Love Your Library, November 2023

My thanks, as always, go to Elle for her participation in this monthly meme. Thanks also to Jana and Naomi for featuring some of their recent library reads.

Speaking of Eleanor, we had rather an exciting opportunity yesterday evening to attend one of the UK literary world’s biggest annual events. More on that in another post later today!

It’s crunch time for all the novellas and buddy reads I currently have on the go and intend to finish and write about before the end of November, which is approaching alarmingly rapidly. The 30th is also my husband’s 40th birthday, so it’s a busy week coming up!

*Note: Next month, instead of posting Love Your Library on the last Monday (Christmas), I will post one week before, on the 18th.

Lots of the below I have already reviewed for various other challenges, or will be reviewing soon.

Since last month:

READ

- Harriet Said… by Beryl Bainbridge

- The Garrick Year by Margaret Drabble

- Ferdinand, the Man with the Kind Heart by Irmgard Keun

- The Private Life of the Hare by John Lewis-Stempel

- Western Lane by Chetna Maroo

- The House of Doors by Tan Twan Eng

- Absolutely and Forever by Rose Tremain

- The Last House on Needless Street by Catriona Ward

CURRENTLY READING

- Bodily Harm by Margaret Atwood

- Stone Mattress by Margaret Atwood (on audiobook!)

- Bright Young Women by Jessica Knoll

- The Cancer Journals by Audre Lorde

- The Story Girl by L.M. Montgomery

CURRENTLY (NOT) READING

- The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie

- The Year of the Cat by Rhiannon Lucy Coslett

- Reproduction by Louisa Hall

- Findings by Kathleen Jamie (a re-read)

- Before the Light Fades by Natasha Walter

I started all of these weeks ago, but they have been languishing on various stacks and it will take a concerted effort to get back to and finish them.

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- Weyward by Emilia Hart – I read the first 48 pages. The setup is EXACTLY the same as in The Bass Rock by Evie Wyld (three women characters connected in similar ways, and set at three almost identical time periods). Unfortunately, that one’s amazing whereas this was pedestrian. I could never be bothered to pick it up.

- The Last Bookwanderer by Anna James – I read the first 36 pages and felt no impetus to read any more. The series went downhill after Book 3 in particular, but really never topped Book 1. Say no to series! Stand-alone books are fine!!

RETURNED UNREAD

- Land of Milk and Honey by C. Pam Zhang – Requested after me. Will try to get it back out another time.

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

Ferdinand, the Man with the Kind Heart by Irmgard Keun (#NovNov23 and #GermanLitMonth)

My second contribution to German Literature Month, hosted by Lizzy Siddal, after Last House Before the Mountain by Monika Helfer. I spotted this in a display of new acquisitions at my library earlier in the year and was attracted by the pointillist-modernist style of its cover (Man with a Tulip by Robert Delaunay, 1906) featuring the image of a dandyish yet slightly melancholy young man. I had never heard of the author and assumed it was a man. In fact, Irmgard Keun (1905–82) was a would-be actress who wrote five novels and fled Germany when blacklisted by the Nazis. She was then, variously, a fugitive (returning to Germany only after a false report of her suicide in The Telegraph), a lover of Joseph Roth, a single mother, and an alcoholic. (I love it when a potted author biography reads like a mini-novel!)

Ferdinand (1950) was her last novel and is a curious confection, silly and sombre to equal degrees. It draws on her experiences living by her journalism in bombed-out postwar Cologne. Ferdinand Timpe is a former soldier and POW from a large, eccentric family. His tiny rented room is actually a corridor infested by his landlady Frau Stabhorn’s noisy grandchildren. He’s numb, stumbling from one unsuitable opportunity to another, never choosing his future but letting it happen to him. He once inherited a secondhand bookshop and ran it for a while (I wish we’d heard more about this). Now he’s been talked into writing articles for a weekly paper – it turns out the editor confused him with another Ferdinand. Later he’s hired as a “cheerful adviser” who mostly listens to women complain about their husbands. He is not quite sure how he acquired his own fiancée, Luise, but hopes to weasel out of the engagement.

Each chapter feels like a self-contained story, many of them focusing on particular relatives or friends. There’s his beautiful but immoral cousin, Johanna; his ruthless businessman cousin Magnesius; his lovely but lazy mother, Laura. His descriptions are hilarious, and Keun’s vocabulary really sparkles:

“Like many businesspeople, Magnesius is a jovial and generous party animal, only to emerge as even icier and stonier later. He damascenes himself. To heighten the mood, he has jammed a green monocle in one eye, and pulled a yellow silk stocking over his head. Just now I saw him kissing the hand of a woman unknown to me and offering to buy her a brand-new Mercedes.”

“Luise is a nice girl, and I’ve got nothing against her, but her presence has something oppressive about it for me. I have examined myself and established that this feeling of oppression is not love, and is no prerequisite for marriage, not even an unhappy one. I suppose I should tell her. But I can’t.”

Our antihero gets himself into ridiculous situations, like when he’s down on his luck and pays an impromptu visit to a former professor, Dr Muck, perhaps hoping for a handout; finding him away, he has to await his return for hours while the wife hosts a ladies’ poetry evening:

I was desperate not to fall asleep. Seven times I tiptoed out to the lavatory to take a sip from my flask. In the hall I walked into a sideboard and knocked over a large china ornament – I think it may have been a wood grouse. I broke off a piece of its beak. These things are always happening to me when I’m trying to be especially careful.

