Local Resistance: On Gallows Down by Nicola Chester

It’s mostly by accident that we came to live in Newbury: five years ago, when a previous landlord served us notice, we viewed a couple of rental houses in the area to compare with what was available in Reading and discovered that our money got us more that little bit further out from London. We’ve come to love this part of West Berkshire and the community we’ve found. It may not be flashy or particularly famous, but it has natural wonders worth celebrating and a rich history of rebellion that Nicola Chester plumbs in On Gallows Down. A hymn-like memoir of place as much as of one person’s life, her book posits that the quiet moments of connection with nature and the rights of ordinary people are worth fighting for.

So many layers of history mingle here: from the English Civil War onward, Newbury has been a locus of resistance for centuries. Nicola* has personal memories of the long-running women’s peace camps at Greenham Common, once a U.S. military base and cruise missile storage site – to go with the Atomic Weapons Establishment down the road at Aldermaston. As a teenager and young woman, she took part in symbolic protests against the Twyford Down and Newbury Bypass road-building projects, which went ahead and destroyed much sensitive habitat and many thousands of trees. Today, through local and national newspaper and magazine columns on wildlife, and through her winsome nagging of the managers of the Estate she lives on, she bears witness to damaging countryside management and points to a better way.

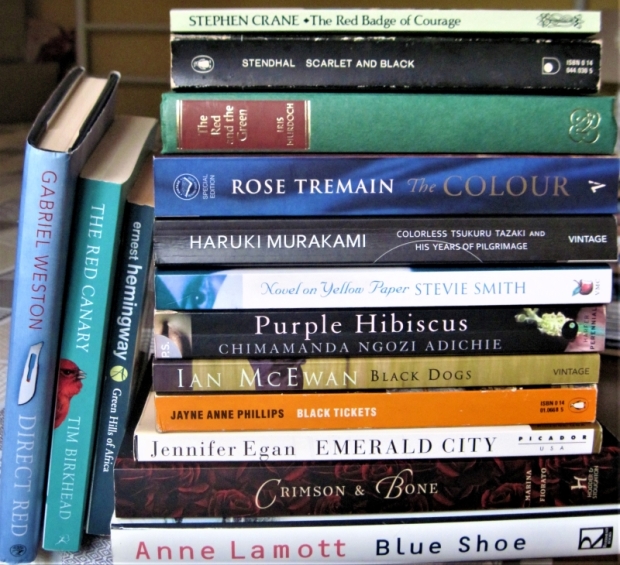

While there is a loose chronological through line, the book is principally arranged by theme, with experiences linked back to historical or literary precedents. An account of John Clare and the history of enclosure undergirds her feeling of the precarity of rural working-class life: as an Estate tenant, she knows she doesn’t own anything, has no real say in how things are done, and couldn’t afford to move elsewhere. Nicola is a school librarian and has always turned to books and writing to understand the world. I particularly loved Chapter 6, about how she grounds herself via the literature of this area: Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, Adam Thorpe’s Ulverton, and especially Richard Adams’s Watership Down.

Whatever life throws at her – her husband being called up to fight in Iraq, struggling to make ends meet with small children, a miscarriage, her father’s unexpected death – nature is her solace. She describes places and creatures with a rare intimacy borne out of deep knowledge. To research a book on otters for the RSPB, she seeks out every bridge over every stream. She goes out “lamping” with the local gamekeeper after dark and garners priceless nighttime sightings. Passing on her passion to her children, she gets them excited about badger watching, fossil collecting, and curating shelves of natural history treasures like skulls and feathers. She also serves as a voluntary wildlife advocate on her Estate. For every victory, like the re-establishment of the red kite population in Berkshire and regained public access to Greenham Common, there are multiple setbacks, but she continues to be a hopeful activist, her lyrical writing a means of defiance.

We are writing for our very lives and for those wild lives we share this one, lonely planet with. Writing was also a way to channel the wildness; to investigate and interpret it, to give it a voice and defend it. But it was also a connection between home and action; a plank bridge between a domestic and wild sense. A way both to home and resist.

You know that moment when you’re reading a book and spot a place you’ve been or a landmark you know well, and give a little cheer? Well, every site in this book was familiar to me from our daily lives and countryside wanderings – what a treat! As I was reading, I kept thinking how lucky we are to have such an accomplished nature writer to commemorate the uniqueness of this area. Even though I was born thousands of miles away and have moved more than a dozen times since I settled in England in 2007, I feel the same sense of belonging that Nicola attests to. She explicitly addresses this question of where we ‘come from’ versus where we fit in, and concludes that nature is always the key. There is no exclusion here. “Anyone could make a place their home by engaging with its nature.”

*I normally refer to the author by surname in a book review, but I’m friendly with Nicola from Twitter and have met her several times (and she’s one of the loveliest people you’ll ever meet), so somehow can’t bring myself to be that detached!

On Gallows Down was released by Chelsea Green Publishing on October 7th. My thanks to the author and publisher for arranging a proof copy for review.

My husband and I attended the book launch event for On Gallows Down in Hungerford on Saturday evening. Nicola was introduced by Hungerford Bookshop owner Emma Milne-White and interviewed by Claire Fuller, whose Women’s Prize-shortlisted novel Unsettled Ground is set in a fictional version of the village where Nicola lives.

Nicola Chester and Claire Fuller. Photo by Chris Foster.

Nicola dated the book’s genesis to the moment when, 25 years ago, she queued up to talk to a TV news reporter about Newbury Bypass and froze. She went home and cried, and realized she’d have to write her feelings down instead. Words generally come to her at the time of a sighting, as she thinks about how she would tell someone how amazing it was.

Her memories are tied up with seasons and language, especially poetry, she said, and she has recently tried her hand at poetry herself. Asked about her favourite season, she chose two, the in-between seasons – spring for its abundance and autumn for its nostalgia and distinctive smells like tar spot fungus on sycamore leaves and ivy flowers.

A bonus related read:

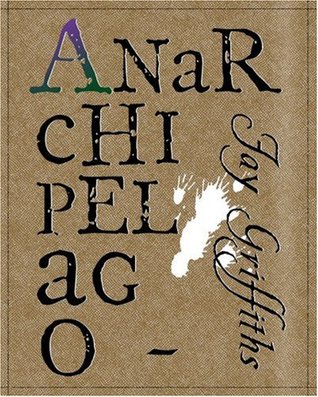

Anarchipelago by Jay Griffiths (2007)

This limited edition 57-page pamphlet from Glastonbury-based Wooden Books caught my eye from the library’s backroom rolling stacks. Griffiths wrote her impish story of Newbury Bypass resistance in response to her time among the protesters’ encampments and treehouses. Young Roddy finds a purpose for his rebellious attitude wider than his “McTypical McSuburb” by joining other oddballs in solidarity against aggressive policemen and detectives.

There are echoes of Ali Smith in the wordplay and rendering of accents.

“When I think of the road, I think of more and more monoculture of more and more suburbia. What I do, I do in defiance of the Louis Queasy Chintzy, the sickly stale air of suburban car culture. I want the fresh air of nature, the lifefull wind of the French revolution.”

In a nice spot of Book Serendipity, both this and On Gallows Down recount the moment when nature ‘fought back’ as a tree fell on a police cherry-picker. Plus Roddy is kin to the tree-sitting protesters in The Overstory by Richard Powers as well as another big novel I’m reading now, Damnation Spring by Ash Davidson.

20 Books of Summer, #16–17, GREEN: Jon Dunn and W.H. Hudson

Today’s entries in my colour-themed summer reading are a travelogue tracking the world’s endangered hummingbirds and a bizarre classic novel that blends nature writing and fantasy. Though very different books, they have in common lush South American forest settings.

