Recent Writing for BookBrowse, Shiny New Books and the TLS

A peek at the bylines I’ve had elsewhere so far this year.

BookBrowse

A Good Neighborhood by Therese Anne Fowler: In Fowler’s sixth novel, issues of race and privilege undermine a teen romance and lead to tragedy in a seemingly idyllic North Carolina neighborhood. A Good Neighborhood is an up-to-the-minute story packed with complex issues including celebrity culture, casual racism, sexual exploitation, and environmental degradation. It is narrated in a first-person plural voice, much like the Greek chorus of a classical tragedy. If you loved Tayari Jones’s An American Marriage, this needs to be next on your to-read list. It is a book that will make you think, and a book that will make you angry; I recommend it to socially engaged readers and book clubs alike.

A Good Neighborhood by Therese Anne Fowler: In Fowler’s sixth novel, issues of race and privilege undermine a teen romance and lead to tragedy in a seemingly idyllic North Carolina neighborhood. A Good Neighborhood is an up-to-the-minute story packed with complex issues including celebrity culture, casual racism, sexual exploitation, and environmental degradation. It is narrated in a first-person plural voice, much like the Greek chorus of a classical tragedy. If you loved Tayari Jones’s An American Marriage, this needs to be next on your to-read list. It is a book that will make you think, and a book that will make you angry; I recommend it to socially engaged readers and book clubs alike.

Pew by Catherine Lacey: Lacey’s third novel is a mysterious fable about a stranger showing up in a Southern town in the week before an annual ritual. Pew’s narrator, homeless, mute and amnesiac, wakes up one Sunday in the middle of a church service, observing everything like an alien anthropologist. The stranger’s gender, race, and age are entirely unclear, so the Reverend suggests the name “Pew”. The drama over deciphering Pew’s identity plays out against the preparations for the enigmatic Forgiveness Festival and increasing unrest over racially motivated disappearances. Troubling but strangely compelling; recommended to fans of Shirley Jackson and Flannery O’Connor. [U.S. publication pushed back to July 21st]

Pew by Catherine Lacey: Lacey’s third novel is a mysterious fable about a stranger showing up in a Southern town in the week before an annual ritual. Pew’s narrator, homeless, mute and amnesiac, wakes up one Sunday in the middle of a church service, observing everything like an alien anthropologist. The stranger’s gender, race, and age are entirely unclear, so the Reverend suggests the name “Pew”. The drama over deciphering Pew’s identity plays out against the preparations for the enigmatic Forgiveness Festival and increasing unrest over racially motivated disappearances. Troubling but strangely compelling; recommended to fans of Shirley Jackson and Flannery O’Connor. [U.S. publication pushed back to July 21st]

Shiny New Books

Losing Eden: Why Our Minds Need the Wild by Lucy Jones: While nature’s positive effect on human mental health is something we know intuitively and can explain anecdotally, Jones was determined to investigate the scientific mechanism behind it. She set out to make an empirical enquiry and discovered plenty of evidence in the scientific literature, but also attests to the personal benefits that nature has for her and explores the spiritual connection that many have found. Losing Eden is full of both common sense and passion, cramming masses of information into 200 pages yet never losing sight of the big picture. Just as Silent Spring led to real societal change, let’s hope Jones’s work inspires steps in the right direction.

Losing Eden: Why Our Minds Need the Wild by Lucy Jones: While nature’s positive effect on human mental health is something we know intuitively and can explain anecdotally, Jones was determined to investigate the scientific mechanism behind it. She set out to make an empirical enquiry and discovered plenty of evidence in the scientific literature, but also attests to the personal benefits that nature has for her and explores the spiritual connection that many have found. Losing Eden is full of both common sense and passion, cramming masses of information into 200 pages yet never losing sight of the big picture. Just as Silent Spring led to real societal change, let’s hope Jones’s work inspires steps in the right direction.

[+ Reviews of 4 more Wainwright Prize (for nature writing) longlistees on the way!]

The Bass Rock by Evie Wyld: While it ranges across the centuries, the novel always sticks close to the title location. Just as the louring rock is inescapable in the distance if you look out from the Edinburgh hills, there’s no avoiding violence for the women and children of the novel. It’s a sobering theme, certainly, but Wyld convinced me that hers is an accurate vision and a necessary mission. The novel cycles through its three strands in an ebb and flow pattern that seems appropriate to the coastal setting and creates a sense of time’s fluidity. The best 2020 novel I’ve read, memorable for its elegant, time-blending structure as well as its unrelenting course – and set against that perfect backdrop of an indifferent monolith.

The Bass Rock by Evie Wyld: While it ranges across the centuries, the novel always sticks close to the title location. Just as the louring rock is inescapable in the distance if you look out from the Edinburgh hills, there’s no avoiding violence for the women and children of the novel. It’s a sobering theme, certainly, but Wyld convinced me that hers is an accurate vision and a necessary mission. The novel cycles through its three strands in an ebb and flow pattern that seems appropriate to the coastal setting and creates a sense of time’s fluidity. The best 2020 novel I’ve read, memorable for its elegant, time-blending structure as well as its unrelenting course – and set against that perfect backdrop of an indifferent monolith.

Times Literary Supplement

I Am an Island by Tamsin Calidas: A record of a demoralizing journey into extreme loneliness on a Scottish island, this offers slivers of hope that mystical connection with the natural world can restore a sense of self. In places the narrative is a litany of tragedies and bad news. The story’s cathartic potential relies on its audience’s willingness to stick with a book that can be – to be blunt –depressing. The writing often tends towards the poetic, but is occasionally marred by platitudes and New Age sentiments. As with Educated, it’s impossible not to marvel at all the author has survived. Admiring Calidas’s toughness, though, doesn’t preclude relief at reaching the final page. (Full review in May 29th issue.)

I Am an Island by Tamsin Calidas: A record of a demoralizing journey into extreme loneliness on a Scottish island, this offers slivers of hope that mystical connection with the natural world can restore a sense of self. In places the narrative is a litany of tragedies and bad news. The story’s cathartic potential relies on its audience’s willingness to stick with a book that can be – to be blunt –depressing. The writing often tends towards the poetic, but is occasionally marred by platitudes and New Age sentiments. As with Educated, it’s impossible not to marvel at all the author has survived. Admiring Calidas’s toughness, though, doesn’t preclude relief at reaching the final page. (Full review in May 29th issue.)

We Swim to the Shark: Overcoming fear one fish at a time by Georgie Codd: Codd’s offbeat debut memoir chronicles her quest to conquer a phobia of sea creatures. Inspired by a friend’s experience of cognitive behavioral therapy to cure arachnophobia, she crafted a program of controlled exposure. She learned to scuba dive before a trip to New Zealand, returning via Thailand with an ultimate challenge in mind: her quarry was the whale shark, a creature even Jacques Cousteau only managed to sight twice. The book has a jolly, self-deprecating tone despite its exploration of danger and dread. A more directionless second half leads to diminished curiosity about whether that elusive whale shark will make an appearance. (Full review in a forthcoming issue.)

We Swim to the Shark: Overcoming fear one fish at a time by Georgie Codd: Codd’s offbeat debut memoir chronicles her quest to conquer a phobia of sea creatures. Inspired by a friend’s experience of cognitive behavioral therapy to cure arachnophobia, she crafted a program of controlled exposure. She learned to scuba dive before a trip to New Zealand, returning via Thailand with an ultimate challenge in mind: her quarry was the whale shark, a creature even Jacques Cousteau only managed to sight twice. The book has a jolly, self-deprecating tone despite its exploration of danger and dread. A more directionless second half leads to diminished curiosity about whether that elusive whale shark will make an appearance. (Full review in a forthcoming issue.)