Hidden beneath Ferdinand’s hapless and frivolous exterior (he wears a jerkin made from a lady’s coat; Johanna says it makes him looks like “a hurdy-gurdy man’s monkey”), however, is psychological damage. “I feel so deep-frozen. I wonder if I’ll ever thaw out in this life. … Sometimes I feel like wandering on through the entire world. Maybe eventually I’ll run into a place or a person who will make me say yes, this is it, I’ll stay here, this is my home.” His feeling of purposelessness is understandable. Wartime hardship has dented his essential optimism, and external signs of progress – currency reform, denazification – can’t blot out the memory.

There’s a heartbreaking little sequence where he traces his rapid descent into poverty and desperation through cigarettes. He once shuddered at people saving their butts, but then started doing so himself. The same happened with salvaging strangers’ fag-ends from ashtrays. And then, worst of all, rescuing butts from the gutter. “So I never even noticed that one day there was no smoker in the world so degenerate that I could look down on him. I stood so low that no one could stand below me.”

I tend to lose patience with aimless picaresque plots, but this one was worth sticking with for the language and the narrator’s amusing view of the world. I’d happily read another book by Keun if I came across one. Her best known, from the 1930s, are Gilgi and The Artificial Silk Girl.

(Penguin Modern Classics series, 2021. Translated from the German by Michael Hofmann. Public library) [172 pages]

#NovNov23 Week 4, “The Short and the Long of It”: W. Somerset Maugham & Jan Morris

Hard to believe, but it’s already the final full week of Novellas in November and we have had 109 posts so far! This week’s prompt is “The Short and the Long of It,” for which we encourage you to pair a novella with a nonfiction book or novel that deals with similar themes or topics. The book pairings week of Nonfiction November is always a favourite (my 2023 contribution is here), so think of this as an adjacent – and hopefully fun – project. I came up with two pairs: one fiction and one nonfiction. In the first case, the longer book led me to read a novella, and it was vice versa for the second.

W. Somerset Maugham

The House of Doors by Tan Twan Eng (2023)

&

Liza of Lambeth by W. Somerset Maugham (1897)

I wasn’t a huge fan of The Garden of Evening Mists, but as soon as I heard that Tan Twan Eng’s third novel was about W. Somerset Maugham, I was keen to read it. Maugham is a reliably readable author; his books are clearly classic literature but don’t pose the stylistic difficulties I now experience with Dickens, Trollope et al. And yet I know that Booker Prize followers who had neither heard of nor read Maugham have enjoyed this equally. I’m surprised it didn’t make it past the longlist stage, as I found it as revealing of a closeted gay writer’s life and times as The Master (shortlisted in 2004) but wider in scope and more rollicking because of its less familiar setting, true crime plot and female narration.

The main action is set in 1921, as “Willie” Somerset Maugham and his secretary, Gerald, widely known to be his lover, rest from their travels in China and the South Seas via a two-week stay with Robert and Lesley Hamlyn at Cassowary House in Penang, Malaysia. Robert and Willie are old friends, and all three men fought in the First World War. Willie’s marriage to Syrie Wellcome (her first husband was the pharmaceutical tycoon) is floundering and he faces financial ruin after a bad investment. He needs a good story that will sell and gets one when Lesley starts recounting to him the momentous events of 1910, including a crisis in her marriage, volunteering at the party office of Chinese pro-democracy revolutionary Dr Sun Yat Sen, and trying to save her friend Ethel Proudlock from a murder charge.

It’s clever how Tan weaves all of this into a Maugham-esque plot that alternates between omniscient third-person narration and Lesley’s own telling. The glimpses of expat life and Asia under colonial rule are intriguing, and the scene-setting and atmosphere are sumptuous – worthy of the Merchant Ivory treatment. I was left curious to read more by and about Maugham, such as Selina Hastings’ biography. (Public library)

But for now I picked up one of the leather-bound Maugham books I got for free a few years ago. Amusingly, the novella-length Liza of Lambeth is printed in the same volume with the travel book On a Chinese Screen, which Maugham had just released when he arrived in Penang.

{SPOILERS AHEAD}

This was Maugham’s debut novel and drew on his time as a medical intern in the slums of London. In tone and content it falls almost perfectly between Dickens and Hardy, because on the one hand Liza Kemp and her neighbours are cheerful paupers even though they work in factories, have too many children and live in cramped quarters; on the other hand, alcoholism and domestic violence are rife, and the wages of sexual sin are death. All seems light to start with: an all-village outing to picnic at Chingford; pub trips; and harmless wooing as Liza rebuffs sweet Tom in favour of a flirtation with married Jim Blakeston.

At the halfway point, I thought we were going full Tess of the d’Urbervilles – how is this not a rape scene?! Jim propositions her four times, ignoring her initial No and later quiet. “‘Liza, will yer?’ She still kept silence, looking away … Suddenly he shook himself, and closing his fist gave her a violent, swinging blow in the belly. ‘Come on,’ he said. And together they slid down into the darkness of the passage.” So starts their affair, which leads to Liza getting beaten up by Mrs Blakeston in the street and then dying of an infection after a miscarriage. The most awful character is Mrs Kemp, who spends the last few pages – while Liza is literally on her deathbed – complaining of her own hardships, congratulating herself on insuring her daughter’s life, and telling a blackly comic story about her husband’s corpse not fitting in his oak coffin and her and the undertaker having to jump on the lid to get it to close.

