The Moomins and the Great Flood (#Moomins80) & Poetry (#ReadIndies)

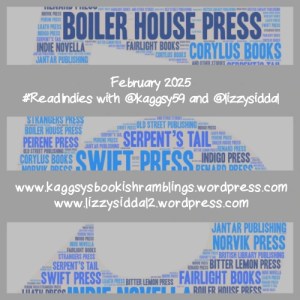

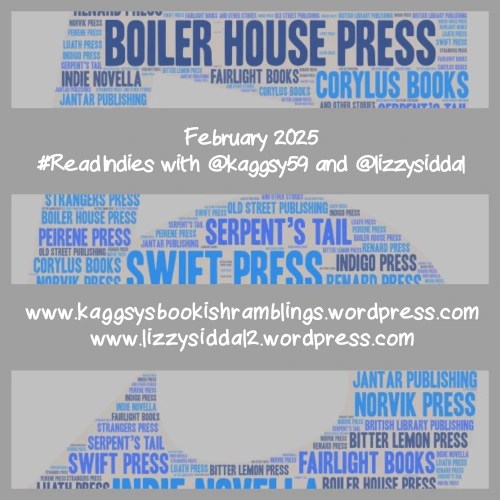

To mark the 80th anniversary of Tove Jansson’s Moomins books, Kaggsy, Liz et al. are doing a readalong of the whole series, starting with The Moomins and the Great Flood. I received a copy of Sort Of Books’ 2024 reissue edition for Christmas, so I was unknowingly all set to take part. I also give quick responses to a couple of collections I read recently from two favourite indie poetry publishers in the UK, The Emma Press and Carcanet Press. These are reads 9–11 for Kaggsy and Lizzy Siddal’s Reading Independent Publishers Month challenge.

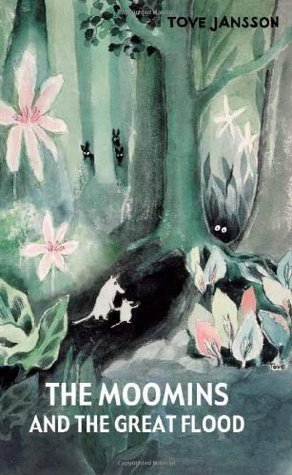

The Moomins and the Great Flood by Tove Jansson (1945; 1991)

[Translated from the Swedish by David McDuff]

Moomintroll and Moominmamma are the only two Moomins who appear here. They’re nomads, looking for a place to call home and searching for Moominpappa, who has disappeared. With them are “the creature” (later known as Sniff) and Tulippa, a beautiful flower-girl. They encounter a Serpent and a sea-troll and make a stormy journey in a boat piloted by the Hattifatteners. My favourite scene has Moominmamma rescuing a cat and her kittens from rising floodwaters. The book ends with the central pair making their way to the idyllic valley that will be the base for all their future adventures. Sort Of and Frank Cottrell Boyce, who wrote an introduction, emphasize how (climate) refugees link Jansson’s writing in 1939 to today, but it’s a subtle theme. Still, one always worth drawing attention to.

Moomintroll and Moominmamma are the only two Moomins who appear here. They’re nomads, looking for a place to call home and searching for Moominpappa, who has disappeared. With them are “the creature” (later known as Sniff) and Tulippa, a beautiful flower-girl. They encounter a Serpent and a sea-troll and make a stormy journey in a boat piloted by the Hattifatteners. My favourite scene has Moominmamma rescuing a cat and her kittens from rising floodwaters. The book ends with the central pair making their way to the idyllic valley that will be the base for all their future adventures. Sort Of and Frank Cottrell Boyce, who wrote an introduction, emphasize how (climate) refugees link Jansson’s writing in 1939 to today, but it’s a subtle theme. Still, one always worth drawing attention to.

I read my first Moomins tale in 2011 and have been reading them out of order and at random ever since; only one remains unread. Unfortunately, I did not find it rewarding to go right back to the beginning. At barely 50 pages (padded out by the Cottrell-Boyce introduction and an appendix of Jansson’s who’s-who notes), this story feels scant, offering little more than a hint of the delightful recurring characters and themes to come. Jansson had not yet given the Moomins their trademark rounded hippo-like snouts; they’re more alien and less cute here. It’s like seeing early Jim Henson drawings of Garfield before he was a fat cat. That just ain’t right. I don’t know why I’d assumed the Moomins are human-size. When you see one next to a marabou stork you realize how tiny they are; Jansson’s notes specify 20 cm tall. (Gift)

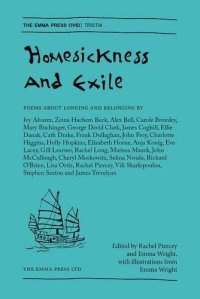

The Emma Press Anthology of Homesickness and Exile, ed. by Rachel Piercey and Emma Wright (2014)

This early anthology chimes with the review above, as well as more generally with the Moomins series’ frequent tone of melancholy and nostalgia. A couple of excerpts from Stephen Sexton’s “Skype” reveal a typical viewpoint: “That it’s strange to miss home / and be in it” and “How strange home / does not stay as it’s left.” (Such wonderfully off-kilter enjambment in the latter!) People are always changing, just as much as places – ‘You can’t go home again’; ‘You never set foot in the same river twice’ and so on. Zeina Hashem Beck captures these ideas in the first stanza of “Ten Years Later in a Different Bar”: “The city has changed like cities do; / the bar where we sang has closed. / We have changed like cities do.”

This early anthology chimes with the review above, as well as more generally with the Moomins series’ frequent tone of melancholy and nostalgia. A couple of excerpts from Stephen Sexton’s “Skype” reveal a typical viewpoint: “That it’s strange to miss home / and be in it” and “How strange home / does not stay as it’s left.” (Such wonderfully off-kilter enjambment in the latter!) People are always changing, just as much as places – ‘You can’t go home again’; ‘You never set foot in the same river twice’ and so on. Zeina Hashem Beck captures these ideas in the first stanza of “Ten Years Later in a Different Bar”: “The city has changed like cities do; / the bar where we sang has closed. / We have changed like cities do.”

