Tag Archives: Barbara Comyns

#ShortStorySeptember: Stories by Katherine Heiny, Shena Mackay and Ian McEwan

Every September I enjoy focusing on short stories, which I seem to read at a rate of only one or two collections per month in the rest of a year. This year, Lisa of ANZ Lit Lovers is hosting Short Story September as a blogger challenge for the first time. She’s encouraging people to choose individual short stories they would recommend, so I’ll be centring all of my reviews around one particular story but also giving my reaction to the collections as a whole.

“Dark Matter”

from

Single, Carefree, Mellow by Katherine Heiny (2015)

“One week in late February, Rhodes and Gildas-Joseph told Maya the same come fact, that there was a movement to reinstate Plato’s status as a planet.”

Maya is engaged to Rhodes but also sleeping with Gildas-Joseph, the director of the university library where she works. She’s one of Heiny’s typical whip-smart, exasperated protagonists, irresistibly drawn to a man or two even though they seem like priggish or ridiculous bores (witness the “come fact” above – neither can stop himself from mansplaining after sex). Having an affair means always having to keep your wits about you. Maya bumps into her boss with his wife, Adèle, at a colleague’s cocktail party and in line for the movies, and one day her fiancé’s teenage sister, Magellan (seriously, what is up with these names?!), turns up at the coffee shop where she is supposed to be meeting Gildas-Joseph. Quick, act natural. By the end, Maya knows that she must decide between the two men.

This is the middle of a trio of stories about Maya. They’re not in a row and I read the book over quite a number of months, so I was in danger of forgetting that we’d met this set of characters before. In the first, the title story, Maya has been with Rhodes for five years but is thinking of leaving him – and not just because she’s crushing on her boss. A health crisis with her dog leads her to rethink. In “Grendel’s Mother,” Maya is pregnant and hoping that she and her partner are on the same page.

This is the middle of a trio of stories about Maya. They’re not in a row and I read the book over quite a number of months, so I was in danger of forgetting that we’d met this set of characters before. In the first, the title story, Maya has been with Rhodes for five years but is thinking of leaving him – and not just because she’s crushing on her boss. A health crisis with her dog leads her to rethink. In “Grendel’s Mother,” Maya is pregnant and hoping that she and her partner are on the same page.

This triptych of linked stories is evidence that Heiny was working her way towards a novel, and I certainly prefer Standard Deviation and Early Morning Riser. However, I really liked Heiny’s 2023 story collection, Games and Rituals, which has much more variety.

I like the second person as much as anyone but three instances of “You” narration is too much. The best of these was “The Rhett Butlers,” about a teenager whose history teacher uses famous character names as aliases when checking them into motels for trysts. The cover image is from this story: “The part of your life that contains him is too sealed off, like the last slice of cake under one of those glass domes.”

Although all of these stories are entertaining and have some of the insouciance and bittersweetness of Nora Ephron’s Heartburn, they are so overwhelmingly about adultery (the main theme of at least 8 of 11) that they feel one-note.

why have an affair if not to say bad things about your spouse?

She thought that was the essence of motherhood: acting like you knew what you were talking about when you didn’t. That, and looking at people’s rashes. It was probably why people had affairs.

I would recommend any of Heiny’s other books over this one, but I wanted to read everything she’s published and I wouldn’t say my time spent on this was a waste. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

“All the Pubs in Soho”

from

Dreams of Dead Women’s Handbags by Shena Mackay (1987)

“It was his father’s vituperation about ‘those bloody pansies at Old Hollow’ that had brought Joe to the cottage on this empty summer holiday afternoon.”

It’s 1956 in Kent and Joe is only eight years old, so it’s not too surprising that, ignorant of the slang, he shows up at Arthur and Guido’s expecting to find flowers dripping red. Their place becomes his haven from a home full of crying, excreting younger siblings and a conventional father who intends to send him to a private girls’ school in the autumn. That’s right, “Joe” is Josephine, who likes to wear boys’ clothes and insists on a male name. Mackay struck me as ahead of her time (rather like Rose Tremain with Sacred Country) in honouring Joe’s chosen pronouns and letting him imagine an adult future in which he’d keep company with Arthur and Guido’s bohemian, artistic set – the former is a poet, the latter a painter – and they’d take him round ‘all the pubs in Soho.’ But in a sheltered small town where everyone has a slur ready for the men, it is not to be. Things don’t end well, but thankfully not as badly as I was hoping, and Joe has plucked up the courage to resist his father. There’s all the emotional depth and character development of a novella in this 26-page story.

I’ve had a mixed experience with Mackay, but the one novel of hers I got on well with, The Orchard on Fire, also dwells on the shattered innocence of childhood. By contrast, most of the stories in this collection are grimy ones about lonely older people – especially elderly women – reminding me of Barbara Comyns or Barbara Pym at her darkest. “Where the Carpet Ends,” about the long-term residents of a shabby hotel, recalls The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne. In “Violets and Strawberries in the Snow,” a man in a mental institution awaits a holiday visit from his daughters. “What do we do now?” he asks a fellow inmate. “We could hang ourselves in the tinsel” is the reply. It’s very black comedy indeed. The same is true of a Halloween-set story that I’ll revisit next month.

I’ve had a mixed experience with Mackay, but the one novel of hers I got on well with, The Orchard on Fire, also dwells on the shattered innocence of childhood. By contrast, most of the stories in this collection are grimy ones about lonely older people – especially elderly women – reminding me of Barbara Comyns or Barbara Pym at her darkest. “Where the Carpet Ends,” about the long-term residents of a shabby hotel, recalls The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne. In “Violets and Strawberries in the Snow,” a man in a mental institution awaits a holiday visit from his daughters. “What do we do now?” he asks a fellow inmate. “We could hang ourselves in the tinsel” is the reply. It’s very black comedy indeed. The same is true of a Halloween-set story that I’ll revisit next month.

The cover is so bad it’s good, amirite? In the title story, Susan Vigo is on her way by train to give a speech at a writers’ workshop and running through possible plots for her mystery novel in progress. “Slaves to the Mushroom” is another great one that takes place on a mushroom farm. Mackay’s settings are often surprising, her vocabulary precise, and her portraits of young people as cutting as those of the aged are pitiful. This would serve as a great introduction to her style. (Secondhand – Slightly Foxed Books, Berwick) ![]()

“The Grown-up”

from

The Daydreamer by Ian McEwan (1994)

“The following morning Peter Fortune woke from troubled dreams to find himself transformed into a giant person, an adult.”

A much better Kafka homage, this, than that forgettable novella The Cockroach that McEwan published in 2019. Every story of this linked collection features Peter, a 10-year-old with a very active imagination. Three of the stories are straightforward body-swap narratives (with his sister’s mangled doll, his cat, or his baby cousin), whereas in this one he’s not trading with anyone else but still experiencing what it’s like to be someone else. In this case, a young man falling in love for the first time. Just the previous day, at the family’s holiday cottage in Cornwall, he’d been bemoaning how boring adults are: all they want to do is sit on the beach and chat or read, when there’s so much world out there to explore and turn into a personal playground. He never wants to be one of them. Now he realizes there are different ways to enjoy life; “he stopped and turned to look at the grown-ups one more time. … He felt differently about them now. There were things they knew and liked which for him were only just appearing, like shapes in a mist. There were adventures ahead of him after all.”

