Six Degrees of Separation: From Hamnet to Paula

I was slow off the mark this month, but here we go with everyone’s favorite book blogging meme! This time we start with Hamnet, Maggie O’Farrell’s Women’s Prize-winning novel about the death of William Shakespeare’s son. (See Kate’s opening post.) Although I didn’t love this as much as others have (my review is here), I was delighted for O’Farrell to get the well-deserved attention – Hamnet was also named the Waterstones Book of the Year 2020.

I was slow off the mark this month, but here we go with everyone’s favorite book blogging meme! This time we start with Hamnet, Maggie O’Farrell’s Women’s Prize-winning novel about the death of William Shakespeare’s son. (See Kate’s opening post.) Although I didn’t love this as much as others have (my review is here), I was delighted for O’Farrell to get the well-deserved attention – Hamnet was also named the Waterstones Book of the Year 2020.

#1 I’ve read many nonfiction accounts of bereavement. One that stands out is Notes from the Everlost by Kate Inglis, which is also about the death of a child. The author’s twin sons were born premature; one survived while the other died. Her book is about what happened next, and how bereaved parents help each other to cope. An excerpt from my TLS review is here.

#1 I’ve read many nonfiction accounts of bereavement. One that stands out is Notes from the Everlost by Kate Inglis, which is also about the death of a child. The author’s twin sons were born premature; one survived while the other died. Her book is about what happened next, and how bereaved parents help each other to cope. An excerpt from my TLS review is here.

#2 Also featuring a magpie on the cover, at least in its original hardback form, is Wakenhyrst by Michelle Paver (reviewed for R.I.P. this past October). I loved that Maud has a pet magpie named Chatterpie, and the fen setting was appealing, but I’ve been pretty underwhelmed by all three of Paver’s historical suspense novels for adults.

#2 Also featuring a magpie on the cover, at least in its original hardback form, is Wakenhyrst by Michelle Paver (reviewed for R.I.P. this past October). I loved that Maud has a pet magpie named Chatterpie, and the fen setting was appealing, but I’ve been pretty underwhelmed by all three of Paver’s historical suspense novels for adults.

#3 One of the strands in Wakenhyrst is Maud’s father’s research into a painting of the Judgment Day discovered at the local church. In A Month in the Country by J. L. Carr (reviewed last summer), a WWI veteran is commissioned to uncover a wall painting of the Judgment Day, assumed to be the work of a medieval monk and long ago whitewashed over.

#3 One of the strands in Wakenhyrst is Maud’s father’s research into a painting of the Judgment Day discovered at the local church. In A Month in the Country by J. L. Carr (reviewed last summer), a WWI veteran is commissioned to uncover a wall painting of the Judgment Day, assumed to be the work of a medieval monk and long ago whitewashed over.

#4 A Month in the Country spans one summer month. Invincible Summer by Alice Adams, about four Bristol University friends who navigate the highs and lows of life in the 20 years following their graduation, checks in on the characters nearly every summer. I found it clichéd; not one of the better group-of-friends novels. (My review for The Bookbag is here.)

#4 A Month in the Country spans one summer month. Invincible Summer by Alice Adams, about four Bristol University friends who navigate the highs and lows of life in the 20 years following their graduation, checks in on the characters nearly every summer. I found it clichéd; not one of the better group-of-friends novels. (My review for The Bookbag is here.)

#5 The title of Invincible Summer comes from an Albert Camus quote: “In the midst of winter, I found there was, within me, an invincible summer. And that makes me happy.” Inspired by the same quotation, then, is In the Midst of Winter by Isabel Allende, a recent novel of hers that I was drawn to for the seasonal link but couldn’t get through.

#5 The title of Invincible Summer comes from an Albert Camus quote: “In the midst of winter, I found there was, within me, an invincible summer. And that makes me happy.” Inspired by the same quotation, then, is In the Midst of Winter by Isabel Allende, a recent novel of hers that I was drawn to for the seasonal link but couldn’t get through.

#6 However, I’ve enjoyed a number of Allende books over the last 12 years or so, both fiction and non-. One of these was Paula, a memoir sparked by her twentysomething daughter’s untimely death in the early 1990s from complications due to the genetic condition porphyria. Allende told her life story in the form of a letter composed at Paula’s bedside while she was in a coma.

#6 However, I’ve enjoyed a number of Allende books over the last 12 years or so, both fiction and non-. One of these was Paula, a memoir sparked by her twentysomething daughter’s untimely death in the early 1990s from complications due to the genetic condition porphyria. Allende told her life story in the form of a letter composed at Paula’s bedside while she was in a coma.

So, I’ve come full circle with another story of the death of a child, but there’s a welcome glimpse of the summer somewhere there in the middle. May you find your own inner summer to get you through this lockdown winter.

Join us for #6Degrees of Separation! (Hosted on the first Saturday of each month by Kate W. of Books Are My Favourite and Best.) Next month’s starting point is Redhead at the Side of the Road by Anne Tyler.

Have you read any of my selections? Are you tempted by any you didn’t know before?

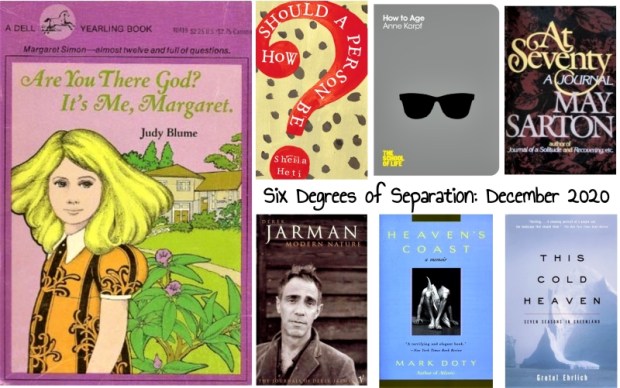

Six Degrees of Separation: From Margaret to This Cold Heaven

This month we’re starting with Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret (which I have punctuated appropriately!). See Kate’s opening post. I know I read this as a child, but other Judy Blume novels were more meaningful for me since I was a tomboy and late bloomer. The only line that stays with me is the chant “We must, we must, we must increase our bust!”

#1 Another book with a question in the title (and dominating the cover) is How Should a Person Be? by Sheila Heti. I found a hardback copy in the unofficial Little Free Library I ran in our neighborhood during the first lockdown before the public library reopened. Heti is a divisive author, but I loved Motherhood for perfectly encapsulating my situation. I think this one, too, is autofiction, and the title question is one I ask myself variations on frequently.

#1 Another book with a question in the title (and dominating the cover) is How Should a Person Be? by Sheila Heti. I found a hardback copy in the unofficial Little Free Library I ran in our neighborhood during the first lockdown before the public library reopened. Heti is a divisive author, but I loved Motherhood for perfectly encapsulating my situation. I think this one, too, is autofiction, and the title question is one I ask myself variations on frequently.

#2 I’ve read quite a few “How to” books, whether straightforward explanatory/self-help texts or not. Lots happened to be from the School of Life series. One I found particularly enjoyable and helpful was How to Age by Anne Karpf. She writes frankly about bodily degeneration, the pursuit of wisdom, and preparation for death. “Growth and psychological development aren’t a property of our earliest years but can continue throughout the life cycle.”

#2 I’ve read quite a few “How to” books, whether straightforward explanatory/self-help texts or not. Lots happened to be from the School of Life series. One I found particularly enjoyable and helpful was How to Age by Anne Karpf. She writes frankly about bodily degeneration, the pursuit of wisdom, and preparation for death. “Growth and psychological development aren’t a property of our earliest years but can continue throughout the life cycle.”

#3 Ageing is a major element in May Sarton’s journals, particularly as she moves from her seventies into her eighties and fights illnesses. I’ve read all but one of her autobiographical works now, and – while my favorite is Journal of a Solitude – the one I’ve chosen as most representative of her usual themes, including inspiration, camaraderie, the pressures of the writing life, and old age, is At Seventy.

#3 Ageing is a major element in May Sarton’s journals, particularly as she moves from her seventies into her eighties and fights illnesses. I’ve read all but one of her autobiographical works now, and – while my favorite is Journal of a Solitude – the one I’ve chosen as most representative of her usual themes, including inspiration, camaraderie, the pressures of the writing life, and old age, is At Seventy.

#4 Sarton was a keen gardener, as was Derek Jarman. I learned about him in the context of nature helping people come to terms with their mortality. Modern Nature reproduces the journal the gay, HIV-positive filmmaker kept in 1989–90. Prospect Cottage in Dungeness, Kent, and the unusual garden he cultivated there, was his refuge between trips to London and further afield, and a mental sanctuary when he was marooned in the hospital.