Dottoressa: An American Doctor in Rome by Susan Levenstein: In the late 1970s, Levenstein moved from New York City to Rome with her Italian husband and set up a private medical practice catering to English-speaking expatriates. Her light-hearted yet trenchant memoir highlights the myriad contrasts between the United States and Italy revealed by their health care systems. Italy has a generous national health service, but it is perennially underfunded and plagued by corruption and inefficiency. The tone is conversational and even-handed. In the pandemic aftermath, though, Italian sloppiness and shortages no longer seem like harmless matters to shake one’s head over. (Full review coming up in June 19th issue.)

Dottoressa: An American Doctor in Rome by Susan Levenstein: In the late 1970s, Levenstein moved from New York City to Rome with her Italian husband and set up a private medical practice catering to English-speaking expatriates. Her light-hearted yet trenchant memoir highlights the myriad contrasts between the United States and Italy revealed by their health care systems. Italy has a generous national health service, but it is perennially underfunded and plagued by corruption and inefficiency. The tone is conversational and even-handed. In the pandemic aftermath, though, Italian sloppiness and shortages no longer seem like harmless matters to shake one’s head over. (Full review coming up in June 19th issue.)

Do any of these books (all by women, coincidentally) interest you?

Library Checkout and Other Late May Happenings

The libraries I use have extended their closure until at least the end of July, and my stockpile is dwindling. Will I have cleared the decks before we get too far into the summer? Stay tuned to find out…

Meanwhile, we took advantage of the fine weather by having a jaunt to the Sandleford Warren site where Watership Down opens. This circular countryside walk of nearly 8 miles, via Greenham Common and back, took me further from home yesterday than I’ve been in about 10 weeks. We didn’t see any rabbits, but we did see this gorgeous hare.

My husband keeps baking – what a shame! We were meant to be spending a few days in France with my mother last week, so we had some Breton treats anyway (savory crêpes and Far Breton, a custard and prune tart), and yesterday while I was napping he for no reason produced a blackberry frangipane tart.

The Hay Festival went digital this year, so I’ve been able to ‘attend’ for the first time ever. On Friday I had my first of three events: Steve Silberman interviewing Dara McAnulty about his Diary of a Young Naturalist, which I’ll be reviewing for Shiny New Books. He’s autistic, and an inspiring 16-year-old Greta Thunberg type. Next week I’ll see John Troyer on Thursday and Roman Krznaric on Saturday. All the talks are FREE, so see if anything catches your eye on the schedule link above.

The Hay Festival went digital this year, so I’ve been able to ‘attend’ for the first time ever. On Friday I had my first of three events: Steve Silberman interviewing Dara McAnulty about his Diary of a Young Naturalist, which I’ll be reviewing for Shiny New Books. He’s autistic, and an inspiring 16-year-old Greta Thunberg type. Next week I’ll see John Troyer on Thursday and Roman Krznaric on Saturday. All the talks are FREE, so see if anything catches your eye on the schedule link above.

In general, I’ve been spoiled with live events recently. Each week we watch the Bookshop Band’s Friday night lockdown concert on Facebook (there have actually been seven now); they’ve played a lot of old favorites as well as newer material that hasn’t been recorded or that I’ve never heard before. We’ve also been to a few live gigs from Edgelarks and Megson – helpfully, these three folk acts are all couples, so they can still perform together.

Today we’ll be watching the second installment of the Folk on Foot Front Room Festival (also through Facebook). We had a great time watching most of the first one on Easter Monday, and an encore has quickly been arranged. Last month’s show was a real who’s-who of British folk music. There are a few more acts we’re keen to see today. Again, it’s free, though they welcome donations to be split among the artists and charity. It runs 2‒10 p.m. (BST) today, which is 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. if you’re on the east coast of North America, so you have time to join in if you are stuck at home for the holiday.

Back to the library books…

What have you been reading from your local libraries? Feel free to use the image above and leave a link to your blog in the comments if you’ve taken part, and/or tag me on Twitter (@bookishbeck / #TheLibraryCheckout).

READ

Parable of the Sower by Octavia E. Butler

Parable of the Sower by Octavia E. Butler

- Love Medicine by Louise Erdrich

- Oleander, Jacaranda by Penelope Lively

- Bodies in Motion and at Rest by Thomas Lynch

- Fugitive Pieces by Anne Michaels

SKIMMED

- Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl

CURRENTLY READING

CURRENTLY READING

- Reading with Patrick: A teacher, a student and the life-changing power of books by Michelle Kuo [set aside temporarily]

- Meet the Austins by Madeleine L’Engle [set aside temporarily]

- Property by Valerie Martin

CURRENTLY SKIMMING

- My Own Country by Abraham Verghese

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

The Song of the Lark by Willa Cather

The Song of the Lark by Willa Cather- Owls Do Cry by Janet Frame

- The Trick Is to Keep Breathing by Janice Galloway

- When I Lived in Modern Times by Linda Grant

- Becoming a Man by Paul Monette

- Woman on the Edge of Time by Marge Piercy

- Golden Boy by Abigail Tarttelin

ON HOLD, TO BE PICKED UP

- The Girl with the Louding Voice by Abi Daré

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

Queenie by Candice Carty-Williams

Queenie by Candice Carty-Williams- Can You Hear Me? A Paramedic’s Encounters with Life and Death by Jake Jones

- The Most Fun We Ever Had by Claire Lombardo

- Guest House for Young Widows: Among the Women of ISIS by Azadeh Moaveni

- The Accidental Countryside by Stephen Moss

- Redhead by the Side of the Road by Anne Tyler

Have you run out of library books yet?

How have you been passing these May days?

Recapping the Not the Wellcome Prize Blog Tour Reviews

It’s hard to believe the Not the Wellcome Prize blog tour is over already! It has been a good two weeks of showcasing some of the best medicine- and health-themed books published in 2019. We had some kind messages of thanks from the authors, and good engagement on Twitter, including from publishers and employees of the Wellcome Trust. Thanks to the bloggers involved in the tour, and others who have helped us with comments and retweets.

This weekend we as the shadow panel (Annabel of Annabookbel, Clare of A Little Blog of Books, Laura of Dr. Laura Tisdall, Paul of Halfman, Halfbook and I) have the tough job of choosing a shortlist of six books, which we will announce on Monday morning. I plan to set up a Twitter poll to run all through next week. The shadow panel members will vote to choose a winner, with the results of the Twitter poll serving as one additional vote. The winner will be announced a week later, on Monday the 11th.

First, here’s a recap of the 19 terrific books we’ve featured, in chronological blog tour order. In fiction we’ve got: novels about child development, memory loss, and disturbed mental states; science fiction about AI and human identity; and a graphic novel set at a small-town medical practice. In nonfiction the topics included: anatomy, cancer, chronic pain, circadian rhythms, consciousness, disability, gender inequality, genetic engineering, premature birth, sleep, and surgery in war zones. I’ve also appended positive review coverage I’ve come across elsewhere, and noted any other awards these books have won or been nominated for. (And see this post for a reminder of the other 56 books we considered this year through our mega-longlist.)

Notes Made While Falling by Jenn Ashworth & The Remarkable Life of the Skin by Monty Lyman: Simon’s reviews

Notes Made While Falling by Jenn Ashworth & The Remarkable Life of the Skin by Monty Lyman: Simon’s reviews

*Monty Lyman was shortlisted for the 2019 Royal Society Science Book Prize.

[Bookish Beck review of the Ashworth]

[Halfman, Halfbook review of the Lyman]

Exhalation by Ted Chiang & A Good Enough Mother by Bev Thomas: Laura’s reviews

Constellations by Sinéad Gleeson & War Doctor by David Nott: Jackie’s reviews

Constellations by Sinéad Gleeson & War Doctor by David Nott: Jackie’s reviews

*Sinéad Gleeson was shortlisted for the 2020 Rathbones Folio Prize.