Of course, I also loved “The Cat,” which Eleanor mentioned when she read my review of Matt Haig’s To Be a Cat. At the time, I’d not heard of this and couldn’t believe McEwan had written something suitable for kids! These stories were ones he read aloud to his children as he composed them. There is a hint of gruesomeness in “The Dolls,” but most are just playful. “Vanishing Cream” is a cautionary tale about wanting your family to go away. In “The Bully,” Peter turns a bully into a tentative friend. “The Baby” sees him changing his mind about an annoying relative, while “The Burglar” has him imagining himself a hero who stops the spate of neighbourhood break-ins. Events are explained away as literal dreams, daydreams or a bit of magic. This was an offbeat gem. Try it for a very different taste of McEwan! (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

Of course, I also loved “The Cat,” which Eleanor mentioned when she read my review of Matt Haig’s To Be a Cat. At the time, I’d not heard of this and couldn’t believe McEwan had written something suitable for kids! These stories were ones he read aloud to his children as he composed them. There is a hint of gruesomeness in “The Dolls,” but most are just playful. “Vanishing Cream” is a cautionary tale about wanting your family to go away. In “The Bully,” Peter turns a bully into a tentative friend. “The Baby” sees him changing his mind about an annoying relative, while “The Burglar” has him imagining himself a hero who stops the spate of neighbourhood break-ins. Events are explained away as literal dreams, daydreams or a bit of magic. This was an offbeat gem. Try it for a very different taste of McEwan! (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

Every Day Is Mother’s Day (Three on a Theme)

It’s Mother’s Day in the UK today, so I’m featuring three books about mothers and motherhood: a poetry collection, a memoir, and a novel. There are complicated emotions at play in all of these books, whether because of the loss of a child, a mother’s misbehaviour, or a combination of abuse and unfitness.

Her Birth by Rebecca Goss (2013)

Goss’s first child, Ella, died at 16 months of a rare heart condition, Severe Ebstein’s Anomaly. This collection is in three parts, the first recreating vignettes from her daughter’s short life, the purgatorial central section dwelling in the aftermath of grief, and the third summoning the courage to have another baby. “So extraordinary was your sister’s / short life, it’s hard for me to see // a future for you. I know it’s there, … yet I can’t believe // my fortune”. The close focus on physical artefacts and narrow slices of memory wards away mawkishness. The poems are sweetly affecting but never saccharine. “I kept a row of lilac-buttoned relics / in my wardrobe. Hand-knitted proof, something/ to haul my sorry lump of heart and make it blaze.” (New purchase from Bookshop UK with buyback credit)

Goss’s first child, Ella, died at 16 months of a rare heart condition, Severe Ebstein’s Anomaly. This collection is in three parts, the first recreating vignettes from her daughter’s short life, the purgatorial central section dwelling in the aftermath of grief, and the third summoning the courage to have another baby. “So extraordinary was your sister’s / short life, it’s hard for me to see // a future for you. I know it’s there, … yet I can’t believe // my fortune”. The close focus on physical artefacts and narrow slices of memory wards away mawkishness. The poems are sweetly affecting but never saccharine. “I kept a row of lilac-buttoned relics / in my wardrobe. Hand-knitted proof, something/ to haul my sorry lump of heart and make it blaze.” (New purchase from Bookshop UK with buyback credit) ![]()

How to Survive Your Mother by Jonathan Maitland (2006)

I can’t remember where I came across this in the context of recommended family memoirs, but the title and premise were enough to intrigue me. I’d not previously heard of Maitland, who at the time was known for a TV investigative reporting show called Watchdog exposing con artists. The irony: he was soon to discover that his own mother was a con artist. By chance, he met a journalist who recalled a scandal involving his parents’ old folks’ homes. Maitland toggles between flashbacks to his earlier life and fragments from his investigation, which involved archival research but mostly interviews with his estranged sister, his mother’s ex-husbands, and more.

I can’t remember where I came across this in the context of recommended family memoirs, but the title and premise were enough to intrigue me. I’d not previously heard of Maitland, who at the time was known for a TV investigative reporting show called Watchdog exposing con artists. The irony: he was soon to discover that his own mother was a con artist. By chance, he met a journalist who recalled a scandal involving his parents’ old folks’ homes. Maitland toggles between flashbacks to his earlier life and fragments from his investigation, which involved archival research but mostly interviews with his estranged sister, his mother’s ex-husbands, and more.

Bru was a larger-than-life character: Israeli, obsessed with cars and personal upkeep – she once lied to her son that she’d had “eyebrow cancer” rather than admit to having had a facelift, and prone to suicide attempts and other grand gestures, such as opening a “gay hotel” in the 1970s. It eventually emerges that she talked an old man under her care into changing his will to make her his sole beneficiary; she and Maitland’s father also borrowed money from other vulnerable elderly customers. No doubt Bru had narcissistic personality disorder. This was interesting for the psychological insight but not so much for the blow-by-blow. It might have made a better novel. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

Every Day Is Mother’s Day by Hilary Mantel (1985)

If you mostly know Mantel for her Thomas Cromwell trilogy, her debut novel, a black comedy, will come as a surprise. Two households become entangled in sordid ways in 1974. The Axons, Evelyn and her intellectually disabled adult daughter, Muriel, live around the corner from Florence Sidney, who still resides in her family home and whose brother Colin lives nearby with his wife and three children (the fourth is on the way). Colin is having an affair with Muriel’s social worker, Isabel Field. Evelyn is dismayed to realize that Muriel has, somehow, fallen pregnant.

If you mostly know Mantel for her Thomas Cromwell trilogy, her debut novel, a black comedy, will come as a surprise. Two households become entangled in sordid ways in 1974. The Axons, Evelyn and her intellectually disabled adult daughter, Muriel, live around the corner from Florence Sidney, who still resides in her family home and whose brother Colin lives nearby with his wife and three children (the fourth is on the way). Colin is having an affair with Muriel’s social worker, Isabel Field. Evelyn is dismayed to realize that Muriel has, somehow, fallen pregnant.

Everyone in this short, spiky novel has been neglected by or separated from a mother, and/or finds motherhood oppressive. The picture is bleak indeed. Colin and Florence’s mother is institutionalized; Muriel’s pregnancy is an embarrassment to be hidden; childbirth is a traumatic memory for Evelyn: “She had been left alone to scream, on a high white bed. … The parasite was straining to be away.” But you’ll find humour and delicious creepiness here, too: a dinner party so atrocious you have to laugh; Evelyn’s utter lack of manners and house that seems to be haunted by poltergeists. The offspring of Barbara Comyns and Shirley Jackson, this is also reminiscent of Muriel Spark or early Margaret Atwood.