At the halfway point, I thought we were going full Tess of the d’Urbervilles – how is this not a rape scene?! Jim propositions her four times, ignoring her initial No and later quiet. “‘Liza, will yer?’ She still kept silence, looking away … Suddenly he shook himself, and closing his fist gave her a violent, swinging blow in the belly. ‘Come on,’ he said. And together they slid down into the darkness of the passage.” So starts their affair, which leads to Liza getting beaten up by Mrs Blakeston in the street and then dying of an infection after a miscarriage. The most awful character is Mrs Kemp, who spends the last few pages – while Liza is literally on her deathbed – complaining of her own hardships, congratulating herself on insuring her daughter’s life, and telling a blackly comic story about her husband’s corpse not fitting in his oak coffin and her and the undertaker having to jump on the lid to get it to close.

Liza isn’t entirely the stereotypical whore with the heart of gold, but she is a good-time girl (“They were delighted to have Liza among them, for where she was there was no dullness”) and I wonder if she could even have been a starting point for Eliza Doolittle in Pygmalion. Maugham’s rendering of the cockney accent is over-the-top –

“‘An’ when I come aht,’ she went on, ‘’oo should I see just passin’ the ’orspital but this ’ere cove, an’ ’e says to me, ‘Wot cheer,’ says ’e, ‘I’m goin’ ter Vaux’all, come an’ walk a bit of the wy with us.’ ‘Arright,’ says I, ‘I don’t mind if I do.’”

– but his characters are less caricatured than Dickens’s. And, imagine, even then there was congestion in London:

“They drove along eastwards, and as the hour grew later the streets became more filled and the traffic greater. At last they got on the road to Chingford, and caught up numbers of other vehicles going in the same direction—donkey-shays, pony-carts, tradesmen’s carts, dog-carts, drags, brakes, every conceivable kind of wheeled thing, all filled with people”

In short, this was a minor and derivative-feeling work that I wouldn’t recommend to those new to Maugham. He hadn’t found his true style and subject matter yet. Luckily, there’s plenty of other novels to try. (Free mall bookshop) [159 pages]

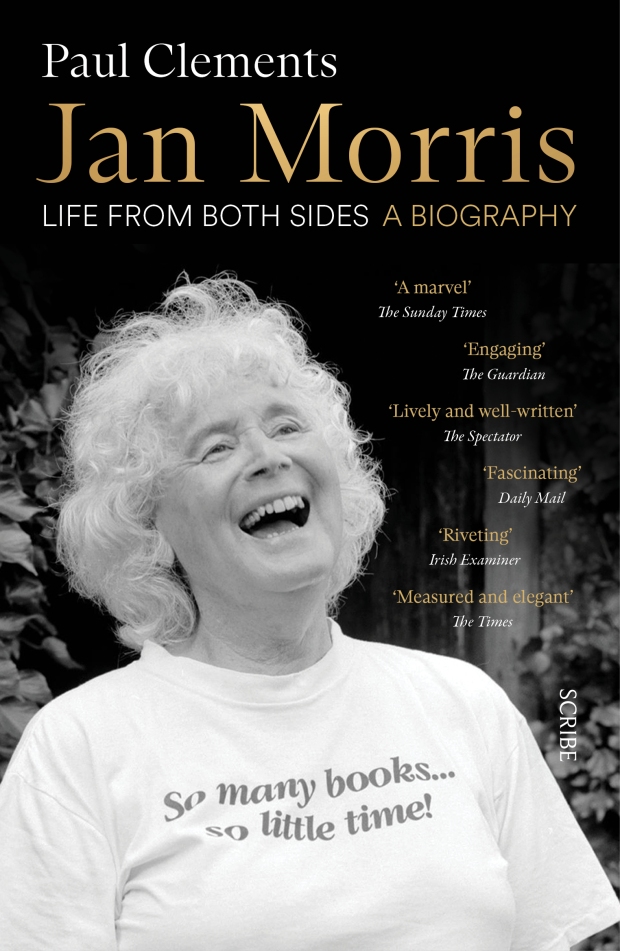

Jan Morris

Conundrum by Jan Morris (1974)

&

Jan Morris: Life from Both Sides, A Biography by Paul Clements (2022)

Back in 2021, I reread and reviewed Conundrum during Novellas in November. It’s a short memoir that documents her spiritual journey towards her true identity – she was a trans pioneer and influential on my own understanding of gender. In his doorstopper of a biography, Paul Clements is careful to use female pronouns throughout, even when this is a little confusing (with Morris a choirboy, a soldier, an Oxford student, a father, and a member of the Times expedition that first summited Everest). I’m just over a quarter of the way through the book now. Morris left the Times before the age of 30, already the author of several successful travel books on the USA and the Middle East. I’ll have to report back via Love Your Library on what I think of this overall. At this point I feel like it’s a pretty workaday biography, comprehensive and drawing heavily on Morris’s own writings. The focus is on the work and the travels, as well as how the two interacted and influenced her life.

