Recent BookBrowse & Shiny New Books Reviews, and Book Club Ado

Excerpts from and links to some of my recent online writing for other places:

BookBrowse

Three O’Clock in the Morning by Gianrico Carofiglio

The quotation that gives Carofiglio’s tender novel its title is from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Crack-Up: “In a real dark night of the soul it is always three o’clock in the morning.” It lends an appropriate sense of time suspended, of earnest seeking and extreme circumstances: The main action of the book takes place over just a few days in June of 1983, when Italian teenager Antonio and his father are stranded in Marseilles while there for Antonio to be seen by an epilepsy specialist. The gift of this time outside of time allows them to get to know each other better, such that the memory of the trip will be precious to Antonio even decades later. I appreciated how the limited setting heightened this short novel’s emotions. Carofiglio invites readers to peer between the leisurely progression of events to see the bond that is being formed. (See my full review at BookBrowse. See also my related article on HarperVia, a new publishing imprint for international literature.)

The quotation that gives Carofiglio’s tender novel its title is from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Crack-Up: “In a real dark night of the soul it is always three o’clock in the morning.” It lends an appropriate sense of time suspended, of earnest seeking and extreme circumstances: The main action of the book takes place over just a few days in June of 1983, when Italian teenager Antonio and his father are stranded in Marseilles while there for Antonio to be seen by an epilepsy specialist. The gift of this time outside of time allows them to get to know each other better, such that the memory of the trip will be precious to Antonio even decades later. I appreciated how the limited setting heightened this short novel’s emotions. Carofiglio invites readers to peer between the leisurely progression of events to see the bond that is being formed. (See my full review at BookBrowse. See also my related article on HarperVia, a new publishing imprint for international literature.)

The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams

Inspired by the composition of the Oxford English Dictionary, this Australian debut novel explores the lives of the women on its fringes through the words that were omitted. The suffrage movement and World War I loom large as the storyline enters the 1910s. I most appreciated the relationships Esme has with the various women in her life. The main action spans the 40 years of the original composition of the OED. That scope means there is a lot of skipping forward in time. Especially in the first half, I longed for the narrative to slow down so I could spend more time with this character. Despite the first-person narration, I never felt I knew Esme very well. Women’s bonds and women’s words are strong themes in this forthrightly feminist novel that, despite its flaws, would make a great book club selection. (See my full review at BookBrowse. See also my reading list of books about dictionaries and lost words.)

Inspired by the composition of the Oxford English Dictionary, this Australian debut novel explores the lives of the women on its fringes through the words that were omitted. The suffrage movement and World War I loom large as the storyline enters the 1910s. I most appreciated the relationships Esme has with the various women in her life. The main action spans the 40 years of the original composition of the OED. That scope means there is a lot of skipping forward in time. Especially in the first half, I longed for the narrative to slow down so I could spend more time with this character. Despite the first-person narration, I never felt I knew Esme very well. Women’s bonds and women’s words are strong themes in this forthrightly feminist novel that, despite its flaws, would make a great book club selection. (See my full review at BookBrowse. See also my reading list of books about dictionaries and lost words.)

Shiny New Books

Notes from Deep Time: The Hidden Stories of the Earth Beneath Our Feet by Helen Gordon

To assess the place of humanity, we can look back to prehistory, but also forward to envision the “deep future.” (It was only in a late chapter on nuclear waste disposal sites and warning messages to the future that I found too much direct overlap with Footprints by David Farrier.) This engagingly blends both tactics, surveying the fields of geology and palaeontology and pondering the future traces of the Anthropocene. I most enjoyed the middle chapters, in which science meets wildlife and cultural studies. For instance, a chapter on ammonites leads into a profile of Mary Anning and the history of both fossil hunting and women in STEM careers. The prose is well pitched to the layman’s level. Interviews, travels, and snapshots from her own life generally keep the material from becoming too dry. An invigorating interdisciplinary tour. (See my full review at Shiny New Books.)

