a little blurred and unclear, but promising and beautiful, too.”

Though the First World War left him with only one leg, Trsnyek is a firebrand. Instead of keeping his head down while selling his cigars and newspapers, he makes his political opinions known. This sees him branded as a “Jew lover” and persecuted accordingly. One of the Jews he dares to associate with is Sigmund Freud, who is a regular customer even though he already has throat cancer and will die just two years later.

Especially after he falls in love with Anezka, a flirtatious but mercurial Bohemian girl, Franz turns to Professor Freud for life advice. “So I’m asking you: have I gone mad? Or has the whole world gone mad?” The professor replies, “yes, the world has gone mad. And … have no illusions, it’s going to get a lot madder than this.”

Through free indirect speech, the thought lives of the various characters, and the postcards and letters that pass between Franz and his mother, Seethaler gradually and subtly reveals the deepening worry over the rise of Hitler and the situation of the Jews. This novel is so many things: a coming-of-age story, a bittersweet romance, an out-of-the-ordinary World War II/Holocaust precursor, and a perennially relevant reminder of the importance of finding the inner courage to stand up to oppressive systems.

Freud and his family had enough money and influence to buy their way to England. So many did not escape Hitler’s regime. I knew that, but discovered it anew in this outstanding novel.

Some favorite passages:

Dear Mother,

I’ve been here in the city for quite a while now, yet to be honest it seems to me that everything just gets stranger. But maybe it’s like that all through life—from the moment you’re born, with every single day, you grow a little bit further away from yourself until one day you don’t know where you are any more. Can that really be the way it is?

And as more than twenty thousand supporters bellowed their assent into the clear Tyrolean mountain air, Adolf Hitler was probably sitting beside the radio somewhere in Berlin, licking his lips. Austria lay before him like a steaming schnitzel on a plate. Now was the time to carve it up. … People were cosseting their faint-hearted troubles and hadn’t even noticed yet that the earth beneath their feet was burning.

(from a letter from Mama) Just imagine, Hitler hangs on the wall even in the restaurant and the school now. Right next to Jesus. Although we have no idea what they think of each other.

Freud: “Most paths do at least seem vaguely familiar to me. But it’s not actually our destiny to know the paths. Our destiny is precisely not to know them. We don’t come into this world to find answers, but to ask questions. We grope around, as it were, in perpetual darkness, and it’s only if we’re very lucky that we sometimes see a little flicker of light. And only with a great deal of courage or persistence or stupidity—or, best of all, all three at once—can we make our mark here and there, indicate the way.”

My rating:

Happy Thanksgiving to all my American readers! In previous years we’ve been able to find canned pumpkin in the UK to make a pumpkin pie, but alas, this year there have been supply issues (my husband blames Brexit). Nor can we find a real pumpkin – they disappear from the shops after Halloween. Without pumpkin pie it doesn’t feel much like Thanksgiving.

At any rate, here’s a flashback to the seasonal posts I wrote last year, one about five things I was grateful for as a freelance writer (they all still hold true!) and a list of recommended Thanksgiving reading.

Isherwood intended for these six autofiction stories to contribute to a “huge episodic novel of pre-Hitler Berlin” titled The Lost. Two “Berlin Diary” segments from 1930 and 1933 bear witness to a change in tenor accompanying the rise of Nazism. Even in lighter pieces about a holiday at the Baltic coast and his friendship with a family who run a department store, menace creeps in through characters’ offhand remarks about “dirty Jews” ruining the country. The narrator, Christopher Isherwood, is a private English tutor staying in squalid boarding houses or spare rooms. His living conditions are mostly played for laughs – his landlady, Fraulein Schroeder, calls him “Herr Issyvoo” – but I was also reminded of George Orwell’s didactic realism. I had it in mind that Isherwood was homosexual; the only evidence of that here is his observation of the homoerotic tension between two young men, Otto and Peter, whom he meets on the Ruegen Island vacation, so he was still being coy in print. Famously, the longest story introduces Sally Bowles (played by Liza Minnelli in Cabaret), the lovable club singer who flits from man to man and feigns a carefree joy she doesn’t always feel. This is the second of two Berlin books; I will have to find the other and explore the rest of Isherwood’s work as I found this witty and humane, restrained but vigilant. (Little Free Library)

