Weatherglass Novella Prize 2026

Following up on the shortlist news I shared in November: Ali Smith has chosen two winners for the second annual Weatherglass Novella Prize. Both of these have changed title since they were submitted as manuscripts (From the Smallest Things to The Hyena’s Daughter; Shougani to Pink Soap). I’m particularly interested in Jones’s novel about Mary Shelley and her sister and stepsister. And the Gaston has a brilliant cover!

Here’s what Ali Smith had to say about the winning books, courtesy of the Weatherglass Substack:

The Hyena’s Daughter by Jupiter Jones

(to be published in April 2026)

“This novella tells the far-too-untold story of a c19th sisterhood, that of the daughters of Mary Wollstonecraft: Fanny Imlay and Mary Shelley, the famed writer of Frankenstein, plus their step[-]sister Claire Clairmont. Are they the three graces? The fates? They’re women, as alive and breathing and rebellious and analytical as you and me, and well aware and critical of the hemmed-in nature they’re expected to accept as women of their time, a time of ‘a new way of thinking, a new-world independence, a revolutionary world.’

“This novella tells the far-too-untold story of a c19th sisterhood, that of the daughters of Mary Wollstonecraft: Fanny Imlay and Mary Shelley, the famed writer of Frankenstein, plus their step[-]sister Claire Clairmont. Are they the three graces? The fates? They’re women, as alive and breathing and rebellious and analytical as you and me, and well aware and critical of the hemmed-in nature they’re expected to accept as women of their time, a time of ‘a new way of thinking, a new-world independence, a revolutionary world.’

“It features their connection to Percy Bysshe Shelley – ‘how could we not love him, with his lofty ethics and words that flew like birds?’ – and many of the other contemporary poets and thinkers of the time. Pacy and assured, it turns its history to life from fragment to sensuous fragment. If the dead brought to life is to be Mary Shelley’s theme, this novella asks what the real source of life spirit is, the vital spark. This novella, full of detail and richesse, is a piece of vitality in itself.”

Pink Soap by Anju Gaston

(to be published in June 2026)

“‘I ask the internet the difference between something being too close to the bone and something being too close to home.’ This funny and terrifying book is a study of what and how things mean, and don’t, in our latest machine age. In it something unforgivable has happened. The main character in this novella, seemingly numbed but bristling with blade-sharp understanding, is only just holding things together and trying to work out how to heal. So she travels to Japan in a search for the other half of a fragmented family. Or is it the world itself that has fragmented?

“‘I ask the internet the difference between something being too close to the bone and something being too close to home.’ This funny and terrifying book is a study of what and how things mean, and don’t, in our latest machine age. In it something unforgivable has happened. The main character in this novella, seemingly numbed but bristling with blade-sharp understanding, is only just holding things together and trying to work out how to heal. So she travels to Japan in a search for the other half of a fragmented family. Or is it the world itself that has fragmented?

“Pink Soap examines the massive everyday pressures we’re all under with real wit and style. It is pristine, brilliant, smart beyond belief. I sense it becoming as much a classic for now as Plath’s The Bell Jar has been for the decades behind us.”

Submissions have already opened for the 2027 Prize. More information is here.

Seascraper by Benjamin Wood (#NovNov25 Buddy Read)

Seascraper is set in what appears to be the early 1960s yet could easily be a century earlier because of the protagonist’s low-tech career. Thomas Flett lives with his mother in fictional Longferry in northwest England and carries on his grandfather’s tradition of fishing with a horse and cart. Each day he trawls the seabed for shrimp – sometimes twice a day when the tide allows – and sells his catch to local restaurants. At around 20 years old, Thomas still lives with his mother, who is disabled by obesity and chronic pain. He’s the sole breadwinner in the household and there’s an unusual dynamic between them in that his mother isn’t all that many years older, having fallen pregnant by a teacher while she was still in school.

Their life is just a mindless trudge of work with cosy patterns of behaviour in between … He wants to wake up every morning with a better purpose.

It’s a humdrum, hardscrabble existence, and Thomas longs for a bigger and more creative life, which he hopes he might achieve through his folk music hobby – or a chance encounter with an American filmmaker. Edgar Acheson is working on a big-screen adaptation of a novel; to save money, it will be filmed here in Merseyside rather than in coastal Maine where it’s set. One day he turns up at the house asking Thomas to be his guide to the sands. Thomas reluctantly agrees to take Edgar out one evening, even though it will mean missing out on an open mic night. They nearly get lost in the fog and the cart starts to sink into quicksand. What follows is mysterious, almost like a hallucination sequence. When Thomas makes it back home safely, he writes an autobiographical song, “Seascraper” (you can listen to a recording on Wood’s website).

After this one pivotal and surprising day, Thomas’s fortunes might just change. This atmospheric novella contrasts subsistence living with creative fulfillment. There is the bitterness of crushed dreams but also a glimmer of hope. Its The Old Man and the Sea-type setup emphasizes questions of solitude, obsession and masculinity. Thomas wishes he had a father in his life; Edgar, even in so short a time frame, acts as a sort of father figure for him. And Edgar is a father himself – he shows Thomas a photo of his daughter. We are invited to ponder what makes a good father and what the absence of one means at different stages in life. Mental and physical health are also crucial considerations for the characters.

That Wood packs all of this into a compact circadian narrative is impressive. My admiration never crossed into warmth, however. I’ve read four of Wood’s five novels and still love his debut, The Bellwether Revivals, most, followed by his second, The Ecliptic. I’ve also read The Young Accomplice, which I didn’t care for as much, so I’m only missing out on A Station on the Path to Somewhere Better now. Wood’s plot and character work is always at a high standard, but his books are so different from each other that I have no clear sense of him as a novelist. Still, I’m pleased that the Booker longlisting has introduced him to many new readers.

Also reviewed by:

Annabel (AnnaBookBel)

Anne (My Head Is Full of Books)

Brona (This Reading Life)

Cathy (746 Books)

Davida (The Chocolate Lady’s Book Review Blog)

Eric (Lonesome Reader)

Jane (Just Reading a Book)

Helen (She Reads Novels)

Kate (Books Are My Favourite and Best)

Kay (What? Me Read?)

Nancy (The Literate Quilter)

Rachel (Yarra Book Club)

Susan (A life in books)

Check out this written interview with Wood (and this video one with Eric of Lonesome Reader) as well as a Q&A on the Booker Prize website in which Wood talks about the unusual situation in which he wrote the book.

(Public library)

[163 pages]

![]()

Nine Days in Germany and What I Read, Part I: Berlin

We’ve actually been back for more than a week, but soon after our return I was felled by a nasty cold (not Covid, surprisingly), which has left me with a lingering cough and ongoing fatigue. Finally, I’m recovered just about enough to report back.

This Interrail adventure was more low-key than the one we took in 2016. The first day saw us traveling as far as Aachen, just over the border from France. It’s a nice small city with Christian and culinary history: Charlemagne is buried in the cathedral; and it’s famous for a chewy, spicy gingerbread called printen. Before our night in a chain hotel, we stumbled upon the mayor’s Green Party rally in the square – there was to be an election the following day – and drank and dined well. The Gin Library, spotted at random on the map, is an excellent and affordable Asian-fusion cocktail bar. My “Big Ben,” for instance, featured Tanqueray gin, lemon juice, honey, fresh coriander, and cinnamon syrup. Then at Hanswurst – Das Wurstrestaurant (cue jokes about finding the “worst” restaurant in Aachen!), a superior fast-food joint, I had the vegetarian “Hans Berlin,” a scrumptious currywurst with potato wedges.

The next day it was off to Berlin with a big bag of bakery provisions. For the first time, we experienced the rail cancellations and delays that would plague us for much of the next week. We then had to brave the only supermarket open in Berlin on a Sunday – the Rewe in the Hauptbahnhof – before taking the S-Bahn to Alexanderplatz, the nearest station to our Airbnb flat.

It was all worth it to befriend Lemmy (the ginger one) and Roxanne. It’s a sweet deal the host has here: whenever she goes away, people pay her to look after her cats. At the same time as we were paying for a cat-sitter back home. We must be chumps!

I’ll narrate the rest of the trip through the books I read. I relished choosing relevant reads from my shelves and the library’s holdings – I was truly spoiled for choice for Berlin settings! – and I appreciated encountering them all on location.

