Love Your Library, June 2023

Thanks, as always, to Elle for her participation, and to Laura and Naomi for their reviews of books borrowed from libraries. Ever since she was our Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shadow panel winner, I’ve followed Julianne Pachico’s blog. A recent post lists books she currently has from the library. I like her comment that borrowing books “is definitely scratching that dopamine itch for me”! On Instagram I spotted this post celebrating both libraries and Pride Month.

And so to my reading and borrowing since last time.

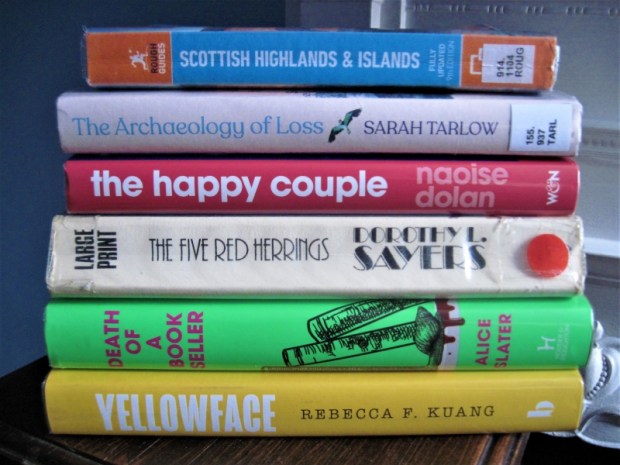

Most of my reservations seemed to come in all at once, right before we left for Scotland, so I’m taking a giant pile along with me (luckily, we’re traveling by car so I don’t have space or weight restrictions) and will see which I can get to, while also fitting in Scotland-themed reads, June review copies, e-books for paid review, and a few of my 20 Books of Summer!

READ

- Rainbow Rainbow: Stories by Lydia Conklin

- The Greengage Summer by Rumer Godden

- Under the Rainbow by Celia Laskey

- Scattered Showers: Stories by Rainbow Rowell

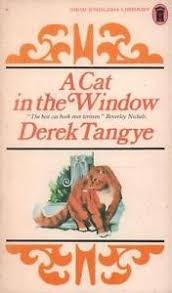

- A Cat in the Window by Derek Tangye

- Cats in Concord by Doreen Tovey

CURRENTLY READING

- The Happy Couple by Naoise Dolan

- The Gifts by Liz Hyder

- Milk by Alice Kinsella

- Yellowface by Rebecca F. Kuang

- Music in the Dark by Sally Magnusson

- Five Red Herrings by Dorothy L. Sayers

- Death of a Bookseller by Alice Slater

- The Archaeology of Loss by Sarah Turlow

- The Legacy of Elizabeth Pringle by Kirsty Wark

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

RETURNED UNREAD

- Pod by Laline Paull – I wanted to give this a try because it made the Women’s Prize shortlist, but I looked at the first few pages and skimmed through the rest and knew I just couldn’t take it seriously. I mean, look at lines like these: “The Rorqual wanted to laugh, but it was serious. The dolphin had been in some physical horror and had lost his mind. Google could not bear his mistake. The sound he raced toward was not Base, but this thing, this creature, he had never before encountered.”

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

Books of Summer, 2: The Story of My Father by Sue Miller

I followed up my third Sue Miller novel, The Lake Shore Limited, with her only work of nonfiction, a short memoir about her father’s decline with Alzheimer’s and eventual death. James Nichols was an ordained minister and church historian who had been a professor or dean at several of the USA’s most elite universities. The first sign that something was wrong was when, one morning in June 1986, she got a call from police in western Massachusetts who had found him wandering around disoriented and knocking at people’s doors at 3 a.m. On the road and in her house after she picked him up, he described vivid visual delusions. He still had the capacity to smile “ruefully” and reply, when Miller explained what had happened and how his experience differed from reality, “Doggone, I never thought I’d lose my mind.”

Until his death five years later, she was the primary person concerned with his wellbeing. She doesn’t say much about her siblings, but there’s a hint of bitterness that the burden fell to her. “Throughout my father’s disease, I struggled with myself to come up with the helpful response, the loving response, the ethical response,” she writes. “I wanted to give him as much of myself as I could. But I also wanted, of course, to have my own life. I wanted, for instance to be able to work productively.” She had only recently found success with fiction in her forties and published two novels before her father died; she dedicated the second to him, but too late for him to understand the honor. Her main comfort was that he never stopped being able to recognize her when she came to visit.

Although the book moves inexorably towards a death, Miller lightens it with many warm and admiring stories from her father’s past. Acknowledging that she’ll never be able to convey the whole of his personality, she still manages to give a clear sense of who he was, and the trajectory of his illness, all within 170 pages. The sudden death of her mother, a flamboyant lyric poet, at age 60 of a heart attack, is a counterbalance as well as a potential contributing factor to his slow fading as each ability was cruelly taken from him: living alone, reading, going outside for walks, sleeping unfettered.

Sutton Hill, the nursing home where he lived out his final years, did not have a dedicated dementia ward, and Miller regrets that he did not receive the specialist care he needed. “I think this is the hardest lesson about Alzheimer’s disease for a caregiver: you can never do enough to make a difference in the course of the disease. Hard because what we feel anyway is that we have never done enough. We blame ourselves. We always find ourselves deficient in devotion.” She conceived of this book as a way of giving her father back his dignity and making a coherent story out of what, while she was living through it, felt like a chaotic disaster. “I would snatch him back from the meaninglessness of Alzheimer’s disease.”