[Rebecca’s Goodreads review of the Gleeson]

[Kate Vane’s review of the Gleeson]

[Lonesome Reader review of the Gleeson]

[Rebecca’s Shiny New Books review of the Nott]

Vagina: A Re-education by Lynn Enright: Hayley’s Shiny New Books review

Galileo’s Error by Philip Goff: Peter’s Shiny New Books review

Mother Ship by Francesca Segal & The Lady Doctor by Ian Williams: Rebecca’s reviews

Mother Ship by Francesca Segal & The Lady Doctor by Ian Williams: Rebecca’s reviews

[A Little Blog of Books review of the Segal]

[Annabookbel review of the Williams]

Chasing the Sun by Linda Geddes & The Nocturnal Brain by Guy Leschziner: Paul’s reviews

[Bookish Beck review of the Geddes]

Invisible Women by Caroline Criado-Pérez: Katie’s review

Invisible Women by Caroline Criado-Pérez: Katie’s review

*Caroline Criado-Pérez won the 2019 Royal Society Science Book Prize.

[Liz’s Shiny New Books review]

The Faculty of Dreams by Sara Stridsberg: Kate’s review

Machines Like Me by Ian McEwan: Kate’s review

Hacking Darwin by Jamie Metzl & The Memory Police by Yoko Ogawa: Annabel’s reviews

Hacking Darwin by Jamie Metzl & The Memory Police by Yoko Ogawa: Annabel’s reviews

*Yoko Ogawa is shortlisted for this year’s International Booker Prize.

[Lonesome Reader review of the Ogawa]

The Body by Bill Bryson & The World I Fell Out Of by Melanie Reid: Clare’s reviews

The Body by Bill Bryson & The World I Fell Out Of by Melanie Reid: Clare’s reviews

[Bookish Beck review of the Bryson]

[Rebecca’s Goodreads review of the Reid]

And there we have it: the Not the Wellcome Prize longlist. I hope you’ve enjoyed following along with the reviews. Look out for the shortlist, and your chance to vote for the winner, here and via Twitter on Monday.

Which book(s) are you rooting for?

Reviews for Shiny New Books & TLS, Plus Simon’s “My Life in Books”

I recently participated in the one-week “My Life in Books” extravaganza hosted by Simon Thomas (Stuck in a Book), where he asks bloggers to choose five books that have been important to them at different points in their reading lives. The neat twist is that he puts the bloggers in pairs and asks them to comment anonymously on their partner’s reading choices and even come up with an apt book recommendation or two. A few of my selections will be familiar from the two Landmark Books posts I wrote in 2016 (here and here), but a couple are new, and it was fun to think about what’s changed versus what’s endured in my reading taste.

Shiny New Books

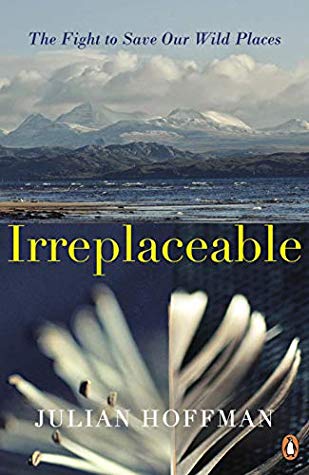

Irreplaceable by Julian Hoffman: If you read one 2019 release, make it this one. (It’s too important a book to dilute that statement with qualifiers.) Species and habitat loss are hard to comprehend even when we know the facts. This book is a way of taking stock, taking responsibility, and going beyond the numbers to tell the stories of front-line conservation work. From the Kent marshes to the Coral Triangle off Indonesia, Hoffman discovers the situation on the ground and talks to the people involved in protecting places at risk of destruction. Reassuringly, these aren’t usually genius scientists or well-funded heroes, but ordinary citizens who are concerned about preserving nearby sites that mean something to them. Irreplaceable is an elegy of sorts, but, more importantly, it’s a call to arms. It places environmentalism in the hands of laypeople and offers hope that in working together in the spirit of defiance we can achieve great things. It takes local concerns seriously, yet its scope is international. But what truly lifts Hoffman’s work above most recent nature books is the exquisite prose.

Irreplaceable by Julian Hoffman: If you read one 2019 release, make it this one. (It’s too important a book to dilute that statement with qualifiers.) Species and habitat loss are hard to comprehend even when we know the facts. This book is a way of taking stock, taking responsibility, and going beyond the numbers to tell the stories of front-line conservation work. From the Kent marshes to the Coral Triangle off Indonesia, Hoffman discovers the situation on the ground and talks to the people involved in protecting places at risk of destruction. Reassuringly, these aren’t usually genius scientists or well-funded heroes, but ordinary citizens who are concerned about preserving nearby sites that mean something to them. Irreplaceable is an elegy of sorts, but, more importantly, it’s a call to arms. It places environmentalism in the hands of laypeople and offers hope that in working together in the spirit of defiance we can achieve great things. It takes local concerns seriously, yet its scope is international. But what truly lifts Hoffman’s work above most recent nature books is the exquisite prose.

Times Literary Supplement

These three reviews are forthcoming.

The Heat of the Moment: Life and Death Decision-Making from a Firefighter by Sabrina Cohen-Hatton: Cohen-Hatton is one of the UK’s highest-ranking female firefighters. A few perilous situations inspired her to investigate how people make decisions under pressure. For a PhD in Psychology from Cardiff University, she delved into the neurology of decision-making. Although there is jargon in the book, she explains the terms well and uses relatable metaphors. However, the context about her research can be repetitive and basic, as if dumbed down for a general reader. The book shines when giving blow-by-blow accounts of real-life or composite incidents. Potential readers should bear in mind, though, that this is ultimately more of a management psychology book than a memoir.

The Heat of the Moment: Life and Death Decision-Making from a Firefighter by Sabrina Cohen-Hatton: Cohen-Hatton is one of the UK’s highest-ranking female firefighters. A few perilous situations inspired her to investigate how people make decisions under pressure. For a PhD in Psychology from Cardiff University, she delved into the neurology of decision-making. Although there is jargon in the book, she explains the terms well and uses relatable metaphors. However, the context about her research can be repetitive and basic, as if dumbed down for a general reader. The book shines when giving blow-by-blow accounts of real-life or composite incidents. Potential readers should bear in mind, though, that this is ultimately more of a management psychology book than a memoir.

Henry David Thoreau’s Walden (1854), a record of his two-year experiment living alone in a cabin near a Massachusetts pond, has inspired innumerable back-to-nature adventures, including these two books I discuss together in a longer article.

The Outermost House: A Year of Life on the Great Beach of Cape Cod by Henry Beston: Beston had a two-room wooden shack built at Cape Cod in 1925. Although he only intended to spend a fortnight of the following summer in the sixteen-by-twenty-foot dwelling, he stayed a year. The chronicle of that year, The Outermost House (originally published in 1928 and previously out of print in the UK), is a charming meditation on the turning of the seasons and the sometimes terrifying power of the sea. The writing is often poetic, with sibilance conjuring the sound of the ocean. Beston will be remembered for his statement of the proper relationship between humans and the natural world. “We need another and a wiser and perhaps a more mystical concept of animals,” he declares; “they are not underlings; they are other nations.” One word stands out in The Outermost House: “elemental” appears a dozen times, evoking the grandeur of nature and the necessity of getting back to life’s basics.

