Book Serendipity, January to February

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away! Feel free to join in with your own.

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- An old woman with purple feet (due to illness or injury) in one story of Brawler by Lauren Groff and John of John by Douglas Stuart.

- Someone is pushed backward and dies of the head injury in Zofia Nowak’s Book of Superior Detecting by Piotr Cieplak and one story of Brawler by Lauren Groff.

- The Hindenburg disaster is mentioned in A Long Game by Elizabeth McCracken and Evensong by Stewart O’Nan.

- Reluctance to cut into a corpse during medical school and the dictum ‘see one, do one, teach one’ in the graphic novel See One, Do One, Teach One: The Art of Becoming a Doctor by Grace Farris and Separate by C. Boyhan Irvine.

A remote Scottish island setting and a harsh father in Muckle Flugga by Michael Pedersen [Shetland] and John of John by Douglas Stuart [Harris]. (And another Scottish island setting in A Calendar of Love by George Mackay Brown [Orkney].)

A remote Scottish island setting and a harsh father in Muckle Flugga by Michael Pedersen [Shetland] and John of John by Douglas Stuart [Harris]. (And another Scottish island setting in A Calendar of Love by George Mackay Brown [Orkney].)

- A mention of genuine Harris tweed in Alone in the Classroom by Elizabeth Hay and John of John by Douglas Stuart.

- The Katharine Hepburn film The Philadelphia Story is mentioned in The Girls’ Guide to Hunting and Fishing by Melissa Bank and Woman House by Lauren W. Westerfield.

- A mention of Icelandic poppies in Nighthawks by Lisa Martin and Boundless by Kathleen Winter.

- Vita Sackville-West is mentioned in the Orlando graphic novel adaptation by Susanne Kuhlendahl and Boundless by Kathleen Winter.

- Fear of bear attacks in Black Bear by Trina Moyles and Boundless by Kathleen Winter. Bears also feature in A Rough Guide to the Heart by Pam Houston and No Paradise with Wolves by Katie Stacey. [Looking through children’s picture books at the library the other week, I was struck by how many have bears in the title. Dozens!]

- I was reading books called Memory House (by Elaine Kraf) and Woman House (by Lauren W. Westerfield) at the same time, both of them pre-release books for Shelf Awareness reviews.

- An adolescent girl is completely ignorant of the facts of menstruation in I Who Have Never Known Men by Jacqueline Harpman and Carrie by Stephen King.

- Camembert is eaten in The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier and Ordinary Saints by Niamh Ni Mhaoileoin.

- A herbal tonic is sought to induce a miscarriage in The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley and Bog Queen by Anna North.

- Vicks VapoRub is mentioned in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom, Kin by Tayari Jones, and Dirt Rich by Graeme Richardson.

- An adolescent girl only admits to her distant mother that she’s gotten her first period because she needs help dealing with a stain (on her bedding / school uniform) in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom, An Experiment in Love by Hilary Mantel, and Ordinary Saints by Niamh Ni Mhaoileoin. (I had to laugh at the mother asking the narrator of the Mantel: “Have you got jam on your underskirt?”) Basically, first periods occurred a lot in this set! They are also mentioned in A Little Feral by Maria Giesbrecht and one story of The Blood Year Daughter by G.G. Silverman. [I also had three abortion scenes in this cycle, but I think it would constitute spoilers to say which novels they appeared in.)

- A casual job cleaning pub/bar toilets in Kin by Tayari Jones and John of John by Douglas Stuart.

- Kansas City is a location mentioned in Strangers by Belle Burden, Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell, and Dreams in Which I’m Almost Human by Hannah Soyer. (Not actually sure if that refers to Kansas or Missouri in two of them.)

- The notion of “flirting with God” is mentioned in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom and A Little Feral by Maria Giesbrecht.

- A signature New Orleans cocktail, the Sazerac (a variation on the whisky old-fashioned containing absinthe), appears in Kin by Tayari Jones and Let the Bad Times Roll by Alice Slater.

- An older person’s smell brings back childhood memories in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

- The fact that complaining of chest pain will get you seen right away in an emergency room is mentioned in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom and The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley.

- Thickly buttered toast is a favoured snack in The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier and An Experiment in Love by Hilary Mantel.

A scene of trying on fur coats in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom and An Experiment in Love by Hilary Mantel.

A scene of trying on fur coats in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom and An Experiment in Love by Hilary Mantel.

- Lime and soda is drunk in Our Numbered Bones by Katya Balen, Kin by Tayari Jones, and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

- A husband 17 years older than his wife in Kin by Tayari Jones and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

- The protagonist seems to hold a special attraction for old men in Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

- A tattoo of a pottery shard (her ex-husband’s) in Strangers by Belle Burden and one of an arrowhead (her own) in Dreams in Which I’m Almost Human by Hannah Soyer.

- A relationship with an older editor at a publishing house: The Girls’ Guide to Hunting and Fishing by Melissa Bank (romantic) and Whistler by Ann Patchett (stepfather–stepdaughter).

- Repeated vomiting and a fever of 103–104°F leads to a diagnosis of appendicitis in My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

Multiple pet pugs in Strangers by Belle Burden and My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt.

Multiple pet pugs in Strangers by Belle Burden and My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt.

- Palm crosses are mentioned in My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt and Kin by Tayari Jones.

- A Miss Jemison in Kin by Tayari Jones and a Miss Jamieson in Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael.

- Pasley as a surname in Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael and a place name (Pasley Bay) in Boundless by Kathleen Winter.

- A remark on a character’s unwashed hair in My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt and Let the Bad Times Roll by Alice Slater.

- A mention of a monkey’s paw in Museum Visits by Éric Chevillard and Let the Bad Times Roll by Alice Slater.

- A character gets 26 (22) stitches in her face (head) after a car accident, a young person who’s vehemently anti-smoking, and a mention of being dusted orange from eating Cheetos, in Whistler by Ann Patchett and Let the Bad Times Roll by Alice Slater.

- Pre-eclampsia occurs in Strangers by Belle Burden and The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley.

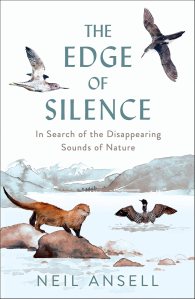

- There’s a chapter on searching for corncrakes on the Isle of Coll (the Inner Hebrides of Scotland) in The Edge of Silence by Neil Ansell, which I read last year; this year I reread the essay on the same topic in Findings by Kathleen Jamie.

- Worry over women with long hair being accidentally scalped – if a horse steps on her ponytail in Mare by Emily Haworth-Booth; if trapped in a London Underground escalator in Leaving Home by Mark Haddon.

A pet ferret in My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt and Shooting Up by Jonathan Tepper.

A pet ferret in My Grandmothers and I by Diana Holman-Hunt and Shooting Up by Jonathan Tepper.

- A dodgy doctor who molests a young female patient in Leaving Home by Mark Haddon and Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael.

- A high school girl’s inappropriate relationship with her English teacher is the basis for Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom, and then Half His Age by Jennette McCurdy, which I started soon after.

- College roommates who become same-sex lovers, one of whom goes on to have a heterosexual marriage, in Kin by Tayari Jones and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

- A mention of Sephora (the cosmetics shop) in Half His Age by Jennette McCurdy and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

- A discussion of the Greek mythology character Leda in Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell and Whistler by Ann Patchett (where it’s also a character name).

- A workaholic husband who rarely sees his children and leaves their care to his wife in Strangers by Belle Burden and Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell.

- An apparently wealthy man who yet steals food in Strangers by Belle Burden and Let the Bad Times Roll by Alice Slater.

- Characters named Lulubelle in Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell and Lulabelle in Kin by Tayari Jones.

- Characters named Ruth in Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell, Kin by Tayari Jones, and Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael.

A mention of Mary McLeod Bethune in Negroland by Margo Jefferson and Kin by Tayari Jones.

A mention of Mary McLeod Bethune in Negroland by Margo Jefferson and Kin by Tayari Jones.

- Doing laundry at a whorehouse in Kin by Tayari Jones and Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael.

- A male character nicknamed Doll in John of John by Douglas Stuart and then Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael.

- A mention of tuberculosis of the stomach in Findings by Kathleen Jamie and Shooting Up by Jonathan Tepper. I was also reading a whole book on tuberculosis, Everything Is Tuberculosis by John Green, at the same time.

- Mention of Doberman dogs in Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell and one story of The Blood Year Daughter by G.G. Silverman.

