The Party by Tessa Hadley (Blog Tour and #NovNov24)

You can count on Tessa Hadley for atmospheric, sophisticated stories of familial and romantic relationships in mid- to late-twentieth-century England. The Party is a novella of sisters Moira and Evelyn, university students on the cusp of womanhood. In 1950s Bristol, the Second World War casts a long shadow and new conflicts loom – Moira’s former beau was sent to Malaya. Suave as they try to seem, with Evelyn peppering her speech with the phrases she’s learning in the first year of her French degree, the girls can’t hide their origins in the Northeast. When Evelyn joins Moira at an art students’ party in a pub, fashionable outfits make them look older and more confident than they really are. Evelyn admits to her classmate, Donald, “I’m always disappointed at parties. I long to be, you know, a succès fou, but I never am.” Then the sisters meet Paul and Sinden, who flatter them by taking an interest; they are attracted to the men’s worldly wise air but also find them oddly odious.

You can count on Tessa Hadley for atmospheric, sophisticated stories of familial and romantic relationships in mid- to late-twentieth-century England. The Party is a novella of sisters Moira and Evelyn, university students on the cusp of womanhood. In 1950s Bristol, the Second World War casts a long shadow and new conflicts loom – Moira’s former beau was sent to Malaya. Suave as they try to seem, with Evelyn peppering her speech with the phrases she’s learning in the first year of her French degree, the girls can’t hide their origins in the Northeast. When Evelyn joins Moira at an art students’ party in a pub, fashionable outfits make them look older and more confident than they really are. Evelyn admits to her classmate, Donald, “I’m always disappointed at parties. I long to be, you know, a succès fou, but I never am.” Then the sisters meet Paul and Sinden, who flatter them by taking an interest; they are attracted to the men’s worldly wise air but also find them oddly odious.

The novella’s three chapters each revolve around a party. First is the Bristol dockside pub party (published as a short story in the New Yorker); second is a cocktail party the girls’ parents are preparing for, giving us a window onto their troubled marriage; finally is a gathering Paul invites them to at the shabby inherited mansion he lives in with his cousin, invalid brother, and louche sister. “We camp in it like kids,” Paul says. “Just playing at being grown up, you know.” During their night spent at the mansion, the sisters become painfully aware of the class difference between them and Paul’s moneyed family. The divide between innocence and experience may be sharp, but the line between love and hatred is not always as clear as they expected. And from moments of decision all the rest of life flows.

In her novels and story collections, Hadley often writes about strained families, young women on the edge, and the way sex can force a change in direction. This was my eighth time reading her, and though The Party is as stylish as all her work, it didn’t particularly stand out for me, lacking the depth of her novels and the concentration of her stories. Still, it would be a good introduction to Hadley or, if you’re an established fan like me, you could read it in a sitting and be reminded of her sharp eye for manners and pretensions – and the emotions they mask.

[115 pages]

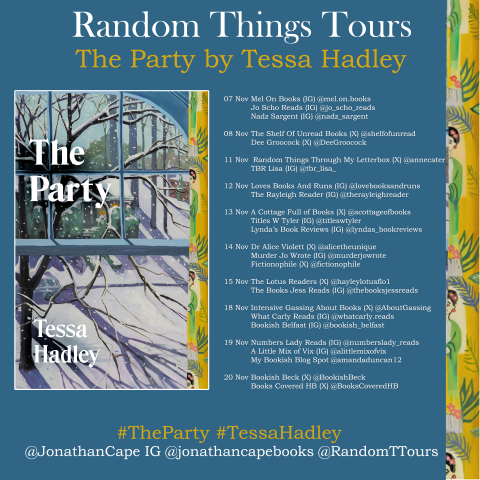

With thanks to Anne Cater of Random Things Tours and Jonathan Cape (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Buy The Party from Bookshop.org [affiliate link]

I was delighted to be part of the blog tour for The Party. See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will appear soon.

Reading the Meow, Part II: Books by Bernardine Bishop and Matt Haig

This is my second contribution to the Reading the Meow challenge, hosted by Mallika of Literary Potpourri, after yesterday’s review of Sleeping with Cats by Marge Piercy. One of the below novels is obviously cat-themed; the other less so, but the cover and blurb convinced me to take a chance on a new-to-me author and I discovered a hidden gem.

The Street by Bernardine Bishop (2015)

Prices are so cheap at my local charity warehouse (3/£1 paperbacks) that I recently did something I almost never do: bought a book I’d never heard of, by an author I’d never heard of, and then (something I definitely never do!) read it almost right away instead of letting it gather dust on my shelves for years. Bishop’s biography is wild. As a new Cambridge graduate, she was the youngest witness in the Lady Chatterley trial in 1960, then published two novels in her early twenties. She married twice, had two sons and a psychotherapy career, and returned to writing fiction after 50 years – prompted by a cancer diagnosis. Unexpected Lessons in Love was shortlisted for the Costa Novel Award in 2013, while this and Hidden Knowledge were both published posthumously, after Bishop’s death in 2015.

So: there is a cat on the cover and the blurb mentions it, too: “a beloved cat achieves immortality.” (I should have realized that was a euphemism, but never mind.) The novel opens with news of the death at 90 of formidable Brenda Byfleet, who’d been a Greenham Common woman and taken part in peace protests right into old age. Neighbours quickly realize someone will need to care for her cat Benn (named for Tony Benn), and the duty falls to Anne and Eric, who have also taken in their grandson while his parents are in Canada.

What follows is a low-key ensemble story that moves with ease between several key residences of Palmerston Street, London, introducing us to a couple struggling with infertility, a war veteran with dementia, an underemployed actor who rescues his wife from her boss’s unwanted attentions, and so on. Most touching is the relationship between Anne and Georgia, a lesbian snail researcher who paints Anne’s portrait. Their friendship shades into quiet, middle-aged love.

