#1952Club: Patricia Highsmith, Paul Tillich & E.B. White

Simon and Karen’s classics reading weeks are always a great excuse to pick up some older books. I assembled an unlikely trio of lesbian romance, niche theology, and an animal-lover’s children’s classic.

Carol by Patricia Highsmith

Originally published as The Price of Salt under the pseudonym Claire Morgan, this is widely considered the first lesbian novel with a happy ending (it’s more open-ended, really, but certainly not tragic; suicide was a common consequence in earlier fiction). Therese, a 19-year-old aspiring stage designer in New York City, takes a job selling dolls in a department store one Christmas season. Her boyfriend, Richard, is a painter and has promised to take her to Europe, but she’s lukewarm about him and the physical side of their relationship has never interested her. One day, a beautiful blonde woman in a fur coat – “Mrs. H. F. Aird” (Carol) – comes to her counter to order a doll and have it sent to her out in New Jersey. Therese sends a Christmas card to the same address, and the women start meeting up for drinks and meals.

It takes time for them to clarify their feelings to themselves, let alone to each other. “It would be almost like love, what she felt for Carol, except that Carol was a woman,” Therese thinks early on. When she first visits Carol’s home, a mothering dynamic prevails. Carol is going through a divorce and worries about its effect on her daughter, Rindy. The older woman tucks Therese into bed and brings her warm milk. Scenes like this have symbolic power but aren’t overdone; another has Therese and Richard out flying kites. She brings up homosexuality as a theoretical (“Did you ever hear of it? … I mean two people who fall in love suddenly with each other, out of the blue. Say two men or two girls”) and he cuts her kite strings.

It takes time for them to clarify their feelings to themselves, let alone to each other. “It would be almost like love, what she felt for Carol, except that Carol was a woman,” Therese thinks early on. When she first visits Carol’s home, a mothering dynamic prevails. Carol is going through a divorce and worries about its effect on her daughter, Rindy. The older woman tucks Therese into bed and brings her warm milk. Scenes like this have symbolic power but aren’t overdone; another has Therese and Richard out flying kites. She brings up homosexuality as a theoretical (“Did you ever hear of it? … I mean two people who fall in love suddenly with each other, out of the blue. Say two men or two girls”) and he cuts her kite strings.

The second half of the book has Carol and Therese setting out on a road trip out West. It should be an idyllic consummation, but they realize they’re being trailed by a private detective collecting evidence for Carol’s husband Harge to use against her in a custody battle. I was reminded of the hunt for Humbert Humbert and his charge in Lolita; “the whole world was ready to be their enemy,” Therese realizes, and to consider their relationship “sordid and pathological,” as Richard describes it in a letter.

The novel is a beautiful and subtle romance that unfolds despite the odds against it. I’d read five of Highsmith’s mysteries and thought them serviceable but nothing special (I don’t read crime in general). This does, however, share their psychological intensity and the suspense about how things will play out. Highsmith gives details about Therese’s early life and Carol’s previous intimate friendship that help to explain some things but never reduce either character to a diagnosis or a tendency. Neither of them wanted just anyone, some woman; it was this specific combination of souls that sparked at first sight. (Secondhand from a charity shop that closed long ago, so I know I’d had it on my shelf unread since 2016!) ![]()

The Courage to Be by Paul Tillich

Tillich is a theologian who left Nazi Germany for the USA in 1933. I had to read selections from his work as part of my Religion degree (during the Pauline Theology tutorial I took in Oxford during my year abroad, I think). This book is based on a lecture series he delivered at Yale University. He posits that in an age of anxiety, which “becomes general if the accustomed structures of meaning, power, belief and order disintegrate” – certainly apt for today! – it is more important than ever to develop the courage to be oneself and to be “as a part.” The individual and the collective are of equal importance, then. Tillich discusses various philosophers and traditions, from the Stoics to Existentialism. I have to admit that I barely got anything out of this, I found it so jargon-filled, repetitive and elliptical. It’s been probably 15 years or more since I’ve read any proper theology. I adopted that old student skimming trick of reading the first paragraph of each chapter, followed by the topic sentence of each paragraph, but that left me mostly none the wiser. Anyway, I believe his conclusion is that, when assailed by doubt, we can rely on “the God above the God of theism” – by which I take it he means the ground of all being rather than the deity envisioned by any specific religious system. (University library)

Tillich is a theologian who left Nazi Germany for the USA in 1933. I had to read selections from his work as part of my Religion degree (during the Pauline Theology tutorial I took in Oxford during my year abroad, I think). This book is based on a lecture series he delivered at Yale University. He posits that in an age of anxiety, which “becomes general if the accustomed structures of meaning, power, belief and order disintegrate” – certainly apt for today! – it is more important than ever to develop the courage to be oneself and to be “as a part.” The individual and the collective are of equal importance, then. Tillich discusses various philosophers and traditions, from the Stoics to Existentialism. I have to admit that I barely got anything out of this, I found it so jargon-filled, repetitive and elliptical. It’s been probably 15 years or more since I’ve read any proper theology. I adopted that old student skimming trick of reading the first paragraph of each chapter, followed by the topic sentence of each paragraph, but that left me mostly none the wiser. Anyway, I believe his conclusion is that, when assailed by doubt, we can rely on “the God above the God of theism” – by which I take it he means the ground of all being rather than the deity envisioned by any specific religious system. (University library)

Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White

My library has a small section of the children’s department called “Family Matters” that includes the labels “First Time” (starting school, etc.), “Family” (divorce, new baby), “Health” (autism, medical conditions) and “Death.” I have the feeling Charlotte’s Web is not at all well known in the UK, whereas it’s a standard in the USA alongside L.M. Montgomery and Laura Ingalls Wilder. Were it more familiar to British children, it would be a great addition to that “Death” shelf. (Don’t read the Puffin Modern Classics introduction if you don’t want spoilers!) Wilbur is a doubly rescued pig. First, Fern Arable hand-rears him when he’s the doomed runt of the litter. When he’s transferred to Uncle Homer Zuckerman’s farm and an old sheep explains he’ll be fattened up for slaughter, his new friend Charlotte intervenes.

My library has a small section of the children’s department called “Family Matters” that includes the labels “First Time” (starting school, etc.), “Family” (divorce, new baby), “Health” (autism, medical conditions) and “Death.” I have the feeling Charlotte’s Web is not at all well known in the UK, whereas it’s a standard in the USA alongside L.M. Montgomery and Laura Ingalls Wilder. Were it more familiar to British children, it would be a great addition to that “Death” shelf. (Don’t read the Puffin Modern Classics introduction if you don’t want spoilers!) Wilbur is a doubly rescued pig. First, Fern Arable hand-rears him when he’s the doomed runt of the litter. When he’s transferred to Uncle Homer Zuckerman’s farm and an old sheep explains he’ll be fattened up for slaughter, his new friend Charlotte intervenes.

Charlotte is a fine specimen of a barn spider, well spoken and witty. She puts her mind to saving Wilbur’s bacon by weaving messages into her web, starting with “Some Pig.” He’s soon a county-wide spectacle, certain to survive the chop. But a farm is always, inevitably, a place of death. White fashions such memorable characters, including Templeton the gluttonous rat, and captures the hope of new life returning as the seasons turn over. Talking animals aren’t difficult to believe in when Fern can hear every word they say. The black-and-white line drawings are adorable. And making readers care about invertebrates? That’s a lasting achievement. I’m sure I read this several times as a child, but I appreciated it all the more as an adult. (Little Free Library) ![]()

I’ve previously participated in the 1920 Club, 1956 Club, 1936 Club, 1976 Club, 1954 Club, 1929 Club, 1940 Club, 1937 Club, and 1970 Club.

Spring Journeys with Edwin Way Teale and Edward Thomas

When I heard that Little Toller were reissuing their edition of Edward Thomas’s In Pursuit of Spring, I couldn’t resist pairing it with Edwin Way Teale’s book about the progress of the season up the United States, North with the Spring. These spring journeys, documented by authors delighting in nature’s bounty and responding with poetry, inspired mixed feelings in me: vicarious nostalgia, but also sadness for all that has been lost since they set out in the 1910s and 1950s, respectively.

