“The Possibilities of Place” Webinar with Nina Mingya Powles

Yesterday was National Nonfiction Day in the UK, apparently, as well as being part of the ongoing Nonfiction November challenge. Appropriately, I attended what I think must be my first writing workshop, run online by The Emma Press, a Birmingham-based publisher whose poetry and essay collections I enjoy. Thanks to Arts Council England funding, they’ve been able to arrange a series of masterclass webinars that explore some of the genres they publish.

The life writing class I participated in was led by Nina Mingya Powles, a poet and essayist whose terrific books Magnolia, Small Bodies of Water, and Tiny Moons (The Emma Press’s best-selling memoir) I’ve read and reviewed. Other attendees hailed from as far afield as Orkney, West Cork, the South of France, Berlin and New Zealand. The seminar was in Zoom presenter mode, so only Nina was on screen and the rest of us communicated via the chat box. I had been nervous about joining from my PC without a webcam or microphone, so I was relieved that this was the setup.

Nina spoke about how broad the umbrella of “life writing” is, potentially incorporating poetry and autofiction as well as straightforward prose. “Creative nonfiction” is a term sometimes used interchangeably with it. Today she wanted to focus on how memories (especially childhood memories), food and place are intertwined.

For our first warm-up exercise, she had us draw a rough map of a body of water and put a point on it, then write ourselves into that place. During this 7-minute freewrite, I compiled a list of not particularly poetic sense impressions of Annapolis harbour. I found myself crying as I realized I might never have a reason to go back to a place that was so important in my teen and early adult years.

Nina’s black-and-white cat, Otto, often butted in, in amusing and feline-appropriate ways. We proceeded to consider food as a portal to memories and to different places we’ve lived or travelled. Nina likes to think about being an outsider and the visitor’s perspective. She acknowledged that our relationships with food can be complicated, so sometimes it is a loaded topic. Mostly she is looking for gentle, tender, joyful depictions of food.

She read aloud Rebecca May Johnson’s recipe poem “to purge the desire to write like a man,” which on one level is about making tomato sauce (as is Small Fires) but ends with a “found incantation” from Natalia Ginzburg that reclaims the female realm of the kitchen as a place of power. I loved how the first stanzas describe the body as an archive, containing multitudes. Then we considered a Jennifer Wong poem, “A personal history of soups,” about all the Chinese soups she loves and misses, and their personal and legendary meanings.

She read aloud Rebecca May Johnson’s recipe poem “to purge the desire to write like a man,” which on one level is about making tomato sauce (as is Small Fires) but ends with a “found incantation” from Natalia Ginzburg that reclaims the female realm of the kitchen as a place of power. I loved how the first stanzas describe the body as an archive, containing multitudes. Then we considered a Jennifer Wong poem, “A personal history of soups,” about all the Chinese soups she loves and misses, and their personal and legendary meanings.

Taking the Wong title as our prompt, we spent 15 minutes writing a rough piece about a foodstuff. I’ve reproduced mine below, without any tidying-up. I mimicked the part-recipe format of the Johnson and tried to picture the kitchen of our first Bowie house and the cookware we had there.

A personal history of apple pie

As American as…

Dad did all the cooking when I was growing up, so for my mother to accompany me in the kitchen was a big thing. One year of my adolescence, there was a baking contest at the church my best friend and her family attended. I didn’t expect to take part at all or, if anything, perhaps I assumed I’d knock together some simple chocolate chip cookies on my own. But Mom insisted we would make an apple pie from scratch together – crust and all.

An apron each. One green, one red. Hand-embroidered heirlooms made by her grandmother. (Don’t keep them folded away in a drawer. Use them. They are your lineage, your artefacts.)

Half shortening, half butter. Glass bowl. Cold water. Half-moon cutter criss-crosses through chunks of semi-solid fat to render them smaller and smaller, flour-covered pebbles the size of peas.

Scent clouds of cinnamon and cloves billow up from a pan of stewing apples. A ceramic dish with crimping around the rim. A wooden rolling pin to achieve a uniform one-quarter inch round of dough. Freshly washed fingers gently pressing divots into the sides until every air bubble disappears.

Blind bake the crust. Trust that it will hold your creation. The sizzle of softened fruit in contact with the part-baked crust.

I have no memory of whether we won a prize. And me so competitive! The prize was the time. The prize was the attention. The assurance that this was worth it, that I was worth it.

Next we moved on to think about place and journeys, especially departures and arrivals – bringing places with us versus leaving them behind. An attendee commented, and Nina agreed, that often distance is useful: we can most easily write about somewhere after we’ve left it, once there is a sense of yearning. For this section we looked at a few-page extract from Larissa Pham’s essay collection Pop Song in which she describes a drive from Albuquerque to Taos. Expecting beautiful Georgia O’Keeffe-type scenery, she experiences the letdown of signs of the opioid crisis and Trump voters.

Borrowing a line from the Pham essay, Nina invited us to spend 20 minutes writing a piece that would bring the reader into the immediacy of our experience of a place. She reminded us, as a general rule, to remember to cite whatever we borrow, or to remove the borrowed line afterwards and see if it still works. My take on “Here I was now in the distant place…” ended up being a few rambling paragraphs contrasting my two study abroad years, one magical and one difficult. (Sample line: “Everything in England was like that: partially familiar but slightly askew.”)

At the end, three participants unmuted themselves and read their food pieces aloud. One was about food and a mother’s love; milk and rice. The other two, amusingly, were both about meringue: making a cherry meringue pie with a Scottish granny, and assembling pavlovas with aunts in New Zealand.

