Tag Archives: Barack Obama

Nonfiction and Poetry Review Catch-Up: Carson, Dixon, McLaren, Sharpe

Today I’m finally writing up four review copies that came my way quite a while ago (last year in one case). A bereavement memoir about a friend lost to opiate addiction, a nature-rich poetry collection, a practical book about being part of positive movements whether led by religion or not, and an eye-opening work of cultural criticism about Black art and suffering.

The Dead Are Gods: A Memoir by Eirinie Carson (2023)

When I was back in the States in May for my sister’s nursing school graduation, I got a chance to talk to her best friend, who is a library assistant. During the never-ending reading-out of names (it was a whole-college ceremony, as opposed to the one earlier in the day just for the nursing cohort), I read Hello Beautiful on my Kindle, tucked inside the graduation program; this friend openly read a library copy of The Dead Are Gods on her lap. When I teased her that at least I kept my book hidden, like I do at church inside the hymn book, she said (re: church), “Or you could just … not go?” (On which, see the McLaren review below!)

Anyway, it was nice to see this book out and about in the world, and it reminded me to belatedly pick up my review copy once I got back. As a bereavement memoir, the book is right in my wheelhouse, though I’ve tended to gravitate towards stories of the loss of a family memoir or spouse, whereas Carson is commemorating her best friend, Larissa, who died in 2018 of a heroin overdose, age 32, and was found in the bath in her Paris flat one week later.

Anyway, it was nice to see this book out and about in the world, and it reminded me to belatedly pick up my review copy once I got back. As a bereavement memoir, the book is right in my wheelhouse, though I’ve tended to gravitate towards stories of the loss of a family memoir or spouse, whereas Carson is commemorating her best friend, Larissa, who died in 2018 of a heroin overdose, age 32, and was found in the bath in her Paris flat one week later.

Carson wrote this three years afterward, yet the feeling is still raw. Addressing Larissa as “you” for much of the book, she loops through their history in short chapters that hop around like memory does. They met as teenagers in London and bonded over being Black models and rock music fans. After their wild years, their paths started to drift apart. Carson moved to California and married and had children; Larissa relocated to Paris and, apparently, kept partying. Her dependency came as news to Carson – all the more ironic because her father, too, is a heroin addict and mostly not present in her life.

Anyone who has suffered a loss will find much that resonates here, no matter the circumstances or timing. Carson puzzles over the difficulty of making a narrative out of death and grief (“How should I remember you? Am I doing it right? Is this enough?”), of even comprehending the bare facts of permanent absence. She’s working towards understanding, and desperate to let people know about the marvel that was Larissa. Apart from in the title chapter, the language does not stand out so much as the relatable emotion. (And it’s hard to take their pet name- and typo-strewn e-mails seriously.) Still, I marked out lots of passages to save: “It is frustrating when the one person who could answer all of your many, many questions is the dead person. … Searching for meaning in the most meaningless event in our lives feels a little stupid but I still search.”

With thanks to Melville House for the proof copy for review.

A Whistling of Birds by Isobel Dixon (illus. Douglas Robertson) (2023)

Dixon was a new name for me, but the South African poet, now based in Cambridge, has published five collections. I was drawn to this latest one by its acknowledged debt to D.H. Lawrence: the title phrase comes from one of his essays, and the book as a whole is said to resemble his Birds, Beasts and Flowers, which is in its centenary year. I’m more familiar with Lawrence’s novels than his verse, but I do own his Collected Poems and was fascinated to find here echoes of his mystical interest in nature as well as his love for the landscape of New Mexico. England and South Africa are settings as well as the American Southwest.

Dixon was a new name for me, but the South African poet, now based in Cambridge, has published five collections. I was drawn to this latest one by its acknowledged debt to D.H. Lawrence: the title phrase comes from one of his essays, and the book as a whole is said to resemble his Birds, Beasts and Flowers, which is in its centenary year. I’m more familiar with Lawrence’s novels than his verse, but I do own his Collected Poems and was fascinated to find here echoes of his mystical interest in nature as well as his love for the landscape of New Mexico. England and South Africa are settings as well as the American Southwest.

Snakes, bees, bats and foxes are some of the creatures that scamper through the text. There are poems for marine life, fruit and wildflowers. You get a sense of the seasons turning, and the natural wonders to prize from each. Dixon’s poetry is formal yet playful, the structures and line and stanza lengths varying. “Tirrick” is full of wordplay relating to Arctic terns; phrases flit across the page to mimic flight in “the bats”; “Hummingbird ~” mixes Latin names with vivid descriptions: “the oil spill of God’s glory / taking wing” and “sweet-wrapper glamour scrap / hovering shadow-gloss”.

There are portraits and elegies; moments where the speaker is present versus fable-like omniscient warnings or teasing. I particularly loved “River Mother” (an ode to a pregnant crab), “The Guests” (about a “festival of frogs” after rain), the praying mantis depicted in “A Missionary in Neon Green” (“Soul on stilts, / a gog-eyed alien”), and the everyday ecstasy of “On First Spotting a Snake’s Head Fritillary.” The book is in collaboration with Scottish artist Douglas Robertson, who provided 12 black-and-white illustrations, and is a real gem.

With thanks to Nine Arches Press for the free copy for review.

Do I Stay Christian? A Guide for the Doubters, the Disappointed and the Disillusioned by Brian McLaren (2022)

McLaren is one of the important gurus in my life. This follows on closely from his previous book, Faith after Doubt, which I reviewed last year. You might think that the title question is only rhetorical and the answer is a firmly implied Yes. But what’s refreshing is that the author genuinely does not have a secret agenda. He doesn’t mind whether you continue to consider yourself Christian or not; what he does care about is inviting people into a spiritual life that includes working towards a regenerative future, the only way the human race is going to survive. And he believes that people of all faiths and none can be a part of that.

But first to address the central question: Part One is No and Part Two is Yes; each is allotted 10 chapters and roughly the same number of pages. McLaren has absolute sympathy with those who decide that they cannot in good conscience call themselves Christians. He’s not coming up with easily refuted objections, straw men, but honestly facing huge and ongoing problems like patriarchal and colonial attitudes, the condoning of violence, intellectual stagnation, ageing congregations, and corruption. From his vantage point as a former pastor, he acknowledges that today’s churches, especially of the American megachurch variety, feature significant conflicts of interest around money. He knows that Christians can be politically and morally repugnant and can oppose the very changes the world needs.

But first to address the central question: Part One is No and Part Two is Yes; each is allotted 10 chapters and roughly the same number of pages. McLaren has absolute sympathy with those who decide that they cannot in good conscience call themselves Christians. He’s not coming up with easily refuted objections, straw men, but honestly facing huge and ongoing problems like patriarchal and colonial attitudes, the condoning of violence, intellectual stagnation, ageing congregations, and corruption. From his vantage point as a former pastor, he acknowledges that today’s churches, especially of the American megachurch variety, feature significant conflicts of interest around money. He knows that Christians can be politically and morally repugnant and can oppose the very changes the world needs.

And yet. He believes Christianity can still be a force for good, and it would be a shame to give up on the wealth of its (comparatively short) history and the paragon that is Jesus (whom he provocatively describes as “an indigenous man who prepared for his public ministry with a forty-day vision quest”). The arguments in this section are more emotional, whereas in the previous section they were matter-of-fact. However, McLaren poses a middle option between leaving the religion dramatically and remaining meekly; he calls it “staying defiantly.” My husband and I read this as a buddy read, and that will be an important concept for us: how can we challenge the status quo of our church, our denomination, this too often staid faith?

Part Three, “How,” offers ideas for how to build a resilient faith that prioritizes harmony with the environment and with others while sidelining economic concerns. He may not believe in literal hell, but he’s as end-times-oriented as any fire-and-brimstone preacher when he insists, “we have to prepare ourselves to live good lives of defiant joy in the midst of chaos and suffering. This can be done. It has been done by billions of our ancestors and neighbours.” He ends with a supremely practical piece of advice: ask yourself “whether your current context will allow the highest and best use of your gifts and time.” Lucid and well argued, this is a book I’d recommend to anyone questioning the value of Christianity.

With thanks to Hodder & Stoughton for the free copy for review.

Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe (2023)

This work of cultural criticism takes the form of 248 numbered micro-essays, some as short as one line and others up to a few pages. The central topics are Black art and Black suffering – specifically, how the latter is depicted. The book kept slapping me awake, because her opinions were not what I was expecting. Her responses to her 2018 visits to two landmarks in Montgomery, Alabama, the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, give a taste of her outlook. The museum draws a direct line between slavery and mass incarceration; the memorial documents all known cases of lynching, and she’s in its graveyard when a white woman comes up to her, crying and apologizing. When people ask Sharpe why she didn’t reply, she says, “she tries to hand me her sorrow … to super-add her burden to my own. It is not mine to bear.”

Many of these early notes question the purpose of reliving racial violence. For instance, Sharpe is appalled to watch a Claudia Rankine video essay that stitches together footage of beatings and murders of Black people. “Spectacle is not repair.” She later takes issue with Barack Obama singing “Amazing Grace” at the funeral of slain African American churchgoers because the song was written by a slaver. The general message I take from these instances is that one’s intentions do not matter; commemorating violence against Black people to pull at the heartstrings is not just in poor taste, but perpetuates cycles of damage.

Many of these early notes question the purpose of reliving racial violence. For instance, Sharpe is appalled to watch a Claudia Rankine video essay that stitches together footage of beatings and murders of Black people. “Spectacle is not repair.” She later takes issue with Barack Obama singing “Amazing Grace” at the funeral of slain African American churchgoers because the song was written by a slaver. The general message I take from these instances is that one’s intentions do not matter; commemorating violence against Black people to pull at the heartstrings is not just in poor taste, but perpetuates cycles of damage.

The book is a protest, strident yet calm, but also a celebration of the Black humanities and an elegy to her late mother, who prepared her to live as a confident, queer woman of colour in a white world. Sharpe decries the notion that art by BIPOC is only of sociological interest, to inform white people about “identity” – this is both a simplification and a means of othering.

Books—poetry, fiction, nonfiction, theory, memoir, biography, mysteries, plays—have always helped me locate myself, tethered me, helped me to make sense of the world and to act in it. I know that books have saved me. By which I mean that books always give me a place to land in difficult times. They show me Black worlds of making and possibility.

And she mainly credits her mother for introducing her to the literature that would sustain her: “My mother wanted me to build a life that was nourishing and Black. … My mother gifted me a love of beauty, a love of works. She gave me every Black book that she could find.” I loved the account of their Sunday afternoon teas, when they had cake and each read aloud a short piece they had memorized by the likes of Gwendolyn Brooks or Langston Hughes.

I found the straightforward autobiographical material, particularly the grief over the loss of her mother, more emotionally resonant than much of the book’s theorizing. The scholarly register can occasionally be off-putting, e.g., “I write these ordinary things to detail the everyday sonic and haptic vocabularies of living life under these brutal regimes.” The other media include letters, headlines, lists, and photographs, creating an overall collage effect. That the book occasionally made me uncomfortable is, no doubt, proof that I needed to read it.

With thanks to Daunt Books for the free copy for review.

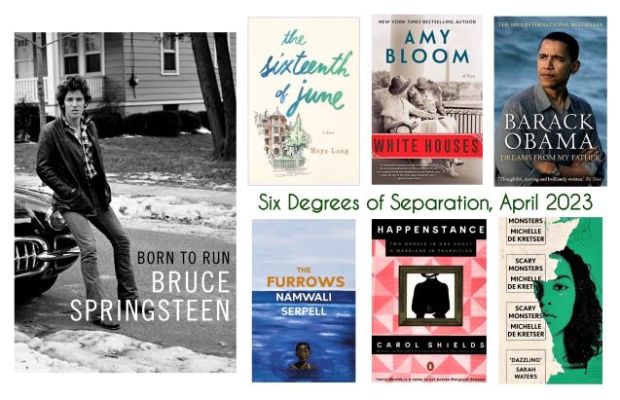

Six Degrees of Separation: From Born to Run to Scary Monsters

I take part in this meme every few months. This time we begin with Born to Run, Bruce Springsteen’s memoir. (See Kate’s opening post.)

#1 Springsteen is one of my musical blind spots – I maybe know two songs by him? – but my husband has been working up a cover of his “Streets of Philadelphia” to perform at the next open mic night at our local arts venue. A great Philadelphia-set novel I’ve read twice is The Sixteenth of June by Maya Lang.

#1 Springsteen is one of my musical blind spots – I maybe know two songs by him? – but my husband has been working up a cover of his “Streets of Philadelphia” to perform at the next open mic night at our local arts venue. A great Philadelphia-set novel I’ve read twice is The Sixteenth of June by Maya Lang.

#2 The 16th of June is, as James Joyce fans out there will know, “Bloomsday,” so I’ll move on to the only novel I’ve read so far by Amy Bloom (and one I felt ambivalent about, though I love her short stories and memoir), White Houses.

#2 The 16th of June is, as James Joyce fans out there will know, “Bloomsday,” so I’ll move on to the only novel I’ve read so far by Amy Bloom (and one I felt ambivalent about, though I love her short stories and memoir), White Houses.

#3 A recent and much-missed occupant of the White House: Barack Obama, whose Dreams from My Father didn’t quite stand up to a reread but is still a strong family memoir when it doesn’t go too deep into community organizing.

#3 A recent and much-missed occupant of the White House: Barack Obama, whose Dreams from My Father didn’t quite stand up to a reread but is still a strong family memoir when it doesn’t go too deep into community organizing.

#4 Similar to the Oprah effect, Obama publicly mentioning that he’s read and enjoyed a book is enough to make it a bestseller. On his list of favourite books of 2022 was The Furrows by Namwali Serpell, which I currently have on the go as a buddy read with Laura T.

#4 Similar to the Oprah effect, Obama publicly mentioning that he’s read and enjoyed a book is enough to make it a bestseller. On his list of favourite books of 2022 was The Furrows by Namwali Serpell, which I currently have on the go as a buddy read with Laura T.

#5 The Furrows is longlisted for the inaugural Carol Shields Prize for Fiction. In 2020 I did buddy reads of six Carol Shields novels with Marcie of Buried in Print. One of those was Happenstance, the story of a marriage told from two perspectives, the husband’s and the wife’s.

#5 The Furrows is longlisted for the inaugural Carol Shields Prize for Fiction. In 2020 I did buddy reads of six Carol Shields novels with Marcie of Buried in Print. One of those was Happenstance, the story of a marriage told from two perspectives, the husband’s and the wife’s.

#6 My Happenstance volume gives the wife’s story first and then once you’ve read to halfway you flip it over to read the husband’s story. The only other novel I know of that does that (How to Be Both does have two different versions, each of which starts with a different story line, but you don’t physically turn the book over) is Scary Monsters by Michelle de Kretser, which recently won the Rathbones Folio Prize in the fiction category. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that Ali Smith was a judge! (How astonished am I that I predicted all three category winners and the overall winner in this post from three days before the announcement?!) I know nothing else about the novel, but I have a copy out from the library and plan to read it soon.

#6 My Happenstance volume gives the wife’s story first and then once you’ve read to halfway you flip it over to read the husband’s story. The only other novel I know of that does that (How to Be Both does have two different versions, each of which starts with a different story line, but you don’t physically turn the book over) is Scary Monsters by Michelle de Kretser, which recently won the Rathbones Folio Prize in the fiction category. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that Ali Smith was a judge! (How astonished am I that I predicted all three category winners and the overall winner in this post from three days before the announcement?!) I know nothing else about the novel, but I have a copy out from the library and plan to read it soon.

Where will your chain take you? Join us for #6Degrees of Separation! (Hosted on the first Saturday of each month by Kate W. of Books Are My Favourite and Best.) Next month’s starting book is Hydra by Adriane Howell, from the Stella Prize 2023 shortlist.

Have you read any of my selections? Tempted by any you didn’t know before?

11 Days, 11 Books: 2023’s Reading So Far

I realized that, as in 2020, I happen to have finished 11 books so far this year (including a Patrick Gale again). Some of the below I’ll be reviewing in full for other themes or challenges coming up, and others have paid reviews pending that I can’t share yet, but I’ve written a little bit about each of the others. Here’s how my reading year has started off…

A children’s book

Leila and the Blue Fox by Kiran Millwood Hargrave – Similar in strategy to Hargrave’s previous book (also illustrated by her husband Tom de Freston), Julia and the Shark, one of my favourite reads of last year – both focus on the adventures of a girl who has trouble relating to her mother, a scientific researcher obsessed with a particular species. Leila, a Syrian refugee, lives with family in London and is visiting her mother in the far north of Norway. She joins her in tracking an Arctic fox on an epic journey, and helps the expedition out with social media. Migration for survival is the obvious link. There’s a lovely teal and black colour scheme, but I found this unsubtle. It crams too much together that doesn’t fit.

