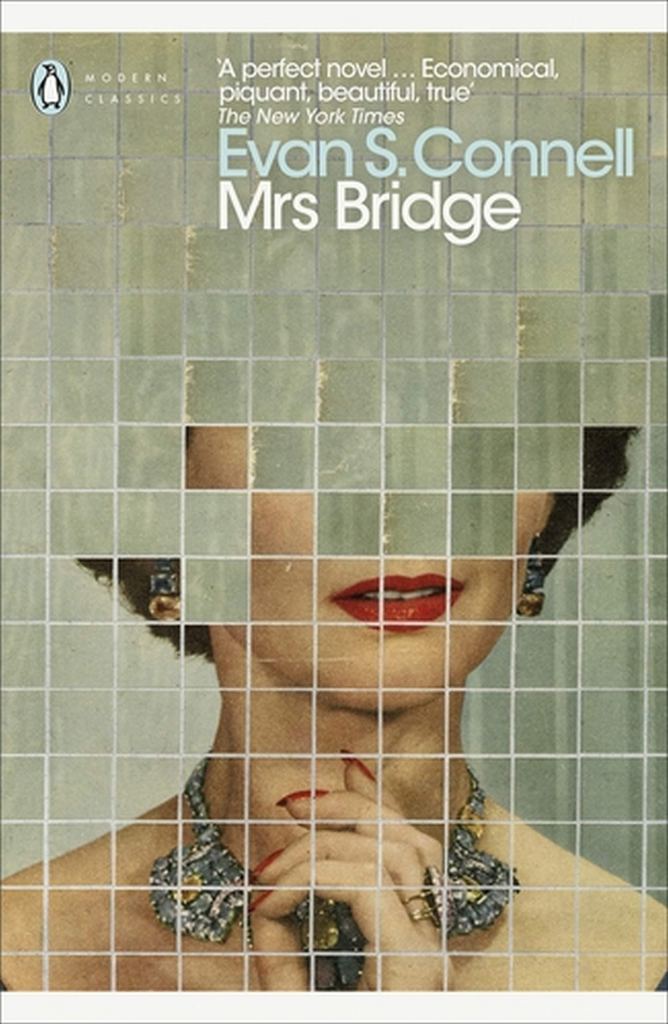

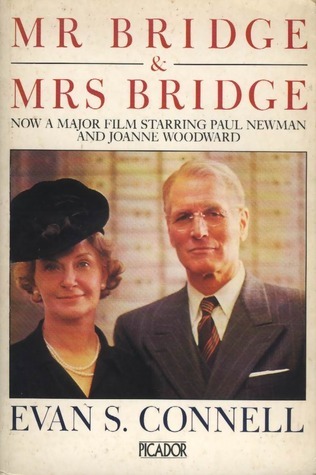

Literary Wives Club: Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell (1959)

This is the best thing we’ve read in my time with the Literary Wives online book club (out of 16 books so far). In the early pages it reminded me of Richard Yates’s work, but by the end I was thinking of it as on par with Stoner by John Williams, a masterpiece I reread last year. Is Mrs. Bridge a female Stoner? In that she is an Everywoman, representative of a certain comfortable, conventional interwar life but also of common longings to be purposeful, experience novelty, and connect with others – I’d say yes. From the first line onwards, we see her as at odds with the facts of her life, which at least appear to her to be unalterable: “Her first name was India – she was never able to get used to it.” She’s never lived up to her exotic name, she feels; her parents must have expected something of her that she couldn’t be.

Connell (1924–2013) sets this portrait of a marriage in his native Kansas City, Missouri. The story is not contemporaneous to its publication but begins in the 1930s; this doesn’t become clear until two-thirds of the way through when, on a European tour that workaholic lawyer Walter Bridge arranged as a belated birthday gift to his wife, news comes that the Nazis have invaded Poland and they have to hurry home. Bear in mind that this is the man who refused to move when a tornado threatened their country club and every single other person had moved to the basement. He insisted on staying at the table and finishing his steak. (So … he expects the weather to bow to his will, if not world leaders?) It’s an astonishing scene, and occasions an astute summation of their relationship dynamic:

It did not occur to Mrs Bridge to leave her husband and run to the basement. She had been brought up to believe without question that when a woman married she was married for the rest of her life and was meant to remain with her husband wherever he was, and under all circumstances, unless he directed her otherwise. She wished he would not be so obstinate; she wished he would behave like everyone else, but she was not particularly frightened. For nearly a quarter of a century she had done as he told her, and what he had said would happen had indeed come to pass, and what he had said would not occur had not occurred. Why, then, should she not believe him now?

(That attitude of blind faith seems more appropriate in a father–daughter or God–mortal relationship than husband–wife, does it not?)

The structure of the book must have been groundbreaking for its time: it’s in 117 short, titled vignettes – a fragmentary style later popularized by writers such as Elizabeth Hardwick, Sarah Manguso and Jenny Offill – that build a picture of the protagonist and her milieu. Even though many of them seem to concern minor incidents from the Bridges’ social life (parties, gossip, the bores they’re forced to have lunch with every time they’re in town), they also reveal a lot about India’s outlook. She wears stockings even on the hottest summer days because “it was the way things were, it was the way things had always been, and so she complied.” Like many of her time and place, she is a casual racist, evidenced by comments on her children’s Black and “gypsy” friends. It pains her that she doesn’t understand her three children. To her it seems they do strange, shocking things (okay, Douglas building a tower of junk is pretty weird) when really they’re just experimenting with fashion and sexuality as any teenager would.

India is in awe of the women of her acquaintance who step out of line, like Grace Barron and Mabel Ong. Grace, in particular, is well informed and confident arguing with men. India seriously considers breaking away from Walter and voting liberal at the next election, but loses her nerve at the last minute; her viewpoint is fundamentally conservative. The novel justifies this by showing how those who flout social rules are shamed or punished in some way.

Mostly, India feels pointless. With a housekeeper around, there’s nothing for her to do. She has nothing but leisure time she doesn’t know how to fill. And yet the years fly past, propelling her into middle age. Occasionally, she’ll summon the motivation to sign up for painting classes or start learning Spanish via records, but she never follows through. So it’s just unnecessary shopping trips in a massive Lincoln she never figures out how to park properly.

She spent a great deal of time staring into space, oppressed by the sense that she was waiting. But waiting for what? She did not know. Surely someone would call, someone must be needing her. Yet each day proceeded like the one before. … Time did not move. The home, the city, the nation, and life itself were eternal; still she had a foreboding that one day, without warning and without pity, all the dear, important things would be destroyed.

It may be fashionable to scorn the existential despair of the privileged, but this is a potent picture of a universal condition. It’s all too easy to get stuck in the status quo and feel helpless to change life for the better. I came across a Slightly Foxed article (Spring 2016) by William Palmer, “The Sadness of Mrs Bridge.” Palmer suggests that Connell was an oddity to his publishers because he wrote in so many genres, and never the same kind of book twice. He dubs this Connell’s finest work. I marked out a couple of passages from his appreciation:

The genius of Connell is to show that this is how most people live: first in their own minds, then in their families, then in their limited social circles; most historical novels fail to realize that most people simply do not notice whatever great moments of history are being enacted around them unless they actually impinge upon their lives.

What is truly compelling about Mrs Bridge is her very ordinariness, notwithstanding all her petty snobbery, conformism and timidity. The list is easy to make and appears to be a fairly damning indictment, but Connell is not writing a satirical portrait. His intention is to show us the utter uniqueness of this one human life, irreplaceability of body and soul that is India Bridge. Connell portrays her so tenderly that we come to sympathize with her and, more, to care for her.