- Extreme fear of flying in Leaving Home by Mark Haddon and Whistler by Ann Patchett.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

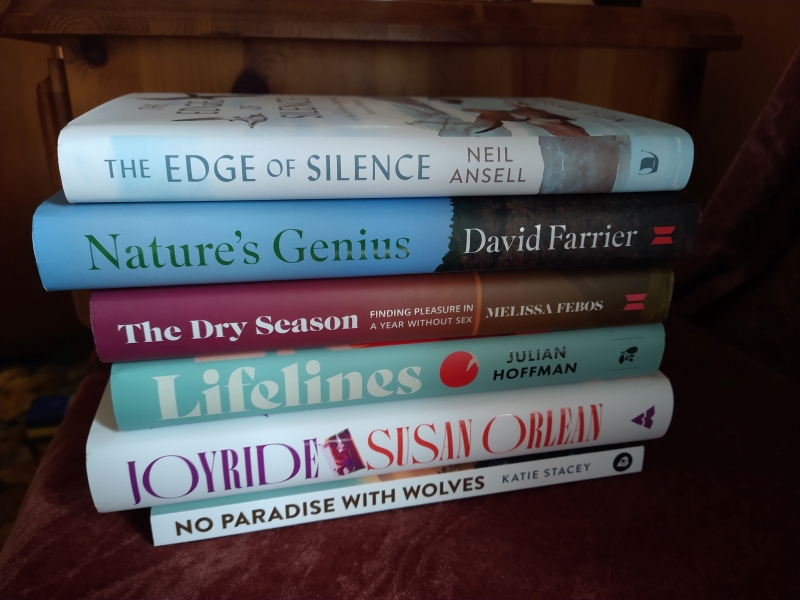

#ReadIndies Nonfiction Catch-Up: Ansell, Farrier, Febos, Hoffman, Orlean and Stacey

These are all 2025 releases; for some, it’s approaching a year since I was sent a review copy or read the book. Silly me. At last, I’ve caught up. Reading Indies month, hosted by Kaggsy in memory of her late co-host Lizzy Siddal, is the perfect time to feature books from five independent publishers. I have four works that might broadly be classed as nature writing – though their topics range from birdsong and technology to living in Greece and rewilding a plot in northern Spain – and explorations of celibacy and the writer’s profession.

The Edge of Silence: In Search of the Disappearing Sounds of Nature by Neil Ansell

Ansell draws parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis. He puts together a wish list of species – mostly seabirds (divers, grebes), but also inland birds (nightjars) and a couple of non-avian representatives (otters) – that he wants to hear and sets off on public transport adventures to find them. “I must find beauty where I can, and while I still can,” he vows. From his home on the western coast of Scotland near the Highlands, this involves trains or buses that never align with the ferry timetables. Furthest afield for him are two nature reserves in northern England where his mission is to hear bitterns “booming” and natterjack toads croaking at night. There are also mountain excursions to locate ptarmigan, greenshank, and black grouse. His island quarry includes Manx shearwaters (Rum), corncrakes (Coll), puffins (Sanday), and storm petrels (Shetland).

Ansell draws parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis. He puts together a wish list of species – mostly seabirds (divers, grebes), but also inland birds (nightjars) and a couple of non-avian representatives (otters) – that he wants to hear and sets off on public transport adventures to find them. “I must find beauty where I can, and while I still can,” he vows. From his home on the western coast of Scotland near the Highlands, this involves trains or buses that never align with the ferry timetables. Furthest afield for him are two nature reserves in northern England where his mission is to hear bitterns “booming” and natterjack toads croaking at night. There are also mountain excursions to locate ptarmigan, greenshank, and black grouse. His island quarry includes Manx shearwaters (Rum), corncrakes (Coll), puffins (Sanday), and storm petrels (Shetland).

Camping in a tent means cold nights, interrupted sleep, and clouds of midges, but it’s all worth it to have unrepeatable wildlife experiences. He has a very high hit rate for (seeing and) hearing what he intends to, even when they’re just on the verge of what he can decipher with his hearing aids. On the rare occasions when he misses out, he consoles himself with earlier encounters. “I shall settle for the memory, for it feels unimprovable, like a spell that I do not want to break.” I’ve read all of Ansell’s nature memoirs and consider him one of the UK’s top writers on the natural world. His accounts of his low-carbon travels are entertaining, and the tug-of-war between resisting and coming to terms with his disability is heartening. “I have spent this year in defiance of a relentless, unstoppable countdown,” he reflects. What makes this book more universal than niche is the deadline: we and all of these creatures face extinction. Whether it’s sooner or later depends on how we act to address the environmental polycrisis.

With thanks to Birlinn for the free copy for review.

Nature’s Genius: Evolution’s Lessons for a Changing Planet by David Farrier

Farrier’s Footprints, which tells the story of the human impact on the Earth, was one of my favourite books of 2020. This contains a similar blend of history, science, and literary points of reference (Farrier is a professor of literature and the environment at the University of Edinburgh), with past changes offering a template for how the future might look different. “We are forcing nature to reimagine itself, and to avert calamity we need to do the same,” he writes. Cliff swallows have evolved blunter wings to better evade cars; captive breeding led foxes to develop the domesticated traits of pet dogs.

Farrier’s Footprints, which tells the story of the human impact on the Earth, was one of my favourite books of 2020. This contains a similar blend of history, science, and literary points of reference (Farrier is a professor of literature and the environment at the University of Edinburgh), with past changes offering a template for how the future might look different. “We are forcing nature to reimagine itself, and to avert calamity we need to do the same,” he writes. Cliff swallows have evolved blunter wings to better evade cars; captive breeding led foxes to develop the domesticated traits of pet dogs.

It’s not just other species that experience current evolution. Thanks to food abundance and a sedentary lifestyle, humans show a “consumer phenotype,” which superseded the Palaeolithic (95% of human history) and tends toward earlier puberty, autoimmune diseases, and obesity. Farrier also looks at notions of intelligence, language, and time in nature. Sustainable cities will have to cleverly reuse materials. For instance, The Waste House in Brighton is 90% rubbish. (This I have to see!)

There are many interesting nuggets here, and statements that are difficult to argue with, but I struggled to find an overall thread. Cool to see my husband’s old housemate mentioned, though. (Duncan Geere, for collaborating on a hybrid science–art project turning climate data into techno music.)

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

The Dry Season: Finding Pleasure in a Year without Sex by Melissa Febos

Febos considers but rejects the term “sex addiction” for the years in which she had compulsive casual sex (with “the Last Man,” yes, but mostly with women). Since her early teen years, she’d never not been tied to someone. Brief liaisons alternated with long-term relationships: three years with “the Best Ex”; two years that were so emotionally tumultuous that she refers to the woman as “the Maelstrom.” It was the implosion of the latter affair that led to Febos deciding to experiment with celibacy, first for three months, then for a whole year. “I felt feral and sad and couldn’t explain it, but I knew that something had to change.”

The quest involved some research into celibate movements in history, but was largely an internal investigation of her past and psyche. Febos found that she was less attuned to the male gaze. Having worn high heels almost daily for 20 years, she discovered she’s more of a trainers person. Although she was still tempted to flirt with attractive women, e.g. on an airplane, she consciously resisted the impulse to spin random meetings into one-night stands. (A therapist had stopped her short with the blunt observation, “you use people.”) With a new focus on the life of the mind, she insists, “My life was empty of lovers and more full than it had ever been.” (This reminded me of Audre Lorde’s writing on the erotic.) As Silvana Panciera, an Italian scholar on the beguines (a secular nun-like sisterhood), told her: “When you don’t belong to anyone, you belong to everyone. You feel able to love without limits.”

The quest involved some research into celibate movements in history, but was largely an internal investigation of her past and psyche. Febos found that she was less attuned to the male gaze. Having worn high heels almost daily for 20 years, she discovered she’s more of a trainers person. Although she was still tempted to flirt with attractive women, e.g. on an airplane, she consciously resisted the impulse to spin random meetings into one-night stands. (A therapist had stopped her short with the blunt observation, “you use people.”) With a new focus on the life of the mind, she insists, “My life was empty of lovers and more full than it had ever been.” (This reminded me of Audre Lorde’s writing on the erotic.) As Silvana Panciera, an Italian scholar on the beguines (a secular nun-like sisterhood), told her: “When you don’t belong to anyone, you belong to everyone. You feel able to love without limits.”