It’s hard to live joyfully when evidence of the destruction of nature is overwhelming. Enjoying what still exists doesn’t seem like enough. But it’s a start. So this year I’ve been careful to note every phenological landmark: the first swift, the first hearing of a cuckoo, a rare sighting of a live hedgehog. One day in late April I stood on the towpath for hours watching a cloud of swallows and martins swooping for insects. I’ve also enjoyed watching from my office window as sparrows come and go from a nest box.

North with the Spring by Edwin Way Teale (1951)

I’ve previously reviewed Teale’s Autumn Across America and Springtime in Britain and consider him one of the classic – and most underrated – American nature writers. I was delighted to find a copy of this first seasonal volume on our trip to Northumberland a few years ago. As in the autumn book, he and his wife Nellie undertake a road trip, this time travelling from Florida up to New England, a total of 17,000 miles. Their journey lasted 130 days because instead of waiting for 21 March they started weeks before; spring comes early to the Gulf coast. Their time in Florida feels endless, constituting over a third of the book. Although it’s true that there are (were?) many peerless ecosystems there between the scrub and swamp, I grew impatient to move on to other states. The meet-up with Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, who took them on a picnic to ‘The Yearling country,’ was a highlight.

They travel alongside the spring warblers; past river deltas and barrier islands, by mountain meadows and forests. Other stops include Monticello and New Jersey’s pine barrens. A stopover in New York City dramatizes the difference between civilization and relative wilderness. I particularly enjoyed a pair of chapters set in Tennessee: first the wonder of Nickajack Cave, then the horror of the deforested and poisoned Ducktown Desert. Teale seems ahead of his time in decrying people’s wilful ignorance – one man they met denied the fact of migration, insisting the birds were always around – and failure to consider nature. His scenes and conversations feel fully natural; he’s as interested in people as in wildlife, and that humanism comes across in his writing.

They travel alongside the spring warblers; past river deltas and barrier islands, by mountain meadows and forests. Other stops include Monticello and New Jersey’s pine barrens. A stopover in New York City dramatizes the difference between civilization and relative wilderness. I particularly enjoyed a pair of chapters set in Tennessee: first the wonder of Nickajack Cave, then the horror of the deforested and poisoned Ducktown Desert. Teale seems ahead of his time in decrying people’s wilful ignorance – one man they met denied the fact of migration, insisting the birds were always around – and failure to consider nature. His scenes and conversations feel fully natural; he’s as interested in people as in wildlife, and that humanism comes across in his writing.

“We longed for a thousand springs on the road instead of this one. For spring is like life. You never grasp it entire; you touch it here, there; you know it only in parts and fragments.”

(Secondhand – Barter Books, Alnwick)

In Pursuit of Spring by Edward Thomas (1914)

On Good Friday, 21 March 1913, Edward Thomas set off on his bicycle from his parents’ home in South London. He was bound southwest, toward Somerset and the height of spring. At cycling and walking pace, he would truly experience the development of the season, whereas

“Many days in London have no weather. We are aware only that it is hot or cold, dry or wet; that we are in or out of doors; that we are at ease or not.”

He prepares himself for hardship and slog:

“Spring would come, of course – nothing, I supposed, could prevent it – and I should have to make up my mind how to go westward. Whatever I did, Salisbury Plain was to be crossed”

It’s remarkable both how much and how little has changed in the intervening century and more. The place names, plant and bird species, and alternation of town and countryside are all familiar, but the difference is stark when you see Thomas’s black-and-white photographs that illustrate the text. These dirt roads are empty. You’d have to search high and low today to find the kind of unspoiled fields, rivers, churchyards, hedgerows and stone walls that he memorializes.

It’s remarkable both how much and how little has changed in the intervening century and more. The place names, plant and bird species, and alternation of town and countryside are all familiar, but the difference is stark when you see Thomas’s black-and-white photographs that illustrate the text. These dirt roads are empty. You’d have to search high and low today to find the kind of unspoiled fields, rivers, churchyards, hedgerows and stone walls that he memorializes.

Everything he sees drives him back to poetry, with long passages quoted from authors who have fallen somewhat out of fashion, such as George Herbert and Alexander Pope. I loved the scene where he buys a book at a secondhand furniture shop (for two pence, mind you) and then ignores it to eavesdrop on fellow diners at a restaurant. He has words of high praise for W.H. Hudson:

“Were men to disappear they might be reconstructed from the Bible and the Russian novelists; … Hudson so writes of birds that if ever … they should cease to exist, and should leave us to ourselves on a benighted planet, we should have to learn from him what birds were.”

Thomas also mentions William Cobbett, whose Rural Rides this reminded me of strongly. Both are slow-paced journeys around a rural England that no longer exists. Today Thomas is better remembered as a poet; he would be one of the fallen in a First World War battle just four years after this expedition. It was great to have a chance to read his nature writing, too.

With thanks to Little Toller for the free copy for review.

We’re off to rural France on Wednesday for eight days of relaxation and nature-watching; it’s not a sight-seeing or foodie trip like our time in Paris back in December. Ironically, it seems that it may be cold and rainy for much of the holiday, having been gorgeous in both countries this past week. We will hope for some sun and warmth, but have packed plenty of books and board games (and will acquire much wine) for when the weather is to be avoided inside.

What signs of the spring have you been seeing?

Spring Reads, Part II: Swifts, a Cuckoo, and a British Road Trip

Despite ongoing worries about biodiversity loss after last year’s drought, I had the most idyllic late spring evening yesterday. On the way home from an evening with Alice Winn hosted by Hungerford Bookshop (more on which anon), I sat at the station awaiting my train. It was 8:30 p.m. and still fully light, warm enough to be comfortable in a jacket, and a cuckoo serenaded me as I watched swifts wheeling by overhead.

For my second instalment of spring-themed reading (see Part I here), I have books about those very birds, one a nonfiction study of a species that is a welcome sign of late spring and summer in Europe, and a novel that takes up the metaphors associated with another notable species; plus a narrative of a circuitous route driven through a British spring.

Swifts and Us by Sarah Gibson (2020)

We first noticed the swifts had returned to Newbury on 29 April. Best of all, we think ‘our’ birds that nested in the space between the roof and rear gutter last year (see footage here) are back. We’ve also installed one swift and two house martin boxes along the wall from the corner, just in case. Swifts are truly amazing for the distances they travel and the almost fully aerial life they lead. They only touch down to breed and otherwise do everything else – eat, sleep, mate – on the wing. I skimmed this book over the course of two springs and learned that the screaming parties you may, if you are lucky, see tearing down your street are likely to be made up of one- or two-year-old birds. Those tending to nestlings will be quieter. (They’ll be ruthless about displacing house sparrows who try to steal their space, so we hope the questing sparrows we saw at the gutter a few weeks before didn’t get as far as nest-building.)

Beaks agape, swifts catch thousands of insects a day and keep them in a bolus in their throat to regurgitate for chicks. The sharp decline in insect numbers is a major concern, as well as the intensification of agriculture, climate change, and new houses or renovations that block up holes birds traditionally nest in. There are multiple species of swift – in southern Spain one can see five types – and in general they are considered to be of least conservation concern, but these matters are all relative in these days of climate crisis. Evolved to nest in cliffs and trees, they now live alongside humans except in rare places like Abernethy Forest near Inverness in Scotland, where they still nest in trees, in holes abandoned by woodpeckers.

Beaks agape, swifts catch thousands of insects a day and keep them in a bolus in their throat to regurgitate for chicks. The sharp decline in insect numbers is a major concern, as well as the intensification of agriculture, climate change, and new houses or renovations that block up holes birds traditionally nest in. There are multiple species of swift – in southern Spain one can see five types – and in general they are considered to be of least conservation concern, but these matters are all relative in these days of climate crisis. Evolved to nest in cliffs and trees, they now live alongside humans except in rare places like Abernethy Forest near Inverness in Scotland, where they still nest in trees, in holes abandoned by woodpeckers.

