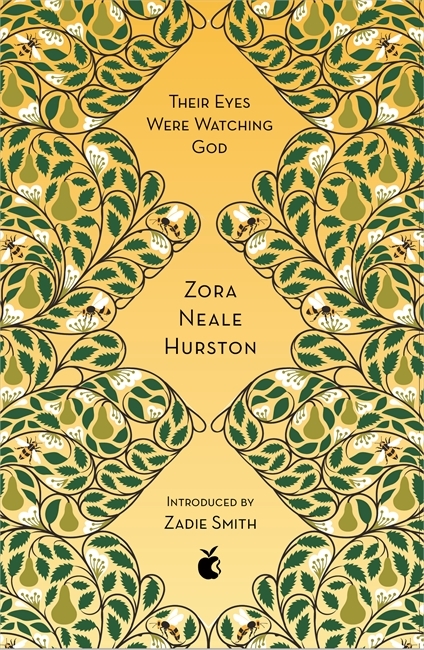

Literary Wives Club: Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston (1937)

This is one of those classics I’ve been hearing about for decades and somehow never read – until now. Right from the start, I could spot its influence on African American writers such as Toni Morrison. Hurston deftly reproduces the all-Black milieu of Eatonville, Florida, bringing characters to life through folksy speech and tying into a venerable tradition through her lyrical prose. As the novel opens, Janie Crawford, forty years old but still a looker, sets tongues wagging when she returns to town “from burying the dead.” Her friend Pheoby asks what happened and the narrative that unfolds is Janie’s account of her three marriages.

{SPOILERS IN THE REMAINDER!}

- To protect Janie’s reputation and prospects, her grandmother, who grew up in the time of slavery, marries Janie off to an old farmer, Logan Killicks, at age 16. He works her hard and treats her no better than one of his animals.

- She then runs off with handsome, ambitious Joe Starks. [A comprehension question here: was Janie technically a bigamist? I don’t recall there being any explanation of her getting an annulment or divorce.] He opens a general store and becomes the town mayor. Janie is, again, a worker, but also a trophy wife. While the townspeople gather on the porch steps to shoot the breeze, he expects her to stay behind the counter. The few times we hear her converse at length, it’s clear she’s wise and well-spoken, but in the 20 years they are together Joe never allows her to come into her own. He also hits her. “The years took all the fight out of Janie’s face.” When Joe dies of kidney failure, she is freer than before: a widow with plenty of money in the bank.

- Nine months after Joe’s death, Janie is courted by Vergible Woods, known to all as “Tea Cake.” He is about a decade younger than her (Joe was a decade older, but nobody made a big deal out of that), but there is genuine affection and attraction between them. Tea Cake is a lovable scoundrel, not to be trusted around money or other women. They move down to the Everglades and she joins him as an agricultural labourer. The difference between this and being Killicks’ wife is that Janie takes on the work voluntarily, and they are equals there in the field and at home.

In my favourite chapter, a hurricane hits. The title comes from this scene and gives a name to Fate. Things get really melodramatic from this point, though: during their escape from the floodwaters, Tea Cake has to fend off a rabid dog to save Janie. He is bitten and contracts rabies which, untreated, leads to madness. When he comes at Janie with a pistol, she has to shoot him with a rifle. A jury rules it an accidental death and finds Janie not guilty.

I must admit that I quailed at pages full of dialogue – dialect is just hard to read in large chunks. Maybe an audiobook or film would be a better way to experience the story? But in between, Hurston’s exposition really impressed me. It has scriptural, aphoristic weight to it. Get a load of her opening and closing paragraphs:

Ships at a distance have every man’s wish on board. For some they come in with the tide. For others they sail forever on the horizon, never out of sight, never landing until the Watcher turns his eyes away in resignation, his dreams mocked to death by Time. That is the life of men.

Here was peace. [Janie] pulled in her horizon like a great fish-net. Pulled it from around the waist of the world and draped it over her shoulder. So much of life in its meshes! She called in her soul to come and see.

There are also beautiful descriptions of Janie’s state of mind and what she desires versus what she feels she has to settle for. “Janie saw her life like a great tree in leaf with the things suffered, things enjoyed, things done and undone. Dawn and doom was in the branches.” She envisions happiness as sitting under a pear tree; bees buzzing in the blossom above and all the time in the world for contemplation. (It was so pleasing when I realized this is depicted on the Virago Modern Classics cover.)

I was delighted that the question of having babies simply never arises. No one around Janie brings up motherhood, though it must have been expected of her in that time and community. Her first marriage was short and, we can assume, unconsummated; her second gradually became sexless; her third was joyously carnal. However, given that both she and her mother were born of rape, she may have had traumatic associations with pregnancy and taken pains to prevent it. Hurston doesn’t make this explicit, yet grants Janie freedom to take less common paths.

What with the symbolism, the contrasts, the high stakes and the theatrical tragedy, I felt this would be a good book to assign to high school students instead of or in parallel with something by John Steinbeck. I didn’t fall in love with it in the way Zadie Smith relates in her introduction, but I did admire it and was glad to finally experience this classic of African American literature. (Secondhand purchase – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

- A marriage without love is miserable. Marriage is not a cure for loneliness.

There are years that ask questions and years that answer. Janie had had no chance to know things, so she had to ask. Did marriage end the cosmic loneliness of the unmated? Did marriage compel love like the sun the day?

(These are rhetorical questions, but the answer is NO.)

- Every marriage is different. But it works best when there is equality of labour, status and finances. Marriage can change people.

Pheoby says to Janie when she confesses that she’s thinking about marrying Tea Cake, “you’se takin’ uh awful chance.” Janie replies, “No mo’ than Ah took befo’ and no mo’ than anybody else takes when dey gits married. It always changes folks, and sometimes it brings out dirt and meanness dat even de person didn’t know they had in ’em theyselves.”

Later Janie says, “love ain’t somethin’ lak uh grindstone dat’s de same thing everywhere and do de same thing tuh everything it touch. Love is lak de sea. It’s uh movin’ thing, but still and all, it takes its shape from de shore it meets, and it’s different with every shore.”

This was a perfect book to illustrate the sorts of themes we usually discuss!

See Kate’s, Kay’s and Naomi’s reviews, too!

