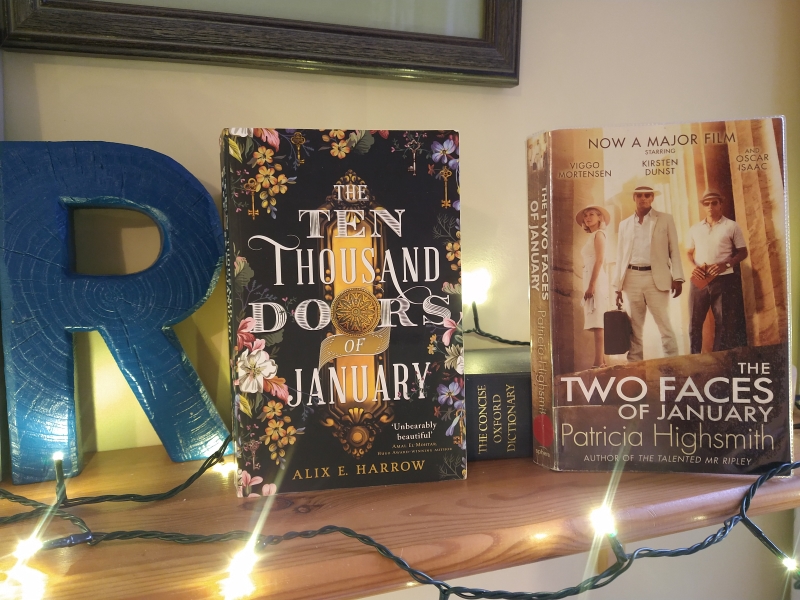

January Novels by Alix E. Harrow & Patricia Highsmith

The month of January was named for the Roman god Janus, known for having two faces: one looking backward, the other forward. “He presided not over one particular domain but over the places between – past and present, here and there, endings and beginnings,” as Alix E. Harrow writes. In her novel, the door is a prevailing metaphor for liminal times and spaces; Highsmith’s work, too, focuses on the way life often pivots on tiny accidents or decisions.

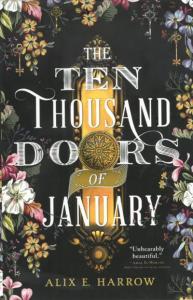

The Ten Thousand Doors of January by Alix E. Harrow (2019)

“I didn’t want to be safe … I wanted to be dangerous, to find my own power and write it on the world.”

As the mixed-race ward of a wealthy collector, January Scaller grows up in a Vermont mansion with a dual sense of privilege and loss. She barely sees her brown-skinned father, who travels the world amassing treasures for Mr. Locke and his archaeological society; and her mother’s absence is an unexplained heartbreak. But when her father also disappears in 1911 – to be apparently replaced by an African governess named Jane Irimu (it’s her quote above) and an enticing scholarly manuscript entitled The Ten Thousand Doors – 17-year-old January discovers the power of words to literally open doors to new worlds, and sets off on a quest to reunite her family. At every turn, though, she’s thwarted by evil white men who, after plundering foreign cultures, intend to close the doors of opportunity behind them.

As the mixed-race ward of a wealthy collector, January Scaller grows up in a Vermont mansion with a dual sense of privilege and loss. She barely sees her brown-skinned father, who travels the world amassing treasures for Mr. Locke and his archaeological society; and her mother’s absence is an unexplained heartbreak. But when her father also disappears in 1911 – to be apparently replaced by an African governess named Jane Irimu (it’s her quote above) and an enticing scholarly manuscript entitled The Ten Thousand Doors – 17-year-old January discovers the power of words to literally open doors to new worlds, and sets off on a quest to reunite her family. At every turn, though, she’s thwarted by evil white men who, after plundering foreign cultures, intend to close the doors of opportunity behind them.

This was an unlikely book for me to pick up: I didn’t get on with that whole wave of books with books and keys on the cover (Bridget Collins et al.) and wouldn’t willingly pick up romantasy – yet this features two meant-to-be romances fought for across worlds and eras. I grow impatient with a book-within-the-book format. But The Chronicles of Narnia, which no doubt inspired Harrow, were my favourite books as a child. Especially early on, I found this as thrilling as The Absolute Book and The End of Mr. Y. Whereas those doorstoppers held my interest all the way through, though, this became a trudge at a certain point. Harrow is maybe a little too pleased with her own imagination and turns of phrase, like T. Kingfisher. (Bad the dog is also in peril far too often.) In the end, this reminded me most of Babel by R.F. Kuang with its postcolonial conscience and words as power. I enjoyed this enough that I think I’ll propose her The Once and Future Witches for book club. (Little Free Library) ![]()

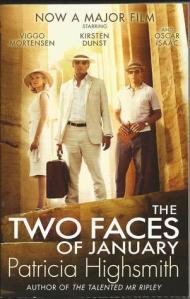

The Two Faces of January by Patricia Highsmith (1964)

Three American vacationers meet in a hotel in Greece one January. But the circumstances are far from auspicious. Conman Chester MacFarland is traveling with his 15-years-younger wife, Colette. Rydal Keener is a stranger who, seemingly on a whim, helps them cover up the accidental death of a Greek police investigator who came to ask Chester some questions. From here on in, they’re in lockstep, moving around Greece together, obtaining fake passports and checking the headlines obsessively to outrun consequences. Colette takes a fancy to Rydal, and the jealousy emanating from the love triangle is complicated by Chester’s alcoholism and Rydal’s hurt over earning a police record for a consensual teenage relationship. I have a dim memory of seeing the 2014 Kirsten Dunst and Viggo Mortensen film, but luckily I didn’t recall any major events. A climactic scene takes place at the palace of Knossos, and the chase continues until an unavoidably tragic end.

Three American vacationers meet in a hotel in Greece one January. But the circumstances are far from auspicious. Conman Chester MacFarland is traveling with his 15-years-younger wife, Colette. Rydal Keener is a stranger who, seemingly on a whim, helps them cover up the accidental death of a Greek police investigator who came to ask Chester some questions. From here on in, they’re in lockstep, moving around Greece together, obtaining fake passports and checking the headlines obsessively to outrun consequences. Colette takes a fancy to Rydal, and the jealousy emanating from the love triangle is complicated by Chester’s alcoholism and Rydal’s hurt over earning a police record for a consensual teenage relationship. I have a dim memory of seeing the 2014 Kirsten Dunst and Viggo Mortensen film, but luckily I didn’t recall any major events. A climactic scene takes place at the palace of Knossos, and the chase continues until an unavoidably tragic end.

I’ve read several Ripley novels and a few standalone psychological mysteries by Highsmith and enjoyed them well enough, but murders aren’t really my thing. (Carol is the only work of hers that I’ve truly loved.) My specific issue here was with the central trio of characters. Colette is thinly drawn and doesn’t get enough time on the page. Chester seems much older than his 42 years and is an irredeemable swindler. It’s only because of our fondness for Rydal that we want them all to get away with it. But even Rydal doesn’t get the in-depth portrayal one might hope for. There’s the injustice of his backstory and the fact that he’s a would-be poet, true, but we never understand why he helped the MacFarlands, so have to conclude that it was the impulse of a moment and committed him to a regrettable course. This is pacey enough to keep the pages turning, but won’t stick with me. (Public library) ![]()

I’m turning my face forward: Good riddance to January 2026, during which I’ve mostly felt rubbish; here’s hoping for a better rest of the year. I’m off to the opera tonight – something I’ve only done once before, in Leeds in 2006! – to see Susannah, a tale from the Apocrypha transplanted to the 1950s U.S. South.

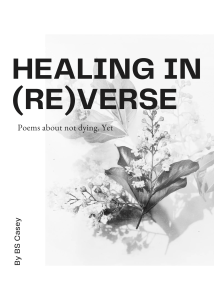

Healing in (Re)Verse: Poems about not dying. Yet by BS Casey (Blog Tour)

Bee Casey’s self-published debut collection contains a hard-hitting set of accessible poems arising from the conjunction of mental health crisis and disability. It opens with the sense of a golden era never to be regained: “the girl before / commanded the room // Oh how I wish I could even walk into it now.” Now the body brings only “pain and cruelty”: “an unwelcome guest / lingers on my chest / in bones and my home”.

Bee Casey’s self-published debut collection contains a hard-hitting set of accessible poems arising from the conjunction of mental health crisis and disability. It opens with the sense of a golden era never to be regained: “the girl before / commanded the room // Oh how I wish I could even walk into it now.” Now the body brings only “pain and cruelty”: “an unwelcome guest / lingers on my chest / in bones and my home”.

End rhymes, slant rhymes, and alliteration form part of the sonic palette. Through imagined conversations with the self and with others who have hurt the speaker or put them down, they wrestle with concepts of forgiveness and self-love. “Just a girl” chronicles instances of sexualized verbal and emotional abuse. The use of repeated words and phrases, with minor adaptations, along with the themes of trauma and recovery, reminded me of Rupi Kaur’s performance poetry-inspired style. “Monster” is more like a short story with its prose paragraphs and imagined dialogue. “How are you” is an erasure poem that crosses out all the possible genuine answers to that question in between, leaving only the socially acceptable “I’m fine thanks. … how are you?”

The pages’ stark black-and-white design is softened by background images of flowers, feathers, forests, candle flames, and shadows falling through windows. Although the tone is overwhelmingly sad, there is also some wry humour, as in the below.

Casey has only just turned 30, and it’s sobering to think how much they’ve gone through in that short time and how often suicide has been a temptation. It’s a relief to see that their view of life has shifted from it being a trial to a gift. “What an honour, a privilege / What beauty to grow old.” Sometimes for them, not dying has to be an active decision, as in the poem “Tomorrow I will kill myself,” but the habit can stick – for 15 years “I’ve been too busy / Accidentally being alive.”

Casey has only just turned 30, and it’s sobering to think how much they’ve gone through in that short time and how often suicide has been a temptation. It’s a relief to see that their view of life has shifted from it being a trial to a gift. “What an honour, a privilege / What beauty to grow old.” Sometimes for them, not dying has to be an active decision, as in the poem “Tomorrow I will kill myself,” but the habit can stick – for 15 years “I’ve been too busy / Accidentally being alive.”

Poetry – writing it or reading it – can be a great way for people to work through the pain of mental ill health and chronic illness and not feel so alone. That’s one reason I’m looking forward to the return of the Barbellion Prize later this year. “The Barbellion Prize celebrates and promotes writing that represents the experience of chronic illness and disability. The prize is named after the diarist W.N.P. Barbellion, who wrote eloquently on his life with multiple sclerosis (MS). It is a cross-genre award for literature published in the English language.” I’ve donated to get it up and running again; maybe you can, too?

My thanks to Random Things Tours and the author for the advanced e-copy for review.

See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will be appearing soon.