Departures, arrivals; longing, regret: these are classic themes from Ovid (the inspiration for this volume) onward. Holly Hopkins and Rachel Long were additional familiar names for me to see in the table of contents. My two favourite poems were “The Restaurant at One Thousand Feet” (about the CN Tower in Toronto) by John McCullough, whose collections I’ve enjoyed before; and “The Town” by Alex Bell, which personifies a closed-minded Dorset community – “The town wraps me tight as swaddling … When I came to the town I brought things with me / from outside, and the town took them / for my own good.” Home is complicated – something one might spend an entire life searching for, or trying to escape. (New purchase from publisher)

Gold by Elaine Feinstein (2000)

I’d enjoyed Feinstein’s poetry before. The long title poem, which opens the collection, is a monologue by Lorenzo da Ponte, a collaborator of Mozart. Though I was not particularly enraptured with his story, there were some great lines here:

I’d enjoyed Feinstein’s poetry before. The long title poem, which opens the collection, is a monologue by Lorenzo da Ponte, a collaborator of Mozart. Though I was not particularly enraptured with his story, there were some great lines here:

I wanted to live with a bit of flash and brio,

rather than huddle behind ghetto gates.

The last two stanzas are especially memorable:

Poor Mozart was so much less fortunate.

My only sadness is to think of him, a pauper,

lying in his grave, while I became

Professor of Italian literature.

Nobody living can predict their fate.

I moved across the cusp of a new age,

to reach this present hour of privilege.

On this earth, luck is worth more than gold.

Politics, manners, morals all evolve

uncertainly. Best then to be bold.

Best then to be bold!

Of the discrete “Lyrics” that follow, I most liked “Options,” about a former fiancé (“who can tell how long we would have / burned together, before turning to ash?”) and “Snowdonia,” in which she’s surprised when a memory of her father resurfaces through a photograph. Talking to the Dead was more consistently engaging. (Secondhand purchase – Bridport Old Books, 2023)

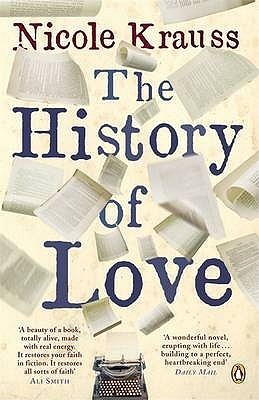

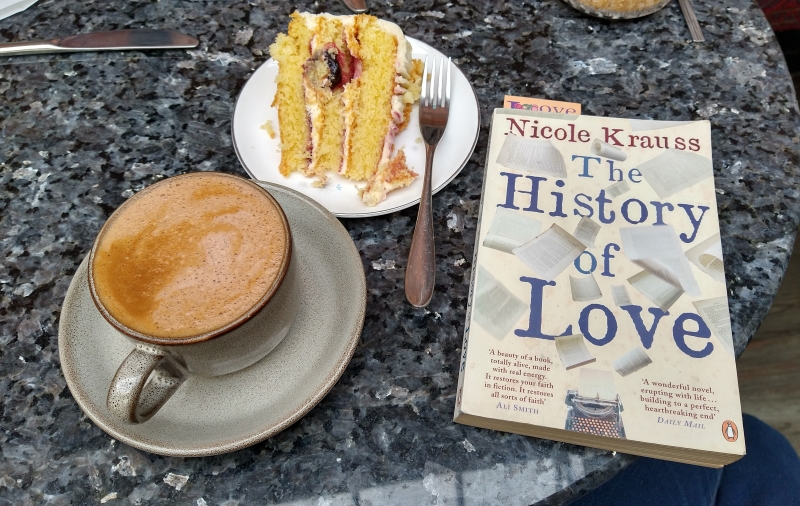

Adventures in Rereading: The History of Love by Nicole Krauss for Valentine’s Day

Special Valentine’s edition. Every year I say I’m really not a Valentine’s Day person and yet manage a themed post featuring one or more books with “Love” or “Heart” in the title. This is the ninth year in a row, in fact – after 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, and 2024!

Leopold Gursky is an octogenarian Holocaust survivor, locksmith and writer manqué; Alma Singer is a misfit teenager grieving her father. What connects them? A philosophical novel called The History of Love, lost for years before being published in Spanish. Alma’s late father saw it in a bookshop window in Buenos Aires and bought it for his love. They adored it so much they named their daughter after the heroine. Now his widow is translating it into English on commission for a covert client. Leo and Alma’s distinctive voices, wry but earnest, really make this sparkle. Alma’s sections are numbered fragments from a diary and there are also excerpts from the book within the book. My only critique would be that she sounds young for her age; her precocity makes her seem closer to 10 than 15. But her little brother Bird, who thinks he may be the messiah, is a delight. The array of New York City locales includes a life drawing class, a record office, and a Central Park bench. A gentle air of mystery circulates as we work out who Leo’s son is and how Alma tracks down the author. It’s a bittersweet story that insists on love as an equivalent to loss. Complex but accessible, bookish and heartfelt, it’s one to recommend to my book club in the future. (Little Free Library)

Leopold Gursky is an octogenarian Holocaust survivor, locksmith and writer manqué; Alma Singer is a misfit teenager grieving her father. What connects them? A philosophical novel called The History of Love, lost for years before being published in Spanish. Alma’s late father saw it in a bookshop window in Buenos Aires and bought it for his love. They adored it so much they named their daughter after the heroine. Now his widow is translating it into English on commission for a covert client. Leo and Alma’s distinctive voices, wry but earnest, really make this sparkle. Alma’s sections are numbered fragments from a diary and there are also excerpts from the book within the book. My only critique would be that she sounds young for her age; her precocity makes her seem closer to 10 than 15. But her little brother Bird, who thinks he may be the messiah, is a delight. The array of New York City locales includes a life drawing class, a record office, and a Central Park bench. A gentle air of mystery circulates as we work out who Leo’s son is and how Alma tracks down the author. It’s a bittersweet story that insists on love as an equivalent to loss. Complex but accessible, bookish and heartfelt, it’s one to recommend to my book club in the future. (Little Free Library) ![]()

Finishing my reread during a coffee date in Hungerford this morning.

My original rating (2011): ![]()

When I first read this, I mostly considered it in comparison to Krauss’s former husband Jonathan Safran Foer’s work. (I’ve long since read everything by both of them.) I noted then that it

has a lot of elements in common with Everything is Illuminated, such as a preoccupation with Eastern European and Jewish ancestry, quirky methods of narration including multiple voices, and a sweet humour that lies alongside such heart-rending stories of family and loss that tears are never far from your eyes. Leo Gursky and Alma Singer are delightful and distinct characters. I wasn’t sure about the missing/plagiarized/mistaken The History of Love itself; the ruined copies, the different translations, the way the manuscript was constantly changing hands – all this was intriguing, but the book itself was a postmodern jumble of magic realism and pointless meanderings of thought.

Dang, I was harsh! But admirably pithy about the plot. It’s intriguing that I’ve successfully reread Krauss but failed with Foer when I attempted Everything is Illuminated again in 2020. Reading the first, 9/11-set section of Confessions by Catherine Airey, I’ve also been recalling his Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close and thinking it probably wouldn’t stand up to a reread either. I suspect I’d find it mawkish, especially with its child narrator. Alma evades that trap, perhaps by being that little bit older, though she sounds young because of how geeky and sheltered she is.