#4 Sarton was a keen gardener, as was Derek Jarman. I learned about him in the context of nature helping people come to terms with their mortality. Modern Nature reproduces the journal the gay, HIV-positive filmmaker kept in 1989–90. Prospect Cottage in Dungeness, Kent, and the unusual garden he cultivated there, was his refuge between trips to London and further afield, and a mental sanctuary when he was marooned in the hospital.

#5 One of the first memoirs I ever read and loved was Heaven’s Coast by Mark Doty, about his partner Wally’s death from AIDS. This sparked my continuing interest in illness and bereavement narratives, and it was through following up Doty’s memoirs with his collections of poems that I first got into contemporary poetry, so he’s had a major influence on my taste. I’ve had Heaven’s Coast on my rereading shelf for ages, so really must get to it in 2021.

#5 One of the first memoirs I ever read and loved was Heaven’s Coast by Mark Doty, about his partner Wally’s death from AIDS. This sparked my continuing interest in illness and bereavement narratives, and it was through following up Doty’s memoirs with his collections of poems that I first got into contemporary poetry, so he’s had a major influence on my taste. I’ve had Heaven’s Coast on my rereading shelf for ages, so really must get to it in 2021.

#6 Thinking of heaven, a nice loop back to Blume’s Margaret and her determination to find God … one of the finest travel books I’ve read is This Cold Heaven, about Gretel Ehrlich’s expeditions to Greenland and historical precursors who explored it. Even more than her intrepid wanderings, I was impressed by her prose, which made the icy scenery new every time. “Part jewel, part eye, part lighthouse, part recumbent monolith, the ice is a bright spot on the upper tier of the globe where the world’s purse strings have been pulled tight.”

#6 Thinking of heaven, a nice loop back to Blume’s Margaret and her determination to find God … one of the finest travel books I’ve read is This Cold Heaven, about Gretel Ehrlich’s expeditions to Greenland and historical precursors who explored it. Even more than her intrepid wanderings, I was impressed by her prose, which made the icy scenery new every time. “Part jewel, part eye, part lighthouse, part recumbent monolith, the ice is a bright spot on the upper tier of the globe where the world’s purse strings have been pulled tight.”

A fitting final selection for this week’s properly chilly winter temperatures, too. I’ll be writing up my first snowy and/or holiday-themed reads of the year in a couple of weeks.

Join us for #6Degrees of Separation if you haven’t already! (Hosted on the first Saturday of each month by Kate W. of Books Are My Favourite and Best.)

Have you read any of my selections? Are you tempted by any you didn’t know before?

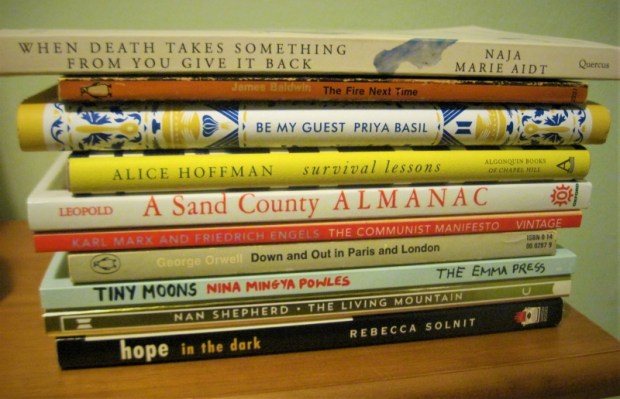

10 Favorite Nonfiction Novellas from My Shelves

What do I mean by a nonfiction novella? I’m not claiming a new genre like Truman Capote did for the nonfiction novel (so unless they’re talking about In Cold Blood or something very similar, yes, I can and do judge people who refer to a memoir as a “nonfiction novel”!); I’m referring literally to any works of nonfiction shorter than 200 pages. Many of my selections even come well under 100 pages.

I’m kicking off this nonfiction-focused week of Novellas in November with a rundown of 10 of my favorite short nonfiction works. Maybe you’ll find inspiration by seeing the wide range of subjects covered here: bereavement, social and racial justice, hospitality, cancer, nature, politics, poverty, food and mountaineering. I’d reviewed all but one of them on the blog, half of them as part of Novellas in November in various years.

When Death Takes Something from You Give It Back: Carl’s Book by Naja Marie Aidt [137 pages]: In March 2015 Aidt got word that her son Carl Emil was dead. The 25-year-old jumped out of his fifth-floor Copenhagen window after taking some mushrooms. The text is a collage of fragments: memories, dreams, dictionary definitions, journal entries, and quotations. The playful disregard for chronology and the variety of fonts, typefaces and sizes are a way of circumventing the feeling that grief has made words lose their meaning forever.

When Death Takes Something from You Give It Back: Carl’s Book by Naja Marie Aidt [137 pages]: In March 2015 Aidt got word that her son Carl Emil was dead. The 25-year-old jumped out of his fifth-floor Copenhagen window after taking some mushrooms. The text is a collage of fragments: memories, dreams, dictionary definitions, journal entries, and quotations. The playful disregard for chronology and the variety of fonts, typefaces and sizes are a way of circumventing the feeling that grief has made words lose their meaning forever.

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin [89 pages]: A hard-hitting book composed of two essays: “My Dungeon Shook,” is a letter addressed to his nephew and namesake on the 100th anniversary of emancipation; and “Down at the Cross: Letter from a Region in My Mind,” which first appeared in the New Yorker and tells of a crisis of faith that hit Baldwin when he was a teenager and started to question to what extent Christianity of all stripes was upholding white privilege. This feels completely relevant, and eminently quotable, nearly 60 years later.

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin [89 pages]: A hard-hitting book composed of two essays: “My Dungeon Shook,” is a letter addressed to his nephew and namesake on the 100th anniversary of emancipation; and “Down at the Cross: Letter from a Region in My Mind,” which first appeared in the New Yorker and tells of a crisis of faith that hit Baldwin when he was a teenager and started to question to what extent Christianity of all stripes was upholding white privilege. This feels completely relevant, and eminently quotable, nearly 60 years later.

Be My Guest: Reflections on Food, Community and the Meaning of Generosity by Priya Basil [117 pages]: A thought-provoking essay that reaches into many different topics. Part of an Indian family that has lived in Kenya and England, Basil is used to culinary abundance. However, living in Berlin increased her awareness of the suffering of the Other – hundreds of thousands of refugees have entered the EU to be met with hostility. Yet the Sikh tradition she grew up in teaches kindness to strangers. She asks how we can all cultivate a spirit of generosity.

Be My Guest: Reflections on Food, Community and the Meaning of Generosity by Priya Basil [117 pages]: A thought-provoking essay that reaches into many different topics. Part of an Indian family that has lived in Kenya and England, Basil is used to culinary abundance. However, living in Berlin increased her awareness of the suffering of the Other – hundreds of thousands of refugees have entered the EU to be met with hostility. Yet the Sikh tradition she grew up in teaches kindness to strangers. She asks how we can all cultivate a spirit of generosity.

Survival Lessons by Alice Hoffman [83 pages]: Hoffman wrote this 15 years after her own experience of breast cancer to encourage anyone going through a crisis. Each chapter title begins with the word “Choose” – a reminder that, even when you can’t choose your circumstances, you can choose your response. This has been beautifully put together with blue-tinted watercolor-effect photographs and an overall yellow and blue theme (along with deckle edge pages – a personal favorite book trait). It’s a sweet little memoir with a self-help note.

Survival Lessons by Alice Hoffman [83 pages]: Hoffman wrote this 15 years after her own experience of breast cancer to encourage anyone going through a crisis. Each chapter title begins with the word “Choose” – a reminder that, even when you can’t choose your circumstances, you can choose your response. This has been beautifully put together with blue-tinted watercolor-effect photographs and an overall yellow and blue theme (along with deckle edge pages – a personal favorite book trait). It’s a sweet little memoir with a self-help note.

A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold [92 pages]: Few know how much of our current philosophy of wilderness and the human impact on the world is indebted to Aldo Leopold. This was published in 1949, but so much rings true today: how we only appreciate wildlife if we can put an economic value on it, the troubles we get into when we eradicate predators and let prey animals run rampant, and the danger of being disconnected from the land that supplies our very life. And all this he delivers in stunning, incisive prose.

A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold [92 pages]: Few know how much of our current philosophy of wilderness and the human impact on the world is indebted to Aldo Leopold. This was published in 1949, but so much rings true today: how we only appreciate wildlife if we can put an economic value on it, the troubles we get into when we eradicate predators and let prey animals run rampant, and the danger of being disconnected from the land that supplies our very life. And all this he delivers in stunning, incisive prose.

