Wise Children by Angela Carter: On the Page and on the Stage

“What a joy it is to dance and sing!”

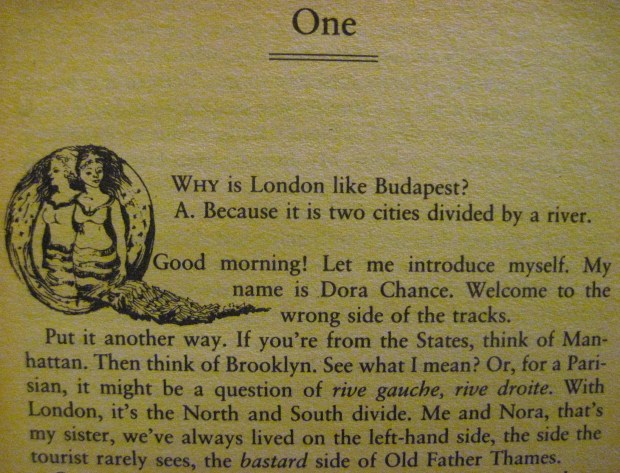

Through a Granta giveaway on Twitter I won two tickets to see Wise Children at London’s Old Vic theatre on October 18th. Clare of A Little Blog of Books joined me for an excellent evening at the theatre, and we both followed it up by reading the novel – Angela Carter’s final book, published in 1991. (Clare’s write-up of the book and play is here.) It has one of the best openers I’ve come across recently:

Twins Nora and Dora Chance turn 75 today; their father, Shakespearean actor Melchior Hazard, who has never publicly acknowledged them because they were born out of wedlock to a servant girl who died in childbirth, turns 100. At the last minute an invitation to his birthday party arrives, and between this point and the party Dora fills us in on the sisters’ knotty family history. Their father is also a twin (though fraternal); his brother Peregrine was more of a father to them than Melchior, with “Grandma” Chance, the owner of the boarding house where they were born, the closest thing they had to a mother growing up. By the time they’re teenagers, the girls are on stage at music halls. After a jaunt to Hollywood to appear in Melchior’s filming of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, they’re back in time for wartime deprivation and tragedy in South London, and decades of shabby nostalgia follow.

It’s a big, bawdy story that has, amazingly, been compressed into just 230 pages. There are five sets of twins in total, with multiple cases of doubling, incest and mistaken identity that would make Shakespeare proud. The novel is composed of five long chapters, like the acts in a play, with a Dramatis Personae on the last two pages (though it might have proven more helpful at the start), and the sisters even live at 49 Bard Road. Dora’s voice is slang-filled and gossipy, and she dutifully presents the sisters’ past as the tragicomedy that it was.

Indeed, Wise Children seems perfect for the stage, and Emma Rice’s production recreates everything that’s best about the book, including Dora’s delightful narration. At the start, resplendent in kimonos and turbans, she and Nora greet us from their Brixton home – represented by a kitschy caravan, which with minor redecoration between scenes serves for all the play’s interiors. The 75-year-olds remain on stage for virtually the entire performance, watching along with the audience from the wings and adding in fragments of commentary, often drawn directly from the text, as scenes from their past unfold (including plenty of simulated sex – I wouldn’t recommend taking along any under-15s).

Androgynous extras cycle into various roles as the action proceeds, with the twins represented first by puppets, then by three sets of actors of various races and genders – the teenage/young adult Nora is played by a Black man, while 75-year-old Dora is a man perhaps of South Asian extraction. This adds extra irony to the humor of one of Nora’s lines: “It’s every woman’s tragedy that, after a certain age, she looks like a female impersonator.” Grandma Chance, with her beehive, cat-eye glasses and nude bodysuit, steals the show, with seaside comedian Gorgeous George coming a close second as the most entertaining character.

The play has cut out most of the 1980s layer of characters and made the story line stronger in doing so. The only other scene I wish could have been included is a farcical multiple wedding ceremony in Hollywood. The glitzy costumes, recurring butterflies, and John Waters-esque tacky-chic of the set all felt true to the atmosphere of the book, and the songs mentioned in the text (such as “I Can’t Give You Anything but Love, Baby”) are supplemented by a couple of numbers that evoke the 1980s setting: “Electric Avenue” and “Girls Just Want to Have Fun.”