Winter Reads, I: Michael Cunningham & Helen Moat

It’s been feeling springlike in southern England with plenty of birdsong and flowers, yet cold weather keeps making periodic returns. (For my next instalment of wintry reads, I’ll try to attract some snow to match the snowdrops by reading three “Snow” books.) Today I have a novel drawing on a melancholy Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale and a nature/travel book about learning to appreciate winter.

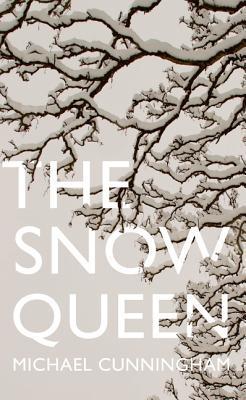

The Snow Queen by Michael Cunningham (2014)

It was among my favourite first lines encountered last year: “A celestial light appeared to Barrett Meeks in the sky over Central Park, four days after Barrett had been mauled, once again, by love.” Barrett is gay and shares an apartment with his brother, Tyler, and Tyler’s fiancée, Beth. Beth has cancer and, though none of them has dared to hope that she will live, Barrett’s epiphany brings a supernatural optimism that will fuel them through the next few years, from one presidential election autumn (2004) to the next (2008). Meanwhile, Tyler, a stalled musician, returns to drugs to try to find inspiration for his wedding song for Beth. The other characters in the orbit of this odd love triangle of sorts are Liz, Beth and Barrett’s boss at a vintage clothing store, and Andrew, Liz’s decades-younger boyfriend. It’s a peculiar family unit that expands and contracts over the years.

It was among my favourite first lines encountered last year: “A celestial light appeared to Barrett Meeks in the sky over Central Park, four days after Barrett had been mauled, once again, by love.” Barrett is gay and shares an apartment with his brother, Tyler, and Tyler’s fiancée, Beth. Beth has cancer and, though none of them has dared to hope that she will live, Barrett’s epiphany brings a supernatural optimism that will fuel them through the next few years, from one presidential election autumn (2004) to the next (2008). Meanwhile, Tyler, a stalled musician, returns to drugs to try to find inspiration for his wedding song for Beth. The other characters in the orbit of this odd love triangle of sorts are Liz, Beth and Barrett’s boss at a vintage clothing store, and Andrew, Liz’s decades-younger boyfriend. It’s a peculiar family unit that expands and contracts over the years.

Of course, Cunningham takes inspiration, thematically and linguistically, from Hans Christian Andersen’s tale about love and conversion, most obviously in an early dreamlike passage about Tyler letting snow swirl into the apartment through the open windows:

He returns to the window. If that windblown ice crystal meant to weld itself to his eye, the transformation is already complete; he can see more clearly now with the aid of this minuscule magnifying mirror…

I was most captivated by the early chapters of the novel, picking it up late one night and racing to page 75, which is almost unheard of for me. The rest took me significantly longer to get through, and in the intervening five weeks or so much of the detail has evaporated. But I remember that I got Chris Adrian and Julia Glass vibes from the plot and loved the showy prose. (And several times while reading I remarked to people around me how ironic it was that these characters in a 2014 novel are so outraged about Dubya’s re-election. Just you all wait two years, and then another eight!)

I fancy going on a mini Cunningham binge this year. I plan to recommend The Hours for book club, which would be a reread for me. Otherwise, I’ve only read his travel book, Land’s End. I own a copy of Specimen Days and the library has Day, but I’d have to source all the rest secondhand. Simon of Stuck in a Book is a big fan and here are his rankings. I have some great stuff ahead! (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com)

While the Earth Holds Its Breath: Embracing the Winter Season by Helen Moat (2024)

Like many of us, Moat struggles with mood and motivation during the darkest and coldest months of the year. Over the course of three recent winters overlapping with the pandemic, she strove to change her attitude. The book spins short autobiographical pieces out of wintry walks near her Derbyshire home or further afield. Paying closer attention to the natural spectacles of the season and indulging in cosy food and holiday rituals helped, as did trips to places where winters are either a welcome respite (Spain) or so much harsher as to put her own into perspective (Lapland and Japan). My favourite pieces of all were about sharing English Christmas traditions with new Ukrainian refugee friends.

Like many of us, Moat struggles with mood and motivation during the darkest and coldest months of the year. Over the course of three recent winters overlapping with the pandemic, she strove to change her attitude. The book spins short autobiographical pieces out of wintry walks near her Derbyshire home or further afield. Paying closer attention to the natural spectacles of the season and indulging in cosy food and holiday rituals helped, as did trips to places where winters are either a welcome respite (Spain) or so much harsher as to put her own into perspective (Lapland and Japan). My favourite pieces of all were about sharing English Christmas traditions with new Ukrainian refugee friends.

There were many incidents and emotions I could relate to here – a walk on the canal towpath always makes me feel better, and the car-heavy lifestyle I resume on trips to America feels unnatural.

Days are where we must live, but it didn’t have to be a prison of house and walls. I needed the rush of air, the slap of wind on my cheeks. I needed to feel alive. Outdoors.

I’d never liked the rain, but if I were to grow to love winters on my island, I had to learn to love wet weather, go out in it.

What can there be but winter? It belongs to the circle of life. And I belonged to winter, whether I liked it or not. Indoors, or moving from house to vehicle and back to house again, I lost all sense of my place on this Earth. This world would be my home for just the smallest of moments in the vastness of time, in the turning of the seasons. It was a privilege, I realised.

However, the content is repetitive such that the three-year cycle doesn’t add a lot and the same sorts of pat sentences about learning to love winter recur. Were the timeline condensed, there might have been more of a focus on the more interesting travel segments, which also include France and Scotland. So many have jumped on the Wintering bandwagon, but Katherine May’s book felt fresh in a way the others haven’t.

With thanks to Saraband for the free copy for review.

Any wintry reading (or weather) for you lately?

Three on a Theme: Christmas Novellas I (Re-)Read This Year

I wasn’t sure I’d manage any holiday-appropriate reading this year, but thanks to their novella length I actually finished three, two in advance and one in a single sitting on the day itself. Two of these happen to be in translation: little slices of continental Christmas.