The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels [70 pages]: Maybe you, like me, had always assumed this was an impenetrable tome of hundreds of pages? But, as I discovered when I read it on the train to Manchester some years ago, it’s very compact. That’s not to say it’s an easy read; I’ve never been politically or economically minded, so I struggled to follow the argument at times. Mostly what I appreciated was the language. Like The Origin of Species, it has many familiar lines and wonderful metaphors.

The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels [70 pages]: Maybe you, like me, had always assumed this was an impenetrable tome of hundreds of pages? But, as I discovered when I read it on the train to Manchester some years ago, it’s very compact. That’s not to say it’s an easy read; I’ve never been politically or economically minded, so I struggled to follow the argument at times. Mostly what I appreciated was the language. Like The Origin of Species, it has many familiar lines and wonderful metaphors.

Down and Out in Paris and London by George Orwell [189 pages]: Orwell’s first book, published when he was 30, is an excellent first-hand account of the working and living conditions of the poor in two world cities. He works as a dishwasher and waiter in Paris hotel restaurants for up to 80 hours a week and has to pawn his clothes to scrape together enough money to ward off starvation. Even as he’s conveying the harsh reality of exhaustion and indignity, Orwell takes a Dickensian delight in people and their eccentricities.

Down and Out in Paris and London by George Orwell [189 pages]: Orwell’s first book, published when he was 30, is an excellent first-hand account of the working and living conditions of the poor in two world cities. He works as a dishwasher and waiter in Paris hotel restaurants for up to 80 hours a week and has to pawn his clothes to scrape together enough money to ward off starvation. Even as he’s conveying the harsh reality of exhaustion and indignity, Orwell takes a Dickensian delight in people and their eccentricities.

Tiny Moons: A Year of Eating in Shanghai by Nina Mingya Powles [85 pages]: This lovely pamphlet of food-themed essays arose from a blog Powles kept while in Shanghai on a one-year scholarship to learn Mandarin. From one winter to another, she explores the city’s culinary offerings and muses on the ways in which food is bound up with her memories of people and places. This is about how food can help you be at home. I loved how she used the senses – not just taste, but also smell and sight – to recreate important places in her life.

Tiny Moons: A Year of Eating in Shanghai by Nina Mingya Powles [85 pages]: This lovely pamphlet of food-themed essays arose from a blog Powles kept while in Shanghai on a one-year scholarship to learn Mandarin. From one winter to another, she explores the city’s culinary offerings and muses on the ways in which food is bound up with her memories of people and places. This is about how food can help you be at home. I loved how she used the senses – not just taste, but also smell and sight – to recreate important places in her life.

The Living Mountain by Nan Shepherd [108 pages]: This is something of a lost nature classic. Composed during the later years of World War II but only published in 1977, it’s Shepherd’s tribute to her beloved Cairngorms, a mountain region of Scotland. But it’s not a travel or nature book in the way you might usually think of those genres. It’s a subtle, meditative, even mystical look at the forces of nature, which are majestic but also menacing. Shepherd dwells on the senses, the mountain flora and fauna, and the special quality of time and existence (what we’d today call mindfulness) achieved in a place of natural splendor and solitude.

The Living Mountain by Nan Shepherd [108 pages]: This is something of a lost nature classic. Composed during the later years of World War II but only published in 1977, it’s Shepherd’s tribute to her beloved Cairngorms, a mountain region of Scotland. But it’s not a travel or nature book in the way you might usually think of those genres. It’s a subtle, meditative, even mystical look at the forces of nature, which are majestic but also menacing. Shepherd dwells on the senses, the mountain flora and fauna, and the special quality of time and existence (what we’d today call mindfulness) achieved in a place of natural splendor and solitude.

Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities by Rebecca Solnit [143 pages]: Solnit believes in the power of purposeful individuals working towards social justice, even in the face of dispiriting evidence (e.g. the largest protests the world had seen didn’t stop the Iraq War). Instead of perfectionism, she advises flexibility and resilience; things could be even worse had we not acted. Her strong and stirring writing is a reminder that, though injustice is always with us, so is everyday heroism.

Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities by Rebecca Solnit [143 pages]: Solnit believes in the power of purposeful individuals working towards social justice, even in the face of dispiriting evidence (e.g. the largest protests the world had seen didn’t stop the Iraq War). Instead of perfectionism, she advises flexibility and resilience; things could be even worse had we not acted. Her strong and stirring writing is a reminder that, though injustice is always with us, so is everyday heroism.

Keep in touch via Twitter (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books). We’ll add any of your review links in to our master posts. Feel free to use the terrific feature image Cathy made and don’t forget the hashtag #NovNov.

Any suitably short nonfiction on your shelves?

Recommended July Releases: Donoghue, Maizes, Miller, Parikian, Trethewey

My five new releases for July include historical pandemic fiction, a fun contemporary story about a father-and-daughter burglar team, a new poetry collection from Carcanet Press, a lighthearted nature/travel book, and a poetic bereavement memoir about a violent death.

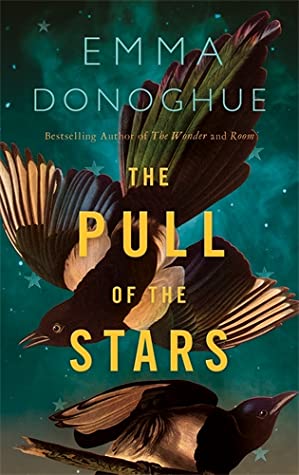

The Pull of the Stars by Emma Donoghue

Donoghue’s last two novels, The Wonder and Akin, were big hits with me. Less than a year after the contemporary-set Akin, she’s back to a historical setting – and an uncannily pertinent pandemic theme – with her latest. In 1918, Julia Power is a nurse on a Dublin maternity ward. It’s Halloween and she is about to turn 30, making her a spinster for her day; she lives with her mute, shell-shocked veteran brother, Tim, and his pet magpie.

Donoghue’s last two novels, The Wonder and Akin, were big hits with me. Less than a year after the contemporary-set Akin, she’s back to a historical setting – and an uncannily pertinent pandemic theme – with her latest. In 1918, Julia Power is a nurse on a Dublin maternity ward. It’s Halloween and she is about to turn 30, making her a spinster for her day; she lives with her mute, shell-shocked veteran brother, Tim, and his pet magpie.

Because she’s already had “the grip” (influenza), she is considered immune and is one of a few staff members dealing with the flu-ridden expectant mothers in quarantine in her overcrowded hospital. Each patient serves as a type, and Donoghue whirls through all the possible complications of historical childbirth: stillbirth, obstructed labor, catheterization, forceps, blood loss, transfusion, maternal death, and so on.

It’s not for the squeamish, and despite my usual love of medical reads, I felt it was something of a box-ticking exercise, with too much telling about medical procedures and recent Irish history. Because of the limited time frame – just three days – the book is far too rushed. We simply don’t have enough time to get to know Julia through and through, despite her first-person narration; the final 20 pages, in particular, are so far-fetched and melodramatic it’s hard to believe in a romance you’d miss if you blinked. And the omission of speech marks just doesn’t work – it’s downright confusing with so many dialogue-driven scenes.

Donoghue must have been writing this well before Covid-19, but I wouldn’t be surprised if the publication was hurried forward to take advantage of the story’s newfound relevance. It shows: what I read in May and June felt like an unpolished draft, with threads prematurely tied up to meet a deadline. This was an extremely promising project that, for me, was let down by the execution, but it’s still a gripping read that I wouldn’t steer you away from if you find the synopsis appealing. (Some more spoiler-y thoughts here.)

Prescient words about pandemics:

“All over the globe … some flu patients are dropping like flies while others recover, and we can’t solve the puzzle, nor do a blasted thing about it. … There’s no rhyme or reason to who’s struck down.”

“Doctor Lynn went on, As for the authorities, I believe the epidemic will have run its course before they’ve agreed to any but the most feeble action. Recommending onions and eucalyptus oil! Like sending beetles to stop a steamroller.”

Why the title?

Flu comes from the phrase “influenza delle stelle” – medieval Italians thought that illness was fated by the stars. There’s also one baby born a “stargazer” (facing up) and some literal looking up at the stars in the book.

My rating:

My thanks to Picador for the proof copy for review.