This was my fifth book by Carter, and now a joint favorite with The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories – but I liked the play that little bit better. If you get a chance to see it in London or on tour further afield, don’t pass it up. It’s a pure joy.

This was my fifth book by Carter, and now a joint favorite with The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories – but I liked the play that little bit better. If you get a chance to see it in London or on tour further afield, don’t pass it up. It’s a pure joy.

My rating: Book ; Play

; Play

To compare the thoughts of some professional theatregoers and see a few photos, check out the reviews on the Guardian and Telegraph websites.

Second Person Narrative at New Era Theatre

It was a busy weekend for me: we saw Teesside folk duo Megson play at our local arts centre on Friday evening; on Saturday I baked a Dorset apple cake to take down to Hampshire for my father-in-law in advance of his 70th birthday, and in the evening, while my hubby got on with PhD stuff, I went to New Era Theatre, housed in a former chapel in our church carpark, for the first time. It’s a cozy space with only about 50 seats, and I sat on the front row.

The production was called Second Person Narrative, written by Jemma Kennedy and directed by Andy Kempe. Four actresses of different ages play the main character, known only as “You,” at various stages of her life. She’s an Everywoman, completely ordinary but also unique. Short scenes jump ahead three to six years at a time to highlight the big and small events that shape her life. At age 11, she tells the photographer on school picture day that she wants to be an explorer and save animals. At 23, she’s trying to spin her minimal experience into an enticing CV. At 36, she’s disillusioned by her first trip to the rainforest.

The set was a blue rectangular space with an Astroturf floor, hanging clouds covered in timepieces, and a gallery wall at the back where artifacts from You’s life accumulated scene by scene: her stuffed rabbit, a bouquet of flowers, a backpack, a cocktail shaker, and so on. The items are clever reminders of touchpoints from her story, but the wall is depressing: you look at it and wonder, Is that really all that a life adds up to? Occasional music emphasized the theme of time passing, with snippets of “As Time Goes By” and “Time after Time,” and the ending of each scene was signaled by the sound of a camera click.

Supporting characters seemed to serve as commentators on the protagonist’s choices. Her friends, mostly female, were dressed in white, while older males were in gray and played officious roles: her first work supervisor, a persnickety boyfriend who barely noticed when she left him during a trip to Italy, and a trio of men trying to turn her into a TV role model in her twenties or sell her a retirement flat in her seventies. By contrast, You wore red and black. Actresses played multiple roles: You’s mother and Granny from the early years were You in the third and fourth stages of life. This wasn’t just for convenience’s sake; it provides continuity and shows the character coming to resemble the generations of women before her.

Supporting characters seemed to serve as commentators on the protagonist’s choices. Her friends, mostly female, were dressed in white, while older males were in gray and played officious roles: her first work supervisor, a persnickety boyfriend who barely noticed when she left him during a trip to Italy, and a trio of men trying to turn her into a TV role model in her twenties or sell her a retirement flat in her seventies. By contrast, You wore red and black. Actresses played multiple roles: You’s mother and Granny from the early years were You in the third and fourth stages of life. This wasn’t just for convenience’s sake; it provides continuity and shows the character coming to resemble the generations of women before her.

The two most poignant scenes for me were when You is shopping with her mother and the salesgirl assumes the older woman will be in the market for things like a full-length caftan, and when sixtysomething You, having published a poetry collection, has to field inane questions from readers who don’t differentiate between a writer’s biography and art. Other scenes, though, such as You awkwardly flirting in a bar, didn’t add much to the whole.

I did expect the play to make more of the second person perspective. It’s something I find fascinating in books – though it’s often difficult to sustain for any longer than a short story or one chapter. The main character is never addressed by name; others refer to “she” or “her.” On a few occasions other actors come to the edge of the stage and carry on a one-sided dialogue, turning the audience into “You” and letting us fill in for ourselves what she’s saying in reply. What was confusing to me about that was that, as the years passed, the audience wasn’t only taking on the role of You, but her daughter and granddaughter too.

Only once is actual second person narration employed. This is during a nice meta moment when You, now 56, is hosting a book club meeting for friends; the text they’re discussing is Second Person Narration. After an argument with her daughter, she says aloud, “You look at your friends. You feel embarrassed. You pick your black top off the floor and wonder if you can actually still get into it.” One of the friends on stage asks, “Why is she talking like that?”