Gibson surveys swifts’ distribution and evolution, key figures in how we came to understand them (Gilbert White et al.), and early landmark studies (e.g. David Lack’s in Oxford). She also takes us through a typical summer swift schedule, and interviews some people who rehabilitate and advocate for swifts. Other chapters see her travelling to Italy, Switzerland and Ireland, the furthest west that swifts breed. If you find a grounded swift, she learns from bitter experience, keep it in a box with air holes and give it water on a cotton bud, but don’t feed or throw it up in the air. To release, take it to an open space and hold it on your hand above your head. If it’s ready to fly, it will. The current push to help swifts is requiring that nest blocks or boxes be incorporated in every new home design. (I signed this petition.)

This is a great source of basic information, though some of the background may be more detailed than the average reader needs. If you’re only going to read one book about swifts, I would be more likely to recommend Charles Foster’s The Screaming Sky, a literary monograph, but do follow up with this one. And soon we’ll also have Mark Cocker’s book about swifts, One Midsummer’s Day, which I hope to get hold of. (Public library)

Favourite lines:

“It is their otherness that makes them so fascinating. They touch our lives briefly and then vanish; this is part of their magic.”

“The brevity of their summer stays enhances their hold on our hearts. The season is short, their bold, wild chases over the roofs and high-pitched screams a fleeting experience: they are a metaphor for life itself. We need to act now to ensure these birds will scythe across our skies forever; to keep them in our streets, to keep them in abundance and common. All of us can do something within the compass of our lives to help tilt the balance back in their favour. If the will to do it is there, it can be done.”

Cuckoo by Wendy Perriam (1991)

(We started hearing cuckoos locally last week!) My second by Perriam, after The Stillness The Dancing, and I’ve amassed quite a pile for afterwards. Frances Parry Jones, in her early thirties, is desperate for a baby but her husband, Charles, doesn’t seem fussed. He goes along with fertility treatment but remains aloof like the posh snob Perriam depicts him to be – the opening line is “Typical of Charles to decant his sperm sample into a Fortnum and Mason’s jar.” Their comfortable home in Richmond is cut off from the messy reality of life, as represented by Frances’s friend Viv and her brood.

(We started hearing cuckoos locally last week!) My second by Perriam, after The Stillness The Dancing, and I’ve amassed quite a pile for afterwards. Frances Parry Jones, in her early thirties, is desperate for a baby but her husband, Charles, doesn’t seem fussed. He goes along with fertility treatment but remains aloof like the posh snob Perriam depicts him to be – the opening line is “Typical of Charles to decant his sperm sample into a Fortnum and Mason’s jar.” Their comfortable home in Richmond is cut off from the messy reality of life, as represented by Frances’s friend Viv and her brood.

Frances soon learns why Charles is unenthusiastic about having children: he already has one, a sullen teenager named Magda who lived with her mother in Hungary but has just arrived in London, “a greedy little cuckoo, commandeering the nest.” Though tempted to accept Magda as a replacement child, Frances just can’t manage it. However, they do find common ground through their japes with Ned, a free spirit Frances meets during her brief time as a taxi driver, and Frances starts to imagine how her life could be different. The portraits and sex scenes alike were a little grotesque here. I had to skim a lot to get through it. Here’s hoping for a better experience with the next one. (Secondhand copy passed on by Liz – thank you!)

Springtime in Britain by Edwin Way Teale (1970)

I discovered Teale a few years ago through the exceptional Autumn Across America, the first volume of a quartet illuminating the nature of the four seasons in the USA; he won a Pulitzer for the final book. Here he applied the same pattern across the pond, taking an 11,000-mile road trip around Britain with his wife Nellie. It’s a delight to see the country through his eyes, particularly places I know well (Devon, the New Forest, Wiltshire/Berkshire) or have visited recently (Northumberland). They find the early spring alarmingly cold and wet, but before long are rewarded with swathes of daffodils and bluebells. Several stake-outs finally result in hearing a nightingale. For the most part, the bird life is completely new to them, but he remarks on what North American species the European birds remind him of. “We felt we would travel to Britain just to hear the song thrush and the blackbird,” he maintains.

I discovered Teale a few years ago through the exceptional Autumn Across America, the first volume of a quartet illuminating the nature of the four seasons in the USA; he won a Pulitzer for the final book. Here he applied the same pattern across the pond, taking an 11,000-mile road trip around Britain with his wife Nellie. It’s a delight to see the country through his eyes, particularly places I know well (Devon, the New Forest, Wiltshire/Berkshire) or have visited recently (Northumberland). They find the early spring alarmingly cold and wet, but before long are rewarded with swathes of daffodils and bluebells. Several stake-outs finally result in hearing a nightingale. For the most part, the bird life is completely new to them, but he remarks on what North American species the European birds remind him of. “We felt we would travel to Britain just to hear the song thrush and the blackbird,” he maintains.

Nellie develops pneumonia and has to convalesce in Kent, but otherwise personal matters hardly come into the narrative. Teale is well versed in English nature writing and often references classics by the likes of John Clare and Gilbert White that inspired destinations. (They spend an excessive number of days on their pilgrimage to White’s Selborne.) He also reports on perceived threats of the time, such as small animals getting stuck in littered milk bottles. While it was, inevitably, a little distressing to think of the abundance and diversity he was still experiencing in the late 1960s that has since been lost to development, I mostly found this a pleasant meander. Some things never change: the magic of prehistoric sites; the grossness of some cities (“we forgot the misadventure of Slough”). (Secondhand)

What signs of late spring are you seeing?

A Look Back at 2021’s Happenings, Including Recent USA Trip

I’m old-fashioned and still use a desk calendar to keep track of appointments and deadlines. I also add in notes after the fact to remember births, deaths, elections, and other nationally and internationally important events. A look back through my 2021 “The Reading Woman” calendar reminded me that last January held a bit of snow, a third UK lockdown, an attempted coup at the U.S. capitol, and the inauguration of Joe Biden.

Activities continued online for much of the year:

- 15 music gigs (most of them by The Bookshop Band)

- 11 literary events, including book launches and prize announcements

- 9 book club meetings

- 3 literary festivals

- 2 escape rooms

- 1 progressive dinner

We were lucky enough to manage a short break in Somerset and a wonderful week in Northumberland. In August my mother and stepfather came to stay with us for a week and we showed off our area to them on daytrips.

As we entered the autumn, a few more things returned to in-person:

- 5 music gigs

- 2 book club meetings (not counting a few outdoor socials earlier in the year)

- 1 book launch

- 1 conference

I was also fortunate to get back to the States twice this year, once in May–June for my mother’s wedding and again in December for Christmas.

On this most recent trip I had some fun “life meeting books” moments (the photos of me are by Chris Foster):

On this most recent trip I had some fun “life meeting books” moments (the photos of me are by Chris Foster):

- An overnight stay on Chincoteague Island, famous for its semi-wild ponies, prompted me to reread a childhood favorite, Misty of Chincoteague by Marguerite Henry.

Driving from my sister’s house to my mother’s new place involves some time on Route 30, aka the Lincoln Highway, through Pennsylvania. Her town even has a tourist attraction called Lincoln Highway Experience that we may check out on a future trip. (The other claims to fame there: it was home to golfer Arnold Palmer and Mister Rogers, and the birthplace of the banana split.)

Driving from my sister’s house to my mother’s new place involves some time on Route 30, aka the Lincoln Highway, through Pennsylvania. Her town even has a tourist attraction called Lincoln Highway Experience that we may check out on a future trip. (The other claims to fame there: it was home to golfer Arnold Palmer and Mister Rogers, and the birthplace of the banana split.)

- At the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, we met the original “Dippy” the diplodocus, a book about whom I reviewed for Foreword in 2020.