Nina encouraged us to think of life writing as a fluid thing, including journaling, blogging, travel and nature writing. This was heartening because I’ve always indulged in bits of autobiographical writing on my blog, and I started a journal last month as my 40th birthday approached, inspired in part by the 150 journals I inherited from my mother as well as by the desires to document my life and believe that the day-to-day has meaning.

The two-hour workshop was incredibly good value, especially considering that The Emma Press sent a voucher for £4 off of one of their books. (I’ve ordered their poetry anthology on ageing.) Nina also generously circulated lists of additional writing prompts, magazines that accept life writing submissions, and relevant competitions to enter.

I’d purchased a ticket on a whim but wasn’t sure whether I’d participate fully – I have a bad habit of skipping the exercises in books, after all. I’m so glad I did join, and gave myself over to the writing prompts. Who knows if anything will come of it, but it was cathartic to think about life experiences I don’t often have at the forefront of my mind, and to see how much can be produced in short periods of concerted writing.

Novellas in November, Week 1: My Year in Novellas (#NovNov23)

Novellas in November begins today! Cathy (746 Books) and I are delighted to be celebrating the art of the short book with you once again. Remember to let us know about your posts here, via the Inlinkz service or through a comment. How impressive is it that before November even started we were already up to 20 blog and social media posts?! I have a feeling this will be a record-breaking year for participation.

I’m kicking off our first weekly prompt:

Week 1 (starts Wednesday 1 November): My Year in Novellas

- During this partial week, tell us about any novellas you have read since last NovNov.

(See the announcement post for more info about the other weeks’ prompts and buddy reads.)

I relish building rather ludicrous stacks of novellas through the year. When I’m standing in front of a Little Free Library, browsing in secondhand bookstores and charity shops, or perusing the shelves at the public library where I volunteer, I’m always thinking about what I could add to my piles for November.

But I do read novella-length books at other times of year, too. Forty-six of them so far this year, according to my Goodreads shelves. That seems impossible, but I guess it reflects the fact that I often choose to review novellas for BookBrowse, Foreword and Shelf Awareness. I’ve read a real mixture, but predominantly literature in translation and autobiographical works. Here are seven highlights:

Fiction

How Strange a Season by Megan Mayhew Bergman: A strong short story collection with the novella-length “Indigo Run” being a Southern Gothic tale of betrayal and revenge.

Loved and Missed by Susie Boyt: The heart-wrenching story of a woman who adopts her granddaughter due to her daughter’s drug addiction. Its brevity speaks emotional volumes.

Crudo by Olivia Laing: A wry, all too relatable take on recent events and our collective hypocrisy and sense of helplessness. Biography + autofiction + cultural commentary.

Nonfiction

Diary of a Tuscan Bookshop by Alba Donati: Lovely snapshots of a bookseller’s personal and professional life.

La Vie: A Year in Rural France by John Lewis-Stempel: A ‘peasant farmer’ chronicles a year in the quest to become self-sufficient. His best book in an age, ideal for armchair travel.

My Neglected Gods by Joanne Nelson: The poignant microessays locate epiphanies in the everyday.

Eggs in Purgatory by Genanne Walsh: A stunning autobiographical essay about the last few months of her father’s life.

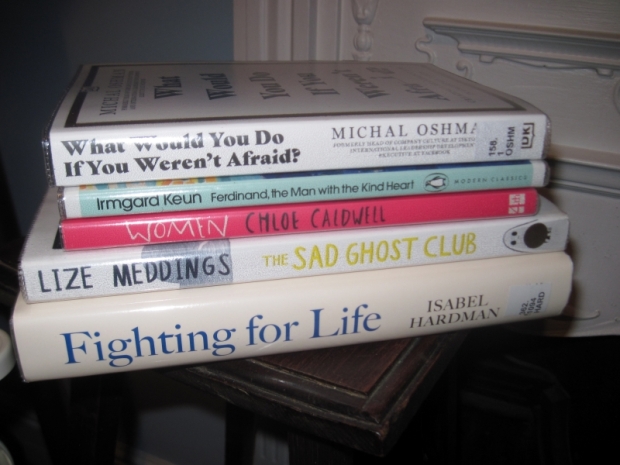

I currently have five novellas underway, and I’ve laid out a pile of potential one-sitting reads for quiet mornings in the weeks to come.

Here’s hoping you all are as excited about short books as I am!

Why not share some recent favourites with us in a post of your own?

Love Your Library (and Life Update), October 2023

My thanks, as always, to Elle for her participation in this monthly meme, and to Laura for mentioning whenever she sources a book from the library!

I’m posting a bit later than usual because it’s been a busy time, and quite an emotional rollercoaster too. First was the high of my joint 40th birthday party with my husband (whose birthday is in late November) on Saturday evening. It required close to wedding levels of event planning and was stressful, especially in the week ahead, with lots of dropouts due to illness and changed plans. Yesterday and today, I’ve been up to my knees in dirty dishes, leftovers, and soiled tablecloths and bedding to try to get washed and dry. But it was a fantastic party in the end, bringing together people from lots of different areas of our lives. I’m so grateful to everyone who came to celebrate with cake, a quiz, a ceilidh, a bring-and-share/potluck meal, and dancing to the hits of 1983.

The next day was a bit of a crash back to earth as I snuck away from the house guests to attend my church’s annual Memorial Service. With All Hallows’ Eve and then All Saints coming up, it’s a traditional time to think about the dead, but all the more so because today is the first anniversary of my mother’s death. It’s taken me the full year to understand and accept, with both mind and heart, that she’s gone. I’m not marking the day in any particular way apart from having a cup of strong Earl Grey tea in her honour. I feel close to her when I read her journals, look at photographs, or see all the many items she gave me that I still use. We recently moved her remains to a different cemetery and it’s strangely comforting to think that her plot could also accommodate at least a portion of my ashes one day.