{SOME SPOILERS IN THE REMAINDER}

The way Mrs. Bridge ends indicates that Mr. Bridge, which was published 10 years later, will be not a sequel but a companion piece. I’m somewhat wary of reading it, but it will be intriguing to see how events overlap and to what extent Connell is able to make Walter a more sympathetic character. (Palmer remarks, “It is terrifying how little the two portraits have in common – they might be describing two entirely different worlds.”) Connell’s work remains influential: Claire Fuller has featured the pair of novels in one of her year-end reading roundups, and the husband’s surname in Manguso’s Liars is Bridges.

I’ve written much more than I intended to about Mrs. Bridge, but wanted to do justice to what will no doubt be one of my stand-out reads of the year.

(My omnibus edition came from the free bookshop we used to have in the local mall.) ![]()

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

Based on Mrs. Bridge’s experience, one would be excused for thinking that being a wife involves the complete suppression of one’s own personality, ambitions and desires – including sexual, as dealt with very succinctly in the first chapter: Walter usually initiates; the one time she tries to do so, he gives her a patronizing hug and falls asleep. “This was the night Mrs Bridge concluded that while marriage might be an equitable affair, love itself was not.” A wry statement from Connell as marriage is certainly not equitable in this novel.

Granted, this was the 1910s–1930s. By the 1940s, when her daughters are young women, they’re determined to live differently, the one by becoming a New York City career girl, single and promiscuous. The other also vows to do things differently – “Listen, Mother, no man is ever going to push me around the way Daddy pushes you around” – yet ends up pregnant and battered. When India tries to encourage her to placate her husband through sex, she replies, “Oh no, don’t tell me that! I don’t want any part of that myth.”

So we see attitudes starting to change, but it would be another couple of decades before there were more options for both of these generations of women.

A common observation in many of the novels we’ve considered is that, even in a marriage, it is possible for the partners to be a complete mystery to each other. I’ll be interested to see whether Walter’s side of the story illuminates anything or portrays him as clueless. And a main moral I draw from most of our reads is that defining oneself by any relationship – mostly marriage, but also parenthood – sets one up for disappointment, or worse.

See the reviews by Becky, Kate, Kay and Naomi, too!

We recently welcomed a new member, Marianne, and will soon be choosing our books for the next two-plus years. Here’s the club page on Kay’s blog with the current members’ profiles plus all the books covered since 2013.

Our next selection will be Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri in June. I’ve not read Lahiri before but have always meant to, so I’m particularly looking forward to this one.

Book Serendipity, September through Mid-November

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away.

Thanks to Emma and Kay for posting their own Book Serendipity moments! (Liz is always good about mentioning them as she goes along, in the text of her reviews.)

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- An obsession with Judy Garland in My Judy Garland Life by Susie Boyt (no surprise there), which I read back in January, and then again in Beard: A Memoir of a Marriage by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

- Leaving a suicide note hinting at drowning oneself before disappearing in World War II Berlin; and pretending to be Jewish to gain better treatment in Aimée and Jaguar by Erica Fischer and The Lilac People by Milo Todd.

- Leaving one’s clothes on a bank to suggest drowning in The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese, read over the summer, and then Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet.

- A man expecting his wife to ‘save’ him in Amanda by H.S. Cross and Beard: A Memoir of a Marriage by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

A man tells his story of being bullied as a child in Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood and Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

A man tells his story of being bullied as a child in Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood and Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

- References to Vincent Minnelli and Walt Whitman in a story from Touchy Subjects by Emma Donoghue and Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

- The prospect of having one’s grandparents’ dining table in a tiny city apartment in Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist and Wreck by Catherine Newman.

- Ezra Pound’s dodgy ideology was an element in The Dime Museum by Joyce Hinnefeld, which I reviewed over the summer, and recurs in Swann by Carol Shields.

- A character has heart palpitations in Andrew Miller’s story from The BBC National Short Story Award 2025 anthology and Endling by Maria Reva.

- A (semi-)nude man sees a worker outside the window and closes the curtains in one story of Cathedral by Raymond Carver and one from Good and Evil and Other Stories by Samanta Schweblin.

- The call of the cuckoo is mentioned in The Edge of Silence by Neil Ansell and Of All that Ends by Günter Grass.

A couple in Italy who have a Fiat in Of All that Ends by Günter Grass and Caoilinn Hughes’s story from The BBC National Short Story Award 2025 anthology.

A couple in Italy who have a Fiat in Of All that Ends by Günter Grass and Caoilinn Hughes’s story from The BBC National Short Story Award 2025 anthology.

- Balzac’s excessive coffee consumption was mentioned in Au Revoir, Tristesse by Viv Groskop, one of my 20 Books of Summer, and then again in The Writer’s Table by Valerie Stivers.

- The main character is rescued from her suicide plan by a madcap idea in The Wedding People by Alison Espach and Endling by Maria Reva.

- The protagonist is taking methotrexate in Sea, Poison by Caren Beilin and Wreck by Catherine Newman.

- A man wears a top hat in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and one story of Cathedral by Raymond Carver.

- A man named Angus is the murderer in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and Swann by Carol Shields.

The thing most noticed about a woman is a hair on her chin in the story “Pluck” in Touchy Subjects by Emma Donoghue and Swann by Carol Shields.

The thing most noticed about a woman is a hair on her chin in the story “Pluck” in Touchy Subjects by Emma Donoghue and Swann by Carol Shields.

- The female main character makes a point of saying she doesn’t wear a bra in Sea, Poison by Caren Beilin and Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

- A home hairdressing business in one story of Cathedral by Raymond Carver and Emil & the Detectives by Erich Kästner.

- Painting a bathroom fixture red: a bathtub in The Diary of a Nobody by George Grossmith, one of my 20 Books of Summer; and a toilet in Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

- A teenager who loses a leg in a road accident in individual stories from A Wild Swan by Michael Cunningham and the Racket anthology (ed. Lisa Moore).

- Digging up the casket of a loved one in the wee hours features in Pet Sematary by Stephen King, one of my 20 Books of Summer; and one story of Pretty Monsters by Kelly Link.

- A character named Dani in the story “The St. Alwynn Girls at Sea” by Sheila Heti and The Silver Book by Olivia Laing; later, author Dani Netherclift (Vessel).

Obsessive cultivation of potatoes in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and The Martian by Andy Weir.

Obsessive cultivation of potatoes in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and The Martian by Andy Weir.

- The story of Dante Gabriel Rossetti digging up the poems he buried with his love is recounted in Sharon Bala’s story in the Racket anthology (ed. Lisa Moore) and one of the stories in Pretty Monsters by Kelly Link.

- Putting French word labels on objects in Alone in the Classroom by Elizabeth Hay and Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

A man with part of his finger missing in Find Him! by Elaine Kraf and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

A man with part of his finger missing in Find Him! by Elaine Kraf and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

- In Minor Black Figures by Brandon Taylor, I came across a mention of the Italian film director Pier Paolo Pasolini, who is a character in The Silver Book by Olivia Laing.

- A character who works in an Ohio hardware store in Flashlight by Susan Choi and Buckeye by Patrick Ryan (two one-word-titled doorstoppers I skimmed from the library). There’s also a family-owned hardware store in Alone in the Classroom by Elizabeth Hay.

- A drowned father – I feel like drownings in general happen much more often in fiction than they do in real life – in The Homecoming by Zoë Apostolides, Flashlight by Susan Choi, and Vessel by Dani Netherclift (as well as multiple drownings in The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese, one of my 20 Books of Summer).