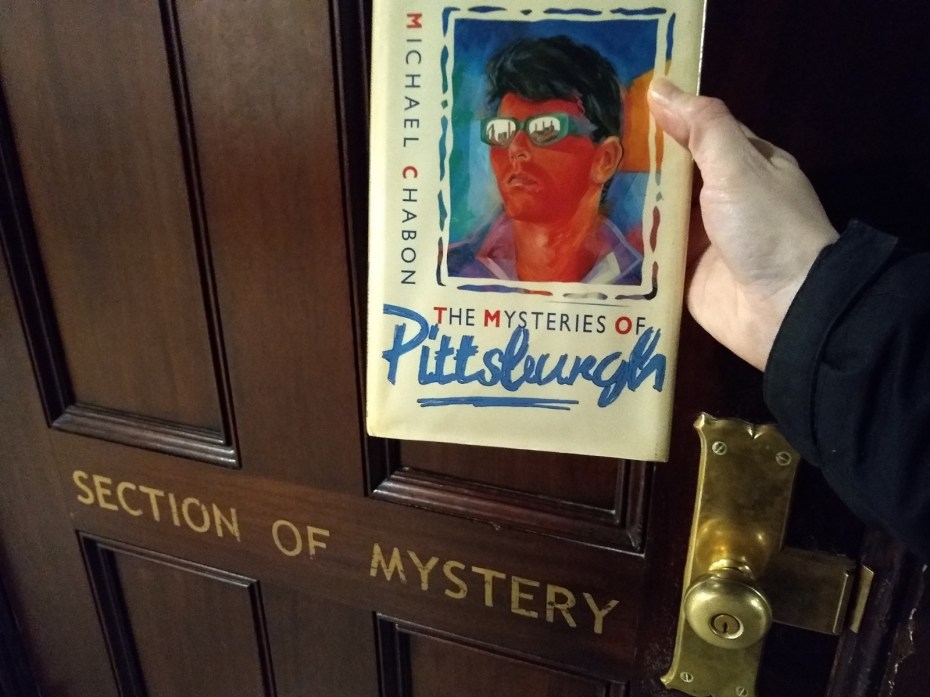

- I also took along a copy of The Mysteries of Pittsburgh by Michael Chabon and snapped a photo of it in an appropriately mysterious corner of the museum. Unfortunately, I didn’t get past the first few chapters as this debut novel felt dated and verging on racist.

No matter, though, as I donated it at a Little Free Library.

We sought out a few LFLs on our trip, including that one in a log at Cromwell Valley Park in Maryland, where I picked up a Margot Livesey novel and a couple of travel books. My only other acquisition of the trip was a new paperback of Beneficence by Meredith Hall (author of one of the first books to turn me on to memoirs) from Curious Iguana in Frederick, Maryland, my college town. No secondhand book shopping opportunities this time, alas; just lots of driving in our rental car to visit disparate friends and relatives. However, this was my early Christmas book haul from my husband before we set off:

We sought out a few LFLs on our trip, including that one in a log at Cromwell Valley Park in Maryland, where I picked up a Margot Livesey novel and a couple of travel books. My only other acquisition of the trip was a new paperback of Beneficence by Meredith Hall (author of one of the first books to turn me on to memoirs) from Curious Iguana in Frederick, Maryland, my college town. No secondhand book shopping opportunities this time, alas; just lots of driving in our rental car to visit disparate friends and relatives. However, this was my early Christmas book haul from my husband before we set off:

Another fun stop during our trip was at Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia, where we admired wreaths made of mostly natural ingredients like fruit.

The big news from my household this winter is that we have bought our first home, right around the corner from where we rent now, and hope to move in within the next couple of months. Our aim is to do all the bare-minimum renovations in 2022, in time to put up a tree in the living room bay window and a homemade wreath on the door for next Christmas!

Despite these glimpses of travels and merriment, Covid still feels all too real. I appreciated these reminders I saw recently, one in Bath and the other at the museum in Pittsburgh (Covid Manifesto by Cauleen Smith, which originated on Instagram).

“We all deserve better than ‘back to normal’.”

The Blind Assassin Reread for #MARM, and Other Doorstoppers

It’s the fourth annual Margaret Atwood Reading Month (#MARM), hosted by Canadian blogger extraordinaire Marcie of Buried in Print. In previous years, I’ve read Surfacing and The Edible Woman, The Robber Bride and Moral Disorder, and Wilderness Tips. This year Laila at Big Reading Life and I did a buddy reread of The Blind Assassin, which was historically my favourite Atwood novel. I’d picked up a free paperback the last time I was at The Book Thing of Baltimore. Below are some quick thoughts based on what I shared with Laila as I was reading.

The Blind Assassin (2000)

Winner of the Booker Prize and Hammett Prize; shortlisted for the Orange Prize

I must have first read this about 13 years ago. The only thing I remembered before I started my reread was that there is a science fiction book-within-the-book. I couldn’t recall anything else about the setup before I read in the blurb about the suspicious circumstances of Laura’s death in 1945. Indeed, the opening line, which deserves to be famous, is “Ten days after the war ended, my sister Laura drove a car off a bridge.”

I always love novels about sisters, and Iris is a terrific narrator. Now a cantankerous elderly woman, she takes us back through her family history: her father’s button factory and his clashes with organizing workers, her mother’s early death, and her enduring relationship with their housekeeper, Reenie. Iris and Laura met a young man named Alex Thomas, a war orphan with radical views, at the factory’s Labour Day picnic, and it was clear early on that Laura was smitten, while Iris went on to marry Richard Griffen, a nouveau riche industrialist.

Interspersed with Iris’s recollections are newspaper articles that give a sense that the Chase family might be cursed, and excerpts from The Blind Assassin, Laura’s posthumously published novel. Daring for its time in terms of both explicit content and literary form (e.g., no speech marks), it has a storyline rather similar to 1984, with an upper-crust woman having trysts with a working-class man in his squalid lodgings. During their time snatched together, he also tells her a story inspired by the pulp sci-fi of the time. I was less engaged by the story-within-the-story(-within-the-story) this time around compared to Iris’s current life and flashbacks.

In the back of my mind, I had a vague notion that there was a twist coming, and in my impatience to see if I was right I ended up skimming much of the second half of the novel. My hunch was proven correct, but I was disappointed with myself that I wasn’t able to enjoy the journey more a second time around. Overall, this didn’t wow me on a reread, but then again, I am less dazzled by literary “tricks” these days. At the sentence level, however, the writing was fantastic, including descriptions of places, seasons and characters’ psychology. It’s intriguing to think about whether we can ever truly know Laura given Iris’s guardianship of her literary legacy.

If you haven’t read this before, find a time when you can give it your full attention and sink right in. It’s so wise on family secrets and the workings of memory and celebrity, and the weaving in of storylines in preparation for the big reveal is masterful.

Some favourite passages:

“What fabrications they are, mothers. Scarecrows, wax dolls for us to stick pins into, crude diagrams. We deny them an existence of their own, we make them up to suit ourselves – our own hungers, our own wishes, our own deficiencies.”

“Beginnings are sudden, but also insidious. They creep up on you sideways, they keep to the shadows, they lurk unrecognized. Then, later, they spring.”

“The only way you can write the truth is to assume that what you set down will never be read. Not by any other person, and not even by yourself at some later date. Otherwise you begin excusing yourself. You must see the writing as emerging like a long scroll of ink from the index finger of your right hand; you must see your left hand erasing it. Impossible, of course.”

My original rating (c. 2008): ![]()

My rating now: ![]()

What to read for #MARM next year, I wonder??

In general, I have been struggling mightily with doorstoppers this year. I just don’t seem to have the necessary concentration, so Novellas in November has been a boon. I’ve been battling with Ruth Ozeki’s latest novel for months, and another attempted buddy read of 460 pages has also gone by the wayside. I’ll write a bit more on this for #LoveYourLibrary on Monday, including a couple of recent DNFs. The Blind Assassin was only my third successful doorstopper of the year so far. After The Absolute Book, the other one was:

The Lincoln Highway by Amor Towles

In Towles’ third novel – a big, old-fashioned dose of Americana – brothers and pals set out from Nebraska on road and rail adventures to find a fortune in 1950s New York. The book features some fantastic characters. Precocious Billy steals every scene he appears in. Duchess is a delightfully flamboyant bounder, peppering his speech with malapropisms and Shakespeare quotes. However, Emmett is a dull protagonist, and it’s disappointing that Sally, one of just two main female characters, plays such a minor role. A danger with an episodic narrative is that random events and encounters pile up but don’t do much to further the plot. At nearly 200 pages in, I realized little of consequence had happened yet. A long road, then, with some ups and downs along the way, but Towles’ fans will certainly want to sign up for the ride.