Leila and the Blue Fox by Kiran Millwood Hargrave – Similar in strategy to Hargrave’s previous book (also illustrated by her husband Tom de Freston), Julia and the Shark, one of my favourite reads of last year – both focus on the adventures of a girl who has trouble relating to her mother, a scientific researcher obsessed with a particular species. Leila, a Syrian refugee, lives with family in London and is visiting her mother in the far north of Norway. She joins her in tracking an Arctic fox on an epic journey, and helps the expedition out with social media. Migration for survival is the obvious link. There’s a lovely teal and black colour scheme, but I found this unsubtle. It crams too much together that doesn’t fit.

Celebrity autobiographies

A genre that pretty much never makes it onto my stacks, but I read these two despite knowing little to nothing about the authors; instead, I was drawn in by their particular stories.

A Heart that Works by Rob Delaney – Delaney is an American actor who was living in London for TV filming in 2016 when his third son, baby Henry, was diagnosed with a brain tumour. He died before the age of three. The details of disabling illness and brutal treatment could not be other than wrenching, but the tone is a delicate balance between humour, rage, and tenderness. The tribute to his son may be short in terms of number of words, yet includes so much emotional range and a lot of before and after to create a vivid picture of the wider family. People who have never picked up a bereavement memoir will warm to this one.

A Heart that Works by Rob Delaney – Delaney is an American actor who was living in London for TV filming in 2016 when his third son, baby Henry, was diagnosed with a brain tumour. He died before the age of three. The details of disabling illness and brutal treatment could not be other than wrenching, but the tone is a delicate balance between humour, rage, and tenderness. The tribute to his son may be short in terms of number of words, yet includes so much emotional range and a lot of before and after to create a vivid picture of the wider family. People who have never picked up a bereavement memoir will warm to this one.

Born a Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood by Trevor Noah – Again, I was not familiar with the author’s work in TV/comedy, but had heard good things so gave this a try. It reminded me of Barack Obama’s Dreams from My Father what with the African connection, the absent father, the close relationship with his mother, and the reflections on race and politics. I especially loved his stories of being dragged to church multiple times every Sunday. He writes a lot about her tough love, and the difficulty of leaving hood life behind once you’ve been sucked into it. The final chapter is exceptional. Noah does a fine job of creating scenes and dialogue; I’d happily read another book of his.

Born a Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood by Trevor Noah – Again, I was not familiar with the author’s work in TV/comedy, but had heard good things so gave this a try. It reminded me of Barack Obama’s Dreams from My Father what with the African connection, the absent father, the close relationship with his mother, and the reflections on race and politics. I especially loved his stories of being dragged to church multiple times every Sunday. He writes a lot about her tough love, and the difficulty of leaving hood life behind once you’ve been sucked into it. The final chapter is exceptional. Noah does a fine job of creating scenes and dialogue; I’d happily read another book of his.

Novels

Bournville by Jonathan Coe – Coe does a good line in witty state-of-the-nation novels. Patriotism versus xenophobia is the overarching dichotomy in this one, as captured through a family’s response to seven key events from English history over the last 75+ years, several of them connected with the royals. Mary Lamb, the matriarch, is an Everywoman whose happy life still harboured unfulfilled longings. Coe mixes things up by including monologues, diary entries, and so on. In some sections he cuts between the main action and a transcript of a speech, TV commentary, or set of regulations. Covid informs his prologue and the highly autobiographical final chapter, and it’s clear he’s furious with the government’s handling.

Bournville by Jonathan Coe – Coe does a good line in witty state-of-the-nation novels. Patriotism versus xenophobia is the overarching dichotomy in this one, as captured through a family’s response to seven key events from English history over the last 75+ years, several of them connected with the royals. Mary Lamb, the matriarch, is an Everywoman whose happy life still harboured unfulfilled longings. Coe mixes things up by including monologues, diary entries, and so on. In some sections he cuts between the main action and a transcript of a speech, TV commentary, or set of regulations. Covid informs his prologue and the highly autobiographical final chapter, and it’s clear he’s furious with the government’s handling.

Our Missing Hearts by Celeste Ng – Disappointing compared to her two previous novels. I’d read too much about the premise while writing a synopsis for Bookmarks magazine, so there were no surprises remaining. The political commentary, though necessary, is fairly obvious. The structure, which recounts some events first from Bird’s perspective and then from his mother Margaret Miu’s, makes parts of the second half feel redundant. Still, impossible not to find the plight of children separated from their parents heart-rending, or to disagree with the importance of drawing attention to race-based violence. It’s also appealing to think about the power of individual stories and how literature and libraries might be part of an underground protest movement.

Our Missing Hearts by Celeste Ng – Disappointing compared to her two previous novels. I’d read too much about the premise while writing a synopsis for Bookmarks magazine, so there were no surprises remaining. The political commentary, though necessary, is fairly obvious. The structure, which recounts some events first from Bird’s perspective and then from his mother Margaret Miu’s, makes parts of the second half feel redundant. Still, impossible not to find the plight of children separated from their parents heart-rending, or to disagree with the importance of drawing attention to race-based violence. It’s also appealing to think about the power of individual stories and how literature and libraries might be part of an underground protest movement.

And a memoir in miniature

Heating & Cooling: 52 Micro-Memoirs by Beth Ann Fennelly – I love memoirs-in-essays. Fennelly goes for the same minimalist approach as Abigail Thomas’s Safekeeping. Pieces range from one line to six pages and mostly pull out moments of note from the everyday of marriage, motherhood and house maintenance. I tended to get more out of the ones where she reinhabits earlier life, like “Goner” (growing up in the Catholic church); “Nine Months in Madison” (poetry fellowship in Wisconsin, running around the lake where Otis Redding died in a plane crash); and “Emulsionar,” (age 23 and in Barcelona: sexy encounter, immediately followed by scary scene). Two about grief, anticipatory for her mother (“I’ll be alone, curator of the archives”) and realized for her sister (“She threaded her arms into the sleeves of grief” – you can tell Fennelly started off as a poet), hit me hardest. Sassy and poignant.

Heating & Cooling: 52 Micro-Memoirs by Beth Ann Fennelly – I love memoirs-in-essays. Fennelly goes for the same minimalist approach as Abigail Thomas’s Safekeeping. Pieces range from one line to six pages and mostly pull out moments of note from the everyday of marriage, motherhood and house maintenance. I tended to get more out of the ones where she reinhabits earlier life, like “Goner” (growing up in the Catholic church); “Nine Months in Madison” (poetry fellowship in Wisconsin, running around the lake where Otis Redding died in a plane crash); and “Emulsionar,” (age 23 and in Barcelona: sexy encounter, immediately followed by scary scene). Two about grief, anticipatory for her mother (“I’ll be alone, curator of the archives”) and realized for her sister (“She threaded her arms into the sleeves of grief” – you can tell Fennelly started off as a poet), hit me hardest. Sassy and poignant.

The best so far? Probably Born a Crime, followed by Bournville.

Any of these you have read or would read?

November Releases: Dickens and Prince, Bratwurst Haven, Routes

Here are a few November books I read early for review, or that didn’t quite fit into the month’s other challenges – although, come to think of it, all are technically of novella length! (Come back tomorrow for a roundup of all the random novellas I’ve finished late in the month, and on Thursday for a retrospective of this year’s Novellas in November.)

Dickens and Prince: A Particular Kind of Genius by Nick Hornby

This exuberant essay, a paean to energy and imagination, draws unexpected connections between two of Hornby’s heroes. Both came from poverty, skyrocketed to fame in their twenties, were astoundingly prolific/workaholic artists, valued performance perhaps more highly than finished products, felt the industry was cheating them, had a weakness for women and died at a similar age. Biographical research shares the page with shrewd cultural commentary and glimpses of Hornby’s writing life. Whether a fan of both subjects, either or none, you’ll surely admire these geniuses’ vitality, too. (Full review forthcoming in the December 30th issue of Shelf Awareness.)