#NovNov23 and #SciFiMonth: They by Kay Dick

To join the Week 3 theme of Novellas in November, “Broadening My Horizons,” with Science Fiction Month (celebrating a genre I still struggle with but occasionally enjoy), I decided to pick up a short rediscovered dystopian classic. Originally published in 1977, They: A Sequence of Unease was reissued by Faber Editions last year. I had never heard of its author, Kay Dick (1915–2001), a lesbian bookseller and publisher who lived in London and Brighton and wrote seven works of fiction and three biographies.

Although I can think of a few dystopian novels that I have loved, it’s not a mode I gravitate towards. This makes me out of step with the zeitgeist, I know, because dystopian stories are only rising in popularity as current events converge with premonitory visions of the future.

The specific problem I had with They is one I’ve had with some other speculative works: vagueness. I can’t stand it when allegorical books are set in a deliberate no-place, or a made-up country (I’ve not yet succeeded in reading a J.M. Coetzee or José Saramago novel, for instance). I gave up on the Giller Prize-winning Study for Obedience when its first ten pages gave no clear sense of its geographical or temporal setting. When there’s no detail to latch onto, disorientation usually leads me to turn to another more realist book in preference.

They is, in fact, set in an ironically idyllic Britain. There are lovely descriptions of the land during different seasons: roses, sunsets, wheat fields, birdsong. This is in contrast with the disquiet permeating the narrator’s everyday life. She is part of a dispersed, itinerant creative community whose members come and go, hiding their work and doing their best to avoid the nameless enforcers who patrol the country to destroy art and quash emotion and individual endeavours. Certain artists of her acquaintance have been maimed or disappeared. For all the public enshrinement of teamwork, the normies the book portrays seem purely mean-spirited: children torture animals for kicks.

A case could be made that Dick was aiming at universality – this could happen anywhere – but the combination of imprecision and flat, declarative sentences left me cold.

“We’re all frightened. We must live with it. Russell and Jane will be here tomorrow. They got through London. I’ll be sleeping in the room opposite yours tonight. You are over-tired; it’s the strain.”

“Subscribing to current social fashions, I gave a small party, inviting all my neighbours. They all talked at the same time. No one listened to anyone else. No one laughed. Only Tim and I smiled at each other. They felt uneasy because there was no television set.”

In terms of world-building, everything is either unexplained or revealed abruptly through unsubtle dialogue. I came away with no sense of the narrator or any of the many secondary characters, who are little more than a name. Funny that the most consistent presence is that of her dog, who is never given the dignity of a name. (It’s only ever “my dog,” when a creature so important to her would surely be referred to as a friend.) While the two authors were probably poles apart ideologically, I thought I spied the ghost of Ayn Rand in the awe surrounding individual achievement.

It’s comforting to try to believe what Hurst says about the persistence of art – “We can all add to the treasure, however short the time left may be. It can’t all be destroyed. Some of it will remain for those who come after us” – but this portrait of underground artists in a parallel modern Britain failed to move me. (New purchase at sale price from Faber website) [107 pages]

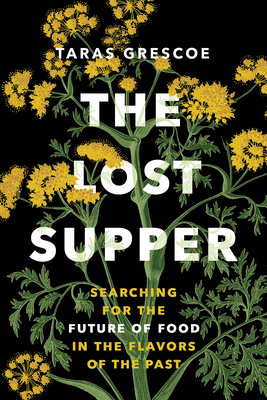

The Lost Supper by Taras Grescoe (Blog Tour)

“Searching for the Future of Food in the Flavors of the Past” is the instructive subtitle of this globe-trotting book of foodie exploration in the vein of A Cook’s Tour and The Omnivore’s Dilemma. With its firm grounding in history, it also reminded me of Twain’s Feast. Journalist Tara Grescoe is based in Montreal. Dodging Covid lockdowns, he managed to make visits to the homes of various traditional foods, such as the more nutritious emmer wheat that sustained the Çatalhöyük settlement in Turkey 8,500 years ago; the feral pigs that live on Ossabaw Island off of Georgia, USA: the Wensleydale cheese that has been made in Yorkshire for more than 700 years; the olive groves of Puglia; and the potato-like tuber called camas that is a staple for the Indigenous peoples of Vancouver Island.

One of the most fascinating chapters is about the quest to recreate “garum,” a fermented essence of salted fish (similar to modern-day Asian fish sauces) used ubiquitously by the Romans. Grescoe journeys to Cádiz, Spain, where the sauce is being made again in accordance with the archaeological findings at Pompeii. He experiences a posh restaurant tasting menu where garum features in every dish – even if just a few drops – and then has a go at making his own. “Garum seemed to subject each dish to the culinary equivalent of italicization,” he found, intensifying the existing flavours and giving an inimitable umami hit. I’m also intrigued by the possibilities of entomophagy (eating insects) so was interested in his hunt for water boatman eggs, “the caviar of Mexico”; and his outing to the world’s largest edible insect farm near Peterborough, Ontario.