Isherwood intended for these six autofiction stories to contribute to a “huge episodic novel of pre-Hitler Berlin” titled The Lost. Two “Berlin Diary” segments from 1930 and 1933 bear witness to a change in tenor accompanying the rise of Nazism. Even in lighter pieces about a holiday at the Baltic coast and his friendship with a family who run a department store, menace creeps in through characters’ offhand remarks about “dirty Jews” ruining the country. The narrator, Christopher Isherwood, is a private English tutor staying in squalid boarding houses or spare rooms. His living conditions are mostly played for laughs – his landlady, Fraulein Schroeder, calls him “Herr Issyvoo” – but I was also reminded of George Orwell’s didactic realism. I had it in mind that Isherwood was homosexual; the only evidence of that here is his observation of the homoerotic tension between two young men, Otto and Peter, whom he meets on the Ruegen Island vacation, so he was still being coy in print. Famously, the longest story introduces Sally Bowles (played by Liza Minnelli in Cabaret), the lovable club singer who flits from man to man and feigns a carefree joy she doesn’t always feel. This is the second of two Berlin books; I will have to find the other and explore the rest of Isherwood’s work as I found this witty and humane, restrained but vigilant. (Little Free Library)

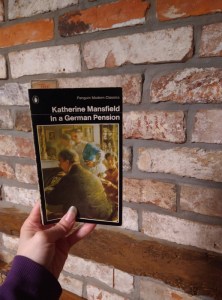

Mansfield was 19 when she composed this slim debut collection of arch sketches set in and around a Bavarian guesthouse. The narrator is a young Englishwoman traveling to take the waters for her health. A quiet but opinionated outsider (“I felt a little crushed … at the tone – placing me outside the pale – branding me as a foreigner”), she crafts pen portraits of a gluttonous baron, the fawning Herr Professor, and various meddling or air-headed fraus and frauleins. There are funny lines that rest on stereotypes (“you English … are always exposing your legs on cricket fields, and breeding dogs in your back gardens”; “a tired, pale youth … was recovering from a nervous breakdown due to much philosophy and little nourishment”) but also some alarming scenarios. One servant girl narrowly escapes being violated, while “The-Child-Who-Was-Tired” takes drastic action when another baby is added to her workload. Most of the stories are unmemorable, however. Mansfield renounced this early work as juvenile and inferior – her first publisher went bankrupt and when war broke out in Europe, sparking renewed interest in a book that pokes fun at Germans, she refused republishing rights. (Secondhand – Well-Read Books, Wigtown)

Mansfield was 19 when she composed this slim debut collection of arch sketches set in and around a Bavarian guesthouse. The narrator is a young Englishwoman traveling to take the waters for her health. A quiet but opinionated outsider (“I felt a little crushed … at the tone – placing me outside the pale – branding me as a foreigner”), she crafts pen portraits of a gluttonous baron, the fawning Herr Professor, and various meddling or air-headed fraus and frauleins. There are funny lines that rest on stereotypes (“you English … are always exposing your legs on cricket fields, and breeding dogs in your back gardens”; “a tired, pale youth … was recovering from a nervous breakdown due to much philosophy and little nourishment”) but also some alarming scenarios. One servant girl narrowly escapes being violated, while “The-Child-Who-Was-Tired” takes drastic action when another baby is added to her workload. Most of the stories are unmemorable, however. Mansfield renounced this early work as juvenile and inferior – her first publisher went bankrupt and when war broke out in Europe, sparking renewed interest in a book that pokes fun at Germans, she refused republishing rights. (Secondhand – Well-Read Books, Wigtown)

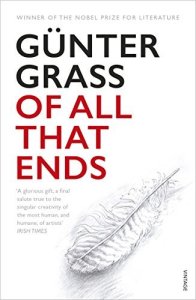

This posthumous prosimetric collection contains miniature essays, stories and poems, many of which seem autobiographical. By turns nostalgic and morbid, the pieces are very much concerned with senescence and last things. The black-and-white sketches, precise like Dürer’s but looser and more impressionistic, obsessively feature dead birds, fallen leaves, bent nails and shorn-off fingers. The speaker and his wife order wooden boxes in which their corpses will lie and store them in the cellar. One winter night they’re stolen, only to be returned the following summer. He has lost so many friends, so many teeth; there are few remaining pleasures of the flesh that can lift him out of his naturally melancholy state. Though, in Lübeck for the Christmas Fair, almonds might just help? The poetry happened to speak to me more than the prose in this volume. I’ll read longer works by Grass for future German Literature Months. My library has his first memoir, Peeling the Onion, as well as The Tin Drum, both doorstoppers. (Public library)

