Completing the Women’s Prize Winners Reading Project and Voting

In this 25th anniversary year of the Women’s (previously Orange/Baileys) Prize, people have been encouraged to read all of the previous winners. I duly attempted to catch up on the 11 winners I hadn’t yet read, starting with Fugitive Pieces by Anne Michaels; Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and A Crime in the Neighborhood by Suzanne Berne as part of a summer reading post; and When I Lived in Modern Times by Linda Grant, Property by Valerie Martin and Larry’s Party by Carol Shields (a reread) in this post.

This left just four for me to read before voting for my all-time favorite in the web poll. I managed two as recent buddy reads but had to admit defeat on the others, giving them just the barest skim before sending them back to the library.

The Idea of Perfection by Kate Grenville (1999; 2001 prize)

(Buddy read with Laura T.; see her review here)

This is essentially an odd-couple romance, but so awkward I don’t think any of its scenes could accurately be described as a meet-cute. Harley Savage, a thrice-married middle-aged widow, works for the Applied Arts Museum in Sydney. The tall, blunt woman is in Karakarook, New South Wales to help the little town launch a heritage museum. Douglas Cheeseman is a divorced engineer tasked with tearing down a local wooden bridge and building a more suitable structure in its place. Their career trajectories are set to clash, but the novel focuses more on their personal lives. From the moment they literally bump into each other outside Douglas’ hotel, their every meeting is so embarrassing you have to blush – she saves him from some angry cows, while he tends to her after a bout of food poisoning.

This is essentially an odd-couple romance, but so awkward I don’t think any of its scenes could accurately be described as a meet-cute. Harley Savage, a thrice-married middle-aged widow, works for the Applied Arts Museum in Sydney. The tall, blunt woman is in Karakarook, New South Wales to help the little town launch a heritage museum. Douglas Cheeseman is a divorced engineer tasked with tearing down a local wooden bridge and building a more suitable structure in its place. Their career trajectories are set to clash, but the novel focuses more on their personal lives. From the moment they literally bump into each other outside Douglas’ hotel, their every meeting is so embarrassing you have to blush – she saves him from some angry cows, while he tends to her after a bout of food poisoning.

Grenville does well to make the two initially unappealing characters sympathetic, primarily by giving flashes of backstory. Douglas is the posthumous child of a war hero, but has never felt he’s a proper (macho) Australian man. In fact, he has a crippling fear of heights, which is pretty inconvenient for someone who works on tall bridges. Harley, meanwhile, is haunted by the scene of her last husband’s suicide and is also recovering from a recent heart attack.

The title is, I think, meant to refer to how the protagonists fail to live up to ideals or gender stereotypes. However, it more obviously applies to the subplot about Felicity Porcelline, a stay-at-home mother who has always sought to be flawless – a perfect pregnancy, an ageless body (“Sometimes she thought she would rather be dead than old”), the perfect marriage – but gets enmired in a dalliance with the town butcher. I was never convinced Felicity’s storyline was necessary. Without it, the book might have been cut from 400 pages to 300.

Still, this was a pleasant narrative of second chances and life’s surprises. The small-town setting reminded Laura of Olive Kitteridge in particular, and I also thought frequently of Anne Tyler and her cheerfully useless males (“There was a lot to be said for being boring, and it was something [Douglas] was good at”). But I suspect the book won’t remain vivid in my memory, especially with its vague title that doesn’t suggest the contents. I enjoyed Grenville’s writing, though, so will try her again. In my mind she’s more known for historical fiction. I have a copy of The Secret River, so will see if she lives up to that reputation.

My rating:

How to Be Both by Ali Smith (2014)

(Buddy read with Marcie of Buried in Print.)

A book of two halves, one of which I thoroughly enjoyed; the other I struggled to engage with. I remembered vaguely as I was reading it that this was published in two different versions. As it happened, my library paperback opened with the contemporary storyline.

A book of two halves, one of which I thoroughly enjoyed; the other I struggled to engage with. I remembered vaguely as I was reading it that this was published in two different versions. As it happened, my library paperback opened with the contemporary storyline.

New Year’s Day marks the start of George’s first full year without her mother, a journalist who died at age 50. Her mother’s major project was “Subvert,” which used Internet pop-ups to have art to comment on politics and vice versa. George remembers conversations with her mother about the nature of history and art, and a trip to Italy. She’s now in therapy, and has a flirty relationship with Helena (“H”), a mixed-race school friend.

Smith’s typical wordplay comes through in the book’s banter, especially in George and H’s texts. George is a whip-smart grammar pedant. Her story was, all in all, a joy to read. There is even a hint of mystery here – is it possible that her mother was being monitored by MI5? When George skips school to gaze at her mother’s favorite Francesco del Cossa painting in the National Gallery, she thinks she sees Lisa Goliard, her mother’s intense acquaintance, who said she was a bookbinder but acted more like a spy…

The second half imagines a history for Francesco del Cossa, who rises from a brick-making family to become a respected portrait and fresco painter. The artist shares outward similarities with George, such as a dead mother and homoerotic leanings. There are numerous tiny connections, too, some of which I will have missed as my attention waned. The voice felt all wrong for the time period; I sensed that Smith wasn’t fully invested in the past, so I wasn’t either. (In dual-timeline novels, I pretty much always prefer the contemporary one and am impatient to get back to it; at least in books like Unsheltered and The Liar’s Dictionary there are alternate chapters to look forward to if the historical material gets tedious.)

An intriguing idea, a very promising first half, then a drift into pretension. Or was that my failure to observe and appreciate? Smith impishly mocks: “If you notice, it changes everything about the picture.” With her format and themes, she questions accepted binaries. There are interesting points about art, grief and gender, even without the clever links across time. But had the story opened with the other Part 1, I may never have gotten anywhere.