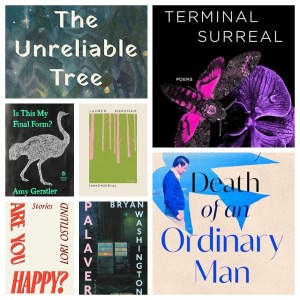

The 2026 Releases I’ve Read So Far

I happen to have read a number of pre-release books, generally for paid reviews for Foreword and Shelf Awareness. (I already previewed six upcoming novellas here.) Most of my reviews haven’t been published yet, so I’ll just give brief excerpts and ratings here to pique the interest. I link to the few that have been published already, then list the 2026 books I’m currently reading. Soon I’ll follow up with a list of my Most Anticipated titles.

Simple Heart by Cho Haejin (trans. from Korean by Jamie Chang) [Other Press, Feb. 3]: A transnational adoptee returns to Korea to investigate her roots through a documentary film. A poignant novel that explores questions of abandonment and belonging through stories of motherhood.

Simple Heart by Cho Haejin (trans. from Korean by Jamie Chang) [Other Press, Feb. 3]: A transnational adoptee returns to Korea to investigate her roots through a documentary film. A poignant novel that explores questions of abandonment and belonging through stories of motherhood. ![]()

The Conspiracists: Women, Extremism, and the Lure of Belonging by Noelle Cook [Broadleaf Books, Jan. 6]: An in-depth, empathetic study of “conspirituality” (a philosophy that blends conspiracy theories and New Age beliefs), filtered through the outlook of two women involved in storming the Capitol on January 6, 2021.

The Conspiracists: Women, Extremism, and the Lure of Belonging by Noelle Cook [Broadleaf Books, Jan. 6]: An in-depth, empathetic study of “conspirituality” (a philosophy that blends conspiracy theories and New Age beliefs), filtered through the outlook of two women involved in storming the Capitol on January 6, 2021. ![]()

The Reservation by Rebecca Kauffman [Counterpoint, Feb. 24]: The staff members of a fine-dining restaurant each have a moment in the spotlight during the investigation of a theft. Linked short stories depict character interactions and backstories with aplomb. Big-hearted; for J. Ryan Stradal fans.

The Reservation by Rebecca Kauffman [Counterpoint, Feb. 24]: The staff members of a fine-dining restaurant each have a moment in the spotlight during the investigation of a theft. Linked short stories depict character interactions and backstories with aplomb. Big-hearted; for J. Ryan Stradal fans. ![]()

Taking Flight by Kashmira Sheth (illus. Nicolo Carozzi) [Dial Press, April 21]: A touching story of the journeys of three refugee children who might be from Tibet, Syria and Ukraine. The drawing style reminded me of Chris Van Allsburg’s. This left a tear in my eye.

Taking Flight by Kashmira Sheth (illus. Nicolo Carozzi) [Dial Press, April 21]: A touching story of the journeys of three refugee children who might be from Tibet, Syria and Ukraine. The drawing style reminded me of Chris Van Allsburg’s. This left a tear in my eye. ![]()

Currently reading:

(Blurb excerpts from Goodreads; all are e-copies apart from Evensong)

Visitations: Poems by Julia Alvarez [Knopf, April 7]: “Alvarez traces her life [via] memories of her childhood in the Dominican Republic … and the sisters who forged her, her move to America …, the search for mental health and beauty, redemption, and success.”

Visitations: Poems by Julia Alvarez [Knopf, April 7]: “Alvarez traces her life [via] memories of her childhood in the Dominican Republic … and the sisters who forged her, her move to America …, the search for mental health and beauty, redemption, and success.”

Our Numbered Bones by Katya Balen [Canongate, 12 Feb. / HarperVia, Feb. 17]: Her “adult debut [is] about a grieving author who heads to rural England for a writer’s retreat, only to stumble upon an incredible historical find” – a bog body!

Our Numbered Bones by Katya Balen [Canongate, 12 Feb. / HarperVia, Feb. 17]: Her “adult debut [is] about a grieving author who heads to rural England for a writer’s retreat, only to stumble upon an incredible historical find” – a bog body!

Let’s Make Cocktails!: A Comic Book Cocktail Book by Sarah Becan [Ten Speed Press, April 7]: “With vivid, easy-to-follow graphics, Becan guides readers through basic techniques such as shaking, stirring, muddling, and more. With all recipes organized by spirit for easy access, readers will delight in the panelized step-by-step comic instructions.”

Let’s Make Cocktails!: A Comic Book Cocktail Book by Sarah Becan [Ten Speed Press, April 7]: “With vivid, easy-to-follow graphics, Becan guides readers through basic techniques such as shaking, stirring, muddling, and more. With all recipes organized by spirit for easy access, readers will delight in the panelized step-by-step comic instructions.”

Monsters in the Archives: My Year of Fear with Stephen King by Caroline Bicks [Hogarth/Hodder & Stoughton, April 21]: “A fascinating, first of its kind exploration of Stephen King and his … iconic early books, based on … research and interviews with King … conducted by the first scholar … given … access to his private archives.”

Monsters in the Archives: My Year of Fear with Stephen King by Caroline Bicks [Hogarth/Hodder & Stoughton, April 21]: “A fascinating, first of its kind exploration of Stephen King and his … iconic early books, based on … research and interviews with King … conducted by the first scholar … given … access to his private archives.”

Men I Hate: A Memoir in Essays by Lynette D’Amico [Mad Creek Books, Feb. 17]: “Can a lesbian who loves a trans man still call herself a lesbian? As D’Amico tries to engage more deeply with the man she is married to, she looks at all the men—historical figures, politicians, men in her family—in search of clear dividing lines”.

Men I Hate: A Memoir in Essays by Lynette D’Amico [Mad Creek Books, Feb. 17]: “Can a lesbian who loves a trans man still call herself a lesbian? As D’Amico tries to engage more deeply with the man she is married to, she looks at all the men—historical figures, politicians, men in her family—in search of clear dividing lines”.

See One, Do One, Teach One: The Art of Becoming a Doctor: A Graphic Memoir by Grace Farris [W. W. Norton & Company, March 24]: “In her graphic memoir debut, Grace looks back on her journey through medical school and residency.”

See One, Do One, Teach One: The Art of Becoming a Doctor: A Graphic Memoir by Grace Farris [W. W. Norton & Company, March 24]: “In her graphic memoir debut, Grace looks back on her journey through medical school and residency.”

Nighthawks by Lisa Martin [University of Alberta Press, April 2]: “These poems parse aspects of human embodiment—emotion, relationship, mortality—and reflect on how to live through moments of intense personal and political upheaval.”

Nighthawks by Lisa Martin [University of Alberta Press, April 2]: “These poems parse aspects of human embodiment—emotion, relationship, mortality—and reflect on how to live through moments of intense personal and political upheaval.”

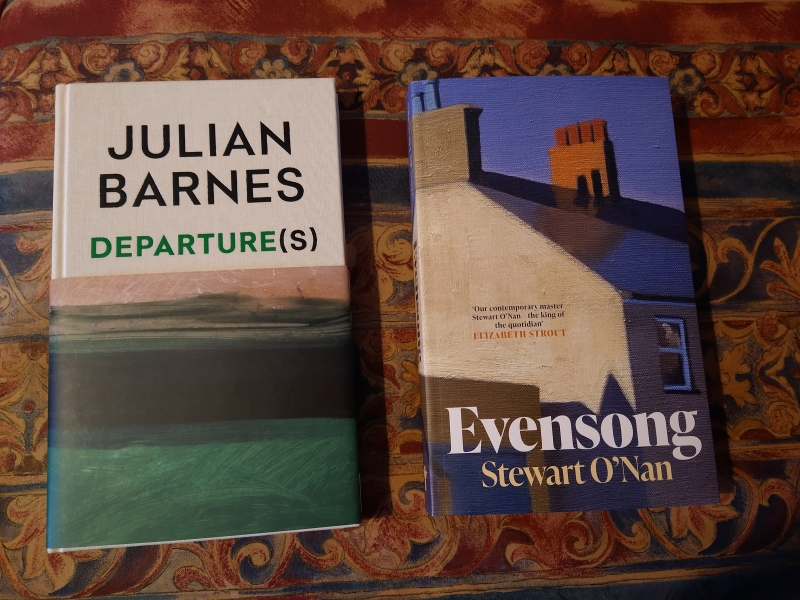

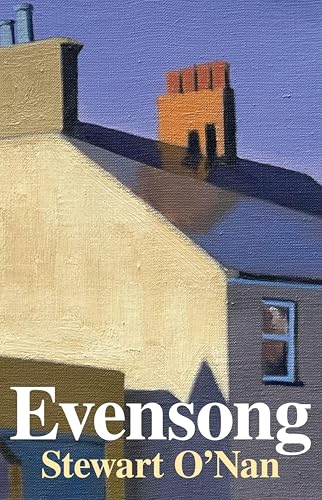

Evensong by Stewart O’Nan [published in USA in November 2025; Grove Press UK, 1 Jan.]: “An intimate, moving novel that follows The Humpty Dumpty Club, a group of women of a certain age who band together to help one another and their circle of friends in Pittsburgh.”

Evensong by Stewart O’Nan [published in USA in November 2025; Grove Press UK, 1 Jan.]: “An intimate, moving novel that follows The Humpty Dumpty Club, a group of women of a certain age who band together to help one another and their circle of friends in Pittsburgh.”

This Is the Door: The Body, Pain, and Faith by Darcey Steinke [HarperOne, Feb. 24]: “In chapters that trace the body—The Spine, The Heart, The Knees, and more—[Steinke] introduces sufferers to new and ancient understandings of pain through history, philosophy, religion, pop culture, and reported human experience.”

This Is the Door: The Body, Pain, and Faith by Darcey Steinke [HarperOne, Feb. 24]: “In chapters that trace the body—The Spine, The Heart, The Knees, and more—[Steinke] introduces sufferers to new and ancient understandings of pain through history, philosophy, religion, pop culture, and reported human experience.”

American Fantasy by Emma Straub [Riverhead, April 7 / Michael Joseph (Penguin), 14 May]: “When the American Fantasy cruise ship sets sail for a four-day themed voyage, aboard are all five members of a famous 1990s boyband, and three thousand screaming women who have worshipped them for thirty years.”

American Fantasy by Emma Straub [Riverhead, April 7 / Michael Joseph (Penguin), 14 May]: “When the American Fantasy cruise ship sets sail for a four-day themed voyage, aboard are all five members of a famous 1990s boyband, and three thousand screaming women who have worshipped them for thirty years.”

