Three Days in June vs. Three Weeks in July

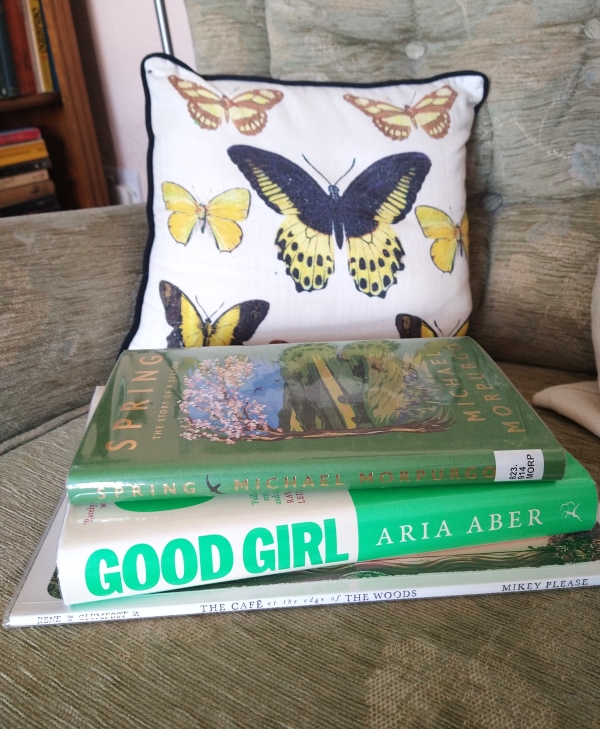

Two very good 2025 releases that I read from the library. While they could hardly be more different in tone and particulars, I couldn’t resist linking them via their titles.

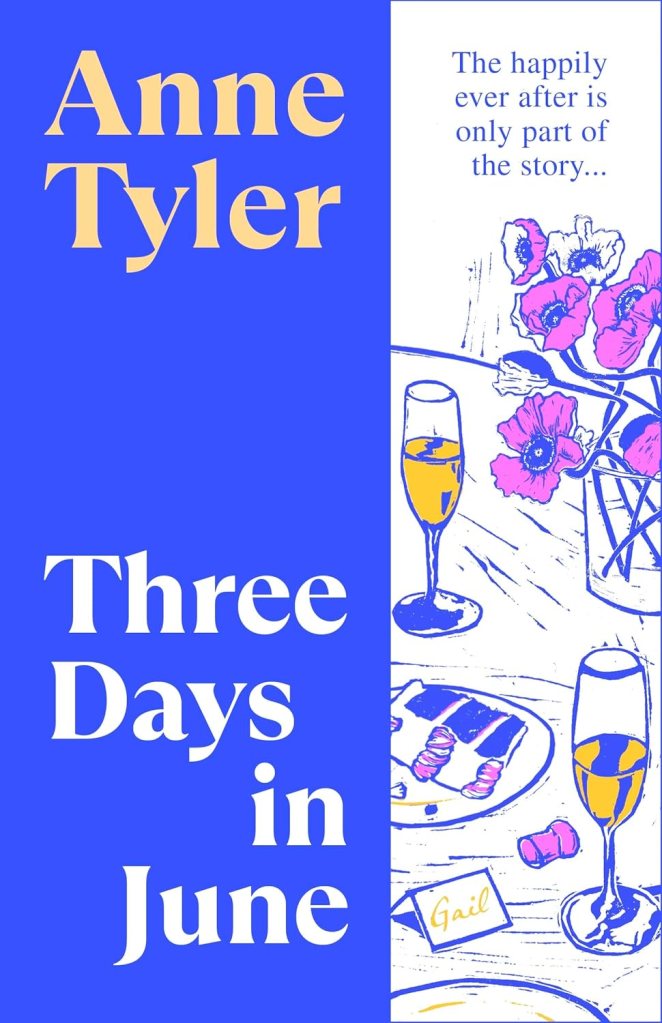

Three Days in June by Anne Tyler

(From my Most Anticipated list.) A delightful little book that I loved more than I expected to, for several reasons: the effective use of a wedding weekend as a way of examining what goes wrong in marriages and what we choose to live with versus what we can’t forgive; Gail’s first-person narration, a rarity for Tyler* and a decision that adds depth to what might otherwise have been a two-dimensional depiction of a woman whose people skills leave something to be desired; and the unexpected presence of a cat who brings warmth and caprice back into her home. (I read this soon after losing my old cat, and it was comforting to be reminded that cats and their funny ways are the same the world over.)

From Tyler’s oeuvre, this reminded me most of The Amateur Marriage and has a surprise Larry’s Party-esque ending. The discussion of the outmoded practice of tapping one’s watch is a neat tie-in to her recurring theme of the nature of time. And through the lunch out at a chic crab restaurant, she succeeds at making the Baltimore setting essential rather than incidental, more so than in much of her other work.

Gail is in the sandwich generation with a daughter just married and an old mother who’s just about independent. I appreciated that she’s 61 and contemplating retirement, but still feels as if she hasn’t a clue: “What was I supposed to do with the rest of my life? I’m too young for this, I thought. Not too old, as you might expect, but too young, too inept, too uninformed. How come there weren’t any grownups around? Why did everyone just assume I knew what I was doing?”

My only misgiving is that Tyler doesn’t quite get it right about the younger generation: women who are in their early thirties in 2023 (so born about 1990) wouldn’t be called Debbie and Bitsy. To some degree, Tyler’s still stuck back in the 1970s, but her observations about married couples and family dynamics are as shrewd as ever. Especially because of the novella length, I can recommend this to readers wanting to try Tyler for the first time. ![]()

*I’ve noted it in Earthly Possessions. Anywhere else?

Three Weeks in July: 7/7, The Aftermath, and the Deadly Manhunt by Adam Wishart and James Nally

July 7th is my wedding anniversary but before that, and ever since, it’s been known as the date of the UK’s worst terrorist attack, a sort of lesser 9/11 – and while reading this I felt the same way that I’ve felt reading books about 9/11: a sort of awed horror. Suicide bombers who were born in the UK but radicalized on trips to Islamic training camps in Pakistan set off explosions on three Underground trains and one London bus. I didn’t think my memories of 7/7 were strong, yet some names were incredibly familiar to me (chiefly Mohammad Sidique Khan, the leader of the attacks; Jean Charles de Menezes, the innocent Brazilian electrician shot dead on a Tube train when confused with a suspect in the 21/7 copycat plot – police were operating under a new shoot-to-kill policy and this was the tragic result).

