Tag Archives: short stories

Three on a Theme (Valentine’s Day): “Love” Books by Amy Bloom, George Mackay Brown & Hilary Mantel

Every year I say it: I’m really not a Valentine’s Day person and yet it’s become a tradition to put together a themed post featuring one or more books with “Love” or “Heart” in the title. This is the tenth year in a row, in fact – after 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024 and 2025. As you might expect, none of the three below contains a straightforward love story. The relationships portrayed tend to be unequal, creepy or doomed, but the solid character work and use of setting and voice was enough to keep me engaged with all of the books.

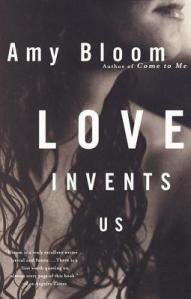

Love Invents Us by Amy Bloom (1997)

I’ve found Bloom’s short stories more successful than her novels. This is something of a halfway house: linked short stories (one of which was previously published in Come to Me; another that gives the title line to her 2000 collection A Blind Man Can See How Much I Love You) about Elizabeth Taube. When we first meet her on Long Island in the 1960s, she’s a rebellious and sexually precocious Jewish girl; by the time we’ve journeyed through several decades of vignettes, she’s a flighty and psychologically scarred single mother. Stories of her Lolita-esque attractiveness to grown salesmen and teachers, her shoplifting, her casual work for elderly African American Mrs. Hill, and her great love for Horace, nicknamed Huddie, a Black basketball player, are in the first person. The longer second part – about the aftermath of her physical affair with Huddie and her ongoing emotional entanglement with her English teacher, Max Stone – is in the third person yet feels more honest. Liz seems like bad news for everyone she meets. Bloom shows us some of the reasons for what she does, but I still couldn’t absolve her protagonist. I’d also reverse the title: We Invent Love. Liz is responsible for irrevocably altering two lives besides her own based on what she needs to feel secure. This is very much Lorrie Moore territory, but Moore leaves less of a bitter taste. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project)

I’ve found Bloom’s short stories more successful than her novels. This is something of a halfway house: linked short stories (one of which was previously published in Come to Me; another that gives the title line to her 2000 collection A Blind Man Can See How Much I Love You) about Elizabeth Taube. When we first meet her on Long Island in the 1960s, she’s a rebellious and sexually precocious Jewish girl; by the time we’ve journeyed through several decades of vignettes, she’s a flighty and psychologically scarred single mother. Stories of her Lolita-esque attractiveness to grown salesmen and teachers, her shoplifting, her casual work for elderly African American Mrs. Hill, and her great love for Horace, nicknamed Huddie, a Black basketball player, are in the first person. The longer second part – about the aftermath of her physical affair with Huddie and her ongoing emotional entanglement with her English teacher, Max Stone – is in the third person yet feels more honest. Liz seems like bad news for everyone she meets. Bloom shows us some of the reasons for what she does, but I still couldn’t absolve her protagonist. I’d also reverse the title: We Invent Love. Liz is responsible for irrevocably altering two lives besides her own based on what she needs to feel secure. This is very much Lorrie Moore territory, but Moore leaves less of a bitter taste. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project) ![]()

A Calendar of Love and Other Stories by George Mackay Brown (1967)

The title story opens a collection steeped in the landscape and history of Orkney. Each month we check in with three characters: Jean, who lives with her ailing father at the pub they run; and her two very different suitors, pious Peter and drunken Thorfinn. When she gives birth in December, you have to page back to see that she had encounters with both men in March. Some are playful in this vein or resemble folk tales: a boy playing hooky from school, a distant cousin so hapless as to father three bairns in the same household, and a rundown of the grades of whisky available on the islands. Others with medieval time markers are overwhelmingly bleak, especially “Witch,” about a woman’s trial and execution – and one of two stories set out like a play for voices. I quite liked the flash fiction “The Seller of Silk Shirts,” about a young Sikh man who arrives on the islands, and “The Story of Jorfel Hayforks,” in which a Norwegian man sails to find the man who impregnated his sister and keeps losing a crewman at each stop through improbable accidents. This is an atmospheric book I would have liked to read on location, but few of the individual stories stand out. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

The title story opens a collection steeped in the landscape and history of Orkney. Each month we check in with three characters: Jean, who lives with her ailing father at the pub they run; and her two very different suitors, pious Peter and drunken Thorfinn. When she gives birth in December, you have to page back to see that she had encounters with both men in March. Some are playful in this vein or resemble folk tales: a boy playing hooky from school, a distant cousin so hapless as to father three bairns in the same household, and a rundown of the grades of whisky available on the islands. Others with medieval time markers are overwhelmingly bleak, especially “Witch,” about a woman’s trial and execution – and one of two stories set out like a play for voices. I quite liked the flash fiction “The Seller of Silk Shirts,” about a young Sikh man who arrives on the islands, and “The Story of Jorfel Hayforks,” in which a Norwegian man sails to find the man who impregnated his sister and keeps losing a crewman at each stop through improbable accidents. This is an atmospheric book I would have liked to read on location, but few of the individual stories stand out. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

An Experiment in Love by Hilary Mantel (1995)

Mantel is best remembered for the Wolf Hall trilogy, but her early work includes a number of concise, sharp novels about growing up in the north of England. Carmel McBain attends a Catholic school in Manchester in the 1960s before leaving to study law at the University of London in 1970. In lockstep with her are a couple of friends, including Karina, who is of indeterminate Eastern European extraction and whose tragic Holocaust family history, added to her enduring poverty, always made her an object of pity for Carmel’s mother. But Karina as depicted by Carmel is haughty, even manipulative, and over the years their relationship swings between care and competition. As university students they live on the same corridor and have diverging experiences of schoolwork, romance, and food. “Now, I would not want you to think that this is a story about anorexia,” Carmel says early on, and indeed, she presents her condition as more like forgetting to eat. But then you recall tiny moments from her past when teachers and her mother shamed her for eating, and it’s clear a seed was sown. Carmel and her friends also deal with the results of the new-ish free love era. This is dark but funny, too, with Carmel likening roast parsnips to “ogres’ penises.” Further proof, along with Every Day Is Mother’s Day, that it’s well worth exploring authors’ back catalogue. (Public library)

Mantel is best remembered for the Wolf Hall trilogy, but her early work includes a number of concise, sharp novels about growing up in the north of England. Carmel McBain attends a Catholic school in Manchester in the 1960s before leaving to study law at the University of London in 1970. In lockstep with her are a couple of friends, including Karina, who is of indeterminate Eastern European extraction and whose tragic Holocaust family history, added to her enduring poverty, always made her an object of pity for Carmel’s mother. But Karina as depicted by Carmel is haughty, even manipulative, and over the years their relationship swings between care and competition. As university students they live on the same corridor and have diverging experiences of schoolwork, romance, and food. “Now, I would not want you to think that this is a story about anorexia,” Carmel says early on, and indeed, she presents her condition as more like forgetting to eat. But then you recall tiny moments from her past when teachers and her mother shamed her for eating, and it’s clear a seed was sown. Carmel and her friends also deal with the results of the new-ish free love era. This is dark but funny, too, with Carmel likening roast parsnips to “ogres’ penises.” Further proof, along with Every Day Is Mother’s Day, that it’s well worth exploring authors’ back catalogue. (Public library) ![]()

Plus a DNF:

Unexpected Lessons in Love by Bernardine Bishop (2013): I loved Bishop’s The Street, and this posthumous novel initially drew me in with its medical detail (two friends who both had stoma operations) and the exploration of different forms of love – romantic, parental, grandparental – before starting to feel obvious (two adoptions, one historical and one recent), maudlin and overlong. With some skimming, I made it to page 120. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com)

Unexpected Lessons in Love by Bernardine Bishop (2013): I loved Bishop’s The Street, and this posthumous novel initially drew me in with its medical detail (two friends who both had stoma operations) and the exploration of different forms of love – romantic, parental, grandparental – before starting to feel obvious (two adoptions, one historical and one recent), maudlin and overlong. With some skimming, I made it to page 120. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com)

Other relevant reading on the go:

I would have tried spinning this one into another thematic trio, but ran out of time…

A Rough Guide to the Heart by Pam Houston (1999): A mix of personal essays and short travel pieces. The material about her dysfunctional early family life, her chaotic dating, and her thrill-seeking adventures in the wilderness is reminiscent of the highly autobiographical Waltzing the Cat. Amusingly, this has a previous price label from Richard Booth’s Bookshop in Hay-on-Wye, where it was incorrectly classed as Romance Fiction – one could be excused the mistake based on the title and cover! (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project)

A Rough Guide to the Heart by Pam Houston (1999): A mix of personal essays and short travel pieces. The material about her dysfunctional early family life, her chaotic dating, and her thrill-seeking adventures in the wilderness is reminiscent of the highly autobiographical Waltzing the Cat. Amusingly, this has a previous price label from Richard Booth’s Bookshop in Hay-on-Wye, where it was incorrectly classed as Romance Fiction – one could be excused the mistake based on the title and cover! (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project)

And three books about marriage…

The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier – A pleasant year’s diary of rural living and adjusting to her husband’s new diagnosis of neurodivergence.