Other People’s Pets by R.L. Maizes

This is Maizes’ debut novel, after her 2019 short story collection We Love Anderson Cooper. Louise “La La” Fine and her father, Zev, share an unusual profession: While outwardly they are a veterinary student and a locksmith, respectively, for many years they broke into homes and sold the stolen goods. Despite close shaves, they’ve always gotten away with it – until now. When Zev is arrested, La La decides to return to her criminal ways just long enough to raise the money to post bail for him. But she doesn’t reckon on a few complications, like her father getting fed up with house arrest, her fiancé finding out about her side hustle, and her animal empathy becoming so strong that when she goes into a house she not only pilfers valuables but also cares for the needs of ailing pets inside.

This is Maizes’ debut novel, after her 2019 short story collection We Love Anderson Cooper. Louise “La La” Fine and her father, Zev, share an unusual profession: While outwardly they are a veterinary student and a locksmith, respectively, for many years they broke into homes and sold the stolen goods. Despite close shaves, they’ve always gotten away with it – until now. When Zev is arrested, La La decides to return to her criminal ways just long enough to raise the money to post bail for him. But she doesn’t reckon on a few complications, like her father getting fed up with house arrest, her fiancé finding out about her side hustle, and her animal empathy becoming so strong that when she goes into a house she not only pilfers valuables but also cares for the needs of ailing pets inside.

Flashbacks to La La’s growing-up years, especially her hurt over her mother leaving, take this deeper than your average humorous crime caper. The way the plot branches means that for quite a while Zev and La La are separated, and I grew a bit weary of extended time in Zev’s company, but this was a great summer read – especially for animal lovers – that never lost my attention. The magic realism of the human‒pet connection is believable and mild enough not to turn off readers who avoid fantasy. Think The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley meets Hollow Kingdom.

My rating:

My thanks to the author and Celadon Books for the free e-copy for review.

The Long Beds by Kate Miller

Here and there; now and then: the poems in Miller’s second collection enlarge such dichotomies by showcasing the interplay of the familiar and the foreign. A scientist struggles to transcribe birdsong, and a poppy opens in slow motion. “Flag” evokes the electric blue air and water of a Greek island, while “The Quarters” is set in the middle of the night in a French village. A few commissions, including “Waterloo Sunrise,” stick close to home in London or other southern England locales.

Here and there; now and then: the poems in Miller’s second collection enlarge such dichotomies by showcasing the interplay of the familiar and the foreign. A scientist struggles to transcribe birdsong, and a poppy opens in slow motion. “Flag” evokes the electric blue air and water of a Greek island, while “The Quarters” is set in the middle of the night in a French village. A few commissions, including “Waterloo Sunrise,” stick close to home in London or other southern England locales.

Various poems, including the multi-part “Album Without Photographs,” are about ancestor Muriel Miller’s experiences in India and Britain in the 1910s-20s. “Keepers of the States of Sleep and Wakefulness, fragment from A Masque,” patterned after “The Second Masque” by Ben Jonson, is an up-to-the-minute one written in April that names eight nurses from the night staff at King’s College Hospital (and the short YouTube film based on it is dedicated to all NHS nurses).

My two favorites were “Outside the Mind Shop,” in which urban foxes tear into bags of donations outside a charity shop one night while the speaker lies awake, and “Knapsack of Parting Gifts” a lovely elegy to a lost loved one. I spotted a lot of alliteration and assonance in the former, especially. Thematically, the collection is a bit scattered, but there are a lot of individual high points.

My rating:

My thanks to Carcanet Press for the free e-copy for review.

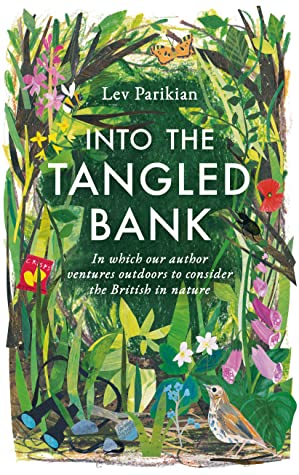

Into the Tangled Bank: In Which Our Author Ventures Outdoors to Consider the British in Nature by Lev Parikian

In the same way that kids sometimes write their address by going from the specific to the cosmic (street, city, country, continent, hemisphere, planet, galaxy), this book, a delightfully Bryson-esque tour, moves ever outwards, starting with the author’s own home and garden and proceeding to take in his South London patch and his journeys around the British Isles before closing with the wonders of the night sky. By slowing down to appreciate what is all around us, he proposes, we might enthuse others to engage with nature.

In the same way that kids sometimes write their address by going from the specific to the cosmic (street, city, country, continent, hemisphere, planet, galaxy), this book, a delightfully Bryson-esque tour, moves ever outwards, starting with the author’s own home and garden and proceeding to take in his South London patch and his journeys around the British Isles before closing with the wonders of the night sky. By slowing down to appreciate what is all around us, he proposes, we might enthuse others to engage with nature.

With the zeal of a recent convert, he guides readers through momentous sightings and everyday moments of connection. As they were his gateway, many of these memories involve birds: looking for the year’s first swifts, trying to sketch a heron and realizing he’s never looked at one properly before, avoiding angry terns on the Farne Islands, ringing a storm petrel on Skokholm, and seeing white-tailed eagles on the Isle of Skye. He brings unique places to life, and pays tribute to British naturalists who paved the way for today’s nature-lovers by visiting the homes of Charles Darwin, Gilbert White, Peter Scott, and more.

I was on the blog tour for Parikian’s previous book, Why Do Birds Suddenly Disappear?, in 2018. While the books are alike in levity (pun intended!), being full of self-deprecation and witty asides along with the astute observations, I think I enjoyed this one that little bit more for its all-encompassing approach to the experience of nature. I fully expect to see it on next year’s Wainwright Prize longlist (speaking of the Wainwright Prize, in yesterday’s post I correctly predicted four on the UK nature shortlist and two on the global conservation list!).

Readalikes (that happen to be from the same publisher): Under the Stars by Matt Gaw and The Seafarers by Stephen Rutt

My rating:

My thanks to Elliott & Thompson for the free copy for review.

Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir by Natasha Trethewey

Trethewey grew up in 1960s Mississippi with a Black mother and a white Canadian father, at a time when interracial marriage remained illegal in parts of the South. After her parents’ divorce, she and her mother, Gwen, moved to Georgia to start a new life, but her stepfather Joel was physically and psychologically abusive. Gwen’s murder opens and closes the book. Trethewey only returned to that Atlanta apartment on Memorial Drive after 30 years had passed. The blend of the objective (official testimonies and transcripts) and the subjective (interpreting photographs, and rendering dream sequences in poetic language) makes this a striking memoir, as delicate as it is painful. I recommend it highly to readers of Elizabeth Alexander and Dani Shapiro. (Full review forthcoming at Shiny New Books.)

Trethewey grew up in 1960s Mississippi with a Black mother and a white Canadian father, at a time when interracial marriage remained illegal in parts of the South. After her parents’ divorce, she and her mother, Gwen, moved to Georgia to start a new life, but her stepfather Joel was physically and psychologically abusive. Gwen’s murder opens and closes the book. Trethewey only returned to that Atlanta apartment on Memorial Drive after 30 years had passed. The blend of the objective (official testimonies and transcripts) and the subjective (interpreting photographs, and rendering dream sequences in poetic language) makes this a striking memoir, as delicate as it is painful. I recommend it highly to readers of Elizabeth Alexander and Dani Shapiro. (Full review forthcoming at Shiny New Books.)

My rating:

My thanks to Bloomsbury for the proof copy for review.

I’m reading two more July releases, Mostly Dead Things by Kristen Arnett (Corsair, 2 July; for Shiny New Books review), about a family taxidermy business in Florida, and The Liar’s Dictionary by Eley Williams (William Heinemann, 2 July), about an unusual dictionary being compiled in the Victorian period and digitized in the present day.

I’m reading two more July releases, Mostly Dead Things by Kristen Arnett (Corsair, 2 July; for Shiny New Books review), about a family taxidermy business in Florida, and The Liar’s Dictionary by Eley Williams (William Heinemann, 2 July), about an unusual dictionary being compiled in the Victorian period and digitized in the present day.

What July releases can you recommend?

If All the World and Love Were Young by Stephen Sexton: The Dylan Thomas Prize Blog Tour

For my second spot on the official Dylan Thomas Prize blog tour, I’m featuring the debut poetry collection If All the World and Love Were Young (2019) by Stephen Sexton, which was awarded the Forward Prize for Best First Collection. Sexton lives in Belfast (so this is also an incidental contribution to Reading Ireland Month) and was the winner of the 2016 National Poetry Competition and a 2018 Eric Gregory Award.