This exuberant essay, a paean to energy and imagination, draws unexpected connections between two of Hornby’s heroes. Both came from poverty, skyrocketed to fame in their twenties, were astoundingly prolific/workaholic artists, valued performance perhaps more highly than finished products, felt the industry was cheating them, had a weakness for women and died at a similar age. Biographical research shares the page with shrewd cultural commentary and glimpses of Hornby’s writing life. Whether a fan of both subjects, either or none, you’ll surely admire these geniuses’ vitality, too. (Full review forthcoming in the December 30th issue of Shelf Awareness.)

Bratwurst Haven: Stories by Rachel King

In a dozen gritty linked short stories, lovable, flawed characters navigate aging, parenthood, and relationships. Set in Colorado in the recent past, the book depicts a gentrifying area where blue-collar workers struggle to afford childcare and health insurance. As Gus, their boss at St. Anthony Sausage, withdraws their benefits and breaks in response to a recession, it’s unclear whether the business will survive. Each story covers the perspective of a different employee. The connections between tales are subtle. Overall, an endearing composite portrait of a working-class community in transition. (See my full review for Foreword.)

In a dozen gritty linked short stories, lovable, flawed characters navigate aging, parenthood, and relationships. Set in Colorado in the recent past, the book depicts a gentrifying area where blue-collar workers struggle to afford childcare and health insurance. As Gus, their boss at St. Anthony Sausage, withdraws their benefits and breaks in response to a recession, it’s unclear whether the business will survive. Each story covers the perspective of a different employee. The connections between tales are subtle. Overall, an endearing composite portrait of a working-class community in transition. (See my full review for Foreword.)

Routes by Rhiya Pau

Pau’s ancestors were part of the South Asian diaspora in East Africa, and later settled in the UK. Her debut, which won one of this year’s Eric Gregory Awards (from the Society of Authors, for a collection by a British poet under the age of 30), reflects on that stew of cultures and languages. Colours and food make up the lush metaphorical palette.

Pau’s ancestors were part of the South Asian diaspora in East Africa, and later settled in the UK. Her debut, which won one of this year’s Eric Gregory Awards (from the Society of Authors, for a collection by a British poet under the age of 30), reflects on that stew of cultures and languages. Colours and food make up the lush metaphorical palette.

When I was small, I spoke two languages.

At school: proper English, pruned and prim,

tip of the tongue taps roof of the mouth,

delicate lips, like lace frilling rims of my white

cotton socks. At home, a heady brew:

Gujarati Hindi Swahili

swim in my mouth, tie-dye my tongue

with words like bandhani.

Alongside loads of alliteration (my most adored poetic technique)—

My goddess is a mother in marigold garland

—there are delightfully unexpected turns of phrase, almost synaesthetic in their blending of the senses:

right as I worry I have forgotten the scent

of grief, I catch the first blossom of the season

and we are back circling the Spring.

~

I am a chandelier of possibility.

Besides family history and Hindu theology, current events and politics are sources of inspiration. For instance, “We Gotta Talk About S/kincare” explores the ironies and nuances of attitudes towards Black and Brown public figures, e.g., lauding Barack Obama and Kamala Harris, but former UK Home Secretary Priti Patel? “our forever – guest of honour / would deport her own mother – if she could.” I also loved the playfulness with structure: “Ode to Corelle” employs a typically solemn form for a celebration of crockery, while the yoga-themed “Salutation” snakes across two pages like a curving spine. This reminded me of poetry I’ve enjoyed by other young Asian women: Romalyn Ante, Cynthia Miller, Nina Mingya Powles and Jenny Xie. A fantastic first book.

With thanks to Arachne Press for the proof copy for review.

Any more November releases you can recommend?

Review Catch-Up: Herreros, Onyebuchi and Tookey

Quick snapshot reviews as I work through a backlog.

One each today from fiction, nonfiction and poetry: a graphic novel about the life of Georgia O’Keeffe, a personal response to Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah, and a beautiful collection of place-centric verse.

Georgia O’Keeffe by Maria Herreros (2021; 2022)

[Translated from the Spanish by Lawrence Schimel]

This is the latest in SelfMadeHero’s “Art Masters” series (I’ve also reviewed Gauguin, Munch and Vincent). Madrid-based illustrator Herreros renders O’Keeffe’s life story in an abstract style that feels in keeping with the artist’s own. The book opens in 1915 with O’Keeffe still living in her family home in Virginia and working as an art teacher. Before she ever meets Alfred Stieglitz, she is fascinated by his photography. They fall in love at a distance via a correspondence and later live together in New York City. Their relationship ebbs as she spends more and more time in New Mexico, a desert landscape that inspires many of her most famous paintings. Much of the narrative is provided by O’Keeffe’s own letters (with idiosyncrasies retained); the additional summary text is unfortunately generic, and the urge to cover many years leads to skating over long periods. Still, the erotic attention to detail and the focus on the subject’s dedication to independence made it worthwhile.

This is the latest in SelfMadeHero’s “Art Masters” series (I’ve also reviewed Gauguin, Munch and Vincent). Madrid-based illustrator Herreros renders O’Keeffe’s life story in an abstract style that feels in keeping with the artist’s own. The book opens in 1915 with O’Keeffe still living in her family home in Virginia and working as an art teacher. Before she ever meets Alfred Stieglitz, she is fascinated by his photography. They fall in love at a distance via a correspondence and later live together in New York City. Their relationship ebbs as she spends more and more time in New Mexico, a desert landscape that inspires many of her most famous paintings. Much of the narrative is provided by O’Keeffe’s own letters (with idiosyncrasies retained); the additional summary text is unfortunately generic, and the urge to cover many years leads to skating over long periods. Still, the erotic attention to detail and the focus on the subject’s dedication to independence made it worthwhile.

With thanks to SelfMadeHero for the free copy for review.

(S)kinfolk: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah by Tochi Onyebuchi (2021)

I’ve reviewed six previous releases from Fiction Advocate’s “Afterwords” series (on Blood Meridian, Fun Home, and The Year of Magical Thinking; My Struggle and Wild; and Middlesex). In these short monographs, “acclaimed writers investigate the contemporary classics,” weaving literary criticism into memoir as beloved works reverberate through their lives. Onyebuchi, a Nigerian American author of YA dystopian fiction, chose one of my favourite reads of recent years: Americanah. When he read the novel as a lawyer in training, it was the first time he sensed recognition of his own experiences in literature. He saw his immigrant mother’s situation, the collective triumph of Obama’s election, and his (re)discovery of Black beauty and spaces. Like Ifemelu: he was an outsider to African American identity and had to learn it gradually; and he makes a return trip to Nigeria at the end. I enjoyed this central thread but engaged less with asides about a 2013 visit to the West Bank (for a prisoners’ rights organization) and Frantz Fanon’s work on Algeria.

I’ve reviewed six previous releases from Fiction Advocate’s “Afterwords” series (on Blood Meridian, Fun Home, and The Year of Magical Thinking; My Struggle and Wild; and Middlesex). In these short monographs, “acclaimed writers investigate the contemporary classics,” weaving literary criticism into memoir as beloved works reverberate through their lives. Onyebuchi, a Nigerian American author of YA dystopian fiction, chose one of my favourite reads of recent years: Americanah. When he read the novel as a lawyer in training, it was the first time he sensed recognition of his own experiences in literature. He saw his immigrant mother’s situation, the collective triumph of Obama’s election, and his (re)discovery of Black beauty and spaces. Like Ifemelu: he was an outsider to African American identity and had to learn it gradually; and he makes a return trip to Nigeria at the end. I enjoyed this central thread but engaged less with asides about a 2013 visit to the West Bank (for a prisoners’ rights organization) and Frantz Fanon’s work on Algeria.

With thanks to Fiction Advocate for the free e-copy for review.

In the Quaker Hotel by Helen Tookey (2022)

Tookey’s third collection brings its variety of settings – an austere hotel, Merseyside beaches and woods, the fields and trees of Southern France (via Van Gogh’s paintings), Nova Scotia (she completed a two-week residency at the Elizabeth Bishop House in 2019) – to life as vibrantly as any novel or film could. In recent weeks I’ve taken to pulling out my e-reader as I walk home along the canal path from library volunteering, and this was a perfect companion read for the sunny waterway stroll, especially the poem “Track.” Whether in stanzas, couplets or prose paragraphs, the verse is populated by meticulous images and crystalline musings.