Intriguing that this is all a retrospective, reflecting on her thirties; Febos is now in her mid-forties and married to a woman (poet Donika Kelly). Clearly she felt that it was an important enough year – with landmark epiphanies that changed her and have the potential to help others – to form the basis for a book. For me, she didn’t have much new to offer about celibacy, though it was interesting to read about the topic from an areligious perspective. But I admire the depth of her self-knowledge, and particularly her ability to recreate her mindset at different times. This is another one, like her Girlhood, to keep on the shelf as a model.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

Lifelines: Searching for Home in the Mountains of Greece by Julian Hoffman

Hoffman’s Irreplaceable was my nonfiction book of 2019. Whereas that was a work with a global environmentalist perspective, Lifelines is more personal in scope. It tracks the author’s unexpected route from Canada via the UK to Prespa, a remote area of northern Greece that’s at the crossroads with Albania and North Macedonia. He and his wife, Julia, encountered Prespa in a book and, longing for respite from the breakneck pace of life in London, moved there in 2000. “Like the rivers that spill into these shared lakes, lifelines rarely flow straight. Instead, they contain bends, meanders and loops; they hold, at times, turns of extraordinary surprise.” Birdwatching, which Hoffman suggests is as “a way of cultivating attention,” had been their gateway into a love for nature developed over the next quarter-century and more, and in Greece they delighted in seeing great white and Dalmatian pelicans (which feature on the splendid U.S. cover. It would be lovely to have an illustrated edition of this.)

Hoffman’s Irreplaceable was my nonfiction book of 2019. Whereas that was a work with a global environmentalist perspective, Lifelines is more personal in scope. It tracks the author’s unexpected route from Canada via the UK to Prespa, a remote area of northern Greece that’s at the crossroads with Albania and North Macedonia. He and his wife, Julia, encountered Prespa in a book and, longing for respite from the breakneck pace of life in London, moved there in 2000. “Like the rivers that spill into these shared lakes, lifelines rarely flow straight. Instead, they contain bends, meanders and loops; they hold, at times, turns of extraordinary surprise.” Birdwatching, which Hoffman suggests is as “a way of cultivating attention,” had been their gateway into a love for nature developed over the next quarter-century and more, and in Greece they delighted in seeing great white and Dalmatian pelicans (which feature on the splendid U.S. cover. It would be lovely to have an illustrated edition of this.)

One strand of this warm and fluent memoir is about making a home in Greece: buying and renovating a semi-derelict property, experiencing xenophobia and hospitality from different quarters, and finding a sense of belonging. They’re happy to share their home with nesting wrens, who recur across the book and connect to the tagline of “a story of shelter shared.” In probing the history of his adopted country, Hoffman comes to realise the false, arbitrary nature of borders – wildlife such as brown bears and wolves pay these no heed. Everything is connected and questions of justice are always intersectional. The Covid pandemic and avian influenza (which devastated the region’s pelicans) are setbacks that Hoffman addresses honestly. But the lingering message is a valuable one of bridging divisions and learning how to live in harmony with other people – and with other species.

One strand of this warm and fluent memoir is about making a home in Greece: buying and renovating a semi-derelict property, experiencing xenophobia and hospitality from different quarters, and finding a sense of belonging. They’re happy to share their home with nesting wrens, who recur across the book and connect to the tagline of “a story of shelter shared.” In probing the history of his adopted country, Hoffman comes to realise the false, arbitrary nature of borders – wildlife such as brown bears and wolves pay these no heed. Everything is connected and questions of justice are always intersectional. The Covid pandemic and avian influenza (which devastated the region’s pelicans) are setbacks that Hoffman addresses honestly. But the lingering message is a valuable one of bridging divisions and learning how to live in harmony with other people – and with other species.

With thanks to Elliott & Thompson for the free copy for review.

Joyride by Susan Orlean

As a long-time staff writer for The New Yorker, Orlean has had the good fortune to be able to follow her curiosity wherever it leads, chasing the subjects that interest her and drawing readers in with her infectious enthusiasm. She grew up in suburban Ohio, attended college in Michigan, and lived in Portland, Oregon and Boston before moving to New York City. Her trajectory was from local and alternative papers to the most enviable of national magazines: Esquire, Rolling Stone and Vogue. Orlean gives behind-the-scenes information on lots of her early stories, some of which are reprinted in an appendix. “If you’re truly open, it’s easy to fall in love with your subject,” she writes; maintaining objectivity could be difficult, as when she profiled an Indian spiritual leader with a cult following; and fended off an interviewee’s attachment when she went on the road with a Black gospel choir.

Her personal life takes a backseat to her career, though she is frank about the breakdown of her first marriage, her second chance at love and late motherhood, and a surprise bout with lung cancer. The chronological approach proceeds book by book, delving into her inspirations, research process and publication journeys. Her first book was about Saturday night as experienced across America. It was a more innocent time, when subjects were more trusting. Orlean and her second husband had farms in the Hudson Valley of New York and in greater Los Angeles, and she ended up writing a lot about animals, with books on Rin Tin Tin and one collecting her animal pieces. There was also, of course, The Library Book, about the wild history of the main Los Angeles public library. But it’s her The Orchid Thief – and the movie (not) based on it, Adaptation – that’s among my favourites, so the long section on that was the biggest thrill for me. There are also black-and-white images scattered through.

Her personal life takes a backseat to her career, though she is frank about the breakdown of her first marriage, her second chance at love and late motherhood, and a surprise bout with lung cancer. The chronological approach proceeds book by book, delving into her inspirations, research process and publication journeys. Her first book was about Saturday night as experienced across America. It was a more innocent time, when subjects were more trusting. Orlean and her second husband had farms in the Hudson Valley of New York and in greater Los Angeles, and she ended up writing a lot about animals, with books on Rin Tin Tin and one collecting her animal pieces. There was also, of course, The Library Book, about the wild history of the main Los Angeles public library. But it’s her The Orchid Thief – and the movie (not) based on it, Adaptation – that’s among my favourites, so the long section on that was the biggest thrill for me. There are also black-and-white images scattered through.

It was slightly unfortunate that I read this at the same time as Book of Lives – who could compete with Margaret Atwood? – but it is, yes, a joy to read about Orlean’s writing life. She’s full of enthusiasm and good sense, depicting the vocation as part toil and part magic:

“I find superhuman self-confidence when I’m working on a story. The bashfulness and vulnerability that I might otherwise experience in a new setting melt away, and my desire to connect, to observe, to understand, powers me through.”

“I like to do a gut check any time I dismiss or deplore something I don’t know anything about. That feels like reason enough to learn about it.”

“anything at all is worth writing about if you care about it and it makes you curious and makes you want to holler about it to other people”

With thanks to Atlantic Books for the free copy for review.

No Paradise with Wolves: A Journey of Rewilding and Resilience by Katie Stacey

I had the good fortune to visit Wild Finca, Luke Massey and Katie Stacey’s rewilding site in Asturias, while on holiday in northern Spain in May 2022, and was intrigued to learn more about their strategy and experiences. This detailed account of the first four years begins with their search for a property in 2018 and traces the steps of their “agriwilding” of a derelict farm: creating a vegetable garden and tending to fruit trees, but also digging ponds, training up hedgerows, and setting up rotational grazing. Their every decision went against the grain. Others focussed on one crop or type of livestock while they encouraged unruly variety, keeping chickens, ducks, goats, horses and sheep. Their neighbours removed brush in the name of tidiness; they left the bramble and gorse to welcome in migrant birds. New species turned up all the time, from butterflies and newts to owls and a golden fox.

Luke is a wildlife guide and photographer. He and Katie are conservation storytellers, trying to get people to think differently about land management. The title is a Spanish farmers’ and hunters’ slogan about the Iberian wolf. Fear of wolves runs deep in the region. Initially, filming wolves was one of the couple’s major goals, but they had to step back because staking out the animals’ haunts felt risky; better to let them alone and not attract the wrong attention. (Wolf hunting was banned across Spain in 2021.) There’s a parallel to be found here between seeing wolves as a threat and the mild xenophobia the couple experienced. Other challenges included incompetent house-sitters, off-lead dogs killing livestock, the pandemic, wildfires, and hunters passing through weekly (as in France – as we discovered at Le Moulin de Pensol in 2024 – hunters have the right to traverse private land in Spain).

Luke and Katie hope to model new ways of living harmoniously with nature – even bears and wolves, which haven’t made it to their land yet, but might in the future – for the region’s traditional farmers. They’re approaching self-sufficiency – for fruit and vegetables, anyway – and raising their sons, Roan and Albus, to love the wild. We had a great day at Wild Finca: a long tour and badger-watching vigil (no luck that time) led by Luke; nettle lemonade and sponge cake with strawberries served by Katie and the boys. I was clear how much hard work has gone into the land and the low-impact buildings on it. With the exception of some Workaway volunteers, they’ve done it all themselves.