I could see the seeds of future Mantel (Evelyn is a retired amateur medium – a precursor of the psychic in Beyond Black) but enjoyed this for its own sake. Very annoyingly, when I started reading this and saw on Goodreads that it has a sequel, I glanced at the page for the latter and there was a huge spoiler. Harrumph. Not sure I’ll read Vacant Possession, but this was strong evidence that it’s worth diving into the back catalogue of big-name authors. (Public library) ![]()

Book Serendipity, November to December 2024

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away! The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Characters who were in a chess club and debating society in high school/college in Playground by Richard Powers and Intermezzo by Sally Rooney.

- Pondering the point of a memorial and a mention of hiring mourners in Immemorial by Lauren Markham and Basket of Deplorables by Tom Rachman.

- A mention of Rachel Carson, and her The Sea Around Us in particular, in Playground by Richard Powers, while I was also reading for review Rachel Carson and the Power of Queer Love by Lida Maxwell.

- A character pretends to be asleep when someone comes into the room to check on them in Knulp by Hermann Hesse and Rental House by Weike Wang.

- A mention of where a partner puts his pistachio shells in After the Rites and Sandwiches by Kathy Pimlott and Rental House by Weike Wang.

A character who startles very easily (in the last two cases because of PTSD) in Life before Man by Margaret Atwood, A History of Sound by Ben Shattuck, and Disconnected by Eleanor Vincent.

A character who startles very easily (in the last two cases because of PTSD) in Life before Man by Margaret Atwood, A History of Sound by Ben Shattuck, and Disconnected by Eleanor Vincent.

- The husband is named Nate in Life before Man by Margaret Atwood and Rental House by Weike Wang.

- In People Collide by Isle McElroy, there’s a mention of Elizabeth reading “a popular feminist book about how men explained things to women.” The day I finished reading the novel, I started reading the book in question: Men Explain Things to Me by Rebecca Solnit.

- I learned about the “he’s-at-home” (19th-century dildo) being used by whalers’ wives on Nantucket while the husbands are away at sea through historical fiction – Daughters of Nantucket by Julie Gerstenblatt, which I read last year – and encountered the practice again through an artefact found in the present day in The History of Sound by Ben Shattuck. Awfully specific!

- A week after I finished reading Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel, it turned up in a discussion of Vancouver Island in Island by Julian Hanna.

- A Cape Cod setting in Sandwich by Catherine Newman (earlier in the year) plus The History of Sound by Ben Shattuck and Rental House by Weike Wang.

- A gay character references Mulder and Scully (of The X-Files) in the context of determining sexual preference, and there’s a female character named Kit, in The Old Haunts by Allan Radcliffe and one story of Show Don’t Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld.

- A mention of The Truman Show in the context of delusions in The Year of Living Biblically by A.J. Jacobs and You Don’t Have to Be Mad to Work Here by Benji Waterhouse.

- St. Lucia is mentioned in Beasts by Ingvild Bjerkeland, Brightly Shining by Ingvild Rishøi (two Norwegian authors named Ingvild there!), and Mudhouse Sabbath by Lauren Winner.

- A pet named Darwin: in Levels of Life by Julian Barnes it’s Sarah Bernhardt’s monkey; in Cold Kitchen by Caroline Eden it’s her beagle. Within days I met another pet beagle named Darwin in Island by Julian Hanna. (It took me a moment to realize why it’s a clever choice!)

- A character named Henrik in The Place of Tides by James Rebanks and one story of Show Don’t Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld, and a Hendrik in The Safekeep by Yael van der Wouden.

- A hat with a green ribbon in The Safekeep by Yael van der Wouden and one story of Show Don’t Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld (in which it’s an emoji).

- Romanian neighbours who speak very good English in Island by Julian Hanna and Rental House by Weike Wang.

- A scene of returning to a house one used to live in in Hyper by Agri Ismaïl, The Old Haunts by Allan Radcliffe, and one story of Show Don’t Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld.

- A woman has had three abortions in The House of Dolls by Barbara Comyns and Without Exception by Pam Houston.

- Household items keep going missing and there’s broken china in The House of Dolls by Barbara Comyns and The Safekeep by Yael van der Wouden.

- Punctuated equilibrium (a term from evolutionary biology) is used as a metaphor in Hyper by Agri Ismaïl and Men Explain Things to Me by Rebecca Solnit.

The author’s mother repeatedly asked her daughter a rhetorical question along the lines of “Do you know what I gave up to have you?” in Permission by Elissa Altman and Without Exception by Pam Houston.

The author’s mother repeatedly asked her daughter a rhetorical question along the lines of “Do you know what I gave up to have you?” in Permission by Elissa Altman and Without Exception by Pam Houston.

- The author/character looks in the mirror at the end of a long day and hardly recognizes him/herself in The Place of Tides by James Rebanks, You Don’t Have to Be Mad to Work Here by Benji Waterhouse, and Amphibian by Tyler Wetherall.

- A man is afraid to hold his boyfriend’s hand in public in another country because he’s unsure about the cultural attitudes towards homosexuality in Clinical Intimacy by Ewan Gass and Small Rain by Garth Greenwell.

- The author’s mother is a therapist/psychologist and the author her/himself is undergoing some kind of mental health treatment in Unattached by Reannon Muth and You Don’t Have to Be Mad to Work Here by Benji Waterhouse.

- A man declares that dying in one’s mid-40s is nothing to complain about in A Beginner’s Guide to Dying by Simon Boas and Small Rain by Garth Greenwell.

- A woman ponders whether her ongoing anxiety is related to the stressful circumstances of her birth in Unattached by Reannon Muth and When the World Explodes by Amy Lee Scott.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

#NovNov24 Catch-Up, I: Comyns, Figes, McEwan, Radcliffe, Thériault

Still more to finish reading and/or belatedly review this week before the Novellas in November link-up closes – another, er, nine books after this, I think! I’ll save the short nonfiction for a couple of other posts. For now I have five novellas that range from black comedy to utter heartbreak and from quotidian detail to magic realism.