Tookey’s third collection brings its variety of settings – an austere hotel, Merseyside beaches and woods, the fields and trees of Southern France (via Van Gogh’s paintings), Nova Scotia (she completed a two-week residency at the Elizabeth Bishop House in 2019) – to life as vibrantly as any novel or film could. In recent weeks I’ve taken to pulling out my e-reader as I walk home along the canal path from library volunteering, and this was a perfect companion read for the sunny waterway stroll, especially the poem “Track.” Whether in stanzas, couplets or prose paragraphs, the verse is populated by meticulous images and crystalline musings.

not a loss

something like a clarifying

becoming something you can’t name

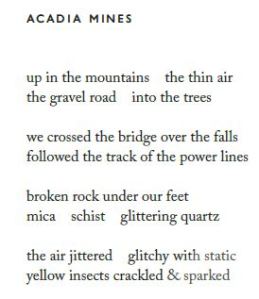

There are evanescent encounters (“Leapfrog”) and deep time (“Natural History”); playing with language (“Concession à Perpetuité”) and erasures (“Pool / Other Body”). You’ll find alliteration and ampersands (a trend in contemporary poetry?), close observation of nature, and no trace of cliché. Below are the opening stanzas of a couple of poems to give a flavour:

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free e-copy for review.

Would you be interested in reading one or more of these?

Some Bookish Pet Peeves

Happy Feast of the Inauguration!

Happy Feast of the Inauguration!

This is a feast day we made up simply because 2021 needs as many excuses for celebration as it can get. (Our next one will be in mid-February: Victoriana Fest, to celebrate the birthdays of a few of our Victorian heroes – Charles Darwin, Charles Dickens, and Abraham Lincoln. Expect traditional, stodgy foods.) Later tonight we’ll be having an all-American menu of veggie burgers, sweet potato fries, random Californian beers we found at Waitrose, and pecan pie with ice cream. And Vice President Kamala Harris’s autobiography is on hold for me at the library to pick up later this month.

Since I still don’t have any new book reviews ready (though I have now finished seven books in 2021, which is something), here’s some more filler content based on annoying book traits I’ve been reminded of recently.

Some of My Bookish Pet Peeves

Long excerpts from other books, in the text or as epigraphs

I often skip these. I am reading this book to hear from you, the author, not the various philosophers and poets you admire. I want to learn from your expertise and thought processes, not someone else’s.

Exceptions: Tim Dee’s books are good examples since he weaves in copious quotations and allusions while still being eloquent in his own right. Emily Rapp’s The Still Point of the Turning World includes a lot of quotes, especially from poems, but I was okay with that because it was true to her experience of traditional thinking failing her in the face of her son’s impending death. Her two bereavement memoirs are thus almost like commonplace books on grief.

Exceptions: Tim Dee’s books are good examples since he weaves in copious quotations and allusions while still being eloquent in his own right. Emily Rapp’s The Still Point of the Turning World includes a lot of quotes, especially from poems, but I was okay with that because it was true to her experience of traditional thinking failing her in the face of her son’s impending death. Her two bereavement memoirs are thus almost like commonplace books on grief.

Long passages in italics

I sometimes see these used to indicate flashbacks in historical fiction. They are such a pain to read. I am very likely to skim these sections, or skip them altogether.

An exception: Thus far, the secondary storyline about the mice in The Charmed Wife by Olga Grushin, delivered all in italics, has been more compelling than the main storyline.

Huge jumps forward in time

These generally feel unnatural and sudden. Surely there’s a way to avoid them? And if they are truly necessary, I’d rather they were denoted by a new section with a time/date stamp. I’m not talking about alternating storylines from different time periods, as these are usually well signaled by a change of voice, but, e.g., a chapter picking up 15 years in the future.

Not being upfront about the fact that a book is ghostwritten

I have come to expect ghostwriters for political memoirs (Barack Obama’s being a rare exception), but in the last two years I’ve also come across a botanist’s memoir and a surgeon’s memoir that were ghostwritten but not announced as such – with the former I only found out via the acknowledgments at the end, and with the latter it was hidden away in the copyright information. I’d rather the title page came right out and said “by So and So” with “Ghostwriter Name.” (Anyone know whether Kamala had a ghostwriter?)

Matte covers or dustjackets that show fingerprints

Back in 2017 I wrote a whole post on the physical book features that I love or loathe. It was a good way of eliciting strong opinions from blog readers! (For example, some people hate deckle edge, whereas I love it.)

Something that bothers other readers but doesn’t faze me at all is a lack of speech marks, or the use of alternative indicators like dashes or indented paragraphs. I’m totally used to this in literary fiction. I even kind of like it. I’m also devoted to rarer forms of narration like the second person and the first person plural that might be a turn-off for some.

[Added later]

No, or very few, paragraphs, chapters, or other section breaks

How am I supposed to know where to stop reading and put my bookmark in?!

Whom is dead

Not just in books; in written English in general. And, even if this is inevitable, it still makes me sad.

Any pet peeves making you a grumpy reader these days?

A Look Back at 2020’s Reading Projects, Including Rereads

Major bookish initiatives:

- Coordinated a Not the Wellcome Prize blog tour to celebrate 2019’s health-themed books – in case you missed it, the winner was Sinéad Gleeson for Constellations.

- Co-hosted Novellas in November with Cathy (746 Books).

- Hosted Library Checkout each month.

Reading challenges joined:

- 12 blog tours

- Six Degrees of Separation: I started participating in February and did nine posts this year

- Paul Auster Reading Week

- Reading Ireland month

- Japanese Literature Challenge

- 1920 Club

- 20 Books of Summer

- Women in Translation Month

- Robertson Davies Weekend

- Women’s Prize winners (#ReadingWomen)

- 1956 Club

- R.I.P.

- Nonfiction November

- Margaret Atwood Reading Month

This works out to one blog tour, one reading project, and one regular meme per month – manageable. I’ll probably cut back on blog tours next year, though; unless for a new release I’m really very excited about, they’re often not worth it.

Buddy reads:

Crossing to Safety with Laila (Big Reading Life)

Crossing to Safety with Laila (Big Reading Life)- 6 Carol Shields novels plus The Trick Is to Keep Breathing, Deerbrook, and How to Be Both with Marcie (Buried in Print)

- A Visit from the Goon Squad and The Idea of Perfection with Laura T.

- Mother’s Milk with Annabel

- 666 Charing Cross Road with Liz

Self-set reading challenges:

- Seasonal reading

- Classic of the Month (14 in total; it’s only thanks to Novellas in November that I averaged more than one a month)

- Doorstopper of the Month (just 3; I’d like to try to get closer to monthly in 2021)

- Wainwright Prize longlist reading

- Bellwether Prize winners (read 2, DNFed 1)

- Short stories in September (8 collections)

- Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist reading

- Thematic roundups – I’m now calling these “Three on a Theme” and have done 2 so far

- Journey through the Day with Books (3 new reviews this year):

- Zennor in Darkness by Helen Dunmore

Rise and Shine by Anna Quindlen

Rise and Shine by Anna Quindlen- [Up with the Larks by Tessa Hainsworth – DNF]

- [Shine Shine Shine by Lydia Netzer – DNF]

- Three-Martini Lunch by Suzanne Rindell – existing review

- The Shadow of the Sun by Ryszard Kapuściński – read part of

- Eventide by Kent Haruf

- Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant by Anne Tyler – existing review

- Talk before Sleep by Elizabeth Berg – existing review

- When the Lights Go Out by Carys Bray

- Journey by Moonlight by Antal Szerb

- Voyage in the Dark by Jean Rhys

- Late Nights on Air by Elizabeth Hay – existing review

- Sleeping Arrangements by Laura Shaine Cunningham

- The House of Sleep by Jonathan Coe

- Bodies in Motion and at Rest by Thomas Lynch – read but not reviewed

- Silence by Shūsaku Endō

- Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez – read part of

- The Four in a Row Challenge – I failed miserably with this one. I started an M set but got bogged down in Tales of the City by Armistead Maupin (also a bibliotherapy self-prescription for Loneliness from The Novel Cure), which I had as a bedside book for much of the year, so only managed 1.5 out of 4; I also started an H quartet but set both Tinkers and Plainsong aside. Meanwhile, Debbie joined in and completed her own 4 in a Row. Well done! I like how simple this challenge is, so I’m going to use it next year as an excuse to read more from my shelves – but I’ll be more flexible and allow lots of substitutions in case I stall with one of the four books.