And in the midst of it all, there were still humorous moments. Her poor father fell in love with his private nurse, Marlene, and believed he was married to her. Awful as it was, there was also comedy in an extended family story Miller tells, one I think I’m unlikely to forget: They had always vacationed in New Hampshire rental homes, and when her father learned one of the opulent ‘cottages’ was coming up for sale, he agreed to buy it sight unseen. The seller was a hoarder … of cats. Eighty of them. He had given up cleaning up after them long ago. When they went to view the house her father had already dropped $30,000 on, it was a horror. Every floor was covered inches deep in calcified feces. It took her family an entire summer to clean the place and make it even minimally habitable. Only afterwards could she appreciate the incident as an early sign of her father’s impaired decision making.

I’ve read a fair few dementia-themed memoirs now. As people live longer, this suite of conditions is only going to become more common; if it hasn’t affected one of your own loved ones, you likely have a friend or neighbor who has had it in their family. This reminded me of other clear-eyed, compassionate yet wry accounts I’ve read by daughter-caregivers Elizabeth Hay (All Things Consoled) and Maya Shanbhag Lang (What We Carry). It was just right as a pre-Father’s Day read, and a novelty for fans of Miller’s novels. (Charity shop)

20 Books of Summer, 1: Small Fires by Rebecca May Johnson

So far I’m sticking to my vague plan and reading foodie lit, like it’s 2020 all over again. At the same time, I’m tackling a few books that I received as review copies last year but that have been on my set-aside pile for longer than I’d like to admit. Later in the summer I’ll branch out from the food theme, but always focusing on books I own and have been meaning to read.

Without further ado, my first of 20 Books of Summer:

Small Fires: An Epic in the Kitchen by Rebecca May Johnson (2022)

“I tried to write about cooking, but I wrote a hot red epic.”

Johnson’s debut is a hybrid work, as much a feminist essay collection as it is a memoir about the role that cooking has played in her life. She chooses to interpret apron strings erotically, such that the preparation of meals is not gendered drudgery or oppression but an act of self-care and love for others.

“The kitchen is a space for theorizing!”

While completing a PhD on the reception of The Odyssey and its translation history, Johnson began to think about dishes as translations, or even performances, of a recipe. In two central chapters, “Hot Red Epic” and “Tracing the Sauce Text,” she reckons that she has cooked the same fresh Italian tomato sauce, with nearly infinite small variations, a thousand times over ten years. Where she lived, what she looked like, who she cooked for: so many external details changed, but this most improvisational of dishes stayed the same.

Just a peek at the authors cited in her bibliography – not just the expected subjects like MFK Fisher and Nigella Lawson but also Goethe, Lorde, Plath, Stein, Weil, Winnicott – gives you an idea of how wide-ranging and academically oriented the book is, delving into the psychology of cooking and eating. Oh yes, there will be Freudian sausages. There are also her own recipes, of a sort: one is a personal prose piece (“Bad News Potatoes”) and another is in poetic notation, beginning “I made Mrs Beeton’s / recipe for frying sausages”.

“The recipe is an epic without a hero.”

I particularly enjoyed the essay “Again and Again, There Is That You,” in which Johnson determinedly if chaotically cooks a three-course meal for someone who might be a lover. The mixture of genres and styles is inventive, but a bit strange; my taste would call for more autobiographical material and less theory. The most similar work I’ve read is Recipe by Lynn Z. Bloom, which likewise pulled in some seemingly off-topic strands. I’d be likely to recommend Small Fires to readers of Supper Club.

With thanks to Pushkin Press for the free copy for review.

Introducing the 2023 McKitterick Prize Shortlist

For the second year in a row, I was a first-round judge for the McKitterick Prize (for a first novel by a writer over 40), helping to assess the unpublished manuscripts. Perhaps lockdowns gave people time to achieve a long-held goal of writing a novel, because submissions were up by 50%. None of the manuscripts made it through to the shortlist this year or last, but one day it could happen!

The Society of Authors kindly sent me a parcel with five of the shortlisted novels, and I picked up the remaining one from the library this week. Below are synopses from Goodreads and author bios from the SoA:

The Return of Faraz Ali by Aamina Ahmad (Sceptre): “Sent back to his birthplace—Lahore’s notorious red-light district—to hush up the murder of a girl, a man finds himself in an unexpected reckoning with his past. … Profoundly intimate and propulsive, The Return of Faraz Ali is a spellbindingly assured first novel that poses a timeless question: Whom do we choose to protect, and at what price?”

The Return of Faraz Ali by Aamina Ahmad (Sceptre): “Sent back to his birthplace—Lahore’s notorious red-light district—to hush up the murder of a girl, a man finds himself in an unexpected reckoning with his past. … Profoundly intimate and propulsive, The Return of Faraz Ali is a spellbindingly assured first novel that poses a timeless question: Whom do we choose to protect, and at what price?”

Aamina Ahmad was born and raised in London, where she worked for BBC Drama and other independent television companies as a script editor. Her play The Dishonoured was produced by Kali Theatre Company in 2016. She has an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and is a recipient of a Stegner Fellowship from Stanford University, a Pushcart Prize and a Rona Jaffe Writers Award. Her short fiction has appeared in journals including One Story, the Southern Review and Ecotone. She teaches creative writing at the University of Minnesota.