- A memoir by a British man who’s hard of hearing but has resisted wearing hearing aids in the past: first The Quiet Ear by Raymond Antrobus over the summer, then The Edge of Silence by Neil Ansell.

A loved one is given a six-month cancer prognosis but lives another (nearly) two years in All the Way to the River by Elizabeth Gilbert and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

A loved one is given a six-month cancer prognosis but lives another (nearly) two years in All the Way to the River by Elizabeth Gilbert and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

- A man’s brain tumour is diagnosed by accident while he’s in hospital after an unrelated accident in Flashlight by Susan Choi and Saltwash by Andrew Michael Hurley.

- Famous lost poems in What We Can Know by Ian McEwan and Swann by Carol Shields.

- A description of the anatomy of the ear and how sound vibrates against tiny bones in The Edge of Silence by Neil Ansell and What Stalks the Deep by T. Kingfisher.

- Notes on how to make decadent mashed potatoes in Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist, Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry, and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

- Transplant surgery on a dog in Russia and trepanning appear in The Heart of a Dog by Mikhail Bulgakov and the poetry collection Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung.

- Audre Lorde, whose Sister Outsider I was reading at the time, is mentioned in Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl. Lorde’s line about the master’s tools never dismantling the master’s house is also paraphrased in Spent by Alison Bechdel.

- An adult appears as if fully formed in a man’s apartment but needs to be taught everything, including language and toilet training, in The Heart of a Dog by Mikhail Bulgakov and Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

Two sisters who each wrote a memoir about their upbringing in Spent by Alison Bechdel and Vessel by Dani Netherclift.

Two sisters who each wrote a memoir about their upbringing in Spent by Alison Bechdel and Vessel by Dani Netherclift.

- The fact that ragwort is bad for horses if it gets mixed up into their feed was mentioned in Ghosts of the Farm by Nicola Chester and Understorey by Anna Chapman Parker.

- The Sylvia Plath line “the O-gape of complete despair” was mentioned in Vessel by Dani Netherclift, then I read it in its original place in Ariel later the same day.

- A mention of the Baba Yaga folk tale (an old woman who lives in the forest in a hut on chicken legs) in Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung and Woman, Eating by Claire Kohda. [There was a copy of Sophie Anderson’s children’s book The House with Chicken Legs in the Little Free Library around that time, too.]

- Coming across a bird that seems to have simply dropped dead in Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito, Vessel by Dani Netherclift, and Rainforest by Michelle Paver.

- Contemplating a mound of hair in Vessel by Dani Netherclift (at Auschwitz) and Year of the Water Horse by Janice Page (at a hairdresser’s).

- Family members are warned that they should not see the body of their loved one in Vessel by Dani Netherclift and Rainforest by Michelle Paver.

- A father(-in-law)’s swift death from oesophageal cancer in Year of the Water Horse by Janice Page and Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry.

- I saw John Keats’s concept of negative capability discussed first in My Little Donkey by Martha Cooley and then in Understorey by Anna Chapman Parker.

- I started two books with an Anne Sexton epigraph on the same day: A Portable Shelter by Kirsty Logan and Slags by Emma Jane Unsworth.

- Mentions of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination in Q’s Legacy by Helene Hanff and Sister Outsider for Audre Lorde, both of which I was reading for Novellas in November.

- Mentions of specific incidents from Samuel Pepys’s diary in Q’s Legacy by Helene Hanff and Gin by Shonna Milliken Humphrey, both of which I was reading for Nonfiction November/Novellas in November.

- Starseed (aliens living on earth in human form) in Beautyland by Marie-Helene Bertino and The Conspiracists by Noelle Cook.

- Reading nonfiction by two long-time New Yorker writers at the same time: Life on a Little-Known Planet by Elizabeth Kolbert and Joyride by Susan Orlean.

- The breaking of a mirror seems like a bad omen in The Spare Room by Helen Garner and The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath.

The author’s husband (who has a name beginning with P) is having an affair with a lawyer in Catching Sight by Deni Elliott and Joyride by Susan Orlean.

The author’s husband (who has a name beginning with P) is having an affair with a lawyer in Catching Sight by Deni Elliott and Joyride by Susan Orlean.

- Mentions of Lewis Hyde’s book The Gift in Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl and The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer; I promptly ordered the Hyde secondhand!

- The protagonist fears being/is accused of trying to steal someone else’s cat in Minka and Curdy by Antonia White and Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen by P.G. Wodehouse, both of which I was reading for Novellas in November.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Three on a Theme of Sylvia Plath (The Slicks by Maggie Nelson for #NonfictionNovember & #NovNov25; The Bell Jar and Ariel)

A review copy of Maggie Nelson’s brand-new biographical essay on Sylvia Plath (and Taylor Swift) was the excuse I needed to finally finish a long-neglected paperback of The Bell Jar and also get a taste of Plath’s poetry through the posthumous collection Ariel, which is celebrating its 60th anniversary. These are the sorts of works it’s hard to believe ever didn’t exist; they feel so fully formed and part of the zeitgeist. It also boggles the mind how much Plath accomplished before her death by suicide at age 30. What I previously knew of her life mostly came from hearsay and was reinforced by Euphoria by Elin Cullhed. For the mixture of nonfiction, fiction and poetry represented below, I’m counting this towards Nonfiction November’s Book Pairings week.

The Slicks: On Sylvia Plath and Taylor Swift by Maggie Nelson (2025)

Can young women embrace fame amidst the other cultural expectations of them? Nelson attempts to answer this question by comparing two figures who turn(ed) life into art. The link between them was strengthened by Swift titling her 2024 album The Tortured Poets Department. “Plath … serves as a metonym – as does Swift – for a woman who makes art about a broken heart,” Nelson writes. “When women make the personal public, the charge of whorishness always lurks nearby.” What women are allowed to say and do has always, it seems, attracted public commentary, and “anyone who puts their work into the world, at any level, must learn to navigate between self-protectiveness and risk, becoming harder and staying soft.”

Can young women embrace fame amidst the other cultural expectations of them? Nelson attempts to answer this question by comparing two figures who turn(ed) life into art. The link between them was strengthened by Swift titling her 2024 album The Tortured Poets Department. “Plath … serves as a metonym – as does Swift – for a woman who makes art about a broken heart,” Nelson writes. “When women make the personal public, the charge of whorishness always lurks nearby.” What women are allowed to say and do has always, it seems, attracted public commentary, and “anyone who puts their work into the world, at any level, must learn to navigate between self-protectiveness and risk, becoming harder and staying soft.”

Nelson acknowledges a major tonal difference between Plath and Swift, however. Plath longed for fame but didn’t get the chance to enjoy it; she’s the patron saint of sad-girl poetry and makes frequent reference to death, whereas Swift spotlights joy and female empowerment. It’s a shame this was out of date before it went to print; my advanced copy, at least, isn’t able to comment on Swift’s engagement and the baby rumour mill sure to follow. It would be illuminating to have an afterword in which Nelson discusses the effect of spouses’ competing fame and speculates on how motherhood might change Swift’s art.

Full confession: I’ve only ever knowingly heard one Taylor Swift song, “Anti-Hero,” on the radio in the States. (My assessment was: wordy, angsty, reasonably catchy.) Undoubtedly, I would have gotten more out of this essay were I equally familiar with the two subjects. Nonetheless, it’s fluid and well argued, and I was engaged throughout. If you’re a Swiftie as well as a literary type, you need to read this.

[66 pages]

With thanks to Vintage (Penguin) for the advanced e-copy for review.