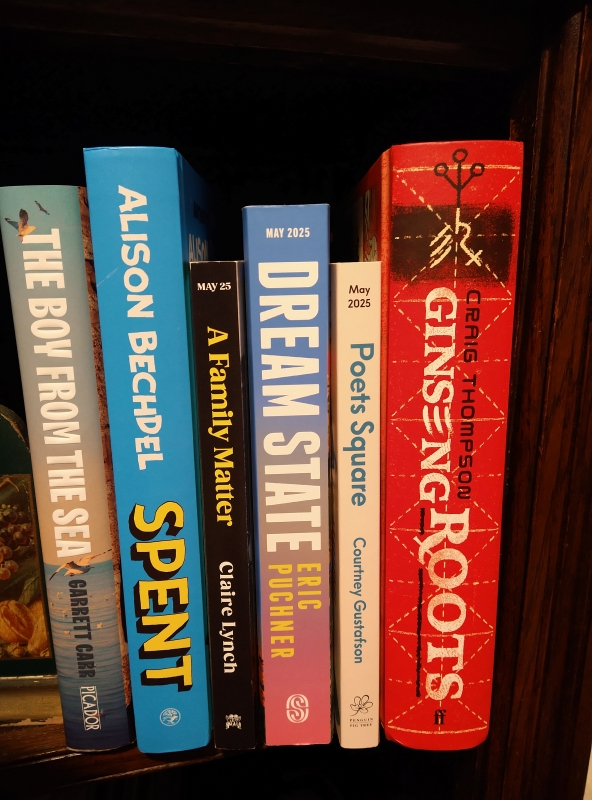

Additional pre-release review books on my shelf:

Shooting Up by Jonathan Tepper [Constable, 19 Feb.]: “Born into a family of American missionaries driven by unwavering faith … Jonathan’s home became a sanctuary for society’s most broken … AIDS hit Spain a few years after it exploded in New York and, like an invisible plague, … claimed countless lives – including those … in the family rehabilitation centre.”

Shooting Up by Jonathan Tepper [Constable, 19 Feb.]: “Born into a family of American missionaries driven by unwavering faith … Jonathan’s home became a sanctuary for society’s most broken … AIDS hit Spain a few years after it exploded in New York and, like an invisible plague, … claimed countless lives – including those … in the family rehabilitation centre.”

Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael [Salt Publishing, 9 Feb.]: “Based on the real correspondence between Elizabeth Gaskell and Charles Dickens … [Gaskell] visits a young Irish prostitute in Manchester’s New Bailey prison. … [A] story of hypocrisy and suppression, and how Elizabeth navigates the … prejudice of the day to help the young girl”.

Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael [Salt Publishing, 9 Feb.]: “Based on the real correspondence between Elizabeth Gaskell and Charles Dickens … [Gaskell] visits a young Irish prostitute in Manchester’s New Bailey prison. … [A] story of hypocrisy and suppression, and how Elizabeth navigates the … prejudice of the day to help the young girl”.

Will you look out for one or more of these?

Any other 2026 reads you can recommend?

Best Books of 2025: The Runners-Up

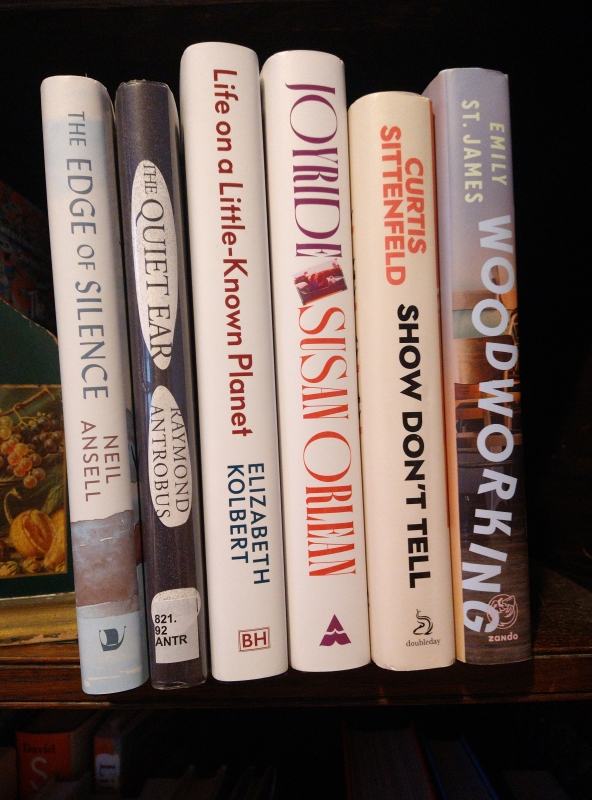

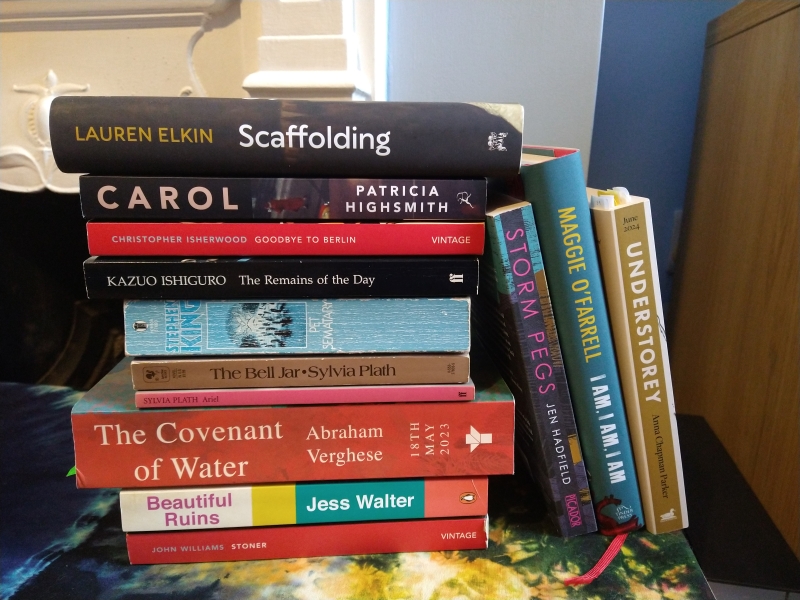

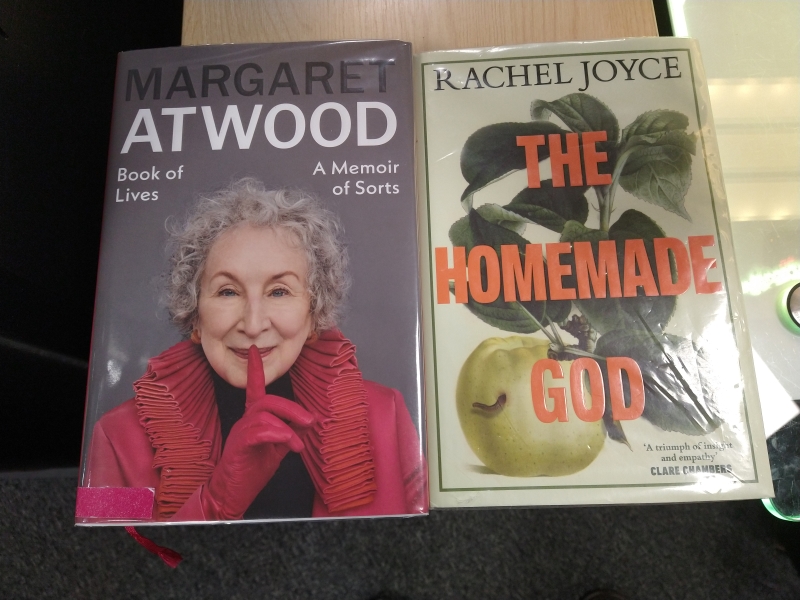

Coming up tomorrow: my list of the 15 best 2025 releases I’ve read. Here are 15 more that nearly made the cut. Pictured below are the ones I read / could get my hands on in print; the rest were e-copies or in-demand library books. Links are to my full reviews where available.

Fiction

Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven: A glistening portrait of a lovably dysfunctional California family beset by losses through the years but expanded through serendipity and friendship. Life changes forever for the Samuelsons (architect dad Phil; mom Sibyl, a fourth-grade teacher; three kids) when the eldest son, Ellis, moves into a hippie commune in the Santa Cruz Mountains. A rotating close third-person perspective spotlights each member. Fans of Jami Attenberg, Ann Patchett, and Anne Tyler need to try Huneven’s work pronto.

Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven: A glistening portrait of a lovably dysfunctional California family beset by losses through the years but expanded through serendipity and friendship. Life changes forever for the Samuelsons (architect dad Phil; mom Sibyl, a fourth-grade teacher; three kids) when the eldest son, Ellis, moves into a hippie commune in the Santa Cruz Mountains. A rotating close third-person perspective spotlights each member. Fans of Jami Attenberg, Ann Patchett, and Anne Tyler need to try Huneven’s work pronto.

Sleep by Honor Jones: A breathtaking character study of a woman raising young daughters and facing memories of childhood abuse. Margaret’s 1990s New Jersey upbringing seems idyllic, but upper-middle-class suburbia conceals the perils of a dysfunctional family headed by a narcissistic, controlling mother. Jones crafts unforgettable, crystalline scenes. There are subtle echoes throughout as the past threatens to repeat. Reminiscent of Sarah Moss and Evie Wyld, and astonishing for its psychological acuity, this promises great things from Jones.

Sleep by Honor Jones: A breathtaking character study of a woman raising young daughters and facing memories of childhood abuse. Margaret’s 1990s New Jersey upbringing seems idyllic, but upper-middle-class suburbia conceals the perils of a dysfunctional family headed by a narcissistic, controlling mother. Jones crafts unforgettable, crystalline scenes. There are subtle echoes throughout as the past threatens to repeat. Reminiscent of Sarah Moss and Evie Wyld, and astonishing for its psychological acuity, this promises great things from Jones.

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing: Steeped in the homosexual demimonde of 1970s Italian cinema (Fellini and Pasolini films), with a clear antifascist message filtered through the coming-of-age story of a young Englishman trying to outrun his past. This offers the best of both worlds: the verisimilitude of true crime reportage and the intimacy of the close third person. Laing leavens the tone with some darkly comedic moments. Elegant and psychologically astute work from one of the most valuable cultural commentators out there.

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing: Steeped in the homosexual demimonde of 1970s Italian cinema (Fellini and Pasolini films), with a clear antifascist message filtered through the coming-of-age story of a young Englishman trying to outrun his past. This offers the best of both worlds: the verisimilitude of true crime reportage and the intimacy of the close third person. Laing leavens the tone with some darkly comedic moments. Elegant and psychologically astute work from one of the most valuable cultural commentators out there.

The Eights by Joanna Miller: Highly readable, book club-suitable fiction that is a sort of cross between In Memoriam and A Single Thread in terms of its subject matter: the first women to attend Oxford in the 1920s, the suffrage movement, and the plight of spare women after WWI. Different aspects are illuminated by the four central friends and their milieu. This debut has a good sense of place and reasonably strong characters. Despite some difficult subject matter, it remains resolutely jolly.