To assess the place of humanity, we can look back to prehistory, but also forward to envision the “deep future.” (It was only in a late chapter on nuclear waste disposal sites and warning messages to the future that I found too much direct overlap with Footprints by David Farrier.) This engagingly blends both tactics, surveying the fields of geology and palaeontology and pondering the future traces of the Anthropocene. I most enjoyed the middle chapters, in which science meets wildlife and cultural studies. For instance, a chapter on ammonites leads into a profile of Mary Anning and the history of both fossil hunting and women in STEM careers. The prose is well pitched to the layman’s level. Interviews, travels, and snapshots from her own life generally keep the material from becoming too dry. An invigorating interdisciplinary tour. (See my full review at Shiny New Books.)

My book club has been meeting via Zoom since April 2020. This is a common state of affairs for book clubs around the world. Especially since we have 12 members (if everyone attends, which is rare), we haven’t been able to contemplate meeting in person as of yet. However, a subset of us meet midway between the monthly reads to discuss women’s classics like Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time. For next week’s meeting on Mrs. Dalloway, we are going to attempt a six-person get-together in one member’s house.

Anyway, a neat thing we did last month was a Zoom chat with the author: a BBC correspondent who happens to be the brother of one of our members. If you’re a news junkie in the UK, you may know the name Jon Sopel, though since I don’t have a telly or ever listen to radio, I hadn’t encountered him until this “in-person” meet-up. He has been the BBC’s North America Editor since 2014.

Anyway, a neat thing we did last month was a Zoom chat with the author: a BBC correspondent who happens to be the brother of one of our members. If you’re a news junkie in the UK, you may know the name Jon Sopel, though since I don’t have a telly or ever listen to radio, I hadn’t encountered him until this “in-person” meet-up. He has been the BBC’s North America Editor since 2014.

UnPresidented is the third book he wrote over the course of the Trump presidency. It started off as a diary of the 2020 election campaign, beginning in July 2019, but of course soon morphed into something slightly different: a chronicle of life in D.C. and London during Covid-19 and a record of the Trump mishandling of the pandemic. But as well as a farcical election process and a public health crisis, 2020’s perfect storm also included economic collapse and social upheaval – thanks to the murder of George Floyd and the subsequent Black Lives Matter protests worldwide plus isolated rioting.

UnPresidented served as a good reminder for me of the timeline of events and the full catalogue of outrages committed by Trump and his cronies. You just have to shake your head over the litany of ridiculous things he said and did, and got away with – any one of which might have sunk another president or candidate. The style is breezy and off-the-cuff, so the book reads quickly. There’s a good balance between world events and personal ones, with his family split across the UK and Australia. I appreciated the insight into differences from the British system. I thought it would be depressing reading back through the events of 2020, but for the most part the knowledge that everything turned out “right” allowed me to see the humour in it. Still, I found it excruciating reading about the four days following the election.

Sopel kindly gave us an hour of his time one Wednesday evening before he had to go on air and answered our questions about Biden, Harris, journalistic ethics, and more. He was charming and eloquent, as befits his profession.

Would any of these books interest you?

Recommended March Releases: Broder, Fuller, Lamott, Polzin

Three novels that range in tone from carnal allegorical excess to quiet, bittersweet reflection via low-key menace; and essays about keeping the faith in the most turbulent of times.

Milk Fed by Melissa Broder

Rachel’s body and mommy issues are major and intertwined: she takes calorie counting and exercise to an extreme, and her therapist has suggested that she take a 90-day break from contact with her overbearing mother. Her workdays at a Hollywood talent management agency are punctuated by carefully regimented meals, one of them a 16-ounce serving of fat-free frozen yogurt from a shop run by Orthodox Jews. One day it’s not the usual teenage boy behind the counter, but his overweight older sister, Miriam. Miriam makes Rachel elaborate sundaes instead of her usual abstemious cups and Rachel lets herself eat them even though it throws her whole diet off. She realizes she’s attracted to Miriam, who comes to fill the bisexual Rachel’s fantasies, and they strike up a tentative relationship over Chinese food and classic film dates as well as Shabbat dinners at Miriam’s family home.

If you’re familiar with The Pisces, Broder’s Women’s Prize-longlisted debut, you should recognize the pattern here: a deep exploration of wish fulfilment and psychological roles, wrapped up in a sarcastic and sexually explicit narrative. Fat becomes not something to fear but a source of comfort; desire for food and for the female body go hand in hand. Rachel says, “It felt like a miracle to be able to eat what I desired, not more or less than that. It was shocking, as though my body somehow knew what to do and what not to do—if only I let it.”