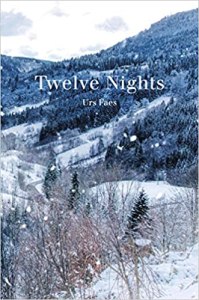

Twelve Nights by Urs Faes (2018; 2020)

[Translated from the German by Jamie Lee Searle]

In this Swiss novella, the Twelve Nights between Christmas and Epiphany are a time of mischief when good folk have to protect themselves from the tricks of evil spirits. Manfred has trekked back to his home valley hoping to make things right with his brother, Sebastian. They have been estranged for several decades – since Sebastian unexpectedly inherited the family farm and stole Manfred’s sweetheart, Minna. These perceived betrayals were met with a vengeful act of cruelty (but why oh why did it have to be against an animal?). At a snow-surrounded inn, Manfred convalesces and tries to summon the courage to show up at Sebastian’s door. At only 84 small-format pages, this is more of a short story. The setting and spare writing are appealing, as is the prospect of grace extended. But this was over before it began; it didn’t feel worth what I paid. Perhaps I would have been happier to encounter it in an anthology or a longer collection of Faes’s short fiction. (Secondhand – Hungerford Bookshop)

In this Swiss novella, the Twelve Nights between Christmas and Epiphany are a time of mischief when good folk have to protect themselves from the tricks of evil spirits. Manfred has trekked back to his home valley hoping to make things right with his brother, Sebastian. They have been estranged for several decades – since Sebastian unexpectedly inherited the family farm and stole Manfred’s sweetheart, Minna. These perceived betrayals were met with a vengeful act of cruelty (but why oh why did it have to be against an animal?). At a snow-surrounded inn, Manfred convalesces and tries to summon the courage to show up at Sebastian’s door. At only 84 small-format pages, this is more of a short story. The setting and spare writing are appealing, as is the prospect of grace extended. But this was over before it began; it didn’t feel worth what I paid. Perhaps I would have been happier to encounter it in an anthology or a longer collection of Faes’s short fiction. (Secondhand – Hungerford Bookshop) ![]()

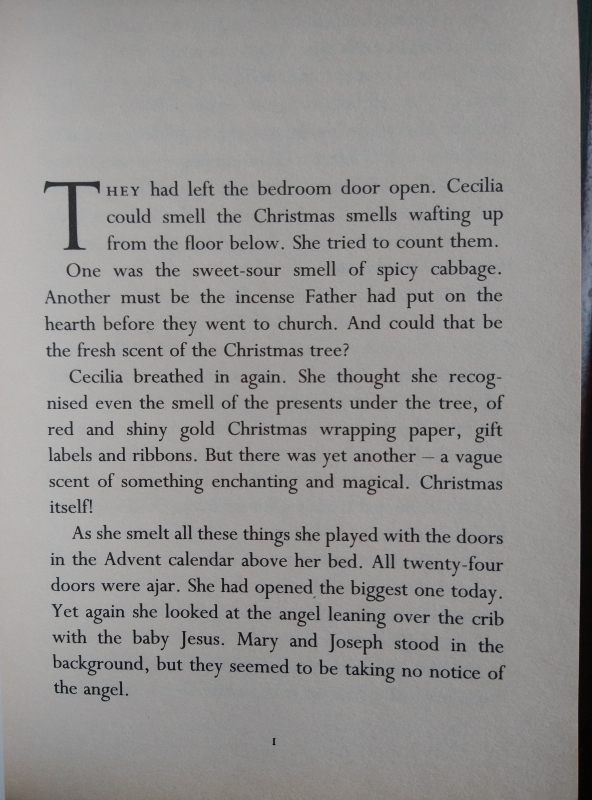

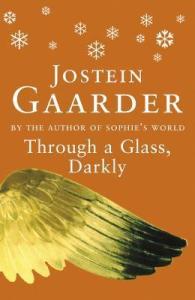

Through a Glass, Darkly by Jostein Gaarder (1993; 1998)

[Translated from the Norwegian by Elizabeth Rokkan]

On Christmas Day, Cecilia is mostly confined to bed, yet the preteen experiences the holiday through the sounds and smells of what’s happening downstairs. (What a cosy first page!)

Her father later carries her down to open her presents: skis, a toboggan, skates – her family has given her all she asked for even though everyone knows she won’t be doing sport again; there is no further treatment for her terminal cancer. That night, the angel Ariel appears to Cecilia and gets her thinking about the mysteries of life. He’s fascinated by memory and the temporary loss of consciousness that is sleep. How do these human processes work? “I wish I’d thought more about how it is to live,” Cecilia sighs, to which Ariel replies, “It’s never too late.” Weeks pass and Ariel engages Cecilia in dialogues and takes her on middle-of-the-night outdoor adventures, always getting her back before her parents get up to check on her. The book emphasizes the wonder of being alive: “You are an animal with the soul of an angel, Cecilia. In that way you’ve been given the best of both worlds.” This is very much a YA book and a little saccharine for me, but at least it was only 161 pages rather than the nearly 400 of Sophie’s World. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

Her father later carries her down to open her presents: skis, a toboggan, skates – her family has given her all she asked for even though everyone knows she won’t be doing sport again; there is no further treatment for her terminal cancer. That night, the angel Ariel appears to Cecilia and gets her thinking about the mysteries of life. He’s fascinated by memory and the temporary loss of consciousness that is sleep. How do these human processes work? “I wish I’d thought more about how it is to live,” Cecilia sighs, to which Ariel replies, “It’s never too late.” Weeks pass and Ariel engages Cecilia in dialogues and takes her on middle-of-the-night outdoor adventures, always getting her back before her parents get up to check on her. The book emphasizes the wonder of being alive: “You are an animal with the soul of an angel, Cecilia. In that way you’ve been given the best of both worlds.” This is very much a YA book and a little saccharine for me, but at least it was only 161 pages rather than the nearly 400 of Sophie’s World. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

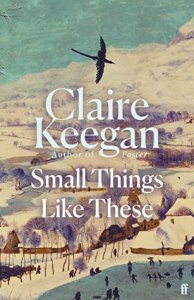

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan (2021)

I idly reread this while The Muppet Christmas Carol played in the background on a lazy, overfed Christmas evening.