For my second spot on the official Dylan Thomas Prize blog tour, I’m featuring the debut poetry collection If All the World and Love Were Young (2019) by Stephen Sexton, which was awarded the Forward Prize for Best First Collection. Sexton lives in Belfast (so this is also an incidental contribution to Reading Ireland Month) and was the winner of the 2016 National Poetry Competition and a 2018 Eric Gregory Award.

The book is a highly original hybrid of video game imagery and a narrative about the final illness of his mother, who died in 2012. As a child the poet was obsessed with Super Mario World. He overlays the game’s landscapes onto his life to create an almost hallucinogenic fairy tale. Into this virtual world, which blends idyll and threat, comes the news of his mother’s cancer:

One summer’s day I’m summoned home to hear of cells which split and glitch

so haphazardly someone is called to intervene with poisons

drawn from strange and peregrine trees flourishing in distant kingdoms.

Her doctors are likened to wizards attempting magic –

In blue scrubs the Merlins apply various elixirs potions

panaceas to her body

– until they give up and acknowledge the limitations of medicine:

So we wait in the private room turn the egg timer of ourselves.

Hippocrates in his white coat brings with him a shake of the head …

where we cannot do some good

at least we must refrain from harm.

Super Mario settings provide the headings: Yoshi’s Island, Donut Plains, Forest of Illusion, Chocolate Island and so on. There are also references to bridges, Venetian canals, mines and labyrinths, as if to give illness the gravity of a mythological hero’s journey. Meanwhile, the title repeats the first line of “The Nymph’s Reply to the Shepherd” by Sir Walter Raleigh, which, as a rebuttal to Christopher Marlowe’s “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love,” eschews romanticism in favor of realism about change and mortality. Sexton wanted to include both views. (He discusses his inspirations in detail in this Irish Times article.)

Apart from one rough pantoum (“Choco-Ghost House”), I didn’t notice any other forms being used. This is free verse; internally unpunctuated, it has a run-on feel. While I do think readers are likely to get more out of the poems if they have some familiarity with Super Mario World and/or are gamers themselves, this is a striking book that examines bereavement in a new way.

Note: Be sure to stick around past “The End” for the Credits, which summarize all the book’s bizarrely diverse elements, and a lovely final poem that’s rather like a benediction.

My thanks to Midas PR for the free copy for review.

The Swansea University International Dylan Thomas Prize recognizes the best published work in the English language written by an author aged 39 or under. All literary genres are eligible, so there are poetry collections nominated as well as novels and short stories.

To recap, the 12 books on this year’s longlist are:

- Surge, Jay Bernard

- Flèche, Mary Jean Chan (my review)

- Exquisite Cadavers, Meena Kandasamy

- Things We Say in the Dark by Kirsty Logan (my preview & an excerpt)

- Black Car Burning, Helen Mort

- Virtuoso, Yelena Moskovich

- Inland, Téa Obreht

- Stubborn Archivist, Yara Rodrigues Fowler (my review)

- If All the World and Love Were Young, Stephen Sexton

- The Far Field, Madhuri Vijay

- On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, Ocean Vuong

- Lot, Bryan Washington

The shortlist will be announced on Tuesday, April 7th.

Some Books about Marriage

My pre-Valentine’s Day reading involved a lot of books with “love”, “heart”, “romance”, etc. in the title (here’s the post that resulted). I ended up with a number of leftovers, plus some incidental reads from late in 2019, that focused on marriage – whether it’s happy or troubled, or not technically a marriage at all.

Marriage: A Duet by Anne Taylor Fleming (2003)

Two novellas in one volume. In “A Married Woman,” Caroline Betts’s husband, William, is in a coma after a stroke or heart attack. As she and her adult children visit him in the hospital and ponder the decision they will have to make, she remains haunted by the affair William had with one of their daughter’s friends 15 years ago. Although at the time it seemed to destroy their marriage, she stayed and they built a new relationship.

Two novellas in one volume. In “A Married Woman,” Caroline Betts’s husband, William, is in a coma after a stroke or heart attack. As she and her adult children visit him in the hospital and ponder the decision they will have to make, she remains haunted by the affair William had with one of their daughter’s friends 15 years ago. Although at the time it seemed to destroy their marriage, she stayed and they built a new relationship.

I fully expected the second novella, “A Married Man,” to give William’s perspective (like in Carol Shields’s Happenstance), but instead it’s a separate story with different characters, though still set in California c. 2000. Here the dynamic is flipped: it’s the wife who had an affair and the husband who has to try to come to terms with it. David and Marcia Sanderson start marriage therapy at New Beginnings and, with the help of Prozac and Viagra, David hopes to get past his bitterness and give in to his wife’s romantic overtures.

Fleming is a careful observer of how marriages change over time and in response to shocks, but overall I found the tone of these tales abrasive and the language slightly raunchy.

Not quite about a marriage, but a relationship so lovely that I can’t resist including it…

Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf (2015)

Understated, bittersweet, realistic. Perfect. I’d long meant to try Kent Haruf’s work and even had the first two Plainsong trilogy books on the shelf, but this novella, picked up secondhand at a bargain price from a charity warehouse, demanded to be read first. Fans of Elizabeth Strout’s work will find in Haruf’s Holt, Colorado an echo of her Crosby, Maine – fictional towns where ordinary folk live out their quiet triumphs and sorrows. From the first line, which opens in medias res, Haruf draws you in, making you feel as if you’ve known these characters forever: “And then there was the day when Addie Moore made a call on Louis Waters.” She has a proposal for her neighbor. She’s a widow; he’s a widower. They’re both lonely and prone to melancholy thoughts about how they could have done better by their families (“life hasn’t turned out right for either of us, not the way we expected,” Louis says). Would he like to come over to her house at nights to talk and sleep? Just two ageing creatures huddling together for comfort; no hanky-panky expected or desired.

Understated, bittersweet, realistic. Perfect. I’d long meant to try Kent Haruf’s work and even had the first two Plainsong trilogy books on the shelf, but this novella, picked up secondhand at a bargain price from a charity warehouse, demanded to be read first. Fans of Elizabeth Strout’s work will find in Haruf’s Holt, Colorado an echo of her Crosby, Maine – fictional towns where ordinary folk live out their quiet triumphs and sorrows. From the first line, which opens in medias res, Haruf draws you in, making you feel as if you’ve known these characters forever: “And then there was the day when Addie Moore made a call on Louis Waters.” She has a proposal for her neighbor. She’s a widow; he’s a widower. They’re both lonely and prone to melancholy thoughts about how they could have done better by their families (“life hasn’t turned out right for either of us, not the way we expected,” Louis says). Would he like to come over to her house at nights to talk and sleep? Just two ageing creatures huddling together for comfort; no hanky-panky expected or desired.

So that’s just what they do. Before long, though, they come up against the disapproval of locals and family, especially when Addie’s grandson comes to stay and they join Louis to make a makeshift trio. The matter-of-fact prose, delivered without speech marks, belies a deep undercurrent of emotion in this story about the everyday miracle of human connection. There’s even a neat little reference to Haruf’s Benediction at the start of Chapter 34 (again like Strout, who peppered Olive, Again with cameo appearances from characters introduced in her earlier books). I also loved that the characters live on Cedar Street – I grew up on a Cedar Street. This gets my highest recommendation.

State of the Union: A Marriage in Ten Parts by Nick Hornby (2019)

Hornby has been making quite a name for himself in film and television. State of the Union is also a TV series, and reads a lot like a script because it’s composed mostly of the dialogue between Tom and Louise, an estranged couple who each week meet up for a drink in the pub before their marriage counseling appointment. There’s very little descriptive writing, and much of the time Hornby doesn’t even need to add speech attributions because it’s clear who’s saying what in the back and forth.

Hornby has been making quite a name for himself in film and television. State of the Union is also a TV series, and reads a lot like a script because it’s composed mostly of the dialogue between Tom and Louise, an estranged couple who each week meet up for a drink in the pub before their marriage counseling appointment. There’s very little descriptive writing, and much of the time Hornby doesn’t even need to add speech attributions because it’s clear who’s saying what in the back and forth.

The crisis in this marriage was precipitated by Louise, a gerontologist, sleeping with someone else after her sex life with Tom, an underemployed music writer, dried up. They rehash their life together, what went wrong, and what might happen next in 10 snappy chapters that are funny but also cut close to the bone. What married person hasn’t wondered where the magic went as midlife approaches? (Tom: “I hate to be unromantic, but convenient placement is pretty much the definition of marital sex.”)