Rereading

At the end of 2019, I picked out a whole shelf’s worth of books I’d been meaning to reread. I kept adding options over the year, so although I managed a respectable 16 rereads in 2020, the shelf is still overflowing!

Many of my rereads have featured on the blog over the year, but here are two more I didn’t review at the time. Both were book club selections inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement. (We held a rally and silent protest in a park in the town centre in June.)

Dreams from My Father by Barack Obama: Remember when there was a U.S. president who thought deeply, searched his soul, and wrote eloquently? I first read this memoir in 2006, when Obama was an up-and-coming Democratic politician who’d given a rousing convention speech. I remembered no details, just the general sweep of Hawaii to Chicago to Kenya. On this reread I engaged most with the first third, in which he remembers a childhood in Hawaii and Indonesia, gives pen portraits of his white mother and absentee Kenyan father, and works out what it means to be black and Christian in America. By age 12, he’d stopped advertising his mother’s race, not wanting to ingratiate himself with white people. By contrast, “To be black was to be the beneficiary of a great inheritance, a special destiny, glorious burdens that only we were strong enough to bear.” The long middle section on community organizing in Chicago nearly did me in; I had to skim past it to get to his trip to Kenya to meet his paternal relatives – “Africa had become an idea more than an actual place, a new promised land”.

Dreams from My Father by Barack Obama: Remember when there was a U.S. president who thought deeply, searched his soul, and wrote eloquently? I first read this memoir in 2006, when Obama was an up-and-coming Democratic politician who’d given a rousing convention speech. I remembered no details, just the general sweep of Hawaii to Chicago to Kenya. On this reread I engaged most with the first third, in which he remembers a childhood in Hawaii and Indonesia, gives pen portraits of his white mother and absentee Kenyan father, and works out what it means to be black and Christian in America. By age 12, he’d stopped advertising his mother’s race, not wanting to ingratiate himself with white people. By contrast, “To be black was to be the beneficiary of a great inheritance, a special destiny, glorious burdens that only we were strong enough to bear.” The long middle section on community organizing in Chicago nearly did me in; I had to skim past it to get to his trip to Kenya to meet his paternal relatives – “Africa had become an idea more than an actual place, a new promised land”.

now

now

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot: This Wellcome Book Prize winner about the use of a poor African-American woman’s cells in medical research was one of the first books to turn me onto health-themed reads. I devoured it in a few days in 2010. Once again, I was impressed at the balance between popular science and social history. Skloot conveys the basics of cell biology in a way accessible to laypeople, and uses recreated scenes and dialogue very effectively. I had forgotten the sobering details of the Lacks family experience, including incest, abuse, and STDs. Henrietta had a rural Virginia upbringing and had a child by her first cousin at age 14. At 31 she would be dead of cervical cancer, but the tissue taken from her at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins hospital became an immortal cell line. HeLa is still commonly used in medical experimentation. Consent was a major talking point at our book club Zoom meeting. Cells, once outside a body, cannot be owned, but it looks like exploitation that Henrietta’s descendants are so limited by their race and poverty. I had forgotten how Skloot’s relationship and travels with Henrietta’s unstable daughter, Deborah, takes over the book (as in the film). While I felt a little uncomfortable with how various family members are portrayed as unhinged, I still thought this was a great read.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot: This Wellcome Book Prize winner about the use of a poor African-American woman’s cells in medical research was one of the first books to turn me onto health-themed reads. I devoured it in a few days in 2010. Once again, I was impressed at the balance between popular science and social history. Skloot conveys the basics of cell biology in a way accessible to laypeople, and uses recreated scenes and dialogue very effectively. I had forgotten the sobering details of the Lacks family experience, including incest, abuse, and STDs. Henrietta had a rural Virginia upbringing and had a child by her first cousin at age 14. At 31 she would be dead of cervical cancer, but the tissue taken from her at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins hospital became an immortal cell line. HeLa is still commonly used in medical experimentation. Consent was a major talking point at our book club Zoom meeting. Cells, once outside a body, cannot be owned, but it looks like exploitation that Henrietta’s descendants are so limited by their race and poverty. I had forgotten how Skloot’s relationship and travels with Henrietta’s unstable daughter, Deborah, takes over the book (as in the film). While I felt a little uncomfortable with how various family members are portrayed as unhinged, I still thought this was a great read.  then /

then /  now

now

I had some surprising rereading DNFs. These were once favorites of mine, but for some reason I wasn’t able to recapture the magic: Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides, Everything Is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer, Gilead by Marilynne Robinson, and On Beauty by Zadie Smith. I attempted a second read of John Fowles’s postmodern Victorian pastiche, The French Lieutenant’s Woman, on a mini-break in Lyme Regis, happily reading the first third on location, but I couldn’t make myself finish once we were back home. And A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan was very disappointing a second time; it hasn’t aged well. Lastly, I’ve been stalled in Watership Down for a long time, but do intend to finish my reread.

I had some surprising rereading DNFs. These were once favorites of mine, but for some reason I wasn’t able to recapture the magic: Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides, Everything Is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer, Gilead by Marilynne Robinson, and On Beauty by Zadie Smith. I attempted a second read of John Fowles’s postmodern Victorian pastiche, The French Lieutenant’s Woman, on a mini-break in Lyme Regis, happily reading the first third on location, but I couldn’t make myself finish once we were back home. And A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan was very disappointing a second time; it hasn’t aged well. Lastly, I’ve been stalled in Watership Down for a long time, but do intend to finish my reread.

In general, voice- and style-heavy fiction did not work so well for me on rereading. Autobiographical essays by Anne Lamott and Abigail Thomas worked best, but I also succeeded at rereading some straightforward novels and short stories. Next year, I’d like to aim for a similar number of rereads, with a mixture of memoirs and fiction, including at least one novel by David Lodge. I’d also be interested in rereading earlier books by Ned Beauman and Curtis Sittenfeld if I can find them cheap secondhand.

What reading projects did you participate in this year?

Done much rereading lately?

Booker Prize 2020: Two More Shortlist Reviews and a Prediction

The 2020 Booker Prize will be announced on Thursday the 19th. (Delayed from the 17th, the date on my commemorative bookmark, so as not to be overshadowed by the release of the first volume of Barack Obama’s presidential memoirs.) After I reviewed Burnt Sugar and correctly predicted half of the shortlist in this post, I’ve managed to finish another two of the novels on the shortlist, along with two more from the longlist. As sometimes happens with prize lists – thinking also of the Women’s Prize race in 2019 – this year’s shortlist fell into rough pairs: two stark mother–daughter narratives, two novels set in Africa, and two gay coming-of-age stories.

The New Wilderness by Diane Cook

In a striking opening to a patchy novel, Bea goes off to the woods to give birth alone to a stillborn daughter. It’s such a different experience to when she birthed Agnes in a hospital eight years ago. Now, with coyotes and buzzards already circling, there’s no time for sentimentality; she turns her back on the baby and returns to the group. Bea is part of a wilderness living experiment that started out with 20 volunteers, but illness and accidents have since reduced their number.

Back in the toxic, overcrowded City, Bea was an interior decorator and her partner a professor of anthropology. Bea left to give Agnes a better chance at life; like so many other children, she had become ill from her polluted surroundings. Now she is a bright, precocious leader in the making, fully participating in the community’s daily chores. Settlement tempts them, but the Rangers enforce nomadism. Newcomers soon swell their numbers, and there are rumors of other groups, too. Is it even a wilderness anymore if so many people live in it?

Back in the toxic, overcrowded City, Bea was an interior decorator and her partner a professor of anthropology. Bea left to give Agnes a better chance at life; like so many other children, she had become ill from her polluted surroundings. Now she is a bright, precocious leader in the making, fully participating in the community’s daily chores. Settlement tempts them, but the Rangers enforce nomadism. Newcomers soon swell their numbers, and there are rumors of other groups, too. Is it even a wilderness anymore if so many people live in it?

The cycles of seasons and treks between outposts make it difficult to get a handle on time’s passing. It’s a jolt to realize Agnes is now of childbearing age. Only when motherhood is a possibility can she fully understand her own mother’s decisions, even if she determines to not repeat the history of abandonment. The blurb promised a complex mother–daughter relationship, but this element of the story felt buried under the rigor of day-to-day survival.