In Towles’ third novel – a big, old-fashioned dose of Americana – brothers and pals set out from Nebraska on road and rail adventures to find a fortune in 1950s New York. The book features some fantastic characters. Precocious Billy steals every scene he appears in. Duchess is a delightfully flamboyant bounder, peppering his speech with malapropisms and Shakespeare quotes. However, Emmett is a dull protagonist, and it’s disappointing that Sally, one of just two main female characters, plays such a minor role. A danger with an episodic narrative is that random events and encounters pile up but don’t do much to further the plot. At nearly 200 pages in, I realized little of consequence had happened yet. A long road, then, with some ups and downs along the way, but Towles’ fans will certainly want to sign up for the ride. ![]()

See my full review for BookBrowse; see also my related article on Studebaker cars.

With thanks to Hutchinson for the free copy for review.

Anything by Atwood, or any doorstoppers, on your pile recently?

20 Books of Summer, #6–8: Aristide, Hood, Lamott

This latest batch of colour-themed summer reads took me from a depleted post-pandemic landscape to the heart of dysfunctional families in Rhode Island and California.

Under the Blue by Oana Aristide (2021)

Fans of Station Eleven, this one’s for you: the best dystopian novel I’ve read since Mandel’s. Aristide started writing this in 2017, and unknowingly predicted a much worse pandemic than Covid-19. In July 2020, Harry, a middle-aged painter inhabiting his late nephew’s apartment in London, finally twigs that something major is going on. He packs his car and heads to his Devon cottage, leaving its address under the door of the cute neighbour he sometimes flirts with. Hot days stack up and his new habits of rationing food and soap are deeply ingrained by the time the gal from #22, Ash – along with her sister, Jessie, a doctor who stocked up on medicine before fleeing her hospital – turn up. They quickly sink into his routines but have a bigger game plan: getting to Uganda, where their mum once worked and where they know they will be out of range of Europe’s at-risk nuclear reactors. An epic road trip ensues.

It gradually becomes clear that Harry, Ash and Jessie are among mere thousands of survivors worldwide, somehow immune to a novel disease that spread like wildfire. There are echoes of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road in the way that they ransack the homes of the dead for supplies, and yet there’s lightness to their journey. Jessie has a sharp sense of humour, provoking much banter, and the places they pass through in France and Italy are gorgeous despite the circumstances. It would be a privilege to wander empty tourist destinations were it not for fear of nuclear winter and not finding sufficient food – and petrol to keep “the Lioness” (the replacement car they steal; it becomes their refuge) going. While the vague sexual tension between Harry and Ash persists, all three bonds are intriguing.

It gradually becomes clear that Harry, Ash and Jessie are among mere thousands of survivors worldwide, somehow immune to a novel disease that spread like wildfire. There are echoes of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road in the way that they ransack the homes of the dead for supplies, and yet there’s lightness to their journey. Jessie has a sharp sense of humour, provoking much banter, and the places they pass through in France and Italy are gorgeous despite the circumstances. It would be a privilege to wander empty tourist destinations were it not for fear of nuclear winter and not finding sufficient food – and petrol to keep “the Lioness” (the replacement car they steal; it becomes their refuge) going. While the vague sexual tension between Harry and Ash persists, all three bonds are intriguing.

In an alternating storyline starting in 2017, Lisa and Paul, two computer scientists based in a lab at the Arctic Circle, are programming an AI, Talos XI. Based on reams of data on history and human nature, Talos is asked to predict what will happen next. But when it comes to questions like the purpose of art and whether humans are worth saving, the conclusions he comes to aren’t the ones his creators were hoping for. These sections are set out as transcripts of dialogues, and provide a change of pace and perspective. Initially, I was less sure about this strand, worrying that it would resort to that well-worn trope of machines gone bad. Luckily, Aristide avoids sci-fi clichés, and presents a believable vision of life after the collapse of civilization.

The novel is full of memorable lines (“This absurd overkill, this baroque wedding cake of an apocalypse: plague and then nuclear meltdowns”) and scenes, from Harry burying a dead cow to the trio acting out a dinner party – just in case it’s their last. There’s an environmentalist message here, but it’s subtly conveyed via a propulsive cautionary tale that also reminded me of work by Louisa Hall and Maja Lunde. (Public library) ![]()

Ruby by Ann Hood (1998)

Olivia had the perfect life: fulfilling, creative work as a milliner; a place in New York City and a bolthole in Rhode Island; a new husband and plans to try for a baby right away. But then, in a fluke accident, David was hit by a car while jogging near their vacation home less than a year into their marriage. As the novel opens, 37-year-old Olivia is trying to formulate a letter to the college girl who struck and killed her husband. She has returned to Rhode Island to get the house ready to sell but changes her mind when a pregnant 15-year-old, Ruby, wanders in one day.

At first, I worried that the setup would be too neat: Olivia wants a baby but didn’t get a chance to have one with David before he died; Ruby didn’t intend to get pregnant and looks forward to getting back her figure and her life of soft drugs and petty crime. And indeed, Olivia suggests an adoption arrangement early on. But the outworkings of the plot are not straightforward, and the characters, both main and secondary (including Olivia’s magazine writer friend, Winnie; David’s friend, Rex; Olivia’s mother and sister; a local lawyer who becomes a love interest), are charming.

At first, I worried that the setup would be too neat: Olivia wants a baby but didn’t get a chance to have one with David before he died; Ruby didn’t intend to get pregnant and looks forward to getting back her figure and her life of soft drugs and petty crime. And indeed, Olivia suggests an adoption arrangement early on. But the outworkings of the plot are not straightforward, and the characters, both main and secondary (including Olivia’s magazine writer friend, Winnie; David’s friend, Rex; Olivia’s mother and sister; a local lawyer who becomes a love interest), are charming.

It’s a low-key, small-town affair reminiscent of the work of Anne Tyler, and I appreciated how it sensitively explores grief, its effects on the protagonist’s decision-making, and how daunting it is to start over (“The idea of that, of beginning again from nothing, made Olivia feel tired.”). It was also a neat touch that Olivia is the same age as me, so in some ways I could easily imagine myself into her position.

This was the ninth book I’ve read by Hood, an author little known outside of the USA – everything from grief memoirs to a novel about knitting. Ironically, its main themes of adoption and bereavement were to become hallmarks of her later work: she lost her daughter in 2002 and then adopted a little girl from China. (Secondhand purchase, June 2021) ![]()

[I’ve read another novel titled Ruby – Cynthia Bond’s from 2014.]

Blue Shoe by Anne Lamott (2002)

I’m a devoted reader of Lamott’s autobiographical essays about faith against the odds (see here), but have been wary of trying her fiction, suspecting I wouldn’t enjoy it as much. Well, it’s true that I prefer her nonfiction on the whole, but this was an enjoyably offbeat novel featuring the kind of frazzled antiheroine who wouldn’t be out of place in Anne Tyler’s work.

Mattie Ryder has left her husband and returned to her Bay Area family home with her young son and daughter. She promptly falls for Daniel, the handyman she hires to exterminate the rats, but he’s married, so she keeps falling into bed with her ex, Nicky, even after he acquires a new wife and baby. Her mother, Isa, is drifting ever further into dementia. A blue rubber shoe that Mattie finds serves as a totem of her late father – and his secret life. She takes a gamble that telling the truth, no matter what the circumstances, will see her right.

Mattie Ryder has left her husband and returned to her Bay Area family home with her young son and daughter. She promptly falls for Daniel, the handyman she hires to exterminate the rats, but he’s married, so she keeps falling into bed with her ex, Nicky, even after he acquires a new wife and baby. Her mother, Isa, is drifting ever further into dementia. A blue rubber shoe that Mattie finds serves as a totem of her late father – and his secret life. She takes a gamble that telling the truth, no matter what the circumstances, will see her right.