Two-Part Invention: The Story of a Marriage by Madeleine L’Engle (1988)

The fourth and final volume of the autobiographical Crosswicks Journal. This one focuses on L’Engle’s 40-year marriage to Hugh Franklin, an actor best known for his role as Dr. Charles Tyler in All My Children between 1970 and 1983. In the book’s present day, the summer of 1986, she’s worried about Hugh when his bladder cancer, which starts off seeming treatable, leads to every possible complication and deterioration. Her days are divided between home, work (speaking engagements; teaching workshops at a writers’ conference) and the hospital.

The fourth and final volume of the autobiographical Crosswicks Journal. This one focuses on L’Engle’s 40-year marriage to Hugh Franklin, an actor best known for his role as Dr. Charles Tyler in All My Children between 1970 and 1983. In the book’s present day, the summer of 1986, she’s worried about Hugh when his bladder cancer, which starts off seeming treatable, leads to every possible complication and deterioration. Her days are divided between home, work (speaking engagements; teaching workshops at a writers’ conference) and the hospital.

Drifting between past and present, she remembers how she and Hugh met in the 1940s NYC theatre world, their early years of marriage, becoming parents to Josephine and Bion and then, when close friends died suddenly, adopting their goddaughter, and taking on the adventure of renovating Crosswicks farmhouse in Connecticut and temporarily running the local general store. As usual, L’Engle writes beautifully about having faith in a time of uncertainty. (The title refers not just to marriage, but also to Bach pieces that she, a devoted amateur piano player, used for practice.)

A wonderful passage about marriage:

“Our love has been anything but perfect and anything but static. Inevitably there have been times when one of us has outrun the other and has had to wait patiently for the other to catch up. There have been times when we have misunderstood each other, demanded too much of each other, been insensitive to the other’s needs. I do not believe there is any marriage where this does not happen. The growth of love is not a straight line, but a series of hills and valleys. I suspect that in every good marriage there are times when love seems to be over. Sometimes these desert lines are simply the only way to the next oasis, which is far more lush and beautiful after the desert crossing than it could possibly have been without it.”

The Wife by Meg Wolitzer (2003)

My latest book club read. On a flight to Finland, where her supposed genius writer of a husband, Joe Castleman, will accept the prestigious Helsinki Prize, Joan finally decides to leave him. When she first met Joe in 1956, she was a student at Smith College and he was her (married) creative writing professor, even though he’d only had a couple of stories published in middling literary magazines. Joan was a promising author in her own right, but when Joe left his first wife for her and she dropped out of college, she willingly took up a supporting role instead, and has remained in it for decades.

My latest book club read. On a flight to Finland, where her supposed genius writer of a husband, Joe Castleman, will accept the prestigious Helsinki Prize, Joan finally decides to leave him. When she first met Joe in 1956, she was a student at Smith College and he was her (married) creative writing professor, even though he’d only had a couple of stories published in middling literary magazines. Joan was a promising author in her own right, but when Joe left his first wife for her and she dropped out of college, she willingly took up a supporting role instead, and has remained in it for decades.

Ever since his first novel, The Walnut, a thinly veiled account of leaving Carol for Joan, Joe has produced books “populated by unhappy, unfaithful American husbands and their complicated wives.” Add on the fact that he’s Jewish and you have a Saul Bellow or Philip Roth type, a serial womanizer who’s publicly uxorious.

Alternating between the trip to Helsinki and telling scenes from earlier in their marriage, this short novel is deceptively profound. The setup may feel familiar, but Joan’s narration is bitingly funny and the points about the greater value attributed to men’s work are still valid. There’s also a juicy twist I never saw coming, as Joan decides what role she wants to play in perpetuating Joe’s literary legacy. My second by Wolitzer; I’ll certainly read more.

Plus a DNF:

The Story of a Marriage by Andrew Sean Greer (2008)

In 1953 in San Francisco, Pearlie Cook learns two major secrets about her husband Holland after his old friend shows up at their door. Greer tries to present another fact about the married couple as a big surprise, but had planted so many clues, starting on page 9, that I’d already guessed it and wasn’t shocked at the end of Part I as I was supposed to be. Greer writes perfectly capably, but I wasn’t able to connect with this one and didn’t love Less as much as most people did. I don’t think I’ll be trying another of his books. (I read 93 pages out of 195.)

In 1953 in San Francisco, Pearlie Cook learns two major secrets about her husband Holland after his old friend shows up at their door. Greer tries to present another fact about the married couple as a big surprise, but had planted so many clues, starting on page 9, that I’d already guessed it and wasn’t shocked at the end of Part I as I was supposed to be. Greer writes perfectly capably, but I wasn’t able to connect with this one and didn’t love Less as much as most people did. I don’t think I’ll be trying another of his books. (I read 93 pages out of 195.)

A sweltering summer versus an encasing of ice; an ordinary day versus decades of futile waiting. Sackville explores these contradictions only to deflate them, collapsing time such that a polar explorer’s wife and her great-great-niece can inhabit the same literal and emotional space despite being separated by more than a century. When Edward Mackley went off on his expedition in the early 1900s, he left behind Emily, his devoted, hopeful new bride. She was to live out the rest of her days in the Mackley family home with her brother-in-law and his growing family; Edward never returned. Now Julia and her husband Simon reside in that same Victorian house, serving as custodians of memories and artifacts from her ancestors’ travels and naturalist observations. From one early morning until the next, we peer into this average marriage with its sadness and silences. On this day, Julia discovers a family secret, and late on reveals another of her own, that subtly change how we see her and Emily.

A sweltering summer versus an encasing of ice; an ordinary day versus decades of futile waiting. Sackville explores these contradictions only to deflate them, collapsing time such that a polar explorer’s wife and her great-great-niece can inhabit the same literal and emotional space despite being separated by more than a century. When Edward Mackley went off on his expedition in the early 1900s, he left behind Emily, his devoted, hopeful new bride. She was to live out the rest of her days in the Mackley family home with her brother-in-law and his growing family; Edward never returned. Now Julia and her husband Simon reside in that same Victorian house, serving as custodians of memories and artifacts from her ancestors’ travels and naturalist observations. From one early morning until the next, we peer into this average marriage with its sadness and silences. On this day, Julia discovers a family secret, and late on reveals another of her own, that subtly change how we see her and Emily. “The literature of nineteenth-century arctic exploration is full of coincidence and drama—last-minute rescues, a desperate rifle shot to secure food for starving men, secret letters written to painfully missed loved ones. There are moments of surreal stillness, as in Parry’s journal when he writes of the sound of the human voice in the land. And of tender ministration and quiet forbearance in the face of inevitable death.”

“The literature of nineteenth-century arctic exploration is full of coincidence and drama—last-minute rescues, a desperate rifle shot to secure food for starving men, secret letters written to painfully missed loved ones. There are moments of surreal stillness, as in Parry’s journal when he writes of the sound of the human voice in the land. And of tender ministration and quiet forbearance in the face of inevitable death.” In 2011 Rapp’s baby son Ronan was diagnosed with Tay-Sachs disease, a degenerative nerve condition that causes blindness, deafness, seizures, paralysis and, ultimately, death. Tay-Sachs is usually seen in Ashkenazi Jews, so it came as a surprise: Rapp and her husband Rick both had to be carriers, whereas only he was Jewish; they never thought to get tested.

In 2011 Rapp’s baby son Ronan was diagnosed with Tay-Sachs disease, a degenerative nerve condition that causes blindness, deafness, seizures, paralysis and, ultimately, death. Tay-Sachs is usually seen in Ashkenazi Jews, so it came as a surprise: Rapp and her husband Rick both had to be carriers, whereas only he was Jewish; they never thought to get tested. Things got worse before they got better. As is common for couples who lose a child, Rapp and her first husband separated, soon after she completed her book. In the six months leading up to Ronan’s death in February 2013, his condition deteriorated rapidly and he needed hospice caretakers. Rapp came close to suicide. But in those desperate months, she also threw herself into a new relationship with Kent, a 20-years-older man who was there for her as Ronan was dying and would become her second husband and the father of her daughter, Charlotte (“Charlie”). The acrimonious split from Rick and the astonishment of a new life with Kent – starting in the literal sanctuary of his converted New Mexico chapel, and then moving to California – were two sides of a coin. So were missing Ronan and loving Charlie.

Things got worse before they got better. As is common for couples who lose a child, Rapp and her first husband separated, soon after she completed her book. In the six months leading up to Ronan’s death in February 2013, his condition deteriorated rapidly and he needed hospice caretakers. Rapp came close to suicide. But in those desperate months, she also threw herself into a new relationship with Kent, a 20-years-older man who was there for her as Ronan was dying and would become her second husband and the father of her daughter, Charlotte (“Charlie”). The acrimonious split from Rick and the astonishment of a new life with Kent – starting in the literal sanctuary of his converted New Mexico chapel, and then moving to California – were two sides of a coin. So were missing Ronan and loving Charlie. Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: Through Ifemelu’s years of studying, working, and blogging her way around the Eastern seaboard of the United States, Adichie explores the ways in which the experience of an African abroad differs from that of African Americans. On a sentence level as well as at a macro plot level, this was utterly rewarding.

Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: Through Ifemelu’s years of studying, working, and blogging her way around the Eastern seaboard of the United States, Adichie explores the ways in which the experience of an African abroad differs from that of African Americans. On a sentence level as well as at a macro plot level, this was utterly rewarding. Year of Wonders by Geraldine Brooks: In 1665, with the Derbyshire village of Eyam in the grip of the Plague, the drastic decision is made to quarantine it. Frustration with the pastor’s ineffectuality attracts people to religious extremism. Anna’s intimate first-person narration and the historical recreation are faultless, and there are so many passages that feel apt.

Year of Wonders by Geraldine Brooks: In 1665, with the Derbyshire village of Eyam in the grip of the Plague, the drastic decision is made to quarantine it. Frustration with the pastor’s ineffectuality attracts people to religious extremism. Anna’s intimate first-person narration and the historical recreation are faultless, and there are so many passages that feel apt. Shotgun Lovesongs by Nickolas Butler: Four childhood friends from Little Wing, Wisconsin. Which bonds will last, and which will be strained to the breaking point? This is a book full of nostalgia and small-town atmosphere. All the characters wonder whether they’ve made the right decisions or gotten stuck. A lot of bittersweet moments, but also comic ones.

Shotgun Lovesongs by Nickolas Butler: Four childhood friends from Little Wing, Wisconsin. Which bonds will last, and which will be strained to the breaking point? This is a book full of nostalgia and small-town atmosphere. All the characters wonder whether they’ve made the right decisions or gotten stuck. A lot of bittersweet moments, but also comic ones. Kindred by Octavia E. Butler: A perfect time-travel novel for readers who quail at science fiction. Dana, an African American writer in Los Angeles, is dropped into early-nineteenth-century Maryland. This was such an absorbing read, with first-person narration that makes you feel you’re right there alongside Dana on her perilous travels.

Kindred by Octavia E. Butler: A perfect time-travel novel for readers who quail at science fiction. Dana, an African American writer in Los Angeles, is dropped into early-nineteenth-century Maryland. This was such an absorbing read, with first-person narration that makes you feel you’re right there alongside Dana on her perilous travels. Dominicana by Angie Cruz: Ana Canción is just 15 when she arrives in New York from the Dominican Republic on the first day of 1965 to start her new life as the wife of Juan Ruiz. An arranged marriage and arriving in a country not knowing a word of the language: this is a valuable immigration story that stands out for its plucky and confiding narrator.

Dominicana by Angie Cruz: Ana Canción is just 15 when she arrives in New York from the Dominican Republic on the first day of 1965 to start her new life as the wife of Juan Ruiz. An arranged marriage and arriving in a country not knowing a word of the language: this is a valuable immigration story that stands out for its plucky and confiding narrator. Ella Minnow Pea by Mark Dunn: A book of letters in multiple sense. Laugh-out-loud silliness plus a sly message about science and reason over superstition = a rare combination that made this an enduring favorite. On my reread I was more struck by the political satire: freedom of speech is endangered in a repressive society slavishly devoted to a sacred text.

Ella Minnow Pea by Mark Dunn: A book of letters in multiple sense. Laugh-out-loud silliness plus a sly message about science and reason over superstition = a rare combination that made this an enduring favorite. On my reread I was more struck by the political satire: freedom of speech is endangered in a repressive society slavishly devoted to a sacred text. Love Medicine by Louise Erdrich: Interlocking stories that span half a century in the lives of a couple of Chippewa families that sprawl out from a North Dakota reservation. Looking for love, looking for work. Getting lucky, getting even. Their problems are the stuff of human nature and contemporary life. I adored the descriptions of characters and of nature.

Love Medicine by Louise Erdrich: Interlocking stories that span half a century in the lives of a couple of Chippewa families that sprawl out from a North Dakota reservation. Looking for love, looking for work. Getting lucky, getting even. Their problems are the stuff of human nature and contemporary life. I adored the descriptions of characters and of nature. Notes from an Exhibition by Patrick Gale: Nonlinear chapters give snapshots of the life of a bipolar artist and her interactions with her husband and children. Their Quakerism sets up a calm and compassionate atmosphere, but also allows family secrets to proliferate. The novel questions patterns of inheritance and the possibility of happiness.

Notes from an Exhibition by Patrick Gale: Nonlinear chapters give snapshots of the life of a bipolar artist and her interactions with her husband and children. Their Quakerism sets up a calm and compassionate atmosphere, but also allows family secrets to proliferate. The novel questions patterns of inheritance and the possibility of happiness. Confession with Blue Horses by Sophie Hardach: When Ella’s parents, East German art historians who came under Stasi surveillance, were caught trying to defect, their children were taken away from them. Decades later, Ella is determined to find her missing brother and learn what really happened to her mother. Eye-opening and emotionally involving.

Confession with Blue Horses by Sophie Hardach: When Ella’s parents, East German art historians who came under Stasi surveillance, were caught trying to defect, their children were taken away from them. Decades later, Ella is determined to find her missing brother and learn what really happened to her mother. Eye-opening and emotionally involving. The Go-Between by L.P. Hartley: Twelve-year-old Leo Colston is invited to spend July at his school friend’s home, Brandham Hall. You know from the famous first line on that this juxtaposes past and present. It’s masterfully done: the class divide, the picture of childhood tipping over into the teenage years, the oppressive atmosphere, the comical touches.

The Go-Between by L.P. Hartley: Twelve-year-old Leo Colston is invited to spend July at his school friend’s home, Brandham Hall. You know from the famous first line on that this juxtaposes past and present. It’s masterfully done: the class divide, the picture of childhood tipping over into the teenage years, the oppressive atmosphere, the comical touches. Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf: Addie is a widow; Louis is a widower. They’re both lonely and prone to fretting about what they could have done better. Would he like to come over to her house at night to talk and sleep? Matter-of-fact prose, delivered without speech marks, belies a deep undercurrent of emotion. Understated, bittersweet, realistic. Perfect.

Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf: Addie is a widow; Louis is a widower. They’re both lonely and prone to fretting about what they could have done better. Would he like to come over to her house at night to talk and sleep? Matter-of-fact prose, delivered without speech marks, belies a deep undercurrent of emotion. Understated, bittersweet, realistic. Perfect. The Emperor’s Children by Claire Messud: A 9/11 novel. The trio of protagonists, all would-be journalists aged 30, have never really had to grow up; now it’s time to get out from under the shadow of a previous generation and reassess what is admirable and who is expendable. This was thoroughly engrossing. Great American Novel territory, for sure.

The Emperor’s Children by Claire Messud: A 9/11 novel. The trio of protagonists, all would-be journalists aged 30, have never really had to grow up; now it’s time to get out from under the shadow of a previous generation and reassess what is admirable and who is expendable. This was thoroughly engrossing. Great American Novel territory, for sure. My Year of Meats by Ruth Ozeki: A Japanese-American filmmaker is tasked with finding all-American families and capturing their daily lives – and best meat recipes. There is a clear message here about cheapness and commodification, but Ozeki filters it through the wrenching stories of two women with fertility problems. Bold if at times discomforting.

My Year of Meats by Ruth Ozeki: A Japanese-American filmmaker is tasked with finding all-American families and capturing their daily lives – and best meat recipes. There is a clear message here about cheapness and commodification, but Ozeki filters it through the wrenching stories of two women with fertility problems. Bold if at times discomforting. Small Ceremonies by Carol Shields: An impeccable novella, it brings its many elements to a satisfying conclusion and previews the author’s enduring themes. Something of a sly academic comedy à la David Lodge, it’s laced with Shields’s quiet wisdom on marriage, parenting, the writer’s vocation, and the difficulty of ever fully understanding another life.

Small Ceremonies by Carol Shields: An impeccable novella, it brings its many elements to a satisfying conclusion and previews the author’s enduring themes. Something of a sly academic comedy à la David Lodge, it’s laced with Shields’s quiet wisdom on marriage, parenting, the writer’s vocation, and the difficulty of ever fully understanding another life. Larry’s Party by Carol Shields: The sweep of Larry’s life, from youth to middle age, is presented chronologically through chapters that are more like linked short stories: they focus on themes (family, friends, career, sex, clothing, health) and loop back to events to add more detail and new insight. I found so much to relate to in Larry’s story; Larry is really all of us.