The House of Dolls by Barbara Comyns (1989)

What a fantastic opening line: “Amy Doll, are you telling me that all those old girls upstairs are tarts?” Amy is a respectable widow and single mother to Hetty; no one would guess her boarding house is a brothel where gentlemen of a certain age engage the services of Berti, Evelyn, Ivy and the Señora. When a policeman starts courting Amy, she feels it’s time to address her lodgers’ profession and Hetty’s truancy. The older women disperse: move, marry or seek new employment. Sequences where Berti, who can barely boil an egg, tries to pass as a cook for a highly exacting couple, and Evelyn gets into the gin while babysitting, are hilarious. But there is pathos to the spinsters’ plight as well. “The thing that really upset [Berti] was her hair, long wisps of white with blazing red ends which she kept hidden under a scarf. The fact that she was penniless, and with no prospects, had become too terrible to contemplate.” She and Evelyn take to attending the funerals of strangers for the free buffet and booze. Comyns’ last novel (I’d only previously read Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead) is typically dark, but the wit counteracts the morbid nature. It reminded me of Beryl Bainbridge, late Barbara Pym, Lore Segal, and Muriel Spark. (Passed on by Liz – thank you! Even with the hideous cover.) [156 pages]

What a fantastic opening line: “Amy Doll, are you telling me that all those old girls upstairs are tarts?” Amy is a respectable widow and single mother to Hetty; no one would guess her boarding house is a brothel where gentlemen of a certain age engage the services of Berti, Evelyn, Ivy and the Señora. When a policeman starts courting Amy, she feels it’s time to address her lodgers’ profession and Hetty’s truancy. The older women disperse: move, marry or seek new employment. Sequences where Berti, who can barely boil an egg, tries to pass as a cook for a highly exacting couple, and Evelyn gets into the gin while babysitting, are hilarious. But there is pathos to the spinsters’ plight as well. “The thing that really upset [Berti] was her hair, long wisps of white with blazing red ends which she kept hidden under a scarf. The fact that she was penniless, and with no prospects, had become too terrible to contemplate.” She and Evelyn take to attending the funerals of strangers for the free buffet and booze. Comyns’ last novel (I’d only previously read Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead) is typically dark, but the wit counteracts the morbid nature. It reminded me of Beryl Bainbridge, late Barbara Pym, Lore Segal, and Muriel Spark. (Passed on by Liz – thank you! Even with the hideous cover.) [156 pages] ![]()

Light by Eva Figes (1983)

I read this as part of my casual ongoing project to read books from my birth year. This was recently reissued and I can see why it is considered a lost classic and was much admired by Figes’ fellow authors. A circadian novel, it presents Claude Monet and his circle of family, friends and servants at home in Giverny. The perspective shifts nimbly between characters and the prose is appropriately painterly: “The water lilies had begun to open, layer upon layer of petals folded back to the sky, revealing a variety of colour. The shadow of the willow lost depth as the sun began to climb, light filtering through a forest of long green fingers. A small white cloud, the first to be seen on this particular morning, drifted across the sky above the lily pond”. There are also neat little hints about the march of time: “‘Telephone poles are ruining my landscapes,’ grumbled Claude”. But this story takes plotlessness to a whole new level, and I lost patience far before the end, despite the low page count, and so skimmed half or more. If you are a lover of lyrical writing and can tolerate stasis, it may well be your cup of tea. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project?) [91 pages]

I read this as part of my casual ongoing project to read books from my birth year. This was recently reissued and I can see why it is considered a lost classic and was much admired by Figes’ fellow authors. A circadian novel, it presents Claude Monet and his circle of family, friends and servants at home in Giverny. The perspective shifts nimbly between characters and the prose is appropriately painterly: “The water lilies had begun to open, layer upon layer of petals folded back to the sky, revealing a variety of colour. The shadow of the willow lost depth as the sun began to climb, light filtering through a forest of long green fingers. A small white cloud, the first to be seen on this particular morning, drifted across the sky above the lily pond”. There are also neat little hints about the march of time: “‘Telephone poles are ruining my landscapes,’ grumbled Claude”. But this story takes plotlessness to a whole new level, and I lost patience far before the end, despite the low page count, and so skimmed half or more. If you are a lover of lyrical writing and can tolerate stasis, it may well be your cup of tea. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project?) [91 pages] ![]()

On Chesil Beach by Ian McEwan (2007)

“They were young, educated, and both virgins on this, their wedding night, and they lived in a time when a conversation about sexual difficulties was plainly impossible.” Another stellar opening line to what I think may be a perfect novella. Its core is the night in July 1962 when Edward and Florence attempt to consummate their marriage in a Dorset hotel, but it stretches back to cover everything we need to know about this couple – their family dynamics, how they met, what they want from life – and forward to see their lives diverge. Is love enough? “And what stood in their way? Their personalities and pasts, their ignorance and fear, timidity, squeamishness, lack of entitlement or experience or easy manners, then the tail end of a religious prohibition, their Englishness and class, and history itself. Nothing much at all.” I had forgotten the sources of trauma: Edward’s mother’s brain injury, perhaps a hint that Florence was sexually abused by her father? (But she also says things that would today make us posit asexuality.) I knew when I read this at its release that it was a superior McEwan, but it’s taken the years since – perhaps not coincidentally, the length of my own marriage – to realize just how special. It’s a maturing of the author’s vision: the tragedy is not showy and grotesque like in his early novels and stories, but quiet, hinging on the smallest of actions, or the words not said. This absolutely flayed me emotionally on a reread. (Little Free Library) [166 pages]

“They were young, educated, and both virgins on this, their wedding night, and they lived in a time when a conversation about sexual difficulties was plainly impossible.” Another stellar opening line to what I think may be a perfect novella. Its core is the night in July 1962 when Edward and Florence attempt to consummate their marriage in a Dorset hotel, but it stretches back to cover everything we need to know about this couple – their family dynamics, how they met, what they want from life – and forward to see their lives diverge. Is love enough? “And what stood in their way? Their personalities and pasts, their ignorance and fear, timidity, squeamishness, lack of entitlement or experience or easy manners, then the tail end of a religious prohibition, their Englishness and class, and history itself. Nothing much at all.” I had forgotten the sources of trauma: Edward’s mother’s brain injury, perhaps a hint that Florence was sexually abused by her father? (But she also says things that would today make us posit asexuality.) I knew when I read this at its release that it was a superior McEwan, but it’s taken the years since – perhaps not coincidentally, the length of my own marriage – to realize just how special. It’s a maturing of the author’s vision: the tragedy is not showy and grotesque like in his early novels and stories, but quiet, hinging on the smallest of actions, or the words not said. This absolutely flayed me emotionally on a reread. (Little Free Library) [166 pages] ![]()

The Old Haunts by Allan Radcliffe (2023)

I was sent this earlier in the year in a parcel containing the 2024 McKitterick Prize shortlist. It’s been instructive to observe the variety just in that set of six (and so much the more in the novels I’m assessing for the longlist now). The short, titled chapters feel almost like linked flash stories that switch between the present day and scenes from art teacher Jamie’s past. Both of his parents having recently died, Jamie and his boyfriend, a mixed-race actor named Alex, get away to remote Scotland. His parents were older when they had him; growing up in the flat above their newsagent’s shop in Edinburgh, Jamie felt the generational gap meant they couldn’t quite understand him or his art. Uni in London was his chance to come out and make supportive friends, but being honest with his parents seemed a step too far. When Alex is called away for an audition, Jamie delves deeper into his memories. Kit, their host at the cottage, has her own story. Some lovely, low-key vignettes and passages (“A smell of soaked fruit. Christmas cake. My mother liked to be organised. She was here, alive, only yesterday.”), but overall a little too soft for the grief theme to truly pierce through. [158 pages]

I was sent this earlier in the year in a parcel containing the 2024 McKitterick Prize shortlist. It’s been instructive to observe the variety just in that set of six (and so much the more in the novels I’m assessing for the longlist now). The short, titled chapters feel almost like linked flash stories that switch between the present day and scenes from art teacher Jamie’s past. Both of his parents having recently died, Jamie and his boyfriend, a mixed-race actor named Alex, get away to remote Scotland. His parents were older when they had him; growing up in the flat above their newsagent’s shop in Edinburgh, Jamie felt the generational gap meant they couldn’t quite understand him or his art. Uni in London was his chance to come out and make supportive friends, but being honest with his parents seemed a step too far. When Alex is called away for an audition, Jamie delves deeper into his memories. Kit, their host at the cottage, has her own story. Some lovely, low-key vignettes and passages (“A smell of soaked fruit. Christmas cake. My mother liked to be organised. She was here, alive, only yesterday.”), but overall a little too soft for the grief theme to truly pierce through. [158 pages] ![]()

With thanks to the Society of Authors for the free copy for review.