The Eights by Joanna Miller: Highly readable, book club-suitable fiction that is a sort of cross between In Memoriam and A Single Thread in terms of its subject matter: the first women to attend Oxford in the 1920s, the suffrage movement, and the plight of spare women after WWI. Different aspects are illuminated by the four central friends and their milieu. This debut has a good sense of place and reasonably strong characters. Despite some difficult subject matter, it remains resolutely jolly.

Endling by Maria Reva: What is worth doing, or writing about, in a time of war? That is the central question here, yet Reva brings considerable lightness to a novel also concerned with environmental devastation and existential loneliness. Yeva, a snail researcher in Ukraine, is contemplating suicide when Nastia and Sol rope her into a plot to kidnap 12 bride-seeking Western bachelors. The faux endings and re-dos are faltering attempts to find meaning when everything is breaking down. Both great fun to read and profound on many matters.

Endling by Maria Reva: What is worth doing, or writing about, in a time of war? That is the central question here, yet Reva brings considerable lightness to a novel also concerned with environmental devastation and existential loneliness. Yeva, a snail researcher in Ukraine, is contemplating suicide when Nastia and Sol rope her into a plot to kidnap 12 bride-seeking Western bachelors. The faux endings and re-dos are faltering attempts to find meaning when everything is breaking down. Both great fun to read and profound on many matters.

Show Don’t Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld: Sittenfeld’s second collection features characters negotiating principles and privilege in midlife. Split equally between first- and third-person perspectives, the 12 contemporary storylines spotlight everyday marital and parenting challenges. Dual timelines offer opportunities for hindsight on the events of decades ago. Nostalgic yet clear-eyed, these witty stories exploring how decisions determine the future are perfect for fans of Rebecca Makkai, Kiley Reid, and Emma Straub.

Show Don’t Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld: Sittenfeld’s second collection features characters negotiating principles and privilege in midlife. Split equally between first- and third-person perspectives, the 12 contemporary storylines spotlight everyday marital and parenting challenges. Dual timelines offer opportunities for hindsight on the events of decades ago. Nostalgic yet clear-eyed, these witty stories exploring how decisions determine the future are perfect for fans of Rebecca Makkai, Kiley Reid, and Emma Straub.

Woodworking by Emily St. James: When 35-year-old English teacher Erica realizes that not only is there another trans woman in her small South Dakota town but that it’s one of her students, she lights up. Abigail may be half her age but is further along in her transition journey and has sassy confidence. But this foul-mouthed mentor has problems of her own, starting with parents who refuse to refer to her by her chosen name. This was pure page-turning enjoyment with an important message, reminiscent of Celia Laskey and Tom Perrotta.

Woodworking by Emily St. James: When 35-year-old English teacher Erica realizes that not only is there another trans woman in her small South Dakota town but that it’s one of her students, she lights up. Abigail may be half her age but is further along in her transition journey and has sassy confidence. But this foul-mouthed mentor has problems of her own, starting with parents who refuse to refer to her by her chosen name. This was pure page-turning enjoyment with an important message, reminiscent of Celia Laskey and Tom Perrotta.

Flesh by David Szalay: Szalay explores modes of masculinity and channels, by turns, Hemingway; Fitzgerald and St. Aubyn; Hardy and McEwan. Unprocessed trauma plays out in Istvan’s life as violence against himself and others as he moves between England and Hungary and sabotages many of his relationships. He comes to know every sphere from prison to the army to the jet set. The flat affect and sparse style make this incredibly readable: a book for our times and all times and thus a worthy Booker Prize winner.

Flesh by David Szalay: Szalay explores modes of masculinity and channels, by turns, Hemingway; Fitzgerald and St. Aubyn; Hardy and McEwan. Unprocessed trauma plays out in Istvan’s life as violence against himself and others as he moves between England and Hungary and sabotages many of his relationships. He comes to know every sphere from prison to the army to the jet set. The flat affect and sparse style make this incredibly readable: a book for our times and all times and thus a worthy Booker Prize winner.

Nonfiction

The Edge of Silence: In Search of the Disappearing Sounds of Nature by Neil Ansell: I owe this a full review. I’ve read all five of Ansell’s books and consider him one of the UK’s top nature writers. Here he draws lovely parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis we face because of climate breakdown. The world is going silent for him, but rare species may well become silenced altogether. His defiant, low-carbon adventures on the fringes offer one last chance to hear some of the UK’s beloved species, mostly seabirds.

The Edge of Silence: In Search of the Disappearing Sounds of Nature by Neil Ansell: I owe this a full review. I’ve read all five of Ansell’s books and consider him one of the UK’s top nature writers. Here he draws lovely parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis we face because of climate breakdown. The world is going silent for him, but rare species may well become silenced altogether. His defiant, low-carbon adventures on the fringes offer one last chance to hear some of the UK’s beloved species, mostly seabirds.

The Quiet Ear: An Investigation of Missing Sound by Raymond Antrobus: (Another memoir about being hard of hearing!) Antrobus’s first work of nonfiction takes up the themes of his poetry – being deaf and mixed-race, losing his father, becoming a parent – and threads them into an outstanding memoir that integrates his disability and celebrates his role models. This frank, fluid memoir of finding one’s way as a poet illuminates the literal and metaphorical meanings of sound. It offers an invaluable window onto intersectional challenges.

The Quiet Ear: An Investigation of Missing Sound by Raymond Antrobus: (Another memoir about being hard of hearing!) Antrobus’s first work of nonfiction takes up the themes of his poetry – being deaf and mixed-race, losing his father, becoming a parent – and threads them into an outstanding memoir that integrates his disability and celebrates his role models. This frank, fluid memoir of finding one’s way as a poet illuminates the literal and metaphorical meanings of sound. It offers an invaluable window onto intersectional challenges.

Bigger: Essays by Ren Cedar Fuller: Fuller’s perceptive debut work offers nine linked autobiographical essays in which she seeks to see herself and family members more clearly by acknowledging disability (her Sjögren’s syndrome), neurodivergence (she theorizes that her late father was on the autism spectrum), and gender diversity (her child, Indigo, came out as transgender and nonbinary; and she realizes that three other family members are gender-nonconforming). This openhearted memoir models how to explore one’s family history.

Bigger: Essays by Ren Cedar Fuller: Fuller’s perceptive debut work offers nine linked autobiographical essays in which she seeks to see herself and family members more clearly by acknowledging disability (her Sjögren’s syndrome), neurodivergence (she theorizes that her late father was on the autism spectrum), and gender diversity (her child, Indigo, came out as transgender and nonbinary; and she realizes that three other family members are gender-nonconforming). This openhearted memoir models how to explore one’s family history.

Life on a Little-Known Planet: Dispatches from a Changing World by Elizabeth Kolbert: These exceptional essays encourage appreciation of natural wonders and technological advances but also raise the alarm over unfolding climate disasters. There are travelogues and profiles, too. Most pieces were published in The New Yorker, whose generous article length allows for robust blends of research, on-the-ground experience, interviews, and in-depth discussion of controversial issues. (Review pending for the Times Literary Supplement.)

Life on a Little-Known Planet: Dispatches from a Changing World by Elizabeth Kolbert: These exceptional essays encourage appreciation of natural wonders and technological advances but also raise the alarm over unfolding climate disasters. There are travelogues and profiles, too. Most pieces were published in The New Yorker, whose generous article length allows for robust blends of research, on-the-ground experience, interviews, and in-depth discussion of controversial issues. (Review pending for the Times Literary Supplement.)

Joyride by Susan Orlean: Another one I need to review in the new year. As a long-time staff writer for The New Yorker (like Kolbert!), Orlean has had the good fortune to be able to follow her curiosity wherever it leads, chasing the subjects that interest her and drawing readers in with her infectious enthusiasm. She gives behind-the-scenes information on lots of her early stories and on each of her books. The Orchid Thief and the movie not-exactly-based on it, Adaptation, are among my favourites, so the long section on them was a thrill for me.

Joyride by Susan Orlean: Another one I need to review in the new year. As a long-time staff writer for The New Yorker (like Kolbert!), Orlean has had the good fortune to be able to follow her curiosity wherever it leads, chasing the subjects that interest her and drawing readers in with her infectious enthusiasm. She gives behind-the-scenes information on lots of her early stories and on each of her books. The Orchid Thief and the movie not-exactly-based on it, Adaptation, are among my favourites, so the long section on them was a thrill for me.

What Sheep Think About the Weather: How to Listen to What Animals Are Trying to Say by Amelia Thomas: A comprehensive yet conversational book that effortlessly illuminates the possibilities of human–animal communication. Rooted on her Nova Scotia farm but ranging widely through research, travel, and interviews, Thomas learned all she could from scientists, trainers, and animal communicators. Full of fascinating facts wittily conveyed, this elucidates science and nurtures empathy. (I interviewed the author, too.)

What Sheep Think About the Weather: How to Listen to What Animals Are Trying to Say by Amelia Thomas: A comprehensive yet conversational book that effortlessly illuminates the possibilities of human–animal communication. Rooted on her Nova Scotia farm but ranging widely through research, travel, and interviews, Thomas learned all she could from scientists, trainers, and animal communicators. Full of fascinating facts wittily conveyed, this elucidates science and nurtures empathy. (I interviewed the author, too.)

Poetry

Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung: Cheung is both a physician and a poet. Her debut collection is a lucid reckoning with everything that could and does go wrong, globally and individually. Intimate, often firsthand knowledge of human tragedies infuses the verse with melancholy honesty. Scientific vocabulary abounds here, with history providing perspective on current events. Ghazals with repeating end words reinforce the themes. These remarkable poems gild adversity with compassion and model vigilance during uncertainty.

Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung: Cheung is both a physician and a poet. Her debut collection is a lucid reckoning with everything that could and does go wrong, globally and individually. Intimate, often firsthand knowledge of human tragedies infuses the verse with melancholy honesty. Scientific vocabulary abounds here, with history providing perspective on current events. Ghazals with repeating end words reinforce the themes. These remarkable poems gild adversity with compassion and model vigilance during uncertainty.

Last Love Your Library of 2025 & Another for #DoorstoppersInDecember

Thanks to Eleanor, Margaret and Skai for writing about their recent library reading! Marcie also joined in with a post about completing Toronto Public Library’s 2025 Reading Challenge with books by Indigenous authors.

I managed to fit in a few more 2025 releases before Christmas. My plan for January is to focus on reading from my own shelves (which includes McKitterick Prize submissions and perhaps also review copies to catch up on), so expect next month to be a lighter one.

My recent reading has featured many mentions of how much libraries mean, particularly to young women.

In her autobiographical poetry collection Visitations (coming out in April), Julia Alvarez writes of how her family’s world changed when they moved to New York City from the Dominican Republic in the 1960s. “Waiting for My Father to Pick Me Up at the Library” adopts the tropes of Alice in Wonderland: as her future expands, her father’s life shrinks.