When We Were Birds by Ayanna Lloyd Banwo (Hamish Hamilton): “Yejide and Darwin will meet inside the gates of Fidelis, Port Angeles’s largest and oldest cemetery, where the dead lie uneasy in their graves and a reckoning with fate beckons them both. A masterwork of lush imagination and immersive lyricism, When We Were Birds is a spellbinding novel about inheritance, loss, and love’s seismic power to heal.”

When We Were Birds by Ayanna Lloyd Banwo (Hamish Hamilton): “Yejide and Darwin will meet inside the gates of Fidelis, Port Angeles’s largest and oldest cemetery, where the dead lie uneasy in their graves and a reckoning with fate beckons them both. A masterwork of lush imagination and immersive lyricism, When We Were Birds is a spellbinding novel about inheritance, loss, and love’s seismic power to heal.”

Ayanna Lloyd Banwo is a writer from Trinidad and Tobago. She is a graduate of the University of the West Indies and holds an MA in Creative Writing from the University of East Anglia, where she is now a Creative and Critical Writing PhD candidate. Her work has been published in Moko Magazine, Small Axe and PREE, among others, and shortlisted for the Small Axe Literary Competition and the Wasafiri New Writing Prize. When We Were Birds, Ayanna’s first novel, was shortlisted for the Jhalak Prize and won the OCM Bocas Prize for Fiction. She is now working on her second novel. Ayanna lives with her husband in London.

The Gifts by Liz Hyder (Manilla Press): “October 1840. A young woman staggers alone through a forest in the English countryside as a huge pair of impossible wings rip themselves from her shoulders. In London, rumours of a “fallen angel” cause a frenzy across the city, and a surgeon desperate for fame and fortune finds himself in the grips of a dangerous obsession. … [A] spellbinding tale told through five different perspectives …, it explores science, nature and religion, enlightenment, the role of women in society and the dark danger of ambition.”

The Gifts by Liz Hyder (Manilla Press): “October 1840. A young woman staggers alone through a forest in the English countryside as a huge pair of impossible wings rip themselves from her shoulders. In London, rumours of a “fallen angel” cause a frenzy across the city, and a surgeon desperate for fame and fortune finds himself in the grips of a dangerous obsession. … [A] spellbinding tale told through five different perspectives …, it explores science, nature and religion, enlightenment, the role of women in society and the dark danger of ambition.”

Liz Hyder has been making up stories for as long she can remember. She has a BA in drama from the University of Bristol and, in early 2018, won the Bridge Award/Moniack Mhor Emerging Writer Award. Bearmouth, her debut young adult novel, won a Waterstones Children’s Book Prize, the Branford Boase Award and was chosen as the Children’s Book of the Year by The Times. Originally from London, she now lives in South Shropshire. The Gifts is her debut adult novel.

Trespasses by Louise Kennedy (Bloomsbury Publishing): “Set in Northern Ireland during the Troubles, a shattering novel about a young woman caught between allegiance to community and a dangerous passion. … As tender as it is unflinching, Trespasses is a heart-pounding, heart-rending drama of thwarted love and irreconcilable loyalties, in a place what you come from seems to count more than what you do, or whom you cherish.”

Trespasses by Louise Kennedy (Bloomsbury Publishing): “Set in Northern Ireland during the Troubles, a shattering novel about a young woman caught between allegiance to community and a dangerous passion. … As tender as it is unflinching, Trespasses is a heart-pounding, heart-rending drama of thwarted love and irreconcilable loyalties, in a place what you come from seems to count more than what you do, or whom you cherish.”

Louise Kennedy grew up a few miles from Belfast. She is the author of the Women’s Prize-shortlisted novel Trespasses, and the acclaimed short story collection The End of the World is a Cul de Sac, and is the only woman to have been shortlisted twice for the Sunday Times Audible Short Story Award (2019 and 2020). Before starting her writing career, she spent nearly thirty years working as a chef. She lives in Sligo.

The Whalebone Theatre by Joanna Quinn (Fig Tree): “One blustery night in 1928, a whale washes up on the shores of the English Channel. By law, it belongs to the King, but twelve-year-old orphan Cristabel Seagrave has other plans. She and the rest of the household … build a theatre from the beast’s skeletal rib cage. … As Cristabel grows into a headstrong young woman, World War II rears its head.”

The Whalebone Theatre by Joanna Quinn (Fig Tree): “One blustery night in 1928, a whale washes up on the shores of the English Channel. By law, it belongs to the King, but twelve-year-old orphan Cristabel Seagrave has other plans. She and the rest of the household … build a theatre from the beast’s skeletal rib cage. … As Cristabel grows into a headstrong young woman, World War II rears its head.”

Joanna Quinn was born in London and grew up in the southwest of England, where her bestselling debut novel, The Whalebone Theatre, is set. Joanna has worked in journalism and the charity sector. She is also a short story writer, published by The White Review and Comma Press, among others. She lives in a village near the sea in Dorset.

Other Names for Love by Taymour Soomro (Harvill Secker): “A seductive coming-of-age story about queer desire, Other Names for Love is a charged, hypnotic debut novel about a boy’s life-changing summer in rural Pakistan: a story of fathers, sons, and the consequences of desire. … Decades later, Fahad is living abroad when he receives a call from his mother summoning him home. … [A] tale of masculinity, inheritance, and desire set against the backdrop of a country’s violent history, told with uncommon urgency and beauty.”