The Peculiar Life of a Lonely Postman by Denis Thériault (2005; 2008)

[Translated from the French by Liedewy Hawke]

{BEWARE SPOILERS} Like many, I was drawn in by the quirky title and Japan-evoking cover. To start with, it’s the engaging story of Bilodo, a Montreal postman with a naughty habit of steaming open various people’s mail. He soon becomes obsessed with the haiku exchange between a certain Gaston Grandpré and his pen pal in Guadeloupe, Ségolène. When Grandpré dies a violent death, Bilodo decides to impersonate him and take over the correspondence. He learns to write poetry – as Thériault had to, to write this – and their haiku (“the art of the snapshot, the detail”) and tanka grow increasingly erotic and take over his life, even supplanting his career. But when Ségolène offers to fly to Canada, Bilodo panics. I had two major problems with this: the exoticizing of a Black woman (why did she have to be from Guadeloupe, of all places?), and the bizarre ending, in which Bilodo, who has gradually become more like Grandpré, seems destined for his fate as well. I imagine this was supposed to be a psychological fable, but it was just a little bit silly for me, and the way it’s marketed will probably disappoint readers who are looking for either Harold Fry heart warming or cute Japanese cat/phone box adventures. (Public library) [108 pages]

{BEWARE SPOILERS} Like many, I was drawn in by the quirky title and Japan-evoking cover. To start with, it’s the engaging story of Bilodo, a Montreal postman with a naughty habit of steaming open various people’s mail. He soon becomes obsessed with the haiku exchange between a certain Gaston Grandpré and his pen pal in Guadeloupe, Ségolène. When Grandpré dies a violent death, Bilodo decides to impersonate him and take over the correspondence. He learns to write poetry – as Thériault had to, to write this – and their haiku (“the art of the snapshot, the detail”) and tanka grow increasingly erotic and take over his life, even supplanting his career. But when Ségolène offers to fly to Canada, Bilodo panics. I had two major problems with this: the exoticizing of a Black woman (why did she have to be from Guadeloupe, of all places?), and the bizarre ending, in which Bilodo, who has gradually become more like Grandpré, seems destined for his fate as well. I imagine this was supposed to be a psychological fable, but it was just a little bit silly for me, and the way it’s marketed will probably disappoint readers who are looking for either Harold Fry heart warming or cute Japanese cat/phone box adventures. (Public library) [108 pages] ![]()

Which of these catches your eye?

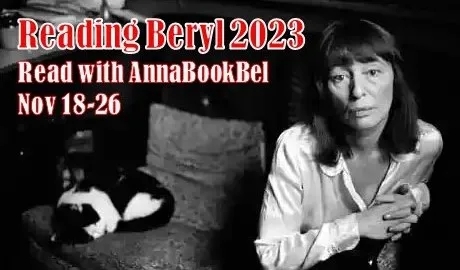

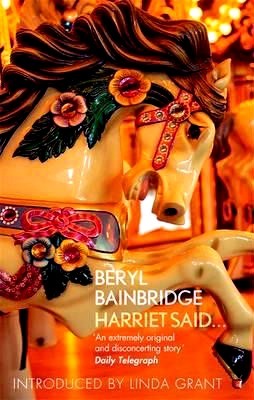

Harriet Said… by Beryl Bainbridge (#NovNov23 and #ReadingBeryl23)

Beryl Bainbridge Reading Week (hosted by Annabel) is a perfect chance to combine November challenges as most of Bainbridge’s works are under 200 pages. And today would have been the author’s birthday, too. Although Harriet Said… is the first book she wrote, it was rejected and not published until 1972, making it her third novel. I can see why publishers would have been wary of taking a risk on such a nasty little story from an unknown author. Even from an established writer this would be a hard one to stomach, subverting as it does the traditional notion of the innocence of childhood.

The title is also the first two words of the novel and tells us right away that the narrator (never named) is in thrall to her friend Harriet. The young teenager is on her summer holidays from boarding school, back in a Liverpool suburb. She lets Harriet set the agenda for their long, idle, unsupervised days: “she told me what to read, explained to me the things I read, told me what painters I should admire and why. I listened, I did as she said, but I did not feel much interest, at least not on my own, only when she was directing me.”

The girls dramatize their experiences in journal entries and make up stories for the people they meet on the local sand dunes, such as Peter Biggs, whom they dub Peter the Great or “the Tsar.” The narrator casts her relationship with him as a romance: “I wished I knew if I only imagined he cared for me, it seemed so strange the things I attributed to him. I did not know where the dream and the reality merged.” Together they decide to humble the Tsar.

{SPOILERS FOLLOW}

It’s uncomfortable for modern readers to encounter what is essentially a seduction plot between a teenager and a middle-aged man, but with the teen taking the active predator role. (And Harriet behind the scenes manipulating the interactions, rather like the Marquise de Merteuil in Dangerous Liaisons.) We’re fixated on the question of consent, but would the ultimate sex scene be classed as a rape? “‘Gerroff’, I wanted to shout, ‘Gerroff.’ But I did not want to hurt his feelings. … I was surprised how little discomfort I felt, apart from a kind of interior bruising, and how cheerful I was.” Harriet and the narrator both have a history of carrying on with grown men, and by peeping at windows see the Tsar having sex with Mrs Biggs on the couch. None of what they do seems accidental, or unfortunate, because they seem so determined to gravitate towards the smutty parts of life.

“What are little girls made of?

Sugar and spice,

And all that’s nice”

Fat chance!

“I tried to think what innocence meant and failed.”

“It was quite easy to bring myself to hurt him, he was such a fool.”

It’s not unexpected when the girls’ obsession leads to tragedy, but the exact form the collateral damage takes is a surprise. I’ve called this a ‘nasty little story’, but I mostly mean that in an admiring way, because it takes skill in plotting and characterization to make us keep reading even when all is so sordid.