As soon as we walked into the large airy living room of the fifth-floor Airbnb flat, I nearly laughed out loud, for there in the corner was a monstera plant. The trendy, minimalist décor, too, was just like that of the main characters’ place in…

Perfection by Vincenzo Latronico (2022; 2025)

[Translated from Italian by Sophie Hughes]

Anna and Tom are digital nomads from Southern Europe who offer up their Berlin flat as a short-term rental. In the listing photographs it looks pristine, giving no hint of the difficulties of the expatriate life such as bureaucracy and harsh winters. “Creative professionals” working in the fields of web development and graphic design, they are part of the micro-generation that grew up as the Internet was becoming mainstream, and they tailor their products and personal lives to social media’s preferences. They are lazy liberals addicted to convenience and materialism; aspiring hedonists who like the idea of sex clubs but don’t enjoy them when they actually get there. When Berlin loses its magic, they try Portugal and Sicily before an unforeseen inheritance presents them with the project of opening their own coastal guesthouse. “What they were looking for must have existed once upon a time, back when you only had to hop onto a train or a ferry to reach a whole other world.” This International Booker Prize shortlistee is a smart satire about online posturing and the mistaken belief that life must be better elsewhere. There are virtually no scenes or dialogue but Latronico gets away with the all-telling style because of the novella length. Were it not for his note in the Acknowledgements, I wouldn’t have known that this is a tribute to Things by Georges Perec. (Read via Edelweiss)

Anna and Tom are digital nomads from Southern Europe who offer up their Berlin flat as a short-term rental. In the listing photographs it looks pristine, giving no hint of the difficulties of the expatriate life such as bureaucracy and harsh winters. “Creative professionals” working in the fields of web development and graphic design, they are part of the micro-generation that grew up as the Internet was becoming mainstream, and they tailor their products and personal lives to social media’s preferences. They are lazy liberals addicted to convenience and materialism; aspiring hedonists who like the idea of sex clubs but don’t enjoy them when they actually get there. When Berlin loses its magic, they try Portugal and Sicily before an unforeseen inheritance presents them with the project of opening their own coastal guesthouse. “What they were looking for must have existed once upon a time, back when you only had to hop onto a train or a ferry to reach a whole other world.” This International Booker Prize shortlistee is a smart satire about online posturing and the mistaken belief that life must be better elsewhere. There are virtually no scenes or dialogue but Latronico gets away with the all-telling style because of the novella length. Were it not for his note in the Acknowledgements, I wouldn’t have known that this is a tribute to Things by Georges Perec. (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

We got to pretend to be hip locals for four days, going up the Reichstag tower, strolling through the Tiergarten, touring the Natural History Museum (which has some excellent taxidermy as at left), walking from Potsdam station through Park Sanssouci and ogling the castles and windmill, chowing down on hand-pulled noodles and bao buns at neighbourhood café Wen Cheng, catching an excellent free lunchtime concert at the Philharmonic, and bringing back pastries or vegan doughnuts to snack on while hanging out with the kitties. The S-Bahn was included on our Interrail passes but didn’t go everywhere we needed, so we were often on the handy U-Bahn and tram system instead. Graffiti is an art form rather than an antisocial activity in Berlin; there is so much of it, everywhere.

We got to pretend to be hip locals for four days, going up the Reichstag tower, strolling through the Tiergarten, touring the Natural History Museum (which has some excellent taxidermy as at left), walking from Potsdam station through Park Sanssouci and ogling the castles and windmill, chowing down on hand-pulled noodles and bao buns at neighbourhood café Wen Cheng, catching an excellent free lunchtime concert at the Philharmonic, and bringing back pastries or vegan doughnuts to snack on while hanging out with the kitties. The S-Bahn was included on our Interrail passes but didn’t go everywhere we needed, so we were often on the handy U-Bahn and tram system instead. Graffiti is an art form rather than an antisocial activity in Berlin; there is so much of it, everywhere.

- Reichstag (Photos 1, 2 and 4 by Chris Foster)

- Reichstag tower designed by Norman Foster

- The Philharmonic

- Brandenburg Gate (Photos 1-3 by Chris Foster)

- Postdam’s Park Sanssouci

- Wen Cheng noodles

- Brammibal’s vegan doughnuts

I brought along another novella that proved an apt companion for our explorations of the city. Even just spotting familiar street and stop names in it felt like reassurance.

Sojourn by Amit Chaudhuri (2022)

The narrator of this spare text is a Böll Visiting Professor experiencing disorientation yet resisting gestures of familiarity. Like a Teju Cole or Rachel Cusk protagonist, his personality only seeps in through his wanderings and conversations. After his first talk, he meets a fellow Indian from the audience, Faqrul Haq, who takes it upon himself to be his dedicated tour guide. The narrator isn’t entirely sure how he feels about Faqrul, yet meets him for meals and seeks his advice about the best place to buy warm outerwear. An expat friend is a crutch he wishes he could refuse, but the bewilderment of being somewhere you don’t speak the language at all is such that he feels bound to accept. Meanwhile, there is the possibility of another academic admirer, Birgit, becoming his lover. Strangely, his relationship with his cleaning lady, who addresses him only in German, seems the healthiest one on offer. As the book goes on, the chapters get shorter and shorter, presaging some kind of mental crisis. “I keep walking – in which direction I’m not sure; Kreuzberg? I’ve lost my bearings – not in the city; in its history. The less sure I become of it, the more I know my way.” This was interesting, even admirable, but I wanted more story. (Public library)

The narrator of this spare text is a Böll Visiting Professor experiencing disorientation yet resisting gestures of familiarity. Like a Teju Cole or Rachel Cusk protagonist, his personality only seeps in through his wanderings and conversations. After his first talk, he meets a fellow Indian from the audience, Faqrul Haq, who takes it upon himself to be his dedicated tour guide. The narrator isn’t entirely sure how he feels about Faqrul, yet meets him for meals and seeks his advice about the best place to buy warm outerwear. An expat friend is a crutch he wishes he could refuse, but the bewilderment of being somewhere you don’t speak the language at all is such that he feels bound to accept. Meanwhile, there is the possibility of another academic admirer, Birgit, becoming his lover. Strangely, his relationship with his cleaning lady, who addresses him only in German, seems the healthiest one on offer. As the book goes on, the chapters get shorter and shorter, presaging some kind of mental crisis. “I keep walking – in which direction I’m not sure; Kreuzberg? I’ve lost my bearings – not in the city; in its history. The less sure I become of it, the more I know my way.” This was interesting, even admirable, but I wanted more story. (Public library) ![]()

We spent a drizzly and slightly melancholy first day and final morning making pilgrimages to Jewish graveyards and monuments to atrocities, some of them nearly forgotten. I got the sense of a city that has been forced into a painful reckoning with its past – not once but multiple times, perhaps after decades of repression. One morning we visited the claustrophobic monument to the Murdered Jews of Europe, and, in the Tiergarten, the small memorials to the Roma and homosexual victims of the Holocaust. The Nazis came for political dissidents and the disabled, too, as I was reminded at the Topography of Terrors, a free museum where brutal facts are laid bare. We didn’t find the courage to go in as the timeline outside was confronting enough. I spotted links to the two historical works I was reading during my stay (Stella the red-haired Jew-catcher in the former and Magnus Hirschfeld’s institute in the latter). As I read both, I couldn’t help but think about the current return of fascism worldwide and the gradual erosion of rights that should concern us all.

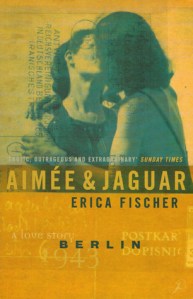

Aimée and Jaguar: A Love Story, Berlin 1943 by Erica Fischer (1994; 1995)

[Translated from German by Edna McCown]

Elisabeth “Lilly” Wust was a good German: the estranged wife of a Nazi and mother of four young sons. She met Felice Schragenheim via her new domestic helper, Inge Wolf. Lilly (aka Aimée) was slow to grasp that Inge and Felice were part of a local lesbian milieu, and didn’t realize Felice (aka Jaguar) was a “U-boat” (Jew living underground) until they’d already become lovers. They got nearly a year and a half together, living almost as a married couple – they had rings engraved and everything – before Felice was taken into Gestapo custody. You know from the outset that this story won’t end well, but you keep hoping – just like Lilly did. It’s not a usual or ‘satisfying’ tragedy, though, because there is no record of what happened to Felice. She was declared legally dead in 1948 but most likely shared the fate of Anne and Margot Frank, dying of typhus at Bergen-Belsen. It’s heartbreaking that Felice, the orphaned daughter of well-off dentists, had multiple chances to flee Berlin – via her sister in London, their stepmother in Palestine, an uncle in America, or friends escaping through Switzerland – but chose to remain.