The Outermost House: A Year of Life on the Great Beach of Cape Cod by Henry Beston: Beston had a two-room wooden shack built at Cape Cod in 1925. Although he only intended to spend a fortnight of the following summer in the sixteen-by-twenty-foot dwelling, he stayed a year. The chronicle of that year, The Outermost House (originally published in 1928 and previously out of print in the UK), is a charming meditation on the turning of the seasons and the sometimes terrifying power of the sea. The writing is often poetic, with sibilance conjuring the sound of the ocean. Beston will be remembered for his statement of the proper relationship between humans and the natural world. “We need another and a wiser and perhaps a more mystical concept of animals,” he declares; “they are not underlings; they are other nations.” One word stands out in The Outermost House: “elemental” appears a dozen times, evoking the grandeur of nature and the necessity of getting back to life’s basics.

(See also Susan’s review of this one.)

Homesick: Why I Live in a Shed by Catrina Davies: Davies crosses Thoreauvian language – many chapter titles and epigraphs are borrowed from Walden – with a Woolfian search for a room of her own. Penniless during an ongoing housing crisis and reeling from a series of precarious living situations, she moved into the shed near Land’s End that had served as her father’s architecture office until he went bankrupt. Like Raynor Winn’s The Salt Path, this intimate, engaging memoir is a sobering reminder that homelessness is not so remote, and education is no guarantee of success. There is, understandably, a sense of righteous indignation here against a land-owning class – including the lord who owns much of the area where she lives and works – and government policies that favour the wealthy.

Homesick: Why I Live in a Shed by Catrina Davies: Davies crosses Thoreauvian language – many chapter titles and epigraphs are borrowed from Walden – with a Woolfian search for a room of her own. Penniless during an ongoing housing crisis and reeling from a series of precarious living situations, she moved into the shed near Land’s End that had served as her father’s architecture office until he went bankrupt. Like Raynor Winn’s The Salt Path, this intimate, engaging memoir is a sobering reminder that homelessness is not so remote, and education is no guarantee of success. There is, understandably, a sense of righteous indignation here against a land-owning class – including the lord who owns much of the area where she lives and works – and government policies that favour the wealthy.

Too Male! (A Few Recent Reviews for Shiny New Books and TLS)

I tend to wear my feminism lightly; you won’t ever hear me railing about the patriarchy or the male gaze. But there have been five reads so far this year that had me shaking my head and muttering, “too male!” While aspects of these books were interesting, the macho attitude or near-complete dearth of women irked me. Two of them I’ve already written about here: Ernest Hemingway’s The Garden of Eden was a previous month’s classic and book club selection, while Chip Cheek’s Cape May was part of my reading in America. The other three I reviewed for Shiny New Books or the Times Literary Supplement; I give excerpts below, with links to visit the full reviews in two cases, plus ideas for a book or two by a woman that should help neutralize the bad taste these might leave.

Shiny New Books

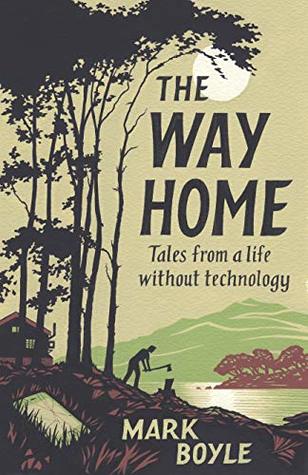

The Way Home: Tales from a Life without Technology by Mark Boyle

Boyle lives without electricity in a wooden cabin on a smallholding in County Galway, Ireland. He speaks of technology as an addiction and letting go of it as a detoxification process. For him it was a gradual shift that took place at the same time as he was moving away from modern conveniences. The Way Home is split into seasonal sections in which the author’s past and present intermingle. The writing consciously echoes Henry David Thoreau’s. Without even considering the privilege that got Boyle to the point where he could undertake this experiment, though, there are a couple of problems with this particular back-to-nature model. One is that it is a very male enterprise. Another is that Boyle doesn’t really have the literary chops to add much to the canon. Few of us could do what he has done, whether because of medical challenges, a lack of hands-on skills or family commitments. Still, the book is worth engaging with. It forces you to question your reliance on technology and ask whether making life easier is really a valuable goal.

Boyle lives without electricity in a wooden cabin on a smallholding in County Galway, Ireland. He speaks of technology as an addiction and letting go of it as a detoxification process. For him it was a gradual shift that took place at the same time as he was moving away from modern conveniences. The Way Home is split into seasonal sections in which the author’s past and present intermingle. The writing consciously echoes Henry David Thoreau’s. Without even considering the privilege that got Boyle to the point where he could undertake this experiment, though, there are a couple of problems with this particular back-to-nature model. One is that it is a very male enterprise. Another is that Boyle doesn’t really have the literary chops to add much to the canon. Few of us could do what he has done, whether because of medical challenges, a lack of hands-on skills or family commitments. Still, the book is worth engaging with. It forces you to question your reliance on technology and ask whether making life easier is really a valuable goal.

The Remedy: Homesick: Why I Live in a Shed by Catrina Davies, which I’m currently reading for a TLS review. Davies crosses Boyle’s Thoreauvian language about solitude and a place in nature with a Woolfian search for a room of her own. Penniless during the ongoing housing crisis, she moves into the shed near Land’s End that once served as her father’s architecture office and embarks on turning it into a home.

The Remedy: Homesick: Why I Live in a Shed by Catrina Davies, which I’m currently reading for a TLS review. Davies crosses Boyle’s Thoreauvian language about solitude and a place in nature with a Woolfian search for a room of her own. Penniless during the ongoing housing crisis, she moves into the shed near Land’s End that once served as her father’s architecture office and embarks on turning it into a home.

Doggerland by Ben Smith

This debut novel has just two main characters: ‘the old man’ and ‘the boy’ (who’s not really a boy anymore), who are stationed on an enormous offshore wind farm. The distance from the present day is indicated in slyly throwaway comments like “The boy didn’t know what potatoes were.” Smith poses questions about responsibility and sacrifice, and comments on modern addictions and a culture of disposability. He has certainly captured something of the British literary zeitgeist. From page to page, though, Doggerland grew tiresome for me. There is a lot of maritime vocabulary and technical detail about supplies and maintenance. The location is vague and claustrophobic, the pace is usually slow, and there are repetitive scenes and few conversations. To an extent, this comes with the territory. But it cannot be ignored that this is an entirely male world. Fans of the themes and style of The Old Man and the Sea and The Road will get on best with Smith’s writing. I most appreciated the moments of Beckettian humor in the dialogue and the poetic interludes that represent human history as a blip in the grand scheme of things.

This debut novel has just two main characters: ‘the old man’ and ‘the boy’ (who’s not really a boy anymore), who are stationed on an enormous offshore wind farm. The distance from the present day is indicated in slyly throwaway comments like “The boy didn’t know what potatoes were.” Smith poses questions about responsibility and sacrifice, and comments on modern addictions and a culture of disposability. He has certainly captured something of the British literary zeitgeist. From page to page, though, Doggerland grew tiresome for me. There is a lot of maritime vocabulary and technical detail about supplies and maintenance. The location is vague and claustrophobic, the pace is usually slow, and there are repetitive scenes and few conversations. To an extent, this comes with the territory. But it cannot be ignored that this is an entirely male world. Fans of the themes and style of The Old Man and the Sea and The Road will get on best with Smith’s writing. I most appreciated the moments of Beckettian humor in the dialogue and the poetic interludes that represent human history as a blip in the grand scheme of things.

The Remedy: I’m not a big fan of dystopian or post-apocalyptic fiction in general, but a couple of the best such novels that I’ve read by women are Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel and Gold Fame Citrus by Claire Vaye Watkins.

The Remedy: I’m not a big fan of dystopian or post-apocalyptic fiction in general, but a couple of the best such novels that I’ve read by women are Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel and Gold Fame Citrus by Claire Vaye Watkins.