The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath (1963)

Given my love of mental hospital accounts and women’s autofiction, it’s a wonder I’d not read this before my forties. It was first published under the pseudonym “Victoria Lucas” because Plath thought it immature, “an autobiographical apprentice work which I had to write in order to free myself from the past.” Esther Greenwood is the stand-in for Plath: a talented college student who, after working in New York City during the remarkable summer of 1953, plunges into mental ill health. Chapter 13 is amazing and awful at the same time as Esther attempts suicide thrice in one day, toying with a silk bathrobe cord and ocean waves before taking 50 pills and walling herself into a corner of the cellar. She bounces between various institutional settings, undergoing electroshock therapy – the first time it’s horrible, but later, under a kind female doctor, it’s more like it’s ‘supposed’ to be: a calming reset.

Given my love of mental hospital accounts and women’s autofiction, it’s a wonder I’d not read this before my forties. It was first published under the pseudonym “Victoria Lucas” because Plath thought it immature, “an autobiographical apprentice work which I had to write in order to free myself from the past.” Esther Greenwood is the stand-in for Plath: a talented college student who, after working in New York City during the remarkable summer of 1953, plunges into mental ill health. Chapter 13 is amazing and awful at the same time as Esther attempts suicide thrice in one day, toying with a silk bathrobe cord and ocean waves before taking 50 pills and walling herself into a corner of the cellar. She bounces between various institutional settings, undergoing electroshock therapy – the first time it’s horrible, but later, under a kind female doctor, it’s more like it’s ‘supposed’ to be: a calming reset.

The 19-year-old is obsessed with the notion of purity. She has a couple of boyfriends but decides to look for someone else to take her virginity. Beforehand, the asylum doctor prescribes her a fitting for a diaphragm. A defiant claim to the right to contraception despite being unmarried is a way of resisting the bell jar – the rarefied prison – of motherhood. Still, Esther feels guilty about prioritizing her work over what seems like feminine duty: “Why was I so maternal and apart? Why couldn’t I dream of devoting myself to baby after fat puling baby? … I was my own woman.” Plath never reconciled parenthood with poetry. Whether that’s the fault of Ted Hughes, or the times they lived in, who can say. For her and for Esther, the hospital is a prison as well – but not so hermetic as the turmoil of her own mind. How ironic to read “I took a deep breath and listened to the old brag of my heart. I am, I am, I am” knowing that this was published just a few weeks before this literary genius ceased to be.

The 19-year-old is obsessed with the notion of purity. She has a couple of boyfriends but decides to look for someone else to take her virginity. Beforehand, the asylum doctor prescribes her a fitting for a diaphragm. A defiant claim to the right to contraception despite being unmarried is a way of resisting the bell jar – the rarefied prison – of motherhood. Still, Esther feels guilty about prioritizing her work over what seems like feminine duty: “Why was I so maternal and apart? Why couldn’t I dream of devoting myself to baby after fat puling baby? … I was my own woman.” Plath never reconciled parenthood with poetry. Whether that’s the fault of Ted Hughes, or the times they lived in, who can say. For her and for Esther, the hospital is a prison as well – but not so hermetic as the turmoil of her own mind. How ironic to read “I took a deep breath and listened to the old brag of my heart. I am, I am, I am” knowing that this was published just a few weeks before this literary genius ceased to be.

Apart from an unfortunate portrayal of a “negro” worker at the hospital, this was an enduringly relevant and absorbing read, a classic to sit alongside Emily Holmes Coleman’s The Shutter of Snow and Janet Frame’s Faces in the Water.

(Secondhand – it’s been in my collection so long I can’t remember where it’s from, but I’d guess a Bowie Library book sale or Wonder Book & Video / Public library – I was struggling with the small type so switched to a recent paperback and found it more readable)

Ariel by Sylvia Plath (1965)

Impossible not to read this looking for clues of her death to come:

Dying

Is an art, like everything else.

I do it exceptionally well.

(from “Lady Lazarus”)

Eternity bores me,

I never wanted it.

(from “Years”)

The woman is perfected.

Her dead

Body wears the smile of accomplishment

(from “Edge”)

I feel incapable of saying anything fresh about this collection, which takes no prisoners. The images and vocabulary are razor-sharp. First and last lines or stanzas are particularly memorable. (“Morning Song” starts “Love set you going like a fat gold watch”; “Lady Lazarus” ends “Out of the ash / I rise with my red hair / And I eat men like air.”) Words and phrases repeat and gather power as they go. “The Applicant” mocks the obligations of a wife: “A living doll … / It can sew, it can cook. It can talk, talk, talk. … // … My boy, it’s your last resort. / Will you marry it, marry it, marry it.” I don’t know a lot about Plath’s family life, only that her father was a Polish immigrant and died after a long illness when she was eight, but there must have been some daddy issues there – after all, “Daddy” includes the barbs “Daddy, I have had to kill you” and “If I’ve killed one man, I’ve killed two— / The vampire who said he was you / And drank my blood for a year, / Seven years, if you want to know.” It ends, “Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through.” Several later poems in a row, including “Stings,” incorporate bee-related imagery, and Plath’s father was an international bee expert. I can see myself reading this again and again in future, and finding her other collections, too – all but one of them posthumous. (Secondhand – RSPCA charity shop, Newbury)

I feel incapable of saying anything fresh about this collection, which takes no prisoners. The images and vocabulary are razor-sharp. First and last lines or stanzas are particularly memorable. (“Morning Song” starts “Love set you going like a fat gold watch”; “Lady Lazarus” ends “Out of the ash / I rise with my red hair / And I eat men like air.”) Words and phrases repeat and gather power as they go. “The Applicant” mocks the obligations of a wife: “A living doll … / It can sew, it can cook. It can talk, talk, talk. … // … My boy, it’s your last resort. / Will you marry it, marry it, marry it.” I don’t know a lot about Plath’s family life, only that her father was a Polish immigrant and died after a long illness when she was eight, but there must have been some daddy issues there – after all, “Daddy” includes the barbs “Daddy, I have had to kill you” and “If I’ve killed one man, I’ve killed two— / The vampire who said he was you / And drank my blood for a year, / Seven years, if you want to know.” It ends, “Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through.” Several later poems in a row, including “Stings,” incorporate bee-related imagery, and Plath’s father was an international bee expert. I can see myself reading this again and again in future, and finding her other collections, too – all but one of them posthumous. (Secondhand – RSPCA charity shop, Newbury)

Literary Wives Club: Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins (2008)

Although Emily Perkins was a new name to me, the New Zealand author has published five novels and a short story collection. Unfortunately, I never engaged with her London-set Novel About My Wife. On the one hand, it must have been an intriguing challenge for Perkins to inhabit a man’s perspective and examine how a widower might recreate his marriage and his late wife’s mental state. “I can’t speak for Ann[,] obviously, only about her,” screenwriter Tom Stone admits. On the other hand, Tom is so egotistical and self-absorbed that his portrait of Ann is more obfuscating than illuminating.

Although Emily Perkins was a new name to me, the New Zealand author has published five novels and a short story collection. Unfortunately, I never engaged with her London-set Novel About My Wife. On the one hand, it must have been an intriguing challenge for Perkins to inhabit a man’s perspective and examine how a widower might recreate his marriage and his late wife’s mental state. “I can’t speak for Ann[,] obviously, only about her,” screenwriter Tom Stone admits. On the other hand, Tom is so egotistical and self-absorbed that his portrait of Ann is more obfuscating than illuminating.

“If I could build her again using words, I would,” he opens, but that promising start just leads into paragraphs of physical description. Bare facts, such as that Ann was from Sydney and created radiation masks for cancer patients in a hospital, are hardly revealing. We mostly know Ann through her delusions. In her late thirties, when she was three months pregnant with their son Arlo, she was caught in an underground train derailment. Thereafter, she increasingly fell victim to paranoia, believing that she was being stalked and that their house was infested. We’re invited to speculate that pregnancy exacerbated her mental health issues and that postpartum psychosis may have had something to do with her death.