Larry’s Party by Carol Shields: The sweep of Larry’s life, from youth to middle age, is presented chronologically through chapters that are more like linked short stories: they focus on themes (family, friends, career, sex, clothing, health) and loop back to events to add more detail and new insight. I found so much to relate to in Larry’s story; Larry is really all of us. Abide with Me by Elizabeth Strout: Tyler Caskey is a widowed pastor whose five-year-old daughter has gone mute and started acting up. As usual, Strout’s characters are painfully real, flawed people, often struggling with damaging obsessions. She tenderly probes the dark places of the community and its minister’s doubts, but finds the light shining through.

Abide with Me by Elizabeth Strout: Tyler Caskey is a widowed pastor whose five-year-old daughter has gone mute and started acting up. As usual, Strout’s characters are painfully real, flawed people, often struggling with damaging obsessions. She tenderly probes the dark places of the community and its minister’s doubts, but finds the light shining through. The Wife by Meg Wolitzer: On the way to Finland, where her genius writer husband will accept the prestigious Helsinki Prize, Joan finally decides to leave him. Alternating between the trip and earlier in their marriage, this is deceptively thoughtful with a juicy twist. Joan’s narration is witty and the point about the greater value attributed to men’s work is still valid.

The Wife by Meg Wolitzer: On the way to Finland, where her genius writer husband will accept the prestigious Helsinki Prize, Joan finally decides to leave him. Alternating between the trip and earlier in their marriage, this is deceptively thoughtful with a juicy twist. Joan’s narration is witty and the point about the greater value attributed to men’s work is still valid. Winter Journal by Paul Auster: Approaching age 64, the winter of his life, Auster decided to assemble his most visceral memories: scars, accidents and near-misses, what his hands felt and his eyes observed. The use of the second person draws readers in. I particularly enjoyed the tour through the 21 places he’s lived. One of the most remarkable memoirs I’ve ever read.

Winter Journal by Paul Auster: Approaching age 64, the winter of his life, Auster decided to assemble his most visceral memories: scars, accidents and near-misses, what his hands felt and his eyes observed. The use of the second person draws readers in. I particularly enjoyed the tour through the 21 places he’s lived. One of the most remarkable memoirs I’ve ever read. Heat by Bill Buford: Buford was an unpaid intern at Mario Batali’s famous New York City restaurant, Babbo. In between behind-the-scenes looks at frantic sessions of food prep, Buford traces Batali’s culinary pedigree through Italy and London. Exactly what I want from food writing: interesting trivia, quick pace, humor, and mouthwatering descriptions.

Heat by Bill Buford: Buford was an unpaid intern at Mario Batali’s famous New York City restaurant, Babbo. In between behind-the-scenes looks at frantic sessions of food prep, Buford traces Batali’s culinary pedigree through Italy and London. Exactly what I want from food writing: interesting trivia, quick pace, humor, and mouthwatering descriptions. Sixpence House: Lost in a Town of Books by Paul Collins: Collins moved to Hay-on-Wye with his wife and toddler son, hoping to make a life there. As he edited the manuscript of his first book, he started working for Richard Booth, the eccentric bookseller who crowned himself King of Hay. Warm, funny, and nostalgic. An enduring favorite of mine.

Sixpence House: Lost in a Town of Books by Paul Collins: Collins moved to Hay-on-Wye with his wife and toddler son, hoping to make a life there. As he edited the manuscript of his first book, he started working for Richard Booth, the eccentric bookseller who crowned himself King of Hay. Warm, funny, and nostalgic. An enduring favorite of mine. A Year on the Wing by Tim Dee: From a life spent watching birds, Dee weaves a mesh of memories and recent experiences, meditations and allusions. He moves from one June to the next and from Shetland to Zambia. The most powerful chapter is about watching peregrines at Bristol’s famous bridge – where he also, as a teen, saw a man commit suicide.

A Year on the Wing by Tim Dee: From a life spent watching birds, Dee weaves a mesh of memories and recent experiences, meditations and allusions. He moves from one June to the next and from Shetland to Zambia. The most powerful chapter is about watching peregrines at Bristol’s famous bridge – where he also, as a teen, saw a man commit suicide. The Frayed Atlantic Edge by David Gange: While kayaking down the western coast of the British Isles and Ireland, Gange delves into the folklore, geology, history, local language and wildlife of each region and island group – from the extreme north of Scotland at Muckle Flugga to the southwest tip of Cornwall. An intricate interdisciplinary approach.

The Frayed Atlantic Edge by David Gange: While kayaking down the western coast of the British Isles and Ireland, Gange delves into the folklore, geology, history, local language and wildlife of each region and island group – from the extreme north of Scotland at Muckle Flugga to the southwest tip of Cornwall. An intricate interdisciplinary approach. Traveling Mercies: Some Thoughts on Faith by Anne Lamott: There is a lot of bereavement and other dark stuff here, yet an overall lightness of spirit prevails. A college dropout and addict, Lamott didn’t walk into a church and get clean until her early thirties. Each essay is perfectly constructed, countering everyday angst with a fumbling faith.

Traveling Mercies: Some Thoughts on Faith by Anne Lamott: There is a lot of bereavement and other dark stuff here, yet an overall lightness of spirit prevails. A college dropout and addict, Lamott didn’t walk into a church and get clean until her early thirties. Each essay is perfectly constructed, countering everyday angst with a fumbling faith. In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado: This has my deepest admiration for how it prioritizes voice, theme and scene, gleefully does away with chronology and (not directly relevant) backstory, and engages with history, critical theory and the tropes of folk tales to interrogate her experience of same-sex domestic violence. (Second-person narration again!)

In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado: This has my deepest admiration for how it prioritizes voice, theme and scene, gleefully does away with chronology and (not directly relevant) backstory, and engages with history, critical theory and the tropes of folk tales to interrogate her experience of same-sex domestic violence. (Second-person narration again!) Period Piece by Gwen Raverat: Raverat was a granddaughter of Charles Darwin. This is a portrait of what it was like to grow up in a particular time and place (Cambridge from the 1880s to about 1909). Not just an invaluable record of domestic history, it is a funny and impressively thorough memoir that serves as a model for how to capture childhood.

Period Piece by Gwen Raverat: Raverat was a granddaughter of Charles Darwin. This is a portrait of what it was like to grow up in a particular time and place (Cambridge from the 1880s to about 1909). Not just an invaluable record of domestic history, it is a funny and impressively thorough memoir that serves as a model for how to capture childhood. The Universal Christ by Richard Rohr: I’d read two of the Franciscan priest’s previous books but was really blown away by the wisdom in this one. The argument in a nutshell is that Western individualism has perverted the good news of Jesus, which is renewal for everything and everyone. A real gamechanger. My copy is littered with Post-it flags.

The Universal Christ by Richard Rohr: I’d read two of the Franciscan priest’s previous books but was really blown away by the wisdom in this one. The argument in a nutshell is that Western individualism has perverted the good news of Jesus, which is renewal for everything and everyone. A real gamechanger. My copy is littered with Post-it flags. First Time Ever: A Memoir by Peggy Seeger: The octogenarian folk singer and activist has packed in enough adventure and experience for multiple lifetimes, and in some respects has literally lived two: one in America and one in England; one with Ewan MacColl and one with a female partner. Her writing is punchy and impressionistic. She’s my new hero.

First Time Ever: A Memoir by Peggy Seeger: The octogenarian folk singer and activist has packed in enough adventure and experience for multiple lifetimes, and in some respects has literally lived two: one in America and one in England; one with Ewan MacColl and one with a female partner. Her writing is punchy and impressionistic. She’s my new hero. A Three Dog Life by Abigail Thomas: A memoir in essays about her husband’s TBI and what kept her going. Unassuming and heart on sleeve, Thomas wrote one of the most beautiful books out there about loss and memory. It is one of the first memoirs I remember reading; it made a big impression the first time, but I loved it even more on a reread.

A Three Dog Life by Abigail Thomas: A memoir in essays about her husband’s TBI and what kept her going. Unassuming and heart on sleeve, Thomas wrote one of the most beautiful books out there about loss and memory. It is one of the first memoirs I remember reading; it made a big impression the first time, but I loved it even more on a reread. On Silbury Hill by Adam Thorpe: Explores the fragmentary history of the manmade Neolithic mound and various attempts to excavate it, but ultimately concludes we will never understand how and why it was made. A flawless integration of personal and wider history, as well as a profound engagement with questions of human striving and hubris.