Overall, I found the production a bit odd and not entirely coherent, but it did succeed in making me think about the expectations placed on a woman’s life – by her family and friends, by society at large, and also by herself. The ending then, I think, specifically invites us to question how things would have gone differently had You been born male.

My rating:

What do you make of second person narration? Do you think you would have enjoyed this play?

The Bookshop Band & The June–July Outlook

The Bookshop Band played in an Oxfordshire village 35 minutes’ drive from us yesterday evening. I’ve now seen them four times; I don’t think that quite qualifies me as a groupie, though I do count them among my favorite artists and own their complete discography.

The small church provided great acoustics and an intimate setting, and the set list was a fun mixture of old and new. All of their songs are based on literature: When they were the house band at Mr B’s Emporium of Reading Delights in Bath, they would write two songs based on an author’s new book on the very day that s/he would be making an appearance at the shop in the evening. A combination of slow reading and procrastination, I suppose. You’d never believe it, though, because their songs are intricate and thoughtful, often pulling out moments and ideas from books (at least the ones I’ve read) that never would have occurred to me.

Here’s what they played last night, and which books the songs were based on:

- “Once Upon a Time” – For a radio commission they crafted this compilation of first lines from various books.

- “Cackling Farts” – A day-in-the-life song featuring archaic vocabulary words from Mark Forsyth’s The Horologicon.

- “You Make the Best Plans, Thomas” – Hilary Mantel’s Bring Up the Bodies (one of my absolute favorites of their songs).

- “Why I Travel This Way” – Yann Martel’s The High Mountains of Portugal (I have heard this live once before, but it’s never been recorded).

“Petroc and the Lights” – Patrick Gale’s Notes from an Exhibition (which reminds me that I really need to read it soon!).

“Petroc and the Lights” – Patrick Gale’s Notes from an Exhibition (which reminds me that I really need to read it soon!).- “Dirty Word” – A brand-new song based on Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World; it stemmed from their recent commission to write about banned books for the V&A.

- “How Not to Woo a Woman” – Rachel Joyce’s The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry (it must be a band favorite as they’ve played it every time I’ve seen them).

- “Curious and Curiouser” – Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland.

- “Sanctuary” – A new song they wrote for the launch event at the Bodleian Library for Philip Pullman’s La Belle Sauvage (The Book of Dust, #1).

- “Room for Three” – The other song they wrote for the Pullman event

- “We Are the Foxes” – Ned Beauman’s Glow.

- “Edge of the World” – Emma Hooper’s Etta and Otto and Russell and James.

- “Faith in Weather” – The only one not based on a book; this was inspired by a Central European folktale about seven ravens (another of my absolute favorites).

- “Thirteen Chairs” – Dave Shelton’s Thirteen Chairs (another one they’ve played every time I’ve seen them).

I’m always impressed by Ben and Beth’s musicianship (guitars, ukuleles, cello, harmonium and more), and I also admire how they’ve continued touring intensively despite being new parents. They’re currently on the road for two months, and one-year-old Molly simply comes along for the ride!

A gorgeous sunset as we left the gig last night.

It’ll be a busy week on the blog. I have posts planned for every day through Saturday thanks to Library Checkout, the Iris Murdoch readalong, and various features reflecting on the first half of the year and looking ahead to the second half.

It turns out I’ll be in America for three weeks of July helping my parents pack and move, so I may have to slow down on the 20 Books of Summer challenge, and will almost certainly have to substitute in some books I have in storage over there. (I’m pondering fiction by Laurie Colwin, Hester Kaplan, Antonya Nelson and Julie Orringer; and nonfiction by Joan Anderson, Haven Kimmel and Sarah Vowell.) I have a few books lined up to review for their July release dates, but it’ll be a light month overall.

The Wellcome Book Prize 2018 Awards Ceremony

Hey, we got it right! Mark O’Connell’s To Be a Machine, our shadow panel’s pick, won the Wellcome Book Prize 2018 last night. Of the three shadow panels I’ve participated in and the many others I’ve observed, this is the only time I remember the shadow winner matching the official one. Clare, Paul and I were there in person for the announcement at the Wellcome Collection in London. When we briefly spoke to the judges’ chair, Edmund de Waal, later in the evening, he said he was “relieved” that their decision matched ours – but I think it was definitely the other way around!