Elisabeth “Lilly” Wust was a good German: the estranged wife of a Nazi and mother of four young sons. She met Felice Schragenheim via her new domestic helper, Inge Wolf. Lilly (aka Aimée) was slow to grasp that Inge and Felice were part of a local lesbian milieu, and didn’t realize Felice (aka Jaguar) was a “U-boat” (Jew living underground) until they’d already become lovers. They got nearly a year and a half together, living almost as a married couple – they had rings engraved and everything – before Felice was taken into Gestapo custody. You know from the outset that this story won’t end well, but you keep hoping – just like Lilly did. It’s not a usual or ‘satisfying’ tragedy, though, because there is no record of what happened to Felice. She was declared legally dead in 1948 but most likely shared the fate of Anne and Margot Frank, dying of typhus at Bergen-Belsen. It’s heartbreaking that Felice, the orphaned daughter of well-off dentists, had multiple chances to flee Berlin – via her sister in London, their stepmother in Palestine, an uncle in America, or friends escaping through Switzerland – but chose to remain.

The narrative incorporates letters, diaries and interviews, especially with Lilly, who clearly grieved Felice for the rest of her life. The book is unsettling, though, in that Fischer doesn’t let it stand as a simple Juliet & Juliet story; rather, she undermines Lilly by highlighting Felice’s promiscuity (so she likely would not have remained faithful) and Lilly’s strange postwar behaviour: desperately trying to reclaim Felice’s property, and raising her sons as Jewish. This was a time capsule, a wholly absorbing reclamation of queer history, but no romantic vision. (Secondhand purchase – Community Furniture Project)

The narrative incorporates letters, diaries and interviews, especially with Lilly, who clearly grieved Felice for the rest of her life. The book is unsettling, though, in that Fischer doesn’t let it stand as a simple Juliet & Juliet story; rather, she undermines Lilly by highlighting Felice’s promiscuity (so she likely would not have remained faithful) and Lilly’s strange postwar behaviour: desperately trying to reclaim Felice’s property, and raising her sons as Jewish. This was a time capsule, a wholly absorbing reclamation of queer history, but no romantic vision. (Secondhand purchase – Community Furniture Project) ![]()

[A similar recent release: Milena and Margarete: A Love Story in Ravensbrück by Gwen Strauss]

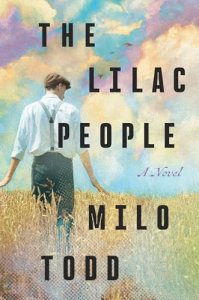

The Lilac People by Milo Todd (2025)

This was illuminating, as well as upsetting, about the persecution of trans people in Nazi Germany. Todd alternates between the gaiety of early 1930s Berlin – when trans man Bertie worked for Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute of Sexual Science and gathered with friends at the Eldorado Club for dancing and singing their anthem, “Das Lila Lied” – and 1945 Ulm, where Bert and his partner Sofie have been posing as an older farming couple. At the novel’s start, a runaway from Dachau, a young trans man named Karl, joins their household. Ironically, it is at this point safer to be Jewish than to be different in any other way; even with the war over, rumour has it the Allies are rounding up queer people and putting them in forced labour camps, so the trio pretend to be Jews as they ponder a second round of escapes.

This was illuminating, as well as upsetting, about the persecution of trans people in Nazi Germany. Todd alternates between the gaiety of early 1930s Berlin – when trans man Bertie worked for Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute of Sexual Science and gathered with friends at the Eldorado Club for dancing and singing their anthem, “Das Lila Lied” – and 1945 Ulm, where Bert and his partner Sofie have been posing as an older farming couple. At the novel’s start, a runaway from Dachau, a young trans man named Karl, joins their household. Ironically, it is at this point safer to be Jewish than to be different in any other way; even with the war over, rumour has it the Allies are rounding up queer people and putting them in forced labour camps, so the trio pretend to be Jews as they ponder a second round of escapes.

While this is slow to start with, and heavy on research throughout, it does gather pace. The American officer, Ward, is something of a two-dimensional villain who keeps popping back up. Still, the climactic scenes are gripping and the dual timeline works well. Todd explores survivor guilt and gives much valuable context. He is careful to employ language in use at that time (transvestites, transsexuals, “inverts,” “third sex”) and persuasively argues that, in any era, how we treat the vulnerable is the measure of our humanity. (Read via Edelweiss)

While this is slow to start with, and heavy on research throughout, it does gather pace. The American officer, Ward, is something of a two-dimensional villain who keeps popping back up. Still, the climactic scenes are gripping and the dual timeline works well. Todd explores survivor guilt and gives much valuable context. He is careful to employ language in use at that time (transvestites, transsexuals, “inverts,” “third sex”) and persuasively argues that, in any era, how we treat the vulnerable is the measure of our humanity. (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

[A similar recent release: Under the Pink Triangle by Katie Moore (set in Dachau)]

We might have been at the Eldorado in the early 1930s on the evening when we ventured out to the bar Zosch for a “New Orleans jazz” evening. The music was superb, the German wine tasty, the whole experience unforgettable … but it sure did feel like being in a bygone era. We’re so used to the indoor smoking ban (in force in the UK since 2007) that we didn’t expect to find young people chain-smoking rollies in an enclosed brick basement, and got back to the flat with our clothes reeking and our lungs burning.

It was good to see visible signs of LGTBQ support in Berlin, though they weren’t as prevalent as I perhaps expected.

For a taste of more recent German history, I’ve started Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck, which is set in the 1980s not long before the Berlin Wall came down. Unfortunately, my library hold didn’t arrive until too late to take it with me. We made a point of seeing the wall remnants and Checkpoint Charlie on our trip.

For a taste of more recent German history, I’ve started Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck, which is set in the 1980s not long before the Berlin Wall came down. Unfortunately, my library hold didn’t arrive until too late to take it with me. We made a point of seeing the wall remnants and Checkpoint Charlie on our trip.

Other Berlin highlights: a delicious vegetarian lunch at the canteen of an architecture firm, the Ritter chocolate shop, and the pigeons nesting on the flat balcony – the chicks hatched on our final morning!

And a belated contribution to Short Story September:

Touchy Subjects by Emma Donoghue (2006)

I seem to pluck one or two books at random from Donoghue’s back catalogue per year. I designated this as reliable train reading. The 19 contemporary stories fall into thematic bundles: six about pregnancy or babies, several about domestic life, a few each on “Strangers” and “Desire,” and a final set of four touching on death. The settings range around Europe and North America. It’s impressive how Donoghue imagines herself into so many varied situations, including heterosexual men longing for children in their lives and rival Louisiana crawfishermen setting up as tour-boat operators. The attempts to write Black characters in “Lavender’s Blue” and “The Welcome” are a little cringey, and the latter felt dated with its ‘twist’ of a character being trans. She’s on safer ground writing about a jaded creative writing tutor or football teammates who fall for each other. I liked a meaningful encounter between a tourist and an intellectually disabled man in a French cave (“The Sanctuary of Hands”), an Irishwoman’s search for her missing brother in Los Angeles (“Baggage”) and a contemporary take on the Lazarus myth (“Necessary Noise”), but my two favourites were “The Cost of Things,” about a lesbian couple whose breakup is presaged by their responses to their cat’s astronomical vet bill; and “The Dormition of the Virgin,” in which a studious young traveller to Florence misses what’s right under his nose. There are some gems here, but the topics are so scattershot the collection doesn’t cohere. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com)

I seem to pluck one or two books at random from Donoghue’s back catalogue per year. I designated this as reliable train reading. The 19 contemporary stories fall into thematic bundles: six about pregnancy or babies, several about domestic life, a few each on “Strangers” and “Desire,” and a final set of four touching on death. The settings range around Europe and North America. It’s impressive how Donoghue imagines herself into so many varied situations, including heterosexual men longing for children in their lives and rival Louisiana crawfishermen setting up as tour-boat operators. The attempts to write Black characters in “Lavender’s Blue” and “The Welcome” are a little cringey, and the latter felt dated with its ‘twist’ of a character being trans. She’s on safer ground writing about a jaded creative writing tutor or football teammates who fall for each other. I liked a meaningful encounter between a tourist and an intellectually disabled man in a French cave (“The Sanctuary of Hands”), an Irishwoman’s search for her missing brother in Los Angeles (“Baggage”) and a contemporary take on the Lazarus myth (“Necessary Noise”), but my two favourites were “The Cost of Things,” about a lesbian couple whose breakup is presaged by their responses to their cat’s astronomical vet bill; and “The Dormition of the Virgin,” in which a studious young traveller to Florence misses what’s right under his nose. There are some gems here, but the topics are so scattershot the collection doesn’t cohere. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

Trip write-up to be continued (tomorrow, with any luck)…

Summer Reading 2025: Anthony, Espach, Han & Teir

In the UK, summer doesn’t officially end until the 22nd, so even though I’ve been doing plenty of baking with apples and plums and we’ve had squashes delivered in our vegetable box, I’ve taken advantage of that extra time to finish a couple more summery books. This year I’m featuring four novels ranging in location from Rhode Island to Finland. I’ve got all the trappings of summer: a swimming pool, a wedding, a beach retreat, and a summer house.