Love Your Library

Last week I was trained in how to use the library content management system and received log-ins for limited access to return, issue and renew books and search for information on the internal catalogue. It has been interesting to see how things work from the other side, having been a customer of the library system for over a decade. At busy times I will be able to help out behind the counter, but because I have to call a senior for literally anything more complicated, I am not a replacement for an employee. It is a sad reality that some libraries have to rely on volunteers in this way; none of the smaller branches in West Berkshire would be able to stay open without volunteers working alongside staff.

Novellas in November will be here before we know it. I have a huge pile of library novellas borrowed, in addition to all the ones I own.

Since last month:

READ

- The Whispers by Ashley Audrain

- I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki by Baek Se-hee

- The Seaside by Madeleine Bunting

- Penance by Eliza Clark

- Emily Wilde’s Encyclopaedia of Faeries by Heather Fawcett

- By the Sea by Abdulrazak Gurnah (for book club)

- Milk by Alice Kinsella

- The Sad Ghost Club by Lize Meddings

CURRENTLY READING

- Western Lane by Chetna Maroo

- The Last House on Needless Street by Catriona Ward

CURRENTLY (NOT) READING

- The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie

- The Year of the Cat by Rhiannon Lucy Coslett

- Reproduction by Louisa Hall

- Weyward by Emilia Hart

- The Last Bookwanderer by Anna James

- Findings by Kathleen Jamie (a re-read)

- Before the Light Fades by Natasha Walter

I started all of the above weeks ago, but they have been languishing on various stacks and it will take a concerted effort to get back to and finish them.

RETURNED UNREAD

- The Seventh Son by Sebastian Faulks

- This Other Eden by Paul Harding

- All the Little Bird-Hearts by Viktoria Lloyd-Barlow

All were much-hyped or prize-listed novels that didn’t grab me within the first few pages, so I relinquished them to the next person in the reservation queue.

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

Novellas in November 2023 Link-Up

Novellas in November had another great year, with 52 bloggers contributing a total of 175 posts! You can peruse them all at the links below.

#1962Club: A Dozen Books I’d Read Before

I totally failed to read a new-to-me 1962 publication this year. I’m disappointed in myself as I usually manage to contribute one or two reviews to each of Karen and Simon’s year clubs, and it’s always a good excuse to read some classics.

My mistake this time was to only get one option: Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov, which I had my husband borrow for me from the university library. I opened it up and couldn’t make head or tail of it. I’m sure it’s very clever and meta, and I’ve enjoyed Nabokov before (Pnin, in particular), but I clearly needed to be in the right frame of mind for a challenge, and this month I was not.

Looking through the Goodreads list of the top 100 books from 1962, and spying on others’ contributions to the week, though, I can see that it was a great year for literature (aren’t they all?). Here are 12 books from 1962 that I happen to have read before, most of which I’ve reviewed here in the past few years. I’ve linked to those and/or given review excerpts where I have them, and the rest I describe to the best of my muzzy memory.

The Wolves of Willoughby Chase by Joan Aiken – The snowy scene on the cover and described in the first two paragraphs drew me in and the story, a Victorian-set fantasy with notes of Oliver Twist and Jane Eyre, soon did, too. Dickensian villains are balanced out by some equally Dickensian urchins and helpful adults, all with hearts of gold. There’s something perversely cozy about the plight of an orphan in children’s books: the characters call to the lonely child in all of us; we rejoice to see how ingenuity and luck come together to defeat wickedness. There are charming passages here in which familiar smells and favourite foods offer comfort. This would make a perfect stepping stone from Roald Dahl to one of the Victorian classics.

The Wolves of Willoughby Chase by Joan Aiken – The snowy scene on the cover and described in the first two paragraphs drew me in and the story, a Victorian-set fantasy with notes of Oliver Twist and Jane Eyre, soon did, too. Dickensian villains are balanced out by some equally Dickensian urchins and helpful adults, all with hearts of gold. There’s something perversely cozy about the plight of an orphan in children’s books: the characters call to the lonely child in all of us; we rejoice to see how ingenuity and luck come together to defeat wickedness. There are charming passages here in which familiar smells and favourite foods offer comfort. This would make a perfect stepping stone from Roald Dahl to one of the Victorian classics.

Instead of a Letter by Diana Athill – This was Athill’s first book, published when she was 45. An unfortunate consequence of my not having read the memoirs in the order in which they are written is that much of the content of this one seemed familiar to me. It hovers over her childhood (the subject of Yesterday Morning) and centres in on her broken engagement and abortion, two incidents revisited in Somewhere Towards the End. Although Athill’s careful prose and talent for candid self-reflection are evident here, I am not surprised that the book made no great waves in the publishing world at the time. It was just the story of a few things that happened in the life of a privileged Englishwoman. Only in her later life has Athill become known as a memoirist par excellence.

Instead of a Letter by Diana Athill – This was Athill’s first book, published when she was 45. An unfortunate consequence of my not having read the memoirs in the order in which they are written is that much of the content of this one seemed familiar to me. It hovers over her childhood (the subject of Yesterday Morning) and centres in on her broken engagement and abortion, two incidents revisited in Somewhere Towards the End. Although Athill’s careful prose and talent for candid self-reflection are evident here, I am not surprised that the book made no great waves in the publishing world at the time. It was just the story of a few things that happened in the life of a privileged Englishwoman. Only in her later life has Athill become known as a memoirist par excellence.