Times Literary Supplement

The Knife’s Edge: The Heart and Mind of a Cardiac Surgeon by Stephen Westaby

In this somewhat tepid follow-up to Fragile Lives, Westaby’s bravado leaves a bad taste and dilutes the work’s ostensibly confessional nature. He has a good excuse, he argues: a head injury incurred while playing rugby in medical school transformed him into a risk taker. It’s widely accepted that such boldness may be a boon in a discipline that requires quick thinking and decisive action. So perhaps it’s no great problem to have a psychopath as your surgeon. But how about a sexist? Westaby’s persistent references to women staff as “lady GP” and “registrar lady” don’t mitigate surgeons’ macho reputation. It’s a shame to observe such casual sexism, because it’s clear Westaby felt deeply for his patients of any gender. And yet any talk of empathy earns his derision. It seems the specific language of compassion is a roadblock for him. The book is strongest when the author recreates dramatic sequences based on several risky surgeries. Alas, at its close he sounds bitter, and the NHS bears the brunt of his anger. Compared to Fragile Lives, one of my favorite books of 2017, this gives the superhero surgeon feet of clay. But it’s a lot less pleasing to read. (Forthcoming in TLS.)

In this somewhat tepid follow-up to Fragile Lives, Westaby’s bravado leaves a bad taste and dilutes the work’s ostensibly confessional nature. He has a good excuse, he argues: a head injury incurred while playing rugby in medical school transformed him into a risk taker. It’s widely accepted that such boldness may be a boon in a discipline that requires quick thinking and decisive action. So perhaps it’s no great problem to have a psychopath as your surgeon. But how about a sexist? Westaby’s persistent references to women staff as “lady GP” and “registrar lady” don’t mitigate surgeons’ macho reputation. It’s a shame to observe such casual sexism, because it’s clear Westaby felt deeply for his patients of any gender. And yet any talk of empathy earns his derision. It seems the specific language of compassion is a roadblock for him. The book is strongest when the author recreates dramatic sequences based on several risky surgeries. Alas, at its close he sounds bitter, and the NHS bears the brunt of his anger. Compared to Fragile Lives, one of my favorite books of 2017, this gives the superhero surgeon feet of clay. But it’s a lot less pleasing to read. (Forthcoming in TLS.)

The Remedy: I’m keen to read Direct Red by Gabriel Weston, a memoir by a female surgeon.

The Remedy: I’m keen to read Direct Red by Gabriel Weston, a memoir by a female surgeon.

(Crikey! This was my 600th blog post.)

Under the Rock by Benjamin Myers: Paperback Giveaway

Benjamin Myers’s Under the Rock was my nonfiction book of 2018, so I’m delighted to be kicking off the blog tour for its paperback release on the 25th (with a new subtitle, “Stories Carved from the Land”). I’m reprinting my Shiny New Books review below, with permission, and on behalf of Elliott & Thompson I am also hosting a giveaway of a copy of the paperback. Leave a comment saying that you’d like to win and I will choose one entry at random at the end of the day on Tuesday the 30th. (Sorry, UK only.)

My review:

Benjamin Myers has been having a bit of a moment. In 2017 Bluemoose Books published his fifth novel, The Gallows Pole, which went on to win the Roger Deakin Award and the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction and is now on its fourth printing. This taste of fame has brought renewed attention to his earlier work, including Beastings (2014), recipient of the Northern Writers’ Award. I’ve been interested in Myers’s work ever since I read an extract from the then-unpublished The Gallows Pole in Autumn, the Wildlife Trusts anthology edited by Melissa Harrison, but this is the first of his books that I’ve managed to read.

“Unremarkable places are made remarkable by the minds that map them,” Myers writes, and that is certainly true of Scout Rock, a landmark overlooking Mytholmroyd, near where the author lives in the Calder Valley of West Yorkshire. When he moved up there from London over a decade ago, he and his wife lived in a rental cottage built in 1640. He approached his new patch with admirable curiosity, and supplemented the observations he made from his study window with frequent long walks with his dog, Heathcliff (“Walking is writing with your feet”), and research into the history of the area. The result is a divagating, lyrical book that ranges from geology to true crime but has an underlying autobiographical vein.

Ted Hughes was born nearby, the Brontës not that much further away, and Hebden Bridge, in particular, has become a bastion of avant-garde artists and musicians. Myers also gets plenty of mileage out of his eccentric neighbours and postman. It’s a town that seems to attract oddballs and renegades, from the vigilantes who poisoned the fishing hole to an overdose victim who turns up beneath a stand of Himalayan balsam. A strange preponderance of criminals has come from the region, too, including sexual offenders like Jimmy Savile and serial killers such as the Yorkshire Ripper and Harold Shipman (‘Doctor Death’).

On his walks Myers discovers the old town tip, still full of junk that won’t biodegrade for hundreds more years, and finds traces of the asbestos that was dumped by Acre Mill, creating a national scandal. This isn’t old-style nature writing in search of a few remaining unspoiled places. Instead, it’s part of a growing literary interest in the ‘edgelands’ between settlement and the wild – places where the human impact is undeniable but nature is creeping back in. (Other recent examples would be Common Ground by Rob Cowen, Landfill by Tim Dee, Edgelands by Paul Farley and Michael Symmons Roberts, and Outskirts by John Grindrod.)

Under the Rock gives a keen sense of the seasons’ change and the seemingly inevitable melancholy that accompanies bad weather. A winter of non-stop rain left Myers nigh on delirious with flu; Storm Eva caused the Calder River to flood. He was a part of the effort to rescue trapped pensioners. Heartening as it is to see how the disaster brought people together – Sikh and Muslim charities and Syrian refugees were among the first to help – looting also resulted. One of the most remarkable things about this book is how Myers takes in such extremes of behaviour, along with mundanities, and makes them all part of a tapestry of life.

The book’s recurring themes tangle through all of the sections, even though it has been given a somewhat arbitrary four-part structure (Wood – Earth – Water – Rock). Interludes between these major parts transcribe Myers’s field notes, which are more like impromptu poems that he wrote in a notebook kept in his coat pocket. The artistry of these snippets of poetry is incredible given that they were written in situ, and their alliteration bleeds into his prose as well. My favourite of the poems was “On Lighting the First Fire”:

Autumn burns

the sky

the woods

the valley

death is everywhere

but beneath

the golden cloak

the seeds of

a summer’s

dreaming still sing.

The Field Notes sections are illustrated with Myers’s own photographs, which, again, are of enviable quality. I came away from this feeling like Myers could write anything – a thank-you note, a shopping list – and make it read as profound literature. Every sentence is well-crafted and memorable. There is also a wonderful sense of rhythm to his pages, with a pithy sentence appearing every couple of paragraphs to jolt you to attention.

“Writing is a form of alchemy,” Myers declares. “It’s a spell, and the writer is the magician.” I certainly fell under the author’s spell here. While his eyes are open to the many distressing political and environmental changes of the last few years, the ancient perspective of the Rock reminds him that, though humans are ultimately insignificant and individual lives are short, we can still rejoice in our experiences of the world’s beauty while we’re here.

From the publisher:

“Benjamin Myers was born in Durham in 1976. He is a prize-winning author, journalist and poet. His recent novels are each set in a different county of northern England, and are heavily inspired by rural landscapes, mythology, marginalised characters, morality, class, nature, dialect and post-industrialisation. They include The Gallows Pole, winner of the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction, and recipient of the Roger Deakin Award; Turning Blue, 2016; Beastings, 2014 (Portico Prize for Literature & Northern Writers’ Award winner), Pig Iron, 2012 (Gordon Burn Prize winner & Guardian Not the Booker Prize runner-up); and Richard, a Sunday Times Book of the Year 2010. Bloomsbury will publish his new novel, The Offing, in August 2019.

As a journalist, he has written widely about music, arts and nature. He lives in the Upper Calder Valley, West Yorkshire, the inspiration for Under the Rock.”

Recent Bylines: Glamour, Shiny New Books, Etc.