What follows is a low-key ensemble story that moves with ease between several key residences of Palmerston Street, London, introducing us to a couple struggling with infertility, a war veteran with dementia, an underemployed actor who rescues his wife from her boss’s unwanted attentions, and so on. Most touching is the relationship between Anne and Georgia, a lesbian snail researcher who paints Anne’s portrait. Their friendship shades into quiet, middle-aged love.

There are secrets and threats and climactic moments here, but always the reassuring sense that neighbours are a kind of second family and so someone will be there for you to rely on no matter what you face. (I can think of a certain soap opera theme that expresses a similar sentiment…) Bishop’s style reminds me most of Tessa Hadley’s. She is equally skilled at drawing children and the elderly, and clearly feels love and compassion for her flawed characters: “Everything and everyone in the street was bathed in a blessed ordinariness.”

From Brenda onward, Georgia’s rhetorical question hangs over the short novel: “What is a life?” The implied partial answer is: what is remembered by those left behind. The opening paragraph is perfect –

“Sometimes it is impossible to turn even a short London street into a village. But sometimes it can be easily done. It all depends on one or two personalities.”

… and the last page has kittens. This was altogether a lovely read. Dangit, why didn’t I also buy the other Bishop novel that was on shelf at the charity warehouse?! I’ll have to hope it’s still around the next time I go there. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

To Be a Cat by Matt Haig (2012)

This was a reasonably cute middle-grade fantasy and careful-what-you-wish-for cautionary tale. On his twelfth birthday, Barney Willow thinks life couldn’t get worse. His parents are divorced, his dad has recently disappeared, he’s bullied by Gavin Needle, and evil head teacher Miss Whipmire seems to have a personal vendetta against him. His only friend is Rissa Fairweather, who lives on a barge. Little does he know that an idle wish to switch places with a cat he pets on the street will set a dangerous adventure in motion. Now he’s a cat and Maurice the cat has his body. Soon Barney realizes there’s a whole subset of cats who are former humans (alongside “swipers,” proper fighting street cats; and “firesides,” who prefer to stay indoors), including Miss Whipmire, who used to be a Siamese cat and has an escape plan that involves Barney. I felt the influence of Roald Dahl and Terry Pratchett, but Haig doesn’t have their writing chops. Apart from Rissa, the characterization is too clichéd. I’m sure I would have enjoyed this at age eight, though. (Little Free Library)

This was a reasonably cute middle-grade fantasy and careful-what-you-wish-for cautionary tale. On his twelfth birthday, Barney Willow thinks life couldn’t get worse. His parents are divorced, his dad has recently disappeared, he’s bullied by Gavin Needle, and evil head teacher Miss Whipmire seems to have a personal vendetta against him. His only friend is Rissa Fairweather, who lives on a barge. Little does he know that an idle wish to switch places with a cat he pets on the street will set a dangerous adventure in motion. Now he’s a cat and Maurice the cat has his body. Soon Barney realizes there’s a whole subset of cats who are former humans (alongside “swipers,” proper fighting street cats; and “firesides,” who prefer to stay indoors), including Miss Whipmire, who used to be a Siamese cat and has an escape plan that involves Barney. I felt the influence of Roald Dahl and Terry Pratchett, but Haig doesn’t have their writing chops. Apart from Rissa, the characterization is too clichéd. I’m sure I would have enjoyed this at age eight, though. (Little Free Library) ![]()

Women’s Prize 2022: Longlist Wishes vs. Predictions

Next Tuesday the 8th, the 2022 Women’s Prize longlist will be announced.

First I have a list of 16 novels I want to be longlisted, because I’ve read and loved them (or at least thought they were interesting), or am currently reading and enjoying them, or plan to read them soon, or am desperate to get hold of them.

Wishlist

Brown Girls by Daphne Palasi Andreades

Our Wives Under the Sea by Julia Armfield (my review)

Ghosted by Jenn Ashworth (my review)

These Days by Lucy Caldwell

Damnation Spring by Ash Davidson – currently reading

Olga Dies Dreaming by Xóchitl González – currently reading

Burntcoat by Sarah Hall (my review)

Early Morning Riser by Katherine Heiny (my review)

Pure Colour by Sheila Heti

My Monticello by Jocelyn Nicole Johnson (my review)

Devotion by Hannah Kent – currently reading

Build Your House Around My Body by Violet Kupersmith – currently reading

When the Stars Go Dark by Paula McLain (my review)

The Swimmers by Julie Otsuka – review coming to Shiny New Books on Thursday

Brood by Jackie Polzin (my review)

The Performance by Claire Thomas (my review)

Then I have a list of 16 novels I think will be longlisted mostly because of the buzz around them, or they’re the kind of thing the Prize always recognizes (like danged GREEK MYTHS), or they’re authors who have been nominated before – previous shortlistees get a free pass when it comes to publisher submissions, you see – or they’re books I might read but haven’t gotten to yet.

Predictions

Love Marriage by Monica Ali

When We Were Birds by Ayanna Lloyd Banwo

Second Place by Rachel Cusk (my review)

Matrix by Lauren Groff

Free Love by Tessa Hadley

The Other Black Girl by Zakiya Dalila Harris (my review)

The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers

The Fell by Sarah Moss (my review)

My Phantoms by Gwendoline Riley

Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney (my review)

Ariadne by Jennifer Saint

The Island of Missing Trees by Elif Shafak

Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead

Pandora by Susan Stokes-Chapman

Still Life by Sarah Winman

To Paradise by Hanya Yanagihara – currently reading

*A wildcard entry that could fit on either list: Sorrow and Bliss by Meg Mason (my review).*

Okay, no more indecision and laziness. Time to combine these two into a master list that reflects my taste but also what the judges of this prize generally seem to be looking for. It’s been a year of BIG books – seven of these are over 400 pages; three of them over 600 pages even – and a lot of historical fiction, but also some super-contemporary stuff. Seven BIPOC authors as well, which would be an improvement over last year’s five and closer to the eight from two years prior. A caveat: I haven’t given thought to publisher quotas here.