Other Names for Love by Taymour Soomro (Harvill Secker): “A seductive coming-of-age story about queer desire, Other Names for Love is a charged, hypnotic debut novel about a boy’s life-changing summer in rural Pakistan: a story of fathers, sons, and the consequences of desire. … Decades later, Fahad is living abroad when he receives a call from his mother summoning him home. … [A] tale of masculinity, inheritance, and desire set against the backdrop of a country’s violent history, told with uncommon urgency and beauty.”

Taymour Soomro is the author of Other Names for Love and co-editor of Letters to a Writer of Colour. His writing has been published in the New Yorker, the New York Times and elsewhere. He is the recipient of fellowships from the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing, Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and the Sozopol Fiction Seminars. He has degrees from Cambridge University and Stanford Law School and a PhD in creative writing from the University of East Anglia. He currently teaches on the MFA program at Bennington College.

Fellow judge Selma Dabbagh summarises the shortlist thus: “Family estates in rural Pakistan (Other Names for Love) and England (The Whalebone Theatre) fall into decline reflecting the hubris and short-sightedness of their owners[;] in The Return of Faraz Ali, it is the decaying grandeur of the courtesans of Lahore that is lovingly depicted. Whereas in both The Gifts and When We Were Birds, the otherworldly brings new possibilities to the tawdry and impoverished as mystical wings fly over the slums of Victorian London and the graveyards of Trinidad.”

I was already interested in reading a couple of these novels, and was pleased to discover a few new-to-me titles. As it’s also shortlisted for the Women’s Prize (which will be awarded on Wednesday), it seems to make sense to start with Trespasses, and I’m also particularly keen on The Gifts, which sounds like a great holiday read and right up my street, so I’m packing it for our trip to Scotland later this month. One or more of the others might end up on my 20 Books of Summer list. I’ll be sure to follow up with reviews of any I manage to read this summer.

The winner and runner-up will be announced at the SoA Awards ceremony in London on 29 June. I’ll be away at the time but will hope to watch part of the livestream. For more on all of the SoA Awards, see the press release on their website.

See any nominees you’ve read? Who would you like to see win?

Book Serendipity, Mid-April through Early June

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every few months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Fishing with dynamite takes place in Glowing Still by Sara Wheeler and In Memoriam by Alice Winn.

- Egg collecting (illegal!) is observed and/or discussed in Sea Bean by Sally Huband and The Jay, the Beech and the Limpetshell by Richard Smyth.

- Deborah Levy’s Things I Don’t Want to Know is quoted in What I’d Rather Not Think About by Jente Posthuma and Glowing Still by Sara Wheeler. I then bought a secondhand copy of the Levy on my recent trip to the States.

- “Piss-en-lit” and other folk names for dandelions are mentioned in The House of the Interpreter by Lisa Kelly and The Furrows by Namwali Serpell.

- Buttercups and nettles are mentioned in The House of the Interpreter by Lisa Kelly and Springtime in Britain by Edwin Way Teale (and other members of the Ranunculus family, which includes buttercups, in These Envoys of Beauty by Anna Vaught).

- The speaker’s heart is metaphorically described as green in a poem in Lo by Melissa Crowe and The House of the Interpreter by Lisa Kelly.

- Discussion of how an algorithm can know everything about you in Tomb Sweeping by Alexandra Chang and I’m a Fan by Sheena Patel.

- A brother drowns in The Loved Ones: Essays to Bury the Dead by Madison Davis, What I’d Rather Not Think About by Jente Posthuma, and The Furrows by Namwali Serpell.

A few cases of a book recalling a specific detail from an earlier read:

- This metaphor in The Chosen by Elizabeth Lowry links it to The Marriage Portrait by Maggie O’Farrell, another work of historical fiction I’d read not long before: “He has further misgivings about the scalloped gilt bedside table, which wouldn’t look of place in the palazzo of an Italian poisoner.”

- This reference in The Education of Harriet Hatfield by May Sarton links it back to Chase of the Wild Goose by Mary Louisa Gordon (could it be the specific book she had in mind? I suspect it was out of print in 1989, so it’s more likely it was Elizabeth Mavor’s 1971 biography The Ladies of Llangollen): “Do you have a book about those ladies, the eighteenth-century ones, who lived together in some remote place, but everyone knew them?”

- This metaphor in Things My Mother Never Told Me by Blake Morrison links it to The Chosen by Elizabeth Lowry: “Moochingly revisiting old places, I felt like Thomas Hardy in mourning for his wife.”

- A Black family is hounded out of a majority-white area by harassment in The Education of Harriet Hatfield by May Sarton and Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe.

Wartime escapees from prison camps are helped to freedom, including with the help of a German typist, in My Father’s House by Joseph O’Connor and In Memoriam by Alice Winn.

Wartime escapees from prison camps are helped to freedom, including with the help of a German typist, in My Father’s House by Joseph O’Connor and In Memoriam by Alice Winn.

- A scene of eating a deceased relative’s ashes in 19 Claws and a Black Bird by Agustina Bazterrica and The Loved Ones by Madison Davis.

- A girl lives with her flibbertigibbet mother and stern grandmother in “Wife Days,” one story from How Strange a Season by Megan Mayhew Bergman, and Jane of Lantern Hill by L.M. Montgomery.