As in Ruby, I found the protagonist relatable and the ensemble cast of supporting characters amusing. Lamott crafts some memorable potted descriptions: “She was Jewish, expansive and yeasty and uncontained, as if she had a birthright for outrageousness” and “He seemed so constrained, so neatly trimmed, someone who’d been doing topiary with his soul all his life.” She turns a good phrase, and adopts the same self-deprecating attitude towards Mattie that she has towards herself in her memoirs: “She usually hoped to look more like Myrna Loy than an organ grinder’s monkey when a man finally proclaimed his adoration.”

At a certain point – maybe two-thirds of the way through – my inward reply to a lot of the novel’s threads was “okay, I get it; can we move on?” Yes, the situation with Isa is awful; yes, something’s gotta give with Daniel and his wife; yes, the revelations about her father seem unbearable. But with a four-year time span, it felt like Mattie was stuck in the middle for far too long. It’s also curious that she doesn’t apply her zany faith (a replica of Lamott’s) to questions of sexual morality – though that’s true of more liberal Christian approaches. All in all, I had some trouble valuing this as a novel because of how much I know about Lamott’s life and how closely I saw the storyline replicating her family dynamic. (Secondhand purchase, c. 2006 – I found a signed hardback in a library book sale back in my U.S. hometown for $1.) ![]()

Hmm, altogether too much blue in my selections thus far (4 out of 8!). I’ll have to try to come up with some more interesting colours for my upcoming choices.

Next books in progress: The Other’s Gold by Elizabeth Ames and God Is Not a White Man by Chine McDonald.

If only I’d realized this was set on a train to Berlin, I could have read it in the same situation! Instead, it was a random find while shelving in the children’s section of the library. Emil sets out on a slow train from Neustadt to stay with his aunt, grandmother and cousin in Berlin for a week’s holiday. His mother gives him £7 in an envelope he pins inside his coat for safekeeping. There are four adults in the carriage with him, but three get off early, leaving Emil alone with a man in a bowler hat. Much as he strives to stay awake, Emil drops off. No sooner has the train pulled into Berlin than he realizes the envelope is gone along with his fellow traveller. “There were four million people in Berlin at that moment, and not one of them cared what was happening to Emil Tischbein.” He’s sure he’ll have to chase the man in the bowler hat all by himself, but instead he enlists the help of a whole gang of boys, including Gustav who carries a motor-horn and poses as a bellhop, Professor with the glasses, and Little Tuesday who mans the phone lines. Together they get justice for Emil, deliver a wanted criminal to the police, and earn a hefty reward. This was a cute story and it was refreshing for children’s word to be taken seriously. There’s also the in-joke of the journalist who interviews Emil being Kästner. I’m sure as a kid I would have found this a thrilling adventure, but the cynical me of today deemed it unrealistic. (Public library) [153 pages]

If only I’d realized this was set on a train to Berlin, I could have read it in the same situation! Instead, it was a random find while shelving in the children’s section of the library. Emil sets out on a slow train from Neustadt to stay with his aunt, grandmother and cousin in Berlin for a week’s holiday. His mother gives him £7 in an envelope he pins inside his coat for safekeeping. There are four adults in the carriage with him, but three get off early, leaving Emil alone with a man in a bowler hat. Much as he strives to stay awake, Emil drops off. No sooner has the train pulled into Berlin than he realizes the envelope is gone along with his fellow traveller. “There were four million people in Berlin at that moment, and not one of them cared what was happening to Emil Tischbein.” He’s sure he’ll have to chase the man in the bowler hat all by himself, but instead he enlists the help of a whole gang of boys, including Gustav who carries a motor-horn and poses as a bellhop, Professor with the glasses, and Little Tuesday who mans the phone lines. Together they get justice for Emil, deliver a wanted criminal to the police, and earn a hefty reward. This was a cute story and it was refreshing for children’s word to be taken seriously. There’s also the in-joke of the journalist who interviews Emil being Kästner. I’m sure as a kid I would have found this a thrilling adventure, but the cynical me of today deemed it unrealistic. (Public library) [153 pages] I’ve been equally enchanted by Kehlmann’s historical fiction (

I’ve been equally enchanted by Kehlmann’s historical fiction ( This was longlisted for the International Booker Prize and is the current Waterstones book of the month. The Swiss author’s seventh novel appears to be autofiction: the protagonist is named Christian Kracht and there are references to his previous works. Whether he actually went on a profligate road trip with his 80-year-old mother, who could say. I tend to think some details might be drawn from life – her physical and mental health struggles, her father’s Nazism, his father’s weird collections and sexual predilections – but brewed into a madcap maelstrom of a plot that sees the pair literally throwing away thousands of francs. Her fortune was gained through arms industry investment and she wants rid of it, so they hire private taxis and planes. If his mother has a whim to pick some edelweiss, off they go to find it. All the while she swigs vodka and swallows pills, and Christian changes her colostomy bags. I was wowed by individual lines (“This was the katabasis: the decline of the family expressed in the topography of her face”; “everything that does not rise into consciousness will return as fate”; “the glacial sun shone from above, unceasing and relentless, upon our little tableau vivant”) but was left chilly overall by the satire on the ultra-wealthy and those who seek to airbrush history. The fun connections: Like the Kehlmann, this involves arbitrary travel and happens to end in Africa. More than once, Kracht is confused for Kehlmann. (Little Free Library) [190 pages]

This was longlisted for the International Booker Prize and is the current Waterstones book of the month. The Swiss author’s seventh novel appears to be autofiction: the protagonist is named Christian Kracht and there are references to his previous works. Whether he actually went on a profligate road trip with his 80-year-old mother, who could say. I tend to think some details might be drawn from life – her physical and mental health struggles, her father’s Nazism, his father’s weird collections and sexual predilections – but brewed into a madcap maelstrom of a plot that sees the pair literally throwing away thousands of francs. Her fortune was gained through arms industry investment and she wants rid of it, so they hire private taxis and planes. If his mother has a whim to pick some edelweiss, off they go to find it. All the while she swigs vodka and swallows pills, and Christian changes her colostomy bags. I was wowed by individual lines (“This was the katabasis: the decline of the family expressed in the topography of her face”; “everything that does not rise into consciousness will return as fate”; “the glacial sun shone from above, unceasing and relentless, upon our little tableau vivant”) but was left chilly overall by the satire on the ultra-wealthy and those who seek to airbrush history. The fun connections: Like the Kehlmann, this involves arbitrary travel and happens to end in Africa. More than once, Kracht is confused for Kehlmann. (Little Free Library) [190 pages]

Live Fast by Brigitte Giraud (trans. from the French by Cory Stockwell) [Feb. 11, Ecco]: I found out about this autofiction novella via an early

Live Fast by Brigitte Giraud (trans. from the French by Cory Stockwell) [Feb. 11, Ecco]: I found out about this autofiction novella via an early  The Unworthy by Agustina Bazterrica (trans. from the Spanish by Sarah Moses) [13 Feb., Pushkin; March 4, Scribner]: I wasn’t enamoured of the Argentinian author’s

The Unworthy by Agustina Bazterrica (trans. from the Spanish by Sarah Moses) [13 Feb., Pushkin; March 4, Scribner]: I wasn’t enamoured of the Argentinian author’s  Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito [13 Feb., Fourth Estate; Feb. 4, Liveright]: Feito’s debut,

Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito [13 Feb., Fourth Estate; Feb. 4, Liveright]: Feito’s debut,

The Swell by Kat Gordon [27 Feb., Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: I got vague The Mercies (Kiran Millwood Hargrave) vibes from the blurb. “Iceland, 1910. In the middle of a severe storm two sisters, Freyja and Gudrun, rescue a mysterious, charismatic man from a shipwreck near their remote farm. Sixty-five years later, a young woman, Sigga, is spending time with her grandmother when they learn a body has been discovered on a mountainside near Reykjavik, perfectly preserved in ice.” (NetGalley download)