MY WOMEN’S PRIZE FORECAST

Love Marriage by Monica Ali

Our Wives Under the Sea by Julia Armfield

When We Were Birds by Ayanna Lloyd Banwo

Olga Dies Dreaming by Xóchitl González

Matrix by Lauren Groff

The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers

Devotion by Hannah Kent

Build Your House Around My Body by Violet Kupersmith

The Fell by Sarah Moss

My Phantoms by Gwendoline Riley

Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney

Ariadne by Jennifer Saint

The Island of Missing Trees by Elif Shafak

Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead

Pandora by Susan Stokes-Chapman

To Paradise by Hanya Yanagihara

What do you think?

See also Laura’s, Naty’s, and Rachel’s predictions (my final list overlaps with theirs on 10, 5 and 8 titles, respectively) and Susan’s wishes.

Just to further overwhelm you, here are the other 62 eligible 2021–22 novels that were on my radar but didn’t make the cut:

In Every Mirror She’s Black by Lola Akinmade Åkerström

Violeta by Isabel Allende

The Leviathan by Rosie Andrews

Somebody Loves You by Mona Arshi

The Stars Are Not Yet Bells by Hannah Lillith Assadi

The Manningtree Witches by A.K. Blakemore

Mary Jane by Jessica Anya Blau

Defenestrate by Renee Branum

Songs in Ursa Major by Emma Brodie

Assembly by Natasha Brown

We Were Young by Niamh Campbell

The Raptures by Jan Carson

A Very Nice Girl by Imogen Crimp

Scary Monsters by Michelle de Kretser

Empire of Wild by Cherie Dimaline

Infinite Country by Patricia Engel

Love & Saffron by Kim Fay

Mrs March by Virginia Feito

Booth by Karen Joy Fowler

Tides by Sara Freeman

I Couldn’t Love You More by Esther Freud

Of Women and Salt by Gabriela Garcia

Libertie by Kaitlyn Greenidge

Listening Still by Anne Griffin

The Twyford Code by Janice Hallett

Mrs England by Stacey Halls

Three Rooms by Jo Hamya

The Giant Dark by Sarvat Hasin

The Paper Palace by Miranda Cowley Heller

Violets by Alex Hyde

Fault Lines by Emily Itami

Beasts of a Little Land by Juhea Kim

Woman, Eating by Claire Kohda

Notes on an Execution by Danya Kukafka

Paul by Daisy Lafarge

Circus of Wonders by Elizabeth Macneal

The Truth About Her by Jacqueline Maley

Wahala by Nikki May

Once There Were Wolves by Charlotte McConaghy

Cleopatra and Frankenstein by Coco Mellors

The Exhibitionist by Charlotte Mendelson

Chouette by Claire Oshetsky

The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki

The Anthill by Julianne Pachico

The Vixen by Francine Prose

The Five Wounds by Kirstin Valdez Quade

Malibu Rising by Taylor Jenkins Reid

Cut Out by Michèle Roberts

This One Sky Day by Leone Ross

Secrets of Happiness by Joan Silber

Cold Sun by Anita Sivakumaran

Hear No Evil by Sarah Smith

Oh William! by Elizabeth Strout

Animal by Lisa Taddeo

Daughter of the Moon Goddess by Sue Lynn Tan

Lily by Rose Tremain

French Braid by Anne Tyler

We Run the Tides by Vendela Vida

I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness by Claire Vaye Watkins

Black Cake by Charmaine Wilkerson

The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams

Nightbitch by Rachel Yoder

Talking to the Dead x 2: Helen Dunmore and Elaine Feinstein

My fourth title-based dual review post this year (after Ex Libris, The Still Point and How Not to Be Afraid), with Betty vs. Bettyville to come in December if I can manage them both. Today I have an early Helen Dunmore novel about the secrets binding a pair of sisters and an Elaine Feinstein poetry collection written after the loss of her husband. Their shared title seemed appropriate as Halloween approaches. Both:

Talking to the Dead by Helen Dunmore (1996)

Nina, a photographer, has travelled to stay with her sister in Sussex after the birth of Isabel’s first child, Antony. A house full of visitors, surrounded by an unruly garden, is perfect for concealment. A current secret trades off with one from deep in the sisters’ childhood: their baby brother Colin’s death, which they remember differently. Antony and Colin function like doubles, with the sisters in subtle competition for ownership of the past and present. This was a delicious read: as close as literary fiction gets to a psychological thriller, dripping with sultry summer atmosphere and the symbols of aphrodisiac foods and blowsy flowers. From the novel’s title and opening pages, you have an inkling of what’s to come, but it still hits hard when it does. Impossible to say more about the plot without spoiling it, so just know that it’s a suspenseful story of sisters with Tessa Hadley, Maggie O’Farrell and Polly Samson vibes. I hadn’t much enjoyed my first taste of Dunmore’s fiction (Exposure), but I’m very glad that Susan’s enthusiasm spurred me to pick this up. (Secondhand purchase, Honesty bookshop outside the Castle, Hay-on-Wye)

Nina, a photographer, has travelled to stay with her sister in Sussex after the birth of Isabel’s first child, Antony. A house full of visitors, surrounded by an unruly garden, is perfect for concealment. A current secret trades off with one from deep in the sisters’ childhood: their baby brother Colin’s death, which they remember differently. Antony and Colin function like doubles, with the sisters in subtle competition for ownership of the past and present. This was a delicious read: as close as literary fiction gets to a psychological thriller, dripping with sultry summer atmosphere and the symbols of aphrodisiac foods and blowsy flowers. From the novel’s title and opening pages, you have an inkling of what’s to come, but it still hits hard when it does. Impossible to say more about the plot without spoiling it, so just know that it’s a suspenseful story of sisters with Tessa Hadley, Maggie O’Farrell and Polly Samson vibes. I hadn’t much enjoyed my first taste of Dunmore’s fiction (Exposure), but I’m very glad that Susan’s enthusiasm spurred me to pick this up. (Secondhand purchase, Honesty bookshop outside the Castle, Hay-on-Wye)