Bainbridge has always reminded me of Penelope Fitzgerald in her concision, but I find Bainbridge less subtle and more edgy – a good combination, if you ask me. Harriet Said… feels like it falls on a continuum between, say, Barbara Comyns and Ottessa Moshfegh. I also wondered whether contemporary novelists like Eliza Clark (Penance) and Heather Darwent (The Things We Do to Our Friends) could have been influenced by the picture of teenage girls’ malevolence and the way that the action starts with hideous aftermath and then works backwards. This was a squirmy but memorable read. (Public library) [175 pages]

Remainders of the Day by Shaun Bythell & What Remains? by Rupert Callender

I raced to finish all the September releases on my stack by the 30th, thinking I’d review them in one go, but that ended up being far too unwieldy. There was way too much to say about each of these excellent books (the first two pairs are here and here; Blurb Your Enthusiasm by Louise Willder is still to come, probably on Wednesday). I’ve mentioned before that the month’s crop of nonfiction was about either books or death. Here’s one of each, linked by their ‘remain’ titles. Both:

Remainders of the Day: More Diaries from The Bookshop, Wigtown by Shaun Bythell

It’s just over five years since many of us were introduced to Wigtown and the ups and downs of running a bookshop there through Shaun Bythell’s The Diary of a Bookseller. (I’ve also reviewed the follow-up, Confessions of a Bookseller, which was an enjoyable read for me during a 2019 trip to Milan, and 2020’s Seven Kinds of People You Find in Bookshops.)

It’s just over five years since many of us were introduced to Wigtown and the ups and downs of running a bookshop there through Shaun Bythell’s The Diary of a Bookseller. (I’ve also reviewed the follow-up, Confessions of a Bookseller, which was an enjoyable read for me during a 2019 trip to Milan, and 2020’s Seven Kinds of People You Find in Bookshops.)

This third volume opens in February 2016. As in its predecessors, each monthly section is prefaced by an epigraph from a historical work on bookselling – this time R. M. Williamson’s 1904 Bits from an Old Bookshop. It’s the same winning formula as ever: the nearly daily entries start with the number of online orders received and filled, and end with the number of customers and the till takings for the day. (The average spend seems to be £10 per customer, which is fine in high tourist season but not so great in November and December when hardly anyone walks through the door.) In between, Bythell details notable customer encounters, interactions with shop helpers or local friends, trips out to buy book collections or go fishing, Wigtown events including the book festival, and the occasional snafu like the boiler breaking during a frigid November or his mum being hospitalized with a burst ulcer.

Reading May Sarton’s Encore recently, I came across a passage where she is reading a fellow writer’s journal (Doris Grumbach’s Coming into the End Zone):

I find hers extremely good reading, so I cannot bear to stop. I am reading it much too fast and I think I shall have to read it again. I know that I must not swallow it whole. There is something about a journal, I think, that does this to readers. So many readers tell me that they cannot put my journals down.

I’ve heard Zadie Smith say the same about Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle: it’s just the stuff of prosaic, everyday life and yet she refers to his memoirs/autofiction as literary crack.

I often read a whole month’s worth of entries at a sitting. I can think of a few specific reasons why Bythell’s journals are such addictive reading:

- “Sometimes you want to go where everybody knows your name.” Small-town settings are irresistible for many readers, and by now the fairly small cast of characters in Bythell’s books feel like old friends. Especially having been to Wigtown myself, I can picture many of the locations he writes about, and you get the rhythm of the seasons and the natural world as well as the town’s ebb and flow of visitors.

- (A related point) You know what to expect, and that’s a comforting thing. Bythell makes effective use of running gags. You know that when Granny, an occasional shop helper from Italy, appears, she will complain about her aches and pains, curse at Bythell and give him the finger. Petra’s belly-dancing class (held above the shop) will inevitably be poorly attended. If Eliot is visiting, he is sure to leave his shoes right where everyone will trip over them. Captain the cat will be portly and infuriating.

- What I most love about the series is the picture of the life cycle of books, from when they first enter the shop, or get picked up in his van, to when rejects are dropped at a Glasgow recycling plant. What happens in the meantime varies, with once-popular authors falling out of fashion while certain topics remain perennial bestsellers in the shop (railways, ornithology). There’s many a serendipitous moment when he comes across a book and it’s just what a customer wants, or buys a book as part of a lot and then sells it online the very next day. New, unpriced stock is always quick to go.

Also of note in this volume are his break-up with Amazon, after his account falls victim to algorithms and is suspended, the meta moment where he signs his first book contract with Profile, and the increasing presence of the Bookshop Band, who moved to Wigtown later in 2017. Bythell doesn’t seem to get much time to read – it’s a misconception of the bookselling life that you do nothing but read all day; you’d be better off as a book reviewer if that’s what you want – but when he does, it’s generally an intense experience: E.M. Forster’s sci-fi novella The Machine Stops (who knew it existed?!), Barbara Comyns’s A Touch of Mistletoe, Jonathan Safran Foer’s Everything Is Illuminated, and Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis.

I’m torn as to whether I hope there will be more year by year volumes filling in to the present day. As Annabel noted, the ‘where they are now’ approach in the Epilogue rather suggests that he and his publisher will leave it here at a trilogy. This might be for the best, as a few more pre-Covid years of the same routines could get old, though nosey parkers like myself will want to know how a confirmed bachelor turned into a family man…

Some favourite lines:

“Quiet day in the shop; even the cat looked bored.” (31 October)

“The life of the secondhand bookseller mainly involves moving boxes from one place to another, and trying to make them fit into a small space, like some sort of awful game of Tetris.”

(10 February and 15 March are great stand-alone entries that give a sense of what the whole is like. There are a lot of black-and-white photos printed amid the text in the first month; it’s a shame these don’t carry on through.)

With thanks to Profile Books for the free copy for review.

What Remains?: Life, Death and the Human Art of Undertaking by Rupert Callender

Call me morbid or call me realistic; in the last decade and a half I have read a lot of books about death, including terminal illness and bereavements. I’ve even read several nonfiction works by American mortician Caitlin Doughty. But I’ve not read anything quite like punk undertaker Rupert Callender’s manifesto about modern death and how much we get wrong in our conceptualization and conversations. It was poignant to be reading this in the weeks surrounding Queen Elizabeth II’s death – a time when death got more discussion than usual, yes, but when there was also some ridiculous pomp that obscured the basic human facts of it.

Callender is not okay with death, and never has been. When he was seven, his father died of a heart attack at age 63. His 1970s Edinburgh upbringing was shattered and his mother, who he has no doubt was doing her best, made a few terrible mistakes. First, a year before, she’d reassured him that his father wasn’t going to die. Second, she didn’t make him attend the funeral. (I still wish my mother had made me go back to tour my late grandmother’s house one final time when I was seven; instead, I stayed behind and played on a Ouija board with my cousins.) Third, she soon sent Callender away to boarding school, which left him feeling alone and betrayed. And lastly, when she died of cancer when he was 25, she had planned every detail of her funeral – whereas he believes that is a task for the survivors.

An orphan in his late twenties, Callender came across The Natural Death Handbook and it sealed his future. He’d been expelled from school and blown his inheritance; acid house culture had given him a sense of community. Now he had a vocation. The first funeral he coordinated was for a postman named Barry. The fourth was a suicide. Their first child burial was one of his partner’s daughter’s classmates.