Hey, we got it right! Mark O’Connell’s To Be a Machine, our shadow panel’s pick, won the Wellcome Book Prize 2018 last night. Of the three shadow panels I’ve participated in and the many others I’ve observed, this is the only time I remember the shadow winner matching the official one. Clare, Paul and I were there in person for the announcement at the Wellcome Collection in London. When we briefly spoke to the judges’ chair, Edmund de Waal, later in the evening, he said he was “relieved” that their decision matched ours – but I think it was definitely the other way around!

Simon Chaplin, Director of Culture & Society at the Wellcome Trust, said that each year more and more books are being considered for the prize. De Waal revealed that the judges read 169 books over nine months in what was for him his most frightening book club ever. “To bring the worlds of medicine and health into urgent conversation” requires a “lyrical and disciplined choreography,” he said, and “how we shape stories of science … is crucial.” He characterized the judges’ discussions as both “personal and passionate.” The Wellcome-shortlisted books make a space for public debate, he insisted.

Judges Gordon, Paul-Choudhury, Critchlow, Ratcliffe and de Waal. Photo by Clare Rowland.

The judges brought each of the five authors present onto the stage one at a time for recognition. De Waal praised Ayobami Adebayo’s “narrative of hope and fear and anxiety” and Meredith Wadman’s “beautifully researched and paced thriller.” Dr Hannah Critchlow of Magdalene College, Cambridge called Lindsey Fitzharris’s The Butchering Art “gruesome yet fascinating.” Oxford English professor Sophie Ratcliffe applauded Kathryn Mannix’s book and its mission. New Scientist editor-in-chief Sumit Paul-Choudhury said Mark O’Connell’s book is about the future “just as much as what it means to be human in the twenty-first century.” Journalist and mental health campaigner Bryony Gordon thanked Sigrid Rausing for her “great honesty and stunning prose.”

But there can only be one winner, and it was Mark O’Connell, who couldn’t be there as his wife is/was giving birth to their second child imminently. The general feeling in the room was that he’d made the right call by deciding to stay with his family. He must be feeling like the luckiest man on earth right now, to have a baby plus £30,000! Max Porter, O’Connell’s editor at Granta and the author of Grief Is the Thing with Feathers, received the award on his behalf and read out the extremely witty speech he’d written in advance.

Afterwards we spoke to three of the shortlisted authors. Kathryn Mannix said she’d so enjoyed following our shadow panel reviews and that it was for the best that O’Connell won, as any other outcome might have spoiled the lovely girls’ club the others had going on during the weekend’s events. I got two signatures and we nabbed a quick photo with Lindsey Fitzharris. It was also great to meet Simon Savidge, the king of U.K. book blogging, and author and vlogger Jen Campbell. Other ‘celebrities’ spotted: Sarah Bakewell and Ben Goldacre.

This time I stayed long enough for pudding canapés to come around – raspberry cake pops and mini meringues with strawberries. What a great idea! On the way out I again acquired a Wellcome goody bag: this year’s tote with a copy of The Butchering Art, which I only had on Kindle before. I’d also treated myself to this brainy necklace from the Wellcome shop and wore it to the ceremony. An all-round great evening. I’m looking forward to next year’s prize season already!

Paul, Lindsey Fitzharris, Clare and me.

Wellcome Book Prize Shortlist Event

Five of the six shortlisted authors (barring Dublin-based Mark O’Connell) were at the Wellcome Collection in London yesterday to share more about their books in mini-interviews with Lisa O’Kelly, the associate editor of the Observer. She called each author up onto the stage in turn for a five-minute chat about her work, and then brought them all up for a general conversation and audience questions. Clare and I found it a very interesting afternoon. Here’s some context that I gleaned about the five books and their writers.

Ayobami Adebayo says sickle cell anemia is a massive public health problem in Nigeria, as brought home to her when some friends died of complications of sickle cell. She herself was tested for the gene and learned that she is a carrier, so her children would have a 25% chance of having the disease if her partner was also a carrier. Although life expectancy with the disease has improved to 45–50, a cure is still out of reach for most Nigerians because bone marrow/stem cell transplantation and anti-rejection drugs are so expensive. Compared to the 1980s, when her book opens, she believes polygamy is becoming less fashionable in Nigeria and people are becoming more open to other means of becoming parents, whether IVF or adoption. It’s a way of acknowledging, she says, that parenthood is “not just about biology.”