The Most by Jessica Anthony (2024)

I can’t resist a circadian narrative. This novella takes place in Delaware on one day in early November 1957, but flashbacks and close third-person narration reveal everything we need to know about Virgil and Kathleen Beckett and their marriage. I’m including it in my summer reading because it’s set on an unseasonably warm Sunday and Kathleen decides to spend the entire day in their apartment complex’s pool. The mother of two drifts back in memory to her college tennis-playing days and her first great love, Billy Blasko, a Czech tennis coach who created a signature move called “The Most,” which means “bridge” in his language – the idea is to trap your opponent and then drop a bomb on them. Virgil, who after taking their two boys to church goes golfing with his insurance sales colleagues as is expected of him, loves jazz music and has just been sent the secret gift of a saxophone. Both spouses are harbouring secrets and, as Laika orbits the Earth overhead, they wonder if they can break free from the capsules they’ve built around their hearts and salvage their relationship. The storytelling is tight even as the book loops around the same events from the two perspectives. This was really well done, and a big step up from Enter the Aardvark. (Public library)

I can’t resist a circadian narrative. This novella takes place in Delaware on one day in early November 1957, but flashbacks and close third-person narration reveal everything we need to know about Virgil and Kathleen Beckett and their marriage. I’m including it in my summer reading because it’s set on an unseasonably warm Sunday and Kathleen decides to spend the entire day in their apartment complex’s pool. The mother of two drifts back in memory to her college tennis-playing days and her first great love, Billy Blasko, a Czech tennis coach who created a signature move called “The Most,” which means “bridge” in his language – the idea is to trap your opponent and then drop a bomb on them. Virgil, who after taking their two boys to church goes golfing with his insurance sales colleagues as is expected of him, loves jazz music and has just been sent the secret gift of a saxophone. Both spouses are harbouring secrets and, as Laika orbits the Earth overhead, they wonder if they can break free from the capsules they’ve built around their hearts and salvage their relationship. The storytelling is tight even as the book loops around the same events from the two perspectives. This was really well done, and a big step up from Enter the Aardvark. (Public library) ![]()

The Wedding People by Alison Espach (2024)

You’ve all heard about this one, right? It’s been a Read with Jenna selection and the holds are stacking up in my library system. No wonder it’s been hailed as a perfect summer read: it’s full of sparkling banter; heartwarming, very funny and quite sexy. And that despite a grim opening situation: Phoebe flies from St. Louis to Newport and checks into a luxury hotel, intending to kill herself. She’s an adjunct professor whose husband left her for their colleague after their IVF attempts failed, and she feels she’ll never finish writing her book, become a mother or find true love again. Little does she know that a Bridezilla type named Lila who’s spent $1 million of her inheritance on a week-long wedding extravaganza (culminating in a ceremony at The Breakers mansion) meant to book out the entire hotel. Phoebe somehow snagged the room with the best view. Lila isn’t about to let anyone ruin her wedding.

You’ve all heard about this one, right? It’s been a Read with Jenna selection and the holds are stacking up in my library system. No wonder it’s been hailed as a perfect summer read: it’s full of sparkling banter; heartwarming, very funny and quite sexy. And that despite a grim opening situation: Phoebe flies from St. Louis to Newport and checks into a luxury hotel, intending to kill herself. She’s an adjunct professor whose husband left her for their colleague after their IVF attempts failed, and she feels she’ll never finish writing her book, become a mother or find true love again. Little does she know that a Bridezilla type named Lila who’s spent $1 million of her inheritance on a week-long wedding extravaganza (culminating in a ceremony at The Breakers mansion) meant to book out the entire hotel. Phoebe somehow snagged the room with the best view. Lila isn’t about to let anyone ruin her wedding.

What follows is Cinderella-like yet takes into account the realities of bereavement, infidelity, infertility and blended families. Because of the one-week format, Phoebe’s depression is defused more quickly than is plausible, but I was relieved that Espach doesn’t plump for a full-blown happy ending. I did also find the novel unnecessarily crass in places, especially the gag about the car. Still, this has all the wit of Katherine Heiny and Curtis Sittenfeld. I’d recommend it if you enjoyed Dream State or Consider Yourself Kissed, and it’s especially reminiscent of Sorrow and Bliss for the mixture of humour and frank consideration of mental health. It’s as easy to relate to Phoebe’s feelings (“How much of her life had she spent in this moment, waiting for someone else to decide something conclusive about her?”; “It is so much easier to sit in things and wait for someone to save us”) as it is to laugh at the one-liners. “Garys are not wonderful. That’s just not what they are meant to be” particularly tickled me because I know a few Garys in real life. (Public library) ![]()

The Summer I Turned Pretty by Jenny Han (2008)

Every summer Belly and her mother and brother have joined her mother’s best friend Susannah and her sons Conrad and Jeremiah at their beach house. She’s had a crush on Conrad for what’s felt like forever, but she’s only ever been his surrogate little sister, fun for palling around with but never taken seriously. This summer is different, though: Belly is turning 16, it’s Conrad’s last summer before college, and his family seems to be falling apart. The novel kept being requested off me and I puzzled over how it could have eight reservations on it until I realized there’s an Amazon Prime Video adaptation now in its third and final season. I reckon the story will work better on screen because Belly’s narration was the main issue for me. She’s ever so shallow, so caught up in boys that she doesn’t realize Susannah is sick again. Her fixation on the brooding Conrad doesn’t make sense when she could have affable Jeremiah or sweet, geeky Cam, who met her through Latin club and liked her before she grew big boobs. He’s who she’s supposed to be with in this kind of story, right? I think this would appeal to younger, boy-crazy teens, but it just made me feel old and grumpy. (Public library)

Every summer Belly and her mother and brother have joined her mother’s best friend Susannah and her sons Conrad and Jeremiah at their beach house. She’s had a crush on Conrad for what’s felt like forever, but she’s only ever been his surrogate little sister, fun for palling around with but never taken seriously. This summer is different, though: Belly is turning 16, it’s Conrad’s last summer before college, and his family seems to be falling apart. The novel kept being requested off me and I puzzled over how it could have eight reservations on it until I realized there’s an Amazon Prime Video adaptation now in its third and final season. I reckon the story will work better on screen because Belly’s narration was the main issue for me. She’s ever so shallow, so caught up in boys that she doesn’t realize Susannah is sick again. Her fixation on the brooding Conrad doesn’t make sense when she could have affable Jeremiah or sweet, geeky Cam, who met her through Latin club and liked her before she grew big boobs. He’s who she’s supposed to be with in this kind of story, right? I think this would appeal to younger, boy-crazy teens, but it just made me feel old and grumpy. (Public library) ![]()

The Summer House by Philip Teir (2017; 2018)

[Translated from Swedish by Tiina Nunnally]

The characters are Finland-Swedish, like the author. Erik and Julia escape Helsinki with their children, Alice and Anton, to spend time at her father’s summer house. Erik has just lost his job in IT for a large department store, but hasn’t told Julia yet. Julia is working on a novel, but distracted by the fact that her childhood friend Marika, the not so secret inspiration for a character in her previous novel, is at another vacation home nearby with Chris, her Scottish partner. These two and their hangers-on have a sort of commune based around free love and extreme environmental realism: the climate crisis will not be solved (“accepting the grief instead of talking about hope all the time”) and the only thing to do is participate in de-civilisation. But like many a cult leader, Chris courts young female attention and isn’t the best role model. Both couples are strained to breaking point.

The characters are Finland-Swedish, like the author. Erik and Julia escape Helsinki with their children, Alice and Anton, to spend time at her father’s summer house. Erik has just lost his job in IT for a large department store, but hasn’t told Julia yet. Julia is working on a novel, but distracted by the fact that her childhood friend Marika, the not so secret inspiration for a character in her previous novel, is at another vacation home nearby with Chris, her Scottish partner. These two and their hangers-on have a sort of commune based around free love and extreme environmental realism: the climate crisis will not be solved (“accepting the grief instead of talking about hope all the time”) and the only thing to do is participate in de-civilisation. But like many a cult leader, Chris courts young female attention and isn’t the best role model. Both couples are strained to breaking point.

