The Moomins and the Great Flood (#Moomins80) & Poetry (#ReadIndies)

To mark the 80th anniversary of Tove Jansson’s Moomins books, Kaggsy, Liz et al. are doing a readalong of the whole series, starting with The Moomins and the Great Flood. I received a copy of Sort Of Books’ 2024 reissue edition for Christmas, so I was unknowingly all set to take part. I also give quick responses to a couple of collections I read recently from two favourite indie poetry publishers in the UK, The Emma Press and Carcanet Press. These are reads 9–11 for Kaggsy and Lizzy Siddal’s Reading Independent Publishers Month challenge.

The Moomins and the Great Flood by Tove Jansson (1945; 1991)

[Translated from the Swedish by David McDuff]

Moomintroll and Moominmamma are the only two Moomins who appear here. They’re nomads, looking for a place to call home and searching for Moominpappa, who has disappeared. With them are “the creature” (later known as Sniff) and Tulippa, a beautiful flower-girl. They encounter a Serpent and a sea-troll and make a stormy journey in a boat piloted by the Hattifatteners. My favourite scene has Moominmamma rescuing a cat and her kittens from rising floodwaters. The book ends with the central pair making their way to the idyllic valley that will be the base for all their future adventures. Sort Of and Frank Cottrell Boyce, who wrote an introduction, emphasize how (climate) refugees link Jansson’s writing in 1939 to today, but it’s a subtle theme. Still, one always worth drawing attention to.

Moomintroll and Moominmamma are the only two Moomins who appear here. They’re nomads, looking for a place to call home and searching for Moominpappa, who has disappeared. With them are “the creature” (later known as Sniff) and Tulippa, a beautiful flower-girl. They encounter a Serpent and a sea-troll and make a stormy journey in a boat piloted by the Hattifatteners. My favourite scene has Moominmamma rescuing a cat and her kittens from rising floodwaters. The book ends with the central pair making their way to the idyllic valley that will be the base for all their future adventures. Sort Of and Frank Cottrell Boyce, who wrote an introduction, emphasize how (climate) refugees link Jansson’s writing in 1939 to today, but it’s a subtle theme. Still, one always worth drawing attention to.

I read my first Moomins tale in 2011 and have been reading them out of order and at random ever since; only one remains unread. Unfortunately, I did not find it rewarding to go right back to the beginning. At barely 50 pages (padded out by the Cottrell-Boyce introduction and an appendix of Jansson’s who’s-who notes), this story feels scant, offering little more than a hint of the delightful recurring characters and themes to come. Jansson had not yet given the Moomins their trademark rounded hippo-like snouts; they’re more alien and less cute here. It’s like seeing early Jim Henson drawings of Garfield before he was a fat cat. That just ain’t right. I don’t know why I’d assumed the Moomins are human-size. When you see one next to a marabou stork you realize how tiny they are; Jansson’s notes specify 20 cm tall. (Gift)

The Emma Press Anthology of Homesickness and Exile, ed. by Rachel Piercey and Emma Wright (2014)

This early anthology chimes with the review above, as well as more generally with the Moomins series’ frequent tone of melancholy and nostalgia. A couple of excerpts from Stephen Sexton’s “Skype” reveal a typical viewpoint: “That it’s strange to miss home / and be in it” and “How strange home / does not stay as it’s left.” (Such wonderfully off-kilter enjambment in the latter!) People are always changing, just as much as places – ‘You can’t go home again’; ‘You never set foot in the same river twice’ and so on. Zeina Hashem Beck captures these ideas in the first stanza of “Ten Years Later in a Different Bar”: “The city has changed like cities do; / the bar where we sang has closed. / We have changed like cities do.”

This early anthology chimes with the review above, as well as more generally with the Moomins series’ frequent tone of melancholy and nostalgia. A couple of excerpts from Stephen Sexton’s “Skype” reveal a typical viewpoint: “That it’s strange to miss home / and be in it” and “How strange home / does not stay as it’s left.” (Such wonderfully off-kilter enjambment in the latter!) People are always changing, just as much as places – ‘You can’t go home again’; ‘You never set foot in the same river twice’ and so on. Zeina Hashem Beck captures these ideas in the first stanza of “Ten Years Later in a Different Bar”: “The city has changed like cities do; / the bar where we sang has closed. / We have changed like cities do.”

Departures, arrivals; longing, regret: these are classic themes from Ovid (the inspiration for this volume) onward. Holly Hopkins and Rachel Long were additional familiar names for me to see in the table of contents. My two favourite poems were “The Restaurant at One Thousand Feet” (about the CN Tower in Toronto) by John McCullough, whose collections I’ve enjoyed before; and “The Town” by Alex Bell, which personifies a closed-minded Dorset community – “The town wraps me tight as swaddling … When I came to the town I brought things with me / from outside, and the town took them / for my own good.” Home is complicated – something one might spend an entire life searching for, or trying to escape. (New purchase from publisher)

Gold by Elaine Feinstein (2000)

I’d enjoyed Feinstein’s poetry before. The long title poem, which opens the collection, is a monologue by Lorenzo da Ponte, a collaborator of Mozart. Though I was not particularly enraptured with his story, there were some great lines here:

I’d enjoyed Feinstein’s poetry before. The long title poem, which opens the collection, is a monologue by Lorenzo da Ponte, a collaborator of Mozart. Though I was not particularly enraptured with his story, there were some great lines here:

I wanted to live with a bit of flash and brio,

rather than huddle behind ghetto gates.

The last two stanzas are especially memorable:

Poor Mozart was so much less fortunate.

My only sadness is to think of him, a pauper,

lying in his grave, while I became

Professor of Italian literature.

Nobody living can predict their fate.

I moved across the cusp of a new age,

to reach this present hour of privilege.

On this earth, luck is worth more than gold.

Politics, manners, morals all evolve

uncertainly. Best then to be bold.

Best then to be bold!

Of the discrete “Lyrics” that follow, I most liked “Options,” about a former fiancé (“who can tell how long we would have / burned together, before turning to ash?”) and “Snowdonia,” in which she’s surprised when a memory of her father resurfaces through a photograph. Talking to the Dead was more consistently engaging. (Secondhand purchase – Bridport Old Books, 2023)

Book Serendipity, Mid-April through Early June

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every few months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Fishing with dynamite takes place in Glowing Still by Sara Wheeler and In Memoriam by Alice Winn.

- Egg collecting (illegal!) is observed and/or discussed in Sea Bean by Sally Huband and The Jay, the Beech and the Limpetshell by Richard Smyth.

- Deborah Levy’s Things I Don’t Want to Know is quoted in What I’d Rather Not Think About by Jente Posthuma and Glowing Still by Sara Wheeler. I then bought a secondhand copy of the Levy on my recent trip to the States.

- “Piss-en-lit” and other folk names for dandelions are mentioned in The House of the Interpreter by Lisa Kelly and The Furrows by Namwali Serpell.

- Buttercups and nettles are mentioned in The House of the Interpreter by Lisa Kelly and Springtime in Britain by Edwin Way Teale (and other members of the Ranunculus family, which includes buttercups, in These Envoys of Beauty by Anna Vaught).

- The speaker’s heart is metaphorically described as green in a poem in Lo by Melissa Crowe and The House of the Interpreter by Lisa Kelly.

- Discussion of how an algorithm can know everything about you in Tomb Sweeping by Alexandra Chang and I’m a Fan by Sheena Patel.