The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier – A pleasant year’s diary of rural living and adjusting to her husband’s new diagnosis of neurodivergence.- Strangers by Belle Burden – A high-profile memoir about her husband’s strange and marriage-ending behaviour (his affair was only part of it) during the 2020 lockdown.

- Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell – For Literary Wives Club in March. I’m in the early pages but it seems comparable to Richard Yates.

Most Anticipated Books of 2026

Later than intended, but here we are. I’ve narrowed it down to the 25 books I’m most looking forward to in January–September, though no doubt I’ll have heard of many more unmissable titles before that time is up. My list is dominated by fiction, which I tend to find out about earlier. Also on my radar are novels by Sharon Bala, Freya Bromley, Mary Costello, Louise Kennedy, Ben Lerner, Paula McLain, Liz Nugent and Tom Perrotta; short stories by Jess Gibson (Margaret Atwood’s daughter); and nonfiction from Margaret Drabble, Cal Flyn, Siri Hustvedt and Anne Lamott.

In release date order, with UK publication info given first if available. The blurbs are adapted from Goodreads. I’ve taken the liberty of using whichever cover I prefer.

Fiction

Departure(s) by Julian Barnes [20 Jan., Vintage (Penguin) / Knopf]: (Currently reading) I get more out of rereading Barnes’s classics than reading his latest stuff, but I’ll still attempt anything he publishes. He’s 80 and calls this his last book. So far, it’s heavily about memory. “Julian played matchmaker to Stephen and Jean, friends he met at university in the 1960s; as the third wheel, he was deeply invested in the success of their love”. Sounds way too similar to 1991’s Talking It Over, and the early pages have been tedious. (Review copy from publisher)

Departure(s) by Julian Barnes [20 Jan., Vintage (Penguin) / Knopf]: (Currently reading) I get more out of rereading Barnes’s classics than reading his latest stuff, but I’ll still attempt anything he publishes. He’s 80 and calls this his last book. So far, it’s heavily about memory. “Julian played matchmaker to Stephen and Jean, friends he met at university in the 1960s; as the third wheel, he was deeply invested in the success of their love”. Sounds way too similar to 1991’s Talking It Over, and the early pages have been tedious. (Review copy from publisher)

Half His Age by Jennette McCurdy [20 Jan., Fourth Estate / Ballantine]: McCurdy’s memoir, I’m Glad My Mom Died, was stranger than fiction. I was so impressed by her recreation of her childhood perspective on her dysfunctional Mormon/hoarding/child-actor/cancer survivor family that I have no doubt she’ll do justice to this reverse-Lolita scenario about a 17-year-old who’s in love with her schlubby creative writing teacher. (Library copy on order)

Half His Age by Jennette McCurdy [20 Jan., Fourth Estate / Ballantine]: McCurdy’s memoir, I’m Glad My Mom Died, was stranger than fiction. I was so impressed by her recreation of her childhood perspective on her dysfunctional Mormon/hoarding/child-actor/cancer survivor family that I have no doubt she’ll do justice to this reverse-Lolita scenario about a 17-year-old who’s in love with her schlubby creative writing teacher. (Library copy on order)

Our Better Natures by Sophie Ward [5 Feb., Corsair]: I loved Ward’s Booker-longlisted Love and Other Thought Experiments (though the follow-up, The Schoolhouse, was a letdown). “Amid the chaos and political upheaval of 1970s America, three very different women must accept the world as it is, or act to change it. Phyllis Patterson is a housewife in White Plains, Illinois. … Andrea Dworkin is an activist in Amsterdam. … Muriel Rukeyser is a poet in New York.” (Library copy on order)

Our Better Natures by Sophie Ward [5 Feb., Corsair]: I loved Ward’s Booker-longlisted Love and Other Thought Experiments (though the follow-up, The Schoolhouse, was a letdown). “Amid the chaos and political upheaval of 1970s America, three very different women must accept the world as it is, or act to change it. Phyllis Patterson is a housewife in White Plains, Illinois. … Andrea Dworkin is an activist in Amsterdam. … Muriel Rukeyser is a poet in New York.” (Library copy on order)

Brawler: Stories by Lauren Groff [Riverhead, Feb. 24]: (Currently reading) Controversial opinion: Short stories are where Groff really shines. Three-quarters in, this collection is just as impressive as Delicate Edible Birds or Florida. “Ranging from the 1950s to the present day and moving across age, class, and region (New England to Florida to California) these nine stories reflect and expand upon a shared the ceaseless battle between humans’ dark and light angels.” (For Shelf Awareness review) (Edelweiss download)

Brawler: Stories by Lauren Groff [Riverhead, Feb. 24]: (Currently reading) Controversial opinion: Short stories are where Groff really shines. Three-quarters in, this collection is just as impressive as Delicate Edible Birds or Florida. “Ranging from the 1950s to the present day and moving across age, class, and region (New England to Florida to California) these nine stories reflect and expand upon a shared the ceaseless battle between humans’ dark and light angels.” (For Shelf Awareness review) (Edelweiss download)

Kin by Tayari Jones [24 Feb., Oneworld / Knopf]: I’m a big fan of Leaving Atlanta and An American Marriage. This sounds like Brit Bennett meets Toni Morrison. “Vernice and Annie, two motherless daughters raised in Honeysuckle, Louisiana, have been best friends and neighbors since earliest childhood, but are fated to live starkly different lives. … A novel about mothers and daughters, about friendship and sisterhood, and the complexities of being a woman in the American South”. (Edelweiss download)

Kin by Tayari Jones [24 Feb., Oneworld / Knopf]: I’m a big fan of Leaving Atlanta and An American Marriage. This sounds like Brit Bennett meets Toni Morrison. “Vernice and Annie, two motherless daughters raised in Honeysuckle, Louisiana, have been best friends and neighbors since earliest childhood, but are fated to live starkly different lives. … A novel about mothers and daughters, about friendship and sisterhood, and the complexities of being a woman in the American South”. (Edelweiss download)

Almost Life by Kiran Millwood Hargrave [12 March, Picador / March 24, S&S/Summit Books]: There have often been queer undertones in Hargrave’s work, but this David Nicholls-esque plot sounds like her most overt. “Erica and Laure meet on the steps of the Sacré-Cœur in Paris, 1978. … The moment the two women meet the spark is undeniable. But their encounter turns into far more than a summer of love. It is the beginning of a relationship that will define their lives and every decision they have yet to make.” (Edelweiss download)

Almost Life by Kiran Millwood Hargrave [12 March, Picador / March 24, S&S/Summit Books]: There have often been queer undertones in Hargrave’s work, but this David Nicholls-esque plot sounds like her most overt. “Erica and Laure meet on the steps of the Sacré-Cœur in Paris, 1978. … The moment the two women meet the spark is undeniable. But their encounter turns into far more than a summer of love. It is the beginning of a relationship that will define their lives and every decision they have yet to make.” (Edelweiss download)

Patient, Female: Stories by Julie Schumacher [May 5, Milkweed Editions]: I found out about this via a webinar with Milkweed and a couple of other U.S. indie publishers. I loved Schumacher’s Dear Committee Members. “[T]his irreverent collection … balances sorrow against laughter. … Each protagonist—ranging from girlhood to senescence—receives her own indelible voice as she navigates social blunders, generational misunderstandings, and the absurdity of the human experience.” The publicist likened the tone to Meg Wolitzer.

Patient, Female: Stories by Julie Schumacher [May 5, Milkweed Editions]: I found out about this via a webinar with Milkweed and a couple of other U.S. indie publishers. I loved Schumacher’s Dear Committee Members. “[T]his irreverent collection … balances sorrow against laughter. … Each protagonist—ranging from girlhood to senescence—receives her own indelible voice as she navigates social blunders, generational misunderstandings, and the absurdity of the human experience.” The publicist likened the tone to Meg Wolitzer.

The Things We Never Say by Elizabeth Strout [7 May, Viking (Penguin) / May 5, Random House]: Hurrah for moving on from Lucy Barton at last! “Artie Dam is living a double life. He spends his days teaching history to eleventh graders … and, on weekends, takes his sailboat out on the beautiful Massachusetts Bay. … [O]ne day, Artie learns that life has been keeping a secret from him, one that threatens to upend his entire world. … [This] takes one man’s fears and loneliness and makes them universal.”

The Things We Never Say by Elizabeth Strout [7 May, Viking (Penguin) / May 5, Random House]: Hurrah for moving on from Lucy Barton at last! “Artie Dam is living a double life. He spends his days teaching history to eleventh graders … and, on weekends, takes his sailboat out on the beautiful Massachusetts Bay. … [O]ne day, Artie learns that life has been keeping a secret from him, one that threatens to upend his entire world. … [This] takes one man’s fears and loneliness and makes them universal.”