It was an odd experience: having seen the big-screen adaptation just last month, the blow-by-blow was overly familiar to me and I saw Cillian Murphy and Emily Watson, if not the minor actors, in my mind’s eye. I realized fully just how faithful the screenplay is to the book. The film enhances not just the atmosphere but also the plot through the visuals. It takes what was so subtle in the book – blink-and-you’ll-miss-it – and makes it more obvious. Normally I might think it a shame to undermine the nuance, but in this case I was glad of it. Bill Furlong’s midlife angst and emotional journey, in particular, are emphasized in the film. It was probably a mistake to read this a third time within so short a span of time; it often takes me more like 5–10 years to appreciate a book anew. So I was back to my ‘nice little story’ reaction this time, but would still recommend this to you – book or film – if you haven’t yet experienced it. (Free at a West Berkshire Council recycling event)

It was an odd experience: having seen the big-screen adaptation just last month, the blow-by-blow was overly familiar to me and I saw Cillian Murphy and Emily Watson, if not the minor actors, in my mind’s eye. I realized fully just how faithful the screenplay is to the book. The film enhances not just the atmosphere but also the plot through the visuals. It takes what was so subtle in the book – blink-and-you’ll-miss-it – and makes it more obvious. Normally I might think it a shame to undermine the nuance, but in this case I was glad of it. Bill Furlong’s midlife angst and emotional journey, in particular, are emphasized in the film. It was probably a mistake to read this a third time within so short a span of time; it often takes me more like 5–10 years to appreciate a book anew. So I was back to my ‘nice little story’ reaction this time, but would still recommend this to you – book or film – if you haven’t yet experienced it. (Free at a West Berkshire Council recycling event)

Previous ratings: ![]() (2021 review);

(2021 review); ![]() (2022 review)

(2022 review)

My rating this time: ![]()

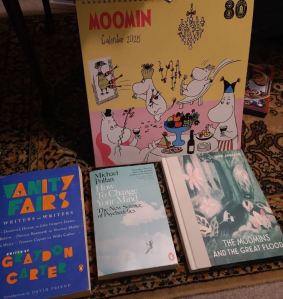

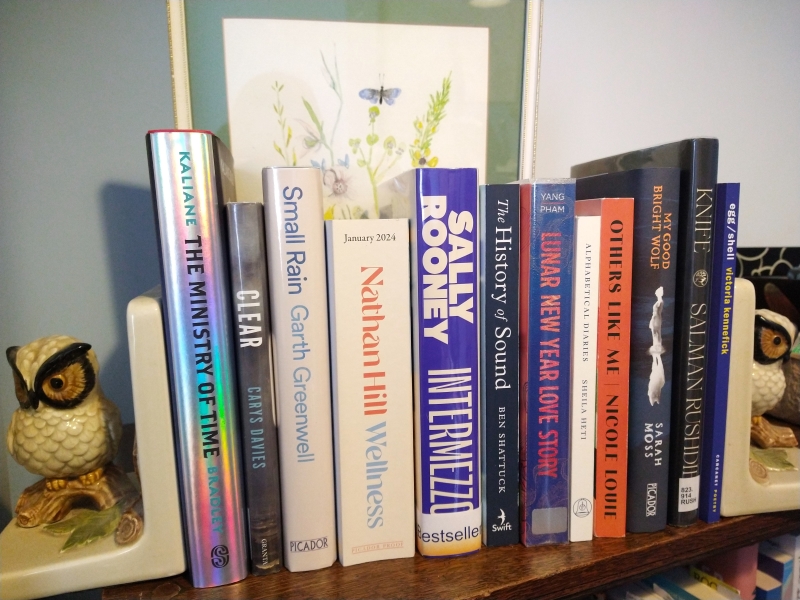

We hosted family for Christmas for the first time, which truly made me feel like a proper grown-up. It was stressful and chaotic but lovely and over all too soon. Here’s my lil’ book haul (but there was also a £50 book token, so I will buy many more!).

I hope everyone has been enjoying the holidays. I have various year-end posts in progress but of course the final Best-of list and statistics will have to wait until the turning of the year.

Coming up:

Sunday 29th: Best Backlist Reads of the Year

Monday 30th: Love Your Library & 2024 Reading Superlatives

Tuesday 31st: Best Books of 2024

Wednesday 1st: Final statistics on 2024’s reading

Review Catch-Up: Medical Nonfiction & Nature Poetry

Catching up on four review copies I was sent earlier in the year and have finally got around to finishing and writing about. I have two works of health-themed nonfiction, one a narrative about organ transplantation and the other a psychiatrist’s memoir; and two books of nature poetry, a centuries-spanning anthology and a recent single-author collection.

The Story of a Heart by Rachel Clarke

Rachel Clarke is a palliative care doctor and voice of wisdom on end-of-life issues. I was a huge fan of her Dear Life and admire her public critique of government policies that harm the NHS. (I’ve also reviewed Breathtaking, her account of hospital working during Covid-19.) While her three previous books all incorporate a degree of memoir, this is something different: narrative nonfiction based on a true story from 2017 and filled in with background research and interviews with the figures involved. Clarke has no personal connection to the case but, like many, discovered it via national newspaper coverage. Nine-year-old Max Johnson spent nearly a year in hospital with heart failure after a mysterious infection. Keira Ball, also nine, was left brain-dead when her family was in a car accident on a dangerous North Devon road. Keira’s heart gave Max a second chance at life.

Rachel Clarke is a palliative care doctor and voice of wisdom on end-of-life issues. I was a huge fan of her Dear Life and admire her public critique of government policies that harm the NHS. (I’ve also reviewed Breathtaking, her account of hospital working during Covid-19.) While her three previous books all incorporate a degree of memoir, this is something different: narrative nonfiction based on a true story from 2017 and filled in with background research and interviews with the figures involved. Clarke has no personal connection to the case but, like many, discovered it via national newspaper coverage. Nine-year-old Max Johnson spent nearly a year in hospital with heart failure after a mysterious infection. Keira Ball, also nine, was left brain-dead when her family was in a car accident on a dangerous North Devon road. Keira’s heart gave Max a second chance at life.

Clarke zooms in on pivotal moments: the accident, the logistics of getting an organ from one end of the country to another, and the separate recovery and transplant surgeries. She does a reasonable job of recreating gripping scenes despite a foregone conclusion. Because I’ve read a lot around transplantation and heart surgery (such as When Death Becomes Life by Joshua D. Mezrich and Heart by Sandeep Jauhar), I grew impatient with the contextual asides. I also found that the family members and medical professionals interviewed didn’t speak well enough to warrant long quotation. All in all, this felt like the stuff of a long-read magazine article rather than a full book. The focus on children also results in mawkishness. However, the Baillie Gifford Prize judges who shortlisted this clearly disagreed. I laud Clarke for drawing attention to organ donation, a cause dear to my family. This case was instrumental in changing UK law: one must now opt out of donating organs instead of registering to do so.

With thanks to Abacus Books (Little, Brown) for the proof copy for review.

You Don’t Have to Be Mad to Work Here: A Psychiatrist’s Life by Dr Benji Waterhouse

Waterhouse is also a stand-up comedian and is definitely channelling Adam Kay in his funny and touching debut memoir. Most chapters are pen portraits of patients and colleagues he has worked with. He also puts his own family under the microscope as he undergoes therapy to work through the sources of his anxiety and depression and tackles his reluctance to date seriously. In the first few years, he worked in a hospital and in community psychiatry, which involved house visits. Even though identifying details have been changed to make the case studies anonymous, Waterhouse manages to create memorable characters, such as Tariq, an unhoused man who travels with a dog (a pity Waterhouse is mortally afraid of dogs), and Sebastian, an outwardly successful City worker who had been minutes away from hanging himself before Waterhouse and his colleague rang on the door.