I mostly skimmed the novel, so I may have missed some plot points, but what stood out to me were Tom’s unpleasant depictions of women and complaints about his faltering career. (He’s envious of a new acquaintance, Simon, who’s back and forth to Hollywood all the time for successful screenwriting projects.) Interspersed are seemingly pointless excerpts from Tom’s screenplay about a trip he and Ann took to Fiji. I longed for the balance of another perspective. This had a bit of the flavour of early Maggie O’Farrell, but none of the warmth. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

Being generous to Perkins, perhaps the very point she was trying to make is that it’s impossible to get outside of one’s own perspective and understand what’s going on with a spouse, especially one who has mental health struggles. Had Tom been more attentive and supportive, might things have ended differently?

See Becky’s, Kate’s and Kay’s reviews, too! (Naomi is on a break this month.)

Coming up next, in December: The Soul of Kindness by Elizabeth Taylor.

Three Days in June vs. Three Weeks in July

Two very good 2025 releases that I read from the library. While they could hardly be more different in tone and particulars, I couldn’t resist linking them via their titles.

Three Days in June by Anne Tyler

(From my Most Anticipated list.) A delightful little book that I loved more than I expected to, for several reasons: the effective use of a wedding weekend as a way of examining what goes wrong in marriages and what we choose to live with versus what we can’t forgive; Gail’s first-person narration, a rarity for Tyler* and a decision that adds depth to what might otherwise have been a two-dimensional depiction of a woman whose people skills leave something to be desired; and the unexpected presence of a cat who brings warmth and caprice back into her home. (I read this soon after losing my old cat, and it was comforting to be reminded that cats and their funny ways are the same the world over.)

From Tyler’s oeuvre, this reminded me most of The Amateur Marriage and has a surprise Larry’s Party-esque ending. The discussion of the outmoded practice of tapping one’s watch is a neat tie-in to her recurring theme of the nature of time. And through the lunch out at a chic crab restaurant, she succeeds at making the Baltimore setting essential rather than incidental, more so than in much of her other work.

Gail is in the sandwich generation with a daughter just married and an old mother who’s just about independent. I appreciated that she’s 61 and contemplating retirement, but still feels as if she hasn’t a clue: “What was I supposed to do with the rest of my life? I’m too young for this, I thought. Not too old, as you might expect, but too young, too inept, too uninformed. How come there weren’t any grownups around? Why did everyone just assume I knew what I was doing?”

My only misgiving is that Tyler doesn’t quite get it right about the younger generation: women who are in their early thirties in 2023 (so born about 1990) wouldn’t be called Debbie and Bitsy. To some degree, Tyler’s still stuck back in the 1970s, but her observations about married couples and family dynamics are as shrewd as ever. Especially because of the novella length, I can recommend this to readers wanting to try Tyler for the first time. ![]()

*I’ve noted it in Earthly Possessions. Anywhere else?

Three Weeks in July: 7/7, The Aftermath, and the Deadly Manhunt by Adam Wishart and James Nally

July 7th is my wedding anniversary but before that, and ever since, it’s been known as the date of the UK’s worst terrorist attack, a sort of lesser 9/11 – and while reading this I felt the same way that I’ve felt reading books about 9/11: a sort of awed horror. Suicide bombers who were born in the UK but radicalized on trips to Islamic training camps in Pakistan set off explosions on three Underground trains and one London bus. I didn’t think my memories of 7/7 were strong, yet some names were incredibly familiar to me (chiefly Mohammad Sidique Khan, the leader of the attacks; Jean Charles de Menezes, the innocent Brazilian electrician shot dead on a Tube train when confused with a suspect in the 21/7 copycat plot – police were operating under a new shoot-to-kill policy and this was the tragic result).

Fifty-two people were killed that day, ranging in age from 20 to 60; 20 were not UK citizens, hailing from everywhere from Grenada to Mauritius. But a total of 770 people were injured. I found the authors’ recreation of events very gripping, though do be warned that there is a lot of gruesome medical and forensic detail about fatalities and injuries. They humanize the scale of events and make things personal by focusing on four individuals who were injured, even losing multiple limbs in some cases, but survived and now work in motivational speaking, disability services or survivor advocacy.

Fifty-two people were killed that day, ranging in age from 20 to 60; 20 were not UK citizens, hailing from everywhere from Grenada to Mauritius. But a total of 770 people were injured. I found the authors’ recreation of events very gripping, though do be warned that there is a lot of gruesome medical and forensic detail about fatalities and injuries. They humanize the scale of events and make things personal by focusing on four individuals who were injured, even losing multiple limbs in some cases, but survived and now work in motivational speaking, disability services or survivor advocacy.

What really got to me was thinking about all the hundreds of people who, 20 years on, still live with permanent pain, disability or grief because of the randomness of them or their loved ones getting caught up in a few misguided zealots’ plot. One detail that particularly struck me: with the Tube tunnels closed off at both ends while searchers recovered bodies, the temperature rose to 50 degrees C (122 degrees F), only exacerbating the stench. The book mostly avoids cliches and overwriting, though I did find myself skimming in places. It is based on the research done for a BBC documentary series and synthesizes a lot of material in an engaging way that does justice to the victims. ![]()

Have you read one or both of these?

Could you see yourself picking one of them up?

Literary Wives Club: The Constant Wife by W. Somerset Maugham (1927)

As far as I know, this is the first play we’ve chosen for the club. While I’m a Maugham fan, I haven’t read him in a while and I’ve never explored his work for the theatre. The Constant Wife is a straightforward three-act play with one setting: a large parlour in the Middletons’ home in Harley Street, London. A true drawing room comedy, then, with very simple staging.

{SPOILERS IN THE REMAINDER}

Rumours are circulating that surgeon John Middleton has been having an affair with his wife Constance’s best friend, Marie-Louise. It’s news to Mrs. Culver and Martha, Constance’s mother and sister – but not to Constance herself. Mrs. Culver, the traditional voice of a previous generation, opines that men are wont to stray and so long as the wife doesn’t find out, what harm can it do? Women, on the other hand, are “naturally faithful creatures and we’re faithful because we have no particular inclination to be anything else,” she says.

Other characters enter in twos and threes for gossip and repartee and the occasional confrontation. Marie-Louise’s husband, Mortimer Durham, shows up fuming because he’s found John’s cigarette-case under her pillow and assumes it can only mean one thing. Constance is in the odd position of defending her husband’s and best friend’s honour, even though she knows full well that they’re guilty. With her white lies, she does them the kindness of keeping their indiscretion quiet – and gives herself the moral upper hand.

Constance is matter of fact about the fading of romance. She is grateful to have had a blissful first five years of marriage; how convenient that both she and John then fell out of love with each other at the same time. The decade since has been about practicalities. Thanks to John, she has a home, respectability, and fine belongings (also a child, only mentioned in passing); why give all that up? She’s still fond of John, anyway, and his infidelity has only bruised her vanity. However, she wants more from life, and a sheepish John is inclined to give her whatever she asks. So she agrees to join an acquaintance’s interior decorating business.

The early reappearance of her old flame Bernard Kersal, who is clearly still smitten with her, seeds her even more daring decision in the final act, set one year after the main events. Having earned £1400 of her own money, she has more than enough to cover a six-week holiday in Italy. She announces to John that she’s deposited the remainder in his account “for my year’s keep,” and slyly adds that she’ll be travelling with Bernard. This part turns out to be a bluff, but it’s her way of testing their new balance of power. “I’m not dependent on John. I’m economically independent, and therefore I claim my sexual independence,” she declares in her mother’s company.