My rating:

Skims

I made the mistake of leaving the three winners that daunted me the most stylistically – McBride, McInerney and Smith – for last. I eventually made it through the Smith, though the second half was quite the slog, but quickly realized these two were a lost cause for me.

A Girl Is a Half-formed Thing by Eimear McBride: I’d glanced at the first few pages in a shop before and found the style immediately off-putting. When I committed to this #ReadingWomen project, I diligently requested a copy from the university library even though I seriously doubted I’d have the motivation to read it. It turns out my first impression was correct: I would have to be paid much more than I’ve ever been paid for writing about a book just to get through this one. From the first paragraph on, it’s deliberately impenetrable in a sub-Joycean way. Ron Charles, the Washington Post book critic and one of my literary heroes/gurus, found the subject matter relentlessly depressing and the obfuscating style elitist. (Might it work as an audiobook? I can’t say; I’ve never listened to one.)

A Girl Is a Half-formed Thing by Eimear McBride: I’d glanced at the first few pages in a shop before and found the style immediately off-putting. When I committed to this #ReadingWomen project, I diligently requested a copy from the university library even though I seriously doubted I’d have the motivation to read it. It turns out my first impression was correct: I would have to be paid much more than I’ve ever been paid for writing about a book just to get through this one. From the first paragraph on, it’s deliberately impenetrable in a sub-Joycean way. Ron Charles, the Washington Post book critic and one of my literary heroes/gurus, found the subject matter relentlessly depressing and the obfuscating style elitist. (Might it work as an audiobook? I can’t say; I’ve never listened to one.)

The Glorious Heresies by Lisa McInerney: Not as stylistically difficult as expected, though there is mild dialect and long passages in italics (one of my reading pet peeves). But I’m not drawn to gangster stories, and after a couple of chapters didn’t feel like pushing myself through the book. I did enjoy the setup of Maureen killing an intruder with a holy stone, eliciting this confession: “I crept up behind him and hit him in the head with a religious ornament. So first I suppose God would have to forgive me for killing one of his creatures and then he’d have to forgive me for defiling one of his keepsakes.” For Anna Burns and Donal Ryan fans, perhaps?

The Glorious Heresies by Lisa McInerney: Not as stylistically difficult as expected, though there is mild dialect and long passages in italics (one of my reading pet peeves). But I’m not drawn to gangster stories, and after a couple of chapters didn’t feel like pushing myself through the book. I did enjoy the setup of Maureen killing an intruder with a holy stone, eliciting this confession: “I crept up behind him and hit him in the head with a religious ornament. So first I suppose God would have to forgive me for killing one of his creatures and then he’d have to forgive me for defiling one of his keepsakes.” For Anna Burns and Donal Ryan fans, perhaps?

It’s been many years since I’ve read some of these novels, such that all I have to go on is my vague memories and Goodreads ratings, and there are a handful there towards the bottom that I couldn’t get through at all, but I still couldn’t resist having a go at ranking the 25 winners, from best to least. My completely* objective list:

(*not at all)

Larry’s Party by Carol Shields

Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

We Need to Talk about Kevin by Lionel Shriver

An American Marriage by Tayari Jones

The Tiger’s Wife by Téa Obreht

On Beauty by Zadie Smith

Home Fire by Kamila Shamsie

A Crime in the Neighborhood by Suzanne Berne

The Road Home by Rose Tremain

When I Lived in Modern Times by Linda Grant

The Idea of Perfection by Kate Grenville

Fugitive Pieces by Anne Michaels

The Lacuna by Barbara Kingsolver

Bel Canto by Ann Patchett

May We Be Forgiven by A.M. Homes

Property by Valerie Martin

Small World by Andrea Levy

Home by Marilynne Robinson

How to Be Both by Ali Smith

The Power by Naomi Alderman

Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell

A Spell of Winter by Helen Dunmore

The Glorious Heresies by Lisa McInerney

The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller

A Girl Is a Half-formed Thing by Eimear McBride

You can see the arbitrary nature of prizes at work here: some authors I love have won for books I don’t consider their best (Adichie, Kingsolver, O’Farrell, Patchett), while some exceptional female authors have been nominated but never won (Toni Morrison, Elizabeth Strout, Anne Tyler). Each year the judges are different, and there are no detailed criteria for choosing the winner, so it will only ever be the book that five people happen to like the best.

As she came out top of the heap with what is, coincidentally, the only one of the winning novels that I have managed to reread, my vote goes to Carol Shields for Larry’s Party. (People’s memory for prize winners is notoriously short, so I predict that one of the last two years’ winners, Tayari Jones or Maggie O’Farrell, will win the public’s best of the best vote.)

You have until midnight GMT on Sunday November 1st to vote for your favorite winner at this link. That’s less than a week away now, so get voting!

Note: If you’re interested in tracking your Women’s Prize reading over the years, check out Rachel’s extremely helpful list of all the nominees. It comes in spreadsheet form for you to download and fill out. I have read 138 nominees (out of 477) and DNFed another 19 so far.

Who gets your vote?

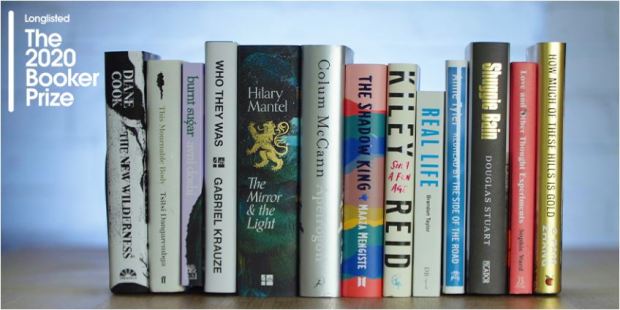

Quick Thoughts on the Booker Prize Longlist

The 13-strong 2020 Booker Prize longlist was announced this morning. Looking at friends’ Booker predictions/wish lists (Clare’s and Susan’s), I didn’t think I would be invested in this year’s prize race, yet the moment I saw the longlist I scurried to look up the titles I hadn’t heard of and to request others I realized I wanted to read after all.