- Macramé is mentioned in How Strange a Season by Megan Mayhew Bergman, The Memory of Animals by Claire Fuller, Floppy by Alyssa Graybeal, and Sidle Creek by Jolene McIlwain.

- A fascination with fractals in Floppy by Alyssa Graybeal and one story in Sidle Creek by Jolene McIlwain. They are also mentioned in one essay in These Envoys of Beauty by Anna Vaught.

- I found disappointed mentions of the fact that characters wear blackface in Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little Town on the Prairie in Monsters by Claire Dederer and, the very next day, Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe.

- Moon jellyfish are mentioned in the Blood and Cord anthology edited by Abi Curtis, Floppy by Alyssa Graybeal, and Sea Bean by Sally Huband.

- A Black author is grateful to their mother for preparing them for life in a white world in the memoirs-in-essays I Can’t Date Jesus by Michael Arceneaux and Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe.

- The children’s book The Owl Who Was Afraid of the Dark by Jill Tomlinson is mentioned in The Jay, the Beech and the Limpetshell by Richard Smyth and These Envoys of Beauty by Anna Vaught.

- The protagonist’s father brings home a tiger as a pet/object of display in The Marriage Portrait by Maggie O’Farrell and The Memory of Animals by Claire Fuller.

- Bloor Street, Toronto is mentioned in Jane of Lantern Hill by L.M. Montgomery and Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe.

- Ralph Waldo Emerson’s thinking about the stars is quoted in Jane of Lantern Hill by L.M. Montgomery and These Envoys of Beauty by Anna Vaught.

- Wondering whether a marine animal would be better off in captivity, where it could live much longer, in The Memory of Animals by Claire Fuller (an octopus) and Sea Bean by Sally Huband (porpoises).

Martha Gellhorn is mentioned in The Collected Regrets of Clover by Mikki Brammer and Monsters by Claire Dederer.

Martha Gellhorn is mentioned in The Collected Regrets of Clover by Mikki Brammer and Monsters by Claire Dederer.

- Characters named June in “Indigo Run,” the novella-length story in How Strange a Season by Megan Mayhew Bergman, and The Cats We Meet Along the Way by Nadia Mikail.

- “Explicate!” is a catchphrase uttered by a particular character in Girls They Write Songs About by Carlene Bauer and The Lake Shore Limited by Sue Miller.

- It’s mentioned that people used to get dressed up for going on airplanes in Fly Girl by Ann Hood and The Lights by Ben Lerner.

- Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn is a setting in The Lights by Ben Lerner and Grave by Allison C. Meier.

- Last year I read Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin, in which Oregon Trail re-enactors (in a video game) die of dysentery; this is also a live-action plot point in “Pioneers,” one story in Lydia Conklin’s Rainbow Rainbow.

- A bunch (4 or 5) of Italian American sisters in Circling My Mother by Mary Gordon and Hello Beautiful by Ann Napolitano.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Literary Wives Club: The Harpy by Megan Hunter

(My fifth read with the Literary Wives online book club; see also Kay’s and Naomi’s reviews.)

Megan Hunter’s second novella, The Harpy (2020), treads familiar ground – a wife discovers evidence of her husband’s affair and questions everything about their life together – but somehow manages to feel fresh because of the mythological allusions and the hint of how female rage might reverse familial patterns of abuse.

Lucy Stevenson is a mother of two whose husband Jake works at a university. One day she opens a voicemail message on her phone from a David Holmes, saying that he thinks Jake is having an affair with his wife, Vanessa. Lucy vaguely remembers meeting the fiftysomething couple, colleagues of Jake’s, at the Christmas party she hosted the year before.

As further confirmation arrives and Lucy tries to carry on with everyday life (another Christmas party, a pirate-themed birthday party for their younger son), she feels herself transforming into a wrathful, ravenous creature – much like the harpies she was obsessed with as a child and as a Classics student before she gave up on her PhD.

Like the mythical harpy, Lucy administers punishment. At first, it’s something of a joke between her and Jake: he offers that she can ritually harm him three times. Twice it takes physical form; once it’s more about reputational damage. The third time, it goes farther than either of them expected. It’s clever how Hunter presents this formalized violence as an inversion of the domestic abuse of which Lucy’s mother was a victim.

Lucy also expresses anger at how women are objectified, and compares three female generations of her family in terms of how housewifely duties were embraced or rejected. She likens the grief she feels over her crumbling marriage to contractions or menstrual cramps. It’s overall a very female text, in the vein of A Ghost in the Throat. You feel that there’s a solidarity across time and space of wronged women getting their own back. I enjoyed this so much more than Hunter’s debut, The End We Start From. (Birthday gift from my wish list) ![]()

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

“Marriage and motherhood are like death … no one comes back unchanged.”

So much in life can remain unspoken, even in a relationship as intimate as a marriage. What becomes routine can cover over any number of secrets; hurts can be harboured until they fuel revenge. Lucy has lost her separate identity outside of her family relationships and needs to claw back a sense of self.

I don’t know that this book said much that is original about infidelity, but I sympathized with Lucy’s predicament. The literary and magical touches obscure the facts of the ending, so it’s unclear whether she’ll stay with Jake or not. Because we’re mired in her perspective, it’s hard to see Jake or Vanessa clearly. Our only choice is to side with Lucy.