With the help of her therapist, a rabbi that appears in her dreams, and the recurring metaphor of the golem, Rachel starts to grasp the necessity of mothering herself and becoming the shaper of her own life. I was uneasy that Miriam, like Theo in The Pisces, might come to feel more instrumental than real, but overall this was an enjoyable novel that brings together its disparate subjects convincingly. (But is it hot or smutty? You tell me.)

With thanks to Bloomsbury for the proof copy for review.

Unsettled Ground by Claire Fuller

At a glance, the cover for Fuller’s fourth novel seems to host a riot of luscious flowers and fruit, but look closer and you’ll see the daisies are withering and the grapes rotting; there’s a worm exiting the apple and flies are overseeing the decomposition. Just as the image slowly reveals signs of decay, Fuller’s novel gradually unveils the drawbacks of its secluded village setting. Jeanie and Julius Seeder, 51-year-old twins, lived with their mother, Dot, until she was felled by a stroke. They’d always been content with a circumscribed, self-sufficient existence, but now their whole way of life is called into question. Their mother’s rent-free arrangement with the landowners, the Rawsons, falls through, and the cash they keep in a biscuit tin in the cottage comes nowhere close to covering her debts, let alone a funeral.

During the Zoom book launch event, Fuller confessed that she’s “incapable of writing a happy novel,” so consider that your warning of how bleak things will get for her protagonists – though by the end there are pinpricks of returning hope. Before then, though, readers navigate an unrelenting spiral of rural poverty and bad luck, exacerbated by illiteracy and the greed and unkindness of others. One of Fuller’s strengths is creating atmosphere, and there are many images and details here that build the picture of isolation and pathos, such as a piano marooned halfway to a derelict caravan along a forest track and Jeanie having to count pennies so carefully that she must choose between toilet paper and dish soap at the shop.

Unsettled Ground is set in a fictional North Wessex Downs village not far from where I live. I loved spotting references to local places and to folk music – Jeanie and Julius might not have book smarts or successful careers, but they inherited Dot’s love of music and when they pick up a fiddle and guitar they tune in to the ancient magic of storytelling. Much of the novel is from Jeanie’s perspective and she makes for an out-of-the-ordinary yet relatable POV character. I found the novel heavy on exposition, which somewhat slowed my progress through it, but it’s comparable to Fuller’s other work in that it focuses on family secrets, unusual states of mind, and threatening situations. She’s rapidly become one of my favourite contemporary novelists, and I’d recommend this to you if you’ve liked her other work or Fiona Mozley’s Elmet.

With thanks to Penguin Fig Tree for the proof copy for review.

Dusk, Night, Dawn: On Revival and Courage by Anne Lamott

These are Lamott’s best new essays (if you don’t count Small Victories, which reprinted some of her greatest hits) in nearly a decade. The book is a fitting follow-up to 2018’s Almost Everything in that it tackles the same central theme: how to have hope in God and in other people even when the news – Trump, Covid, and climate breakdown – only heralds the worst.

One key thing that has changed in Lamott’s life since her last book is getting married for the first time, in her mid-sixties, to a Buddhist. “How’s married life?” people can’t seem to resist asking her. In thinking of marriage she writes about love and friendship, constancy and forgiveness, none of which comes easy. Her neurotic nature flares up every now and again, but Neal helps to talk her down. Fragments of her early family life come back as she considers all her parents were up against and concludes that they did their best (“How paltry and blocked our family love was, how narrow the bandwidth of my parents’ spiritual lives”).

Opportunities for maintaining quiet faith in spite of the circumstances arise all the time for her, whether it’s a variety show that feels like it will never end, a four-day power cut in California, the kitten inexplicably going missing, or young people taking to the streets to protest about the climate crisis they’re inheriting. A short postscript entitled “Covid College” gives thanks for “the blessings of COVID: we became more reflective, more contemplative.”