Fifty-two people were killed that day, ranging in age from 20 to 60; 20 were not UK citizens, hailing from everywhere from Grenada to Mauritius. But a total of 770 people were injured. I found the authors’ recreation of events very gripping, though do be warned that there is a lot of gruesome medical and forensic detail about fatalities and injuries. They humanize the scale of events and make things personal by focusing on four individuals who were injured, even losing multiple limbs in some cases, but survived and now work in motivational speaking, disability services or survivor advocacy.

Fifty-two people were killed that day, ranging in age from 20 to 60; 20 were not UK citizens, hailing from everywhere from Grenada to Mauritius. But a total of 770 people were injured. I found the authors’ recreation of events very gripping, though do be warned that there is a lot of gruesome medical and forensic detail about fatalities and injuries. They humanize the scale of events and make things personal by focusing on four individuals who were injured, even losing multiple limbs in some cases, but survived and now work in motivational speaking, disability services or survivor advocacy.

What really got to me was thinking about all the hundreds of people who, 20 years on, still live with permanent pain, disability or grief because of the randomness of them or their loved ones getting caught up in a few misguided zealots’ plot. One detail that particularly struck me: with the Tube tunnels closed off at both ends while searchers recovered bodies, the temperature rose to 50 degrees C (122 degrees F), only exacerbating the stench. The book mostly avoids cliches and overwriting, though I did find myself skimming in places. It is based on the research done for a BBC documentary series and synthesizes a lot of material in an engaging way that does justice to the victims. ![]()

Have you read one or both of these?

Could you see yourself picking one of them up?

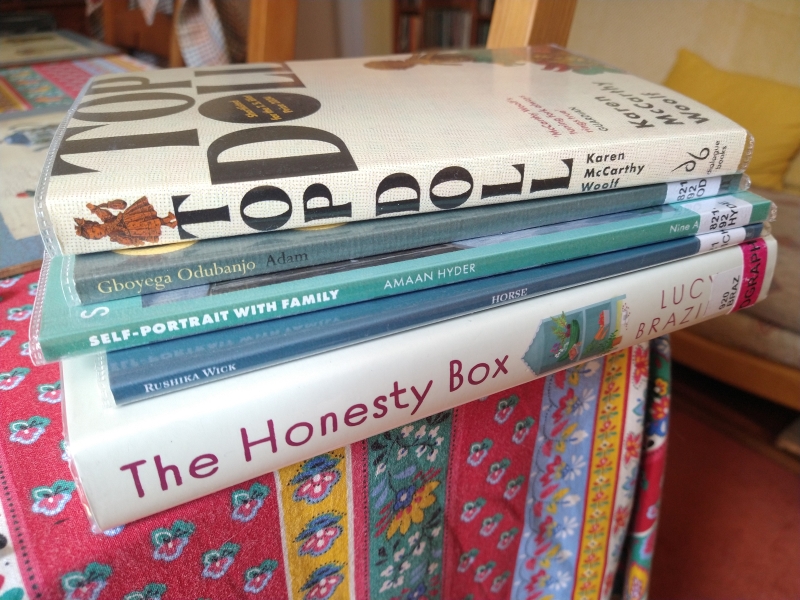

June Releases by Caroline Bird, Kathleen Jamie, Glynnis MacNicol and Naomi Westerman

These four books by women all incorporate life writing to an extent. Although the forms differ, a common theme – as in the other June releases I’ve reviewed, Sandwich and Others Like Me – is grappling with what a woman’s life should be, especially for those who have taken an unconventional path (i.e. are queer or childless) or are in midlife or later. I’ve got a poet up to her usual surreal shenanigans but with a new focus on lesbian parenting; a hybrid collection of poetry and prose giving snapshots of nature in crisis; an account of a writer’s hedonistic month in pandemic-era Paris; and mordant essays about death culture.

Ambush at Still Lake by Caroline Bird

Caroline Bird has become one of my favourite contemporary poets over the past few years. Her verse is joyously cheeky and absurdist. A great way to sample it is via her selected poems, Rookie. This seventh collection is muted by age and circumstance – multiple weddings and a baby – but still hilarious in places. Instead of rehab or hospital as in In These Days of Prohibition, the setting is mostly the domestic sphere. Even here, bizarre things happen. The police burst in at 4 a.m. for no particular reason; search algorithms and the baby monitor go haywire. Her brother calls to deliver a paranoid rant (in “Up and at ’Em”), while Nannie Edna’s dying wish is to dangle her great-grandson from her apartment window (in “Last Rites”). The clinic calls to announce that their sperm donor was a serial killer – then ‘oops, wrong vial, never mind!’ A toddler son’s strange and megalomaniac demands direct their days. My two favourites were “Ants,” in which a kitchen infestation signals general chaos, and “The Frozen Aisle,” in which a couple scrambles to finish the grocery shop and get home to bed before a rare horny moment passes. A lesbian pulp fiction cover, mischievous wit and topics of addiction and queer parenting: this is not your average poetry.

Caroline Bird has become one of my favourite contemporary poets over the past few years. Her verse is joyously cheeky and absurdist. A great way to sample it is via her selected poems, Rookie. This seventh collection is muted by age and circumstance – multiple weddings and a baby – but still hilarious in places. Instead of rehab or hospital as in In These Days of Prohibition, the setting is mostly the domestic sphere. Even here, bizarre things happen. The police burst in at 4 a.m. for no particular reason; search algorithms and the baby monitor go haywire. Her brother calls to deliver a paranoid rant (in “Up and at ’Em”), while Nannie Edna’s dying wish is to dangle her great-grandson from her apartment window (in “Last Rites”). The clinic calls to announce that their sperm donor was a serial killer – then ‘oops, wrong vial, never mind!’ A toddler son’s strange and megalomaniac demands direct their days. My two favourites were “Ants,” in which a kitchen infestation signals general chaos, and “The Frozen Aisle,” in which a couple scrambles to finish the grocery shop and get home to bed before a rare horny moment passes. A lesbian pulp fiction cover, mischievous wit and topics of addiction and queer parenting: this is not your average poetry.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

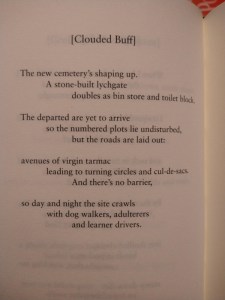

A sample poem:

Siblings

A woman gave birth

to the reincarnation

of Gilbert and Sullivan

or rather, two reincarnations:

one Gilbert, one Sullivan.