Katie Stacey’s storytelling is effortless and conversational, making this impassioned memoir a pleasure to read. It chimed perfectly with Hoffman’s writing (above) about the fear of bears and wolves, and reparation policies for farmers, in Europe. I’d love to see the book get a bigger-budget release complete with illustrations, a less misleading title, the thorough line editing it deserves, and more developmental work to enhance the literary technique – as in the beautiful final chapter, a present-tense recreation of a typical walk along The Loop. All this would help to get the message the wider reach that authors like Isabella Tree have found. “I want to be remembered for the wild spaces I leave behind,” Katie writes in the book’s final pages. “I want to be remembered as someone who inspired people to seek a deeper connection to nature.” You can’t help but be impressed by how much of a difference two people seeking to live differently have achieved in just a handful of years. We can all rewild the spaces available to us (see also Kate Bradbury’s One Garden against the World), too.

With thanks to Earth Books (Collective Ink) for the free copy for review.

Which of these do you fancy reading?

Truth Is Stranger than Fiction: The Summer of the Bear by Bella Pollen

“The island exerted a mesmeric pull. She had felt the magic of it all her life, but it was a magic that stayed on the island. You couldn’t take it with you.”

~MILD SPOILERS IN THIS ONE~

One of my reading selections for our recent trip to the Outer Hebrides was The Summer of the Bear by Bella Pollen, which is set on a lightly fictionalized version of North Uist. It’s the summer of 1979 and the recently bereaved Fleming family is on the way from London to the island for their usual summer holiday. This year everything looks different. The patriarch, Nicky, had a fatal fall from a roof in Bonn, where he was stationed as a diplomat. Whether it was an accident or suicide is yet to be determined.

One of my reading selections for our recent trip to the Outer Hebrides was The Summer of the Bear by Bella Pollen, which is set on a lightly fictionalized version of North Uist. It’s the summer of 1979 and the recently bereaved Fleming family is on the way from London to the island for their usual summer holiday. This year everything looks different. The patriarch, Nicky, had a fatal fall from a roof in Bonn, where he was stationed as a diplomat. Whether it was an accident or suicide is yet to be determined.

Now it’s just Letitia and the three children. Georgie is awaiting exam results and university offers. Jamie is the youngest and has an earnest, innocent, literal mind (I believe I first came across the novel in connection to my interest in depictions of autism, and I assume he is meant to be on the spectrum). Alba, smack in the middle, acts out via snarky comments as well as shoplifting and tormenting her brother. The locals look out for each of the family members and make allowances for the strange things they do because of grief.

In the meantime, there’s an escaped grizzly bear on the loose in the islands. The chapters rotate through the main characters’ perspectives and include short imaginings of the bear’s journey. I found it hard to take these seriously – could an animal really be in awe of the Northern Lights? – especially when Pollen begins to suggest telepathic communication occurring between Jamie and the bear.

I was a third of the way into the novel before I learned that the bear subplot was based on a true story – my husband saw a sidebar about it in the guidebook. I’d had no idea! Hercules the trained bear starred in films and commercials. In 1980, while filming an ad for Andrex, he slipped his rope and remained on the run for several weeks despite a military search, straying 20 miles and losing half his body weight before he was tranquillized and returned to his owner. We made the pilgrimage to his burial site in Langass Woodland.

Pollen herself spent childhood summers in the Outer Hebrides and remembered the buzz about the hunt for Hercules. This plus the recent death of their father makes it a pivotal summer for all three children. Though in general I appreciated the descriptions of the island, and liked the character interactions and Jamie’s guilelessness and gumption, I felt uncomfortable with his portrayal. I didn’t think it realistic for an 11-year-old to not understand the fact of death; it seemed almost offensive to suggest that, because he’s on the autism spectrum, he wouldn’t understand euphemisms about loss. The sequence where he goes looking for “Heaven” is pretty excruciating.

Add that to the unlikelihood of Jamie’s participation in the bear’s discovery and an unnecessary conspiracy element about Nicky’s death and this novel didn’t live up to its potential for me. I’d read one other book by Pollen, the memoir Meet Me in the In-Between, but won’t venture further into her work. Still, this was an interesting curio. (Public library)

[I thought about including this (and Sarah Moss’s Night Waking) in my flora-themed 20 Books of Summer because of the author’s surname, but I think I’ll make my 20 without stretching that far!]

Six Degrees of Separation: From Wintering to The Summer of the Bear

This month we begin with Wintering by Katherine May. I reviewed this for the Times Literary Supplement back in early 2020 and enjoyed the blend of memoir, nature and travel writing. (See also Kate’s opening post.)

#1 May travels to Iceland, which is the location of Sarah Moss’s memoir Names for the Sea. I’ve read nine of Moss’s books and consider her one of my favourite contemporary authors. (I’m currently rereading Night Waking.)

#1 May travels to Iceland, which is the location of Sarah Moss’s memoir Names for the Sea. I’ve read nine of Moss’s books and consider her one of my favourite contemporary authors. (I’m currently rereading Night Waking.)

#2 Nancy Campbell’s Fifty Words for Snow shares an interest in languages and naming. I noted that the Icelandic “hundslappadrifa” refers to snowflakes as large as a dog’s paw.

#2 Nancy Campbell’s Fifty Words for Snow shares an interest in languages and naming. I noted that the Icelandic “hundslappadrifa” refers to snowflakes as large as a dog’s paw.

#3 In 2018–19, Campbell was the poet laureate for the Canal & River Trust. As part of her tour of the country’s waterways, she came to Newbury and wrote a poem on commission about the community gardening project I volunteer with. (Here’s her blog post about the experience.) Three Women and a Boat by Anne Youngson is about a canalboat journey.

#3 In 2018–19, Campbell was the poet laureate for the Canal & River Trust. As part of her tour of the country’s waterways, she came to Newbury and wrote a poem on commission about the community gardening project I volunteer with. (Here’s her blog post about the experience.) Three Women and a Boat by Anne Youngson is about a canalboat journey.

#4 Youngson’s novel was inspired by the setup of Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat. Another book loosely based on a classic is The Decameron Project, a set of 29 short stories ranging from realist to dystopian in their response to pandemic times.

#4 Youngson’s novel was inspired by the setup of Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat. Another book loosely based on a classic is The Decameron Project, a set of 29 short stories ranging from realist to dystopian in their response to pandemic times.

#5 Another project updating the classics was the Hogarth Shakespeare series. One of these books (though not my favourite) was The Gap of Time by Jeanette Winterson, her take on The Winter’s Tale.

#5 Another project updating the classics was the Hogarth Shakespeare series. One of these books (though not my favourite) was The Gap of Time by Jeanette Winterson, her take on The Winter’s Tale.

#6 Even if you’ve not read it (it happened to be on my undergraduate curriculum), you probably know that The Winter’s Tale famously includes the stage direction “Exit, pursued by a bear.” I’m finishing with The Summer of the Bear by Bella Pollen, one of the novels I read on my trip to the Outer Hebrides because it’s set on North Uist. I’ll review it in full soon, but for now will say that it does actually have a bear in it, and is based on a true story.

#6 Even if you’ve not read it (it happened to be on my undergraduate curriculum), you probably know that The Winter’s Tale famously includes the stage direction “Exit, pursued by a bear.” I’m finishing with The Summer of the Bear by Bella Pollen, one of the novels I read on my trip to the Outer Hebrides because it’s set on North Uist. I’ll review it in full soon, but for now will say that it does actually have a bear in it, and is based on a true story.

I’m pleased with myself for going from Wintering (via various other ice, snow and winter references) to a “Summer” title. We’ve crossed the hemispheres from Kate’s Australian winter to summertime here.

Where will your chain take you? Join us for #6Degrees of Separation! (Hosted on the first Saturday of each month by Kate W. of Books Are My Favourite and Best.) Next month’s starting point will be the recent winner of the Women’s Prize, The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki.

Have you read any of my selections? Tempted by any you didn’t know before?