Waterhouse is also a stand-up comedian and is definitely channelling Adam Kay in his funny and touching debut memoir. Most chapters are pen portraits of patients and colleagues he has worked with. He also puts his own family under the microscope as he undergoes therapy to work through the sources of his anxiety and depression and tackles his reluctance to date seriously. In the first few years, he worked in a hospital and in community psychiatry, which involved house visits. Even though identifying details have been changed to make the case studies anonymous, Waterhouse manages to create memorable characters, such as Tariq, an unhoused man who travels with a dog (a pity Waterhouse is mortally afraid of dogs), and Sebastian, an outwardly successful City worker who had been minutes away from hanging himself before Waterhouse and his colleague rang on the door.

Along with such close shaves, there are tragic mistakes and tentative successes. But progress is difficult to measure. “Predicting human behaviour isn’t an exact science. We’re just relying on clinical assessment, a gut feeling and sometimes a prayer,” Waterhouse tells his medical student. The book gives a keen sense of the challenges of working for the NHS in an underfunded field, especially under Covid strictures. He is honest and open about his own failings but ends on the positive note of making advances in his relationship with his parents. This was a great read that I’d recommend beyond medical-memoir junkies like myself. Waterhouse has storytelling chops and the frequent one-liners lighten even difficult topics:

The sum total of my wisdom from time spent in the community: lots of people have complicated, shit lives.

Ambiguous statements … need clarification. Like when a depressed patient telephones to say they’re ‘in a bad place’. I need to check if they’re suicidal or just visiting Peterborough.

What is it about losing your mind that means you so often mislay your footwear too?

With thanks to Jonathan Cape (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Green Verse: An Anthology of Poems for Our Planet, ed. Rosie Storey Hilton

Part of the “In the Moment” series, this anthology of nature poetry has been arranged seasonally – spring through to winter – and, within season, roughly thematically. No context or biographical information is given on the poets apart from birth and death years for those not living. Selections from Emily Dickinson, William Shakespeare and W.B. Yeats thus share space with the work of contemporary and lesser-known poets. This is a similar strategy to the Wildlife Trusts’ Seasons anthologies, the ranging across time meant to suggest continuity in human engagement with the natural world. However, with a few exceptions (the above plus Thomas Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush” and Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “Inversnaid” are absolute classics, of course), the historical verse tends to be obscure, rhyming and sentimental; unfair to deem it all purple or doggerel, but sometimes bodies of work are forgotten for a reason. By contrast, I found many more standouts among the contemporary poets. Some favourites: “Cyanotype, by St Paul’s Cathedral” by Tamiko Dooley, “Eight Blue Notes” by Gillian Dawson (about eight species of butterfly), the gorgeously erotic “the bluebells are coming out & so am I” by Maya Blackwell, and “The Trees Don’t Know I’m Trans” by Eddy Quekett. It was also worthwhile to discover poems from other ancient traditions, such as haiku by Issa (“O Snail”) and wise aphoristic verse by Lao Tzu (“All things pass”). So, a bit of a mixed bag, but a nice introductory text for those newer to poetry.

Part of the “In the Moment” series, this anthology of nature poetry has been arranged seasonally – spring through to winter – and, within season, roughly thematically. No context or biographical information is given on the poets apart from birth and death years for those not living. Selections from Emily Dickinson, William Shakespeare and W.B. Yeats thus share space with the work of contemporary and lesser-known poets. This is a similar strategy to the Wildlife Trusts’ Seasons anthologies, the ranging across time meant to suggest continuity in human engagement with the natural world. However, with a few exceptions (the above plus Thomas Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush” and Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “Inversnaid” are absolute classics, of course), the historical verse tends to be obscure, rhyming and sentimental; unfair to deem it all purple or doggerel, but sometimes bodies of work are forgotten for a reason. By contrast, I found many more standouts among the contemporary poets. Some favourites: “Cyanotype, by St Paul’s Cathedral” by Tamiko Dooley, “Eight Blue Notes” by Gillian Dawson (about eight species of butterfly), the gorgeously erotic “the bluebells are coming out & so am I” by Maya Blackwell, and “The Trees Don’t Know I’m Trans” by Eddy Quekett. It was also worthwhile to discover poems from other ancient traditions, such as haiku by Issa (“O Snail”) and wise aphoristic verse by Lao Tzu (“All things pass”). So, a bit of a mixed bag, but a nice introductory text for those newer to poetry.

With thanks to Saraband for the free copy for review.

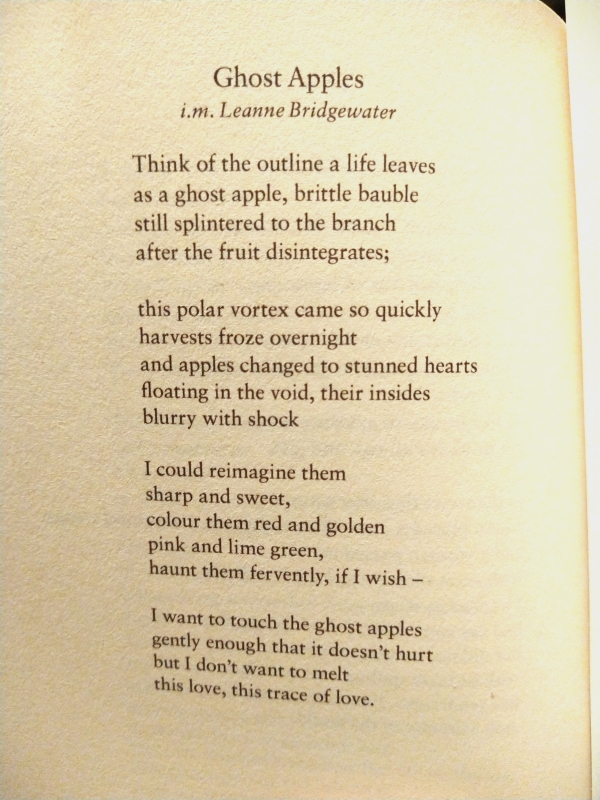

Dangerous Enough by Becky Varley-Winter (2023)