What are the odds

of both being resummoned

by the same womb

when they could’ve been

a blue dart frog

and a supply teacher

on separate continents?

Yet here they were, squidged

into a tandem pushchair

with their best work

behind them, still smarting

from the critical reception

of their final opera

described as ‘but an echo’

of earlier collaborations.

Cairn by Kathleen Jamie

As she approached age 60, Kathleen Jamie found her style changing. Whereas her other essay collections alternate extended nature or travel pieces with few-page vignettes, Cairn eschews longer material and instead alternates poems with micro-essays on climate crisis and outdoor experiences. In the prologue she calls these “distillations and observations. Testimonies” that she has assembled into “A cairn of sorts.”

As she approached age 60, Kathleen Jamie found her style changing. Whereas her other essay collections alternate extended nature or travel pieces with few-page vignettes, Cairn eschews longer material and instead alternates poems with micro-essays on climate crisis and outdoor experiences. In the prologue she calls these “distillations and observations. Testimonies” that she has assembled into “A cairn of sorts.”

As in Surfacing, she writes many of the autobiographical fragments in the second person. The book is melancholy at times, haunted by all that has been lost and will be lost in the future:

What do we sense on the moor but ghost folk,

ghost deer, even ghost wolf. The path itself is a

phantom, almost erased in ling and yellow tormentil (from “Moor”)

In “The Bass Rock,” Jamie laments the effect that bird flu has had on this famous gannet colony and wishes desperately for better news:

The light glances on the water. The haze clears, and now the rock is visible; it looks depleted. But hallelujah, a pennant of twenty-odd gannets is passing, flying strongly, now rising now falling They’ll be Bass Rock birds. What use the summer sunlight, if it can’t gleam on a gannet’s back? You can only hope next year will be different. Stay alive! You call after the flying birds. Stay alive!

Natural wonders remind her of her own mortality and the insignificance of human life against deep time. “I can imagine the world going on without me, which one doesn’t at 30.” She questions the value of poetry in a time of emergency: “If we are entering a great dismantling, we can hardly expect lyric to survive. How to write a lyric poem?” (from “Summer”). The same could be said of any human endeavour in the face of extinction: We question the point but still we continue.

My two favourite pieces were “The Handover,” about going on an environmental march with her son and his friends in Glasgow and comparing it with the protests of her time (Greenham Common and nuclear disarmament) – doom and gloom was ever thus – and the title poem, which piles natural image on image like a cone of stones. Although I prefer the depth of Jamie’s other books to the breadth of this one, she is an invaluable nature writer for her wisdom and eloquence, and I am grateful we have heard from her again after five years.

With thanks to Sort Of Books for the free copy for review.

I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself: One Woman’s Pursuit of Pleasure in Paris by Glynnis MacNicol

I loved New York City freelance writer Glynnis MacNicol’s No One Tells You This (2018), which approached her 40th year as an adventure into the unknown. This second memoir is similarly frank and intrepid as MacNicol examines the unconscious rules that people set for women in their mid-forties and gleefully flouts them, remaining single and childfree and delighting in the freedom that allows her to book a month in Paris on a whim. She knows that she is an anomaly for being “untethered”; “I am ready for anything. To be anyone.”

I loved New York City freelance writer Glynnis MacNicol’s No One Tells You This (2018), which approached her 40th year as an adventure into the unknown. This second memoir is similarly frank and intrepid as MacNicol examines the unconscious rules that people set for women in their mid-forties and gleefully flouts them, remaining single and childfree and delighting in the freedom that allows her to book a month in Paris on a whim. She knows that she is an anomaly for being “untethered”; “I am ready for anything. To be anyone.”

This takes place in August 2021, when some pandemic restrictions were still in force, and she found the city – a frequent destination for her over the years – drained of locals, who were all en vacances, and largely empty of tourists, too. Although there was still a queue for the Mona Lisa, she otherwise found the Louvre very quiet, and could ride her borrowed bike through the streets without having to look out for cars. She and her single girlfriends met for rosé-soaked brunches and picnics, joined outdoor dance parties and took an island break.

And then there was the sex. MacNicol joined a hook-up app called Fruitz and met all sorts of men. She refused to believe that, just because she was 46 going on 47, she should be invisible or demure. “All the attention feels like pure oxygen. Anything is possible.” Seeing herself through the eyes of an enraptured 27-year-old Italian reminded her that her body was beautiful even if it wasn’t what she remembered from her twenties (“there is, on average, a five-year gap between current me being able to enjoy the me in the photos”). The book’s title is something she wrote while messaging with one of her potential partners.

As I wrote yesterday about Others Like Me, there are plenty of childless role models but you may have to look a bit harder for them. MacNicol does so by tracking down the Paris haunts of women writers such as Edith Wharton and Colette. She also interrogates this idea of women living a life of pleasure by researching the “odalisque” in 18th- and 19th-century art, as in the François Boucher painting on the cover. This was fun, provocative and thoughtful all at once; well worth seeking out for summer reading and armchair travelling.

(Read via Edelweiss) Published in the USA by Penguin Life/Random House.