The Drowned World by J.G. Ballard – (Read in October 2011.) Quite possibly the first ‘classic’ science fiction work I’d ever read. I found Ballard’s debut dated, with passages of laughably purple prose, poor character development (Beatrice is an utter Bond Girl cliché), and slow plot advancement. It sounded like a promising environmental dystopia – perhaps a forerunner of Oryx and Crake – but beyond the plausible vision of a heated-up and waterlogged planet, the book didn’t have much to offer. The most memorable passage was when Strangman drains the water and Kerans discovers Leicester Square beneath; he walks the streets and finds them uninhabited except by sea creatures clogging the cinema entrances. That was quite a potent, striking image. But the scene that follows, involving stereotyped ‘Negro’ guards, seemed like a poor man’s Lord of the Flies rip-off.

The Drowned World by J.G. Ballard – (Read in October 2011.) Quite possibly the first ‘classic’ science fiction work I’d ever read. I found Ballard’s debut dated, with passages of laughably purple prose, poor character development (Beatrice is an utter Bond Girl cliché), and slow plot advancement. It sounded like a promising environmental dystopia – perhaps a forerunner of Oryx and Crake – but beyond the plausible vision of a heated-up and waterlogged planet, the book didn’t have much to offer. The most memorable passage was when Strangman drains the water and Kerans discovers Leicester Square beneath; he walks the streets and finds them uninhabited except by sea creatures clogging the cinema entrances. That was quite a potent, striking image. But the scene that follows, involving stereotyped ‘Negro’ guards, seemed like a poor man’s Lord of the Flies rip-off.

Silent Spring by Rachel Carson – Carson’s first chapter imagines an American town where things die because nature stops working as it should. Her main target was insecticides that were known to kill birds and had presumed negative effects on human health through the food chain and environmental exposure. Although the details may feel dated, the literary style and the general cautions against submitting nature to a “chemical barrage” remain potent.

Silent Spring by Rachel Carson – Carson’s first chapter imagines an American town where things die because nature stops working as it should. Her main target was insecticides that were known to kill birds and had presumed negative effects on human health through the food chain and environmental exposure. Although the details may feel dated, the literary style and the general cautions against submitting nature to a “chemical barrage” remain potent.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson – I loved the offbeat voice and unreliable narration, and the way that the Blackwood house is both a refuge and a prison for the sisters. “Where could we go?” Merricat asks Constance when she expresses concern that she should have given the girl a more normal life. “What place would be better for us than this? Who wants us, outside? The world is full of terrible people.” As the novel goes on, you ponder who is protecting whom, and from what. There are a lot of great scenes, all so discrete that I could see this working very well as a play with just a few backdrops to represent the house and garden. It has the kind of small cast and claustrophobic setting that would translate very well to the stage.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson – I loved the offbeat voice and unreliable narration, and the way that the Blackwood house is both a refuge and a prison for the sisters. “Where could we go?” Merricat asks Constance when she expresses concern that she should have given the girl a more normal life. “What place would be better for us than this? Who wants us, outside? The world is full of terrible people.” As the novel goes on, you ponder who is protecting whom, and from what. There are a lot of great scenes, all so discrete that I could see this working very well as a play with just a few backdrops to represent the house and garden. It has the kind of small cast and claustrophobic setting that would translate very well to the stage.

Tales from Moominvalley by Tove Jansson – Moomintroll discovers a dragon small enough to be kept in a jar; laughter brings a fearful child back from literal invisibility. But what struck me more was the lessons learned by neurotic creatures. In “The Fillyjonk who believed in Disasters,” the title character fixates on her belongings, but when a gale and a tornado come and sweep it all away, she experiences relief and joy. My other favourite was “The Hemulen who loved Silence.” After years as a fairground ticket-taker, he can’t wait to retire and get away from the crowds and the noise, but once he’s obtained his precious solitude he realizes he needs others after all. In “The Fir Tree,” the Moomins, awoken midway through hibernation, get caught up in seasonal stress and experience Christmas for the first time.

Tales from Moominvalley by Tove Jansson – Moomintroll discovers a dragon small enough to be kept in a jar; laughter brings a fearful child back from literal invisibility. But what struck me more was the lessons learned by neurotic creatures. In “The Fillyjonk who believed in Disasters,” the title character fixates on her belongings, but when a gale and a tornado come and sweep it all away, she experiences relief and joy. My other favourite was “The Hemulen who loved Silence.” After years as a fairground ticket-taker, he can’t wait to retire and get away from the crowds and the noise, but once he’s obtained his precious solitude he realizes he needs others after all. In “The Fir Tree,” the Moomins, awoken midway through hibernation, get caught up in seasonal stress and experience Christmas for the first time.

The Snowy Day by Ezra Jack Keats – A perennial favourite from my childhood, with a paper-collage style that has influenced many illustrators. Just looking at the cover makes me nostalgic for the sort of wintry American mornings when I’d open an eye to a curiously bright aura from around the window, glance at the clock and realize my mom had turned off my alarm because it was a snow day and I’d have nothing ahead of me apart from sledding, playing boardgames and drinking hot cocoa with my best friend. There was no better feeling.

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle – (Reread in 2021.) I probably picked this up at age seven or so, as a follow-on from the Chronicles of Narnia. Interplanetary stories have never held a lot of interest for me. As a child, I was always more drawn to talking-animal stuff. Again I found the travels and settings hazy. It’s admirable of L’Engle to introduce kids to basic quantum physics, and famous quotations via Mrs. Who, but this all comes across as consciously intellectual rather than organic and compelling. Even the home and school talk feels dated. I most appreciated the thought of a normal – or even not very bright – child like Meg saving the day through bravery and love. This wasn’t for me, but I hope that for some kids, still, it will be pure magic.