Departure(s) by Julian Barnes [20 Jan., Vintage (Penguin) / Knopf]: (Currently reading) I get more out of rereading Barnes’s classics than reading his latest stuff, but I’ll still attempt anything he publishes. He’s 80 and calls this his last book. So far, it’s heavily about memory. “Julian played matchmaker to Stephen and Jean, friends he met at university in the 1960s; as the third wheel, he was deeply invested in the success of their love”. Sounds way too similar to 1991’s Talking It Over, and the early pages have been tedious. (Review copy from publisher)

Departure(s) by Julian Barnes [20 Jan., Vintage (Penguin) / Knopf]: (Currently reading) I get more out of rereading Barnes’s classics than reading his latest stuff, but I’ll still attempt anything he publishes. He’s 80 and calls this his last book. So far, it’s heavily about memory. “Julian played matchmaker to Stephen and Jean, friends he met at university in the 1960s; as the third wheel, he was deeply invested in the success of their love”. Sounds way too similar to 1991’s Talking It Over, and the early pages have been tedious. (Review copy from publisher) Our Better Natures by Sophie Ward [5 Feb., Corsair]: I loved Ward’s Booker-longlisted

Our Better Natures by Sophie Ward [5 Feb., Corsair]: I loved Ward’s Booker-longlisted  Almost Life by Kiran Millwood Hargrave [12 March, Picador / March 24, S&S/Summit Books]: There have often been queer undertones in Hargrave’s work, but this David Nicholls-esque plot sounds like her most overt. “Erica and Laure meet on the steps of the Sacré-Cœur in Paris, 1978. … The moment the two women meet the spark is undeniable. But their encounter turns into far more than a summer of love. It is the beginning of a relationship that will define their lives and every decision they have yet to make.” (Edelweiss download)

Almost Life by Kiran Millwood Hargrave [12 March, Picador / March 24, S&S/Summit Books]: There have often been queer undertones in Hargrave’s work, but this David Nicholls-esque plot sounds like her most overt. “Erica and Laure meet on the steps of the Sacré-Cœur in Paris, 1978. … The moment the two women meet the spark is undeniable. But their encounter turns into far more than a summer of love. It is the beginning of a relationship that will define their lives and every decision they have yet to make.” (Edelweiss download) Patient, Female: Stories by Julie Schumacher [May 5, Milkweed Editions]: I found out about this via a webinar with Milkweed and a couple of other U.S. indie publishers. I loved Schumacher’s Dear Committee Members. “[T]his irreverent collection … balances sorrow against laughter. … Each protagonist—ranging from girlhood to senescence—receives her own indelible voice as she navigates social blunders, generational misunderstandings, and the absurdity of the human experience.” The publicist likened the tone to Meg Wolitzer.

Patient, Female: Stories by Julie Schumacher [May 5, Milkweed Editions]: I found out about this via a webinar with Milkweed and a couple of other U.S. indie publishers. I loved Schumacher’s Dear Committee Members. “[T]his irreverent collection … balances sorrow against laughter. … Each protagonist—ranging from girlhood to senescence—receives her own indelible voice as she navigates social blunders, generational misunderstandings, and the absurdity of the human experience.” The publicist likened the tone to Meg Wolitzer. The Things We Never Say by Elizabeth Strout [7 May, Viking (Penguin) / May 5, Random House]: Hurrah for moving on from Lucy Barton at last! “Artie Dam is living a double life. He spends his days teaching history to eleventh graders … and, on weekends, takes his sailboat out on the beautiful Massachusetts Bay. … [O]ne day, Artie learns that life has been keeping a secret from him, one that threatens to upend his entire world. … [This] takes one man’s fears and loneliness and makes them universal.”

The Things We Never Say by Elizabeth Strout [7 May, Viking (Penguin) / May 5, Random House]: Hurrah for moving on from Lucy Barton at last! “Artie Dam is living a double life. He spends his days teaching history to eleventh graders … and, on weekends, takes his sailboat out on the beautiful Massachusetts Bay. … [O]ne day, Artie learns that life has been keeping a secret from him, one that threatens to upend his entire world. … [This] takes one man’s fears and loneliness and makes them universal.” Hunger and Thirst by Claire Fuller [7 May, Penguin / June 2, Tin House]: I’ve read everything of Fuller’s and hope this will reverse the worsening trend of her novels, though true crime is overdone. “1987: After a childhood trauma and years in and out of the care system, sixteen-year-old Ursula … is invited to join a squat at The Underwood. … Thirty-six years later, Ursula is a renowned, reclusive sculptor living under a pseudonym in London when her identity is exposed by true-crime documentary-maker.” (Edelweiss download)

Hunger and Thirst by Claire Fuller [7 May, Penguin / June 2, Tin House]: I’ve read everything of Fuller’s and hope this will reverse the worsening trend of her novels, though true crime is overdone. “1987: After a childhood trauma and years in and out of the care system, sixteen-year-old Ursula … is invited to join a squat at The Underwood. … Thirty-six years later, Ursula is a renowned, reclusive sculptor living under a pseudonym in London when her identity is exposed by true-crime documentary-maker.” (Edelweiss download) Little Vanities by Sarah Gilmartin [21 May, ONE (Pushkin)]: Gilmartin’s Service was great. “Dylan, Stevie and Ben have been inseparable since their days at Trinity, when everything seemed possible. … Two decades on, … Dylan, once a rugby star, is stranded on the sofa, cared for by his wife Rachel. Across town, Stevie and Ben’s relationship has settled into weary routine. Then, after countless auditions, Ben lands a role in Pinter’s Betrayal. As rehearsals unfold, the play’s shifting allegiances seep into reality, reviving old jealousies and awakening sudden longings.”

Little Vanities by Sarah Gilmartin [21 May, ONE (Pushkin)]: Gilmartin’s Service was great. “Dylan, Stevie and Ben have been inseparable since their days at Trinity, when everything seemed possible. … Two decades on, … Dylan, once a rugby star, is stranded on the sofa, cared for by his wife Rachel. Across town, Stevie and Ben’s relationship has settled into weary routine. Then, after countless auditions, Ben lands a role in Pinter’s Betrayal. As rehearsals unfold, the play’s shifting allegiances seep into reality, reviving old jealousies and awakening sudden longings.” Said the Dead by Doireann Ní Ghríofa [21 May, Faber / Sept. 22, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: A Ghost in the Throat was brilliant and this sounds right up my street. “In the city of Cork, a derelict Victorian mental hospital is being converted into modern apartments. One passerby has always flinched as she passes the place. Had her birth occurred in another decade, she too might have lived within those walls. Now, … she finds herself drawn into an irresistible river of forgotten voices”.

Said the Dead by Doireann Ní Ghríofa [21 May, Faber / Sept. 22, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: A Ghost in the Throat was brilliant and this sounds right up my street. “In the city of Cork, a derelict Victorian mental hospital is being converted into modern apartments. One passerby has always flinched as she passes the place. Had her birth occurred in another decade, she too might have lived within those walls. Now, … she finds herself drawn into an irresistible river of forgotten voices”. Land by Maggie O’Farrell [2 June, Tinder Press / Knopf]: I haven’t fully loved O’Farrell’s shift into historical fiction, but I’m still willing to give this a go. “On a windswept peninsula stretching out into the Atlantic, Tomás and his reluctant son, Liam [age 10], are working for the great Ordnance Survey project to map the whole of Ireland. The year is 1865, and in a country not long since ravaged and emptied by the Great Hunger, the task is not an easy one.” (Edelweiss download)

Land by Maggie O’Farrell [2 June, Tinder Press / Knopf]: I haven’t fully loved O’Farrell’s shift into historical fiction, but I’m still willing to give this a go. “On a windswept peninsula stretching out into the Atlantic, Tomás and his reluctant son, Liam [age 10], are working for the great Ordnance Survey project to map the whole of Ireland. The year is 1865, and in a country not long since ravaged and emptied by the Great Hunger, the task is not an easy one.” (Edelweiss download) Returns and Exchanges by Kayla Rae Whitaker [2 June, Scribe / May 19, Random House]: Whitaker’s The Animators is one of my favourite novels that hardly anyone else has ever heard of. “A sweeping novel of one [discount department store-owning] Kentucky family’s rise and fall throughout the 1980s—a tragicomic tour de force about love and marriage, parents and [their four] children, and the perils of mixing family with business”. (Edelweiss download)

Returns and Exchanges by Kayla Rae Whitaker [2 June, Scribe / May 19, Random House]: Whitaker’s The Animators is one of my favourite novels that hardly anyone else has ever heard of. “A sweeping novel of one [discount department store-owning] Kentucky family’s rise and fall throughout the 1980s—a tragicomic tour de force about love and marriage, parents and [their four] children, and the perils of mixing family with business”. (Edelweiss download) The Great Wherever by Shannon Sanders [9 July, Viking (Penguin) / July 7, Henry Holt]: Sanders’s linked story collection Company left me keen to follow her career. Aubrey Lamb, 32, is “grieving the recent loss of her father and the end of a relationship.” She leaves Washington, DC for her Black family’s ancestral Tennessee farm. “But the land proves to be a burdensome inheritance … [and] the ghosts of her ancestors interject with their own exasperated, gossipy commentary on the flaws and foibles of relatives living and dead”. (Edelweiss download)

The Great Wherever by Shannon Sanders [9 July, Viking (Penguin) / July 7, Henry Holt]: Sanders’s linked story collection Company left me keen to follow her career. Aubrey Lamb, 32, is “grieving the recent loss of her father and the end of a relationship.” She leaves Washington, DC for her Black family’s ancestral Tennessee farm. “But the land proves to be a burdensome inheritance … [and] the ghosts of her ancestors interject with their own exasperated, gossipy commentary on the flaws and foibles of relatives living and dead”. (Edelweiss download) Country People by Daniel Mason [14 July, John Murray / July 7, Random House]: It doesn’t seem long enough since North Woods for there to be another Mason novel, but never mind. “Miles Krzelewski is … twelve years late with his PhD on Russian folktales … [W]hen his wife Kate accepts a visiting professorship at a prestigious college in the far away forests of Vermont, he decides that this will be his year to finally move forward with his life. … [A] luminous exploration of marriage and parenthood, the nature of belief and the power of stories, and the ways in which we find connection in an increasingly fragmented world.”