Meanwhile, Chris and Marika’s son, Leo, has been sneaking off with Alice; and Erik’s brother Anders shows up and starts seeing the widowed therapist neighbour. This was a reasonably likeable book about how we respond to crises personal and global, and how we react to our friends’ successes and problems – Erik is jealous of his college buddy’s superior performance in a tech company. But I thought it was a little aimless, especially in its subplots, and it suffered in comparison with Leave the World Behind, which has quite a similar setup but a more intriguing cosmic/dystopian direction. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

Any final summer books for you this year?

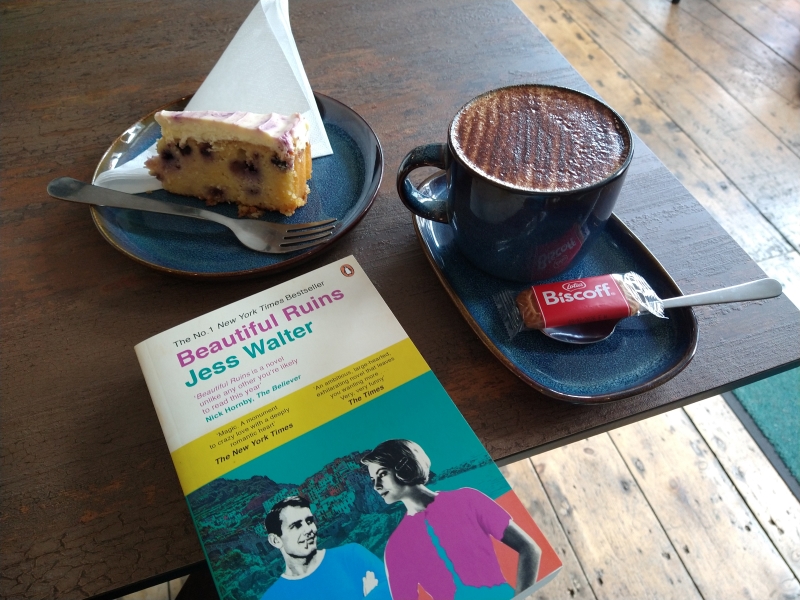

Three on a Theme: Armchair Travels at the Italian Coast (Rachel Joyce, Sarah Moss and Jess Walter – #18 of 20 Books)

I’ve done a lot of journeying through Italy’s lakes and islands this summer. Not in real life, thank goodness – it would be far too hot! – but via books. I started with the Moss, then read the Joyce, and rounded off with the Walter, a book that had been on my TBR for 12 years and that many had heartily recommended, so I was delighted to finally experience it for myself.

The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce (2025)

Joyce has really upped her game. I’ve somehow read all of her books though I often found them, from Harold Fry onward, disappointingly sentimental and twee. But with this she’s entering the big leagues, moving into the more expansive, elegant and empathetic territory of novels by Anne Enright (The Green Road), Patrick Gale (Notes from an Exhibition), Maggie O’Farrell (Instructions for a Heatwave) and Tom Rachman (The Italian Teacher). It’s the story of four siblings, initially drawn together and then dramatically blown apart by their father’s death. Despite weighty themes of alcoholism, depression and marital struggles, there is an overall lightness of tone and style that made this a pleasure to read.

Vic Kemp, the title figure, was a larger-than-life, womanizing painter whose work divided critics. After his first wife’s early death from cancer, he raised three daughters and a son with the help of a rotating cast of nannies (whom he inevitably slept with). At 76 he delivered the shocking news that he was marrying again: Bella-Mae, an artist in her twenties – much younger than any of his children. They moved from London to his second home in Italy just weeks before he drowned in Lake Orta. Netta, the eldest daughter, is sure there’s something fishy; he knew the lake so well and would never have gone out for a swim with a mist rolling in. Did Bella-Mae kill him for his money? And where is his last painting? Funny how waiting for an autopsy report and searching for a new will and carping with siblings over the division of belongings can ruin what should be paradise.

The interactions between Netta, Susan, Goose (Gustav) and Iris, plus Bella-Mae and her cousin Laszlo, are all flawlessly done, and through flashbacks and surges forward we learn so much about these flawed and flailing characters. The derelict villa and surrounding small town are appealing settings, and there are a lot of intriguing references to food, fashion and modern art.

My only small points of criticism are that Iris is less fleshed out than the others (and her bombshell secret felt distasteful), and that Joyce occasionally resorts to delivering some of her old obvious (though true) messages through an omniscient narrator, whereas they could be more palatable if they came out organically in dialogue or indirectly through a character’s thought process. Here’s an example: “When someone dies or disappears, we can only tell stories about what might have been the case or what might have happened next.” (One I liked better: “There were some things you never got over. No amount of thinking or talking would make them right: the best you could do was find a way to live alongside them.”) I also don’t think Goose would have been able to view his father’s body more than two months after his death; even with embalming, it would have started to decay within weeks.

You can tell that Joyce got her start in theatre because she’s so good at scenes and dialogue, and at moving people into different groups to see what they’ll do. She’s taken the best of her work in other media and brought it to bear here. It’s fascinating how Goose starts off seeming minor and eventually becomes the main POV character. And ending with a wedding (good enough for a Shakespearean comedy) offers a lovely occasion for a potential reconciliation after a (tragi)comic plot. More of this calibre, please! (Public library) ![]()

Ripeness by Sarah Moss (2025)

One sneaky little line, “Ripeness, not readiness, is all,” a Shakespeare mash-up (“Ripeness is all” is from King Lear vs. “the readiness is all” is from Hamlet), gives a clue to how to understand this novel: As a work of maturity from Sarah Moss, presenting life with all its contradictions and disappointments, not attempting to counterbalance that realism with any false optimism. What do we do, who will we be, when faced with situations for which we aren’t prepared?

Now that she’s based in Ireland, Moss seems almost to be channelling Irish authors such as Claire Keegan and Maggie O’Farrell. The line-up of themes – ballet + sisters + ambivalent motherhood + the question of immigration and belonging – should have added up to something incredible and right up my street. While Ripeness is good, even very good, it feels slightly forced. As has been true with some of Moss’s recent fiction (especially Summerwater), there is the air of a creative writing experiment. Here the trial is to determine which feels closer, a first-person rendering of a time nearly 60 years ago, or a present-tense, close-third-person account of the now. [I had in mind advice from one of Emma Darwin’s Substack posts: “What you’ll see is that ‘deep third’ is really much the same as first, in the logic of it, just with different pronouns: you are locking the narrative into a certain character’s point-of-view, but you don’t have a sense of that character as the narrator, the way you do in first person.” Except, increasingly as the novel goes on, we are compelled to think about Edith as a narrator, of her own life and others’.

In the current story line, everyone in rural West Ireland seems to have come from somewhere else (e.g. Edith’s lover Gunter is German). “She’s going to have to find a way to rise above it, this tribalism,” Edith thinks. She’s aghast at her town playing host to a small protest against immigration. Fair enough, but including this incident just seems like an excuse for some liberal handwringing (“since it’s obvious that there is enough for all, that the problem is distribution not supply, why cannot all have enough? Partly because people like Edith have too much.”). The facts of Maman being French-Israeli and having lost family in the Holocaust felt particularly shoehorned in; referencing Jewishness adds nothing. I also wondered why she set the 1960s narrative in Italy, apart from novelty and personal familiarity. (Teenage Edith’s high school Italian is improbably advanced, allowing her to translate throughout her sister’s childbirth.)

Though much of what I’ve written seems negative, I was left with an overall favourable impression. Mostly it’s that the delivery scene and the chapters that follow it are so very moving. Plus there are astute lines everywhere you look, whether on dance, motherhood, or migration. It may simply be that Moss was taking on too much at once, such that this lacks the focus of her novellas. Ultimately, I would have been happy to have just the historical story line; the repeat of the surrendering for adoption element isn’t necessary to make any point. (I was relieved, anyway, that Moss didn’t resort to the cheap trick of having the baby turn out to be a character we’ve already been introduced to.) I admire the ambition but feel Moss has yet to return to the sweet spot of her first five novels. Still, I’m a fan for life. (Public library) ![]()

#18 of my 20 Books of Summer

(Completing the second row on the Bingo card: Book set in a vacation destination)

Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter (2012)

I loved how Emma Straub described the ideal summer read in one of her Substack posts: “My plan for the summer is to read as many books as possible that make me feel that drugged-up feeling, where you just want to get back to the page.” I wish I’d been able to read this faster – that I hadn’t had so much on my plate all summer so I could have been fully immersed. Nonetheless, every time I returned to it I felt welcomed in. So many trusted bibliophiles love this book – blogger friends Laila and Laura T.; Emma Milne-White, owner of Hungerford Bookshop, who plugged it at their 2023 summer reading celebration; and Maris Kreizman, who in a recent newsletter described this as “One of my favorite summer reading novels ever … escapist magic, a lush historical novel.”