In general, the list achieves a nice balance between established names and debut authors, and the gender, ethnicity and sexuality statistics are good.

(Descriptions of books not experienced are from the Goodreads blurbs.)

Read:

Only one so far and, alas, I thought it among the author’s poorest work to date:

- Redhead by the Side of the Road by Anne Tyler (Chatto & Windus) – While this novella is perfectly readable – Tyler could write sympathetic characters like Micah and his Baltimore neighbors in her sleep – it felt incomplete and inconsequential, like an early draft that needed another subplot and plenty more scenes added in before it was ready for publication. Any potential controversy (illegitimate offspring and a few post-apocalyptic imaginings) is instantly neutralized, making the story feel toothless.

DNFed earlier in the year (but what do I know?):

The Mirror & The Light by Hilary Mantel (4th Estate) – I only managed to read 80 pages or so, then skimmed to page 200 before admitting defeat. I would be totally engrossed for up to 10 pages (exposition and Cromwell one-liners), but then everything got talky or plotty and I’d skim for 20‒30 pages and set it down. I lacked the necessary singlemindedness and felt overwhelmed by the level of detail and cast of characters, so never built up momentum. Still, I can objectively recognize the prose as top-notch. But is 900 pages not a wee bit indulgent? No editor would have dared cut it…

The Mirror & The Light by Hilary Mantel (4th Estate) – I only managed to read 80 pages or so, then skimmed to page 200 before admitting defeat. I would be totally engrossed for up to 10 pages (exposition and Cromwell one-liners), but then everything got talky or plotty and I’d skim for 20‒30 pages and set it down. I lacked the necessary singlemindedness and felt overwhelmed by the level of detail and cast of characters, so never built up momentum. Still, I can objectively recognize the prose as top-notch. But is 900 pages not a wee bit indulgent? No editor would have dared cut it…- Such a Fun Age by Kiley Reid (Bloomsbury) – “In the midst of a family crisis one late evening, white blogger Alix Chamberlain calls her African American babysitter, Emira, asking her to take toddler Briar to the local market for distraction. There, the security guard accuses Emira of kidnapping Briar, and Alix’s efforts to right the situation turn out to be good intentions selfishly mismanaged.”

- How Much of These Hills Is Gold by C. Pam Zhang (Virago) – “Both epic and intimate, blending Chinese symbolism and re-imagined history with fiercely original language and storytelling, How Much of These Hills Is Gold is a haunting adventure story … An electric debut novel set against the twilight of the American gold rush, two siblings are on the run in an unforgiving landscape—trying not just to survive but to find a home.”

On the shelf to read soon:

Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart (Picador) – “The unforgettable story of young Hugh ‘Shuggie’ Bain, a sweet and lonely boy who spends his 1980s childhood in run-down public housing in Glasgow, Scotland. Thatcher’s policies have put husbands and sons out of work, and the city’s notorious drugs epidemic is waiting in the wings.” (Out on August 6th. Proof copy from publisher)

Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart (Picador) – “The unforgettable story of young Hugh ‘Shuggie’ Bain, a sweet and lonely boy who spends his 1980s childhood in run-down public housing in Glasgow, Scotland. Thatcher’s policies have put husbands and sons out of work, and the city’s notorious drugs epidemic is waiting in the wings.” (Out on August 6th. Proof copy from publisher)

Already wanted to read:

Such a Fun Age by Kiley Reid (Bloomsbury) – Yes, I’m going to try this one again! (Requested from library)

Such a Fun Age by Kiley Reid (Bloomsbury) – Yes, I’m going to try this one again! (Requested from library)- Real Life by Brandon Taylor (Daunt Books) – “An introverted young man from Alabama, black and queer, he has left behind his family without escaping the long shadows of his childhood. But over the course of a late-summer weekend, a series of confrontations with colleagues, and an unexpected encounter with an ostensibly straight, white classmate, conspire to fracture his defenses while exposing long-hidden currents of hostility and desire within their community.”

- Love and Other Thought Experiments by Sophie Ward (Corsair) – “Rachel and Eliza are hoping to have a baby. The couple spend many happy evenings together planning for the future. One night Rachel wakes up screaming and tells Eliza that an ant has crawled into her eye and is stuck there. She knows it sounds mad – but she also knows it’s true. As a scientist, Eliza won’t take Rachel’s fear seriously and they have a bitter fight. Suddenly their entire relationship is called into question.” (Requested from library)

Heard about for the first time and leapt to find:

The New Wilderness by Diane Cook (Oneworld) – “Bea, Agnes, and eighteen others volunteer to live in the Wilderness State as part of a study to see if humans can co-exist with nature … [This] explores a moving mother‒daughter relationship in a world ravaged by climate change and overpopulation.” (Out on August 13th. Requested from publisher)

The New Wilderness by Diane Cook (Oneworld) – “Bea, Agnes, and eighteen others volunteer to live in the Wilderness State as part of a study to see if humans can co-exist with nature … [This] explores a moving mother‒daughter relationship in a world ravaged by climate change and overpopulation.” (Out on August 13th. Requested from publisher)- Burnt Sugar by Avni Doshi (Hamish Hamilton) – “A searing debut novel about mothers and daughters, obsession and betrayal – for fans of Deborah Levy, Jenny Offill and Diana Evans … unpicks the slippery, choking cord of memory and myth that binds two women together, making and unmaking them endlessly.” (Out on July 30th. Requested from publisher)