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle – (Reread in 2021.) I probably picked this up at age seven or so, as a follow-on from the Chronicles of Narnia. Interplanetary stories have never held a lot of interest for me. As a child, I was always more drawn to talking-animal stuff. Again I found the travels and settings hazy. It’s admirable of L’Engle to introduce kids to basic quantum physics, and famous quotations via Mrs. Who, but this all comes across as consciously intellectual rather than organic and compelling. Even the home and school talk feels dated. I most appreciated the thought of a normal – or even not very bright – child like Meg saving the day through bravery and love. This wasn’t for me, but I hope that for some kids, still, it will be pure magic.

The Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing – I read this feminist classic in my early twenties, in the days when I was working at a London university library. Lessing wrote autofiction avant la lettre, and the gist of this novel is that ‘Anna’, a writer, divides her life into four notebooks of different colours: one about her African upbringing, another about her foray into communism, a third containing an autobiographical novel in progress, and the fourth a straightforward journal. The fabled golden notebook is the unified self she tries to create as her romantic life and mental health become more complicated. Julianne Pachico read this recently and found it very powerful. I think I was too young for this and so didn’t appreciate it at the time. Were I to reread it, I imagine I would get a lot more out of it.

The Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing – I read this feminist classic in my early twenties, in the days when I was working at a London university library. Lessing wrote autofiction avant la lettre, and the gist of this novel is that ‘Anna’, a writer, divides her life into four notebooks of different colours: one about her African upbringing, another about her foray into communism, a third containing an autobiographical novel in progress, and the fourth a straightforward journal. The fabled golden notebook is the unified self she tries to create as her romantic life and mental health become more complicated. Julianne Pachico read this recently and found it very powerful. I think I was too young for this and so didn’t appreciate it at the time. Were I to reread it, I imagine I would get a lot more out of it.

The Pumpkin Eater by Penelope Mortimer – More autofiction. Like a nursery rhyme gone horribly wrong, this is the story of a woman who can’t keep it together. She’s the woman in the shoe, the wife whose pumpkin-eating husband keeps her safe in a pumpkin shell, the ladybird flying home to find her home and children in danger. Aged 31 and already on her fourth husband, the narrator, known only as Mrs. Armitage, has an indeterminate number of children. Her current husband, Jake, is a busy filmmaker whose philandering soon becomes clear, starting with the nanny. A breakdown at Harrods is the sign that Mrs. A. isn’t coping. Most chapters begin in medias res and are composed largely of dialogue, including with Jake or her therapist. The book has a dark, bitter humour and brilliantly recreates a troubled mind.

The Pumpkin Eater by Penelope Mortimer – More autofiction. Like a nursery rhyme gone horribly wrong, this is the story of a woman who can’t keep it together. She’s the woman in the shoe, the wife whose pumpkin-eating husband keeps her safe in a pumpkin shell, the ladybird flying home to find her home and children in danger. Aged 31 and already on her fourth husband, the narrator, known only as Mrs. Armitage, has an indeterminate number of children. Her current husband, Jake, is a busy filmmaker whose philandering soon becomes clear, starting with the nanny. A breakdown at Harrods is the sign that Mrs. A. isn’t coping. Most chapters begin in medias res and are composed largely of dialogue, including with Jake or her therapist. The book has a dark, bitter humour and brilliantly recreates a troubled mind.

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn – This was required reading in high school, a novella and circadian narrative depicting life for a prisoner in a Soviet gulag. And that’s about all I can tell you about it. I remember it being just as eye-opening and depressing as you might expect, but pretty readable for a translated classic.

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn – This was required reading in high school, a novella and circadian narrative depicting life for a prisoner in a Soviet gulag. And that’s about all I can tell you about it. I remember it being just as eye-opening and depressing as you might expect, but pretty readable for a translated classic.

A Cat in the Window by Derek Tangye – Tangye wasn’t a cat fan to start with, but Monty won him over. He lived with newlyweds Derek and Jeannie first in the London suburb of Mortlake, then on their flower farm in Cornwall. When they moved to Minack, there was a sense of giving Monty his freedom and taking joy in watching him live his best life. They were evacuated to St Albans and briefly lived with Jeannie’s parents and Scottie dog, who became Monty’s nemesis. Monty survived into his 16th year, happily tolerating a few resident birds. Tangye writes warmly and humorously about Monty’s ways and his own development into a man who is at a cat’s mercy. This was really the perfect chronicle of life with a cat, from adoption through farewell. Simon thought so, too.

A Cat in the Window by Derek Tangye – Tangye wasn’t a cat fan to start with, but Monty won him over. He lived with newlyweds Derek and Jeannie first in the London suburb of Mortlake, then on their flower farm in Cornwall. When they moved to Minack, there was a sense of giving Monty his freedom and taking joy in watching him live his best life. They were evacuated to St Albans and briefly lived with Jeannie’s parents and Scottie dog, who became Monty’s nemesis. Monty survived into his 16th year, happily tolerating a few resident birds. Tangye writes warmly and humorously about Monty’s ways and his own development into a man who is at a cat’s mercy. This was really the perfect chronicle of life with a cat, from adoption through farewell. Simon thought so, too.

Here’s hoping I make a better effort at the next year club!