Following up on my post from June, here are excerpts from and links to some of my recent online writing for places that aren’t my blog.

Review essay of Gross Anatomy by Mara Altman for Glamour UK

The female body has been a source of deep embarrassment for Altman, but here she swaps shame for self-deprecating silliness and cringing for chuckling. Through a snappy blend of personal anecdotes and intensive research, she exposes the cultural expectations that make us dislike our bodies, suggesting that a better knowledge of anatomy might help us feel normal. While 11 of her 15 topics aren’t exclusive to women’s anatomy—birthmarks, hemorrhoids, warts and more apply to men, too—she always presents an honest account of the female experience. This is one of my favorite books of the year and one I’d recommend to women of any age. It’s funny, it’s feminist, and it’s a cracking good read. (My full review is complete with embarrassing personal revelations!)

The female body has been a source of deep embarrassment for Altman, but here she swaps shame for self-deprecating silliness and cringing for chuckling. Through a snappy blend of personal anecdotes and intensive research, she exposes the cultural expectations that make us dislike our bodies, suggesting that a better knowledge of anatomy might help us feel normal. While 11 of her 15 topics aren’t exclusive to women’s anatomy—birthmarks, hemorrhoids, warts and more apply to men, too—she always presents an honest account of the female experience. This is one of my favorite books of the year and one I’d recommend to women of any age. It’s funny, it’s feminist, and it’s a cracking good read. (My full review is complete with embarrassing personal revelations!)

Essay on two books about “wasting time” for the Los Angeles Review of Books

In Praise of Wasting Time by Alan Lightman  &

&

The Art of the Wasted Day by Patricia Hampl: A poet’s delight in lyricism and free association is in evidence here. The book blends memoir with travel and biographical information about some of Hampl’s exemplars of solitary, introspective living, and it begins, quite literally, with daydreaming.

The Art of the Wasted Day by Patricia Hampl: A poet’s delight in lyricism and free association is in evidence here. The book blends memoir with travel and biographical information about some of Hampl’s exemplars of solitary, introspective living, and it begins, quite literally, with daydreaming.

Hampl and Lightman start from the same point of frazzled frustration and arrive at many of the same conclusions about the necessity of “wasted” time but go about it in entirely different ways. Lightman makes a carefully constructed argument and amasses a sufficient weight of scientific and anecdotal evidence; Hampl drifts and dreams through seemingly irrelevant back alleys of memory and experience. The latter is a case of form following function: her book wanders along with her mind, in keeping with her definition of memoir as “lyrical quest literature,” where meaning always hovers above the basics of plot.

Hampl and Lightman start from the same point of frazzled frustration and arrive at many of the same conclusions about the necessity of “wasted” time but go about it in entirely different ways. Lightman makes a carefully constructed argument and amasses a sufficient weight of scientific and anecdotal evidence; Hampl drifts and dreams through seemingly irrelevant back alleys of memory and experience. The latter is a case of form following function: her book wanders along with her mind, in keeping with her definition of memoir as “lyrical quest literature,” where meaning always hovers above the basics of plot.

Book list for OZY on the refugee crisis & another coming up on compassion in medicine.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reviews

(Their website is not available outside the USA, so the links may not work for you).

Slave Old Man by Patrick Chamoiseau

Chamoiseau is a social worker and author from the Caribbean island of Martinique. Translator Linda Coverdale has chosen to leave snippets of Martinican Creole in this text, creating a symphony of languages. The novel has an opening that might suit a gloomy fairytale: “In slavery times in the sugar isles, once there was an old black man.” The novel’s language is full of delightfully unexpected verbs and metaphors. At not much more than 100 pages, it is a nightmarish novella that alternates between feeling like a nebulous allegory and a realistic escaped slave narrative. It can be a disorienting experience: like the slave, readers are trapped in a menacing forest and prone to hallucinations. The lyricism of the writing and the brief glimpse back from the present day, in which an anthropologist discovers the slave’s remains and imagines the runaway back into life, give this book enduring power.

Chamoiseau is a social worker and author from the Caribbean island of Martinique. Translator Linda Coverdale has chosen to leave snippets of Martinican Creole in this text, creating a symphony of languages. The novel has an opening that might suit a gloomy fairytale: “In slavery times in the sugar isles, once there was an old black man.” The novel’s language is full of delightfully unexpected verbs and metaphors. At not much more than 100 pages, it is a nightmarish novella that alternates between feeling like a nebulous allegory and a realistic escaped slave narrative. It can be a disorienting experience: like the slave, readers are trapped in a menacing forest and prone to hallucinations. The lyricism of the writing and the brief glimpse back from the present day, in which an anthropologist discovers the slave’s remains and imagines the runaway back into life, give this book enduring power.

Lake Success by Gary Shteyngart

Barry Cohen, a conceited hedge fund manager under SEC investigation for insider trading, sets out on a several-month picaresque road trip in the second half of 2016. The ostensible aim is to find his college girlfriend, but he forms fleeting connections with lots of ordinary folks along the way. Barry may be a figure of fun, but it’s unpleasant to spend so much time with his chauvinism (“he never remembered women’s names” but gets plenty of them to sleep with him), which isn’t fully tempered by alternating chapters from his wife’s perspective. Pitched somewhere between the low point of “Make America Great Again” and the loftiness of the Great American novel, Lake Success may not achieve the profundity it’s aiming for, but it’s still a biting portrait of an all-too-recognizable America where money is God and villains gets off easy.

Barry Cohen, a conceited hedge fund manager under SEC investigation for insider trading, sets out on a several-month picaresque road trip in the second half of 2016. The ostensible aim is to find his college girlfriend, but he forms fleeting connections with lots of ordinary folks along the way. Barry may be a figure of fun, but it’s unpleasant to spend so much time with his chauvinism (“he never remembered women’s names” but gets plenty of them to sleep with him), which isn’t fully tempered by alternating chapters from his wife’s perspective. Pitched somewhere between the low point of “Make America Great Again” and the loftiness of the Great American novel, Lake Success may not achieve the profundity it’s aiming for, but it’s still a biting portrait of an all-too-recognizable America where money is God and villains gets off easy.

Shiny New Books reviews

(Upcoming: Nine Pints by Rose George and Under the Rock by Benjamin Myers.) Latest:

The Immeasurable World: Journeys in Desert Places by William Atkins

Atkins has produced an appealing blend of vivid travel anecdotes, historical background and philosophical musings. He is always conscious that he is treading in the footsteps of earlier adventurers. He has no illusions about being a pioneer here; rather, he eagerly picks up the thematic threads others have spun out of desert experience and runs with them – things like solitude, asceticism, punishment for wrongdoing and environmental degradation. The book is composed of seven long chapters, each set in a different desert. In my favorite segment, the author rents a cabin in the Sonoran Desert of Arizona for $100 a week. My interest waxed and waned from chapter to chapter, but readers of travelogues should find plenty to enjoy. Few of us would have the physical or emotional fortitude to repeat Atkins’s journeys, but we get the joy of being armchair travelers instead.

Atkins has produced an appealing blend of vivid travel anecdotes, historical background and philosophical musings. He is always conscious that he is treading in the footsteps of earlier adventurers. He has no illusions about being a pioneer here; rather, he eagerly picks up the thematic threads others have spun out of desert experience and runs with them – things like solitude, asceticism, punishment for wrongdoing and environmental degradation. The book is composed of seven long chapters, each set in a different desert. In my favorite segment, the author rents a cabin in the Sonoran Desert of Arizona for $100 a week. My interest waxed and waned from chapter to chapter, but readers of travelogues should find plenty to enjoy. Few of us would have the physical or emotional fortitude to repeat Atkins’s journeys, but we get the joy of being armchair travelers instead.