I loved how Emma Straub described the ideal summer read in one of her Substack posts: “My plan for the summer is to read as many books as possible that make me feel that drugged-up feeling, where you just want to get back to the page.” I wish I’d been able to read this faster – that I hadn’t had so much on my plate all summer so I could have been fully immersed. Nonetheless, every time I returned to it I felt welcomed in. So many trusted bibliophiles love this book – blogger friends Laila and Laura T.; Emma Milne-White, owner of Hungerford Bookshop, who plugged it at their 2023 summer reading celebration; and Maris Kreizman, who in a recent newsletter described this as “One of my favorite summer reading novels ever … escapist magic, a lush historical novel.”

I’m relieved to report that Beautiful Ruins lived up to everyone’s acclaim – and my own high expectations after enjoying Walter’s So Far Gone, which I reviewed for BookBrowse earlier in the summer. I was immediately captivated by the shabby glamour of Pasquale’s hotel in Porto Vergogna on the coast of northern Italy. With refreshing honesty, he’s dubbed the place “Hotel Adequate View.” In April 1962, he’s attempting to build a cliff-edge tennis court when a boat delivers beautiful, dying American actress Dee Moray. It soon becomes clear that her condition is nothing nine months won’t fix and she’s been dumped here to keep her from meddling in the romance between the leads in Cleopatra, filming in Rome. In the present day, an elderly Pasquale goes to Hollywood to find out whatever happened to Dee.

A myriad of threads and formats – a movie pitch, a would-be Hemingway’s first chapter of a never-finished wartime masterpiece, an excerpt from a producer’s autobiography and a play transcript – coalesce to flesh out what happened in that summer of 1962 and how the last half-century has treated all the supporting players. True to the tone of a novel about regret, failure and shattered illusions, Walter doesn’t tie everything up neatly, but he does offer a number of the characters a chance at redemption. This felt to me like a warmer and more timeless version of A Visit from the Goon Squad. There are so many great scenes, none better than Richard Burton’s drunken visit to Porto Vergogna, which had me in stitches. Fantastic. (Hungerford Bookshop – 40th birthday gift from my husband from my wish list) ![]()

#WITMonth, II: Bélem, Blažević, Enríquez, Lebda, Pacheco and Yu (#17 of 20 Books)

Catching up with my Women in Translation month coverage, which concluded (after Part I, here) with five more short novels ranging from historical realism to animal-oriented allegory, plus a travel book.

The Rarest Fruit, or The Life of Edmond Albius by Gaëlle Bélem (2023; 2025)

[Translated from French by Hildegarde Serle]

A fictionalized biography, from infancy to deathbed, of the Black botanist who introduced the world to vanilla – then a rare and expensive flavour – by discovering that the plant can be hand-pollinated in the same way as pumpkins. In 1829, the island colony of Bourbon (now the French overseas department Réunion) has just been devastated by a cyclone when widowed landowner Ferréol Bellier-Beaumont is brought the seven-week-old orphaned son of one of his sister’s enslaved women. Ferréol, who once hunted rare orchids, raises the boy as his ward. From the start, Edmond is most at home in the garden and swears he will follow in his guardian’s footsteps as a botanist. Bélem also traces Ferréol’s history and the origins of vanilla in Mexico. The inclusion of Creole phrases and the various uses of plants, including for traditional healing, chimed with Jason Allen-Paisant’s Jamaica-set The Possibility of Tenderness, and I was reminded somewhat of the historical picaresque style of Slave Old Man (Patrick Chamoiseau) and The Secret Diaries of Charles Ignatius Sancho (Paterson Joseph). The writing is solid but the subject matter so niche that this was a skim for me.

A fictionalized biography, from infancy to deathbed, of the Black botanist who introduced the world to vanilla – then a rare and expensive flavour – by discovering that the plant can be hand-pollinated in the same way as pumpkins. In 1829, the island colony of Bourbon (now the French overseas department Réunion) has just been devastated by a cyclone when widowed landowner Ferréol Bellier-Beaumont is brought the seven-week-old orphaned son of one of his sister’s enslaved women. Ferréol, who once hunted rare orchids, raises the boy as his ward. From the start, Edmond is most at home in the garden and swears he will follow in his guardian’s footsteps as a botanist. Bélem also traces Ferréol’s history and the origins of vanilla in Mexico. The inclusion of Creole phrases and the various uses of plants, including for traditional healing, chimed with Jason Allen-Paisant’s Jamaica-set The Possibility of Tenderness, and I was reminded somewhat of the historical picaresque style of Slave Old Man (Patrick Chamoiseau) and The Secret Diaries of Charles Ignatius Sancho (Paterson Joseph). The writing is solid but the subject matter so niche that this was a skim for me.

With thanks to Europa Editions, who sent an advanced e-copy for review.

In Late Summer by Magdalena Blažević (2022; 2025)

[Translated from Croatian by Anđelka Raguž]

“My name is Ivana. I lived for fourteen summers, and this is the story of my last.” Blažević’s debut novella presents the before and after of one extended family, and of the Bosnian countryside, in August 1993. In the first half, few-page vignettes convey the seasonality of rural life as Ivana and her friend Dunja run wild. Mother and Grandmother slaughter chickens, wash curtains, and treat the children for lice. Foodstuffs and odours capture memory in that famous Proustian way. I marked out the piece “Camomile Flowers” for its details of the senses: “Sunlight and the scent of soap mingle. … The pantry smells like it did before, of caramel, lemon rind and vanilla sugar. Like the period leading up to Christmas. … My hair dries quickly in the sun. It rustles like the lace, dry snow from the fields.” The peaceful beauty of it all is shattered by the soldiers’ arrival. Ivana issues warnings (“Get ready! We’re running out of time. The silence and summer lethargy will not last long”) and continues narrating after her death. As in Sara Nović’s Girl at War, the child perspective contrasts innocence and enthusiasm with the horror of war. I found the first part lovely but the whole somewhat aimless because of the bitty structure.

“My name is Ivana. I lived for fourteen summers, and this is the story of my last.” Blažević’s debut novella presents the before and after of one extended family, and of the Bosnian countryside, in August 1993. In the first half, few-page vignettes convey the seasonality of rural life as Ivana and her friend Dunja run wild. Mother and Grandmother slaughter chickens, wash curtains, and treat the children for lice. Foodstuffs and odours capture memory in that famous Proustian way. I marked out the piece “Camomile Flowers” for its details of the senses: “Sunlight and the scent of soap mingle. … The pantry smells like it did before, of caramel, lemon rind and vanilla sugar. Like the period leading up to Christmas. … My hair dries quickly in the sun. It rustles like the lace, dry snow from the fields.” The peaceful beauty of it all is shattered by the soldiers’ arrival. Ivana issues warnings (“Get ready! We’re running out of time. The silence and summer lethargy will not last long”) and continues narrating after her death. As in Sara Nović’s Girl at War, the child perspective contrasts innocence and enthusiasm with the horror of war. I found the first part lovely but the whole somewhat aimless because of the bitty structure.

With thanks to Linden Editions for the free copy for review.

Somebody Is Walking on Your Grave: My Cemetery Journeys by Mariana Enríquez (2013; 2025)

[Translated from Spanish by Megan McDowell]

This made it onto my Most Anticipated list for the second half of the year due to my love of graveyards. Because of where Enríquez is from, a lot of the cemeteries she features are in Argentina (six) or other Spanish-speaking countries (another six including Chile, Cuba, Mexico, Peru and Spain). There are 10 more locations besides, and her journeys go back as far as 1997 in Genoa, when she was 25 and had sex with Enzo up against a gravestone. I took the most interest in those I have been to (Edinburgh) or could imagine myself travelling to someday (New Orleans and Savannah; Highgate in London and Montparnasse in Paris), but thought that every chapter got bogged down in research. Enríquez writes horror, so she is keen to visit at night and relay any ghost stories she’s heard. But the pages after pages of history were dull and outweighed the memoir and travel elements for me, so after a few chapters I ended up just skimming. I’ll keep this on my Kindle in case I go to one of her other destinations in the future and can read individual essays on location. (Edelweiss download)