Hay-on-Wye Trip & Book Haul

Our previous trip to Hay was in September 2020, when Covid restrictions meant some shops were closed and most eateries only offered takeaway or outdoor dining. At the end of my write-up, I vowed to go back before I turned 40. I stayed true to my word and we arrived in town the day before my 40th birthday. (Not only that, but I’ve completed the Triple Crown of British Book Towns in a year, what with visits to Wigtown in June and Sedbergh in August. My hauls were comparable in all three and my spending in Hay (£37.95 for 15 books) was somewhere between Sedbergh’s low (£24.50 for 13) and Wigtown’s high (£44 for 16).)

Every time we visit, we find some businesses have closed but others have opened. There’s still a core of 12 bookshops, but as in Sedbergh, there are other establishments with a few shelves of books, so there are 15–20 places in town where you can browse books. That’s plenty for anyone to be getting on with in a long weekend.

I had an action plan for our three days that moved from cheapest (honesty shelves below the castle, £1 area outside Cinema; Oxfam and British Red Cross charity shops; Hay-on-Wye Booksellers; Clock Tower Books) through mid-price (Addyman Books, Cinema) to the more expensive options (Green Ink, Booths). The town’s newest shop, as pictured in my birthday post, is Gay on Wye, which, with North Books, replaced Pembertons as sellers of new stock. (Booth’s, the Castle and the Old Electric Shop also sell curated selections of new books.)

New to us on this trip:

- The Bean Box, a terrific and reasonably priced mini coffee bar run out of a horse box by the river. They have a nice garden and a secondhand book selection, and you can sit on their patio or at tables and chairs closer to the river view.

Felin Fach Griffin, a country pub about a 20-minute drive from Hay, where we booked a table for my birthday lunch. Excellent food and a cosy atmosphere, with hill views from the windows.

Felin Fach Griffin, a country pub about a 20-minute drive from Hay, where we booked a table for my birthday lunch. Excellent food and a cosy atmosphere, with hill views from the windows.- Hay Castle, which has had scaffolding up and been half-derelict ever since our first visit in 2004. At various points it has had books for sale. In 2022, it opened to the public as a visitor attraction. A projected animation gives a jaunty historical overview from the Middle Ages to the present day. We especially liked the room of Richard Booth and Book Town memorabilia and the viewing platform at the top. Booth himself was the last to live in the castle. On our earliest trips we would occasionally see him around town – a loud, shuffling (after his stroke) eccentric.

- Hay Distillery, where I had a delicious gin cocktail on my birthday evening.

“It is obviously impossible to catalogue over one million books and these listings therefore represent only a very small selection of the books that we have in stock in Hay. We would point out that one of the chief services of the secondhand bookshop is to provide the customer the opportunity to find the book he did not know existed.”

~Richard Booth, “Books for Sale” periodical (1981?)

“The new book is for the ego; the second-hand book is for the intellect.”

~Richard Booth, quoted on the castle exhibit wall

When we arrived at our Airbnb, we found it had not been cleaned; no linen, etc. A cleaner belatedly came to sort it out, but the owner gave us a full refund, so a minor inconvenience got us back more than enough to pay for the rest of the weekend.

After the final day’s shopping, this was my final book haul. We had particularly good luck in the Addyman’s alleyway, where all books are £1 – we got a bunch for presents (not pictured).

I also opened a first set of birthday books. (My husband and I are having a joint birthday party later this month; I daresay there may be more book parcels to open after.)

Hay is gentrified and hipster now in ways that would probably have Booth turning in his grave. While we slightly miss its dusty, ramshackle past, it’s the new businesses and the Festival that have helped it survive.

If you’ve never been to Hay, I’d certainly recommend it. I possibly slightly prefer Wigtown for its community atmosphere, but it’s more than twice as far away and has fewer book shopping opportunities, which for many of us is the main draw, as well as measly food options. Depending on where you live or are traveling in from, Hay is also likely to be the easiest of the three UK book towns to get to, including by public transport.

Hill keeps the setting deliberately vague, but it seems that it might be the Lincolnshire Fens in the 1930s or so. Arthur Kipps is a young lawyer tasked with attending the funeral of old Mrs Drablow and sorting through her papers. Locals don’t envy him the time spent in Eel Marsh House, and when he starts seeing a wasting-away, smallpox-pocked woman dressed in black in the churchyard, he understands why. This place harbours a malevolent ghost, and from the empty nursery with its creaking rocking chair to the marsh’s treacherous mud, Arthur fears that it’s out to get him.

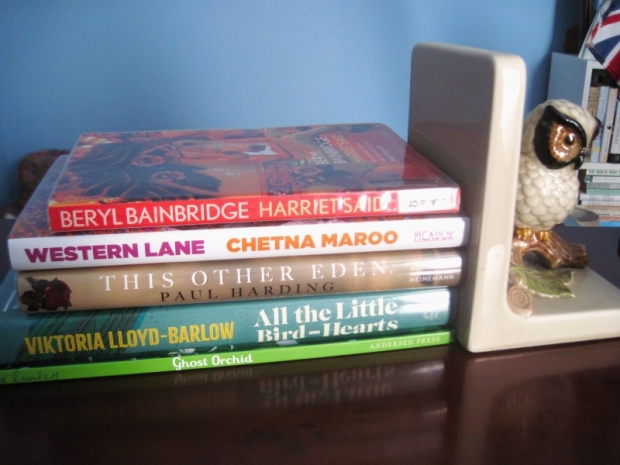

Hill keeps the setting deliberately vague, but it seems that it might be the Lincolnshire Fens in the 1930s or so. Arthur Kipps is a young lawyer tasked with attending the funeral of old Mrs Drablow and sorting through her papers. Locals don’t envy him the time spent in Eel Marsh House, and when he starts seeing a wasting-away, smallpox-pocked woman dressed in black in the churchyard, he understands why. This place harbours a malevolent ghost, and from the empty nursery with its creaking rocking chair to the marsh’s treacherous mud, Arthur fears that it’s out to get him. Although Grainier might appear to be a Job-like figure, his loneliness never shades into despair, lightened by comic dialogues and the mildest of supernatural interventions. He starts a haulage business and keeps dogs. There are rumours of a wolf-girl in the area, and, convinced that his dog’s new pups are part-wolf, he teaches them to howl – his own favourite way of letting off steam.