In her autobiographical poetry collection Visitations (coming out in April), Julia Alvarez writes of how her family’s world changed when they moved to New York City from the Dominican Republic in the 1960s. “Waiting for My Father to Pick Me Up at the Library” adopts the tropes of Alice in Wonderland: as her future expands, her father’s life shrinks.

In The Mercy Step by Marcia Hutchinson, the public library is a haven for Mercy, growing up in Bradford in the 1960s. She can hardly believe it’s free for everyone to use, even Black people. Greek mythology is her escape from an upbringing that involves domestic violence and molestation. “It’s peaceful and quiet in the Library. No one shouts or throws things or hits anyone. If anyone talks, the Librarian puts a finger to her mouth and tells them to shush.”

In The Mercy Step by Marcia Hutchinson, the public library is a haven for Mercy, growing up in Bradford in the 1960s. She can hardly believe it’s free for everyone to use, even Black people. Greek mythology is her escape from an upbringing that involves domestic violence and molestation. “It’s peaceful and quiet in the Library. No one shouts or throws things or hits anyone. If anyone talks, the Librarian puts a finger to her mouth and tells them to shush.”

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer affirms the social benefits of libraries: “I love bookstores for many reasons but revere both the idea and the practice of public libraries. To me, they embody the civic-scale practice of a gift economy and the notion of common property. … We don’t each have to own everything. The books at the library belong to everyone, serving the public with free books”.

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer affirms the social benefits of libraries: “I love bookstores for many reasons but revere both the idea and the practice of public libraries. To me, they embody the civic-scale practice of a gift economy and the notion of common property. … We don’t each have to own everything. The books at the library belong to everyone, serving the public with free books”.

After Rebecca Knuth retired from an academic career in library and information science, she moved to London for a master’s degree in creative nonfiction and joined the London Library as well as the public library. But in her memoir London Sojourn (coming out in January), she recalls that she caught the library bug early: “Each weekday, I bused to school and, afterward, trudged to the library and then rode home with my geologist father. … Mostly, I read.”

After Rebecca Knuth retired from an academic career in library and information science, she moved to London for a master’s degree in creative nonfiction and joined the London Library as well as the public library. But in her memoir London Sojourn (coming out in January), she recalls that she caught the library bug early: “Each weekday, I bused to school and, afterward, trudged to the library and then rode home with my geologist father. … Mostly, I read.”

And in Joyride, Susan Orlean recounts the writing of each of her books, including The Library Book, which is about the 1986 arson at the Los Angeles Central Library but also, more widely, about what libraries have to offer and the oddballs often connected with them.

And in Joyride, Susan Orlean recounts the writing of each of her books, including The Library Book, which is about the 1986 arson at the Los Angeles Central Library but also, more widely, about what libraries have to offer and the oddballs often connected with them.

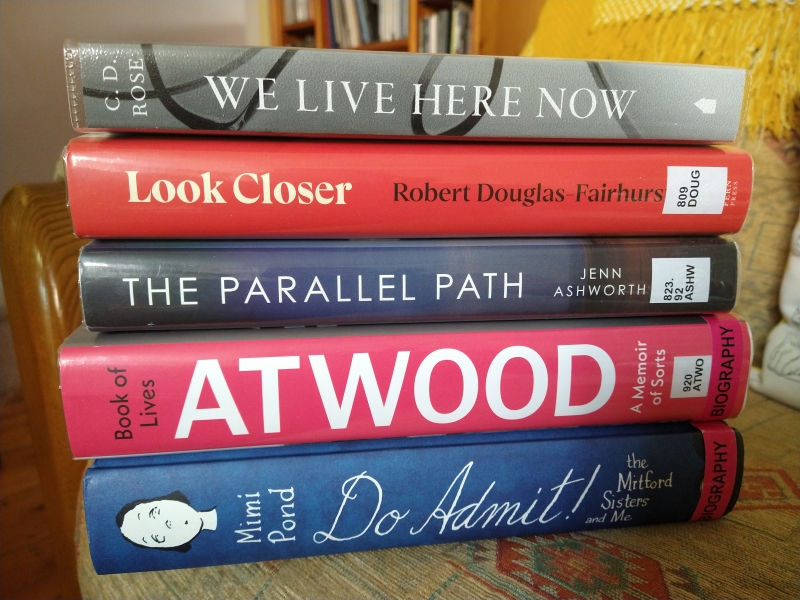

My library use over the last month:

(links are to any reviews of books not already covered on the blog)

READ

- Mum’s Busy Work by Jacinda Ardern; illus. Ruby Jones

- Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood

- Storm-Cat by Magenta Fox

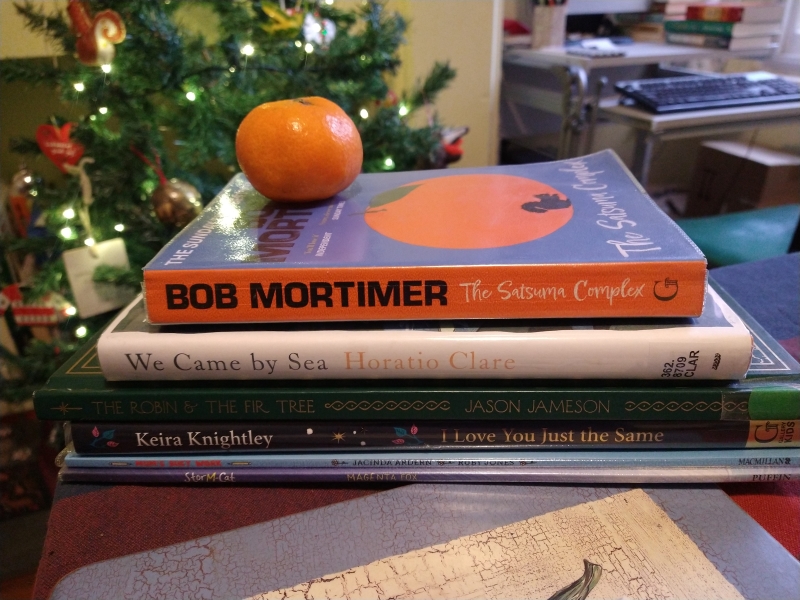

- The Robin & the Fir Tree by Jason Jameson

- I Love You Just the Same by Keira Knightley – Proof that celebrities should not be writing children’s books. I would say the story and drawings were pretty good … if she were a college student.

- Winter by Val McDermid

- The Search for the Giant Arctic Jellyfish, The Search for Carmella, & The Search for Our Cosmic Neighbours by Chloe Savage

- Weirdo Goes Wild by Zadie Smith and Nick Laird; illustrated by Magenta Fox

- Murder Most Unladylike by Robin Stevens

+ A final contribution to #DoorstoppersInDecember

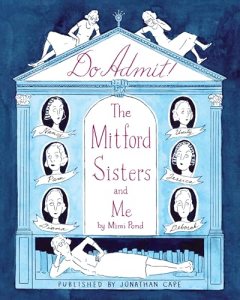

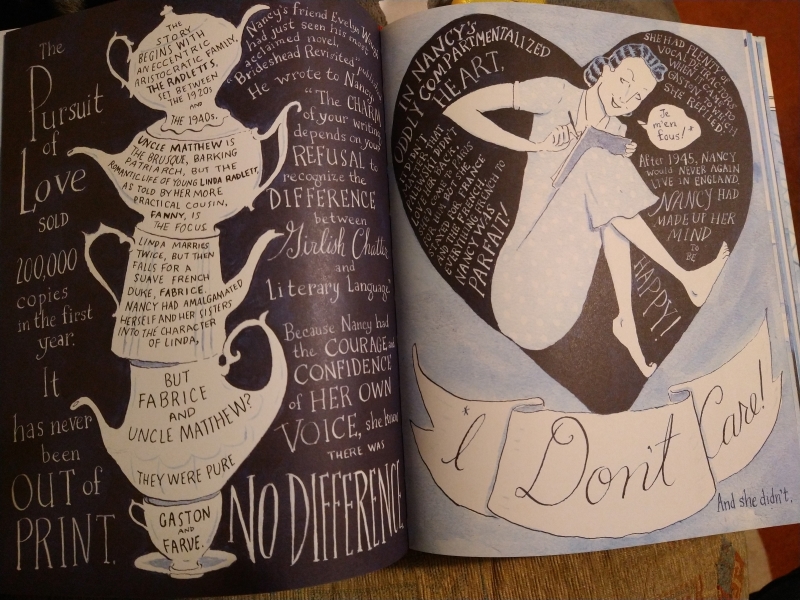

Do Admit: The Mitford Sisters and Me by Mimi Pond

Truth really is stranger than fiction. Of the six Mitford sisters, two were fascists (Diana and Unity) and one was a communist (Jessica). Two became popular authors (Nancy and Jessica). One (Unity) was pals with Hitler and shot herself in the head when Britain went to war with Germany; she didn’t die then but nine years later of an infection from the bullet still stuck in her brain. This is all rich fodder for a biographer – the batshit lives of the rich and famous are always going to fascinate us peons – and Pond’s comics treatment is a great way of keeping history from being one boring event after another. Although she uses the same Prussian blue tones throughout, she mixes up the format, sometimes employing 3–5 panes but often choosing to create one- or two-page spreads focusing on a face, a particular setting or a montage. No two pages are exactly alike and information is conveyed through dialogue, documents and quotations. If just straight narrative, there are different typefaces or text colours and it is interspersed with the pictures in a novel way. Whether or not you know a thing about the Mitfords, the book intrigues with its themes of family dynamics, grief, political divisions, wealth and class. My only misgiving, really, was about the “and Me” part of the title; Pond appears in maybe 5% of the book, and the only personal connections I gleaned were that she wished she had sisters, wanted to escape, and envied privilege and pageantry. [444 pages]

Truth really is stranger than fiction. Of the six Mitford sisters, two were fascists (Diana and Unity) and one was a communist (Jessica). Two became popular authors (Nancy and Jessica). One (Unity) was pals with Hitler and shot herself in the head when Britain went to war with Germany; she didn’t die then but nine years later of an infection from the bullet still stuck in her brain. This is all rich fodder for a biographer – the batshit lives of the rich and famous are always going to fascinate us peons – and Pond’s comics treatment is a great way of keeping history from being one boring event after another. Although she uses the same Prussian blue tones throughout, she mixes up the format, sometimes employing 3–5 panes but often choosing to create one- or two-page spreads focusing on a face, a particular setting or a montage. No two pages are exactly alike and information is conveyed through dialogue, documents and quotations. If just straight narrative, there are different typefaces or text colours and it is interspersed with the pictures in a novel way. Whether or not you know a thing about the Mitfords, the book intrigues with its themes of family dynamics, grief, political divisions, wealth and class. My only misgiving, really, was about the “and Me” part of the title; Pond appears in maybe 5% of the book, and the only personal connections I gleaned were that she wished she had sisters, wanted to escape, and envied privilege and pageantry. [444 pages] ![]()