The Glitter in the Green: In Search of Hummingbirds by Jon Dunn (2021)

As a wildlife writer and photographer, Jon Dunn has come to focus on small and secretive but indelible wonders. His previous book, which I still need to catch up on, was all about orchids, and in this new one he travels the length of the Americas, from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego, to see as many hummingbirds as he can. He provides a thorough survey of the history, science and cultural relevance (from a mini handgun to an indie pop band) of this most jewel-like of bird families. The ruby-throated hummingbirds I grew up seeing in suburban Maryland are gorgeous enough, but from there the names and corresponding colourful markings just get more magnificent: Glittering-throated Emeralds, Tourmaline Sunangels, Violet-capped woodnymphs, and so on. I’ll have to get a look at the photos in a finished copy of the book!

Dunn is equally good at describing birds and their habitats and at constructing a charming travelogue out of his sometimes fraught journeys. He has only a narrow weather of fog-free weather to get from Chile to Isla Robinson Crusoe and the plane has to turn back once before it successfully lands; a planned excursion in Bolivia is a non-starter after political protestors block some main routes. There are moments when the thrill of the chase is rewarded – as when he sees 24 hummingbird species in a day in Costa Rica – and many instances of lavish hospitality from locals who serve as guides or open their gardens to birdwatchers.

Dunn is equally good at describing birds and their habitats and at constructing a charming travelogue out of his sometimes fraught journeys. He has only a narrow weather of fog-free weather to get from Chile to Isla Robinson Crusoe and the plane has to turn back once before it successfully lands; a planned excursion in Bolivia is a non-starter after political protestors block some main routes. There are moments when the thrill of the chase is rewarded – as when he sees 24 hummingbird species in a day in Costa Rica – and many instances of lavish hospitality from locals who serve as guides or open their gardens to birdwatchers.

Like so many creatures, hummingbirds are in dire straits due to human activity: deforestation, invasive species, pesticide use and climate change are reducing the areas where they can live to pockets here and there; some species number in the hundreds and are considered critically endangered. Dunn juxtaposes the exploitative practices of (white, male) 19th- and 20th-century bird artists, collectors and hunters with indigenous birdwatching and environmental initiatives that are rising up to combat ecological damage in Latin America. Although society has moved past the use of hummingbird feathers in crafts and fashion, he learns that the troubling practice of dead hummingbirds being sold as love charms (chuparosas) persists in Mexico.

Whether you’re familiar with hummingbirds or not, if you have even a passing interest in nature and travel writing, I recommend The Glitter in the Green for how it invites readers into a personal passion, recreates an adventurous odyssey, and reinforces our collective responsibility for threatened wildlife. (Proof copy passed on by Paul of Halfman, Halfbook)

A lovely folk tale I’ll quote in full:

A hummingbird as a symbol of hope, strength and endurance is a recurrent one in South American folklore. An Ecuadorian folk tale tells of a forest on fire – a hummingbird picks up single droplets of water in its beak and lets them fall on the fire. The other animals in the forest laugh, and ask the hummingbird what difference this can possibly make. They say, ‘Don’t bother, it is too much, you are too little, your wings will burn, your beak is too tiny, it’s only a drop, you can’t put out this fire. What do you think you are doing?’ To which the hummingbird is said to reply, ‘I’m just doing what I can.’

Links between the books: Hudson is quoted in Dunn’s introduction. In Chapter 7 of the below, Hudson describes a hummingbird as “a living prismatic gem that changes its colour with every change of position … it catches the sunshine on its burnished neck and gorget plumes—green and gold and flame-coloured, the beams changing to visible flakes as they fall”

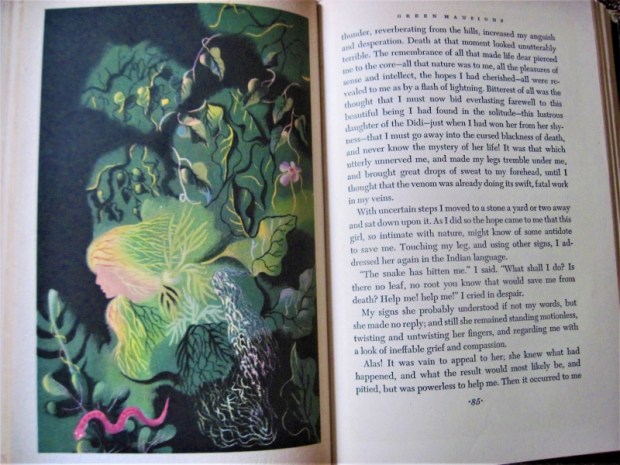

Green Mansions: A Romance of the Tropical Forest by W.H. Hudson (1904)

Like Heart of Darkness, this is a long recounted tale about a journey among ‘savages’. After a prologue, the narrator soon cedes storytelling duties to Mr. Abel, whom he met in Georgetown, Guyana in 1887. Searching for gold and fighting off illness, the 23-year-old Abel took up the habit of wandering the Venezuelan forest. The indigenous people were superstitious and refused to hunt in that forest. Abel began to hear strange noises – magical bird calls or laughter – that, siren-like, drew him deeper in. His native friend warned him it was the daughter of an evil spirit.

Like Heart of Darkness, this is a long recounted tale about a journey among ‘savages’. After a prologue, the narrator soon cedes storytelling duties to Mr. Abel, whom he met in Georgetown, Guyana in 1887. Searching for gold and fighting off illness, the 23-year-old Abel took up the habit of wandering the Venezuelan forest. The indigenous people were superstitious and refused to hunt in that forest. Abel began to hear strange noises – magical bird calls or laughter – that, siren-like, drew him deeper in. His native friend warned him it was the daughter of an evil spirit.

One day, after being bitten by a snake, Abel woke up in the dwelling of an old man and his 17-year-old granddaughter, Rima – the very wood sprite he’d sensed all these times in the forest; she saved his life. Recovering in their home and helping Rima investigate her origins, he romanticizes this tree spirit in a way that struck me as smarmy. It’s possible this could be appreciated as a fable of connection with nature, but I found it vague and old-fashioned. (Not to mention Abel’s condescending attitude to the indigenous people and to women.) I ended up skimming the last three-quarters.

My husband has read nonfiction by Hudson; I think I was under the impression that this was a memoir, in fact. Perhaps I’d enjoy Hudson’s writing in another genre. But I was surprised to read high praise from John Galsworthy in the foreword (“For of all living authors—now that Tolstoi has gone—I could least dispense with W. H. Hudson”) and to note how many of my Goodreads friends have read this; I don’t see it as a classic that stands the test of time.

My 1944 hardback once belonged to one Mary Marcilliat of Louisville, Kentucky, and has strange abstract illustrations by E. McKnight Kauffer. (Free from the Book Thing of Baltimore)

Coming up next: One black and one gold on Wednesday; a Green author and a rainbow bonus (probably on the very last day).

Would you be interested in reading one of these?

Review Book Catch-Up: Motherhood, Nature Essays, Pandemic, Poetry

July slipped away without me managing to review any current-month releases, as I am wont to do, so to those three I’m adding in a couple of other belated review books to make up today’s roundup. I have: a memoir-cum-sociological study of motherhood, poems of Afghan women’s experiences, a graphic novel about a fictional worst-case pandemic, seasonal nature essays from voices not often heard, and poetry about homosexual encounters.

(M)otherhood: On the choices of being a woman by Pragya Agarwal

“Mothering would be my biggest gesture of defiance.”