- A brother drowns in The Loved Ones: Essays to Bury the Dead by Madison Davis, What I’d Rather Not Think About by Jente Posthuma, and The Furrows by Namwali Serpell.

A few cases of a book recalling a specific detail from an earlier read:

- This metaphor in The Chosen by Elizabeth Lowry links it to The Marriage Portrait by Maggie O’Farrell, another work of historical fiction I’d read not long before: “He has further misgivings about the scalloped gilt bedside table, which wouldn’t look of place in the palazzo of an Italian poisoner.”

- This reference in The Education of Harriet Hatfield by May Sarton links it back to Chase of the Wild Goose by Mary Louisa Gordon (could it be the specific book she had in mind? I suspect it was out of print in 1989, so it’s more likely it was Elizabeth Mavor’s 1971 biography The Ladies of Llangollen): “Do you have a book about those ladies, the eighteenth-century ones, who lived together in some remote place, but everyone knew them?”

- This metaphor in Things My Mother Never Told Me by Blake Morrison links it to The Chosen by Elizabeth Lowry: “Moochingly revisiting old places, I felt like Thomas Hardy in mourning for his wife.”

- A Black family is hounded out of a majority-white area by harassment in The Education of Harriet Hatfield by May Sarton and Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe.

Wartime escapees from prison camps are helped to freedom, including with the help of a German typist, in My Father’s House by Joseph O’Connor and In Memoriam by Alice Winn.

Wartime escapees from prison camps are helped to freedom, including with the help of a German typist, in My Father’s House by Joseph O’Connor and In Memoriam by Alice Winn.

- A scene of eating a deceased relative’s ashes in 19 Claws and a Black Bird by Agustina Bazterrica and The Loved Ones by Madison Davis.

- A girl lives with her flibbertigibbet mother and stern grandmother in “Wife Days,” one story from How Strange a Season by Megan Mayhew Bergman, and Jane of Lantern Hill by L.M. Montgomery.

- Macramé is mentioned in How Strange a Season by Megan Mayhew Bergman, The Memory of Animals by Claire Fuller, Floppy by Alyssa Graybeal, and Sidle Creek by Jolene McIlwain.

- A fascination with fractals in Floppy by Alyssa Graybeal and one story in Sidle Creek by Jolene McIlwain. They are also mentioned in one essay in These Envoys of Beauty by Anna Vaught.

- I found disappointed mentions of the fact that characters wear blackface in Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little Town on the Prairie in Monsters by Claire Dederer and, the very next day, Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe.

- Moon jellyfish are mentioned in the Blood and Cord anthology edited by Abi Curtis, Floppy by Alyssa Graybeal, and Sea Bean by Sally Huband.

- A Black author is grateful to their mother for preparing them for life in a white world in the memoirs-in-essays I Can’t Date Jesus by Michael Arceneaux and Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe.

- The children’s book The Owl Who Was Afraid of the Dark by Jill Tomlinson is mentioned in The Jay, the Beech and the Limpetshell by Richard Smyth and These Envoys of Beauty by Anna Vaught.

- The protagonist’s father brings home a tiger as a pet/object of display in The Marriage Portrait by Maggie O’Farrell and The Memory of Animals by Claire Fuller.

- Bloor Street, Toronto is mentioned in Jane of Lantern Hill by L.M. Montgomery and Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe.

- Ralph Waldo Emerson’s thinking about the stars is quoted in Jane of Lantern Hill by L.M. Montgomery and These Envoys of Beauty by Anna Vaught.

- Wondering whether a marine animal would be better off in captivity, where it could live much longer, in The Memory of Animals by Claire Fuller (an octopus) and Sea Bean by Sally Huband (porpoises).

Martha Gellhorn is mentioned in The Collected Regrets of Clover by Mikki Brammer and Monsters by Claire Dederer.

Martha Gellhorn is mentioned in The Collected Regrets of Clover by Mikki Brammer and Monsters by Claire Dederer.

- Characters named June in “Indigo Run,” the novella-length story in How Strange a Season by Megan Mayhew Bergman, and The Cats We Meet Along the Way by Nadia Mikail.

- “Explicate!” is a catchphrase uttered by a particular character in Girls They Write Songs About by Carlene Bauer and The Lake Shore Limited by Sue Miller.

- It’s mentioned that people used to get dressed up for going on airplanes in Fly Girl by Ann Hood and The Lights by Ben Lerner.

- Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn is a setting in The Lights by Ben Lerner and Grave by Allison C. Meier.

- Last year I read Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin, in which Oregon Trail re-enactors (in a video game) die of dysentery; this is also a live-action plot point in “Pioneers,” one story in Lydia Conklin’s Rainbow Rainbow.

- A bunch (4 or 5) of Italian American sisters in Circling My Mother by Mary Gordon and Hello Beautiful by Ann Napolitano.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Jane of Lantern Hill by L.M. Montgomery (1937) #ReadingLanternHill

I’m grateful to Canadian bloggers Naomi (Consumed by Ink) and Sarah for hosting the readalong: It’s been a pure pleasure to discover this lesser-known work by Lucy Maud Montgomery.

{SOME SPOILERS IN THE FOLLOWING}

Like Anne of Green Gables, this is a cosy novel about finding a home and a family. Fairytale-like in its ultimate optimism, it nevertheless does not avoid negative feelings. It also seemed to me ahead of its time in how it depicts parental separation.

Jane Victoria Stuart lives with her beautiful, flibbertigibbet mother and strict grandmother in a “shabby genteel” mansion on the ironically named Gay Street in Toronto. Grandmother calls her Victoria and makes her read the Bible to the family every night, a ritual Jane hates. Jane is an indifferent student, though she loves writing, and her best friend is Jody, an orphan who is in service next door. Her mother is a socialite breezing out each evening, but she doesn’t seem jolly despite all the parties. Jane has always assumed her father is dead, so it is a shock when a girl at school shares the rumour that her father is alive and living on Prince Edward Island. Apparently, divorce was difficult in Canada at that time and would have required a trip to the USA, so for nearly a decade the couple have been estranged.

It’s not just Jane who feels imprisoned on Gay Street: her mother and Jody are both suffering in their own ways, and long to live unencumbered by others’ strictures. For Jane, freedom comes when her father requests custody of her for the summer. Grandmother is of a mind to ignore the summons, but the wider family advise her to heed it. Initially apprehensive, Jane falls in love with PEI and feels like she’s known her father, a jocular writer, all the time. They’re both romantics and go hunting for a house that will feel like theirs right away. Lantern Hill fits the bill, and Jane delights in playing the housekeeper and teaching herself to cook and garden. Returning to Toronto in the autumn is a wrench, but she knows she’ll be back every summer. It’s an idyll precisely because it’s only part time; it’s a retreat.

Jane is an appealing heroine with her can-do attitude. Her everyday adventures are sweet – sheltering in a barn when the car breaks down, getting a reward and her photo in the paper for containing an escaped circus lion – but I was less enamoured with the depiction of the quirky locals. The names alone point to country bumpkin stereotypes: Shingle Snowbeam, Ding-dong, the Jimmy Johns. I did love Little Aunt Em, however, with her “I smack my lips over life” outlook. Meddlesome Aunt Irene could have been less one-dimensional; Jody’s adoption by the Titus sisters is contrived (and closest in plot to Anne); and Jane’s late illness felt unnecessary. While frequent ellipses threatened to drive me mad, Montgomery has sprightly turns of phrase: “A dog of her acquaintance stopped to speak to her, but Jane ignored him.”