Ayobami Adebayo says sickle cell anemia is a massive public health problem in Nigeria, as brought home to her when some friends died of complications of sickle cell. She herself was tested for the gene and learned that she is a carrier, so her children would have a 25% chance of having the disease if her partner was also a carrier. Although life expectancy with the disease has improved to 45–50, a cure is still out of reach for most Nigerians because bone marrow/stem cell transplantation and anti-rejection drugs are so expensive. Compared to the 1980s, when her book opens, she believes polygamy is becoming less fashionable in Nigeria and people are becoming more open to other means of becoming parents, whether IVF or adoption. It’s a way of acknowledging, she says, that parenthood is “not just about biology.”

Sigrid Rausing started writing her book soon after her sister-in-law Eva’s body was found: just random paragraphs to make sense of what had happened. From there it became an investigation, a quest to find the nature of addiction. She thinks that as a society we still don’t quite understand what addiction is, and the medical research and public perception are very separate. In addition to nature and nurture, she thinks we should consider the influence of culture – as an anthropologist by training, she’s very interested in drug culture and how that drew in her brother, Hans. Although there have been many memoirs by ex-addicts, she can’t think of another one by a family member. Perhaps, she suggested, this is because the addict is seen as the ultimate victim. She referred to her book as a “collage,” a very apt description.

Kathryn Mannix spoke of how her grandmother, born in 1900, saw so much more death than we do nowadays: siblings, a child, and so on. Today, though, Mannix has encountered people in their sixties who are facing, with their parents, their very first deaths. Death is fairly “gentle” and “dull” if you’re not directly involved, she insists; she blames Hollywood and Eastenders for showing unusually dramatic deaths. She said once you understand what exactly people are afraid of about dying (e.g. hell, oblivion, pain, leaving their families behind) you can address their specific concerns and thereby “beat out the demon of terror and fear.” Mannix never intended to write a book, but someone heard her on the radio and invited her to do so. Luckily, from her medical school days onward, she’d been writing an A4 page about each of her most mind-boggling cases to get them out of her head and move on. That’s why, as O’Kelly put it, the characters in her 30 stories “leap off the page.”

Mannix, Adebayo, O’Kelly, Rausing, Wadman & Fitzharris

Lindsey Fitzharris called The Butchering Art “a love story between science and medicine” – it was the first time that the former (antisepsis) was applied to the latter. She initially thought Robert Liston was her man – he was so colorful, larger than life – but eventually found that the real story was with Joseph Lister, the quiet, persistent Quaker. (However, the book does open with Liston performing the first surgery under ether.) Fitzharris is also involved in the Order of the Good Death, author Caitlin Doughty’s initiative, and affirmed Mannix’s efforts to remove the taboo from talking about death. I think I heard correctly that she said there is a film of The Butchering Art in the works?! I’ll need to look into that some more.

Meredith Wadman started with a brief explanation of how immunization works and why the 1960s were ripe for vaccine research. This segment went really science-y, which I thought was a little unfortunate as it may have made listeners tune out and be less interested in her work than the others’. It was perhaps inevitable given her subject matter, but also a matter of the questions O’Kelly asked – with the others she focused more on stories and themes than on scientific facts. It was interesting to hear what Wadman has been working on recently: for the past 6–8 months, she’s been reporting for Science on sexual harassment in science. For her next book, though, she’s pondering the conflict between a congressman and a Centers for Disease Control scientist over funding into research that might lead to gun control.

The question time brought up the issues of medical misinformation online, the distrust people with chronic illnesses have of medical professionals, and euthanasia – Mannix rather dodged that one, stating that her book is about the natural dying process so that’s not really her area. (Though it does come up in a chapter of her book.) We also heard a bit about the projects up next for each author. Rausing’s next book will be a travel memoir about the Capetown drought, taking in apartheid and her husband’s family’s immigration. Adebayo is at work on a very nebulous novel “about people,” and possibly how privilege affects access to healthcare.