This made it onto my Most Anticipated list for the second half of the year due to my love of graveyards. Because of where Enríquez is from, a lot of the cemeteries she features are in Argentina (six) or other Spanish-speaking countries (another six including Chile, Cuba, Mexico, Peru and Spain). There are 10 more locations besides, and her journeys go back as far as 1997 in Genoa, when she was 25 and had sex with Enzo up against a gravestone. I took the most interest in those I have been to (Edinburgh) or could imagine myself travelling to someday (New Orleans and Savannah; Highgate in London and Montparnasse in Paris), but thought that every chapter got bogged down in research. Enríquez writes horror, so she is keen to visit at night and relay any ghost stories she’s heard. But the pages after pages of history were dull and outweighed the memoir and travel elements for me, so after a few chapters I ended up just skimming. I’ll keep this on my Kindle in case I go to one of her other destinations in the future and can read individual essays on location. (Edelweiss download)

Voracious by Małgorzata Lebda (2016; 2025)

[Translated from Polish by Antonia Lloyd-Jones]

Like the Blažević, this is an impressionistic, pastoral work that contrasts vitality and decay in short chapters of one to three pages. The narrator is a young woman staying in her grandmother’s house and caring for her while she is dying of cancer; “now is not the time for life. Death – that’s what fills my head. I’m at its service. Grandma is my child. I am my grandmother’s mother. And that’s all right, I think.” The house has just four inhabitants – the narrator, Grandma Róża, Grandpa, and Ann – and seems permeable: to the cold, to nature. Animals play a large role, whether pets, farmed or wild. There’s Danube the hound, the cows delivered to the nearby slaughterhouse, and a local vixen with whom the narrator identifies.

Lebda is primarily known as a poet, and her delight in language is evident. One piece titled “Opioid,” little more than a paragraph long, revels in the power of language: “Grandma brings a beautiful word home … the word not only resonates, but does something else too – it lets light into the veins.” The wind is described as “the conscience of the forest. It’s the circulatory system. It’s the litany. It’s scented. It sings.”

Lebda is primarily known as a poet, and her delight in language is evident. One piece titled “Opioid,” little more than a paragraph long, revels in the power of language: “Grandma brings a beautiful word home … the word not only resonates, but does something else too – it lets light into the veins.” The wind is described as “the conscience of the forest. It’s the circulatory system. It’s the litany. It’s scented. It sings.”

In all three Linden Editions books I’ve read, the translator’s afterword has been particularly illuminating. I thought I was missing something, but Lloyd-Jones reassured me it’s unclear who Ann is: sister? friend? lover? (I was sure I spotted some homoerotic moments.) Lloyd-Jones believes she’s the mirror image of the narrator, leaning toward life while the narrator – who has endured sexual molestation and thyroid problems – tends towards death. The animal imagery reinforces that dichotomy.

The narrator and Ann remark that it feels like Grandma has been ill for a million years, but they also never want this time to end. The novel creates that luminous, eternal present. It was the best of this bunch.

With thanks to Linden Editions for the free copy for review.

Full review forthcoming for Foreword Reviews:

Pandora by Ana Paula Pacheco (2023; 2025)

[Translated from Portuguese by Julia Sanches]

The Brazilian author’s bold novella is a startling allegory about pandemic-era hazards to women’s physical and mental health. Since the death of her partner Alice to Covid-19, Ana has been ‘married’ to a pangolin and a seven-foot-tall bat. At a psychiatrist’s behest, she revisits her childhood and interrogates the meanings of her relationships. The form varies to include numbered sections, the syllabus for Ana’s course “Is Literature a personal investment?”, journal entries, and extended fantasies. Depictions of animals enable commentary on economic inequalities and gendered struggles. Playful, visceral, intriguing.

The Brazilian author’s bold novella is a startling allegory about pandemic-era hazards to women’s physical and mental health. Since the death of her partner Alice to Covid-19, Ana has been ‘married’ to a pangolin and a seven-foot-tall bat. At a psychiatrist’s behest, she revisits her childhood and interrogates the meanings of her relationships. The form varies to include numbered sections, the syllabus for Ana’s course “Is Literature a personal investment?”, journal entries, and extended fantasies. Depictions of animals enable commentary on economic inequalities and gendered struggles. Playful, visceral, intriguing.

#17 of my 20 Books of Summer:

Invisible Kitties by Yu Yoyo (2021; 2024)

[Translated from Chinese by Jeremy Tiang]

Yu is the author of four poetry collections; her debut novel blends autofiction and magic realism with its story of a couple adjusting to the ways of a mysterious cat. They have a two-bedroom flat on a high-up floor of a complex, and Cat somehow fills the entire space yet disappears whenever the woman goes looking for him. Yu’s strategy in most of these 60 mini-chapters is to take behaviours that will be familiar to any cat owner and either turn them literal through faux-scientific descriptions, or extend them into the fantasy realm. So a cat can turn into a liquid or gaseous state, a purring cat is boiling an internal kettle, and a cat planted in a flowerbed will produce more cats. Some of the stories are whimsical and sweet, like those imagining Cat playing extreme sports, opening a massage parlour, and being the god of the household. Others are downright gross and silly: Cat’s removed testicles become “Cat-Ball Planets” and the narrator throws up a hairball that becomes Kitten. Mixed feelings, then. (Passed on by Annabel – thank you!)

Yu is the author of four poetry collections; her debut novel blends autofiction and magic realism with its story of a couple adjusting to the ways of a mysterious cat. They have a two-bedroom flat on a high-up floor of a complex, and Cat somehow fills the entire space yet disappears whenever the woman goes looking for him. Yu’s strategy in most of these 60 mini-chapters is to take behaviours that will be familiar to any cat owner and either turn them literal through faux-scientific descriptions, or extend them into the fantasy realm. So a cat can turn into a liquid or gaseous state, a purring cat is boiling an internal kettle, and a cat planted in a flowerbed will produce more cats. Some of the stories are whimsical and sweet, like those imagining Cat playing extreme sports, opening a massage parlour, and being the god of the household. Others are downright gross and silly: Cat’s removed testicles become “Cat-Ball Planets” and the narrator throws up a hairball that becomes Kitten. Mixed feelings, then. (Passed on by Annabel – thank you!)

I’m really pleased with myself for covering a total of 8 books for this challenge, each one translated from a different language!

Which of these would you read?

20 Books of Summer, 11–12 (Victoriana): Edward Carey & George Grossmith

Neither of these appeared on my initial list, but I thought a middle-grade novel and a classic would be good for variety. Though I have an MA in Victorian Literature, I don’t often read from the period anymore because I’m allergic to wordy triple-deckers, so it was a delight to encounter something short and lighthearted. I’ve always been partial to a contemporary Victorian pastiche, though.

Heap House (Iremonger, #1) by Edward Carey (2013)

The Iremonger family wealth came from salvaging treasure from the rubbish heaps surrounding their London mansion. Every Iremonger has a birth object (like a daemon?) associated with them. Clodius Iremonger, adolescent descendant of the great family, has a special skill: he hears each birth object speaking its name. His own bath plug, for instance, cries out, “James Henry Hayward.” These objects house enchanted souls; people can change back into objects and vice versa. The narration alternates between Clod and plucky Lucy Pennant, who arrives from a local orphanage to work as a house servant. All staff and heap-workers are called “Iremonger,” but Lucy refuses to cede her identity and wants justice for the oppressed workers. She and Clod form a bond against the odds and there’s an upstairs–downstairs tinge to their ensuing adventures in the house and on the heaps.

The Iremonger family wealth came from salvaging treasure from the rubbish heaps surrounding their London mansion. Every Iremonger has a birth object (like a daemon?) associated with them. Clodius Iremonger, adolescent descendant of the great family, has a special skill: he hears each birth object speaking its name. His own bath plug, for instance, cries out, “James Henry Hayward.” These objects house enchanted souls; people can change back into objects and vice versa. The narration alternates between Clod and plucky Lucy Pennant, who arrives from a local orphanage to work as a house servant. All staff and heap-workers are called “Iremonger,” but Lucy refuses to cede her identity and wants justice for the oppressed workers. She and Clod form a bond against the odds and there’s an upstairs–downstairs tinge to their ensuing adventures in the house and on the heaps.