Next book: Sea Wife by Amity Gaige in September

Anthony Bourdain also appeared on my summer reading list when I reviewed

Anthony Bourdain also appeared on my summer reading list when I reviewed  My favorites seem like they could be autobiographical for the author. “The Wall” is narrated by a man who immigrated to Iowa via Berlin at age 10 in the mid-1980s. At a potluck dinner, he met Professor Johannes Weill, who gave him free English lessons. Six years later, he heard of the Berlin Wall coming down and, though he’d lost touch with the professor, made a point of sending a note. The connection across age, race and country is touching. “Sinkholes” is a short, piercing one about the single Black student in a class refusing to be the one to write the N-word on the board during a lesson on Invisible Man. The teacher is trying to make a point about not giving a word power, but it’s clear that it does have significance whether uttered or not. “Swearing In, January 20, 2009” is a poignant flash story about an immigrant’s patriotic delight in Barack Obama’s inauguration, despite prejudice encountered.

My favorites seem like they could be autobiographical for the author. “The Wall” is narrated by a man who immigrated to Iowa via Berlin at age 10 in the mid-1980s. At a potluck dinner, he met Professor Johannes Weill, who gave him free English lessons. Six years later, he heard of the Berlin Wall coming down and, though he’d lost touch with the professor, made a point of sending a note. The connection across age, race and country is touching. “Sinkholes” is a short, piercing one about the single Black student in a class refusing to be the one to write the N-word on the board during a lesson on Invisible Man. The teacher is trying to make a point about not giving a word power, but it’s clear that it does have significance whether uttered or not. “Swearing In, January 20, 2009” is a poignant flash story about an immigrant’s patriotic delight in Barack Obama’s inauguration, despite prejudice encountered.

Just the one cat, actually. (Ripoff!) But Fleabag, a one-eared stray ‘the colour of gone-off curry’ who just won’t leave, is a fine companion on this end-of-the-world Malaysian road trip. Mikail’s debut teen novel, which won the Waterstones Children’s Book Prize 2023, imagines that news has come of an asteroid that will make direct contact with Earth in one year. The clock is ticking; just nine months remain. Teenage Aisha and her boyfriend Walter have come to terms with the fact that they’ll never get to do all the things they want to, from attending university to marrying and having children.

Just the one cat, actually. (Ripoff!) But Fleabag, a one-eared stray ‘the colour of gone-off curry’ who just won’t leave, is a fine companion on this end-of-the-world Malaysian road trip. Mikail’s debut teen novel, which won the Waterstones Children’s Book Prize 2023, imagines that news has come of an asteroid that will make direct contact with Earth in one year. The clock is ticking; just nine months remain. Teenage Aisha and her boyfriend Walter have come to terms with the fact that they’ll never get to do all the things they want to, from attending university to marrying and having children. My second from Tangye. I’ve read from The Minack Chronicles out of order because I happened to find a free copy of

My second from Tangye. I’ve read from The Minack Chronicles out of order because I happened to find a free copy of  My seventh from Tovey. I can hardly believe that, having started her writing career in the 1950s, she was still publishing into the new millennium! (She lived 1918–2008.) Tovey was addicted to Siamese cats. As this volume opens, she’s so forlorn after the death of Saphra, her fourth male, that she instantly sets about finding a replacement. Although she sets strict criteria she doesn’t think can be met, Rama fits the bill and joins her and Tani, her nine-year-old female. They spar at first, but quickly settle into life together. As always, there are various mishaps involving mischievous cats and eccentric locals (I have a really low tolerance for accounts of folksy neighbours’ doings). The most persistent problem is Rama’s new habit of spraying.

My seventh from Tovey. I can hardly believe that, having started her writing career in the 1950s, she was still publishing into the new millennium! (She lived 1918–2008.) Tovey was addicted to Siamese cats. As this volume opens, she’s so forlorn after the death of Saphra, her fourth male, that she instantly sets about finding a replacement. Although she sets strict criteria she doesn’t think can be met, Rama fits the bill and joins her and Tani, her nine-year-old female. They spar at first, but quickly settle into life together. As always, there are various mishaps involving mischievous cats and eccentric locals (I have a really low tolerance for accounts of folksy neighbours’ doings). The most persistent problem is Rama’s new habit of spraying.

Asher and Ivan, two characters of nebulous sexuality and future gender, are the core of “Cheerful Until Next Time” (check out the acronym), which has the fantastic opening line “The queer feminist book club came to an end.” “Laramie Time” stars a lesbian couple debating whether to have a baby (in the comic Leigh draws, a turtle wishes “reproduction was automatic or mandatory, so no decision was necessary”). “A Fearless Moral Inventory” features a pansexual who is a recovering sex addict. Adolescent girls are the focus in “The Black Winter of New England” and “Ooh, the Suburbs,” where they experiment with making lesbian leanings public and seeking older role models. “Pioneer,” probably my second favorite, has Coco pushing against gender constraints at a school Oregon Trail reenactment. Refusing to be a matriarch and not allowed to play a boy, she rebels by dressing up as an ox instead. The tone is often bleak or yearning, so “Counselor of My Heart” stands out as comic even though it opens with the death of a dog; Molly’s haplessness somehow feels excusable.