This posthumous prosimetric collection contains miniature essays, stories and poems, many of which seem autobiographical. By turns nostalgic and morbid, the pieces are very much concerned with senescence and last things. The black-and-white sketches, precise like Dürer’s but looser and more impressionistic, obsessively feature dead birds, fallen leaves, bent nails and shorn-off fingers. The speaker and his wife order wooden boxes in which their corpses will lie and store them in the cellar. One winter night they’re stolen, only to be returned the following summer. He has lost so many friends, so many teeth; there are few remaining pleasures of the flesh that can lift him out of his naturally melancholy state. Though, in Lübeck for the Christmas Fair, almonds might just help? The poetry happened to speak to me more than the prose in this volume. I’ll read longer works by Grass for future German Literature Months. My library has his first memoir, Peeling the Onion, as well as The Tin Drum, both doorstoppers. (Public library)

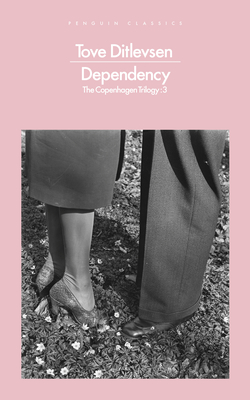

The final volume of the autobiographical Copenhagen Trilogy, after

The final volume of the autobiographical Copenhagen Trilogy, after

I had a secondhand French copy when I was in high school, always assuming I’d get to a point of fluency where I could read it in its original language. It hung around for years unread and was a victim of the final cull before my parents sold their house. Oh well! There’s always another chance with books. In this case, a copy of this plus another Gide novella turned up at the free bookshop early this year. A country pastor takes Gertrude, the blind 15-year-old niece of a deceased parishioner, into his household and, over the next two years, oversees her education as she learns Braille and plays the organ at the church. He dissuades his son Jacques from falling in love with her, but realizes that he’s been lying to himself about his own motivations. This reminded me of Ethan Frome as well as of other French classics I’ve read (

I had a secondhand French copy when I was in high school, always assuming I’d get to a point of fluency where I could read it in its original language. It hung around for years unread and was a victim of the final cull before my parents sold their house. Oh well! There’s always another chance with books. In this case, a copy of this plus another Gide novella turned up at the free bookshop early this year. A country pastor takes Gertrude, the blind 15-year-old niece of a deceased parishioner, into his household and, over the next two years, oversees her education as she learns Braille and plays the organ at the church. He dissuades his son Jacques from falling in love with her, but realizes that he’s been lying to himself about his own motivations. This reminded me of Ethan Frome as well as of other French classics I’ve read ( In fragmentary vignettes, some as short as a few lines, Belgian author Mortier chronicles his mother’s Alzheimer’s, which he describes as a “twilight zone between life and death.” His father tries to take care of her at home for as long as possible, but it’s painful for the family to see her walking back and forth between rooms, with no idea of what she’s looking for, and occasionally bursting into tears for no reason. Most distressing for Mortier is her loss of language. As if to compensate, he captures her past and present in elaborate metaphors: “Language has packed its bags and jumped over the railing of the capsizing ship, but there is also another silence … I can no longer hear the music of her soul”. He wishes he could know whether she feels hers is still a life worth living. There are many beautifully meditative passages, some of them laid out almost like poetry, but not much in the way of traditional narrative; it’s a book for reading piecemeal, when you have the fortitude.

In fragmentary vignettes, some as short as a few lines, Belgian author Mortier chronicles his mother’s Alzheimer’s, which he describes as a “twilight zone between life and death.” His father tries to take care of her at home for as long as possible, but it’s painful for the family to see her walking back and forth between rooms, with no idea of what she’s looking for, and occasionally bursting into tears for no reason. Most distressing for Mortier is her loss of language. As if to compensate, he captures her past and present in elaborate metaphors: “Language has packed its bags and jumped over the railing of the capsizing ship, but there is also another silence … I can no longer hear the music of her soul”. He wishes he could know whether she feels hers is still a life worth living. There are many beautifully meditative passages, some of them laid out almost like poetry, but not much in the way of traditional narrative; it’s a book for reading piecemeal, when you have the fortitude.  Like The Go-Between and Atonement, this is overlaid with regret about childhood caprice that has unforeseen consequences. That Sagan, like her protagonist, was only a teenager when she wrote it only makes this 98-page story the more impressive. Although her widower father has always enjoyed discreet love affairs, seventeen-year-old Cécile has basked in his undivided attention until, during a holiday on the Riviera, he announces his decision to remarry a friend of her late mother. Over the course of one summer spent discovering the pleasures of the flesh with her boyfriend, Cyril, Cécile also schemes to keep her father to herself. Dripping with sometimes uncomfortable sensuality, this was a sharp and delicious read.