The Swell by Kat Gordon [27 Feb., Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: I got vague The Mercies (Kiran Millwood Hargrave) vibes from the blurb. “Iceland, 1910. In the middle of a severe storm two sisters, Freyja and Gudrun, rescue a mysterious, charismatic man from a shipwreck near their remote farm. Sixty-five years later, a young woman, Sigga, is spending time with her grandmother when they learn a body has been discovered on a mountainside near Reykjavik, perfectly preserved in ice.” (NetGalley download) Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie [4 March, Fourth Estate/Knopf]: This is THE book I’m most looking forward to; I’ve read everything Adichie has published and Americanah was a 5-star read for me. So I did something I’ve never done before and pre-ordered the signed independent bookshop edition from my local indie, Hungerford Bookshop. “Chiamaka is a Nigerian travel writer living in America. Alone in the midst of the pandemic, she recalls her past lovers and grapples with her choices and regrets.” The focus is on four Nigerian American women “and their loves, longings, and desires.” (New purchase)

Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie [4 March, Fourth Estate/Knopf]: This is THE book I’m most looking forward to; I’ve read everything Adichie has published and Americanah was a 5-star read for me. So I did something I’ve never done before and pre-ordered the signed independent bookshop edition from my local indie, Hungerford Bookshop. “Chiamaka is a Nigerian travel writer living in America. Alone in the midst of the pandemic, she recalls her past lovers and grapples with her choices and regrets.” The focus is on four Nigerian American women “and their loves, longings, and desires.” (New purchase) Kate & Frida by Kim Fay [March 11, G.P. Putnam’s Sons]: “Frida Rodriguez arrives in Paris in 1991 … But then she writes to a bookshop in Seattle … A friendship begins that will redefine the person she wants to become. Seattle bookseller Kate Fair is transformed by Frida’s free spirit … [A] love letter to bookshops and booksellers, to the passion we bring to life in our twenties”. Sounds like a cross between The Paris Novel and 84 Charing Cross Road – could be fab; could be twee. We shall see! (Edelweiss download)

Kate & Frida by Kim Fay [March 11, G.P. Putnam’s Sons]: “Frida Rodriguez arrives in Paris in 1991 … But then she writes to a bookshop in Seattle … A friendship begins that will redefine the person she wants to become. Seattle bookseller Kate Fair is transformed by Frida’s free spirit … [A] love letter to bookshops and booksellers, to the passion we bring to life in our twenties”. Sounds like a cross between The Paris Novel and 84 Charing Cross Road – could be fab; could be twee. We shall see! (Edelweiss download) The Antidote by Karen Russell [13 March, Chatto & Windus (Penguin) / March 11, Knopf]: I love Russell’s

The Antidote by Karen Russell [13 March, Chatto & Windus (Penguin) / March 11, Knopf]: I love Russell’s  Elegy, Southwest by Madeleine Watts [13 March, ONE (Pushkin) / Feb. 18, Simon & Schuster]: Watts’s debut,

Elegy, Southwest by Madeleine Watts [13 March, ONE (Pushkin) / Feb. 18, Simon & Schuster]: Watts’s debut,  O Sinners! by Nicole Cuffy [March 18, One World (Random House)]: Cuffy’s

O Sinners! by Nicole Cuffy [March 18, One World (Random House)]: Cuffy’s  The Accidentals: Stories by Guadalupe Nettel (trans. from the Spanish by Rosalind Harvey) [10 April, Fitzcarraldo Editions / April 29, Bloomsbury]: I really enjoyed Nettel’s International Booker-shortlisted novel

The Accidentals: Stories by Guadalupe Nettel (trans. from the Spanish by Rosalind Harvey) [10 April, Fitzcarraldo Editions / April 29, Bloomsbury]: I really enjoyed Nettel’s International Booker-shortlisted novel  Ordinary Saints by Niamh Ni Mhaoileoin [24 April, Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: “Brought up in a devout household in Ireland, Jay is now living in London with her girlfriend, determined to live day to day and not think too much about either the future or the past. But when she learns that her beloved older brother, who died in a terrible accident, may be made into a Catholic saint, she realises she must at last confront her family, her childhood and herself.” Winner of the inaugural PFD Queer Fiction Prize and shortlisted for the Women’s Prize Discoveries Award.

Ordinary Saints by Niamh Ni Mhaoileoin [24 April, Manilla Press (Bonnier Books UK)]: “Brought up in a devout household in Ireland, Jay is now living in London with her girlfriend, determined to live day to day and not think too much about either the future or the past. But when she learns that her beloved older brother, who died in a terrible accident, may be made into a Catholic saint, she realises she must at last confront her family, her childhood and herself.” Winner of the inaugural PFD Queer Fiction Prize and shortlisted for the Women’s Prize Discoveries Award. Heartwood by Amity Gaige [1 May, Fleet / April 1, Simon & Schuster]: I loved Gaige’s

Heartwood by Amity Gaige [1 May, Fleet / April 1, Simon & Schuster]: I loved Gaige’s  Are You Happy?: Stories by Lori Ostlund [May 6, Astra House]: Ostlund is not so well known, especially outside the USA, but I enjoyed her debut novel,

Are You Happy?: Stories by Lori Ostlund [May 6, Astra House]: Ostlund is not so well known, especially outside the USA, but I enjoyed her debut novel,  Ripeness by Sarah Moss [22 May, Picador / Sept. 9, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Though I was disappointed by her last two novels, I’ll read anything Moss publishes and hope for a return to form. “It is the [19]60s and … Edith finds herself travelling to rural Italy … to see her sister, ballet dancer Lydia, through the final weeks of her pregnancy, help at the birth and then make a phone call which will seal this baby’s fate, and his mother’s.” Promises to be “about migration and new beginnings, and about what it is to have somewhere to belong.”

Ripeness by Sarah Moss [22 May, Picador / Sept. 9, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Though I was disappointed by her last two novels, I’ll read anything Moss publishes and hope for a return to form. “It is the [19]60s and … Edith finds herself travelling to rural Italy … to see her sister, ballet dancer Lydia, through the final weeks of her pregnancy, help at the birth and then make a phone call which will seal this baby’s fate, and his mother’s.” Promises to be “about migration and new beginnings, and about what it is to have somewhere to belong.” The Forgotten Sense: The New Science of Smell by Jonas Olofsson [Out now! 7 Jan., William Collins / Mariner]: Part of a planned deep dive into the senses. “Smell is … one of our most sensitive and refined senses; few other mammals surpass our ability to perceive scents in the animal kingdom. Yet, as the millions of people who lost their sense of smell during the COVID-19 pandemic can attest, we too often overlook its role in our overall health. … For readers of Bill Bryson and Steven Pinker”. (On order from library)

The Forgotten Sense: The New Science of Smell by Jonas Olofsson [Out now! 7 Jan., William Collins / Mariner]: Part of a planned deep dive into the senses. “Smell is … one of our most sensitive and refined senses; few other mammals surpass our ability to perceive scents in the animal kingdom. Yet, as the millions of people who lost their sense of smell during the COVID-19 pandemic can attest, we too often overlook its role in our overall health. … For readers of Bill Bryson and Steven Pinker”. (On order from library) Bread and Milk by Karolina Ramqvist (trans. from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel) [13 Feb., Bonnier Books / Feb. 11, Coach House Books]: I think I first found about this via the early

Bread and Milk by Karolina Ramqvist (trans. from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel) [13 Feb., Bonnier Books / Feb. 11, Coach House Books]: I think I first found about this via the early  My Mother in Havana: A Memoir of Magic & Miracle by Rebe Huntman [Feb. 18, Monkfish]: I found out about this from

My Mother in Havana: A Memoir of Magic & Miracle by Rebe Huntman [Feb. 18, Monkfish]: I found out about this from  Mother Animal by Helen Jukes [27 Feb., Elliott & Thompson]: This may be the 2025 release I’ve known about for the longest. I remember expressing interest the first time the author tweeted about it; it’s bound to be a good follow-up to Lucy Jones’s

Mother Animal by Helen Jukes [27 Feb., Elliott & Thompson]: This may be the 2025 release I’ve known about for the longest. I remember expressing interest the first time the author tweeted about it; it’s bound to be a good follow-up to Lucy Jones’s  Alive: An Alternative Anatomy by Gabriel Weston [6 March, Vintage (Penguin) / March 4, David R. Godine]: I’ve read Weston’s

Alive: An Alternative Anatomy by Gabriel Weston [6 March, Vintage (Penguin) / March 4, David R. Godine]: I’ve read Weston’s  The Lost Trees of Willow Avenue: A Story of Climate and Hope on One American Street by Mike Tidwell [March 25, St. Martin’s Press]: A must-read for me because it’s set in Takoma Park, Maryland, where I was born. “A love letter to the magnificent oaks and other trees dying from record heat waves and bizarre rain, [activist] Tidwell’s story depicts the neighborhood’s battle to save the trees and combat climate change. … Tidwell chronicles people on his block sick with Lyme disease, a church struggling with floods, and young people anguishing over whether to have kids, … against the global backdrop of 2023’s record heat domes and raging wildfires and hurricanes.”