Country People by Daniel Mason [14 July, John Murray / July 7, Random House]: It doesn’t seem long enough since North Woods for there to be another Mason novel, but never mind. “Miles Krzelewski is … twelve years late with his PhD on Russian folktales … [W]hen his wife Kate accepts a visiting professorship at a prestigious college in the far away forests of Vermont, he decides that this will be his year to finally move forward with his life. … [A] luminous exploration of marriage and parenthood, the nature of belief and the power of stories, and the ways in which we find connection in an increasingly fragmented world.” It Will Come Back to You: Collected Stories by Sigrid Nunez [14 July, Virago / Riverhead]: Nunez is one of my favourite authors but I never knew she’d written short stories. The blurb reveals very little about them! “Carefully selected from three decades of work … Moving from the momentous to the mundane, Nunez maintains her irrepressible humor, bite, and insight, her expert balance between intimacy and universality, gravity and levity, all while entertainingly probing the philosophical questions we have come to expect, such as: How can we withstand the passage of time? Is memory the greatest fiction?” (Edelweiss download)

It Will Come Back to You: Collected Stories by Sigrid Nunez [14 July, Virago / Riverhead]: Nunez is one of my favourite authors but I never knew she’d written short stories. The blurb reveals very little about them! “Carefully selected from three decades of work … Moving from the momentous to the mundane, Nunez maintains her irrepressible humor, bite, and insight, her expert balance between intimacy and universality, gravity and levity, all while entertainingly probing the philosophical questions we have come to expect, such as: How can we withstand the passage of time? Is memory the greatest fiction?” (Edelweiss download) Exit Party by Emily St. John Mandel [17 Sept., Picador / Sept. 15, Knopf]: The synopsis sounds a bit meh, but in my eyes Mandel can do no wrong. “2031. America is at war with itself, but for the first time in weeks there is some good news: the Republic of California has been declared, the curfew in Los Angeles is lifted, and everyone in the city is going to a party. Ari, newly released from prison, arrives with her friend Gloria … Years later, living a different life in Paris, Ari remains haunted by that night.”

Exit Party by Emily St. John Mandel [17 Sept., Picador / Sept. 15, Knopf]: The synopsis sounds a bit meh, but in my eyes Mandel can do no wrong. “2031. America is at war with itself, but for the first time in weeks there is some good news: the Republic of California has been declared, the curfew in Los Angeles is lifted, and everyone in the city is going to a party. Ari, newly released from prison, arrives with her friend Gloria … Years later, living a different life in Paris, Ari remains haunted by that night.” Black Bear: A Story of Siblinghood and Survival by Trina Moyles [Jan. 6, Pegasus Books]: Out now! “When Trina Moyles was five years old, her father … brought home an orphaned black bear cub for a night before sending it to the Calgary Zoo. … After years of working for human rights organizations, Trina returned to northern Alberta for a job as a fire tower lookout, while [her brother] Brendan worked in the oil sands … Over four summers, Trina begins to move beyond fear and observe the extraordinary essence of the maligned black bear”. (For BookBrowse review) (Review e-copy)

Black Bear: A Story of Siblinghood and Survival by Trina Moyles [Jan. 6, Pegasus Books]: Out now! “When Trina Moyles was five years old, her father … brought home an orphaned black bear cub for a night before sending it to the Calgary Zoo. … After years of working for human rights organizations, Trina returned to northern Alberta for a job as a fire tower lookout, while [her brother] Brendan worked in the oil sands … Over four summers, Trina begins to move beyond fear and observe the extraordinary essence of the maligned black bear”. (For BookBrowse review) (Review e-copy) Moveable Feasts: A Story of Paris in Twenty Meals by Chris Newens [Feb. 3, Pegasus Books; came out in the UK in July 2025 but somehow I missed it!]: I’m a sucker for foodie books and Paris books. A “long-time resident of the historic slaughterhouse quartier Villette takes us on a delightful gastronomic journey around Paris … From Congolese catfish in the 18th to Middle Eastern falafels in the 4th, to the charcuterie served at the libertine nightclubs of Pigalle in the 9th, Newens lifts the lid on the city’s ever-changing, defining, and irresistible food culture.” (Edelweiss download)

Moveable Feasts: A Story of Paris in Twenty Meals by Chris Newens [Feb. 3, Pegasus Books; came out in the UK in July 2025 but somehow I missed it!]: I’m a sucker for foodie books and Paris books. A “long-time resident of the historic slaughterhouse quartier Villette takes us on a delightful gastronomic journey around Paris … From Congolese catfish in the 18th to Middle Eastern falafels in the 4th, to the charcuterie served at the libertine nightclubs of Pigalle in the 9th, Newens lifts the lid on the city’s ever-changing, defining, and irresistible food culture.” (Edelweiss download) Frog: And Other Essays by Anne Fadiman [Feb. 10, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Fadiman publishes rarely, and it can be difficult to get hold of her books, but they are always worth it. “Ranging in subject matter from her deceased frog, to archaic printer technology, to the fraught relationship between Samuel Taylor Coleridge and his son Hartley, these essays unlock a whole world—one overflowing with mundanity and oddity—through sly observation and brilliant wit.”

Frog: And Other Essays by Anne Fadiman [Feb. 10, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Fadiman publishes rarely, and it can be difficult to get hold of her books, but they are always worth it. “Ranging in subject matter from her deceased frog, to archaic printer technology, to the fraught relationship between Samuel Taylor Coleridge and his son Hartley, these essays unlock a whole world—one overflowing with mundanity and oddity—through sly observation and brilliant wit.” The Beginning Comes after the End: Notes on a World of Change by Rebecca Solnit [March 3, Haymarket Books]: A sequel to Hope in the Dark. Hope is a critically endangered species these days, but Solnit has her eyes open. “While the white nationalist and authoritarian backlash drives individualism and isolation, this new world embraces antiracism, feminism, a more expansive understanding of gender, environmental thinking, scientific breakthroughs, and Indigenous and non-Western ideas, pointing toward a more interconnected, relational world.” (Edelweiss download)

The Beginning Comes after the End: Notes on a World of Change by Rebecca Solnit [March 3, Haymarket Books]: A sequel to Hope in the Dark. Hope is a critically endangered species these days, but Solnit has her eyes open. “While the white nationalist and authoritarian backlash drives individualism and isolation, this new world embraces antiracism, feminism, a more expansive understanding of gender, environmental thinking, scientific breakthroughs, and Indigenous and non-Western ideas, pointing toward a more interconnected, relational world.” (Edelweiss download) Jan Morris: A Life by Sara Wheeler [7 April, Faber / April 14, Harper]: I didn’t get on with the mammoth biography Paul Clements published in 2022 – it was dry and conventional; entirely unfitting for Morris – but hope for better things from a fellow female travel writer. “Wheeler uncovers the complexity of this twentieth-century icon … Drawing on unprecedented access to Morris’s papers as well as interviews with family, friends and colleagues, Wheeler assembles a captivating … story of longing, traveling and never reaching home.” (Edelweiss download)

Jan Morris: A Life by Sara Wheeler [7 April, Faber / April 14, Harper]: I didn’t get on with the mammoth biography Paul Clements published in 2022 – it was dry and conventional; entirely unfitting for Morris – but hope for better things from a fellow female travel writer. “Wheeler uncovers the complexity of this twentieth-century icon … Drawing on unprecedented access to Morris’s papers as well as interviews with family, friends and colleagues, Wheeler assembles a captivating … story of longing, traveling and never reaching home.” (Edelweiss download)