Hunger and Thirst by Claire Fuller [7 May, Penguin / June 2, Tin House]: I’ve read everything of Fuller’s and hope this will reverse the worsening trend of her novels, though true crime is overdone. “1987: After a childhood trauma and years in and out of the care system, sixteen-year-old Ursula … is invited to join a squat at The Underwood. … Thirty-six years later, Ursula is a renowned, reclusive sculptor living under a pseudonym in London when her identity is exposed by true-crime documentary-maker.” (Edelweiss download)

Hunger and Thirst by Claire Fuller [7 May, Penguin / June 2, Tin House]: I’ve read everything of Fuller’s and hope this will reverse the worsening trend of her novels, though true crime is overdone. “1987: After a childhood trauma and years in and out of the care system, sixteen-year-old Ursula … is invited to join a squat at The Underwood. … Thirty-six years later, Ursula is a renowned, reclusive sculptor living under a pseudonym in London when her identity is exposed by true-crime documentary-maker.” (Edelweiss download)

Little Vanities by Sarah Gilmartin [21 May, ONE (Pushkin)]: Gilmartin’s Service was great. “Dylan, Stevie and Ben have been inseparable since their days at Trinity, when everything seemed possible. … Two decades on, … Dylan, once a rugby star, is stranded on the sofa, cared for by his wife Rachel. Across town, Stevie and Ben’s relationship has settled into weary routine. Then, after countless auditions, Ben lands a role in Pinter’s Betrayal. As rehearsals unfold, the play’s shifting allegiances seep into reality, reviving old jealousies and awakening sudden longings.”

Little Vanities by Sarah Gilmartin [21 May, ONE (Pushkin)]: Gilmartin’s Service was great. “Dylan, Stevie and Ben have been inseparable since their days at Trinity, when everything seemed possible. … Two decades on, … Dylan, once a rugby star, is stranded on the sofa, cared for by his wife Rachel. Across town, Stevie and Ben’s relationship has settled into weary routine. Then, after countless auditions, Ben lands a role in Pinter’s Betrayal. As rehearsals unfold, the play’s shifting allegiances seep into reality, reviving old jealousies and awakening sudden longings.”

Said the Dead by Doireann Ní Ghríofa [21 May, Faber / Sept. 22, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: A Ghost in the Throat was brilliant and this sounds right up my street. “In the city of Cork, a derelict Victorian mental hospital is being converted into modern apartments. One passerby has always flinched as she passes the place. Had her birth occurred in another decade, she too might have lived within those walls. Now, … she finds herself drawn into an irresistible river of forgotten voices”.

Said the Dead by Doireann Ní Ghríofa [21 May, Faber / Sept. 22, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: A Ghost in the Throat was brilliant and this sounds right up my street. “In the city of Cork, a derelict Victorian mental hospital is being converted into modern apartments. One passerby has always flinched as she passes the place. Had her birth occurred in another decade, she too might have lived within those walls. Now, … she finds herself drawn into an irresistible river of forgotten voices”.

John of John by Douglas Stuart [21 May, Picador / May 5, Grove Press]: I DNFed Shuggie Bain and haven’t tried Stuart since, but the Outer Hebrides setting piqued my attention. “[W]ith little to show for his art school education, John-Calum Macleod takes the ferry back home to the island of Harris [and] begrudgingly resumes his old life, stuck between the two poles of his childhood: his father John, a sheep farmer, tweed weaver, and pillar of their local Presbyterian church, and his maternal grandmother Ella, a profanity-loving Glaswegian”. (For early Shelf Awareness review) (Edelweiss download)

John of John by Douglas Stuart [21 May, Picador / May 5, Grove Press]: I DNFed Shuggie Bain and haven’t tried Stuart since, but the Outer Hebrides setting piqued my attention. “[W]ith little to show for his art school education, John-Calum Macleod takes the ferry back home to the island of Harris [and] begrudgingly resumes his old life, stuck between the two poles of his childhood: his father John, a sheep farmer, tweed weaver, and pillar of their local Presbyterian church, and his maternal grandmother Ella, a profanity-loving Glaswegian”. (For early Shelf Awareness review) (Edelweiss download)

Land by Maggie O’Farrell [2 June, Tinder Press / Knopf]: I haven’t fully loved O’Farrell’s shift into historical fiction, but I’m still willing to give this a go. “On a windswept peninsula stretching out into the Atlantic, Tomás and his reluctant son, Liam [age 10], are working for the great Ordnance Survey project to map the whole of Ireland. The year is 1865, and in a country not long since ravaged and emptied by the Great Hunger, the task is not an easy one.” (Edelweiss download)

Land by Maggie O’Farrell [2 June, Tinder Press / Knopf]: I haven’t fully loved O’Farrell’s shift into historical fiction, but I’m still willing to give this a go. “On a windswept peninsula stretching out into the Atlantic, Tomás and his reluctant son, Liam [age 10], are working for the great Ordnance Survey project to map the whole of Ireland. The year is 1865, and in a country not long since ravaged and emptied by the Great Hunger, the task is not an easy one.” (Edelweiss download)

Whistler by Ann Patchett [2 June, Bloomsbury / Harper]: Patchett is hella reliable. “When Daphne Fuller and her husband Jonathan visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art, they notice an older, white-haired gentleman following them. The man turns out to be Eddie Triplett, her former stepfather, who had been married to her mother for a little more than year when Daphne was nine. … Meeting again, time falls away; … [in a story of] adults looking back over the choices they made, and the choices that were made for them.” (Edelweiss download)

Whistler by Ann Patchett [2 June, Bloomsbury / Harper]: Patchett is hella reliable. “When Daphne Fuller and her husband Jonathan visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art, they notice an older, white-haired gentleman following them. The man turns out to be Eddie Triplett, her former stepfather, who had been married to her mother for a little more than year when Daphne was nine. … Meeting again, time falls away; … [in a story of] adults looking back over the choices they made, and the choices that were made for them.” (Edelweiss download)

Returns and Exchanges by Kayla Rae Whitaker [2 June, Scribe / May 19, Random House]: Whitaker’s The Animators is one of my favourite novels that hardly anyone else has ever heard of. “A sweeping novel of one [discount department store-owning] Kentucky family’s rise and fall throughout the 1980s—a tragicomic tour de force about love and marriage, parents and [their four] children, and the perils of mixing family with business”. (Edelweiss download)

Returns and Exchanges by Kayla Rae Whitaker [2 June, Scribe / May 19, Random House]: Whitaker’s The Animators is one of my favourite novels that hardly anyone else has ever heard of. “A sweeping novel of one [discount department store-owning] Kentucky family’s rise and fall throughout the 1980s—a tragicomic tour de force about love and marriage, parents and [their four] children, and the perils of mixing family with business”. (Edelweiss download)

The Great Wherever by Shannon Sanders [9 July, Viking (Penguin) / July 7, Henry Holt]: Sanders’s linked story collection Company left me keen to follow her career. Aubrey Lamb, 32, is “grieving the recent loss of her father and the end of a relationship.” She leaves Washington, DC for her Black family’s ancestral Tennessee farm. “But the land proves to be a burdensome inheritance … [and] the ghosts of her ancestors interject with their own exasperated, gossipy commentary on the flaws and foibles of relatives living and dead”. (Edelweiss download)

The Great Wherever by Shannon Sanders [9 July, Viking (Penguin) / July 7, Henry Holt]: Sanders’s linked story collection Company left me keen to follow her career. Aubrey Lamb, 32, is “grieving the recent loss of her father and the end of a relationship.” She leaves Washington, DC for her Black family’s ancestral Tennessee farm. “But the land proves to be a burdensome inheritance … [and] the ghosts of her ancestors interject with their own exasperated, gossipy commentary on the flaws and foibles of relatives living and dead”. (Edelweiss download)

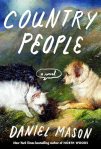

Country People by Daniel Mason [14 July, John Murray / July 7, Random House]: It doesn’t seem long enough since North Woods for there to be another Mason novel, but never mind. “Miles Krzelewski is … twelve years late with his PhD on Russian folktales … [W]hen his wife Kate accepts a visiting professorship at a prestigious college in the far away forests of Vermont, he decides that this will be his year to finally move forward with his life. … [A] luminous exploration of marriage and parenthood, the nature of belief and the power of stories, and the ways in which we find connection in an increasingly fragmented world.”

Country People by Daniel Mason [14 July, John Murray / July 7, Random House]: It doesn’t seem long enough since North Woods for there to be another Mason novel, but never mind. “Miles Krzelewski is … twelve years late with his PhD on Russian folktales … [W]hen his wife Kate accepts a visiting professorship at a prestigious college in the far away forests of Vermont, he decides that this will be his year to finally move forward with his life. … [A] luminous exploration of marriage and parenthood, the nature of belief and the power of stories, and the ways in which we find connection in an increasingly fragmented world.”

It Will Come Back to You: Collected Stories by Sigrid Nunez [14 July, Virago / Riverhead]: Nunez is one of my favourite authors but I never knew she’d written short stories. The blurb reveals very little about them! “Carefully selected from three decades of work … Moving from the momentous to the mundane, Nunez maintains her irrepressible humor, bite, and insight, her expert balance between intimacy and universality, gravity and levity, all while entertainingly probing the philosophical questions we have come to expect, such as: How can we withstand the passage of time? Is memory the greatest fiction?” (Edelweiss download)

It Will Come Back to You: Collected Stories by Sigrid Nunez [14 July, Virago / Riverhead]: Nunez is one of my favourite authors but I never knew she’d written short stories. The blurb reveals very little about them! “Carefully selected from three decades of work … Moving from the momentous to the mundane, Nunez maintains her irrepressible humor, bite, and insight, her expert balance between intimacy and universality, gravity and levity, all while entertainingly probing the philosophical questions we have come to expect, such as: How can we withstand the passage of time? Is memory the greatest fiction?” (Edelweiss download)

Exit Party by Emily St. John Mandel [17 Sept., Picador / Sept. 15, Knopf]: The synopsis sounds a bit meh, but in my eyes Mandel can do no wrong. “2031. America is at war with itself, but for the first time in weeks there is some good news: the Republic of California has been declared, the curfew in Los Angeles is lifted, and everyone in the city is going to a party. Ari, newly released from prison, arrives with her friend Gloria … Years later, living a different life in Paris, Ari remains haunted by that night.”