The Lost Trees of Willow Avenue: A Story of Climate and Hope on One American Street by Mike Tidwell [March 25, St. Martin’s Press]: A must-read for me because it’s set in Takoma Park, Maryland, where I was born. “A love letter to the magnificent oaks and other trees dying from record heat waves and bizarre rain, [activist] Tidwell’s story depicts the neighborhood’s battle to save the trees and combat climate change. … Tidwell chronicles people on his block sick with Lyme disease, a church struggling with floods, and young people anguishing over whether to have kids, … against the global backdrop of 2023’s record heat domes and raging wildfires and hurricanes.” Breasts: A Relatively Brief Relationship by Jean Hannah Edelstein [3 April, Phoenix (W&N)]: I loved Edelstein’s 2018 memoir

Breasts: A Relatively Brief Relationship by Jean Hannah Edelstein [3 April, Phoenix (W&N)]: I loved Edelstein’s 2018 memoir  Poets Square: A Memoir in Thirty Cats by Courtney Gustafson [8 May, Fig Tree (Penguin) / April 29, Crown]: Gustafson became an Instagram and TikTok hit with her posts about looking after a feral cat colony in Tucson, Arizona. The money she raised via social media allowed her to buy her home and continue caring for animals. “[Gustafson] had no idea about the grief and hardship of animal rescue, the staggering size of the problem in neighborhoods across the country. And she couldn’t have imagined how that struggle … would help pierce a personal darkness she’d wrestled for with much of her life.” (Proof copy from publisher)

Poets Square: A Memoir in Thirty Cats by Courtney Gustafson [8 May, Fig Tree (Penguin) / April 29, Crown]: Gustafson became an Instagram and TikTok hit with her posts about looking after a feral cat colony in Tucson, Arizona. The money she raised via social media allowed her to buy her home and continue caring for animals. “[Gustafson] had no idea about the grief and hardship of animal rescue, the staggering size of the problem in neighborhoods across the country. And she couldn’t have imagined how that struggle … would help pierce a personal darkness she’d wrestled for with much of her life.” (Proof copy from publisher) Lifelines: Searching for Home in the Mountains of Greece by Julian Hoffman [15 May, Elliott & Thompson]: Hoffman’s

Lifelines: Searching for Home in the Mountains of Greece by Julian Hoffman [15 May, Elliott & Thompson]: Hoffman’s  Spent: A Comic Novel by Alison Bechdel [22 May, Jonathan Cape (Penguin) / May 20, Mariner Books]: Bechdel’s

Spent: A Comic Novel by Alison Bechdel [22 May, Jonathan Cape (Penguin) / May 20, Mariner Books]: Bechdel’s

Just the one cat, actually. (Ripoff!) But Fleabag, a one-eared stray ‘the colour of gone-off curry’ who just won’t leave, is a fine companion on this end-of-the-world Malaysian road trip. Mikail’s debut teen novel, which won the Waterstones Children’s Book Prize 2023, imagines that news has come of an asteroid that will make direct contact with Earth in one year. The clock is ticking; just nine months remain. Teenage Aisha and her boyfriend Walter have come to terms with the fact that they’ll never get to do all the things they want to, from attending university to marrying and having children.

Just the one cat, actually. (Ripoff!) But Fleabag, a one-eared stray ‘the colour of gone-off curry’ who just won’t leave, is a fine companion on this end-of-the-world Malaysian road trip. Mikail’s debut teen novel, which won the Waterstones Children’s Book Prize 2023, imagines that news has come of an asteroid that will make direct contact with Earth in one year. The clock is ticking; just nine months remain. Teenage Aisha and her boyfriend Walter have come to terms with the fact that they’ll never get to do all the things they want to, from attending university to marrying and having children. My second from Tangye. I’ve read from The Minack Chronicles out of order because I happened to find a free copy of

My second from Tangye. I’ve read from The Minack Chronicles out of order because I happened to find a free copy of  My seventh from Tovey. I can hardly believe that, having started her writing career in the 1950s, she was still publishing into the new millennium! (She lived 1918–2008.) Tovey was addicted to Siamese cats. As this volume opens, she’s so forlorn after the death of Saphra, her fourth male, that she instantly sets about finding a replacement. Although she sets strict criteria she doesn’t think can be met, Rama fits the bill and joins her and Tani, her nine-year-old female. They spar at first, but quickly settle into life together. As always, there are various mishaps involving mischievous cats and eccentric locals (I have a really low tolerance for accounts of folksy neighbours’ doings). The most persistent problem is Rama’s new habit of spraying.

My seventh from Tovey. I can hardly believe that, having started her writing career in the 1950s, she was still publishing into the new millennium! (She lived 1918–2008.) Tovey was addicted to Siamese cats. As this volume opens, she’s so forlorn after the death of Saphra, her fourth male, that she instantly sets about finding a replacement. Although she sets strict criteria she doesn’t think can be met, Rama fits the bill and joins her and Tani, her nine-year-old female. They spar at first, but quickly settle into life together. As always, there are various mishaps involving mischievous cats and eccentric locals (I have a really low tolerance for accounts of folksy neighbours’ doings). The most persistent problem is Rama’s new habit of spraying.

I knew Bergman from her second of three collections,

I knew Bergman from her second of three collections,  What a clever decision to open with “Lucky Chow Fun,” a story set in Templeton, the location of Groff’s

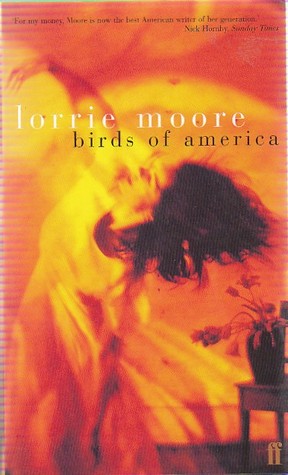

What a clever decision to open with “Lucky Chow Fun,” a story set in Templeton, the location of Groff’s  I’d read a few of Moore’s works before (A Gate at the Stairs, Bark, Who Will Run the Frog Hospital?) and not grasped what the fuss is about; turns out I’d just chosen the wrong ones to read. This collection is every bit as good as everyone has been saying for the last 25 years. Amy Bloom, Carol Shields and Helen Simpson are a few other authors who struck me as having a similar tone and themes. Rich with psychological understanding of her characters – many of them women passing from youth to midlife, contemplating or being affected by adultery – and their relationships, the stories are sometimes wry and sometimes wrenching (that setup to “Terrific Mother”!). There were even two dysfunctional-family-at-the-holidays ones (“Charades” and “Four Calling Birds, Three French Hens”) for me to read in December.

I’d read a few of Moore’s works before (A Gate at the Stairs, Bark, Who Will Run the Frog Hospital?) and not grasped what the fuss is about; turns out I’d just chosen the wrong ones to read. This collection is every bit as good as everyone has been saying for the last 25 years. Amy Bloom, Carol Shields and Helen Simpson are a few other authors who struck me as having a similar tone and themes. Rich with psychological understanding of her characters – many of them women passing from youth to midlife, contemplating or being affected by adultery – and their relationships, the stories are sometimes wry and sometimes wrenching (that setup to “Terrific Mother”!). There were even two dysfunctional-family-at-the-holidays ones (“Charades” and “Four Calling Birds, Three French Hens”) for me to read in December.