It is as if Cook’s primary interest was in how humans would react to being returned to primitive hunter–gatherer conditions – she did a lot of research into Native American practices, for instance, and she explores the dynamics of sex and power and how legends arise. As a child I was fascinated by Native cultures and back-to-the-land stories, so I enjoyed the details of packing lists, habits, and early rituals that form around a porcelain teacup.

But for me some nuts and bolts of storytelling were lacking here: a propulsive plot, a solid backstory, secondary characters that are worthwhile in their own right and not just stereotypes and generic roles. The appealing description induced me to overcome my usual wariness about dystopian novels, but a plodding pace meant it took me months to read. A lovely short epilogue narrated by Agnes made me wonder how much less tedious this chronicle might have been if told in the first person by Bea and Agnes in turn. I’ll try Cook’s story collection, Man V. Nature, to see if her gifts are more evident in short form.

My rating:

My thanks to Oneworld for the free copy for review.

Real Life by Brandon Taylor

Over the course of one late summer weekend, Wallace questions everything about the life he has built. As a gay African American, he has always been an outsider at the Midwestern university where he’s a graduate student in biochemistry. Though they vary in background and include several homosexuals, some partnered and some unattached, most of his friends are white, and he’s been so busy that he’s largely missed out on evening socializing by the lake – and skipped his father’s funeral (though there are other reasons for that as well).

Over the course of one late summer weekend, Wallace questions everything about the life he has built. As a gay African American, he has always been an outsider at the Midwestern university where he’s a graduate student in biochemistry. Though they vary in background and include several homosexuals, some partnered and some unattached, most of his friends are white, and he’s been so busy that he’s largely missed out on evening socializing by the lake – and skipped his father’s funeral (though there are other reasons for that as well).

Tacit prejudice comes out into the open in ugly ways in these few days. When he finds his nematode experiments sabotaged, a female colleague at his lab accuses him of misogyny, brandishing his identity as a weapon against him: “you think that you get to walk around because you’re gay and black and act like you can do no wrong.” Then, in a deliciously awkward dinner party scene, an acquaintance brings up Wallace’s underprivileged Alabama upbringing as if it explains why he’s struggling to cope in his academic career.

Meanwhile, Wallace has hooked up with a male – and erstwhile straight – friend, and though there is unwonted tenderness in this relationship, there is also a hint of menace. The linking of sexuality and violence echoes the memories of abuse from Wallace’s childhood, which tumble out in the first-person stream of consciousness of Chapter 5. Other male friends, too, are getting together or breaking apart over mismatched expectations. Kindness is possible, but built-in injustice and cruelty, whether vengeful or motiveless, too often take hold.

There are moments when Wallace seems too passive or self-pitying, but the omniscient narration emphasizes that all of the characters have hidden depths and that emotions ebb and flow. What looks like despair on Saturday night might feel like no big deal come Monday morning. I so admired how this novel was constructed: the condensed timeframe, the first and last chapters in the past tense (versus the rest in the present tense), the contrast between the cerebral and the bodily, and the thematic and linguistic nods to Virginia Woolf. A very fine debut indeed.

My rating:

I also read two more of the longlisted novels from the library:

Such a Fun Age by Kiley Reid

Such a fun book! I’d read the first chapter earlier in the year and set it aside, thinking it was too hip for me. I’m glad I decided to try again – it was a great read, so assured and contemporary. Once I got past a slightly contrived first chapter, I found it completely addictive. The laser-precision plotting and characterization reminded me of Jennifer Egan, Jonathan Franzen and Zadie Smith at their peak, but the sassy voice is all Reid’s own. There are no clear villains here; Alix Chamberlain could easily have filled that role, but I felt for her and for Kelley as much as I did for Emira. The fact that I didn’t think anyone was completely wrong shows how much nuance Reid worked in. The question of privilege is as much about money as it is about race, and these are inextricably intertwined.

Such a fun book! I’d read the first chapter earlier in the year and set it aside, thinking it was too hip for me. I’m glad I decided to try again – it was a great read, so assured and contemporary. Once I got past a slightly contrived first chapter, I found it completely addictive. The laser-precision plotting and characterization reminded me of Jennifer Egan, Jonathan Franzen and Zadie Smith at their peak, but the sassy voice is all Reid’s own. There are no clear villains here; Alix Chamberlain could easily have filled that role, but I felt for her and for Kelley as much as I did for Emira. The fact that I didn’t think anyone was completely wrong shows how much nuance Reid worked in. The question of privilege is as much about money as it is about race, and these are inextricably intertwined.

Love and Other Thought Experiments by Sophie Ward

An intriguing set of linked short stories that combine philosophy and science fiction. Rachel and Eliza are preparing to have a baby together when an ant crawls into Rachel’s eye and she falls ill. Eliza wants to believe her partner but, as a scientist, can’t affirm something that doesn’t make sense (“We don’t need to resort to the mystical to describe physical processes,” she says). Other chapters travel to Turkey, Brazil and Texas – and even into space. It takes 60+ pages to figure out, but you can trust all the threads will converge around Rachel and her son, Arthur, who becomes an astronaut. I was particularly taken by a chapter narrated by the ant (yes, really) as it explores Rachel’s brain. Each section is headed by a potted explanation of a thought experiment from philosophy. I wasn’t entirely sure what to make of the alternative future of the two final chapters. Still, I was impressed with the book’s risk-taking and verve. It’s well worth making a rare dip into sci-fi for this one.

An intriguing set of linked short stories that combine philosophy and science fiction. Rachel and Eliza are preparing to have a baby together when an ant crawls into Rachel’s eye and she falls ill. Eliza wants to believe her partner but, as a scientist, can’t affirm something that doesn’t make sense (“We don’t need to resort to the mystical to describe physical processes,” she says). Other chapters travel to Turkey, Brazil and Texas – and even into space. It takes 60+ pages to figure out, but you can trust all the threads will converge around Rachel and her son, Arthur, who becomes an astronaut. I was particularly taken by a chapter narrated by the ant (yes, really) as it explores Rachel’s brain. Each section is headed by a potted explanation of a thought experiment from philosophy. I wasn’t entirely sure what to make of the alternative future of the two final chapters. Still, I was impressed with the book’s risk-taking and verve. It’s well worth making a rare dip into sci-fi for this one.

Back in September I still thought Hilary Mantel would win the whole thing, but since her surprise omission from the shortlist I’ve assumed the prize will go to Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart. This was a DNF for me, but I’ll try it again next year in case it was just a matter of bad timing (like the Reid and The Go-Between – two books I attempted a second time this year and ended up loving). Given that it was my favorite of the ones I read, I would be delighted to see Real Life win, but I think it unlikely. My back-up prediction is The Shadow King by Maaza Mengiste, which I would consider reserving from the library if it wins.

Have you read anything from the Booker shortlist?

Which book do you expect to win?

Doorstoppers of the Month: Americanah and Deerbrook

On one of my periodic trips back to the States, I saw Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie speak at a large Maryland library soon after Americanah (2013) was published. I didn’t retain much from her talk, except that her main character, Ifemelu, was a blogger about race issues and that Black hair also played a role. I was hugely impressed with Adichie in person: stylish and well-spoken, she has calm confidence and a mellifluous voice. In the “question” (comment) time I remember many young African and African American women saying how much her book meant to them, capturing the complexities of what it’s like to be Black in America.

Ironically, I have hoarded Adichie’s work over the years since then but not read it. I did read We Should All Be Feminists from the library for Novellas in November one year, but had accumulated copies of her other five books as gifts or from neighbors or the free bookshop. (Is there a tsundoku-type term for author-specific stockpiling?) Luckily, my first taste of her fiction exceeded my high expectations and whetted my appetite to read the rest.

“You can’t write an honest novel about race in this country,” a secondary African American character declares at an evening salon Ifemelu attends. Adichie puts the lie to that statement: her slight outsider status allows her to cut through stereotypes and pretenses and get right to the heart of the issue. The novel may be seven years old (and hearkens back to the optimism of Barack Obama’s first election), but it feels utterly fresh and relevant at a time when we are newly aware of the insidiousness of racism. Again and again, I nodded in wry acknowledgment of the truth of Ifemelu’s cutting observations:

Job Vacancy in America—National Arbiter in Chief of ‘Who Is Racist’: In America, racism exists but racists are all gone. Racists belong to the past. Racists are the thin-lipped mean white people in the movies about the civil rights era. Here’s the thing: the manifestation of racism has changed but the language has not. So if you haven’t lynched somebody then you can’t be called a racist.