Meeting Mrs. Malaprop

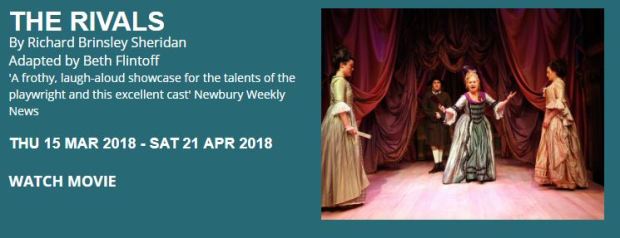

I’d been aware for perhaps a few years that malapropisms are named after a character who’s prone to verbal gaffes. Last night I met Mrs. Malaprop herself at a performance of Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s The Rivals (1775) at nearby Watermill Theatre. This was our second trip to the Watermill, after The Picture of Dorian Gray last September. It’s a small and intimate venue and the production was somewhat in the round, so we were in a row to the left-hand side of the stage. It felt like we were right inside the action, though occasionally one actor would block another such that we couldn’t see the looks passing between them.

It was a small cast of eight actors, four of whom did double duty as servants. We meet two young couples—Lydia Languish and Captain Jack Absolute, with whom she’s fallen in love while he’s in disguise as penniless “Ensign Beverley” – they plan to elope; and Julia Melville and Faulkland, who saved her from drowning and has been her betrothed for years—along with two guardian figures, Sir Anthony Absolute and Mrs. Malaprop, and two hapless suitors played for laughs, country bumpkin Bob Acres and over-the-top-Irish Sir Lucius O’Trigger. The characters’ paths cross in amusing ways while they are all in Bath.

One of the key words in the play is “caprice” – a term you don’t encounter so often these days. (The adjectival form, capricious, is common enough, but I can’t remember the last time I saw the noun.) Several of the characters could be described as capricious, but especially Faulkland, who torments Julia with his doubts about the constancy of her love, and Lydia, who rather loses interest in Captain Jack once she realizes that their guardians approve of their match and she won’t have to undertake a romantic elopement instead.

What with the disguises, misunderstandings, and general farcical atmosphere, The Rivals is reminiscent of a Shakespearean comedy, though the language is easier to follow. Here in Beth Flintoff’s adaptation, much of the humor comes through in accents and exaggerated facial expressions, though Sir Anthony’s growled insults to his son and Bob Acres’ attempts to pass himself off as a gentleman are also highlights. The whole cast (see this full list) was terrific, including several actors familiar from British television and bit parts in films.

And, of course, there’s Mrs. Malaprop and her wondrous malapropisms. Sheridan would have taken her name from malapropos, a synonym for “inappropriate” first recorded in 1630, and an adaptation of the French term mal à propos (“poorly placed”). The first recorded use of “malaprop” for the wrong use of words was by Lord Byron in 1814. Some of the malapropisms in the play fell flat because both the spoken and intended words are too obscure nowadays. I think the director probably left out certain ones, and added at least one anachronistically modern one: “calamari” for calamity. But there were still some excellent ones. Here are a few of my favorites (see also this complete list):

“promise to forget this fellow – to illiterate him, I say, quite from your memory.”

“He is the very pine-apple of politeness!”

“she’s as headstrong as an allegory on the banks of the Nile.”

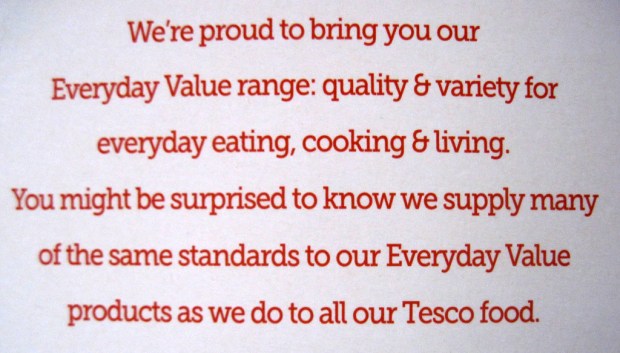

[I even spotted a malapropism (can I use that term for written rather than spoken words?) on my cornflakes box this morning:

Do you spot it too?]

Great acting, costumes and hairstyles; laughs aplenty; and a rhyming prologue and epilogue that made reference to the modern day (“I’m not going to hex it with jokes about … anything unpleasant!” and “eat less baked beans and drink more champagne”): Altogether a splendid evening out at the theatre.