Talking to the Dead by Elaine Feinstein (2007)

Much like Margaret Atwood’s Dearly, my top poetry release of last year, this is a tender and playful response to a beloved spouse’s death. The short verses are in stanzas and incorporate the occasional end rhyme and spot of alliteration as Feinstein marshals images and memories to recreate her husband’s funeral and moments from their marriage and travels beforehand and her widowhood afterwards – including moving out of their shared home. The poems flow so easily and beautifully from one to another; I’d happily read much more from Feinstein. This was her 13th poetry collection; before her death in 2019, she also wrote many novels, stories, biographies and translations. I’ll leave you with a poem suitable for the run-up to the Day of the Dead. (Secondhand purchase, Minster Gate Bookshop, York)

Much like Margaret Atwood’s Dearly, my top poetry release of last year, this is a tender and playful response to a beloved spouse’s death. The short verses are in stanzas and incorporate the occasional end rhyme and spot of alliteration as Feinstein marshals images and memories to recreate her husband’s funeral and moments from their marriage and travels beforehand and her widowhood afterwards – including moving out of their shared home. The poems flow so easily and beautifully from one to another; I’d happily read much more from Feinstein. This was her 13th poetry collection; before her death in 2019, she also wrote many novels, stories, biographies and translations. I’ll leave you with a poem suitable for the run-up to the Day of the Dead. (Secondhand purchase, Minster Gate Bookshop, York)

Not the drink, but an alias a party guest used when he stumbled into her bedroom looking for a toilet. She was about eleven at this point and she and her brother vaguely resented being shut away from their parents’ parties. While for readers this is an uncomfortable moment as we wonder if she’s about to be molested, in memory it’s taken on a rosy glow for her – a taste of adult composure and freedom that she has sought with every partner and every glass of booze since. This was a pretty much perfect story, with a knock-out ending to boot.

Not the drink, but an alias a party guest used when he stumbled into her bedroom looking for a toilet. She was about eleven at this point and she and her brother vaguely resented being shut away from their parents’ parties. While for readers this is an uncomfortable moment as we wonder if she’s about to be molested, in memory it’s taken on a rosy glow for her – a taste of adult composure and freedom that she has sought with every partner and every glass of booze since. This was a pretty much perfect story, with a knock-out ending to boot. A 29-year-old Chinese American chef is exiled when the USA closes its borders while she’s working in London. On a smog-covered planet where 98% of crops have failed, scarcity reigns – but there is a world apart, a mountaintop settlement at the Italian border where money can buy any ingredient desired and threatened foods are cultivated in a laboratory setting. While peasants survive on mung bean flour, wealthy backers indulge in classic French cuisine. The narrator’s job is to produce lavish, evocative multi-course meals to bring investors on board. Foie gras, oysters, fine wines; heirloom vegetables; fruits not seen for years. But also endangered creatures and mystery meat wrested back from extinction. Her employer’s 21-year-old daughter, Aida, oversees the lab where these rarities are kept alive.

A 29-year-old Chinese American chef is exiled when the USA closes its borders while she’s working in London. On a smog-covered planet where 98% of crops have failed, scarcity reigns – but there is a world apart, a mountaintop settlement at the Italian border where money can buy any ingredient desired and threatened foods are cultivated in a laboratory setting. While peasants survive on mung bean flour, wealthy backers indulge in classic French cuisine. The narrator’s job is to produce lavish, evocative multi-course meals to bring investors on board. Foie gras, oysters, fine wines; heirloom vegetables; fruits not seen for years. But also endangered creatures and mystery meat wrested back from extinction. Her employer’s 21-year-old daughter, Aida, oversees the lab where these rarities are kept alive.

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris: This debut collection addresses the symptoms and side effects of breast cancer treatment at age 36, but often in oblique or cheeky ways – it can be no mistake that “assistance” appears two lines before a mention of hemorrhoids, for instance, even though it closes an epithalamium distinguished by its gentle sibilance (Farris’s husband is Ukrainian American poet Ilya Kaminsky.) She crafts sensual love poems, and exhibits Japanese influences. (Discussed in my

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris: This debut collection addresses the symptoms and side effects of breast cancer treatment at age 36, but often in oblique or cheeky ways – it can be no mistake that “assistance” appears two lines before a mention of hemorrhoids, for instance, even though it closes an epithalamium distinguished by its gentle sibilance (Farris’s husband is Ukrainian American poet Ilya Kaminsky.) She crafts sensual love poems, and exhibits Japanese influences. (Discussed in my

Hard Drive by Paul Stephenson: This wry, wrenching debut collection is an extended elegy for his partner, Tod Hartman, an American anthropologist who died of heart failure at 38. There’s every style, tone and structure imaginable here. Stephenson riffs on his partner’s oft-misspelled name (German for death), and writes of discovery, autopsy, sadmin and rituals. In “The Only Book I Took” he opens up Tod’s copy of Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking – which came from Wonder Book, the bookstore chain I worked at in Maryland!

Hard Drive by Paul Stephenson: This wry, wrenching debut collection is an extended elegy for his partner, Tod Hartman, an American anthropologist who died of heart failure at 38. There’s every style, tone and structure imaginable here. Stephenson riffs on his partner’s oft-misspelled name (German for death), and writes of discovery, autopsy, sadmin and rituals. In “The Only Book I Took” he opens up Tod’s copy of Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking – which came from Wonder Book, the bookstore chain I worked at in Maryland!