Exit Party by Emily St. John Mandel [17 Sept., Picador / Sept. 15, Knopf]: The synopsis sounds a bit meh, but in my eyes Mandel can do no wrong. “2031. America is at war with itself, but for the first time in weeks there is some good news: the Republic of California has been declared, the curfew in Los Angeles is lifted, and everyone in the city is going to a party. Ari, newly released from prison, arrives with her friend Gloria … Years later, living a different life in Paris, Ari remains haunted by that night.”

The Housekeeper by Rose Tremain [17 Sept., Vintage (Penguin); no cover image yet]: “Set in 1930s England and fictionalises the inspiration behind Daphne du Maurier’s famous novel, Rebecca.” Strangely, this started life as a short story (in The American Lover), then become a screenplay authored by Tremain (the film is in production and stars Uma Thurman and Anthony Hopkins), and is now being expanded into a novel. Tremain is 82 and a survivor of major cancer; I do wonder if this is the last book we can expect from her.

Nonfiction

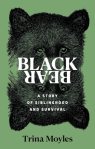

Black Bear: A Story of Siblinghood and Survival by Trina Moyles [Jan. 6, Pegasus Books]: Out now! “When Trina Moyles was five years old, her father … brought home an orphaned black bear cub for a night before sending it to the Calgary Zoo. … After years of working for human rights organizations, Trina returned to northern Alberta for a job as a fire tower lookout, while [her brother] Brendan worked in the oil sands … Over four summers, Trina begins to move beyond fear and observe the extraordinary essence of the maligned black bear”. (For BookBrowse review) (Review e-copy)

Black Bear: A Story of Siblinghood and Survival by Trina Moyles [Jan. 6, Pegasus Books]: Out now! “When Trina Moyles was five years old, her father … brought home an orphaned black bear cub for a night before sending it to the Calgary Zoo. … After years of working for human rights organizations, Trina returned to northern Alberta for a job as a fire tower lookout, while [her brother] Brendan worked in the oil sands … Over four summers, Trina begins to move beyond fear and observe the extraordinary essence of the maligned black bear”. (For BookBrowse review) (Review e-copy)

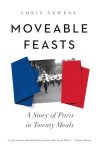

Moveable Feasts: A Story of Paris in Twenty Meals by Chris Newens [Feb. 3, Pegasus Books; came out in the UK in July 2025 but somehow I missed it!]: I’m a sucker for foodie books and Paris books. A “long-time resident of the historic slaughterhouse quartier Villette takes us on a delightful gastronomic journey around Paris … From Congolese catfish in the 18th to Middle Eastern falafels in the 4th, to the charcuterie served at the libertine nightclubs of Pigalle in the 9th, Newens lifts the lid on the city’s ever-changing, defining, and irresistible food culture.” (Edelweiss download)

Moveable Feasts: A Story of Paris in Twenty Meals by Chris Newens [Feb. 3, Pegasus Books; came out in the UK in July 2025 but somehow I missed it!]: I’m a sucker for foodie books and Paris books. A “long-time resident of the historic slaughterhouse quartier Villette takes us on a delightful gastronomic journey around Paris … From Congolese catfish in the 18th to Middle Eastern falafels in the 4th, to the charcuterie served at the libertine nightclubs of Pigalle in the 9th, Newens lifts the lid on the city’s ever-changing, defining, and irresistible food culture.” (Edelweiss download)

Frog: And Other Essays by Anne Fadiman [Feb. 10, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Fadiman publishes rarely, and it can be difficult to get hold of her books, but they are always worth it. “Ranging in subject matter from her deceased frog, to archaic printer technology, to the fraught relationship between Samuel Taylor Coleridge and his son Hartley, these essays unlock a whole world—one overflowing with mundanity and oddity—through sly observation and brilliant wit.”

Frog: And Other Essays by Anne Fadiman [Feb. 10, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Fadiman publishes rarely, and it can be difficult to get hold of her books, but they are always worth it. “Ranging in subject matter from her deceased frog, to archaic printer technology, to the fraught relationship between Samuel Taylor Coleridge and his son Hartley, these essays unlock a whole world—one overflowing with mundanity and oddity—through sly observation and brilliant wit.”

The Beginning Comes after the End: Notes on a World of Change by Rebecca Solnit [March 3, Haymarket Books]: A sequel to Hope in the Dark. Hope is a critically endangered species these days, but Solnit has her eyes open. “While the white nationalist and authoritarian backlash drives individualism and isolation, this new world embraces antiracism, feminism, a more expansive understanding of gender, environmental thinking, scientific breakthroughs, and Indigenous and non-Western ideas, pointing toward a more interconnected, relational world.” (Edelweiss download)

The Beginning Comes after the End: Notes on a World of Change by Rebecca Solnit [March 3, Haymarket Books]: A sequel to Hope in the Dark. Hope is a critically endangered species these days, but Solnit has her eyes open. “While the white nationalist and authoritarian backlash drives individualism and isolation, this new world embraces antiracism, feminism, a more expansive understanding of gender, environmental thinking, scientific breakthroughs, and Indigenous and non-Western ideas, pointing toward a more interconnected, relational world.” (Edelweiss download)

Jan Morris: A Life by Sara Wheeler [7 April, Faber / April 14, Harper]: I didn’t get on with the mammoth biography Paul Clements published in 2022 – it was dry and conventional; entirely unfitting for Morris – but hope for better things from a fellow female travel writer. “Wheeler uncovers the complexity of this twentieth-century icon … Drawing on unprecedented access to Morris’s papers as well as interviews with family, friends and colleagues, Wheeler assembles a captivating … story of longing, traveling and never reaching home.” (Edelweiss download)

Jan Morris: A Life by Sara Wheeler [7 April, Faber / April 14, Harper]: I didn’t get on with the mammoth biography Paul Clements published in 2022 – it was dry and conventional; entirely unfitting for Morris – but hope for better things from a fellow female travel writer. “Wheeler uncovers the complexity of this twentieth-century icon … Drawing on unprecedented access to Morris’s papers as well as interviews with family, friends and colleagues, Wheeler assembles a captivating … story of longing, traveling and never reaching home.” (Edelweiss download)

Others’ lists whence a few of my ideas came!

What catches your eye here? What other 2026 titles do I need to know about?

Best Books of 2025

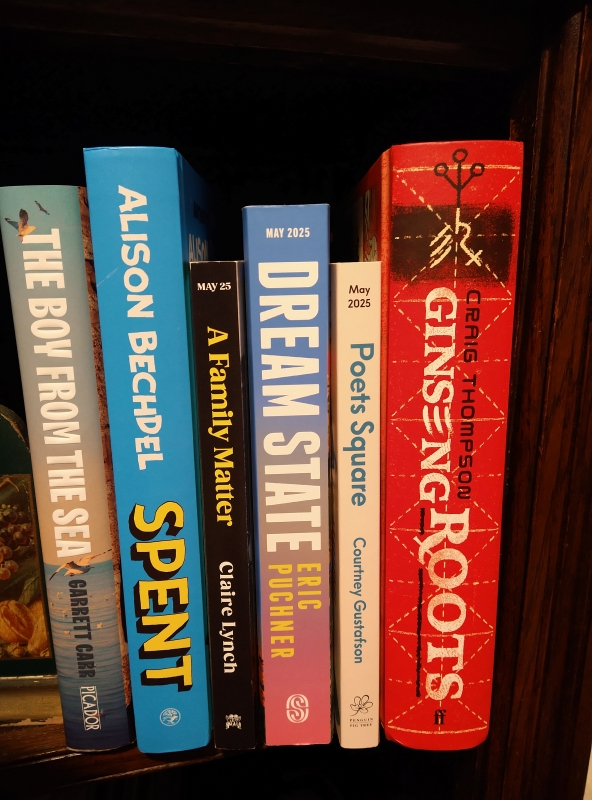

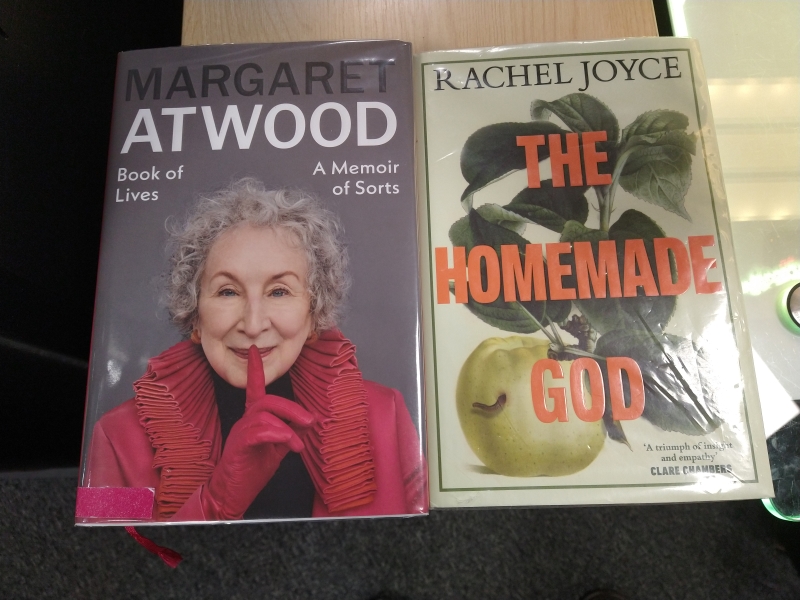

Without further ado, I present my 15 favourite releases from 2025. (With the 15 runners-up I chose yesterday, these represent about the top 9.5% of my current-year reading.) Pictured below are the ones I read in print; all the others were e-copies or library books I couldn’t get my hands on for a photo shoot. Links are to my full reviews where available.