Asher and Ivan, two characters of nebulous sexuality and future gender, are the core of “Cheerful Until Next Time” (check out the acronym), which has the fantastic opening line “The queer feminist book club came to an end.” “Laramie Time” stars a lesbian couple debating whether to have a baby (in the comic Leigh draws, a turtle wishes “reproduction was automatic or mandatory, so no decision was necessary”). “A Fearless Moral Inventory” features a pansexual who is a recovering sex addict. Adolescent girls are the focus in “The Black Winter of New England” and “Ooh, the Suburbs,” where they experiment with making lesbian leanings public and seeking older role models. “Pioneer,” probably my second favorite, has Coco pushing against gender constraints at a school Oregon Trail reenactment. Refusing to be a matriarch and not allowed to play a boy, she rebels by dressing up as an ox instead. The tone is often bleak or yearning, so “Counselor of My Heart” stands out as comic even though it opens with the death of a dog; Molly’s haplessness somehow feels excusable. Laskey inhabits all 11 personae with equal skill and compassion. Avery, the task force leader’s daughter, resents having to leave L.A. and plots an escape with her new friend Zach, a persecuted gay teen. Christine, a Christian homemaker, is outraged about the liberal agenda, whereas her bereaved neighbor, Linda, finds purpose and understanding in volunteering at the AAA office. Food hygiene inspector Henry is thrown when his wife leaves him for a woman, and meat-packing maven Lizzie agonizes over the question of motherhood. Task force members David, Tegan and Harley all have their reasons for agreeing to the project, but some characters have to sacrifice more than others.

Laskey inhabits all 11 personae with equal skill and compassion. Avery, the task force leader’s daughter, resents having to leave L.A. and plots an escape with her new friend Zach, a persecuted gay teen. Christine, a Christian homemaker, is outraged about the liberal agenda, whereas her bereaved neighbor, Linda, finds purpose and understanding in volunteering at the AAA office. Food hygiene inspector Henry is thrown when his wife leaves him for a woman, and meat-packing maven Lizzie agonizes over the question of motherhood. Task force members David, Tegan and Harley all have their reasons for agreeing to the project, but some characters have to sacrifice more than others. Four of the nine are holiday-themed, so this could make a good Twixtmas read if you like seasonality; eight are in the third person and just one has alternating first person narrators. All are what could be broadly dubbed romances, with most involving meet-cutes or moments when long-time friends realize their feelings go deeper (“Midnights” and “The Snow Ball”). Only one of the pairings is queer, however: Baz and Simon (who are a vampire and … a dragon-man, I think? and the subjects of a trilogy) in the Harry Potter-meets Twilight-meets Heartstopper “Snow for Christmas.” The rest are pretty straightforward boy-girl stories.

Four of the nine are holiday-themed, so this could make a good Twixtmas read if you like seasonality; eight are in the third person and just one has alternating first person narrators. All are what could be broadly dubbed romances, with most involving meet-cutes or moments when long-time friends realize their feelings go deeper (“Midnights” and “The Snow Ball”). Only one of the pairings is queer, however: Baz and Simon (who are a vampire and … a dragon-man, I think? and the subjects of a trilogy) in the Harry Potter-meets Twilight-meets Heartstopper “Snow for Christmas.” The rest are pretty straightforward boy-girl stories.

Berger (1926–2017), an art critic and Booker Prize-winning novelist, spent six weeks shadowing the doctor, to whom he gives the pseudonym John Sassall, with Swiss documentary photographer Jean Mohr, his frequent collaborator. Sassall’s dedication was legendary: he attended every birth in this community, and nearly every death. Sassall’s middle-class origins set him apart from his patients. There’s something condescending about how Berger depicts the locals as simple peasants. Mohr’s photos include soft-focus close-ups on faces exhibiting a sequence of emotions, a technique that feels outdated in the age of video. Along with recording the day-to-day details of medical complaints and interventions, Berger waxes philosophical on topics such as infirmity and vocation. A Fortunate Man is a curious book, part intellectual enquiry and part hagiography.

Berger (1926–2017), an art critic and Booker Prize-winning novelist, spent six weeks shadowing the doctor, to whom he gives the pseudonym John Sassall, with Swiss documentary photographer Jean Mohr, his frequent collaborator. Sassall’s dedication was legendary: he attended every birth in this community, and nearly every death. Sassall’s middle-class origins set him apart from his patients. There’s something condescending about how Berger depicts the locals as simple peasants. Mohr’s photos include soft-focus close-ups on faces exhibiting a sequence of emotions, a technique that feels outdated in the age of video. Along with recording the day-to-day details of medical complaints and interventions, Berger waxes philosophical on topics such as infirmity and vocation. A Fortunate Man is a curious book, part intellectual enquiry and part hagiography.  With its layers of local history and its braided biographical strands, A Fortunate Woman takes up many of the same heavy questions but feels more subtle and timely. It also soon delivers a jolting surprise: the doctor Berger called John Sassall was likely bipolar and, soon after the death of his beloved wife Betty, committed suicide in 1982. His story still haunts this community, where many of the older patients remember going to him for treatment. Like Berger, Morland keenly follows a range of cases. As the book progresses, we see this beautiful valley cycle through the seasons, with certain of Richard Baker’s landscape shots deliberately recreating Mohr’s scene setting. The timing of Morland’s book means that it morphs from a portrait of the quotidian for a doctor and a community to, two-thirds through, an incidental record of the challenges of medical practice during COVID-19.