Happy Death Club: Essays on Death, Grief & Bereavement across Cultures by Naomi Westerman

Like Erica Buist (This Party’s Dead) and Caitlin Doughty (Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, From Here to Eternity and Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs?), playwright Naomi Westerman finds the comical side of death. Part of 404 Ink’s Inklings series (“Big ideas, pocket-sized books” – perfect for anyone looking for short nonfiction for Novellas in November!), this is a collection of short essays about her own experiences of bereavement as well as her anthropological research into rituals and beliefs around death. “The Rat King of South London” is about her father’s sudden death from an abdominal aneurysm. An instantaneous death is a good one, she contends. More than 160,000 people die every day, and what to do with all those bodies is a serious question. A subversive sense of humour is there right from the start, as she gives a rundown of interment options. “Mummification: Beloved by Ancient Egyptians and small children going through their Ancient Egypt phase, it’s a classic for a reason!” Meanwhile, she legally owns her father’s plot so also buries dead pet rats there.

Like Erica Buist (This Party’s Dead) and Caitlin Doughty (Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, From Here to Eternity and Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs?), playwright Naomi Westerman finds the comical side of death. Part of 404 Ink’s Inklings series (“Big ideas, pocket-sized books” – perfect for anyone looking for short nonfiction for Novellas in November!), this is a collection of short essays about her own experiences of bereavement as well as her anthropological research into rituals and beliefs around death. “The Rat King of South London” is about her father’s sudden death from an abdominal aneurysm. An instantaneous death is a good one, she contends. More than 160,000 people die every day, and what to do with all those bodies is a serious question. A subversive sense of humour is there right from the start, as she gives a rundown of interment options. “Mummification: Beloved by Ancient Egyptians and small children going through their Ancient Egypt phase, it’s a classic for a reason!” Meanwhile, she legally owns her father’s plot so also buries dead pet rats there.

Other essays are about taking her mother’s ashes along on world travels, the funeral industry and “red market” sales of body parts, grief as a theme in horror films, the fetishization of dead female bodies, Mexico’s Day of the Dead festivities, and true crime obsession. In “Batman,” an excerpt from one of her plays, she goes to have a terrible cup of tea with the man she believes to be responsible for her mother’s death – a violent one, after leaving an abusive relationship. She also used the play to host an on-stage memorial for her mother since she wasn’t able to sit shiva. In the final title essay, Westerman tours lots of death cafés and finds comfort in shared experiences. These pieces are all breezy, amusing and easy to read, so it’s a shame that this small press didn’t achieve proper proofreading, making for a rather sloppy text, and that the content was overall too familiar for me.

With thanks to 404 Ink and publicist Claire Maxwell for the free copy for review.

Does one or more of these catch your eye?

What June releases can you recommend?

Three “Love” or “Heart” Books for Valentine’s Day: Ephron, Lischer and Nin

Every year I say I’m really not a Valentine’s Day person and yet put together a themed post featuring books that have “Love” or a similar word in the title. This is the eighth year in a row, in fact (after 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2023)! Today I’m looking at two classic novellas, one of them a reread and the other my first taste of a writer I’d expected more from; and a wrenching, theologically oriented bereavement memoir.

Heartburn by Nora Ephron (1983)

I’d already pulled this out for my planned reread of books published in my birth year, so it’s pleasing that it can do double duty here. I can’t say it better than my original 2013 review:

The funniest book you’ll ever read about heartbreak and betrayal, this is full of wry observations about the compromises we make to marry – and then stay married to – people who are very different from us. Ephron readily admitted that her novel is more than a little autobiographical: it’s based on the breakdown of her second marriage to investigative journalist Carl Bernstein (All the President’s Men), who had an affair with a ludicrously tall woman – one element she transferred directly into Heartburn.

Ephron’s fictional counterpart is Rachel Samstad, a New Yorker who writes cookbooks or, rather, memoirs with recipes – before that genre really took off. Seven months pregnant with her second child, she has just learned that her second husband is having an affair. What follows is her uproarious memories of life, love and failed marriages. Indeed, as Ephron reflected in a 2004 introduction, “One of the things I’m proudest of is that I managed to convert an event that seemed to me hideously tragic at the time to a comedy – and if that’s not fiction, I don’t know what is.”

As one might expect from a screenwriter, there is a cinematic – that is, vivid but not-quite-believable – quality to some of the moments: the armed robbery of Rachel’s therapy group, her accidentally flinging an onion into the audience during a cooking demonstration, her triumphant throw of a key lime pie into her husband’s face in the final scene. And yet Ephron was again drawing on experience: a friend’s therapy group was robbed at gunpoint, and she’d always filed the experience away in a mental drawer marked “Use This Someday” – “My mother taught me many things when I was growing up, but the main thing I learned from her is that everything is copy.” This is one of celebrity chef Nigella Lawson’s favorite books ever, for its mixture of recipes and rue, comfort food and folly. It’s a quick read, but a substantial feast for the emotions.

Sometimes I wonder why I bother when I can’t improve on reviews I wrote over a decade ago (see also another upcoming reread). What I would add now, without disputing any of the above, is that there’s more bitterness to the tone than I’d recalled, even though Ephron does, yes, play it for laughs. But also, some of the humour hasn’t aged well, especially where based on race/culture or sexuality. I’d forgotten that Rachel’s husband isn’t the only cheater here; pretty much every couple mentioned is currently working through the aftermath of an affair or has survived one in the past. In one of these, the wife who left for a woman is described not as a lesbian but by another word, each time, which felt unkind rather than funny.

Sometimes I wonder why I bother when I can’t improve on reviews I wrote over a decade ago (see also another upcoming reread). What I would add now, without disputing any of the above, is that there’s more bitterness to the tone than I’d recalled, even though Ephron does, yes, play it for laughs. But also, some of the humour hasn’t aged well, especially where based on race/culture or sexuality. I’d forgotten that Rachel’s husband isn’t the only cheater here; pretty much every couple mentioned is currently working through the aftermath of an affair or has survived one in the past. In one of these, the wife who left for a woman is described not as a lesbian but by another word, each time, which felt unkind rather than funny.