Hill keeps the setting deliberately vague, but it seems that it might be the Lincolnshire Fens in the 1930s or so. Arthur Kipps is a young lawyer tasked with attending the funeral of old Mrs Drablow and sorting through her papers. Locals don’t envy him the time spent in Eel Marsh House, and when he starts seeing a wasting-away, smallpox-pocked woman dressed in black in the churchyard, he understands why. This place harbours a malevolent ghost, and from the empty nursery with its creaking rocking chair to the marsh’s treacherous mud, Arthur fears that it’s out to get him.

Hill keeps the setting deliberately vague, but it seems that it might be the Lincolnshire Fens in the 1930s or so. Arthur Kipps is a young lawyer tasked with attending the funeral of old Mrs Drablow and sorting through her papers. Locals don’t envy him the time spent in Eel Marsh House, and when he starts seeing a wasting-away, smallpox-pocked woman dressed in black in the churchyard, he understands why. This place harbours a malevolent ghost, and from the empty nursery with its creaking rocking chair to the marsh’s treacherous mud, Arthur fears that it’s out to get him.

Although Grainier might appear to be a Job-like figure, his loneliness never shades into despair, lightened by comic dialogues and the mildest of supernatural interventions. He starts a haulage business and keeps dogs. There are rumours of a wolf-girl in the area, and, convinced that his dog’s new pups are part-wolf, he teaches them to howl – his own favourite way of letting off steam.

Although Grainier might appear to be a Job-like figure, his loneliness never shades into despair, lightened by comic dialogues and the mildest of supernatural interventions. He starts a haulage business and keeps dogs. There are rumours of a wolf-girl in the area, and, convinced that his dog’s new pups are part-wolf, he teaches them to howl – his own favourite way of letting off steam.

– but his new post-school life in Paris doesn’t have room for her. As she moves to London and trains for secretarial work, Marianne is bolstered by friendships with plain-speaking Scot Petronella (“Pet”) and Hugo Forster-Pellisier, her surfing and ping-pong partner on their parents’ Cornwall getaways. Forasmuch as her life changes over the next 15 years or so – taking on a traditional wife and homemaker role; her parents quietly declining – her attachment to her first love never falters.

– but his new post-school life in Paris doesn’t have room for her. As she moves to London and trains for secretarial work, Marianne is bolstered by friendships with plain-speaking Scot Petronella (“Pet”) and Hugo Forster-Pellisier, her surfing and ping-pong partner on their parents’ Cornwall getaways. Forasmuch as her life changes over the next 15 years or so – taking on a traditional wife and homemaker role; her parents quietly declining – her attachment to her first love never falters.

There are nine stories in the 320-page volume, so the average story here is 30–35 pages – a little longer than I tend to like, but it allows Munro to fill in enough character detail that these feel like miniature novels; they certainly have all the emotional complexity. Her material is small-town Ontario and the shifts and surprises in marriages and dysfunctional families.

There are nine stories in the 320-page volume, so the average story here is 30–35 pages – a little longer than I tend to like, but it allows Munro to fill in enough character detail that these feel like miniature novels; they certainly have all the emotional complexity. Her material is small-town Ontario and the shifts and surprises in marriages and dysfunctional families. Back in 2021, I read 14 of these 25 stories (reviewed

Back in 2021, I read 14 of these 25 stories (reviewed  Ulrich’s second collection contains 50 flash fiction pieces, most of which were first published in literary magazines. She often uses the first-person plural and especially the second person; both “we” and “you” are effective ways of implicating the reader in the action. Her work is on a speculative spectrum ranging from magic realism to horror. Some of the situations are simply bizarre – teenagers fall from the sky like rain; a woman falls in love with a giraffe; the mad scientist next door replaces a girl’s body parts with robotic ones – while others are close enough to the real world to be terrifying. The dialogue is all in italics. Some images recur later in the collection: metamorphoses, spontaneous combustion. Adolescent girls and animals are omnipresent. At a certain point this started to feel repetitive and overlong, but in general I appreciated the inventiveness.

Ulrich’s second collection contains 50 flash fiction pieces, most of which were first published in literary magazines. She often uses the first-person plural and especially the second person; both “we” and “you” are effective ways of implicating the reader in the action. Her work is on a speculative spectrum ranging from magic realism to horror. Some of the situations are simply bizarre – teenagers fall from the sky like rain; a woman falls in love with a giraffe; the mad scientist next door replaces a girl’s body parts with robotic ones – while others are close enough to the real world to be terrifying. The dialogue is all in italics. Some images recur later in the collection: metamorphoses, spontaneous combustion. Adolescent girls and animals are omnipresent. At a certain point this started to feel repetitive and overlong, but in general I appreciated the inventiveness.  I also read the first two stories in The Best Short Stories 2023: The O. Henry Prize Winners, edited by Lauren Groff. If these selections by Ling Ma and Catherine Lacey are anything to go by, Groff’s taste is for gently magical stories where hints of the absurd or explained enter into everyday life. Ma’s “Office Hours” has academics passing through closet doors into a dream space; the title of Lacey’s “Man Mountain” is literal. I’ll try to remember to occasionally open the book on my e-reader to get through the rest.

I also read the first two stories in The Best Short Stories 2023: The O. Henry Prize Winners, edited by Lauren Groff. If these selections by Ling Ma and Catherine Lacey are anything to go by, Groff’s taste is for gently magical stories where hints of the absurd or explained enter into everyday life. Ma’s “Office Hours” has academics passing through closet doors into a dream space; the title of Lacey’s “Man Mountain” is literal. I’ll try to remember to occasionally open the book on my e-reader to get through the rest. The book contains two quartets of linked stories and four stand-alone stories. The first set is about Clare and William, whose dynamic shifts from acquaintances to couple-friends to lovers to spouses. Bloom, a former psychotherapist, is interested in tracking how they navigate these changes over the years, and does so by switching between first- and third-person narration and adopting a different perspective for each story. She does the same with the four stories about Lionel and Julia, a Black man and his white stepmother. Over the course of maybe three decades, we see the constellations of relationships each one forms, while the family core remains. She also includes sexual encounters between characters who are middle-aged and older – when, according to stereotypes, lust should have been snuffed out.