CURRENTLY READING

- The Parallel Path: Love, Grit and Walking the North by Jenn Ashworth

- The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier

- Of Thorn & Briar: A Year with the West Country Hedgelayer by Paul Lamb

- The Satsuma Complex by Bob Mortimer (for book club in January; I’m grumpy about it because I didn’t vote for this one, had no idea who the author [a TV comedian in the UK] was, and the writing is shaky at best)

- We Live Here Now by C.D. Rose

SKIMMED

- Look Closer: How to Get More out of Reading by Robert Douglas-Fairhurst

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

- It’s Not a Bloody Trend: Understanding Life as an ADHD Adult by Kat Brown

- We Came by Sea by Horatio Clare

ON HOLD, TO BE COLLECTED

- The Two Faces of January by Patricia Highsmith

- Arsenic for Tea by Robin Stevens

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

- Honour & Other People’s Children by Helen Garner

- Snegurochka by Judith Heneghan

- Ultra-Processed People by Dr. Chris van Tulleken (for book club in February)

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- Night Life: Walking Britain’s Wild Landscapes after Dark by John Lewis-Stempel

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

Best Backlist Reads of the Year

I consistently find that many of my most memorable reads are older rather than current-year releases. Four of these are from 2023–4; the other nine are from 2012 or earlier, with the oldest from 1939. My selections are alphabetical within genre but in no particular rank order. Repeated themes included health, ageing, death, fascism, regret and a search for home and purpose. Reading more from these authors would probably help to ensure a great reading year in 2026!

Some trivia:

- 4 were read for 20 Books of Summer (Hadfield, King, Verghese and Walter)

- 3 were rereads for book club (Ishiguro, O’Farrell and Williams) – just like last year!

- 1 was part of my McKitterick Prize judge reading (Elkin)

- 1 was read for 1952 Club (Highsmith)

- 1 was a review catch-up book (Parker)

- 1 was a book I’d been ‘reading’ since 2021 (The Bell Jar)

- The title of one (O’Farrell) was taken from another (The Bell Jar)

Fiction & Poetry

Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin: Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in this intellectual tour de force. As history repeats itself during one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down. This was our collective runner-up for the 2025 McKitterick Prize, but would have been my overall winner.

Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin: Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in this intellectual tour de force. As history repeats itself during one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down. This was our collective runner-up for the 2025 McKitterick Prize, but would have been my overall winner.

Carol by Patricia Highsmith: Widely considered the first lesbian novel with a happy ending. Therese, a 19-year-old aspiring stage designer, meets a wealthy housewife – “Mrs. H. F. Aird” (Carol) – in a New York City department store one Christmas. When the women set off on a road trip, they’re trailed by a private detective looking for evidence against Carol in a custody battle. It’s a beautiful and subtle romance that unfolds despite the odds and shares the psychological intensity of Highsmith’s mysteries.

Carol by Patricia Highsmith: Widely considered the first lesbian novel with a happy ending. Therese, a 19-year-old aspiring stage designer, meets a wealthy housewife – “Mrs. H. F. Aird” (Carol) – in a New York City department store one Christmas. When the women set off on a road trip, they’re trailed by a private detective looking for evidence against Carol in a custody battle. It’s a beautiful and subtle romance that unfolds despite the odds and shares the psychological intensity of Highsmith’s mysteries.

Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood: Isherwood intended for these autofiction stories to contribute to a “huge episodic novel of pre-Hitler Berlin.” Two “Berlin Diary” segments from 1930 and 1933 reveal a change in tenor accompanying the rise of Nazism. Even in lighter pieces, menace creeps in through characters’ offhand remarks about “dirty Jews” ruining the country. Famously, the longest story introduces club singer Sally Bowles. I later read Mr Norris Changes Trains as well. Witty and humane, restrained but vigilant.

Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood: Isherwood intended for these autofiction stories to contribute to a “huge episodic novel of pre-Hitler Berlin.” Two “Berlin Diary” segments from 1930 and 1933 reveal a change in tenor accompanying the rise of Nazism. Even in lighter pieces, menace creeps in through characters’ offhand remarks about “dirty Jews” ruining the country. Famously, the longest story introduces club singer Sally Bowles. I later read Mr Norris Changes Trains as well. Witty and humane, restrained but vigilant.

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro: I first read this pre-blog, back when I dutifully read Booker winners whether or not I expected to like them. I was too young then for its theme of regret over things done and left undone; I didn’t yet know that sometimes in life, it really is too late. When I reread it for February book club, it hit me hard. I wrote no review at the time (more fool me), but focused less on the political message than on the refined depiction of upper-crust English society and the brilliance of Stevens the unreliable, repressed narrator.

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro: I first read this pre-blog, back when I dutifully read Booker winners whether or not I expected to like them. I was too young then for its theme of regret over things done and left undone; I didn’t yet know that sometimes in life, it really is too late. When I reread it for February book club, it hit me hard. I wrote no review at the time (more fool me), but focused less on the political message than on the refined depiction of upper-crust English society and the brilliance of Stevens the unreliable, repressed narrator.

Pet Sematary by Stephen King: A dread-laced novel about how we deal with the reality of death. Is bringing the dead back a cure for grief or a horrible mistake? A sleepy Maine town harbours many cautionary tales, and the Creeds have more than their fair share of sorrow. Louis is a likable protagonist whose vortex of obsession and mental health is gripping. In the last quarter, which I read on a long train ride, I couldn’t turn the pages any faster. Sterling entertainment, but also surprisingly poignant. (And not gruesome until right towards the end.)

Pet Sematary by Stephen King: A dread-laced novel about how we deal with the reality of death. Is bringing the dead back a cure for grief or a horrible mistake? A sleepy Maine town harbours many cautionary tales, and the Creeds have more than their fair share of sorrow. Louis is a likable protagonist whose vortex of obsession and mental health is gripping. In the last quarter, which I read on a long train ride, I couldn’t turn the pages any faster. Sterling entertainment, but also surprisingly poignant. (And not gruesome until right towards the end.)

The Bell Jar & Ariel by Sylvia Plath: Given my love of mental hospital accounts, it’s a wonder I’d not read this classic work of women’s autofiction before. Esther Greenwood is the stand-in for Plath: a talented college student who, after working in New York City during the remarkable summer of 1953, plunges into mental ill health. An enduringly relevant and absorbing read. / Ariel takes no prisoners. The images and vocabulary are razor-sharp and the first and last lines or stanzas are particularly memorable.

The Bell Jar & Ariel by Sylvia Plath: Given my love of mental hospital accounts, it’s a wonder I’d not read this classic work of women’s autofiction before. Esther Greenwood is the stand-in for Plath: a talented college student who, after working in New York City during the remarkable summer of 1953, plunges into mental ill health. An enduringly relevant and absorbing read. / Ariel takes no prisoners. The images and vocabulary are razor-sharp and the first and last lines or stanzas are particularly memorable.

The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese: Wider events play out in the background (wars, partition, the fall of the caste system), but this saga sticks with one Kerala family in every generation of which someone drowns. I enjoyed the window onto St. Thomas Christianity, felt fond of all the characters, and appreciated how Verghese makes the Condition a cross between mystical curse and a diagnosable ailment. An intelligent soap opera that makes you think about storytelling, purpose and inheritance, this is extraordinary.

The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese: Wider events play out in the background (wars, partition, the fall of the caste system), but this saga sticks with one Kerala family in every generation of which someone drowns. I enjoyed the window onto St. Thomas Christianity, felt fond of all the characters, and appreciated how Verghese makes the Condition a cross between mystical curse and a diagnosable ailment. An intelligent soap opera that makes you think about storytelling, purpose and inheritance, this is extraordinary.

Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter: I was captivated by the shabby glamour of Pasquale’s hotel in Porto Vergogna on the coast of northern Italy. A myriad of threads and formats – a movie pitch, a would-be Hemingway’s first chapter of a never-finished wartime opus, an excerpt from a producer’s autobiography and a play transcript – coalesce to flesh out what happened in the summer of 1962 and how the last half-century has treated all the supporting players. Warm, timeless and with great scenes, one of which had me in stitches. Fantastic.

Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter: I was captivated by the shabby glamour of Pasquale’s hotel in Porto Vergogna on the coast of northern Italy. A myriad of threads and formats – a movie pitch, a would-be Hemingway’s first chapter of a never-finished wartime opus, an excerpt from a producer’s autobiography and a play transcript – coalesce to flesh out what happened in the summer of 1962 and how the last half-century has treated all the supporting players. Warm, timeless and with great scenes, one of which had me in stitches. Fantastic.

Stoner by John Williams: What a quiet masterpiece. A whole life, birth to death, with all its sadness and failure and tragedy; but also joy and resistance and dignity. One doesn’t have to do amazing things that earn the world’s accolades to find vocation and meaning. Just as powerful a second time (I first read it in 2013). I was especially struck by the power plays in Stoner’s marriage and university department, and how well Williams dissects them. It’s more about atmosphere than plot – and that melancholy tone will stay with you.

Stoner by John Williams: What a quiet masterpiece. A whole life, birth to death, with all its sadness and failure and tragedy; but also joy and resistance and dignity. One doesn’t have to do amazing things that earn the world’s accolades to find vocation and meaning. Just as powerful a second time (I first read it in 2013). I was especially struck by the power plays in Stoner’s marriage and university department, and how well Williams dissects them. It’s more about atmosphere than plot – and that melancholy tone will stay with you.

Nonfiction

Storm Pegs by Jen Hadfield: Not a straightforward memoir but a set of atmospheric vignettes. Hadfield, a British Canadian poet, moved to Shetland in 2006 and soon found her niche. It’s a life of wild swimming, beachcombing, fresh fish, folk music, seabirds, kind neighbours, and good cheer that warms the long winter nights. After the isolation of the pandemic comes the unexpected joy of a partner and pregnancy in her mid-forties. I savoured this for its language and sense of place; it made me hanker to return to Shetland.

Storm Pegs by Jen Hadfield: Not a straightforward memoir but a set of atmospheric vignettes. Hadfield, a British Canadian poet, moved to Shetland in 2006 and soon found her niche. It’s a life of wild swimming, beachcombing, fresh fish, folk music, seabirds, kind neighbours, and good cheer that warms the long winter nights. After the isolation of the pandemic comes the unexpected joy of a partner and pregnancy in her mid-forties. I savoured this for its language and sense of place; it made me hanker to return to Shetland.

I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death by Maggie O’Farrell: (The final book club reread.) The memoir-in-essays is a highly effective form because it focuses on themes or moments of intensity and doesn’t worry about accounting for boring intermediate material. These pieces form a vibrant picture of a life and also inspire awe at what the human body can withstand. The present tense and a smattering of second person make the work immediate and invite readers to feel their way into her situations. The last two essays are the pinnacle.