Like The Go-Between and Atonement, this is overlaid with regret about childhood caprice that has unforeseen consequences. That Sagan, like her protagonist, was only a teenager when she wrote it only makes this 98-page story the more impressive. Although her widower father has always enjoyed discreet love affairs, seventeen-year-old Cécile has basked in his undivided attention until, during a holiday on the Riviera, he announces his decision to remarry a friend of her late mother. Over the course of one summer spent discovering the pleasures of the flesh with her boyfriend, Cyril, Cécile also schemes to keep her father to herself. Dripping with sometimes uncomfortable sensuality, this was a sharp and delicious read.  February 1933: 24 German captains of industry meet with Hitler to consider the advantages of a Nazi government. I loved the pomp of the opening chapter: “Through doors obsequiously held open, they stepped from their huge black sedans and paraded in single file … they doffed twenty-four felt hats and uncovered twenty-four bald pates or crowns of white hair.” As the invasion of Austria draws nearer, Vuillard recreates pivotal scenes featuring figures who will one day commit suicide or stand trial for war crimes. Reminiscent in tone and contents of HHhH,

February 1933: 24 German captains of industry meet with Hitler to consider the advantages of a Nazi government. I loved the pomp of the opening chapter: “Through doors obsequiously held open, they stepped from their huge black sedans and paraded in single file … they doffed twenty-four felt hats and uncovered twenty-four bald pates or crowns of white hair.” As the invasion of Austria draws nearer, Vuillard recreates pivotal scenes featuring figures who will one day commit suicide or stand trial for war crimes. Reminiscent in tone and contents of HHhH,

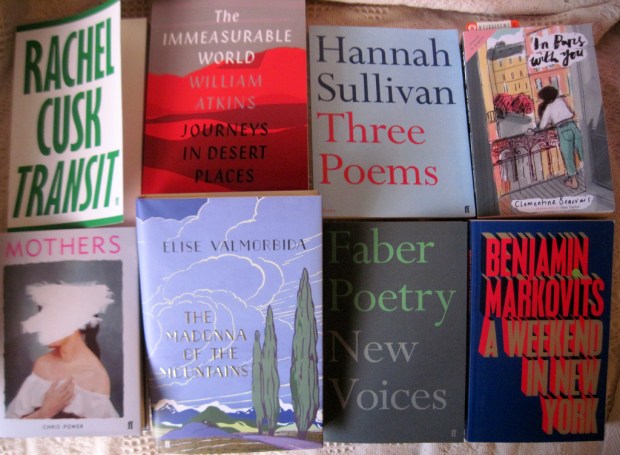

I’ve never been to an event quite like this. Publisher Faber & Faber, which will be celebrating its 90th birthday in 2019, previewed its major releases through to September. Most of the attendees seemed to be booksellers and publishing insiders. Drinks were on a buffet table at the back; books were on a buffet table along the side. Glass of champagne in hand, it was time to plunder the free books on offer. I ended up taking one of everything, with the exception of Rachel Cusk’s trilogy: I couldn’t make it through Outline and am not keen enough on her writing to get an advanced copy of Kudos, but figured I might give her another try with the middle book, Transit.

I’ve never been to an event quite like this. Publisher Faber & Faber, which will be celebrating its 90th birthday in 2019, previewed its major releases through to September. Most of the attendees seemed to be booksellers and publishing insiders. Drinks were on a buffet table at the back; books were on a buffet table along the side. Glass of champagne in hand, it was time to plunder the free books on offer. I ended up taking one of everything, with the exception of Rachel Cusk’s trilogy: I couldn’t make it through Outline and am not keen enough on her writing to get an advanced copy of Kudos, but figured I might give her another try with the middle book, Transit.

The two main characters Mears keeps coming back to in the course of the play are Bert Brocklesby, a Yorkshire preacher, and philosopher Bertrand Russell. Brocklesby refused to fight and, when he and other COs were shipped off to France anyway, resisted doing any work that supported the war effort, even peeling the potatoes that would be fed to soldiers. He and his fellow COs were beaten, placed in solitary confinement, and threatened with execution. Meanwhile, Russell and others in the No-Conscription Fellowship fought for their rights back in London. There’s a wonderful scene in the play where Russell, clad in nothing but a towel after a skinny dip, pleads with Prime Minister Asquith.

The two main characters Mears keeps coming back to in the course of the play are Bert Brocklesby, a Yorkshire preacher, and philosopher Bertrand Russell. Brocklesby refused to fight and, when he and other COs were shipped off to France anyway, resisted doing any work that supported the war effort, even peeling the potatoes that would be fed to soldiers. He and his fellow COs were beaten, placed in solitary confinement, and threatened with execution. Meanwhile, Russell and others in the No-Conscription Fellowship fought for their rights back in London. There’s a wonderful scene in the play where Russell, clad in nothing but a towel after a skinny dip, pleads with Prime Minister Asquith.