Could this have been one of the earliest stories of a child who shuttles back and forth between separated or divorced parents? I wondered if it was considered edgy subject matter for Montgomery. There is, however, an indulging of the stereotypical broken-home-child fantasy of the parents still being in love and reuniting. If this is a fairytale setup, Grandmother is the evil ogre who keeps the princess(es) locked up in a gloomy castle until the noble prince’s rescue. I’m sure both Toronto and PEI are lovely in their own way – alas, I’ve never been to Canada – and by the end Montgomery offers Jane a bright future in both.

Small qualms aside, I loved reading Jane of Lantern Hill and would recommend it to anyone who enjoyed the Anne books. It’s full of the magic of childhood. What struck me most, and will stick with me, is the exploration of how the feeling of being at home (not just having a house to live in) is essential to happiness. (University library) ![]()

#ReadingLanternHill

Buy Jane of Lantern Hill from Bookshop.org [affiliate link]

#ReadIndies and Review Catch-up: Hazrat, Nettel, Peacock, Seldon

Another four selections for Read Indies month. I’m particularly pleased that two from this latest batch are “just because” books that I picked up off my shelves; another two are catch-up review copies. A few more indie titles will appear in my February roundup on Tuesday. For today, I have a fun variety: a history of the exclamation point, a Mexican novel about choosing motherhood versus being childfree, a memoir of a decades-long friendship between two poets, and a posthumous poetry collection with themes of history, illness and nature.

An Admirable Point: A brief history of the exclamation mark by Florence Hazrat (2022)

I’m definitely a punctuation geek. (My favourite punctuation mark is the semicolon, and there’s a book about it, too: Semicolon: The Past, Present, and Future of a Misunderstood Mark by Cecelia Watson, which I have on my Kindle.) One might think that strings of exclamation points are a pretty new thing – rounding off phrases in (ex-)presidential tweets, for instance – but, in fact, Hazrat opens with a Boston Gazette headline from 1788 that decried “CORRUPTION AND BRIBERY!!!” in relation to the adoption of the new Constitution.

The exclamation mark as we know it has been around since 1399, and by the 16th century its use for expression and emphasis had been codified. I was reminded of Gretchen McCulloch’s discussion of emoji in Because Internet, which also considers how written speech signifies tone, especially in the digital age. There have been various proposals for other “intonation points” over the centuries, but the question mark and exclamation mark are the two that have stuck. (Though I’m currently listening to an album called interrobang – ‽, that is. Invented by Martin Speckter in 1962; recorded by Switchfoot in 2021.)

The exclamation mark as we know it has been around since 1399, and by the 16th century its use for expression and emphasis had been codified. I was reminded of Gretchen McCulloch’s discussion of emoji in Because Internet, which also considers how written speech signifies tone, especially in the digital age. There have been various proposals for other “intonation points” over the centuries, but the question mark and exclamation mark are the two that have stuck. (Though I’m currently listening to an album called interrobang – ‽, that is. Invented by Martin Speckter in 1962; recorded by Switchfoot in 2021.)

I most enjoyed Chapter 3, on punctuation in literature. Jane Austen’s original manuscripts, replete with dashes, ampersands and exclamation points, were tidied up considerably before they made it into book form. She’s literature’s third most liberal user of exclamation marks, in terms of the number per 100,000 words, according to a chart Ben Blatt drew up in 2017, topped only by Tom Wolfe and James Joyce.

There are also sections on the use of exclamation points in propaganda and political campaigns – in conjunction with fonts, which brought to mind Simon Garfield’s Just My Type and the graphic novel ABC of Typography. It might seem to have a niche subject, but at just over 150 pages this is a cheery and diverting read for word nerds.

With thanks to Profile Books for the proof copy for review.

Still Born by Guadalupe Nettel (2020; 2022)

[Translated from the Spanish by Rosalind Harvey]

This was the Mexican author’s fourth novel; she’s also a magazine director and has published several short story collections. I’d liken it to a cross between Motherhood by Sheila Heti and (the second half of) No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood. Thirtysomething friends Laura and Alina veer off in different directions, yet end up finding themselves in similar ethical dilemmas. Laura, who narrates, is adamant that she doesn’t want children, and follows through with sterilization. However, when she becomes enmeshed in a situation with her neighbours – Doris, who’s been left by her abusive husband, and her troubled son Nicolás – she understands some of the emotional burden of motherhood. Even the pigeon nest she watches on her balcony presents a sort of morality play about parenthood.

Meanwhile, Alina and her partner Aurelio embark on infertility treatment. Laura fears losing her friend: “Alina was about to disappear and join the sect of mothers, those creatures with no life of their own who, zombie-like, with huge bags under their eyes, lugged prams around the streets of the city.” They eventually have a daughter, Inés, but learn before her birth that brain defects may cause her to die in infancy or be severely disabled. Right from the start, Alina is conflicted. Will she cling to Inés no matter her condition, or let her go? And with various unhealthy coping mechanisms to hand, will her relationship with Aurelio stay the course?

Meanwhile, Alina and her partner Aurelio embark on infertility treatment. Laura fears losing her friend: “Alina was about to disappear and join the sect of mothers, those creatures with no life of their own who, zombie-like, with huge bags under their eyes, lugged prams around the streets of the city.” They eventually have a daughter, Inés, but learn before her birth that brain defects may cause her to die in infancy or be severely disabled. Right from the start, Alina is conflicted. Will she cling to Inés no matter her condition, or let her go? And with various unhealthy coping mechanisms to hand, will her relationship with Aurelio stay the course?

Laura alternates between her life and her friends’ circumstances, taking on an omniscient voice on Nettel’s behalf – she recounts details she couldn’t possibly be privy to, at least not at the time (there’s a similar strategy in The Group by Lara Feigel). The question of what is fated versus what is chosen, also represented by Laura’s interest in tarot and palm-reading, always appeals to me. This was a wry and sharp commentary on women’s options. (Giveaway win from Bookish Chat on Twitter)

Still Born was published by Fitzcarraldo Editions in the UK and is forthcoming from Bloomsbury in the USA on August 8th.

A Friend Sails in on a Poem by Molly Peacock (2022)

I’ve read one of Peacock’s poetry collections, The Analyst, as well as her biography of Mary Delany, The Paper Garden. I was delighted when she got in touch to offer a review copy of her latest memoir, which reflects on her nearly half a century of friendship with fellow poet Phillis Levin. They met in a Johns Hopkins University writing seminar in 1976, and ever since have shared their work in progress over meals. They are seven years apart in age and their careers took different routes – Peacock headed up the Poetry Society of America’s subway poetry project and then moved to Toronto, while Levin taught at the University of Maryland – but over the years they developed “a sense of trust that really does feel familial … There is a weird way, in our conversations about poetry, that we share a single soul.” For a time they were both based in New York City and had the same therapist; more recently, they arranged annual summer poetry retreats in Cazenovia (recalled via diary entries), with just the two attendees. Jobs and lovers came and went, but their bond has endured.