Coming up next, in December: Euphoria by Elin Cullhed (about Sylvia Plath)

Women’s Prize 2024: Longlist Predictions vs. Wishes

This is the fourth year in a row that I’ve made predictions for the Women’s Prize longlist (the real thing comes out on Tuesday, 6 p.m. GMT). It shows how invested I’ve become in this prize in recent years. Like I did last year, I’ll give predictions, then wishes (no overlap this time!). My wishes are based on what I have already read and want to read. Although I kept tabs on publishers and ‘free entries’ for previous winners and shortlistees, I didn’t let quotas determine my selections. And while I kept in mind that there are two novelists on the judging panel, I don’t know enough about any of these judges’ taste to be able to tailor my predictions. My only thought was that they will probably appreciate good old-fashioned storytelling … but also innovative storytelling.

(There are two books – The List of Suspicious Things by Jennie Godfrey (= Joanna Cannon?) and Jaded by Ela Lee (this year’s Queenie) – that I only heard about as I was preparing this post and seem pretty likely, but I felt that it would be cheating for me to include them.)

Predictions

The Three of Us, Ore Agbaje-Williams

The Future, Naomi Alderman

The Storm We Made, Vanessa Chan

Penance, Eliza Clark

The Wren, The Wren, Anne Enright

A House for Alice, Diana Evans

Piglet, Lottie Hazell

Pineapple Street, Jenny Jackson

Yellowface, R. F. Kuang

Biography of X, Catherine Lacey

Julia, Sandra Newman

The Vulnerables, Sigrid Nunez

Tom Lake, Ann Patchett

In Memory of Us, Jacqueline Roy

The Fraud, Zadie Smith

Land of Milk and Honey, C. Pam Zhang

Wish List

Family Lore, Elizabeth Acevedo

The Sleep Watcher, Rowan Hisayo Buchanan

The Unfortunates, J. K. Chukwu

The Three Graces, Amanda Craig

Learned by Heart, Emma Donoghue

Service, Sarah Gilmartin

The Vaster Wilds, Lauren Groff

Reproduction, Louisa Hall

Happiness Falls, Angie Kim

Bright Young Women, Jessica Knoll

A Sign of Her Own, Sarah Marsh

The Fetishist, Katherine Min

Hello Beautiful, Ann Napolitano

Mrs S, K Patrick

Romantic Comedy, Curtis Sittenfeld

Absolutely and Forever, Rose Tremain

If I’m lucky, I’ll get a few right from across these two lists; no doubt I’ll be kicking myself over the ones I considered but didn’t include, and marvelling at the ones I’ve never heard of…

What would you like to see on the longlist?

Appendix

(A further 50 novels that were on my radar but didn’t make the cut. Like last year, I made things easy for myself by keeping an ongoing list of eligible novels in a file on my desktop.)

Everything Is Not Enough, Lola Akinmade Akerstrom

The Wind Knows My Name, Isabel Allende

Swanna in Love, Jennifer Belle

The Sisterhood, Katherine Bradley

The Fox Wife, Yangsze Choo

The Guest, Emma Cline

Speak to Me, Paula Cocozza

Talking at Night, Claire Daverley

Clear, Carys Davies

Bellies, Nicola Dinan

The Happy Couple, Naoise Dolan

In Such Tremendous Heat, Kehinde Fadipe

The Memory of Animals, Claire Fuller

Anita de Monte Laughs Last, Xochitl Gonzalez

Normal Women, Ainslie Hogarth

Sunburn, Chloe Michelle Howarth

Loot, Tania James

The Half Moon, Mary Beth Keane

Morgan Is My Name, Sophie Keetch

Soldier Sailor, Claire Kilroy

8 Lives of a Century-Old Trickster, Mirinae Lee

August Blue, Deborah Levy

Winter Animals, Ashani Lewis

Rosewater, Liv Little

The Couples, Lauren Mackenzie

Tell Me What I Am, Una Mannion

She’s a Killer, Kirsten McDougall

The Misadventures of Margaret Finch, Claire McGlasson

Nightbloom, Peace Adzo Medie

I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home, Lorrie Moore

The Lost Wife, Susanna Moore

Okay Days, Jenny Mustard

Parasol against the Axe, Helen Oyeyemi

The Human Origins of Beatrice Porter and Other Essential Ghosts, Soraya Palmer

The Lodgers, Holly Pester

Night Wherever We Go, Tracey Rose Peyton

The Mars House, Natasha Pulley

Playing Games, Huma Qureshi

Come and Get It, Kiley Reid

High Time, Hannah Rothschild

Commitment, Mona Simpson

Death of a Bookseller, Alice Slater

Bird Life, Anna Smail

Stealing, Margaret Verble

Help Wanted, Adelle Waldman

Temper, Phoebe Walker

Hang the Moon, Jeannette Walls

Moral Injuries, Christie Watson

Ghost Girl, Banana, Wiz Wharton

Speak of the Devil, Rose Wilding

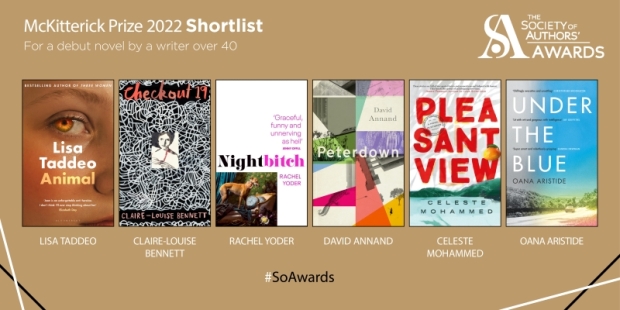

McKitterick Prize Shortlist (and Other Society of Authors Awards)

As I announced back in November, I was one of the judges for the 2022 McKitterick Prize. This is one of several prizes administered by the Society of Authors, the UK trade union for writers, which awards various grants and prizes.

The McKitterick Prize has, since 1990, been awarded to a debut novelist aged 40 or over. It’s unique in that it considers unpublished manuscripts as well as published novels – Tom McKitterick, who endowed the Prize, was a former editor of Political Quarterly and had an unpublished novel at the time of his death.

My particular role in the process was helping to assess the unpublished manuscripts and whittling them down to a longlist, which then joined the traditionally published novels for overall judging. I can’t say too much about this process or the particular narratives that I read due to the judges’ nondisclosure agreement, but I’ll make a few general observations.

Almost all of the entries were capably written and would have done fine as self-published novels, but I was looking for a touch of greatness – something that could compete, as is, with published work. For the most part, it was clear which manuscripts were at a different level. In terms of serendipitous moments, I noted multiple “meet the parents” scenes and mentions of moss or witches. Switching between 2–4 time periods was a recurring feature. There were lots of thrillers and dystopian setups, too.