I requested this debut collection after hearing that it had been longlisted for the Laurel Prize for environmental poetry (funded by Simon Armitage, Poet Laureate). Varley-Winter crafts lovely natural metaphors for formative life experiences. Crows and wrens, foxes and fireflies, memories of a calf being born on a farm in Wales; gardens, greenhouses and long-lived orchids. These are the sorts of images that thread through poems about loss, parenting and the turmoil of lockdown. The last line or two of a poem is often especially memorable. It’s been months since I read this and I foolishly didn’t take any notes, so I haven’t retained more detail than that. But here is one shining example:

I requested this debut collection after hearing that it had been longlisted for the Laurel Prize for environmental poetry (funded by Simon Armitage, Poet Laureate). Varley-Winter crafts lovely natural metaphors for formative life experiences. Crows and wrens, foxes and fireflies, memories of a calf being born on a farm in Wales; gardens, greenhouses and long-lived orchids. These are the sorts of images that thread through poems about loss, parenting and the turmoil of lockdown. The last line or two of a poem is often especially memorable. It’s been months since I read this and I foolishly didn’t take any notes, so I haven’t retained more detail than that. But here is one shining example:

With thanks to Salt Publishing for the free copy for review.

Baumgartner’s past is similar to Auster’s (and Adam Walker’s from Invisible – the two characters have a mutual friend in writer James Freeman), but not identical. His childhood memories and the passion and companionship he found with Anna are quite sweet. But I was somewhat thrown by the tone in sections that have this grumpy older man experiencing pseudo-comic incidents such as tumbling down the stairs while showing the meter reader the way. To my relief, the book doesn’t take the tragic turn the last pages seem to augur, instead leaving readers with a nicely open ending.

Baumgartner’s past is similar to Auster’s (and Adam Walker’s from Invisible – the two characters have a mutual friend in writer James Freeman), but not identical. His childhood memories and the passion and companionship he found with Anna are quite sweet. But I was somewhat thrown by the tone in sections that have this grumpy older man experiencing pseudo-comic incidents such as tumbling down the stairs while showing the meter reader the way. To my relief, the book doesn’t take the tragic turn the last pages seem to augur, instead leaving readers with a nicely open ending. This is very much in the vein of

This is very much in the vein of  That’s at the heart of Part I (“Spring”). Across four sections, the perspective changes and the narrative is revealed to be 1967, a manuscript Adam began while dying of cancer. “Summer,” in the second person, shines a light on his relationship with his sister, Gwyn. “Fall,” adapted from Adam’s third-person notes by his college friend and fellow author, Jim Freeman, tells of Adam’s study abroad term in Paris. Here he reconnected with Born and Margot with unexpected results. Jim intends to complete the anonymized story with the help of a minor character’s diary, but the challenge is that Adam’s memories don’t match Gwyn’s or Born’s.

That’s at the heart of Part I (“Spring”). Across four sections, the perspective changes and the narrative is revealed to be 1967, a manuscript Adam began while dying of cancer. “Summer,” in the second person, shines a light on his relationship with his sister, Gwyn. “Fall,” adapted from Adam’s third-person notes by his college friend and fellow author, Jim Freeman, tells of Adam’s study abroad term in Paris. Here he reconnected with Born and Margot with unexpected results. Jim intends to complete the anonymized story with the help of a minor character’s diary, but the challenge is that Adam’s memories don’t match Gwyn’s or Born’s. Iris Vegan (Hustvedt’s mother’s surname), like many an Auster character, is bewildered by what happens to her. An impoverished graduate student in literature, she takes on peculiar jobs. First Mr. Morning hires her to make audio recordings meticulously describing artefacts of a woman he’s obsessed with. Iris comes to believe this woman was murdered and rejects the work as invasive. Next she’s a photographer’s model but hates the resulting portrait and tries to take it off display. Then she’s hospitalized for terrible migraines and has upsetting encounters with a fellow patient, old Mrs. O. Finally, she translates a bizarre German novella and impersonates its protagonist, walking the streets in a shabby suit and even telling people her name is Klaus.

Iris Vegan (Hustvedt’s mother’s surname), like many an Auster character, is bewildered by what happens to her. An impoverished graduate student in literature, she takes on peculiar jobs. First Mr. Morning hires her to make audio recordings meticulously describing artefacts of a woman he’s obsessed with. Iris comes to believe this woman was murdered and rejects the work as invasive. Next she’s a photographer’s model but hates the resulting portrait and tries to take it off display. Then she’s hospitalized for terrible migraines and has upsetting encounters with a fellow patient, old Mrs. O. Finally, she translates a bizarre German novella and impersonates its protagonist, walking the streets in a shabby suit and even telling people her name is Klaus.

If you need to like a protagonist, expect frustration. Some of George’s behaviour is downright maddening, as when he obsessively plays his old Gameboy while his mother and Jenny pack up his childhood room. Tracing his relationships with his mother, his sister Cressida, and Jenny is rewarding. Sometimes they confront him over his shortcomings; other times they enable him. The novel is very funny, but it’s a biting, ironic humour, and there’s plenty of pathos as well. There are a few particular gut-punches, one relating to George’s father and others surrounding nice things he tries to do that backfire horribly. I thought of George as a rejoinder to all those ‘So-and-So Is Not Okay at All’ type of books featuring a face-planting woman on the cover. Greathead’s portrait is incisive but also loving. And yes, there is that hint of George, c’est moi recognition. His failings are all too common: the mildest of first-world tragedies but still enough to knock your confidence and make you question your purpose. For me this had something of the old-school charm of Jennifer Egan and Jonathan Safran Foer novels I read in the Naughties. I’ll seek out the author’s debut, Laura & Emma.

If you need to like a protagonist, expect frustration. Some of George’s behaviour is downright maddening, as when he obsessively plays his old Gameboy while his mother and Jenny pack up his childhood room. Tracing his relationships with his mother, his sister Cressida, and Jenny is rewarding. Sometimes they confront him over his shortcomings; other times they enable him. The novel is very funny, but it’s a biting, ironic humour, and there’s plenty of pathos as well. There are a few particular gut-punches, one relating to George’s father and others surrounding nice things he tries to do that backfire horribly. I thought of George as a rejoinder to all those ‘So-and-So Is Not Okay at All’ type of books featuring a face-planting woman on the cover. Greathead’s portrait is incisive but also loving. And yes, there is that hint of George, c’est moi recognition. His failings are all too common: the mildest of first-world tragedies but still enough to knock your confidence and make you question your purpose. For me this had something of the old-school charm of Jennifer Egan and Jonathan Safran Foer novels I read in the Naughties. I’ll seek out the author’s debut, Laura & Emma. The family’s lies and secrets – also involving a Christmas run-in with Bruce’s shell-shocked brother decades ago – lead to everything coming to a head in a snowstorm. (As best I can tell, the 1995 setting was important mostly so there wouldn’t be cell phones during this crisis.) As with The Book of George, the episodic nature of the narrative means that particular moments are memorable but the whole maybe less so, and the interactions between characters stand out more than the people themselves. I’ll Come to You, named after a throwaway line in the text, is poorly served by both its cover and title, which give no sense of the contents. However, it’s a sweet, offbeat portrait of genuine, if generic, Americans; I was most reminded of J. Ryan Stradal’s work. Although I DNFed Kauffman’s The Gunners some years back, I’d be interested in trying her again with Chorus, which sounds like another linked story collection.