Fiction

Spent: A Comic Novel by Alison Bechdel: Alison has writer’s block and is consumed with anxiety about the state of the world. “Who can draw when the world is burning?” Then she has an idea for a book – or a reality TV series – called $UM to wean people off of capitalism. That creative journey is mirrored here. Through Alison’s ageing hippie friends and their kids, Bechdel showcases alternative ways of living. Even the throwaway phrases are hilarious. It’s a gleeful and zeitgeist-y satire, yet draws to a touching close. So great, I read it twice.

Spent: A Comic Novel by Alison Bechdel: Alison has writer’s block and is consumed with anxiety about the state of the world. “Who can draw when the world is burning?” Then she has an idea for a book – or a reality TV series – called $UM to wean people off of capitalism. That creative journey is mirrored here. Through Alison’s ageing hippie friends and their kids, Bechdel showcases alternative ways of living. Even the throwaway phrases are hilarious. It’s a gleeful and zeitgeist-y satire, yet draws to a touching close. So great, I read it twice.

The Boy from the Sea by Garrett Carr: I was entranced by this story of an Irish family in the 1970s–80s: Ambrose, a fisherman left behind by technology; his wife Christine, walked all over by her belligerent father and sister; their son Declan, a budding foodie; and the title character, Brendan, a foundling they adopt and raise. Narrated by a chorus of village voices, this debut has the heart of Claire Keegan and the humour of Paul Murray. It reimagines biblical narratives, too: Cain and Abel, Jacob and Esau (brotherly rivalry!); Job and more.

The Boy from the Sea by Garrett Carr: I was entranced by this story of an Irish family in the 1970s–80s: Ambrose, a fisherman left behind by technology; his wife Christine, walked all over by her belligerent father and sister; their son Declan, a budding foodie; and the title character, Brendan, a foundling they adopt and raise. Narrated by a chorus of village voices, this debut has the heart of Claire Keegan and the humour of Paul Murray. It reimagines biblical narratives, too: Cain and Abel, Jacob and Esau (brotherly rivalry!); Job and more.

The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce: The story of four siblings initially drawn together (in Italy) and then dramatically blown apart by their father’s remarriage and death. Despite weighty themes including alcoholism and depression, there is an overall lightness of tone and style that made this a pleasure to read. Joyce has really upped her game: it’s more expansive, elegant and empathetic than her previous seven books. You can tell she got her start in theatre, too: she’s so good at scenes, dialogue, and moving groups of people around.

The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce: The story of four siblings initially drawn together (in Italy) and then dramatically blown apart by their father’s remarriage and death. Despite weighty themes including alcoholism and depression, there is an overall lightness of tone and style that made this a pleasure to read. Joyce has really upped her game: it’s more expansive, elegant and empathetic than her previous seven books. You can tell she got her start in theatre, too: she’s so good at scenes, dialogue, and moving groups of people around.

A Family Matter by Claire Lynch: In her research into UK divorce cases in the 1980s, Lynch learned that 90% of lesbian mothers lost custody of their children. Her earnest, delicate debut novel, which bounces between 2022 and 1982, imagines such a situation through close portraits of three family members. Maggie knew only that her mother, Dawn, abandoned her when she was little. Lynch’s compassion is equal for all three characters. This confident, tender story of changing mores and steadfast love is the new Carol for our times.

A Family Matter by Claire Lynch: In her research into UK divorce cases in the 1980s, Lynch learned that 90% of lesbian mothers lost custody of their children. Her earnest, delicate debut novel, which bounces between 2022 and 1982, imagines such a situation through close portraits of three family members. Maggie knew only that her mother, Dawn, abandoned her when she was little. Lynch’s compassion is equal for all three characters. This confident, tender story of changing mores and steadfast love is the new Carol for our times.

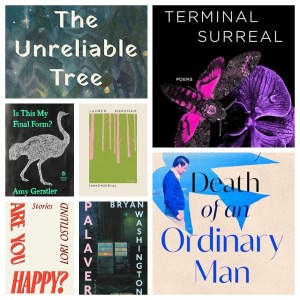

Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund: Nine short fictions form a stunning investigation into how violence and family dysfunction reverberate. “The Peeping Toms” and “The Stalker” are a knockout pair featuring Albuquerque lesbian couples under threat by male acquaintances. Characters are haunted by loss and grapple with moral dilemmas. Each story has the complexity and emotional depth of a novel. Freedom versus safety for queer people is a resonant theme in an engrossing collection ideal for Alice Munro and Edward St. Aubyn fans.

Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund: Nine short fictions form a stunning investigation into how violence and family dysfunction reverberate. “The Peeping Toms” and “The Stalker” are a knockout pair featuring Albuquerque lesbian couples under threat by male acquaintances. Characters are haunted by loss and grapple with moral dilemmas. Each story has the complexity and emotional depth of a novel. Freedom versus safety for queer people is a resonant theme in an engrossing collection ideal for Alice Munro and Edward St. Aubyn fans.

Dream State by Eric Puchner: It starts as a glistening romantic comedy about t Charlie and Cece’s chaotic wedding at a Montana lake house in summer 2004. First half the wedding party falls ill with norovirus, then the best man, Garrett, falls in love with the bride. The rest examines the fallout of this uneasy love triangle as it stretches towards 2050 and imagines a Western USA smothered in smoke from near-constant forest fires. Still, there are funny set-pieces and warm family interactions. Jonathan Franzen meets Maggie Shipstead.

Dream State by Eric Puchner: It starts as a glistening romantic comedy about t Charlie and Cece’s chaotic wedding at a Montana lake house in summer 2004. First half the wedding party falls ill with norovirus, then the best man, Garrett, falls in love with the bride. The rest examines the fallout of this uneasy love triangle as it stretches towards 2050 and imagines a Western USA smothered in smoke from near-constant forest fires. Still, there are funny set-pieces and warm family interactions. Jonathan Franzen meets Maggie Shipstead.

Palaver by Bryan Washington: Washington’s emotionally complex third novel explores the strained bond between a mother and her queer son – and their support systems of friends and lovers – when she visits him in Tokyo. The low-key plot builds through memories and interactions: the son’s with his students or hook-ups; the mother’s with restaurateurs as she gains confidence exploring Japan. Through words and black-and-white photographs, the author brings settings to life vibrantly. This is his best and most moving work yet.

Palaver by Bryan Washington: Washington’s emotionally complex third novel explores the strained bond between a mother and her queer son – and their support systems of friends and lovers – when she visits him in Tokyo. The low-key plot builds through memories and interactions: the son’s with his students or hook-ups; the mother’s with restaurateurs as she gains confidence exploring Japan. Through words and black-and-white photographs, the author brings settings to life vibrantly. This is his best and most moving work yet.

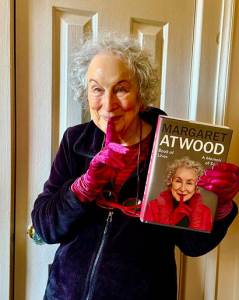

Nonfiction

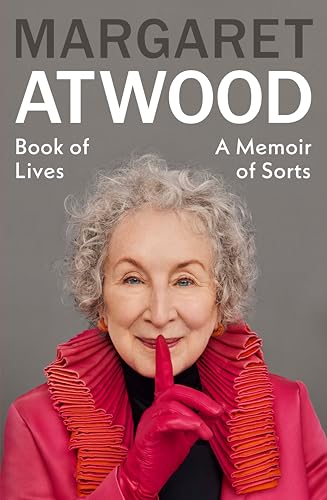

Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood: For diehard fans, this companion to her oeuvre is a trove of stories and photographs. The context on each book is illuminating and made me want to reread lots of her work. I was reminded how often she’s been ahead of her time. The title feels literal in that Atwood has been wilderness kid, literary ingénue, family and career woman, philanthropist and elder stateswoman. She doesn’t try to pull all her incarnations into one, instead leaving the threads trailing into the beyond.

Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood: For diehard fans, this companion to her oeuvre is a trove of stories and photographs. The context on each book is illuminating and made me want to reread lots of her work. I was reminded how often she’s been ahead of her time. The title feels literal in that Atwood has been wilderness kid, literary ingénue, family and career woman, philanthropist and elder stateswoman. She doesn’t try to pull all her incarnations into one, instead leaving the threads trailing into the beyond.