The prose and anecdotes feel fresher here than in several of the author’s other recent books. I highlighted quote after quote on my Kindle. Some of these essays will be well worth rereading and deserve to become classics in the Lamott canon, especially “Soul Lather,” “Snail Hymn,” “Light Breezes,” and “One Winged Love.”

I read an advanced digital review copy via NetGalley. Available from Riverhead in the USA and SPCK in the UK.

Brood by Jackie Polzin

Polzin’s debut novel is a quietly touching story of a woman in the Midwest raising chickens and coming to terms with the shape of her life. The unnamed narrator is Everywoman and no one at the same time. As in recent autofiction by Rachel Cusk and Sigrid Nunez, readers find observations of other people (and animals), a record of their behaviour and words; facts about the narrator herself are few and far between, though it is possible to gradually piece together a backstory for her. At one point she reveals, with no fanfare, that she miscarried four months into pregnancy in the bathroom of one of the houses she cleans. There is a bittersweet tone to this short work. It’s a low-key, genuine portrait of life in the in-between stages and how it can be affected by fate or by other people’s decisions.

See my full review at BookBrowse. I was also lucky enough to do an interview with the author.

I read an advanced digital review copy via Edelweiss. Available from Doubleday in the USA. To be released in the UK by Picador tomorrow, April 1st.

What recent releases can you recommend?

Two Recent Reviews for BookBrowse

The Bell in the Lake by Lars Mytting

A legend from Mytting’s hometown tells of two centuries-old church bells that, like conjoined twins, were never meant to be separated. Inspired by that story and by the real-life move of a stave church from Norway to what is now Poland, he embarked on a trilogy in which history and myth mingle to determine the future of the isolated village of Butangen. The novel is constructed around compelling dichotomies. Astrid Hekne, a feminist ahead of her time, is in contrast with the local pastor’s conventional views on gender roles. She also represents the village’s unlearned folk; Deborah Dawkin successfully captures Mytting’s use of dialect in her translation, making Astrid sound like one of Thomas Hardy’s rustic characters.

A legend from Mytting’s hometown tells of two centuries-old church bells that, like conjoined twins, were never meant to be separated. Inspired by that story and by the real-life move of a stave church from Norway to what is now Poland, he embarked on a trilogy in which history and myth mingle to determine the future of the isolated village of Butangen. The novel is constructed around compelling dichotomies. Astrid Hekne, a feminist ahead of her time, is in contrast with the local pastor’s conventional views on gender roles. She also represents the village’s unlearned folk; Deborah Dawkin successfully captures Mytting’s use of dialect in her translation, making Astrid sound like one of Thomas Hardy’s rustic characters.

- See my full review at BookBrowse.

- See also my related article on stave churches.

- One of the coolest things I did during the first pandemic lockdown in the UK was attend an online book club meeting on The Bell in the Lake, run by MacLehose Press, Mytting’s UK publisher. It was so neat to see the author and translator speak “in person” via a Zoom meeting and to ask him a couple of questions in the chat window.

- A readalike (and one of my all-time favorite novels) is Carsten Jensen’s We, the Drowned.

Memorial by Bryan Washington

In Washington’s debut novel, set in Houston and Osaka, two young men reassess their commitments to their families and to each other. The narration is split between Benson and Mike, behind whose apparent lack of affect is a quiet seam of emotion. Both young men are still shaken by their parents’ separations, and haunted by patterns of abuse and addiction. Flashbacks to how they met create a tender backstory for a limping romance. Although the title (like most of the story titles in Lot) refers to a Houston neighborhood, it has broader significance, inviting readers to think about the place our loved ones have in our memories. Despite the tough issues the characters face, their story is warm-hearted rather than grim. Memorial is a candid, bittersweet work from a talented young writer whose career I will follow with interest.

In Washington’s debut novel, set in Houston and Osaka, two young men reassess their commitments to their families and to each other. The narration is split between Benson and Mike, behind whose apparent lack of affect is a quiet seam of emotion. Both young men are still shaken by their parents’ separations, and haunted by patterns of abuse and addiction. Flashbacks to how they met create a tender backstory for a limping romance. Although the title (like most of the story titles in Lot) refers to a Houston neighborhood, it has broader significance, inviting readers to think about the place our loved ones have in our memories. Despite the tough issues the characters face, their story is warm-hearted rather than grim. Memorial is a candid, bittersweet work from a talented young writer whose career I will follow with interest.

- See my full review at BookBrowse.

- See also my related article on the use of quotation marks (or not!) to designate speech.

I enjoyed this so much that I immediately ordered Lot with my birthday money. I’d particularly recommend it if you want an earthier version of Brandon Taylor’s Booker-shortlisted Real Life (which I’m halfway through and enjoying, though I can see the criticisms about its dry, slightly effete prose).

I enjoyed this so much that I immediately ordered Lot with my birthday money. I’d particularly recommend it if you want an earthier version of Brandon Taylor’s Booker-shortlisted Real Life (which I’m halfway through and enjoying, though I can see the criticisms about its dry, slightly effete prose).- This came out in the USA from Riverhead in late October, but UK readers have to wait until January 7th (Atlantic Books).

Recent Writing for BookBrowse, Shiny New Books and the TLS

A peek at the bylines I’ve had elsewhere so far this year.

BookBrowse

A Good Neighborhood by Therese Anne Fowler: In Fowler’s sixth novel, issues of race and privilege undermine a teen romance and lead to tragedy in a seemingly idyllic North Carolina neighborhood. A Good Neighborhood is an up-to-the-minute story packed with complex issues including celebrity culture, casual racism, sexual exploitation, and environmental degradation. It is narrated in a first-person plural voice, much like the Greek chorus of a classical tragedy. If you loved Tayari Jones’s An American Marriage, this needs to be next on your to-read list. It is a book that will make you think, and a book that will make you angry; I recommend it to socially engaged readers and book clubs alike.

A Good Neighborhood by Therese Anne Fowler: In Fowler’s sixth novel, issues of race and privilege undermine a teen romance and lead to tragedy in a seemingly idyllic North Carolina neighborhood. A Good Neighborhood is an up-to-the-minute story packed with complex issues including celebrity culture, casual racism, sexual exploitation, and environmental degradation. It is narrated in a first-person plural voice, much like the Greek chorus of a classical tragedy. If you loved Tayari Jones’s An American Marriage, this needs to be next on your to-read list. It is a book that will make you think, and a book that will make you angry; I recommend it to socially engaged readers and book clubs alike. ![]()

Pew by Catherine Lacey: Lacey’s third novel is a mysterious fable about a stranger showing up in a Southern town in the week before an annual ritual. Pew’s narrator, homeless, mute and amnesiac, wakes up one Sunday in the middle of a church service, observing everything like an alien anthropologist. The stranger’s gender, race, and age are entirely unclear, so the Reverend suggests the name “Pew”. The drama over deciphering Pew’s identity plays out against the preparations for the enigmatic Forgiveness Festival and increasing unrest over racially motivated disappearances. Troubling but strangely compelling; recommended to fans of Shirley Jackson and Flannery O’Connor. [U.S. publication pushed back to July 21st]

Pew by Catherine Lacey: Lacey’s third novel is a mysterious fable about a stranger showing up in a Southern town in the week before an annual ritual. Pew’s narrator, homeless, mute and amnesiac, wakes up one Sunday in the middle of a church service, observing everything like an alien anthropologist. The stranger’s gender, race, and age are entirely unclear, so the Reverend suggests the name “Pew”. The drama over deciphering Pew’s identity plays out against the preparations for the enigmatic Forgiveness Festival and increasing unrest over racially motivated disappearances. Troubling but strangely compelling; recommended to fans of Shirley Jackson and Flannery O’Connor. [U.S. publication pushed back to July 21st] ![]()

Shiny New Books

Losing Eden: Why Our Minds Need the Wild by Lucy Jones: While nature’s positive effect on human mental health is something we know intuitively and can explain anecdotally, Jones was determined to investigate the scientific mechanism behind it. She set out to make an empirical enquiry and discovered plenty of evidence in the scientific literature, but also attests to the personal benefits that nature has for her and explores the spiritual connection that many have found. Losing Eden is full of both common sense and passion, cramming masses of information into 200 pages yet never losing sight of the big picture. Just as Silent Spring led to real societal change, let’s hope Jones’s work inspires steps in the right direction.

Losing Eden: Why Our Minds Need the Wild by Lucy Jones: While nature’s positive effect on human mental health is something we know intuitively and can explain anecdotally, Jones was determined to investigate the scientific mechanism behind it. She set out to make an empirical enquiry and discovered plenty of evidence in the scientific literature, but also attests to the personal benefits that nature has for her and explores the spiritual connection that many have found. Losing Eden is full of both common sense and passion, cramming masses of information into 200 pages yet never losing sight of the big picture. Just as Silent Spring led to real societal change, let’s hope Jones’s work inspires steps in the right direction. ![]()

[+ Reviews of 4 more Wainwright Prize (for nature writing) longlistees on the way!]

The Bass Rock by Evie Wyld: While it ranges across the centuries, the novel always sticks close to the title location. Just as the louring rock is inescapable in the distance if you look out from the Edinburgh hills, there’s no avoiding violence for the women and children of the novel. It’s a sobering theme, certainly, but Wyld convinced me that hers is an accurate vision and a necessary mission. The novel cycles through its three strands in an ebb and flow pattern that seems appropriate to the coastal setting and creates a sense of time’s fluidity. The best 2020 novel I’ve read, memorable for its elegant, time-blending structure as well as its unrelenting course – and set against that perfect backdrop of an indifferent monolith.

The Bass Rock by Evie Wyld: While it ranges across the centuries, the novel always sticks close to the title location. Just as the louring rock is inescapable in the distance if you look out from the Edinburgh hills, there’s no avoiding violence for the women and children of the novel. It’s a sobering theme, certainly, but Wyld convinced me that hers is an accurate vision and a necessary mission. The novel cycles through its three strands in an ebb and flow pattern that seems appropriate to the coastal setting and creates a sense of time’s fluidity. The best 2020 novel I’ve read, memorable for its elegant, time-blending structure as well as its unrelenting course – and set against that perfect backdrop of an indifferent monolith. ![]()

Times Literary Supplement

I Am an Island by Tamsin Calidas: A record of a demoralizing journey into extreme loneliness on a Scottish island, this offers slivers of hope that mystical connection with the natural world can restore a sense of self. In places the narrative is a litany of tragedies and bad news. The story’s cathartic potential relies on its audience’s willingness to stick with a book that can be – to be blunt –depressing. The writing often tends towards the poetic, but is occasionally marred by platitudes and New Age sentiments. As with Educated, it’s impossible not to marvel at all the author has survived. Admiring Calidas’s toughness, though, doesn’t preclude relief at reaching the final page. (Full review in May 29th issue.)

I Am an Island by Tamsin Calidas: A record of a demoralizing journey into extreme loneliness on a Scottish island, this offers slivers of hope that mystical connection with the natural world can restore a sense of self. In places the narrative is a litany of tragedies and bad news. The story’s cathartic potential relies on its audience’s willingness to stick with a book that can be – to be blunt –depressing. The writing often tends towards the poetic, but is occasionally marred by platitudes and New Age sentiments. As with Educated, it’s impossible not to marvel at all the author has survived. Admiring Calidas’s toughness, though, doesn’t preclude relief at reaching the final page. (Full review in May 29th issue.) ![]()

We Swim to the Shark: Overcoming fear one fish at a time by Georgie Codd: Codd’s offbeat debut memoir chronicles her quest to conquer a phobia of sea creatures. Inspired by a friend’s experience of cognitive behavioral therapy to cure arachnophobia, she crafted a program of controlled exposure. She learned to scuba dive before a trip to New Zealand, returning via Thailand with an ultimate challenge in mind: her quarry was the whale shark, a creature even Jacques Cousteau only managed to sight twice. The book has a jolly, self-deprecating tone despite its exploration of danger and dread. A more directionless second half leads to diminished curiosity about whether that elusive whale shark will make an appearance. (Full review in a forthcoming issue.)

We Swim to the Shark: Overcoming fear one fish at a time by Georgie Codd: Codd’s offbeat debut memoir chronicles her quest to conquer a phobia of sea creatures. Inspired by a friend’s experience of cognitive behavioral therapy to cure arachnophobia, she crafted a program of controlled exposure. She learned to scuba dive before a trip to New Zealand, returning via Thailand with an ultimate challenge in mind: her quarry was the whale shark, a creature even Jacques Cousteau only managed to sight twice. The book has a jolly, self-deprecating tone despite its exploration of danger and dread. A more directionless second half leads to diminished curiosity about whether that elusive whale shark will make an appearance. (Full review in a forthcoming issue.) ![]()

Dottoressa: An American Doctor in Rome by Susan Levenstein: In the late 1970s, Levenstein moved from New York City to Rome with her Italian husband and set up a private medical practice catering to English-speaking expatriates. Her light-hearted yet trenchant memoir highlights the myriad contrasts between the United States and Italy revealed by their health care systems. Italy has a generous national health service, but it is perennially underfunded and plagued by corruption and inefficiency. The tone is conversational and even-handed. In the pandemic aftermath, though, Italian sloppiness and shortages no longer seem like harmless matters to shake one’s head over. (Full review coming up in June 19th issue.)

Dottoressa: An American Doctor in Rome by Susan Levenstein: In the late 1970s, Levenstein moved from New York City to Rome with her Italian husband and set up a private medical practice catering to English-speaking expatriates. Her light-hearted yet trenchant memoir highlights the myriad contrasts between the United States and Italy revealed by their health care systems. Italy has a generous national health service, but it is perennially underfunded and plagued by corruption and inefficiency. The tone is conversational and even-handed. In the pandemic aftermath, though, Italian sloppiness and shortages no longer seem like harmless matters to shake one’s head over. (Full review coming up in June 19th issue.) ![]()

Mario Batali is the book’s presiding imp. In 2002–3, Buford was an unpaid intern in the kitchen of Batali’s famous New York City restaurant, Babbo, which serves fancy versions of authentic Italian dishes. It took 18 months for him to get so much as a thank-you. Buford’s strategy was “be invisible, be useful, and eventually you’ll be given a chance to do more.”

Mario Batali is the book’s presiding imp. In 2002–3, Buford was an unpaid intern in the kitchen of Batali’s famous New York City restaurant, Babbo, which serves fancy versions of authentic Italian dishes. It took 18 months for him to get so much as a thank-you. Buford’s strategy was “be invisible, be useful, and eventually you’ll be given a chance to do more.” I was delighted to learn that this year Buford released a sequel of sorts, this one about French cuisine: Dirt. It’s on my wish list.

I was delighted to learn that this year Buford released a sequel of sorts, this one about French cuisine: Dirt. It’s on my wish list. Along with an agricultural center, the American Baptist missionaries were closely associated with a hospital, Hôpital le Bon Samaritain, run by amateur archaeologist Dr. Hodges and his family. Although Apricot and her two younger sisters were young enough to adapt easily to life in a developing country, they were disoriented each time the family returned to California in between assignments. Their bonds were shaky due to her father’s temper, her parents’ rocky relationship, and the jealousy provoked over almost adopting a Haitian baby girl.

Along with an agricultural center, the American Baptist missionaries were closely associated with a hospital, Hôpital le Bon Samaritain, run by amateur archaeologist Dr. Hodges and his family. Although Apricot and her two younger sisters were young enough to adapt easily to life in a developing country, they were disoriented each time the family returned to California in between assignments. Their bonds were shaky due to her father’s temper, her parents’ rocky relationship, and the jealousy provoked over almost adopting a Haitian baby girl. We Were the Mulvaneys by Joyce Carol Oates (oats!)

We Were the Mulvaneys by Joyce Carol Oates (oats!)

Of course, not all of my selections were explicitly food-related; others simply had food words in their titles (or, as above, in the author’s name). Of these, my favorite was a reread,

Of course, not all of my selections were explicitly food-related; others simply had food words in their titles (or, as above, in the author’s name). Of these, my favorite was a reread,

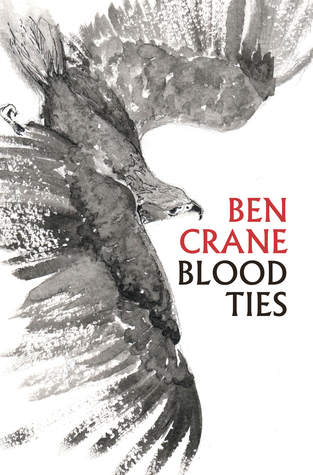

Blood Ties by Ben Crane: Artist Ben Crane has developed a passion for birds of prey, raising hawks and training as a falconer. “I saw that my feelings towards nature, and birds of prey in particular, ran in parallel with my feelings for my son,” he writes. Blood Ties accordingly cuts between the story of rehabilitating a pair of rescued sparrowhawks named Girl and Boy and a parallel story about raising his son as a part-time single father. Together these strands emphasize the common concerns that arise when caring for any creature. Crane’s descriptive language is memorably sharp. Whatever struggles his Asperger’s entails, it seems to heighten his observational skills. Pruning the travel segments would have produced a more focused memoir, but this is a powerful story all the same – of the ties that bind us, both to nature and our own families. (Full review in February 8th issue.)

Blood Ties by Ben Crane: Artist Ben Crane has developed a passion for birds of prey, raising hawks and training as a falconer. “I saw that my feelings towards nature, and birds of prey in particular, ran in parallel with my feelings for my son,” he writes. Blood Ties accordingly cuts between the story of rehabilitating a pair of rescued sparrowhawks named Girl and Boy and a parallel story about raising his son as a part-time single father. Together these strands emphasize the common concerns that arise when caring for any creature. Crane’s descriptive language is memorably sharp. Whatever struggles his Asperger’s entails, it seems to heighten his observational skills. Pruning the travel segments would have produced a more focused memoir, but this is a powerful story all the same – of the ties that bind us, both to nature and our own families. (Full review in February 8th issue.)  Notes for the Everlost: A Field Guide to Grief by Kate Inglis: Inglis, a Nova Scotian photographer and children’s author, has written this delicate, playful handbook – something between a bereavement memoir and a self-help guide – for people who feel they might disappear into grief for ever. In 2007, Inglis’s identical twin sons were born premature, at twenty-seven weeks. Ben lived but Liam died. Every milestone in Ben’s life would serve as a reminder of the brother who should have been growing up alongside him. The unfairness was particularly keen on the day she returned to hospital for two appointments: Ben’s check-up and a report on Liam’s autopsy. Unable to sustain the eye-popping freshness of the prose in the introduction, Inglis resorts to some clichés in what follows. But this kooky, candid book will be valuable to anyone facing bereavement or supporting a loved one through it. (Full review in March 15th issue.)

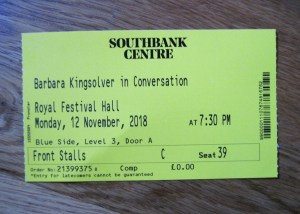

Notes for the Everlost: A Field Guide to Grief by Kate Inglis: Inglis, a Nova Scotian photographer and children’s author, has written this delicate, playful handbook – something between a bereavement memoir and a self-help guide – for people who feel they might disappear into grief for ever. In 2007, Inglis’s identical twin sons were born premature, at twenty-seven weeks. Ben lived but Liam died. Every milestone in Ben’s life would serve as a reminder of the brother who should have been growing up alongside him. The unfairness was particularly keen on the day she returned to hospital for two appointments: Ben’s check-up and a report on Liam’s autopsy. Unable to sustain the eye-popping freshness of the prose in the introduction, Inglis resorts to some clichés in what follows. But this kooky, candid book will be valuable to anyone facing bereavement or supporting a loved one through it. (Full review in March 15th issue.)  In person Kingsolver was a delight – warm and funny, with a generic American accent that doesn’t betray her Kentucky roots. In her beaded caftan and knee-high oxblood boots, she exuded girlish energy despite the shock of white in her hair. Although her fervor for the scientific method and a socially responsible government came through clearly, there was a lightness about her that tempered the weighty issues she covers in her novel.

In person Kingsolver was a delight – warm and funny, with a generic American accent that doesn’t betray her Kentucky roots. In her beaded caftan and knee-high oxblood boots, she exuded girlish energy despite the shock of white in her hair. Although her fervor for the scientific method and a socially responsible government came through clearly, there was a lightness about her that tempered the weighty issues she covers in her novel.