Grescoe seems to be, like me, a flexitarian, focusing on plants but indulging in occasional high-quality meat and fish. He advocates for eating as locally as you can, and buying from small producers whose goods reflect the care taken over the raising. “Everybody who eats cheap, factory-made meat is eating suffering,” he insists, having compared an industrial-scale slaughterhouse in North Carolina with small farms of heritage pigs. He acknowledges other ecological problems, too, however, such as the Ossabaw hogs eating endangered loggerhead turtles’ eggs and the overabundance of sheep in the Yorkshire Dales leading to a loss of plant diversity. This ties into the ecological conscience that is starting to creep into foodie lit (as opposed to a passé Bourdain eat-everything mindset), as witnessed by Dan Saladino’s Eating to Extinction winning the Wainwright Prize (Conservation) last year.

Another major theme of the book is getting involved in the food production process yourself, however small the scale (growing herbs or tomatoes on a balcony, for instance). “With every home food-making skill I acquired, I felt like I was tapping into some deep wellspring of self-sufficiency that connected me to my historic—and even prehistoric—ancestors,” Grescoe writes. He also cites American farmer-philosopher Wendell Berry’s seven principles for responsible eating, as relevant now as they were in the 1980s. The book went a little deeper into history and anthropology than I needed, but there was still plenty here to hold my interest. Readers may not follow Grescoe into grinding their own wheat or making their own cheese, but we can all be more mindful about where our food comes from, showing gratitude rather than entitlement. This was a good Nonfiction November and pre-Thanksgiving read!

With thanks to Random Things Tours and Greystone Books for the proof copy for review.

Buy The Lost Supper from Bookshop UK [affiliate link]

I was delighted to be part of the blog tour for The Lost Supper. See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will be appearing soon.

Nonfiction November Book Pairings: Hardy’s Wives, Rituals, and Romcoms

Liz is hosting this week of Nonfiction November. For this prompt, the idea is to choose a nonfiction book and pair it with a fiction title with which it has something in common.

I came up with three based on my recent reading:

Thomas Hardy’s Wives

On my pile for Novellas in November was a tiny book I’ve owned for nearly two decades but not read until now. It contains some of the backstory for an excellent historical novel I reviewed earlier in the year.

Some Recollections by Emma Hardy

&

The Chosen by Elizabeth Lowry

The manuscript of Some Recollections is one of the documents Thomas Hardy found among his first wife’s things after her death in 1912. It is a brief (15,000-word) memoir of her early life from childhood up to her marriage – “My life’s romance now began.” Her middle-class family lived in Plymouth and moved to Cornwall when finances were tight. (Like the Bennets in Pride and Prejudice, you look at the house they lived in, and read about the servants they still employed, and think, “impoverished,” seriously?!) “Though trifling as they may seem to others all these memories are dear to me,” she writes. It’s true that most of these details seem inconsequential, of folk historical value but not particularly illuminating about the individual.

An exception is her account of her dealings with fortune tellers, who often went out of their way to give her good – and accurate – predictions, such as that she would marry a writer. It’s interesting to set this occult belief against the traditional Christian faith she espouses in her concluding paragraph, in which she insists an “Unseen Power of great benevolence directs my ways.” The other point of interest is her description of her first meeting with Hardy, who was sent to St. Juliot, where she was living with her parson brother-in-law and sister, as an architect’s assistant to begin repairs on the church. “I thought him much older than he was,” she wrote. As editor Robert Gittings notes, Hardy made corrections to the manuscript and in some places also changed the sense. Here Hardy gave proof of an old man’s continued vanity by adding “he being tired” after that line … but then partially rubbing it out. (Secondhand, Books for Amnesty, Reading, 2004) [64 pages]

The Chosen contrasts Emma’s idyllic mini memoir with her bitterly honest journals – Hardy read but then burned these, so Lowry had to recreate their entries based on letters and tone. But Some Recollections went on to influence his own autobiography, and to be published in a stand-alone volume by Oxford University Press. Gittings introduces the manuscript (complete with Emma’s misspellings and missing punctuation) and appends a selection of Hardy’s late poems based on his first marriage – this verse, too, is central to The Chosen.

Another recent nonfiction release on this subject matter that I learned about from a Shiny New Books review is Woman Much Missed: Thomas Hardy, Emma Hardy and Poetry by Mark Ford. I’d also like to read the forthcoming Hardy Women: Mother, Sisters, Wives, Muses by Paula Byrne (1 February 2024, William Collins).

Rituals

The Ritual Effect by Michael Norton

&

The Rituals by Rebecca Roberts

Last month I reviewed this lovely Welsh novel about a woman who is an independent celebrant, helping people celebrate landmark events in their lives or cope with devastating losses by commemorating them through secular rituals.

Coming out in April 2024, The Ritual Effect is a Harvard Business School behavioral scientist’s wide-ranging study of how rituals differ from habits in that they are emotionally charged and lift everyday life into something special. Some of his topics are rites of passage in different cultures; musicians’ and sportspeople’s pre-performance routines; and the rituals we develop around food and drink, especially at the holidays. I’m just over halfway through this for an early Shelf Awareness review and I have been finding it fascinating.