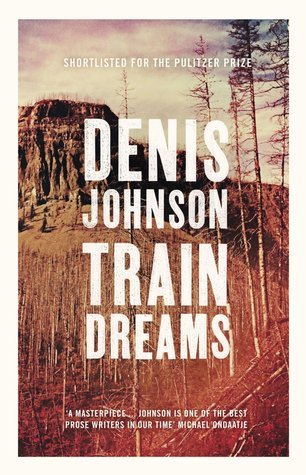

Although Grainier might appear to be a Job-like figure, his loneliness never shades into despair, lightened by comic dialogues and the mildest of supernatural interventions. He starts a haulage business and keeps dogs. There are rumours of a wolf-girl in the area, and, convinced that his dog’s new pups are part-wolf, he teaches them to howl – his own favourite way of letting off steam. – but his new post-school life in Paris doesn’t have room for her. As she moves to London and trains for secretarial work, Marianne is bolstered by friendships with plain-speaking Scot Petronella (“Pet”) and Hugo Forster-Pellisier, her surfing and ping-pong partner on their parents’ Cornwall getaways. Forasmuch as her life changes over the next 15 years or so – taking on a traditional wife and homemaker role; her parents quietly declining – her attachment to her first love never falters.

– but his new post-school life in Paris doesn’t have room for her. As she moves to London and trains for secretarial work, Marianne is bolstered by friendships with plain-speaking Scot Petronella (“Pet”) and Hugo Forster-Pellisier, her surfing and ping-pong partner on their parents’ Cornwall getaways. Forasmuch as her life changes over the next 15 years or so – taking on a traditional wife and homemaker role; her parents quietly declining – her attachment to her first love never falters.

Daniel Clowes is a respected American graphic novelist best known for Ghost World, which was adapted into a 2001 film starring Scarlett Johansson. I’m not sure what I was expecting of Monica. Perhaps something closer to a quiet life story like

Daniel Clowes is a respected American graphic novelist best known for Ghost World, which was adapted into a 2001 film starring Scarlett Johansson. I’m not sure what I was expecting of Monica. Perhaps something closer to a quiet life story like  Ince is not just a speaker at the bookshops but, invariably, a customer – as well as at just about every charity shop in a town. Even when he knows he’ll be carrying his purchases home in his luggage on the train, he can’t resist a browse. And while his shopping basket would look wildly different to mine (his go-to sections are science and philosophy, the occult, 1960s pop and alternative culture; alongside a wide but utterly unpredictable range of classic and contemporary fiction and antiquarian finds), I sensed a kindred spirit in so many lines:

Ince is not just a speaker at the bookshops but, invariably, a customer – as well as at just about every charity shop in a town. Even when he knows he’ll be carrying his purchases home in his luggage on the train, he can’t resist a browse. And while his shopping basket would look wildly different to mine (his go-to sections are science and philosophy, the occult, 1960s pop and alternative culture; alongside a wide but utterly unpredictable range of classic and contemporary fiction and antiquarian finds), I sensed a kindred spirit in so many lines:

I read this over a chilled-out coffee at the Globe bar in Hay-on-Wye (how perfect, then, to come across the lines “I know the secret of life / Is to read good books”). Weatherhead mostly charts the rhythms of everyday existence in pandemic-era New York City, especially through a haiku sequence (“The blind cat asleep / On my lap—and coffee / Just out of reach” – a situation familiar to any cat owner). His style is matter-of-fact and casually funny, juxtaposing random observations about hipster-ish experiences. From “Things the Photoshop Instructor Said and Did”: “Someone gasped when he increased the contrast / I feel like everyone here is named Taylor.”

I read this over a chilled-out coffee at the Globe bar in Hay-on-Wye (how perfect, then, to come across the lines “I know the secret of life / Is to read good books”). Weatherhead mostly charts the rhythms of everyday existence in pandemic-era New York City, especially through a haiku sequence (“The blind cat asleep / On my lap—and coffee / Just out of reach” – a situation familiar to any cat owner). His style is matter-of-fact and casually funny, juxtaposing random observations about hipster-ish experiences. From “Things the Photoshop Instructor Said and Did”: “Someone gasped when he increased the contrast / I feel like everyone here is named Taylor.”