I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death by Maggie O’Farrell: (The final book club reread.) The memoir-in-essays is a highly effective form because it focuses on themes or moments of intensity and doesn’t worry about accounting for boring intermediate material. These pieces form a vibrant picture of a life and also inspire awe at what the human body can withstand. The present tense and a smattering of second person make the work immediate and invite readers to feel their way into her situations. The last two essays are the pinnacle.

Understorey: A Year among Weeds by Anna Chapman Parker: I owe this a full review in the new year. Parker set out to study and sketch weeds as a way of cultivating attention and stillness as well as celebrating the everyday and overlooked. Daily drawings and entries bear witness to seasons changing but also to the minute alterations she observes in herself and her children. For me, this was all the more special because I’ve holidayed in Berwick-on-Tweed and could picture a lot of the ‘overgrown’ spaces she honours by making them her subjects.

Understorey: A Year among Weeds by Anna Chapman Parker: I owe this a full review in the new year. Parker set out to study and sketch weeds as a way of cultivating attention and stillness as well as celebrating the everyday and overlooked. Daily drawings and entries bear witness to seasons changing but also to the minute alterations she observes in herself and her children. For me, this was all the more special because I’ve holidayed in Berwick-on-Tweed and could picture a lot of the ‘overgrown’ spaces she honours by making them her subjects.

What were some of your best backlist reads this year?

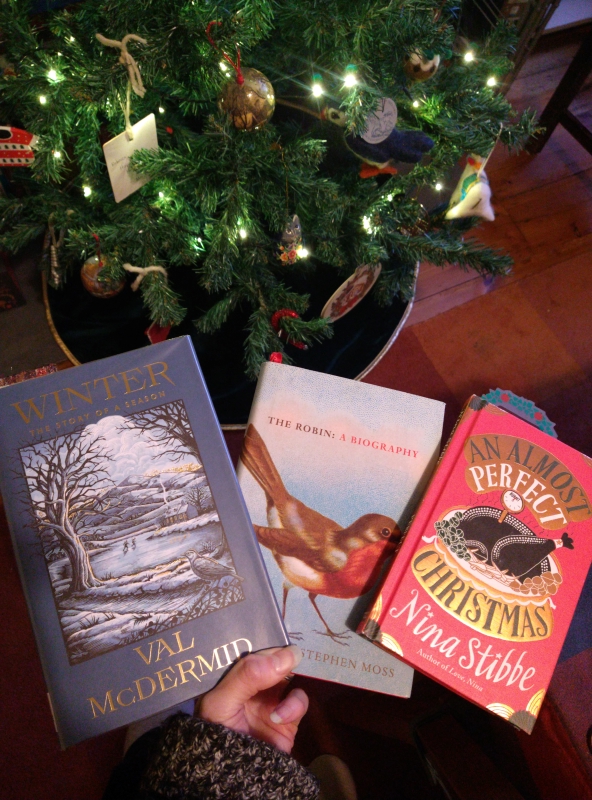

Seasons Readings: Winter, The Robin, & An Almost Perfect Christmas

I’m marking Christmas Eve with cosy reflections on the season, a biography of Britons’ favourite bird (and a bonus seasonal fairy tale), and a mixed bag of essays and stories about the obligations and annoyances of the holidays.

Winter by Val McDermid (2025)

I didn’t realize that Michael Morpurgo’s Spring was the launch of a series of short nonfiction books on the seasons. McDermid writes a book a year, always starting it in early January. She evokes the Scottish winter’s “Janus-faced” character: cosy but increasingly storm-tossed. In few-page essays, she looks for nature’s clues, delves into childhood memories, and traverses the season through traditional celebrations as she has experienced them in Edinburgh and Fife: Hallowe’en, Bonfire Night, Christmas, and New Year’s Eve. The festivities are a collective way of taking the mind off of the season’s hardships, she suggests. I was amused by her mother’s recipe for soup, which she described as more of a “rummage” for whatever vegetables you have in the fridge. It was my first time reading McDermid and, while I don’t know that I will ever pick up one of her crime novels, this was pleasant. I reckon I’d read Bernardine Evaristo on summer and Kate Mosse on autumn, too. (Public library)

I didn’t realize that Michael Morpurgo’s Spring was the launch of a series of short nonfiction books on the seasons. McDermid writes a book a year, always starting it in early January. She evokes the Scottish winter’s “Janus-faced” character: cosy but increasingly storm-tossed. In few-page essays, she looks for nature’s clues, delves into childhood memories, and traverses the season through traditional celebrations as she has experienced them in Edinburgh and Fife: Hallowe’en, Bonfire Night, Christmas, and New Year’s Eve. The festivities are a collective way of taking the mind off of the season’s hardships, she suggests. I was amused by her mother’s recipe for soup, which she described as more of a “rummage” for whatever vegetables you have in the fridge. It was my first time reading McDermid and, while I don’t know that I will ever pick up one of her crime novels, this was pleasant. I reckon I’d read Bernardine Evaristo on summer and Kate Mosse on autumn, too. (Public library) ![]()

The Robin: A Biography – A Year in the Life of Britain’s Favourite Bird by Stephen Moss (2017)

I’ve also read Moss’s most recent bird monograph, The Starling. Both provide a thorough yet accessible introduction to a beloved species’ history, behaviour, and cultural importance. The month-by-month structure works well here: Moss’s observations in his garden and on his local patch lead into discussions of what birds are preoccupied with at certain times of year. Such a narrative approach makes the details less tedious. European robins are known for singing pretty much year-round, and because hardly any migrate – only 5%, it’s thought – they feel like constant companions. They are inquisitive garden guests, visiting feeders and hanging around to see if we monkey-pigs might dig up some juicy worms for them.

I’ve also read Moss’s most recent bird monograph, The Starling. Both provide a thorough yet accessible introduction to a beloved species’ history, behaviour, and cultural importance. The month-by-month structure works well here: Moss’s observations in his garden and on his local patch lead into discussions of what birds are preoccupied with at certain times of year. Such a narrative approach makes the details less tedious. European robins are known for singing pretty much year-round, and because hardly any migrate – only 5%, it’s thought – they feel like constant companions. They are inquisitive garden guests, visiting feeders and hanging around to see if we monkey-pigs might dig up some juicy worms for them.

(Last month, this friendly chap at an RSPB bird reserve near Exeter wondered if we might have a snack to share.)

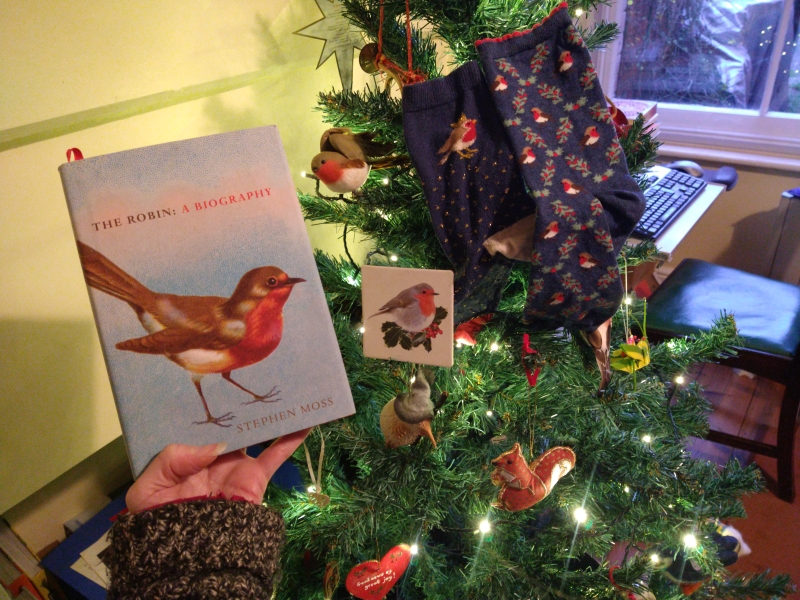

Although we like to think we see the same robins year after year, that’s very unlikely. One in four robins found dead has been killed by a domestic cat; most die of old age and/or starvation within a year. Robin pairs raise one or two broods per year and may attempt a third if the weather allows, but that high annual mortality rate (62%) means we’re not overrun. Compared to other notable species, then, they’re doing well. There are loads of poems and vintage illustrations and, what with robins’ associations with Christmas, this felt like a seasonally appropriate read. At Christmas 2022 I read the very similar Robin by Helen F. Wilson, but this was more engaging. (Free from C’s former colleague) ![]()

Our small collection of Christmas robin paraphernalia.

&

The Robin & the Fir Tree by Jason Jameson (2020)

Based on a Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale, this lushly illustrated children’s book stars a restless tree and a faithful robin. The tree resents being stuck in one place and envies his kin who have been made into ships to sail the world. Although his friend the robin describes everything and brings souvenirs, he can’t see the funfair and the flora of other landscapes for himself. “Every season will be just the same. How I long for something different to happen!” he cries. Cue a careful-what-you-wish-for message. When men with axes come to chop down the fir tree and display him in the town square, he feels a combination of trepidation and privilege. Human carelessness turns his sacrifice to waste, and only the robin knows how to make something good out of the wreckage. The art somewhat outshines the story but this is still a lovely hardback I’d recommend to adults and older children. (Public library)

Based on a Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale, this lushly illustrated children’s book stars a restless tree and a faithful robin. The tree resents being stuck in one place and envies his kin who have been made into ships to sail the world. Although his friend the robin describes everything and brings souvenirs, he can’t see the funfair and the flora of other landscapes for himself. “Every season will be just the same. How I long for something different to happen!” he cries. Cue a careful-what-you-wish-for message. When men with axes come to chop down the fir tree and display him in the town square, he feels a combination of trepidation and privilege. Human carelessness turns his sacrifice to waste, and only the robin knows how to make something good out of the wreckage. The art somewhat outshines the story but this is still a lovely hardback I’d recommend to adults and older children. (Public library) ![]()