Still, the dialogue, the scenes, the snarky self-portrayal: it all pops. This was autofiction before that was a thing, but anyone working in any genre could learn how to write readable content by studying Ephron. “‘I don’t have to make everything into a joke,’ I said. ‘I have to make everything into a story.’ … I think you often have that sense when you write – that if you can spot something in yourself and set it down on paper, you’re free of it. And you’re not, of course; you’ve just managed to set it down on paper, that’s all.” (Little Free Library)

My original rating (2013):

My rating now:

Stations of the Heart: Parting with a Son by Richard Lischer (2013)

“What we had taken to be a temporary unpleasantness had now burrowed deep into the family pulp and was gnawing us from the inside out.” Like all life writing, the bereavement memoir has two tasks: to bear witness and to make meaning. From a distance that just happens to be Mary Karr’s prescribed seven years, Lischer opens by looking back on the day when his 33-year-old son Adam called to tell him that his melanoma, successfully treated the year before, was back. Tests revealed that the cancer’s metastases were everywhere, including in his brain, and were “innumerable,” a word that haunted Lischer and his wife, their daughter, and Adam’s wife, who was pregnant with their first child.

The next few months were a Calvary of sorts, and Lischer, an emeritus professor at Duke Divinity School, draws deliberate parallels with the biblical and liturgical preparations for Good Friday that feel appropriate for this Ash Wednesday. Lischer had no problem with Adam’s late-life conversion from Protestantism to Catholicism, whose rites he followed with great piety in his final summer. He traces Adam and Jenny’s daily routines as well as his own helpless attendance at hospital appointments. Doped up on painkillers, Adam attended one last Father’s Day baseball game with him; one last Fourth of July picnic. Everyone so desperately wanted him to keep going long enough to meet his baby girl. To think that she is now a young woman and has opened all the presents Adam bought to leave behind for her first 18 birthdays.

The next few months were a Calvary of sorts, and Lischer, an emeritus professor at Duke Divinity School, draws deliberate parallels with the biblical and liturgical preparations for Good Friday that feel appropriate for this Ash Wednesday. Lischer had no problem with Adam’s late-life conversion from Protestantism to Catholicism, whose rites he followed with great piety in his final summer. He traces Adam and Jenny’s daily routines as well as his own helpless attendance at hospital appointments. Doped up on painkillers, Adam attended one last Father’s Day baseball game with him; one last Fourth of July picnic. Everyone so desperately wanted him to keep going long enough to meet his baby girl. To think that she is now a young woman and has opened all the presents Adam bought to leave behind for her first 18 birthdays.

The facts of the story are heartbreaking enough, but Lischer’s prose is a perfect match: stately, resolute and weighted with spiritual allusion, yet never morose. He approaches the documenting of his son’s too-short life with a sense of sacred duty: “I have acquired a new responsibility: I have become the interpreter of his death. God, I must do a better job. … I kissed his head and thanked him for being my son. I promised him then that his death would not ruin my life.” This memoir brought back so much about my brother-in-law’s death from brain cancer in 2015, from the “TEAM [ADAM/GARNET]” T-shirts to Adam’s sister’s remark, “I never dreamed this would be our family’s story.” We’re not alone. (Remainder book from the Bowie, Maryland Dollar Tree)

A Spy in the House of Love by Anaïs Nin (1954)

I’d heard Nin spoken of in the same breath as D.H. Lawrence, so thought I might similarly appreciate her because of, or despite, comically overblown symbolism around sex. I think I was also expecting something more titillating? (I guess I had this confused for Delta of Venus, her only work that would be shelved in an Erotica section.) Many have tried to make a feminist case for this novella about Sabina, an early liberated woman in New York City who has extramarital sex with four other men who appeal to her for various not particularly good reasons (the traumatized soldier whom she comforts like a mother; the exotic African drummer – “Sabina did not feel guilty for drinking of the tropics through Mambo’s body”). She herself states, “I want to trespass boundaries, erase all identifications, anything which fixes one permanently into one mould, one place without hope of change.” The most interesting aspect of the book was Sabina’s questioning of whether she inherited her promiscuity from her father (it’s tempting to read this autobiographically as Nin’s own father left the family for another woman, a foundational wound in her life).

I’d heard Nin spoken of in the same breath as D.H. Lawrence, so thought I might similarly appreciate her because of, or despite, comically overblown symbolism around sex. I think I was also expecting something more titillating? (I guess I had this confused for Delta of Venus, her only work that would be shelved in an Erotica section.) Many have tried to make a feminist case for this novella about Sabina, an early liberated woman in New York City who has extramarital sex with four other men who appeal to her for various not particularly good reasons (the traumatized soldier whom she comforts like a mother; the exotic African drummer – “Sabina did not feel guilty for drinking of the tropics through Mambo’s body”). She herself states, “I want to trespass boundaries, erase all identifications, anything which fixes one permanently into one mould, one place without hope of change.” The most interesting aspect of the book was Sabina’s questioning of whether she inherited her promiscuity from her father (it’s tempting to read this autobiographically as Nin’s own father left the family for another woman, a foundational wound in her life).

Come on, though, “fecundated,” “fecundation” … who could take such vocabulary seriously? Or this sex writing (snort!): “only one ritual, a joyous, joyous, joyous impaling of woman on a man’s sensual mast.” I charge you to use the term “sensual mast” wherever possible in the future. (Secondhand – Oxfam, Newbury)

But hey, check out my score for the Faber Valentine’s quiz!