There are some very funny moments in the play, such as when Constance tells her mother she’ll place a handkerchief on the piano as a secret sign during a conversation. Her mother then forgets what it signifies and Constance ends up pulling three hankies in a row from her handbag. I had to laugh at Mrs. Culver’s test for knowing whether you’re in love with someone: “Could you use his toothbrush?” It’s also amusing that Constance ends up being the one to break up with John for Marie-Louise, and with Marie-Louise for John.

However, there are also hidden depths of feeling meant to be brought out by the actors. At least three times in scenes between John and Constance, I noted the stage direction “Breaking down” in parentheses. The audience, therefore, is sometimes privy to the emotion that these characters can’t express to each other because of their sardonic wit and stiff upper lips.

I hardly ever experience plays, so this was interesting for a change. At only 70-some pages, it’s a quick read even if a bit old-fashioned or tedious in places. It does seem ahead of its time in questioning just what being true to a spouse might mean. A clever and iconoclastic comedy of manners, it’s a pleasant waystation between Oscar Wilde and Alan Ayckbourn.

(Free download from Internet Archive – is this legit or a copyright scam??) ![]()

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

Answered by means of quotes from Constance.

- Partnership is important, yes, but so is independence. (Money matters often crop up in the books we read for the club.)

“there is only one freedom that is really important, and that is economic freedom”

- Marriage often outlasts the initial spark of lust, and can survive one or both partners’ sexual peccadilloes. (Maugham, of course, was a closeted homosexual married to a woman.)

“I am tired of being the modern wife.” When her mother asks for clarification, she adds rather bluntly, “A prostitute who doesn’t deliver the goods.”

“I may be unfaithful, but I am constant. I always think that’s my most endearing quality.”

We have a new member joining us this month: Becky, from Australia, who blogs at Aidanvale. Welcome! Here’s the group’s page on Kay’s website.

See Becky’s, Kate’s, Kay’s and Naomi’s reviews, too!

Coming up next, in September: Novel about My Wife by Emily Perkins

Carol Shields Prize Reads: Pale Shadows & All Fours

Later this evening, the Carol Shields Prize will be announced at a ceremony in Chicago. I’ve managed to read two more books from the shortlist: a sweet, delicate story about the women who guarded Emily Dickinson’s poems until their posthumous publication; and a sui generis work of autofiction that has become so much a part of popular culture that it hardly needs an introduction. Different as they are, they have themes of women’s achievements, creativity and desire in common – and so I would be happy to see either as the winner (more so than Liars, the other one I’ve read, even though that addresses similar issues). Both: ![]()

Pale Shadows by Dominique Fortier (2022; 2024)

[Translated from French by Rhonda Mullins]

This is technically a sequel to Paper Houses, which is about Emily Dickinson, but I had no trouble reading this before its predecessor. In an Author’s Note at the end, Fortier explains how, during the first Covid summer, she was stalled on multiple fiction projects and realized that all she wanted was to return to Amherst, Massachusetts – even though her subject was now dead. The poet’s presence and language haunt the novel as the characters (which include the author) wrestle over her words. The central quartet comprises Lavinia, Emily’s sister; Susan, their brother Austin’s wife; Mabel, Austin’s mistress; and Millicent, Mabel’s young daughter. Mabel is to assist with editing the higgledy-piggledy folder of handwritten poems into a volume fit for publication. Thomas Higginson’s clear aim is to tame the poetry through standardized punctuation, assigned titles, and thematic groupings. But the women are determined to let Emily’s unruly genius shine through.

This is technically a sequel to Paper Houses, which is about Emily Dickinson, but I had no trouble reading this before its predecessor. In an Author’s Note at the end, Fortier explains how, during the first Covid summer, she was stalled on multiple fiction projects and realized that all she wanted was to return to Amherst, Massachusetts – even though her subject was now dead. The poet’s presence and language haunt the novel as the characters (which include the author) wrestle over her words. The central quartet comprises Lavinia, Emily’s sister; Susan, their brother Austin’s wife; Mabel, Austin’s mistress; and Millicent, Mabel’s young daughter. Mabel is to assist with editing the higgledy-piggledy folder of handwritten poems into a volume fit for publication. Thomas Higginson’s clear aim is to tame the poetry through standardized punctuation, assigned titles, and thematic groupings. But the women are determined to let Emily’s unruly genius shine through.

The short novel rotates through perspectives as the four collide and retreat. Susan and Millicent connect over books. Mabel considers this project her own chance at immortality. At age 54, Lavinia discovers that she’s no longer content with baking pies and embarks on a surprising love affair. And Millicent perceives and channels Emily’s ghost. The writing is gorgeous, full of snow metaphors and the sorts of images that turn up in Dickinson’s poetry. It’s a lovely tribute that mingles past and present in a subtle meditation on love and legacy.

Some favourite lines:

“Emily never writes about any one thing or from any one place; she writes from alongside love, from behind death, from inside the bird.”

“Maybe this is how you live a hundred lives without shattering everything; maybe it is by living in a hundred different texts. One life per poem.”

“What Mabel senses and Higginson still refuses to see is that Emily only ever wrote half a poem; the other half belongs to the reader, it is the voice that rises up in each person as a response. And it takes these two voices, the living and the dead, to make the poem whole.”

With thanks to The Carol Shields Prize Foundation for the free e-copy for review.

All Fours by Miranda July (2024)

Miranda July’s The First Bad Man is one of the first books I ever reviewed on this blog back in 2015, after an unsolicited review copy came my way. It was so bizarre that I didn’t plan to ever read anything else by her, but I was drawn in by the hype machine and started this on my Kindle in September, later switching to a library copy when I got stuck at 65%. The narrator sets off on a road trip from Los Angeles to New York to prove to her husband, Harris, that she’s a Driver, not a Parker. But after 20 minutes she pulls off the highway and ends up at a roadside motel. She blows $20,000 on having her motel room decorated in the utmost luxury and falls for Davey, a younger man who works for a local car rental chain – and happens to be married to the decorator. In his free time, he’s a break dancer, so the narrator decides to choreograph a stunning dance to prove her love and capture his attention.

Miranda July’s The First Bad Man is one of the first books I ever reviewed on this blog back in 2015, after an unsolicited review copy came my way. It was so bizarre that I didn’t plan to ever read anything else by her, but I was drawn in by the hype machine and started this on my Kindle in September, later switching to a library copy when I got stuck at 65%. The narrator sets off on a road trip from Los Angeles to New York to prove to her husband, Harris, that she’s a Driver, not a Parker. But after 20 minutes she pulls off the highway and ends up at a roadside motel. She blows $20,000 on having her motel room decorated in the utmost luxury and falls for Davey, a younger man who works for a local car rental chain – and happens to be married to the decorator. In his free time, he’s a break dancer, so the narrator decides to choreograph a stunning dance to prove her love and capture his attention.

I got bogged down in the ridiculous details of the first two-thirds, as well as in the kinky stuff that goes on (with Davey, because neither of them is willing to technically cheat on a spouse; then with the women partners the narrator has after she and Harris decide on an open marriage). However, all throughout I had been highlighting profound lines; the novel is full to bursting with them (“maybe the road split between: a life spent longing vs. a life that was continually surprising”). I started to appreciate the story more when I thought of it as archetypal processing of women’s life experiences, including birth trauma, motherhood and perimenopause, and as an allegory for attaining an openness of outlook. What looks like an ending (of career, marriage, sexuality, etc.) doesn’t have to be.