Romantic Comedy

(As also featured in my August Six Degrees post)

What I Was Doing While You Were Breeding by Kristin Newman

&

Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld

Romantic Comedy is probably still the most fun reading experience I’ve had this year. Sittenfeld’s protagonist, Sally Milz, writes TV comedy, as does Kristin Newman (That ’70s Show, How I Met Your Mother, etc.). What I Was Doing While You Were Breeding is a lighthearted record of her sexual conquests in Amsterdam, Paris, Russia, Argentina, etc. (Newman even has a passage that reminds me of Sally’s “Danny Horst Rule”: “I looked like a thirty-year-old writer. Not like a twenty-year-old model or actress or epically legged songstress, which is a category into which an alarmingly high percentage of Angelenas fall. And, because the city is so lousy with these leggy aliens, regular- to below-average-looking guys with reasonable employment levels can actually get one, another maddening aspect of being a woman in this city.”) Unfortunately, it got repetitive and raunchy. It was one of my 20 Books of Summer but I DNFed it halfway.

Last House Before the Mountain by Monika Helfer (#NovNov23 and #GermanLitMonth)

This Austrian novella, originally published in German in 2020, also counts towards German Literature Month, hosted by Lizzy Siddal. It is Helfer’s fourth book but first to become available in English translation. I picked it up on a whim from a charity shop.

“Memory has to be seen as utter chaos. Only when a drama is made out of it is some kind of order established.”

A family saga in miniature, this has the feel of a family memoir, with the author frequently interjecting to say what happened later or who a certain character would become, yet the focus on climactic scenes – reimagined through interviews with her Aunt Kathe – gives it the shape of autofiction.

Josef and Maria Moosbrugger live on the outskirts of an alpine village with their four children. The book’s German title, Die Bagage, literally means baggage or bearers (Josef’s ancestors were itinerant labourers), but with the connotation of riff-raff, it is applied as an unkind nickname to the impoverished family. When Josef is called up to fight in the First World War, life turns perilous for the beautiful Maria. Rumours spread about her entertaining men up at their remote cottage, such that Josef doubts the parentage of the next child (Grete, Helfer’s mother) conceived during one of his short periods of leave. Son Lorenz resorts to stealing food, and has to defend his mother against the mayor’s advances with a shotgun.

If you look closely at the cover, you’ll see it’s peopled with figures from Pieter Bruegel’s Children’s Games. Helfer was captivated by the thought of her mother and aunts and uncles as carefree children at play. And despite the challenges and deprivations of the war years, you do get the sense that this was a joyful family. But I wondered if the threats were too easily defused. They were never going to starve because others brought them food; the fending-off-the-mayor scenes are played for laughs even though he very well could have raped Maria.

Helfer’s asides (“But I am getting ahead of myself”) draw attention to how she took this trove of family stories and turned them into a narrative. I found that the meta moments interrupted the flow and made me less involved in the plot because I was unconvinced that the characters really did and said what she posits. In short, I would probably have preferred either a straightforward novella inspired by wartime family history, or a short family memoir with photographs, rather than this betwixt-and-between document.

(Bloomsbury, 2023. Translated from the German by Gillian Davidson. Secondhand purchase from Bas Books and Home, Newbury.) [175 pages]

Three in Translation for #NovNov23: Baek, de Beauvoir, Naspini

I’m kicking off Week 3 of Novellas in November, which we’ve dubbed “Broadening My Horizons.” You can interpret that however you like, but Cathy and I have suggested that you might like to review some works in translation and/or think about any new genres or authors you’ve been introduced to through novellas. Literature in translation is still at the edge of my comfort zone, so it’s good to have excuses such as this (and Women in Translation Month each August) to pick up books originally published in another language. Later in the week I’ll have a contribution or two for German Lit Month too.

I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki by Baek Se-hee (2018; 2022)

[Translated from the Korean by Anton Hur]

Best title ever. And a really appealing premise, but it turns out that transcripts of psychiatry appointments are kinda boring. (What a lazy way to put a book together, huh?) Nonetheless, I remained engaged with this because the thoughts and feelings she expresses are so relatable that I kept finding myself or other people I know in them. Themes that emerge include co-dependent relationships, pathological lying, having impossibly high standards for oneself and others, extreme black-and-white thinking, the need for attention, and the struggle to develop a meaningful career in publishing.

Best title ever. And a really appealing premise, but it turns out that transcripts of psychiatry appointments are kinda boring. (What a lazy way to put a book together, huh?) Nonetheless, I remained engaged with this because the thoughts and feelings she expresses are so relatable that I kept finding myself or other people I know in them. Themes that emerge include co-dependent relationships, pathological lying, having impossibly high standards for oneself and others, extreme black-and-white thinking, the need for attention, and the struggle to develop a meaningful career in publishing.

There are bits of context and reflection, but I didn’t get a clear overall sense of the author as a person, just as a bundle of neuroses. Her psychiatrist tells her “writing can be a way of regarding yourself three-dimensionally,” which explains why I’ve started journaling – that, and I want believe that the everyday matters, and that it’s important to memorialize.