The book traces their lives but also their development as poets, through examples of their verse. Her friend is “Phillis” in real life, but “Levin” when it’s her work is being discussed – and her own poems are as written by “Peacock.” Both women became devoted to the sonnet, an unusual choice because at the time that they were graduate students free verse reigned and form was something one had to learn on one’s own time. Stanza means “room,” Peacock reminds readers, and she believes there is something about form that opens up space, almost literally but certainly metaphorically, to re-examine experience. She repeatedly tracks how traumatic childhood events, as much as everyday observations, were transmuted into her poetry. Levin did so, too, but with an opposite approach: intellectual and universal where Peacock was carnal and personal. That paradox of difference yet likeness is the essence of the friendships we sail on. What a lovely read, especially if you’re curious about ‘where poems come from’; I’d particularly recommend it to fans of Ann Patchett’s Truth and Beauty.

The book traces their lives but also their development as poets, through examples of their verse. Her friend is “Phillis” in real life, but “Levin” when it’s her work is being discussed – and her own poems are as written by “Peacock.” Both women became devoted to the sonnet, an unusual choice because at the time that they were graduate students free verse reigned and form was something one had to learn on one’s own time. Stanza means “room,” Peacock reminds readers, and she believes there is something about form that opens up space, almost literally but certainly metaphorically, to re-examine experience. She repeatedly tracks how traumatic childhood events, as much as everyday observations, were transmuted into her poetry. Levin did so, too, but with an opposite approach: intellectual and universal where Peacock was carnal and personal. That paradox of difference yet likeness is the essence of the friendships we sail on. What a lovely read, especially if you’re curious about ‘where poems come from’; I’d particularly recommend it to fans of Ann Patchett’s Truth and Beauty.

With thanks to Molly Peacock and Palimpsest Press for the free e-copy for review.

The Bright White Tree by Joanna Seldon (Worple Press, 2017)

This appeared the year after Seldon died of cancer; were it not for her untimely end and her famous husband Anthony (a historian and political biographer), I’m not sure it would have been published, as the poetry is fairly mediocre, with some obvious rhymes and twee sentiments. I wouldn’t want to speak ill of the dead, though, so think of this more like a self-published work collected in tribute, and then no problem. Some of the poems were written from the Royal Marsden Hospital, with “Advice” a useful rundown of how to be there for a friend undergoing cancer treatment (text to let them know you’re thinking of them; check before calling, or visiting briefly; bring sanctioned snacks; don’t be afraid to ask after their health).

Seldon takes inspiration from history (the story of Kitty Pakenham, the bombing of the Bamiyan Buddhas), travels in England and abroad (“Robin in York” vs. “Tuscan Garden”), and family history. Her Jewish heritage is clear from poems about Israel, National Holocaust Memorial Day and Rosh Hashanah. Her own suffering is put into perspective in “A Cancer Patient Visits Auschwitz.” There are also ekphrastic responses to art and literature (a Gaugin, A Winter’s Tale, Jane Eyre, and so on). I particularly liked “Conker,” a reminder of a departed loved one “So is a good life packed full of doing / That may grow warm with others, even when / The many years have turned, and darkness filled / Places where memory shone bright and strong. / I feel the conker and feel he is here.” (New bargain book from Waterstones online sale with Christmas book token)

Seldon takes inspiration from history (the story of Kitty Pakenham, the bombing of the Bamiyan Buddhas), travels in England and abroad (“Robin in York” vs. “Tuscan Garden”), and family history. Her Jewish heritage is clear from poems about Israel, National Holocaust Memorial Day and Rosh Hashanah. Her own suffering is put into perspective in “A Cancer Patient Visits Auschwitz.” There are also ekphrastic responses to art and literature (a Gaugin, A Winter’s Tale, Jane Eyre, and so on). I particularly liked “Conker,” a reminder of a departed loved one “So is a good life packed full of doing / That may grow warm with others, even when / The many years have turned, and darkness filled / Places where memory shone bright and strong. / I feel the conker and feel he is here.” (New bargain book from Waterstones online sale with Christmas book token)

There are haikus dotted through the collection; here’s one perfect for the season:

“Snowdrops Haiku”

Maids demure, white tips to

Mob caps… Look now! They’ve

Splattered the lawn with snow

Have you discovered any new-to-you independent publishers recently?

Six Degrees: Ethan Frome to A Mother’s Reckoning

This month we began with Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton, which was our buddy read for the short classics week of Novellas in November. I reread and reviewed it recently. (See Kate’s opening post.)

#1 When I posted an excerpt of my Ethan Frome review on Instagram, I got a comment from the publicist who was involved with the recent UK release of The Smash-Up by Ali Benjamin, a modern update of Wharton’s plot. Here’s part of the blurb: “Life for Ethan and Zo used to be simple. Ethan co-founded a lucrative media start-up, and Zo was well on her way to becoming a successful filmmaker. Then they moved to a rural community for a little more tranquility—or so they thought. … Enter a houseguest who is young, fun, and not at all concerned with the real world, and Ethan is abruptly forced to question everything: his past, his future, his marriage, and what he values most.” I’m going to try to get hold of a review copy when the paperback comes out in February.

#1 When I posted an excerpt of my Ethan Frome review on Instagram, I got a comment from the publicist who was involved with the recent UK release of The Smash-Up by Ali Benjamin, a modern update of Wharton’s plot. Here’s part of the blurb: “Life for Ethan and Zo used to be simple. Ethan co-founded a lucrative media start-up, and Zo was well on her way to becoming a successful filmmaker. Then they moved to a rural community for a little more tranquility—or so they thought. … Enter a houseguest who is young, fun, and not at all concerned with the real world, and Ethan is abruptly forced to question everything: his past, his future, his marriage, and what he values most.” I’m going to try to get hold of a review copy when the paperback comes out in February.

#2 One of my all-time favourite debut novels is The Innocents by Francesca Segal, which won the Costa First Novel Award in 2012. It is also a contemporary reworking of an Edith Wharton novel, this time The Age of Innocence. Segal’s love triangle, set in a world I know very little about (the tight-knit Jewish community of northwest London), stays true to the emotional content of the original: the interplay of love and desire, jealousy and frustration. Adam Newman has been happily paired with Rachel Gilbert for nearly 12 years. Now engaged, Adam and Rachel seem set to become pillars of the community. Suddenly, their future is threatened by the return of Rachel’s bad-girl American cousin, Ellie Schneider.

#2 One of my all-time favourite debut novels is The Innocents by Francesca Segal, which won the Costa First Novel Award in 2012. It is also a contemporary reworking of an Edith Wharton novel, this time The Age of Innocence. Segal’s love triangle, set in a world I know very little about (the tight-knit Jewish community of northwest London), stays true to the emotional content of the original: the interplay of love and desire, jealousy and frustration. Adam Newman has been happily paired with Rachel Gilbert for nearly 12 years. Now engaged, Adam and Rachel seem set to become pillars of the community. Suddenly, their future is threatened by the return of Rachel’s bad-girl American cousin, Ellie Schneider.

#3 Also set in north London’s Jewish community is The Marrying of Chani Kaufman by Eve Harris, which was longlisted for the Booker Prize in 2013. Chani is the fifth of eight daughters in an ultra-Orthodox Jewish family in Golders Green. The story begins and closes with Chani and Baruch’s wedding ceremony, and in between it loops back to detail their six-month courtship and highlight a few events from their family past. It’s a light-hearted, gossipy tale of interclass matchmaking in the Jane Austen vein.