Whereas July’s debut felt quirky for the sake of it, showing off with its deadpan raunchiness, I feel that here she is utterly in earnest. And, weird as the book may be, it works. It’s struck a chord with legions, especially middle-aged women. I remember seeing a Guardian headline about women who ditched their lives after reading All Fours. I don’t think I’ll follow suit, but I will recommend you read it and rethink what you want from life. It’s also on this year’s Women’s Prize shortlist. I suspect it’s too divisive to win either, but it certainly would be an edgy choice. (NetGalley/Public library)

(My full thoughts on both longlists are here.) The other two books on the Carol Shields Prize shortlist are River East, River West by Aube Rey Lescure and Code Noir by Canisia Lubrin, about which I know very little. In its first two years, the Prize was awarded to women of South Asian extraction. Somehow, I can’t see the jury choosing one of three white women when it could be a Black woman (Lubrin) instead. However, Liars and All Fours feel particularly zeitgeist-y. I would be disappointed if the former won because of its bitter tone, though Manguso is an undeniable talent. Pale Shadows? Pure literary loveliness, if evanescent. But honouring a translation would make a statement, too. I’ll find out in the morning!

Literary Wives Club: Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus (2022)

Like pretty much every other woman over 30 on the planet, I read Lessons in Chemistry when it first came out. I was happy for my book club to select it for a later month when I was away; it made a decent selection but I had no need to revisit it, then or now. I think it still holds the record for the longest reservation queue in my library system. I enjoyed this feel-good feminist story well enough but found certain elements hokey, such as Six-Thirty the dog’s preternatural intelligence and Elizabeth Zott’s neurodivergent-like bluntness and lack of sentimentality.

My original review: Elizabeth Zott is a scientist through and through, applying a chemist’s mindset to her every venture, including cooking, rowing and single motherhood in the 1950s. When she is fired from her job in a chemistry lab and gets a gig as a TV cooking show host instead, she sees it as her mission to treat housewives as men’s intellectual equals, but there are plenty of people who don’t care for her unusual methods and free thinking. I was reminded strongly of The Atomic Weight of Love and The Rosie Project, as well as novels by Katherine Heiny and especially John Irving with the deep dive into backstory and particular pet subjects, and the orphan history for Zott’s love interest. This was an enjoyable tragicomedy. You have to cheer for the triumphs she and other female characters win against the system of the time. However, the very precocious child (and dog) stretch belief, and the ending was too pat for me. (Public library) ![]()

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

Elizabeth is deeply in love with Calvin Evans yet refuses to be his wife. She spurns marriage because she correctly intuits that it will limit her prospects, this being the 1960s. “I’m going to be a scientist. Successful women scientists don’t marry,” she tells her mother. Forasmuch as she assumes her television audience to be traditional housewives, she rejects their situation for herself. A single mother, a minor celebrity, a scientific researcher: none of these roles would be compatible with marriage. (Though there’s another ultimate reason why she stays unmarried.)

A supporting character, her neighbour Harriet, offers a counterpoint or cautionary tale. She’s trapped in a marriage to an odious man she despises. “Because while she was stuck forever being Mrs. Sloane—she was a Catholic—she never wanted to turn into a Mr. Sloane.”

Almost all of the books we read for the club, whether contemporary or historical, present marriage in at least a somewhat negative light, or warn that there are many things that can go wrong…

See Kate’s, Kay’s and Naomi’s reviews, too!

Coming up next, in June: The Constant Wife by W. Somerset Maugham. This is the first play we’ve done and my first Maugham in a while, so I’m looking forward to it.

Nonfiction November Book Pairings: Autistic Husbands & The Ocean

Liz is the host for this week’s Nonfiction November prompt. The idea is to choose a nonfiction book and pair it with a fiction title with which it has something in common.

I came up with these two based on my recent reading:

An Autistic Husband

The Rosie Effect by Graeme Simsion (also The Rosie Project and The Rosie Result)

&

Disconnected: Portrait of a Neurodiverse Marriage by Eleanor Vincent

Graeme Simsion’s Don Tillman trilogy tells the odd-couple story of an autistic professor and how he falls in love with and marries a wholly unsuitable neurotypical woman. He turns this situation into romantic comedy. For Eleanor Vincent, it wasn’t so funny. She met her third husband, computer scientist Lars (a pseudonym), through Zydeco dancing when she was in her sixties. Though aware that he could be unemotional and act strangely, she found him chivalrous and sweet. They dated for a time but he hurt and confused her by asking for his apartment keys back. After a five-year period she calls their “Interregnum,” the two got back together and married. Despite their years of friendship, she was completely unprepared for what living with him would be like. “At the age of seventy-one, I had married a stranger,” she writes.

Graeme Simsion’s Don Tillman trilogy tells the odd-couple story of an autistic professor and how he falls in love with and marries a wholly unsuitable neurotypical woman. He turns this situation into romantic comedy. For Eleanor Vincent, it wasn’t so funny. She met her third husband, computer scientist Lars (a pseudonym), through Zydeco dancing when she was in her sixties. Though aware that he could be unemotional and act strangely, she found him chivalrous and sweet. They dated for a time but he hurt and confused her by asking for his apartment keys back. After a five-year period she calls their “Interregnum,” the two got back together and married. Despite their years of friendship, she was completely unprepared for what living with him would be like. “At the age of seventy-one, I had married a stranger,” she writes.

It didn’t help that Covid hit partway through their four-year marriage, nor that they each received a cancer diagnosis (cervical vs. prostate). But the problems were more with their everyday differences in responses and processing. During their courtship, she ignored some bizarre things he did around her family: he bit her nine-year-old granddaughter as a warning of what would happen if she kept antagonizing their cat, and he put a gift bag over his head while they were at the dinner table with her siblings. These are a couple of the most egregious instances, but there are examples throughout of how Lars did things she didn’t understand. Through support groups and marriage counselling, she realized how well Lars had masked his autism when they were dating – and that he wasn’t willing to do the work required to make their marriage succeed. The book ends with them estranged but a divorce imminent.

If this were purely carping about a husband’s weirdness, it might have been tedious or depressing. But Vincent doesn’t blame Lars, and she incorporates so much else in this short memoir, including a number of topics that are of particular interest to me. There’s her PTSD from a traumatic upbringing, her parents’ identity as closeted gay people, the complications around her father’s death, the tragedy of her older daughter’s death, as well as the more everyday matters of being a working single parent, finding an affordable property in California’s Bay Area, and blending households.

If this were purely carping about a husband’s weirdness, it might have been tedious or depressing. But Vincent doesn’t blame Lars, and she incorporates so much else in this short memoir, including a number of topics that are of particular interest to me. There’s her PTSD from a traumatic upbringing, her parents’ identity as closeted gay people, the complications around her father’s death, the tragedy of her older daughter’s death, as well as the more everyday matters of being a working single parent, finding an affordable property in California’s Bay Area, and blending households.

Vincent crafts engaging scenes with solid recreated dialogue, and I especially liked the few meta chapters revealing “What I Left Out” – a memoir is always a shaped narrative, while life is messy; this shows both. She is also honest about her own failings and occasional bad behavior. I probably could have done with a little less detail on their sex life, however.

This had more relevance to me than expected. While my sister and I were clearing our mother’s belongings from the home she shared with her second husband for the 16 months between their wedding and her death, our stepsisters mentioned to us that they suspected their father was autistic. It was, as my sister said, a “lightbulb” moment, explaining so much about our respective parents’ relationship, and our interactions with him as well. My stepfather (who died just 10 months after my mother) was a dear man, but also maddening at times. A retired math professor, he was logical and flat of affect. Sometimes his humor was off-kilter and he made snap, unsentimental decisions that we couldn’t fathom. Had they gotten longer together, no doubt many of the issues Vincent experienced would have arisen. (Read via BookSirens)

[173 pages]

The Ocean

Playground by Richard Powers

&

Rachel Carson and the Power of Queer Love by Lida Maxwell

The Blue Machine by Helen Czerski

Under the Sea Wind by Rachel Carson

While I was less than enraptured with its artificial intelligence theme and narrative trickery, I loved the content about the splendour of the ocean in Richard Powers’s Booker Prize-longlisted Playground. Most of this comes via Evelyne Beaulieu, a charismatic French Canadian marine biologist (based in part on Sylvia Earle) who is on the first all-female submarine mission and is still diving in the South Pacific in her nineties. Powers explicitly references Rachel Carson’s The Sea Around Us. Between that and the revelation of Evelyne as a late-bloomer lesbian, I was reminded of Rachel Carson and the Power of Queer Love, a forthcoming novella-length academic study by Lida Maxwell that I have assessed for Foreword Reviews. Maxwell’s central argument is that Carson’s romantic love for a married woman, Dorothy Freeman, served as an awakening to wonder and connection and spurred her to write her greatest works.

While I was less than enraptured with its artificial intelligence theme and narrative trickery, I loved the content about the splendour of the ocean in Richard Powers’s Booker Prize-longlisted Playground. Most of this comes via Evelyne Beaulieu, a charismatic French Canadian marine biologist (based in part on Sylvia Earle) who is on the first all-female submarine mission and is still diving in the South Pacific in her nineties. Powers explicitly references Rachel Carson’s The Sea Around Us. Between that and the revelation of Evelyne as a late-bloomer lesbian, I was reminded of Rachel Carson and the Power of Queer Love, a forthcoming novella-length academic study by Lida Maxwell that I have assessed for Foreword Reviews. Maxwell’s central argument is that Carson’s romantic love for a married woman, Dorothy Freeman, served as an awakening to wonder and connection and spurred her to write her greatest works.

After reading Playground, I decided to place a library hold on Blue Machine by Helen Czerski (winner of the Wainwright Writing on Conservation Prize this year), which Powers acknowledges as an inspiration that helped him to think bigger. I have also pulled my copy of Under the Sea Wind by Rachel Carson off the shelf as it’s high time I read more by her.

Previous book pairings posts: 2018 (Alzheimer’s, female friendship, drug addiction, Greenland and fine wine!) and 2023 (Hardy’s Wives, rituals and romcoms).

I’ve found Bloom’s short stories more successful than her novels. This is something of a halfway house: linked short stories (one of which was previously published in

I’ve found Bloom’s short stories more successful than her novels. This is something of a halfway house: linked short stories (one of which was previously published in  The title story opens a collection steeped in the landscape and history of Orkney. Each month we check in with three characters: Jean, who lives with her ailing father at the pub they run; and her two very different suitors, pious Peter and drunken Thorfinn. When she gives birth in December, you have to page back to see that she had encounters with both men in March. Some are playful in this vein or resemble folk tales: a boy playing hooky from school, a distant cousin so hapless as to father three bairns in the same household, and a rundown of the grades of whisky available on the islands. Others with medieval time markers are overwhelmingly bleak, especially “Witch,” about a woman’s trial and execution – and one of two stories set out like a play for voices. I quite liked the flash fiction “The Seller of Silk Shirts,” about a young Sikh man who arrives on the islands, and “The Story of Jorfel Hayforks,” in which a Norwegian man sails to find the man who impregnated his sister and keeps losing a crewman at each stop through improbable accidents. This is an atmospheric book I would have liked to read on location, but few of the individual stories stand out. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

The title story opens a collection steeped in the landscape and history of Orkney. Each month we check in with three characters: Jean, who lives with her ailing father at the pub they run; and her two very different suitors, pious Peter and drunken Thorfinn. When she gives birth in December, you have to page back to see that she had encounters with both men in March. Some are playful in this vein or resemble folk tales: a boy playing hooky from school, a distant cousin so hapless as to father three bairns in the same household, and a rundown of the grades of whisky available on the islands. Others with medieval time markers are overwhelmingly bleak, especially “Witch,” about a woman’s trial and execution – and one of two stories set out like a play for voices. I quite liked the flash fiction “The Seller of Silk Shirts,” about a young Sikh man who arrives on the islands, and “The Story of Jorfel Hayforks,” in which a Norwegian man sails to find the man who impregnated his sister and keeps losing a crewman at each stop through improbable accidents. This is an atmospheric book I would have liked to read on location, but few of the individual stories stand out. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)  Mantel is best remembered for the Wolf Hall trilogy, but her early work includes a number of concise, sharp novels about growing up in the north of England. Carmel McBain attends a Catholic school in Manchester in the 1960s before leaving to study law at the University of London in 1970. In lockstep with her are a couple of friends, including Karina, who is of indeterminate Eastern European extraction and whose tragic Holocaust family history, added to her enduring poverty, always made her an object of pity for Carmel’s mother. But Karina as depicted by Carmel is haughty, even manipulative, and over the years their relationship swings between care and competition. As university students they live on the same corridor and have diverging experiences of schoolwork, romance, and food. “Now, I would not want you to think that this is a story about anorexia,” Carmel says early on, and indeed, she presents her condition as more like forgetting to eat. But then you recall tiny moments from her past when teachers and her mother shamed her for eating, and it’s clear a seed was sown. Carmel and her friends also deal with the results of the new-ish free love era. This is dark but funny, too, with Carmel likening roast parsnips to “ogres’ penises.” Further proof, along with

Mantel is best remembered for the Wolf Hall trilogy, but her early work includes a number of concise, sharp novels about growing up in the north of England. Carmel McBain attends a Catholic school in Manchester in the 1960s before leaving to study law at the University of London in 1970. In lockstep with her are a couple of friends, including Karina, who is of indeterminate Eastern European extraction and whose tragic Holocaust family history, added to her enduring poverty, always made her an object of pity for Carmel’s mother. But Karina as depicted by Carmel is haughty, even manipulative, and over the years their relationship swings between care and competition. As university students they live on the same corridor and have diverging experiences of schoolwork, romance, and food. “Now, I would not want you to think that this is a story about anorexia,” Carmel says early on, and indeed, she presents her condition as more like forgetting to eat. But then you recall tiny moments from her past when teachers and her mother shamed her for eating, and it’s clear a seed was sown. Carmel and her friends also deal with the results of the new-ish free love era. This is dark but funny, too, with Carmel likening roast parsnips to “ogres’ penises.” Further proof, along with  Unexpected Lessons in Love by Bernardine Bishop (2013): I loved Bishop’s

Unexpected Lessons in Love by Bernardine Bishop (2013): I loved Bishop’s  A Rough Guide to the Heart by Pam Houston (1999): A mix of personal essays and short travel pieces. The material about her dysfunctional early family life, her chaotic dating, and her thrill-seeking adventures in the wilderness is reminiscent of the highly autobiographical

A Rough Guide to the Heart by Pam Houston (1999): A mix of personal essays and short travel pieces. The material about her dysfunctional early family life, her chaotic dating, and her thrill-seeking adventures in the wilderness is reminiscent of the highly autobiographical  The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier – A pleasant year’s diary of rural living and adjusting to her husband’s new diagnosis of neurodivergence.

The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier – A pleasant year’s diary of rural living and adjusting to her husband’s new diagnosis of neurodivergence.