I think the book could have ended with Chapter 14, the note from her psychiatrist, instead of continuing with another 30+ pages of vague self-help chat. This is such an unlikely bestseller (to the extent that a sequel was published, by the same title, just with “Still” inserted!); I have to wonder if some of its charm simply did not translate. (Public library) [194 pages]

The Inseparables by Simone de Beauvoir (2020; 2021)

[Translated from the French by Lauren Elkin]

Earlier this year I read my first work by de Beauvoir, also of novella length, A Very Easy Death, a memoir of losing her mother. This is in the same autobiographical mode: a lightly fictionalized story of her intimate friendship with Elisabeth Lacoin (nicknamed “Zaza”) from ages 10 to 21, written in 1954 but not published until recently. The author’s stand-in is Sylvie and Zaza is Andrée. When they meet at school, Sylvie is immediately enraptured by her bold, talented friend. “Many of her opinions were subversive, but because she was so young, the teachers forgave her. ‘This child has a lot of personality,’ they said at school.” Andrée takes a lot of physical risks, once even deliberately cutting her foot with an axe to get out of a situation (Zaza really did this, too).

Earlier this year I read my first work by de Beauvoir, also of novella length, A Very Easy Death, a memoir of losing her mother. This is in the same autobiographical mode: a lightly fictionalized story of her intimate friendship with Elisabeth Lacoin (nicknamed “Zaza”) from ages 10 to 21, written in 1954 but not published until recently. The author’s stand-in is Sylvie and Zaza is Andrée. When they meet at school, Sylvie is immediately enraptured by her bold, talented friend. “Many of her opinions were subversive, but because she was so young, the teachers forgave her. ‘This child has a lot of personality,’ they said at school.” Andrée takes a lot of physical risks, once even deliberately cutting her foot with an axe to get out of a situation (Zaza really did this, too).

Whereas Sylvie loses her Catholic faith (“at one time, I had loved both Andrée and God with ferocity”), Andrée remains devout. She seems destined to follow her older sister, Malou, into a safe marriage, but before that has a couple of unsanctioned romances with her cousin, Bernard, and with Pascal (based on Maurice Merleau-Ponty). Sylvie observes these with a sort of detached jealousy. I expected her obsessive love for Andrée to turn sexual, as in Emma Donoghue’s Learned by Heart, but it appears that it did not, in life or in fiction. In fact, Elkin reveals in a translator’s note that the girls always said “vous” to each other, rather than the more familiar form of you, “tu.” How odd that such stiffness lingered between them.

This feels fragmentary, unfinished. De Beauvoir wrote about Zaza several times, including in Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter, but this was her fullest tribute. Its length, I suppose, is a fitting testament to a friendship cut short. (Passed on by Laura – thank you!) [137 pages]

(Introduction by Deborah Levy; afterword by Sylvie Le Bon de Beauvoir, de Beavoir’s adopted daughter. North American title: Inseparable.)

Tell Me About It by Sacha Naspini (2020; 2022)

[Translated from the Italian by Clarissa Botsford]

The Tuscan novelist’s second work to appear in English has an irresistible setup: Nives, recently widowed, brings her pet chicken Giacomina into the house as a companion. One evening, while a Tide commercial plays on the television, Giacomina goes as still as a statue. Nives places a call to Loriano Bottai, the local vet and an old family friend who is known to spend every night inebriated, to ask for advice, but they stay on the phone for hours as one topic leads to another. Readers learn much about these two, whom, it soon emerges, have a history.

The Tuscan novelist’s second work to appear in English has an irresistible setup: Nives, recently widowed, brings her pet chicken Giacomina into the house as a companion. One evening, while a Tide commercial plays on the television, Giacomina goes as still as a statue. Nives places a call to Loriano Bottai, the local vet and an old family friend who is known to spend every night inebriated, to ask for advice, but they stay on the phone for hours as one topic leads to another. Readers learn much about these two, whom, it soon emerges, have a history.

The text is saturated with dialogue; quick wits and sharp tempers blaze. You could imagine this as a radio or stage play. The two characters discuss their children and the town’s scandals, including a lothario turned artist’s muse and a young woman who died by suicide. “The past is full of ghosts. For all of us. That’s how it is, and that’s how it will always be,” Loriano says. There’s a feeling of catharsis to getting all these secrets out into the open. But is there a third person on the line?

A couple of small translation issues hampered my enjoyment: the habit of alternating between calling him Loriano and Bottai (whereas Nives is always that), and the preponderance of sayings (“What’s true is that the business with the nightie has put a bee in my bonnet”), which is presumably to mimic the slang of the original but grates. Still, a good read. (Passed on by Annabel – thank you!) [128 pages]

#NovNov23 Buddy Reads Reviewed: Western Lane & A Room of One’s Own

This year we set two buddy reads for Novellas in November: one contemporary work of fiction and one classic work of short nonfiction. Do let us know if you’ve been reading them and what you think!

A version of the below review, submitted via their Facebook book club group, won me a pair of tickets to this year’s Booker Prize ceremony!

A version of the below review, submitted via their Facebook book club group, won me a pair of tickets to this year’s Booker Prize ceremony!

You may also wish to have a look at the excellent reading guide on the Booker website.

Western Lane by Chetna Maroo (2023)

In the same way that you don’t have to love baseball or video games to enjoy The Art of Fielding or Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, it’s easy to warm to Western Lane even if you’ve never played squash. Debut author Chetna Maroo assumes reader unfamiliarity with her first line: “I don’t know if you have ever stood in the middle of a squash court – on the T – and listened to what is going on next door.” As Gopi looks back to the year that she was eleven – the year after she lost her mother – what she remembers is the echo of a ball hitting a wall. That first year of mourning, which was filled with compulsive squash training, reverberates just as strongly in her memory.