The shortlist was announced this morning. None of the manuscripts made it through, but I’m delighted to see Under the Blue on there. I’ve heard a lot about the Taddeo and Yoder, both of which seem to be divisive. The Mohammed was already on my radar, I’m interested in the Bennett, and the Annand is new to me but I’ll investigate further. Judge Anietie Isong says, “These are deeply engaging works that swell with vitality.”

I was also interested to note the shortlists for the

- Betty Trask Award for a first novel by a writer under 35: it overlaps with the latest Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist on two authors, Nelson and Nolan. I’ve also read the Brown. But I’m rooting for Will McPhail’s In, the first graphic novel to be shortlisted for an SoA award.

- Gordon Bowker Volcano Prize, new this year, for a novel focusing on the experience of travel away from home (in memory of Malcolm Lowry and endowed by Gordon Bowker, his biographer): I’ve read Asylum Road and I think I have Diving for Pearls from NetGalley. I’ve read a nonfiction work by McWatt and would be interested in trying her fiction.

- Paul Torday Memorial Prize, awarded to a first novel by a writer over 60: I’ve only heard of one nominee, The Day I Fell Off My Island by Yvonne Bailey-Smith – that’s because she’s Zadie Smith’s mum.

Winners and runners-up will be announced at the SoA Awards ceremony, to be held at Southwark Cathedral on June 1st – I’ll be watching the livestream.

See any nominees you’ve read? Who would you like to see win?

Open Water & Other Contemporary Novellas Read This Year (#NovNov)

Open Water is our first buddy read, for Contemporary week of Novellas in November (#NovNov). Look out for the giveaway running on Cathy’s blog today!

I read this one back in April–May and didn’t get a chance to revisit it, but I’ll chime in with my brief thoughts recorded at the time. I then take a look back at 14 other novellas I’ve read this year; many of them I originally reviewed here. I also have several more contemporary novellas on the go to round up before the end of the month.

Open Water by Caleb Azumah Nelson (2021)

[145 pages]

I always enjoy the use of second person narration, and it works pretty well in this love story between two young Black British people in South London. The title is a metaphor for the possibilities and fear of intimacy. The protagonist, a photographer, doesn’t know what to do with his anger about how young Black men are treated. I felt Nelson was a little heavy-handed in his treatment of this theme, though I did love that the pivotal scene is set in a barbershop, a place where men reveal more of themselves than usual – I was reminded of a terrific play I saw a few years ago, Barber Shop Chronicles.

I always enjoy the use of second person narration, and it works pretty well in this love story between two young Black British people in South London. The title is a metaphor for the possibilities and fear of intimacy. The protagonist, a photographer, doesn’t know what to do with his anger about how young Black men are treated. I felt Nelson was a little heavy-handed in his treatment of this theme, though I did love that the pivotal scene is set in a barbershop, a place where men reveal more of themselves than usual – I was reminded of a terrific play I saw a few years ago, Barber Shop Chronicles.

Ultimately, I wasn’t convinced that fiction was the right vehicle for this story, especially with all the references to other authors, from Hanif Abdurraqib to Zadie Smith (NW, in particular); I think a memoir with cultural criticism was what the author really intended. I’ll keep an eye out for Nelson, though – I wouldn’t be surprised if this makes it onto the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist in January. I feel like with his next book he might truly find his voice.

Readalikes:

- Assembly by Natasha Brown (also appears below)

- Poor by Caleb Femi (poetry with photographs)

- Normal People by Sally Rooney

Other reviews:

Other Contemporary Novellas Read This Year:

(Post-1980; under 200 pages)

Somebody Loves You by Mona Arshi

Assembly by Natasha Brown

Indelicacy by Amina Cain

A Lie Someone Told You About Yourself by Peter Ho Davies

Blue Dog by Louis de Bernières

The Office of Historical Corrections by Danielle Evans

Anarchipelago by Jay Griffiths

Tinkers by Paul Harding

An Island by Karen Jennings

Ness by Robert Macfarlane

Black Dogs by Ian McEwan

Broke City by Wendy McGrath

A Feather on the Breath of God by Sigrid Nunez

In the Winter Dark by Tim Winton

Currently reading:

- Inside the Bone Box by Anthony Ferner

- My Monticello by Jocelyn Nicole Johnson

- The Cemetery in Barnes by Gabriel Josipovici

What novellas do you have underway this month? Have you read any of my selections?

Love Your Library Begins: October 2021

It’s the opening month of my new Love Your Library meme! I hope some of you will join me in writing about the libraries you use and what you’ve borrowed from them recently. I plan to treat these monthly posts as a sort of miscellany.

Although I likely won’t do thorough Library Checkout rundowns anymore, I’ll show photos of what I’ve borrowed, give links to reviews of a few recent reads, and then feature something random, such as a reading theme or library policy or display.

Do share a link to your own post in the comments, and feel free to use the above image. I’m co-opting a hashtag that is already popular on Twitter and Instagram: #LoveYourLibrary.

Here’s a reminder of my ideas of what you might choose to post (this list will stay up on the project page):

- Photos or a list of your latest library book haul

- An account of a visit to a new-to-you library

- Full-length or mini reviews of some recent library reads

- A description of a particular feature of your local library

- A screenshot of the state of play of your online account

- An opinion piece about library policies (e.g. Covid procedures or fines amnesties)

- A write-up of a library event you attended, such as an author reading or book club.

If it’s related to libraries, I want to hear about it!

Recently borrowed

Stand-out reads

The Echo Chamber by John Boyne

John Boyne is such a literary chameleon. He’s been John Irving (The Heart’s Invisible Furies), Patricia Highsmith (A Ladder to the Sky) and David Mitchell (A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom). Now, with this Internet-age state-of-the-nation satire featuring variously abhorrent characters, he’s channelling the likes of Jamie Attenberg, Jonathan Coe, Patricia Lockwood, Lionel Shriver and Emma Straub. Every member of the Cleverley family is a morally compromised fake. Boyne gives his characters amusing tics, and there are also some tremendously funny set pieces, such as Nelson’s speed dating escapade and George’s public outbursts. He links several storylines through the Ukrainian dancer Pylyp, who’s slept with almost every character in the book and has Beverley petsit for his tortoise.