This posthumous novella was written in the 1940s but never published in Brennan’s lifetime. From Dublin, she was a longtime New Yorker staff member and wrote acclaimed short stories. After her mother’s death, Anastasia King travels from Paris, where the two set up residence after leaving her father, to Ireland to stay in the family home with her grandmother. Anastasia considers it a return, a homecoming, but her spiteful grandmother makes it clear that she is an unwelcome interloper. Mrs King can’t forgive the wrong done to her son, and so won’t countenance Anastasia’s plan to repatriate her mother’s remains. Rejection and despair eat away at Anastasia’s mental health (“She saw the miserable gate of her defeat already open ahead. There only remained for her to come up to it and pass through it and be done with it”) but she pulls herself together for an act of defiance. Most affecting for me was a scene in which we learn that Anastasia is so absorbed in her own drama that she does not fulfill the simple last wish of a dying friend. This brought to mind James Joyce’s The Dead. (Secondhand purchase – The Bookshop, Wigtown) [81 pages]

This posthumous novella was written in the 1940s but never published in Brennan’s lifetime. From Dublin, she was a longtime New Yorker staff member and wrote acclaimed short stories. After her mother’s death, Anastasia King travels from Paris, where the two set up residence after leaving her father, to Ireland to stay in the family home with her grandmother. Anastasia considers it a return, a homecoming, but her spiteful grandmother makes it clear that she is an unwelcome interloper. Mrs King can’t forgive the wrong done to her son, and so won’t countenance Anastasia’s plan to repatriate her mother’s remains. Rejection and despair eat away at Anastasia’s mental health (“She saw the miserable gate of her defeat already open ahead. There only remained for her to come up to it and pass through it and be done with it”) but she pulls herself together for an act of defiance. Most affecting for me was a scene in which we learn that Anastasia is so absorbed in her own drama that she does not fulfill the simple last wish of a dying friend. This brought to mind James Joyce’s The Dead. (Secondhand purchase – The Bookshop, Wigtown) [81 pages]

If you’ve heard of this, it’ll be for the fact that the main character – Lou, a librarian sent to archive the holdings of an octagonal house on an island one summer – has sex with a bear. That makes it sound much more repulsive and/or titillating than it actually is. The further I read the more I started to think of it as an allegory for women’s awakening; perhaps the strategy inspired Melissa Broder’s

If you’ve heard of this, it’ll be for the fact that the main character – Lou, a librarian sent to archive the holdings of an octagonal house on an island one summer – has sex with a bear. That makes it sound much more repulsive and/or titillating than it actually is. The further I read the more I started to think of it as an allegory for women’s awakening; perhaps the strategy inspired Melissa Broder’s  Several of us reviewed this for #NovNov though unsure it counts: in the UK the title story (originally for the New Yorker) was published in a standalone volume by Faber, while the U.S. release includes two additional earlier stories; I read the latter. The title story has Cathal spending what should have been his wedding weekend moping about Sabine calling off their engagement at the last minute. It’s no mystery why she did: his misogyny, though not overt, runs deep, most evident in the terms in which he thinks about women. And where did he learn it? From his father. (“The Long and Painful Death” is from Keegan’s second collection, Walk the Blue Fields, and concerns a woman on a writing residency at an author’s historic house in Ireland. She makes a stand for her own work by refusing to cede place to an entitled male scholar. The final story is “Antarctica,” the lead story in that 1999 volume and a really terrific one I’d already experienced before. It’s as dark and surprising as an early Ian McEwan novel.) Keegan proves, as ever, to be a master at portraying emotions and relationships, but the one story is admittedly slight on its own, and its point obvious. (Read via Edelweiss) [64 pages]

Several of us reviewed this for #NovNov though unsure it counts: in the UK the title story (originally for the New Yorker) was published in a standalone volume by Faber, while the U.S. release includes two additional earlier stories; I read the latter. The title story has Cathal spending what should have been his wedding weekend moping about Sabine calling off their engagement at the last minute. It’s no mystery why she did: his misogyny, though not overt, runs deep, most evident in the terms in which he thinks about women. And where did he learn it? From his father. (“The Long and Painful Death” is from Keegan’s second collection, Walk the Blue Fields, and concerns a woman on a writing residency at an author’s historic house in Ireland. She makes a stand for her own work by refusing to cede place to an entitled male scholar. The final story is “Antarctica,” the lead story in that 1999 volume and a really terrific one I’d already experienced before. It’s as dark and surprising as an early Ian McEwan novel.) Keegan proves, as ever, to be a master at portraying emotions and relationships, but the one story is admittedly slight on its own, and its point obvious. (Read via Edelweiss) [64 pages]  “She is Europe’s eerie child, and she is part of the storm.” J.K. is a young woman who totes her typewriter around different European locations, sleeps with various boyfriends, hears strangers’ stories, and so on. Many of the people she meets are only designated by an initial. By contrast, the most fully realized character is her mother, Lillian Strauss. The chapters feel unconnected and the encounters within them random, building to nothing. Though a bit like

“She is Europe’s eerie child, and she is part of the storm.” J.K. is a young woman who totes her typewriter around different European locations, sleeps with various boyfriends, hears strangers’ stories, and so on. Many of the people she meets are only designated by an initial. By contrast, the most fully realized character is her mother, Lillian Strauss. The chapters feel unconnected and the encounters within them random, building to nothing. Though a bit like

Meier is a cemetery tour guide in Brooklyn, where she lives. She surveys American burial customs in particular, noting the lack of respect for Black and Native American burial grounds, the Civil War-era history of embalming, the increasing popularity of cremation, and the rise of garden cemeteries such as Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which can serve as wildlife havens. The mass casualties and fear of infection associated with Covid-19 brought back memories of the AIDS epidemic, especially for those in New York City. Meier travels to a wide range of resting places, from potter’s fields for unclaimed bodies to the most manicured cemeteries. She also talks about newer options such as green burial, body composting, and the many memorial objects ashes can be turned into. I’m a dedicated reader of books about death and so found this fascinating, with the perfect respectful and just-shy-of-melancholy tone. It’s political and philosophical in equal measures. (Read via NetGalley) [168 pages]

Meier is a cemetery tour guide in Brooklyn, where she lives. She surveys American burial customs in particular, noting the lack of respect for Black and Native American burial grounds, the Civil War-era history of embalming, the increasing popularity of cremation, and the rise of garden cemeteries such as Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which can serve as wildlife havens. The mass casualties and fear of infection associated with Covid-19 brought back memories of the AIDS epidemic, especially for those in New York City. Meier travels to a wide range of resting places, from potter’s fields for unclaimed bodies to the most manicured cemeteries. She also talks about newer options such as green burial, body composting, and the many memorial objects ashes can be turned into. I’m a dedicated reader of books about death and so found this fascinating, with the perfect respectful and just-shy-of-melancholy tone. It’s political and philosophical in equal measures. (Read via NetGalley) [168 pages]

Laboratory pregnancy tests have been available since the 1930s and home pregnancy tests – the focus here – since the 1970s. All of them work by testing urine for the hormone hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin). What is truly wild is that pregnancy used to be verifiable only with laboratory animals – female mice and rabbits had to be sacrificed to see if their ovaries had swelled after the injection of a woman’s urine; later, female Xenopus toads were found to lay eggs in response, so didn’t need to be killed. Home pregnancy kits were controversial and available in Canada before the USA because it was thought that they could be unreliable or that they would encourage early abortions. Weingarten brings together the history, laypeople-friendly science, and cultural representations (taking a pregnancy test is excellent TV shorthand) in a readable narrative and makes a clear feminist statement: “the home pregnancy test gave back to women what should have always been theirs: first-hand knowledge about how their bodies worked” and thus “had the potential to upend a paternalistic culture.” (Read via NetGalley) [160 pages]