Poets Square: A Memoir in 30 Cats by Courtney Gustafson: Working for a food bank, trapped in a cycle of dead-end jobs and rising rents: Gustafson saw first hand how broken systems and poverty wear people down. She’d recently started feeding and getting veterinary care for a feral cat colony in her Tucson, Arizona neighbourhood. With its radiant portraits of individual cats and its realistic perspective on personal and collective problems, this is a cathartic memoir and a probing study of building communities of care in times of hardship.

Poets Square: A Memoir in 30 Cats by Courtney Gustafson: Working for a food bank, trapped in a cycle of dead-end jobs and rising rents: Gustafson saw first hand how broken systems and poverty wear people down. She’d recently started feeding and getting veterinary care for a feral cat colony in her Tucson, Arizona neighbourhood. With its radiant portraits of individual cats and its realistic perspective on personal and collective problems, this is a cathartic memoir and a probing study of building communities of care in times of hardship.

Immemorial by Lauren Markham: An outstanding book-length essay that compares language, memorials, and rituals as strategies for coping with climate anxiety and grief. The dichotomies of the physical versus the abstract and the permanent versus the ephemeral are explored. Forthright, wistful, and determined, the book treats grief as a positive, as “fuel” or a “portal.” Hope is not theoretical in this setup, but solidified in action. This is an elegant meditation on memory and impermanence in an age of climate crisis.

Immemorial by Lauren Markham: An outstanding book-length essay that compares language, memorials, and rituals as strategies for coping with climate anxiety and grief. The dichotomies of the physical versus the abstract and the permanent versus the ephemeral are explored. Forthright, wistful, and determined, the book treats grief as a positive, as “fuel” or a “portal.” Hope is not theoretical in this setup, but solidified in action. This is an elegant meditation on memory and impermanence in an age of climate crisis.

Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry: Perry recognises what a sacred privilege it was to witness her father-in-law’s death nine days after his diagnosis with oesophageal cancer. David’s end was as peaceful as could be hoped: in his late seventies, at home and looked after by his son and daughter-in-law, with mental capacity and minimal pain or distress. The beauty of this direct but tender memoir is its patient, clear-eyed unfolding of every stage of dying, a natural and inexorable process that in other centuries would have been familiar to all.

Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry: Perry recognises what a sacred privilege it was to witness her father-in-law’s death nine days after his diagnosis with oesophageal cancer. David’s end was as peaceful as could be hoped: in his late seventies, at home and looked after by his son and daughter-in-law, with mental capacity and minimal pain or distress. The beauty of this direct but tender memoir is its patient, clear-eyed unfolding of every stage of dying, a natural and inexorable process that in other centuries would have been familiar to all.

Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson: A book about everything, by way of ginseng. It begins with Thompson’s childhood summers working on American ginseng farms with his siblings in Marathon, Wisconsin. As an adult, he travels first to Midwest ginseng farms and festivals and then through China and Korea to learn about the plant’s history, cultivation, lore, and medicinal uses. Roots are symbolic of a family story that unfolds in parallel. Both expansive and intimate, this is a surprising gem from one of the best long-form graphic storytellers.

Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson: A book about everything, by way of ginseng. It begins with Thompson’s childhood summers working on American ginseng farms with his siblings in Marathon, Wisconsin. As an adult, he travels first to Midwest ginseng farms and festivals and then through China and Korea to learn about the plant’s history, cultivation, lore, and medicinal uses. Roots are symbolic of a family story that unfolds in parallel. Both expansive and intimate, this is a surprising gem from one of the best long-form graphic storytellers.

Poetry

Is This My Final Form? by Amy Gerstler: This delightfully odd collection amazes with its range of voices and techniques. It leaps from surrealism to elegy as it ponders life’s randomness. The language of transformation is integrated throughout. Aging and the seasons are examples of everyday changes. Elsewhere, speakers fall in love with the bride of Frankenstein or turn to dinosaur urine for a wellness regimen. Monologues and sonnets recur. Alliteration plus internal and end rhymes create satisfying resonance.

Is This My Final Form? by Amy Gerstler: This delightfully odd collection amazes with its range of voices and techniques. It leaps from surrealism to elegy as it ponders life’s randomness. The language of transformation is integrated throughout. Aging and the seasons are examples of everyday changes. Elsewhere, speakers fall in love with the bride of Frankenstein or turn to dinosaur urine for a wellness regimen. Monologues and sonnets recur. Alliteration plus internal and end rhymes create satisfying resonance.

The Unreliable Tree by Margot Kahn: Kahn’s radiant first collection ponders how traumatic events interrupt everyday life. Poles of loss and abundance structure delicate poems infused with family history and food imagery. The title phrase describes literal harvests but is also a metaphor for the vicissitudes of long relationships. California’s wildfires, Covid-19, a mass shooting, and health crises – an emergency surgery and a friend’s cancer – serve as reminders of life’s unpredictability. Disaster is random and inescapable.

The Unreliable Tree by Margot Kahn: Kahn’s radiant first collection ponders how traumatic events interrupt everyday life. Poles of loss and abundance structure delicate poems infused with family history and food imagery. The title phrase describes literal harvests but is also a metaphor for the vicissitudes of long relationships. California’s wildfires, Covid-19, a mass shooting, and health crises – an emergency surgery and a friend’s cancer – serve as reminders of life’s unpredictability. Disaster is random and inescapable.

Terminal Surreal by Martha Silano: Silano’s posthumous collection (her eighth) focuses on nature and relationships as she commemorates the joys and ironies of her last years with ALS. The shock of a terminal diagnosis was eased by the quotidian pleasures of observing Pacific Northwest nature, especially birds. Fascination with science recurs, too. Most pieces are free form and alliteration and wordplay enliven the register. Her winsome philosophical work is a gift. “What doesn’t die? / The closest I’ve come to an answer / is poetry.”

Terminal Surreal by Martha Silano: Silano’s posthumous collection (her eighth) focuses on nature and relationships as she commemorates the joys and ironies of her last years with ALS. The shock of a terminal diagnosis was eased by the quotidian pleasures of observing Pacific Northwest nature, especially birds. Fascination with science recurs, too. Most pieces are free form and alliteration and wordplay enliven the register. Her winsome philosophical work is a gift. “What doesn’t die? / The closest I’ve come to an answer / is poetry.”

If I had to pick one from each genre? Well, like last year, I find that the books that have stuck with me most are the ones that play around with the telling of life stories. This time, all by women. So it’s Spent, Book of Lives and Is This My Final Form?

What 2025 releases should I catch up on?

#MARM2025, Part II: Bluebeard’s Egg and Book of Lives (In Progress)

My hold on Margaret Atwood’s memoir, Book of Lives, arrived in late November. It’ll be my first read for Doorstoppers in December. I’d also been casually rereading her 1983 short story collection Bluebeard’s Egg and managed the first two stories; I’ll return to the rest next year. A recent Guardian interview stated that Atwood had written in “every genre … except autobiography” and quoted her as saying “I’m an old-fashioned novelist. Everything in my novels came from looking at the world around. I don’t think I have much of an inner psyche.” Is this her being coy or facetious? Because, particularly among the short stories, there are many incidents taken from her life. Indeed, in the 140 pages of Book of Lives that I’ve read so far, there are frequent mentions of how people or events made their way into her fiction and poetry. Perhaps most obviously in Cat’s Eye, a novel about childhood bullying by girlfriends.

My hold on Margaret Atwood’s memoir, Book of Lives, arrived in late November. It’ll be my first read for Doorstoppers in December. I’d also been casually rereading her 1983 short story collection Bluebeard’s Egg and managed the first two stories; I’ll return to the rest next year. A recent Guardian interview stated that Atwood had written in “every genre … except autobiography” and quoted her as saying “I’m an old-fashioned novelist. Everything in my novels came from looking at the world around. I don’t think I have much of an inner psyche.” Is this her being coy or facetious? Because, particularly among the short stories, there are many incidents taken from her life. Indeed, in the 140 pages of Book of Lives that I’ve read so far, there are frequent mentions of how people or events made their way into her fiction and poetry. Perhaps most obviously in Cat’s Eye, a novel about childhood bullying by girlfriends.

Bluebeard’s Egg opens with two Alice Munro-esque stories, “Significant Moments in the Life of My Mother” and “Hurricane Hazel,” both of which track with facts revealed in the memoir. The former draws on her mother Margaret’s Nova Scotia upbringing as the daughter of a country doctor (to avoid confusion, Atwood was nicknamed “Peggy”). Out of a welter of random stories comes the universal paradox: that she is in some ways exactly like her mother, and in others couldn’t be more different. It closes: “I had become a visitant from outer space, a time-traveller come back from the future, bearing news of a great disaster.” The latter story features a young teenage girl in a half-hearted relationship with an older, cooler boyfriend, mostly because she thinks it’s what’s expected of her. Atwood addresses it explicitly:

Bluebeard’s Egg opens with two Alice Munro-esque stories, “Significant Moments in the Life of My Mother” and “Hurricane Hazel,” both of which track with facts revealed in the memoir. The former draws on her mother Margaret’s Nova Scotia upbringing as the daughter of a country doctor (to avoid confusion, Atwood was nicknamed “Peggy”). Out of a welter of random stories comes the universal paradox: that she is in some ways exactly like her mother, and in others couldn’t be more different. It closes: “I had become a visitant from outer space, a time-traveller come back from the future, bearing news of a great disaster.” The latter story features a young teenage girl in a half-hearted relationship with an older, cooler boyfriend, mostly because she thinks it’s what’s expected of her. Atwood addresses it explicitly:

Let’s call this boyfriend “Buddy,” which is how he appears in a story of mine called “Hurricane Hazel.” Buddy and I broke up on the night of this famous hurricane, which flooded the Don Valley and killed eighty-one people in Toronto. Buddy wanted to go out that night, but my father, snapping out of his inattention—this was, after all, a matter of the weather, something he always kept his eye on—said it was out of the question. Didn’t Buddy know what a hurricane was? Far too dangerous!