Over the next two decades, he and his (now ex-)wife Claire based Totnes’ The Green Funeral Company on old-fashioned values and homespun ceremonies. They oppose the overmedicalization of death and the clinical detachment of places like crematoria. Callender is vehemently anti-embalming – an intrusive process that involves toxic substances. They encourage the bereaved to keep the body at home for the week before a funeral, if they feel able (ice packs like you’d use in a picnic cool bag will work a treat), and to be their own pallbearers to make the memory of the funeral day a physical one. He performs the eulogies himself, and they use cardboard coffins.

This is a slippery work for how it intersperses personal stories with polemic and poetic writing. Despite a roughly chronological throughline, it feels more like a thematic set of essays than a sequential narrative. Callender has turned death rituals into both performance art (including at festivals and in collaboration with The KLF) and political protests (e.g., a public funeral he conducted for a homeless man who died of exposure, the third such death in his town that year). While he doesn’t shy away from the gruesome realities of dealing with corpses, he always brings it back to fundamentals: matter is what we are, but who we were lives on in others’ loving memories. Death rituals plug us into a human lineage and proclaim meaning in the face of nothingness. Whether you’ve seen/read it all or never considered picking up a book about death, I recommend Callender’s sui generis approach.

Some favourite lines:

“[The practice of having official pallbearers] is all part of the emotional infantilising encouraged by the funeral industry, all part of being turned into an audience at one of the most significant moments in your family history, instead of being empowered as a family and a community.”

“each death we experience contains every death we have ever lived through, Russian dolls of bereavement waiting to be unpacked.”

“Only once you are dead can the full arc of your life be clearly seen, and telling that story out loud and truthfully to the people who shared it is a powerful social act that both binds us together and place us within our culture.”

With thanks to Chelsea Green for the proof copy for review.

And as a bonus, given that today is Indigenous Peoples’ Day in the USA, here’s an excerpt from my Shelf Awareness review of another book that came out last month:

No Country for Eight-Spot Butterflies: A Lyric Essay by Julian Aguon

An indigenous human rights lawyer, Aguon is passionate about protecting his homeland of Guam, which is threatened by climate change and military expansion. His tender collage of autobiographical vignettes and public addresses inspires activism and celebrates beauty worth preserving. The U.S. Department of Defense’s plan to site more Marines and firing ranges on Guam will destroy more than 1,000 acres of limestone forest—home to endemic and endangered species, including the Mariana eight-spot butterfly. Aguon has been a lead litigator in appeals rising all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Rejecting fatalism, he endorses peaceful resistance. Two commencement speeches, poems, a eulogy and an interview round out the varied and heartfelt collection.

An indigenous human rights lawyer, Aguon is passionate about protecting his homeland of Guam, which is threatened by climate change and military expansion. His tender collage of autobiographical vignettes and public addresses inspires activism and celebrates beauty worth preserving. The U.S. Department of Defense’s plan to site more Marines and firing ranges on Guam will destroy more than 1,000 acres of limestone forest—home to endemic and endangered species, including the Mariana eight-spot butterfly. Aguon has been a lead litigator in appeals rising all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Rejecting fatalism, he endorses peaceful resistance. Two commencement speeches, poems, a eulogy and an interview round out the varied and heartfelt collection.

I own too many unread books by…

A side effect of packing my library in preparation for moving: I’ve noticed there are certain authors whose works I tend to acquire secondhand and then stockpile rather than read. (I’ve also included in the tallies copies that I know are sitting in boxes in the USA.)

D.H. Lawrence: 9+ (Aaron’s Rod, Kangaroo, The Lost Girl, The Plumed Serpent, a Complete Poems volume, Sea and Sardinia, a Selected Short Stories volume, Studies in Classic American Literature, The Woman Who Rode Away)

D.H. Lawrence: 9+ (Aaron’s Rod, Kangaroo, The Lost Girl, The Plumed Serpent, a Complete Poems volume, Sea and Sardinia, a Selected Short Stories volume, Studies in Classic American Literature, The Woman Who Rode Away)

Lawrence was one of my research specialties as an undergraduate, so I read all his major works in my early twenties, as well as some lesser-known stuff, but haven’t felt compelled to pick up anything by him since. I’m not sure I’d care for him anymore, and it’s as if I don’t want to destroy the mystique. Yet I also can’t bring myself to get rid of these.

T.C. Boyle: 7 (A Friend of the Earth, The Inner Circle, Riven Rock, The Tortilla Curtain, Water Music, The Women, World’s End)

T.C. Boyle: 7 (A Friend of the Earth, The Inner Circle, Riven Rock, The Tortilla Curtain, Water Music, The Women, World’s End)

I’ve read five of Boyle’s books and have had a mixed experience, but his plots – whether biographical (Alfred Kinsey! the wives and lovers of Frank Lloyd Wright!) or environmental – tend to attract me. My husband has actually become the bigger fan, so has read 3–4 of these that I haven’t.

W. Somerset Maugham: 7 (Ashenden, Christmas Holiday, Creatures of Circumstance, Liza of Lambeth, The Magician, The Razor’s Edge, The Summing Up)

W. Somerset Maugham: 7 (Ashenden, Christmas Holiday, Creatures of Circumstance, Liza of Lambeth, The Magician, The Razor’s Edge, The Summing Up)

I read four of Maugham’s novels between 2014 and 2020. He’s an unappreciated author these days. Back when we had a free bookshop in my local mall, I volunteered weekly and most weeks came away with a backpack full of goodies. One week it was a partial leatherbound set of Maugham, which I’ve since supplemented with other paperbacks.

Robertson Davies: 6.5 (The Salterton Trilogy, The Deptford Trilogy, The Cornish Trilogy)

Robertson Davies: 6.5 (The Salterton Trilogy, The Deptford Trilogy, The Cornish Trilogy)

I loved Fifth Business and The Rebel Angels, read for subsequent Robertson Davies week challenges run by Lory, but made aborted attempts at both ‘sequels’, so the rest of his three major trilogies remain unread on my shelves.

Barbara Comyns: 5 (The Juniper Tree, The House of Dolls, Mr Fox, The Skin Chairs, A Touch of Mistletoe)

Barbara Comyns: 5 (The Juniper Tree, The House of Dolls, Mr Fox, The Skin Chairs, A Touch of Mistletoe)

I blame Liz for this one: after I read Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead during Novellas in November last year, she passed on her Comyns stash in a lovely Christmas parcel. Most are short enough to suit a future #NovNov, but I have The Juniper Tree earmarked for 20 Books of Summer (flora themed) and A Touch of Mistletoe for Christmastide.

Wendy Perriam: 5 (Absinthe for Elevenses, Breaking and Entering, Cuckoo, Michael, Michael, Sin City)

Wendy Perriam: 5 (Absinthe for Elevenses, Breaking and Entering, Cuckoo, Michael, Michael, Sin City)

Again, mostly Liz’s fault. (Though two others came from my Hay-on-Wye haul in September 2020.) I’ve still only read the one novel by Perriam, The Stillness The Dancing, but it was great and made me confident that I’d enjoy engaging with her repeated themes.