Thought I didn’t want to read, but changed my mind:

Apeirogon by Colum McCann (Bloomsbury) – I’ve only read one book by McCann and have always meant to read more. But I judged this one by the title and assumed it was going to be yet another Greek myth update. (What an eejit!) “Bassam Aramin is Palestinian. Rami Elhanan is Israeli. They inhabit a world of conflict that colors every aspect of their daily lives, from the roads they are allowed to drive on, to the schools their daughters, Abir and Smadar, each attend, to the checkpoints, both physical and emotional, they must negotiate.” (Reading from library)

Apeirogon by Colum McCann (Bloomsbury) – I’ve only read one book by McCann and have always meant to read more. But I judged this one by the title and assumed it was going to be yet another Greek myth update. (What an eejit!) “Bassam Aramin is Palestinian. Rami Elhanan is Israeli. They inhabit a world of conflict that colors every aspect of their daily lives, from the roads they are allowed to drive on, to the schools their daughters, Abir and Smadar, each attend, to the checkpoints, both physical and emotional, they must negotiate.” (Reading from library)

Would read if it fell in my lap, but I’m not too bothered:

- Who They Was by Gabriel Krauze (4th Estate) – “An electrifying autobiographical British novel … This is a story of a London you won’t find in any guidebooks. This is a story about what it’s like to exist in the moment, about boys too eager to become men, growing up in the hidden war zones of big cities – and the girls trying to make it their own way.”

- The Shadow King by Maaza Mengiste (Canongate) – “A gripping novel set during Mussolini’s 1935 invasion of Ethiopia, The Shadow King takes us back to the first real conflict of World War II, casting light on the women soldiers who were left out of the historical record.” I have seen unenthusiastic reviews from friends.

Don’t plan to read:

- This Mournable Body by Tsitsi Dangarembga (Faber & Faber) – “Anxious about her prospects after leaving a stagnant job, Tambudzai finds herself living in a run-down youth hostel in downtown Harare. … at every turn in her attempt to make a life for herself, she is faced with a fresh humiliation, until the painful contrast between the future she imagined and her daily reality ultimately drives her to a breaking point.” This is the third book in a trilogy and I have seen unfavorable reviews from friends.

Of course, Hilary will win; skip the shortlist announcement in September and go ahead and give her the Triple Crown! But I always discover at least a couple of gems through the Booker longlist each year, so I’m grateful to the judges (Margaret Busby (chair), editor, literary critic and former publisher; Lee Child, author; Sameer Rahim, author and critic; Lemn Sissay, writer and broadcaster; and Emily Wilson, classicist and translator) for highlighting some exciting books that I may not have been induced to try otherwise. I will probably end up reading only half of the longlist, but may readjust my plans after the shortlist comes out.

What do you think about the longlist? Have you read anything from it? Which nominees appeal to you?

“All to Do with the Moon”: Four Books with Moon in the Title

I happened to read two books with the word moon in their titles within a couple of weeks in September, which prompted me to ransack my shelves and find two more. While these four are in completely different genres – one women’s fiction, one poetry, one memoir and one Booker-winning literary novel – they are all by women (naturally more in touch with the moon?) and all worth reading. In the weeks that I was undertaking this mini reading project, I couldn’t get Krista Detor’s song “All to Do with the Moon” out of my head (on this video, a live recording of the entire “Night Light” suite of three songs, it starts at about 6:15). She’s one of our favorite singer-songwriters, though, so this was no problem.

The Pull of the Moon by Elizabeth Berg (1996)

This is my second contemporary novel from Berg. I find her work effortlessly readable. She’s comparable to those other Elizabeths, McCracken and Strout, but also to Alice Hoffman and Anne Tyler. This one reminded me most of Tyler’s Ladder of Years in that both are about a middle-aged woman who takes a break from her marriage to figure out what she wants from life. Nan, “a fifty-year-old runaway,” takes off from her suburban Boston home and drives west, stopping at motels and cabins, eating at diners, and meeting the locals; eventually she gets as far as South Dakota. Her narration is in the form of letters to her husband, Martin, alternated with italicized passages from her journal. She reflects on everything that has made up her life – her upbringing, her marriage and other sexual encounters, raising her daughter, Ruthie – as well as on the small-town folk she meets in Iowa and Minnesota. The moon is a symbol of the femininity Nan fears she’s losing through menopause and hopes to reclaim on this journey.

This is my second contemporary novel from Berg. I find her work effortlessly readable. She’s comparable to those other Elizabeths, McCracken and Strout, but also to Alice Hoffman and Anne Tyler. This one reminded me most of Tyler’s Ladder of Years in that both are about a middle-aged woman who takes a break from her marriage to figure out what she wants from life. Nan, “a fifty-year-old runaway,” takes off from her suburban Boston home and drives west, stopping at motels and cabins, eating at diners, and meeting the locals; eventually she gets as far as South Dakota. Her narration is in the form of letters to her husband, Martin, alternated with italicized passages from her journal. She reflects on everything that has made up her life – her upbringing, her marriage and other sexual encounters, raising her daughter, Ruthie – as well as on the small-town folk she meets in Iowa and Minnesota. The moon is a symbol of the femininity Nan fears she’s losing through menopause and hopes to reclaim on this journey.