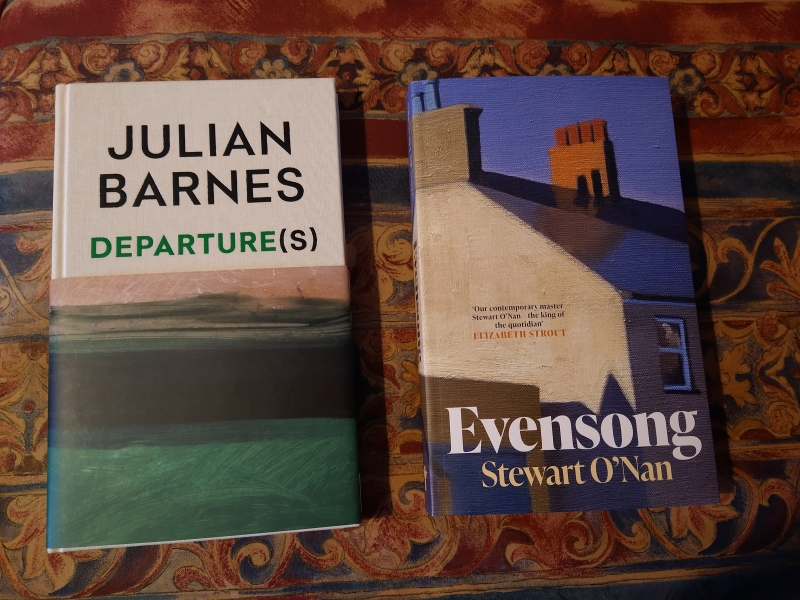

He parcels out bits of this story in between pondering involuntary autobiographical memory (IAM), his “incurable but manageable” condition, and his possible legacy. He hopes he’ll be exonerated due to waiting until Stephen and Jean were dead to write about them and adopting Jean’s old Jack Russell terrier, Jimmy. His late wife, Pat Kavanagh, is never far from his thoughts, and he documents other losses among his peers, including Martin Amis (d. 2023 – for a short book, this is curiously dated, as if it hung around for years unfinished). There are also, as one would expect from Barnes, occasional references to French literature. Confident narration gives the sense of an author in full control of his material. Yet I found much of it tedious. He’s addressed subjectivity much more originally in other works, and the various strands here feel like incomplete ideas shoehorned into one volume.

He parcels out bits of this story in between pondering involuntary autobiographical memory (IAM), his “incurable but manageable” condition, and his possible legacy. He hopes he’ll be exonerated due to waiting until Stephen and Jean were dead to write about them and adopting Jean’s old Jack Russell terrier, Jimmy. His late wife, Pat Kavanagh, is never far from his thoughts, and he documents other losses among his peers, including Martin Amis (d. 2023 – for a short book, this is curiously dated, as if it hung around for years unfinished). There are also, as one would expect from Barnes, occasional references to French literature. Confident narration gives the sense of an author in full control of his material. Yet I found much of it tedious. He’s addressed subjectivity much more originally in other works, and the various strands here feel like incomplete ideas shoehorned into one volume. Often, the short chapters are vignettes starring one or more of the central characters. When Joan has a fall down her stairs and lands in rehab, Kitzi takes over as de facto HDC leader. A musical couple’s hoarding and cat colony become her main preoccupation. Emily deals with family complications I didn’t fully understand for want of backstory, and Arlene realizes dementia is affecting her daily life. Susie, the “baby” of the group at 63, takes in Joan’s cat, Oscar, and meets someone through online dating. The novel covers four months of 2022–23, anchored by a string of holidays (Halloween, Thanksgiving, Christmas); events such as John Fetterman’s election and ongoing Covid precautions; and the cycle of the Church year.

Often, the short chapters are vignettes starring one or more of the central characters. When Joan has a fall down her stairs and lands in rehab, Kitzi takes over as de facto HDC leader. A musical couple’s hoarding and cat colony become her main preoccupation. Emily deals with family complications I didn’t fully understand for want of backstory, and Arlene realizes dementia is affecting her daily life. Susie, the “baby” of the group at 63, takes in Joan’s cat, Oscar, and meets someone through online dating. The novel covers four months of 2022–23, anchored by a string of holidays (Halloween, Thanksgiving, Christmas); events such as John Fetterman’s election and ongoing Covid precautions; and the cycle of the Church year.

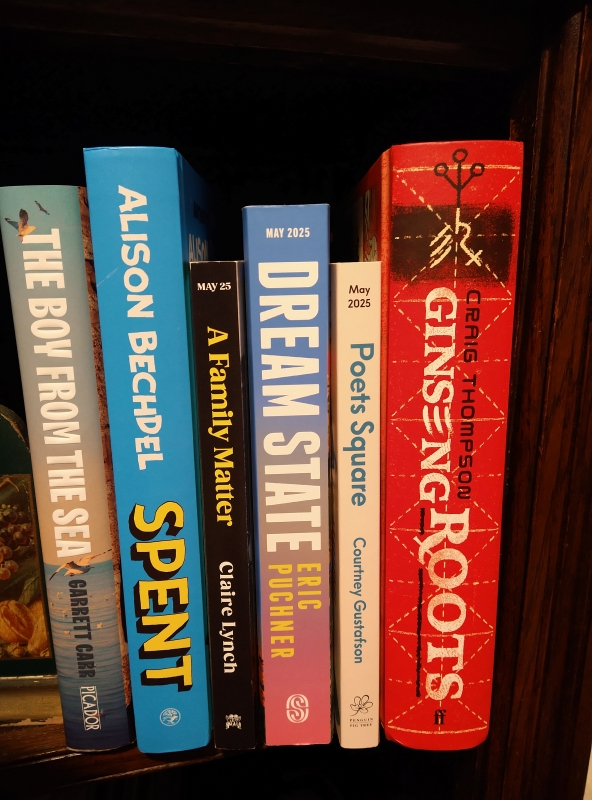

The Boy from the Sea by Garrett Carr: I was entranced by this story of an Irish family in the 1970s–80s: Ambrose, a fisherman left behind by technology; his wife Christine, walked all over by her belligerent father and sister; their son Declan, a budding foodie; and the title character, Brendan, a foundling they adopt and raise. Narrated by a chorus of village voices, this debut has the heart of Claire Keegan and the humour of Paul Murray. It reimagines biblical narratives, too: Cain and Abel, Jacob and Esau (brotherly rivalry!); Job and more.

The Boy from the Sea by Garrett Carr: I was entranced by this story of an Irish family in the 1970s–80s: Ambrose, a fisherman left behind by technology; his wife Christine, walked all over by her belligerent father and sister; their son Declan, a budding foodie; and the title character, Brendan, a foundling they adopt and raise. Narrated by a chorus of village voices, this debut has the heart of Claire Keegan and the humour of Paul Murray. It reimagines biblical narratives, too: Cain and Abel, Jacob and Esau (brotherly rivalry!); Job and more.