This came highly recommended by

This came highly recommended by  I’m also halfway through High Spirits: A Collection of Ghost Stories (1982) by Robertson Davies and enjoying it immensely. Davies was a Master of Massey College at the University of Toronto. These 18 stories, one for each year of his tenure, were his contribution to the annual Christmas party entertainment. They are short and slightly campy tales told in the first person by an intellectual who definitely doesn’t believe in ghosts – until one is encountered. The spirits are historic royals, politicians, writers or figures from legend. In a pastiche of the classic ghost story à la M.R. James, the pompous speaker is often a scholar of some esoteric field and gives elaborate descriptions. “When Satan Goes Home for Christmas” and “Dickens Digested” are particularly amusing. This will make a perfect bridge between Halloween and Christmas. (National Trust secondhand shop)

I’m also halfway through High Spirits: A Collection of Ghost Stories (1982) by Robertson Davies and enjoying it immensely. Davies was a Master of Massey College at the University of Toronto. These 18 stories, one for each year of his tenure, were his contribution to the annual Christmas party entertainment. They are short and slightly campy tales told in the first person by an intellectual who definitely doesn’t believe in ghosts – until one is encountered. The spirits are historic royals, politicians, writers or figures from legend. In a pastiche of the classic ghost story à la M.R. James, the pompous speaker is often a scholar of some esoteric field and gives elaborate descriptions. “When Satan Goes Home for Christmas” and “Dickens Digested” are particularly amusing. This will make a perfect bridge between Halloween and Christmas. (National Trust secondhand shop)

One of my reads in Hay was this suspenseful novella set in Whitby. Faber was invited by the then artist in residence at Whitby Abbey to write a story inspired by the English Heritage archaeological excavation taking place there in the summer of 2000. His protagonist, Siân, is living in a hotel and working on the dig. She meets Magnus, a handsome doctor, when he comes to exercise the dog he inherited from his late father on the stone steps leading up to the abbey. Siân had been in an accident and is still dealing with the physical and mental after-effects. Each morning she wakes from a nightmare of a man with large hands slitting her throat. When Magnus brings her a centuries-old message in a bottle from his father’s house for her to open and decipher, another layer of intrigue enters: the crumbling document appears to be a murderer’s confession.

One of my reads in Hay was this suspenseful novella set in Whitby. Faber was invited by the then artist in residence at Whitby Abbey to write a story inspired by the English Heritage archaeological excavation taking place there in the summer of 2000. His protagonist, Siân, is living in a hotel and working on the dig. She meets Magnus, a handsome doctor, when he comes to exercise the dog he inherited from his late father on the stone steps leading up to the abbey. Siân had been in an accident and is still dealing with the physical and mental after-effects. Each morning she wakes from a nightmare of a man with large hands slitting her throat. When Magnus brings her a centuries-old message in a bottle from his father’s house for her to open and decipher, another layer of intrigue enters: the crumbling document appears to be a murderer’s confession. Here Green proposes a ghost as a lifelong, visible friend. The book has more words and more advanced ideas than much of what I pick up from the picture book boxes. It’s presented as almost a field guide to understanding the origins and behaviours of ghosts, or maybe a new parent’s or pet owner’s handbook telling how to approach things like baths, bedtime and feeding. What’s unusual about it is that Green takes what’s generally understood as spooky about ghosts and makes it cutesy through faux expert quotes, recipes, etc. She also employs Rowling-esque grossness, e.g. toe jam served on musty biscuits. Perhaps her aim was to tame and thus defang what might make young children afraid. I enjoyed the art more than the sometimes twee words. (Public library)

Here Green proposes a ghost as a lifelong, visible friend. The book has more words and more advanced ideas than much of what I pick up from the picture book boxes. It’s presented as almost a field guide to understanding the origins and behaviours of ghosts, or maybe a new parent’s or pet owner’s handbook telling how to approach things like baths, bedtime and feeding. What’s unusual about it is that Green takes what’s generally understood as spooky about ghosts and makes it cutesy through faux expert quotes, recipes, etc. She also employs Rowling-esque grossness, e.g. toe jam served on musty biscuits. Perhaps her aim was to tame and thus defang what might make young children afraid. I enjoyed the art more than the sometimes twee words. (Public library)

This is the simplest of comics. Sam or “SG” goes around wearing a sheet – a tangible depression they can’t take off. (Again, ghosts aren’t really scary here, just a metaphor for not fully living.) Anxiety about school assignments and lack of friends is nearly overwhelming, but at a party SG notices a kindred spirit also dressed in a sheet: Socks. They’re awkward with each other until they dare to be vulnerable, stop posing as cool, and instead share how much they’re struggling with their mental health. Just to find someone who says “I know exactly what you mean” and can help keep things in perspective is huge. The book ends with SG on a quest to find others in the same situation. The whole thing is in black-and-white and the setups are minimalist (houses, a grocery store, a party, empty streets, a bench in a wooded area where they overlook the town). Not a whole lot of art skill required to illustrate this one, but it’s sweet and well-meaning. I definitely don’t need to read the sequels, though. The tone is similar to the later Heartstopper books and the art is similar to in Sheets and Delicates by Brenna Thummler, all of which are much more accomplished as graphic novels go. (Public library)

This is the simplest of comics. Sam or “SG” goes around wearing a sheet – a tangible depression they can’t take off. (Again, ghosts aren’t really scary here, just a metaphor for not fully living.) Anxiety about school assignments and lack of friends is nearly overwhelming, but at a party SG notices a kindred spirit also dressed in a sheet: Socks. They’re awkward with each other until they dare to be vulnerable, stop posing as cool, and instead share how much they’re struggling with their mental health. Just to find someone who says “I know exactly what you mean” and can help keep things in perspective is huge. The book ends with SG on a quest to find others in the same situation. The whole thing is in black-and-white and the setups are minimalist (houses, a grocery store, a party, empty streets, a bench in a wooded area where they overlook the town). Not a whole lot of art skill required to illustrate this one, but it’s sweet and well-meaning. I definitely don’t need to read the sequels, though. The tone is similar to the later Heartstopper books and the art is similar to in Sheets and Delicates by Brenna Thummler, all of which are much more accomplished as graphic novels go. (Public library)