#3 Also set in north London’s Jewish community is The Marrying of Chani Kaufman by Eve Harris, which was longlisted for the Booker Prize in 2013. Chani is the fifth of eight daughters in an ultra-Orthodox Jewish family in Golders Green. The story begins and closes with Chani and Baruch’s wedding ceremony, and in between it loops back to detail their six-month courtship and highlight a few events from their family past. It’s a light-hearted, gossipy tale of interclass matchmaking in the Jane Austen vein.

#4 I learned more about Jewish beliefs and rituals via several memoirs, including Between Gods by Alison Pick. Her paternal grandparents escaped Czechoslovakia just before the Holocaust; she only found out that her father was Jewish through eavesdropping. In 2008 the author (a Toronto-based novelist and poet) decided to convert to Judaism. The book vividly depicts a time of tremendous change, covering a lot of other issues Pick was dealing with simultaneously, such as depression, preparation for marriage, pregnancy, and so on.

#4 I learned more about Jewish beliefs and rituals via several memoirs, including Between Gods by Alison Pick. Her paternal grandparents escaped Czechoslovakia just before the Holocaust; she only found out that her father was Jewish through eavesdropping. In 2008 the author (a Toronto-based novelist and poet) decided to convert to Judaism. The book vividly depicts a time of tremendous change, covering a lot of other issues Pick was dealing with simultaneously, such as depression, preparation for marriage, pregnancy, and so on.

#5 One small element of Pick’s story was her decision to be tested for the BRCA gene because it’s common among Ashkenazi Jews. Tay-Sachs disease is usually found among Ashkenazi Jews, but because only her husband was Jewish, Emily Rapp never thought to be tested before she became pregnant with her son Ronan. Had she known she was also a carrier, things might have gone differently. The Still Point of the Turning World was written while her young son was still alive, but terminally ill.

#5 One small element of Pick’s story was her decision to be tested for the BRCA gene because it’s common among Ashkenazi Jews. Tay-Sachs disease is usually found among Ashkenazi Jews, but because only her husband was Jewish, Emily Rapp never thought to be tested before she became pregnant with her son Ronan. Had she known she was also a carrier, things might have gone differently. The Still Point of the Turning World was written while her young son was still alive, but terminally ill.

#6 Another wrenching memoir of losing a son: A Mother’s Reckoning by Sue Klebold, whose son Dylan was one of the Columbine school shooters. I was in high school myself at the time, and the event made a deep impression on me. Perhaps the most striking thing about this book is Klebold’s determination to reclaim Columbine as a murder–suicide and encourage mental health awareness; all author proceeds were donated to suicide prevention and mental health charities. There’s no real redemptive arc, though, no easy answers; just regrets. If something similar could happen to any family, no one is immune. And Columbine was only one of many major shootings. I finished this feeling spent, even desolate. Yet this is a vital book everyone should read.

#6 Another wrenching memoir of losing a son: A Mother’s Reckoning by Sue Klebold, whose son Dylan was one of the Columbine school shooters. I was in high school myself at the time, and the event made a deep impression on me. Perhaps the most striking thing about this book is Klebold’s determination to reclaim Columbine as a murder–suicide and encourage mental health awareness; all author proceeds were donated to suicide prevention and mental health charities. There’s no real redemptive arc, though, no easy answers; just regrets. If something similar could happen to any family, no one is immune. And Columbine was only one of many major shootings. I finished this feeling spent, even desolate. Yet this is a vital book everyone should read.

So, I’ve gone from one unremittingly bleak book to another, via sex, religion and death. Nothing for cheerful holiday reading – or a polite dinner party conversation – here! All my selections were by women this month.

Where will your chain take you? Join us for #6Degrees of Separation! (Hosted on the first Saturday of each month by Kate W. of Books Are My Favourite and Best.)

Next month’s starting point is Rules of Civility by Amor Towles; I have a copy on the shelf and this would be a good excuse to read it!

Have you read any of my selections? Are you tempted by any you didn’t know before?

A Few Bizarre Backlist Reads: McEwan, Michaels & Tremain

I’ve grouped these three prize-winning novels from the late 1980s and 1990s together because they all left me scratching my head, wondering whether they were jumbles of random elements and events or if there was indeed a satisfyingly coherent story. While there were aspects I admired, there were also moments when I thought it indulgent of the authors to pursue poetic prose or plot tangents and not consider the reader’s limited patience. I had to think for ages about how to rate these, but eventually arrived at the same rating for each, reflecting my enjoyment but also my hesitation. ![]()

The Child in Time by Ian McEwan (1987)

[Whitbread Prize for Fiction (now Costa Novel Award)]

This is the second-earliest of the 13 McEwan books I’ve read. It’s something of a strange muddle (from the protagonist’s hobbies of Arabic and tennis lessons plus drinking onwards), yet everything clusters around the title’s announced themes of children and time.

This is the second-earliest of the 13 McEwan books I’ve read. It’s something of a strange muddle (from the protagonist’s hobbies of Arabic and tennis lessons plus drinking onwards), yet everything clusters around the title’s announced themes of children and time.

Stephen Lewis’s three-year-old daughter, Kate, was abducted from a supermarket three years ago. The incident is recalled early in the book, as if the remainder will be about solving the mystery of what happened to Kate. But such is not the case. Her disappearance is an unalterable fact of Stephen’s life that drove him and his wife apart, but apart from one excruciating scene later in the book when he mistakes a little girl on a school playground for Kate and interrogates the principal about her, the missing child is just subtext.

Instead, the tokens of childhood are political and fanciful. Stephen, a writer whose novels accidentally got categorized as children’s books, is on a government committee producing a report on childcare. On a visit to Suffolk, he learns that his publisher, Charles Darke, who later became an MP, has reverted to childhood, wearing shorts and serving lemonade up in a treehouse.

Meanwhile, Charles’s wife, Thelma, is a physicist researching the nature of time. For Charles, returning to childhood is a way of recapturing timelessness. There’s also an odd shared memory that Stephen and his mother had four decades apart. Even tiny details add on to the time theme, like Stephen’s parents meeting when his father returned a defective clock to the department store where his mother worked.

This is McEwan, so you know there’s going to be a contrived but very funny scene. Here that comes in Chapter 5, when Stephen is behind a flipped lorry and goes to help the driver. He agrees to take down a series of (increasingly outrageous) dictated letters but gets exasperated at about the same time it becomes clear the young man is not approaching death. Instead, he helps him out of the cab and they celebrate by drinking two bottles of champagne. This doesn’t seem to have much bearing on the rest of the book, but is the scene I’m most likely to remember.

Other noteworthy elements: Stephen has a couple of run-ins with the Prime Minister; though this is clearly Margaret Thatcher, McEwan takes pains to neither name nor so much as reveal the gender of the PM (in fear of libel claims?). Homeless people and gypsies show up multiple times, making Stephen uncomfortable but also drawing his attention. I assumed this was a political point about Thatcher’s influence, with the homeless serving as additional stand-ins for children in a paternalistic society, representing vulnerability and (misplaced) trust.

This is a book club read for our third monthly Zoom meeting, coming up in the first week of June. While it’s odd and not entirely successful, I think it should give us a lot to talk about: the good and bad aspects of reverting to childhood, whether it matters if Kate ever comes back, the caginess about Thatcher, and so on.

Fugitive Pieces by Anne Michaels (1996)

[Orange Prize (now Women’s Prize for Fiction)]

“One can look deeply for meaning or one can invent it.”