Carey’s trademark twisted combination of Dickensian charm and Gothic gloom is certainly on display here. All the other names are slightly off-kilter: Rosamud, Moorcus, Aliver, Pinalippy and so on. I laughed out loud at a passage about the dubious purpose of doilies. Little truly won me over, but all my experiences with Carey’s work since then (also including The Swallowed Man, B: A Year in Plagues and Pencils, and Edith Holler) have been a slight letdown. This was highly readable and I galloped through the midsection, but I found the whole thing overlong; I’m undecided about reading the other books, though they do have higher average ratings on Goodreads. I got the second, Foulsham, from the Little Free Library and it’s significantly shorter. Shall I continue? (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

The Diary of a Nobody by George Grossmith; illus. Weedon Grossmith (1892)

It must be rare for a fictional character to be memorialized in the dictionary. I was vaguely aware of the word “Pooterism” but thought it referred to small-minded, pompous, fussy individuals, so my preconception of City clerk Charles Pooter was probably more negative than is warranted. (In fact, “Pooterish” means taking oneself too seriously.) He’s actually a lovable, hapless Everyman who tries desperately to keep up with middle-class society but often gets it wrong. He can’t handle his champagne; and he wants so much to be funny – his are definite dad jokes avant la lettre – but only sometimes pulls it off. He regularly offends tradesmen, servants and neighbours alike, and tries but fails to ingratiate himself with his betters. Luckily, his mistakes are mild and just leave him out of favour – or pocket.

It must be rare for a fictional character to be memorialized in the dictionary. I was vaguely aware of the word “Pooterism” but thought it referred to small-minded, pompous, fussy individuals, so my preconception of City clerk Charles Pooter was probably more negative than is warranted. (In fact, “Pooterish” means taking oneself too seriously.) He’s actually a lovable, hapless Everyman who tries desperately to keep up with middle-class society but often gets it wrong. He can’t handle his champagne; and he wants so much to be funny – his are definite dad jokes avant la lettre – but only sometimes pulls it off. He regularly offends tradesmen, servants and neighbours alike, and tries but fails to ingratiate himself with his betters. Luckily, his mistakes are mild and just leave him out of favour – or pocket.

Originally serialized in Punch, the book is in short entries of one paragraph to a few pages, recounting the Pooters’ first 15 months in their new home. Events range from the mundane – home repairs and decoration – to the great excitement of being invited to the mayor’s ball. Charles and Carrie’s young adult son, Lupin (surely a partial inspiration for Roger Mortimer’s Dear Lupin and its sequels?), who comes back to live with them partway through, is a feckless bounder always being taken in by new money-making schemes and unsuitable ladies. Charles hopes to find Lupin steady employment and steer him away from his infatuation with Daisy Mutlar.

It’s well worth reading for its own sake, but also for the window onto daily Victorian life, including things that aren’t always recorded, such as fashion and slang. And it’s clever how Pooter’s pretensions get punctured by the others around him: longsuffering Carrie (“He tells me his stupid dreams every morning nearly”), insolent Lupin (“Look here, Guv.; excuse me saying so, but you’re a bit out of date”), and testy Gowing – that’s right, the neighbours are named Cummings and Gowing (“I would add, you’re a bigger fool than you look, only that’s absolutely impossible”). All very amusing. (Free from mall bookshop c. 2020) ![]()

Never fear, I’m still on track to finish the challenge by the 31st!

Carol Shields Prize Reads: Pale Shadows & All Fours

Later this evening, the Carol Shields Prize will be announced at a ceremony in Chicago. I’ve managed to read two more books from the shortlist: a sweet, delicate story about the women who guarded Emily Dickinson’s poems until their posthumous publication; and a sui generis work of autofiction that has become so much a part of popular culture that it hardly needs an introduction. Different as they are, they have themes of women’s achievements, creativity and desire in common – and so I would be happy to see either as the winner (more so than Liars, the other one I’ve read, even though that addresses similar issues). Both: ![]()

Pale Shadows by Dominique Fortier (2022; 2024)

[Translated from French by Rhonda Mullins]

This is technically a sequel to Paper Houses, which is about Emily Dickinson, but I had no trouble reading this before its predecessor. In an Author’s Note at the end, Fortier explains how, during the first Covid summer, she was stalled on multiple fiction projects and realized that all she wanted was to return to Amherst, Massachusetts – even though her subject was now dead. The poet’s presence and language haunt the novel as the characters (which include the author) wrestle over her words. The central quartet comprises Lavinia, Emily’s sister; Susan, their brother Austin’s wife; Mabel, Austin’s mistress; and Millicent, Mabel’s young daughter. Mabel is to assist with editing the higgledy-piggledy folder of handwritten poems into a volume fit for publication. Thomas Higginson’s clear aim is to tame the poetry through standardized punctuation, assigned titles, and thematic groupings. But the women are determined to let Emily’s unruly genius shine through.

This is technically a sequel to Paper Houses, which is about Emily Dickinson, but I had no trouble reading this before its predecessor. In an Author’s Note at the end, Fortier explains how, during the first Covid summer, she was stalled on multiple fiction projects and realized that all she wanted was to return to Amherst, Massachusetts – even though her subject was now dead. The poet’s presence and language haunt the novel as the characters (which include the author) wrestle over her words. The central quartet comprises Lavinia, Emily’s sister; Susan, their brother Austin’s wife; Mabel, Austin’s mistress; and Millicent, Mabel’s young daughter. Mabel is to assist with editing the higgledy-piggledy folder of handwritten poems into a volume fit for publication. Thomas Higginson’s clear aim is to tame the poetry through standardized punctuation, assigned titles, and thematic groupings. But the women are determined to let Emily’s unruly genius shine through.

The short novel rotates through perspectives as the four collide and retreat. Susan and Millicent connect over books. Mabel considers this project her own chance at immortality. At age 54, Lavinia discovers that she’s no longer content with baking pies and embarks on a surprising love affair. And Millicent perceives and channels Emily’s ghost. The writing is gorgeous, full of snow metaphors and the sorts of images that turn up in Dickinson’s poetry. It’s a lovely tribute that mingles past and present in a subtle meditation on love and legacy.

Some favourite lines:

“Emily never writes about any one thing or from any one place; she writes from alongside love, from behind death, from inside the bird.”

“Maybe this is how you live a hundred lives without shattering everything; maybe it is by living in a hundred different texts. One life per poem.”

“What Mabel senses and Higginson still refuses to see is that Emily only ever wrote half a poem; the other half belongs to the reader, it is the voice that rises up in each person as a response. And it takes these two voices, the living and the dead, to make the poem whole.”

With thanks to The Carol Shields Prize Foundation for the free e-copy for review.

All Fours by Miranda July (2024)

Miranda July’s The First Bad Man is one of the first books I ever reviewed on this blog back in 2015, after an unsolicited review copy came my way. It was so bizarre that I didn’t plan to ever read anything else by her, but I was drawn in by the hype machine and started this on my Kindle in September, later switching to a library copy when I got stuck at 65%. The narrator sets off on a road trip from Los Angeles to New York to prove to her husband, Harris, that she’s a Driver, not a Parker. But after 20 minutes she pulls off the highway and ends up at a roadside motel. She blows $20,000 on having her motel room decorated in the utmost luxury and falls for Davey, a younger man who works for a local car rental chain – and happens to be married to the decorator. In his free time, he’s a break dancer, so the narrator decides to choreograph a stunning dance to prove her love and capture his attention.

Miranda July’s The First Bad Man is one of the first books I ever reviewed on this blog back in 2015, after an unsolicited review copy came my way. It was so bizarre that I didn’t plan to ever read anything else by her, but I was drawn in by the hype machine and started this on my Kindle in September, later switching to a library copy when I got stuck at 65%. The narrator sets off on a road trip from Los Angeles to New York to prove to her husband, Harris, that she’s a Driver, not a Parker. But after 20 minutes she pulls off the highway and ends up at a roadside motel. She blows $20,000 on having her motel room decorated in the utmost luxury and falls for Davey, a younger man who works for a local car rental chain – and happens to be married to the decorator. In his free time, he’s a break dancer, so the narrator decides to choreograph a stunning dance to prove her love and capture his attention.

I got bogged down in the ridiculous details of the first two-thirds, as well as in the kinky stuff that goes on (with Davey, because neither of them is willing to technically cheat on a spouse; then with the women partners the narrator has after she and Harris decide on an open marriage). However, all throughout I had been highlighting profound lines; the novel is full to bursting with them (“maybe the road split between: a life spent longing vs. a life that was continually surprising”). I started to appreciate the story more when I thought of it as archetypal processing of women’s life experiences, including birth trauma, motherhood and perimenopause, and as an allegory for attaining an openness of outlook. What looks like an ending (of career, marriage, sexuality, etc.) doesn’t have to be.

Whereas July’s debut felt quirky for the sake of it, showing off with its deadpan raunchiness, I feel that here she is utterly in earnest. And, weird as the book may be, it works. It’s struck a chord with legions, especially middle-aged women. I remember seeing a Guardian headline about women who ditched their lives after reading All Fours. I don’t think I’ll follow suit, but I will recommend you read it and rethink what you want from life. It’s also on this year’s Women’s Prize shortlist. I suspect it’s too divisive to win either, but it certainly would be an edgy choice. (NetGalley/Public library)