The Moon Is Almost Full by Chana Bloch (2017)

This was a lucky find in the clearance section at Blackwell’s on my Oxford day with Annabel. It’s a beautifully produced book from Autumn House, the small Pittsburgh press that released my favorite poetic work of last year: The Small Door of Your Death by Sheryl St. Germain. This was Bloch’s sixth and final book of poetry, published in the year of her death. She writes in the awareness that this cancer will be her end and doesn’t gloss over losses of function and dignity, but still finds delight in life through her family, writing and Jewish rituals: “Never forget / you were put on earth to gather joy // with melancholy hands” (from “Instructions for the Bridegroom”). A favorite poem was “The Will,” in which she imagines how the physical and intangible relics of her life will be distributed (“My plans and projects I hereby bequeath to the air / of which they were conceived. … Let the doctors pack up my heart / and keep it humming for the right customer.”).

This was a lucky find in the clearance section at Blackwell’s on my Oxford day with Annabel. It’s a beautifully produced book from Autumn House, the small Pittsburgh press that released my favorite poetic work of last year: The Small Door of Your Death by Sheryl St. Germain. This was Bloch’s sixth and final book of poetry, published in the year of her death. She writes in the awareness that this cancer will be her end and doesn’t gloss over losses of function and dignity, but still finds delight in life through her family, writing and Jewish rituals: “Never forget / you were put on earth to gather joy // with melancholy hands” (from “Instructions for the Bridegroom”). A favorite poem was “The Will,” in which she imagines how the physical and intangible relics of her life will be distributed (“My plans and projects I hereby bequeath to the air / of which they were conceived. … Let the doctors pack up my heart / and keep it humming for the right customer.”).

Off-topic note: This was typeset in Mrs Eaves, which may well be one of my favorite fonts.

To the Moon and Back: A Childhood under the Influence by Lisa Kohn (2018)

My special interest in women’s religious memoirs led me to list this among my most anticipated titles of 2018. I had it on my wish list for quite a while and then, when I saw it available for a bargain price online, snapped it up for myself. Lisa Kohn grew up in the New York City environs, the child of hippie parents she called Mimi and Danny rather than Mom and Dad. After their parents divorced, she and her brother lived in New Jersey with their mother and went into the City to visit their father, who was very lax about things like drugs. By the time Kohn was 10, her mother had gotten caught up in Reverend Moon’s Unification Church.

My special interest in women’s religious memoirs led me to list this among my most anticipated titles of 2018. I had it on my wish list for quite a while and then, when I saw it available for a bargain price online, snapped it up for myself. Lisa Kohn grew up in the New York City environs, the child of hippie parents she called Mimi and Danny rather than Mom and Dad. After their parents divorced, she and her brother lived in New Jersey with their mother and went into the City to visit their father, who was very lax about things like drugs. By the time Kohn was 10, her mother had gotten caught up in Reverend Moon’s Unification Church.

I knew next to nothing about the “Moonies,” so I found it fascinating to learn about this cult led by a South Korean reverend who let it be assumed that he was the new incarnation of Jesus Christ and the flourishing of his family on Earth would usher in God’s Kingdom. The Church became Kohn’s whole life until internal questioning set in during high school, and by the time she went to college she was adrift and into drugs instead. The book recreates scenes and dialogue well, but I found myself losing interest once the cult itself stopped being the main focus.

Readalikes: Small Fry by Lisa Brennan-Jobs and In the Days of Rain by Rebecca Stott

Moon Tiger by Penelope Lively (1987)

Seventy-six-year-old Claudia Hampton, on her deathbed in a nursing home, determines to write a history of the world – or at least, the world as she’s seen it. She’s been an author of popular history books (one of which, on Mexico, was made into a film), but she’s also been a daughter, a sister, a lover and a mother. As the book shifts between the first person and the third person, the present and the past, we learn volumes about Claudia and how her memory has preserved the layers of her personal history. There are a couple of big reveals, about her relationship with her brother Gordon and her time as a Second World War correspondent in Egypt, but what’s more impressive than these plot surprises is how Lively packs the whole sweep of a life into just 200 pages, all with such rich, wry commentary on how what we remember constructs our reality.

Seventy-six-year-old Claudia Hampton, on her deathbed in a nursing home, determines to write a history of the world – or at least, the world as she’s seen it. She’s been an author of popular history books (one of which, on Mexico, was made into a film), but she’s also been a daughter, a sister, a lover and a mother. As the book shifts between the first person and the third person, the present and the past, we learn volumes about Claudia and how her memory has preserved the layers of her personal history. There are a couple of big reveals, about her relationship with her brother Gordon and her time as a Second World War correspondent in Egypt, but what’s more impressive than these plot surprises is how Lively packs the whole sweep of a life into just 200 pages, all with such rich, wry commentary on how what we remember constructs our reality.

I made the fine choice to start reading this on holiday at the Jurassic coast in Dorset, which was fitting because Claudia grew up in Dorset and uses ammonites and rock strata as recurring metaphors. This won a well-deserved Booker Prize and is the best of the five Lively books I’ve read. I wasn’t particularly taken with the first couple I read by her, so I’m glad I tried again this year (with Heat Wave and then this). It’s just a shame that the copy I found in the free bookshop where I volunteer has such a dreadfully inappropriate cover, making it look like contemporary chick lit rather than serious literature.

Some favorite lines:

“Argument, of course, is the whole point of history. Disagreement; my word against yours; this evidence against that. If there were such a thing as absolute truth the debate would lose its lustre. I, for one, would no longer be interested.”

“In life as in history the unexpected lies waiting, grinning from around corners. Only with hindsight are we wise about cause and effect.”

“Once it is all written down we know what really happened.”

A note on the title: From the context, it seems that a moon tiger was a special inflammatory device, maybe like a citronella candle, used to repel mosquitoes and other insects.

Other ‘Moon’ books I have happened to review:

Other ‘Moon’ books I have happened to review:

Crossing the Moon by Paulette Bates Alden

The Moon and Sixpence by W. Somerset Maugham

This Year’s Summer-Themed Reading: Lippman, Lively, Nicholls & More

Sun, warmth and rival feelings of endlessness and evanescence: here were three reads that were perfect fits for the summer setting.

Sunburn by Laura Lippman (2018)

While on a beach vacation in 1995, a woman walks away from her husband and daughter and into a new life as an unattached waitress in Belleville, Delaware. Polly has been known by many names, and this isn’t the first time she’s left a family and started over. She’s the (literal) femme fatale of this film noir-inspired piece, as bound by her secrets as is Adam Bosk, the investigator sent to trail her. He takes a job as a chef at the diner where Polly works, and falls in love with her even though he may never fully trust her. Insurance scams and arson emerge as major themes.

While on a beach vacation in 1995, a woman walks away from her husband and daughter and into a new life as an unattached waitress in Belleville, Delaware. Polly has been known by many names, and this isn’t the first time she’s left a family and started over. She’s the (literal) femme fatale of this film noir-inspired piece, as bound by her secrets as is Adam Bosk, the investigator sent to trail her. He takes a job as a chef at the diner where Polly works, and falls in love with her even though he may never fully trust her. Insurance scams and arson emerge as major themes.

I liked the fact that I recognized many of the Maryland/Delaware settings, and that the setup is a tip of the hat to Anne Tyler’s excellent Ladder of Years, which was published in the year this is set. It is a quick and enjoyable summer read that surprised me with its ending, but I generally don’t find mysteries a particularly worthwhile use of my reading time. Put it down to personal taste and/or literary snobbery.

Heat Wave by Penelope Lively (1996)

My fourth Lively book, and the most enjoyable thus far. Pauline, a freelance copyeditor (“Putting commas into a novel about unicorns”) in her fifties, has escaped from London to spend a hot summer at World’s End, the Midlands holiday cottage complex she shares with her daughter Teresa, Teresa’s husband Maurice, and their baby son Luke. Maurice is writing a history of English tourism and regularly goes back to London for meetings or receives visits from his publishers, James and Carol. Pauline, divorced from a philandering husband, recognizes the signs of Maurice’s adultery long before Teresa does, and uneasily ponders how much to hint and how much to say outright.

My fourth Lively book, and the most enjoyable thus far. Pauline, a freelance copyeditor (“Putting commas into a novel about unicorns”) in her fifties, has escaped from London to spend a hot summer at World’s End, the Midlands holiday cottage complex she shares with her daughter Teresa, Teresa’s husband Maurice, and their baby son Luke. Maurice is writing a history of English tourism and regularly goes back to London for meetings or receives visits from his publishers, James and Carol. Pauline, divorced from a philandering husband, recognizes the signs of Maurice’s adultery long before Teresa does, and uneasily ponders how much to hint and how much to say outright.

The last line of the first chapter coyly promises an “agreeable summer of industry and companionship,” but the increasing atmospheric threats (drought or storms; combine harvesters coming ever nearer) match the tensions in the household. I expected this to be one of those subtle relationship studies where ultimately nothing happens. That’s not the case, though; if you’ve been paying good attention to the foreshadowing you’ll see that the ending has been on the cards.

I loved the city versus country setup of the novel, especially the almost Van Gogh-like descriptions of the blue sky and the golden wheat, and recognized myself in Pauline’s freelancer routines. Her friendships with bookseller Hugh and her client, novelist Chris Rogers, might be inconsequential to the plot but give Pauline a life wider than the confines of the cottage, and the frequent flashbacks to her marriage to Harry show what she had to overcome to earn a life of her own.

This was a compulsive read that was perfect for reading during the hottest week of our English summer. I’d recommend it to fans of Tessa Hadley, Susan Hill and Polly Sansom.

Sweet Sorrow by David Nicholls (2019)

The title is a snippet from Romeo and Juliet, which provides the setup and subject matter for this novel about first love during the golden summer of 1997, when Charlie Lewis and Fran Fisher are 16. Charlie thinks he’s way too cool for the thespians, but if he wants to keep seeing Fran he has to join the Full Fathom Five Theatre Co-operative for the five weeks of rehearsals leading up to performances. Besides, he doesn’t have anything better to do – besides watching his dad get drunk on the couch and scamming the petrol station where he works nights. Charlie starts off as the most robotic Benvolio imaginable, but Fran helps bring him up to scratch with her private tutoring (which is literal as well as a euphemism).

The title is a snippet from Romeo and Juliet, which provides the setup and subject matter for this novel about first love during the golden summer of 1997, when Charlie Lewis and Fran Fisher are 16. Charlie thinks he’s way too cool for the thespians, but if he wants to keep seeing Fran he has to join the Full Fathom Five Theatre Co-operative for the five weeks of rehearsals leading up to performances. Besides, he doesn’t have anything better to do – besides watching his dad get drunk on the couch and scamming the petrol station where he works nights. Charlie starts off as the most robotic Benvolio imaginable, but Fran helps bring him up to scratch with her private tutoring (which is literal as well as a euphemism).

Glimpses of the present day are an opportunity for nostalgia and regret, as Charlie/Nicholls coyly insists that first love means nothing: “love is boring. Love is familiar and commonplace for anyone not taking part, and first love is just a gangling, glandular incarnation of the same. … first love wasn’t real love anyway, just a fraught and feverish, juvenile imitation of it.” I enjoyed the teenage boy perspective and the theatre company shenanigans well enough, but was bored with the endless back story about Charlie’s family: his father’s record shops went bankrupt; his mother left him for another golf club colleague and took his sister; he and his depressed father are slobby roommates subsisting on takeaways and booze; blah blah blah.