With its layers of local history and its braided biographical strands, A Fortunate Woman takes up many of the same heavy questions but feels more subtle and timely. It also soon delivers a jolting surprise: the doctor Berger called John Sassall was likely bipolar and, soon after the death of his beloved wife Betty, committed suicide in 1982. His story still haunts this community, where many of the older patients remember going to him for treatment. Like Berger, Morland keenly follows a range of cases. As the book progresses, we see this beautiful valley cycle through the seasons, with certain of Richard Baker’s landscape shots deliberately recreating Mohr’s scene setting. The timing of Morland’s book means that it morphs from a portrait of the quotidian for a doctor and a community to, two-thirds through, an incidental record of the challenges of medical practice during COVID-19.

Galbraith’s is an elegiac tour through imperilled countryside and urban edgelands. Each chapter resembles an in-depth magazine article: a carefully crafted profile of a beloved bird species, with a focus on the specific threats it faces. Galbraith recognises the nuances of land use. However, shooting plays an outsized role. (Curious for his bio not to disclose that he is editor of the Shooting Times.) The title’s reference is to literal birdsong, but the book also celebrates birds’ cultural importance through their place in Britain’s folk music and poetry. He is clearly enamoured of countryside ways, but too often slips into laddishness, with no opportunity missed to mention him or another man having a “piss” outside. Readers could also be forgiven for concluding that “Ilka” (no surname, affiliation or job title), who briefs him on her research into kittiwake populations in Orkney, is the only female working in nature conservation in the entire country; with few exceptions, women only have bit parts: the farm wife making the tea, the receptionist on the phone line, and so on.

Galbraith’s is an elegiac tour through imperilled countryside and urban edgelands. Each chapter resembles an in-depth magazine article: a carefully crafted profile of a beloved bird species, with a focus on the specific threats it faces. Galbraith recognises the nuances of land use. However, shooting plays an outsized role. (Curious for his bio not to disclose that he is editor of the Shooting Times.) The title’s reference is to literal birdsong, but the book also celebrates birds’ cultural importance through their place in Britain’s folk music and poetry. He is clearly enamoured of countryside ways, but too often slips into laddishness, with no opportunity missed to mention him or another man having a “piss” outside. Readers could also be forgiven for concluding that “Ilka” (no surname, affiliation or job title), who briefs him on her research into kittiwake populations in Orkney, is the only female working in nature conservation in the entire country; with few exceptions, women only have bit parts: the farm wife making the tea, the receptionist on the phone line, and so on.  Pavelle’s book is a tonic in more ways than one. Employed by Beaver Trust, she is enthusiastic and self-deprecating. Her nature quest has a broader scope, including insects like the marsh fritillary and marine species such as seagrass and the Atlantic salmon. Travelling between lockdowns in 2020–1, Pavelle took low-carbon transport wherever possible and bolsters her trip accounts with context, much of it gleaned from Zoom calls and e-mail correspondence with experts from museums and universities. Refreshingly, around half of these interviewees are women, and the animal subjects are never the obvious choices. Instead, she seeks out “underdog” species. The explanations are at a suitable level for laymen, true to her job as a science communicator. The snappy, casual prose (“the future of the bilberry bumblebee and its Aperol arse can be bright, but only if we get off our own”) could even endear her to teenage readers. As image goes, Pavelle’s cheerful naïveté holds more charm than Galbraith’s hardboiled masculinity.

Pavelle’s book is a tonic in more ways than one. Employed by Beaver Trust, she is enthusiastic and self-deprecating. Her nature quest has a broader scope, including insects like the marsh fritillary and marine species such as seagrass and the Atlantic salmon. Travelling between lockdowns in 2020–1, Pavelle took low-carbon transport wherever possible and bolsters her trip accounts with context, much of it gleaned from Zoom calls and e-mail correspondence with experts from museums and universities. Refreshingly, around half of these interviewees are women, and the animal subjects are never the obvious choices. Instead, she seeks out “underdog” species. The explanations are at a suitable level for laymen, true to her job as a science communicator. The snappy, casual prose (“the future of the bilberry bumblebee and its Aperol arse can be bright, but only if we get off our own”) could even endear her to teenage readers. As image goes, Pavelle’s cheerful naïveté holds more charm than Galbraith’s hardboiled masculinity.  Taking Flight by Lev Parikian: Parikian’s accessible account of the animal kingdom’s development of flight exhibits a layman’s enthusiasm for an everyday wonder. He explicates the range of flying strategies and the structural adaptations that made them possible. The archaeopteryx section, chronicling the transition between dinosaurs and birds, is a highlight. Though the most science-heavy of the author’s six works, this, perhaps ironically, has fewer footnotes. His usual wit is on display: he describes the feral pigeon as “the Volkswagen Golf of birds” and penguins as “piebald blubber tubes”. This makes it a pleasure to tag along on a journey through evolutionary time, one sure to engage even history- and science-phobes.

Taking Flight by Lev Parikian: Parikian’s accessible account of the animal kingdom’s development of flight exhibits a layman’s enthusiasm for an everyday wonder. He explicates the range of flying strategies and the structural adaptations that made them possible. The archaeopteryx section, chronicling the transition between dinosaurs and birds, is a highlight. Though the most science-heavy of the author’s six works, this, perhaps ironically, has fewer footnotes. His usual wit is on display: he describes the feral pigeon as “the Volkswagen Golf of birds” and penguins as “piebald blubber tubes”. This makes it a pleasure to tag along on a journey through evolutionary time, one sure to engage even history- and science-phobes.