The family’s lies and secrets – also involving a Christmas run-in with Bruce’s shell-shocked brother decades ago – lead to everything coming to a head in a snowstorm. (As best I can tell, the 1995 setting was important mostly so there wouldn’t be cell phones during this crisis.) As with The Book of George, the episodic nature of the narrative means that particular moments are memorable but the whole maybe less so, and the interactions between characters stand out more than the people themselves. I’ll Come to You, named after a throwaway line in the text, is poorly served by both its cover and title, which give no sense of the contents. However, it’s a sweet, offbeat portrait of genuine, if generic, Americans; I was most reminded of J. Ryan Stradal’s work. Although I DNFed Kauffman’s The Gunners some years back, I’d be interested in trying her again with Chorus, which sounds like another linked story collection. Mills and Shaw consider the same fundamental issues: bi erasure, with bisexuality the least understood and most easily overlooked element of LGBT and many passing as straight if in heterosexual marriages; and the stereotype of bis as hypersexual or promiscuous. Mills is keen to stress that bisexuals have very different trajectories and phases. Like Wilde, they might have a heterosexual era of happy marriage and parenthood followed by a homosexual spree. Or they might have simultaneous lovers of multiple genders. Some might never even act on strong same-sex desires. (Late last year I encountered a similar unity-in-diversity approach in Daniel Tamet’s Nine Minds, a group biography about autistic people.)

Mills and Shaw consider the same fundamental issues: bi erasure, with bisexuality the least understood and most easily overlooked element of LGBT and many passing as straight if in heterosexual marriages; and the stereotype of bis as hypersexual or promiscuous. Mills is keen to stress that bisexuals have very different trajectories and phases. Like Wilde, they might have a heterosexual era of happy marriage and parenthood followed by a homosexual spree. Or they might have simultaneous lovers of multiple genders. Some might never even act on strong same-sex desires. (Late last year I encountered a similar unity-in-diversity approach in Daniel Tamet’s Nine Minds, a group biography about autistic people.) I’ve also read Watts’

I’ve also read Watts’

Tomkins first wrote this for the Bath Prize in 2018 and was longlisted. She initially sent the book out to science fiction publishers but was told that it wasn’t ‘sci-fi enough’. I can see how it could fall into the gap between literary fiction and genre fiction: though it’s set on other planets and involves space travel, its speculative nature is understated; it feels more realist. A memorable interrogation of longing and belonging, this novella ponders the value of individuals and their choices in the midst of inexorable planetary trajectories.

Tomkins first wrote this for the Bath Prize in 2018 and was longlisted. She initially sent the book out to science fiction publishers but was told that it wasn’t ‘sci-fi enough’. I can see how it could fall into the gap between literary fiction and genre fiction: though it’s set on other planets and involves space travel, its speculative nature is understated; it feels more realist. A memorable interrogation of longing and belonging, this novella ponders the value of individuals and their choices in the midst of inexorable planetary trajectories.

North of Ordinary by John Rolfe Gardiner (Bellevue Literary Press, January 14): I read 5 of 10 stories about young men facing life transitions and enjoyed the title one set at a thinly veiled Liberty University but found the rest dated in outlook; all have too-sudden endings.

North of Ordinary by John Rolfe Gardiner (Bellevue Literary Press, January 14): I read 5 of 10 stories about young men facing life transitions and enjoyed the title one set at a thinly veiled Liberty University but found the rest dated in outlook; all have too-sudden endings. If Nothing by Matthew Nienow (Alice James Books, January 14): Straightforward poems about giving up addiction and seeking mental health help in order to be a good father.

If Nothing by Matthew Nienow (Alice James Books, January 14): Straightforward poems about giving up addiction and seeking mental health help in order to be a good father.  The Cannibal Owl by Aaron Gwyn (Belle Point Press, January 28): An orphaned boy is taken in by the Comanche in 1820s Texas in a brutal novella for fans of Cormac McCarthy.

The Cannibal Owl by Aaron Gwyn (Belle Point Press, January 28): An orphaned boy is taken in by the Comanche in 1820s Texas in a brutal novella for fans of Cormac McCarthy.

Memorial Days by Geraldine Brooks (Viking, February 4): This elegant bereavement memoir chronicles the sudden death of Brooks’s husband (journalist Tony Horwitz) in 2019 and her grief retreat to Flinders Island, Australia.

Memorial Days by Geraldine Brooks (Viking, February 4): This elegant bereavement memoir chronicles the sudden death of Brooks’s husband (journalist Tony Horwitz) in 2019 and her grief retreat to Flinders Island, Australia.  Reading the Waves by Lidia Yuknavitch (Riverhead, February 4): Yuknavitch’s bold memoir-in-essays focuses on pivotal scenes and repeated themes from her life as she reckons with trauma and commemorates key relationships. (A little too much repeated content from The Chronology of Water for me.)

Reading the Waves by Lidia Yuknavitch (Riverhead, February 4): Yuknavitch’s bold memoir-in-essays focuses on pivotal scenes and repeated themes from her life as she reckons with trauma and commemorates key relationships. (A little too much repeated content from The Chronology of Water for me.)

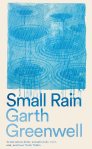

Small Rain by Garth Greenwell: A poet and academic (who both is and is not Greenwell) endures a Covid-era medical crisis that takes him to the brink of mortality and the boundary of survivable pain. Over two weeks, we become intimately acquainted with his every test, intervention, setback and fear. Experience is clarified precisely into fluent language that also flies far above a hospital bed, into a vibrant past, a poetic sensibility, a hoped-for normality. I’ve never read so remarkable an account of what it is to be a mind in a fragile body.

Small Rain by Garth Greenwell: A poet and academic (who both is and is not Greenwell) endures a Covid-era medical crisis that takes him to the brink of mortality and the boundary of survivable pain. Over two weeks, we become intimately acquainted with his every test, intervention, setback and fear. Experience is clarified precisely into fluent language that also flies far above a hospital bed, into a vibrant past, a poetic sensibility, a hoped-for normality. I’ve never read so remarkable an account of what it is to be a mind in a fragile body.