One can also trace The Penelopiad (see my first post for Margaret Atwood Reading Month 2025) back to Atwood’s high school experiences with the Greek classics.

One can also trace The Penelopiad (see my first post for Margaret Atwood Reading Month 2025) back to Atwood’s high school experiences with the Greek classics.

Who knows when an “influence” may begin? My own 2005 book, The Penelopiad, had its origins fifty years before, when I’d been horrified by the brutal treatment dished out to Penelope’s twelve maids by Odysseus and Telemachus. After being made to clean up the blood from the suitors who’d raped them and were subsequently slaughtered by Odysseus, they were hanged in a line. “Their feet twitched, but not for very long.” A line I have always remembered.

As to Book of Lives in general, I’m finding it delightful but also dense with detail and historical context. Atwood grew up between the wilderness and the city because of her entomologist father’s seasonal fieldwork. She was called “Little Carl” due to how much she resembled her handy father, who built the cabins and houses they lived in as well as most of their furniture. With her beloved older brother, Harold, she was free to explore and later, as a camp counsellor, was known as “Peggy Nature” for her zoological expertise. She could easily have become a scientist but fell in love with crafts and the humanities, sewing her own clothes and writing an opera for Home Economics class. By the end of high school, she’d decided she was going to be a poet.

A cute pic of her from her Substack

I’m impressed by the clarity of Atwood’s memories; all I remember of my school days wouldn’t fill one chapter, let alone four. It could be argued that some of this is superfluous – a whole chapter on several summers as a counsellor at a Reform Jewish camp? But it’s her prerogative to choose the content and no doubt, always the novelist, she’s seeding important facts that will come to fruition later. As ever, her turns of phrase are amusing and her asides witty. There is a wonderful trove of photographs and artefacts for illustration. Although she effortlessly recreates her experience at any age, her perspective is salted with hindsight. I can already tell, making my way steadily through, 25 pages at a time, to return this by the deadline, that I’m going to need to read it again in the future to take it all in. Ideally, I’ll get my own copy so I can use the index to return to any scenes I want to revisit.

Bluebeard’s Egg – Little Free Library

Book of Lives – Public library

R.I.P. Reads, Part II: Feito, King, Link, Paver & Taylor

Soon it’ll be all novellas, all the time around here. But first I have a few more October reads to review.

A belated Happy Halloween! As a kid in the U.S. suburbs, I loved Halloween. It was such fun planning costumes – pumpkin, cowgirl and picnic table are a few memorable ones that I remember thanks to photographs – and my hoard of candy would last me for months. But these days, I tend to be pretty grumpy about the holiday. It never used to be a thing in the UK, but it has been creeping in year on year. I don’t mind a creatively carved jack o’ lantern, tasteful decoration or clever homemade costume. What does get my goat is plastic tat, gratuitous gore and the dozens of sodden sweets and wrappers littering the streets after last night’s rain and wind.

Anyway, we enjoyed the stormy evening because we spent it at friends’ having delicious autumnal lasagne and parkin, playing instruments and board games and eavesdropping on the trick-or-treaters. I had to laugh when J said “Take a couple” and one little girl replied, “That’s okay, I don’t really like sweeties.” These friends were keeping some ancient traditions alive: carving a turnip, wearing one’s clothes inside out and walking between two fires to ward off fairies. They also put potatoes in the treats bowl, which definitely confused the kids. (One did take a spud!)

I really leaned into the Readers Imbibing Peril reading this year. I had a somewhat lacklustre first batch, but these five were great!

Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito (2025)

This was among my Most Anticipated titles of the year – for the bonkers blurb but also because of how much I’d enjoyed Feito’s debut, Mrs. March. Both novels go deep with mentally disturbed protagonists. The first channeled Patricia Highsmith with its stylish psychological suspense; here we have a full-on blend of slasher horror and sadistic humour, wrapped up in a Victorian pastiche. Winifred Notty (naughty girl indeed) is the new governess at Ensor House on the Yorkshire moors. She couldn’t care less about her charges, Andrew and Drusilla. No, she’s here to exact revenge on the master of the house, Mr. Pounds. But not before she’s dispatched many a random servant and baby. “Bodies pile up in the attic.” Her brutal fantasies are so realistic that at times it’s difficult to separate them from what she actually carries out. Miss Notty is also a highly sexual being whose fixations could certainly be interpreted in Freudian ways. Feito spins a traumatic backstory for her antiheroine but doesn’t make it any excuse for her gleeful reign of terror. It’s delicious fun, especially for a Victorianist, but don’t attempt if you’re squeamish. (Read via NetGalley)

This was among my Most Anticipated titles of the year – for the bonkers blurb but also because of how much I’d enjoyed Feito’s debut, Mrs. March. Both novels go deep with mentally disturbed protagonists. The first channeled Patricia Highsmith with its stylish psychological suspense; here we have a full-on blend of slasher horror and sadistic humour, wrapped up in a Victorian pastiche. Winifred Notty (naughty girl indeed) is the new governess at Ensor House on the Yorkshire moors. She couldn’t care less about her charges, Andrew and Drusilla. No, she’s here to exact revenge on the master of the house, Mr. Pounds. But not before she’s dispatched many a random servant and baby. “Bodies pile up in the attic.” Her brutal fantasies are so realistic that at times it’s difficult to separate them from what she actually carries out. Miss Notty is also a highly sexual being whose fixations could certainly be interpreted in Freudian ways. Feito spins a traumatic backstory for her antiheroine but doesn’t make it any excuse for her gleeful reign of terror. It’s delicious fun, especially for a Victorianist, but don’t attempt if you’re squeamish. (Read via NetGalley)

Misery by Stephen King (1987)

All these years I’d had two 1989–1990 films conflated: Misery and My Left Foot. I’ve not seen either but as an impressionable young’un I made a mental mash-up of the posters’ stills into a film featuring Daniel Day-Lewis as a paralyzed writer and Kathy Bates as a madwoman wielding an axe. (Turns out the left foot is relevant!)

All these years I’d had two 1989–1990 films conflated: Misery and My Left Foot. I’ve not seen either but as an impressionable young’un I made a mental mash-up of the posters’ stills into a film featuring Daniel Day-Lewis as a paralyzed writer and Kathy Bates as a madwoman wielding an axe. (Turns out the left foot is relevant!)

Paul Sheldon wakes in a fog of pain, his legs shattered from a one-car accident on a snowy Colorado backroad. He’s famous for his historical potboilers about Misery Chastain but, like Arthur Conan Doyle with Sherlock Holmes, has killed off his most beloved character. Except now he’s in the home of Annie Wilkes, his rescuer and biggest fan, and she demands he resurrect Misery. Annie is a former nurse who left the profession after numerous suspicious deaths on her watch. She keeps Paul dependent on her – and on Novril, a fictional opiate. In a case of ‘Scheherazade complex’, he’ll be her prisoner until he’s completed a sequel that’s to her satisfaction. Compared to Pet Sematary, the only other King novel I’ve read, this was slow to draw me in because of the repetitive scenes in a claustrophobic setting, and I wearied of the excerpts from Paul’s manuscript. But eventually I was riveted, desperate to know how Paul was going to get out of this predicament and what the final showdown could be. Extremes of pain and obsession make this an intense study of the psychology of a wretched pair. (Public library)

Pretty Monsters by Kelly Link (2008)

This is a reissue edition geared towards young adults. All but one of the 10 stories were originally published in literary magazines or anthologies. The stories are long, some approaching novella length, and took me quite a while to read. I got through the first three and will save the rest for next year. In “The Wrong Grave,” a teen decides to dig up his dead girlfriend’s casket to reclaim the poems he rashly buried with her last year – as did Dante Gabriel Rossetti, which Link makes a point of mentioning. A terrific blend of spookiness and comedy ensues.

This is a reissue edition geared towards young adults. All but one of the 10 stories were originally published in literary magazines or anthologies. The stories are long, some approaching novella length, and took me quite a while to read. I got through the first three and will save the rest for next year. In “The Wrong Grave,” a teen decides to dig up his dead girlfriend’s casket to reclaim the poems he rashly buried with her last year – as did Dante Gabriel Rossetti, which Link makes a point of mentioning. A terrific blend of spookiness and comedy ensues.