It’s possible that had I read or seen R&J more recently, I would have spotted some clever parallels. Honestly? I’d cut 100+ pages (it should really be closer to 300 pages than 400) and repackage this as YA fiction. If you’re looking for lite summer fare reminiscent of Rachel Joyce and, yes, One Day, this will slip down easily, but I feel like I need to get better about curating my library stack and weeding out new releases that will be readable but forgettable. I really liked Us, which explains why I was willing to take another chance on Nicholls.

Note: There is a pretty bad anachronism here: a reference to watching The Matrix, which wasn’t released until 1999 (p. 113, “Cinnamon” chapter). Also a reference to Hobby Lobby, which as far as I know doesn’t exist in the UK (here it’s Hobbycraft) (p. 205, “Masks” chapter). I guess someone jumped the gun trying to get this ready for its U.S. release.

Favorite summery passage: “This summer’s a bastard, isn’t it? Sun comes out, sky’s blue if you’re lucky and suddenly there are all these preconceived ideas of what you should be doing, lying on a beach or jumping off a rope swing into the river or having a picnic with all your amazing mates, sitting on a blanket in a meadow and eating strawberries and laughing in that mad way, like in the adverts. It’s never like that, it’s just six weeks of feeling like you’re in the wrong place … and you’re missing out. That’s why summer’s so sad – because you’re meant to be so happy. Personally, I can’t wait to get my tights back on, turn the central heating up. At least in winter you’re allowed to be miserable” (Fran)

Plus a couple of skims:

The Sun Does Shine: How I Found Life and Freedom on Death Row by Anthony Ray Hinton with Lara Love Hardin (2018)

I’d heard about Hinton’s case: he spent nearly 30 years on death row in Alabama for crimes he didn’t commit. In 1985 he was convicted of two counts of robbery and murder, even though he’d been working in a locked warehouse 15 miles away at the time the restaurant managers were shot. His mother’s gun served as the chief piece of evidence, even though it didn’t match the bullets found at the crime scenes. “My only crime was … being born black in Alabama,” Hinton concludes. He was a convenient fall guy, and his every appeal failed until Bryan Stevenson of the Equal Justice Initiative (and author of Just Mercy, which I’d like to read) took on his case.

I’d heard about Hinton’s case: he spent nearly 30 years on death row in Alabama for crimes he didn’t commit. In 1985 he was convicted of two counts of robbery and murder, even though he’d been working in a locked warehouse 15 miles away at the time the restaurant managers were shot. His mother’s gun served as the chief piece of evidence, even though it didn’t match the bullets found at the crime scenes. “My only crime was … being born black in Alabama,” Hinton concludes. He was a convenient fall guy, and his every appeal failed until Bryan Stevenson of the Equal Justice Initiative (and author of Just Mercy, which I’d like to read) took on his case.

It took another 16 years and an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, but Hinton was finally released and now speaks out whenever he can about justice for those on death row, guilty or innocent. Almost the most heartbreaking thing about the book is that his mother, who kept the faith for so many years, died in 2012 and didn’t get to see her son walk free. I love the role that literature played: Hinton started a prison book club in which the men read Go Tell It on the Mountain and To Kill a Mockingbird and discussed issues of race and injustice. Although he doesn’t say very much about his life post-prison, I did note how big of an adjustment 30 years’ worth of technology was for him.

I don’t set a lot of stock by ghostwritten or co-written books, and found the story much more interesting than the writing here (though Hardin does a fine job of recreating the way a black man from the South speaks), so I just skimmed the book for the basics. I was impressed by how Hinton avoided bitterness and, from the very beginning, chose to forgive those who falsely accused him and worked to keep him in prison. “I was afraid every single day on death row. And I also found a way to find joy every single day. I learned that fear and joy are both a choice.” The book ends with a sobering list of all those currently on death row in the United States: single-spaced, in three columns, it fills nine pages. Lord, have mercy.

The Last Supper: A Summer in Italy by Rachel Cusk (2009)

Having moved away from Bristol, Cusk and her family (a husband and two children) decided to spend a summer in Italy before deciding where to go next. They took the boat to France then drove, made a stop in Lucca, and settled into a rented house on the eastern edge of Tuscany. It proceeded to rain for 10 days. Cusk learns to speak the vernacular of football and Catholicism – but Italian eludes her: “I too feel humbled, feel childlike and impotent. It is hard to feel so primitive, so stupid.” They glory in the food, elemental and unpretentious; they try a whole spectrum of gelato flavors. And they experience as much culture as they can: “we will learn to fillet an Italian city of its artworks with the ruthless efficiency of an English aristocrat de-boning a Dover sole.” A number of these masterpieces are reproduced in the text in black and white. In the grip of a heatwave, they move on to Rome, Naples and Capri.

Having moved away from Bristol, Cusk and her family (a husband and two children) decided to spend a summer in Italy before deciding where to go next. They took the boat to France then drove, made a stop in Lucca, and settled into a rented house on the eastern edge of Tuscany. It proceeded to rain for 10 days. Cusk learns to speak the vernacular of football and Catholicism – but Italian eludes her: “I too feel humbled, feel childlike and impotent. It is hard to feel so primitive, so stupid.” They glory in the food, elemental and unpretentious; they try a whole spectrum of gelato flavors. And they experience as much culture as they can: “we will learn to fillet an Italian city of its artworks with the ruthless efficiency of an English aristocrat de-boning a Dover sole.” A number of these masterpieces are reproduced in the text in black and white. In the grip of a heatwave, they move on to Rome, Naples and Capri.