The book contains two quartets of linked stories and four stand-alone stories. The first set is about Clare and William, whose dynamic shifts from acquaintances to couple-friends to lovers to spouses. Bloom, a former psychotherapist, is interested in tracking how they navigate these changes over the years, and does so by switching between first- and third-person narration and adopting a different perspective for each story. She does the same with the four stories about Lionel and Julia, a Black man and his white stepmother. Over the course of maybe three decades, we see the constellations of relationships each one forms, while the family core remains. She also includes sexual encounters between characters who are middle-aged and older – when, according to stereotypes, lust should have been snuffed out. The declarative simplicity of the prose, and the interest in male activities like gambling, hunting and fishing, can’t fail to recall Ernest Hemingway, yet I warmed to Carver much more than Hem. Two of these stories struck me as feminist for how they expose nonchalant male violence towards women; elsewhere I spotted tiny gender-transgressing details (a man who knits, for instance). In “Tell the Women We’re Going,” two men escape their families to play pool and drink, then make a fateful decision on the way home. I don’t think I’ve been as shocked by the matter-of-fact brutality of a short story since “The Lottery.” My favourite was also chilling, “So Much Water So Close to Home.” Both reveal how homosocial peer pressure leads to bad behaviour; this was toxic masculinity before we had that term.

The declarative simplicity of the prose, and the interest in male activities like gambling, hunting and fishing, can’t fail to recall Ernest Hemingway, yet I warmed to Carver much more than Hem. Two of these stories struck me as feminist for how they expose nonchalant male violence towards women; elsewhere I spotted tiny gender-transgressing details (a man who knits, for instance). In “Tell the Women We’re Going,” two men escape their families to play pool and drink, then make a fateful decision on the way home. I don’t think I’ve been as shocked by the matter-of-fact brutality of a short story since “The Lottery.” My favourite was also chilling, “So Much Water So Close to Home.” Both reveal how homosocial peer pressure leads to bad behaviour; this was toxic masculinity before we had that term. Every other story returns to Ulli, but the fragments of her life miss out the connective tissue: we suspect she’s pregnant as a teen, but don’t learn what she chose to do about it; we witness some dysfunctional scenes and realize she’s estranged from her family later on, but don’t find out if there was some big bust-up that prompted it. She comes across as a loner and a nomad, apt to be effaced by stronger personalities. In “The Ice Bear,” she’s on a ferry from Sweden back to Finland and can’t escape the prattle of a male missionary. In “A Question of Latitude” she’s out for a restaurant meal with friends, one of whom diagnoses her thus: “Nothing really affects you, does it? You just smile and put it out of your mind. And you cut people out of your life the same way, when you’ve finished with them.”

Every other story returns to Ulli, but the fragments of her life miss out the connective tissue: we suspect she’s pregnant as a teen, but don’t learn what she chose to do about it; we witness some dysfunctional scenes and realize she’s estranged from her family later on, but don’t find out if there was some big bust-up that prompted it. She comes across as a loner and a nomad, apt to be effaced by stronger personalities. In “The Ice Bear,” she’s on a ferry from Sweden back to Finland and can’t escape the prattle of a male missionary. In “A Question of Latitude” she’s out for a restaurant meal with friends, one of whom diagnoses her thus: “Nothing really affects you, does it? You just smile and put it out of your mind. And you cut people out of your life the same way, when you’ve finished with them.”

The End of Drum-Time by Hanna Pylväinen [Jan. 24, Henry Holt and Co.] I loved Pylväinen’s 2012 debut, We Sinners. This sounds like a winning combination of The Bell in the Lake and The Mercies. “A richly atmospheric saga that charts the repercussions of a scandalous nineteenth century love affair between a young Sámi reindeer herder in the Arctic Circle and the daughter of the renegade Lutheran minister whose teachings are upending the Sámi way of life.” (Edelweiss download)

The End of Drum-Time by Hanna Pylväinen [Jan. 24, Henry Holt and Co.] I loved Pylväinen’s 2012 debut, We Sinners. This sounds like a winning combination of The Bell in the Lake and The Mercies. “A richly atmospheric saga that charts the repercussions of a scandalous nineteenth century love affair between a young Sámi reindeer herder in the Arctic Circle and the daughter of the renegade Lutheran minister whose teachings are upending the Sámi way of life.” (Edelweiss download) I Have Some Questions for You by Rebecca Makkai [Feb. 21, Viking / Feb. 23, Fleet] Makkai has written a couple of stellar novels; this sounds quite different from her usual lit fic but promises Secret History vibes. “A fortysomething podcaster and mother of two, Bodie Kane is content to forget her past [, including] the murder of one of her high school classmates, Thalia Keith. … [But] when she’s invited back to Granby, the elite New England boarding school where she spent four largely miserable years, to teach a course, Bodie finds herself inexorably drawn to the case and its increasingly apparent flaws.” (Proof copy)

I Have Some Questions for You by Rebecca Makkai [Feb. 21, Viking / Feb. 23, Fleet] Makkai has written a couple of stellar novels; this sounds quite different from her usual lit fic but promises Secret History vibes. “A fortysomething podcaster and mother of two, Bodie Kane is content to forget her past [, including] the murder of one of her high school classmates, Thalia Keith. … [But] when she’s invited back to Granby, the elite New England boarding school where she spent four largely miserable years, to teach a course, Bodie finds herself inexorably drawn to the case and its increasingly apparent flaws.” (Proof copy) Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton [March 7, Granta / Farrar, Straus and Giroux] I was lukewarm on The Luminaries (my most popular

Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton [March 7, Granta / Farrar, Straus and Giroux] I was lukewarm on The Luminaries (my most popular  Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld [April 4, Random House / April 6, Doubleday] Sittenfeld is one of my favourite contemporary novelists. “Sally Milz is a sketch writer for The Night Owls, the late-night live comedy show that airs each Saturday. … Enter Noah Brewster, a pop music sensation with a reputation for dating models, who signed on as both host and musical guest for this week’s show. … Sittenfeld explores the neurosis-inducing and heart-fluttering wonder of love, while slyly dissecting the social rituals of romance and gender relations in the modern age.”

Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld [April 4, Random House / April 6, Doubleday] Sittenfeld is one of my favourite contemporary novelists. “Sally Milz is a sketch writer for The Night Owls, the late-night live comedy show that airs each Saturday. … Enter Noah Brewster, a pop music sensation with a reputation for dating models, who signed on as both host and musical guest for this week’s show. … Sittenfeld explores the neurosis-inducing and heart-fluttering wonder of love, while slyly dissecting the social rituals of romance and gender relations in the modern age.” The Last Animal by Ramona Ausubel [April 18, Riverhead] “Jane is … on the cutting-edge team of a bold project looking to ‘de-extinct’ the woolly mammoth. … As Jane and her daughters ping-pong from the slopes of Siberia to a university in California, from the shores of Iceland to an exotic animal farm in Italy, The Last Animal takes readers on an expansive, bighearted journey that explores the possibility and peril of the human imagination on a changing planet, what it’s like to be a woman and a mother in a field dominated by men, and how a wondrous discovery can best be enjoyed with family. Even teenagers.”

The Last Animal by Ramona Ausubel [April 18, Riverhead] “Jane is … on the cutting-edge team of a bold project looking to ‘de-extinct’ the woolly mammoth. … As Jane and her daughters ping-pong from the slopes of Siberia to a university in California, from the shores of Iceland to an exotic animal farm in Italy, The Last Animal takes readers on an expansive, bighearted journey that explores the possibility and peril of the human imagination on a changing planet, what it’s like to be a woman and a mother in a field dominated by men, and how a wondrous discovery can best be enjoyed with family. Even teenagers.” Saturday Night at the Lakeside Supper Club by J. Ryan Stradal [April 18, Pamela Dorman Books] Kitchens of the Great Midwest is one of my all-time favourite debuts. A repeat from my

Saturday Night at the Lakeside Supper Club by J. Ryan Stradal [April 18, Pamela Dorman Books] Kitchens of the Great Midwest is one of my all-time favourite debuts. A repeat from my  The Memory of Animals by Claire Fuller [April 20, Fig Tree (Penguin) / June 6, Tin House] Fuller is another of my favourite contemporary novelists and never disappoints. “Neffy is a young woman running away from grief and guilt … When she answers the call to volunteer in a controlled vaccine trial, it offers her a way to pay off her many debts … [and] she is introduced to a pioneering and controversial technology which allows her to revisit memories from her life before.” And apparently there’s also an octopus? (NetGalley download)

The Memory of Animals by Claire Fuller [April 20, Fig Tree (Penguin) / June 6, Tin House] Fuller is another of my favourite contemporary novelists and never disappoints. “Neffy is a young woman running away from grief and guilt … When she answers the call to volunteer in a controlled vaccine trial, it offers her a way to pay off her many debts … [and] she is introduced to a pioneering and controversial technology which allows her to revisit memories from her life before.” And apparently there’s also an octopus? (NetGalley download) The Late Americans by Brandon Taylor [May 23, Riverhead / June 22, Jonathan Cape (Penguin)] “In the shared and private spaces of Iowa City, a loose circle of lovers and friends encounter, confront, and provoke one another in a volatile year of self-discovery. … These three [main characters] are buffeted by a cast of poets, artists, landlords, meat-packing workers, and mathematicians who populate the cafes, classrooms, and food-service kitchens … [T]he group heads to a cabin to bid goodbye to their former lives—a moment of reckoning that leaves each of them irrevocably altered.” (Proof copy)

The Late Americans by Brandon Taylor [May 23, Riverhead / June 22, Jonathan Cape (Penguin)] “In the shared and private spaces of Iowa City, a loose circle of lovers and friends encounter, confront, and provoke one another in a volatile year of self-discovery. … These three [main characters] are buffeted by a cast of poets, artists, landlords, meat-packing workers, and mathematicians who populate the cafes, classrooms, and food-service kitchens … [T]he group heads to a cabin to bid goodbye to their former lives—a moment of reckoning that leaves each of them irrevocably altered.” (Proof copy) I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home by Lorrie Moore [June 20, Faber / Knopf] What a title! I’m keen to read more from Moore after her Birds of America got a 5-star rating from me late last year. “Finn is in the grip of middle-age and on an enforced break from work: it might be that he’s too emotional to teach history now. He is living in an America hurtling headlong into hysteria, after all. High up in a New York City hospice, he sits with his beloved brother Max, who is slipping from one world into the next. But when a phone call summons Finn back to a troubled old flame, a strange journey begins, opening a trapdoor in reality.”

I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home by Lorrie Moore [June 20, Faber / Knopf] What a title! I’m keen to read more from Moore after her Birds of America got a 5-star rating from me late last year. “Finn is in the grip of middle-age and on an enforced break from work: it might be that he’s too emotional to teach history now. He is living in an America hurtling headlong into hysteria, after all. High up in a New York City hospice, he sits with his beloved brother Max, who is slipping from one world into the next. But when a phone call summons Finn back to a troubled old flame, a strange journey begins, opening a trapdoor in reality.” A Manual for How to Love Us by Erin Slaughter [July 5, Harper Collins] “A debut, interlinked collection of stories exploring the primal nature of women’s grief. … Slaughter shatters the stereotype of the soft-spoken, sorrowful woman in distress, queering the domestic and honoring the feral in all of us. … Seamlessly shifting between the speculative and the blindingly real. … Set across oft-overlooked towns in the American South.” Linked short stories are irresistible for me, and I like the idea of a focus on grief.