Laboratory pregnancy tests have been available since the 1930s and home pregnancy tests – the focus here – since the 1970s. All of them work by testing urine for the hormone hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin). What is truly wild is that pregnancy used to be verifiable only with laboratory animals – female mice and rabbits had to be sacrificed to see if their ovaries had swelled after the injection of a woman’s urine; later, female Xenopus toads were found to lay eggs in response, so didn’t need to be killed. Home pregnancy kits were controversial and available in Canada before the USA because it was thought that they could be unreliable or that they would encourage early abortions. Weingarten brings together the history, laypeople-friendly science, and cultural representations (taking a pregnancy test is excellent TV shorthand) in a readable narrative and makes a clear feminist statement: “the home pregnancy test gave back to women what should have always been theirs: first-hand knowledge about how their bodies worked” and thus “had the potential to upend a paternalistic culture.” (Read via NetGalley) [160 pages]  The dc Talk album Jesus Freak (1995) is the first CD I ever owned. My best friend and I listened to it (along with Bloom by Audio Adrenaline and Take Me to Your Leader by Newsboys) so many times that we knew every word and note by heart. So it’s hard for me to be objective rather than nostalgic; I was intrigued to see what two secular academics would have to say. Crucially, they were teenage dc Talk fans, now ex-Evangelicals and homosexual partners. As English professors, their approach is to spot musical influences (Nirvana on the title track; R&B and gospel elsewhere), critically analyse lyrics (with “Colored People” proving problematic for its “neoliberal multiculturalism and its potential for post-racial utopianism”), and put a queer spin on things. For those who don’t know, dc Talk were essentially a boy band with three singers, one Black and two white – one of these a rapper. Stockton and Gilson chronicle the confusion of living with a same-sex attraction they couldn’t express as teens, and cheekily suggest there may have been something going on between dc Talk members Toby McKeehan and Michael Tait, who were roommates at Liberty University and apparently dismantled their bunk beds so they could sleep side by side. Hmmm! I was interested enough in the subject matter to overlook the humanities jargon. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year) [132 pages]

The dc Talk album Jesus Freak (1995) is the first CD I ever owned. My best friend and I listened to it (along with Bloom by Audio Adrenaline and Take Me to Your Leader by Newsboys) so many times that we knew every word and note by heart. So it’s hard for me to be objective rather than nostalgic; I was intrigued to see what two secular academics would have to say. Crucially, they were teenage dc Talk fans, now ex-Evangelicals and homosexual partners. As English professors, their approach is to spot musical influences (Nirvana on the title track; R&B and gospel elsewhere), critically analyse lyrics (with “Colored People” proving problematic for its “neoliberal multiculturalism and its potential for post-racial utopianism”), and put a queer spin on things. For those who don’t know, dc Talk were essentially a boy band with three singers, one Black and two white – one of these a rapper. Stockton and Gilson chronicle the confusion of living with a same-sex attraction they couldn’t express as teens, and cheekily suggest there may have been something going on between dc Talk members Toby McKeehan and Michael Tait, who were roommates at Liberty University and apparently dismantled their bunk beds so they could sleep side by side. Hmmm! I was interested enough in the subject matter to overlook the humanities jargon. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year) [132 pages]

Grumbach died last year at age 104. This was my third of her books; I read two previous memoirs,

Grumbach died last year at age 104. This was my third of her books; I read two previous memoirs,  It feels like I made an error by reading Levy’s “Living Autobiography,” out of order. I picked up the middle volume of the trilogy, The Cost of Living, for #NovNov in 2021 and it ended up being my favourite nonfiction read of that year. I then read part of the third book, Real Estate, last year but set it aside. And now I’ve read the first because it was the shortest. It’s loosely structured around George Orwell’s four reasons for writing: political purpose, historical impulse, sheer egoism and aesthetic enthusiasm. The frame story has her flying to Majorca at a time when she was struggling with her mental health. She vaguely follows in the footsteps of George Sand and then pauses to tell a Chinese shopkeeper the story of her upbringing in apartheid-era South Africa and the family’s move to London. Although I generally admire recreations of childhood and there are some strong pen portraits of minor characters, overall there was little that captivated me here and I was too aware of the writerly shaping. (Secondhand purchase – 2nd & Charles, Hagerstown) [111 pages]

It feels like I made an error by reading Levy’s “Living Autobiography,” out of order. I picked up the middle volume of the trilogy, The Cost of Living, for #NovNov in 2021 and it ended up being my favourite nonfiction read of that year. I then read part of the third book, Real Estate, last year but set it aside. And now I’ve read the first because it was the shortest. It’s loosely structured around George Orwell’s four reasons for writing: political purpose, historical impulse, sheer egoism and aesthetic enthusiasm. The frame story has her flying to Majorca at a time when she was struggling with her mental health. She vaguely follows in the footsteps of George Sand and then pauses to tell a Chinese shopkeeper the story of her upbringing in apartheid-era South Africa and the family’s move to London. Although I generally admire recreations of childhood and there are some strong pen portraits of minor characters, overall there was little that captivated me here and I was too aware of the writerly shaping. (Secondhand purchase – 2nd & Charles, Hagerstown) [111 pages]  I reviewed a couple of JLS’s species-specific monographs for #NovNov in 2018:

I reviewed a couple of JLS’s species-specific monographs for #NovNov in 2018:  I’ve read so many cancer stories that it takes a lot to make one stand out. This feels like a random collection of documents rather than a coherent memoir. One of the three essays was originally a speech, and two were previously printed in another of her books. Lorde was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1978 and had a mastectomy. A Black lesbian feminist, she resisted wearing prostheses and spoke up about the potential environmental causes of breast cancer that need to be addressed in research (“I may be a casualty in the cosmic war against radiation, animal fat, air pollution, McDonald’s hamburgers and Red Dye No. 2”). Her actual journal entries make up little of the text, which is for the best because fear and pain can bring out the cliches in us – but occasionally a great quote like “if bitterness were a whetstone, I could be sharp as grief.” Another favourite line: “Pain does not mellow you, nor does it ennoble, in my experience.” I’m keen to read her memoir Zami. (University library) [77 pages]

I’ve read so many cancer stories that it takes a lot to make one stand out. This feels like a random collection of documents rather than a coherent memoir. One of the three essays was originally a speech, and two were previously printed in another of her books. Lorde was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1978 and had a mastectomy. A Black lesbian feminist, she resisted wearing prostheses and spoke up about the potential environmental causes of breast cancer that need to be addressed in research (“I may be a casualty in the cosmic war against radiation, animal fat, air pollution, McDonald’s hamburgers and Red Dye No. 2”). Her actual journal entries make up little of the text, which is for the best because fear and pain can bring out the cliches in us – but occasionally a great quote like “if bitterness were a whetstone, I could be sharp as grief.” Another favourite line: “Pain does not mellow you, nor does it ennoble, in my experience.” I’m keen to read her memoir Zami. (University library) [77 pages]  I’d not read Matar before I spotted this art book-cum-memoir and thought, why not. A Libyan American novelist who lives in London, Matar had long been fascinated by the Sienese School of painting (13th to 15th centuries), many of whose artists depicted biblical scenes or religious allegories – even though he’s not a Christian. He spent a month in Italy immersed in the art he loves; there are 15 colour reproductions here. His explications of art history are generalist enough to be accessible to all readers, but I engaged more with the glimpses into his own life. For instance, he meets a fellow Arabic speaker and they quickly form a brotherly attachment, and a Paradise scene gives him fanciful hope of being reunited with his missing father – the subject of his Folio Prize-winning memoir The Return, which I’d like to read soon. His prose is beautiful as he reflects on history, death and how memories occupy ‘rooms’ in the imagination. A little more interest in the art would have helped, though. (Little Free Library) [118 pages]

I’d not read Matar before I spotted this art book-cum-memoir and thought, why not. A Libyan American novelist who lives in London, Matar had long been fascinated by the Sienese School of painting (13th to 15th centuries), many of whose artists depicted biblical scenes or religious allegories – even though he’s not a Christian. He spent a month in Italy immersed in the art he loves; there are 15 colour reproductions here. His explications of art history are generalist enough to be accessible to all readers, but I engaged more with the glimpses into his own life. For instance, he meets a fellow Arabic speaker and they quickly form a brotherly attachment, and a Paradise scene gives him fanciful hope of being reunited with his missing father – the subject of his Folio Prize-winning memoir The Return, which I’d like to read soon. His prose is beautiful as he reflects on history, death and how memories occupy ‘rooms’ in the imagination. A little more interest in the art would have helped, though. (Little Free Library) [118 pages]

I had high hopes for this childhood memoir that originally appeared in the New Yorker and was reprinted as part of the Canongate Classics series. But I soon resorted to skimming as her recollections of her shabby upper-class upbringing in a Highlands castle are full of page after page of description and dull recounting of events, with few scenes and little dialogue. This would be of high historical value for someone wanting to understand daily life for a certain fraction of society at the time, however. When Miller’s father died, she was only 10 and they had to leave the castle. I was intrigued to learn from her bio that she lived in Newbury for a time. (Secondhand purchase – Barter Books) [98 pages]