I died and went

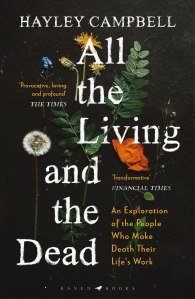

I died and went I’ve read the first two chapters of a long-neglected review copy of All the Living and the Dead by Hayley Campbell (2022), in which she shadows various individuals who work in the death industry, starting with a funeral director and the head of anatomy services for the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. In Victorian times, corpses were stolen for medical students to practice on. These days, more people want to donate their bodies to science than can usually be accommodated. The Mayo Clinic receives upwards of 200 cadavers a year and these are the basis for many practical lessons as trainees prepare to perform surgery on the living. Campbell’s prose is journalistic, detailed and matter-of-fact, but I’m struggling with the very small type in my paperback. Upcoming chapters will consider a death mask sculptor, a trauma cleaner, a gravedigger, and more. If you’ve enjoyed Caitlin Doughty’s books, try this.

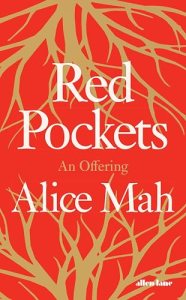

I’ve read the first two chapters of a long-neglected review copy of All the Living and the Dead by Hayley Campbell (2022), in which she shadows various individuals who work in the death industry, starting with a funeral director and the head of anatomy services for the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. In Victorian times, corpses were stolen for medical students to practice on. These days, more people want to donate their bodies to science than can usually be accommodated. The Mayo Clinic receives upwards of 200 cadavers a year and these are the basis for many practical lessons as trainees prepare to perform surgery on the living. Campbell’s prose is journalistic, detailed and matter-of-fact, but I’m struggling with the very small type in my paperback. Upcoming chapters will consider a death mask sculptor, a trauma cleaner, a gravedigger, and more. If you’ve enjoyed Caitlin Doughty’s books, try this. I’m halfway through Red Pockets: An Offering by Alice Mah (2025) from the library. I borrowed it because it was on the Wainwright Prize for Conservation Writing shortlist. During the Qingming Festival, the Chinese return to their hometowns to honour their ancestors. By sweeping their tombs and making offerings, they prevent the dead from coming back as hungry ghosts. When Mah, who grew up in Canada and now lives in Scotland, returns to South China with a cousin in 2017, she finds little trace of her ancestors but plenty of pollution and ecological degradation. Their grandfather wrote a memoir about his early life and immigration to Canada. In the present day, the cousins struggle to understand cultural norms such as gifting red envelopes of money to all locals. This is easy reading but slightly dull; it feels like Mah included every detail from her trips simply because she had the material, whereas memoirs need to be more selective. But I’m reminded of the works of Jessica J. Lee, which is no bad thing.

I’m halfway through Red Pockets: An Offering by Alice Mah (2025) from the library. I borrowed it because it was on the Wainwright Prize for Conservation Writing shortlist. During the Qingming Festival, the Chinese return to their hometowns to honour their ancestors. By sweeping their tombs and making offerings, they prevent the dead from coming back as hungry ghosts. When Mah, who grew up in Canada and now lives in Scotland, returns to South China with a cousin in 2017, she finds little trace of her ancestors but plenty of pollution and ecological degradation. Their grandfather wrote a memoir about his early life and immigration to Canada. In the present day, the cousins struggle to understand cultural norms such as gifting red envelopes of money to all locals. This is easy reading but slightly dull; it feels like Mah included every detail from her trips simply because she had the material, whereas memoirs need to be more selective. But I’m reminded of the works of Jessica J. Lee, which is no bad thing. Perry traces the physical changes in David as he moved with alarming alacrity from normal, if slowed, daily life to complete dependency to death’s door. At the same time, she is aware that this is only her own perspective on events, so she records her responses and emotional state and, to a lesser extent, her husband’s. Her quiver of allusions is perfectly chosen and she lands on just the right tone: direct but tender. Because of her and David’s shared upbringing, the points of reference are often religious, but not obtrusive. My only wish is to have gotten more of a sense of David alive. There’s a brief section on his life at the start, mirrored by a short “Afterlife” chapter at the end telling what succeeded his death. But the focus is very much on the short period of his illness and the days of his dying. During this time, he appears confused and powerless. He barely says anything beyond “I’m in a bit of a muddle,” to refer to anything from incontinence to an inability to eat. At first I thought this was infantilizing him. But I came to see it as a way of reflecting how death strips everything away.

Perry traces the physical changes in David as he moved with alarming alacrity from normal, if slowed, daily life to complete dependency to death’s door. At the same time, she is aware that this is only her own perspective on events, so she records her responses and emotional state and, to a lesser extent, her husband’s. Her quiver of allusions is perfectly chosen and she lands on just the right tone: direct but tender. Because of her and David’s shared upbringing, the points of reference are often religious, but not obtrusive. My only wish is to have gotten more of a sense of David alive. There’s a brief section on his life at the start, mirrored by a short “Afterlife” chapter at the end telling what succeeded his death. But the focus is very much on the short period of his illness and the days of his dying. During this time, he appears confused and powerless. He barely says anything beyond “I’m in a bit of a muddle,” to refer to anything from incontinence to an inability to eat. At first I thought this was infantilizing him. But I came to see it as a way of reflecting how death strips everything away.

Often, there is a hint of menace, whether the topic is salmon fishing, raspberry picking or the history of a lost ring. “The Clear and Rolling Water” has the atmosphere of a Scottish folk ballad, which made it perfect reading for our recent

Often, there is a hint of menace, whether the topic is salmon fishing, raspberry picking or the history of a lost ring. “The Clear and Rolling Water” has the atmosphere of a Scottish folk ballad, which made it perfect reading for our recent  I’d only ever read King’s On Writing and worried I wouldn’t be able to handle his fiction. I could never watch a horror film, but somehow the same content was okay in print. For half the length or more, it’s more of a mildly dread-laced, John Irving-esque novel about how we deal with the reality of death. Dr. Louis Creed and his family – wife Rachel, five-year-old daughter Ellie, two-year-old son Gage and cat Church (short for Winston Churchill) – have recently moved from Chicago to Maine for him to take up a post as head of University Medical Services. Their 83-year-old neighbour across the street, Judson Crandall, becomes a sort of surrogate father to Louis, warning them about the dangerous highway that separates their houses and initiating them with a tour of the pet cemetery and Micmac burial ground that happen to be on their property. Things start getting weird early on: Louis’s first day on the job sees a student killed by a car while jogging; the young man’s cryptic dying words are about the pet cemetery, and he then visits Louis in a particularly vivid dream.