John Boyne is such a literary chameleon. He’s been John Irving (The Heart’s Invisible Furies), Patricia Highsmith (A Ladder to the Sky) and David Mitchell (A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom). Now, with this Internet-age state-of-the-nation satire featuring variously abhorrent characters, he’s channelling the likes of Jamie Attenberg, Jonathan Coe, Patricia Lockwood, Lionel Shriver and Emma Straub. Every member of the Cleverley family is a morally compromised fake. Boyne gives his characters amusing tics, and there are also some tremendously funny set pieces, such as Nelson’s speed dating escapade and George’s public outbursts. He links several storylines through the Ukrainian dancer Pylyp, who’s slept with almost every character in the book and has Beverley petsit for his tortoise.

What is Boyne spoofing here? Mostly smartphone addiction, but also cancel culture. I imagined George as Hugh Bonneville throughout; indeed, the novel would lend itself very well to screen adaptation. And I loved how Beverley’s new ghostwriter, never given any name beyond “the ghost,” feels like the most real and perceptive character of all. Surely one of the funniest books I will read this year. (Full review).

Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney

I was one of those rare readers who didn’t think so much of Normal People, so to me this felt like a return to form. Conversations with Friends was a surprise hit with me back in 2017 when I read it as part of the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shadow panel the year she won. The themes here are much the same: friendship, nostalgia, sex, communication and the search for meaning. BWWAY is that little bit more existential: through the long-form e-mail correspondence between two friends from college, novelist Alice and literary magazine editor Eileen, we imbibe a lot of philosophizing about history, aesthetics and culture, and musings on the purpose of an individual life against the backdrop of the potential extinction of the species.

I was one of those rare readers who didn’t think so much of Normal People, so to me this felt like a return to form. Conversations with Friends was a surprise hit with me back in 2017 when I read it as part of the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shadow panel the year she won. The themes here are much the same: friendship, nostalgia, sex, communication and the search for meaning. BWWAY is that little bit more existential: through the long-form e-mail correspondence between two friends from college, novelist Alice and literary magazine editor Eileen, we imbibe a lot of philosophizing about history, aesthetics and culture, and musings on the purpose of an individual life against the backdrop of the potential extinction of the species.

Through their relationships with Felix (a rough-around-the-edges warehouse worker) and Simon (slightly older and involved in politics), Rooney explores the question of whether lasting bonds can be formed despite perceived differences of class and intelligence. The background of Alice’s nervous breakdown and Simon’s Catholicism also bring in sensitive treatments of mental illness and faith. (Full review).

This month’s feature

I spotted a few of these during my volunteer shelving and then sought out a couple more. All five are picture books composed by authors not known for their writing for children.

Islandborn by Junot Díaz (illus. Leo Espinosa): “Every kid in Lola’s school was from somewhere else.” When the teacher asks them all to draw a picture of the country they came from, plucky Lola doesn’t know how to depict the Island. Since she left as a baby, she has to interview relatives and neighbours for their lasting impressions. For one man it’s mangoes so sweet they make you cry; for her grandmother it’s dolphins near the beach. She gathers the memories into a vibrant booklet. The 2D cut-paper style reminded me of Ezra Jack Keats.

Islandborn by Junot Díaz (illus. Leo Espinosa): “Every kid in Lola’s school was from somewhere else.” When the teacher asks them all to draw a picture of the country they came from, plucky Lola doesn’t know how to depict the Island. Since she left as a baby, she has to interview relatives and neighbours for their lasting impressions. For one man it’s mangoes so sweet they make you cry; for her grandmother it’s dolphins near the beach. She gathers the memories into a vibrant booklet. The 2D cut-paper style reminded me of Ezra Jack Keats.

The Islanders by Helen Dunmore (illus. Rebecca Cobb): Robbie and his family are back in Cornwall to visit Tamsin and her family. These two are the best of friends and explore along the beach together, creating their own little island by digging a channel and making a dam. As the week’s holiday comes toward an end, a magical night-time journey makes them wonder if their wish to make their island life their real life forever could come true. The brightly coloured paint and crayon illustrations are a little bit Charlie and Lola and very cute.

The Islanders by Helen Dunmore (illus. Rebecca Cobb): Robbie and his family are back in Cornwall to visit Tamsin and her family. These two are the best of friends and explore along the beach together, creating their own little island by digging a channel and making a dam. As the week’s holiday comes toward an end, a magical night-time journey makes them wonder if their wish to make their island life their real life forever could come true. The brightly coloured paint and crayon illustrations are a little bit Charlie and Lola and very cute.

Rose Blanche by Ian McEwan (illus. Roberto Innocenti): Patriotism is assumed for the title character and her mother as they cheer German soldiers heading off to war. There’s dramatic irony in Rose being our innocent witness to deprivations and abductions. One day she follows a truck out of town and past barriers and fences and stumbles onto a concentration camp. Seeing hungry children’s suffering, she starts bringing them food. Unfortunately, this gets pretty mawkish and, while I liked some of the tableau scenes – reminiscent of Brueghel or Stanley Spencer – the faces are awful. (Based on a story by Christophe Gallaz.)

Rose Blanche by Ian McEwan (illus. Roberto Innocenti): Patriotism is assumed for the title character and her mother as they cheer German soldiers heading off to war. There’s dramatic irony in Rose being our innocent witness to deprivations and abductions. One day she follows a truck out of town and past barriers and fences and stumbles onto a concentration camp. Seeing hungry children’s suffering, she starts bringing them food. Unfortunately, this gets pretty mawkish and, while I liked some of the tableau scenes – reminiscent of Brueghel or Stanley Spencer – the faces are awful. (Based on a story by Christophe Gallaz.)

Where Snow Angels Go by Maggie O’Farrell (illus. Daniela Jaglenka Terrazzini): The snow angel Sylvie made last winter comes back to her to serve as her guardian angel, saving her from illness and accident risks. If you’re familiar with O’Farrell’s memoir I Am, I Am, I Am, this presents a similar catalogue of near-misses. For a picture book, it has a lot of words – several paragraphs’ worth on most of its 70 pages – so I imagine it’s more suitable for ages seven and up. I loved the fairy tale atmosphere, touches of humour, and drawing style.

Where Snow Angels Go by Maggie O’Farrell (illus. Daniela Jaglenka Terrazzini): The snow angel Sylvie made last winter comes back to her to serve as her guardian angel, saving her from illness and accident risks. If you’re familiar with O’Farrell’s memoir I Am, I Am, I Am, this presents a similar catalogue of near-misses. For a picture book, it has a lot of words – several paragraphs’ worth on most of its 70 pages – so I imagine it’s more suitable for ages seven and up. I loved the fairy tale atmosphere, touches of humour, and drawing style.

Weirdo by Zadie Smith and Nick Laird (illus. Magenta Fox): Kit’s birthday present is Maud, a guinea pig in a judo uniform. None of the other household pets – Derrick the cockatoo, Dora the cat, and Bob the pug – know what to make of her. Like in The Secret Life of Pets, the pets take over, interacting while everyone’s out at school and work. At first Maud tries making herself like the others, but after she spends an afternoon with an eccentric neighbour she realizes all she needs to be is herself. It’s not the first time married couple Smith and Laird have published an in-joke (their 2018 releases – an essay collection and a book of poems, respectively – are both entitled Feel Free): Kit is their daughter’s name and Maud is their pug’s. But this was cute enough to let them off.

Weirdo by Zadie Smith and Nick Laird (illus. Magenta Fox): Kit’s birthday present is Maud, a guinea pig in a judo uniform. None of the other household pets – Derrick the cockatoo, Dora the cat, and Bob the pug – know what to make of her. Like in The Secret Life of Pets, the pets take over, interacting while everyone’s out at school and work. At first Maud tries making herself like the others, but after she spends an afternoon with an eccentric neighbour she realizes all she needs to be is herself. It’s not the first time married couple Smith and Laird have published an in-joke (their 2018 releases – an essay collection and a book of poems, respectively – are both entitled Feel Free): Kit is their daughter’s name and Maud is their pug’s. But this was cute enough to let them off.

Women’s Prize Longlist Reviews (Leilani, Lockwood, and Lyon) & Predictions

Tomorrow, Wednesday the 28th, the Women’s Prize shortlist will be revealed. I have read just over half of the longlist so far and have a few more of the nominees on order from the library – though I may cancel one or two of my holds if they don’t advance to the shortlist. Also, my neighbourhood book club has applied to be one of six reading groups shadowing the shortlist this year via a Reading Agency initiative. If I do say so myself, I think we put in a rather strong application. We’ll hear later this week if we’ve been chosen – fingers crossed!

The three longlisted novels I’ve read most recently were all by L authors:

Luster by Raven Leilani

Edie’s voice is immediately engaging: cutting, funny, pithy. It reminded me of Ava’s in a fellow Women’s Prize nominee, Exciting Times, and both novels even employ a near-identical metaphor: “I wondered if Victoria was a real person or three Mitford sisters in a long coat” (Dolan) versus “all the kids stacked underneath my trench coat rejoice” (Leilani). They are also both concerned with how young women negotiate a confusing romantic landscape and look for meaning beyond a dead-end career. The African-American Edie’s entry-level work for a New York City publisher barely covers her rent at a squalid shared apartment. She’s shagged every male in the office and is now on to one she met online: Eric, a white, middle-aged archivist with an open marriage and a Black adopted daughter.

Edie’s voice is immediately engaging: cutting, funny, pithy. It reminded me of Ava’s in a fellow Women’s Prize nominee, Exciting Times, and both novels even employ a near-identical metaphor: “I wondered if Victoria was a real person or three Mitford sisters in a long coat” (Dolan) versus “all the kids stacked underneath my trench coat rejoice” (Leilani). They are also both concerned with how young women negotiate a confusing romantic landscape and look for meaning beyond a dead-end career. The African-American Edie’s entry-level work for a New York City publisher barely covers her rent at a squalid shared apartment. She’s shagged every male in the office and is now on to one she met online: Eric, a white, middle-aged archivist with an open marriage and a Black adopted daughter.

As Edie insinuates herself into Eric’s suburban New Jersey life in peculiar and sometimes unwitting ways, we learn more about her traumatic past: Both of her parents are dead, one by suicide, and she had an abortion at age 16. Along with sex, her main escape is her painting, which is described in tender detail. There are a number of amusing scenes set at off-the-wall locations, like a theme park, a clown school, and Comic Con. Leilani has a knack for capturing an entire realm of experience in just a few pages, as when she satirizes current publishing trends or encapsulates what it’s like to be a bicycle delivery person.

But, as a Goodreads acquaintance put it, all this sharp writing is rather wasted on the plot. I found the direction of the book in its second half utterly unrealistic, and never believed that Edie would have found Eric attractive in any way. (His interest in her is beyond creepy, really.) What I found most intriguing, along with the painting hobby, were Edie’s interactions with other Black characters, such as a publishing company colleague and Eric’s adopted daughter – there’s an uncomfortable sense that they should have a natural camaraderie and/or that Edie should be some kind of role model. I might have liked more of that dynamic, instead of the unbearable awkwardness of temporary instalment in a white neighbourhood. Other readalikes: Queenie, Here Is the Beehive, and On Beauty.

No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood

Priestdaddy is one of my absolute favourite books, so Lockwood’s debut novel was one of the 2021 releases I was most looking forward to reading. It took me a while to warm to, but ultimately did not disappoint. It probably helped that I was familiar with the author’s iconoclastic sense of humour. This is a work of third-person autofiction – much more so than I’d realized before I read the Acknowledgments – and to start with it feels like a flippant skewering of modern life, which for some is all about online personality and performance. A woman who became a social media star by tweeting quips like “Can a dog be twins?” reflects on life on “the portal” and under “the dictator.”

Priestdaddy is one of my absolute favourite books, so Lockwood’s debut novel was one of the 2021 releases I was most looking forward to reading. It took me a while to warm to, but ultimately did not disappoint. It probably helped that I was familiar with the author’s iconoclastic sense of humour. This is a work of third-person autofiction – much more so than I’d realized before I read the Acknowledgments – and to start with it feels like a flippant skewering of modern life, which for some is all about online personality and performance. A woman who became a social media star by tweeting quips like “Can a dog be twins?” reflects on life on “the portal” and under “the dictator.”

Midway through the book, she receives a wake-up call in the form of texts from her mother summoning her back to the Midwest for a family emergency. “It was a marvel how cleanly and completely this lifted her out of the stream of regular life.” Shit just got real, as they say. But “Would it change her?” she asks herself. Apparently, this very thing happened to Lockwood’s own family, which accounts for how heartfelt the second half is – still funny, but with an ache behind it, the same that I sensed and loved in Priestdaddy.

It is the about-face that makes this novel, forcing readers to question the value of a digital existence based on glib pretence. As the protagonist tells her students at one point, “Your attention is holy,” and with life so fragile there is no time to waste. What Lockwood is trying to do here is even bigger than that, though, I think. She mocks the whole idea of plot yet takes up the mantle of the “social novel,” as if creating a new format for the Internet-age novel in short, digestible sections. I’m not sure this is as earth-shattering as all that, but it is entertaining and deceptively deep. It also feels like a very current book, playing the role that Weather did in last year’s Women’s Prize race. (See my Goodreads review for more quotes, spoiler-y discussion, and why this book held personal poignancy for me.)

Consent by Annabel Lyon

I’m always drawn to stories of sisters and this was an intriguing one, though the jacket text sets it up to be more of a thriller than it actually is. After their mother’s death, Sara, a medical ethicist, looks after Mattie, her intellectually disabled sister. When Mattie is lured into eloping, Sara’s protective instinct goes into overdrive. Meanwhile, Saskia, a graduate student in French literature, feels obliged to put her twin sister Jenny’s needs first after a car accident leaves Jenny in a coma. There are two decades separating the sets of sisters, but aspects of their experiences reverberate, with fashion, perfume, and alcoholism appearing as connecting elements even before a more concrete link emerges.

I’m always drawn to stories of sisters and this was an intriguing one, though the jacket text sets it up to be more of a thriller than it actually is. After their mother’s death, Sara, a medical ethicist, looks after Mattie, her intellectually disabled sister. When Mattie is lured into eloping, Sara’s protective instinct goes into overdrive. Meanwhile, Saskia, a graduate student in French literature, feels obliged to put her twin sister Jenny’s needs first after a car accident leaves Jenny in a coma. There are two decades separating the sets of sisters, but aspects of their experiences reverberate, with fashion, perfume, and alcoholism appearing as connecting elements even before a more concrete link emerges.

For much of the novel, Lyon bounces between the two storylines. I occasionally confused Sara and Saskia, but I think that’s part of the point (why else would an author select two S-a names?) – their stories overlap as they find themselves in the position of making decisions on behalf of an incapacitated sister. The title invites deliberation about how control is parcelled out in these parallel situations, but I’m not sure consent was the right word to encapsulate the whole plot; it seems to give too much importance to some fleeting sexual relationships.

At times I found Lyon’s prose repetitive or detached, but I enjoyed the overall dynamic and the medical threads. There are some stylish lines that land perfectly, like “There she goes … in her lovely coat, that cashmere-and-guilt blend so few can afford. That lovely perfume she trails, lilies and guilt.” The Vancouver setting and French–English bilingualism, not things I often encounter in fiction, were also welcome, and the last few chapters are killer.

The other nominees I’ve read, with ratings and links to reviews, are:

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

Exciting Times by Naoise Dolan

Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi

Burnt Sugar by Avni Doshi

Unsettled Ground by Claire Fuller

The rest of the longlist is:

- Small Pleasures by Clare Chambers – I might read this from the library.

- The Golden Rule by Amanda Craig – I’d thought I’d give this one a miss, but I recently found a copy in a Little Free Library. My plan is to read it later in the year as part of a Patricia Highsmith kick, but I’ll move it up the stack if it makes the shortlist.

- Because of You by Dawn French – Not a chance. Right? Please!

- How the One-Armed Sister Sweeps Her House by Cherie Jones – A DNF; I would only try it again from the library if it was shortlisted.

- Nothing but Blue Sky by Kathleen MacMahon – I might read this from the library.

- Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters – I will definitely read this from the library.

- Summer by Ali Smith – I struggle with her work and haven’t enjoyed this series; I would only read this if it was shortlisted and my book club was assigned it!

My ideal shortlist (a wish list based on my reading and what I still want to read):

- The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett

- Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

- Exciting Times by Naoise Dolan

- Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi

- No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood

- Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters

vs.

My predicted shortlist and reasoning:

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett – A dead cert. I’ve said so since I reviewed it in June 2020.

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett – A dead cert. I’ve said so since I reviewed it in June 2020.- Burnt Sugar by Avni Doshi – Others don’t seem to fancy Doshi’s chances, and it’s true that she was already shortlisted for the Booker, but I feel like this could be more unifying a choice for the judges than, e.g. Clarke or Lockwood.

- Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi – Another definite.

- Luster by Raven Leilani – Not as strong as the Dolan, in my opinion, but it seems to have a lot of love from these judges (especially Vick Hope, who emphasized how perfectly it captured what it’s like to be young today), and from critics generally.

- Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters – Ordinarily I would have said the Prize is too staid to shortlist a trans author, but after all the online abuse that has been directed at Peters, I think the judges will want to make a stand in support of her legitimacy.

- Summer by Ali Smith – The most establishment author on the list, and not one I generally care for, but this would be a way of recognizing the four-part Seasons opus and her work in general. Of the middle-aged white cohort, she seems most likely.

I will happily accept some mixture of my wished-for and predicted titles, and would be surprised if any of the five books I have not mentioned is shortlisted. (Though quite a few others are predicting that Claire Fuller will advance; I’d have no problem with that.) I don’t think my book club would get a say in which of the six titles we’d be sent to read for the shadowing project, which is risky as I may have already read it and not want to reread, or it may be a surprise nominee that I don’t want to read, but I’ll cross that bridge if we come to it.

Callum, Eric, Laura and Rachel have been posting lots of reviews and thoughts related to the Women’s Prize. Have a look at their blogs!

Rachel also produced a priceless spreadsheet of all the Prize nominees by year, so you can tick off the ones you’ve read. I’m up to 150 now!

Doorstopper of the Month: The Emperor’s Children by Claire Messud (2006)

My impression of Claire Messud is that she’s admired by critics but unpopular with ordinary readers (e.g. this novel has a catastrophically low average rating on Goodreads, probably because of that “unlikable characters” chestnut). I fit into both categories, so was curious to see where I would fall on the appreciation spectrum. Doubly intrigued by Susan’s inclusion of The Emperor’s Children on her list of top New York novels, I finally picked up the copy I’d gotten from the free mall bookshop where I volunteered weekly in ordinary times.

I don’t think it’s a spoiler to tell you that this is a 9/11 novel. It opens in March 2001 and covers the next eight months, with “the towers” first getting a mention at the halfway point. There’s heavy irony in one character commenting to another in the first week of September, “Whatever else they may be, our times are almost criminally uninteresting. The dullest times ever.” As in a couple of novels I read last year (not naming them in case that is a spoiler), the terrorist attacks wake the main characters up from a stupor of entitlement and apathy.

I don’t think it’s a spoiler to tell you that this is a 9/11 novel. It opens in March 2001 and covers the next eight months, with “the towers” first getting a mention at the halfway point. There’s heavy irony in one character commenting to another in the first week of September, “Whatever else they may be, our times are almost criminally uninteresting. The dullest times ever.” As in a couple of novels I read last year (not naming them in case that is a spoiler), the terrorist attacks wake the main characters up from a stupor of entitlement and apathy.

The trio of protagonists, all would-be journalists aged 30, have never really had to grow up. Marina still lives with her parents, social worker Annabel and respected cultural pundit Murray Thwaite. She got an advance to write a book on children’s fashions, but the project has languished for years. Her best friend Danielle is a documentary maker mired in an affair with an older man. Their other close pal is half-Vietnamese Julius, whose new boyfriend keeps him in the luxurious lifestyle to which he’s become accustomed.

The arrival of two young men sets the plot in motion. Through Danielle, Marina meets Ludovic Seeley, who has moved from Australia to New York City to launch a magazine, The Monitor, for which he is soliciting cutting-edge cultural exposés. Meanwhile, Murray’s nephew, college dropout Frederick Tubb, who has the unfortunate nickname of “Bootie,” has moved to the City to seek his fortune. Murray offers him a job as his amanuensis, but what Bootie learns leads him to wish he could expose his idolized uncle as an intellectual fraud.

For these characters, leaving an extended childhood behind means getting out from under the shadow of a previous generation and reassessing what is admirable and who is expendable. As Marina’s book title (The Emperor’s Children Have No Clothes) indicates, appearance and substance do not always match. I won’t give away what 9/11 means for this fictional world, though I’d be interested in discussing it in the comments with anyone who’s read the book. Bootie was my favorite, and what happens with him is particularly interesting.

This was thoroughly engrossing: richly textured and intellectually satisfying in a way that might call to mind George Eliot and Edith Wharton – or, more recently, Jennifer Egan and Zadie Smith. Great American Novel territory, for sure. I’ll be keen to read more by Messud.

Page count: 581

My rating:

It’s just over five years since many of us were introduced to Wigtown and the ups and downs of running a bookshop there through Shaun Bythell’s

It’s just over five years since many of us were introduced to Wigtown and the ups and downs of running a bookshop there through Shaun Bythell’s

An indigenous human rights lawyer, Aguon is passionate about protecting his homeland of Guam, which is threatened by climate change and military expansion. His tender collage of autobiographical vignettes and public addresses inspires activism and celebrates beauty worth preserving. The U.S. Department of Defense’s plan to site more Marines and firing ranges on Guam will destroy more than 1,000 acres of limestone forest—home to endemic and endangered species, including the Mariana eight-spot butterfly. Aguon has been a lead litigator in appeals rising all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Rejecting fatalism, he endorses peaceful resistance. Two commencement speeches, poems, a eulogy and an interview round out the varied and heartfelt collection.

An indigenous human rights lawyer, Aguon is passionate about protecting his homeland of Guam, which is threatened by climate change and military expansion. His tender collage of autobiographical vignettes and public addresses inspires activism and celebrates beauty worth preserving. The U.S. Department of Defense’s plan to site more Marines and firing ranges on Guam will destroy more than 1,000 acres of limestone forest—home to endemic and endangered species, including the Mariana eight-spot butterfly. Aguon has been a lead litigator in appeals rising all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Rejecting fatalism, he endorses peaceful resistance. Two commencement speeches, poems, a eulogy and an interview round out the varied and heartfelt collection.

Crossing to Safety with Laila (Big Reading Life)

Crossing to Safety with Laila (Big Reading Life)

Dreams from My Father by Barack Obama: Remember when there was a U.S. president who thought deeply, searched his soul, and wrote eloquently? I first read this memoir in 2006, when Obama was an up-and-coming Democratic politician who’d given a rousing convention speech. I remembered no details, just the general sweep of Hawaii to Chicago to Kenya. On this reread I engaged most with the first third, in which he remembers a childhood in Hawaii and Indonesia, gives pen portraits of his white mother and absentee Kenyan father, and works out what it means to be black and Christian in America. By age 12, he’d stopped advertising his mother’s race, not wanting to ingratiate himself with white people. By contrast, “To be black was to be the beneficiary of a great inheritance, a special destiny, glorious burdens that only we were strong enough to bear.” The long middle section on community organizing in Chicago nearly did me in; I had to skim past it to get to his trip to Kenya to meet his paternal relatives – “Africa had become an idea more than an actual place, a new promised land”.

Dreams from My Father by Barack Obama: Remember when there was a U.S. president who thought deeply, searched his soul, and wrote eloquently? I first read this memoir in 2006, when Obama was an up-and-coming Democratic politician who’d given a rousing convention speech. I remembered no details, just the general sweep of Hawaii to Chicago to Kenya. On this reread I engaged most with the first third, in which he remembers a childhood in Hawaii and Indonesia, gives pen portraits of his white mother and absentee Kenyan father, and works out what it means to be black and Christian in America. By age 12, he’d stopped advertising his mother’s race, not wanting to ingratiate himself with white people. By contrast, “To be black was to be the beneficiary of a great inheritance, a special destiny, glorious burdens that only we were strong enough to bear.” The long middle section on community organizing in Chicago nearly did me in; I had to skim past it to get to his trip to Kenya to meet his paternal relatives – “Africa had become an idea more than an actual place, a new promised land”.  The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot: This Wellcome Book Prize winner about the use of a poor African-American woman’s cells in medical research was one of the first books to turn me onto health-themed reads. I devoured it in a few days in 2010. Once again, I was impressed at the balance between popular science and social history. Skloot conveys the basics of cell biology in a way accessible to laypeople, and uses recreated scenes and dialogue very effectively. I had forgotten the sobering details of the Lacks family experience, including incest, abuse, and STDs. Henrietta had a rural Virginia upbringing and had a child by her first cousin at age 14. At 31 she would be dead of cervical cancer, but the tissue taken from her at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins hospital became an immortal cell line. HeLa is still commonly used in medical experimentation. Consent was a major talking point at our book club Zoom meeting. Cells, once outside a body, cannot be owned, but it looks like exploitation that Henrietta’s descendants are so limited by their race and poverty. I had forgotten how Skloot’s relationship and travels with Henrietta’s unstable daughter, Deborah, takes over the book (as in the film). While I felt a little uncomfortable with how various family members are portrayed as unhinged, I still thought this was a great read.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot: This Wellcome Book Prize winner about the use of a poor African-American woman’s cells in medical research was one of the first books to turn me onto health-themed reads. I devoured it in a few days in 2010. Once again, I was impressed at the balance between popular science and social history. Skloot conveys the basics of cell biology in a way accessible to laypeople, and uses recreated scenes and dialogue very effectively. I had forgotten the sobering details of the Lacks family experience, including incest, abuse, and STDs. Henrietta had a rural Virginia upbringing and had a child by her first cousin at age 14. At 31 she would be dead of cervical cancer, but the tissue taken from her at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins hospital became an immortal cell line. HeLa is still commonly used in medical experimentation. Consent was a major talking point at our book club Zoom meeting. Cells, once outside a body, cannot be owned, but it looks like exploitation that Henrietta’s descendants are so limited by their race and poverty. I had forgotten how Skloot’s relationship and travels with Henrietta’s unstable daughter, Deborah, takes over the book (as in the film). While I felt a little uncomfortable with how various family members are portrayed as unhinged, I still thought this was a great read.  I had some surprising rereading DNFs. These were once favorites of mine, but for some reason I wasn’t able to recapture the magic: Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides, Everything Is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer, Gilead by Marilynne Robinson, and On Beauty by Zadie Smith. I attempted a second read of John Fowles’s postmodern Victorian pastiche, The French Lieutenant’s Woman, on a mini-break in Lyme Regis, happily reading the first third on location, but I couldn’t make myself finish once we were back home. And A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan was very disappointing a second time; it hasn’t aged well. Lastly, I’ve been stalled in Watership Down for a long time, but do intend to finish my reread.

I had some surprising rereading DNFs. These were once favorites of mine, but for some reason I wasn’t able to recapture the magic: Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides, Everything Is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer, Gilead by Marilynne Robinson, and On Beauty by Zadie Smith. I attempted a second read of John Fowles’s postmodern Victorian pastiche, The French Lieutenant’s Woman, on a mini-break in Lyme Regis, happily reading the first third on location, but I couldn’t make myself finish once we were back home. And A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan was very disappointing a second time; it hasn’t aged well. Lastly, I’ve been stalled in Watership Down for a long time, but do intend to finish my reread.

Back in the toxic, overcrowded City, Bea was an interior decorator and her partner a professor of anthropology. Bea left to give Agnes a better chance at life; like so many other children, she had become ill from her polluted surroundings. Now she is a bright, precocious leader in the making, fully participating in the community’s daily chores. Settlement tempts them, but the Rangers enforce nomadism. Newcomers soon swell their numbers, and there are rumors of other groups, too. Is it even a wilderness anymore if so many people live in it?

Back in the toxic, overcrowded City, Bea was an interior decorator and her partner a professor of anthropology. Bea left to give Agnes a better chance at life; like so many other children, she had become ill from her polluted surroundings. Now she is a bright, precocious leader in the making, fully participating in the community’s daily chores. Settlement tempts them, but the Rangers enforce nomadism. Newcomers soon swell their numbers, and there are rumors of other groups, too. Is it even a wilderness anymore if so many people live in it? Over the course of one late summer weekend, Wallace questions everything about the life he has built. As a gay African American, he has always been an outsider at the Midwestern university where he’s a graduate student in biochemistry. Though they vary in background and include several homosexuals, some partnered and some unattached, most of his friends are white, and he’s been so busy that he’s largely missed out on evening socializing by the lake – and skipped his father’s funeral (though there are other reasons for that as well).

Over the course of one late summer weekend, Wallace questions everything about the life he has built. As a gay African American, he has always been an outsider at the Midwestern university where he’s a graduate student in biochemistry. Though they vary in background and include several homosexuals, some partnered and some unattached, most of his friends are white, and he’s been so busy that he’s largely missed out on evening socializing by the lake – and skipped his father’s funeral (though there are other reasons for that as well). Such a fun book! I’d read the first chapter earlier in the year and set it aside, thinking it was too hip for me. I’m glad I decided to try again – it was a great read, so assured and contemporary. Once I got past a slightly contrived first chapter, I found it completely addictive. The laser-precision plotting and characterization reminded me of Jennifer Egan, Jonathan Franzen and Zadie Smith at their peak, but the sassy voice is all Reid’s own. There are no clear villains here; Alix Chamberlain could easily have filled that role, but I felt for her and for Kelley as much as I did for Emira. The fact that I didn’t think anyone was completely wrong shows how much nuance Reid worked in. The question of privilege is as much about money as it is about race, and these are inextricably intertwined.

Such a fun book! I’d read the first chapter earlier in the year and set it aside, thinking it was too hip for me. I’m glad I decided to try again – it was a great read, so assured and contemporary. Once I got past a slightly contrived first chapter, I found it completely addictive. The laser-precision plotting and characterization reminded me of Jennifer Egan, Jonathan Franzen and Zadie Smith at their peak, but the sassy voice is all Reid’s own. There are no clear villains here; Alix Chamberlain could easily have filled that role, but I felt for her and for Kelley as much as I did for Emira. The fact that I didn’t think anyone was completely wrong shows how much nuance Reid worked in. The question of privilege is as much about money as it is about race, and these are inextricably intertwined.  An intriguing set of linked short stories that combine philosophy and science fiction. Rachel and Eliza are preparing to have a baby together when an ant crawls into Rachel’s eye and she falls ill. Eliza wants to believe her partner but, as a scientist, can’t affirm something that doesn’t make sense (“We don’t need to resort to the mystical to describe physical processes,” she says). Other chapters travel to Turkey, Brazil and Texas – and even into space. It takes 60+ pages to figure out, but you can trust all the threads will converge around Rachel and her son, Arthur, who becomes an astronaut. I was particularly taken by a chapter narrated by the ant (yes, really) as it explores Rachel’s brain. Each section is headed by a potted explanation of a thought experiment from philosophy. I wasn’t entirely sure what to make of the alternative future of the two final chapters. Still, I was impressed with the book’s risk-taking and verve. It’s well worth making a rare dip into sci-fi for this one.

An intriguing set of linked short stories that combine philosophy and science fiction. Rachel and Eliza are preparing to have a baby together when an ant crawls into Rachel’s eye and she falls ill. Eliza wants to believe her partner but, as a scientist, can’t affirm something that doesn’t make sense (“We don’t need to resort to the mystical to describe physical processes,” she says). Other chapters travel to Turkey, Brazil and Texas – and even into space. It takes 60+ pages to figure out, but you can trust all the threads will converge around Rachel and her son, Arthur, who becomes an astronaut. I was particularly taken by a chapter narrated by the ant (yes, really) as it explores Rachel’s brain. Each section is headed by a potted explanation of a thought experiment from philosophy. I wasn’t entirely sure what to make of the alternative future of the two final chapters. Still, I was impressed with the book’s risk-taking and verve. It’s well worth making a rare dip into sci-fi for this one.