To make it through, Pa tells his three daughters, “You have to address yourself to something.” That something will be their squash hobby, he decides, but ramped up to the level of an obsession. Having lost my own mother just over a year ago, I could recognize in these characters the strategies people adopt to deflect grief. Keep busy. Go numb. Ignore your feelings. Get angry for no particular reason. Even within this small family, there’s a range of responses. Pa lets his electrician business slip; fifteen-year-old Mona develops a mild shopping addiction; thirteen-year-old Khush believes she still sees their mother.

Preparing for an upcoming squash tournament gives Gopi a goal to work towards, and a crush on thirteen-year-old Ged brightens long practice days. Maroo emphasizes the solitude and concentration required, alternating with the fleeting elation of performance. Squash players hover near the central T, from which most shots can be reached. Maroo, too, sticks close to the heart. Like all the best novellas, hers maintains a laser focus on character and situation. A child point-of-view can sound precocious or condescending. That is by no means the case here. Gopi’s perspective is convincing for her age at the time, yet hindsight is the prism that reveals the spectrum of intense emotions she experienced: sadness, estrangement from her immediate family, and rejection on the one hand; first love and anticipation on the other.

This offbeat, delicate coming-of-age story eschews the literary fireworks of other Booker Prize nominees. In place of stylistic flair is the sense that each word and detail has been carefully placed. Less is more. Rather than the dark horse in the race, I’d call it the reader favourite: accessible but with hidden depths. There are cinematic scenes where little happens outwardly yet what is unspoken between the characters – the gazes and tension – is freighted with meaning. (I could see this becoming a successful indie film.)

she and my uncle stood outside under the balcony of my bedroom until much later, and I knelt above them with my blanket around me. The three of us looked out at the black shapes of the rose arbour, the trees, the railway track. Stars appeared and disappeared. My knees began to ache. Below me, Aunt Ranjan wanted badly to ask Uncle Pavan how things stood now and Uncle Pavan wanted to tell her, but she wasn’t sure how to ask and he wasn’t sure how to begin. Soon, I thought, it would be morning, and night, and morning again, and it wouldn’t matter, except to someone watching from so far off that they couldn’t know yet.

The novella is illuminating on what is expected of young Gujarati women in England; on sisterhood and a bereaved family’s dynamic; but especially on what it is like to feel sealed off from life by grief. “I think there’s a glass court inside me,” Gopi says, but over the course of one quietly momentous year, the walls start to crack. (Public library) [161 pages]

A Room of One’s Own by Virginia Woolf (1929)

Here’s the thing about Virginia Woolf. I know she’s one of the world greats. I fully acknowledge that her books are incredibly important in the literary canon. But I find her unreadable. The last time I had any success was when I was in college. Orlando and To the Lighthouse both blew me away half a lifetime ago, but I’ve not been able to reread them or force my way through anything else (and I have tried: Mrs Dalloway, The Voyage Out and The Waves). In the meantime, I’ve read several novels about Woolf and multiple Woolf-adjacent reads (ones by Vita Sackville-West, or referencing the Bloomsbury Group). So I thought a book-length essay based on lectures she gave at Cambridge’s women’s colleges in 1928 would be the perfect point of attack.

Hmm. Still unreadable. Oh well!

In the end I skimmed A Room of One’s Own for its main ideas – already familiar to me, as was some of the language – but its argumentation, reliant as much on her own made-up examples as on literary history, failed to move me. Woolf alternately imagines herself as Mary Carmichael, a lady novelist trawling an Oxbridge library and the British Museum for her forebears; and as a reader of Carmichael’s disappointingly pedestrian Life’s Adventure. If only Carmichael had had the benefit of time and money, Woolf muses, she might have been good. As it is, it would take her another century to develop her craft. She also posits a sister for Shakespeare and probes the social conditions that made her authorship impossible.

In the end I skimmed A Room of One’s Own for its main ideas – already familiar to me, as was some of the language – but its argumentation, reliant as much on her own made-up examples as on literary history, failed to move me. Woolf alternately imagines herself as Mary Carmichael, a lady novelist trawling an Oxbridge library and the British Museum for her forebears; and as a reader of Carmichael’s disappointingly pedestrian Life’s Adventure. If only Carmichael had had the benefit of time and money, Woolf muses, she might have been good. As it is, it would take her another century to develop her craft. She also posits a sister for Shakespeare and probes the social conditions that made her authorship impossible.

This is important to encounter as an early feminist document, but I would have been okay with reading just the excerpts I’d already come across.

Some favourite lines:

“I thought how unpleasant it is to be locked out; and I thought how it is worse perhaps to be locked in”

“A very queer, composite being thus emerges. Imaginatively she [the woman in literature] is of the highest importance; practically she is completely insignificant. She pervades poetry from cover to cover; she is all but absent from history.”

“Poetry depends upon intellectual freedom. And women have always been poor, not for two hundred years merely, but from the beginning of time. Women have had less intellectual freedom than the sons of Athenian slaves. Women, then, have not had a dog’s chance of writing poetry. That is why I have laid so much stress on money and a room of one’s own.”

(Secondhand purchase many years ago) [114 pages]