I’d only ever read King’s On Writing and worried I wouldn’t be able to handle his fiction. I could never watch a horror film, but somehow the same content was okay in print. For half the length or more, it’s more of a mildly dread-laced, John Irving-esque novel about how we deal with the reality of death. Dr. Louis Creed and his family – wife Rachel, five-year-old daughter Ellie, two-year-old son Gage and cat Church (short for Winston Churchill) – have recently moved from Chicago to Maine for him to take up a post as head of University Medical Services. Their 83-year-old neighbour across the street, Judson Crandall, becomes a sort of surrogate father to Louis, warning them about the dangerous highway that separates their houses and initiating them with a tour of the pet cemetery and Micmac burial ground that happen to be on their property. Things start getting weird early on: Louis’s first day on the job sees a student killed by a car while jogging; the young man’s cryptic dying words are about the pet cemetery, and he then visits Louis in a particularly vivid dream.

I appreciated this quote from Women by Chloe Caldwell, whose narrator works in a library: “Books are like doctors and I am lucky to have unlimited access to them during this time. A perk of the library.” Bibliotherapy works!

I appreciated this quote from Women by Chloe Caldwell, whose narrator works in a library: “Books are like doctors and I am lucky to have unlimited access to them during this time. A perk of the library.” Bibliotherapy works!

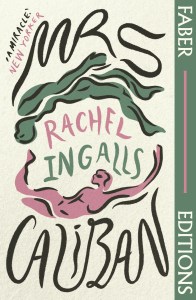

Dorothy Caliban is a California housewife whose unhappy marriage to Fred has been strained by the death of their young son (an allergic reaction during routine surgery) and a later miscarriage. When we read that Dorothy believes the radio has started delivering personalized messages to her, we can’t then be entirely sure if its news report about a dangerous creature escaped from an oceanographic research centre is real or a manifestation of her mental distress. Even when the 6’7” frog-man, Larry, walks into her kitchen and becomes her lover and secret lodger, I had to keep asking myself: is he ever independently seen by another character? Can these actions be definitively attributed to him? So perhaps this is a novella to experience on two levels. Take it at face value and it’s a lighthearted caper of duelling adulterers and revenge, with a pointed message about the exploitation of the Other. Or interpret it as a midlife fantasy of sexual rejuvenation and an attentive partner (“[Larry] said that he enjoyed housework. He was good at it and found it interesting”):

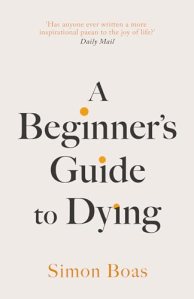

Dorothy Caliban is a California housewife whose unhappy marriage to Fred has been strained by the death of their young son (an allergic reaction during routine surgery) and a later miscarriage. When we read that Dorothy believes the radio has started delivering personalized messages to her, we can’t then be entirely sure if its news report about a dangerous creature escaped from an oceanographic research centre is real or a manifestation of her mental distress. Even when the 6’7” frog-man, Larry, walks into her kitchen and becomes her lover and secret lodger, I had to keep asking myself: is he ever independently seen by another character? Can these actions be definitively attributed to him? So perhaps this is a novella to experience on two levels. Take it at face value and it’s a lighthearted caper of duelling adulterers and revenge, with a pointed message about the exploitation of the Other. Or interpret it as a midlife fantasy of sexual rejuvenation and an attentive partner (“[Larry] said that he enjoyed housework. He was good at it and found it interesting”): I hadn’t heard of the author but picked this up from the Bestseller display in my library. It’s a posthumous collection of writings, starting with a few articles Boas wrote for his local newspaper, the Jersey Evening Post, about his experience of terminal illness. Diagnosed late on with incurable throat cancer, Boas spent his last year smoking and drinking Muscadet. Looking back at the privilege and joys of his life, he knew he couldn’t complain too much about dying at 46. He had worked in charitable relief in wartorn regions, finishing his career as director of Jersey Overseas Aid. The articles are particularly witty. After learning his cancer had metastasized to his lungs, he wrote, “The prognosis is not quite ‘Don’t buy any green bananas’, but it’s pretty close to ‘Don’t start any long books’.” While I admired the perspective and equanimity of the other essays, most of their topics were overly familiar for me (gratitude, meditation, therapy, what (not) to do/say to the dying). His openness to religion and use of psychedelics were a bit more interesting. It’s hard to write anything original about dying, and his determined optimism – to the extent of downplaying the environmental crisis – grated. (Public library) [138 pages]

I hadn’t heard of the author but picked this up from the Bestseller display in my library. It’s a posthumous collection of writings, starting with a few articles Boas wrote for his local newspaper, the Jersey Evening Post, about his experience of terminal illness. Diagnosed late on with incurable throat cancer, Boas spent his last year smoking and drinking Muscadet. Looking back at the privilege and joys of his life, he knew he couldn’t complain too much about dying at 46. He had worked in charitable relief in wartorn regions, finishing his career as director of Jersey Overseas Aid. The articles are particularly witty. After learning his cancer had metastasized to his lungs, he wrote, “The prognosis is not quite ‘Don’t buy any green bananas’, but it’s pretty close to ‘Don’t start any long books’.” While I admired the perspective and equanimity of the other essays, most of their topics were overly familiar for me (gratitude, meditation, therapy, what (not) to do/say to the dying). His openness to religion and use of psychedelics were a bit more interesting. It’s hard to write anything original about dying, and his determined optimism – to the extent of downplaying the environmental crisis – grated. (Public library) [138 pages]  I’ve reviewed one of Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s books for a previous NovNov:

I’ve reviewed one of Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s books for a previous NovNov:  I was always going to read this because I’m a big fan of Susan Allen Toth’s work, including her trilogy of cosy

I was always going to read this because I’m a big fan of Susan Allen Toth’s work, including her trilogy of cosy

Mitchell was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s in her fifties and was an energetic campaigner for dementia education and research for the last decade of her life. With a co-author, she wrote three books that give a valuable insider’s view of life with dementia:

Mitchell was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s in her fifties and was an energetic campaigner for dementia education and research for the last decade of her life. With a co-author, she wrote three books that give a valuable insider’s view of life with dementia: