Spring Reads, Part I: Violets and Rain

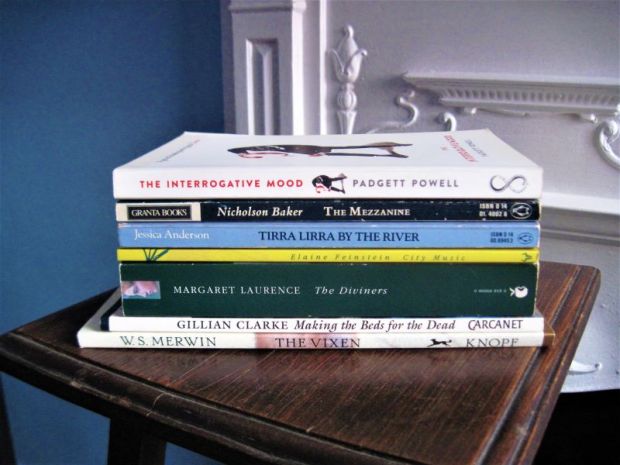

We had both rain and spring sunshine on a recent overnight trip to Bridport, Dorset – a return visit after enjoying it so much in 2019. Several elements were repeated: Dorset Nectar cider farm, dinner at Dorshi, and a bookshop and charity shop crawl of the main streets. While we didn’t revisit Thomas Hardy sites, I spent plenty of time at Max Gate by reading Elizabeth Lowry’s The Chosen. Beach walks plus one in the New Forest on the way back were splendid. This was my haul from Bridport Old Books. Stocking up on novellas and poetry, plus a novel by a Canadian author I’ve enjoyed work from before.

Now for a quick look at two tangentially spring-related books I’ve read recently: a short novel about two women’s wartime experiences of motherhood and an elegiac and allusive poetry collection.

Violets by Alex Hyde (2022)

I was intrigued by the sound of this debut novel, which juxtaposes the lives of two young British women named Violet at the close of the Second World War. One miscarries twins and, told she’ll not be able to bear children, has to rethink her whole future; another sails from Wales to Italy on ATS war service, hiding the fact that she’s pregnant by a departed foreign soldier. Hyde’s spare style – no speech marks; short paragraphs or solitary lines separated by spaces – alternates between their stories in brief numbered chapters, bringing them together in a perhaps predictable way that also forms a reimagining of her father’s life story. The narration at times addresses this future character in poems that I think are supposed to be fond and prophetic but I instead found strangely blunt and even taunting (as in the excerpt below). There’s inadequate time to get to know, or care about, either Violet.

Can you feel it, Pram Boy?

Can you march in time?

A change, a hardening,

the jarring of the solid ground as she treads,

gets her pockets picked.

[…]

Quick! March!

And your Mama, Pram Boy,

yeasty in her private parts.

Granta sent a free copy. Violets came out in paperback in February.

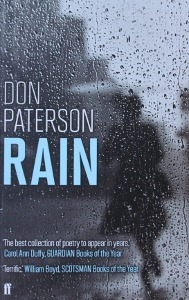

Rain by Don Paterson (Faber, 2009)

I’d previously read Paterson’s 40 Sonnets, in 2015. This collection is in memoriam of the late poet Michael Donaghy, the subject of the late multi-part “Phantom.” There are a couple of poems in Scots and a sequence of seven nature-infused ones designated as being “after” poets from Li Po to Robert Desnos. Several appear to express concern for a son. There’s a haiku-like rhythm to the short stanzas of “Renku: My Last Thirty-Five Deaths.” I didn’t understand why “Unfold i.m. Akira Yoshizawa” was a blank page until I looked him up and learned that he was a famous origamist. The title poem closes the collection:

I’d previously read Paterson’s 40 Sonnets, in 2015. This collection is in memoriam of the late poet Michael Donaghy, the subject of the late multi-part “Phantom.” There are a couple of poems in Scots and a sequence of seven nature-infused ones designated as being “after” poets from Li Po to Robert Desnos. Several appear to express concern for a son. There’s a haiku-like rhythm to the short stanzas of “Renku: My Last Thirty-Five Deaths.” I didn’t understand why “Unfold i.m. Akira Yoshizawa” was a blank page until I looked him up and learned that he was a famous origamist. The title poem closes the collection:

I love all films that start with rain:

rain, braiding a windowpane

or darkening a hung-out dress

or streaming down her upturned face;

one big thundering downpour

right through the empty script and score

before the act, before the blame,

before the lens pulls through the frame

to where the woman sits alone

beside a silent telephone

I liked individual passages or images but didn’t find much of a connecting theme behind Paterson’s disparate interests. (University library)

Another favourite passage:

So I collect the dull things of the day

in which I see some possibility

[…]

I look at them and look at them until

one thing makes a mirror in my eyes

then I paint it with the tear to make it bright.

This is why I sit up through the night.

(from “Why Do You Stay Up So Late?”)

And a DNF:

Corpse Beneath the Crocus by N.N. Nelson – I loved the title and the cover, and a widow’s bereavement memoir in poems seemed right up my street. I wish I’d realized Atmosphere is a vanity press, which would explain why these are among the worst poems I’ve read: cliché-riddled and full of obvious sentiments and metaphors as she explores specific moments but mostly overall emotions. Three excerpts:

Corpse Beneath the Crocus by N.N. Nelson – I loved the title and the cover, and a widow’s bereavement memoir in poems seemed right up my street. I wish I’d realized Atmosphere is a vanity press, which would explain why these are among the worst poems I’ve read: cliché-riddled and full of obvious sentiments and metaphors as she explores specific moments but mostly overall emotions. Three excerpts:

All things die

In the flowering cycle

Of growth and life

Time passes

Like sand in an hourglass

Feelings are changeful

Like the tide

Ebbing and flowing

“Love Letter,” a prose piece, held the most promise, which suggests Nelson would have been better off attempting memoir. I slogged (hate-read, really) my way through to the halfway point but could bear it no longer. (NetGalley)

I have a few more spring-themed books on the go: Hoping for a better set next time!

Any spring reads on your plate?

Three on a Theme: Novels of Female Friendship

Friendship is a fairly common theme in my reading and, like sisterhood, it’s an element I can rarely resist. When I picked up a secondhand copy of Female Friends (below) in a charity shop in Hexham over the summer, I spied a chance for another thematic roundup. I limited myself to novels I’d read recently and to groups of women friends.

Before Everything by Victoria Redel (2017)

I found out about this one from Susan’s review at A life in books (and she included it in her own thematic roundup of novels on friendship). “The Old Friends” have known each other for decades, since elementary school. Anna, Caroline, Helen, Ming and Molly. Their lives have gone in different directions – painter, psychiatrist, singer in a rock band and so on – but in March 2013 they’re huddling together because Anna is terminally ill. Over the years she’s had four remissions, but it’s clear the lymphoma won’t go away this time. Some of Anna’s friends and family want her to keep fighting, but the core group of pals is going to have to learn to let her die on her own terms. Before that, though, they aim for one more adventure.

I found out about this one from Susan’s review at A life in books (and she included it in her own thematic roundup of novels on friendship). “The Old Friends” have known each other for decades, since elementary school. Anna, Caroline, Helen, Ming and Molly. Their lives have gone in different directions – painter, psychiatrist, singer in a rock band and so on – but in March 2013 they’re huddling together because Anna is terminally ill. Over the years she’s had four remissions, but it’s clear the lymphoma won’t go away this time. Some of Anna’s friends and family want her to keep fighting, but the core group of pals is going to have to learn to let her die on her own terms. Before that, though, they aim for one more adventure.

Through the short, titled sections, some of them pages in length but others only a sentence or two, you piece together the friends’ history and separate struggles. Here’s an example of one such fragment, striking for the frankness and intimacy; how coyly those bald numbers conceal such joyful and wrenching moments:

Actually, for What It’s Worth

Between them there were twelve delivered babies. Three six- to eight-week abortions. Three miscarriages. One post-amniocentesis selective abortion. That’s just for the record.

While I didn’t like this quite as much as Talk Before Sleep by Elizabeth Berg, which is similar in setup, it’s a must-read on the theme. It’s sweet and sombre by turns, and has bite. I also appreciated how Redel contrasts the love between old friends with marital love and the companionship of new neighbourly friends. I hadn’t heard of Redel before, but she’s published another four novels and three poetry collections. It’d be worth finding more by her. The cover image is inspired by a moment late in a book when they find a photograph of the five of them doing handstands in a sprinkler the summer before seventh grade. (Public library)

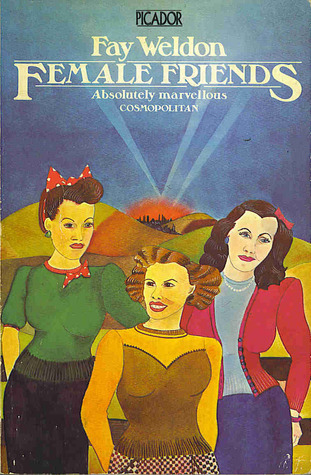

Female Friends by Fay Weldon (1974)

Like a cross between The Orchard on Fire by Shena Mackay and The Pumpkin Eater by Penelope Mortimer; this is the darkly funny story of Marjorie, Chloe and Grace: three Londoners who have stayed friends ever since their turbulent childhood during the Second World War, when Marjorie was sent to live with Grace and her mother. They have a nebulous brood of children between them, some fathered by a shared lover (a slovenly painter named Patrick). Chloe’s husband is trying to make her jealous with his sexual attentions to their French nanny. Marjorie, who works for the BBC, is the only one without children; she has a gynaecological condition and is engaged in a desultory search for her father.

Like a cross between The Orchard on Fire by Shena Mackay and The Pumpkin Eater by Penelope Mortimer; this is the darkly funny story of Marjorie, Chloe and Grace: three Londoners who have stayed friends ever since their turbulent childhood during the Second World War, when Marjorie was sent to live with Grace and her mother. They have a nebulous brood of children between them, some fathered by a shared lover (a slovenly painter named Patrick). Chloe’s husband is trying to make her jealous with his sexual attentions to their French nanny. Marjorie, who works for the BBC, is the only one without children; she has a gynaecological condition and is engaged in a desultory search for her father.

The book is mostly in the third person, but some chapters are voiced by Chloe and occasional dialogues are set out like a film script. I enjoyed the glimpses I got into women’s lives in the mid-20th century via the three protagonists and their mothers. All are more beholden to men than they’d like to be. But there’s an overall grimness to this short novel that left me wincing. I’d expected more nostalgia (“they are nostalgic, all the same, for those days of innocence and growth and noise. The post-war world is drab and grey and middle-aged. No excitement, only shortages and work”) and warmth, but this friendship trio is characterized by jealousy and resentment. (Secondhand copy)

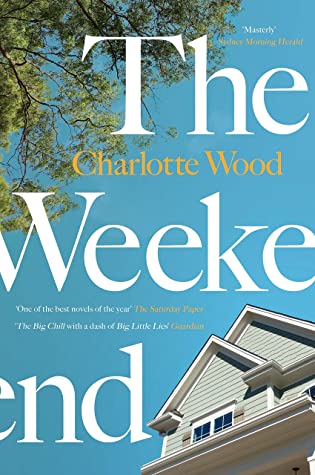

The Weekend by Charlotte Wood (2019)

“It was exhausting, being friends. Had they ever been able to tell each other the truth?”

It’s the day before Christmas Eve as seventysomethings Jude, Wendy and Adele gather to clear out their late friend’s Sylvie’s house in a fictional coastal town in New South Wales. This being Australia, that means blazing hot weather and a beach barbecue rather than a cosy winter scene. Jude is a bristly former restaurateur who has been the mistress of a married man for many years. Wendy is a widowed academic who brings her decrepit dog, Finn, along with her. Adele is a washed-up actress who carefully maintains her appearance but still can’t find meaningful work.

It’s the day before Christmas Eve as seventysomethings Jude, Wendy and Adele gather to clear out their late friend’s Sylvie’s house in a fictional coastal town in New South Wales. This being Australia, that means blazing hot weather and a beach barbecue rather than a cosy winter scene. Jude is a bristly former restaurateur who has been the mistress of a married man for many years. Wendy is a widowed academic who brings her decrepit dog, Finn, along with her. Adele is a washed-up actress who carefully maintains her appearance but still can’t find meaningful work.

They know each other so well, faults and all. Things they think they’ve hidden are beyond obvious to the others. And for as much as they miss Sylvie, they are angry at her, too. But there is also a fierce affection in the mix that I didn’t sense in the Weldon: “[Adele] remembered them from long ago, two girls alive with purpose and beauty. Her love for them was inexplicable. It was almost bodily.” Yet Wendy compares their tenuous friendship to the Great Barrier Reef coral, at risk of being bleached.

It’s rare to see so concerted a look at women in later life, as the characters think back and wonder if they’ve made the right choices. There are plenty of secrets and self-esteem struggles, but it’s all encased in an acerbic wit that reminded me of Emma Straub and Elizabeth Strout. Terrific stuff. (Twitter giveaway win)

Some favourite lines:

“The past was striated through you, through your body, leaching into the present and the future.”

“Was this what getting old was made of? Routines and evasions, boring yourself to death with your own rigid judgements?”

On this theme, I have also read: The Other’s Gold by Elizabeth Ames, Catch the Rabbit by Lana Bastašić, The Group by Lara Feigel (and Mary McCarthy), My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante, Expectation by Anna Hope, Conversations with Friends by Sally Rooney, and The Animators by Kayla Rae Whitaker.

If you read just one … The Weekend was the best of this bunch for me.

Have you read much on this topic?

Local Resistance: On Gallows Down by Nicola Chester

It’s mostly by accident that we came to live in Newbury: five years ago, when a previous landlord served us notice, we viewed a couple of rental houses in the area to compare with what was available in Reading and discovered that our money got us more that little bit further out from London. We’ve come to love this part of West Berkshire and the community we’ve found. It may not be flashy or particularly famous, but it has natural wonders worth celebrating and a rich history of rebellion that Nicola Chester plumbs in On Gallows Down. A hymn-like memoir of place as much as of one person’s life, her book posits that the quiet moments of connection with nature and the rights of ordinary people are worth fighting for.

So many layers of history mingle here: from the English Civil War onward, Newbury has been a locus of resistance for centuries. Nicola* has personal memories of the long-running women’s peace camps at Greenham Common, once a U.S. military base and cruise missile storage site – to go with the Atomic Weapons Establishment down the road at Aldermaston. As a teenager and young woman, she took part in symbolic protests against the Twyford Down and Newbury Bypass road-building projects, which went ahead and destroyed much sensitive habitat and many thousands of trees. Today, through local and national newspaper and magazine columns on wildlife, and through her winsome nagging of the managers of the Estate she lives on, she bears witness to damaging countryside management and points to a better way.

While there is a loose chronological through line, the book is principally arranged by theme, with experiences linked back to historical or literary precedents. An account of John Clare and the history of enclosure undergirds her feeling of the precarity of rural working-class life: as an Estate tenant, she knows she doesn’t own anything, has no real say in how things are done, and couldn’t afford to move elsewhere. Nicola is a school librarian and has always turned to books and writing to understand the world. I particularly loved Chapter 6, about how she grounds herself via the literature of this area: Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, Adam Thorpe’s Ulverton, and especially Richard Adams’s Watership Down.

Whatever life throws at her – her husband being called up to fight in Iraq, struggling to make ends meet with small children, a miscarriage, her father’s unexpected death – nature is her solace. She describes places and creatures with a rare intimacy borne out of deep knowledge. To research a book on otters for the RSPB, she seeks out every bridge over every stream. She goes out “lamping” with the local gamekeeper after dark and garners priceless nighttime sightings. Passing on her passion to her children, she gets them excited about badger watching, fossil collecting, and curating shelves of natural history treasures like skulls and feathers. She also serves as a voluntary wildlife advocate on her Estate. For every victory, like the re-establishment of the red kite population in Berkshire and regained public access to Greenham Common, there are multiple setbacks, but she continues to be a hopeful activist, her lyrical writing a means of defiance.

We are writing for our very lives and for those wild lives we share this one, lonely planet with. Writing was also a way to channel the wildness; to investigate and interpret it, to give it a voice and defend it. But it was also a connection between home and action; a plank bridge between a domestic and wild sense. A way both to home and resist.

You know that moment when you’re reading a book and spot a place you’ve been or a landmark you know well, and give a little cheer? Well, every site in this book was familiar to me from our daily lives and countryside wanderings – what a treat! As I was reading, I kept thinking how lucky we are to have such an accomplished nature writer to commemorate the uniqueness of this area. Even though I was born thousands of miles away and have moved more than a dozen times since I settled in England in 2007, I feel the same sense of belonging that Nicola attests to. She explicitly addresses this question of where we ‘come from’ versus where we fit in, and concludes that nature is always the key. There is no exclusion here. “Anyone could make a place their home by engaging with its nature.”

*I normally refer to the author by surname in a book review, but I’m friendly with Nicola from Twitter and have met her several times (and she’s one of the loveliest people you’ll ever meet), so somehow can’t bring myself to be that detached!

On Gallows Down was released by Chelsea Green Publishing on October 7th. My thanks to the author and publisher for arranging a proof copy for review.

My husband and I attended the book launch event for On Gallows Down in Hungerford on Saturday evening. Nicola was introduced by Hungerford Bookshop owner Emma Milne-White and interviewed by Claire Fuller, whose Women’s Prize-shortlisted novel Unsettled Ground is set in a fictional version of the village where Nicola lives.

Nicola Chester and Claire Fuller. Photo by Chris Foster.

Nicola dated the book’s genesis to the moment when, 25 years ago, she queued up to talk to a TV news reporter about Newbury Bypass and froze. She went home and cried, and realized she’d have to write her feelings down instead. Words generally come to her at the time of a sighting, as she thinks about how she would tell someone how amazing it was.

Her memories are tied up with seasons and language, especially poetry, she said, and she has recently tried her hand at poetry herself. Asked about her favourite season, she chose two, the in-between seasons – spring for its abundance and autumn for its nostalgia and distinctive smells like tar spot fungus on sycamore leaves and ivy flowers.

A bonus related read:

Anarchipelago by Jay Griffiths (2007)

This limited edition 57-page pamphlet from Glastonbury-based Wooden Books caught my eye from the library’s backroom rolling stacks. Griffiths wrote her impish story of Newbury Bypass resistance in response to her time among the protesters’ encampments and treehouses. Young Roddy finds a purpose for his rebellious attitude wider than his “McTypical McSuburb” by joining other oddballs in solidarity against aggressive policemen and detectives.

There are echoes of Ali Smith in the wordplay and rendering of accents.

“When I think of the road, I think of more and more monoculture of more and more suburbia. What I do, I do in defiance of the Louis Queasy Chintzy, the sickly stale air of suburban car culture. I want the fresh air of nature, the lifefull wind of the French revolution.”

In a nice spot of Book Serendipity, both this and On Gallows Down recount the moment when nature ‘fought back’ as a tree fell on a police cherry-picker. Plus Roddy is kin to the tree-sitting protesters in The Overstory by Richard Powers as well as another big novel I’m reading now, Damnation Spring by Ash Davidson.

Three on a Theme: Queer Family-Making

Several 2021 memoirs have given me a deeper understanding of the special challenges involved when queer couples decide they want to have children.

“It’s a fundamentally queer principle to build a family out of the pieces you have”

~Jennifer Berney

“That’s the thing[:] there are no accidental children born to homosexuals – these babies are always planned for, and always wanted.”

~Michael Johnson-Ellis

The Other Mothers by Jennifer Berney

Berney remembers hearing the term “test-tube baby” for the first time in a fifth-grade sex ed class taught by a lesbian teacher at her Quaker school. By that time she already had an inkling of her sexuality, so suspected that she might one day require fertility help herself.

By the time she met her partner, Kellie, she knew she wanted to be a mother; Kellie was unsure. Once they were finally on the same page, it wasn’t an easy road to motherhood. They purchased donated sperm through a fertility clinic and tried IUI, but multiple expensive attempts failed. Signs of endometriosis had doctors ready to perform invasive surgery, but in the meantime the couple had met a friend of a friend (Daniel, whose partner was Rebecca) who was prepared to be their donor. Their at-home inseminations resulted in a pregnancy – after two years of trying to conceive – and, ultimately, in their son. Three years later, they did the whole thing all over again. Rebecca had sons at roughly the same time, too, giving their boys the equivalent of same-age cousins – a lovely, unconventional extended family.

By the time she met her partner, Kellie, she knew she wanted to be a mother; Kellie was unsure. Once they were finally on the same page, it wasn’t an easy road to motherhood. They purchased donated sperm through a fertility clinic and tried IUI, but multiple expensive attempts failed. Signs of endometriosis had doctors ready to perform invasive surgery, but in the meantime the couple had met a friend of a friend (Daniel, whose partner was Rebecca) who was prepared to be their donor. Their at-home inseminations resulted in a pregnancy – after two years of trying to conceive – and, ultimately, in their son. Three years later, they did the whole thing all over again. Rebecca had sons at roughly the same time, too, giving their boys the equivalent of same-age cousins – a lovely, unconventional extended family.

It surprised me that the infertility business seemed entirely set up for heterosexual couples – so much so that a doctor diagnosed the problem, completely seriously, in Berney’s chart as “Male Factor Infertility.” This was in Washington state in c. 2008, before the countrywide legalization of gay marriage, so it’s possible the situation would be different now, or that the couple would have had a different experience had they been based somewhere like San Francisco where there is a wide support network and many gay-friendly resources.

Berney finds the joy and absurdity in their journey as well as the many setbacks. I warmed to the book as it went along: early on, it dragged a bit as she surveyed her younger years and traced the history of IVF and alternatives like international adoption. As the storyline drew closer to the present day, there was more detail and tenderness and I was more engaged. I’d read more from this author. (Published by Sourcebooks. Read via NetGalley)

small: on motherhoods by Claire Lynch

A line from Berney’s memoir makes a good transition into this one: “I felt a sense of dread: if I turned out to be gay I believed my life would become unbearably small.” The word “small” is a sort of totem here, a reminder of the microscopic processes and everyday miracles that go into making babies, as well as of the vulnerability of newborns – and of hope.

Lynch and her partner Beth’s experience in England was reminiscent of Berney’s in many ways, but with a key difference: through IVF, Lynch’s eggs were added to donor sperm to make the embryos implanted in Beth’s uterus. Mummy would have the genetic link, Mama the physical tie of carrying and birthing. It took more than three years of infertility treatment before they conceived their twin girls, born premature; they were followed by another daughter, creating a crazy but delightful female quintet. The account of the time when their daughters were in incubators reminded me of Francesca Segal’s Mother Ship.

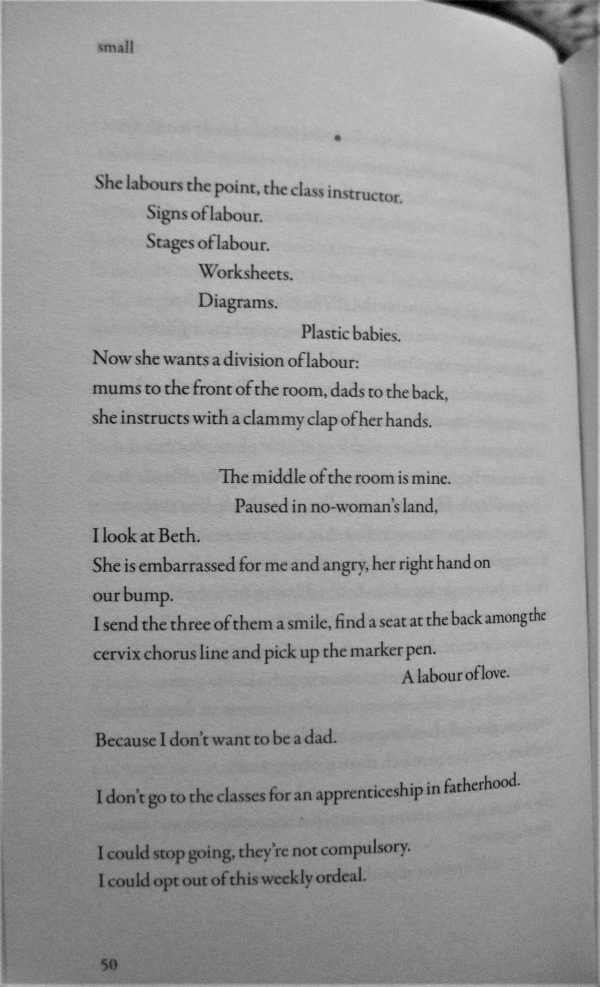

There are two intriguing structural choices that make small stand out. The first you’d notice from opening the book at random, or to page 1. It is written in a hybrid form, the phrases and sentences laid out more like poetry. Although there are some traditional expository paragraphs, more often the words are in stanzas or indented. Here’s an example of what this looks like on the page. It also happens to be from one of the most ironically funny parts of the book, when Lynch is grouped in with the dads at an antenatal class:

It’s a fast-flowing, artful style that may remind readers of Bernardine Evaristo’s work (and indeed, Evaristo gives one of the puffs). The second interesting decision was to make the book turn on a revelation: at the exact halfway mark we learn that, initially, the couple intended to have opposite roles: Lynch tried to get pregnant with Beth’s baby, but miscarried. Making this the pivot point of the memoir emphasizes the struggle and grief of this experience, even though we know that it had a happy ending.

With thanks to Brazen Books for the free copy for review.

How We Do Family by Trystan Reese

We mostly have Trystan Reese to thank for the existence of a pregnant man emoji. A community organizer who works on anti-racist and LGBTQ justice campaigns, Reese is a trans man married to a man named Biff. They expanded their family in two unexpected ways: first by adopting Biff’s niece and nephew when his sister’s situation of poverty and drug abuse meant she couldn’t take care of them, and then by getting pregnant in the natural (is that even the appropriate word?) way.

All along, Reese sought to be transparent about the journey, with a crowdfunding project and podcast ahead of the adoption, and media coverage of the pregnancy. This opened the family up to a lot of online hatred. I found myself most interested in the account of the pregnancy itself, and how it might have healed or exacerbated a sense of bodily trauma. Reese was careful to have only in-the-know and affirming people in the delivery room so there would be no surprises for anyone. His doctor was such an ally that he offered to create a more gender-affirming C-section scar (vertical rather than horizontal) if it came to it. How to maintain a sense of male identity while giving birth? Well, Reese told Biff not to look at his crotch during the delivery, and decided not to breastfeed.

All along, Reese sought to be transparent about the journey, with a crowdfunding project and podcast ahead of the adoption, and media coverage of the pregnancy. This opened the family up to a lot of online hatred. I found myself most interested in the account of the pregnancy itself, and how it might have healed or exacerbated a sense of bodily trauma. Reese was careful to have only in-the-know and affirming people in the delivery room so there would be no surprises for anyone. His doctor was such an ally that he offered to create a more gender-affirming C-section scar (vertical rather than horizontal) if it came to it. How to maintain a sense of male identity while giving birth? Well, Reese told Biff not to look at his crotch during the delivery, and decided not to breastfeed.

I realized when reading this and Detransition, Baby that my view of trans people is mostly post-op because of the only trans person I know personally, but a lot of people choose never to get surgical confirmation of gender (or maybe surgery is more common among trans women?). We’ve got to get past the obsession with genitals. As Reese writes, “we are just loving humans, like every human throughout all of time, who have brought a new life into this world. Nothing more than that, and nothing less. Just humans.”

This is a very fluid, quick read that recreates scenes and conversations with aplomb, and there are self-help sections after most chapters about how to be flexible and have productive dialogue within a family and with strangers. If literary prose and academic-level engagement with the issues are what you’re after, you’d want to head to Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts instead, but I also appreciated Reese’s unpretentious firsthand view.

And here’s further evidence of my own bias: the whole time I was reading, I felt sure that Reese must be the figure on the right with reddish hair, since that looked like a person who could once have been a woman. But when I finished reading I looked up photos; there are many online of Reese during pregnancy. And NOPE, he is the bearded, black-haired one! That’ll teach me to make assumptions. (Published by The Experiment. Read via NetGalley)

Plus a bonus essay from the Music.Football.Fatherhood anthology, DAD:

“A Journey to Gay Fatherhood: Surrogacy – The Unimaginable, Manageable” by Michael Johnson-Ellis

The author and his husband Wes had both previously been married to women before they came out. Wes already had a daughter, so they decided Johnson-Ellis would be the genetic father the first time. They then had different egg donors for their two children, but used the same surrogate for both pregnancies. I was astounded at the costs involved: £32,000 just to bring their daughter into being. And it’s striking both how underground the surrogacy process is (in the UK it’s illegal to advertise for a surrogate) and how exclusionary systems are – the couple had to fight to be in the room when their surrogate gave birth, and had to go to court to be named the legal guardians when their daughter was six weeks old. Since then, they’ve given testimony at the Houses of Parliament and become advocates for UK surrogacy.

The author and his husband Wes had both previously been married to women before they came out. Wes already had a daughter, so they decided Johnson-Ellis would be the genetic father the first time. They then had different egg donors for their two children, but used the same surrogate for both pregnancies. I was astounded at the costs involved: £32,000 just to bring their daughter into being. And it’s striking both how underground the surrogacy process is (in the UK it’s illegal to advertise for a surrogate) and how exclusionary systems are – the couple had to fight to be in the room when their surrogate gave birth, and had to go to court to be named the legal guardians when their daughter was six weeks old. Since then, they’ve given testimony at the Houses of Parliament and become advocates for UK surrogacy.

(I have a high school acquaintance who has gone down this route with his husband – they’re about to meet their daughter and already have a two-year-old son – so I was curious to know more about it, even though their process in the USA might be subtly different.)

On the subject of queer family-making, I have also read: The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson ( ) and The Fixed Stars by Molly Wizenberg (

) and The Fixed Stars by Molly Wizenberg ( ).

).

If you read just one … Claire Lynch’s small was the one I enjoyed most as a literary product, but if you want to learn more about the options and process you might opt for Jennifer Berney’s The Other Mothers; if you’re particularly keen to explore trans issues and LGTBQ activism, head to Trystan Reese’s How We Do Family.

Have you read anything on this topic?

Review Book Catch-Up: Motherhood, Nature Essays, Pandemic, Poetry

July slipped away without me managing to review any current-month releases, as I am wont to do, so to those three I’m adding in a couple of other belated review books to make up today’s roundup. I have: a memoir-cum-sociological study of motherhood, poems of Afghan women’s experiences, a graphic novel about a fictional worst-case pandemic, seasonal nature essays from voices not often heard, and poetry about homosexual encounters.

(M)otherhood: On the choices of being a woman by Pragya Agarwal

“Mothering would be my biggest gesture of defiance.”

Growing up in India, Agarwal, now a behavioural and data scientist, wished she could be a boy for her father’s sake. Being the third daughter was no place of honour in society’s eyes, but her parents ensured that she got a good education and expected her to achieve great things. Still, when she got her first period, it felt like being forced onto a fertility track she didn’t want. There was a dearth of helpful sex education, and Hinduism has prohibitions that appear to diminish women, e.g. menstruating females aren’t permitted to enter a temple.

Growing up in India, Agarwal, now a behavioural and data scientist, wished she could be a boy for her father’s sake. Being the third daughter was no place of honour in society’s eyes, but her parents ensured that she got a good education and expected her to achieve great things. Still, when she got her first period, it felt like being forced onto a fertility track she didn’t want. There was a dearth of helpful sex education, and Hinduism has prohibitions that appear to diminish women, e.g. menstruating females aren’t permitted to enter a temple.

Married and unexpectedly pregnant in 1996, Agarwal determined to raise her daughter differently. Her mother-in-law was deeply disappointed that the baby was a girl, which only increased her stubborn pride: “Giving birth to my daughter felt like first love, my only love. Not planned but wanted all along. … Me and her against the world.” No element of becoming a mother or of her later life lived up to her expectations, but each apparent failure gave a chance to explore the spectrum of women’s experiences: C-section birth, abortion, divorce, emigration, infertility treatment, and finally having further children via a surrogate.

While I enjoyed the surprising sweep of Agarwal’s life story, this is no straightforward memoir. It aims to be an exhaustive survey of women’s life choices and the cultural forces that guide or constrain them. The book is dense with history and statistics, veers between topics, and needed a better edit for vernacular English and smoothing out academic jargon. I also found that I wasn’t interested enough in the specifics of women’s lives in India.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

Forty Names by Parwana Fayyaz

“History has ungraciously failed the women of my family”

Have a look at this debut poet’s journey: Fayyaz was born in Kabul in 1990, grew up in Afghanistan and Pakistan, studied in Bangladesh and at Stanford, and is now, having completed her PhD, a research fellow at Cambridge. Many of her poems tell family stories that have taken on the air of legend due to the translated nicknames: “Patience Flower,” her grandmother, was seduced by the Khan and bore him two children; “Quietude,” her aunt, was a refugee in Iran. Her cousin, “Perfect Woman,” was due to be sent away from the family for infertility but gained revenge and independence in her own way.

Have a look at this debut poet’s journey: Fayyaz was born in Kabul in 1990, grew up in Afghanistan and Pakistan, studied in Bangladesh and at Stanford, and is now, having completed her PhD, a research fellow at Cambridge. Many of her poems tell family stories that have taken on the air of legend due to the translated nicknames: “Patience Flower,” her grandmother, was seduced by the Khan and bore him two children; “Quietude,” her aunt, was a refugee in Iran. Her cousin, “Perfect Woman,” was due to be sent away from the family for infertility but gained revenge and independence in her own way.

Fayyaz is bold to speak out about the injustices women can suffer in Afghan culture. Domestic violence is rife; miscarriage is considered a disgrace. In “Roqeeya,” she remembers that her mother, even when busy managing a household, always took time for herself and encouraged Parwana, her eldest, to pursue an education and earn her own income. However, the poet also honours the wisdom and skills that her illiterate mother exhibited, as in the first three poems about the care she took over making dresses and dolls for her three daughters.

As in Agarwal’s book, there is a lot here about ideals of femininity and the different routes that women take – whether more or less conventional. “Reading Nadia with Eavan” was a favourite for how it brought together different aspects of Fayyaz’s experience. Nadia Anjuman, an Afghan poet, was killed by her husband in 2005; many years later, Fayyaz found herself studying Anjuman’s work at Cambridge with the late Eavan Boland. Important as its themes are, I thought the book slightly repetitive and unsubtle, and noted few lines or turns of phrase – always a must for me when assessing a poetry collection.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

Resistance by Val McDermid; illus. Kathryn Briggs

The second 2021 release I read in quick succession in which all but a small percentage of the human race (here, 2 million people) perishes in a pandemic – the other was Under the Blue. Like Aristide’s novel, this story had its origins in 2017 (in this case, on BBC Radio 4’s “Dangerous Visions”) but has, of course, taken on newfound significance in the time of Covid-19. McDermid imagines the sickness taking hold during a fictional version of Glastonbury: Solstice Festival in Northumberland. All the first patients, including a handful of rockstars, ate from Sam’s sausage sandwich van, so initially it looks like food poisoning. But vomiting and diarrhoea give way to a nasty rash, listlessness and, in many cases, death.

The second 2021 release I read in quick succession in which all but a small percentage of the human race (here, 2 million people) perishes in a pandemic – the other was Under the Blue. Like Aristide’s novel, this story had its origins in 2017 (in this case, on BBC Radio 4’s “Dangerous Visions”) but has, of course, taken on newfound significance in the time of Covid-19. McDermid imagines the sickness taking hold during a fictional version of Glastonbury: Solstice Festival in Northumberland. All the first patients, including a handful of rockstars, ate from Sam’s sausage sandwich van, so initially it looks like food poisoning. But vomiting and diarrhoea give way to a nasty rash, listlessness and, in many cases, death.

Zoe Beck, a Black freelance journalist who conducted interviews at Solstice, is friends with Sam and starts investigating the mutated swine disease, caused by an Erysipelas bacterium and thus nicknamed “the Sips.” She talks to the festival doctor and to a female Muslim researcher from the Life Sciences Centre in Newcastle, but her search for answers takes a backseat to survival when her husband and sons fall ill.

The drawing style and image quality – some panes are blurry, as if badly photocopied – let an otherwise reasonably gripping story down; the best spreads are collages or borrow a frame/backdrop (e.g. a medieval manuscript, NHS forms, or a 1910s title page).

SPOILER

{The ending, which has an immune remnant founding a new community, is VERY Parable of the Sower.}

With thanks to Profile Books/Wellcome Collection for the free copy for review.

Gifts of Gravity and Light: A Nature Almanac for the 21st Century, ed. Anita Roy and Pippa Marland

I hadn’t heard about this upcoming nature anthology when a surprise copy dropped through my letterbox. I’m delighted the publisher thought of me, as this ended up being just my sort of book: 12 autobiographical essays infused with musings on landscapes in Britain and elsewhere; structured by the seasons to create a gentle progression through the year, starting with the spring. Best of all, the contributors are mostly female, BIPOC (and Romany), working class and/or queer – all told, the sort of voices that are heard far too infrequently in UK nature writing. In momentous rites of passage, as in routine days, nature plays a big role.

A few of my favourite pieces were by Kaliane Bradley, about her Cambodian heritage (the Wishing Dance associated with cherry blossom, her ancestors lost to genocide, the Buddhist belief that people can be reincarnated in other species); Testament, a rapper based in Leeds, about capturing moments through photography and poetry and about the seasons feeling awry both now and in March 2008, when snow was swirling outside the bus window as he received word of his uni friend’s untimely death; and Tishani Doshi, comparing childhood summers of freedom in Wales with growing up in India and 2020’s Covid restrictions.

A few of my favourite pieces were by Kaliane Bradley, about her Cambodian heritage (the Wishing Dance associated with cherry blossom, her ancestors lost to genocide, the Buddhist belief that people can be reincarnated in other species); Testament, a rapper based in Leeds, about capturing moments through photography and poetry and about the seasons feeling awry both now and in March 2008, when snow was swirling outside the bus window as he received word of his uni friend’s untimely death; and Tishani Doshi, comparing childhood summers of freedom in Wales with growing up in India and 2020’s Covid restrictions.

Most of the authors hold two places in mind at the same time: for Michael Malay, it’s Indonesia, where he grew up, and the Severn estuary, where he now lives and ponders eels’ journeys; for Zakiya McKenzie, it’s Jamaica and England; for editor Anita Roy, it’s Delhi versus the Somerset field her friend let her wander during lockdown. Trees lend an awareness of time and animals a sense of movement and individuality. Alys Fowler thinks of how the wood she secretly coppices and lays on park paths to combat the mud will long outlive her, disintegrating until it forms the very soil under future generations’ feet.

A favourite passage (from Bradley): “When nature is the cuddly bunny and the friendly old hill, it becomes too easy to dismiss it as a faithful retainer who will never retire. But nature is the panic at the end of a talon, and it’s the tree with a heart of fire where lightning has struck. It is not our friend, and we do not want to make it our enemy.”

Also featured: Bernardine Evaristo (foreword), Raine Geoghegan, Jay Griffiths, Amanda Thomson, and Luke Turner.

With thanks to Hodder & Stoughton for the free copy for review.

Records of an Incitement to Silence by Gregory Woods

Woods is an emeritus professor at Nottingham Trent University, where he was appointed the UK’s first professor of Gay & Lesbian Studies in 1998. Much of his sixth poetry collection is composed of unrhymed sonnets in two stanzas (eight lines, then six). The narrator is often a randy flâneur, wandering a city for homosexual encounters. One assumes this is Woods, except where the voice is identified otherwise, as in “[Walt] Whitman at Timber Creek” (“He gives me leave to roam / my idle way across / his prairies, peaks and canyons, my own America”) and “No Title Yet,” a long, ribald verse about a visitor to a stately home.

Woods is an emeritus professor at Nottingham Trent University, where he was appointed the UK’s first professor of Gay & Lesbian Studies in 1998. Much of his sixth poetry collection is composed of unrhymed sonnets in two stanzas (eight lines, then six). The narrator is often a randy flâneur, wandering a city for homosexual encounters. One assumes this is Woods, except where the voice is identified otherwise, as in “[Walt] Whitman at Timber Creek” (“He gives me leave to roam / my idle way across / his prairies, peaks and canyons, my own America”) and “No Title Yet,” a long, ribald verse about a visitor to a stately home.

Other times the perspective is omniscient, painting a character study, like “Company” (“When he goes home to bed / he dare not go alone. … This need / of company defeats him.”), or of Frank O’Hara in “Up” (“‘What’s up?’ Frank answers with / his most unseemly grin, / ‘The sun, the Dow, my dick,’ / and saunters back to bed.”). Formalists are sure to enjoy Woods’ use of form, rhyme and meter. I enjoyed some of the book’s cheeky moments but had trouble connecting with its overall tone and content. That meant that it felt endless. I also found the end rhymes, when they did appear, over-the-top and silly (Demeter/teeter, etc.).

Two favourite poems: “An Immigrant” (“He turned away / to strip. His anecdotes / were innocent and his / erection smelled of soap.”) and “A Knot,” written for friends’ wedding in 2014 (“make this wedding supper all the sweeter / With choirs of LGBT cherubim”).

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

Would you be interested in reading one or more of these?

Recommended March Releases: Broder, Fuller, Lamott, Polzin

Three novels that range in tone from carnal allegorical excess to quiet, bittersweet reflection via low-key menace; and essays about keeping the faith in the most turbulent of times.

Milk Fed by Melissa Broder

Rachel’s body and mommy issues are major and intertwined: she takes calorie counting and exercise to an extreme, and her therapist has suggested that she take a 90-day break from contact with her overbearing mother. Her workdays at a Hollywood talent management agency are punctuated by carefully regimented meals, one of them a 16-ounce serving of fat-free frozen yogurt from a shop run by Orthodox Jews. One day it’s not the usual teenage boy behind the counter, but his overweight older sister, Miriam. Miriam makes Rachel elaborate sundaes instead of her usual abstemious cups and Rachel lets herself eat them even though it throws her whole diet off. She realizes she’s attracted to Miriam, who comes to fill the bisexual Rachel’s fantasies, and they strike up a tentative relationship over Chinese food and classic film dates as well as Shabbat dinners at Miriam’s family home.

If you’re familiar with The Pisces, Broder’s Women’s Prize-longlisted debut, you should recognize the pattern here: a deep exploration of wish fulfilment and psychological roles, wrapped up in a sarcastic and sexually explicit narrative. Fat becomes not something to fear but a source of comfort; desire for food and for the female body go hand in hand. Rachel says, “It felt like a miracle to be able to eat what I desired, not more or less than that. It was shocking, as though my body somehow knew what to do and what not to do—if only I let it.”

With the help of her therapist, a rabbi that appears in her dreams, and the recurring metaphor of the golem, Rachel starts to grasp the necessity of mothering herself and becoming the shaper of her own life. I was uneasy that Miriam, like Theo in The Pisces, might come to feel more instrumental than real, but overall this was an enjoyable novel that brings together its disparate subjects convincingly. (But is it hot or smutty? You tell me.)

With thanks to Bloomsbury for the proof copy for review.

Unsettled Ground by Claire Fuller

At a glance, the cover for Fuller’s fourth novel seems to host a riot of luscious flowers and fruit, but look closer and you’ll see the daisies are withering and the grapes rotting; there’s a worm exiting the apple and flies are overseeing the decomposition. Just as the image slowly reveals signs of decay, Fuller’s novel gradually unveils the drawbacks of its secluded village setting. Jeanie and Julius Seeder, 51-year-old twins, lived with their mother, Dot, until she was felled by a stroke. They’d always been content with a circumscribed, self-sufficient existence, but now their whole way of life is called into question. Their mother’s rent-free arrangement with the landowners, the Rawsons, falls through, and the cash they keep in a biscuit tin in the cottage comes nowhere close to covering her debts, let alone a funeral.

During the Zoom book launch event, Fuller confessed that she’s “incapable of writing a happy novel,” so consider that your warning of how bleak things will get for her protagonists – though by the end there are pinpricks of returning hope. Before then, though, readers navigate an unrelenting spiral of rural poverty and bad luck, exacerbated by illiteracy and the greed and unkindness of others. One of Fuller’s strengths is creating atmosphere, and there are many images and details here that build the picture of isolation and pathos, such as a piano marooned halfway to a derelict caravan along a forest track and Jeanie having to count pennies so carefully that she must choose between toilet paper and dish soap at the shop.

Unsettled Ground is set in a fictional North Wessex Downs village not far from where I live. I loved spotting references to local places and to folk music – Jeanie and Julius might not have book smarts or successful careers, but they inherited Dot’s love of music and when they pick up a fiddle and guitar they tune in to the ancient magic of storytelling. Much of the novel is from Jeanie’s perspective and she makes for an out-of-the-ordinary yet relatable POV character. I found the novel heavy on exposition, which somewhat slowed my progress through it, but it’s comparable to Fuller’s other work in that it focuses on family secrets, unusual states of mind, and threatening situations. She’s rapidly become one of my favourite contemporary novelists, and I’d recommend this to you if you’ve liked her other work or Fiona Mozley’s Elmet.

With thanks to Penguin Fig Tree for the proof copy for review.

Dusk, Night, Dawn: On Revival and Courage by Anne Lamott

These are Lamott’s best new essays (if you don’t count Small Victories, which reprinted some of her greatest hits) in nearly a decade. The book is a fitting follow-up to 2018’s Almost Everything in that it tackles the same central theme: how to have hope in God and in other people even when the news – Trump, Covid, and climate breakdown – only heralds the worst.

One key thing that has changed in Lamott’s life since her last book is getting married for the first time, in her mid-sixties, to a Buddhist. “How’s married life?” people can’t seem to resist asking her. In thinking of marriage she writes about love and friendship, constancy and forgiveness, none of which comes easy. Her neurotic nature flares up every now and again, but Neal helps to talk her down. Fragments of her early family life come back as she considers all her parents were up against and concludes that they did their best (“How paltry and blocked our family love was, how narrow the bandwidth of my parents’ spiritual lives”).

Opportunities for maintaining quiet faith in spite of the circumstances arise all the time for her, whether it’s a variety show that feels like it will never end, a four-day power cut in California, the kitten inexplicably going missing, or young people taking to the streets to protest about the climate crisis they’re inheriting. A short postscript entitled “Covid College” gives thanks for “the blessings of COVID: we became more reflective, more contemplative.”

The prose and anecdotes feel fresher here than in several of the author’s other recent books. I highlighted quote after quote on my Kindle. Some of these essays will be well worth rereading and deserve to become classics in the Lamott canon, especially “Soul Lather,” “Snail Hymn,” “Light Breezes,” and “One Winged Love.”

I read an advanced digital review copy via NetGalley. Available from Riverhead in the USA and SPCK in the UK.

Brood by Jackie Polzin

Polzin’s debut novel is a quietly touching story of a woman in the Midwest raising chickens and coming to terms with the shape of her life. The unnamed narrator is Everywoman and no one at the same time. As in recent autofiction by Rachel Cusk and Sigrid Nunez, readers find observations of other people (and animals), a record of their behaviour and words; facts about the narrator herself are few and far between, though it is possible to gradually piece together a backstory for her. At one point she reveals, with no fanfare, that she miscarried four months into pregnancy in the bathroom of one of the houses she cleans. There is a bittersweet tone to this short work. It’s a low-key, genuine portrait of life in the in-between stages and how it can be affected by fate or by other people’s decisions.

See my full review at BookBrowse. I was also lucky enough to do an interview with the author.

I read an advanced digital review copy via Edelweiss. Available from Doubleday in the USA. To be released in the UK by Picador tomorrow, April 1st.

After a fall landed her in hospital with a cracked skull, Abbs couldn’t wait to roam again and vowed all her future holidays would be walking ones. What time she had for pleasure reading while raising children was devoted to travel books; looking at her stacks, she realized they were all by men. Her challenge to self was to find the women and recreate their journeys. I was drawn to this because I’d enjoyed

After a fall landed her in hospital with a cracked skull, Abbs couldn’t wait to roam again and vowed all her future holidays would be walking ones. What time she had for pleasure reading while raising children was devoted to travel books; looking at her stacks, she realized they were all by men. Her challenge to self was to find the women and recreate their journeys. I was drawn to this because I’d enjoyed  “My mother and I have symptoms of illness without any known cause,” Hattrick writes. When they showed signs of the ME/CFS their mother had suffered from since 1995, it was assumed there was imitation going on – that a “shared hysterical language” was fuelling their continued infirmity. It didn’t help that both looked well, so could pass as normal despite debilitating fatigue. Into their own family’s story, Hattrick weaves the lives and writings of chronically ill women such as Elizabeth Barrett Browning (see my review of Fiona Sampson’s biography,

“My mother and I have symptoms of illness without any known cause,” Hattrick writes. When they showed signs of the ME/CFS their mother had suffered from since 1995, it was assumed there was imitation going on – that a “shared hysterical language” was fuelling their continued infirmity. It didn’t help that both looked well, so could pass as normal despite debilitating fatigue. Into their own family’s story, Hattrick weaves the lives and writings of chronically ill women such as Elizabeth Barrett Browning (see my review of Fiona Sampson’s biography,  I loved Powles’s bite-size food memoir,

I loved Powles’s bite-size food memoir,  Music.Football.Fatherhood, a British equivalent of Mumsnet, brings dads together in conversation. These 20 essays by ordinary fathers run the gamut of parenting experiences: postnatal depression, divorce, single parenthood, a child with autism, and much more. We’re used to childbirth being talked about by women, but rarely by their partners, especially things like miscarriage, stillbirth and trauma. I’ve already written on

Music.Football.Fatherhood, a British equivalent of Mumsnet, brings dads together in conversation. These 20 essays by ordinary fathers run the gamut of parenting experiences: postnatal depression, divorce, single parenthood, a child with autism, and much more. We’re used to childbirth being talked about by women, but rarely by their partners, especially things like miscarriage, stillbirth and trauma. I’ve already written on  Santhouse is a consultant psychiatrist at London’s Guy’s and Maudsley hospitals. This book was an interesting follow-up to Ill Feelings (above) in that the author draws an important distinction between illness as a subjective experience and disease as an objective medical reality. Like Abdul-Ghaaliq Lalkhen does in

Santhouse is a consultant psychiatrist at London’s Guy’s and Maudsley hospitals. This book was an interesting follow-up to Ill Feelings (above) in that the author draws an important distinction between illness as a subjective experience and disease as an objective medical reality. Like Abdul-Ghaaliq Lalkhen does in

A Still Life by Josie George: Over a year of lockdowns, many of us became accustomed to spending most of the time at home. But for Josie George, social isolation is nothing new. Chronic illness long ago reduced her territory to her home and garden. The magic of A Still Life is in how she finds joy and purpose despite extreme limitations. Opening on New Year’s Day and travelling from one winter to the next, the book is a window onto George’s quiet existence as well as the turning of the seasons. (Reviewed for TLS.)

A Still Life by Josie George: Over a year of lockdowns, many of us became accustomed to spending most of the time at home. But for Josie George, social isolation is nothing new. Chronic illness long ago reduced her territory to her home and garden. The magic of A Still Life is in how she finds joy and purpose despite extreme limitations. Opening on New Year’s Day and travelling from one winter to the next, the book is a window onto George’s quiet existence as well as the turning of the seasons. (Reviewed for TLS.)

A Braided Heart by Brenda Miller: Miller, a professor of creative writing, delivers a master class on the composition and appreciation of autobiographical essays. In 18 concise pieces, she tracks her development as a writer and discusses the “lyric essay”—a form as old as Seneca that prioritizes imagery over narrative. These innovative and introspective essays, ideal for fans of Anne Fadiman, showcase the interplay of structure and content. (Coming out on July 13th from the University of Michigan Press. My first review for Shelf Awareness.)

A Braided Heart by Brenda Miller: Miller, a professor of creative writing, delivers a master class on the composition and appreciation of autobiographical essays. In 18 concise pieces, she tracks her development as a writer and discusses the “lyric essay”—a form as old as Seneca that prioritizes imagery over narrative. These innovative and introspective essays, ideal for fans of Anne Fadiman, showcase the interplay of structure and content. (Coming out on July 13th from the University of Michigan Press. My first review for Shelf Awareness.)

Pilgrim Bell by Kaveh Akbar: An Iranian American poet imparts the experience of being torn between cultures and languages, as well as between religion and doubt, in this gorgeous collection of confessional verse. Food, plants, animals, and the body supply the book’s imagery. Wordplay and startling juxtapositions lend lightness to a wistful, intimate collection that seeks belonging and belief. (Coming out on August 3rd from Graywolf Press. Reviewed for Shelf Awareness.)

Pilgrim Bell by Kaveh Akbar: An Iranian American poet imparts the experience of being torn between cultures and languages, as well as between religion and doubt, in this gorgeous collection of confessional verse. Food, plants, animals, and the body supply the book’s imagery. Wordplay and startling juxtapositions lend lightness to a wistful, intimate collection that seeks belonging and belief. (Coming out on August 3rd from Graywolf Press. Reviewed for Shelf Awareness.)

(20 Books of Summer, #5) “Get that dried crap away from my bird!” That random line about herbs is one my husband and I remember from a Bourdain TV program and occasionally quote to each other. It’s a mild curse compared to the standard fare in this flashy memoir about what really goes on in restaurant kitchens. His is a macho, vulgar world of sex and drugs. In the “wilderness years” before he opened his Les Halles restaurant, Bourdain worked in kitchens in Baltimore and New York City and was addicted to heroin and cocaine. Although he eventually cleaned up his act, he would always rely on cigarettes and alcohol to get through ridiculously long days on his feet.

(20 Books of Summer, #5) “Get that dried crap away from my bird!” That random line about herbs is one my husband and I remember from a Bourdain TV program and occasionally quote to each other. It’s a mild curse compared to the standard fare in this flashy memoir about what really goes on in restaurant kitchens. His is a macho, vulgar world of sex and drugs. In the “wilderness years” before he opened his Les Halles restaurant, Bourdain worked in kitchens in Baltimore and New York City and was addicted to heroin and cocaine. Although he eventually cleaned up his act, he would always rely on cigarettes and alcohol to get through ridiculously long days on his feet. (20 Books of Summer, #6) I don’t know what took me so long to read another novel by Ruth Ozeki after A Tale for the Time Being, one of my favorite books of 2013. This is nearly as fresh, vibrant and strange. Set in 1991, it focuses on the making of a Japanese documentary series, My American Wife, sponsored by a beef marketing firm. Japanese American filmmaker Jane Takagi-Little is tasked with finding all-American families and capturing their daily lives – and best meat recipes. The traditional values and virtues of her two countries are in stark contrast, as are Main Street/Ye Olde America and the burgeoning Walmart culture.

(20 Books of Summer, #6) I don’t know what took me so long to read another novel by Ruth Ozeki after A Tale for the Time Being, one of my favorite books of 2013. This is nearly as fresh, vibrant and strange. Set in 1991, it focuses on the making of a Japanese documentary series, My American Wife, sponsored by a beef marketing firm. Japanese American filmmaker Jane Takagi-Little is tasked with finding all-American families and capturing their daily lives – and best meat recipes. The traditional values and virtues of her two countries are in stark contrast, as are Main Street/Ye Olde America and the burgeoning Walmart culture. (20 Books of Summer, #7) I read the first couple of chapters, in which he plans his adventure, and then started skimming. I expected this to be a breezy read I would race through, but the voice was neither inviting nor funny. I also hoped to find more about non-chain supermarkets and restaurants – that’s why I put this on the pile for my foodie challenge in the first place – but, from a skim, it mostly seemed to be about car trouble, gas stations and fleabag motels. The only food-related moments are when Gorman (a vegetarian) downs three fast food burgers and orders of fries in 10 minutes and, predictably, vomits them all back up; and when he stops at an old-fashioned soda fountain for breakfast.

(20 Books of Summer, #7) I read the first couple of chapters, in which he plans his adventure, and then started skimming. I expected this to be a breezy read I would race through, but the voice was neither inviting nor funny. I also hoped to find more about non-chain supermarkets and restaurants – that’s why I put this on the pile for my foodie challenge in the first place – but, from a skim, it mostly seemed to be about car trouble, gas stations and fleabag motels. The only food-related moments are when Gorman (a vegetarian) downs three fast food burgers and orders of fries in 10 minutes and, predictably, vomits them all back up; and when he stops at an old-fashioned soda fountain for breakfast. (20 Books of Summer, #8) I read the first 25 pages and then started skimming. This is a story of a group of friends – paisanos, of mixed Mexican, Native American and Caucasian blood – in Monterey, California. During World War I, Danny serves as a mule driver and Pilon is in the infantry. When discharged from the Army, they return to Tortilla Flat, where Danny has inherited two houses. He lives in one and Pilon is his tenant in the other (though Danny will never see a penny in rent). They’re a pair of loveable scamps, like Huck Finn all grown up, stealing wine and chickens left and right.

(20 Books of Summer, #8) I read the first 25 pages and then started skimming. This is a story of a group of friends – paisanos, of mixed Mexican, Native American and Caucasian blood – in Monterey, California. During World War I, Danny serves as a mule driver and Pilon is in the infantry. When discharged from the Army, they return to Tortilla Flat, where Danny has inherited two houses. He lives in one and Pilon is his tenant in the other (though Danny will never see a penny in rent). They’re a pair of loveable scamps, like Huck Finn all grown up, stealing wine and chickens left and right.