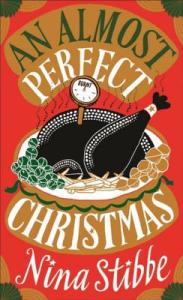

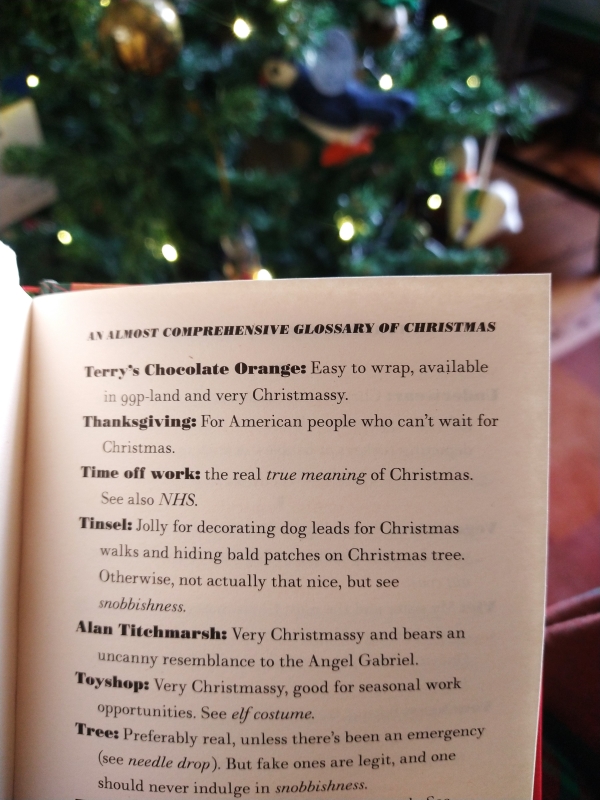

An Almost Perfect Christmas by Nina Stibbe (2017)

I reviewed this for Stylist magazine when it first came out and had fond memories of a witty collection I expected to dip into again and again. This time, though, Stibbe’s grumpy rants about turkey, family, choosing a tree and compiling the perfect Christmas party playlist fell flat with me. The four short stories felt particularly weak. I most recognized and enjoyed the sentiments in “Christmas Correspondence,” which is about the etiquette for round-robin letters and thank-you notes. The tongue-in-cheek glossary that closes the book is also amusing. But this has served its time in my collection and it’s off to the Little Free Library with it to, I hope, give someone else a chuckle on Christmas day. (Review copy)

I reviewed this for Stylist magazine when it first came out and had fond memories of a witty collection I expected to dip into again and again. This time, though, Stibbe’s grumpy rants about turkey, family, choosing a tree and compiling the perfect Christmas party playlist fell flat with me. The four short stories felt particularly weak. I most recognized and enjoyed the sentiments in “Christmas Correspondence,” which is about the etiquette for round-robin letters and thank-you notes. The tongue-in-cheek glossary that closes the book is also amusing. But this has served its time in my collection and it’s off to the Little Free Library with it to, I hope, give someone else a chuckle on Christmas day. (Review copy)

My original rating (2017): ![]()

My rating now: ![]()

It’s taken me a long time to feel festive this year, but after a couple of book club gatherings and a load of brief community events for the Newbury Living Advent Calendar plus the neighbourhood carol walk, I think I’m finally ready for Christmas. (Not that I’ve wrapped anything yet.) I had a couple of unexpected bookish gifts arrive earlier in December. First, I won the 21st birthday quiz on Kim’s blog and she sent a lovely parcel of Australian books and an apt tote bag. Then, I was sent an early finished copy of Julian Barnes’s upcoming (final) novel, Departure(s). We didn’t trust Benny to be sensible around a real tree so got an artificial one free from a neighbour to festoon with non-breakable ornaments. He discovered the world’s comfiest blanket and spends a lot of time sleeping on it, which has been helpful.

Merry Christmas, everyone! I have a bunch of year-end posts in preparation. It’ll be a day off tomorrow, of course, but here’s what to expect thereafter:

Friday 26th: Reporting back on Most Anticipated Reads of 2025

Saturday 27th: Reading Superlatives

Sunday 28th: Best Backlist Reads

Monday 29th: Love Your Library

Tuesday 30th: Runners-Up

Wednesday 31st: Best Books of 2025

Thursday 1st: Final Statistics for 2025

Friday 2nd: Early Recommendations for 2026

Monday 5th: Most Anticipated Titles of 2026

I’ve found Bloom’s short stories more successful than her novels. This is something of a halfway house: linked short stories (one of which was previously published in

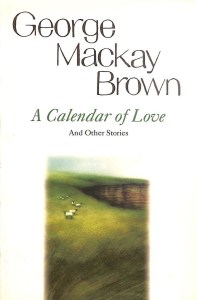

I’ve found Bloom’s short stories more successful than her novels. This is something of a halfway house: linked short stories (one of which was previously published in  The title story opens a collection steeped in the landscape and history of Orkney. Each month we check in with three characters: Jean, who lives with her ailing father at the pub they run; and her two very different suitors, pious Peter and drunken Thorfinn. When she gives birth in December, you have to page back to see that she had encounters with both men in March. Some are playful in this vein or resemble folk tales: a boy playing hooky from school, a distant cousin so hapless as to father three bairns in the same household, and a rundown of the grades of whisky available on the islands. Others with medieval time markers are overwhelmingly bleak, especially “Witch,” about a woman’s trial and execution – and one of two stories set out like a play for voices. I quite liked the flash fiction “The Seller of Silk Shirts,” about a young Sikh man who arrives on the islands, and “The Story of Jorfel Hayforks,” in which a Norwegian man sails to find the man who impregnated his sister and keeps losing a crewman at each stop through improbable accidents. This is an atmospheric book I would have liked to read on location, but few of the individual stories stand out. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

The title story opens a collection steeped in the landscape and history of Orkney. Each month we check in with three characters: Jean, who lives with her ailing father at the pub they run; and her two very different suitors, pious Peter and drunken Thorfinn. When she gives birth in December, you have to page back to see that she had encounters with both men in March. Some are playful in this vein or resemble folk tales: a boy playing hooky from school, a distant cousin so hapless as to father three bairns in the same household, and a rundown of the grades of whisky available on the islands. Others with medieval time markers are overwhelmingly bleak, especially “Witch,” about a woman’s trial and execution – and one of two stories set out like a play for voices. I quite liked the flash fiction “The Seller of Silk Shirts,” about a young Sikh man who arrives on the islands, and “The Story of Jorfel Hayforks,” in which a Norwegian man sails to find the man who impregnated his sister and keeps losing a crewman at each stop through improbable accidents. This is an atmospheric book I would have liked to read on location, but few of the individual stories stand out. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)  Mantel is best remembered for the Wolf Hall trilogy, but her early work includes a number of concise, sharp novels about growing up in the north of England. Carmel McBain attends a Catholic school in Manchester in the 1960s before leaving to study law at the University of London in 1970. In lockstep with her are a couple of friends, including Karina, who is of indeterminate Eastern European extraction and whose tragic Holocaust family history, added to her enduring poverty, always made her an object of pity for Carmel’s mother. But Karina as depicted by Carmel is haughty, even manipulative, and over the years their relationship swings between care and competition. As university students they live on the same corridor and have diverging experiences of schoolwork, romance, and food. “Now, I would not want you to think that this is a story about anorexia,” Carmel says early on, and indeed, she presents her condition as more like forgetting to eat. But then you recall tiny moments from her past when teachers and her mother shamed her for eating, and it’s clear a seed was sown. Carmel and her friends also deal with the results of the new-ish free love era. This is dark but funny, too, with Carmel likening roast parsnips to “ogres’ penises.” Further proof, along with

Mantel is best remembered for the Wolf Hall trilogy, but her early work includes a number of concise, sharp novels about growing up in the north of England. Carmel McBain attends a Catholic school in Manchester in the 1960s before leaving to study law at the University of London in 1970. In lockstep with her are a couple of friends, including Karina, who is of indeterminate Eastern European extraction and whose tragic Holocaust family history, added to her enduring poverty, always made her an object of pity for Carmel’s mother. But Karina as depicted by Carmel is haughty, even manipulative, and over the years their relationship swings between care and competition. As university students they live on the same corridor and have diverging experiences of schoolwork, romance, and food. “Now, I would not want you to think that this is a story about anorexia,” Carmel says early on, and indeed, she presents her condition as more like forgetting to eat. But then you recall tiny moments from her past when teachers and her mother shamed her for eating, and it’s clear a seed was sown. Carmel and her friends also deal with the results of the new-ish free love era. This is dark but funny, too, with Carmel likening roast parsnips to “ogres’ penises.” Further proof, along with  Unexpected Lessons in Love by Bernardine Bishop (2013): I loved Bishop’s

Unexpected Lessons in Love by Bernardine Bishop (2013): I loved Bishop’s  A Rough Guide to the Heart by Pam Houston (1999): A mix of personal essays and short travel pieces. The material about her dysfunctional early family life, her chaotic dating, and her thrill-seeking adventures in the wilderness is reminiscent of the highly autobiographical

A Rough Guide to the Heart by Pam Houston (1999): A mix of personal essays and short travel pieces. The material about her dysfunctional early family life, her chaotic dating, and her thrill-seeking adventures in the wilderness is reminiscent of the highly autobiographical  The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier – A pleasant year’s diary of rural living and adjusting to her husband’s new diagnosis of neurodivergence.

The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier – A pleasant year’s diary of rural living and adjusting to her husband’s new diagnosis of neurodivergence.

He parcels out bits of this story in between pondering involuntary autobiographical memory (IAM), his “incurable but manageable” condition, and his possible legacy. He hopes he’ll be exonerated due to waiting until Stephen and Jean were dead to write about them and adopting Jean’s old Jack Russell terrier, Jimmy. His late wife, Pat Kavanagh, is never far from his thoughts, and he documents other losses among his peers, including Martin Amis (d. 2023 – for a short book, this is curiously dated, as if it hung around for years unfinished). There are also, as one would expect from Barnes, occasional references to French literature. Confident narration gives the sense of an author in full control of his material. Yet I found much of it tedious. He’s addressed subjectivity much more originally in other works, and the various strands here feel like incomplete ideas shoehorned into one volume.

He parcels out bits of this story in between pondering involuntary autobiographical memory (IAM), his “incurable but manageable” condition, and his possible legacy. He hopes he’ll be exonerated due to waiting until Stephen and Jean were dead to write about them and adopting Jean’s old Jack Russell terrier, Jimmy. His late wife, Pat Kavanagh, is never far from his thoughts, and he documents other losses among his peers, including Martin Amis (d. 2023 – for a short book, this is curiously dated, as if it hung around for years unfinished). There are also, as one would expect from Barnes, occasional references to French literature. Confident narration gives the sense of an author in full control of his material. Yet I found much of it tedious. He’s addressed subjectivity much more originally in other works, and the various strands here feel like incomplete ideas shoehorned into one volume. Often, the short chapters are vignettes starring one or more of the central characters. When Joan has a fall down her stairs and lands in rehab, Kitzi takes over as de facto HDC leader. A musical couple’s hoarding and cat colony become her main preoccupation. Emily deals with family complications I didn’t fully understand for want of backstory, and Arlene realizes dementia is affecting her daily life. Susie, the “baby” of the group at 63, takes in Joan’s cat, Oscar, and meets someone through online dating. The novel covers four months of 2022–23, anchored by a string of holidays (Halloween, Thanksgiving, Christmas); events such as John Fetterman’s election and ongoing Covid precautions; and the cycle of the Church year.