If I’d been able to get hold of this for my trip to Milan (it was on loan at the time), I might have enjoyed it enough to read the whole thing. As it is, I just had a quick skim through. Cusk can write evocatively when she wishes to (“We came here over the white Apuan mountains, leaving behind the rose-coloured light of the coast … up and up into regions of dazzling ferocity where we wound among deathly white peaks scarred with marble quarries, along glittering chasms where the road fell away into nothingness and we clung to our seats in terror”), but more often resorts to flat descriptions of where they went and what they did. I’m pretty sure Transit was a one-off and I’ll never warm to another Cusk book.

DNFs: Alas, One Summer: America, 1927 by Bill Bryson and The Go-Between by L. P. Hartley were total non-starters. Maybe some other day (make that year).

See also my 2017 and 2018 “summer” reads, all linked by the season appearing in the title.

Have you read any summer-appropriate books lately?

Fourth Blog Anniversary

I launched my blog four years ago today. Is that ages, or no time at all? Like I said last year, it feels like something I’ve been doing forever, and yet there are bloggers out there who are coming up on a decade or more of online writing about books.

By Incabell [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)%5D.

This is my 542nd post, so the statistics tell me that I’ve been keeping up an average of just over 2.5 posts a week. Although I sometimes worry about overwhelming readers with ‘too many’ posts, I keep in mind that a) no one is obliged to read everything I post, b) a frequently updated blog is a thriving blog, and c) it only matters that it’s a manageable pace for me.

In the last year or so, I’ve gotten more involved in buddy reads and monthly challenges (things like Reading Ireland Month, 20 Books of Summer, R.I.P., Margaret Atwood Reading Month, and Novellas and Nonfiction in November); I’ve continued to take part in literary prize shadow panels and attend literary events when I can. I’ve hosted the Library Checkout for nearly a year and a half now and there are a few bloggers who join in occasionally (more are always welcome!). The posts I most enjoy putting together are write-ups of my travels, and seasonal and thematic roundups, which are generally good excuses to read backlist books from my own shelves instead of getting my head turned by new releases.

Some statistics from the past year:

My four most viewed posts were:

My four most viewed posts were:

The Diary of a Bookseller by Shaun Bythell

Clock Dance by Anne Tyler: Well…

Mixed Feelings about Elena Ferrante

I got the most likes in December 2018, and the most unique visitors and comments in August.

My four favorite posts I wrote in the past year were:

My four favorite posts I wrote in the past year were:

A Trip to Wigtown, Scotland’s Book Town

Painful but Necessary: Culling Books, Etc.

Why We Sleep … And Why Can’t I Wake Up?

A President’s Day Reading Special (No Trump in Sight)

Thanks to everyone who has supported me this past year, and/or all four years, by visiting the site, commenting, re-tweeting, and so on. You’re the best!

A brother steals the main character’s object of affection in The Crow Road by Iain Banks and Sacred Country by Rose Tremain.

A brother steals the main character’s object of affection in The Crow Road by Iain Banks and Sacred Country by Rose Tremain.

It would have been Richard Adams’s 100th birthday on the 9th. That night I started rereading his classic tale of rabbits in peril, Watership Down, which was my favorite book from childhood even though I only read it the once at age nine. I’m 80 pages in and enjoying all the local place names. Who would ever have predicted that that mousy tomboy from Silver Spring, Maryland would one day live just 6.5 miles from the real Watership Down?!

It would have been Richard Adams’s 100th birthday on the 9th. That night I started rereading his classic tale of rabbits in peril, Watership Down, which was my favorite book from childhood even though I only read it the once at age nine. I’m 80 pages in and enjoying all the local place names. Who would ever have predicted that that mousy tomboy from Silver Spring, Maryland would one day live just 6.5 miles from the real Watership Down?! My husband is joining me for the Watership Down read (he’s not sure he ever read it before), and we’re also doing a buddy read of Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez. In that case, we ended up with two free copies, one from the bookshop where I volunteer and the other from The Book Thing of Baltimore, so we each have a copy on the go. Lopez’s style, like Peter Matthiessen’s, lends itself to slower, reflective reading, so I’m only two chapters in. It’s novel to journey to the Arctic, especially as we approach the summer.

My husband is joining me for the Watership Down read (he’s not sure he ever read it before), and we’re also doing a buddy read of Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez. In that case, we ended up with two free copies, one from the bookshop where I volunteer and the other from The Book Thing of Baltimore, so we each have a copy on the go. Lopez’s style, like Peter Matthiessen’s, lends itself to slower, reflective reading, so I’m only two chapters in. It’s novel to journey to the Arctic, especially as we approach the summer.

(A sad one, this) The stillbirth of a child is an element in three memoirs I’ve read within a few months, Notes to Self by Emilie Pine, Threads by William Henry Searle, and The Chronology of Water by Lidia Yuknavitch

(A sad one, this) The stillbirth of a child is an element in three memoirs I’ve read within a few months, Notes to Self by Emilie Pine, Threads by William Henry Searle, and The Chronology of Water by Lidia Yuknavitch

I’d never heard of 4chan before, but then encountered it twice in quick succession, first in So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed by Jon Ronson and then in The Unauthorised Biography of Ezra Maas by Daniel James

I’d never heard of 4chan before, but then encountered it twice in quick succession, first in So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed by Jon Ronson and then in The Unauthorised Biography of Ezra Maas by Daniel James

An inside look at the anti-abortion movement in Priestdaddy by Patricia Lockwood and Crazy for God by Frank Schaeffer

An inside look at the anti-abortion movement in Priestdaddy by Patricia Lockwood and Crazy for God by Frank Schaeffer