My rating:

#1: I fully expect Richard Powers to win for The Overstory. This is the one I’m partway through; I started reading a library copy on Friday. I’m so impressed by the novel’s expansive nature. It seems to have everything: love, war, history, nature, politics, technology, small-town life, family drama, illness, accidents, death. And all of human life is overshadowed and put into perspective by the ancientness of trees, whose power we disregard at a cost. I’m reminded of the work of Jonathan Franzen (Freedom + Purity), as well as Barbara Kingsolver’s latest, Unsheltered – though Powers is prophetic where she’s polemic.

#1: I fully expect Richard Powers to win for The Overstory. This is the one I’m partway through; I started reading a library copy on Friday. I’m so impressed by the novel’s expansive nature. It seems to have everything: love, war, history, nature, politics, technology, small-town life, family drama, illness, accidents, death. And all of human life is overshadowed and put into perspective by the ancientness of trees, whose power we disregard at a cost. I’m reminded of the work of Jonathan Franzen (Freedom + Purity), as well as Barbara Kingsolver’s latest, Unsheltered – though Powers is prophetic where she’s polemic. #2: Washington Black by Esi Edugyan is a good old-fashioned adventure story about a slave who gets the chance to leave his Barbados sugar plantation behind when he becomes an assistant to an abolitionist inventor, Christopher “Titch” Wilde. Wash discovers a talent for drawing and a love for marine life and pursues these joint interests in the disparate places where life takes him. Part One was much my favorite; none of what followed quite matched it in depth or pace. Still, I enjoyed following along on Wash’s escapades, and I wouldn’t mind seeing this take the prize – it would be great to see a woman of color win.

#2: Washington Black by Esi Edugyan is a good old-fashioned adventure story about a slave who gets the chance to leave his Barbados sugar plantation behind when he becomes an assistant to an abolitionist inventor, Christopher “Titch” Wilde. Wash discovers a talent for drawing and a love for marine life and pursues these joint interests in the disparate places where life takes him. Part One was much my favorite; none of what followed quite matched it in depth or pace. Still, I enjoyed following along on Wash’s escapades, and I wouldn’t mind seeing this take the prize – it would be great to see a woman of color win.  #3: The Mars Room by Rachel Kushner: Kushner is well respected, though I’ve failed to get on with her fiction before. An inside look at the prison system, this could be sufficiently weighty and well-timed to win.

#3: The Mars Room by Rachel Kushner: Kushner is well respected, though I’ve failed to get on with her fiction before. An inside look at the prison system, this could be sufficiently weighty and well-timed to win. #4: Everything Under by Daisy Johnson: A myth-infused debut novel about a mother and daughter. On my library stack to read next, and the remaining title from the shortlist I’m most keen to read.

#4: Everything Under by Daisy Johnson: A myth-infused debut novel about a mother and daughter. On my library stack to read next, and the remaining title from the shortlist I’m most keen to read. #5: The Long Take by Robin Robertson: A novel, largely in verse, about the aftermath of war service. Also on my library stack. Somewhat experimental forms like this grab Booker attention, but this might be too under-the-radar to win.

#5: The Long Take by Robin Robertson: A novel, largely in verse, about the aftermath of war service. Also on my library stack. Somewhat experimental forms like this grab Booker attention, but this might be too under-the-radar to win. #6: Milkman by Anna Burns: Set in Belfast during the Troubles or a dystopian future? From my Goodreads friends’ reviews this sounds wooden and overwritten. Like the Kushner, I’d consider reading it if it wins but probably not otherwise.

#6: Milkman by Anna Burns: Set in Belfast during the Troubles or a dystopian future? From my Goodreads friends’ reviews this sounds wooden and overwritten. Like the Kushner, I’d consider reading it if it wins but probably not otherwise.

It was my first time reading the famous “The Garden Party,” which likewise moves from a blithe holiday mood into something weightier. The Sheridans are making preparations for a lavish garden party dripping with flowers and food. Daughter Laura is dismayed when news comes that a man from the cottages has been thrown from his horse and killed, and thinks they should cancel the event. Everyone tells her not to be silly; of course it will go on as planned. The story ends when, after visiting his widow to hand over leftover party food, she unwittingly sees the man’s body and experiences an epiphany about the simultaneous beauty and terror of life. “Don’t cry,” her brother says. “Was it awful?” “No,” she replies. “It was simply marvellous.” Mansfield is especially good at first and last paragraphs. I’ll read more by her someday.