Richard Mabey: 4 (The Common Ground, Gilbert White biography, Nature Cure, The Unofficial Countryside)

Richard Mabey: 4 (The Common Ground, Gilbert White biography, Nature Cure, The Unofficial Countryside)

Considering that Mabey is the father of modern British nature writing, it’s kind of shocking that I’ve never read anything by him. I’ve put Nature Cure on my bedside pile to start soon.

Virginia Woolf: 4 (Between the Acts, The Waves, The Years, a volume of her diaries)

Virginia Woolf: 4 (Between the Acts, The Waves, The Years, a volume of her diaries)

I’ve tried The Waves and The Years and didn’t get further than a few pages; I find Woolf unreadably dense in a way I didn’t in my early twenties, when I studied To the Lighthouse (go figure). But there’s still this compulsion to have read them so that I can be a well-rounded literary person.

Kent Haruf: 3 (Plainsong, Eventide, Benediction)

Kent Haruf: 3 (Plainsong, Eventide, Benediction)

Our Souls at Night topped my backlist reads in 2020, but an attempt at reading Plainsong soon after failed. I think it was more involved, with more strands, than I was expecting after the simplicity of his novella. So the trilogy, acquired piecemeal secondhand, has languished on my shelves. I’ll try again with Plainsong this year.

Elizabeth Jane Howard: 3 (Marking Time, Confusion, Casting Off)

Elizabeth Jane Howard: 3 (Marking Time, Confusion, Casting Off)

I loved sinking into The Light Years, the first volume of The Cazalet Chronicles (read for a book club meeting last January), and even read the first 60 pages of the sequel, Marking Time, but then tailed off – you can see I’m terrible about continuing with series. But I’d like to get back into this one and, when I do, I have Books 2–4 out of five awaiting me.

Mary Karr: 3 (The Liars’ Club, Cherry, Lit)

Mary Karr: 3 (The Liars’ Club, Cherry, Lit)

Karr was key to the resurgence in popularity of memoirs in the 1990s. I’ve read her book about memoir (as well as a commencement speech she gave, and a volume of her poems), but not yet one of her actual memoirs. I found them all free or secondhand on trips back to the States. I don’t know whether it’s important to go in the chronological order listed above, or if I should just jump in with whichever, maybe Lit, about her struggle with alcoholism.

Sue Miller: 3 (The Lake Shore Limited, While I Was Gone, The World Below)

Sue Miller: 3 (The Lake Shore Limited, While I Was Gone, The World Below)

After I read Monogamy in December 2020 and it ended up on my Best-of list for that year, I scurried to get hold of a bunch of her other books. I’ve since read The Senator’s Wife, which was a big disappointment, but I’m looking forward to trying more.

Howard Norman: 3 (Devotion, The Northern Lights, What Is Left the Daughter)

Howard Norman: 3 (Devotion, The Northern Lights, What Is Left the Daughter)

I’ve read six of Norman’s books; he’s an underrated treasure of an author. I have no idea why I haven’t read these yet. Two are marooned in America, but The Northern Lights could make it onto a reading stack anytime. I just need the right excuse, it seems.

I’m thinking back to 2020, when I realized I had four unread Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie books on my shelves. Through various challenges – doorstoppers, summer reads, short stories, novellas – I managed to read them ALL that year, followed by another two in 2021. I don’t usually enjoy binging on particular authors in that way, but her books are different enough from each other (and just so good) that I didn’t mind.

I can’t promise to try the same tactic with these underread authors this year, but I can at least resolve to read one book by each of them, to reduce the backlog.

Do you have particular authors you own a lot by … but fail to read?

Short Classics Week of #NovNov: Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead

Can you believe it’s the last week of Novellas in November?! I’m hosting our final theme, short classics, and my first review is of a strange, mesmerizing 1950s novella.

We hope some of you will join in with our last buddy read, Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton (free to download here from Project Gutenberg if you don’t already have access). I’m looking forward to rereading it – in one sitting, if I can manage it – on Tuesday afternoon or Wednesday morning and will review it on Thursday. This list of 10 favourite classic novellas I put together last year might give you some more ideas of what to read this week.

Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead by Barbara Comyns (1954)

[146 pages]

I’d heard about this via its recent Daunt Books reissue and was attracted to the plague theme. The spark for the story was a real-life event in France in 1951, but Comyns takes imaginative liberties. In 1911, a Warwickshire village is overtaken by calamity: first a flood and then a mysterious sickness. The first line – “The ducks swam through the drawing-room window” – sets up a jolly, fable-like atmosphere as the Willoweed family go rowing through their garden. And yet there’s death all over the place. The multitude of drowned animals soon cedes to a roll call of human casualties. Some deaths are self-inflicted and others result from rapid illness, but all are gruesome. The general pattern of the sickness seems to be stomach pains, fits, bleeding and death, all within a few days. At first, we don’t know if what we’re looking at is a medical phenomenon or a case of mass hysteria. Either is rich fodder for fiction.

I’d heard about this via its recent Daunt Books reissue and was attracted to the plague theme. The spark for the story was a real-life event in France in 1951, but Comyns takes imaginative liberties. In 1911, a Warwickshire village is overtaken by calamity: first a flood and then a mysterious sickness. The first line – “The ducks swam through the drawing-room window” – sets up a jolly, fable-like atmosphere as the Willoweed family go rowing through their garden. And yet there’s death all over the place. The multitude of drowned animals soon cedes to a roll call of human casualties. Some deaths are self-inflicted and others result from rapid illness, but all are gruesome. The general pattern of the sickness seems to be stomach pains, fits, bleeding and death, all within a few days. At first, we don’t know if what we’re looking at is a medical phenomenon or a case of mass hysteria. Either is rich fodder for fiction.

Ebin Willoweed writes it all up for the newspapers, leaving his motherless daughters to do the hard work of cleaning up from the flood damage and looking after their little brother. Meanwhile, Ebin’s brutal, selfish mother presides over the household like some ogre in a fairy tale. The title (which comes from Longfellow) makes it clear that even those who survive this epidemic will not escape totally unscathed.

Comyns is entirely unsentimental in this, her third novel; those characters who are not horrible are typically passive, and the humour is very black indeed. It’s illuminating to observe how each figure responds to tragedy and what their priorities are. In general, though, it’s not a rosy picture of human nature. While I was initially reminded of H.E. Bates’s The Darling Buds of May and Stella Gibbons’s Cold Comfort Farm, this feels darker. There is some casual racism and the morbidness probably won’t be for everyone, but I remained gripped, wondering how on earth this would conclude. I liked it enough to try more by Comyns – my library has a copy of the brilliantly titled Our Spoons Came from Woolworths, but I’m also open to other suggestions. (Secondhand purchase)

Keep in touch via Twitter (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books). We’ll add any of your review links in to our master posts. Feel free to use the terrific feature image Cathy made and don’t forget the hashtag #NovNov.