Growing up in India, Agarwal, now a behavioural and data scientist, wished she could be a boy for her father’s sake. Being the third daughter was no place of honour in society’s eyes, but her parents ensured that she got a good education and expected her to achieve great things. Still, when she got her first period, it felt like being forced onto a fertility track she didn’t want. There was a dearth of helpful sex education, and Hinduism has prohibitions that appear to diminish women, e.g. menstruating females aren’t permitted to enter a temple.

Growing up in India, Agarwal, now a behavioural and data scientist, wished she could be a boy for her father’s sake. Being the third daughter was no place of honour in society’s eyes, but her parents ensured that she got a good education and expected her to achieve great things. Still, when she got her first period, it felt like being forced onto a fertility track she didn’t want. There was a dearth of helpful sex education, and Hinduism has prohibitions that appear to diminish women, e.g. menstruating females aren’t permitted to enter a temple.

Married and unexpectedly pregnant in 1996, Agarwal determined to raise her daughter differently. Her mother-in-law was deeply disappointed that the baby was a girl, which only increased her stubborn pride: “Giving birth to my daughter felt like first love, my only love. Not planned but wanted all along. … Me and her against the world.” No element of becoming a mother or of her later life lived up to her expectations, but each apparent failure gave a chance to explore the spectrum of women’s experiences: C-section birth, abortion, divorce, emigration, infertility treatment, and finally having further children via a surrogate.

While I enjoyed the surprising sweep of Agarwal’s life story, this is no straightforward memoir. It aims to be an exhaustive survey of women’s life choices and the cultural forces that guide or constrain them. The book is dense with history and statistics, veers between topics, and needed a better edit for vernacular English and smoothing out academic jargon. I also found that I wasn’t interested enough in the specifics of women’s lives in India.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

Forty Names by Parwana Fayyaz

“History has ungraciously failed the women of my family”

Have a look at this debut poet’s journey: Fayyaz was born in Kabul in 1990, grew up in Afghanistan and Pakistan, studied in Bangladesh and at Stanford, and is now, having completed her PhD, a research fellow at Cambridge. Many of her poems tell family stories that have taken on the air of legend due to the translated nicknames: “Patience Flower,” her grandmother, was seduced by the Khan and bore him two children; “Quietude,” her aunt, was a refugee in Iran. Her cousin, “Perfect Woman,” was due to be sent away from the family for infertility but gained revenge and independence in her own way.

Have a look at this debut poet’s journey: Fayyaz was born in Kabul in 1990, grew up in Afghanistan and Pakistan, studied in Bangladesh and at Stanford, and is now, having completed her PhD, a research fellow at Cambridge. Many of her poems tell family stories that have taken on the air of legend due to the translated nicknames: “Patience Flower,” her grandmother, was seduced by the Khan and bore him two children; “Quietude,” her aunt, was a refugee in Iran. Her cousin, “Perfect Woman,” was due to be sent away from the family for infertility but gained revenge and independence in her own way.

Fayyaz is bold to speak out about the injustices women can suffer in Afghan culture. Domestic violence is rife; miscarriage is considered a disgrace. In “Roqeeya,” she remembers that her mother, even when busy managing a household, always took time for herself and encouraged Parwana, her eldest, to pursue an education and earn her own income. However, the poet also honours the wisdom and skills that her illiterate mother exhibited, as in the first three poems about the care she took over making dresses and dolls for her three daughters.

As in Agarwal’s book, there is a lot here about ideals of femininity and the different routes that women take – whether more or less conventional. “Reading Nadia with Eavan” was a favourite for how it brought together different aspects of Fayyaz’s experience. Nadia Anjuman, an Afghan poet, was killed by her husband in 2005; many years later, Fayyaz found herself studying Anjuman’s work at Cambridge with the late Eavan Boland. Important as its themes are, I thought the book slightly repetitive and unsubtle, and noted few lines or turns of phrase – always a must for me when assessing a poetry collection.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

Resistance by Val McDermid; illus. Kathryn Briggs

The second 2021 release I read in quick succession in which all but a small percentage of the human race (here, 2 million people) perishes in a pandemic – the other was Under the Blue. Like Aristide’s novel, this story had its origins in 2017 (in this case, on BBC Radio 4’s “Dangerous Visions”) but has, of course, taken on newfound significance in the time of Covid-19. McDermid imagines the sickness taking hold during a fictional version of Glastonbury: Solstice Festival in Northumberland. All the first patients, including a handful of rockstars, ate from Sam’s sausage sandwich van, so initially it looks like food poisoning. But vomiting and diarrhoea give way to a nasty rash, listlessness and, in many cases, death.

The second 2021 release I read in quick succession in which all but a small percentage of the human race (here, 2 million people) perishes in a pandemic – the other was Under the Blue. Like Aristide’s novel, this story had its origins in 2017 (in this case, on BBC Radio 4’s “Dangerous Visions”) but has, of course, taken on newfound significance in the time of Covid-19. McDermid imagines the sickness taking hold during a fictional version of Glastonbury: Solstice Festival in Northumberland. All the first patients, including a handful of rockstars, ate from Sam’s sausage sandwich van, so initially it looks like food poisoning. But vomiting and diarrhoea give way to a nasty rash, listlessness and, in many cases, death.

Zoe Beck, a Black freelance journalist who conducted interviews at Solstice, is friends with Sam and starts investigating the mutated swine disease, caused by an Erysipelas bacterium and thus nicknamed “the Sips.” She talks to the festival doctor and to a female Muslim researcher from the Life Sciences Centre in Newcastle, but her search for answers takes a backseat to survival when her husband and sons fall ill.

The drawing style and image quality – some panes are blurry, as if badly photocopied – let an otherwise reasonably gripping story down; the best spreads are collages or borrow a frame/backdrop (e.g. a medieval manuscript, NHS forms, or a 1910s title page).

SPOILER

{The ending, which has an immune remnant founding a new community, is VERY Parable of the Sower.}

With thanks to Profile Books/Wellcome Collection for the free copy for review.

Gifts of Gravity and Light: A Nature Almanac for the 21st Century, ed. Anita Roy and Pippa Marland

I hadn’t heard about this upcoming nature anthology when a surprise copy dropped through my letterbox. I’m delighted the publisher thought of me, as this ended up being just my sort of book: 12 autobiographical essays infused with musings on landscapes in Britain and elsewhere; structured by the seasons to create a gentle progression through the year, starting with the spring. Best of all, the contributors are mostly female, BIPOC (and Romany), working class and/or queer – all told, the sort of voices that are heard far too infrequently in UK nature writing. In momentous rites of passage, as in routine days, nature plays a big role.

A few of my favourite pieces were by Kaliane Bradley, about her Cambodian heritage (the Wishing Dance associated with cherry blossom, her ancestors lost to genocide, the Buddhist belief that people can be reincarnated in other species); Testament, a rapper based in Leeds, about capturing moments through photography and poetry and about the seasons feeling awry both now and in March 2008, when snow was swirling outside the bus window as he received word of his uni friend’s untimely death; and Tishani Doshi, comparing childhood summers of freedom in Wales with growing up in India and 2020’s Covid restrictions.

A few of my favourite pieces were by Kaliane Bradley, about her Cambodian heritage (the Wishing Dance associated with cherry blossom, her ancestors lost to genocide, the Buddhist belief that people can be reincarnated in other species); Testament, a rapper based in Leeds, about capturing moments through photography and poetry and about the seasons feeling awry both now and in March 2008, when snow was swirling outside the bus window as he received word of his uni friend’s untimely death; and Tishani Doshi, comparing childhood summers of freedom in Wales with growing up in India and 2020’s Covid restrictions.