Mrs Gaskell & Me: Two Women, Two Love Stories, Two Centuries Apart by Nell Stevens

I was ambivalent about the author’s first book (Bleaker House), but for a student of the Victorian period this was unmissable, and the meta aspect was fun and not off-putting this time. Stevens has a light touch, and flits between Gaskell’s story and her own in alternating chapters. One strand covers the last decade of Gaskell’s life, but what makes it so lively and unusual is that Stevens almost always speaks of Gaskell as “you.” The intimacy of that address ensures her life story is anything but dry. The other chapters are set between 2013 and 2017 and narrated in the present tense, which makes Stevens’s dilemmas feel pressing. For much of the first two years her PhD takes a backseat to her love life. She’s obsessed with Max, a friend and unrequited crush from her Boston University days who is now living in Paris. This is a whimsical, sentimental, wry book that will ring true for anyone who’s ever been fixated on an idea or put too much stock in a relationship that failed to thrive.

I was ambivalent about the author’s first book (Bleaker House), but for a student of the Victorian period this was unmissable, and the meta aspect was fun and not off-putting this time. Stevens has a light touch, and flits between Gaskell’s story and her own in alternating chapters. One strand covers the last decade of Gaskell’s life, but what makes it so lively and unusual is that Stevens almost always speaks of Gaskell as “you.” The intimacy of that address ensures her life story is anything but dry. The other chapters are set between 2013 and 2017 and narrated in the present tense, which makes Stevens’s dilemmas feel pressing. For much of the first two years her PhD takes a backseat to her love life. She’s obsessed with Max, a friend and unrequited crush from her Boston University days who is now living in Paris. This is a whimsical, sentimental, wry book that will ring true for anyone who’s ever been fixated on an idea or put too much stock in a relationship that failed to thrive.

Times Literary Supplement reviews

I’ve recently submitted my sixth and seventh for publication. All of them have been behind a paywall so far, alas. (Upcoming: Face to Face: True stories of life, death and transformation from my career as a facial surgeon by Jim McCaul; On Sheep: Diary of a Swedish Shepherd by Axel Lindén.) Latest:

How To Build A Boat: A Father, his Daughter, and the Unsailed Sea by Jonathan Gornall

Gornall’s genial memoir is the story of a transformation and an adventure, as a fifty-something freelance journalist gets an unexpected second chance at fatherhood and decides to build his daughter, Phoebe, a boat. It was an uncharacteristic resolution for “a man who [had] never knowingly wielded a plane or a chisel,” yet in a more metaphorical way it made sense: the sea was in his family’s blood. Gornall nimbly conveys the precarious financial situation of the freelancer, as well as the challenges of adjusting to new parenthood late in life. This is a refreshingly down-to-earth account. The nitty-gritty details of the construction will appeal to some readers more than to others, but one can’t help admiring the combination of craftsmanship and ambition. (Full review in September 7th issue.)

Gornall’s genial memoir is the story of a transformation and an adventure, as a fifty-something freelance journalist gets an unexpected second chance at fatherhood and decides to build his daughter, Phoebe, a boat. It was an uncharacteristic resolution for “a man who [had] never knowingly wielded a plane or a chisel,” yet in a more metaphorical way it made sense: the sea was in his family’s blood. Gornall nimbly conveys the precarious financial situation of the freelancer, as well as the challenges of adjusting to new parenthood late in life. This is a refreshingly down-to-earth account. The nitty-gritty details of the construction will appeal to some readers more than to others, but one can’t help admiring the combination of craftsmanship and ambition. (Full review in September 7th issue.)

A mudslide blocked the route we should have taken back from Milan to Paris, so we rebooked onto trains via Switzerland. This plus the sub-Alpine setting for our next-to-last day made the perfect context for racing through Where the Hornbeam Grows: A Journey in Search of a Garden by Beth Lynch in just two days. Lynch moved from England to Switzerland when her husband took a job in Zurich. Suddenly she had to navigate daily life, including frosty locals and convoluted bureaucracy, in a second language. The sense of displacement was exacerbated by her lack of access to a garden. Gardening had always been a whole-family passion, and after her parents’ death their Sussex garden was lost to her. Two years later she and her husband moved to a cottage in western Switzerland and cultivated a garden idyll, but it wasn’t enough to neutralize their loneliness.

A mudslide blocked the route we should have taken back from Milan to Paris, so we rebooked onto trains via Switzerland. This plus the sub-Alpine setting for our next-to-last day made the perfect context for racing through Where the Hornbeam Grows: A Journey in Search of a Garden by Beth Lynch in just two days. Lynch moved from England to Switzerland when her husband took a job in Zurich. Suddenly she had to navigate daily life, including frosty locals and convoluted bureaucracy, in a second language. The sense of displacement was exacerbated by her lack of access to a garden. Gardening had always been a whole-family passion, and after her parents’ death their Sussex garden was lost to her. Two years later she and her husband moved to a cottage in western Switzerland and cultivated a garden idyll, but it wasn’t enough to neutralize their loneliness. Confessions of a Bookseller by Shaun Bythell: This picks up right where The Diary of a Bookseller left off and carries through the whole of 2015. Again it’s built on the daily routines of buying and selling books, including customers’ and colleagues’ quirks, and of being out and about in a small town. I wished I was in Wigtown instead of Milan! Because of where I was reading the book, I got particular enjoyment out of the characterization of Emanuela (soon known as “Granny” for her poor eyesight and myriad aches and gripes), who comes over from Italy to volunteer in the bookshop for the summer. Bythell’s break-up with “Anna” is a recurring theme in this volume, I suspect because his editor/publisher insisted on an injection of emotional drama.

Confessions of a Bookseller by Shaun Bythell: This picks up right where The Diary of a Bookseller left off and carries through the whole of 2015. Again it’s built on the daily routines of buying and selling books, including customers’ and colleagues’ quirks, and of being out and about in a small town. I wished I was in Wigtown instead of Milan! Because of where I was reading the book, I got particular enjoyment out of the characterization of Emanuela (soon known as “Granny” for her poor eyesight and myriad aches and gripes), who comes over from Italy to volunteer in the bookshop for the summer. Bythell’s break-up with “Anna” is a recurring theme in this volume, I suspect because his editor/publisher insisted on an injection of emotional drama.  City of Girls by Elizabeth Gilbert: There’s a fun, saucy feel to this novel set mostly in 1940s New York City. Twenty-year-old Vivian Morris comes to sew costumes for her Aunt Peg’s rundown theatre and falls in with a disreputable lot of actors and showgirls. When she does something bad enough to get her in the tabloids and jeopardize her future, she retreats in disgrace to her parents’ – but soon the war starts and she’s called back to help with Peg’s lunchtime propaganda shows at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The quirky coming-of-age narrative reminded me a lot of classic John Irving, while the specifics of the setting made me think of Wise Children, All the Beautiful Girls

City of Girls by Elizabeth Gilbert: There’s a fun, saucy feel to this novel set mostly in 1940s New York City. Twenty-year-old Vivian Morris comes to sew costumes for her Aunt Peg’s rundown theatre and falls in with a disreputable lot of actors and showgirls. When she does something bad enough to get her in the tabloids and jeopardize her future, she retreats in disgrace to her parents’ – but soon the war starts and she’s called back to help with Peg’s lunchtime propaganda shows at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The quirky coming-of-age narrative reminded me a lot of classic John Irving, while the specifics of the setting made me think of Wise Children, All the Beautiful Girls Judgment Day by Sandra M. Gilbert: English majors will know Gilbert best for her landmark work of criticism, The Madwoman in the Attic (co-written with Susan Gubar). I had no idea that she writes poetry. This latest collection has a lot of interesting reflections on religion, food and art, as well as elegies to those she’s lost. Raised Catholic, Gilbert married a Jew, and the traditions of Judaism still hold meaning for her after husband’s death even though she’s effectively an atheist. “Pompeii and After,” a series of poems describing food scenes in paintings, from da Vinci to Hopper, is particularly memorable.