It was my first time reading the famous “The Garden Party,” which likewise moves from a blithe holiday mood into something weightier. The Sheridans are making preparations for a lavish garden party dripping with flowers and food. Daughter Laura is dismayed when news comes that a man from the cottages has been thrown from his horse and killed, and thinks they should cancel the event. Everyone tells her not to be silly; of course it will go on as planned. The story ends when, after visiting his widow to hand over leftover party food, she unwittingly sees the man’s body and experiences an epiphany about the simultaneous beauty and terror of life. “Don’t cry,” her brother says. “Was it awful?” “No,” she replies. “It was simply marvellous.” Mansfield is especially good at first and last paragraphs. I’ll read more by her someday.

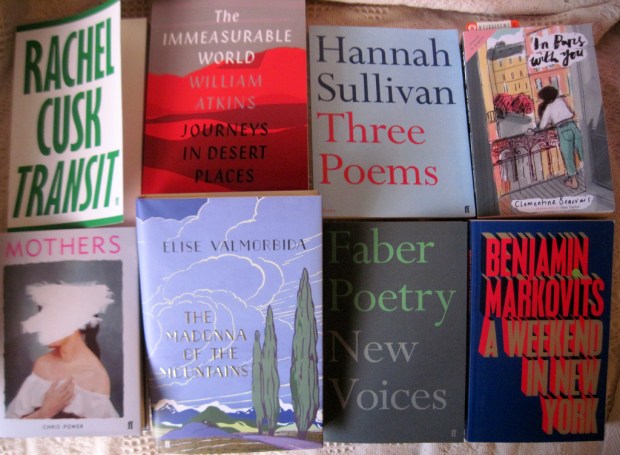

I’ve never been to an event quite like this. Publisher Faber & Faber, which will be celebrating its 90th birthday in 2019, previewed its major releases through to September. Most of the attendees seemed to be booksellers and publishing insiders. Drinks were on a buffet table at the back; books were on a buffet table along the side. Glass of champagne in hand, it was time to plunder the free books on offer. I ended up taking one of everything, with the exception of Rachel Cusk’s trilogy: I couldn’t make it through Outline and am not keen enough on her writing to get an advanced copy of Kudos, but figured I might give her another try with the middle book, Transit.

I’ve never been to an event quite like this. Publisher Faber & Faber, which will be celebrating its 90th birthday in 2019, previewed its major releases through to September. Most of the attendees seemed to be booksellers and publishing insiders. Drinks were on a buffet table at the back; books were on a buffet table along the side. Glass of champagne in hand, it was time to plunder the free books on offer. I ended up taking one of everything, with the exception of Rachel Cusk’s trilogy: I couldn’t make it through Outline and am not keen enough on her writing to get an advanced copy of Kudos, but figured I might give her another try with the middle book, Transit.

The two main characters Mears keeps coming back to in the course of the play are Bert Brocklesby, a Yorkshire preacher, and philosopher Bertrand Russell. Brocklesby refused to fight and, when he and other COs were shipped off to France anyway, resisted doing any work that supported the war effort, even peeling the potatoes that would be fed to soldiers. He and his fellow COs were beaten, placed in solitary confinement, and threatened with execution. Meanwhile, Russell and others in the No-Conscription Fellowship fought for their rights back in London. There’s a wonderful scene in the play where Russell, clad in nothing but a towel after a skinny dip, pleads with Prime Minister Asquith.

The two main characters Mears keeps coming back to in the course of the play are Bert Brocklesby, a Yorkshire preacher, and philosopher Bertrand Russell. Brocklesby refused to fight and, when he and other COs were shipped off to France anyway, resisted doing any work that supported the war effort, even peeling the potatoes that would be fed to soldiers. He and his fellow COs were beaten, placed in solitary confinement, and threatened with execution. Meanwhile, Russell and others in the No-Conscription Fellowship fought for their rights back in London. There’s a wonderful scene in the play where Russell, clad in nothing but a towel after a skinny dip, pleads with Prime Minister Asquith.