Most of the authors hold two places in mind at the same time: for Michael Malay, it’s Indonesia, where he grew up, and the Severn estuary, where he now lives and ponders eels’ journeys; for Zakiya McKenzie, it’s Jamaica and England; for editor Anita Roy, it’s Delhi versus the Somerset field her friend let her wander during lockdown. Trees lend an awareness of time and animals a sense of movement and individuality. Alys Fowler thinks of how the wood she secretly coppices and lays on park paths to combat the mud will long outlive her, disintegrating until it forms the very soil under future generations’ feet.

A favourite passage (from Bradley): “When nature is the cuddly bunny and the friendly old hill, it becomes too easy to dismiss it as a faithful retainer who will never retire. But nature is the panic at the end of a talon, and it’s the tree with a heart of fire where lightning has struck. It is not our friend, and we do not want to make it our enemy.”

Also featured: Bernardine Evaristo (foreword), Raine Geoghegan, Jay Griffiths, Amanda Thomson, and Luke Turner.

With thanks to Hodder & Stoughton for the free copy for review.

Records of an Incitement to Silence by Gregory Woods

Woods is an emeritus professor at Nottingham Trent University, where he was appointed the UK’s first professor of Gay & Lesbian Studies in 1998. Much of his sixth poetry collection is composed of unrhymed sonnets in two stanzas (eight lines, then six). The narrator is often a randy flâneur, wandering a city for homosexual encounters. One assumes this is Woods, except where the voice is identified otherwise, as in “[Walt] Whitman at Timber Creek” (“He gives me leave to roam / my idle way across / his prairies, peaks and canyons, my own America”) and “No Title Yet,” a long, ribald verse about a visitor to a stately home.

Woods is an emeritus professor at Nottingham Trent University, where he was appointed the UK’s first professor of Gay & Lesbian Studies in 1998. Much of his sixth poetry collection is composed of unrhymed sonnets in two stanzas (eight lines, then six). The narrator is often a randy flâneur, wandering a city for homosexual encounters. One assumes this is Woods, except where the voice is identified otherwise, as in “[Walt] Whitman at Timber Creek” (“He gives me leave to roam / my idle way across / his prairies, peaks and canyons, my own America”) and “No Title Yet,” a long, ribald verse about a visitor to a stately home.

Other times the perspective is omniscient, painting a character study, like “Company” (“When he goes home to bed / he dare not go alone. … This need / of company defeats him.”), or of Frank O’Hara in “Up” (“‘What’s up?’ Frank answers with / his most unseemly grin, / ‘The sun, the Dow, my dick,’ / and saunters back to bed.”). Formalists are sure to enjoy Woods’ use of form, rhyme and meter. I enjoyed some of the book’s cheeky moments but had trouble connecting with its overall tone and content. That meant that it felt endless. I also found the end rhymes, when they did appear, over-the-top and silly (Demeter/teeter, etc.).

Two favourite poems: “An Immigrant” (“He turned away / to strip. His anecdotes / were innocent and his / erection smelled of soap.”) and “A Knot,” written for friends’ wedding in 2014 (“make this wedding supper all the sweeter / With choirs of LGBT cherubim”).

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

Would you be interested in reading one or more of these?

Recommended May Releases: Adichie, Pavey and Unsworth

Three very different works of women’s life writing: heartfelt remarks on bereavement, a seasonal diary of stewarding four wooded acres in Somerset, and a look back at postnatal depression.

Notes on Grief by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

This slim hardback is an expanded version of an essay Adichie published in the New Yorker in the wake of her father’s death in June 2020. With her large family split across three continents and coronavirus lockdown precluding in-person get-togethers, they had a habit of frequent video calls. She had seen her father the day before on Zoom and knew he was feeling unwell and in need of rest, but the news of his death still came as a complete shock.

Adichie anticipates all the unhelpful platitudes people could and did send her way: he lived to a ripe old age (he was 88), he had a full life and was well respected (he was Nigeria’s first statistics professor), he had a mercifully swift end (kidney failure). Her logical mind knows all of these facts, and her writer’s imagination has depicted grief many times. Still, this loss blindsided her.

Adichie anticipates all the unhelpful platitudes people could and did send her way: he lived to a ripe old age (he was 88), he had a full life and was well respected (he was Nigeria’s first statistics professor), he had a mercifully swift end (kidney failure). Her logical mind knows all of these facts, and her writer’s imagination has depicted grief many times. Still, this loss blindsided her.

She’d always been a daddy’s girl, but the anecdotes she tells confirm how special he was: wise and unassuming; a liberal Catholic suspicious of materialism and with a dry humour. I marvelled at one such story: in 2015 he was kidnapped and held in the boot of a car for three days, his captors demanding a ransom from his famous daughter. What did he do? Correct their pronunciation of her name, and contradict them when they said that clearly his children didn’t love him. “Grief has, as one of its many egregious components, the onset of doubt. No, I am not imagining it. Yes, my father truly was lovely.” With her love of fashion, one way she dealt with her grief was by designing T-shirts with her father’s initials and the Igbo words for “her father’s daughter” on them.

I’ve read many a full-length bereavement memoir, and one might think there’s nothing new to say, but Adichie writes with a novelist’s eye for telling details and individual personalities. She has rapidly become one of my favourite authors: I binged on most of her oeuvre last year and now have just one more to read, Purple Hibiscus, which will be one of my 20 Books of Summer. I love her richly evocative prose and compassionate outlook, no matter the subject. At £10, this 85-pager is pricey, but I was lucky to get it free with Waterstones loyalty points.

Favourite lines:

“In the face of this inferno that is sorrow, I am callow and unformed.”

“How is it that the world keeps going, breathing in and out unchanged, while in my soul there is a permanent scattering?”

Deeper Into the Wood by Ruth Pavey

In 1999 Ruth Pavey bought four acres of scrubland at auction, happy to be returning to her family’s roots in the Somerset Levels and hoping to work alongside nature to restore some of her land to orchard and maintain the rest in good health. Her account of the first two decades of this ongoing project, A Wood of One’s Own, was published in 2017.

In 1999 Ruth Pavey bought four acres of scrubland at auction, happy to be returning to her family’s roots in the Somerset Levels and hoping to work alongside nature to restore some of her land to orchard and maintain the rest in good health. Her account of the first two decades of this ongoing project, A Wood of One’s Own, was published in 2017.

In this sequel, she gives peaceful snapshots of the wood throughout 2019, from first snowdrops to final apple pressing, but also faces up to the environmental degradation that is visible even in this pocket of the countryside. “I am sure there has been a falling off in numbers of insects, smaller birds and rabbits on my patch,” she insists. Without baseline data, it is hard to support this intuition, but she has botanical and bird surveys done, and invites an expert in to do a moth-trapping evening. The resulting species lists are included as appendices. In addition, Pavey weaves a backstory for her land. She meets a daffodil breeder, investigates the source of her groundwater, and visits the head gardener at the Bishop’s Palace in Wells, where her American black walnut sapling came from. She also researches the Sugg family, associated with the land (“Sugg’s Orchard” on the deed) from the 1720s.

Pavey aims to treat this landscape holistically: using sheep to retain open areas instead of mowing the grass, and weighing up the benefits of the non-native species she has planted. She knows her efforts can only achieve so much; the pesticides standard to industrial-scale farming may still be reaching her trees on the wind, though she doesn’t apply them herself. “One sad aspect of worrying about the state of the natural world is that everything starts to look wrong,” she admits. Starting in that year’s abnormally warm January, it was easy for her to assume that the seasons can no longer be relied on.

Pavey aims to treat this landscape holistically: using sheep to retain open areas instead of mowing the grass, and weighing up the benefits of the non-native species she has planted. She knows her efforts can only achieve so much; the pesticides standard to industrial-scale farming may still be reaching her trees on the wind, though she doesn’t apply them herself. “One sad aspect of worrying about the state of the natural world is that everything starts to look wrong,” she admits. Starting in that year’s abnormally warm January, it was easy for her to assume that the seasons can no longer be relied on.

Compared with her first memoir, this one is marked by its intellectual engagement with the principles and practicalities of rewilding. Clearly, her inner struggle is motivated less by the sense of ownership than by the call of stewardship. While this book is likely be of most interest to those with a local connection or a similar project underway, it offers a universal model of how to mitigate our environmental impact. Pavey’s black-and-white sketches of the flora and fauna on her patch, reminiscent of Quentin Blake, are a highlight.

With thanks to Duckworth for the proof copy for review. The book will be published tomorrow, the 27th of May.

After the Storm: Postnatal Depression and the Utter Weirdness of New Motherhood by Emma Jane Unsworth

The author’s son was born on the day Donald Trump won the U.S. presidential election. Six months later, she realized that she was deep into postnatal depression and finally agreed to get help. The breaking point came when, with her husband* away at a conference, she got frustrated with her son’s constant fussing and pushed him over on the bed. He was absolutely fine, but the guilty what-ifs proliferated, making this a wake-up call for her.

In this succinct, wry and hard-hitting memoir, Unsworth exposes the conspiracies of silence that lead new mothers to lie and pretend that everything is fine. Since her son’s traumatic birth (which I first read about in Dodo Ink’s Trauma anthology), she hadn’t been able to write and was losing her sense of self. To add insult to injury, her baby had teeth at 16 weeks and bit her as he breastfed. She couldn’t even admit her struggles to her fellow mum friends. But “if a woman is in pain for long enough, and denied sleep for long enough, and at the same time feels as though she has to keep going and put a ‘brave’ face on, she’s going to crack.”

In this succinct, wry and hard-hitting memoir, Unsworth exposes the conspiracies of silence that lead new mothers to lie and pretend that everything is fine. Since her son’s traumatic birth (which I first read about in Dodo Ink’s Trauma anthology), she hadn’t been able to write and was losing her sense of self. To add insult to injury, her baby had teeth at 16 weeks and bit her as he breastfed. She couldn’t even admit her struggles to her fellow mum friends. But “if a woman is in pain for long enough, and denied sleep for long enough, and at the same time feels as though she has to keep going and put a ‘brave’ face on, she’s going to crack.”

The book’s titled mini-essays give snapshots into the before and after, but particularly the agonizing middle of things. I especially liked the chapter “The Weirdest Thing I’ve Ever Done in a Hotel Room,” in which she writes about borrowing her American editor’s room to pump breastmilk. Therapy, antidepressants and hiring a baby nurse helped her to ease back into her old life and regain some part of the party girl persona she once exuded – enough so that she was willing to give it all another go (her daughter was born late last year).

While Unsworth mostly writes from experience, she also incorporates recent research and makes bold statements of how cultural norms need to change. “You are not monsters,” she writes to depressed mums. “You need more support. … Motherhood is seismic. It cracks open your life, your relationship, your identity, your body. It features the loss, grief and hardship of any big life change.” I can imagine this being hugely helpful to anyone going through PND (see also my Three on a Theme post on the topic), but I’m not a mother and still found plenty to appreciate (especially “We have to smash the dichotomy of mums/non-mums … being maternal has nothing to do with actually physically being a mother”).

I’m attending a Wellcome Collection online event with Unsworth and midwife Leah Hazard (author of Hard Pushed) this evening and look forward to hearing more from both authors.

*It took me no time at all to identify him from the bare facts: Brighton + doctor + graphic novelist = Ian Williams (author of The Lady Doctor)! I had no idea. What a fun connection.

With thanks to Profile Books/Wellcome Collection for the free copy for review.

What recent releases can you recommend?

Rooted by Lyanda Lynn Haupt

Lyanda Lynn Haupt’s Crow Planet was the highlight of my 2019 animal-themed summer reading. I admired her determination to incorporate wildlife-watching into everyday life, and appreciated her words on the human connection to and responsibility towards the rest of nature. Rooted, one of my most anticipated books of this year, continues in that vein, yet surprised me with its mystical approach. No doubt some will be put off by the spiritual standpoint and dismiss the author as a barefoot, tree-hugging hippie. Well, sign me up to Haupt’s team, because nature needs all the help it can get, and we know that people won’t save what they don’t love. Start to think about trees and animals as brothers and sisters – or even as part of the self – and actions that passively doom them, not to mention wanton destruction of habitat, will hit closer to home.

I hadn’t realized that Haupt grew up Catholic, so the language of mysticism comes easily to her, but even as a child nature was where she truly sensed transcendence. Down by the creek, where she listened to birdsong and watched the frog lifecycle, was where she learned that everything is connected. She even confessed her other church, “Frog Church” (this book’s original title), to her priest one day. (He humored her by assigning an extra Our Father.) How to reclaim that childhood feeling of connectedness as a busy, tech-addicted adult?

I hadn’t realized that Haupt grew up Catholic, so the language of mysticism comes easily to her, but even as a child nature was where she truly sensed transcendence. Down by the creek, where she listened to birdsong and watched the frog lifecycle, was where she learned that everything is connected. She even confessed her other church, “Frog Church” (this book’s original title), to her priest one day. (He humored her by assigning an extra Our Father.) How to reclaim that childhood feeling of connectedness as a busy, tech-addicted adult?

The Seattle-based Haupt engages in, and encourages, solo camping, barefoot walking, purposeful wandering, spending time sitting under trees, mindfulness, and going out in the dark. This might look countercultural, or even eccentric. Some will also feel called to teach, to protest, and to support environmental causes financially. Others will contribute their talent for music, writing, or the visual arts. But there are subtler changes to be made too, in our attitudes and the way we speak. A simple one is to watch how we refer to other species. “It” has no place in a creature-directed vocabulary.

Haupt’s perspective chimes with the ethos of the New Networks for Nature conference I attend each year, as well as with the work of many UK nature writers like Robert Macfarlane (in particular, she mentions The Lost Words) and Jini Reddy (Wanderland). I also found a fair amount of overlap with Lucy Jones’s Losing Eden. There were points where Haupt got a little abstract and even woo-woo for me – and I say that as someone with a religious background. But her passion won me over, and her book helped me to understand why two things that happened earlier this year – a fox dying in our backyard and neighbors having a big willow tree taken down – wounded me so deeply. That I felt each death throe and chainsaw cut as if in my own body wasn’t just me being sentimental and oversensitive. It was a reminder that I’m a part of all of life, and I must do more to protect it.

Favorite lines:

“In this time of planetary crisis, overwhelm is common. What to do? There is so much. Too much. No single human can work to save the orcas and the Amazon and organize protests to stop fracking and write poetry that inspires others to act and pray in a hermit’s dwelling for transformation and get dinner on the table. How easy it is to feel paralyzed by obligations. How easy it is to feel lost and insignificant and unable to know what is best, to feel adrift while yearning for purpose. Rootedness is a way of being in concert with the wilderness—and wildness—that sustains humans and all of life.”

“No one can do all things. Yet we can hold all things as we trim and change our lives and choose our particular forms of rooted, creative action—those that call uniquely to us.”

With thanks to Little, Brown Spark for sending a proof copy all the way from Boston, USA.

Young Writer of the Year Award 2020: Shortlist Reviews and Predictions

Being on the shadow panel for the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award was a bookish highlight of 2017 for me. I’m pleased for this year’s panelists, especially blogging friend Marina Sofia, to have had the same opportunity, and I look forward to hearing who they choose as their shadow panel winner on December 3rd and then attending the virtual prize ceremony on December 10th.

At the time of the shortlisting, I happened to have already read Exciting Times by Naoise Dolan and was halfway through Catherine Cho’s memoir Inferno. I got the poetry collection Surge by Jay Bernard out from the library to have another go (after DNFing it last year), and the kind folk of FMcM Associates sent me the other two shortlisted books, a poetry collection and a novel, so that I could follow along with the shadow panel’s deliberations. Here are my brief thoughts on all five nominees.

Surge by Jay Bernard (2019)

As a writer-in-residence at the George Padmore Institute, a research centre for radical Black history, in 2016, Bernard investigated the New Cross Massacre, a fire that killed 13 young people in 1981. In 2017, the tragedy found a horrific echo in the Grenfell Tower fire, which left 72 dead. This debut poetry collection bridges that quarter-century through protest poems from various perspectives, giving voice to victims and their family members and exploring the interplay between race, sexuality and violence. Patois comes in at several points, most notably in “Songbook.” I especially liked “Peg” and “Pride,” and the indictment of government indifference in “Blank”: “It-has-nothing-to-do-with-us today issued this statement: / those involved have defended their actions and been … acquitted / retired with full pay”. On the whole, I found it difficult to fully engage with this collection, but I am reliably informed that Bernard’s protest poems have more impact when performed aloud.

As a writer-in-residence at the George Padmore Institute, a research centre for radical Black history, in 2016, Bernard investigated the New Cross Massacre, a fire that killed 13 young people in 1981. In 2017, the tragedy found a horrific echo in the Grenfell Tower fire, which left 72 dead. This debut poetry collection bridges that quarter-century through protest poems from various perspectives, giving voice to victims and their family members and exploring the interplay between race, sexuality and violence. Patois comes in at several points, most notably in “Songbook.” I especially liked “Peg” and “Pride,” and the indictment of government indifference in “Blank”: “It-has-nothing-to-do-with-us today issued this statement: / those involved have defended their actions and been … acquitted / retired with full pay”. On the whole, I found it difficult to fully engage with this collection, but I am reliably informed that Bernard’s protest poems have more impact when performed aloud.

Readalikes: In Nearby Bushes by Kei Miller, A Portable Paradise by Roger Robinson and Don’t Call Us Dead by Danez Smith

My rating:

Inferno by Catherine Cho (2020)

Cho, a Korean American literary agent based in London, experienced stress-induced postpartum psychosis after the birth of her son. She and her husband had returned to the USA when Cato was two months old to introduce him to friends and family, ending with a big Korean 100-day celebration at her in-laws’ home. Almost as soon as they got to her in-laws’, though, she started acting strangely: she was convinced cameras were watching their every move, and Cato’s eyes were replaced with “devil’s eyes.” She insisted they leave for a hotel, but soon she would be in a hospital emergency room, followed by a mental health ward. Cho alternates between her time in the mental hospital and a rundown of the rest of her life before the breakdown, weaving in her family history and Korean sayings and legends. Twelve days: That was the length of her hospitalization in early 2018, but Cho so painstakingly depicts her mindset that readers are fully immersed in an open-ended purgatory. She captures extremes of suffering and joy in this vivid account. (Reviewed in full here.)

Cho, a Korean American literary agent based in London, experienced stress-induced postpartum psychosis after the birth of her son. She and her husband had returned to the USA when Cato was two months old to introduce him to friends and family, ending with a big Korean 100-day celebration at her in-laws’ home. Almost as soon as they got to her in-laws’, though, she started acting strangely: she was convinced cameras were watching their every move, and Cato’s eyes were replaced with “devil’s eyes.” She insisted they leave for a hotel, but soon she would be in a hospital emergency room, followed by a mental health ward. Cho alternates between her time in the mental hospital and a rundown of the rest of her life before the breakdown, weaving in her family history and Korean sayings and legends. Twelve days: That was the length of her hospitalization in early 2018, but Cho so painstakingly depicts her mindset that readers are fully immersed in an open-ended purgatory. She captures extremes of suffering and joy in this vivid account. (Reviewed in full here.)

Readalikes: An Angel at My Table by Janet Frame and Dear Scarlet by Teresa Wong

My rating:

Exciting Times by Naoise Dolan (2020)

At 22, Ava leaves Dublin to teach English as a foreign language to wealthy preteens in Hong Kong and soon comes to a convenient arrangement with her aloof banker friend, Julian, who lets her live with him without paying rent and buys her whatever she wants. They have sex, yes, but he’s not her boyfriend per se, so when he’s transferred to London for six months, there’s no worry about hard feelings when her new friendship with Edith Zhang turns romantic. It gets a little more complicated, though, when Julian returns and she has to explain these relationships to her two partners and to herself. On the face of it, this doesn’t sound like it would be an interesting plot, and the hook-up culture couldn’t be more foreign to me. But with Ava Dolan has created a funny, deadpan voice that carries the entire novel. I loved the psychological insight, the playfulness with language, and the zingy one-liners (“I wondered if Victoria was a real person or three Mitford sisters in a long coat”). (Reviewed in full here.)

At 22, Ava leaves Dublin to teach English as a foreign language to wealthy preteens in Hong Kong and soon comes to a convenient arrangement with her aloof banker friend, Julian, who lets her live with him without paying rent and buys her whatever she wants. They have sex, yes, but he’s not her boyfriend per se, so when he’s transferred to London for six months, there’s no worry about hard feelings when her new friendship with Edith Zhang turns romantic. It gets a little more complicated, though, when Julian returns and she has to explain these relationships to her two partners and to herself. On the face of it, this doesn’t sound like it would be an interesting plot, and the hook-up culture couldn’t be more foreign to me. But with Ava Dolan has created a funny, deadpan voice that carries the entire novel. I loved the psychological insight, the playfulness with language, and the zingy one-liners (“I wondered if Victoria was a real person or three Mitford sisters in a long coat”). (Reviewed in full here.)

Readalikes: Besotted by Melissa Duclos and Conversations with Friends by Sally Rooney

My rating:

Tongues of Fire by Seán Hewitt (2020)

In the title poem, the arboreal fungus from the cover serves as “a bright, ancestral messenger // bursting through from one realm to another” like “the cones of God, the Pentecostal flame”. This debut collection is alive with striking imagery that draws links between the natural and the supernatural. Sex and grief, two major themes, are silhouetted against the backdrop of nature. Fields and forests are loci of meditation and epiphany, but also of clandestine encounters between men: “I came back often, // year on year, kneeling and being knelt for / in acts of secret worship, and now / each woodland smells quietly of sex”. Hewitt recalls travels to Berlin and Sweden, and charts his father’s rapid decline and death from an advanced cancer. A central section of translations of the middle-Irish legend “Buile Suibhne” is less memorable than the gorgeous portraits of flora and fauna and the moving words dedicated to the poet’s father: “You are not leaving, I know, // but shifting into image – my head / already is haunted with you” and “In this world, I believe, / there is nothing lost, only translated”.

In the title poem, the arboreal fungus from the cover serves as “a bright, ancestral messenger // bursting through from one realm to another” like “the cones of God, the Pentecostal flame”. This debut collection is alive with striking imagery that draws links between the natural and the supernatural. Sex and grief, two major themes, are silhouetted against the backdrop of nature. Fields and forests are loci of meditation and epiphany, but also of clandestine encounters between men: “I came back often, // year on year, kneeling and being knelt for / in acts of secret worship, and now / each woodland smells quietly of sex”. Hewitt recalls travels to Berlin and Sweden, and charts his father’s rapid decline and death from an advanced cancer. A central section of translations of the middle-Irish legend “Buile Suibhne” is less memorable than the gorgeous portraits of flora and fauna and the moving words dedicated to the poet’s father: “You are not leaving, I know, // but shifting into image – my head / already is haunted with you” and “In this world, I believe, / there is nothing lost, only translated”.

Readalikes: Physical by Andrew McMillan and If All the World and Love Were Young by Stephen Sexton

My rating:

Nightingale by Marina Kemp (2020)

Marguerite Demers, a 24-year-old nurse, has escaped Paris to be a live-in carer for elderly Jérôme Lanvier in southern France. From the start, she senses she’s out of place here – “She felt, as always in this village, that she was being observed”. She strikes up a friendship with a fellow outsider, an Iranian émigrée named Suki, who, in this story set in 2002, stands out for wearing a hijab. Everyone knows everyone here, and everyone has history with everyone else – flirtations, feuds, affairs, and more. Brigitte Brochon, unhappily married to a local farmer, predicts Marguerite will be just like the previous nurses who failed to hack it in service to the curmudgeonly Monsieur Lanvier. But Marguerite sticks up for herself and, though plagued by traumatic memories, makes her own bid for happiness. The novel deals sensitively with topics like bisexuality, euthanasia, and family estrangement, but the French provincial setting and fairly melodramatic plot struck me as old-fashioned. Still, the writing is strong enough to keep an eye out for what Kemp writes next. (U.S. title: Marguerite.)

Marguerite Demers, a 24-year-old nurse, has escaped Paris to be a live-in carer for elderly Jérôme Lanvier in southern France. From the start, she senses she’s out of place here – “She felt, as always in this village, that she was being observed”. She strikes up a friendship with a fellow outsider, an Iranian émigrée named Suki, who, in this story set in 2002, stands out for wearing a hijab. Everyone knows everyone here, and everyone has history with everyone else – flirtations, feuds, affairs, and more. Brigitte Brochon, unhappily married to a local farmer, predicts Marguerite will be just like the previous nurses who failed to hack it in service to the curmudgeonly Monsieur Lanvier. But Marguerite sticks up for herself and, though plagued by traumatic memories, makes her own bid for happiness. The novel deals sensitively with topics like bisexuality, euthanasia, and family estrangement, but the French provincial setting and fairly melodramatic plot struck me as old-fashioned. Still, the writing is strong enough to keep an eye out for what Kemp writes next. (U.S. title: Marguerite.)

Readalikes: French-set novels by Joanne Harris and Rose Tremain; The Hoarder by Jess Kidd

My rating:

General thoughts:

After last year’s unexpected winner – Raymond Antrobus for his poetry collection The Perseverance – I would have said that it’s time for a novel by a woman to win. However, I feel like a Dolan win would be too much of a repeat of 2017’s win (for Sally Rooney), and Kemp’s debut novel isn’t quite up to scratch. Much as I enjoyed Inferno, I can’t see it winning over these judges (three of whom are novelists: Kit de Waal, Sebastian Faulks and Tessa Hadley), though it would be suited to the Wellcome Book Prize if that comes back in 2021. So, to my surprise, I think it’s going to be another year for poetry.

I’ve been following the shadow panel’s thoughts via Marina’s blog and the others’ Instagram accounts and it looks like they are united in their admiration for the poetry collections, particularly the Hewitt. That would be my preference, too: I respond better to theme and style in poetry (Hewitt) than to voice and message (Bernard). However, I think that in 2020 the Times may try to trade its rather fusty image for something more woke, bearing in mind the Black Lives Matter significance and the unprecedented presence of a nonbinary author.

My predictions:

Shadow panel winner: Tongues of Fire by Seán Hewitt

Official winner: Surge by Jay Bernard

Have you read anything from this year’s shortlist?

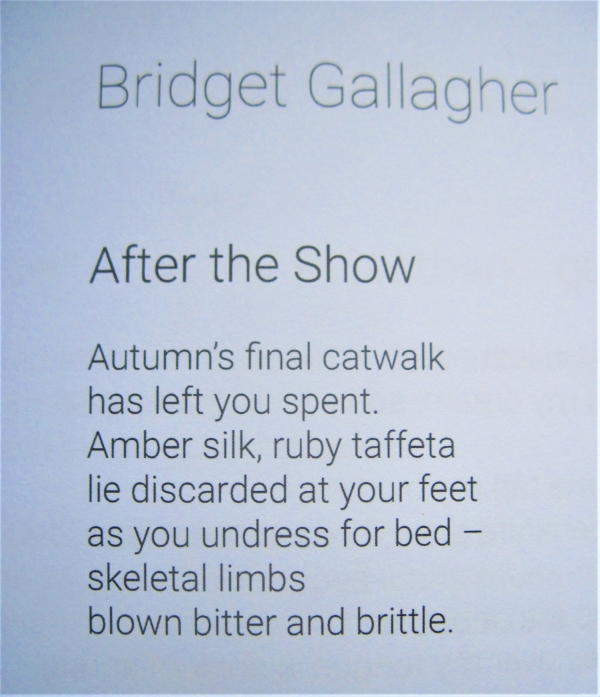

The IRON Book of Tree Poetry (Blog Tour)

Though I’d only heard of two of the contributors, my love for nature and environmentalist themes made this anthology irresistible. The authors of the 50 poems write about individual and generic trees; forests real and imagined; environmental crisis and personal reckonings. In Sarah Mnatzaganian’s “Father Tree,” a sprawling horse-chestnut symbolizes her dying father and his motherland. Dominic Weston’s “Ancestry.com” literalizes the language of the family tree. In Celia McCulloch’s “Rhododendrons at Stapleford Wood,” an invasive species is a politically charged token of prejudice: “Is it just our xenophobia, this hatred for the Greek-named / tree, the immigrant, the Windrush plantation?”

Though I’d only heard of two of the contributors, my love for nature and environmentalist themes made this anthology irresistible. The authors of the 50 poems write about individual and generic trees; forests real and imagined; environmental crisis and personal reckonings. In Sarah Mnatzaganian’s “Father Tree,” a sprawling horse-chestnut symbolizes her dying father and his motherland. Dominic Weston’s “Ancestry.com” literalizes the language of the family tree. In Celia McCulloch’s “Rhododendrons at Stapleford Wood,” an invasive species is a politically charged token of prejudice: “Is it just our xenophobia, this hatred for the Greek-named / tree, the immigrant, the Windrush plantation?”

I enjoyed the playful use of myth in Pauline Plummer’s “The Baobab”: “When God made the baobab He gave / it to the hyena, who laughed and laughed / throwing it into the scrub / where it landed upside down, dancing.” In “Abele,” Di Slaney envisions her post-mortem body feeding a woodland’s worth of creatures and being reincorporated into the flesh of trees.

Again and again, trees serve as a reminder of time passing, of seasons changing, of the vanity of human concerns compared to their centuries-old solidity – as in the final stanza of Mary Anne Perkins’s “To an Unpopular Poplar”:

This summer’s end, if I could translate

just one full hour of the whisperings

between your shimmered leaves,

how much the wiser I might be.

Thematic organization, rather than alphabetical, would have made more sense for this volume, but I appreciated the introduction to many new-to-me poets. Two favorite seasonal poems are pictured below.

My thanks to IRON Press for the free copy for review.

I was delighted to be invited to take part in the blog tour for The IRON Book of Tree Poetry. See below for where more reviews have appeared or will be appearing.

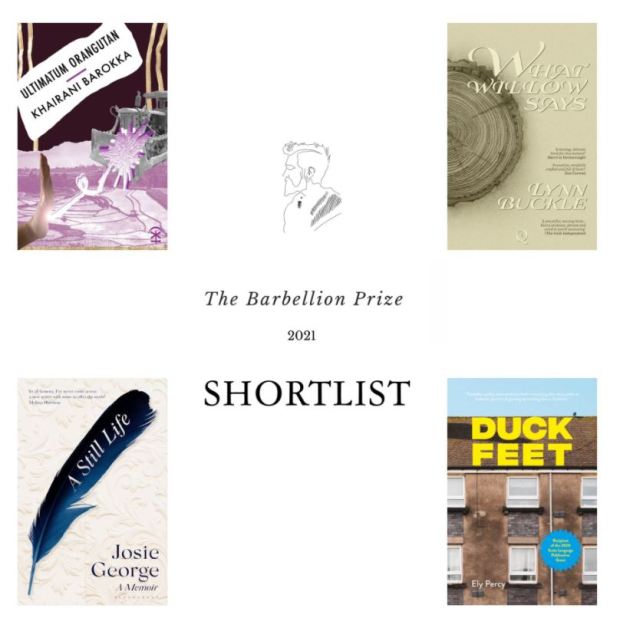

Barokka is an Indonesian poet and performance artist based in London. The topics of her second collection include chronic pain, the oppression of women, and the environmental crisis. While she’s distressed at the exploitation of nature, she sprinkles in humanist reminders of Indigenous peoples whose needs should also be valued. For instance, in the title poem, whose points of reference range from King Kong to palm oil plantations, she acknowledges that orangutans must be saved, but that people are also suffering in her native Indonesia. It’s a subtle plea for balanced consideration.

Barokka is an Indonesian poet and performance artist based in London. The topics of her second collection include chronic pain, the oppression of women, and the environmental crisis. While she’s distressed at the exploitation of nature, she sprinkles in humanist reminders of Indigenous peoples whose needs should also be valued. For instance, in the title poem, whose points of reference range from King Kong to palm oil plantations, she acknowledges that orangutans must be saved, but that people are also suffering in her native Indonesia. It’s a subtle plea for balanced consideration.

This is a delicate novella about the bond between a grandmother and her eight-year-old granddaughter, who is deaf. After the death of the girl’s mother, Grandmother has been her primary guardian. She raises her on Irish legends and a love of nature, especially their local trees. They mourn when they see hedgerows needlessly flailed, and the girl often asks what her grandmother hears the trees saying. Because Grandmother narrates in the form of journal entries, there is dramatic irony between what readers learn and what she is not telling the little girl; we ache to think about what might happen for her in the future.

This is a delicate novella about the bond between a grandmother and her eight-year-old granddaughter, who is deaf. After the death of the girl’s mother, Grandmother has been her primary guardian. She raises her on Irish legends and a love of nature, especially their local trees. They mourn when they see hedgerows needlessly flailed, and the girl often asks what her grandmother hears the trees saying. Because Grandmother narrates in the form of journal entries, there is dramatic irony between what readers learn and what she is not telling the little girl; we ache to think about what might happen for her in the future.

Allen-Paisant, from Jamaica and now based in Leeds, describes walking in the forest as an act of “reclamation.” For people of colour whose ancestors were perhaps sent on forced marches, hiking may seem strange, purposeless (the subject of “Black Walking”). Back in Jamaica, the forest was a place of utility rather than recreation:

Allen-Paisant, from Jamaica and now based in Leeds, describes walking in the forest as an act of “reclamation.” For people of colour whose ancestors were perhaps sent on forced marches, hiking may seem strange, purposeless (the subject of “Black Walking”). Back in Jamaica, the forest was a place of utility rather than recreation: The emotional scope of the poems is broad: the author fondly remembers his brick-making ancestors and his honeymoon; he sombrely imagines the last moments of an old man dying in a hospital; he expresses guilt over accidentally dismembering an ant, yet divulges that he then destroyed the ants’ nest deliberately. There are even a couple of cheeky, carnal poems, one about a couple of teenagers he caught copulating in the street and one, “The Hottest Day of the Year,” about a longing for touch. “Matter,” in ABAB stanzas, is on the theme of racial justice by way of the Black Lives Matter movement.

The emotional scope of the poems is broad: the author fondly remembers his brick-making ancestors and his honeymoon; he sombrely imagines the last moments of an old man dying in a hospital; he expresses guilt over accidentally dismembering an ant, yet divulges that he then destroyed the ants’ nest deliberately. There are even a couple of cheeky, carnal poems, one about a couple of teenagers he caught copulating in the street and one, “The Hottest Day of the Year,” about a longing for touch. “Matter,” in ABAB stanzas, is on the theme of racial justice by way of the Black Lives Matter movement. What came through particularly clearly for me was the older generation’s determination to not be a burden: living through the Second World War gave them a sense of perspective, such that they mostly did not complain about their physical ailments and did not expect heroic measures to be made to help them. (Her father knew his condition was “becoming too much” to deal with, and Granny Rosie would sometimes say, “I’ve had enough of me.”) In her father’s case, this was because he held out hope of an afterlife. Although Mosse does not share his religious beliefs, she is glad that he had them as a comfort.

What came through particularly clearly for me was the older generation’s determination to not be a burden: living through the Second World War gave them a sense of perspective, such that they mostly did not complain about their physical ailments and did not expect heroic measures to be made to help them. (Her father knew his condition was “becoming too much” to deal with, and Granny Rosie would sometimes say, “I’ve had enough of me.”) In her father’s case, this was because he held out hope of an afterlife. Although Mosse does not share his religious beliefs, she is glad that he had them as a comfort. Mario Batali is the book’s presiding imp. In 2002–3, Buford was an unpaid intern in the kitchen of Batali’s famous New York City restaurant, Babbo, which serves fancy versions of authentic Italian dishes. It took 18 months for him to get so much as a thank-you. Buford’s strategy was “be invisible, be useful, and eventually you’ll be given a chance to do more.”

Mario Batali is the book’s presiding imp. In 2002–3, Buford was an unpaid intern in the kitchen of Batali’s famous New York City restaurant, Babbo, which serves fancy versions of authentic Italian dishes. It took 18 months for him to get so much as a thank-you. Buford’s strategy was “be invisible, be useful, and eventually you’ll be given a chance to do more.” I was delighted to learn that this year Buford released a sequel of sorts, this one about French cuisine: Dirt. It’s on my wish list.

I was delighted to learn that this year Buford released a sequel of sorts, this one about French cuisine: Dirt. It’s on my wish list.

Along with an agricultural center, the American Baptist missionaries were closely associated with a hospital, Hôpital le Bon Samaritain, run by amateur archaeologist Dr. Hodges and his family. Although Apricot and her two younger sisters were young enough to adapt easily to life in a developing country, they were disoriented each time the family returned to California in between assignments. Their bonds were shaky due to her father’s temper, her parents’ rocky relationship, and the jealousy provoked over almost adopting a Haitian baby girl.

Along with an agricultural center, the American Baptist missionaries were closely associated with a hospital, Hôpital le Bon Samaritain, run by amateur archaeologist Dr. Hodges and his family. Although Apricot and her two younger sisters were young enough to adapt easily to life in a developing country, they were disoriented each time the family returned to California in between assignments. Their bonds were shaky due to her father’s temper, her parents’ rocky relationship, and the jealousy provoked over almost adopting a Haitian baby girl.

We Were the Mulvaneys by Joyce Carol Oates (oats!)

We Were the Mulvaneys by Joyce Carol Oates (oats!)

Of course, not all of my selections were explicitly food-related; others simply had food words in their titles (or, as above, in the author’s name). Of these, my favorite was a reread,

Of course, not all of my selections were explicitly food-related; others simply had food words in their titles (or, as above, in the author’s name). Of these, my favorite was a reread,