Judgment Day by Sandra M. Gilbert: English majors will know Gilbert best for her landmark work of criticism, The Madwoman in the Attic (co-written with Susan Gubar). I had no idea that she writes poetry. This latest collection has a lot of interesting reflections on religion, food and art, as well as elegies to those she’s lost. Raised Catholic, Gilbert married a Jew, and the traditions of Judaism still hold meaning for her after husband’s death even though she’s effectively an atheist. “Pompeii and After,” a series of poems describing food scenes in paintings, from da Vinci to Hopper, is particularly memorable.  Vintage 1954 by Antoine Laurain: Dreadful! I would say: avoid this sappy time-travel novel at all costs. I thought the setup promised a gentle dose of fantasy, and liked the fact that the characters could meet their ancestors and Paris celebrities during their temporary stay in 1954. But the characters are one-dimensional stereotypes, and the plot is far-fetched and silly. I know many others have found this delightful, so consider me in the minority…

Vintage 1954 by Antoine Laurain: Dreadful! I would say: avoid this sappy time-travel novel at all costs. I thought the setup promised a gentle dose of fantasy, and liked the fact that the characters could meet their ancestors and Paris celebrities during their temporary stay in 1954. But the characters are one-dimensional stereotypes, and the plot is far-fetched and silly. I know many others have found this delightful, so consider me in the minority…

Blood Ties by Ben Crane: Artist Ben Crane has developed a passion for birds of prey, raising hawks and training as a falconer. “I saw that my feelings towards nature, and birds of prey in particular, ran in parallel with my feelings for my son,” he writes. Blood Ties accordingly cuts between the story of rehabilitating a pair of rescued sparrowhawks named Girl and Boy and a parallel story about raising his son as a part-time single father. Together these strands emphasize the common concerns that arise when caring for any creature. Crane’s descriptive language is memorably sharp. Whatever struggles his Asperger’s entails, it seems to heighten his observational skills. Pruning the travel segments would have produced a more focused memoir, but this is a powerful story all the same – of the ties that bind us, both to nature and our own families. (Full review in February 8th issue.)

Blood Ties by Ben Crane: Artist Ben Crane has developed a passion for birds of prey, raising hawks and training as a falconer. “I saw that my feelings towards nature, and birds of prey in particular, ran in parallel with my feelings for my son,” he writes. Blood Ties accordingly cuts between the story of rehabilitating a pair of rescued sparrowhawks named Girl and Boy and a parallel story about raising his son as a part-time single father. Together these strands emphasize the common concerns that arise when caring for any creature. Crane’s descriptive language is memorably sharp. Whatever struggles his Asperger’s entails, it seems to heighten his observational skills. Pruning the travel segments would have produced a more focused memoir, but this is a powerful story all the same – of the ties that bind us, both to nature and our own families. (Full review in February 8th issue.)  Notes for the Everlost: A Field Guide to Grief by Kate Inglis: Inglis, a Nova Scotian photographer and children’s author, has written this delicate, playful handbook – something between a bereavement memoir and a self-help guide – for people who feel they might disappear into grief for ever. In 2007, Inglis’s identical twin sons were born premature, at twenty-seven weeks. Ben lived but Liam died. Every milestone in Ben’s life would serve as a reminder of the brother who should have been growing up alongside him. The unfairness was particularly keen on the day she returned to hospital for two appointments: Ben’s check-up and a report on Liam’s autopsy. Unable to sustain the eye-popping freshness of the prose in the introduction, Inglis resorts to some clichés in what follows. But this kooky, candid book will be valuable to anyone facing bereavement or supporting a loved one through it. (Full review in March 15th issue.)

Notes for the Everlost: A Field Guide to Grief by Kate Inglis: Inglis, a Nova Scotian photographer and children’s author, has written this delicate, playful handbook – something between a bereavement memoir and a self-help guide – for people who feel they might disappear into grief for ever. In 2007, Inglis’s identical twin sons were born premature, at twenty-seven weeks. Ben lived but Liam died. Every milestone in Ben’s life would serve as a reminder of the brother who should have been growing up alongside him. The unfairness was particularly keen on the day she returned to hospital for two appointments: Ben’s check-up and a report on Liam’s autopsy. Unable to sustain the eye-popping freshness of the prose in the introduction, Inglis resorts to some clichés in what follows. But this kooky, candid book will be valuable to anyone facing bereavement or supporting a loved one through it. (Full review in March 15th issue.)

Face to Face: True stories of life, death and transformation from my career as a facial surgeon by Jim McCaul: Eighty percent of a facial surgeon’s work is the removal of face, mouth and neck tumors in surgeries lasting eight hours or more. McCaul also restores patients’ appearance as much as possible after disfiguring accidents. Here he pulls back the curtain on the everyday details of his work life: everything from his footwear (white Crocs that soon become stained with blood and other fluids) to his musical choices (pop for the early phases; classical for the more challenging microsurgery stage). Like neurosurgeon Henry Marsh, he describes the awe of the first incision – “an almost overwhelming sense of entering into a sanctuary.” There’s a vicarious thrill to being let into this insider zone, and the book’s prose is perfectly clear and conversational, with unexpectedly apt metaphors such as “Sometimes the blood vessels can be of such poor quality that it is like trying to sew together two damp cornflakes.” This is a book that inspires wonder at all that modern medicine can achieve.

Face to Face: True stories of life, death and transformation from my career as a facial surgeon by Jim McCaul: Eighty percent of a facial surgeon’s work is the removal of face, mouth and neck tumors in surgeries lasting eight hours or more. McCaul also restores patients’ appearance as much as possible after disfiguring accidents. Here he pulls back the curtain on the everyday details of his work life: everything from his footwear (white Crocs that soon become stained with blood and other fluids) to his musical choices (pop for the early phases; classical for the more challenging microsurgery stage). Like neurosurgeon Henry Marsh, he describes the awe of the first incision – “an almost overwhelming sense of entering into a sanctuary.” There’s a vicarious thrill to being let into this insider zone, and the book’s prose is perfectly clear and conversational, with unexpectedly apt metaphors such as “Sometimes the blood vessels can be of such poor quality that it is like trying to sew together two damp cornflakes.” This is a book that inspires wonder at all that modern medicine can achieve.  On Sheep: Diary of a Swedish Shepherd by Axel Lindén: Lindén left city life behind to take on his parents’ rural collective in southeast Sweden. This documents two years in his life as a shepherd aspiring to self-sufficiency and a small-scale model of food production. Published diaries can devolve into tedium, but the brevity and selectiveness of this one prevent its accounts of everyday tasks from becoming tiresome. Instead, the rural routines are comforting, even humbling, as the shepherd practices being present with these “quiet and unpretentious and stoical” creatures. The attention paid to slaughtering and sustainability issues – especially as the business starts scaling up and streamlining activities – lends the book a wider significance. It is thus more realistic and less twee than its stocking-stuffer dimensions and jolly title font seem to suggest.

On Sheep: Diary of a Swedish Shepherd by Axel Lindén: Lindén left city life behind to take on his parents’ rural collective in southeast Sweden. This documents two years in his life as a shepherd aspiring to self-sufficiency and a small-scale model of food production. Published diaries can devolve into tedium, but the brevity and selectiveness of this one prevent its accounts of everyday tasks from becoming tiresome. Instead, the rural routines are comforting, even humbling, as the shepherd practices being present with these “quiet and unpretentious and stoical” creatures. The attention paid to slaughtering and sustainability issues – especially as the business starts scaling up and streamlining activities – lends the book a wider significance. It is thus more realistic and less twee than its stocking-stuffer dimensions and jolly title font seem to suggest.