Through Ifemelu’s years of studying, working and blogging her way around the Eastern seaboard of the United States, Adichie explores the ways in which the experience of an African abroad differs from that of African Americans. These subtleties become especially clear through her relationships with Curt (white) and Blaine (African American), which involve a performative aspect and a slight tension that were absent with Obinze, her teenage sweetheart. Obinze, too, tries life in another country, moving to the UK illegally. Although they eventually earn financial success and good reputations – with Obinze a married property developer back in Nigeria – both characters initially have to do debasing work to get by.

Americanah is so wise about identity and perceptions, with many passages that resonated for me as an expat. When Ifemelu returns to Nigeria after 13 years, she doesn’t know if she or her country has changed: “She was no longer sure what was new in Lagos and what was new in herself … home was now a blurred place between here and there … there was something wrong with her. A hunger, a restlessness. An incomplete knowledge of herself.”

I loved Ifemelu’s close bond with her cousin, Dike, who is more like a little brother to her, and the way the narrative keeps revisiting a New Jersey hair salon where she is getting her hair braided. These scenes reminded me of Barber Shop Chronicles, a terrific play I saw with my book club last year. The prose is precise, insightful and evocative (“she would not unwrap from herself the pashmina of the wounded,” “There was something in him, lighter than ego but darker than insecurity, that needed constant buffing”).

On a sentence level as well as at a macro plot level, this was engrossing and rewarding – just what I want from a doorstopper. The question of whether Ifemelu and Obinze will get back together is one that will appeal to fans of Normal People – can these sustaining teenage relationships ever last? – but Ifemelu is such a strong, independent character that it’s merely icing on the cake. I’m moving on to her Women’s Prize winner, Half of a Yellow Sun, next.

Page count: 477 (but tiny type)

Source: Free bookshop

My rating:

Deerbrook by Harriet Martineau (1839)

This was meant to be a buddy read with Buried in Print, but I fell at the first hurdle and started skimming after 35 pages. I haven’t made it through a Victorian triple-decker in well over a decade; just since 2012, I’ve failed to get through three novels by Charles Dickens, whom I used to call my favorite author. I’m mildly disappointed in myself, but may have to accept the change in my reading tastes. In my early 20s, I loved chunky nineteenth-century novels and got my MA in Victorian Literature, but nowadays I look at one of these 500+-page classics and think, why wade through something so tortuously verbose over a matter of weeks when I could read three or more contemporary novels that will have more bearing on my life, for the same word count and time?

This was meant to be a buddy read with Buried in Print, but I fell at the first hurdle and started skimming after 35 pages. I haven’t made it through a Victorian triple-decker in well over a decade; just since 2012, I’ve failed to get through three novels by Charles Dickens, whom I used to call my favorite author. I’m mildly disappointed in myself, but may have to accept the change in my reading tastes. In my early 20s, I loved chunky nineteenth-century novels and got my MA in Victorian Literature, but nowadays I look at one of these 500+-page classics and think, why wade through something so tortuously verbose over a matter of weeks when I could read three or more contemporary novels that will have more bearing on my life, for the same word count and time?

In any case, Deerbrook is interesting from a cultural history point of view, sitting between Austen and the Brontës or George Eliot in terms of timeline, style and themes. In the fictional Midlands village of Deerbrook, the Greys and Rowlands are neighbors engaged in a polite feud while sharing a summer house and a governess. Orphaned sisters Hester and Margaret Ibbotson, 21 and 20, come to live with the Greys, their distant cousins and known dissenters. Hester got “all the beauty,” so it’s no surprise that, after a visit from a local doctor, Edward Hope, everyone is pairing him with her in their minds. I liked an early passage voicing the thoughts of Maria Young, the crippled governess (“How I love to overlook people,—to watch them acting unconsciously, and speculate for them!”), but soon tired of the matchmaking and moralizing. A world in which everyone does their duty is boring indeed.

Martineau, though, seems like a fascinating figure I’d like to read more about. She wrote a two-volume Autobiography, which I would also skim if I could find it from a library. Just her one-page bio at the front of my Virago paperback contained many astonishing sentences: “her education was interrupted by advancing deafness, requiring her to use an ear trumpet in later life”; “Her fiancé, John Hugh Worthington, having gone insane also died”; [after writing Deerbrook] “She then collapsed into bed where she was to remain for the next five years. In 1845 Harriet Martineau was dramatically cured by mesmerism,” etc.

Page count: 523 (again, tiny type)

Source: A UK secondhand bookshop 15+ years ago

Book Serendipity, April‒Early July

I call it serendipitous when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something pretty bizarre in common. Because I have so many books on the go at once (usually around 20), I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents than some. I also list these occasional reading coincidences on Twitter. The following are in rough chronological order. (January to March appeared in this post.)

- Characters named Sonny in Pew by Catherine Lacey, My Father’s Wake by Kevin Toolis, and Sacred Country by Rose Tremain.

- A double dose via Greenery via Tim Dee – while reading it I was also reading Other People’s Countries by Patrick McGuinness, whom he visits in Belgium; and A Cold Spring by Elizabeth Bishop, referenced in a footnote.

- A red thread is worn as a bracelet for its emotional or spiritual significance in The Book of Longings by Sue Monk Kidd and Plan B by Anne Lamott.

- The Library of Alexandria features in Footprints by David Farrier and The Book of Longings by Sue Monk Kidd.

- The Artist’s Way is mentioned in At Hawthorn Time by Melissa Harrison and Traveling Mercies by Anne Lamott.

- Characters sleep in a church in Pew by Catherine Lacey and Abide With Me by Elizabeth Strout. (And both novels have characters named Hilda.)

- Coins being flung away among some trees in In the Springtime of the Year by Susan Hill and The Book of Longings by Sue Monk Kidd (literally the biblical 30 pieces of silver in the Kidd, which is then used as a metaphor in the Hill).

- Rabbit-breeding projects in When the Lights Go Out by Carys Bray and Parable of the Sower by Octavia E. Butler.

- Mentions of the Great Barrier Reef in When the Lights Go Out by Carys Bray and Footprints by David Farrier.

- The same very specific fact – that Seamus Heaney’s last words, in a text to his wife, were “Noli timere” – was mentioned in Curlew Moon by Mary Colwell and Greenery by Tim Dee.

- Klondike ice cream bars appeared in both Small Victories by Anne Lamott and The Fixed Stars by Molly Wizenberg.

- The metaphor of a rising flood only the parent or the child will survive is used in both Exit West by Mohsin Hamid and What We Carry by Maya Lang.

- The necessity of turning right to save oneself in a concentration camp setting is mentioned in both Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl and Fugitive Pieces by Anne Michaels.

- An English child is raised in North Africa in Oleander, Jacaranda by Penelope Lively and The Child in Time by Ian McEwan.

- The Bristol Stool Chart appeared in both Gulp by Mary Roach and The Bad Doctor by Ian Williams.

- A Greek island setting in both Exit West by Mohsin Hamid and Fugitive Pieces by Anne Michaels (plus, earlier, in A Theatre for Dreamers by Polly Samson).

- Both Writers & Lovers by Lily King and Mother: A Memoir by Nicholas Royle mention Talking Heads within the first 20 pages.

- A trip to North Berwick in the early pages of Mother: A Memoir by Nicholas Royle, and hunting for cowrie shells on the beach – so familiar from Evie Wyld’s The Bass Rock, read the previous month. (Later, more collecting of cowrie shells in Oleander, Jacaranda by Penelope Lively.)

- Children’s authors are main characters in The Crow Road by Iain Banks and The Child in Time by Ian McEwan.

- A character is killed by a lightning strike in The Crow Road by Iain Banks and Writers & Lovers by Lily King.

- Characters named Ash in The Crow Road by Iain Banks and The Fixed Stars by Molly Wizenberg.

A brother steals the main character’s object of affection in The Crow Road by Iain Banks and Sacred Country by Rose Tremain.

A brother steals the main character’s object of affection in The Crow Road by Iain Banks and Sacred Country by Rose Tremain.

- A minor character in Parable of the Sower by Octavia E. Butler is called Richard Rohr … meanwhile, I was reading a book by Richard Rohr, The Universal Christ.

- A maternity ward setting in The Pull of the Stars by Emma Donoghue and The Bell in the Lake by Lars Mytting.

- A love triangle is a central element in Writers & Lovers by Lily King and The Bell in the Lake by Lars Mytting.