Poland, Greece, Canada; geology, poetry, meteorology. At times it felt like Michaels had picked her settings and topics out of a hat and flung them together. Especially in the early pages, the dreamy prose is so close to poetry that I had trouble figuring out what was actually happening, but gradually I was drawn into the story of Jakob Beer, a Jewish boy rescued like a bog body or golem from the ruins of his Polish village. Raised on a Greek island and in Toronto by his adoptive father, a geologist named Athos who’s determined to combat the Nazi falsifying of archaeological history, Jakob becomes a poet and translator. Though he marries twice, he remains a lonely genius haunted by the loss of his whole family – especially his sister, Bella, who played the piano. Survivor’s guilt never goes away. “To survive was to escape fate. But if you escape your fate, whose life do you then step into?”

Poland, Greece, Canada; geology, poetry, meteorology. At times it felt like Michaels had picked her settings and topics out of a hat and flung them together. Especially in the early pages, the dreamy prose is so close to poetry that I had trouble figuring out what was actually happening, but gradually I was drawn into the story of Jakob Beer, a Jewish boy rescued like a bog body or golem from the ruins of his Polish village. Raised on a Greek island and in Toronto by his adoptive father, a geologist named Athos who’s determined to combat the Nazi falsifying of archaeological history, Jakob becomes a poet and translator. Though he marries twice, he remains a lonely genius haunted by the loss of his whole family – especially his sister, Bella, who played the piano. Survivor’s guilt never goes away. “To survive was to escape fate. But if you escape your fate, whose life do you then step into?”

The final third of the novel, set after Jakob’s death, shifts into another first-person voice. Ben is a student of literature and meteorological history. His parents are concentration camp survivors, so he relates to the themes of loss and longing in Jakob’s poetry. Taking a break from his troubled marriage, Ben offers to go back to the Greek island where Jakob last lived to retrieve his notebooks – which presumably contain all that’s come before. Ben often addresses Jakob directly in the second person, as if to reassure him that he has been remembered. Ultimately, I wasn’t sure what this section was meant to add, but Ben’s narration is more fluent than Jakob’s, so it was at least pleasant to read.

Although this is undoubtedly overwritten in places, too often resorting to weighty one-liners, I found myself entranced by the stylish writing most of the time. I particularly enjoyed the puns, palindromes and rhyming slang that Jakob shares with Athos while learning English, and with his first wife. If I could change one thing, I would boost the presence of the female characters. I was reminded of other books I’ve read about the interpretation of history and memory, Everything Is Illuminated and Moon Tiger, as well as of other works by Canadian women, A Student of Weather and Fall on Your Knees. This won’t be a book for everyone, but if you’ve enjoyed one or more of my readalikes, you might consider giving it a try.

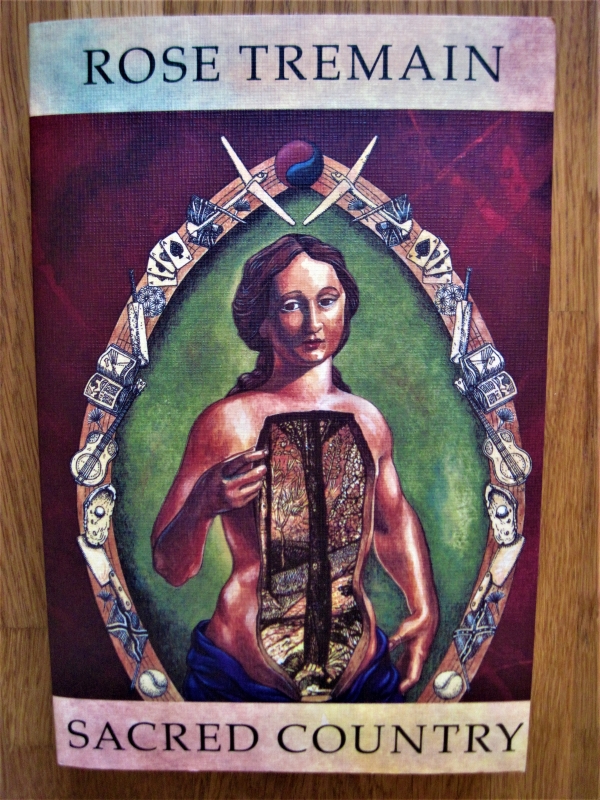

Sacred Country by Rose Tremain (1992)

[James Tait Black Memorial Prize, Prix Fémina Etranger]

In 1952, on the day a two-minute silence is held for the dead king, six-year-old Mary Ward has a distinct thought: “I am not Mary. That is a mistake. I am not a girl. I’m a boy.” Growing up on a Suffolk farm with a violent father and a mentally ill mother, Mary asks to be called Martin and binds her breasts with bandages. Kicked out at age 15, she lives with her retired teacher and then starts to pursue a life on her own terms in London. While working for a literary magazine and dating women, she consults a doctor and psychologist to explore the hormonal and surgical options for becoming the man she believes she’s always been.

Meanwhile, a hometown acquaintance with whom she once shared a dentist’s waiting room, Walter Loomis, gives up his family’s butcher shop to pursue his passion for country music. Both he and Mary/Martin are sexually fluid and, dissatisfied with the existence they were born into, resolve to search for something more. The outsiders’ journeys take them to Tennessee, of all places. But when Martin joins Walter there, it’s an anticlimax. You’d expect their new lives to dovetail together, but instead they remain separate strivers.

At a bare summary, this seems like a simple plot, but Tremain complicates it with many minor characters and subplots. The story line stretches to 1980: nearly three decades’ worth of historical and social upheaval. The third person narration shifts perspective often to show a whole breadth of experience in this small English village, while occasional first-person passages from Mary and from her mother, Estelle, who’s in and out of a mental hospital, lend intimacy. Otherwise, the minor characters feel flat, more like symbols or mouthpieces.

To give a flavor of the book’s many random elements, here’s a decoding of the extraordinary cover on the copy I picked up from the free bookshop:

Crimson background and oval shape = female anatomy, menstruation

Central figure in a medieval painting style, with royal blue cloth = Mary

Masculine muscle structure plus yin-yang at top = blended sexuality

Airplane = Estelle’s mother died in a glider accident

Confederate flag = Tennessee

Cards = fate/chance, conjuring tricks Mary learns at school, fortune teller Walter visits

Cleaver = the Loomis butcher shop

Cricket bat = Edward Harker’s woodcraft; he employs and then marries Estelle’s friend Irene

Guitar = Walter’s country music ambitions

Oyster shell with pearl = Irene’s daughter Pearl, whom young Mary loves so much she takes her (then a baby) in to school for show-and-tell

Cutout torso = the search for the title land (both inward and outer), a place beyond duality

Tremain must have been ahead of the times in writing a trans character. She acknowledged that the premise was inspired by Conundrum by Jan Morris (who, born James, knew he was really a girl from the age of five). I recall that Sacred Country turned up often in the footnotes of Tremain’s recent memoir, Rosie, so I expect it has little autobiographical resonances and is a work she’s particularly proud of. I read this in advance of writing a profile of Tremain for Bookmarks magazine. It feels very different from her other books I’ve read; while it’s not as straightforwardly readable as The Road Home, I’d call it my second favorite from her. The writing is somewhat reminiscent of Kate Atkinson, early A.S. Byatt and Shena Mackay, and it’s a memorable exploration of hidden identity and the parts of life that remain a mystery.

Various Miracles was published in 1985, when Shields was 50. She was still a decade from finding success for her best-known works, The Stone Diaries and Larry’s Party, and so far had published poetry, criticism and several novels. The title story’s string of coincidences and the final story, sharing a title with one of her poetry volumes (“Others”), neatly express the book’s concerns with chance and how we relate to other people and imagine their lives. I was disoriented by first starting the UK paperback (Fourth Estate, 1994). I had no idea it’s a selection; a number of the stories appear in the Collected volume under her next title, The Orange Fish. Before I realized that, I’d read two interlopers, including “Hazel,” which also spotlights the theme of coincidence. “Everything is an accident, Hazel would be willing to say if asked. Her whole life is an accident, and by accident she has blundered into the heart of it,” stumbling into a sales career during her widowhood.

Various Miracles was published in 1985, when Shields was 50. She was still a decade from finding success for her best-known works, The Stone Diaries and Larry’s Party, and so far had published poetry, criticism and several novels. The title story’s string of coincidences and the final story, sharing a title with one of her poetry volumes (“Others”), neatly express the book’s concerns with chance and how we relate to other people and imagine their lives. I was disoriented by first starting the UK paperback (Fourth Estate, 1994). I had no idea it’s a selection; a number of the stories appear in the Collected volume under her next title, The Orange Fish. Before I realized that, I’d read two interlopers, including “Hazel,” which also spotlights the theme of coincidence. “Everything is an accident, Hazel would be willing to say if asked. Her whole life is an accident, and by accident she has blundered into the heart of it,” stumbling into a sales career during her widowhood. By contrast, my favourites went deep with a few characters, or reflected on the writer’s craft. “Fragility” has a couple moving from Toronto to Vancouver, starting a new life and looking for a house that gives off good vibrations (not “a divorce house”). The slow reveal of the catalyzing incident with their son is devastating. With “Others,” Shields (or editors) saved the best for last. On honeymoon in France, Robert and Lila help a fellow English-speaking couple by cashing a check for them. Every year thereafter, Nigel and Jane send them a Christmas card, winging its way from England to Canada. Robert and Lila romanticize these people they met all of once. The plot turns on what is in those pithy 1–2-sentence annual updates versus what remains unspoken. “Love so Fleeting, Love so Fine,” too, involves filling in an entire backstory for an unknown character. Another favourite was “Poaching,” about friends touring England and picking up hitchhikers, whose stories they appropriate.

By contrast, my favourites went deep with a few characters, or reflected on the writer’s craft. “Fragility” has a couple moving from Toronto to Vancouver, starting a new life and looking for a house that gives off good vibrations (not “a divorce house”). The slow reveal of the catalyzing incident with their son is devastating. With “Others,” Shields (or editors) saved the best for last. On honeymoon in France, Robert and Lila help a fellow English-speaking couple by cashing a check for them. Every year thereafter, Nigel and Jane send them a Christmas card, winging its way from England to Canada. Robert and Lila romanticize these people they met all of once. The plot turns on what is in those pithy 1–2-sentence annual updates versus what remains unspoken. “Love so Fleeting, Love so Fine,” too, involves filling in an entire backstory for an unknown character. Another favourite was “Poaching,” about friends touring England and picking up hitchhikers, whose stories they appropriate.

This came highly recommended by

This came highly recommended by

I’m also halfway through High Spirits: A Collection of Ghost Stories (1982) by Robertson Davies and enjoying it immensely. Davies was a Master of Massey College at the University of Toronto. These 18 stories, one for each year of his tenure, were his contribution to the annual Christmas party entertainment. They are short and slightly campy tales told in the first person by an intellectual who definitely doesn’t believe in ghosts – until one is encountered. The spirits are historic royals, politicians, writers or figures from legend. In a pastiche of the classic ghost story à la M.R. James, the pompous speaker is often a scholar of some esoteric field and gives elaborate descriptions. “When Satan Goes Home for Christmas” and “Dickens Digested” are particularly amusing. This will make a perfect bridge between Halloween and Christmas. (National Trust secondhand shop)

I’m also halfway through High Spirits: A Collection of Ghost Stories (1982) by Robertson Davies and enjoying it immensely. Davies was a Master of Massey College at the University of Toronto. These 18 stories, one for each year of his tenure, were his contribution to the annual Christmas party entertainment. They are short and slightly campy tales told in the first person by an intellectual who definitely doesn’t believe in ghosts – until one is encountered. The spirits are historic royals, politicians, writers or figures from legend. In a pastiche of the classic ghost story à la M.R. James, the pompous speaker is often a scholar of some esoteric field and gives elaborate descriptions. “When Satan Goes Home for Christmas” and “Dickens Digested” are particularly amusing. This will make a perfect bridge between Halloween and Christmas. (National Trust secondhand shop)

The protagonist is a young mixed-race woman working behind the reception desk at a hotel in Sokcho, a South Korean resort at the northern border. A tourist mecca in high season, during the frigid months this beach town feels down-at-heel, even sinister. The arrival of a new guest is a major event at the guesthouse. And not just any guest but Yan Kerrand, a French graphic novelist. Although she has a boyfriend and the middle-aged Kerrand is probably old enough to be her father – and thus an uncomfortable stand-in for her absent French father – the narrator is drawn to him. She accompanies him on sightseeing excursions but wants to go deeper in his life, rifling through his rubbish for scraps of work in progress.

The protagonist is a young mixed-race woman working behind the reception desk at a hotel in Sokcho, a South Korean resort at the northern border. A tourist mecca in high season, during the frigid months this beach town feels down-at-heel, even sinister. The arrival of a new guest is a major event at the guesthouse. And not just any guest but Yan Kerrand, a French graphic novelist. Although she has a boyfriend and the middle-aged Kerrand is probably old enough to be her father – and thus an uncomfortable stand-in for her absent French father – the narrator is drawn to him. She accompanies him on sightseeing excursions but wants to go deeper in his life, rifling through his rubbish for scraps of work in progress. Norman is a really underrated writer and I’m a big fan of

Norman is a really underrated writer and I’m a big fan of  The Snow Queen by Hans Christian Andersen [adapted by Geraldine McCaughrean; illus. Laura Barrett] (2019): The whole is in the shadow painting style shown on the cover, with a black, white and ice blue palette. It’s visually stunning, but I didn’t like the language as much as in the original (or at least older) version I remember from a book I read every Christmas as a child.

The Snow Queen by Hans Christian Andersen [adapted by Geraldine McCaughrean; illus. Laura Barrett] (2019): The whole is in the shadow painting style shown on the cover, with a black, white and ice blue palette. It’s visually stunning, but I didn’t like the language as much as in the original (or at least older) version I remember from a book I read every Christmas as a child.  A Polar Bear in the Snow by Mac Barnett [art by Shawn Harris] (2020): From a grey-white background, a bear’s face emerges. The remaining pages are made of torn and cut paper that looks more three-dimensional than it really is. The bear passes other Arctic creatures and plays in the sea. Such simple yet intricate spreads.

A Polar Bear in the Snow by Mac Barnett [art by Shawn Harris] (2020): From a grey-white background, a bear’s face emerges. The remaining pages are made of torn and cut paper that looks more three-dimensional than it really is. The bear passes other Arctic creatures and plays in the sea. Such simple yet intricate spreads.  Snow Day by Richard Curtis [illus. Rebecca Cobb] (2014): When snow covers London one December, only two people fail to get the message that the school is closed: Danny Higgins and Mr Trapper, his nemesis. So lessons proceed. At first it feels like a prison sentence, but at break time Mr Trapper gives in to the holiday atmosphere. These two lonely souls play as if they were both children, making an army of snowmen and an igloo. And next year, they’ll secretly do it all again. Watch out for the recurring robin in a woolly hat.

Snow Day by Richard Curtis [illus. Rebecca Cobb] (2014): When snow covers London one December, only two people fail to get the message that the school is closed: Danny Higgins and Mr Trapper, his nemesis. So lessons proceed. At first it feels like a prison sentence, but at break time Mr Trapper gives in to the holiday atmosphere. These two lonely souls play as if they were both children, making an army of snowmen and an igloo. And next year, they’ll secretly do it all again. Watch out for the recurring robin in a woolly hat.  The Snowflake by Benji Davies (2020): I didn’t realize this was a Christmas story, but no matter. A snowflake starts her lonely journey down from a cloud; on Earth, Noelle hopes for snow to fall on her little Christmas tree. From motorway to town to little isolated house, Davies has an eye for colour and detail.

The Snowflake by Benji Davies (2020): I didn’t realize this was a Christmas story, but no matter. A snowflake starts her lonely journey down from a cloud; on Earth, Noelle hopes for snow to fall on her little Christmas tree. From motorway to town to little isolated house, Davies has an eye for colour and detail.  Bear and Hare: SNOW! by Emily Gravett (2014): Bear and Hare, wearing natty scarves, indulge in all the fun activities a blizzard brings: snow angels, building snow creatures, having a snowball fight and sledging. Bear seems a little wary, but Hare wins him over. The illustration style reminded me of Axel Scheffler’s work for Julia Donaldson.

Bear and Hare: SNOW! by Emily Gravett (2014): Bear and Hare, wearing natty scarves, indulge in all the fun activities a blizzard brings: snow angels, building snow creatures, having a snowball fight and sledging. Bear seems a little wary, but Hare wins him over. The illustration style reminded me of Axel Scheffler’s work for Julia Donaldson.  Snow Ghost by Tony Mitton [illus. Diana Mayo] (2020): Snow Ghost looks for somewhere she might rest, drifting over cities and through woods until she finds the rural home of a boy and girl who look ready to welcome her. Nice pastel art but twee couplets.

Snow Ghost by Tony Mitton [illus. Diana Mayo] (2020): Snow Ghost looks for somewhere she might rest, drifting over cities and through woods until she finds the rural home of a boy and girl who look ready to welcome her. Nice pastel art but twee couplets.  Rabbits in the Snow: A Book of Opposites by Natalie Russell (2012): A suite of different coloured rabbits explore large and small, full and empty, top and bottom, and so on. After building a snowman and sledging, they come inside for some carrot soup.

Rabbits in the Snow: A Book of Opposites by Natalie Russell (2012): A suite of different coloured rabbits explore large and small, full and empty, top and bottom, and so on. After building a snowman and sledging, they come inside for some carrot soup.  The Snowbear by Sean Taylor [illus. Claire Alexander] (2017): Iggy and Martina build a snowman that looks more like a bear. Even though their mum has told them not to, they sledge into the woods and encounter danger, but the snow bear briefly comes alive and walks down the hill to save them. Delightful.

The Snowbear by Sean Taylor [illus. Claire Alexander] (2017): Iggy and Martina build a snowman that looks more like a bear. Even though their mum has told them not to, they sledge into the woods and encounter danger, but the snow bear briefly comes alive and walks down the hill to save them. Delightful.

Snow (2014) & Lost (2021) by Sam Usher: A cute pair from a set of series about a little ginger boy and his grandfather. The boy is frustrated with how slow and stick-in-the-mud his grandpa seems to be, yet he comes through with magic. In the former, it’s a snow day and the boy feels like he’s missing all the fun until zoo animals come out to frolic. There’s lots of white space to simulate the snow. In the latter, they build a sledge and help search for a lost dog. Once again, ‘wild’ animals come to the rescue.

Snow (2014) & Lost (2021) by Sam Usher: A cute pair from a set of series about a little ginger boy and his grandfather. The boy is frustrated with how slow and stick-in-the-mud his grandpa seems to be, yet he comes through with magic. In the former, it’s a snow day and the boy feels like he’s missing all the fun until zoo animals come out to frolic. There’s lots of white space to simulate the snow. In the latter, they build a sledge and help search for a lost dog. Once again, ‘wild’ animals come to the rescue.  The Lights that Dance in the Night by Yuval Zommer (2021): I’ve seen Zommer speak as part of a

The Lights that Dance in the Night by Yuval Zommer (2021): I’ve seen Zommer speak as part of a

I only found four stand-outs here. “Reasonable Terms” is a playful piece of magic realism in which a zoo’s giraffes get the gorilla to write out a list of demands for their keepers and, when agreement isn’t forthcoming, stage a mass mock suicide. In “How to Revitalize the Snake in Your Life,” a woman takes revenge on her boa constrictor-keeping boyfriend. In “Miss Waldron’s Red Colobus,” which reminded me of Ned Beauman’s madcap style, a boarding school teenager eludes the private detectives her parents have hired to keep tabs on her and makes it all the way to Ghana, where a new species of monkey is named after her. My favorite of all was “Preservation,” in which Mary saves wildlife paintings through her work as an art conservator but can’t save her father from terminal illness.

I only found four stand-outs here. “Reasonable Terms” is a playful piece of magic realism in which a zoo’s giraffes get the gorilla to write out a list of demands for their keepers and, when agreement isn’t forthcoming, stage a mass mock suicide. In “How to Revitalize the Snake in Your Life,” a woman takes revenge on her boa constrictor-keeping boyfriend. In “Miss Waldron’s Red Colobus,” which reminded me of Ned Beauman’s madcap style, a boarding school teenager eludes the private detectives her parents have hired to keep tabs on her and makes it all the way to Ghana, where a new species of monkey is named after her. My favorite of all was “Preservation,” in which Mary saves wildlife paintings through her work as an art conservator but can’t save her father from terminal illness.  The first half of the book reports Manuel’s life in the third person, while the second is in the first person, narrated by his son, Antonio. Through that shift in perspective we come to see Manuel as both a comic and a tragic figure: he insists on speaking English, but his grammar and accent are atrocious; he cultivates proud Canadian traditions, like playing the anthem on repeat on Canada Day and spending Christmas Eve at Niagara Falls, but he’s also a drunk the neighborhood children laugh at. Although the two chapters set back in Portugal were my favorites, Manuel is a compelling, sympathetic character throughout, and I appreciated De Sa’s picture of the immigrant’s contrasting feelings of home and community. Particularly recommended if you’ve enjoyed That Time I Loved You by Carrianne Leung.

The first half of the book reports Manuel’s life in the third person, while the second is in the first person, narrated by his son, Antonio. Through that shift in perspective we come to see Manuel as both a comic and a tragic figure: he insists on speaking English, but his grammar and accent are atrocious; he cultivates proud Canadian traditions, like playing the anthem on repeat on Canada Day and spending Christmas Eve at Niagara Falls, but he’s also a drunk the neighborhood children laugh at. Although the two chapters set back in Portugal were my favorites, Manuel is a compelling, sympathetic character throughout, and I appreciated De Sa’s picture of the immigrant’s contrasting feelings of home and community. Particularly recommended if you’ve enjoyed That Time I Loved You by Carrianne Leung.