“The Wizards of Perfil” and the title story are 50-some and 60-some pages, respectively, which allows a lot of space for intriguing weirdness and side plots. In the former, Onion’s cousin Halsa is purchased to be a servant to a wizard. The cousins both have the gift of foresight but can’t get the wizards to take them seriously when they beg that something to be done to prevent human disasters. It’s a brilliant allegory of the danger of waiting for an external force – God, the government, whatever – to solve everything versus getting on with it yourself. In the title story, a group of teens are obsessed with a mysterious Doctor Who-esque television show called The Library, which colours all their interactions. The main character Jeremy’s father is an eccentric sci-fi novelist named Gordon Strangle Mars who has written his son into his latest plot in a disturbing way. Jeremy recently inherited a gas station and phone box in Las Vegas and occasionally calls the phone box to air his grievances and solicit supernatural aid. My only other experience of Link was a standalone story I was once sent for review, “The Summer People,” which I didn’t get on with, so I was surprised to encounter such top-notch fantasy/horror tales. (Little Free Library)

Rainforest by Michelle Paver (2025)

I’d read all three of Paver’s previous horror novels for adults (Thin Air, Dark Matter and Wakenhyrst) and found them easy, atmospheric reading but not nearly as scary as billed. This is her best yet. Set in 1973 on an expedition to Mexico, it has as its unreliable narrator Dr. Simon Corbett, an English entomologist. Adding to the findings of the archaeological dig he’s accompanying, he’ll be hunting for mantids (praying mantises, stick insects and the like) by fogging sacred trees with pesticides. He also experiments with taking a hallucinogenic plant extract used by the Indigenous shamans, hoping to be reunited with his lost love, Penelope.

I’d read all three of Paver’s previous horror novels for adults (Thin Air, Dark Matter and Wakenhyrst) and found them easy, atmospheric reading but not nearly as scary as billed. This is her best yet. Set in 1973 on an expedition to Mexico, it has as its unreliable narrator Dr. Simon Corbett, an English entomologist. Adding to the findings of the archaeological dig he’s accompanying, he’ll be hunting for mantids (praying mantises, stick insects and the like) by fogging sacred trees with pesticides. He also experiments with taking a hallucinogenic plant extract used by the Indigenous shamans, hoping to be reunited with his lost love, Penelope.

We know that Corbett’s employment is tenuous and that he’s seeing a therapist. Paver authentically reproduces the casual racism and sexism of the time and seeds little hints that this protagonist may not be telling the whole truth about his relationship with Penelope. The long sequence where he’s lost in the jungle is fantastic. Corbett seems fated to repeat ancient masochistic rites, as if in penance for what he’s done wrong. My husband is an entomologist, so I was interested to read about period collecting practices. The novelty of the setting is a bonus to this high-quality psychological thriller and ghost story. (Public library)

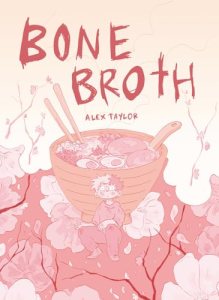

Bone Broth by Alex Taylor (2025)

Ash is a trans man who starts working at a hole-in-the-wall ramen restaurant underneath a London railway arch. All he wants is to “pay for hormones, pay rent, [and] make enough to take a cutie on a date.” Bug’s Bones is run by an irascible elderly proprietor but staffed by a young multicultural bunch: Sock, Blue, Honey and Creamy. They quickly show Ash the ropes and within a month he’s turning out perfect bowls. He’s creeped out by the restaurant’s trademark bone broth, though, with its reminders of creatures turning into food. At the end of a drunken staff party, they find Bug lying dead and have to figure out what to do about it.

Ash is a trans man who starts working at a hole-in-the-wall ramen restaurant underneath a London railway arch. All he wants is to “pay for hormones, pay rent, [and] make enough to take a cutie on a date.” Bug’s Bones is run by an irascible elderly proprietor but staffed by a young multicultural bunch: Sock, Blue, Honey and Creamy. They quickly show Ash the ropes and within a month he’s turning out perfect bowls. He’s creeped out by the restaurant’s trademark bone broth, though, with its reminders of creatures turning into food. At the end of a drunken staff party, they find Bug lying dead and have to figure out what to do about it.

This storyline is in purple, whereas the alternating sequences of flashbacks are in a fleshy pinkish-red. As the two finally meet and meld, we see Ash trying to imitate the masculinity he sees on display while he waits for the surface to match what’s inside. I didn’t love the drawing style – though the full-page tableaux are a lot better than the high-school-sketchbook small panes – so that was an issue for me throughout, but this was an interesting, ghoulish take on the transmasc experience. Taylor won a First Graphic Novel Award.

This storyline is in purple, whereas the alternating sequences of flashbacks are in a fleshy pinkish-red. As the two finally meet and meld, we see Ash trying to imitate the masculinity he sees on display while he waits for the surface to match what’s inside. I didn’t love the drawing style – though the full-page tableaux are a lot better than the high-school-sketchbook small panes – so that was an issue for me throughout, but this was an interesting, ghoulish take on the transmasc experience. Taylor won a First Graphic Novel Award.

With thanks to SelfMadeHero for the free copy for review.

And one DNF: Saltwash by Andrew Michael Hurley. (I was warned!) It had no menace or momentum at all…

Any stand-out creepy reading for you this year?

Short Story Catch-Up: Carver, Cunningham, Park, Polders, Racket, Schweblin, Williams (& Heti Stand-Alone)

I actually read 15 collections in total for Short Story September. I’m finally catching up on reviews, though I’m aware that I’ve missed out on Lisa’s link-up. (My other reviews: Heiny, Mackay, McEwan; the BBC National Short Story Award 2025 anthology; Donoghue, Grass, Isherwood, Mansfield as part of my Germany reading.) To keep it simple and get the basics across before I forget any more about these books, I’ll post some shorthand notes under headings.

Cathedral by Raymond Carver (1983)

Why I read it:

- I’d really enjoyed What We Talk about When We Talk about Love.

- This fits into my project to read books from my birth year.

Stats: 12 stories (6 x 1st-person, 6 x 3rd-person)

Stats: 12 stories (6 x 1st-person, 6 x 3rd-person)

Themes: alcoholism, adultery, fatherhood, crap jobs, crumbling families

Tone: melancholy, laconic

File under: grit-lit

For fans of: John Cheever, Ernest Hemingway, Denis Johnson

Caveat(s): It doesn’t match What We Talk about When We Talk about Love.

If you read just one story, make it: “A Small, Good Thing”

(University library) ![]()

A Wild Swan and Other Tales by Michael Cunningham (2015)

Why I read it:

- I have a vague plan to read through Cunningham’s whole oeuvre.

- This one is different to his others, and beautifully illustrated by Yuko Shimizu.

Stats: 11 stories (3 x 2nd-person, 8 x 3rd-person)

Stats: 11 stories (3 x 2nd-person, 8 x 3rd-person)

Themes: coming of age, longing, loss, bargaining

Tone: witty, knowing

File under: fairy tale updates

For fans of: Margaret Atwood, Neil Gaiman

Caveat(s): For the most part, he doesn’t do anything interesting with the story lines.

If you read just one story, make it: “Little Man” (the Rumpelstiltskin remake)

(Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

An Oral History of Atlantis by Ed Park (2025)

Why I read it:

- I’d heard buzz, probably because Park was a Pulitzer Prize finalist for his novel.

Stats: 16 stories (12 x 1st-person, 1 x 1st-person plural, 1 x 2nd-person, 2 x 3rd-person)

Stats: 16 stories (12 x 1st-person, 1 x 1st-person plural, 1 x 2nd-person, 2 x 3rd-person)

Themes: the Asian American and university experience, writing, translation, aphorisms

Tone: jokey, nostalgic

File under: dystopian fiction, metafiction

For fans of: George Saunders

Caveat(s): There’s more intellectual experimentation than emotional engagement.

If you read just one story, make it: “An Accurate Account”

(Read via NetGalley) ![]()

Woman of the Hour by Clare Polders (2025)

Why I read it:

- I always like to sneak at least one flash fiction collection in for this challenge.

Stats: 50 stories, a mixture of 1st- and 3rd-person

Stats: 50 stories, a mixture of 1st- and 3rd-person

Themes: childhood, sexuality, motherhood, choices vs. fate

Tone: sharp, matter-of-fact

File under: feminist, satire

For fans of: Claire Fuller, Terese Svoboda

Caveat(s): There’s too many stories to keep track of and not enough stand-outs.

If you read just one story, make it: “Woman of the Hour”

(BookSirens) ![]()

Racket: New Writing Made in Newfoundland, ed. Lisa Moore (2015)

Why I read it:

- Naomi’s blog always whets my appetite for Atlantic Canadian fiction, but I’m rarely able to find it over here.

Stats: 11 stories, mostly by Memorial University creative writing graduates (7 x 1st-person, 1 x 2nd-person, 3 x 3rd-person)

Stats: 11 stories, mostly by Memorial University creative writing graduates (7 x 1st-person, 1 x 2nd-person, 3 x 3rd-person)

Themes: mental health, bereavement, tragic accidents

Tone: jaunty, reflective

File under: voice-y early-2000s lit-fic

For fans of: Sharon Bala (her story is among the best here), Jonathan Safran Foer; hockey

Caveat(s): I wouldn’t say I’m now a fan of any of the writers I hadn’t heard of before.