A Manual for How to Love Us by Erin Slaughter [July 5, Harper Collins] “A debut, interlinked collection of stories exploring the primal nature of women’s grief. … Slaughter shatters the stereotype of the soft-spoken, sorrowful woman in distress, queering the domestic and honoring the feral in all of us. … Seamlessly shifting between the speculative and the blindingly real. … Set across oft-overlooked towns in the American South.” Linked short stories are irresistible for me, and I like the idea of a focus on grief. Learned by Heart by Emma Donoghue [Aug. 24, Pan Macmillan / Aug. 29, Little, Brown] Donoghue’s contemporary settings have been a little more successful for me, but she’s still a reliable author whose career I am happy to follow. “Drawing on years of investigation and Anne Lister’s five-million-word secret journal, … the long-buried love story of Eliza Raine, an orphan heiress banished from India to England at age six, and Anne Lister, a brilliant, troublesome tomboy, who meet at the Manor School for young ladies in York in 1805 … Emotionally intense, psychologically compelling, and deeply researched”.

Learned by Heart by Emma Donoghue [Aug. 24, Pan Macmillan / Aug. 29, Little, Brown] Donoghue’s contemporary settings have been a little more successful for me, but she’s still a reliable author whose career I am happy to follow. “Drawing on years of investigation and Anne Lister’s five-million-word secret journal, … the long-buried love story of Eliza Raine, an orphan heiress banished from India to England at age six, and Anne Lister, a brilliant, troublesome tomboy, who meet at the Manor School for young ladies in York in 1805 … Emotionally intense, psychologically compelling, and deeply researched”. The Year of the Cat: A Love Story by Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett [Jan. 19, Tinder Press] “When Rhiannon fell in love with, and eventually married her flatmate, she imagined they might one day move on. … The desire for a baby is never far from the surface, but … after a childhood spent caring for her autistic brother, does she really want to devote herself to motherhood? Moving through the seasons over the course of lockdown, [this] nimbly charts the way a kitten called Mackerel walked into Rhiannon’s home and heart, and taught her to face down her fears and appreciate quite how much love she had to offer.”

The Year of the Cat: A Love Story by Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett [Jan. 19, Tinder Press] “When Rhiannon fell in love with, and eventually married her flatmate, she imagined they might one day move on. … The desire for a baby is never far from the surface, but … after a childhood spent caring for her autistic brother, does she really want to devote herself to motherhood? Moving through the seasons over the course of lockdown, [this] nimbly charts the way a kitten called Mackerel walked into Rhiannon’s home and heart, and taught her to face down her fears and appreciate quite how much love she had to offer.” Fieldwork: A Forager’s Memoir by Iliana Regan [Jan. 24, Blackstone] “As Regan explores the ancient landscape of Michigan’s boreal forest, her stories of the land, its creatures, and its dazzling profusion of plant and vegetable life are interspersed with her and Anna’s efforts to make a home and a business of an inn that’s suddenly, as of their first full season there in 2020, empty of guests due to the COVID-19 pandemic. … Along the way she struggles … with her personal and familial legacies of addiction, violence, fear, and obsession—all while she tries to conceive a child that she and her immune-compromised wife hope to raise in their new home.” (Edelweiss download)

Fieldwork: A Forager’s Memoir by Iliana Regan [Jan. 24, Blackstone] “As Regan explores the ancient landscape of Michigan’s boreal forest, her stories of the land, its creatures, and its dazzling profusion of plant and vegetable life are interspersed with her and Anna’s efforts to make a home and a business of an inn that’s suddenly, as of their first full season there in 2020, empty of guests due to the COVID-19 pandemic. … Along the way she struggles … with her personal and familial legacies of addiction, violence, fear, and obsession—all while she tries to conceive a child that she and her immune-compromised wife hope to raise in their new home.” (Edelweiss download) Enchantment: Reawakening Wonder in an Exhausted Age by Katherine May [Feb. 28, Riverhead / March 9, Faber] I was a fan of her previous book, Wintering. “After years of pandemic life—parenting while working, battling anxiety about things beyond her control, feeling overwhelmed by the news-cycle and increasingly isolated—Katherine May feels bone-tired, on edge and depleted. Could there be another way to live? One that would allow her to feel less fraught and more connected, more rested and at ease, even as seismic changes unfold on the planet? Craving a different path, May begins to explore the restorative properties of the natural world”. (Proof copy)

Enchantment: Reawakening Wonder in an Exhausted Age by Katherine May [Feb. 28, Riverhead / March 9, Faber] I was a fan of her previous book, Wintering. “After years of pandemic life—parenting while working, battling anxiety about things beyond her control, feeling overwhelmed by the news-cycle and increasingly isolated—Katherine May feels bone-tired, on edge and depleted. Could there be another way to live? One that would allow her to feel less fraught and more connected, more rested and at ease, even as seismic changes unfold on the planet? Craving a different path, May begins to explore the restorative properties of the natural world”. (Proof copy) Undercurrent: A Cornish Memoir of Poverty, Nature and Resilience by Natasha Carthew [May 25, Hodder Studio] Carthew hangs around the fringes of UK nature writing, mostly considering the plight of the working class. “Carthew grew up in rural poverty in Cornwall, battling limited opportunities, precarious resources, escalating property prices, isolation and a community marked by the ravages of inequality. Her world existed alongside the postcard picture Cornwall … part-memoir, part-investigation, part love-letter to Cornwall. … This is a journey through place, and a story of hope, beauty, and fierce resilience.”

Undercurrent: A Cornish Memoir of Poverty, Nature and Resilience by Natasha Carthew [May 25, Hodder Studio] Carthew hangs around the fringes of UK nature writing, mostly considering the plight of the working class. “Carthew grew up in rural poverty in Cornwall, battling limited opportunities, precarious resources, escalating property prices, isolation and a community marked by the ravages of inequality. Her world existed alongside the postcard picture Cornwall … part-memoir, part-investigation, part love-letter to Cornwall. … This is a journey through place, and a story of hope, beauty, and fierce resilience.”